Published

European Strategic Autonomy – Aim or Bane for Our Generation?

By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: EU Single Market European Union

In September 2020, European Council President Charles Michel delivered a long speech on Europe’s “strategic autonomy, sovereignty, and power”. He concluded that “whichever word you use”, it is the substance that eventually matters: “Less dependence, more influence” should be the “aim of our generation”.

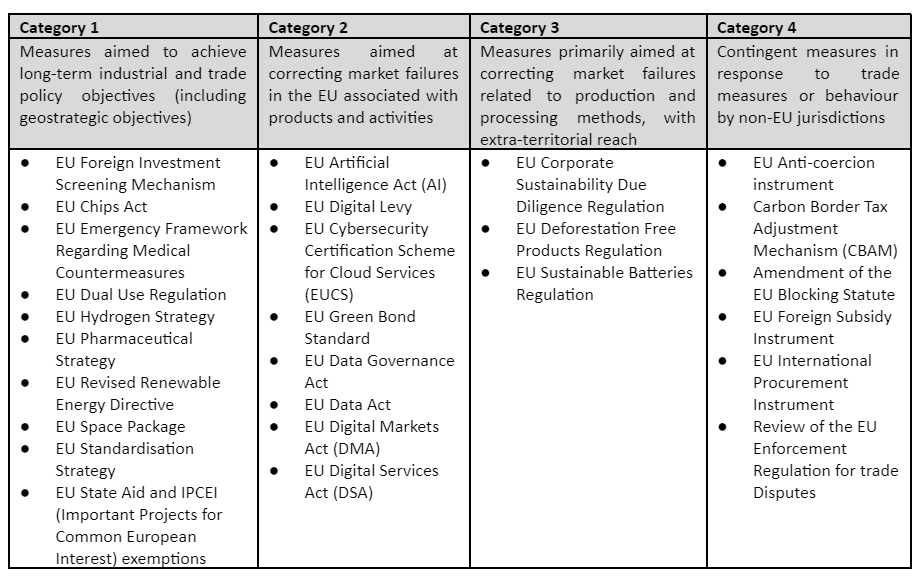

The EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm and many policies it defends are rooted in a broader set of geopolitical clashes questioning the role of government in society. Most of the EU’s strategic autonomy ambitions are inherently guided by a “European Union First” impulse. It manifests itself in the assumption that EU law-making is somehow superior to – at least different from – law-making in other parts in the world. This sense of superiority encompasses values underpinning policy choices in economic, trade and technology policymaking. In light of the EU’s sustained Single Market Disease, strategic autonomy aspirations represent a relapse to old policy making, that of EU Member States independently designing and enforcing rules without considering the economic and political costs of regulatory fragmentation and economic disintegration at the EU level. A forthcoming study shows that, if implemented, the EU’s strategic anatomy initiatives are likely to impose costs on EU trade and production, which would reduce Europeans’ living standards. Depending on the stringency of the measures involved, gross national income in the EU would fall by several billion euros annually, especially if trade partners retaliate.

Below I argue that any EU aim for independence and geopolitical influence should be guided by the spirit of the open society – a society embracing the principles of free trade, non-discrimination, and economic freedom. To achieve strategic autonomy ambitions, Brussels and Member State capitals will have to improve regulatory skills at home in support of education, economic freedom and technological innovation. The EU needs to become an example of good governance and regulatory excellence that others want to follow. EU policymakers must abstain from unilateral initiatives that contribute to the diffusion of protectionist policies globally, particularly in countries with weak institutional capacity, and undermine the rules-based trading system.

I start presenting a taxonomy and outline of key strategic autonomy initiatives. I proceed with an outline of costs from rising EU trade restrictions and economic disintegration, followed by a discussion of impacts on multilateral obligations and the international trading system. The article concludes with an outlook for Europe’s geopolitical influence and recommendations regarding Europe’s role in shaping the rules for the global economy of tomorrow.

Key take aways

Recent EU policy priorities guided by concepts of strategic autonomy

It is difficult to present a clean taxonomy of EU strategic autonomy policies. After all, stressing the need to achieve economic resilience, technological sovereignty or geopolitical influence aspired to a promising means of political storytelling to restore (lost) trust in EU institutions and gain support for EU-level policymaking.

In 2020, Josep Borrell, the EU’s High Representative, clarified that strategic autonomy must go beyond defence and security. The concept should be extended to the realm of business and technology “to ensure that Europeans can increasingly take charge of themselves.” The past two years witnessed many more speeches and calls for EU action in the name of European strategic autonomy. Policy initiatives ranged from defence and cybersecurity to trade and technology policy.

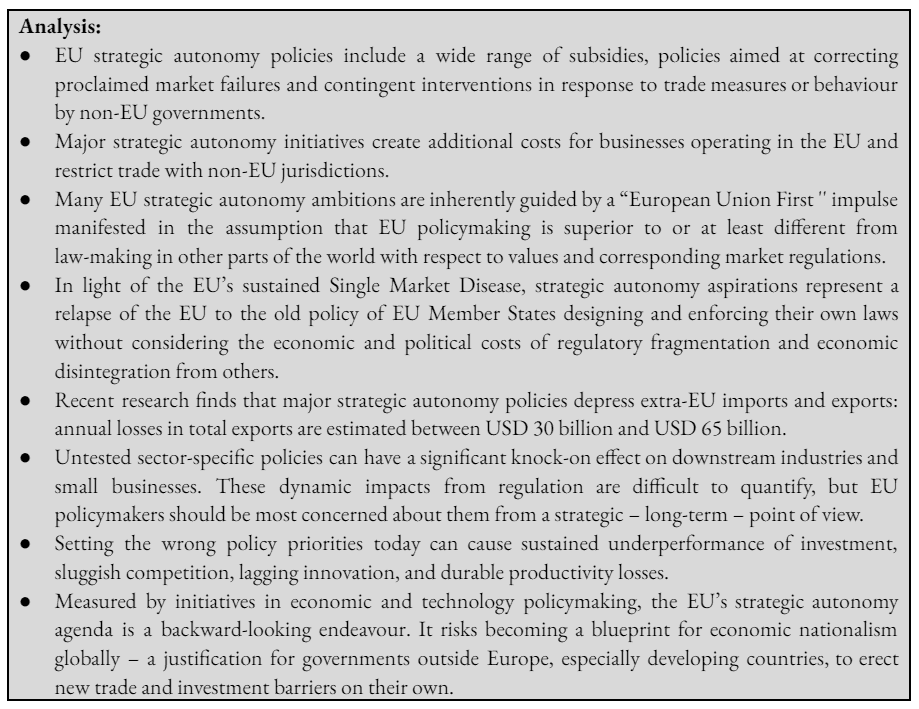

In the broad field of economic policymaking, we can broadly distinguish policy initiatives based on four central concerns:

1. EU interventions seeking industrial and trade policy objectives through direct interventions in favour of EU businesses, such as reducing perceived dependencies on non-EU suppliers, underinvestment in R&D, and industrial modernisation, where interventions are generally geared to conferring advantages to EU businesses over those from outside the EU.

2. EU interventions aimed at correcting proclaimed market failures (primarily) in the EU, including perceived market power and collective action problems (environmental impacts), but also ethical concerns related to fundamental rights.

3. EU interventions intended to correct proclaimed market failures related to production and processing methods with extra-territorial reach, including value chain resilience and environmental standards.

4. Contingent EU interventions in response to trade measures or behaviour by non-EU governments, including responses to perceived trade restrictive or distortive policies, or actions sought to remedy what the EU perceives to be a shortcoming in the multilateral toolkit.

For each category, relevant EU policy initiatives are outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1: (Broad) taxonomy of Strategic Autonomy policies and proposed initiatives by major category

Source: Frontier Economics and ECIPE. It should be noted that these categories cannot be clearly delineated from each other. Some measures in category 1 include measures intended to address perceived market failures related to R&D. Some measures in category 2 also seek to enhance the competitive position of EU industries, while some category 2 measures can have extra-territorial reach. Also, some measures in category 4 can help address prevailing market failures such as asymmetric information about the extent of state aid and negative externalities caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Source: Frontier Economics and ECIPE. It should be noted that these categories cannot be clearly delineated from each other. Some measures in category 1 include measures intended to address perceived market failures related to R&D. Some measures in category 2 also seek to enhance the competitive position of EU industries, while some category 2 measures can have extra-territorial reach. Also, some measures in category 4 can help address prevailing market failures such as asymmetric information about the extent of state aid and negative externalities caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

“Europe First” and the choice of policy priorities for European strategic autonomy

Many EU strategic autonomy ambitions are inherently guided by a “European Union First” impulse manifested in the assumption that EU law-making is superior to or at least different from law-making in other parts in the world with respect to values and corresponding market regulations.

The EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm and many policies defended by it are rooted in a broader set of geopolitical clashes questioning regarding the role and reach of government in society. In Brussels, much of today’s debate is about protecting Europeans from an increasingly hostile and challenging world. It unfolded momentum after the fiscal and economic crises of 2009 to 2012. It is a reaction to the rise of China’s state-interventionist influence in the world, including Chinese investments in Europe, the challenges in multilateral economic cooperation, the perception of US-Chinese hegemony in the digital world, US protectionism based on national security considerations, the EU’s trust crisis and the rise of populism, the impacts of COVID-19, and responses to Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine (with aggressions starting to evolve in 2014).

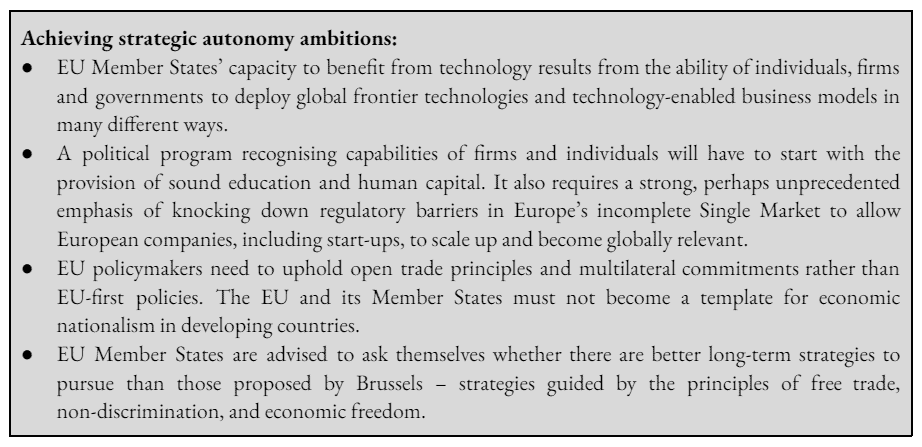

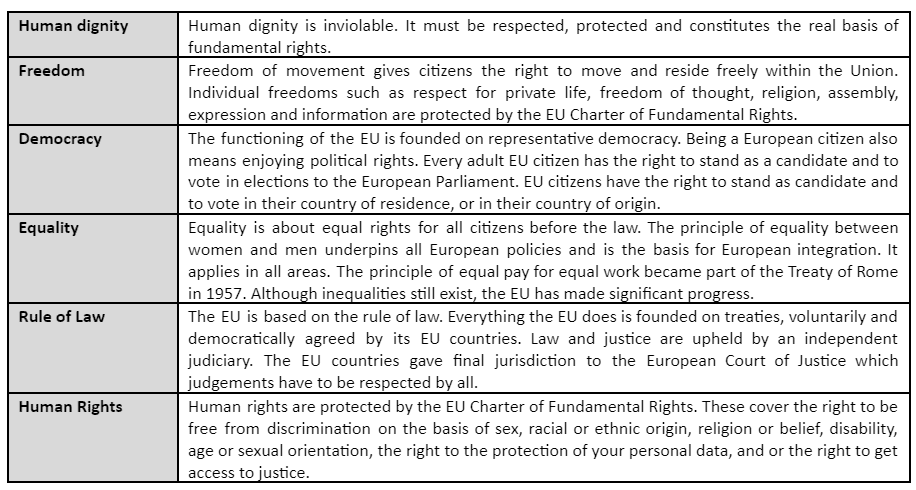

As argued by Burwell and Propp, the “return of geopolitics prompted a review of Europe’s strategic position and, at least within EU institutions, gave rise to a belief that Europe should seek greater ‘strategic autonomy‘, strengthening its capacity to act externally on its own […]“. This is expressed by EU institutions underlining the need to defend “our European values” (see Table 2), as highlighted by the political guidelines of the von der Leyen Commission, aiming to protect the “European Way of Life”, and delegated working programs.

Table 2: Core values of the European Union

Source: European Commission

Source: European Commission

In the case of strategic autonomy, European values aim to guide a large package of legislation on state aid and industrial policies, new rules for competition and new policies for data, artificial intelligence, and investment – often accompanied by the ambition to strengthen Europe’s global influence and the goal to improve the competitiveness of Europe’s industry.

Anchoring EU politics in an understanding of values is undoubtedly important, especially when these values are based on the ideals of the European enlightenment, underpinning Universal Human Rights. However, the values proclaimed by the EU are neither novel nor exclusive to Europe, and they all too often come at the expense of policy detail and poor regulatory design. If there is one charge that can be made against this type of value-based policymaking, it is that it comes across as hollow grandstanding, hiding contradictions, inconsistencies, and often ineffectiveness of EU policymaking.

Recurring references to European values lead to the impression that people outside Europe have different values or values that could pose a threat to Europeans’ way of life. At the heart of this view is the perception that EU trade and technology regulation presents a fundamental choice between European values, on the one hand, and the freedom to do business with non-Europeans on the other. It is notable, for example, how fast that some EU policymakers call for far-reaching measures to create notional data sovereignty, reinforcing a misguided view that in order to create a larger digital autonomy, Europe must close itself off from the rest of the world. Radical views like this ignore that Europe’s “digital sovereignty” is rather based on the capacity of citizens and firms to have access to key technologies services and be independently capable to understand, use and alter these services in line with fundamental rights.

Importantly, Europe is not so different from other jurisdictions in the desire to safeguard citizens and make sure that businesses thrive. OECD countries, for example, have ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Most OECD countries already have or are considering laws to regulate in key areas of interest for the EU. OECD countries already established more than 300 committees, expert and working groups which cover almost all areas of policy making including trade and technology regulation. As an open and export-driven economy, Brussels should not try to set the global standards for trade and technology alone. Europe’s policymakers should aim for closer market integration and regulatory cooperation with trustworthy international partners such as the G7 or the larger group of the OECD countries. It is in the EU’s self-interest to advocate for a rules-based international order with open markets. It is neither in the EU’s economic nor its political interest to disintegrate from the partner countries. As outlined below, new trade restrictions, increased policy fragmentation and economic disintegration come at high cost for Europeans.

Disintegration and the costs of international policy fragmentation

In light of the EU’s sustained Single Market Disease, strategic autonomy aspirations represent a relapse of the EU to the old policy of EU member states designing and enforcing their own laws without considering the economic and political costs of regulatory fragmentation and economic disintegration from others. With new and unique EU rules for specific industries, digital services and competition, the EU risks decoupling Member State economies from the rest of the word. It risks harming EU economic activity in two ways: by erecting new regulatory hurdles for businesses operating in EU Member States and by creating a regulatory landscape in the Member States that is difficult to navigate for exporters and foreign investors, especially small businesses.

Regulatory fragmentation is costly for businesses. Overcoming policy fragmentation still is, at least on paper, a guiding principle in EU economic policymaking. With the creation of the Single European Market in 1993, EU institutions attempted to harmonise national laws that regulate businesses and the markets for products and services across the EU. The aim was to create a common market without technical and bureaucratic barriers to trade, in other words, a simplified regulatory level-playing field encouraging Europeans to trade and do business with each other.

However, the Single Market does not really exist. Europe’s Single Market exists only nominally. It is in many ways an illusion. There are still substantial barriers to cross-border exchange. National markets are riddled with uncertainty about market access, especially in services sectors, labour market regulation and taxation. Member State economies have undergone profound structural changes in the past. Their economies moved further into sectors and areas where there is no or very little of the Single Market.

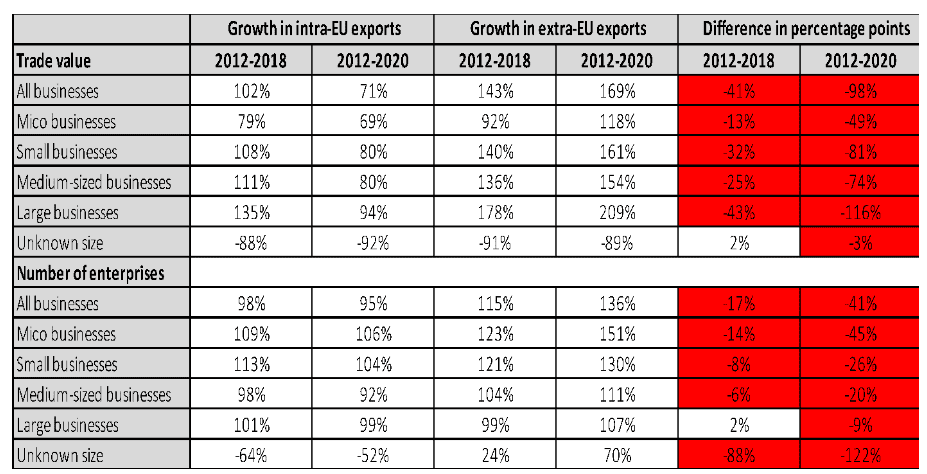

Ever since 1993, harmonising regulation has been a cat-and-mouse game: when old national approaches to regulation have been knocked down, new ones have risen elsewhere in the economy. Especially, with the structural change of the economy – leading to a greater role for services and digital output – the result became a European market that remains fragmented and that still comes with high costs of doing business across internal borders. Unsurprisingly, intra-EU goods trade by all those that are sensitive to regulatory differences, including small- and micro-sized businesses, has failed to grow significantly when compared to exports to markets outside EU (see Table 3).

Table 3: Underperformance of intra-EU goods trade versus extra-EU goods trade, trade value and number of trading enterprises by size class

Source: Eurostat. Note that values presented for the period 2012-2018 aim to capture pre-COVID-19 growth.

Source: Eurostat. Note that values presented for the period 2012-2018 aim to capture pre-COVID-19 growth.

It is startling that new EU policy initiatives under the label of strategic autonomy, such as the Data Act, the AI Act, the Certification Scheme on Cloud Services, the Digital Market Act, the Digital Services Act or the investment screening mechanism, are typically presented as initiatives to improve and “complete“ the Single Market. However, these (proposed) laws will add new costs for businesses including SMEs, which intensively use modern digital services. And these new laws will in many cases not be implemented equally and consistently across EU Member States, creating more uncertainty about rules for doing business in the EU. Another effect is that that these laws distract public attention and political capital away from areas in which more Single Market is needed for Europe to thrive on borderless trade, competition and innovation.

Empirical research is clear about the costs created by regulatory barriers that prevent, stifle, or even eliminate imports and investments from abroad. As is shown by the mapping of the cost of non-Europe by the European Parliamentary Research Service, the consequences are higher cost of doing business in the Member States, less opportunities for exploiting economies of scale, and depressed entrepreneurial churn. On top of that, there are substantial medium- to long-term dynamic impacts that cannot easily be quantified, such as reduced competitive pressure and international competitiveness, less diffusion of knowledge and technology, fewer incentives to innovate, and, eventually, slowed-down structural economic change and renewal. It is these costs that also accrue from key strategic autonomy policies.

For major initiatives under the EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm, a forthcoming study by Frontier economics provides estimates of costs from a wide range of policy proposals and initiatives pursued under the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda. It is highlighted that, if implemented, “these initiatives are likely to impose costs on EU imports and exports, which would reduce EU living standards”. Depending on the stringency of the measures involved and the degree of retaliation by EU trading partners that are confronted with EU trade measures, real income would fall by several billion euros annually, with the highest reduction in income and welfare being estimated for scenarios in which retaliation by partners kicks in. The negative effects on trade and economic activity result from the fact that the EU’s own measures depress extra-EU imports and exports, causing, for example, annual losses in total exports between some USD 30 billion and USD 65 billion. It is highlighted that certain EU policy inventions may increase trade within the EU, but this increase would be insufficient to compensate for lost trade with jurisdictions outside the EU including the US and OECD countries. In essence, it is stated, the policy measures envisioned under strategic autonomy collectively act as an EU law-induced tax on Europe’s trade with the rest of the world.

Interestingly, costs from new subsidies and preferential public procurement policies (category 1 measures, see Table 1), aiming at strategic trade and industrial policy objectives, account for about two thirds of the estimated trade costs. By contrast, the estimated impacts of policy fragmentation in digital policymaking (category 2) and measures aimed primarily at correcting market failures relating to production methods (category 3), such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, tend to be more limited, depending, however, on their final degree of restrictiveness and whether countries outside the EU implement or abstain from related policies. Finally, contingent measures responding to trade measures or behaviour by governments outside the EU, such as the Trade Enforcement Mechanism, the Foreign Subsidy Instrument and the International Procurement Instrument (category 4), cause significant trade costs as these measures would directly impact on specific industries and trade flows respectively.

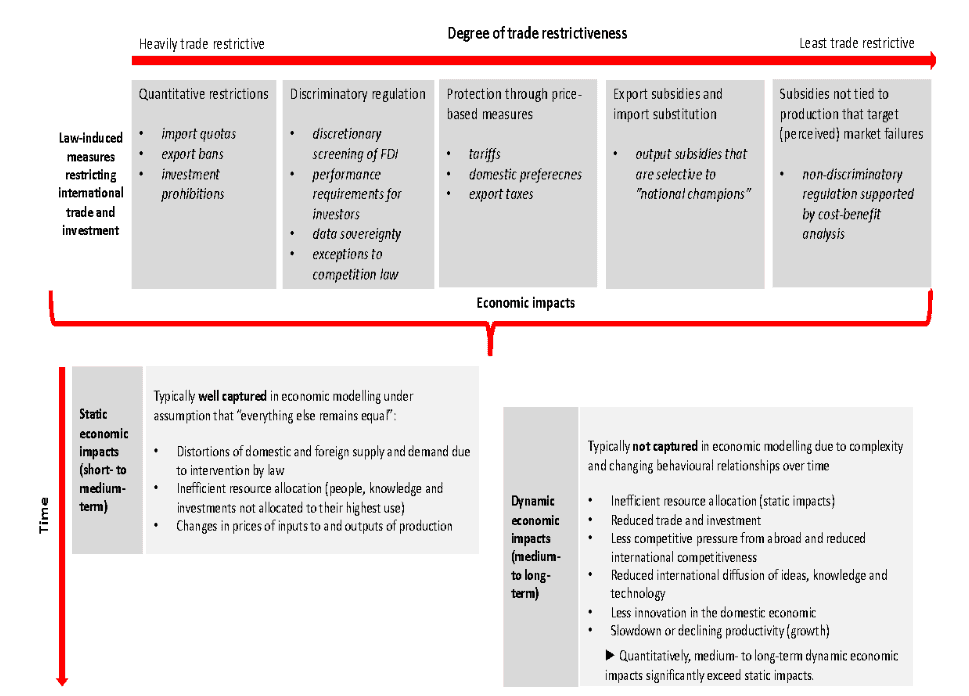

Frontier’s estimates are comparative-static by nature. In simple terms, this means that the applied (econometric and general equilibrium) models do not capture important dynamic effects over time and therefore tend to understate longer-term economic costs. Static economic impacts from trade and investment restrictions result from the shifting of resources from efficient to inefficient companies or industries as trade or investment barriers rise. By contrast dynamic economic impacts are about the longer-term path of overall growth in a market, industry or country resulting from reductions of productive investment, inefficient production and lower opportunities from exploiting international economies of scale through trade (see Figure 1 below).

The EU’s strategic autonomy policies restrict trade and competition to varying degrees. As a rule of thumb, quantitative restrictions, such as quotas and bans on imports and investments from aboard as more trade restrictive than the regulation of prices, subsidies and standards that equally apply for domestic and foreign suppliers.

However, novel and typically untested digital polices regulation, such as new data flow restrictions, data sharing obligations, taxes on digital services and limitations of business freedom in markets for digital services can have a significant knock-on effect on downstream sectors and small businesses. It is these dynamic economic impacts that EU policymakers should be most concerned about from a “strategic” point of view. Setting the wrong policy priorities today together with poorly crafted policy detail can cause long-term underperformance of investment, sluggish competition, lagging innovation, and durable productivity losses. And they can manifest longstanding productivity and technology gaps relative to other parts of the world – as in the case of the EU’s profound productivity and innovation gap versus the US.

Figure 1: Static and dynamic impacts from policies restricting international trade and investment and how they are captured in economic modelling

Source: own illustration inspired by research of Frontier Economics. It should be noted that some CGE models provide components that allow for the modelling of some dynamic effects, such as the evolution of prices, consumer welfare, savings and investments. However, their forecasting power is extremely limited, especially for impacts on competition, knowledge and information spillovers, technology diffusion, and factor productivity. Dynamic economic modelling of regulatory impacts over a longer period of time remains challenging and results should be treated with caution.

Source: own illustration inspired by research of Frontier Economics. It should be noted that some CGE models provide components that allow for the modelling of some dynamic effects, such as the evolution of prices, consumer welfare, savings and investments. However, their forecasting power is extremely limited, especially for impacts on competition, knowledge and information spillovers, technology diffusion, and factor productivity. Dynamic economic modelling of regulatory impacts over a longer period of time remains challenging and results should be treated with caution.

Impacts from retaliation and weaker multilateral obligations

Measured by many initiatives in the realm of economic and technology policymaking, the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda is a backward-looking endeavour. It risks becoming a blueprint for economic nationalism globally – a justification for governments outside Europe, especially developing countries, to erect new trade and investment barriers on their own.

With its recent communiqué on “Open Strategic Autonomy”, the European Commission is reconsidering its trade and investment priorities to better and more assertively drive a process towards “fairer and more sustainable globalisation”. While autonomy and fairness in economic life might be what populations legitimately decide they prefer, proceedings in Brussels often bring to life laws that run counter to fairness and resilience, and the ability to act independent from other countries areas of strategic importance. EU policymaking often seeks to intervene on contested grounds rather than striving for better regulatory approaches and policies that are accepted by like-minded partner countries. Take taxes on digital services (recently coined EU digital levy) as an example. Several studies on the impact of a tax on digital services find that the tax is financially borne by firms buying online advertising services, marketplace listings, or user data, and the consumers downstream from those transactions. It does not come as a surprise that most OECD countries including the US oppose this type of tax. At the same time, developing and emerging market economies such as India and Kenya, inspired by the EU’s original template, implemented or take into consideration taxes on modern digital services.

With its strategic autonomy acquis, EU policymakers not only risk decoupling Europe economically by reducing the openness and exposure of EU industries to international competition and innovation. They also risk decoupling the EU politically by pushing a regulatory agenda that will in many cases not be mirrored by major partner countries, such as the larger group of economically developed OECD countries. With new subsidies, discriminatory industrial policymaking and the inflated use of values as an excuse for unique EU action, the EU is paving the way for more government intervention and fewer binding rules in the global economy.

Take subsidies as an example. Subsidies are more than sand in the wheels of trade and investment. They impact on economic diplomacy and ambitions for international policy cooperation. As recently highlighted by the OECD, “the growing use of distortive subsidies alters trade and investment flows, detracts from the value of tariff bindings and other market access commitments, and undercuts public support for open trade.” Distinguishing “good” and “bad” subsidies is analytically and politically fraught. A case in point is the current conflict over US subsidies for electric vehicles and discriminatory treatment of foreign carmakers as part of the US Inflation Reduction Act. In economic terms, it is a comparatively insignificant dispute. However, it is reported to hold back much more important talks and negotiations in the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC), which is intended to ensure cooperation on key challenges in international trade and technology policymaking, based on shared democratic values and respect for human rights.

Subsidies generally undermine the principles, rules and commitments made in trade agreements and WTO law. Due to their frequency, size and complexity, subsidies have in the past brought significant discord to the international rules-based trading system. New industrial policies to promote strategic industries, such US and European chips and car makers, distort international competition and disadvantage smaller and fiscally much more constrained developing countries. This is of particular concern with regard to developing countries, where governments’ appetite for discriminatory treatment of foreigners and measures in support of strategic industries is generally high. By rushing ahead with new subsidies under the umbrella of strategic industrial policymaking, the EU puts itself in the driver’s seat in a process undermining the rules-based trading system. It effectively empowers others to follow suit, backfiring on the ambitions of EU development cooperation and the advancement of its Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the world’s least developed countries. If EU policies give greater power to EU incumbents, this is the perfect springboard for similar policies to be adopted in the developing countries with which the EU partners.

The EU’s strategic autonomy agenda is built on the perception that economic prosperity, technological leadership, and geopolitical power are a function of more and more targeted government intervention. However, no government or agency thereof has ever had superior expertise in steering economic activity in a way that its domestic economy or certain industries outperform the rest of the world. If there is one rule for wide and broad economic success, it is the fundamental commitment to maintaining economic freedom.

This is not to say that there are no good grounds for strategic autonomy ambitions, but EU policymakers need to recognize the trade-offs between isolationist regulatory approaches by the EU and regulatory trends outside Europe, on top of the cost created on Europeans themselves. And they need to factor in serious adverse impacts from strategic autonomy legislation on the international trading system, including the effectiveness WTO rules. The history of economic cooperation suggests that it will become very difficult for the EU to achieve strategic autonomy objectives and at the same time preserve an open international trading system that is embedded in continuous efforts for regulatory cooperation and accepted multilateral commitments.

International cooperation and integration: the aim of our generation

EU policymakers refer to strategic autonomy as the capacity to act. By doing so, two separate areas of policymaking get blurred: in the defence policy strand of the concept, they seek to improve the EU’s military capabilities – a domain that traditionally is government-controlled. By contrast, in economic, trade and technology policymaking, EU policymakers seek lower levels of commercial dependence from actors outside the EU. Key concerns are trade (inter-)dependencies with China and the technological superiority of US technology industries.

Contrary to reaching military strength, improving economic opportunities, competition and broad technological progress are far less dependent on prescriptive policies and strategic state aid. Successes in the domestic economic, innovation and international trade critically hinge on rules that allow for economic freedom, open markets, and vivid competition – the cornerstones of a functioning market economy that in the past contributed to the dissemination and stability of democratic norms globally.

Any strategic economic and technology policy ambition to increase Europe’s capacity to act should aim at increasing the abilities of individuals and firms. For a country or a regional entity like the EU, the capacity to effectively shape outcomes at home and globally – to increase autonomy – depends crucially on policies that harness the energy and ingenuity of many actors. The same conclusion holds for technology and innovation capacities: EU Member States’ capacity to prosper on the back of technology comes from the ability of individuals, firms and governments to deploy global frontier technologies and technology-enabled business models in many different ways.

A political program recognising individuals and firms’ capabilities rather than jurisdictional autonomy will inevitably have to start with the provision of education and human capital. It also requires a strong, perhaps unprecedented emphasis of knocking down regulatory barriers in Europe’s incomplete Single Market, which currently prevent the easy traverse of technologies, goods and services across borders, and hinder European companies, including start-ups, to scale up and become globally relevant.

The economic weight and gravity of Europe in the world is shrinking. Thirty years ago, the EU represented roughly a quarter of global DGP. It is foreseen that in 20 years, the EU will not represent more than 11%, far behind China, which will represent double it, below 14% for the US and at par with India. Neither the EU nor the US will be able to rely on their own market size as the main source of maintaining political influence in the global economy. Other countries, e.g. Japan, are confronted with the same reality. Sure, the EU will likely remain an influential geopolitical actor in global economic policymaking. The “Brussels effect” will likely continue to prevail: the world’s largest corporations will continue to seek access to the EU’s large market by adjusting business conduct and production standards. But with falling relative economic power, Europe will have to improve its capacity to influence global rules by being home to innovative companies. It is not possible to reduce global dependence at the same time as one’s relative economic size is falling.

When quantity does not count in the EU’s favour anymore, at least not in the way it used to do, the EU will have to improve regulatory conditions at home to encourage economic opportunity and innovation and become an example that others want to follow. The Single Market is a strong source of autonomy and influence – it needs to deepen for autonomy to increase. Size and economic gravity matter. With a larger economy that allows for cross-border commerce and technology development, the EU can make itself more attractive as a place to innovate and develop the future economy. And with more economic clout, the EU will also have a stronger voice to influence global norms and standards for technology.

Strategic autonomy ambitions have largely failed to account for adverse impacts on developing countries. In many instances, such as the regulation of data, digital business models, taxation, environmental policies, and technical standards, EU policies either increase the cost of doing business in Europe or explicitly or implicitly discriminate against foreign suppliers. These policies have the effect of generating fewer opportunities for small businesses and suppliers from developing countries, empowering vested interests, such as national incumbents, to engage in lobbying for protectionist policies, and contributing to the diffusion of protectionist policies globally, particularly in countries with weak institutional capacity.

Therefore, strengthening international efforts for trade and regulatory cooperation should be the core component of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda. Regulatory cooperation with allies such as the US and the larger groups of OECD countries is essential to jointly set global standards based on shared values and fundamental rights. At the same time, EU legislators need to account for and preclude negative impacts on developing countries’ trade and technology policymaking and multilateral commitments. EU policymakers need to uphold open trade principles rather than EU-first policies.

Paul-Henri Spaak, the late Belgian Prime Minister, once said that “there are only two kinds of states in Europe: small states, and small states that have not yet realised they are small.” Spaak’s words are often quoted in defence of the transfer of national competences and sovereignty to the EU in exchange of winning political influence in the world – and there is of course truth in this reasoning.

However, another truth is that the world’s most economically open and prosperous countries are small and often very small economies. These economies are much less restrictive and interventionist about international trade and investment. Importantly, they show a substantially higher degree of economic freedom and typically outperform other countries with regard to the quality of governmental institutions and respect for the rule of law. By contrast, the world’s least trade-intensive countries are typically the world’s largest and most trade restrictive countries, which perform worst in economic freedom, governmental institutions, respect for human rights and the rule of law. Countries include Turkey, India, Indonesia, Egypt, Argentina, Brazil, and Nigeria, where interventionist federal policies impede economic growth and structural economic renewal. An important takeaway for EU Member States is to examine their options and ask themselves whether there are better long-term strategies to pursue than those proposed by Brussels, strategies guided by the spirit of the open society – a society embracing the principles of free trade, non-discrimination, and economic freedom.

*This broad classification is inspired by discussions with Frontier Economics. ECIPE commissioned Frontier Economics, a consultancy, with a study to estimate the costs of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda. The study will be released in autumn 2022.