Published

Europe vs United States – Boosting Competition in Space and the Skies

By: Andrea Dugo

Subjects: European Union North-America Regions

We reach for historical images to make sense of our current times. Now that there is increasing competition between firms in the aerospace industry, we think about a time when the US and the USSR competed over the dominance of atmosphere through memorable, headline-making events like the space race or President Reagan’s Star Wars program. There is a fascinating development going on in the aerospace industry – a race which includes firm competitiveness as well as geopolitics – and it also includes sectors like communication and aircraft production. European firms are competing with US firms but, interestingly, there are also wider cross-border networks of firms that collaborate over R&D, innovation and production. What stands out, however, is a transatlantic brawl for superiority in the aerospace industry, and it is a tale of two opposing stories: one where Europe used to be on top but progressively lost its competitive edge in the US’ favour, and the other where the reverse came to happen.

Let us begin with the space industry. After the glorious decades of space exploration, the US held a virtually absolute monopoly on launch services in the West at least through the 1970s. However, far more concentrated in reserving its launch vehicles to government missions, the US failed to foster the development of a real commercial market for the space industry. This is where Europe stepped in. Largely driven by French efforts, the European Space Agency (ESA) started to develop its own launch industry and created in 1980 Arianespace, the world’s first commercial launch service provider. Europe generated a massive market opening for the launch of commercial satellites and soon competitors from the US, China and the USSR, but also Brazil and Japan started to spring up like mushrooms. In spite of the increasing competition, however, Arianespace’s market predominance remained undisputed. In a miraculous achievement for the European space industry, in under 15 years, Arianespace managed to kickstart a commercial space launch market and to command more than 50% of it alone.

Behind Arianespace’s success story was certainly the brilliant intuition to identify a still untapped market segment earlier than others. While the US and the USSR were all too focused on seeing space through a political and military prism, Europeans saw the launch of commercial satellites as a hugely unexpressed market opportunity amid the telecommunications boom, and they were right. On top of foresight is also a more technical explanation. NASA and its contracting companies chose to bet on Space Shuttles for commercial use, in the conviction that expendable launch vehicles would soon become obsolete. Arianespace, instead, opted to make existing launchers viable for commercial purposes as well. Despite NASA’s promises to make the Space Shuttle a cheaper, reusable spacecraft apt for commercial development, technical complexities kept mounting, and the program soon proved too financially prohibitive. The Challenger disaster in early 1986, in which all seven crew members tasked with the deployment of a communications satellite perished when the spacecraft exploded mere minutes after liftoff, put the final nail in the coffin of the Space Shuttle’s commercial career and cleared the way for Arianespace’s dominance.

The combination of market intuition and technological acumen made Arianespace the industry leader for decades, up until the mid-2010s. However, in recent years a similar combination of intuition and innovation has again revolutionised the space industry, this time to Europe’s detriment. The emergence of highly efficient firms with more assertive business models like Elon Musk’s SpaceX has in fact made way for the US to take the lead in the space launch services. Building on the idea of reusability put forth but never materialised by NASA, SpaceX has pioneered an alternative model to traditional single-use launch vehicles that has already reduced low Earth orbit commercial access costs by 90% and could lower them further by some 50 to 80 times in the years to come.

Contrary to common belief – an Arianespace executive in 2013 famously laughed off Musk’s quest for reusability as “a dream,” one that people would eventually “wake up [from] on their own” – SpaceX has been capable of manufacturing fully functional, rapidly reusable rockets by identifying cost reduction as a primary area for innovation. The company has not only reduced costs in physical spacecraft development but also in overhead, support services and development timeframes, and has channelled all cost savings and profits into a continuous funding stream for R&D of more and more advanced, reusable rockets. This prodigiously innovative business model has allowed SpaceX to dethrone Arianespace as the world’s leading provider of launch services in the span of years. The California-based company now handles almost 70% of all NASA’s launches, and even the EU has become overly reliant on SpaceX for its satellite and military intelligence launches due to delays with Arianespace rockets. While the bloc is trying to shed its dependency on SpaceX at least for military and battlefield communications satellites and restore autonomous access to space in this domain, reducing reliance in the commercial market is still years away. It is also worth reminding that SpaceX’s private satellite internet constellation, Starlink, accounts for two-thirds of all active satellites in orbit.

As we have already shown elsewhere, the role of regulation in the shift of power from Europe to the US has also been crucial. According to the director of the ESA himself, commercially driven government procurement policies in the US backed the rise of innovative firms like SpaceX: starting from the mid-2010s, in fact, NASA initiatives have been involving private companies in the development and operation of new space transportation systems that could significantly reduce orbital access costs such as cheap, reusable rockets. On the contrary, the ESA’s restrictive procurement policies, which essentially prioritised Europe’s only existing space industry giant and its antiquated business model, have kept European spacecraft costs infinitely higher hence uncompetitive internationally.

Deeply entrenched in their technological certainties and overly confident in their market leadership position, the ESA and Arianespace failed to anticipate the rise of a more agile and innovative competitor as well as to adapt to a leaner regulatory framework like the one in which SpaceX could operate. As a testament to Europe conceding defeat, the ESA announced in May 2023 a NASA-like call for private European companies to engage in the creation of commercially viable cargo transportation systems.

Let us now turn to the aviation industry, which tells us a different story on Euro-American competition, perhaps a more cheerful one for Europe. In the sector of commercial aircraft manufacturing, the US displayed virtually undisputed superiority until at least the 1980s. Seattle-born Boeing, the world’s oldest airplane manufacturer, commanded alone a 60% or larger share of the global market for commercial airplanes, with other fellow American companies Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas completing the picture. It was not until the late 1960s in fact that a new, non-American competitor would emerge, Airbus. Out of concern that competition from US civil aircraft manufacturers would eventually decimate Europe’s weak and fragmented national aviation industries, the governments of France, Germany, the UK and later Spain joined forces to establish Airbus Industries as a consortium of European aerospace companies. Despite a rocky start, the rise of Airbus all through the 1980s slowly but surely eroded the market shares of both Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas – the former would stop production of commercial airliners altogether in 1981, while the latter merged with Boeing in 1997 – but it left Boeing’s market predominance largely unharmed. Although Airbus had managed to take part in a duopoly with Boeing by carving out a 20-30% share of the world’s civil aircraft market for itself in the first two decades since its onset, the gap with its US rival remained substantial: in 1990, Airbus delivered 95 commercial jets, while Boeing delivered a staggering 449.

The last decade of the 20th century marked the real turning point in the Boeing-Airbus rivalry. The France-based manufacturer stepped up aircraft production and deliveries massively throughout the 1990s. The day the CIA had dreaded would come in a confidential report from 1982 was finally here: in 2003, Airbus overtook Boeing in aircraft deliveries, becoming the world’s largest commercial jet maker. Except for occasional, short-lived recoveries from Boeing, Airbus has stably consolidated its lead in the civil aircraft manufacturing market over the last twenty years. The European company now solidly controls 62% of the global market share, while analysts expect Boeing will never go back to capturing more than 40% of the industry. Company revenues have followed a similar trajectory: in 2000, Boeing still boasted revenues that were almost two and a half times those of Airbus; today, the two are virtually on par. In the same vein, Airbus has stably surpassed Boeing in market capitalisation, and in 2023 the European aviation giant made almost $4 billion in profits, while Boeing generated a $2.2 billion loss.

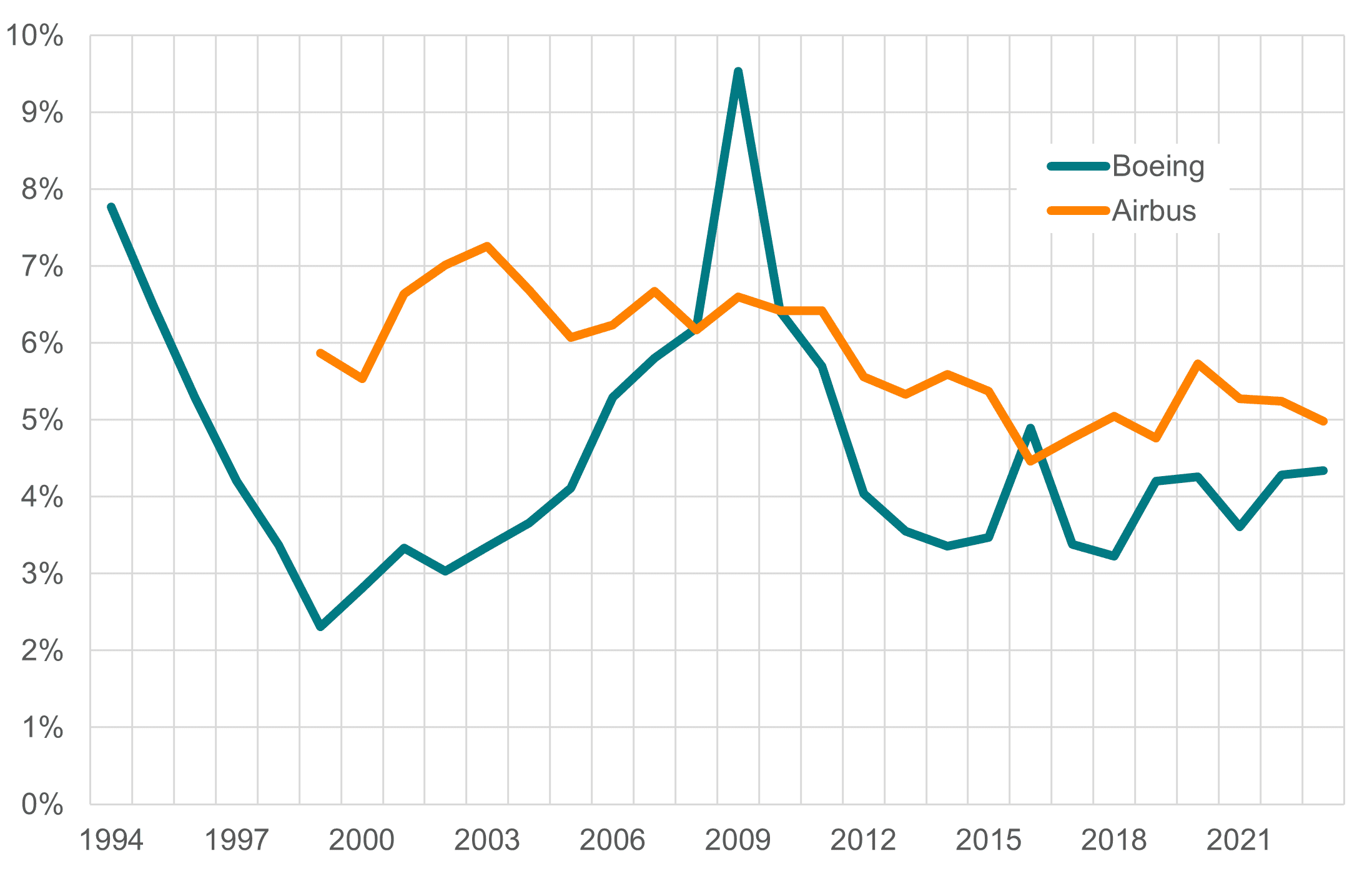

Airbus managed to enter a virtually impenetrable market from scratch and to become the industry leader in under 30 years of existence. This surely stands out as one of Europe’s most resounding corporate success stories in the past decades. Many have credited this memorable business achievement to Airbus’ massive R&D spending endeavour, and not without reason. Figure 1 below plots R&D spending as a percentage of total revenues at Boeing and Airbus over the last three decades. Data on R&D expenditure for Airbus is available only starting from 1999, as the European consortium was officially incorporated into a company only in 2000 and that was when the first Annual Report, with financial information on the previous year as well, was released. Throughout the 1990s, Boeing witnessed a steep decline in the share of revenues allocated to R&D spending from roughly 8% in 1994 to barely above 2% in 1999. On that same year, Airbus’ R&D expenditure accounted for almost 6% of its total revenues. R&D spending briefly picked back up at Boeing in the late 2000s, but it was largely directed towards unplanned expenses for its B787 airliner program and connected company missteps rather than towards actual technological innovation.

Figure 1: R&D expense as a share of total revenues at Boeing and Airbus, 1994–2023 (percentage)

Source: Author’s calculation based on Boeing, Airbus SE and EADS.

Over the 1999-2023 period under examination here, only three times, in 2008, 2009 and 2016, did Boeing spend more on R&D as a share of revenues than Airbus did. Especially since the early 2010s, when Airbus’ revenues essentially came to match Boeing’s, Airbus’ relative R&D advantage became an absolute one too. In raw numbers, over the last decade Boeing has devoted roughly $35 billions to R&D spending, while Airbus has spent almost $40 billions, an impressive 15% difference to the European giant’s favour. Bigger R&D spending has translated into practical technological advancements. Airbus has been the first to pioneer the use of composite materials to build its aircrafts, significantly reducing fuel consumption and increasing range. Similarly, Airbus was the first to introduce fly-by-wire technology in commercial aviation, replacing traditional manual flight controls with electronic interfaces, and allowing for advanced automation and digitalization in both its manufacturing processes and aircraft systems.

Boeing has also put forth a number of groundbreaking innovations over the past decades, yet many seem to point to a general decay of the quality of its products, especially since the turn of the century. The 2018 and 2019 Boeing 737 Max crashes, which claimed hundreds of lives, led to a nearly two-year global grounding of the aircraft. In this regard, the American company has very recently agreed to plead guilty to conspiring to defraud the federal government over these fatal incidents. Some point to a cultural shift within Boeing, dating back to its merger with McDonnell Douglas in the 1990s. These voices have it that, in an attempt to be faster and cheaper than Airbus, the American company has shifted from an engineering-focused approach to one driven by cost-cutting and financial efficiency, resulting in diminished quality control, reduced safety oversight, and a generally lesser ability to innovate.

One should not forget, however, that the scrap for innovation between Boeing and Airbus also conceals a story of government subsidies and distorted competition. Both companies have benefited greatly from public support: Airbus was the outright brainchild of a set of European governments and has been the recipient of massive industrial subsidies from the very outset; US government support to Boeing has often been more indirect, through a mixture of tax breaks and state-funded military contracts. This state aid crossfire has generated a streak of dozens of billions of dollars worth of endless trade fights between the EU and the US, which the two parties agreed to pause in 2021 with a five-year suspension of the tariffs that originated from the dispute. In any case, determining who has been the biggest beneficiary of public assistance is hardly of interest here. The real heart of the matter is that tireless government support from both sides of the Atlantic to preserve this duopoly status quo has likely hindered overall innovation in the aircraft manufacturing industry. Evidence shows that although new technologies were introduced by both Airbus and Boeing in their latest programmes, the growth in R&D expenditure has progressively grown more modest compared to earlier programmes.

The benefits of a duopoly over a monopoly for technological innovation are self-evident as some competition, however limited, is better than no competition at all. As CEO of Ireland’s low-cost airline Ryanair, Michael O’Leary put it, “it is absolutely critical that we have a strong Boeing and that we have a strong Airbus and that the two of them at least compete with each other, not just for orders, but also in terms of technological developments.” However, many caution that the current two-firm arrangement is already holding back genuine, boundary-pushing innovation in the aircraft manufacturing industry, as the competitive pressure to innovate is restricted. Scott Kirby, chief executive of another global air passenger carrier, US-based United Airlines, recently voiced his concern in this regard, and loudly called for more competition in the industry. Most experts, however, believe there is no credible entrant in sight for years that could overhaul the duopoly.

Europeans should not bask in happiness. Airbus, alias Europe, has hands down won the race against Boeing, alias the US, and this conveniently sheds positive light on the Old Continent, at a time when European competitiveness is under close scrutiny. Many might feel emboldened by Airbus’ remarkable performance that industrial subsidies are the way to go. After all, Airbus is one of those “European champions” prominent EU figures like Macron, Draghi, Letta and others have been insistingly alluding to as the panacea to all European competitiveness ills. However, the temptation to resurrect old-style industrial policy to replicate Airbus-like miracles in other industries could not be more misplaced.

The Airbus experience is hardly replicable, and even less desirably so. Firstly, Airbus’ success certainly depends on its own merits but is also largely due to Boeing’s missteps. In a duopoly, the failures of one are the victories of the other; in more competitive industries, the same logic will not apply. Secondly, Airbus is not your average company. In order to win the global competitiveness race with Boeing, Airbus was put on unprecedented state-funded steroids. Even if it were desirable to prop up all sectors by dint of industrial subsidies the same way it was done with Airbus – and it is not for a number of concerns, among which reduced competition, excessive market consolidation and diminished consumer protection – it would make European countries go bankrupt in a matter of minutes. Perhaps even more importantly, though, it is worth pointing out that the success of the Airbus experience is not written in stone. Just like it happened to Arianespace in the space industry, Airbus can also eventually end up falling victim of its technological and market superiority. The risk of complacency is right around the corner. Surely, analysts seem to agree there is no plausible competitor on the horizon in the aviation industry that can threaten Airbus’ lead. Most experts did not anticipate SpaceX’s boom either, yet it happened.

The bottom line is that if there is any lesson on competitiveness to be learnt when juxtaposing Arianespace-SpaceX and Airbus-Boeing parallel yet opposing stories, it is not about subsidising existing corporate leviathans with more industrial policy. It is in fact about creating the right starting conditions for innovation to proliferate. As we have shown profusely elsewhere, a leaner regulatory framework as well as easier access to corporate funding make it so that if a revolutionising, SpaceX-like startup were to arise in the aircraft manufacturing industry, it would most likely be American. Europe’s ultimate competitiveness challenge is not to prevent such a startup from arising to protect Airbus, but rather to ensure that, when it does arise, it is European.