Published

The Costs of the EU’s Strategic Autonomy Agenda – Why Member States Should Stop Ignoring Them

By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: European Union

The EU is pushing a controversial policy paradigm: strategic autonomy. The term is increasingly institutionalised. It is commonly referred to in speeches by high-level officials. New EU laws are infused with the concept and its derivations, such as industrial autonomy or technological sovereignty. Their precise meanings, intentions and actual impacts remain obscure. Brussels seems to be most concerned about which companies operate in the EU and how they exchange products, services and data with the rest of the world. Highlighting political ambitions for autonomy, the European Commission takes many novel approaches to regulation, including new bans, standards, incentives, and deterrents for production and consumption in the Member States.

This short article provides a taxonomy of policies put forward under the Strategic Autonomy agenda. It is argued that stakes are high for EU Member States. EU governments should be more sceptical and critical of the European Commission’s “long-term” plans. So far, the costs of strategic autonomy are greatly understated. Long-term impacts on Member States’ economies and the process of economic convergence and cohesion are largely ignored.

Box 1: Key take aways

Strategic autonomy legislation – a rough taxonomy

In its 2021 Trade Policy Review, the European Commission defines strategic autonomy as “the EU’s ability to make its own choices and shape the world around it through leadership and engagement, reflecting its strategic interests and values.” It largely builds on earlier notions raised by EU and national policymakers ever since Jean-Claude Juncker, the former President of the European Commission, proclaimed in 2018 that now is the “The Hour of European Sovereignty” – the right time for Brussels to globally roll-out EU rules for the deployment of big data, artificial intelligence, and automation.

Political leaders in France and Germany thereupon called for new industrial policies such as data localisation, a European cloud, and even an Airbus for artificial intelligence. Smaller EU countries, such as the Nordics and CEE countries, were generally more reluctant to echo demands for strategic autonomy ambitions in economic and technology policymaking, referring to the merits of interdependences, the international division of labour, and policy coordination with non-EU governments.

In its latest Strategic Foresight Report from June 2022, the European Commission reiterated the desire for EU interventions to “strengthen resilience and strategic autonomy”. Contemplated measures include new rules for supply chains, the sharing of data, and policies conducive to sustainable businesses in the EU. The Commission is building on many initiatives that have already been passed or proposed.

It is difficult to come up with a clear-cut taxonomy of EU policies that are guided by the strategic autonomy paradigm. After all, the term remains a political marketing instrument – a novel way of political storytelling – to renew (lost) trust in EU institutions and centralised policymaking. Moreover, it emerged on the heels of Donald Trump‘s push for “America First“ policies and ambitions by China’s Communist Party to confront foreigners with new market access restrictions. However, we can broadly distinguish recently implemented or proposed EU policies based on central political concerns underlying the strategic autonomy paradigm*. These are:

- EU interventions seeking industrial and trade policy objectives through direct interventions in favour of EU businesses, such as reducing perceived dependencies on non-EU suppliers, underinvestment in R&D, and industrial modernisation (green growth and digitalisation). Interventions are generally geared to conferring advantages to EU businesses over those from outside the EU. Policies include the Foreign Investment Screening Mechanism, State Aid flexibilities, Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEIs), and the Chips Act.

- EU interventions aimed at correcting perceived market failures (primarily) in the EU, including perceived market power and collective action problems (environmental impacts), but also ethical concerns related to fundamental rights. Policies include the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Data Act, the Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the Digital Services Act (DSA).

- EU interventions intended to correct perceived market failures related to production and processing methods with extra-territorial reach, including value chain resilience and environmental standards. Policies include the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence regulation and restrictions to the free cross-border flow of data as provided in the Data Act and the GDPR.

- Contingent interventions in response to trade measures or behaviour by non-EU governments, including responses to perceived trade restrictive or distortive policies, or actions sought to remedy what the EU perceives to be a shortcoming in the multilateral toolkit. Policies include the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and the Foreign Subsidy Instrument, and the revised Trade Enforcement Regulation.

Strategic autonomy – at what costs?

This taxonomy provides a preliminary framework to understand contemporary EU policymaking. It helps capturing key motivations behind the EU’s most recent agenda. It can also help to disentangle and better understand the origins, magnitudes and distribution of costs and benefits that the strategic autonomy “acquis” can create for businesses and citizens in the Member States.

Strategic autonomy regulation is typically justified by benefits to the public, such as a higher level of consumer protection, such as lower prices and reliable supply, but also ethical and environmental considerations. The costs of regulation are typically borne by businesses that must comply with it. Costs arise from mandated changes in production, distribution and sales practices, and from legal uncertainties related to the way regulation is designed and enforced. Regulation therefore also impacts on how companies trade and compete internationally, including incentives to innovate, access to foreign knowledge and technology, and the ability to scale across borders. On top of that, there are public policy spill-over effects: regulation can be mirrored by other countries, sometimes as a means of retaliation.

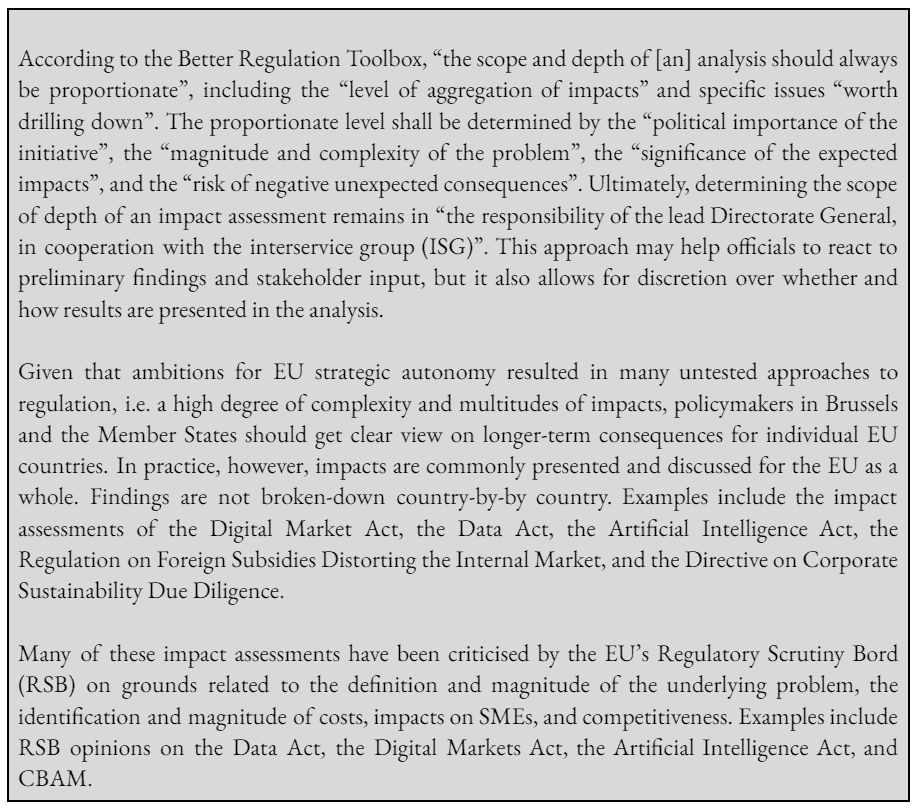

Most of these impacts are – formally – accounted for by the EU’s Better Regulation Toolbox. The Toolbox provides the official methodology for assessing European Commission-initiated laws and regulations. It is meant to ensure a solid review of potential impacts of different policy options and who will be affected.

Short-term compliance and adaptation costs are typically well-accounted for in these assessments. By contrast, indirect and long-term costs are often neglected, marginalised or entirely ignored. This is because the toolbox provides the European Commission with great discretion over the scope and depth of impact assessments. It allows policymakers to give different weights to stakeholders’ input, and it allows to assess the impact of new measures on the EU as a whole, without investigating benefits and costs on a country-by-country basis (see box below). Important indirect and long-term costs include changes in prices, availabilities and qualities of products and services, but also forgone investments and impacts on market access, innovation, and competitiveness.

Box 2: Discretion over the scope and depth of EU impact assessments

Long-term ambitions require an understanding of Member States’ economies and obstacles to economic development

New EU rules, bans, incentives and deterrents can set the course for the development of EU industries and economies for a very long time. Simply speaking, in the long term, there could be winners, but there could also be losers, within the EU.

With its strategic autonomy agenda, the EU is pushing for new, often EU-only, and often untested regulation. It does so without taking into consideration the economic specificities of individual EU countries. A common assumption by policymakers is that the European Union can be treated and regulated as single country whose regions are characterised by similar production patterns, equal access to capital, skilled labour and knowledge, and about same level of purchasing power. But the EU is not, nor is it likely to be in the foreseeable future. EU Member States’ economic structures vary substantially across the EU, explaining differentials in the path of economic development, citizens’ preferences for international trade and investment, and the actual readiness of companies to comply with new EU regulation.

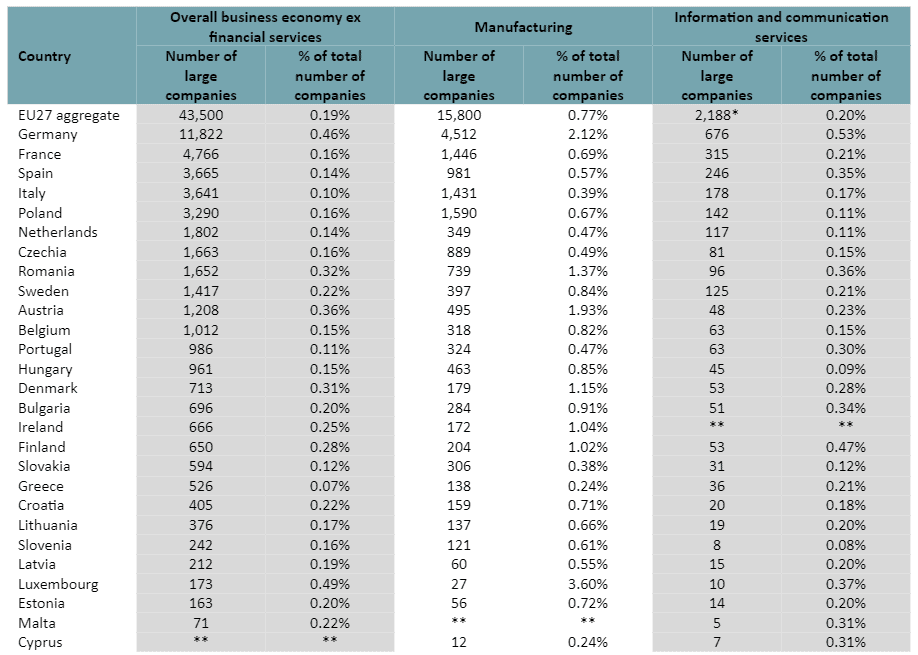

A look at the EU’s structural business characteristics database reveals that large Western European Member States are home to a much larger number of big businesses compared to small EU countries (see Table 1). Large companies are generally much better equipped to adapt and comply with new regulatory requirements. Some large companies may even benefit from policy-induced entry barriers as they reduce exposure to competition and contestability (incumbent protection). EU impact assessments are typically silent about these effects.

Table 1: Distribution of large companies in EU27 countries in industries key to the EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm

Source: Eurostat annual enterprise statistics by size class for special aggregates of activities (NACE Rev. 2). Large companies: companies with 250 persons employed or more. * 2016 value. ** indicates data gap.

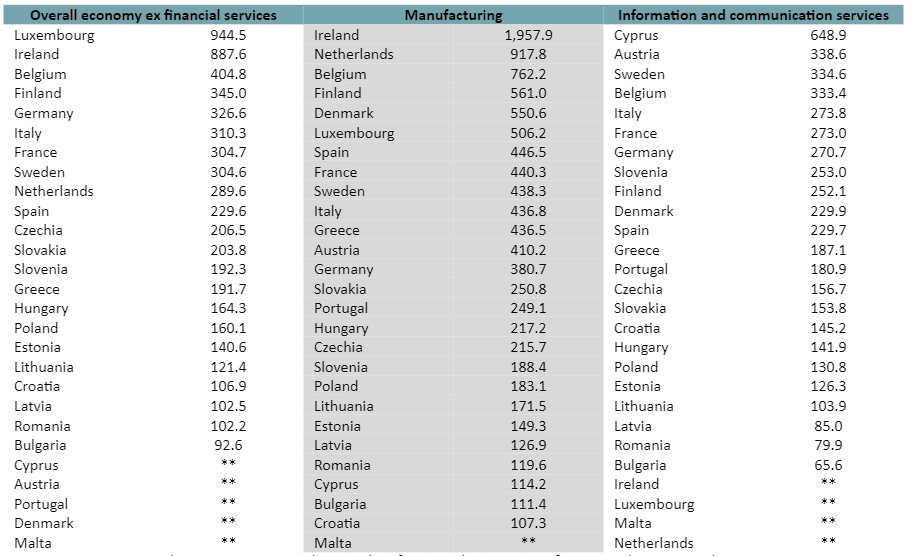

Large companies in large Western European Member States are generally much more productive and internationally competitive compared to companies in small EU countries, notably in sectors that are targeted by key strategic autonomy initiatives, such as manufacturing and ICT industries. Big businesses in France and Germany, for example, show significant comparative advantages compared to companies from economically less developed EU countries, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE, see Table 2). At the same time, smaller countries in Western Europe and the Nordics are home to some of the most competitive large companies in the EU and globally, particularly in technology-intensive sectors such as the biopharmaceutical industry, advanced manufacturing, and ICT. These patterns are also reflected by the location of large R&D-driven companies in the EU. As shown by the EU’s latest investment scoreboard, 124 of the world’s top 2,500 R&D investors are based in Germany and 66 in France. 34 each are registered for the Netherlands and Sweden. Only two are based Portugal and one in Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland respectively.

Table 2: Turnover per person employed of large companies in EU27 countries in industries key to the EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm

Source: Eurostat annual enterprise statistics by size class for special aggregates of activities (NACE Rev. 2). Large companies: companies with 250 persons employed or more. ** indicates data gap.

The regional and sectoral distribution of companies in the EU has implications for the size and distribution of benefits and costs in the Member States. These costs go beyond direct compliance costs. Complex rules for new products and services or data create a multitude of downstream economic effects, notably for SMEs. SMEs account for much higher shares of economic activity in small EU Member States compared to large EU countries. For example, a European Cloud Certification Scheme together with restrictions on the transfer of data would likely increase the economic clout of large incumbent companies in large Western European countries, but increase small businesses dependencies on them. It would reduce choice and economic opportunities in small countries and impede the process of economic convergence in the EU. Subsidies are another case in point: the Chips Act (for which “an impact assessment could not be prepared due to the urgency of an initiative”) would disproportionally benefit incumbents and investors in large EU Member States, at the cost of businesses and taxpayers in small EU Member States.

New initiatives towards “European standards” and the management of “EU value chains” could also disproportionally impact small EU Member States. A recent study from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy focuses on increases of market access barriers in the EU and regulatory heterogeneity (regulatory decoupling). The authors investigated the trade impacts from preferential public procurement rules, tax breaks, other subsidies for EU suppliers, as well as import quotas and bans on selected goods. Large countries with a high exposure to international trade, such as Germany and France, would indeed suffer high absolute losses in domestic production and trade. At the same time, small countries, such as Ireland, Malta, Belgium and the Baltics, would be more strongly affected in relative terms, with losses being largest if non-EU countries were to mirror EU policies or retaliate. Small businesses in the EU will find it harder to do business in non-EU countries if governments increase market access barriers through new regulation of regional standards that are difficult to comply with (prohibitive). Negative impacts from regulatory diffusion and retaliation, which accumulate over time, are usually ignored in EU impact assessments.

Comprehensive country-by-country impact assessments are needed in the EU

The global economy is constantly undergoing a process of transformation, becoming more digital, more collaborative, and producing a larger diversity of products, services, and technologies. Many policymakers in Brussels take a command-and-control view on autonomy and regional sovereignty, arguing that the EU or individual Member States need to have the policy instruments to control the outcomes of economic transformation and how Europeans do business and use data and technologies. Policies that originate from this hypothesis can have a lasting impact on Member States’ economies.

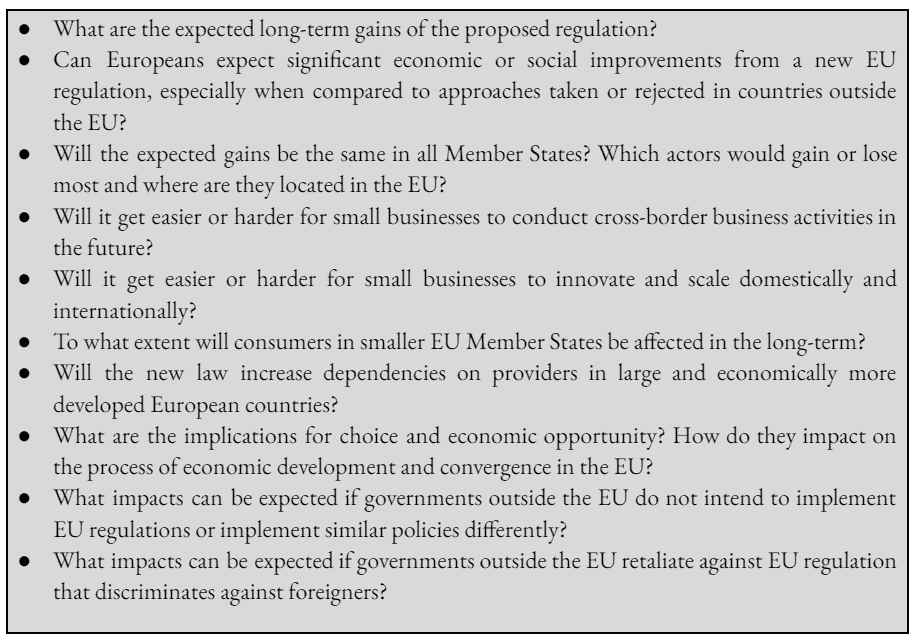

EU impact assessments so far fail to provide a prudent picture of the long-term impacts that result from new EU initiatives and regulations. Policymakers in small EU Member States should not make any far-reaching decisions based on EU impact assessment reports that ignore, obscure or downplay these impacts. They should start challenging the European Commission’s discretion over the depth and scope of regulatory impact assessments. EU governments should insist on detailed country-by-country assessments addressing key questions for long-term ambitions (see Box 3).

Box 3: Key questions for country-by-country assessments of strategic autonomy ambitions and initiatives

*This broad classification is inspired by discussions with Frontier Economics. ECIPE commissioned Frontier Economics, a consultancy, with a study to estimate the costs of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda. The study will be released in autumn 2022.