Why Concluding CETA is so Important for the EU

Published By: Erik van der Marel

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements North-America

Summary

Passions have been running high this week as the EU failed to get an agreement about signing off its trade deal with Canada, what is called CETA. As it stands now, some countries remain critical of the deal, or cannot sign the deal because of internal political differences. Whatever those reasons may be, they should think twice. Other countries have been catching up with the EU in the past decades and are already today more attractive places to trade with.

Background

Trade agreements are concluded with one simple goal: to lower the costs of trading between countries. In other words, the objective is to lower the costs of imports and exports of goods, with the view of staying competitive in the world. The most efficient way of doing this is through the multilateral system. If that doesn’t work, trade costs could be lowered between countries directly, i.e. through bilateral or regional trade agreements.

The CETA agreement is no exception. The aim is to lower the costs of the many importers and exporters between the two parties. By lowering these costs by cutting tariffs and non-tariff measures, firms get better and easier access in each other’s markets, ultimately driving up the welfare of a country.

Importantly, there are costs and risks associated with not doing trade agreements when other countries are. If countries do not lower these trade costs, or when doing so insufficiently, trade may actually be diverted to other countries which do provide these lower costs over time. Therefore, an agreement between the EU and Canada would just not improve Europe’s trade position; failure to do so will have direct costs.

Using data from the ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database one can precisely uncover the evolution of trade costs between each pair of countries in the world, including the one between the EU and Canada. In this database, the bilateral trade costs measure is truly comprehensive so that it includes all types of costs involved in trading goods with another partner, including indirect costs associated with differences in languages, currencies as well as cumbersome import or export procedures.

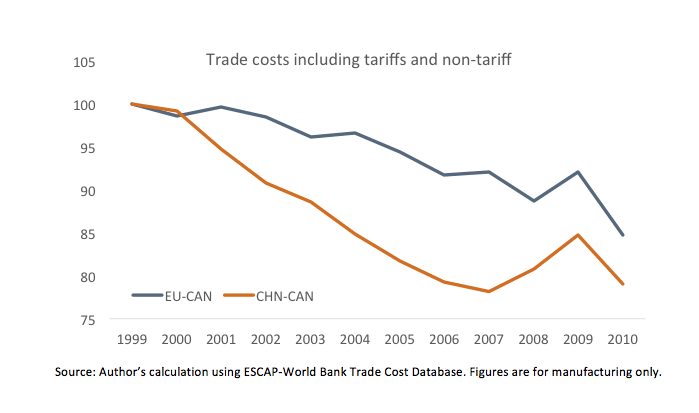

The figure below shows that trade costs between the EU and Canada have been decreasing over time starting from a common base, i.e. 100, as illustrated by the dark blue line except during the Global Financial Crisis. Note that trade costs include tariffs as well as non-tariff measure. This picture shows a rather good sign and therefore one may wonder why a trade agreement is necessary in the first place.

The answer to that is related to the orange line, which denotes the trend of trade costs between China and Canada. Trade costs between these two countries have been decreased more rapidly over time suggesting that it has become more advantageous for Canada to deal with China than with the EU.

One question is whether the stronger decrease of China’s trade costs pattern is not influenced by starting from a greater level of costs. In fact, this is not the case. For instance, in 2010 trading between the EU and Canada was still 48.60 percent more expensive based on an ad valorem (tariff) equivalent.[1]

What is the explanation? One obvious reason is that many countries in the EU – e.g. Romania, Bulgaria or even Austria – still have very high trade costs compared to other countries. These are also the countries that have voiced some objections to CETA.

However, although other countries such as France or Germany have lower bilateral trade costs with Canada, their trade costs have not been reduced over the years. On the contrary, they have remained relatively stable, suggesting that these countries have not done much in terms of trade policy reforms.

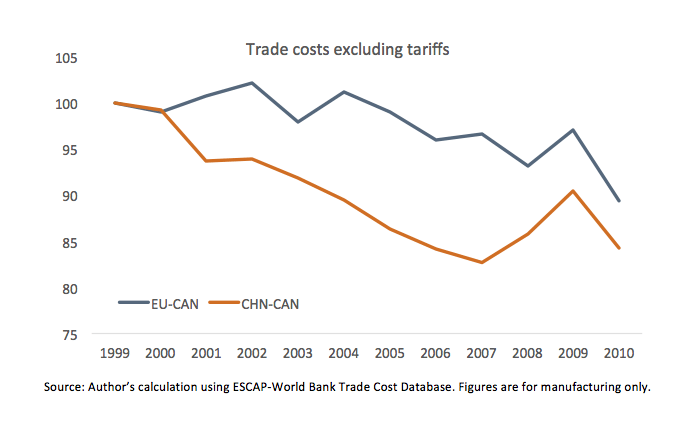

A final issue is that many of the trade costs barriers that CETA intends to tackle are of a non-tariff nature, which may therefore alter the picture of the trend of trade costs. However, the picture doesn’t seem to change much in terms of the general pattern: non-tariff trade costs between China and Canada are going down at a faster rate than between the EU and Canada. And again, it is not because it is so much more expensive to trade with China in the first place.

In all, the EU would do well to sign off the trade deal with Canada. CETA is supposed to be a progressive deal that tackles not only tariffs but also many non-tariff measures that that reduce market access and the general improvement of competitiveness. The EU is not the only trade entity in the world. Other countries are catching up and becoming a more attractive place to trade with.

[1] Note that this percentage as well as its indexed trend in the figure is an average tariff-equivalent for all manufacturing goods, some of which may not be traded (or very little) in practice due to prohibitively high trade costs.