What Will Happen to U.S. Trade Policy When Trump Runs the Zoo?

Published By: Craig VanGrasstek

Subjects: North-America

Summary

What kind of political animals will be making U.S. trade policy in the Trump administration? The tone of the campaign suggests that the president-elect will act like a bull in the China shop, but his bellicose roars may instead presage a subtler strategy; it is also possible that his own business interests will influence the direction of U.S. policy. His abandonment of free trade and other Republican orthodoxies will force members of that party to decide whether to act like principled elephants or obedient sheep, even while Democrats choose between being opportunistic jackasses or stubborn mules. And in deciding where to direct its trade negotiations, the Trump administration may aim not just for big game like the United Kingdom and Japan, but could also have a few black swans in its sights. These might include such surprising partners as India, Taiwan, the Philippines, MERCOSUR, and perhaps even Russia.

Introduction

“Man is by nature a political animal,” Aristotle told us in Book I of Politics, but precisely what sort of beasts will be making U.S. trade policy in the Trump administration? What do we know — or believe we know — about how the new government will handle trade disputes and negotiations? This note explores where U.S. trade policy may be headed during 2017-2020. It does so more by clarifying the questions and identifying the possibilities than by venturing definitive answers.

The questions are at once more pertinent and more baffling than they have been for any incoming administration in living memory. The political profile of trade policy had declined sharply in the decades that followed the divisive NAFTA ratification debate of 1992-1993, only to come back with a vengeance in 2016. Both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders put trade skepticism at the top of their campaign themes, appealing to rising concerns over economic decline and the costs of globalisation. But as voluble as Trump’s message was on trade, it was light on detail. We know much more about what he opposes than what he will propose. He came out against trade agreements both retrospectively (NAFTA) and prospectively (TPP), deemed the WTO “a disaster,” and threatened to impose tariffs on China and Mexico. Yet apart from a post-election promise to negotiate bilateral trade pacts, and a reiteration of his threat to penalize companies that send their production off-shore, he has thus far offered few specifics on what he would erect in place of the existing network of laws and agreements.

The first question is how Trump and his team will translate the jarring poetry of his campaign rhetoric into the concrete prose of policy. Will he act like a bull in the China shop, rampaging through the trading system, or are his bellicose roars the prelude to a subtler strategy? And how will the two parties Congress respond? Trump’s abandonment of free trade and other Republican orthodoxies will force members of that party to decide whether to act like principled elephants or obedient sheep. His opposition to NAFTA and the TPP will tempt just as many Democrats to be opportunistic jackasses, even if they prefer to be stubborn mules on other issues. Legislators will approach these questions not just with an eye on the 2016 results, but also on the prospects for Democrats to retake Congress in 2018 and for traditional Republicans to retake their party in 2020.

American trading partners must likewise decide how to respond to the new environment. Trump may accelerate both of the trends that have bedeviled the WTO for years, namely the twin proliferation of disputes and discriminatory initiatives, but in quantities and with qualities that could threaten the very fabric of the system. The question also arises as to what countries might be in line to negotiate free trade agreements (FTAs) with the United States. The Trump administration could start by picking over the remains of the TPP and TTIP, eyeing expanded U.S. exports to the Japanese and British markets. There may also be some black swans in its sights, potentially including such surprising partners as India, Taiwan, the Philippines, the MERCOSUR countries, and perhaps even Russia.

What Kind of Political Animal Will Trump Prove to Be?

The Chinese calendar tells us that 2016 was the year of the monkey, and observers of the presidential campaign might well conclude that those old Taoists were on to something. That same zodiac designates 2017 as the year of the rooster, a rather fitting description for a man who often starts his mornings with a Twitter rant. Depending on the precise strategy that Trump and his people adopt, however, the coming season of presidential trade politics may bear a closer resemblance to the year of the bull, the goat, or the pig.

Option 1: The Bull in the China Shop

Trump’s first option, and the one most clearly implied by his rhetoric, is to charge like a bull through that China shop that we know as the trading system. Should he do so, many of the norms, rules, and institutions that seem permanent could prove to be remarkably fragile. Almost the only things that can be said with near certainty about trade policy under a Trump administration are that it will be rhetorically mercantilist, being focused more on outcomes (exports and jobs) than on opportunities (open markets and nondiscrimination), and that he will gleefully challenge the status quo. Trump has repeatedly shown that he prizes his image as a disruptor and an outsider, views unpredictability as a virtue, and revels in challenging even elementary principles of constitutional law and statecraft. There is no reason to expect a man who does not feel bound by the rules to accept uncritically the twin foundations on which U.S. trade policy has rested since the time of Franklin Roosevelt, namely that protectionism is economically self-defeating and that U.S. security interests are best served by an open trading system.

If Trump decides to overturn the system as we know it, U.S. trade law will offer him the means to do so almost unilaterally. He may not only walk away from current negotiations but undo agreements that are already in place, and can make vigorous use of trade laws that allow a president to restrict imports on a variety of pretexts.

One peculiarity of American treaty practice is that presidents have greater powers to abrogate agreements than they have to implement them. Congress has the last say in the approval of new international agreements, whether they are handled formally as treaties (thus requiring the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate) or as congressional-executive instruments (as in the case of those trade agreements that are approved under trade promotion authority), but the legislative branch can be largely bypassed if a president wishes to do away with an existing pact. The only strict rules constraining his authority to pull out of NAFTA, the WTO, or other pacts and institutions are those in the agreements themselves.[1] Congress may need to enact conforming amendments for the withdrawal to take full effect, and injured industries may bring cases to the courts, but it is difficult to foresee congressional critics or private complainants prevailing over a determined executive. Canada and Mexico clearly understand this point, as demonstrated by the almost obscene celerity with which they signaled their willingness to renegotiate NAFTA.

If Trump wants not only to knock down existing agreements but to raise new barriers he could revive some long-dormant provisions of U.S. trade law. One is the global safeguards law (section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974), which was frequently invoked from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s to impose tariffs and quotas on fairly traded but injurious imports. Another option is the reciprocity law (section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974), under which the U.S. Trade Representative has the authority to retaliate against foreign countries’ practices that violate (self-defined) U.S. rights. This law was employed in many high-profile disputes in the 1980s and early 1990s. Trump also promises to declare China a currency manipulator under section 3004 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, a designation that would trigger bilateral negotiations and might eventually lead to sanctions. These and other unilateral instruments[2] appeared to have been defanged by the results of the Uruguay Round (1986-1995), which effectively “reformed” safeguard actions out of existence, replaced unilateral action under section 301 with a much-strengthened Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) in the WTO, and seemed to render other statutes moot.

The laws nonetheless remain on the books. The only real restraint on a president’s use of them, apart from some procedural requirements (e.g., that the U.S. International Trade Commission advise on safeguards),[3] has been the preference shared by three successive administrations for multilateral over unilateral solutions to trade disputes. One could well imagine immediate and vigorous challenges in the DSB if the Trump administration were to reverse that preference and take a “broad-shouldered” approach to the exercise of these powers, but that might only make the U.S. threats to withdraw from the WTO move from implicit to explicit.

Option 2: The Goat in the Living Room

Another possibility suggests that Trump is pursuing a goat-in-the-living-room strategy. Josef Stalin is reputed to have pioneered a political technique whereby a leader manages to deflect opposition to one unpalatable initiative by tying it to another, even less desirable outcome. According to this (probably apocryphal) tale, Stalin is supposed to have ordered both an increase in taxes on the peasantry and a requirement that all peasant families keep a goat in the living room. Some time later he rescinded the second half of the order, and people were so relieved to shoo the goats out of their homes that they almost forgot about the taxes. It is similarly possible that Trump’s threats are intended more to create chaos and leverage than to telegraph his real intentions, and that the ultimate effect of his rhetoric will not be wanton destruction but verbal irritation (i.e., it makes America grate again).

We have already seen two post-election examples of how Trump’s threats can be effective, starting with the aforementioned Canadian and Mexican offers to renegotiate NAFTA. There is no chance that Mexico would have agreed to pay for a wall, and the wall itself may end up being composed as much of fencing and metaphor as it is of brick and mortar, but the Mexicans may nonetheless feel relieved if all they have to do is adjust the terms of NAFTA on a few of Trump’s pet issues (e.g., his claim that Mexico’s value-added tax system amounts to an export subsidy). The deal that Trump brokered with Carrier offered another manifestation of this strategy. He cajoled this heating and air-conditioning company to reverse its plans to move a furnace plant from Indiana to Mexico, saving a thousand or so jobs at a cost of $7 million in state government tax incentives. Trump employed at least two threats to secure this deal: to impose tariffs or other restrictions on any units that Carrier might produce in Mexico and export to the United States, and to deny future military contracts to Carrier’s larger parent company (United Technologies). He has followed up this victory by warning in a series of tweets that “any business that leaves our country for another country” will face retribution in the form of a 35% tax on any imports it seeks to bring back into the United States.[4]

Trump may hope that other U.S. partners will be so dismayed by similar acts of intimidation — whether that means threatening to tear up existing FTAs, or to withdraw from the WTO, or to take all manner of WTO-illegal action — that they can be bullied into passively accepting other, less apocalyptic outcomes. Or to shift the metaphor, it is possible that the U.S. negotiating style under Trump will amount to a variation on the good cop, bad cop game that American statesmen have used so often (and so successfully) for generations. The difference comes in who plays the bad cop: That role has traditionally fallen to Congress, but the next U.S. Trade Representative might instead point to the White House as the home of the madman who must be appeased.

Option 3: A Pig at the Trough

Both options reviewed above start from the assumption that Trump will be motivated by the desire to produce results for his political base. Yet a third possibility is that his priorities will be set, or at least influenced, by how they affect his own empire. This issue drew remarkably little attention during the presidential campaign, apart from failed efforts to force the release of Trump’s tax returns, but now receives close scrutiny. That is due in no small measure to the stunningly tone-deaf approach that Trump and his children have shown during the transition, as exemplified by incidents that individually appear trivial but collectively raise troubling concerns (e.g., Ivanka Trump sitting in on a meeting between her father and the Japanese prime minister and Trump urging British politician Nigel Farage to help settle a dispute between one of his golf courses and Scottish authorities). Legal scholars generally concur that the statutes governing conflicts of interest do not apply to the president, but also point to concerns over appearances in general and the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution[5] in particular.

Although Trump has pledged to withdraw from his businesses, many commentators wonder how any paper barriers between himself, his children, and the family holdings can prevent the cross-contamination of public and private business. The greater danger to Trump is that even his supporters may perceive him to have gone back on his promise to “drain the swamp” of Washington corruption. If the Democrats recapture a majority in the House of Representatives (see below) they could conduct hearings during the 116th Congress (2019-2020) on real or perceived corruption on the part of Trump, his family, or his associates. Trump need only think back to Republican investigations of Hillary Clinton’s emails to realize just how damaging this sort of political theater can be.

There are at least three ways that Trump’s business interests and executive responsibilities could come into conflict. The most problematic would be if Trump were to take actions that directly benefitted his businesses. One would hope that he would be able to avoid tawdry temptations, and yet some of Trump’s own statements imply otherwise. This point is taken up in the concluding section of this analysis, reviewing the possibility that Trump’s choice of FTA partners might be influenced by the localities of his business interests. A second possibility is that foreign governments will cross that line in order to curry favor. That might involve anything from booking rooms at the new Trump International Hotel in Washington, D.C. to extending favorable treatment to Trump-affiliated facilities in their countries. Some foreign leaders have already signaled a willingness to play this game. See for example the decision of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte to appoint real estate magnate José E.B. Antonio, who is building Trump Tower Manila, as a special trade envoy to the United States. Yet a third possibility would go in just the opposite direction, in which foreign actors — state or non-state, national or sub-national — might try to pressure or punish Trump by subjecting his buildings to anything from lawsuits and regulatory harassment to protests, vandalism, and terrorism. Given Trump’s thin skin and vindictive nature, one can only imagine how he might respond the first time protestors in some foreign country decide to trash (or worse) a tower with his name on it.

[1] For example, NAFTA Article 2205 provides that, “A Party may withdraw from this Agreement six months after it provides written notice of withdrawal to the other Parties. If a Party withdraws, the Agreement shall remain in force for the remaining Parties.” The somewhat wordier counterpart to this provision in WTO Article XXXI likewise provides for a six-month notification period.

[2] Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows the president to impose tariffs and/or quotas for up to 150 days against countries with large balance of payments surpluses. There are also circumstances in which he might use the expansive powers granted under the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977. Still more instruments would allow him to restrict imports under section 406 of the Trade Act of 1974 (in cases where imports from a Communist country are alleged to cause market disruption) and section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (which allows restrictions on imports for reasons of national security).

[3] A president cannot impose restrictions under the safeguards law unless the USITC first determines that rising imports are a substantial cause of serious injury. But while the commission then recommends what specific remedies might be imposed, presidents have great leeway in accepting, rejecting, or modifying those recommendations.

[4] Text of the tweets at Ylan Q. Mui, “Trump warns of ‘retribution’ for companies that offshore jobs, threatening 35 percent tariff” (December 4, 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/12/04/trump-warns-of-retribution-for-companies-that-offshore-jobs-threatening-35-percent-tariff/?utm_term=.2c5d15800296.

[5] Article I, Section 9, Clause 8 of the Constitution provides in relevant part that, “[N]o Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under [the United States], shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.”

What Kind of Political Animals Will Members of Congress Prove to Be?

While there are some things that a president can do unilaterally in trade policy, such as withdrawing from existing agreements, the most significant options — especially the negotiation and approval of new agreements — require congressional assent. Here Trump will initially enjoy the advantages of unified government, with Republicans having retained control of both houses of Congress in the 2016 elections, but he cannot count on that lasting beyond 2018.

The reemergence of trade as a high-profile political issue will require both parties to address the widening gaps between their electoral bases and their elected officials. This is not the first time that has happened. From the 1860s through the 1960s, one of the few constants in American politics was that Republicans were the party of protection and Democrats were the party of free trade. Their twin turn-abouts in the 1970s and 1980s can be traced to declining U.S. competitiveness, which led to an increase in imports from lower-wage countries (making labor and Democrats reassess their views) and an exodus of investment capital to foreign countries (forcing a similar gut-check on business and Republicans). The final transition took place during the Reagan administration (1981-1988), which began with the president protecting sugar, textiles, steel, and automobiles, and ended with him reaching an FTA with Canada and launching the Uruguay Round. The partisan realignment on trade seemed only to deepen in each subsequent administration.

Trump will be the first Republican president to espouse decidedly protectionist views since Herbert Hoover left office in 1933. We should not expect the parties to execute yet another complete reversal of their polarities, but his election clearly challenges both of them. Republicans must decide whether to stick by their principles, which could incite conflicts with the White House and estrange working-class voters. The calculations for Democrats are equally difficult. Polling data suggest that their own base has gradually grown more supportive of trade liberalization, even while Democratic office-holders have deepened their opposition to it.

Will Congressional Republicans Be Principled Elephants or Obedient Sheep?

Under normal circumstances, a newly elected Republican president could expect virtually automatic support from a Republican-controlled Congress. The present circumstances are anything but normal. Trump won the presidency first by executing a hostile take-over of the party, then by running on a platform that concurred with only some of its established positions. Protectionism is one of a passel of issues in which Trump has shown his disregard for core Republican principles. These include limited government, fiscal responsibility, constitutional restraints on presidential authority, a level playing field for private enterprise, and distrust of foreign dictators. Trump’s prospects for success, especially in the 115th Congress (2017-2018), will depend to a considerable degree on how willing Republican legislators are to support actions that they would heartily condemn if taken by a Democratic president. How many of them will opt to act like principled elephants, standing up to the president when his initiatives run contrary to their orthodoxy, and how many of them will choose instead to be obedient sheep?

The mixed reactions to Trump’s Carrier deal suggest that at least some of these elephants have short memories. A few have expressed their misgivings about this arrangement, as well as his proposed tax on corporations that relocate off-shore, but others do not seem to recall that theirs is supposed to be the party that opposes crony capitalism and government intervention in business decisions. Another important test may come early next year, when Republicans in the House will decide whether to renew their opposition to earmarks in the allocation of infrastructure funds. Republicans have long contended that earmarking specific projects in a legislator’s constituency is a corrupt practice. Some members moved immediately after the election to reverse that position. House Speaker Paul Ryan, whose own relationship with Trump is very much a work in progress, convinced them to postpone this vote until 2017. Equally important for the trading system is how far Congress will go in making the new infrastructure appropriations subject to Buy American rules. They will also have to decide how they can reconcile this increased spending with decreased taxes and their insistence upon a balanced budget.

The experience over the past year and a half suggests that, as a general rule, the depth and duration of a Republican’s principled stands against Trump will be determined by the degree to which that person’s livelihood and political fortunes are entangled with his. At one extreme are those commentators and intellectuals who are aligned with the Republican Party but remain financially and professionally independent. Columnists such as David Brooks (New York Times), William Kristol (Weekly Standard), and George Will (Washington Post) fall in this category, as do free marketeers in the constellation of right-leaning or libertarian think tanks. The same may be said for the Koch brothers, who have long dipped into their deep pockets to support Republican candidates but now seem wary of a man who has less money and fewer scruples than they do. Many members of the party’s foreign policy establishment took similarly principled stands early in the nominating process, signing letters in which they pledged not to serve in any Trump administration,[1] but some among them are now walking back those views; whether they are doing so out of patriotism or professional necessity is a matter of debate.

As for Republican elected officials, their willingness to stand up to Trump is partly determined by how often they face the voters. Members of the House of Representatives are subject to election every two years, and many of them feel compelled to support Trump even if that is not their personal inclination. Senators and governors, by contrast, are up for reelection less frequently.[2] Several of them have made clear that Trump cannot take their support for granted. That independence may be especially high on the part of those who will not face the voters until 2022, or do not expect to do so ever again, or may be prepared — perhaps even eager — to challenge Trump for the nomination in 2020.

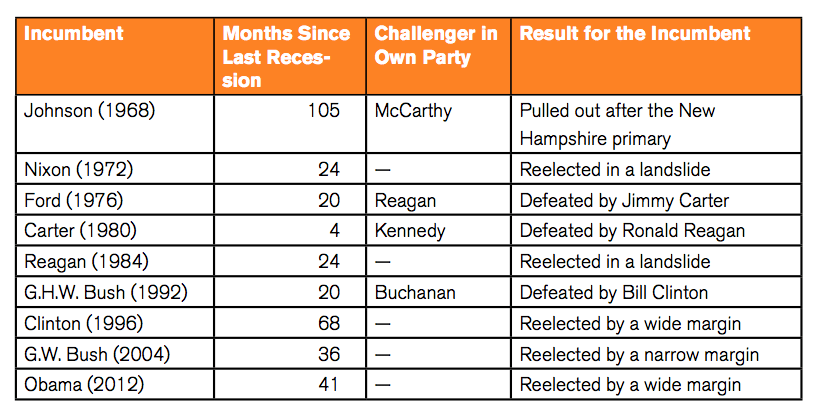

Table 1: Election Outcomes for Incumbent Presidents Seeking Reelection, 1968-2012

Months Since Last Recession = Time elapsed between the end of the most recent recession and Election Day.

Source: Recession dates from National Bureau of Economic Research at http://www.nber.org/cycles.html.

Trump cannot escape a simple fact of American political life: Presidents who do not maintain party unity are often held to single terms. The data in Table 1 show that in the past half-century every incumbent president who has faced a credible challenge for his own party’s nomination — and only those unfortunates — has been denied a second term. It is in this light that we might consider the praise he has received for bringing former critics into his administration. A leader should keep his friends close and his enemies closer, and the best way to forestall opposition is to give jobs to potential challengers. The clearest demonstration thus far came when Trump nominated Governor Nikki Haley of South Carolina to serve as ambassador to the United Nations. A similar logic applies to his decision to nominate Elaine Chao, the wife of Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, as his Secretary of Transportation.[3] It appeared for a time that Trump might also invite Mitt Romney inside the tent, but in the end he could not resist the temptation to humiliate — and seriously compromise — a once and possible future rival.

There are not nearly enough posts within Trump’s gift to buy off every potential challenger, and several leading Republicans may prove to be thorns in his side. Senator John McCain (Arizona) felt obliged to keep silent about Trump during the campaign, but now that this octogenarian has been reelected to a six-year term he is free to express himself. McCain is especially unhappy about Trump’s closeness to President Vladimir Putin of Russia, and Senator Lindsey Graham (South Carolina) seconds those concerns. McCain and Graham seem prepared to make their stand by opposing the nomination of Rex Tillerson to head the State Department, an issue for which they may recruit the support of Senator Marco Rubio (Florida). Similarly, Senator Rand Paul (Kentucky) made clear that he would use his own perch on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to oppose the nomination of Rudy Giuliani to that same job. Other Republicans who may prove troublesome include senators Rob Portman (Ohio), Jeff Flake (Arizona), and Tom Cotton (Arkansas), governors John Kasich (Ohio) and Larry Hogan (Maryland), and many office-holders from the two Bush presidencies. These include some former trade officials (notably Bill Brock, Carla Hills, and Robert Zoellick) as well as others who held higher offices (e.g., Colin Powell and Tom Ridge).

While each of these worthies is prepared to oppose Trump on at least one issue, it remains to be seen which Republican may step forward to champion free trade. Candidates include Speaker Ryan, Chairman Kevin Brady (Texas) of the House Ways and Means Committee, and Chairman Orrin Hatch (Utah) of the Senate Finance Committee. Each of these men have spoken out regarding the Carrier deal and/or the threat of a trade war, but they also have other issues on their plates. These include a new tax bill that may take up much of the energies of these trade committees (which are also the tax committees) in the coming months. They apparently hope to convince Trump that tax reform can achieve the same anti-offshoring objectives as would punitive tariffs, and do so more efficiently and comprehensively, but the deals that they strike could prove to be equally protectionist. The plan that Speaker Ryan and Chairman Brady advocate would switch taxation to a territorial system, and while it would allow businesses to deduct the cost of domestically produced inputs it would not offer a comparable deduction for foreign-produced inputs. [4]

Over the longer term, the question is whether Trump will have to fight for the nomination in 2020. Much may depend on when the bears come out of hibernation and chase away the bull market. The data in Table 1 show the close association between recessions and reelection, with contractions hurting presidents not just by undercutting public support but by emboldening challengers in their own parties. Just ask Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and George H.W. Bush, each of whom faced the “double whammy” of a recent downturn and a tough nomination fight. The five incumbents who won reelection from 1972 to 2012 averaged 38.6 months of breathing space between Election Day and the most recent recession, versus just 14.7 months for these three single-termers.

Wall Street and the economic talking heads seem to have fixed on the idea that the economy will be kept afloat for the foreseeable future by increased spending and decreased taxes, but that could prove to be another triumph of hope over experience. By historical standards, we are nearly three years overdue for a new contraction. The current expansion began in June, 2009, and if it were held to the post-war average (58.4 months) it would have ended in April, 2014. Even if it were to match the lengthiest expansion in the post-war era, which persisted for a full decade (i.e., March, 1991-March, 2001), the next drop would come in mid-2019.[5] Unless one assumes that the current expansion will beat all records, it is a safe bet that a recession will arrive sometime in the next four years. But one may only guess whether it will land in time to roil the 2018 congressional elections, or will instead wait to make its mischief in 2020.

Will Congressional Democrats Be Stubborn Mules or Opportunistic Jackasses?

Republicans are the most important players for Trump to woo over the next two years, but Democrats may still have key roles when it comes to trade — especially if a sizeable number of Republicans manage to recover their voice on this issue. Democrats will be especially powerful in the Senate, where they hold seven more seats than the rock-bottom minimum of 41 that a minority party needs to obstruct legislation. They may play an even greater role in the latter half of Trump’s term. There is strong reason to expect that Democrats will retake control of the House in 2018, and whatever positions they adopt in their campaigns may set the tone of domestic U.S. trade politics not just for the 116th Congress but also the 2020 presidential election.

Early indications are that the Democrats in the Senate are not prepared to treat Trump quite as shabbily as the Republicans treated Obama. They have signaled sharp opposition to Trump on issues that matter to them, but they are prepared to deal with the White House when their interests and views intersect. Trade may well be one of those topics. Hillary Clinton’s loss was a repudiation of the party’s small and dwindling pro-trade wing, and will almost certainly strengthen the trade-skeptical wing led by senators Bernie Sanders (Vermont) and Elizabeth Warren (Massachusetts). That majority faction does not want to be seen cooperating with Trump in general, but on this one issue it may be prepared to make up for whatever votes that Trump loses to those Republicans who keep the faith with open markets.

It is not immediately apparent what specific aspects of Trump’s trade agenda may require congressional action in the first year. There is a strong likelihood that much of what he will do in 2017 will not require the assent of Congress, especially if he relies on existing presidential authorities to threaten or impose restrictions on imports. As for any new trade negotiations, their time horizon is typically measured in years rather than months. The rules of trade promotion authority (TPA) require that he first clear any new negotiations with the trade committees in Congress, but that is usually a low hurdle. Unless Trump manages to achieve a vast acceleration in the pace of bilateral trade negotiations, the results of new negotiations are not likely to be submitted to Congress until the latter half of his four-year term. The only notable exceptions to that rule might come if the proposed renegotiation of NAFTA is achieved relatively quickly, or if one or more of the TPP countries were to strike quick, bilateral deals using that pact as their basis for negotiation.

Major trade decisions in Congress might thus be postponed until 2018, multiplying the chances that they will become entangled once more in electoral politics. The current TPA grant is scheduled to expire on July 1, 2018. This means that any negotiations that Trump initiates will need to be concluded by that date,[6] unless he requests and receives a three-year extension of TPA. Under the terms of the TPA grant that Congress made in 2015, that extension will be automatically granted unless either house of Congress adopts an extension-disapproval resolution before the expiration. Past extensions have been granted with little opposition, but this time the deadline will come just four months before a critically important congressional election. What might otherwise be a routine approval of a procedural request from a Republican president to a Republican Congress might easily become a high-profile issue in the heat of that year’s campaigns. The stakes will be higher still if Trump manages to conclude any FTAs in time for a 2018 vote.

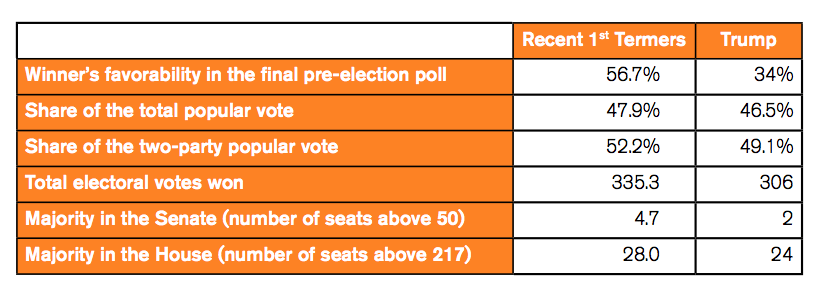

Table 2: Magnitude of Trump’s Win Compared to Recent First-Term Presidents

Recent 1st Termers = Average for the three most recent presidents (Clinton in 1992, Bush in 2000, and Obama in 2008).

Sources: Calculated from http://history.house.gov, http://www.senate.gov/history, Gallup.com, and press reports.

Democrats have good reason to look forward to electoral vindication in 2018. The raw numbers reported in Table 2 show just how precarious Trump’s position is by comparison with recent first-term presidents. He starts out with an historically low approval rating, he lost the popular vote, he captured a below-average share of the electoral vote, and his majorities in the two houses of Congress are relatively slender. Republicans came out of the 2016 election with a House majority of 24 seats, which places them precisely on the line of peril. A president’s party almost always loses seats in his first mid-term election, with an average loss of 24.1 seats in the seven elections that fit this description between 1970 and 2010. If Trump remains unpopular and/or the economy enters a recession, there is a distinct possibility that the Republicans will see losses on the same order of magnitude as the disastrous first mid-terms suffered by Clinton in 1994 (when Democrats lost House 54 seats) and Obama in 2010 (when they lost 62). Chances are lower that Democrats might regain control of the Senate in 2018, given the fact that they already hold 25 of the 33 seats that will be up for grabs that year, but they are also unlikely to dip below the crucial 41-seat level.

This is not to say that Democrats can be expected to take a firm stand against Trump when it comes to trade. Consider the fact that eight of the twelve Democratic members of the Senate Finance Committee face reelection in 2018, and half of them come from battleground states that Trump won. In addition to Florida’s Bill Nelson, these include potentially vulnerable senators from the Rust Belt states of Michigan (Debbie Stabenow), Ohio (Sherrod Brown), and Pennsylvania (Bob Casey). These senators can be expected to push back against Trump on many issues over the next two years, but both their voting records and their political predicaments suggest that they will be predisposed to back him on trade.

[1] See for example the March 2, 2016 “Open Letter on Donald Trump from GOP National Security Leaders” posted at http://warontherocks.com/2016/03/open-letter-on-donald-trump-from-gop-national-security-leaders/. Among the reasons that the signatories cited for their opposition to Trump was “His advocacy for aggressively waging trade wars [that are] a recipe for economic disaster in a globally connected world.”

[2] Senators face reelection every six years. Gubernatorial terms vary by state, and some are subject to term limits.

[3] It should be noted that in nominating this Republican, Trump has departed from a recent tradition by which the transportation portfolio has initially gone to a member of the opposition party. That was the practice for the first terms of presidents G.W. Bush and Obama, although each filled this position with members of their own parties in their second terms. Given the sharp increase that is expected in infrastructure spending in the coming years, this post has become a more valuable plum that Trump was evidently loath to waste on a symbolic appointment.

[4] It should be noted that the coming tax-reform bill might also have important implications for trade. See https://waysandmeans.house.gov/taxreform/.

[5] All data in this paragraph calculated from National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, available on-line at http://www.nber.org/cycles.html. One wrinkle worth considering is the lag between the start of a recession and its formal recognition. It took the NBER eight months to announce the contraction that began in 2001, for example, and fully a year to declare the one that started in 2007.

[6] The TPA rules further require that a president inform Congress ninety days before he signs a trade agreement. That allows a three-month period for final tweaks to the text, as well as for any efforts that Congress wants to make to force changes in its terms. This effectively means that any trade agreements negotiated under the current grant of authority will, unless the two-year extension is requested and granted, need to be substantially concluded by the end of March, 2018.

What Are the Options for U.S. Trading Partners?

What are U.S. trading partners to do? How should they respond to the potentially revolutionary changes in American priorities and style? Here the choice is not what kind of political animal to be, but what kind of trading system that they want. The directions in which Trump wants to take trade policy may accelerate unwelcome trends that have been underway for decades.

The most unfortunate thing about Trump’s attack on the WTO is that it contains at least a grain of truth (even if “disappointment” is a better descriptor than “disaster”). The members of the WTO have repeatedly proven that they are unwilling or unable to utilize that institution’s capacity to produce major multilateral agreements, preferring instead to pursue bilateral or regional deals while also overloading the docket of the WTO dispute-settlement system. Trump’s priorities suggest that both of these trends could soon be pushed to the breaking point. Numbers alone are not the issue. The WTO proved quite capable of handling the many cases that the United States and the European Union brought against one another in the immediate aftermath of the Uruguay Round, and the DSB could manage a large increase in complaints between the United States and China. The chances that the WTO may face an existential crisis will be much greater, however, if Trump were to take a series of WTO-illegal actions and then fail to abide by the inevitable rulings against the United States.

The same may be said for the dangers posed by Trump’s plans to negotiate bilateral trade agreements. The system has already been put under stress by the geometric increase in FTAs and other regional trade arrangements, even if WTO members are at pains to insist that these agreements are meant more to complement than to compete with multilateralism. Trump may not feel similarly constrained. The stresses on the system may become unbearable if he were to pursue bilateral agreements that blatantly depart from established WTO norms, or if he were to treat them as pure substitutes for multilateral agreements.

Will U.S. Trading Partners Opt to Chase Rabbits or Insist on Hunting Stags?

Jean Jacques Rousseau spoke to the current quandary of the trading system more than 250 years ago. In an early anticipation of modern game theory, the sage of Geneva described the essential problem that man faces whenever he tries to promote group cooperation over individual gain. Known today as the logic of the Stag Hunt, his allegory centered on a band of hunters who lived in a state of nature. Each man was capable of meeting his own minimum needs, but they had to work together if they wanted to bring down the big one:

If a deer was to be taken, every one saw that, in order to succeed, he must abide faithfully by his post: but if a hare happened to come within the reach of any one of them, it is not to be doubted that he pursued it without scruple, and, having seized his prey, cared very little, if by so doing he caused his companions to miss theirs.[1]

Our own deer (or stag) is the large and shared gains to be had if countries work together to negotiate an ambitious and balanced multilateral agreement. If they do so, they might collectively eat better than they would by pairing off to chase hares (i.e., FTAs and similarly discriminatory arrangements). Whereas FTAs were few and far between during the Uruguay Round negotiations, and some of them served as policy laboratories that complemented those negotiations, in the WTO era they have multiplied like rabbits. The only serious effort to fix this problem has come in the movement from bilateral and sub-regional agreements to the negotiation of mega-regionals. Initiatives such as the TPP and TTIP may still be rabbits, but at least they have the virtue of being really big rabbits. Even when one chooses to go after rodents of unusual size, however, the multilateral system may be undermined.

What prospects are there for multilateral negotiations under a Trump administration? Don’t look for him to go on the fool’s errand of resuscitating the Doha Round, which was already on life support well before the U.S. presidential election. All it lacks is a formal death certificate. He might hypothetically be persuaded to engage in multilateral negotiations on a case-by-case basis. There may be a renewed push in 2017 to conclude the environmental goods agreement, for example, and the European Union hopes to launch new negotiations to eliminate tariffs on trade in chemical products. The E.U.’s testing of the waters for a chemical agreement may be motivated precisely by a desire to divine the Trump team’s intentions. One consideration that may militate against these or any other multilateral initiatives, however, is Washington’s realization that any liberalization achieved on an MFN basis will benefit China. By negotiating outside of the WTO, the Trump administration can ensure that China is relegated to being the least-favored nation.

Now that Trump has confirmed his intention to pull out of the TPP, the other eleven parties must decide how to dispose of its remains. They might opt to treat this pact like the Treaty of Versailles (establishing the League of Nations) after the Senate amended it to death in 1919, or the Havana Charter (establishing the International Trade Organization) after the two chambers of Congress refused to approve it a generation later. The League of Nations tried to carry on without the United States, but only became a by-word for impotence. The world learned its lesson, and made no effort to put the International Trade Organization into effect without the United States. Even if the TPP countries try to approve a rump agreement, the more relevant question for those that do not already have FTAs with the United States is whether they ought to negotiate bilaterally with Washington. There are good reasons to expect that the Trump administration would hear any overtures from Japan with a sympathetic ear, but if market size is the deciding factor the auditions will be more challenging for Brunei and New Zealand than they are for Malaysia and Vietnam. There are still some grounds on which these smaller countries might make themselves appealing to the new U.S. negotiators, especially if they are willing to accommodate Trump in the development of a new FTA template, but they start out in a less advantageous position.

Trump has said that his administration will negotiate bilateral FTAs, but major questions remain as to when, with what content, and with whom. It would be a major departure from past practice for his administration to initiate new talks during its first two years in office. Only two of the twenty most significant U.S. trade negotiations over the past half-century were started at so early a point in a presidency, namely the Kennedy Round of GATT negotiations and the FTA with Central America in the G.W. Bush administration; the largest number were instead initiated in the second half of a president’s first term. In the Trump team, however, words like “long-established” and “unprecedented” seem to be taken more as challenges than as cautions.

The more significant question is what sort of content Trump would seek for his trade agreements. We have known for decades that FTAs are not just smaller versions of GATT or WTO agreements, as they may be more ambitious than the multilateral system in some ways while also less ambitious in others. An FTA might thus cover some issues that are not found in WTO agreements (e.g., competition policy and labor rights), and go beyond WTO commitments on established topics (e.g., services and intellectual property rights), but these agreements offer a very poor means of setting disciplines on agricultural production subsidies. We can expect that Trump’s people will want to develop a new template for these agreements so as to distinguish its own initiatives from what has come before, but just how far might that template stray from established patterns — and perhaps from WTO rules?

The possibilities could be imagined along a spectrum defined by two poles. At one extreme, the differences between Trump’s agreements and their predecessors might be largely cosmetic. Think of the difference between a fifty-story office tower that looks much like the other structures in the neighborhood, versus a nearby building that has fifty-one floors and sports the name “TRUMP” in giant, gold letters. One might similarly imagine an FTA that looks in most respects like earlier U.S. agreements, but includes a few additional provisions that Trump can call his own. Perhaps the most important distinction, at least to Trump, is that it would bear his brand. At the other extreme, imagine instead an agreement that is drawn up according to frankly mercantilist principles. There are any number of objectionable provisions that might be imagined, such as larger product or sectoral exceptions, more numerous safeguard or snap-back clauses, and perhaps even the types of trade-balancing provisions that some countries resorted to in the 1930s (which were tantamount to barter). The Carrier deal also suggests that a Trump administration might not simply negotiate an agreement and then leave it to the market, but may instead try to direct how traders and investors utilize its opportunities. Depending on the precise wording and execution of agreements, they might run counter to the spirit or even the letter of the system.

Which of these scenarios is more likely? The question brings us back to the core issue of whether Trump is prepared to undo that system as we know it, or whether he merely wishes to leverage the threat of doing so in order to secure the best deal. It is still too early to venture an opinion on that point with any real confidence.

Will the Trump Administration Aim its Bilateral Negotiations at Big Game or Black Swans?

Beyond when Trump might propose negotiations, and what he would seek in them, perhaps the most pressing question remains: With whom? The answer depends on the extent to which the Trump administration chooses to treat trade agreements as a means of expanding exports and jobs, and to what extent it will allow other concerns to dictate its choice of partners. The tenor of the campaign would suggest that the new team places commercial opportunities ahead of other, more political considerations, but some of Trump’s post-election moves imply that the latter will also guide him. While he can be expected principally to target the big game of major foreign markets, that would not prevent him from aiming at a few black swans as well.

There is yet another consideration that may shape these decisions, with Trump’s choice of negotiating partners being guided by the impact that FTAs might have on his own businesses. It could be difficult to distinguish this influence from the others, as it is possible for him to select partners in a way that hits more than one bird per stone. The actual abandonment of the TPP and the apparent demise of the TTIP,[2] for example, can each be seen in light of how they affect his own holdings. Canada and Mexico are the only TPP partner countries in which Trump currently has businesses,[3] and any leverage that he wants to exert over them can come via NAFTA. The sixteen businesses that he owns in these two countries are outnumbered and outweighed by the 51 that he has in six other non-TPP Asian countries; these include sixteen each in India and Indonesia, nine in China, and the rest divided among Azerbaijan, the Philippines, and Turkey. Similarly, the United Kingdom — or Scotland, to be more precise — is one of only two current E.U. member countries in which he has a business. The other is Ireland.[4] In short, Trump can walk away from both mega-regionals at virtually no cost to himself.

Trump’s FTA strategy may nonetheless take these moribund agreements as his point of departure, negotiating bilateral agreements with the largest parties to the TPP and TTIP. A bilateral FTA with the United Kingdom would be especially appealing, not just because it would cement his ties with the Brexit forces but because the U.K. import market is the fifth largest in the world. As for the remains of the trans-Pacific negotiations, the Japanese market is nearly as large (seventh in the world).[5] If the Trump administration wants to focus its bilateral negotiations on the big game, bagging these two would seem to offer the best prospects to stimulate exports and deliver jobs. The same cannot be said for the other TPP countries with which the United States does not yet have an FTA. New Zealand, for example, is a country that punches well above its weight in the conduct of multilateral and regional trade diplomacy, and kiwi diplomats could present themselves as willing partners in a new policy laboratory. That cannot change the fact, however, that in 2014 New Zealand held 61st place among world markets.

Beyond Japan and the United Kingdom, what other countries might attract U.S. interest? There are not very many big targets left. After Japan and the United Kingdom, most of the other large import markets (a) already have FTAs with the United States, (b) are E.U. members and hence legally barred from making bilateral deals (unless they follow the British cue), or (c) would seem by normal logic to be unattractive prospects. Chief among this latter group are China (the only country that seems absolutely off the table) and Hong Kong (where the market is already wide open). Switzerland is practically the only country left among the relatively large markets that would, if the typical calculations still matter, be considered a good prospect for FTA negotiations.

But what if the Trump administration decided to toss aside the rulebook and was prepared to negotiate with some unexpected partners? There are several countries that, in the manner of black swans, might present another opportunity for him to do the unexpected. The arguments in favor of five such countries and groups are variously commercial, political, and personal. They are listed below in roughly descending order of feasibility (i.e., the least startling comes first):

- Analysts of the Philippines are not sure whether it is best to characterize Duterte as the Filipino Trump or Trump as the American Duterte, but either way the resemblance and the mutual admiration are clear. The country’s import market is of only moderate size (32nd in the world), but it does host Trump businesses and has a sizeable (if somewhat apolitical) diaspora in the United States.

- The principal attraction of Taiwan is that it offers an opportunity to stick a thumb in China’s eye. It is also a large import market, even if the World Bank data still mask its size within the politically correct label of “Other Asia” (9th place). Trump’s organization has recently been exploring business opportunities in Taiwan, and some of his political operatives have ties to the island that date back decades.

- India has the world’s second largest population (after China), even if it remains a much smaller import market than its demography suggests (14th in the world). Its statesmen have no aversion to market intervention and managed trade, and thus may offer a useful foil if Trump wants to inaugurate a wholly new (and potentially WTO-illegal) FTA template. It may also be significant that Trump has substantial business interests in India, and strongly courted the votes and campaign contributions of Indian-Americans.

- The MERCOSUR countries of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay would be an admittedly surprising choice, both because of their demonstrable disinterest in extra-regional negotiations and their internal disputes (its members are barely on speaking terms), but they do form a large, emerging market. Moreover, Trump has businesses in all but Paraguay. If the group as a whole were not interested, Uruguay might arguably be an attractive stand-alone partner whose smallness in U.S. trade is offset by the Trump investments that it hosts.

- Russia is perhaps the blackest of all the swans, and negotiating such an agreement would admittedly be a very heavy lift — especially when Congress is prepared to chaperone the Putin-Trump bromance. Proposing such talks would nonetheless be precisely the sort of shock in which Trump seems to delight. It would not be likely to happen, however, unless as part of some broader effort to establish a truly new relationship between Moscow and Washington.

Each of these possibilities remains purely speculative, and come as much from peering into the blue sky as they do from real clues. We will get more substantial indications in the weeks to come as Trump fills out his cabinet (including the new U.S. Trade Representative), these nominees get grilled in the Senate, and the new government unveils its priorities. In a few more months we will know much more about what kind of law will be ruling the trade jungle over the next four years.

[1] A Discourse on a Subject Proposed by the Academy of Dijon: What Is the Origin of Inequality Among Men, and Is It Authorised by Natural Law? (1754), available on-line at http://www.constitution.org/jjr/ineq.htm.

[2] While Trump said nothing about the TTIP in the campaign, it is reasonable to assume that this mega-regional is just as kaput as the TPP. The transatlantic negotiations were already foundering, and efforts to redirect a troubled set of talks will be less attractive to him than proposing an altogether new initiative (e.g., an FTA with a Brexited United Kingdom).

[3] It is worth noting that after Canada and Mexico, the only other current FTA partners of the United States that have ties to Trump are the Dominican Republic, Israel, and Panama.

[4] All data in this paragraph come from the financial disclosure form that Trump filed on May 16, 2016 with the Federal Election Commission. It is available online at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2838696-Trump-2016-Financial-Disclosure.html.

[5] Based on the World Bank’s World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) data for 2014 at http://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/WLD/Year/LTST/TradeFlow/Export/Partner/by-country/Show/XPRT-TRD-VL;XPRT-PRTNR-SHR;/Sort/Export%20(US$%20Thousand).