What the 2018 (and 2020) Elections Mean for U.S. Trade Policy

Published By: Craig VanGrasstek

Subjects: North-America

Summary

The 2018 congressional elections put Democrats back in control of the House of Representatives, and thus returned divided government to Washington, but the meaning of these results for U.S. trade policy remain enigmatic. On the one hand, effective trade policymaking requires either unified government or a sense of comity between the branches. With neither of those conditions now prevailing, the prospects are high for gridlock over the next two years. On the other hand, trade is the one issue where Trump is more closely aligned with the Democrats than he is with the traditionalists in his own party. This suggests that there may be room for cooperation in the 116th Congress (2019-2020), but those prospects are further complicated by struggles within both parties. We may now be witnessing their realignment on trade, even if it takes at least one more electoral cycle to sort out the switches. Republicans must decide in 2020 whether to renominate the first truly protectionist president in nearly a century. Trade could be a key issue in a contested nomination fight, and even if Trump prevailed he might still be weakened by the challenge. If Trump were to win reelection, and to bring a new bunch of economic nationalists into Congress, his party’s protectionist retreat may pass the point of no return. The 2020 race could also be an important turning point for the Democrats. It is possible that a bold candidate might pull a “reverse Trump” by defying the party’s trade-skeptical orthodoxy and ─ if that candidate were to win ─ restore U.S. leadership in trading system. That potential may be more aspirational than realistic.

Introduction

American voters showed some buyer’s remorse when on November 6, 2018 they elected members to the 116th Congress (2019-2020), delivering at least a partial rebuke to Donald Trump by returning the House of Representatives to the Democrats. The electorate’s next choice will come on November 3, 2020, when it will decide whether the Trump experiment merits four more years. In so doing, they may also determine the trajectory of the international trading system for decades to come.

This note takes stock of what the 2018 congressional elections may tell us about the evolving trade policy posture of the United States, with particular attention to the struggles over this issue within and between the two political parties. The chief focus here is on the longer term and the big picture, rather than the specific issues that are expected to arise in the 116th Congress. Some of these issues are undeniably important, such as ratification of the revised agreement with Canada and Mexico; approval of the new plans to negotiate with Japan, the European Union, and the United Kingdom; and conduct of the trade war with China. For our present purposes, however, the larger questions concern not the precise initiatives the administration may pursue with specific partners, but how the internal bargaining over those initiatives ─ and many more to follow ─ is shaped by the larger trends in domestic political economy.

This analysis builds upon an earlier forecast of what we might expect from a Trump presidency.[1] That previous note rhetorically asked whether Trump’s actions in office would be as provocative and destructive as his campaign rhetoric had promised, and whether the congressional Republican majority would be principled or docile. The record thus far has been disheartening on both counts, with Trump having wreaked great damage while congressional Republicans did little to restrain his worst instincts. This note also draws upon my forthcoming book Trade and American Leadership: The Paradoxes of Power and Wealth from Alexander Hamilton to Donald Trump,[2] in which I chronicle the process by which the United States first advanced ─ but has lately retreated ─ from a guiding role in the trading system. Starting from the premise that foreign economic policy begins and ends at home, that book shows how the U.S. conduct of economic statecraft depends critically upon the domestic diplomacy of trade.

The evidence reviewed below show how both parties are in a state of flux, and that there are contrary currents in both of them. The most obvious conflict is in the Republican Party, where Trump’s efforts to revive protectionism have gone unchallenged. That may change as the 2020 campaign draws nearer, especially if — as expected — one or more of Trump’s critics contest the party’s presidential nomination. Perhaps the most intriguing development concerns the rising level of pro-trade sentiment in the base of the Democratic Party. Those views have yet to percolate up to the party’s congressional hierarchy, and they also collide with the increasingly trade-skeptical views in such established Democratic constituencies as unions and consumer organizations. It is nevertheless possible that the time is coming for a new Democratic leader to take a page from Trump, in form if not in substance, and go against the party’s orthodoxy in a campaign for the presidential nomination.

[1] See Craig VanGrasstek, “What Will Happen to U.S. Trade Policy When Trump Runs the Zoo?” ECIPE Occasional Paper 03/2016 at ecipe.org/publications/what-will-happen-to-u-s-trade-policy-when-trump-runs-the-zoo/.

[2] Cambridge University Press will publish this book (cited here as Trade and American Leadership) in January, 2019.

The View from 35,000 Feet

For better or for worse, the United States matters more to the world than vice versa. That has been true ever since American policymakers took over the role once played by their British cousins, acting as the first among equals in the creation and maintenance of an open trading system. The U.S. commitment to that system has, in turn, relied upon American presidents’ ability to win support from a rival branch of government that is often controlled by the opposition party. Managing the domestic diplomacy of trade has never been easy, but the last dozen presidents succeeded more often than they failed. The point could become moot if Trumpism outlasts Trump, as presidents cannot succeed in leading the international trading system when they do not even try.

While it is admittedly a cliché to call any given election “one of the most important of our lifetimes,” that description is not out of place for what just happened in 2018 and what will follow in 2020. Taken together, they will determine whether the shocker that came in 2016 was a mere fluke, or instead marked a true inflection point in the relationship between the United States and the rest of the world. That is especially true in the field of trade policy, where the American electorate chose its first unapologetically protectionist president since 1928. We do not yet know if the radically anachronistic policies that Donald Trump champions will prove an aberration, to be corrected by the next presidential election, or if his withdrawal of U.S. leadership will become self-perpetuating.

The answer may depend on choices that the two political parties make over the next two years. We may now be witnessing a realignment in the partisan politics of trade, starting with the president’s attempt to drag the party that he hijacked back to its protectionist, nativist, and isolationist roots. Republicans had been rock-ribbed protectionists from the 1860s through the 1960s, followed by a transitional period; since the mid-1980s they have appeared just as firmly attached to open markets. The 2018 results may accelerate the reversal of that position that Trump began in 2016. Republicans suffered heavy losses in “swing” districts where the president’s policies and demeanor alienated moderates and independents, and also saw the voluntary retirement of some officeholders who could no longer stomach the leader of their party. So while the Republican caucus in the House of Representatives will be smaller in the 116th Congress than it was in the 115th (2017-2018), the average survivor may be more loyal to Trump and less devoted to free trade. If Trump were to win reelection, and perhaps recapture control of the House by bringing in a new crop of likeminded candidates, the conversion of that party’s position on trade could pass the point of no return.

If the Republicans can no longer be counted upon as the party of open markets, the future of U.S. leadership in the trading system will depend upon the Democrats. That party remains divided between its globalist presidents and its localist legislators, and even that distinction is endangered. While every Democratic chief executive from Franklin D. Roosevelt through Barack Obama favored an open trading system, there is no guarantee that the party’s next standard-bearer will share that objective. There is a serious danger that the next Democratic presidential candidate will be more tempted to compete with Trump on his own, protectionist turf than to promote a U.S. reengagement with the world. As for the Democratic caucus in Congress, over the past generation its pro-trade wing has shrunk to the size of a vestigial limb. There is as yet only scattered evidence to suggest that the congressional Democrats’ instinct to oppose Trump will make them rethink their position on this issue. To the contrary, here the party’s senior leadership may be willing collaborators.

The issue is as much generational as it is ideological. The leaders in both parties have begun to exhibit a disturbing resemblance to the enfeebled ex-revolutionaries that we used to see presiding over May Day celebrations in the Soviet Union, all of whom had only dim memories of their 70th birthday parties. Donald Trump had already reached that milestone before Inauguration Day, making him the oldest man ever to assume that office;[1] if he served a full, second term, he would leave office at 78. He is nevertheless among the younger members of the governing gerontocracy. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (Republican-Kentucky) is 76 years old, and Representative Nancy Pelosi (Democrat-California) ─ the once and (probably) future Speaker of the House ─ is 78. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (Democrat-New York) is the only one in this bunch who is not yet a septuagenarian, but not by much; he turned 69 just after the election. As discussed below, there are signs in both parties that their younger voters and officeholders may challenge the positions espoused by these all-too-elder statesmen. One manifestation of this trend is the emergence of a largely younger and more ideological, pro-market faction in the Republican caucus. The situation in the Democratic Party is more complicated. Pro-trade sentiment is rising in the party’s base, and the formation of the New Democrat Coalition is also an encouraging sign, but the most energetic group among Democrats today is a progressive movement that is more interested in how wealth is distributed than in how it is created.

[1] Ronald Reagan held the previous record, being eight months younger than Trump on his own inauguration.

The Election Results and the Reorganization of Congress

The 2018 elections brought Democrats back into control of the House of Representatives, where they will hold at least 234 seats[1] when the new Congress convenes in January, 2019. That is comfortably above the 218 that they needed in order to retake control of the 435-seat lower chamber. The Democrats’ gains were in line with established patterns of American politics: Voters typically treat midterm elections as a referendum on the party that controls the White House, and the president’s critics are usually more motivated than his supporters. Over the course of the last century, the party in power has gained seats in only three such elections (i.e., 1934, 1998, and 2002); the average loss in the 1946-2014 midterms was 25.7 House seats.[2] The Democrats significantly exceeded that average, but their 39-seat advance still fell short of the waves that brought Republicans to a majority in 1994 (54 seats) and 2010 (63). They also under-performed their own 48-seat records of 1958 and 1974.

Balanced against the Democratic pick-ups in the House was the loss of two seats in the Senate, where they and their allies[3] will now hold 47 of the 100 seats. That split decision was not so unusual, with voters having reached similarly divided verdicts in ten elections since 1926. The Democrats’ chances in the Senate were circumscribed by the fact that they had to defend many more seats (26) in this election than did Republicans (9), and 10 of their incumbents ran in states that Trump won in 2016. The Republican majority in the upper chamber is important, but Democrats still have six more seats than the 41 that a minority needs to act as an effective check on the majority.[4]

The Frequency and Importance of Divided Government

This restoration of divided government means that, like most other presidents in recent generations, Donald Trump must now contend with a legislative branch in which his political rivals have the capacity to thwart his plans. This is especially true for effective trade policymaking, which has come to depend on two scarce elements. One is the declining propensity of the electorate to choose unified government, and the other is the equally diminishing propensity of elected officials to engage in the give-and-take that divided government requires. Overcoming partisan difficulties was already hard enough when the political center of gravity in the Democratic Party had shifted into the trade-skeptical camp, and the pro-trade Republicans enjoyed the luxury of unified government only once in a not-so-blue moon. Even those verities disappeared when the supposed party of free trade elected a protectionist president.

It is increasingly rare for both houses of Congress to be controlled by the president’s party. While government was divided in just seven of the 34 congresses (21%) from 1901 through 1968, the share will now have grown to 19 of the 26 congresses (73%) from 1969 through 2020. Jimmy Carter was the last president to enjoy unified government for the entirety of his mandate, and he served just a single term (1977-1980). Every one of his successors has had to deal with a legislative branch in which the opposition controlled either or both chambers for anywhere from two to eight years.

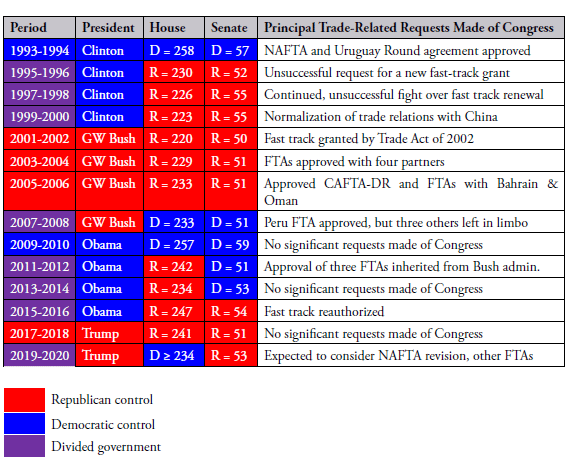

As can be seen from the summary in Table 1, each of Trump’s three most immediate predecessors had to manage the challenge of divided government for part of their tenure. The contrasts were especially sharp in the Clinton and Bush administrations, with both presidents finding it much harder to deal with Congress when the opposition party held a majority in both houses. The principal difference is that Clinton enjoyed the luxury of unified government for just two of his eight years, while Bush had that same advantage for six years. The result was that Clinton had only a short window for major achievements, while Bush’s string of successes lasted three times longer. Both men managed to get a few things done during periods of divided government — Clinton won congressional approval for the normalization of trade relations with China, and Bush secured passage of one FTA — but they were also dealt several defeats by the opposition party.

The contrast between unified and divided government was not so stark under Barack Obama simply because he chose not to deal with trade issues during the only two years that his party controlled Congress. His principal trade accomplishments in the remaining six years were to win approval for the agreements that he inherited from his predecessor, and then to tee up two mega-regional negotiations that his successor was supposed to complete. Obama also secured the new grant of fast-track authority (also known as trade promotion authority) that would be needed to facilitate the later congressional approval of these agreements; that was a rare instance in which congressional Republicans were willing to work with him. Those plans ultimately went awry when Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) before Congress could even take it up for consideration, and suspended negotiations over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

Table 1: Trade Policy Initiatives under Divided and Unified Government, 1993-2020

House and Senate Data Show the Number of Seats Held by the Majority Party

Note that the House and Senate margins reflect the election results, and do not take into account any subsequent vacancies or replacements brought about by resignations, deaths, special elections, or appointments.

Sources: Seat numbers for 1993-2018 from https://history.house.gov/Institution/Party-Divisions/Party-Divisions/ and https://www.senate.gov/history/partydiv.htm; 2019-2020 from https://www.cnn.com/election/2018/results.

The return of divided government comes just when Trump most needs the cooperation of Congress. As significant as trade issues have been in the first two years of Trump’s tenure, virtually everything that the White House did between Inauguration Day in 2017 and Election Day in 2018 rested on the inherent powers of the office or on authorities that past congresses granted to the president. That was equally true for the steps the president took to undo the work of his predecessors, such as the TPP/TTIP debacles and renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and for the administration’s revival of long-dormant trade laws that allow the president to restrict imports on various grounds. Trade will play a much greater role in the 116th Congress, now that the administration has moved into a new phase in which its more significant plans require explicit congressional approval. The new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement cannot replace NAFTA unless Congress enacts the implementing legislation for the new pact, and the administration needs the acquiescence of the congressional trade committees to move ahead on new negotiations with Japan, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. Past experience shows that Congress is not likely to respond to these requests with a simple, yes-or-no answer, but will instead take full advantage of the opportunity to wring concessions from the administration on matters of importance to legislators.[5] That may involve bargaining on issues that run directly counter to the priorities of the Trump administration and its congressional allies, and the resulting confrontation could — as has often happens — result in legislative gridlock. The precise terms of any proposed bargains will depend greatly on the leadership of Congress and its committees.

Congressional Leadership and the Trade Committees

The Democratic takeover means that the leadership of the House will now change, the Democrats will have a majority on every committee and subcommittee, and will also chair them all. Current Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (Republican-Wisconsin), who decided not to seek reelection, will likely be replaced by a pair of Californians. The Republican caucus has already chosen Kevin McCarthy (Republican-California) to replace Ryan in his role as Republican leader. For his role as speaker, Ryan will quite probably return the gavel to Nancy Pelosi. She is opposed by a group of insurgent Democrats, but (as of this writing) they have yet to name a candidate to challenge her. In contrast to Ryan, an orthodox Republican who favors small government at home and open markets abroad, Pelosi represents the trade-skeptical majority in her party. She proved that when she last held the speakership, leading her caucus in its 2007 opposition to the FTA with Colombia.

Major changes are in store for the Ways and Means Committee, which has principal control over trade issues in the House of Representatives. Republicans held 24 of the committee’s 40 seats in the 115th Congress, and Democrats the remaining 16; it is expected that the ratios will be precisely flipped in the 116th (i.e., 24 Democrats and 16 Republicans). Deliberations will be affected not only by the many new Democratic members who will now be appointed to this high-prestige committee,[6] but also by the departure of veteran Republicans; fully half of the Republicans who served on this committee in the 115th Congress are now gone. The committee’s chairmanship will pass from Representative Kevin Brady (Republican-Texas), who has chaired it since 2015, to Representative Richard Neal (Democrat-Massachusetts). While Brady is firmly planted in the traditional, pro-trade wing of the Republican Party, Neal is a moderate who has voted against some trade agreements (e.g., NAFTA) and for others (e.g., the U.S.-Peru FTA).

There will be less change in the Senate leadership. Senators McConnell and Schumer will continue to lead the Republican majority and the Democratic minority, respectively. Similarly, the Senate Finance Committee — which has jurisdiction over trade — will undergo fewer changes than its House counterpart. While Chairman Orrin Hatch (Republican-Utah) opted not to seek reelection, Chairman-designate Charles Grassley (Republican-Iowa) headed this same committee in past decades. Grassley’s return means that the Senate will carry on the long-standing tradition of selecting Finance chairmen from agricultural states — a fact that has often influenced the priorities of U.S. trade negotiators. The committee will also need to select replacements for three veteran members of the committee who were defeated for reelection, including one Republican (Dean Heller of Nevada) and two Democrats (Claire McCaskill of Missouri and Bill Nelson of Florida).

Beyond engaging the Republicans over their conflicting priorities in domestic and foreign policy, the newly emboldened House Democrats will also devote considerable attention to investigations of malfeasance in the Trump administration. There is every reason to expect them to be aggressive in using their newfound subpoena powers. They may even be prepared to pursue impeachment proceedings against the president, depending on what is revealed in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s long-awaited report on possible collusion with Russia and the subsequent efforts to obstruct justice. But while Democrats may oppose the administration on numerous fronts, it remains unclear just how they will deal with the White House on trade.

[1] There still remains one outcome to be determined, with the Democratic candidate holding a slim lead in the latest count.

[2] Calculated from Brookings Institution, Vital Statistics on Congress Table 2.4 at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/vitalstats_ch2_full.xlsx.

[3] Senators Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Angus King of Maine identify as independents, but both of them caucus with the Democrats for purposes of majorities and committee assignments.

[4] Senate rules allow even a single senator to freeze proceedings by taking the floor and refusing to yield, or just threatening such a maneuver. A “hold” can be defeated by invoking cloture, which requires 60 votes. Any minority of 41 or more senators can thus wield great authority by threatening to bring all business to a halt.

[5] For detailed examples of how the executive and legislative branches bargain with one another over the approval of trade agreements, see chapters 4 and 9 of Trade and American Leadership.

[6] The prestige of the Ways and Means Committee is not due primarily to its control over trade, but to two other, higher-profile issues over which it has jurisdiction (i.e., taxes and Social Security).

The Shifting Partisan Positions on Trade

The most important questions regarding the domestic politics of U.S. trade policy concern the permanence of the Trump revolution. Does the current Republican lurch towards protectionism represent a temporary accommodation to the preferences of one man and his base, or does it mark the start of a new pattern in the partisan politics of trade? And will it be complemented — either in the short or long terms — by a countervailing adjustment in the positions espoused by Democratic legislators? Trump won the Republican nomination, and then the presidency, by recognizing and exploiting the economic loss, social alienation, and political disenfranchisement of those left behind by the relentless process of creative destruction. No matter when or on what terms his presidency comes to an end, contenders in both parties will covet the support of his anti-globalist base. There is a serious risk that this could set off a race to the bottom in both parties, with candidates for Congress and the presidency competing over who may appeal to the least common denominator in the trade-skeptical quarters of the electorate.

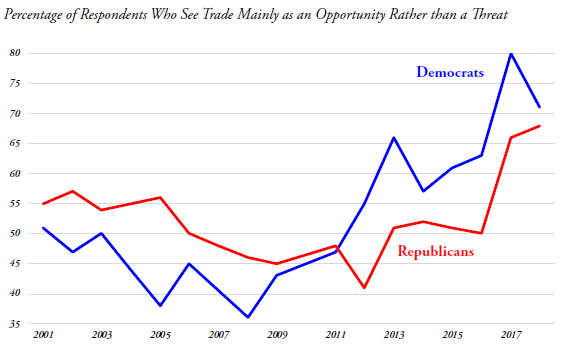

While Donald Trump’s decision to stake out a protectionist position distinguished him from all other contenders for the Republican nomination in 2016, he did not conjure this position out of the ether. The data illustrated in Figure 1 instead suggest that he benefited, whether through genius-level intuition or dumb luck, from a trend that the professional politicians either missed or did not believe: The bases of the two parties began changing places on trade during the Obama administration, the most immediate effect being the rightward gravitation of protectionist sentiment. Republican voters were still more favorably disposed toward trade than were Democrats prior to 2011, but the partisan positions flipped over the next several years. And while a bare majority of Republican voters still saw trade more as an opportunity than a threat in 2016, that left a very substantial minority whose anger could be leveraged.

Figure 1: Popular Support for Trade by Party, 2001-2018

Percentage of Respondents Who See Trade Mainly as an Opportunity Rather than a Threat

Text of Question: “What do you think foreign trade means for America? Do you see foreign trade more as an opportunity for economic growth through increased U.S. exports or a threat to the economy from foreign imports?”

Note: No data are available for 2004, 2007, and 2010. Values for those years interpolated from the prior and following years.

Source: Gallup poll at http://news.gallup.com/topic/trade.aspx.

The evolving partisan conflicts over this issue are further complicated by a fundamental change in the nature of trade politics. As recently as the 1980s, trade policy was largely a fight over tariffs, quotas, and other instruments of protection; those traditional instruments have since been displaced in trade debates by disputes over such hot-button topics as labor rights, the environment, and access to medicine. While the old struggles over narrowly commercial issues could typically be settled through some difference-splitting bargain, the newest issues that are now tied to trade involve not just producers with interests, but also consumers and even socially conscious spectators. Groups that are motivated by larger political causes rather than their own economic interests are not easily placated by the usual instruments of cooptation. These topics also widen the partisan divide. Social issues relate more directly to the ideological divisions between Democrats and Republicans, and their incorporation into trade politics has transformed the word “compromised” from something that pragmatic legislators frequently have done to something that their purist colleagues do not want to be.[1]

The Shifting Positions of Democratic Party Constituencies

These shifts in the meaning of trade policy are partly the consequence of new issues taken up in trade negotiations and disputes, and also reflect the changing perspectives of core constituencies in the Democratic Party. These include some groups that are principally motivated by economic objectives, as well as others that see trade issues through entirely different lenses.

Chief among these Democratic constituencies are the labor unions, whose leaders (if not all of their members) have been four-square behind this party since the 1930s. In those days the labor movement was also very pro-trade, due primarily to the dominance of unions that represented highly competitive industries. The subsequent decline of American competitiveness in the steel and automotive sectors had a predictable effect on the positions that labor leaders and their Democratic allies took on trade. The associated unions’ enthusiasm for open markets began to wane in the 1960s, and their first response was to demand that any further liberalization be accompanied by special adjustment-assistance programs for displaced workers. Their views turned decidedly more negative when the U.S. trade deficit became chronic in the 1970s, and they advocated outright protectionism. Since the 1980s, the unions have pursued a more nuanced stance that is based upon enlightened self-interest, insisting that developing countries’ access to the U.S. market be conditioned upon their adherence to labor rights. That demand marked the start of a new phase in the domestic politics of trade, leading the way for other groups that saw trade not just in economic but in social and political terms.

A similar process has affected other liberal groups that see trade primarily for the ancillary benefits that it may bestow — or the costs that it may impose — on relations between countries. From the 1930s through the 1960s, organizations such as the Foreign Policy Association, the World Peace Foundation, and a wide array of religious groups supported free trade because they saw it as an antidote to war. It is perhaps inevitable that free trade could not survive as a faith-based initiative, however, as only a few strands of the Judeo-Christian tradition are comfortable with the notion that greed might be good. By the late 1980s, some of these same groups or their intellectual and political heirs took a far more negative view of open markets. They generally based their concerns not on the impact of trade on relations between countries, but instead on how it affects the poor within countries.

Of all these migrations from the pro-trade to the trade-skeptical camp, the strangest case is that of consumer organizations. From the Progressive era of the 1890s through the social movements of the 1960s and early 1970s, consumer advocates treated import barriers as just one more trick by which plutocrats seize rents for themselves while denying affordable, quality goods to consumers. The intellectual tradition that associates protection with trusts and trust funds attenuated over time, and consumer organizations gradually came to see open markets more as a threat than a goal. Today they place a higher priority on product safety, environmentalism, and related issues than they do on prices. Their principal concern is not with trade liberalization per se, but with the prospect that the dispute-settlement provisions of trade agreements might lead to rulings against cherished domestic laws and regulations. Instead of viewing the competitive firm as the consumer’s tacit ally, and the tax-hungry state as their common enemy, they typically portray corporate greed as the central problem. If not restrained by the regulatory bodies of an interventionist state, they fear, corporations would cut corners at the expense of consumers, workers, and the environment.

The end result of these evolving positions among unions, the religious community, and consumer organizations is a switch in the externalities that are associated with trade liberalization. What was once seen as an indirect means of promoting peace and social justice has come to be associated with corporate power and income inequality. It is uncertain just how much liberal groups contributed to the success of pro-trade initiatives in past generations, but there is no doubt that the objections they now raise help to shape a policymaking environment that is more hostile to new trade agreements. The progressive wing of the Democratic Party places especially strong emphasis on these issues, and their advocacy is made all the more important by the declining strength of the unions.[2]

The center of gravity among most Democratic officeholders today is thus more trade-skeptical than pro-trade, but there are some preliminary signs that yet another switch in partisan polarity could be underway. The polling data reported above imply a gradual shift in partisan sentiment, and other surveys also hint at a generational effect. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, for example, has found that support for trade agreements such as NAFTA and the TPP is notably higher among the American public’s younger cohorts (Generation X and the Millennials) than it is among their elders (the Silent Generation and the Baby Boomers), and that the Democrats in each of these younger groups are more pro-trade than Republicans of the same age.[3] There are also signs that the pro-trade wing among congressional Democrats may get a second wind. The members of the New Democrat Coalition are “committed to pro-economic growth, pro-innovation, and fiscally responsible policies,” and represented over one-third of the caucus in the 115th Congress.[4] It will be useful to see how many new members join this coalition in the 116th Congress, and whether they can begin to counterbalance the trade-skeptical views in the party’s congressional leadership and its progressive circles.

For the time being, it is safe to suppose that the Trump administration will find that its trade dealings with the Democrats will hinge on more complex matters than simply favoring protection over free trade. The same Democrats who may share concerns with Trump over the trade deficit may part company with him when it comes to other issues associated with trade, such as labor rights, environmental protection, and other regulatory protections. Even those who are inclined to approve his NAFTA revisions may balk at giving a simple “yes” to his plans, demanding that he pay a price for their acquiescence. And like other presidents before him, Trump may find it supremely difficult to find some formula on the “trade and” issues that can win Democratic votes without simultaneously losing some from Republicans.

The Shifting Positions of Republican Party Constituencies

The Republican Party position on trade had long appeared both more favorable and more uniform than that of the Democrats, but that too could be changing. Its position is now divided along two distinct fissures. The subtlest distinction is between the traditional, pro-business Republicans and a newer group that is more ideological and pro-market. The other split divides the pro-Trump candidates who crave the approval of the leader and (even more) the support of his followers, and the more principled Republicans whose fealty to family values and the rule of law weighs more heavily than a win-at-all-costs mentality.[5] Some legislators have put themselves in the sometimes untenable position of professing both to be most pro-market and most pro-Trump. The potential conflicts between these two assertions was exemplified by the administration’s repeated failures to repeal and replace the health law known colloquially as Obamacare; some of the same lawmakers who claim to be most closely tied to the president also stood against his proposed alternative, citing their preference for a more free-market solution.

The most pressing question for the trading system is how similar tensions may be resolved when Trump asks the Republican caucus to support his trade agenda. Some of his initiatives pose little risk of intra-party disunity, such as the proposed negotiations with major trading partners, but others are more troubling both to traditional, business Republicans and to market purists. Trump’s support for tariffs and other interventionist measures has thus far evaded close congressional scrutiny, largely because he has relied to date on authorities that do not require the acquiescence of the legislature. Confrontations are much more likely in the 116th Congress than they were in the 115th. When forced to choose between being a party of principle or a cult of personality, will Republicans place orthodoxy ahead of expediency?

The party’s divisions over trade were first sighted in the 2010 congressional elections, when the insurgent movement then known as the Tea Party helped them recapture control of Congress. Many of the voters and candidates who identified with this faction were even more trade-skeptical than Democrats, and took a dim view of the favors that the party had traditionally extended to its business cronies. To understand the distinction between the pro-market and pro-business factions, it is important to recognize that a true free-market philosophy envisions a small role for the government; the more traditional Republicans favor certain forms of government support to business. Some initiatives force uncomfortable choices: Efforts to promote exports may veer into subsidization, laws intended to combat other countries’ unfair trade practices may be exploited for protectionist purposes, and the process by which tariffs on specific imports are reduced or waived may promote corrupt bargains between lawmakers and favored constituents or contributors. A pragmatic free-trader can rationalize these bargains as small prices to pay for a more open market, but zealous opponents of government involvement in the economy take an entirely different view of a “pay to play” system in which the state still has significant means of intervening.

Ideological struggles in the Republican Party pose a problem for incumbents who otherwise enjoy a great deal of job security. Reelection rates usually exceed 90% in the House and 80% in the Senate. When an incumbent is denied a new term, the chances may now be nearly as high that this defeat came in the renomination process as it did in the general election. Of the nine Senate Republicans who failed to be reelected during 2010-2017, four had been denied renomination by their own party. The threat is somewhat lower for Republicans in the House, but even there nearly one-third (12 out of 37) incumbents who were denied reelection during this period could thank a fellow Republican for their involuntary retirement. At issue here is the transformation of the word “primary” from a noun to a verb. Ideologues in both parties can mount a challenge to the renomination of an incumbent who does not conform to their expectations, and even the threat of being primaried may make a risk-averse legislator reluctant to stand alone in the middle of the road.

The primaries wrought fewer changes for the Republican caucus in this latest election than did a process of self-imposed exile. Five congressional Republicans lost their primary elections in 2018, all of them in the House,[6] but this was less significant than a sharp spike in the number of House Republicans who avoided the challenge by taking themselves out of the running. No less than 34 of them chose not to seek reelection this time, almost precisely twice the average number of voluntary retirements by House Republicans during 1946-2016 (17.3 per cycle).[7] Some of these retirements came either because the veteran lawmaker anticipated massive Republican losses, or had grown tired of supporting a president who flouts well-established party positions. The resulting attrition among the Republicans had the effect of making the party’s congressional caucus more Trump-friendly, both by ushering out some of its more upright members while also bringing in a few new ones who feast more heartily on his dog’s breakfast of economic nationalism, racism, and militarism.

Trade Messages in the 2018 Campaigns

The actual content of the 2018 midterm election offers some insight into these shifts in party position. Trade issues had a far higher profile in these campaigns than they had at any time since the debates over NAFTA in 1992. In contrast to most recent election cycles, in which the typical candidate either had nothing to say about trade or dealt with this topic only as one more item in their larger economic message, many 2018 candidates made trade a prominent part of their pitch to the voters. That included several Republicans who struck a stance that was either more trade-skeptical, or more favorably disposed towards a trade war, than we might have expected in the pre-Trump era. This race also saw several Democrats stand up to Trump’s provocations.

Consider the case of the Trump administration’s tariffs on steel and aluminum, which is the most controversial trade issue thus far in this president’s term. Announced in March, 2018 under the national security provision of U.S. trade law (Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962), those tariffs promptly led to retaliation by major trading partners such as Canada, China, the European Union, and Japan. Over half of all Senate candidates in the 2018 elections took a position on this issue, often — but not always — lining up according to their relationship with the president. Twelve Republican candidates supported the administration’s position, while eight expressed opposition. The pattern was just the reverse among Democrats, of whom twelve opposed the restrictions and just six stated their support.

This partisan division is illustrated by three heartland races in which a Republican defeated an incumbent Democrat. Josh Hawley unseated Claire McCaskill in Missouri, even though McCaskill reminded voters that she had “spoken out against the Administration’s reckless tariffs, which are putting Missouri farmers, ranchers and manufacturers under enormous strain — and has fought to save Missouri jobs jeopardized by the trade war.”[8] Hawley had some misgivings over other countries’ retaliatory measures, but he gave the White House the benefit of the doubt. “If this is about getting better deals for our farmers and opening up markets and beginning to fight back in this trade war, I’m for that,” Hawley said.[9] Much the same thing happened in North Dakota, where incumbent Senator Heidi Heitkamp lost to Republican challenger Kevin Cramer. Heitkamp ran a campaign commercial that attacked the policy and her opponent’s indifference towards its impact on the state’s farmers,[10] but she still lost. The same pattern was repeated in Indiana, where Republican challenger Mike Braun defeated Joe Donnelly; Braun favored the Section 232 policy, and Donnelly opposed it.[11] We can expect newly elected Republican senators Braun, Hawley, and Cramer to give Trump more support in his conduct of the trade war than had the three Democrats who opposed him. (These results might also deflate the expectation of some U.S. trade partners who hoped that targeted retaliatory measures would provoke opposition in the farm belt and force the White House to reassess its strategy.)

The national exit poll data do not show this issue offering a strong advantage for either party. Pollsters asked 18,778 voters in House races what effect the Trump trade policies had on the local economy. Those who said that they hurt (29%) slightly outnumbered those who thought they helped (25%), and each group voted accordingly: 89% of the critics voted for the Democratic candidate, and 91% of those favoring the policy voted for the Republican. Disentangling cause from effect, however, may be quite tricky. While some respondents may have based their votes largely on this issue, many others may have trimmed their answers to fit decisions they already made about Trump and the contending candidates. It is also notable that the single largest bloc of respondents (37%) said that the Trump trade policies had neither helped nor hurt the local economy.[12]

These observations are more anecdotal than rigorous, and offer only intimations of what the candidates will actually do when they are in office. The acid test will come in 2020, when the Democratic presidential nominee must decide whether to confront Trump on this issue or to out-do him in bellicosity. It would be a positive sign for the United States, and the trading system as a whole, if at least one of the contenders in a very large field of Democratic hopefuls were to pull a “reverse Trump” and defy the current Democratic orthodoxy on trade. It would be better still if that hypothetical candidate were to win both the nomination and the general election. The prospects for such a development will remain purely speculative, however, unless and until this ideal candidate emerges.

[1] For a fuller examination of the widening scope of issues in trade policy, and how this affects the domestic U.S. politics of trade policymaking, see Chapter 5 of Trade and American Leadership.

[2] The share of American workers represented by unions rose from 5% in 1933 to 22% in 1945, plateaued for a time, and then fell from 23% in 1983 to 12% in 2015. Calculated from U.S. Department of Commerce, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (1975), page 178, and Bureau of Labor Statistics data at https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet.

[3] Chicago Council on Global Affairs, “The Clash of Generations? Intergenerational Change and American Foreign Policy Views” (June, 2018), posted at https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/publication/clash-generations-intergenerational-change-and-american-foreign-policy-views.

[4] See https://newdemocratcoalition-himes.house.gov/.

[5] I examine the evolving Republican politics of trade, as well as relations between Donald Trump and his party leaders, at greater length in Chapter 6 of Trade and American Leadership.

[6] The full “casualty list” for the 115th Congress is available at https://www.opensecrets.org/members-of-congress/outgoing-members-list?cycle=2018.

[7] Calculated from Brookings Institution, op.cit, Table 2.9.

[8] McCaskill campaign website at https://clairemccaskill.com/issue/standing-rural-missouri-agriculture/.

[9] Associated Press, “Missouri’s McCaskill, Hawley Clash on Trump’s Trade War” (August 10, 2018), at https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/missouri/articles/2018-08-10/missouris-mccaskill-hawley-clash-on-trumps-trade-war.

[10] The ad is available online at https://youtu.be/DT7ARv9W7U0.

[11] Chris Sikich and Kaitlin Lange, “Indiana Senate race: The real differences between Braun, Donnelly,” Indianapolis Star at https://www.indystar.com/story/news/politics/2018/11/04/indiana-senate-race-2018-joe-donnelly-mike-braun-real-differences-between-candidates/1832727002/.

[12] Exit poll data at https://edition.cnn.com/election/2018/exit-polls/national-results.

What Do the 2018 Results Tell Us about 2020?

Political analysts are well-advised to exercise caution when prognosticating Donald Trump’s future. For them, his election in 2016 was something akin to the conundrum that physicists admit to when trying to explain how bumblebees fly: The feat seems impossible, even in the face of irrefutable proof. With so many of the 2016 forecasters being forced to eat crow, they tend now to hedge their predictions for 2020. While that humility is merited and commendable, it should not prevent us from gauging the probability of Trump’s reelection.

The Limited Predictive Value of Midterms and Polls

Much of the post-election analysis has asked what the 2016 results may portend for 2020, often seeing dark clouds ahead for Trump. For example, one Washington Post columnist observed that Democrats won more votes than Republicans in four key states that voted for Trump in 2016 (i.e., Iowa, Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania). If the votes that Democrats garnered in House races nationally were translated into Electoral College terms, their candidate would win 290 of the available 538 votes (i.e., 20 more than the 270 needed to take the White House).[1]

History cautions against treating the results of midterm elections as a leading indicator of voters’ intentions in the next presidential race. Consider the “red waves” of 1994 and 2010, when the electorate returned Republicans to control of the House with net gains of 54 and 63 seats, respectively. Those record-breaking results did not signal the demise of the Democrats who then held the White House, as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama each won reelection in the next cycle. The general pattern instead offers yet another illustration of the public’s collective preference for divided government: Voters usually follow the election of a president from one party by rewarding the opposition in the next midterm, and will typically respond to a midterm switch in the partisan control of Congress by reelecting the other party’s incumbent.

We should be similarly cautious regarding the predictive value of presidential approval ratings two years before a reelection campaign. It is true that Donald Trump currently suffers from a low approval rating, with one outfit calculating his average at 42.4%, but this is not much below the averages that Ronald Reagan (43.1%), Bill Clinton (44.3%), or Barack Obama (46.0%) achieved at the same point in their presidencies. Each of them went on to win second terms. And if further contrary evidence were needed, two other presidents who lost their reelection campaigns seemed to be doing much better than Trump at this stage; Jimmy Carter had an approval rating of 51.9%, and George H.W. Bush’s was 52.7%.[2] With polls offering such little insight into future developments, we ought not to make too much of a recent one in which a mere 36% of the respondents said that Trump deserves a second term.[3] A lot could happen between now and the next election.

The Importance of Intra-Party Fights and Recessions

If we cannot base our expectations for 2020 on either the midterm results or current approval ratings, what other oracles might we consult? The best predictor is the state of relations between the president and his own party, followed by expectations for the economy as a whole. Trump has reason for concern on both counts.

As reviewed in an earlier analysis,[4] the internal struggles of the Republican Party could well determine the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. Incumbent presidents won most of the thirteen races during 1948-2012 in which they sought a new term; the sole exceptions were those who faced credible challengers for their own party’s nominations. Two of the presidents who suffered that fate felt obliged to pull out of the nomination race, and both times the other party’s nominee went on to win the general election. Three other incumbents beat back strong challenges in their own parties, but were so weakened in that first phase of the campaign that they lost in November. The first pattern spelled defeat for Harry Truman in 1952 and Lyndon Johnson in 1968; the second doomed Gerald Ford in 1976, Jimmy Carter in 1980, and George H.W. Bush in 1992. Either way, there is an absolute and negative association between a credible renomination challenge and victory.

There are any number of Republican grandees who might challenge Trump in 2020. Governor John Kasich of Ohio has been threatening just that since late 2016, and two of the three Republican senators who chose not to seek reelection in 2018 — Jeff Flake of Arizona and Bob Corker of Tennessee — may be similarly inclined. Other names frequently mentioned include former Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, who has just been elected to serve as senator from Utah, as well as Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska, businesspersons Carly Fiorina and Mark Cuban, and even former Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley. The field of potential challengers is so large that they run a serious risk of splitting the anti-Trump vote. Unless they consolidate behind a single candidate, the never-Trumpers could inadvertently ease his victory in the first stage of the campaign. Like Ford, Carter, and Bush, however, Trump would be well-advised not to assume that a contested nomination is just a speed-bump in the road to reelection.

Trump’s chances for a second term also depend on the state of the economy. History shows that it is especially important for an incumbent to avoid the stain of a recession: The five most recent incumbents who won reelection averaged 38.6 months of breathing space between Election Day and the preceding recession, but among the losers there were just 14.7 months separating the contest from the last downturn.[5] The 2018 congressional elections came in the 113th month of the current economic expansion, which began in June, 2009. It is already the second-longest expansion in more than a century and a half, and will break the record if it continues past June, 2019.[6] The Democratic gains in the midterm elections would almost certainly have been much greater if the current expansion ended sometime in the past two years, and Trump’s chances for reelection will be vastly reduced if the inevitable recession were to begin sometime in the next two years (and especially if it were to come in 2020). The prospects for such a downturn are far outside the scope of the present review, apart from observing that ─ from the admittedly narrow perspective of the trading system ─ there could be some didactic value in any downturn that was widely attributed to an ill-considered bout of protectionism in the United States. It is also worth noting that some bearish analysts now see a growing number of warning signs, even though this is by no means a consensus view.[7]

The future course of the current business cycle, and the next electoral cycle, may well decide whether Trump succeeds in definitively reversing the Republican Party’s posture on trade. That reversal is by no means inevitable. While one could imagine Donald Trump being seen in the long run as a second Ronald Reagan who manages to redirect the policies of his party, albeit in precisely the opposite direction, it is just as easy to imagine him becoming a second Richard Nixon who departs in disgrace and repudiation. That latter scenario would appear more likely in the event that his tenure were to end in a severe electoral drubbing in 2020, or be cut shorter still by impeachment, a forced resignation, or perhaps even ─ in the most extreme scenario ─ a first-ever use of the cabinet’s power of removal under the 25th Amendment of the Constitution. As traumatic as those latter outcomes could be for the American body politic, they could avoid an even grimmer outcome for the U.S. and global economies.

[1] Philip Bump, “What Tuesday tells us about the 2020 election” (November 8, 2018), at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2018/11/08/what-tuesday-tells-us-about-election.

[2] These average approval ratings are as calculated by Fivethirtyeight for each president’s 678th day in office, as posted at https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/.

[3] Monmouth University poll released on November 14, 2018 and posted at https://www.monmouth.edu/polling-institute/reports/monmouthpoll_us_111418/.

[4] “What Will Happen to U.S. Trade Policy When Trump Runs the Zoo?”, op cit., pages 7-9.

[6] The longest expansion in U.S. history lasted precisely one decade, beginning in March, 1991 and ending in March, 2001. See National Bureau of Economic Research, “US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions,” at https://www.nber.org/cycles.html.

[7] See for example Lucas Laursen, “What Are the Odds of a U.S. Recession by 2020?” posted at http://fortune.com/2018/11/16/larry-summers-recession-by-2020/. For a more bullish outlook, see the National Association for Business Economics survey results reported at https://nabe.com/NABE/Surveys/Outlook_Surveys/October_2018_Outlook_Survey_Summary.aspx.

What to Look for in the Coming Months and Years

This note has necessarily raised more questions than it can answer, given the fluidity of partisan positions on trade. Beyond laying out the key issues, and providing some preliminary evidence from the most recent elections, all we can do at this juncture is identify the indicators to look for in the near and medium terms.

One set of clues will come in both parties’ personnel choices. The 116th Congress is still being organized, and has yet to determine the precise sizes and membership of the trade committees in the House and Senate. It will be especially useful to see which House Democrats are named to the Ways and Means Committee, who will be the new Senate Republicans on the Finance Committee, and what their voting records and campaign pledges may tell us about their approaches to trade policy. We may also get some clues from the number of House freshmen who opt to join the New Democrat Coalition, and whether that faction makes trade a priority.

The more difficult test will come in how the two branches and the two parties deal with one another in the trade issues that are expected to arise in the 116th Congress. Chief among these will be enactment of the implementing legislation for the United States Mexico Canada Agreement, and approval of the administration’s negotiating plans for Japan, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. If Congress runs true to form, these will not be yes-or-no decisions, but will instead center on the price that legislators ─ especially Democrats ─ demand that the White House in exchange for their acquiescence. That bargaining may center on the same social issues that have complicated U.S. trade policymaking since the early 1990s, with Democrats and Republicans clashing over labor and environmental conditions, but the internal party debates may make it harder than ever to resolve these differences. It will also be instructive to see how hard lawmakers press for new restrictions on presidential authority to restrict imports, and whether there is any bipartisan consensus on the need for the legislative branch to reassert its control over the regulation of commerce.

Two other clouds that will hover over all these issues are the special counsel’s probe into collusion and obstruction, and the potential for a downturn in the markets. Either or both of these processes could spell trouble for the administration, emboldening not only Democrats but also those Republicans who oppose Trump. They could each play a role in determining whether the president faces a challenge to renomination by his own party, and what sort of candidate the Democrats choose for 2020.

Over the long term, the most important question is whether Trumpism will survive its founder. While we cannot know when or under what circumstances it will come to pass, sometime in the next six years the world will join Othello in bidding, “Farewell the neighing Steed, and the shrill Trump.”[1] No matter when or how it happens, it would be a mistake to assume that the departure of one man means the disappearance of an endemic problem. The economic challenges that contributed to his electoral victory will still be with us, and policymakers in the United States and the wider world will still need to deal with those underlying issues. Managing that problem will be easier, however, if in the future there is at least one party in the United States that is still devoted to international cooperation and an open market.

[1] Othello, Othello Act III, scene III.