Ambition on Unstable Foundations: The UK Trade Policy Readiness Assessment 2020

Published By: David Henig

Subjects: European Union UK Project

Summary

The UK’s road to an independent trade policy has reached a critical moment. Within the next six months Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) containing long term arrangements and rules could be finalised with the United States and / or European Union, who between them constitute around 65% of UK trade. Talks have also started with Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

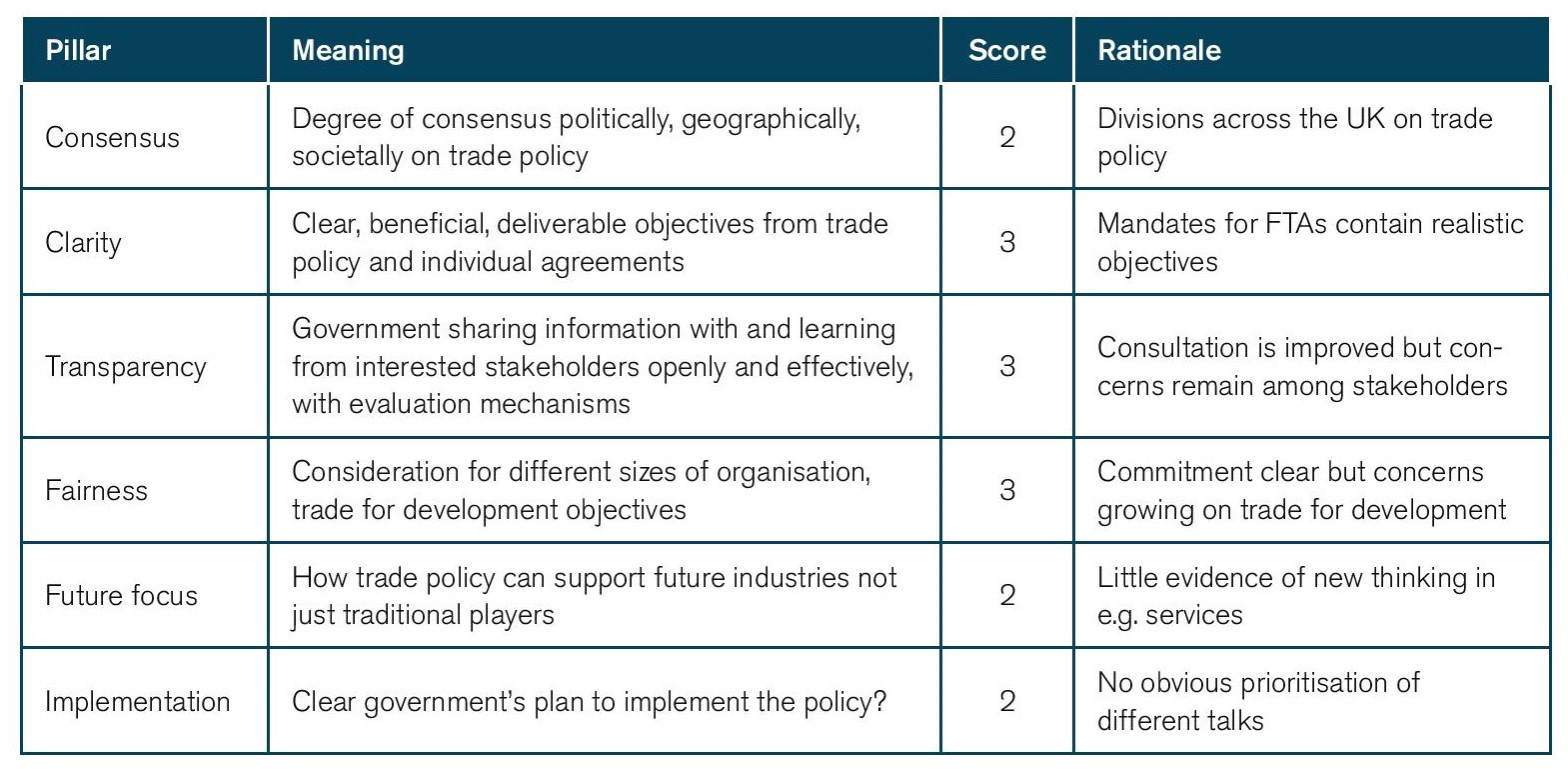

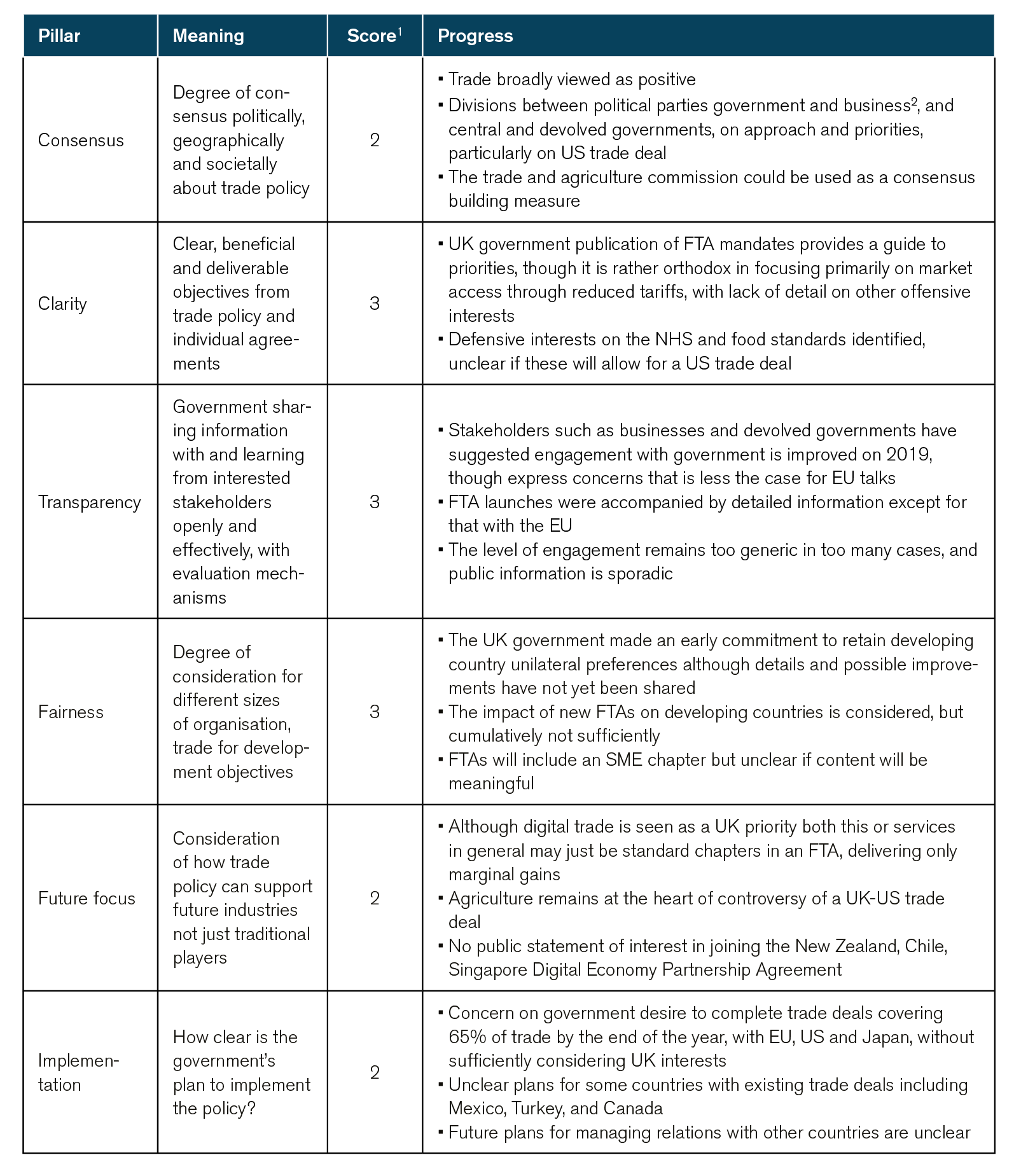

Our updated Trade Policy Readiness Assessment suggests that the UK government is not fully ready for this activity. On a scale where 1 suggests no work being undertaken, 3 a stable position to begin talks, and 5 successful delivery, we find problems in seeking consensus, expanding priorities beyond the traditional tariff reduction, and putting in place a realistic implementation plan.

The absence of consensus on policy detail, and which partners to prioritise, is the greatest concern. Despite leaving the EU in January 2020 political tensions continue, Brexit supporters encouraging a decisive break via a US agreement and potential trade conflict with the EU, and business warning of the damage of no trade deal with the EU. We previously predicted consensus would be particularly tested by US negotiations, and this came to pass with the government needing to establish a trade and agriculture commission due to concerns about US food imports.

We also see the sheer volume of activity, without obvious prioritisation, as an issue. As well as the talks for new FTAs, and potential accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), there remain existing trade partnerships where replicas have yet to be agreed, including with major trade partners such as Canada, Norway, and Turkey, and the split of agriculture quotas at the WTO not finalised. Yet there is some logic in starting a lot of activity and seeing what difficulties arise. The tough choices that have to be made in trade policy only start to become real when Ministers can see the clashes emerging (i.e. UK farmers versus a US trade deal). It also remains the case that while other countries want to see the UK-EU relationship determined, they are also interested in strengthening of their links with the UK.

A positive scenario for the UK at the end of the year would be foundation trade agreements in place with the EU and other European countries, a new agreement with Japan, and good progress in other talks, both bilaterally and at the WTO. If the EU deal safeguards UK manufacturing in particular, focus on finding new global opportunities for the UK’s strong services sectors could then increase. The negative scenario would be poor or restrictive agreements with the US and / or EU, or no deal with the EU creating a troubled relationship with our nearest trade partners affecting the economy and taking some time to recover.

This is what is at stake in the next few months. In January 2021 the UK may have a platform for a positive trade policy, or damage to be repaired. At this stage, the outcome is unpredictable.

The author gratefully acknowledges the able research assistance of Ingrid Fontes

Introduction

As a result of the 2016 referendum the UK left the EU on January 31 2020. The immediate trade impacts have been minimal due to a transition period lasting until the end of the year during which the UK is being treated as part of the EU for trade purposes, including in EU third country agreements. The UK government declined to seek an extension to this period.

January 1st2021 is likely to see the greatest change to trade relations in UK history, regardless of whether the current talks with the EU lead to a new Free Trade Agreement (FTA). From this date the EU will treat the UK as a third country for goods, services, and the movement of capital and people. The UK will have the freedom to diverge from EU regulations, and plans to leave many regulatory bodies such as EASA, the European Aviation Safety Agency[1]. The UK will no longer be a party to EU trade or other international agreements, though replicas have been agreed in many cases[2] (see Annex 1 for details of FTAs).

These changes will not apply in full to Northern Ireland, which will assume a hybrid existence between the UK and EU. For goods regulations and customs the province will predominantly follow EU rules, while nominally remaining part of the UK customs territory. For services it will remain fully part of the UK market. This arrangement will be in place for at least six years with a vote in the Northern Ireland Assembly in four years as to whether to continue.

A UK-EU FTA would help ease the impact of new trade barriers between the UK and EU, and indeed Great Britain and Northern Ireland, in particular those relating to customs checks and tariffs, and provide a basis for resolution of issues. There remains the possibility of such a deal having its own implementation period of some sort, as suggested by a number of commentators[3].

Through the Department for International Trade (DIT), the UK government has started talks for new FTAs with a number of other countries, most notably the USA, but also Australia, New Zealand, and Japan[4]. These talks come on top of the work to replicate existing EU FTAs and agree to schedules at the WTO.

It is a significant workload which we examine further in this report. We consider progress to date, update our assessment of the UK’s readiness for an independent trade policy, analyse how these efforts are viewed by potential trade partners, and consider what may constitute a future vision for UK trade policy, in the absence of an officially published one.

This report is a follow up to our 2018 study, Assessing UK Trade Policy readiness[5], and the update provided in 2019[6]. We use the same framework to examine UK progress, and understand the challenges that may be faced in the future.

[1] https://www.airportwatch.org.uk/2020/03/uk-due-to-leave-the-easa-european-aviation-safety-agency-transferring-all-responsibilities-to-over-loaded-caa/

[2] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/uk-trade-agreements-with-non-eu-countries

[3] https://www.cer.eu/in-the-press/business-needs-transition-period-eu

[4] Counted as a new negotiation even though there is an existing EU-Japan agreement

[5] https://ecipe.org/publications/assessing-uk-trade-policy-readiness/

[6] https://ecipe.org/blog/assessing-uk-trade-policy-progress/

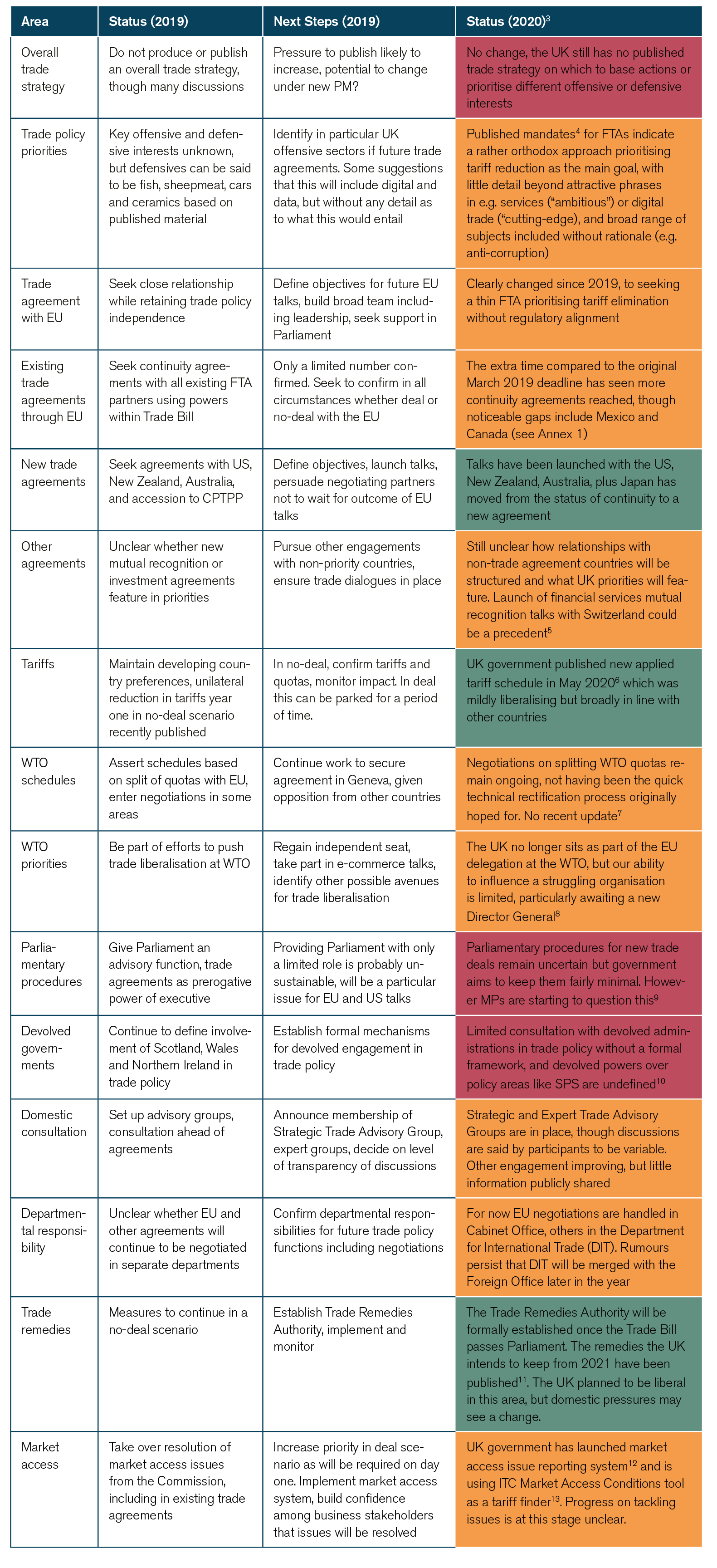

Progress to date

In March 2019 we identified the significant UK government workload on trade policy[1] going far beyond the negotiation of new and continuity Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), which has tended to dominate attention. Returning to this, we find continuing prioritisation of FTAs, such that negotiations have commenced without a clear trade strategy, formal mechanism for consulting Parliament, or clarity over how agreements might affect the powers of devolved assemblies in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. This is risky, in that unless greater attention is paid to such non-negotiating areas, we can expect the process of negotiations to be bogged down by domestic problems. Indeed, the establishment of a Trade and Agriculture Commission in June[2] was a sign of this, as farmers, environmental groups and others objected to the possibility of a US trade deal meaning changing UK food rules.

[1] https://ecipe.org/blog/the-next-stages-of-uk-trade-policy/

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/trade-and-agriculture-commission-membership-announced

[3] Assessed as Red (not on track), Amber (action proceeding, but concerns remain), Green (on track)

[4] For example, with the US at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/869592/UK_US_FTA_negotiations.pdf

[5] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/896778/Joint_Statement_between_Her_Majesty_s_Treasury_and_the_Federal_Department_of_Finance_on_negotiating_a_Mutual_Recognition_Agreement_on_financial_services.pdf

[6] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/uk-tariffs-from-1-january-2021

[7] The UK circulated a note to WTO members on departure from the WTO which can be found at https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news20_e/mark_03feb20_e.htm but provides little detail on the ongoing negotiation

[8] The UK nominated former Trade Secretary Liam Fox, though he is considered an outsider. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-53333616

[9] See for example https://www.conservativehome.com/platform/2020/06/jonathan-djanogly-parliament-should-be-able-to-scrutinise-new-trade-deals-properly-but-the-current-arrangements-are-simply-unfit-for-purpose.html

[10] https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2019/10/23/scotland-brexit-boris-johnson-food-environment/

[11] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/trade-remedies-transition-policy

[12] https://www.great.gov.uk/report-trade-barrier/

[13] https://www.macmap.org/

Trade Policy Readiness

In our 2018 paper, “Assessing UK Trade Policy Readiness”, we identified a set of criteria that could be used to judge the maturity of a country’s approach to trade policy and assessed the UK against these. At that time progress was unsurprisingly limited, and in the March 2019 update we identified only limited development. Since then the UK has left the EU, and there has been a change of Prime Minister and Secretary of State at the Department for International Trade. As above, the UK has started negotiations for new FTAs.

The activity is reflected in part in this year’s analysis. We see identifiable progress in terms of the UK’s ask from trade policy, although the published FTA mandates seem clearer in tariff reduction than other areas of policy, and consultation with stakeholders. However we remain concerned at the lack of consensus. In 2018 we wrote that “UK ministers, other politicians, and officials need to urgently recognise the need to build a national consensus and consult upon this – in particular if a new trade agreement with the US is to be considered they must consider whether a realistic mandate would pass parliament.”

- No clearly identifiable work being undertaken: The importance of this pillar has not been recognised, and we can see no sign of related work. The reality of the pillars is that this score should be unlikely;Discussion in progress: We can see from references made by ministers, officials, and others that work has started in this area, and they recognise the importance of it. There does not as yet seem to be any conclusions to this work however, or obvious gaps that mean it cannot be said to be stable;

- Stable position: There is a settled and defensible position in this pillar, it may not yet have been tested in negotiations, but it should be ready to be so;

- Operational: The government is negotiating on the basis of agreement in this pillar, this would be where most governments should aim to be;

- Delivering successfully: There are successful results of trade policy in this area, whether for the economy as a whole, specific business, or other interests.

[2] Few businesses are enthusiastic about a US trade deal, seeing this as likely to offer few new opportunities

The Global View of UK Trade Policy

Within the UK there has been little consideration about how its future trade policy will be seen by other countries, and what there has been tends to reflect UK differences. Supporters of Brexit point towards positive statements welcoming new opportunities while opponents have found plenty of articles suggesting the UK is suffering from delusions of grandeur. Our short survey of articles in other countries suggests that neither is the majority attitude. When examining different articles and published opinions we see three dominant themes.

On a positive note, there are hopes that Brexit will mean greater focus and / or new, mutually beneficial trade deals resulting from a less EU-dependent market. Chile is a good example, a long-standing UK friend and supporter of FTAs, happy to have secured its position[1]. China also saw opportunities for its economy and international standing, though this will probably have changed as a result of recent events in Hong Kong[2]. Aware of its leverage, Chinese specialists had thought a trade deal would make the UK more dependent on China, and so London might become more willing to speak up for Beijing’s interests in international forums.”[3]

The opposite of that positivity is doubt among some about their partnerships, thinking the UK’s relation with powerful countries, in particular the US, would be prioritized and augmented, leaving hardly any space for emerging economies. This has been a discussion in Brazil, with no implemented trade agreements with the UK. Oliver Stuenkel, coordinator of the MBA in international relations at Fundação Getulio Vargas discusses the impact of the FTA between the EU and Mercosur, which has not yet been ratified: “In theory, an agreement between the UK and Mercosur can be more advantageous for Brazil. It is another distribution of forces. The UK is much smaller than Mercosur. But this needs to be negotiated and can take a long time”[4]. In the new scenario of no hindrances from the common agricultural policy by leaving the EU, Brazilian exports would have the potential to grow. However, Brazil is a competitor with the US in some major exports, leading to doubts. “The great identification of the United Kingdom is with the United States, the favorite child”[5], states Simão Davi Silber, Professor of economics at the University of São Paulo.

Thirdly and seen probably most often is the vast feeling of uncertainty. Many analysts cannot reach an understanding over what a future relationship with the UK will look like before an agreement between the EU and the UK which they hope will emerge by the end of their “divorce”. Many countries believe they and their businesses could be affected by the absence of a UK-EU trade deal and are therefore hopeful that this will be avoided, even if this is not their most important current consideration.

The bigger theme of the future of Europe is also sometimes discussed with more insight than in the EU and UK. Taking the starting point that after 47 years as a member of the EU the UK’s marriage union has come to an end, it accepts that the EU will still be strong in international terms, “but will it have the dimension to rival global powers? Especially when it loses its strategic added value as a bridge between the United States and Europe? And precisely at the moment when Trump is doing everything to weaken the European Union and maintain a complacent UK?”[6]

Overall the brief survey suggests at least some positive news for the UK government. Potential trade partners are cautious but pragmatic, and while expecting EU and US talks to be the priority, ready to work with the UK government where there is a mutual interest.

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/54c17880-263f-11e9-8ce6-5db4543da632

[2] https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/hong-kong-and-britains-china-reset/

[3] Barber, Tony. “Waiting for the Golden Age of Brexit Trade Deals” Financial Times, 3 Mar. 2020, www.ft.com/content/6cfea2a0-5d53-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4.

[4] Frabasile 31 Jan 2020, Daniela, and 31 Jan 2020 – 18h41 Atualizado em 01 Fev 2020 – 10h26. “Saiba Quais Serão Os Impactos Do Brexit Para o Brasil.” Época Negócios, 31 Jan. 2020.

[5] Ibid

[6] Teixeira, Nuno Severiano. “Lições Do ‘Brexit.’” PÚBLICO. Público, February 12, 2020.

Three visions for UK trade policy

In the absence of a published UK trade policy strategy, discussions on what it should achieve have been fragmented. From those that have taken place, in articles and conferences, we discern two distinct visions, reflecting UK Brexit discussions since 2016, with the version pursued by the government adopting elements of both but emphasising quick FTAs above all. We discuss these visions below:

- ‘Anglosphere’ – proposed by influential Brexit supporters;

- ‘Quick delivery’ – pursued by the government based on the Anglosphere model but with the possibility of EU deal;

- ‘Business pragmatic’ – prioritising the EU and emerging economies, usually discussed fairly quietly by businesses

The most important determinant of the future path is likely to be whether either a US or EU deal is agreed by the end of the year. If there is a US deal or no EU deal then the Anglosphere approach is likely to predominate. If the opposite is the case it would not be a surprise to see neighbourhood ties grow again. This makes the second half of 2020 a seminal point for the long-term future of the Brexit project, made more complex by an awareness among so many of the stakes.

General Principles

Before looking at the specific visions it is worth outlining some foundation principles sometimes taken for granted. In particular there is a core assumption that the UK will be relatively trade liberal. This can no longer be taken for granted as voices of protectionism have become more prevalent during the covid-19 pandemic, for example in arguing for reduced trade with China. Discussions on UK food standards could also take on a protectionist form though at present they seem more about regulatory sovereignty. The new tariffs announced in April 2020 were only mildly liberalising compared to the EU, and we can no longer be sure of future trade remedies positions. Nonetheless we still think that on balance the UK consensus supports free trade, though with limits.

There is also widespread support for seeking a base of FTAs similar to the network the EU has. While their benefits are often oversold in the UK debate, the need to be competitive with other countries would seem to make this a reasonable assumption.

The impact of trade on the balance of manufacturing and services in the economy is sometimes overlooked in the UK’s debate. In winning the 2019 election the Conservative Party took seats in parts of the country strong in manufacturing, such as the West Midlands, a traditional automotive manufacturing area, a region known as the Potteries for its ceramics manufacture, and parts of the north of England with diverse production. Although the UK is one of the strongest services exporters in the world it is assumed that any government will also want to maintain a diverse manufacturing sector.

A final working assumption is that the UK relationship with the EU will not be a very close one, such as entering a customs union or rejoining the European Free Trade Area[1], for the immediate future, given the painful debates between 2016 and 2019. There remains considerable support for taking part in some EU programmes, such as Erasmus and Horizon, and some EU-led regulatory bodies, and in these areas however we expect many discussions in the coming years.

Vision 1: The Anglosphere

The most commonly agreed element of future UK trade policy among Brexit campaign groups is for FTAs with english speaking countries deemed similar, such as Canada, New Zealand, and Australia[2]. Sometimes these are put together in a proposed CANZUK[3] grouping in which deep trade agreements would be accompanied by freedom of movement. However there has been little appetite among those governments for such deep agreements[4].

A US agreement is also a priority in this anglosphere vision[5], one that for many proponents would see the UK move away from EU regulations particularly in agricultural production and technical standards. There has been discussion of a regulatory alliance that would be able to take on what is regarded as an outdated EU view on regulation, probably centred on the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), possibly with the US rejoining. Any trade deal with the EU according to this vision would only really cover tariffs. Some proponents have even suggested starting a trade war with the EU[6].

Domestically this vision is sometimes linked with deregulatory proposals in areas such as labour and planning, particularly in freeports or free enterprise zones, broadly modelled on similar US schemes. Proposed UK tariffs wouldn’t however offer the tariff inversion opportunities that are a key part of the US freeport experience[7]. The UK government is still consulting on their reintroduction[8].

MPs aligned with this vision have also recently expressed concerns about UK dependence on China[9], and suggested some trade restrictions, though these concerns are more widely shared. The government is considering these issues, but as yet no decisions have been taken about whether the UK will become more protectionist towards China.

Vision 2: Quick Delivery / Modified Anglosphere – Implied Government vision

The anglosphere has been an important part of the UK government’s trade policy activities to date with new FTA negotiations starting with Australia, New Zealand, and the US. There also continues to be considerable interest in joining the CPTPP[10]. Yet the government has not yet followed the vision of joining in a regulatory alliance against the EU, judging from the limited negotiating objectives and attitudes towards EU talks.

Although UK-EU talks have been marked by public statements of dissatisfaction by both sides, and the UK government has said on several occasions that it would be happy to trade on WTO terms (known rather oddly in the UK as an Australian-style deal[11]), talks continue. The public statement made by car manufacturer Nissan, operator of an iconic plant in the north of England, that this would be unsustainable in the event of no-deal[12] may have focused government minds. Similarly a fierce campaign against US food standards including by a respected consumer organisation[13] and among Conservative MPs might have shown the risks of aligning too closely with the US against the EU.

The anglosphere vision is problematic in other ways, for example limited potential economic gains, an appearance of nostalgia for empire, and lack of diversity. This is partly addressed by negotiating a new FTA with Japan to replace that with the EU which the Japanese wouldn’t replicate, and potentially doing the same with Turkey if there is a UK-EU deal.

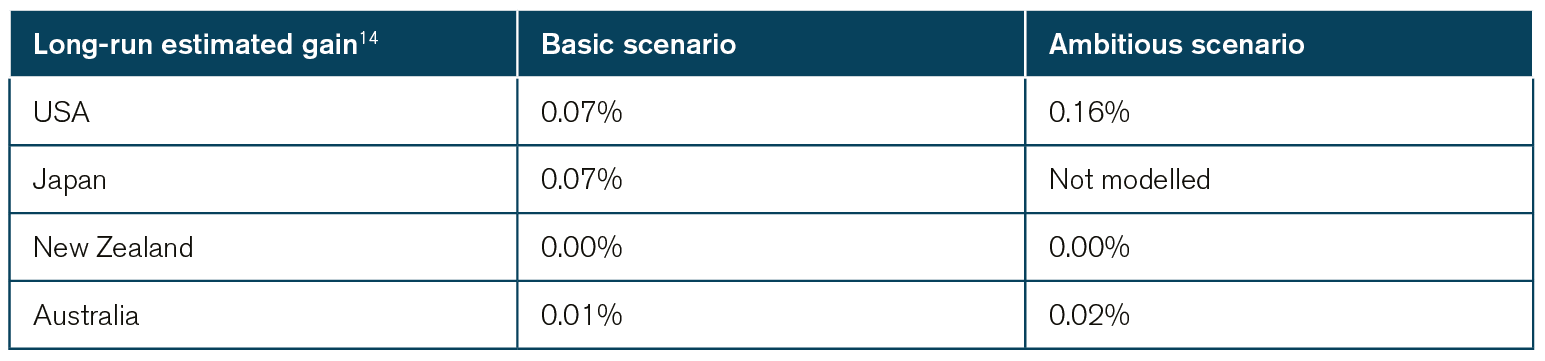

Overall, the impression given is that for the UK government the most important thing is the delivery of deals, regardless of economic potential or matching a vision. Potential gains from Australia and New Zealand FTAs are negligible, and while those from Japan and US trade deals are greater, these also rely on optimistic scenarios with regard to the removal of non-tariff barriers, even in the basic scenario.

The UK government might also hope that WTO talks progress in the form of the e-commerce plurilateral, but surprisingly has not so far expressed interest in the plurilaterals promoted by New Zealand, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) with Chile and Singapore, and the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS) with Costa Rica, Fiji, Iceland and Norway. It seems that completing Free Trade Agreements is their only real priority.

Vision 3 – Business Pragmatic

Over the last four years the relationship between business and the UK government has been poor. Successive governments have believed that business organisations wanted to reject the EU referendum result, while business thought their issues weren’t being taken seriously by government. In the polarised UK debate it was difficult to acknowledge there being some truth in what both were saying.

These relationships need to be rebuilt, with business providing detailed information, for the UK to have an effective trade policy. However it would also be worth listening afresh to business priorities as most are not interested in reopening Brexit debates. Rather they start with a recognition that with the gravity effect still being a major factor in trade the EU will remain a key market for the UK, not least in manufacturing where automotive and pharmaceutical exports are particularly dependent[15]. It makes sense to them for the UK to seek zero tariffs and continuing alignment with particular EU product regulations, since there is little to be gained from diverging from a global norm according to the Brussels Effect. This will also allow deeper relationships with other European trading partners closely linked with the EU such as Norway, Switzerland, and Turkey (Annex 3 shows the importance of these markets).

Businesses in general see little growth potential in the anglosphere, where trade relationships are already strong and FTAs unlikely to deliver significant liberalisation. Instead they are more interested in emerging markets, particularly where the UK has historically underperformed. Countries often mentioned include China, Indonesia, India, Turkey, Mexico and Brazil. It is perceived that there are particular barriers to areas of UK export strength in these markets, whether those are in terms of services, food and drink, or complex manufacturing products. A concern in not prioritising these markets initially is that it will be harder to make concessions in areas like agriculture in the future, having already conceded greater access to New Zealand, Australia and the US. Such attitudes interestingly match some thinking in the countries concerned, as suggested above.

One could even go further in this vision, and give serious consideration to launching an open access plurilateral on services initially with like-minded partners, following the New Zealand model of such agreements. As an alternative or addition plurilateral, accession to CPTPP is of interest to the business community, but not if this presents difficulties for EU trade in areas like food regulations and technical standards.

Given toxic Brexit debates most businesses are wary of putting forward this broad vision. However, it would be useful for them to seek a reset with the government that allows for a more open conversation, particularly around emerging economies.

[1] The UK was a founder member of EFTA – see https://www.efta.int/About-EFTA/EFTA-through-years-747

[2] See for example https://briefingsforbritain.co.uk/global-impacts-of-brexit-a-butterfly-effect/

[3] https://www.canzukinternational.com/

[4] https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/australia-rejects-visa-free-immigration-deal-with-uk/

[5] See for example https://globalvisionuk.com/agriculture-the-threats-to-global-britain/

[6] https://www.politeia.co.uk/wp-content/Politeia%20Documents/2020/08.04%20David%20Collins%20EU%20Playing%20Field/%27How%20to%20Level%20the%20EU%27s%20Playing%20Field%27%20-%20David%20Collins.pdf

[7] https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2019/02/27/any-free-port-in-a-storm-analysing-the-potential-of-free-zones-in-post-brexit-britain/

[8] https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/freeports-consultation

[9] https://henryjacksonsociety.org/publications/breaking-the-china-supply-chain-how-the-five-eyes-can-decouple-from-strategic-dependency/

[10] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-approach-to-joining-the-cptpp-trade-agreement/an-update-on-the-uks-position-on-accession-to-the-comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnership-cptpp

[11] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/boris-johnson-no-deal-brexit-eu-trade-security-a9589031.html

[12] https://www.autocar.co.uk/car-news/new-cars/nissan-sunderland-plant-%E2%80%9Cunsustainable%E2%80%9D-without-brexit-deal

[13] https://www.which.co.uk/news/2020/06/basic-food-standards-under-threat-from-us-trade-deal/

[14] Source, UK government modelling

[15] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/management/2018/11/09/can-brexit-defy-gravity-it-is-still-much-cheaper-to-trade-with-neighbouring-countries/

Conclusion / Next steps

Pursuing quick FTAs to fix trading rules covering 70% of trade, without knowing detailed priorities or overall vision, is not ideal. But at some stage the UK was going to have to start talks, and was always going to learn more by doing than by planning. In this we can see the sense of getting the process underway and seeing how it goes.

It is the timescales that make this aspiration most problematic. If a trade agreement cannot be reached between the UK and EU by the end of the year then the UK’s largest trading relationship will move from single market to WTO terms, with undoubted consequences. Trade relations with other European countries would also be affected. At the same time the government has been hoping to conclude agreements with at least the US and Japan, two of the three next largest trade partners, as well as potentially put up barriers to China, the remaining one.

Such a workload in just a few months looks optimistic bordering on reckless. Without a cross-UK consensus there is no agreement between the UK and Scotland governments even on who has what powers to set food standards. UK manufacturers are demanding zero tariffs and unchanged product regulations in an EU FTA to keep trade with their largest market. Farmers, environmentalists and animal welfare campaigners are demanding no reduction in food standards resulting from a UK-US FTA.

It will also have long consequences, in that to get deals concessions will have to be made that will rule out future deals. Provide more agricultural access to Australia and New Zealand and risk not being able to offer than to Brazil in return for greater services access.

Meanwhile the UK government must get ready for new barriers to trade between the UK and EU, and between Great Britain and Northern Ireland under the EU Withdrawal Agreement. Deal or no deal this will be the biggest change in trading relations the UK has seen.

The next six months are therefore crucial in defining Brexit, and the UK’s future trade policy. Consensus, detailed consideration of policy, and a more realistic implementation plan will have to follow. The foundations will be laid one way or another by the end of the year, whether that is in the direction of an EU and emerging markets approach, or an anglosphere and EU one.

This does lead to the thought that UK government decisions made this year should attempt to preserve policy space while protecting trade. That is a difficult balance to strike with trade partners who wish to close down our policy space in one way or other, especially when few in Westminster realised the trade-offs the UK would face so quickly. The government has forced itself to make decisions with significant economic consequence quickly. The outcome remains uncertain.

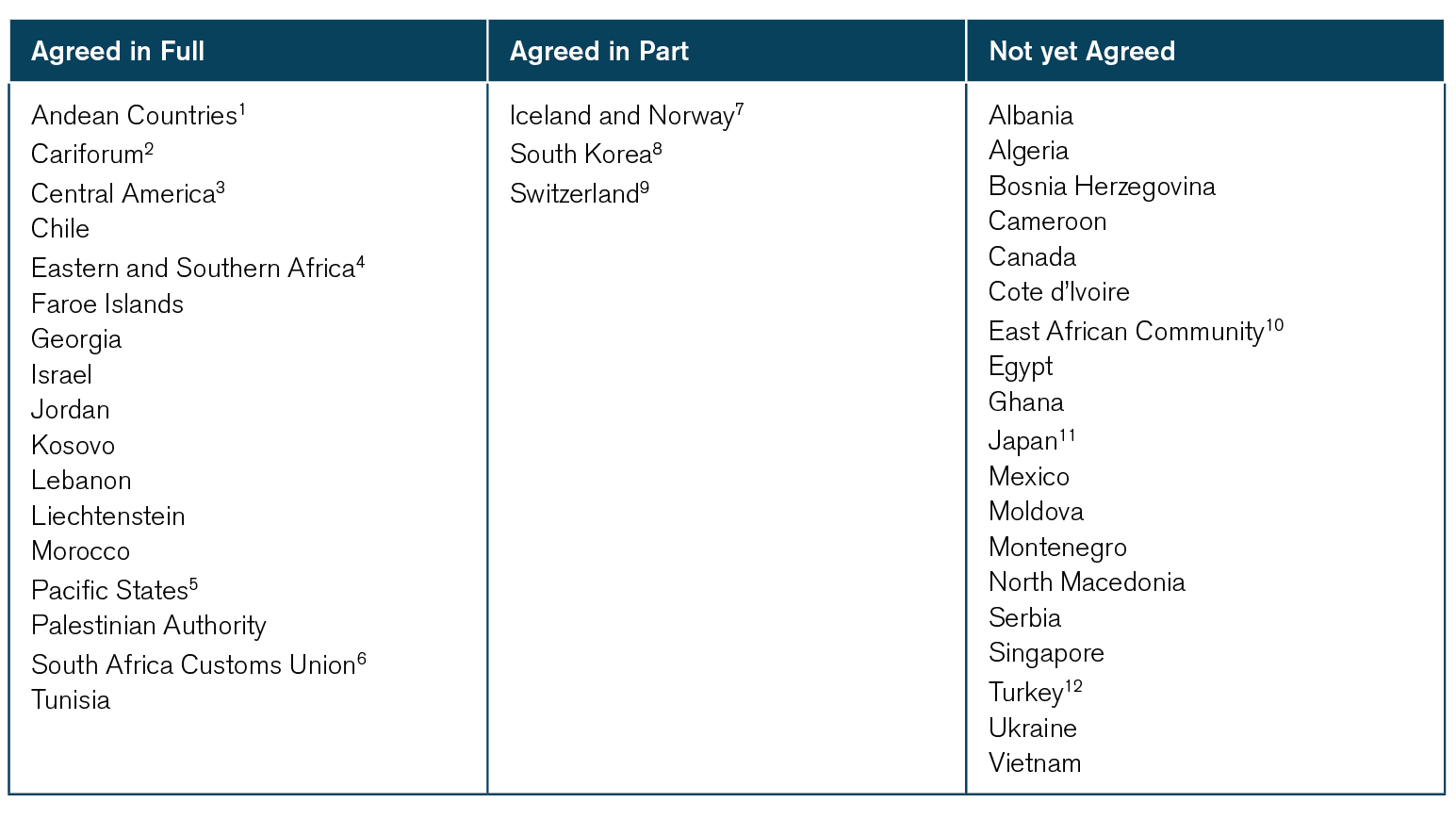

Annex 1: Progress on UK replication of EU Trade Agreements

As at July 1 2020.

[1] Peru, Colombia, Ecaudor

[2] Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, the Bahamas, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Christopher and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago (Suriname has approved in principle).

[3] Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama

[4] Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, Zimbabwe

[5] Fiji, Papua New Guinea

[6] Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique

[7] The agreement reached with Norway and Iceland covered mostly goods tariffs and would only have applied in the event of a Brexit with no Withdrawal Agreement, therefore must be renegotiated.

[8] South Korea agreed to recognise EU content as being from the UK for three years, but a renegotiation is due to start two years after entry into force

[9] A complex EU-Switzerland relationship is difficult to replicate, for a summary of the agreement see https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/2019/02/12/uk-and-swiss-trade-post-brexit/

[10] Never entered into force at EU level, as not ratified by EAC countries (see https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/eac/index_en.htm)

[11] Now considered to be part of the new trade agreements programme

[12] Due to the Turkey EU Customs Union would need to be considered alongside an EU deal

Annex 2: Opinions from outside the UK

1. Market Independence from the EU (Hopeful)

- “The UK doesn’t have one obvious sector that China sees as of compelling benefit to its own interests, so a deal is unlikely to be agreed quickly,” said Prof Mitter. “On the other hand, some Chinese specialists say a trade deal would make the UK more dependent on China, and so London might become more willing to speak up for Beijing’s interests in international forums.”[1]

- “Many U.S. and UK businesses and other groups see an FTA as an opportunity to enhance market access and align UK regulations more closely with those of the United States than of the EU. Other stakeholders oppose perceived efforts to weaken UK regulations. Some in UK civil society have voiced concerns about the implications of U.S. demands for greater access to the UK market, and potential changes to UK food safety regulations and prices for pharmaceutical drugs.”[2]

- “The global economy is undergoing great turbulence. Boris Johnson’s leadership of Britain could provide a unique opportunity to develop a real strategic partnership with India and develop synergies to address the evolving challenges. Development of India specific strategy by Britain on the lines on EU Strategy For India which was adopted in December 2018 could be a way out. Bilateral trade, Investment, Diaspora and security relationships could be the focus areas.”[3]

2. Questionable focus for future trade deals (Doubtful)

- “The UK is preparing to give itself a huge shot in the foot. The country has already suffered cuts in its prosperity in these years – the pound has lost 15% of its value, investment in the country has stagnated, many companies have moved their headquarters to the Netherlands or Luxembourg.”[4]

- “It will not be a simple divorce, but it would be much more complicated if the British had, for example, adopted the euro or integrated the Schengen Area, which abolished border controls in participating countries.”[5]

- “I think it’s pretty terrible. I think the Brits were lied to (and tricked) into voting for something they had no idea about and I think they got themselves into a mess because they were lied to about the whole idea that Brexit was supposed to be this wonderful thing — the whole idea about the payments to health care — none of them were true. It’s hard to tell (how it will play out).”[6]

- “The other side of this coin is the pursuit of deals with the US, China and other large non-European economies. Some, such as Japan, already have extensive trade and investment ties with the UK. But Japanese business executives sound gloomy. ‘Essentially, the United Kingdom’s departure [from the EU] is nothing positive for the Japanese companies doing business there, so the focus going forward is how much the negative impact is alleviated,’ Akio Mimura, chairman of the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said last month. Like others in Asia, executives in Tokyo say they cannot set precise goals for a UK trade deal until they know the details of London’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU.”[7]

- “U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has said that trade negotiations with the UK are a “priority” and will start as soon as the UK is in a position to negotiate, but he cautioned that the negotiations may take time. Whether the Administration ultimately takes a comprehensive approach to the negotiations, as with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA), or a more limited approach, as with the U.S.-Japan trade deal, remains to be seen.”[8]

3. Uncertainty

- “Brexit did not just divide the United Kingdom from the European Union, it also divided the United Kingdom itself. Among the youngest, most qualified and well paid, most urban and most cosmopolitan – winners of globalisation – who voted in favor of remaining in the Union. And the oldest, less educated, unemployed, more rural and more nationalist – losers of globalisation – who voted in favor of leaving.”[9]

- “The second is that of its position in the world. The United Kingdom leaves the European Union, in search of a regained sovereignty and a lost Empire. They now call it “Global Britain”. That is, it leaves Europe to become a global power. But will it have the dimension to rival global powers? Especially when it loses its strategic added value as a bridge between the United States and Europe? And precisely at the moment when Trump is doing everything to weaken the European Union and maintain a complacent UK? He does not want to be European, but it is unlikely to be global. And who knows, maybe they will go through an isolation that will not be as “splendid” as that of the Victorian era.”[10]

- “For the first time, a Member State is abandoning the European project, calling into question the principle of “ever closer union”. Does this mean the principle of the European Union’s breakdown? Or, on the contrary, did the difficulties of “Brexit” deter other states from following the same path? We do not know. But we know that Europe has never been an organic reality. It was always a political construction. It has no linguistic, cultural or religious unity and is composed of multiple nationalities. Which always oscillated between centrifugal and centripetal forces, between movements of fragmentation and unification. That there were moments of hegemony by feudal landlords or nation-states and moments of hegemony by Empires or European integration. And that is why unity has always been a political project, built on diversity.”[11]

- “The British have practically started the history of colonialism in the world and now thinking that they must decide for themselves on their foreign policy is short-sighted and shameful. I am convinced that these are not our interests – more austerity, more unemployment, more insecurity and more inequality. Cruelly, it is those who are already worse off who will be most affected.”[12]

- “I think that Brexit supporters should soon realize the enormity of what they have done. This referendum was carried out by Prime Minister David Cameron, who wanted to fight growing extremism inside and outside his party, especially with the UKIP [UK Independence Party] attacks. It was a wrong choice, with bad timing and poor discussion, which would have been better resolved if the topic had been smaller and more specific.”[13]

4. Future of Europe

- “Perhaps this is, at heart, the real lesson that Brexit leaves us all of us Europeans, British and continentals. Building European unity without respecting national diversity doesn’t work. But worse is when there is no unity, when national interests have no limits, rivalries between states triumph and nationalisms prevail. We know what that means, and it is certainly not peace, prosperity and democracy that European integration has bequeathed us.”[14]

- “With the UK leaving, foreign workers will not be able to enjoy many of the benefits to which they are entitled, including their right to work. However, if the United Kingdom wishes to continue to have access to the European Union’s economic zone, it will have to comply with many of the conditions of the European regulation, including those that protect workers. However, the risk of increasing xenophobia is undeniable from now on.”[15]

- “[Brexit] is the most profound blow ever inflicted on the beautiful history of European integration. With the loss of the United Kingdom, Europe loses its second largest economy, its second most populous country, its largest army, its oldest parliament, one of its two nuclear powers and one of its two permanent members of the Security Council. UN Security. It will be a less strong and more divided Europe, less able to set foot on the international stage for the USA, China or Russia.”[16]

- “The withdrawal from the United Kingdom forces not only the European Union, but all multilateral bodies to rethink their models. The EU is the most profound example of integration between nations and, despite being born under the sign of subsidiarity, with the proposal of respecting national particularities, has become a hyper-centralizing body. The transfer of power from national parliaments to Brussels and the way in which that power was used, often overriding sovereignties and imposing unnecessary and disproportionate standards, generated resentment that led to Brexit, but which does not end with it: just look at how Euroscepticism is gaining ground in other member countries as well, such as Italy, Hungary and Poland.”[17]

- “The U.K. government can only survive if it keeps the support of those voters who want the U.K. to leave the EU, so allowing the U.K. to stay in alignment with the EU or accepting the EU’s first offer would make them look weak.”[18]

- “It will have to decide within the next few months whether it wants unrestricted access to the internal market and compromise on rule divergence or stick to the latter and jeopardize access to the internal market and face the economic consequences.”[19]

[1] Barber, Tony. “Waiting for the Golden Age of Brexit Trade Deals.” Subscribe to Read | Financial Times, Financial Times, 3 Mar. 2020, www.ft.com/content/6cfea2a0-5d53-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4.

[2] Congressional Research Service. “Brexit and Outlook for U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement.” 12 Feb. 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11123.pdf.

[3] Manish Uprety and Jainendra Karn “The Fate of Indo-British Relations in The Aftermath of BREXIT” https://www.indepthnews.net/index.php/the-world/asia-pacific/3205-the-fate-of-indo-british-relations-in-the-aftermath-of-brexit

[4] PINTO, Hugo GUEDES, and por Lusa. “Opinião. Brexit? Que Brexit?” Wort.lu, January 29, 2020

[5] Campos, Marcio Antonio. “O Brexit Se Torna Realidade.” Gazeta do Povo. Gazeta do Povo, January 31, 2020.

[6] Holly Ellyatt, Jordan Malter. “’It’s Terrible – the Brits Were Lied to’: Americans Give Their Verdict on Brexit.” CNBC. CNBC, March 15, 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/14/what-do-americans-think-about-brexit.html.

[7] Barber, Tony. “Waiting for the Golden Age of Brexit Trade Deals.” Subscribe to Read | Financial Times, Financial Times, 3 Mar. 2020, www.ft.com/content/6cfea2a0-5d53-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4.

[8] Congressional Research Service. “Brexit and Outlook for U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement.” 12 Feb. 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11123.pdf

[9] Teixeira, Nuno Severiano. “Lições Do ‘Brexit.’” PÚBLICO. Público, February 12, 2020.

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Redação, Da. “Oxford: Três Opiniões Sobre o Brexit.” Exame. Exame, June 22, 2017.

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] PINTO, Hugo GUEDES, and por Lusa. “Opinião. Brexit? Que Brexit?” Wort.lu, January 29, 2020.

[17] Ibid

[18] El-Bar, Karim. “Experts Weigh in as Brexit Trade Talks Finally Kick Off.” Anadolu Ajansı, 3 Mar. 2020, www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/experts-weigh-in-as-brexit-trade-talks-finally-kick-off/1752643.

[19] Ibid

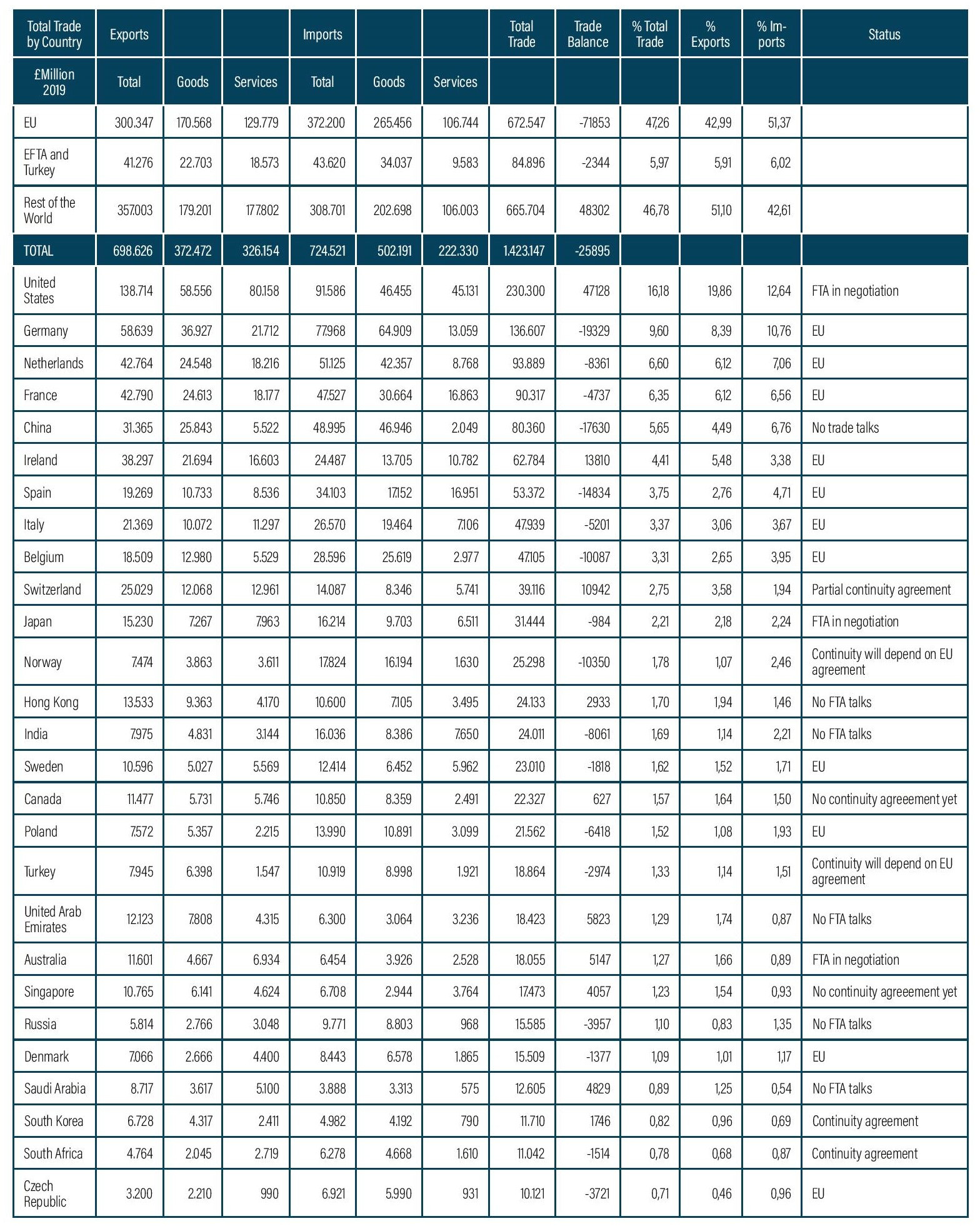

Annex 3: UK Trade Partners above £10bn per annum

The table below[1] shows the UK’s top trading partners, those with whom the UK had total trade of over £10 billion in 2019. These 11 EU and 16 non-EU countries total around 85% of UK trade, imports and exports. We also summarise totals for all EU countries, those with close relations to the EU through EFTA and Customs Unions, and the rest of the world. This shows the UK’s strong dependence on the EU for goods imports and exports, which is less reflected for services exports. However the figure for service exports to the US has for some years significantly exceeded the US figure for services imports from the UK, on which basis services exports may not look so different to the picture for goods exports in aggregate.

[1] All data extracted from this UK government dataset https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/internationaltrade/datasets/uktotaltradeallcountriesnonseasonallyadjusted