The Geopolitics of Online Taxation in Asia-Pacific – Digitalisation, Corporate Tax Base and The Role of Governments

Published By: Martina F. Ferracane Hosuk Lee-Makiyama

Subjects: Digital Economy

Summary

- Governments use taxation as a policy instrument to create a favourable business climate in the face of competition from neighbouring countries. Tech companies appear to be bearing the brunt of the blame associated with this geopolitics of tax, even though it is actually governments who set tax law and determine the international allocation of profit.

- The prevailing public perception that tech companies pay less corporate taxes is a myth: A comparison of the global effective tax rates (ETRs) paid by some of the world’s largest internet firms worldwide shows that they pay taxes which are on average with those of leading businesses across the Asia-Pacific region. In addition, the biggest companies from Silicon Valley pay similar or even higher rates than those paid by many other internet companies in the Asia-Pacific region.

- The real question is where corporate taxes are paid. Most businesses tend to keep their key functions and production capacities in the country where they were once founded. By extension, they also tend to pay their taxes in that country. If Silicon Valley was to engage in profit shifting, they would be moving their profits in the other direction: To Asia, where the growth rates are higher and corporate tax rates are lower – not vice versa.

- Moreover, Asian tax bases are not actually shrinking, but growing, since the invention of the internet. In other words, the tax problems we are seeking to address through sometimes draconian measures do not seem to exist. Tax revenues from corporate income taxes are growing at a faster pace than GDP or personal income taxes. Total corporate taxes collected in the Asia-Pacific region have more than doubled in the last decade.

- Blaming the internet for base erosion is likely to be a misconception created by national politics, or an attempt to protect the revenues of old telecom incumbents by blocking new, innovative services that compete with basic telecom services. It is difficult to find any other plausible explanation, as the combined revenues of the leading US-based internet services in the Asia-Pacific region are roughly equivalent to (at most) 0.1% of the USD 16.1 trillion trade in goods and services with Asia-Pacific annually. If base erosion and fairness were a real problem, there would be no other obvious reason to go after the internet firms while turning a blind eye to the remaining 99.9%.

- If all countries started taxing foreign exporters as though they were local businesses, every Asian export-led economy, or any country with a trade surplus, would be at a net loss – with the United States as a net gainer. Countries like China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam were showing strong surpluses on trade in goods and services in 2016, and would lose tax revenues if the principles were reversed.

ECIPE gratefully acknowledges the support for this paper from the Asian Trade Centre. e authors also thank Nicolas Botton for his able research assistance.

1. Introduction

Corporate taxation is always a controversial topic, and international taxation even more so. The issue of where and how much businesses actually pay in taxes has been exacerbated by globalisation and capital mobility, and in recent years, through digitalisation. But the prevailing public perception that tech companies pay less corporate taxes is a myth. In fact, they tend to pay more taxes than any other sector. The real question is where these taxes are paid.

This paper is focused on the conversation around corporate income tax in the digital age, rather than the broader issue of consumption tax relating to online transactions. The truth is that governments use corporate taxation as a policy instrument to create a favourable business climate for entrepreneurs and foreign investments in the face of competition from neighbouring countries. Moreover, it is a matter of how the tax system has been negotiated by the governments.

This geopolitics of taxation is a fact of life for many countries in Asia, especially those in the shadow of dynamic hubs like Singapore or major inner markets like China or Japan. Digitalisation plays a less prominent role in this fiscal geopolitics, as tax systems are never designed to benefit internet companies, but rather traditional manufacturers and financial institutions. Nonetheless, tech companies appear to be bearing the brunt of the blame associated with the geopolitics of tax.

However, the politics of international taxation predate the creation of the internet. While there are legitimate concerns about tax evasion (where companies abuse loopholes in unintended ways to avoid taxes), this is a very different matter from tax competition where companies make their business decisions by taking into account lawful tax policies of legitimate governments of major countries. In other words, the international tax system is working exactly the way the governments intended it to.

Also, it is widely – and incorrectly – assumed that this lawful tax competition between nations leads to base erosion, i.e. that a country’s corporate tax base shrinks due to tax competition. Rather, the data shows that this assumption is false as the tax base (and in particular the corporate tax portion of it) is in fact growing in Asia.

The principle of taxing corporations on where the assets are based (rather than where the consumption takes place) is internationally agreed.[1] That said, the taxman would want any business – foreign or domestic – to pay all their taxes in their jurisdiction rather than elsewhere. Some tax authorities wouldn‘t mind if foreigners paid twice – at home and abroad. For example, the EU countries have advocated globally for taxing online business on a discriminatory basis, which has led to a new OECD convention that provides legal grounds for its signatories to revise existing tax treaties and arrangements on a wholesale basis.[2] The purpose is to designate foreign online businesses as having ‘permanent establishments’ on their export markets,[3] and subject them to double taxation at home and abroad.

Contrary to their own economic interests, some countries in the Asia-Pacific region are being misled into following suit. There is no doubt that the internet has increased the ability of businesses to engage in trade without a costly physical presence in every country. Online advertising, e-commerce and mobile apps have levelled the playing field between Asian entrepreneurs and large Western conglomerates, and closed the economic gap between developing countries and advanced economies.

A debate on future taxation must firstly be clear about what the problem is, and who and what is causing it. Some populist voices have singled out the internet as the main culprit. It is a common cliché in management literature that the internet has rewritten many rules – but the government tax code is definitely not one of them. To selectively reverse internationally agreed tax principles for just one type of service is hardly consistent with the rule of law. Moreover, it would slow down the public’s access to innovative online services, which could only benefit dominant telecom operators – some of whom pay little or almost no taxes.

[1] See inter alia OECD, Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, 2013

[2] OECD, Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, 2017

[3] See Lee-Makiyama, Verschelde, OECD BEPS: Reconciling Global Trade, Taxation Principles and the Digital Economy, ECIPE, 2014

2. Online services pay taxes on average equal to traditional industries

The use of the internet has allowed more firms to export their products and innovative business ideas to succeed outside of their own home market. Online advertising and platforms like eBay and Alibaba have allowed even small family businesses to find customers overseas without establishing sales offices there; in the same fashion, digitalisation has allowed Indian outsourcing businesses to flourish.

However, the use of the internet itself has not provided any new conduits for multinationals and exporters to minimise their tax burden. The most common means of shifting profits (and thereby also where taxation occurs) involves trading goods and services at fictive prices between subsidiaries. For example, European luxury goods are sold at a fraction of their retail value to their own subsidiaries in Asia, thereby minimising customs duties paid at the border, and taxes can be paid in Asia where taxes are typically lower. Conversely, profits generated in Asia can be moved through ‘licensing fees’ that eradicate the profits in Asia, and through shifting the profits to some EU jurisdictions where revenue from intellectual property is exempt from taxation. Evidently, profit shifting is a practice that predates the digital economy, which companies use to avoid double taxation. More importantly, transfer pricing or profit shifting is not a practice that in any way has been enabled by or augmented by the internet or connectivity.

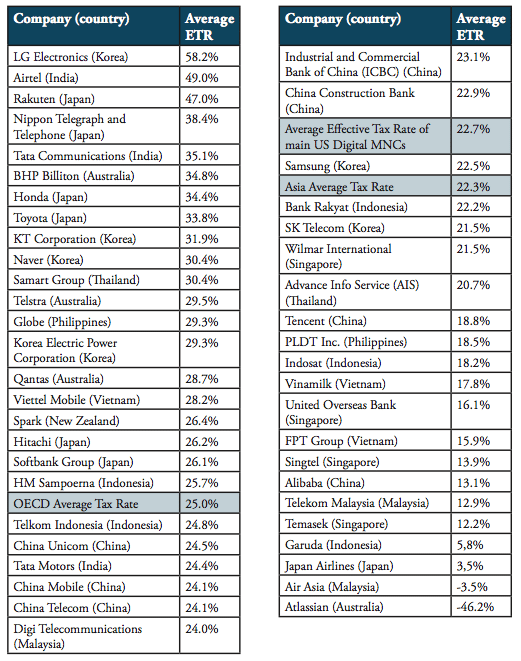

The fact is that internet firms are less likely to minimise their tax burden than traditional industries. A comparison of the effective tax rates (ETRs) paid by some of the world’s largest firms shows that internet firms providing online services pay on average similar taxes than other leading businesses across the Asia-Pacific region (Table 1). Unlike other services, online services and e-commerce platforms are also often subject to sales taxes in the overseas jurisdiction on what their customers pay for downloads or advertisements.

Moreover, some Asian manufacturing exporters or financial institutions receive preferential tax breaks while internet companies (regardless of their origin) belong to some of the least subsidised and least politically favoured sectors in most of the economies. For example, some major Asian enterprises (including the incumbent telecom operators) are state-owned, and are allowed to run losses or are exempt from corporate taxation.

Table 1: Average Effective Tax Rates (ETRs) of leading online services providers compared to other leading Asia-Pacific MNCs, five-year average (2012-2016) [1]

Source: Based on corporate income taxes paid and net income reported by the annual reports of the firms (supplemented by data from Ycharts.com, Bloomberg, Reuters and Shareinvestor.com, KPMG website)

Note: The average tax rate paid by American digital MNCs is calculated as an average of average effective tax rates paid by the five leading online services providers in the US: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, IBM and Microsoft.

In addition, leading companies in Silicon Valley pay similar, or even higher, rates than those paid by many other internet companies in the Asia-Pacific region, including internet firms like Tencent and Alibaba.

There are simple explanations as to why the American internet firms pay similar or even higher taxes than their counterparts in the Asia-Pacific region. Firstly – and perhaps most obviously – the globally agreed principles of taxation require that corporate taxes must be paid where the core functions or assets are placed and business risks are taken. For Silicon Valley firms, that means the US. However, statutory corporate income tax rates in the US are considerably higher than all of Asia-Pacific, which is why the effective tax rates of US firms also tend to be higher. If Silicon Valley was to engage in profit shifting, they would be moving their profits in the other direction – to Asia, where the growth rates are higher and corporate tax rates are lower – and not vice versa.

Secondly, the US is restrictive about allowing deduction of taxes paid to foreign governments. The US does not offer tax exemptions that open up possibilities for profit shifting like some European governments do for their retail and media businesses.

In conclusion, the new breed of online businesses is by no means unfair beneficiaries or exploiters of the current tax regimes, but quite the opposite. As both Silicon Valley and Asian internet firms evidently pay taxes, and do so at the average (or higher) rates than traditional offline companies, the issue is in essence about tax collection: Where (rather than if) corporate taxes are paid.

[1] Effective Tax Rates (ETRs) indicate corporate income tax paid as a percentage of the firm’s net income before taxes. See Box 1 for details on calculation of ETRs.

3. The geopolitics of taxation

Most businesses tend to keep their key functions and production capacities in the country where they were once founded. By extension, they also tend to pay their taxes in that country. Businesses remain in their original location, as long as the local business environment can support their expansion and overseas growth.

Some governments perceive they are naturally disadvantaged due to a smaller home market, linguistic or geographic distances, or short supply of skilled talent to support their startups – and such economies may seek to level the playing field by offering fiscal incentives. This is the geopolitics of taxation, where governments seek to design policies to overcome their geographical and developmental limitations. After all, governments are solely responsible for what fiscal policies they want to pursue and, by extension, how much tax revenue they want to generate. Meanwhile businesses – foreign as well as domestic – are obliged to simply try to adhere to the laws.

If governments create selective incentives for certain practices or industries, they are causing mismatching opportunities in their tax systems which only they are responsible for. Since the inescapable premise of running a privately-owned business is to maximise post-tax (rather than pre-tax) earnings, firms are merely responding to incentives (or disincentives) they are presented with by governments. If the international tax system is characterised by tax avoidance enabled by ‘hybrid mismatching’ – i.e. multinationals exploiting the geopolitics of tax – it merely shows government policies are working exactly as they were intended.

But taxes are not the main reason why businesses invest in or move to a certain location, actually far from it. There is a myriad of reasons why a corporation might decide to invest in a certain location, or to put its regional hub in a certain country. A number of factors may be at play such as proximity to markets, growth potential, need for infrastructure or services, subsidies, political risks, competition for talent, tariffs on inputs, or even whether the location offers a good quality of life for the management. Across a number of surveys, low corporate taxes very rarely make it into the top 10 lists of reasons, while the opposite – overly aggressive treatment by tax authorities – is a reason why certain investment locations are avoided.[1]

Yet, low tax rates are one of the most common incentives offered by governments to attract foreign business to invest, or to incentivise local businesses to stay. Taxes are one of the few factors that are directly controlled by a government, often imposed by decrees. Moreover, the impact from fiscal measures can be observed immediately (and by the voters) while the government is still in power, and perhaps seeking re-election. Thus, it is often perceived by the governments themselves that fiscal policy – i.e. corporate tax rates or subsidies – is one of the few effective tools of investment promotion.

Hence, low taxes may not be very important to business, but they are important to governments. Especially in the case of South-East Asia, several countries are also competing against each other on relatively similar terms with similar comparative advantages, costs of labour or geographic distances.

Asian-Pacific countries are not only competing amongst themselves, but also against their giant neighbour, China, with all its supply-chain efficiencies and low taxes. In fact, much of foreign direct investments (FDI) was re-routed towards China’s inner market (Figure 1) from ASEAN. Similarly, South Korea is not just facing competition from China, but also the more productive neighbour of Japan; Malaysia is wedged between the major business hub of Singapore, and the far more populous Thailand; and New Zealand sits next to the vastly larger and more economically diverse Australia.

Figure 1: FDI flows in China and ASEAN, 1990-2015 (in billion USD)

Source: UNCTAD Statistics, 2015

However, offering a business-friendly environment and fiscal incentives in select industrial sectors has always been a part of Asia’s trajectory to modernisation. For example, South Korea offered comprehensive fiscal benefits to foreign investors in its textile sector during its re-industrialisation in the post-war era; Taiwan followed the same path for the semiconductor industry, which was chosen as it was one of the few products it could export tariff-free due to its limitations to conclude trade agreements.

In conclusion, whether geopolitics of taxation is just ‘healthy’ tax competition or ‘unfair’ practice is almost immaterial. It is hard to see any government, small or large, letting go of taxation as a policy tool. It could only disappear through ambitious tax harmonisation and coordinated action, which entails giving larger or more prosperous neighbouring countries a say on domestic corporate taxes: In other words, it entails surrendering national sovereignty, which is yet to be achieved even in deeply integrated entities like the European Union.

[1] AlphaBeta, Digital Nation: Policy Levers for Investments and Growth, 2017

4. Is the corporate tax base even eroding?

The discussion could have ended with the conclusion that the question about taxation of the digital economy is ultimately a question of which governments exporters pay their taxes to, rather than the red herring of whether enough taxes are collected from internet companies. After all: Have tax bases in Asia actually been shrinking since the invention of the internet?

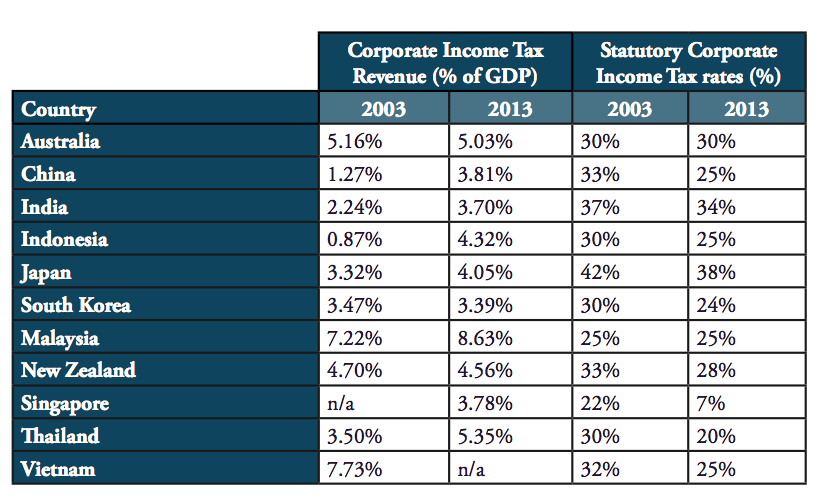

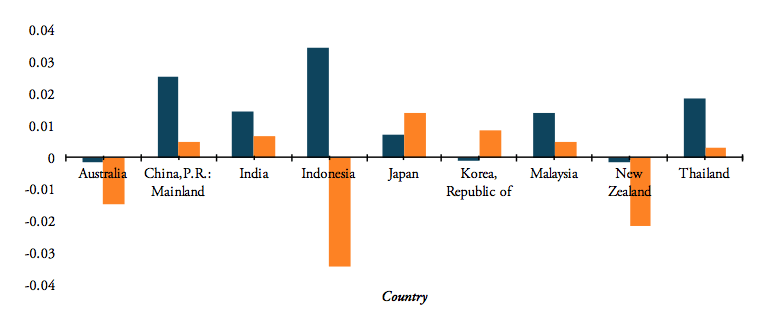

In fact, there is very little factual evidence for corporate income tax being under pressure across Asia, and most of the data actually points in the other direction: Government revenue from corporate income tax is steadily increasing, in both absolute terms and even relative to how their economies are growing. In most cases, corporate income tax revenues are growing at a faster pace than GDP (Figure 2), although the corporate tax rates are lowered or unchanged. In absolute terms, total corporate taxes collected in the Asia-Pacific region have more than doubled in the last decade – a period which overlaps with rapid digitalisation and the expansion of internet connectivity in these countries.

Table 2: Corporate Income Tax Revenue as share of GDP and statutory corporate tax rates, 2003-2013

Source: IMF World Revenue Longitudinal Data (WoRLD); KPMG

Countries that have considerably cut their corporate tax rates – e.g. Thailand, Indonesia and China – have seen a considerable boost of revenue. None of the countries have seen a relative decrease of their corporate tax revenues that exceeds much beyond an error margin. In other words, the tax problems we are seeking to address through sometimes draconian measures do not seem to exist.

This comparison of statutory corporate tax rates also shows that the emerging Asian countries have lower rates than the US (at nearly 40%). They are generally lower than most European countries too. Thanks to the higher growth rates in Asia, FDIs into the Asian-Pacific region increased more than five-fold in the last decade,[1] while the region’s share of global investment stock increased from 16% to 26%.[2] If anything, foreign companies are shifting profits to Asia – and Asian governments are able to fill up their tax coffers.

Another concern in the tax debate could be that personal income tax is being raised to compensate for the ‘loss’ of corporate taxation. Once again, this assumption is not supported by data. With the exception of highly industrialised South Korea and Japan (where corporate profits were more deeply dented by the global financial crises than other Asian countries), corporate tax intakes are increasing at a much greater rate than personal income taxes (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Changes in tax revenue relative to GDP (changes in percentage points), 2003-2013

Source: IMF World Revenue Longitudinal Data (WoRLD)

However, natural persons may seem less mobile than corporations in theory – especially digital businesses, as they actually hold few tangible assets. But in reality, very few startups move, leaving their original team behind. Spotify has remained in its home country of Sweden despite the high taxes and geographic challenges. Naver has remained uniquely South Korean, while Alibaba and other Chinese online startups are still headquartered in China, only choosing to raise capital overseas.

In light of these facts, it seems that the phenomenon of base erosion and profit shifting is more likely to be a misconception created by national politics, or an attempt to protect the revenues of old telecom incumbents by blocking new, innovative services that compete with basic telecom services. It is difficult to find any other plausible explanation, as the combined revenues of the leading US-based internet services in the Asia-Pacific region is roughly equivalent to (at most) 0.1% of the USD 16.1 trillion trade in goods and services with Asia-Pacific annually.[3] If base erosion and fairness were a real problem, there would be no other obvious reason to go after the internet firms while turning a blind eye to the remaining 99.9%.

Also, if all countries started taxing foreign exporters as though they were local businesses, every Asian export-led economy, or any country with a trade surplus would be at a net loss – with the United States as a net gainer. Countries like China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam were showing strong surpluses on trade in goods and services in 2016, and would lose rather than gain tax revenues if the tax principles were reversed.

The debate on corporate taxation is – as far as Asian economies are concerned – a dangerous solution in search of a problem.

[1] Based on UNCTAD Statistics, 2015

[2] ibid.

[3] Based on total goods and services trade, developed and developing Asia and Oceania, using UNCTAD Statistics, 2015; Total internet US services revenues extrapolated from the combined revenues of Google Asia-Pacific and Facebook Asia-Pacific reported in their annual reports.

5. Conclusions: Ending the geopolitics of tax

The conclusion of this analysis is unmistakeable. We live in an imperfect world where distortions are intentionally and selectively imposed by legitimate governments, and firms respond to these distortions exactly as intended. However, digitalisation is neither a beneficiary nor a cause for the resulting geopolitics in taxation, and there are no legitimate reasons for singling this sector out – especially as the taxes they pay are equal to or higher than those paid by traditional industries. This is not a question of whether online services pay taxes – but where.

Yet domestic politics often see profitable internet companies as easy targets: Internet companies often have low or no staff count in other countries and don’t leverage many votes in elections – yet thanks to their common usage, they are widely known amongst voters. Also, news media across the world have reported stories on how some tech entrepreneurs seem to live the life only a few could ever dream of.

But as we have seen, the links made between internet businesses and tax evasion or tax erosion are counterfactual. If anything, the internet has led to an expanded corporate tax base thanks to increased overseas sales for domestic firms (and thereby higher taxable profits) and increasing the number of startups. As most Asian countries are just beginning their efforts to streamline business regulations and digitalise government services, the real boom of entrepreneurship is yet to come.

Also, as the current trend is moving towards consumption taxes rather than corporate taxes, governments are also able to expand their fiscal income by levying tariffs or taxing transactions enabled and generated by e-commerce and online services. Online platforms have allowed even the smallest firms from the most disadvantaged Asian economies to engage in exports, evolving into so-called ‘micro-multinationals’. 90% of small businesses on eBay export to other countries, compared to just 5% amongst those who are not on the platform.[1] A World Bank survey also showed that Vietnamese firms engaged in e-commerce increased their productivity by 3.6 percentage points.[2]

Obviously, what is at stake is not just about ‘taxing a few rich Silicon Valley companies’, but whether digitalisation should be discouraged, rewarding stagnancy and promoting a less efficient use of resources. Such misallocations created by poorly designed tax systems could take several decades to undo, while any taxes tend to become a permanent feature once they are introduced.

Moreover, if the new multilateral instrument under the OECD is abused by governments to try to deem online businesses as having ‘permanent establishments’ in each country (and therefore subject to local taxes), it would result in online services – unlike other services like financial services consulting business – never be able to export from another country. This would run afoul of a number of commitments under international trade law, where countries have committed under the rules of the World Trade Organization and other trade agreements to keep cross-border trade open on online processing services.[3]

The fact that Asian SMEs and multinationals are able to trade without physical presence is a productivity gain, while there is no evidence of the fact that internet companies or the use of the internet have caused any loss of tax revenues. The commercial use of the internet has allowed emerging economies to leap-frog into modern services economies despite inadequate infrastructure in telecoms, logistics or banking. This is particularly important for highly decentralised and geographically dispersed nations like Indonesia, the Philippines or China, for whom the internet has opened up a fast-track to growth – and an increase in fiscal revenues – that was not open to Japan and the Asian Tiger economies in the 1960s and 1970s.

Asian governments could give in to populist and corporatist calls for taxing internet companies, but such decisions are never taken unilaterally in a vacuum. This would be followed by other countries that will impose corporate taxes on Asian firms exporting overseas. Asian countries – with large net inflows of investments and major export revenues – are the biggest losers from a territorial tax system where corporate taxes are paid based on where consumption takes place, rather than where corporate functions are placed.

[1] eBay, Micro-Multinationals, Global Consumers, and the WTO, 2014. Available at: https://www.ebaymainstreet.com/sites/default/files/Micro-Multinationals_Global-Consumers_WTO_Report_1.pdf

[2] World Bank, World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, World Bank, 2016

[3] Lee-Makiyama et al, supra note 4