The Economic Impact of Local Content Requirements: A Case Study of Heavy Vehicles

Published By: Hanna Deringer Fredrik Erixon Philipp Lamprecht Erik van der Marel

Research Areas: European Union Regions WTO and Globalisation

Summary

The use of local content requirements (LCRs) has been growing for a long time. Used by developed as well as developing countries, they aim to promote the use of local inputs and serve the purpose of fostering domestic industries. Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the USA are very frequent users of LCRs. India is by far the most prominent user, followed by Brazil. While LCRs might have perceived benefits related to specific policy goals in the short term, the damaging impacts of LCRs evolve over time and outweigh short term benefits. This study estimates the economic impact of LCRs in a selected sub-sector of motor vehicles, where they are frequently used, i.e. the heavy duty vehicles subsector.

ECIPE collected LCRs which affect the selected subsector in a database, classifying them by three different dimensions: their different types, their scope, and their level of impact. This database is used as a basis for the assessment of the economic costs of these LCRs for BRICS countries. Overall, 72 different LCRs have been identified. Most LCRs were found in Brazil and Russia, which each apply 20 measures, followed by India with 15 and China with 13 measures. Finally, in South Africa there are only 4 measures in place which affect the heavy vehicles sector. The analysis finds that most LCRs are related to government procurement, financial support and business operations, as well as to export measures. In addition, we find that the LCRs that are related to financial support and business operations have generally a high impact. For the purposes of this study, the cost of the collected LCRs has been estimated by translating their negative effects into ad valorem equivalents (AVEs). Brazil and Russia apply the most distortive LCRs for heavy vehicles with an estimated increase of their import price of 15.6 and 11.1 percent in both countries respectively. China and South Africa both show low AVEs of 4.5 and 3.3 percent respectively, and India’s LCRs are least distortive with an estimate of 2.2 percent.

Estimating the impacts of the collected LCRs on the economy in the BRICS countries shows that their impact is at least threefold. First, the LCRs have a negative impact on trade in heavy vehicles in the BRICS countries. The identified LCRs are estimated to restrict imports of heavy vehicles by -21% and -12% in Brazil and Russia, while for the other BRICS countries imports of heavy vehicles are reduced between -9.3% and -3.7%. Although to a much lesser extent, the identified LCRs also reduce BRICS countries’ exports of heavy vehicles. Second, LCRs significantly increase the prices for imported heavy vehicles leading to higher prices for firms as well as consumers. The prices firms have to pay for intermediate goods in the heavy vehicles sector are estimated to increase up to 2.9% and 4.8% in Russia and Brazil. Consumer prices for heavy vehicles are estimated to rise between 0.2% and 5.4%. Third, our estimations show that LCRs increase industry output in the targeted sector, but only at the expense of other closely related industries which decrease their industry production.

For example, while industry output in the heavy vehicles sector increases between 0.2% in China and 10.37% in Russia, the domestic production of other transport equipment and other machinery in Russia and Brazil decreases by -0.16% to -0.37%. While it is only natural that industry output that is subject to protection by LCRs increases, the analysis shows that this effect is outweighed by the detrimental side effects. LCRs raise the price of the product it protects and of the product which requires protected inputs, in this case heavy vehicles. As a result, this raises expenditures for every buyer in the economy, which has a depressing effect on sales and output also in other industries. Final consumers as well as firms have to reallocate resources from other areas in order to pay for more expensive vehicles and vehicle parts. Over time LCRs can therefore lead to lower competition, less innovation, and less product variety in the domestic market, which reinforces the negative effects of LCRs.

The analysis illustrates the detrimental impact of LCRs, highlighting again the need for policymakers to address the growth of LCRs and their significance in modern protectionism more thoroughly. A first multilateral option is an increased use of complaints through the WTOs Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) in order to eliminate them and to have specific LCRs declared incompliant with WTO rules. This would also establish necessary additional jurisprudence covering a wider set of LCRs. A second multilateral option is the start of negotiations in the WTO. The topic of LCRs should indeed be high on the new working agenda in order to clarify current rules on LCRs and to obtain stronger negative rules against their use. If negotiations among the entire WTO membership do not progress, a “coalition of the willing” of member countries could engage in negotiations with the aim of clarifying rules and making them stronger. These negotiations should be supported by a larger body of economic analysis on the full range of existing LCRs. In addition, negotiations on bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) should lay a stronger focus on LCRs. Current EU negotiations on FTAs offer a good ground for such efforts and LCRs should be front and centre in EU FTA negotiations planned in the future.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the research assistance by Nicolas Botton, Julie Richert and Sebastian Schuhmann.

The Use of Local Content Requirements in the World Economy

Local content requirements (LCRs) have a long history. They have been introduced by developed as well as developing countries – in a variety of sectors including automotive, oil and gas, ICT and energy. Especially after the 2008 financial crisis the world has experienced a rapid increase in the use of LCRs. Many countries have introduced discriminatory trade measures with the purpose of benefiting domestic firms at the expense of foreign competitors. Such measures have been a common feature of public procurement policies.

As an effect of increased liberalization and global trade integration, especially after the Uruguay Round, governments cannot use tariffs as much as before for protectionist purposes. However, governments have increasingly turned to non-tariff barriers (NTBs) and are using them with greater ease and flexibility. Local content requirements (LCRs) is a case in point. Such measures are often obscure and, in the first place, difficult to observe. Unlike tariffs, they are neither numerical nor upfront. Some countries have given LCRs a central role in their recent trade policy and consequently introduced more discrimination and restriction in how exporters can access markets. Their growth and consequences have now become a major concern for global trade policy and should warrant far more attention, both in economic analysis of trade and in the articulation of trade policy.

This paper aims to support both these ambitions. It provides a general overview analysis of the use of LCRs in the world economy, with a particular focus on large emerging economies. Furthermore, it estimates the economic impact of LCRs in a selected sector, motor vehicles, where they are frequently used. The analysis also includes a more specific analysis of the heavy duty vehicles subsector. Finally, the paper outlines ideas for how policymakers can address the growth of LCRs and their significance in modern protectionism.

Defining LCRs

Many national economies have been struck by the effects of the world financial crisis in 2008. All countries have tried to find ways to rehabilitate. Some have reacted with ambitious policy reforms with the ambitions to boost the local economy, foster domestic growth and mitigate the negative impact of troubled world economy climate.

Some of those reforms (re-)introduced aspects of protectionist policy. One type that has experienced increased attention in this context are LCRs. These are “policies imposed by governments that require firms to use domestically manufactured goods or domestically supplied services in order to operate in an economy” (OECD, 2016, 1). There are ongoing discussions about the clear definition and limitation of the category LCR proposing the inclusion of distinct types of NTBs or other types of localization requirements like rules of origin. Examples for such policies are India’s LCR on foreign enterprises in the solar panel industry and ICT equipment to include a certain share of domestically produced inputs or LCRs for digital service providers that require local data storage in Russia, South Korea and Venezuela (Ezell et al., 2013, 8). LCRs can generally include measures on condition tax and price concession on local procurement, condition bailouts, government contracts and export financing on local sourcing, tailor import licensing procedures to encourage domestic purchase, reservation of certain lines of business for domestic firms, requirements on local data storage and analysis and local product tests (Evenett, Fritz, 2016, 21).

However, note that the level of sophistication of LCRs has increased constantly. LCRs can also include requirements related to local assembly, and benefits such as tax cuts, tax refunds or complete tax exemptions are often implemented for domestically manufactured goods that comply with a certain amount of local content. These practices can also come in the form of discriminatory tax measures or provisions that favor local businesses, locally assembled products or the requirement of local content in goods (European Commission, 2016, 7). In certain cases, foreign producers can make use of duty-free imports of components, under the condition that the local content of their importing products is of a certain amount. Some countries implement preferential procurement regulations which grant preferences for local products and, in certain cases, markets are even completely reserved for locally produced goods (Ramdoo, 2015, 11 & 21).

Furthermore, it has to be stressed that the impact of LCRs for affected businesses and the economy where they are implemented goes beyond the mere direct measures described above. Regarding the effects on foreign companies that look to enter a market in another country, the harmful effect of LCRs is also due to a level of uncertainty that they create in the regulatory environment. Due to uncertainty of interpretation of LCRs these companies have to invest significant resources into trying to adapt to LCRs and into gathering information on how they will develop and on what the implementation of a specific LCRs will entail for their business operations. LCRs have evolved in sophistication over time and the more specific LCR requirements are expressed the more detrimental the impact can be for business. This is true, for example, for specific R&D requirements that companies have to comply with. Furthermore, LCRs can affect the business strategy of a company for the market in question.

LCRs can also have overall detrimental spill-over effects for the entire economy in the country in which they are implemented. To comply with LCRs, many companies are applying the strategy of relying on local services providers in the market in question. This entails a strong bias between production and services which is artificially created by LCRs. Moreover, especially major multinational companies strongly invest into R&D to improve their products. Certain advanced parts that have profited from strong investments in R&D are, however, excluded from the target market as LCRs require using locally produced parts. Thus, the implementing country is shielding itself from profiting from international R&D investments made by trading partners. More specifically, this can lead to a deterioration of long-term competitiveness of the companies in the country which implements the LCRs.

Most importantly, LCRs can artificially reduce the market size that a foreign company can cover, reducing the company’s incentives to export to the market in the first place. The economy implementing LCRs is depriving itself from having access to competitive and advanced products, which – in the case of trade in automotive products – can have a harmful effect on transport efficiency and sustainability within the market and create costs for consumers. Furthermore, LCRs increase the cost of production which decreases the incentives to export from the market in question.

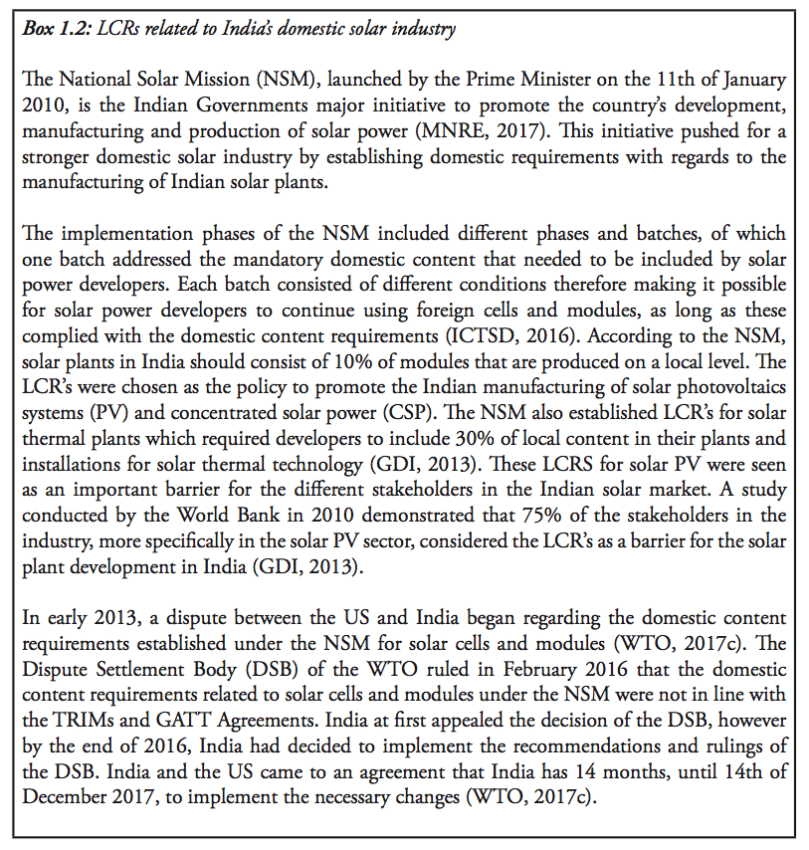

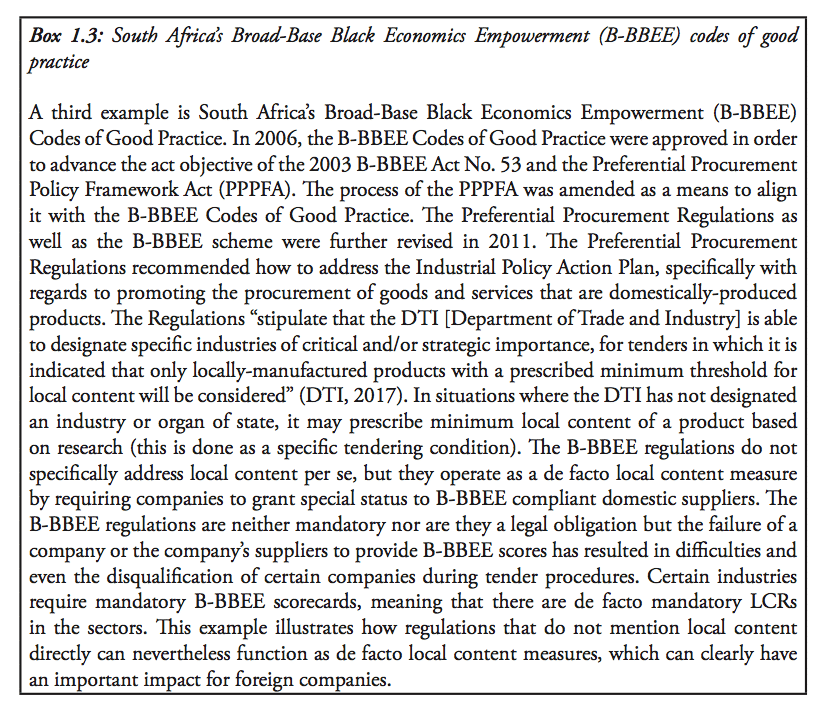

To illustrate these negative impacts for foreign companies and the overall economy implementing the LCR, three examples of specific LCRs will be briefly mentioned below.

The Growing Use of LCRs in the World Economy

Just like other types of NTBs, LCRs have existed for several decades already. The frequency of its application in recent years, however, is striking. Various countries have applied LCRs as a protectionist measure at different times in different contexts in order to address economic turbulences (Semykina, 2015, 4f). Therefore, NTBs have appeared in waves linked to economic cycles, like the Smoot-Hawley tariff escalation following the Great Depression in 1929. In addition, throughout the last century in many cases governments have favored domestic companies in assigning contract for public procurement (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 35). Hufbauer et al. (2015, 2) even claim that LCRs are rather the norm than an exemption in public procurement. Hence, earlier types of LCRs mainly addressed public procurement and mandate allocation for publicly financed projects (Cimino et al., 2014, 1).

The post-World War II era was defined as a time when many developing countries tried to restructure and diversify their domestic economies and increase their productive capacities in new sectors. They invested in certain sectors to improve their international competitiveness. For example, Latin American countries tried to expand their natural resource-based sectors and Asian countries increasingly sought to exploit their comparative advantage in highly skilled labor-intense sectors (Tordo et al., 2013, 18). Support by complex protectionist policies imposed by the governments became an incrementally common feature at that time, for example in 1953 when the Brazilian president Vargas urged the national oil company Petrobas to just use workers, capital and technology with Brazilian origin. Developed countries also strategically used LCRs to promote the growth of selected industries. In the 1970s, Norway imposed LCRs in its oil and gas sector for the first time.

The policy reversal started in the 1980s with new attempts to free up trade and take away various distortions of competition. World trade was gradually liberalized and some industries that had been privatized and deregulated showed greater appetite to take a larger role in trade policy. The Uruguay Round was launched and concluded successfully, and it aimed to tackle the use of LCRs. Even earlier in 1984 after a complaint brought by the USA, the Administration of the Foreign Investment Review Act (FIRA) Panel of the GATT ruled in a dispute settlement process that a LCR imposed by Canada was inconsistent with the national treatment obligation according to Art. III:4 of the GATT. The Uruguay disputes between developing and developed countries led to a compromise about the limitation of the legality of LCRs to certain Articles of the GATT provisions (Article III and Article XI). The agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs) introduced by the WTO in 1994 again decreased legal opportunities for LCRs. However, in the 1990s many developing countries missed out the expected growth effects and questioned the efficiency of the undertaken trade liberalizations. A reversion to bigger government interventionism was the consequence (Tordo et al., 2013, 19). Many sought to overcome their strong dependency on other economies and aimed at export diversification. Therefore, policy was directed towards the promotion of the development of certain industries.

But despite the deeper integration of world trade and stricter and binding WTO rules, LCRs have quietly returned and been transformed into new types that are always one step ahead the trade regulation framework. This also highlights problems in the accountability of trade rules violations in the current world trade governance (Evenett, Fritz, 2016, 21). Still, LCRs became subject to numerous dispute settlement cases in the WTO which often led to penalties (Ezell et al., 2013, 13). Politicians have simply shifted from more transparent and direct forms of protectionism towards more “opaque” behind-the-border NTBs. D’Costa (2009, 621) argues that “even under globalisation, economic nationalism in subtler forms can be practiced.” Despite the long existence of LCRs, the increase of their appearance in recent years as well as an increase in their complexity is remarkable (Ezell et al., 2013, 13). Also, the European Commission addressed recent LCRs as new types of covert protectionism (Von Unger, 2016). Many LCR may even remain unnoticed because of inadequate information and late notification to the WTO (Cinimo et al., 2014, 11). Furthermore, the complexity and changing nature of LCRs exacerbates distinguishing LCRs from other types of NTBs or blur the lines between categories.

Many governments increased their use of LCRs during the global financial crisis. These measures have been applied in a variety of sectors including automobile, information technology, healthcare and agriculture (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 36). Some sectors show an especially frequent use of LCRs, though, namely the energy and information technology sectors (Cimino et al., 2014, 2). The questions of which sectors are affected depends on the specific nature of each LCR. Some even have a very sector-specific design. Furthermore, it is crucial whether the LCR is trade- or rather investment-related. In recent years, large economies with high population have been keener to impose LCRs. One reason could possibly be that they assumed their market size big enough to attract large scale FDI despite occurring protectionist measures (Stone et al., 2015, 14). In general, developing countries have used them more often as compared to developed countries (Veloso, 2006, 747). Countries with higher GDP have implemented LCRs rather in sectors depending on services while countries with lower GDP showed a higher number of LCRs in industrial sectors (Stone et al., 2015, 14). There is another correlation between the level of unemployment in the whole economy, as well as in the specific sectors affected, and the LCR used (Stone et al., 2015, 16).

Note that there are perceived benefits of LCRs and governments might resort to their use for justifiable policy goals. By imposing LCRs governments might try to promote general political goals like maintaining or improving the domestic employment, attracting FDI and companies from high-value added and R&D intense industries, and increasing the access to foreign technology (Stone et al., 2015, 17; Veloso, 2006, 750; Ezell et al., 2013, 4). Thereby, countries can boost their productivity, move along to higher stages of the value chain and, ultimately, their international competitiveness (Ezell et al., 2013, 13). Spillovers triggered by a large level of local content act as drivers of these processes. As a result, countries may be able to diversify the economic portfolio and develop other industries around LCR-protected sectors (Semykina, 2015, 5). LCRs can also serve as a political tool for achieving justifiable environmental goals particularly in the renewable energy sectors. Countries that use LCRs in these sectors include Brazil, Canada, United States, South Africa and others. The narrative of LCRs in this sector suggests that “high financial support for renewable programmes might not be publically supported if there were no local benefits” (Kuntze, Moerenhout, 2013, 34). This sector is very delicate as it has to pay attention to the twofold challenge of achievements in climate change mitigation on the one hand and energy security on the other (IEA, World Bank, 2013). However, despite perceived benefits related to such policy goals, in the long-term damaging impacts of LCRs frequently outweigh short term benefits.

Single measures may have been announced to be just temporary but turn out to be more permanent (Stone et al., 2015, 12). A famous example is the Buy-American Act of 1933 that has been amended several times in the aftermath but never been repealed (Hufbauer et al. 2015, 2). In many cases governments even choose to avoid providing official reasons for the implementation of LCRs. (Stone et al., 2015, 14). LCRs imposed in response to the 2008 financial crisis were designed especially for encountering the rising unemployment. Earlier LCRs rather had a wider array of motivations including the protection of infant industry (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 36). This holds particularly true for developing countries entering technology sectors like information technology or renewable energy sectors (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 2).

The Detrimental Impact of LCRs

Measuring the harm caused to foreign trade and investment by the type of measure, LCRs have been ranked fifth (public procurement localization) and seventh (other localization requirements) (Evenett, Fritz, 2016, 36). The other measures that are on places one to four are state aid, trade defense, import tariffs and export taxes or restrictions, while trade finance measures are on sixth place. (Evenett & Fritz, 2016). LCR measures related to trade can take on various forms but an increase has been observed in the use of LCRs related to data localization requirements. As data flow has become an essential aspect of trade, LCR measures related to this have an impact on a majority of sectors within an economy (OECD, 2016, 3). There is an increasing effort to control the local storage and processing of data as well as the movement of personal data. LCRs are highly common in the form of discriminatory government procurement, which reduces the number of eligible firms to enter a market. This reduces output and employment while increasing market power and procurement costs (OECD, 2016, 3). Some experts already perceive this type of protectionism as “perhaps today’s greatest threat to the further liberalization of the global trading system” (Ezell et al., 2013, 5).

The natural consequence is a growing awareness amongst policy makers and in the business world about the rise of (neo-) protectionism and LCRs particularly. The increasing number of reports published by official and private institutes in recent years are indicators for this development (Stone et al., 2015, 11f). LCRs became a topic on international economic conferences (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 13). Furthermore, the website GlobalTradeAlert.org was established in 2009 collecting all monitored discriminatory trading barriers in world trade as well as the Trade and Investment Barriers Report (TIBR) provided by the European Commission yearly since 2011. The US Trade Representative (USTR) established the Trade Policy Staff Committee Task Force on Localization Barriers to Trade in 2012. Theoretic considerations on LCRs date back to the 1970s starting with Baldwin and Richardson (1972), followed by Grossman (1981), Mussa (1984), Davidson et al. (1985), Krishna and Itoh (1988). Further literature concerning the effects of LCRs in different economic settings has been subsequently published by Richardson (1991), Moran (1992), Belderbos and Sleuwaegen (1997) and Tomsik and Kubicek (2006).

However, the number of LCRs does not necessarily indicate the significance of their trade distortion (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 4). Also, despite the large majority of literature pointing out the distorting (long-run) effects of LCRs, there remain voices that highlight the potential advantages following the implementation of a LCR with reasonable content and under certain conditions (Veloso, 2006, 749). One example is the oil and gas industry in Norway that has been regulated by LCRs and favored national companies even if they were not the most efficient (Tordo et al., 2013, 18). This success story depended on a variety of other factors, though, like the human capital, the high quality of institutions and related industries as well as the right timing (Heum, 2008).

The Current Use of LCRs in the World Economy

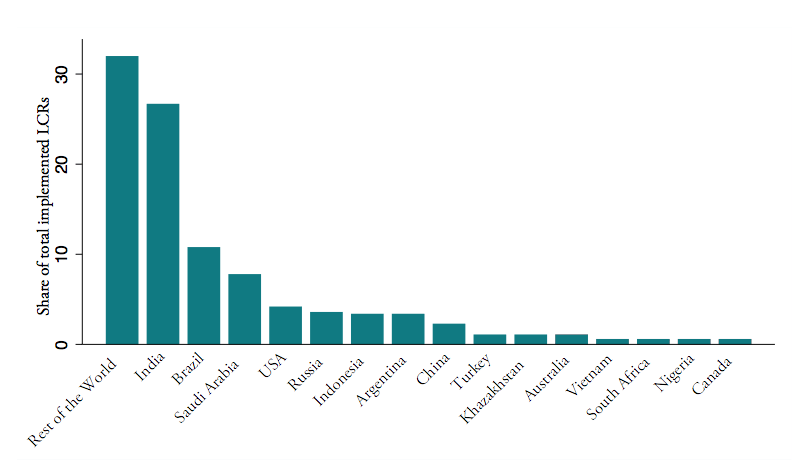

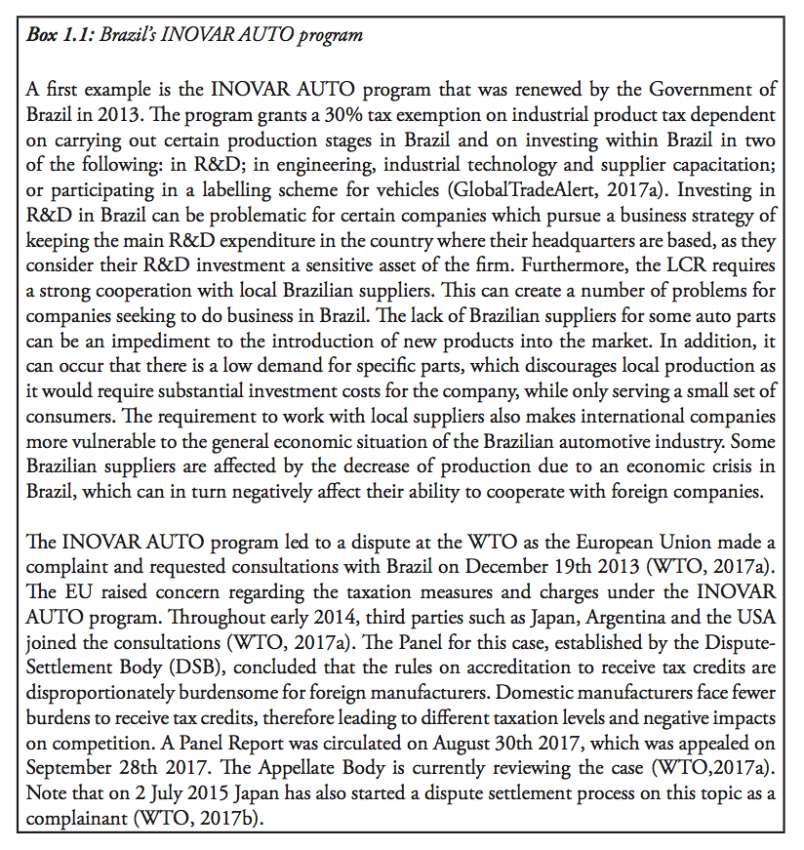

According to the GlobalTradeAlert database, the countries with the currently biggest activity in LCRs are Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the USA (see figure 1.1). India is by far the most prominent user of LCRs, accounting alone for more than a quarter of global LCR use. Also Brazil stands out in terms of prominence of LCR in its recent economic policy (Ezell et al., 2013, 12). It has introduced more LCRs than any other country after 2008 (Hufbauer et al., 2013, 36). Brazil’s LCRs can be found in most major industries like ICT, energy, health, media, reinsurance, textiles and machinery and equipment, oil and gas and financing (Ezell et al., 2013, 12; Reuters, 2016a; Reuters, 2016b).

Figure 1.1: Share of globally implemented LCRs by country (%)

Source: Global Trade Alert

Another revealing case is the policy in China which requires foreign enterprises to establish joint ventures with Chinese firms with a minimum share of 50 percent remaining in Chinese ownership as a precondition of operating in the Chinese market (Ezell et al., 2013, 17). That gains additional weight considering that China has recently become the biggest automobile market in the world, which grew by nearly 14% in 2016 and is expected to reach 29.4 million sales (5% growth in sales) in 2017 (Nakamura & Tabeta, 2017; Tang, 2012, 5). Many foreign companies comply with this rule and reportedly joint-venture products consist up to 80% of foreign components (Tang, 2012, 24). The majority of all leading automotive manufacturers have established joint ventures in China as a means to produce locally and avoid the restrictions imposed on foreign automobile companies in the Chinese market (EU SME Centre, 2015, 13). International automobile manufacturers are most dominant in the passenger vehicle segments. However, these remain foreign manufactures that have formed joint ventures with domestic partners. Overall, the foreign investment possibilities in the automotive sector remain restricted (EU SME Centre, 2015, 17).

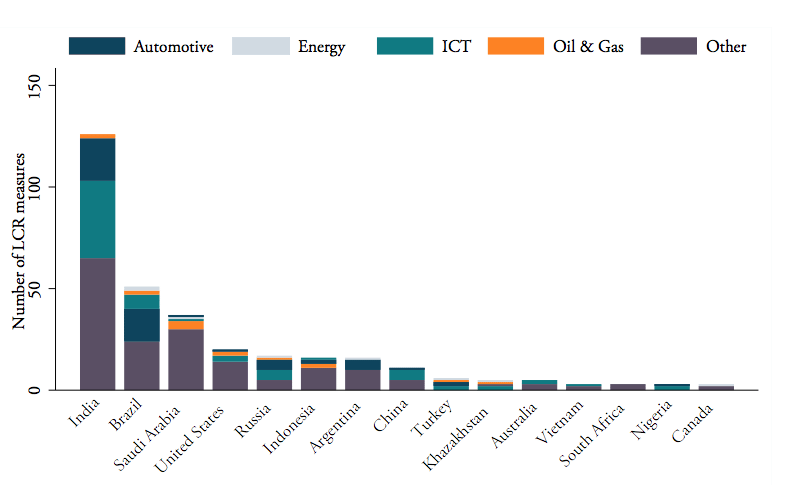

Also, the USA introduced massive fiscal programs as a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis. The America Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 included clauses requiring that all iron and steel purchased using ARRA funds has to be produced domestically (Cimino et al., 2014, 2). An overview of the global top 15 countries of currently implemented LCRs is provided in figure 1.2, including information on the main sectors of global LCR use.

Figure 1.2: Overview of currently implemented LCRs

Source: Global Trade Alert

The Economic Impact of LCRs

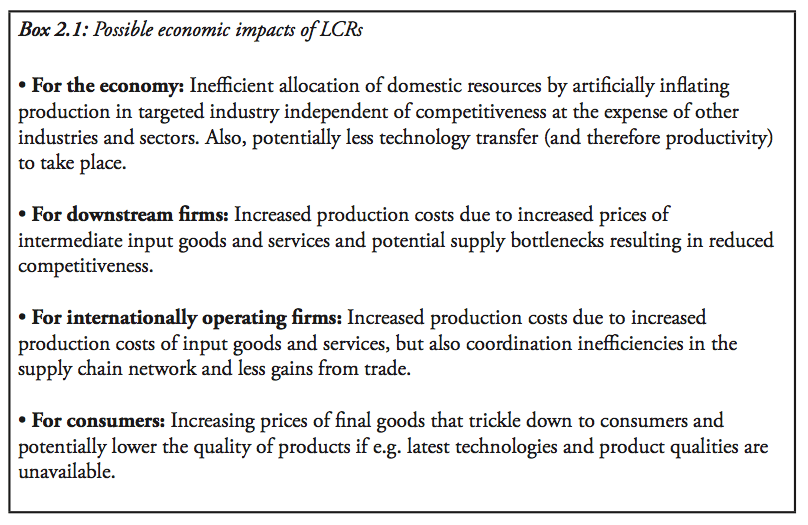

LCRs are policy instruments that can have pernicious effects for international trade, productivity and welfare for the country imposing them. LCRs artificially increase the use of input content from domestic suppliers where they apply. This creates inefficiencies in the supply chain for the firm using these inputs, because more competitive inputs are not (internationally) available for the company. More than often domestic input suppliers are not the best ones in terms of price and quality for domestic and international operating firms. LCRs therefore limit the availability of competitive products in the domestic market when the company cannot import better or cheaper inputs from abroad.

As a result, when forcing domestic companies or firms to acquire intermediate inputs from local suppliers rather than importing them, the country that imposes the LCR prevents companies from reaping gains from trade. A final negative economic effect of LCRs is that when countries impose these measures, a firm that is also an investor would be inclined to invest less in the domestic country. This could eventually lead to less technology transfer and process upgrading for the country, preventing the transmission of positive spill-over effects down the supply chain.

Furthermore, LCRs can create amplifying inefficiencies because of the fact that today’s trade patterns are distinctively marked by international supply chains. This means that inputs crisscross international borders many times before becoming a final good, from the source country where the initial input is produced to the last country where it is finally turned into a final good. Any distortion in this process requires great coordination by international firms. Over the last few decades, intermediate input trade has grown significantly and as a trade flow it has become more sensitive to any type of trade policy costs when compared to final goods trade (OECD, 2009). When government impose LCRs, they therefore create additional inefficiencies for multinationals. These firms need to reorganize their complex supply chains and are forced to incur additional coordination costs. In sum, LCRs not only constrain gains from trade, but also lead to higher production costs which can result in higher domestic prices and can even potentially create productivity losses.

Up to date there are very few studies analyzing the inefficiencies associated with LCRs – how to what extent they have a negative impact on the economy as a whole. Moreover, we still don’t know in which ways LCRs are distortive for trade. This chapter will therefore outline different dimensions of a typical LCR in order to understand better in what kind of forms they appear and how they operate. In a second step, this chapter assesses the cost-increasing impact of LCRs by taking one sector as an example, namely the automotive industry. In particular, we take the example of the heavy-duty vehicles industry which includes heavy vehicles like buses and trucks, but excludes passenger cars. The conclusion is that not all types of LCRs are equally distortive and their cost impact depends on how they are designed.

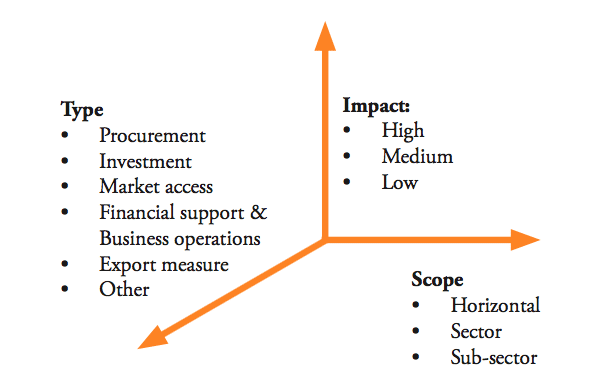

The Cost Dimensions of LCRs

Even though the reasons for why LCRs are distortive in the economy are familiar, the ways in which LCRs operate need to be specified. To assess the channels through which LCRs are cost-enhancing for firms, it is first necessary to understand their characteristics. According to ECIPE’s collection and assessment of LCRs in BRICS countries which affect the heavy vehicles sector and which are listed in Figure 2.1, LCRs can be mapped according to three dimensions: namely their (a) type; (b) scope; and (c) impact. Each of these three dimensions affect the economic burden of an LCR in a different way as demonstrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Cost-dimensions of LCRs

Source: ECIPE

The first element of an LCR to consider is the type of measure it can take. Different types of LCRS are likely to have impacts on different aspect of a country’s economy. LCRs can target different policy areas such as investment, trade and import policies or government procurement programs. LCRs can also stipulate how a firm should source inputs and thereby restrict imports indirectly. All these different types of LCRs therefore affect different types of economic activities such as local sales, exports and imports, or the investment of (foreign) companies and sales to foreign governments. Across all measures, our assessment classifies LCRs into six broad groups, namely:

- Public procurement: LCRs as a condition to participate in public tenders and access the local procurement market;

- Investment: Local content requirements as a precondition for investments to take place, e.g. joint stock requirements;

- Market access: LCRs specifically addressed to the tradability of goods and services across borders setting conditions for preferential market access in terms of reduced tariffs, import licensing schemes etc.;

- Business operations as well as financial support: includes measures such as preferential financing schemes and tax schemes based on the use of local goods and services and the finance of production of capital goods destined for exports;

- Export measures: Measures that stipulate export promoting preferences based on the use of local inputs, thereby generating additional trade rather than restricting trade

- Other requirements: Measures that fall outside the scope of these four categories, for example, the local storage of data.

This classification by type is important not only because they differ in terms of the economic area they apply to but they also affect different types of costs for companies. For instance, LCRs related to market access and business operations merely increase the operational cost structure as the producer would be forced to source an (input) product against a higher price from a local provider. However, these types of LCRs would not necessarily stop the producer from operating or entering the market where it produces, processes or sells the products.

On the other hand, however, local content requirements regarding investments or public procurement may result in restricting investments abroad and thus affect a firm’s fixed costs. They could also be so strict that the producer is deterred from undertaking any investment in the local market or to undertake a bid for a procurement project. Such types of LCRs could potentially have larger negative trade impacts than those related to market access and business operations and financial support.

The second dimension of an LCR to consider is its impact. The impact of an LCR is defined in terms of the measure’s restrictiveness for trade and thus the costs of trading. Increasing levels of restrictiveness mean that LCRs have a greater level of distortion regarding the costs for companies facing the policy requirements. Figure 2.1 differentiates between three broad categories of level of impact that ranges from (1) low to (2) medium, and finally (3) high. The impact of an LCR may actually differ according to the industry to which it applies and as a result depends on how the LCR instrument has been precisely formulated.

For instance, an LCR related to the local storage of data, which forces producers to use domestic data service providers, would have a much lower perverse effect for the automotive industry than for firms active in the software sector. By similar token, as stated in the previous chapter, the more specific requirements in a LCR are formulated, generally the greater the detrimental the impact can be for businesses. A very specifically formulated LCR for a sub-set of a larger sector could therefore classify as having a high impact if the design of the LCR is stringent despite being applied only to a small sub-sector. However, this level of restrictiveness only captures the second dimension of the impact of an LCR.

As a final dimension of LCRs we consider their scope or sectoral coverage. Some LCR measures are formulated for a narrow industry only and may therefore have overall a less distortive impact on a country (or industry) than an LCR which applies to the whole industry or even the entire country (i.e. horizontally). Various LCRs in the area of public procurement have a very wide scope in the sense that they apply horizontally across all sectors as defined in their regulatory requirements. Depending on the product coverage, some LCRs cover large industries or even whole services sectors whilst others target specific sub-sectors. For instance, the US Buy American Act, or ARRA, has a wider reach so that infrastructure, education, health and renewable energy were included, but also has provisions aimed at the iron and steel industry.

LCRs in the Heavy Vehicles Sector in BRICS: An Application

To analyze and clarify the detrimental effect of LCRs, this report examines the case of LCRs applied in the heavy vehicles sector. It will do so with a particular focus on the BRICS economies, which are Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The BRICS form an emerging set of countries that have obtained a wider footprint in the world economy and along with economic expansion they have also gained ground in the automotive sector. The five countries together, for instance, now export domestic value-added in gross exports in automobiles that is around 7 percent of global value-added exports in this sector. As such, it has reached a slightly higher level than what Korea currently exports in terms of value-added in automotives.

An additional significant reason for choosing this set of countries is that the BRICS show a wide-spread use of LCRs. Figure 1.1 showed that many LCR measures currently implemented world-wide originate from the BRICS. Their LCR use takes up a share of around 44 percent of the total amount of LCRs this study finds globally. For the same reason, the automotive sector is chosen as a case study. The data in Figure 1.2 also showed that besides other sectors in which many LCRs are found, the automotive sector is responsible for 17 percent of all LCRs found across all countries in the world.[1]

ECIPE has collected all LCRs affecting the heavy vehicles industry for the BRICS countries and built a database where they can be found. This database is being used as a basis for this case study to assess the economic costs impact of LCRs on these countries. All LCRs in the database are recorded along the lines of the three dimensions of LCRs as found in Figure 2.1. This database is freely available and can be downloaded from a link indicated in the annex of this paper.

Figure 2.2: Types of LCRs, level of impact and scope in automotive sector in BRICS

Source: ECIPE

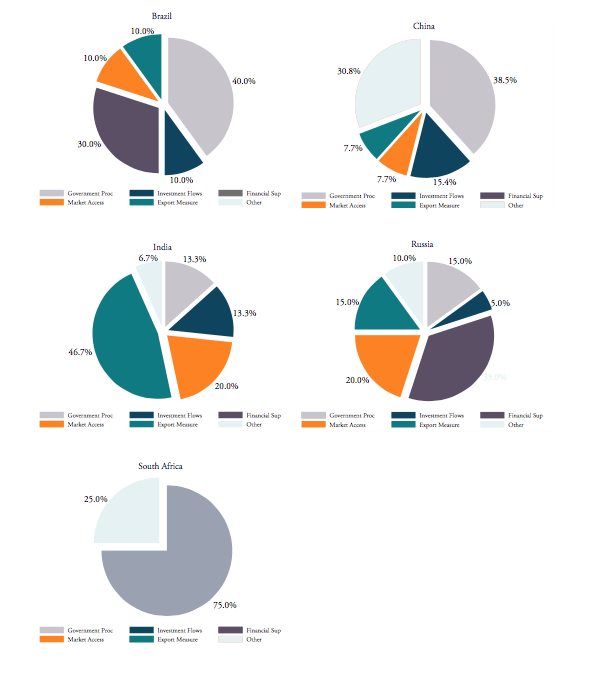

Figure 2.2 provides a first impression of the types of LCRs implemented by BRICS countries. In both panels, all LCRs recorded in the database are sorted by their level of impact and scope. The first panel shows the number of LCRs implemented by type and level of impact whereas the second panel shows the number of LCRs implemented by type and level of scope. The sectoral level in our case study is comprised of the entire motor vehicles sector whereas the sub-sector level represents the heavy vehicles sector only, which is a sub-set of the motor vehicle sector.[2] The size of the circles indicates the number of LCRs applied for each of the categories. The two panels show that the LCRs that apply in the five BRICS countries are present across all six types of LCRs as each category has at least more than one measure. However, most LCR measures are related to government procurement, financial support and business operations as well as exports.

However, the spread of these types of LCRs appears to differ along their levels of impact and scope. The panels show that most LCRs on government procurement are having a low impact, although there are many in place. In contrast, most LCR measures that relate to financial support and business operations as well as market access have a high impact. In addition, the second panel illustrates that most of the government procurement LCRs apply horizontally, which is also the case for many LCRs related to exports or market access. Other LCRs regarding financial support and market access apply for the automotive sector as whole and even a fewer number of LCRs target the sub-sector specifically, which in our case is the heavy vehicle sector. LCRs related to investments are less prevalent whilst market access LCRs do not target any specific item in the heavy vehicles sector.

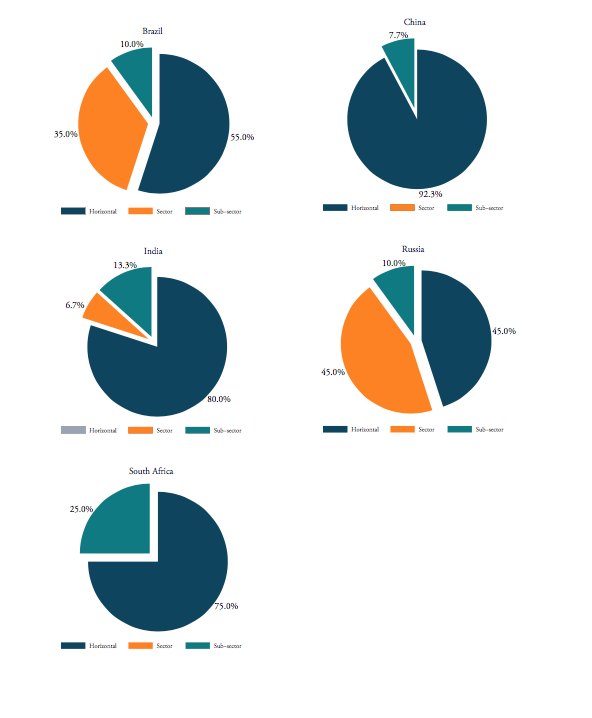

LCRs that affect the automotive industry are more or less equally spread across all BRICS countries, except for South Africa. Figure 2.3 provides the share division of LCRs for each BRICS country.[3] In total 72 different LCRs have been found which are all affecting the automotive sector in one way or another. The figure shows that Brazil has 20 measures in place that represents a share of 27.8 percent. Russia also has 20 measures in place and therefore has an equal share, followed by India with 15 measures which comes down to a share of 20.8 percent. China has 13 LCR measures in place and South Africa only applies a couple of LCR measures, namely 4, which respectively takes up a share of 18.1 percent and 5.6 percent.

Figure 2.3: Share (of number) of LCRs by BRICS affecting the automotive sector

Source: ECIPE LCR BRICS database

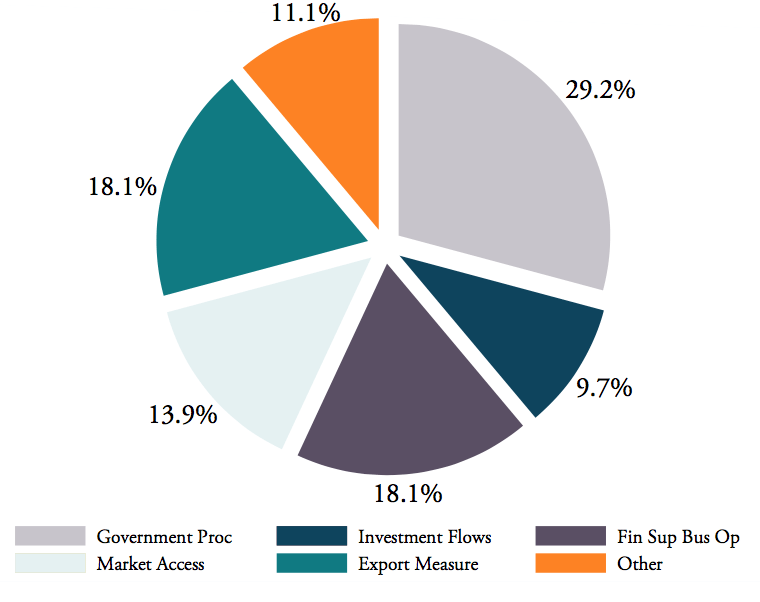

BRICS LCRs by Type

The split of the different types of LCRs is summarized in Figure 2.4. As said before, this figure makes clear that the LCRs are present in all sorts of forms. Most LCRs are related to government procurement and as such distort the flow of goods and services between importers and exporters. They come in different formats such as outright preference given to local producers as written in legislations to stating explicit preference margins in percentage shares for local industries. Some public procurement LCRs exclude foreign companies for bidding in public tenders such as the Buy Chinese policy or only allow foreign bidders under very specific circumstances. Second in line in Figure 2.4 come LCRs that are related to financial support as well as ones that cover export measures, each with equal shares. LCRs in this category, which also includes LCRs related to business operations, include many and cover for example state-supported preferential leasing schemes for the local car industry or “financial arrangements” given in China to local investors. LCRs related to market access are in a slight minority with a share of roughly 13.9 percent across all LCR measures found. This is an interesting observation in the sense that many LCRs found for our case study do not contain direct border measures and are classified as other than Market Access LCRs. Market access LCRs can refer e.g. to licensing requirements or tariff reductions conditional on the use of local inputs.

Figure 2.4: LCRs by type for BRICS

Source: ECIPE LCR BRICS database

The two final categories which have a slightly lower appearance in our database are those related to investment flows and other local content requirements. The latter category covers mainly data localization policies. One country that has both types of LCRs in place is China. China has a strong local content conditionality on the opening of its markets to foreign investments, but also shows various strict local requirements regarding data. Russia also holds strong data localization requirements. Across the BRICS countries, government procurement LCRs are the most popular types, except in India and Russia. In India, LCRs related to export measures are far more popular and almost half of all LCRs that India has implemented are related to this category. Russia’s LCRs are most likely to stipulate some form of financial support for companies. In both countries, market access LCRs are also prevalent. An overview can be found in Figure A1 in the Annex.

BRICS LCRs by Impact

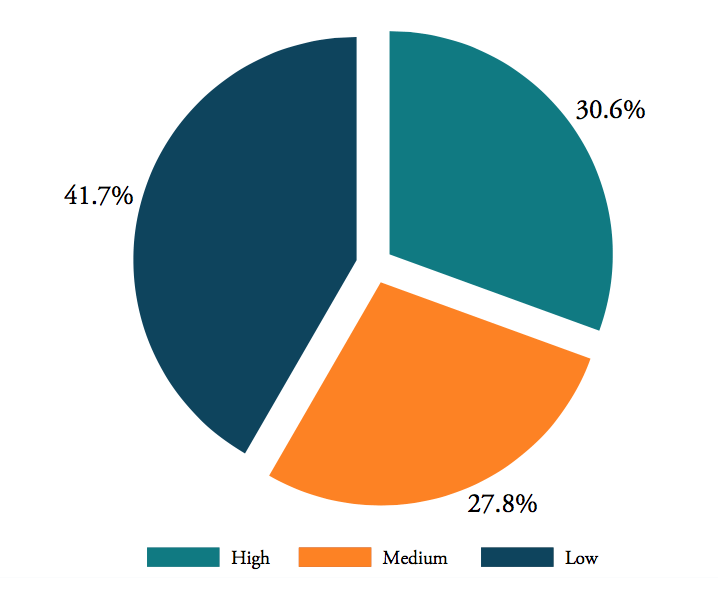

Figure 2.5 provides a summary of the LCRs by level of impact that apply across the BRICS countries. The level of impact ranges from low, medium to high and the assessment of the impact for each LCR measure has been done in close corporation with stakeholders from the automotive industry. Figure 2.5 shows that a slight majority of the LCRs have a low impact. The other two categories of medium and high impact are almost equally divided, with 30.6 percent of the measures having a high impact whereas almost 28 percent having a medium impact on trade.

Figure 2.5: LCRs by level of impact for BRICS affecting the automotive sector

Source: ECIPE LCR BRICS database

Looking at each BRICS country specifically, however, large variations arise. Figure A2 in the annex shows that proportionately Brazil, India and South Africa hold the biggest shares of LCRs with a low impact. Russia has the biggest share of LCR measures that qualified as having a highly distortive impact. Brazil and China both have a share of highly distortive LCR measures that is almost one third. These LCR measures range from the Buy Brazil Act which gives preferences to local products and services up to 25 percent as well as specific tax advantages for the equipment manufacturing industry in China. On the other hand, India only has less than a quarter of its LCRs that classify as having a high impact. Indeed, both India’s and South Africa’s set of LCRs are relatively more comprised of less distortive measures, i.e. which are assessed as having a low impact. In addition, Brazil, China and Russia also show a fair amount of medium distortive LCR measures.

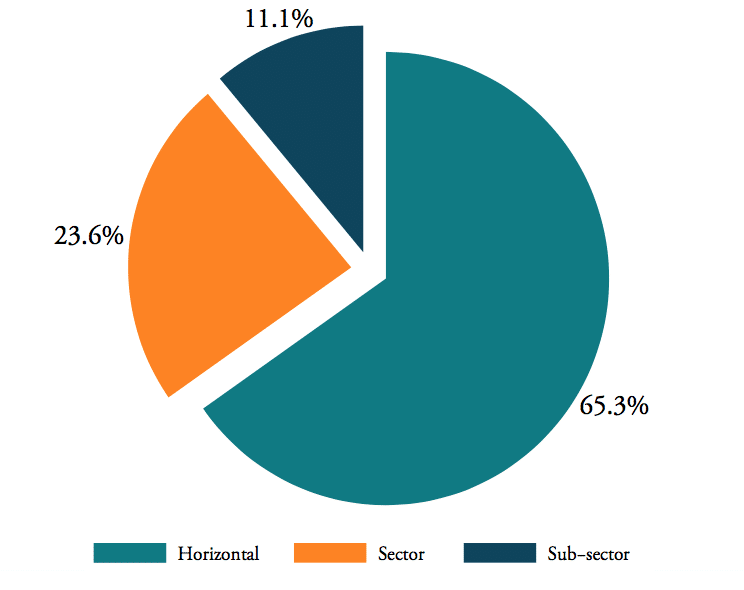

BRICS LCRs by Scope

The division of the third dimension of scope is outlined in Figure 2.6. It shows that most of the measures have an economy-wide reach in the sense that they affect all sectors in a BRICS country. There are about 47 of these measures in place. In addition, 17 LCRs target specifically the automotive sector at large which covers various sub-sectors such as overall motor vehicles and parts and components of this sector as well as the heavy vehicles sectors. Last, there is only a smaller amount of LCRs that target a sub-sector specifically, which in our case is the heavy vehicles sector.

Figure 2.6: LCRs by level of scope for BRICS affecting the automotive sector

Source: ECIPE LCR BRICS database

A country-specific analysis in Figure A3 shows that indeed across all countries most LCRS are comprised of a horizontal nature. In China, India and South Africa more than three thirds of the LCRs are applied on a horizontal level, while in Brazil more than half of the measures are horizontal and in Russia slightly less than half which are horizontal. These latter two emerging economies have a much higher share of LCRs which are specifically targeted at the automotive industry. Narrowing down to the specific sub-sector of heavy vehicles, our analysis also shows that all BRICS countries have LCR measures in place which specifically target the sub-sector of heavy vehicles.

Estimating the Impact of LCRs in the Heavy Vehicles Sector in BRICS Countries

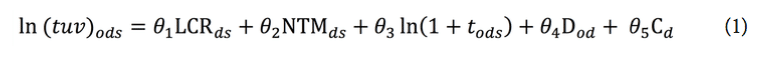

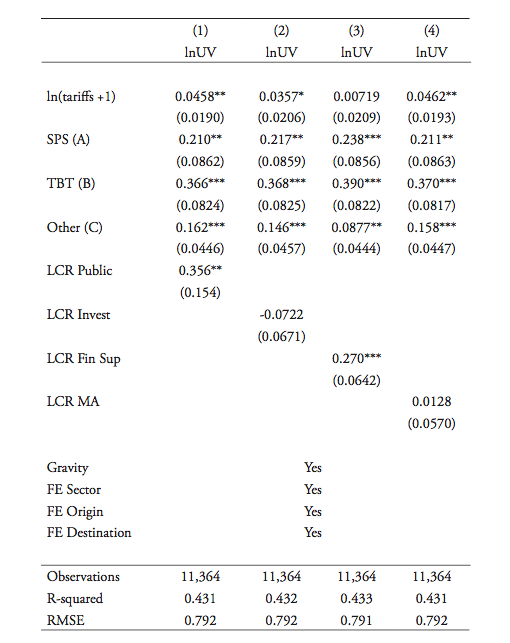

Estimating the cost of protection can be difficult, especially when the policy measures are not expressed in numerical terms like a tariff. This is the case with LCRs because they describe a policy requirement and they are not expressed in terms of tariffs. As a result, the negative impacts on trade and the economy as such are not always obvious. To examine the impact of LCRs on trade, we have translated their negative effects into a number which measures the price distortions resulting from the LCRs similar to the impacts of tariffs. This process of making an LCR numerical so as to measure their impact is called tariff equivalents, or ad valorem equivalents (AVEs). With the use of econometric techniques, we can therefore estimate the costs of protection resulting from non-tariff barriers such as LCRs, which can be compared with a tariff. Details on the way we estimate these AVEs can be found in Annex III. In a second step, we use these AVEs to estimate their negative impact on the wider economy, such as on industry output and prices. This second part is done through a so-called general equilibrium model.

In our analysis, we are specifically interested in the impact of LCRs in the heavy vehicles sector and aim to single out the negative effects of the LCRs we found for this particular sector. For the purpose of our analysis, the definition of the sector of heavy vehicles refers to the definition of the European Commission, according to which “heavy-duty vehicles” (HDV) comprise trucks, buses and coaches.[4]

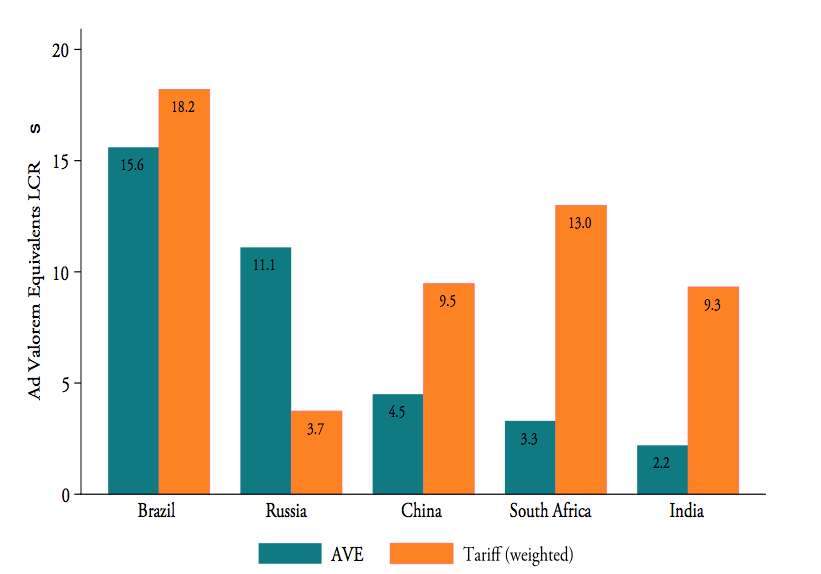

Our analysis finds that LCRs related to business operations and financial support as well as the ones covering government procurement have most significant cost-distorting effects for this sector. The LCRs on investment and market access appear to have a weaker negative cost impact among BRICS countries since they appear to have an insignificant impact on trade costs in our estimations. This could be explained by the fact that most LCRs related to market access are of a horizontal kind and therefore do not affect the heavy vehicle sector specifically. Similarly, LCRs related to investment are also mainly horizontally applied and are considered to have a rather low level of impact. Based on the results for the two types of LCRs with significant impact, we computed the tariff equivalents for each BRICS country which are shown in Figure 2.7. The figures show that Brazil and Russia apply the most distortive LCRs for heavy vehicles. The impact of their LCRs is estimated to increase the prices of imported goods by 15.6 and 11.1 percent in both countries respectively, i.e. the impact can be considered to be similar to an import tariff of that level. China and South Africa both show low AVEs. India has least distortive LCRs in place as it has the lowest AVEs. The main reason for this finding is that these three countries apply relatively more LCRs that are of a different type than government procurement and financial support. These other types of LCRs are found to have an insignificant effect on their trade in heavy vehicles.[5] Hence, the ad valorem equivalents for these countries remain modest.

Figure 2.7: Ad valorem equivalents LCRs and weighted tariffs for BRICS

Source: ECIPE calculations, based on ECIPE LCR BRICS database; WITS/UNCTAD TRAINS

Figure 2.7 provides an overview of the ad valorem equivalents of LCRs as well as the weighted average tariffs of BRICS countries in the heavy vehicle sector. It becomes clear that LCRs are indeed a significant barrier to trade in BRICS countries. In the case of Russia, they even by far surpass the protection level of tariffs. Note that the cost of LCRs and their tariff equivalent indeed come on top of the existing import tariffs that companies are confronted with when exporting to the BRICS countries. This illustrates the significance of LCRs as an impediment to international trade with the resulting negative spill-over effects for the economy and business that outlined above.

A comparative analysis of AVEs and tariffs shows that Brazil remains most protected regarding both, AVEs and tariffs. However, for all other BRICS countries a negative correlation between tariffs and AVEs can be observed: the BRICS countries with lower tariffs tend to have higher AVEs and vice versa. Accordingly, with the exception of Brazil, lower tariffs tend to go hand in hand with higher non-tariff barriers (reflected in high AVEs) and those BRICS countries with high tariffs use less LCRs to protect their markets (i.e. low AVEs).

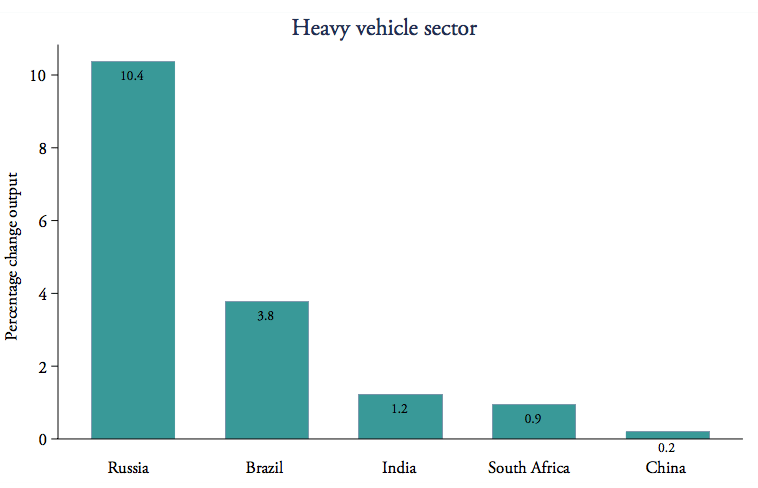

Impacts on Industry Output

Using simulations from the general equilibrium model, we provide an estimate of the impacts of LCRs for the heavy vehicles sector on the wider economy in BRICS countries. A detailed description of this methodology can be found in Annex III. The results for the heavy vehicle industry suggest that the applied LCRs provide an outcome that they were supposed to achieve: industry output in this sector increases in all BRICS countries. Figure 2.8 shows that the applied LCRs increase industry output of the heavy vehicles sector between 0.2 percent in China to even 10.4 percent in Russia. Brazil experiences an industry output increase of 3.8 percent. India and South Africa also have modest increases like China. Because LCRs require firms to source more domestic inputs for production domestically and most inputs are coming from the heavy vehicle sector itself, this result is in line with our expectations as it expands the activities of the domestic vehicle sector.

Figure 2.8: Industry output in heavy vehicle sector

Source: ECIPE estimations

However, this increased industry output in the heavy vehicle sector has to be put in perspective. It is natural that industry output that is subject to protection by LCRs increases, but at the same time this increase is outweighed by detrimental side effects. This is especially true for a price effect on the entire economy which has stronger consequences for the overall economy than the industry output gain in one sub-sector. As pointed out in chapter one and shown below, the side effects include negative impacts on the wider economy, consumers and trade. The impact of LCRs should therefore not be analyzed by looking at one particular sector in isolation, but by taking into account also their effects on trade, prices and other sectors.

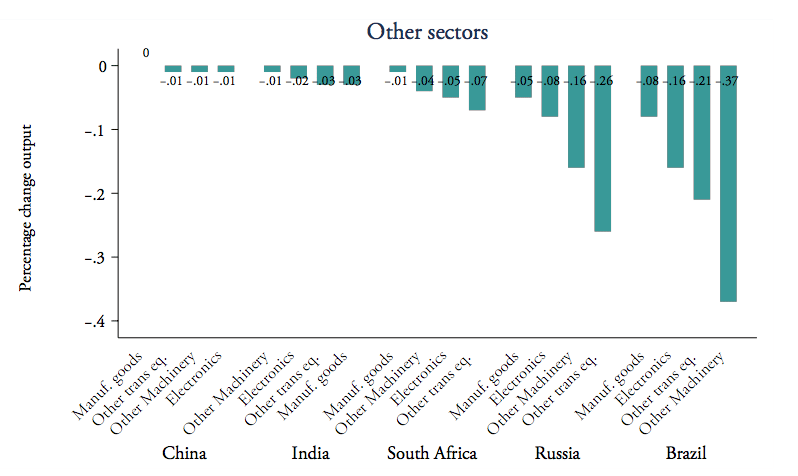

Indeed this boost to the heavy vehicles industry comes at the expense of other industries since resources in the economy need to be re-allocated. In fact, the expanding heavy vehicles industry needs more labour and capital, which is withdrawn from other sectors. Figure 2.9 shows that especially for some of the closely related sectors, which require similar production factors as the heavy vehicles sector, their output decreases because resources are taken away from their industries. This effect is particularly large in Brazil and Russia. Since both countries have the highest AVEs of 15.6 percent and 11.1 percent respectively, which therefore reduces their imports most, they also experience the biggest expansion of their domestic heavy vehicles industry, which in turn draws away many resources from these other sectors. More specifically, in Brazil and Russia the domestic production of other transport equipment decreases with respectively -0.21 and -0.26 percent and of other machinery with respectively -0.37 and -0.16 percent.

Figure 2.9: Industry output in selected other sectors

Source: ECIPE estimations

Impacts on Trade

Looking at the impact on trade, the results of our simulation show that LCRs not only reduce the imports in the affected sector, but also the exports of the heavy vehicles sector – although to a lesser extent.

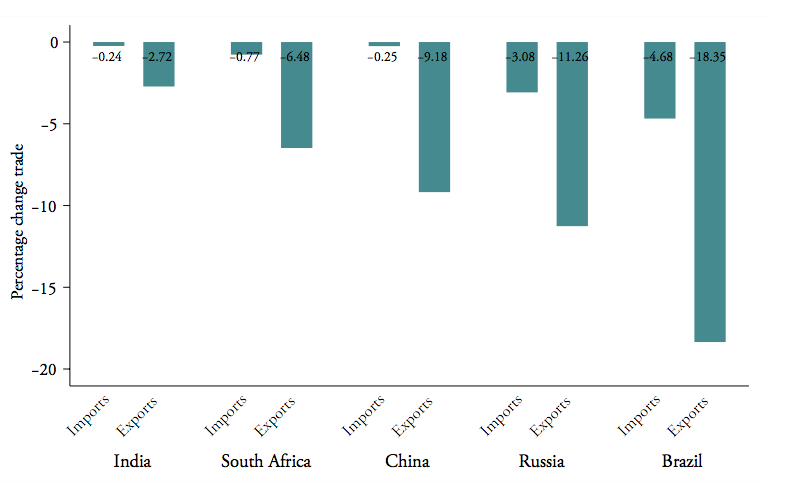

The two countries with the highest estimated AVEs, namely Brazil and Russia, also experience the greatest reduction in their imports and exports of motor vehicles as shown in Figure 2.10. On the one hand, imports in the heavy vehicles sector are significantly reduced due to the LCRs affecting the sector. The reduction of heavy vehicles imports for Brazil is 21 percent and for Russia 12 percent. Based on 2016 trade data this corresponds to approximately 1,731 and 1,121 million USD. For the other countries for which the impact of the LCRs is estimated to be less severe, the drop of imports is also estimated to be lower. In India, China and South Africa the estimated reduction of imports of heavy vehicles ranges between 3.7 percent and 9.3 percent. For China, the absolute value of import drop is, however, considerable with approximately 2,977 million USD.[6]

Furthermore, the LCRs also reduce the BRICS countries’ exports in the heavy vehicles sector, most likely because of the supply chain nature of this sector as well as because these countries become less competitive after implementation of the LCRs. Indeed, before BRICS countries are able to export their heavy vehicles, some of their industry output will be demanded by the domestic industry as they suffer from reduced imports in the first place because of the applied LCRs. In addition, our analysis shows that domestic firms cannot produce as effective anymore because intermediate goods in the sector become more expensive due to the LCRs (see also Figure 2.13 below.)

Figure 2.10: Impacts on heavy vehicles trade in BRICS

Source: ECIPE estimations

Again, Figure 2.10 shows that the greatest reduction in exports are found in the two countries with the largest impact of LCRs: Brazil and Russia. In Brazil exports of heavy vehicles are estimated to drop by 4.7 percent and in Russia by 3 percent. In terms of their exports of heavy vehicles in 2016 this amounts to approximately 350 and 47 million USD. For the other BRICS countries exports of heavy vehicles are estimated to drop between 0.9 percent and 1.8 percent. In terms of value, the impact is the highest for China for which the export reduction results in a loss of approximately 770 million USD.

If we look at bilateral trade between the BRICS countries and the European Union, the model estimates illustrate a similar pattern of heavy vehicles trade across the BRICS countries. Figure 2.11 shows the results. EU exports in heavy vehicles are reduced by 18.3 percent and 11.3 percent respectively with Brazil and Russia. Whereas, EU imports from these two countries are estimated to diminish by 4.7 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively. When translating these percentage changes into trade values using the year 2016, EU exports are reduced by 579 million USD to China, by 131 million USD to South Africa, and by 129 million USD to Russia. The total reduction in EU imports of heavy vehicles from BRICs countries amounts to approximately 288 million USD.

Figure 2.11: Impacts on EU trade with BRICS in heavy vehicles

Source: ECIPE estimations

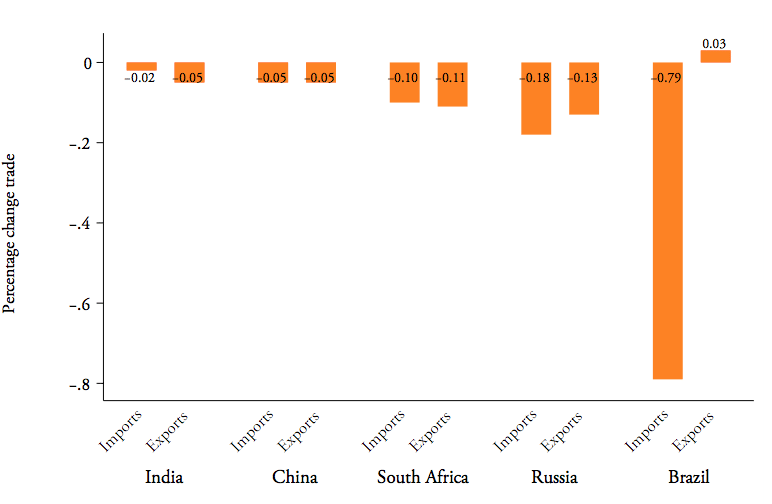

Beyond the trade impacts on the heavy vehicles sector itself, our results also show that the LCRs have a negative impact on trade in other sectors as well. More importantly, aggregate trade in terms of both exports and imports is affected in the BRICS countries as shown in Figure 2.12. The largest decrease of total imports is experienced in Brazil and Russia with a reduction of 0.79 percent and 0.18 percent respectively, whereas all countries except Brazil also experience a reduction of their total exports. Even though small, in some cases the reduction in exports is even larger than the drop of imports, which for instance is the case for India and South Africa.

Figure 2.12: Impacts of LCRs on total trade in BRICS

Source: ECIPE estimations

The decrease of trade in other sectors can be explained as well by the fact that the LCRs artificially inflate domestic production in the targeted sector, which also comes at the expense of other sectors, a conclusion which was also drawn by OECD (2016). As previously explained, if LCRs inflate the production in the heavy vehicles sector, other industries have fewer domestic resources left for their production. Since the industries also face higher prices for intermediate goods in the heavy vehicles and related sectors, they become less competitive and as a result are able to export less. For example, in all BRICS countries the passenger cars sector as well as the other transport equipment industry, which are closely linked to the production activities in the heavy vehicles sector, experience a reduction of exports of -2.2 percent and -0.4 percent, respectively.

Impacts on Prices

As explained, the LCRs also have an impact on the prices in the domestic market in the implementing countries. This affects all agents in the economy: the ones that consume heavy vehicles and their input parts and intermediates which are consumers as well as firms. An important point to consider here is that the price increase in this case merely results from import restricting measures by the LCRs, but it does not reflect better quality of goods or technological developments.

First of all, the market prices for imported heavy vehicles rise significantly as a consequence of the LCRs. The price impact for imported heavy vehicles is most significant in Brazil and Russia with an estimated increase of 13.7 percent and 9.7 percent, respectively. These results again reflect the high AVEs in these two countries. Since the impact of LCRs is lower in the heavy vehicles industry in China, India and South Africa, the price for imported heavy vehicles rises in these three countries only between 1.9 percent and 3.8 percent.

Second, these price effects carry on and also affect consumer prices as well as the prices paid by firms in the heavy vehicles industry for final and intermediate goods. Consumer prices for heavy vehicles are estimated to rise between 0.2 percent and 0.6 percent in China, India and South Africa, while they rise up to 2.4 percent and 5.4 percent in Brazil and Russia. Prices for intermediate goods paid by firms in the heavy vehicles sector are estimated to increase most in Russia and Brazil, with respectively a 2.9 percent and 4.8 percent rise. China, India and South Africa experience lower impacts and show a price increase for firms of respectively 0.2 percent, 0.5 percent and 0.7 percent. Again, this price increase for firms has a considerable impact on the competitiveness of the domestic firms operating in the heavy vehicles sector.

Figure 2.13: Impact on prices of heavy vehicles

Source: ECIPE estimations

[1] This excludes the category of Rest of World as LCRs for this geographical location are not available for the automotive sector. Therefore, in order for consistent comparison, this category is taken out.

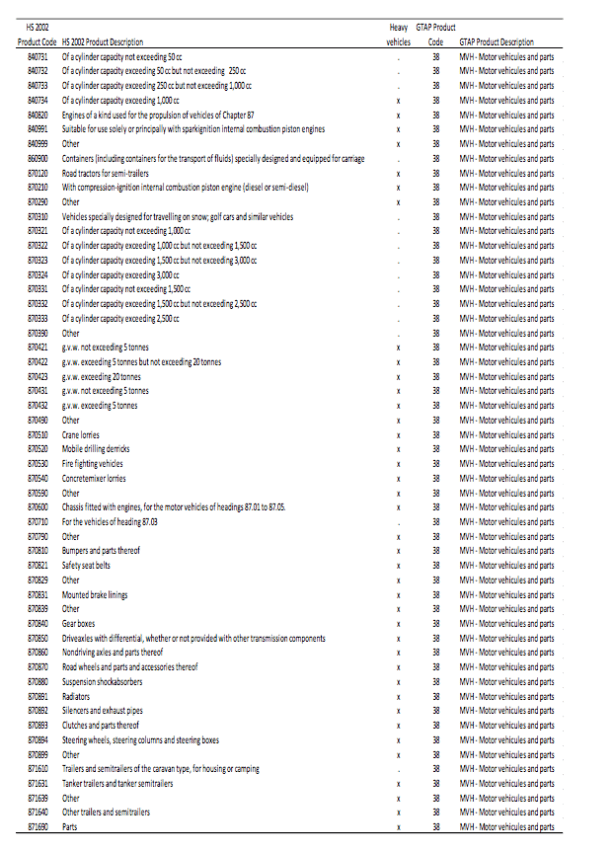

[2] Annex II outlines which specific HS 6-digit sectors are covered by automotive and heavy vehicles sectors.

[3] The LCRs are carefully collected in a database of which a link is put in the annex in order to consult online.

[4] HDVs are defined as freight vehicles of more than 3.5 tonnes (trucks) or passenger transport vehicles of more than 8 seats (buses and coaches). The HDV fleet is very heterogeneous, with vehicles that have different uses and drive cycles. Even trucks are segmented into several categories, including long-haul, regional delivery, urban delivery and construction, taken from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-14-366_en.htm. For further definition of the Heavy Vehicles sector and their corresponding industry classifications, see Annex II and III.

[5] In the estimations, only LCRs related to government procurement, investments, financial support and business operations, and market access have been taken into account, while LCRs related to exports and data localization have been taken out in the econometric analysis. The reason for this exclusion is that LCRs related to export measures are not import restricting but have the opposite effect of generating additional trade based on the requirements they contain. The decision of LCRs related to data localization is relatively novel and also seems remote for our sector.

[6] All calculations of trade values in this chapter are based on trade statistics from WITS/UN Comtrade for 2016 and the selection of HS codes as described in Annex II.

How to Address Local Content Requirements? A Menu of Policy Alternatives

Local Content Requirements have grown in frequency and consequence for the world economy, and as previous chapters have shown, they are more frequent in some sectors than others. Even if there are variations between countries, many countries are in fact using LCRs and the list of heavy users include countries of various levels of economic development and industrial profile. With the growing importance of the data-based economy, there has been a growth in the use of “localization measures” that, like the traditional forms of LCRs, forces those that trade to localize assets and output in a certain geographical territory.

The purpose behind the LCRs, however, is most often the same: to regulate trade and markets in a way that distorts competition. Countries that are heavy users may occasionally have legitimate reasons to demand a certain type of behavior on a foreign exporter, but the reality is that LCRs increasingly have been the go-to instrument for those that want companies to set aside their structure of production and value generation for the purpose of creating jobs in the destination country for the trade. The belief is that, if companies that export to a country are forced to invest there, the outcome will be much better in terms of jobs and growth.

We argue that this is simply untrue and there is no compelling evidence suggesting that LCRs improve on the growth potential for a country. On the contrary, a repeated number of studies have shown that measures like LCRs drive up cost for customers, depress consumption, discourage exports, and slow down technological change in sectors that are affected by them (see chapter 1). In the end, productivity growth is damaged, and a country prevents its citizens from enjoying the benefits that other people have. This study is no exception. Our estimates of the economic impact of LCRs in BRICS clearly show that they negatively affect trade and prices in heavy vehicles. Furthermore, they show that national output changes as a consequence of LCRs, with the effect of lowering total sectoral output even if, as expected, national output for the sector covered by LCRs goes up.

The growth of LCRs is also bad news for the world economy, because they clog the arteries of competition and trigger similar actions in other countries. The realistic expectation is that, unless checked and specifically addressed, the growth of LCRs will continue – and, if it does, these measures will surely have a significant impact on the capacity of economies to integrate with one another outside the sectors that are immediately covered by LCRs.

There are, however, reasons for optimism. There is new attention given to LCRs and concerns have been raised time and again at the WTO and in trade discussions among governments. Several business associations are raising attention about their damaging consequences. Furthermore, LCRs are given attention in bilateral trade talks. Unlike several other areas of rising protectionism, the growth of LCRs is on the agenda for many governments: they believe this issue needs to be addressed.

Behind this new interest is not just the growth of LCRs. They have also become the focus of attention because most countries are using LCRs or other forms of localization measures intended to tie assets or output to one particular territory. What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, and the use of LCRs by one country prompts or encourages others to do it, too. Therefore, if there is one misguided belief that has been corrected in many quarters in the past years, it is that LCRs are politically risk-free instruments that do not hurt the user, or that the user does not have to worry about a negative impact on them from other countries deploying LCRs or introducing other localization measures.

How can LCRs be addressed? In this chapter, we will look at alternative policy strategies for addressing LCRs. We will cover several strands of strategies.

Multilateral Options

The first option to consider is the use of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) – that affected countries will file complaints at the WTO with the purpose of getting a specific or a set of specific applied LCRs to be declared incompliant with WTO rules and, eventually, eliminated. The starting point for this option is the simple fact that LCRs in very many cases are incompliant with core rules of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and that they were specifically referenced as illegitimate measures in the Uruguay Round agreement on TRIMs.

Two core principles of GATT are that countries should apply national treatment in the way they treat foreign goods – meaning that the treatment accorded to local goods should also apply to foreign goods – and that governments should not apply any quantitative restriction of exporters. GATT Article III:5 states that it prohibits regulations concerning the “processing or use of products in specified amounts or proportions which requires, directly or indirectly, that any specified amount or proportion of any product which is the subject of the regulation must be supplied from domestic sources” (our italics).

The other set of WTO rules that is central for the legality of LCRs come from TRIMs. That agreement also embodies the principle of national treatment, which rules out the use of some LCRs when competing domestic goods are not under a mandatory instruction to invest a certain amount or certain type in a country. Moreover, this agreement specifically mentions LCRs and basically prohibits LCRs that mandate a specific percentage or quantitative target for local goods purchases by the exporter. In addition, it clearly prohibits LCR measures that have the intent of introducing a trade-balance requirement concerning the amount of goods that a company can import in view of the products that it exports.

These are the two key bodies of WTO rules (there are also other WTO agreements with possible relevance for LCRs, including GATT rules on State Trading Enterprises, the Government Procurement Agreement (a plurilateral agreement to which most BRICS countries have not acceded), and the agreement on subsidies). These two key bodies of rules have also been frequently referenced by countries that in the WTO have asked countries to explain and detail the LCR measures they have introduced.

Importantly, they have also been acknowledged by a WTO Panel – the first instance in a WTO dispute – in a case concerning India’s LCRs in solar panels (DS456). In this case, which was brought by the United States, the Panel found that India’s measures violated the national treatment principle in both GATT and TRIMs. Furthermore, the Panel argued that it is clearly the underlying assumption in these relevant WTO obligations that companies should be entitled to seek the most efficient intermediate goods on global markets and not be confined to just one local market. Also Brazil’s INOVAR AUTO program caused a dispute at the WTO due to a complaint made by the European Union on December 19th 2013 (WTO, 2017a). On July 2nd 2015 Japan also started a dispute settlement process on this topic as a complainant (WTO, 2017b). The WTO’s Dispute Settlement Panel published their ruling on the EU’s complaint August 30th 2017. The panel argues that several elements of the INOVAR AUTO program grant unfair tax advantages and subsidies to domestic goods and production processes, to the detriment of imports and foreign manufacturers. The Appellate Body is currently reviewing the case (WTO, 2017a) (see chapter 1).

Filing more complaints to the WTO is important in order to establish more jurisprudence that covers a wider set of LCRs. Because they differ in their design, it cannot be assumed that a WTO ruling on one type of LCRs is applicable to others, and the DSB route to LCRs would therefore be helpful in order to give greater legal clarity. It cannot be assumed, however, that a greater number of complaints would have a systemic impact on the use of LCRs. A dispute in the WTO will only cover the referenced measures in the complaints. Countries that use them may also come to the conclusion that, from a practical point of view, they can continue to use them as long as no country takes them to the WTO. A dispute-settlement process takes time and, while it is ongoing, affected goods and companies still have to comply with the measure. When a ruling comes, it is often too late to change the specific arrangements that a company applied to be in compliance with the measure.

WTO members make their own analysis of whether it is justified to seek dispute-settlement in the WTO, and their judgement is often based on the economic value of the measure that affects their exporters. What should be important for future complaints is to complement that “economic test” of whether a country should file a complaint or not with a few other guiding principles. Some LCRs are more damaging than others, and a first guiding principle could be that countries file complaints in cases of LCR escalation. A second guiding principle could be that new LCR-based complaints should take aim at practices based on distorting the value chain with the view of demanding localization of the parts of the production which represents the highest value, including research and development, technology generation, and intellectual property. A set of complaints in these areas would be helpful for the routine discussions in the WTO about the notification of measures, and would add more power to the attempt to prevent countries from introducing LCRs in the first place. A further area would thus relate to the notification procedure, which means clearer obligations for all countries to notify to other countries when they are introducing a measure involving a localization requirement. Such a notification should allow time for other countries to evaluate the proposed measure and respond to it.

A second multilateral option is to start negotiations in the WTO with the view of clarifying what current rules entail for governments using LCRs and, hopefully, get stronger negative rules against their use. That may prove difficult because there are some WTO members that are intensive users of LCRs and believe they are central to their industrial policy. Still, there is a growing awareness in most quarters that LCRs, in the first place, have been damaging to the country that introduced them and that they are already facing (or are at risk of facing) similar measures being applied on their exports.

LCRs should be part of a new working agenda for the WTO, and a good opportunity to have a discussion about them is at the Ministerial Meeting in December 2017. It remains to be seen to what extent there is an interest on the part of the membership to set an agenda that involves such negotiations, but it should be obvious to any observer that, given world trade policy developments, there is an urgent need to reactivate the WTO and to get the focus on real and practical problems in the world of trade.

Thirdly, if the entire membership is not willing to engage in negotiations to clarify rules and make them stronger, a group of countries can do that in a “coalition of the willing”. That coalition can work through the Geneva missions of WTO members. It can also be formed in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), whose members have expressed much stronger concerns about the growth and use of LCRs. The work agenda for such a coalition, or for the entire WTO membership, would first be to shed more light on LCRs through analysis, databases and other activities that help to build knowledge and transparency.

Like in work related to State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), it would be important to build a larger body of economic analysis of LCRs, with the view of getting them more manageable. An instructing example is the work done in the OECD to establish rules on competitive neutrality for SOEs. Drawing on more and better economic analysis provided by the OECD Secretariat, members started to formulate principles that aimed at restricting practices that were distorting to competition. All participating countries had an interest to restrict the practices of their own SOEs because they had firms that were damaged by the practices of other countries’ SOEs.

The “coalition of the willing” could then set up their own accord with stronger and negative rules on LCRs. A separate accord can be done plurilaterally and on the basis of reciprocity: only participating members in the accord are entitled to participate in the discussion and are only obliged to practice the new negative rule vis-à-vis other participating members. In that regard, the accord could follow the example of the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), a plurilateral agreement that only applies to its 19 participating members.

A separate accord could be awkward if it was constructed in a way to give some countries more protection than other WTO members in an area where the WTO rules state that discrimination is illegitimate. The specific rules and obligations of the accord have to be carefully constructed and set in a context that would not be discriminatory. There are two sources of inspiration for how that could be done. First, many WTO members have signed Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) or International Investment Agreements (IIAs) that are already used to resolve disputes between states and between an investor and a state. Second, in the proposed Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) in the OECD, negotiated in the 1990s but never ratified due to intensive NGO campaigning against it, members began to make clarifications to what TRIMS that were not allowed, and those went beyond the TRIMs agreement in the WTO.

Bilateral Options

The second option to consider for how to address LCRs is based on bilateral agreements. Most leading economies in the world take part in bilateral and regional efforts to establish preferential trade agreements, and they are opportunities to get clarification of rules concerning LCRs, especially in those sectors where such measures are frequently used. The EU, for instance, is negotiating with a large set of countries in the world. It is in the process of ratifying trade agreements with Canada and Singapore, and it is negotiating with several governments in the Asia-Pacific region and Mercosur. It has also started negotiations with India, even if these negotiations have been dormant for several years. The EU is also involved in negotiations over a new Bilateral Investment Treaty with China, which also includes a significant component concerning market access for investment. In other words, the EU already has negotiations with most of the key countries covered in our estimates – and the countries that tend to be the heaviest users of LCRs.

The EU already addresses LCRs in its bilateral trade agreements. Just like in other areas, these agreements are based on WTO rules – and, in principle, thus include the basic GATT and TRIMs rules on national treatment. Furthermore, the EU also addresses specific areas of LCRs in its Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). For instance, in the EU-Singapore agreement there is a specific chapter on non-tariff barriers to trade and investment in the renewable energy generation that specifically addresses LCRs. The agreement states in Article 7:4 that:

“A Party shall:

(a) refrain from adopting measures providing for local content requirements or any other offset affecting the other Party`s products, service suppliers, investors or investments.

(b) refrain from adopting measures requiring the formation of partnerships with local companies, unless such partnerships are deemed necessary for technical reasons and the Party can demonstrate such technical reasons upon request by the other Party;”

Likewise, specific approaches on sectoral rules on LCRs can also be found in the EU-Canada agreement. In this case, they concern rules on government procurement in the transport sector. Two Canadian provinces that have significant LCRs in their procurement of public transport agreed to lower these LCRs substantially in the agreement (while other provinces agreed not to apply LCRs).