The Cost of Fiscal Unilateralism: Potential Retaliation Against the EU Digital Services Tax (DST)

Published By: Hosuk Lee-Makiyama

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union

Summary

The EU is proposing a digital services tax (DST) to tax certain so-called ‘digital companies’, which it alleges access the Single Market while paying ‘minimal amounts of tax to our treasuries’. But like all exporters, these firms pay the majority of their taxes where their product development takes place, and services are designed and implemented.

The EU has singled out certain revenue streams, as it claims they have a high reliance on intangibles and user-generated value. Also, the proposal arbitrarily sets the thresholds in such a manner that it effectively singles out exporters from two countries – the United States and China.

The DST would be based on gross revenue and would thereby be deprived of deducting operational expenditure and write-offs unlike the rest of the economy who are only subject to tax on net profits, resulting in inevitable double taxation. They are also deemed to have a taxable nexus inside the EU, even when they are actually exporting their services from abroad.

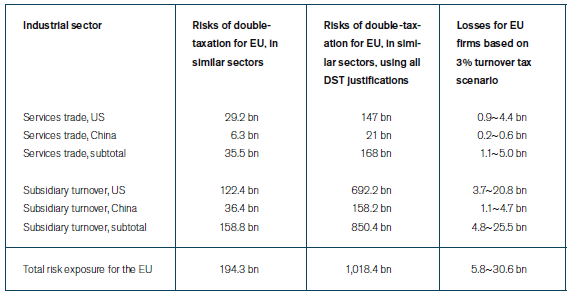

This paper argues that reciprocal treatment by the US and China against the EU based on the same selection principles against EU services exports and subsidiaries could subject up to EUR 1,018.4 bn in gross turnover to taxation. A turnover tax of 3% could amount to EUR 31 bn – by far exceeding the EUR 4.7 bn the European Commission claims to collect from the DST. Also, nothing precludes the United States and China from a tax against Europe that is higher than 3%.

From the perspective of trade law, the DST is also an indirect tax on services imports and is effectively a customs duty. The EU is committed to market access and national treatment on digital services and must prove that the DST (and particularly its quantitative thresholds) are not arbitrarily set to discriminate imported online services. The WTO e-commerce moratorium also prohibits such customs duties.

In conclusion, any changes in international tax principles must be universally agreed on mutually acceptable terms at a global level with those countries whose exporters the EU are aiming to tax.

The author gratefully acknowledges the able research assistance of Cristina Rujan

Background

The EU has set its sights on taxing certain revenue streams of digital companies, as it claims that they earn profits in Europe, allegedly ‘paying minimal amounts of tax to our treasuries’.[1] The proposed EU Digital Services Tax (hereafter DST) would uniquely collect taxes based on gross revenues (rather than profits) of online intermediation providers, internet advertising and sale of user data, which is over a carefully chosen ringfence, singling out a handful of Chinese and US online e-commerce services.

Europe’s decision is guided by a number of misconceptions, assuming that internet commerce takes place in a lawless no man’s land, while online actors are subject to overlapping and contradictory rules as governments seek to extend their jurisdictions extraterritorially.[2] The European Commission cites a study to support its claim that digital business models pay just 9.5% in corporate income taxes.[3] However, the Commission’s claim – as well as the DST concept itself – has been publicly refuted by the author of the study.[4]

In addition, online and digital enterprises pay an effective tax rate which is similar to or even above that paid by traditional industries.[5] This is the consequence of US statutory tax rates being historically one of the highest in the OECD prior to the recent US tax reforms.[6] The US rates are now largely similar to the rates in the EU.[7]

Thus, the actual question is not whether they pay taxes, but where they are paid. It is a zero-sum game between countries that seek to claim a bigger share of corporate revenues as their tax base, at the expense of other governments. According to agreed international frameworks, corporate taxes are paid where there is a ‘nexus’, i.e. in accordance with the functions performed, assets owned, and risks assumed by that entity.[8] For instance, European multinationals tend to centralise their production in the EU and export overseas.[9] Therefore, the EU businesses pay the majority of their income taxes at home, rather than in their export markets.

Digital services (which includes intermediation of goods) are not different from other services in this regard. These companies tend to pay taxes where their product development takes place, and services are designed and implemented. One might argue that digital enterprises do not differ from the way European businesses in the auto industry, pharmaceutical, financial services, retail and franchise chains operate.

The background documents of the European Commission suggest a DST at 3% would generate a fiscal revenue of EUR 4.7 bn,[10] assuming that the EU can take unilateral action without inciting responses from others. But the EU does not act in a vacuum. By arbitrarily and unilaterally changing tax principles on foreign businesses who trade with Europe, the EU inevitably exposes itself to the risk of retaliation. The affected countries – notably the United States and China – could act against EU exports and investments by merely applying the same logic used to justify Europe’s own unilateral action.

This paper exemplifies the scale of such potential retaliation based on the same principles that the EU invoked that are contextualised in the following sections. Its conclusion argues that any changes to the international tax principles must be universally agreed at a global level, on mutually acceptable terms, with those countries whose exporters the EU are aiming to tax.

[1] A letter to the Estonian EU Presidency of the EU and the European Commission from the finance ministers of France, Germany, Italy and Spain, as reported in EU Observer, EU big four push to tax internet giants, 11 September 2017, accessed at: https://euobserver.com/economic/138954

[2] De la Chapelle, Fehlinger, Jurisdiction on the internet, Internet & Jurisdiction, April 2017, accessed at https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/gcig_no28_web.pdf

[3] Supporting on consulting report commissioned by European Commission, DG TAXUD, ZEW (2017), ‘Effective tax rates in an enlarged European Union’ – Final report 2016, Project for the European Commission, TAXUD/2013/CC/120

[4] See Question for written answer to the European Commission (E-005509-18) by MEP Wolf Klintz, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document//E-8-2018-005509_EN.html; ZEW, An EU Digital Tax Places an Unnecessary Additional Burden on Firms and Cannot Be in the Interest of Germany, 10 September 2018, accessed at: https://www.zew.de/en/presse/pressearchiv/eine-digitalsteuer-fuer-europa-belastet-unternehmen-unnoetig-mehr-und-ist-nicht-im-interesse-deutschlands/

[5] See Lee-Makiyama, OECD BEPS: reconciling global trade, taxation principles and the digital economy, ECIPE, 04/2014; Lee-Makiyama, Ferracane, The geopolitics of online taxation in Asia-Pacific – Digitalisation, corporate tax base and the role of governments, ECIPE, 01/2018; Bauer, Digital companies and their fair share of taxes: Myths and misconceptions, ECIPE, 03/2018

[6] US Congress, Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, 115-97

[7] Recent US tax reform lower the corporate tax (including average state and local taxes) to 27% which is also the EU average. See Ekins, Gavin, Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Puts the U.S. with its International Peers Tax Foundation, accessed at: https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-corporate-tax-rate/

[8] OECD, Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, OECD, 2013

[9] The export dependency of EU Member States (as percent of GDP) is higher than e.g. China and United States. See EU Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment, EU-Japan EPA, LSE/European Commission, 2016; Bauer, Erixon, Ferracane, Lee-Makiyama, TPP: A challenge to Europe, ECIPE, 2014

[10] European Commission, Commission staff working document, Impact assessment accompanying the Proposal for a Council Directive on the common system of a digital services tax on revenues resulting from the provision of certain digital services, SWD 2018(81)final

The arbitrariness of the Digital Services Tax (DST)

The public debate on taxation of transnational business predates the internet by several decades, and hardly solved overnight. While the EU states it wishes to reach a global and sustainable tax model, which will be a challenging objective within a short timeframe. In the interim, the European Commission proposes in the interim to excise a tax on 3% of the revenues (instead of the universal principle of taxing just profits) on activities where:

- there is high reliance on IPRs and intangibles, or;

- the users are deemed to create a significant share of the value.

While such general criteria can be applied across a number of sectors, the Commission proposal singles out online advertising, multi-sided marketplaces (services that connect independent sellers and customers, or peer-to-peer activities) or business activities that relate to the use of user data. Furthermore, only companies with total annual worldwide revenues above EUR 750 million, and annual EU taxable revenues above EUR 50 million will be targeted, although there is no real justification of these thresholds.

The use of intangibles and IPRs

The background provided by the European Commission justifies the selective reversal of tax principles on the need ‘to prevent new tax loopholes emerging in the Single Market’.[1] But digital companies are hardly alone in using intangibles or where users contribute to the value creation.

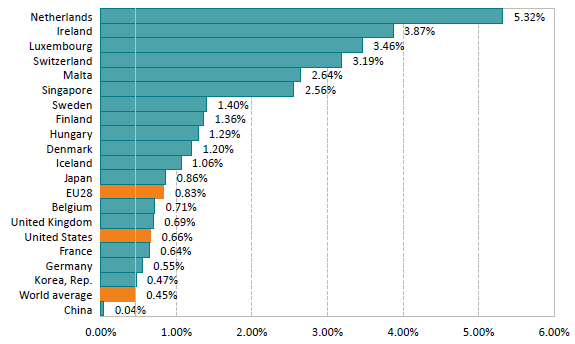

The use of intangibles – e.g. trademarks, databases, customer contracts, royalties, software, content –[2] are a common feature in sectors where the R&D cost or branding expenditure is naturally high. Such is the case in sectors like pharmaceuticals, media, apparel, telecoms, business services, or food and beverages (Figure 1) – and these are also the sectors where the EU dominates cross-border trade.

However, firm-level data shows how digital companies rely very little on their intangible assets (including IPRs) in relation to tangible assets.[3] The conclusion holds even when the value of goodwill (from numerous mergers and acquisitions in the industry) is included. The rest is just market expectations.

However, the European Commission’s Staff Working Document accompanying the DST proposal justifies the focus on digital services due to their high market capitalisation compared to booked equity values (P/B ratio).[4] While the Commission suggests the ratio could be an indicator of ‘relevance’ of IP, it is merely an indication of high valuation or market expectations. The causality between the two is diffuse at best: the markets don’t turn bullish because the firms increased their holding of IPRs.

Figure 1 —Internet firms have one of the lowest shares of intangibles, 2018

Source: Author’s calculations (based on Brand Finance 2018 GIFT survey of world’s publicly traded firms).

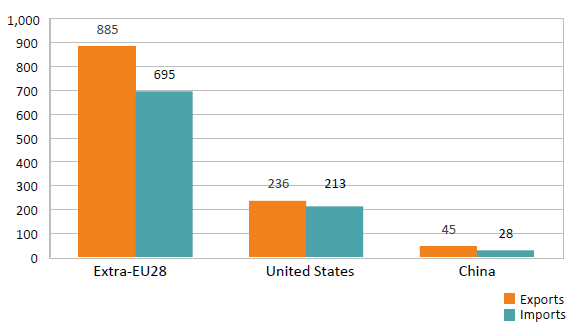

Also, most EU Member States have significantly higher revenues and dependencies from IPR receipts than the US at 0.83% of GDP, compared to 0.66% of US GDP (Figure 2).[5] The top three largest recipients of IPR revenues are also jurisdictions with well-known ‘IP-boxes’ in the past, with up to 5.3% of GDP in IPR receipts in the Netherlands.

Figure 2 — Revenue from the use of intellectual property (% of GDP), 2017

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank, 2017

User and customers contributing to value-creation

Clients contribute to value creation in many other service industries. While no precise metric exists on to what extent customers and clients contribute to the final product or service rendered in various industries, the ratio should be very high in all sectors where the degree of customisation is high, for business-to-business offerings like enterprise software, professional and consulting services. In the financial services sector (especially in customer-facing products like retail banking), the customers themselves perform an increasing share of the task of managing the capital they continue to own. By the same logic, certain analytical and data-driven services in the financial sector (e.g. the credit-rating business) are entirely based on exploiting user data.

In addition, advertising is a USD 73 billion industry in the big five EU economies alone, and despite two decades of digitalisation of media, the majority (61.3%) of the industry is attributed to traditional (i.e. non-digital) media.[6] Just like online advertising, traditional media set their rates based on the number of users they reach within a specific target group. The total number of viewers or readers are measured via surveys or audience measurement panels that monitor and track the consumption of thousands of households.[7] In particular, media that distributes free of charge to consumers – e.g. radio, must-carry TV channels or freesheets – are evidently creating their entire value from readers and viewers who are monetised through their use.

Selective turnover thresholds

There is no legal or economic rationale for these thresholds, especially as the EU is arguing the opposite – a removal of thresholds – in other fiscal policies. For example, the EU is arguing for the removal of de minimis thresholds in import duties.

Amongst the major media networks, RTL Group for example has digital revenue of EUR 826 million that exceeds the threshold.[8] However, these revenues are dispersed over a number of entirely unrelated sub-groups that engaged in entirely different activities and business models. Other media conglomerates run their businesses as franchises that are joint-ventures with different equity partners for each market. It is also a common practice that online advertising is bundled with traditional advertising, making it difficult to distinguish the revenues that should be subject to the DST.

Arbitrary discrimination against foreign firms

Only a few European firms would qualify for the DST amongst the largest internet companies[9]: Criteo (the French online advertising platform),[10] the Swedish streaming service Spotify (for its EU advertising revenue),[11] and one online fashion intermediary – Zalando,[12] while Asos and many other online resellers (who are non-intermediaries) could be outside the scope of the tax.[13]

Instead, the vast majority of the digital advertising and intermediary businesses within the definition and above the threshold are almost exclusively from two jurisdictions – namely China and the US.[14]

In sum, the EU is proposing a set of criteria that singles out foreign digital businesses for whom a turnover and destination-based principle should apply. By arbitrarily singling out these firms, digital services are:

- not deemed as trading – i.e. exporting from overseas – and instead always locally present and localised within the EU, at least from the perspective of corporate income tax, and;

- taxed on revenue and thereby deprived of deducting operational expenditure and write-offs unlike the rest of the economy.

Retaliation from the other countries could take the same two formats that are outlined in the following section.

[1] supra note 5

[2] Based on examples in the European international financial reporting standards, IFRS3

[3] Disclosed intangibles as a share of total assets, based on data collected by Brand Finance, Global Intangible Finance Tracker (GIFT) 2018 – an annual review of the world’s intangible value, October 2018

[4] supra note 5

[5] Receipts in USD; GDP, based on World Bank, World Development Indicators, World Bank, 2017

[6] eMarketer, Ad Spending in the EU-5: eMarketer’s Estimates for 2016–2021, 2017

[7] For example, in France, 4,300 households and 126,000 radio listeners are tracked by Mediamat; in Germany, 5,500 households are monitored by GfK. See, Meadel, Bourdon, Inside television audience measurement: deconstructing the ratings machine, 2011, accessed at: https://hal-mines-paristech.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01821830/document

[8] RTL Group, Annual report 2017, 2018

[9] Based on Fortune 500; Mary Meeker via MarketWatch accessed at: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/china-has-9-of-the-worlds-20-biggest-tech-companies-2018-05-31 ; The Economist, The biggest internet companies, 11 July 2014

[10] Based on 35% of their USD 2.3 billion global revenue being generated in the EU – see Criteo S.A., Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year 2017

[11] EUR 0.42 billion in annual revenue, based on 37% of users in Europe, see Recode, accessed at: https://www.recode.net/2018/2/28/17064460/spotify-ipo-charts-music-streaming-daniel-ek; also, Music Business Worldwide, accessed at: https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/if-spotifys-going-to-become-profitable-it-needs-to-make-some-changes/

[12] Taxed on its intermediation and not the retail business, see European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document, 26.4.2018 SWD(2018) 138 final

[13] Asos intermediation business (Marketplace) reported only GBP 2.1 million in revenue in the fiscal year 2017, accessed at: https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/07289272/filing-history

[14] The exception found is the e-retailer Rakuten that originates in Japan.

The risk of retaliation against EU services exports

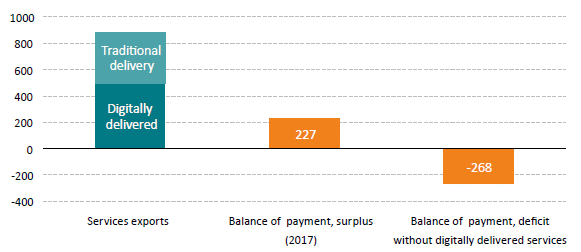

The EU advocates a change of global tax principles to destination-based taxation for digital services. However, the EU is the world’s largest exporter of cross-border services (i.e. directly to customers from overseas) at EUR 885 bn annually.[1] If the EU assumes EUR 4.7 billion in revenues from a 3% tariff, it must assume a turnover of EUR 157 billion to tax in the first place. EU services exports to abroad exceed that by a considerable margin.

As EU services exports to China and the US stand at EUR 281 bn,[2] and the two countries alone (or even the US administration alone) are in a position to impose retaliatory tariffs on services trade,[3] this would put Europe at a loss. As the world’s largest exporter of services, the EU is running a surplus of EUR 188 bn (that amounts to a substantial surplus margin of +21%).[4] The EU also runs surpluses against both the US and China, at EUR 23 bn and EUR 17 bn (10% and 38%) respectively.[5] Given the surplus, the EU will always be in a position where it has more to lose from a tit-for-tat cycle of retaliation.

Figure 3 — EU28 runs a significant surplus on services trade (billion €), 2017

Source: European Commission Eurostat, 2017

Europe’s large surplus also has a macroeconomic significance. The EUR 188 bn services surplus accounts for over 80% of the EU’s balance of payment,[6] the bottom line of all payments with the rest of the world in Europe’s chequebook. Also, much of these experts are also enabled by the internet and connectivity. About 56% of Europe’s services export – e.g. in retailing, banking, professional and engineering services – are dependent on digital services and intermediaries.[7] The EU would enter into a severe balance of payment deficit without online-delivered revenues (Figure 2), which amounts to a volume that is 3.5 times larger than the motor vehicle exports, Europe’s largest export industry.[8] The impact of retaliation could have a large-scale impact on economic stability and welfare.

Figure 4 — EU enters into a balance of payment deficit without digitally supported service (billion €)

Source: author’s calculations based on Eurostat, 2017; Nicholson, 2017.

Retaliation on services exports to the US

As the United States accounts for over a quarter (27%) of Europe’s services exports,[9] market access in the US is a considerable market access interest for all European multinationals. With EUR 236 bn of untaxed exports delivered cross-border (rather than via subsidiaries in the US),[10] there is a considerable amount of room for retaliation against EU commercial interests. The EU-US trading relationship is already fraught, with several long-standing trade disputes to the more recent unilateral tariff measures by the US administration. Also, in late 2017, the US Congress introduced one of the biggest overhauls of the tax codes in recent history.[11]

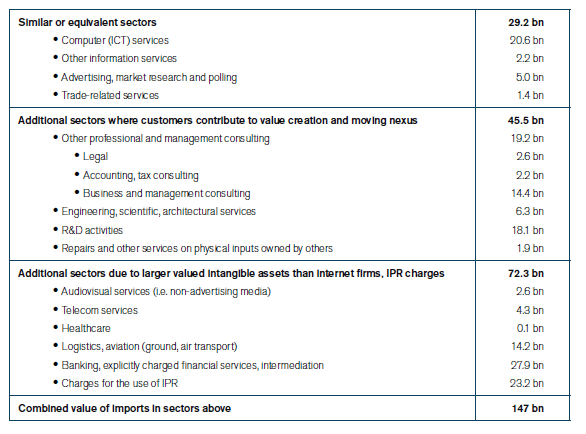

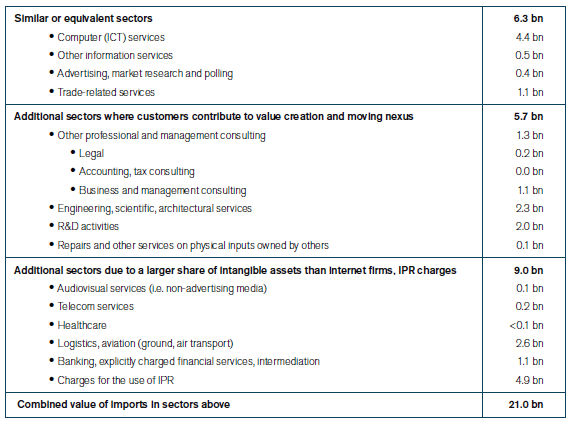

At least the sectors that are either identical or offline equivalent to the scope of EU DST should be in line for reciprocal treatment. IT and online information services, advertising, and trade-related services (where businesses act as intermediaries) have been singled out by the EU. The EU exports in these services amount to EUR 29 bn per year (Figure 5).[12] An import tax of 16% on this category alone would generate a fiscal loss that is equivalent to the EUR 4.7 billion that the EU envisaged raising from the DST.

Additional sectors fall into the scope of retaliatory measures by applying the same reasoning that the EU invokes to justify the DST: Firstly, by including sectors where customers contribute significantly to the value creation (i.e. professional, technical services and R&D), this would amount to exports worth EUR 45.5 bn annually.[13]

Secondly, several industries that have higher valued intangible assets than the internet companies in the services sector,[14] including audiovisual services (i.e. media services rather than advertising revenues), telecommunications, healthcare, logistics and banking. In total EUR 147 bn (or over 60% of EU services exports to the US) can be covered by the rationale used to argue for the DST.[15]

Taxing 3% the EU exports in the services sectors above to the US would create EUR 4.4 bn in costs. Combined with retaliation from China, the cost for EU services exporters exceed EUR 5 bn and the projected fiscal revenues of DST.

While the estimates on intangible-intensive trade only covers EU services exports, nothing precludes European manufacturing sectors that exploit intangibles (e.g. pharmaceuticals, food & beverages, apparel, cosmetics, etc.) to be captured by retaliation using the European Commission’s logic.

Figure 5 — EU services exports to the US at risk for retaliation based on the same principles as EU DST

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, 2016 (latest available disaggregated year)

Retaliation on services exports to China

China’s industrial policy strongly promotes its own internet economy, acknowledging its role in improving the country’s productivity.[16] Four of the ten largest internet and e-commerce businesses in the world (measured in revenue) are Chinese – namely JD.com, Tencent, Alibaba and Baidu – each with a global annual turnover that exceeds USD 10 billion.[17]

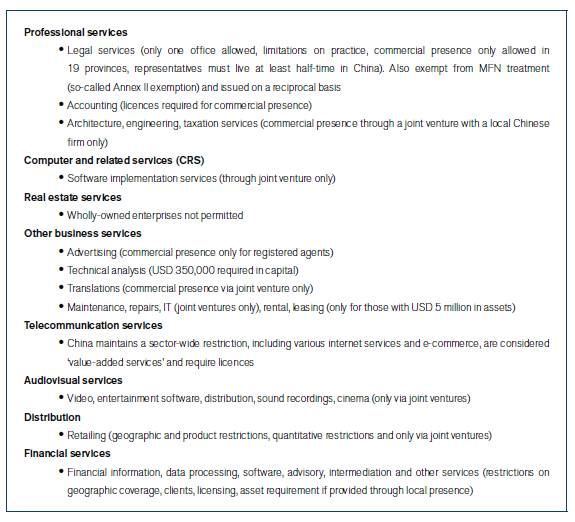

While Chinese legislation traditionally avoids extraterritorial application of its laws (including its corporate taxes), China is nonetheless in a position to protect its long-term interests in e-commerce. Its market restrictions on the digital economy are already the most comprehensive in the world,[18] and despite some recent liberalisation (e.g. lifting of FECs on e-commerce), market access restrictions support domestic e-commerce providers and encourage import substitution: China has already introduced consumption levies to disincentivise direct purchases from overseas merchants and e-commerce operators at between 15% and 60%.[19] Overseas sellers avoid these tariffs by choosing to localise their business inside China or deliver via ‘bonded imports’ where the ‘last mile’ takes place under Chinese jurisdiction.[20]

Aside from retaliatory taxation on the EUR 6.3 billion (Figure 6) of similar services (online, advertising and intermediary services), there are already calls for taxing business services such as ‘design, engineering, financial consultancy, advertising that are performed from remote locations’,[21] where the customers contribute with data or information to create value. China typically imports professional and technical services from Europe, which amounts to another EUR 5.7 bn per year, in addition to the sectors that are already similar to the scope of DST.

Finally, EU exports in intangible-intensive services sectors amount to additional EUR 9 bn. Taxing 3% the EU exports in the services sectors above to China would generate EUR 0.6 bn of costs for EU exporters. Combined with retaliation from the US, the cost on EU services exports exceed EUR 5 bn – and the projected fiscal revenues of DST.

As per above, nothing precludes European manufacturing sectors that exploit intangibles (e.g. pharmaceuticals, food & beverages, apparel, cosmetics, etc.) to be captured by retaliation using the European Commission’s logic. Chinese authorities are already monitoring European luxury brands due to the grey market trade,[22] corruption,[23] and undeclared profits by European subsidiaries.[24]

It should be noted that the Chinese authorities are already negatively disposed against European imports. Official Chinese policy actively encourages foreign direct investments (FDIs) and joint-ventures in services, recognising their ability to upgrade the economy.[25] While foreign participation in the services markets enhances China’s productivity, whether it takes place through investments or cross-border trade, the former leads to more technology transfer and creates new employment. Investments also add to the GDP, while imports negatively impact GDP.

Figure 6 — EU services exports to China at risk for retaliation based on the same principles as EU DST

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, 2016 (latest available disaggregated year)

Loss of market access due to shifting from cross-border to commercial presence

The internet and digitalisation have significantly reduced the cost of cross-border trading by making it possible to engage in overseas marketing, customer service and fulfilment via digital channels at low variable cost.

Obviously, the openness to serving customers remotely via the internet has significant policy implications. Trading is far less costly than establishing a physical branch across the world, which requires large-scale capital investment. In particular, the SMEs who were less prone to scale cross-border can now access overseas markets through online intermediaries.[26]

Whether services are provided remotely or are provided through local commercial presence has a significant bearing on international trade rules: Countries have different commitments on openness depending on sector and mode of delivery in either the World Trade Organization (WTO) or in bilateral trade agreements, in services schedules that determine whether certain sectors are open or closed to foreign participation.

The concept of digital PE – the idea that online services are locally present and having a taxable nexus – has some far-reaching consequences that would create a precedence, that could undermine European export strategy since most WTO Members are open to market access via cross-border trade (mode 1 and 2 in GATS terminology) but maintain several restrictions on commercial presence (mode 3).

For example, China (Figure 7) still applies (and retains the right to impose) joint-venture requirements or foreign equity caps (FECs) that limit foreign ownership to both majority or minority shareholding.[27] China and other countries also have fewer commitments on national treatment (i.e. non-discrimination once inside the market). In other words, there is not only the risk of being subjected to a tax or a tariff but admitting a PE could also lead to forced joint-ventures being stipulated as a condition for market access.

Figure 7 — Examples of sectors in China that are open for cross-border trade but closed for commercial presence

Source: P.R.C., Schedule of Specific Commitments, GATS/SC/135, WTO, 2002

[1] European Commission, Eurostat, 2017 (latest available year on aggregated level)

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

[6] ibid.

[7] Nicholson, J., ICT-Enabled Services Trade in the European Union, US Department of Commerce, ESA Issues brief, 3-2016.

[8] supra note 23

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] US Congress, Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, 115-97

[12] European Commission, Eurostat, 2016 (the latest available year for disaggregated data)

[13] ibid.

[14] See Figure 1

[15] supra note 33

[16] Ministry of Commerce (Mofcom), Notice Concerning Import Tax Policy on Cross-border Retail E-commerce, Cai Guan Shui [2016] No. 18, March 24, 2016. English translation accessed at: http://tax.mofcom.gov.cn/tax/ taxfront/en/article.jsp?c=30111&tn=1&id=faaaa90d546e4b4ba932682a924de247

[17] supra note 16

[18] Ferracane, Lee-Makiyama, China’s technology protectionism and its non-negotiable rationales, ECIPE, 2017, accessed at: https://ecipe.org/publications/chinas-technology-protectionism/

[19] Subject to temporary exemption until the end of 2018. A review of its extension is likely to take place before the end of its term.

[20] supra note 37

[21] Xu, Avi-Yonah, China and BEPS, The Laws Journal, January 24, 2018; ibidem, Evaluating BEPS: A Reconsideration of the Benefits Principle and Proposal for UN Oversight, Harvard Business Law Review 6, 2016

[22] Reuters, China’s Grey Luxury Market Threatened by New Tax Regime, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-luxury-greymarket-idUSKCN0WY528

[23] Reuters, Chinese slowdown fears hit LVMH shares and luxury rivals, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lvmh-results/chinese-slowdown-fears-hit-lvmh-shares-and-luxury-rivals-idUSKCN1MK0Q7

[24] See Figure 13 and its discussions

[25] State Council of PRC, Circular dated June 15, 2018, accessed at: http://english.gov.cn/policies/latest_releases/2018/06/15/content_281476186718808.htm

[26] eBay, Micro-multinationals, global consumers, and the WTO, 2013, accessed at: https://www.ebaymainstreet.com/sites/default/files/Micro-Multinationals_Global-Consumers_WTO_Report_1.pdf

[27] P.R.C., Schedule of Specific Commitments GATS/SC/135 with addendums, WTO, 2002

Impact of turnover based taxation

In addition to taxing traded services ‘at the border’ like a tariff, the DST taxes the affected entities based on gross revenues (i.e. turnover) rather than the profits. The likelihood of the US or China (or another host country of foreign investments) introducing a discriminatory scheme that taxes foreign affiliates (or just singling out EU-invested entities) may seem remote but given the unpredictable policy environment in both the US and China, there is no real reason why either of them would not be able to undertake fiscal reforms that even Europe is evidently capable of considering. US lawmakers have also warned the EU against taking unilateral action.[1]

Similar to its major surplus on services trade, the EU is also the world’s largest foreign investor with EUR 8.4 trillion worth of assets placed in direct investments abroad (Figure 8).[2] The EU has invested more in the rest of the world than vice versa by a considerable margin, leading to an outward stock that is 21% larger than the inward stock coming into the EU from abroad.

Given the relatively lower growth rates and returns in Europe, its business operations or capital management depend on foreign investments and subsidiaries that generate a turnover (hopefully at a profit) on markets with better growth prospects. Some of these profits are likely to be repatriated to the EU to fund new jobs or taxed as contributions to the social security systems at home.

Figure 8 — the EU28 is more dependent on being able to invest in the world than vice versa (€ bn)

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, BPM6, 2016 (latest data)

The two markets that the DST proposal singles out have a prominent role in EU overseas investment, especially in the United States, with some 40% of the EU assets overseas in either the US or China (Figure 9).[3] Moreover, 70% (EUR 5 trillion) of these investments are held by entities registered in the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Ireland (Figure 9),[4] despite accounting for just 7% of EU GDP,[5] due to the previously advantageous IP-boxes that are now phased out.

Figure 9 — EU investments and business activities were concentrated on the targeted countries in DST; investments took place via former IP boxes

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, BPM6, 2016; outward FATS, 2015 (latest available years)

However, FDIs are the booked values of EU investments (e.g. shops and factories) abroad. These investments are European foreign affiliates abroad that generate a turnover (i.e. sales) overseas of EUR 4.1 trillion per year, split evenly between manufacturing and services.[6]

The countries affected by DST – the United States and China – account for 48% of this turnover. Unlike service exports of the previous examples, this is a case where the production and value-creation indisputably take place abroad, in factories and points of sale within the US or China.

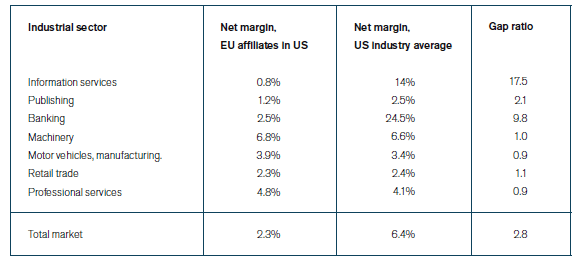

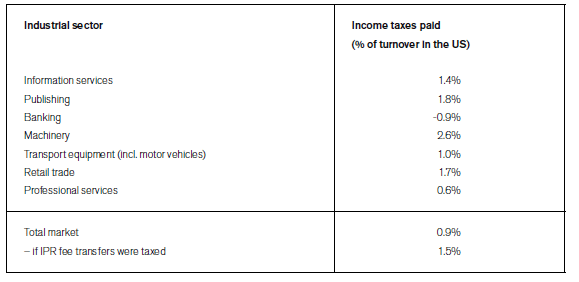

Turnover based taxation applied on EU affiliates in the US

With the EU subsidiaries (EU foreign affiliates) generating EUR 1.5 trillion in annual turnover, the United States is by far the most important overseas market for EU multinationals. However, the reported profits of the European affiliates were consistently low. According to the census of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, the affiliates that are controlled by EU interests filed a net income of approximately USD 42 bn over a turnover of USD 1.92 trillion.[7] The margins are 2.3% net, which is just one-third of the US industrial average of 6.4% the same year.[8]

Some sectoral comparisons show even more remarkable results. The EU-owned firms in sectors like professional services, retail, machinery and motor vehicles are generally in line with local US competitors,[9] while profits elsewhere seem suppressed. For example, the US industry average profits are 14% or 17.5 times higher than the EU-owned entities in information services.

S&P500 where information and technology services had a net margin of 16.1% the same year – which is 20 times larger than the EU-owned competition in the US). This gap is even more pronounced compared to the tech companies on the S&P 500 largest companies in the US.[10]

Figure 10 — Net income margins of firms in the US majority-owned by EU vs US industry averages

Sources: Own analysis based on US BEA, US affiliate activities – net income over sales, 2015; Damodaran, A., NYU Stern (based on 7,480 firms), FY2015.[11]

On the one hand, it should not be precluded that there might be structural reasons for this gap. To begin, doing business abroad is more difficult, especially in a highly competitive environment like the US. There may be some gaps in how an EU-owned firm operate compared to how their domestic counterpart firms operate. There may be differences between the product portfolios, where domestic incumbent services may focus on more profitable services than a foreign-owned competitor; or there may be differences in the quality or commercial acumen of their management.

On the other hand, EU-owned affiliates are multinationals with access to capital or with an unparalleled ability to scale and exploit their global resources. Also, establishment often takes place through acquisitions (where a foreign business buys the majority of an already established domestic firm). In addition, the EU-owned affiliates transferred EUR 23.2 bn in licensing fees for intangibles, where some are payments for licences that were issued to distinctly different firms.[12]

More importantly, the official BEA data also show that the EU-owned affiliates paid at most USD 18.1 bn in income taxes under the old tax code, which is just 0.9% of their turnover in the US (Figure 11).[13] Even if the IPR receipts were taxed in full at the nexus through phase-out of IP-boxes and GILTI provisions, EU majority-owned firms in the US only pay 1.5% of their turnover in US taxes.[14] In other words, if the US retaliated by singling out EU firms and forcing them to pay 3% of their turnover in income tax, their tax burden would at least double.

Figure 11 — Income tax paid by US subsidiaries majority-owned by EU firms, 2015

Sources: Own analysis based on US BEA, US affiliate activities – income tax over sales, 2015.[15]

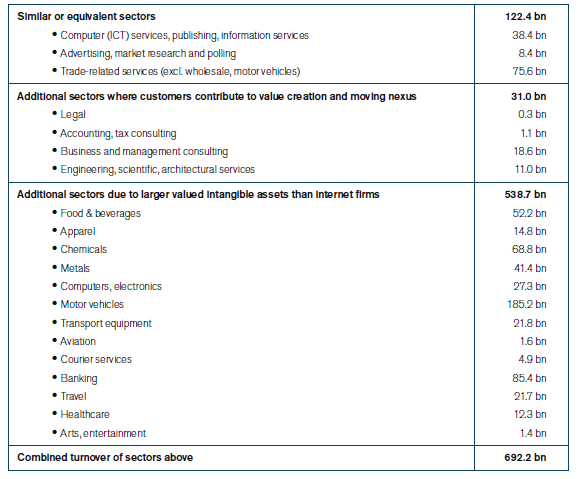

The turnover that would be the basis of such tax is at least EUR 122 bn per year (Figure 12) on corresponding sectors singled out in the DST alone. The scope could increase to EUR 692 bn on the grounds of the justifications the European Commission has chosen. Applying a turnover tax at 3% would generate a fiscal revenue of EUR 20.8 bn for the IRS (and an equivalent loss for EU businesses). This is in addition to the EUR 4.4 bn collected by the US from taxing EU services exports.

Unlike the previous example on services (where the US would reciprocate the EU DST by imposing a de facto tariff on services at the border), manufacturing sectors could be affected by a turnover tax. For example, the scope of the tax could cover the production of motor vehicles inside the US by European owners valued at EUR 185 bn. A turnover tax on cars would be in addition to the Section 232 tariffs that are currently considered on cars and car parts that are made in the EU and imported into the United States.[16]

Figure 12 — Turnover of foreign affiliates in the United States that are majority-owned by EU interests at risk for retaliation

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, 2015 (latest available disaggregated year)

Turnover based taxation applied on EU affiliates in China

The EU and the US are not the only jurisdictions who want to change the current order on corporate taxation. China perceives itself to be a victim of base erosion and profit shifting, going so far as stating officially in the UN how ‘it is obvious, that the major threat China faces is that many MNE groups [multinational enterprises] have shifted their profits by means of tax planning and transfer pricing’ –[17] and that the most common harmful practices are intra-firm transactions.[18]

However, the actual policy on the ground in China has been pragmatic. As a highly FDI-dependent economy, China’s industrial policy is focusing on redirecting foreign investments into more productive and innovative sectors to upgrade the economy.

China’s Ministry of Finance has started to offer preferential rates at 15% (compared to the 25% corporate income tax) for ‘high and new technology enterprises’ for both domestic and foreign-owned entities in direct response to the 2017 US tax reforms.[19] It has also announced that domestic Chinese firms repatriating overseas profits would be allowed deductions from taxes paid abroad from their taxable incomes,[20] and also temporarily exempted foreign investors from being taxed on profits if these proceeds were reinvested in prioritised sectors, e.g. technology and other R&D intensive sectors.[21]

In conclusion, it is reasonable to assume that China would not act against EU investment given that they are invested in ‘productive’ sectors, unless China was provoked first – and the EU DST is such a provocation.

To begin, several of China’s major e-commerce services and intermediaries fall within the scope of the DST proposal.[22] But many more Chinese start-ups are counting on scaling to other markets in the future, where Europe (due to national security restrictions elsewhere) may be the only high-end market open for them.

Moreover, it is essential to bear in mind that the DST is not just a provocation against private entities and entrepreneurs, but also against Chinese public finances. Central and provincial levels of the Chinese government have channelled over USD 300 bn of public funds into 780 different venture capital funds specialising in fintech and internet start-ups.[23] In conclusion, the international success of Chinese e-commerce is to some degree a matter of public finances, which is a core national interest – and DST is a hostile act against that interest.

As China generally guards its right to regulate (or tax) and avoids extraterritoriality of its rules, it is more likely to resort to fiscal policy over localised firms and production inside China rather than trade policy – if it chooses to retaliate. Also, China could make any future improvement on market access or full or majority ownership by foreign firms contingent on a turnover tax, or limited deductibility to ensure that the profits stay inside China to be either taxed or reinvested into its economy.

While there is no publicly available data on net income or corporate taxes currently paid by the EU-owned or controlled entities in China, it is reasonable to assume that the rate applied would be proportionate to the current and future damage inflicted upon China. As EU-invested firms generally operate at a loss in China,[24] a turnover tax at even modest rates would increase the fiscal burden on EU businesses.

One exception to the losses are in the luxury goods market. Nationally coordinated audits and industry analyses by the State Administration of Taxation (SAT) concludes that the profits of European luxury firms are prone to be suppressed,[25] especially given the higher propensity of Chinese consumers to buy luxury items. Therefore, China is very likely to respond to any provocation by issuing further ‘guidelines’ or crackdowns against European interests.

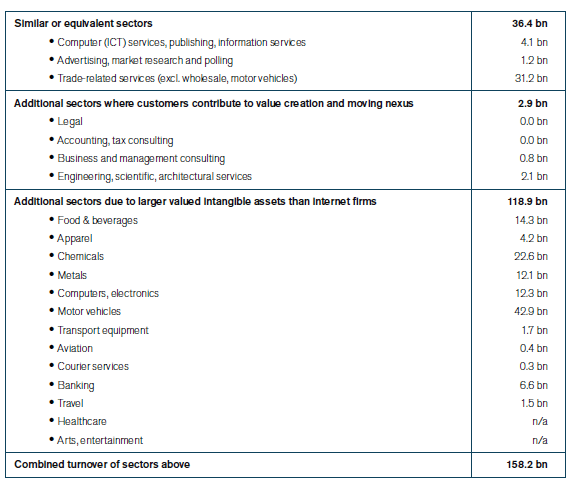

In total, EU firms generate EUR 158 bn per year in turnover (Figure 13) on sectors which are either similar to the sectors covered in the DST or could be attributed to one of its justifications. If a turnover tax at 3% were applied, it would generate EUR 4.7 bn in losses for EU subsidiaries in China. Combined with the EUR 20.8 bn collected from the EU subsidiaries in the US, the retaliation would amount to EUR 25.5 bn per year against the European subsidiaries on these two markets.

Figure 13 — Turnover of foreign affiliates in China controlled by EU interests at risk of retaliation

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, 2015 (latest available disaggregated year)

[1] US Treasury, Secretary Mnuchin Statement on Digital Economy Taxation Efforts, accessed at https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm534; Letter by US Senate Finance Committee signed by the senators Orrin Hatch and Ron Wyden, accessed at: https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/ 2018-10-18%20OGH%20RW%20to%20Juncker%20Tusk.pdf

[2] European Commission, Eurostat, BPM6, 2016, (latest available year, using the directional principle).

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] World Bank, World Development Indicators, World Bank, 2017

[6] European Commission, Eurostat, 2015 (latest available year)

[7] US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), U.S. Affiliate Activities: Preliminary 2015 Statistics, Majority-Owned Affiliates, 2015-2018

[8] Based on 7,480 firms. See Damodaran, Margins by Sector (US) 2015 financial year (dataset), NYU Stern, 2018

[9] ibid.

[10] Chen, The Most Profitable Industries in 2015, Forbes, 23 September 2015, accessed at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/liyanchen/2015/09/23/the-most-profitable-industries-in-2015/

[11] Data on publishing and motor vehicles are based on net income and turnover of firms majority-owned by European entities (including Switzerland)

[12] Some proportion of these transfers must be intra-firm transactions that were used to shift profits intra-firm in the past, that should be addressed through the new class of taxed income in the US tax code, the so-called global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI).

[13] supra note 52, based on income taxes paid by Europe excluding Switzerland.

[14] ibid. Based on 40% tax rate on the full amount remitted, using average USDEUR rate in 2015

[15] supra note 57 for retail trade, professional services. Remaining sectors are based on income taxes and sales by European (incl. Switzerland) firms due to non-disclosure of data by US BEA. The actual rate for EU firms should be marginally lower.

[16] U.S Department of Commerce, U.S. Department of Commerce Initiates Section 232 Investigation into Auto Imports, Wednesday, May 23, 2018

[17] P.R. China, China’s Reply to the BEPS Questionnaire of the UN Subcommittee, accessed online: http://www.un. org/esa/ffd/tax/Beps/CommentsChina_BEPS.pdf

[18] ibid.

[19] Ministry of Finance, the State Administration of Taxation, the Ministry of Science and Technology, Administrative Measures for Certification of High and New Technology Enterprises Circular, Circular 32, January 2016

[20] Zhang, New tax break makes it more attractive for Chinese companies to repatriate overseas profits, South China Morning Post, 3 January 2018

[21] ibid.

[22] supra note 16

[23] Oster, Chen, Inside China’s Historic $338 Billion Tech Startup Experiment, Bloomberg, 8 March 2016

[24] European Commission, Eurostat, Rate of returns on direct investment, 2016

[25] P.R. China, Transfer Pricing Opportunities and Challenges for Developing Countries in Post-BEPS Era, Twelfth Session of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, E/C.18/2016/CRP.2 Attachment 12, United Nations, 2016

Conclusion

While the European Commission envisages that a 3% DST would generate EUR 4.7 bn in fiscal revenue, retaliation from the United States and China on services trade could affect EUR 35.5~168 bn each year depending on which justifications they may claim. Also, EUR 158.8~850.4 bn of the turnover generated by EU subsidiaries in China and the United States will be taxed. A retaliatory turnover tax at 3% against EU services and subsidiaries would amount to at least EUR 5.8 bn and reach EUR 30.6 bn. It could be even more, as nothing precludes the retaliating countries to set a higher tax rate than 3%.

Figure 14 — Summary of retaliation scope

Sources: Own analysis

In addition, many countries who have no services exports or FDIs to the EU would have nothing to lose from imposing a tax on EU services or investments in their country. Notably, developing countries have shown a strong interest in the OECD BEPS process, but the digital economy is not necessarily the primary concern – at least compared to the general avoidance of PEs by EU and US multinationals.[1]

This is not to say that DST would make sense if the EU could generate a higher tax revenue than the retaliation. But these estimates reinforce the point that the EU and its Member States have more to lose from fiscal unilateralism. Hence, the EU should not try to diverge from the current international framework on corporate taxation without negotiating with all interested parties. The multilateral order is always a two-way street, even in a time when all roads of economic diplomacy seem to lead to Europe.

Similarly, for the United States and China, the objection against the DST should not be a matter of bottom line on tax revenues. There are plenty of reasons and objectives for these two countries (and others) to retaliate against EU plans.

First, it could be a simple matter of imposing retaliation to correct the EU’s behaviour due to the long-term interests in market access and keeping Europe’s digital economy open. At least for China, this objective is a stated core national interest.[2] Both retaliation and a WTO dispute are courses of action that would work towards this objective.

Second, the rest of the world should understand that there are much bigger issues and consequences at stake if the international framework breaks down. Regardless of whether a country is affected by the DST, the EU has set an example by threatening unilateral measures if the negotiations are concluded with an outcome and timeline that the EU has set. This is similar to how the EU itself retaliated (or ‘rebalanced’, in trade terminology) against US Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium,[3] as well as questioning the legality of US tariffs under the WTO rules. Ultimately, retaliating or litigating against EU DST creates costs that act as a backstop against further unilateral actions by the EU as well as others, and force the EU into a mutually acceptable negotiation.

Third and finally, the US, China and the rest of the world could impose retaliatory measures against Europe because it simply agrees with the principles of the DST – but other countries may have other defensive interests than digital services, that singles out the EU rather than Silicon Valley. This paper has clearly shown how the normative powers of Europe could backfire against its own commercial interests if the justifications and thresholds are too arbitrary.

[1] There was also overall concern about exclusion and transparency as non-OECD members, see Peters, C., Bulletin for International Taxation, IBFD, June/July 2015, accessed at: http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/11STM_G20OecdBeps.pdf

[2] supra note 40

[3] European Commission, EU adopts rebalancing measures in reaction to US steel and aluminium tariffs, 20 June 2018, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1868