The Compounding Effect of Tariffs on Medicines: Estimating the Real Cost of Emerging Markets’ Protectionism

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: Healthcare

Summary

Even low import tariff rates have a significant compounding effect on the final retail price of medicines, which in turn impacts on affordability. While much of the “access to affordable medicines” debate is about intellectual property rights (IPRs) and business practices of pharmaceutical manufacturers, import duties and national protectionism are swept under the political rug. In this paper, we provide a synopsis of tariff barriers for exports of pharmaceutical products to the world’s major low and middle income countries (BRICS-MINT countries).

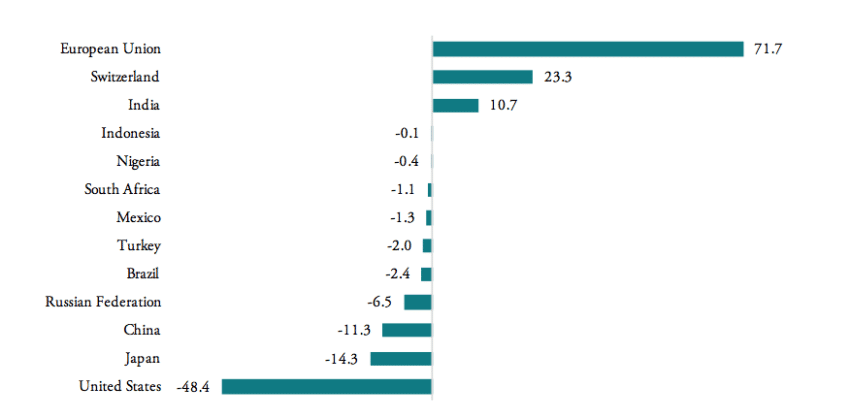

Studying the impact on final prices for consumers, we estimate that the annual compounded financial burden of import tariffs on pharmaceuticals and prevailing trade facilitation inefficiencies is highest for China (up to 6.2bn USD), Russia (up to 2.8bn USD), Brazil (up to 2.6bn USD) and India (737mn USD), followed by Mexico (663mn USD), Turkey (290mn USD), Indonesia (251mn USD), South Africa (177mn USD) and Nigeria (60,000 USD). For Brazil and India, tariffs on medicines increase their final price by up to 80 per cent of the original sales price ex factory. As most BRICS-MINT governments directly buy or settle patients’ invoices for a bulk of medicine products, the sum of all tariff-induced premiums on final prices for pharmaceuticals tends to exceed by far the tariff revenues initially collected by these governments’ customs authorities.

While import tariffs on medicines can cause substantial net losses for governments, taxpayers and patients, they effectively work as a subsidy for companies along national distribution chains. This may lead to a political economy, in which customs authorities and pharmaceutical distributors may have a common interest in maintaining (high) import tariffs. We call for all low and middle income countries to join the “zero for zero” pharmaceutical agreement, which would help to significantly cut the costs of medicines in general, reduce obscurity and absurdities in government spending and create better conditions for the access to medicines for low-income patients in these countries.

Research assistance by Julie Richert and Nicolas Botton is gratefully acknowledged.

Introduction

Tariffs are like Hydras: they create more problems than they solve. Tariffs on pharmaceutical products are a case in point. By levying import tariffs on pharmaceutical products, the governments of many low and middle income countries, including the world’s major low and middle income economies, explicitly aim to maintain a source of government income and at the same time protect domestic producers from foreign competition. However, by squeezing out financial rents from the import of much-needed medicine products, these governments impair the affordability of medicine products for low income patients in their countries. Unlike high-income countries, patients in low and middle income countries largely pay for medicines out of their own pockets and, in addition, suffer from a great number of inefficiencies along regional value chains for medicine products.

The right to health is well-founded in international law. It was declared a fundamental human right in the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1946, stating that “[t]he enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being […]” and that “[g]overnments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures.” (WHO 1946, p. 1; see also Sammut and Levine 2016 and Goel 2015).

While access to medicine is not a human right except in those countries which have specifically codified the right to health in their constitutions (mainly South American countries), it is regarded by the United Nations a fundamental element of the right to health and governments are obliged to develop national health legislation and policies to strengthen their national health systems. For this purpose, key issues related to access to medicines, such as affordability of essential medicines, procurement practices and supply chains, must be taken into account (OHCHR 2017).

Improving health equity is a major priority in global development policymaking. In international development cooperation frameworks, such as the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda that came into force in 2016, improvements in global health and, more specifically, “making essential medicines and vaccines affordable” has become a top-tier priority once again. According to the United Nations’ official announcements, policy areas to be addressed comprise research and development (R&D), intellectual property rights policies (IPRs), healthcare finance and improvements in the management of national and global health risks (UN 2015).

In line with these overarching objectives, the UN Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines recently called on private sector pharmaceutical companies to cooperate with governments, particularly in providing enhanced access to information regarding R&D costs, production costs, marketing and pricing practices and the distribution of healthcare products and technologies (UN 2016). There is, however, one fundamental piece that is missing in expert analyzes, policy discussions and the public debate about global health and access to medicines respectively: tariffs and taxation. Access to medicines is a also function of prices and affordability (WHO 2004), which are directly affected by national trade policies and regional taxation practices.

As concerns trade policy, the UN High Panel indeed acknowledges that “[t]rade and intellectual property rules were not developed with the goal of protecting the right to health, just as human rights doctrine does not primarily concern itself with promoting trade or reducing tariffs.” (UN 2016, p 16). At the same time, the Panel does not at all address frictions in the system that are caused by national trade policies, i.e. import duties (tariffs) and other protectionist policies, beyond matters related to the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). In other words, much of the “trade in medicines” debate is about intellectual property rights (IPRs) and, often, about putting the blame on pharmaceutical manufacturers, while tariffs and the quality of governance and taxation are swept under the political rug. As a result, and as will be shown below, many governments still unnecessarily, but substantially inflate the cost of medicines through import tariffs, taxation and other domestic regulations.

During the Uruguay Round negotiations (1989 to 1994), several major trading partners agreed to reciprocal tariff elimination, a “zero-for-zero initiative,” for pharmaceutical products and for chemical intermediates used in the production of pharmaceuticals. The “Pharmaceutical Tariff Elimination Agreement” was agreed by 22 countries (Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, European Communities, Japan, Norway, Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland, and the US) and entered into force on 1 January 1995. Due to the EU’s enlargement, there are now 34 signatories to the zero-for-zero pharmaceutical agreement, which enshrines a commitment to zero tariffs on medicine products that are imported from abroad and to not replace tariff barriers with non-tariff trade barriers. The treaty even extends to cover products imported from states not signatory to the zero-for-zero agreement including low and middle income countries.

Most developing countries are still net importers of pharmaceuticals, but many impose tariffs and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) on finished drugs, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), and excipients (inactive substances that contain the active ingredients). As shown by Banik and Stevens (2015), a larger proportion of globally marketed medicine products are now potentially subject to tariffs and other trade barriers, increasing upstream prices along the distribution chain of these medicines. Accordingly, the impact of import tariffs on pharmaceutical products gained in relative importance and adverse distortions of markets and consumer welfare increased significantly in absolute terms (see analysis below).

Compared to policies that aim to tackle local frictions in the distribution of medicines, such as a lack of education, high levels of corruption, lack of medical advisory capacities or the lack of domestic innovative capacities, the elimination of tariffs on pharmaceutical imports would be low hanging fruit. It would enhance access to medicine and contribute to the realization of the right to health in low and middle income countries. For various reasons, such as maintaining tariff revenues and the facilitation of contentious national industrial policies, low and middle income have not yet signed up to this agreement. Tariffs and NTBs, however, substantially contribute to pharmaceutical costs by increasing the final price of medicines, thus limiting access for the poorest people. As already outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2005, “[t]ariffs on medicines are essentially a regressive form of taxation since a smaller proportion of the payers’ income is affected by the tariff as income rises. This regressive ‘tax’ on medicines targets the poor and the sick.” (Olcay and Laing 2005, p. 2).

Aware of the necessity to build policy coherence and government accountability in trade and domestic healthcare policy, we start by providing a synopsis of trade and major barriers for exports of pharmaceutical products to the world’s major low and middle income countries, i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa (so-called BRICS countries), Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey (so-called MINT countries). In the subsequent part, we analyze how tariffs and inefficient customs procedures contribute to an inflation of prices of imported medicines. We aim to estimate the real size of border protection against medicines from abroad. We will show that nominal tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers are still high in many BRICS-MINT economies and that these barriers are significantly pushing up the price of medicines, increasing the initial percentage tariff surcharge by a high multiple. The estimations will be based on existing research and data sources, but will add new elements showing the real (and not just the nominal) size of the financial burden imposed on the consumers of imported medicines in BRICS-MINT countries. Based on our findings, we call for a new free trade accord that would help to substantially cut the costs of medicines in low and middle income countries in general and create better conditions for access to medicines for patients in these countries.

Patterns in BRICS-MINT Countries’ Trade in Pharmaceutical Products

In this Section, we provide an overview of trade and tariff data to get an understanding about the evolution and importance of trade in pharmaceuticals by country, the rate of nominal protection and how patterns in tariff protection differ between BRICS-MINT countries.

Patterns in Imports and Exports

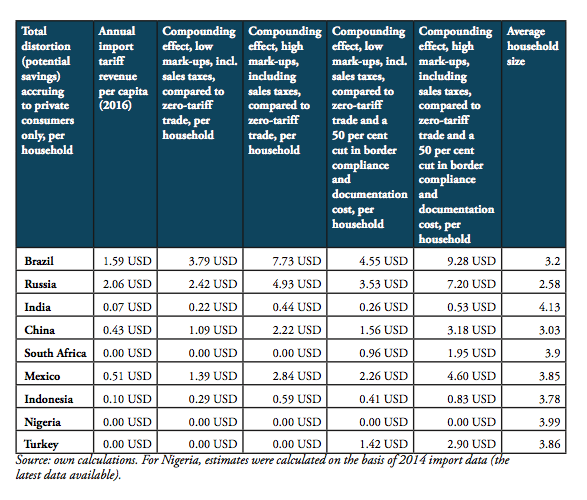

Since 2010, global trade in pharmaceutical products has stagnated, showing a relatively low aggregate growth rate of 1.3 per cent. While global trade volumes of products containing vitamins, penicillin, alkaloids and antibiotics generally decreased, global trade picked up for medicines containing hormones and insulin (see Table 1). At the same time, medicines “containing hormones” (HS 300439; 22bn USD in 2016) and medicines “containing other antibiotics” (HS 300420; 12.1bn USD in 2016) still account for high shares in global pharmaceuticals trade, only surpassed by “non-specified” other medicines, which account for 243bn USD in total pharmaceuticals trade (see Figure 1).

Table 1: Major medicines’ product categories and development of trade value, 2010 to 2016

Source: WTO COMTRADE.

Figure 1: Total trade value of major pharmaceuticals product categories, 2016, in bn USD

Source: WTO COMTRADE.

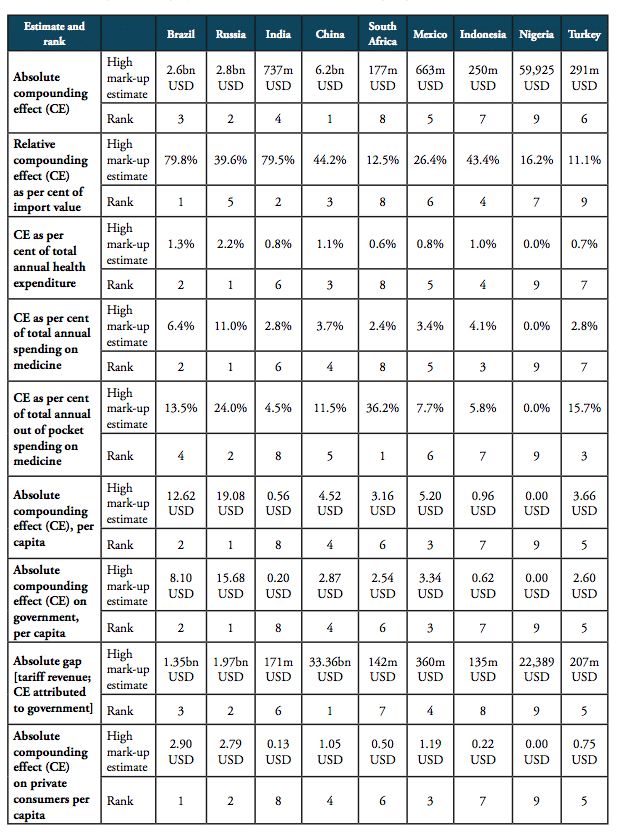

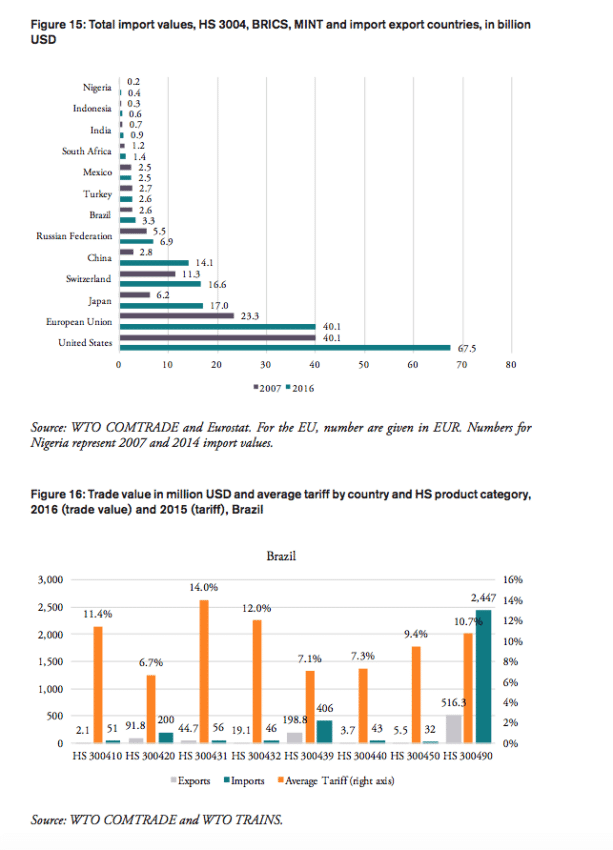

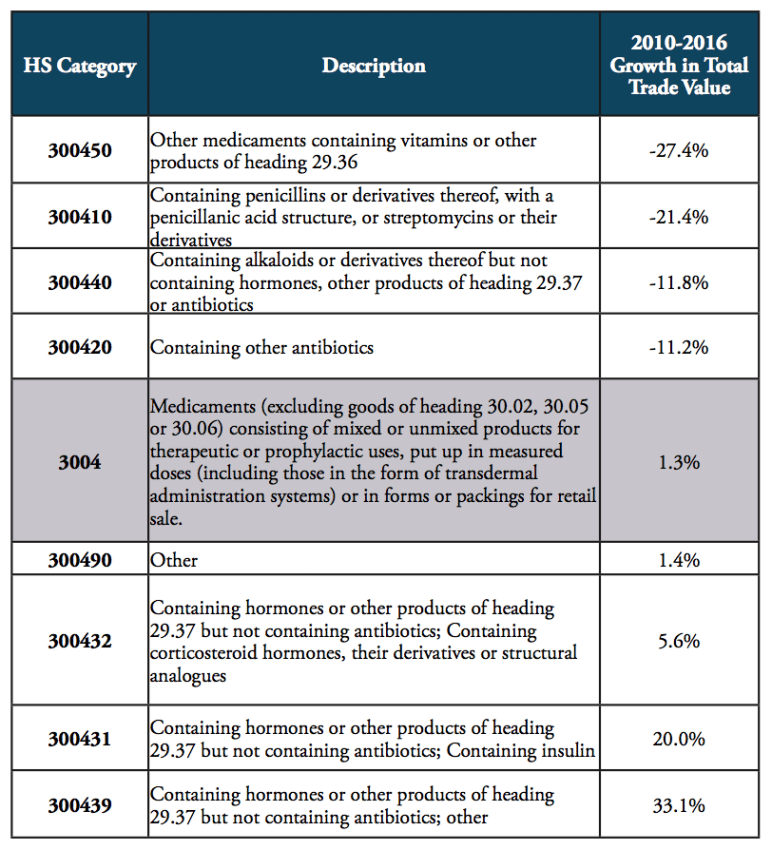

The volume of medicine products traded to and from BRICS and MINT countries has increased significantly in the past 20 years. BRICS and MINT countries’ trade in pharmaceuticals stood at 51bn USD in 2016. Together the group of BRICS-MINT countries accounted for 17.1 per cent of total world trade in pharmaceutical products of about 300bn USD in 2016. While global trade in pharmaceutical products increased by 33 per cent between 2007 and 2016, BRICS-MINT countries trade in pharmaceuticals grew by 98 per cent between 2007 and 2016 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Growth rates of trade in pharmaceuticals, 2007 to 2016

Source: WTO COMTRADE. For Nigeria, growth is given for the period 2009 to 2014 (the earliest and latest data available).

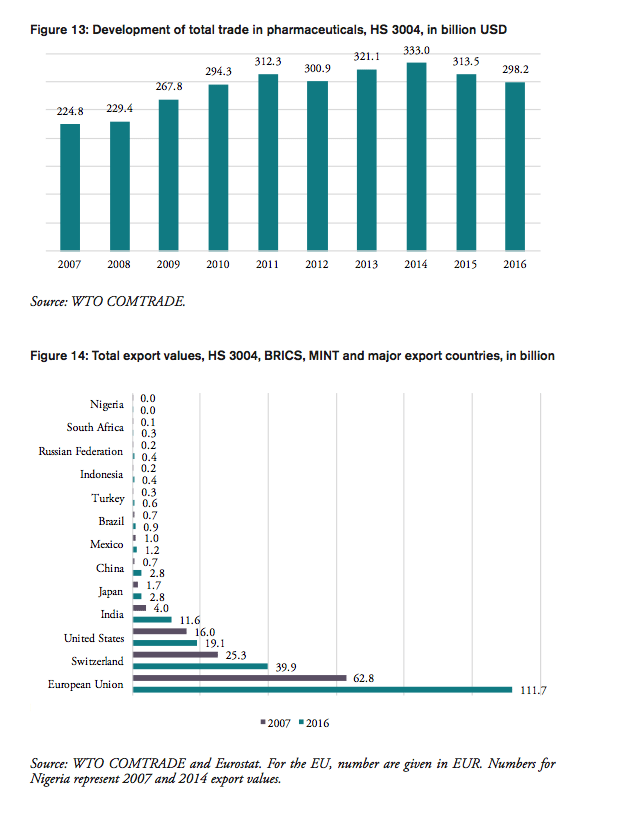

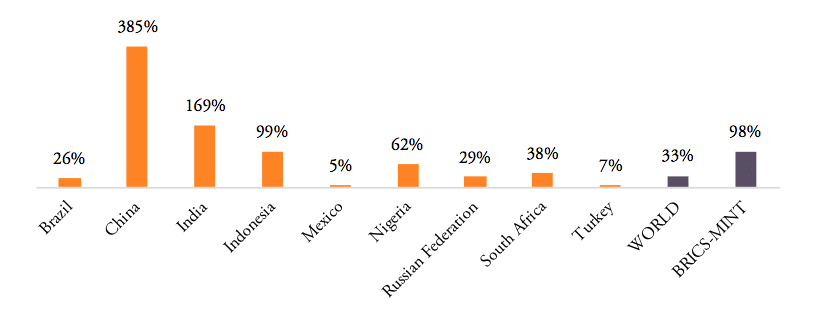

Contrary to the world’s largest pharmaceuticals producers of pharmaceutical products (the EU, Japan and Switzerland), BRICS-MINT countries’ trade in pharmaceuticals is generally characterized by trade deficits with the rest of the world (see Figure 3). Imports exceed exports by 100mn USD for Indonesia, 400mn USD for Nigeria, 1.3bn USD for Mexico, 2bn USD for Turkey, 2.4bn USD for Brazil, 6.5bn USD for Russia, and 11.3bn USD for China. The only exception is India, which shows a trade surplus in pharmaceutical products of 10.7bn USD in 2016.

Figure 3: Trade balances in medicine products, HS 3004, 2016, in bn USD

Source: WTO COMTRADE and Eurostat. For the EU, number are given in EUR.

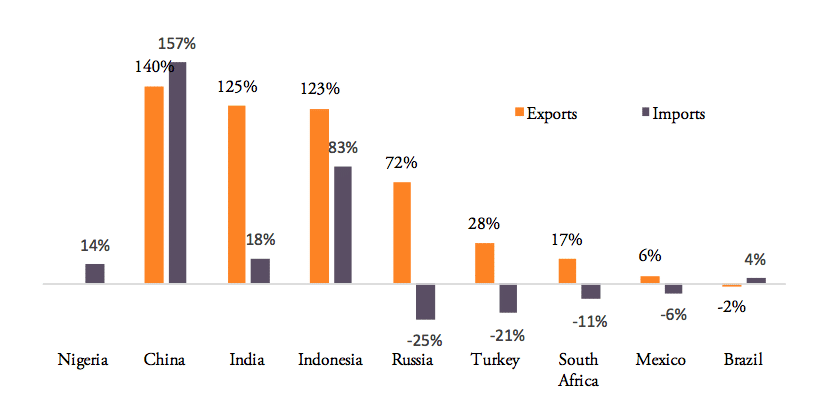

Between 2007 and 2016, pharmaceutical exports increased for all BRICS-MINT countries, except for Brazil, which shows a low 2 per cent decline in medicine exports (see Figure 4). For pharmaceutical imports to BRICS-MINT countries, the picture is much more diverse. Nigeria, China, India and Indonesia show rising import values for pharmaceuticals from abroad, while imports to Russia, Turkey, South Africa, Mexico and Brazil are lower than in 2007. At the same time, China, India, Indonesia and Russia show relatively high growth rates in pharmaceutical exports.

Figure 4: Export vs. import growth rates, 2007 – 2016

Source: WTO COMTRADE and Eurostat. For the EU, number are given in EUR. Note: Nigeria’s export growth rate for the period 2007 to 2014 (latest data available) was 1,499 per cent, an outlier, which has been eliminated from above chart.

Tariff Levels and Tariff Lines

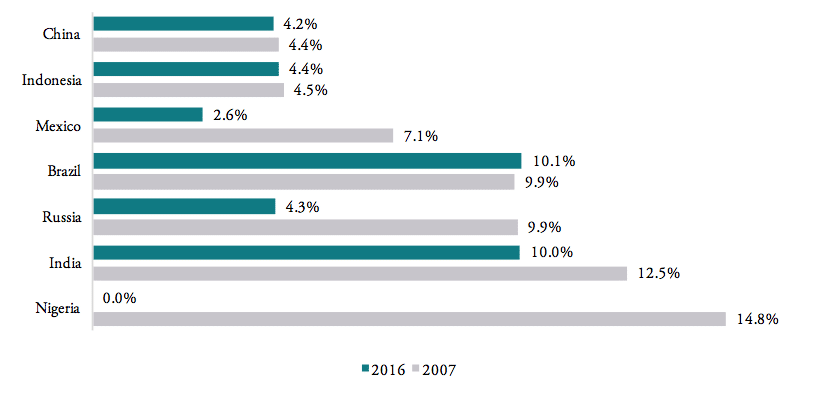

WTO data show that tariffs on pharmaceuticals are still high among BRICS-MINT countries. Weighted average tariffs for pharmaceutical products, which represent the effective rate of protection at aggregate import level, are 4.2 per cent for China, 4.4 per cent for Indonesia, 4.3 per cent for Russia, and 2.6 per cent for Mexico. The highest weighted average tariffs are found for Brazil (10.1 per cent) and India (10 per cent). At the same time, Nigeria, South Africa and Turkey already apply zero tariffs medicine products imported from abroad (see Figure 5). As concerns the development of tariff protection, the governments of China, Indonesia, Brazil and India have hardly reduced import tariffs for medicine products in the past decade, while Nigeria eliminated tariffs for all pharmaceuticals products (in 2013)[1] and Mexico reduced its import tariffs from an average 7.1 per cent to an average 2.6 per cent.

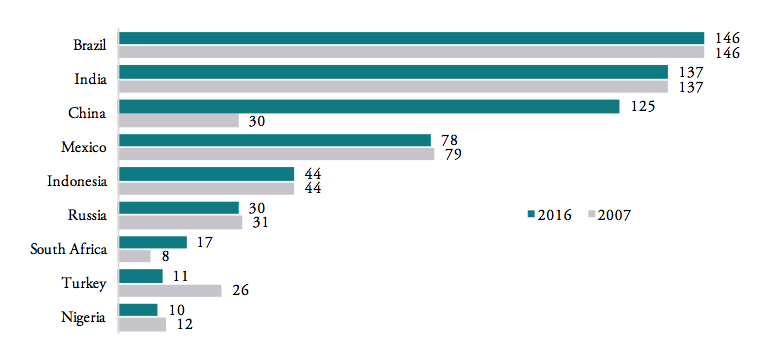

Similarly, the number of actively applied tariff lines[2] is still high for most BRICS-MINT countries, causing importers to struggle with administrative procedures and government discretion over product classification decisions. Figure 6 shows that, except for Nigeria (10 tariff lines), Turkey (11 tariff lines) and South Africa (17 tariff lines), all other BRICS-MINT countries apply more than 30 tariff lines for pharmaceuticals products within the HS 3004 product classification category. Brazil (146), India (137), China (125) and Mexico (78) apply the highest number of tariff lines. While the number of tariff lines applied by Brazil, India and Mexico did not change since 2007, the number of tariff lines applied by China significantly increased dramatically from 30 in 2007 to 125 in 2016, indicating a serious shift towards protectionism within the Chinese government.

Figure 5: Weighted average tariffs, by country, 2007 vs. 2016

Source: WTO TRAINS.

Figure 6: Number of tariff lines by country, 2016

Source: WTO TRAINS. Tariff line: a product as defined in lists of tariff rates. Products can be sub-divided, the level of detail reflected in the number of digits in the Harmonized System (HS) code use to identify the product. Note that Nigeria, South Africa and Turkey still disclose tariff lines even though tariffs are zero across all HS 3004 product categories.

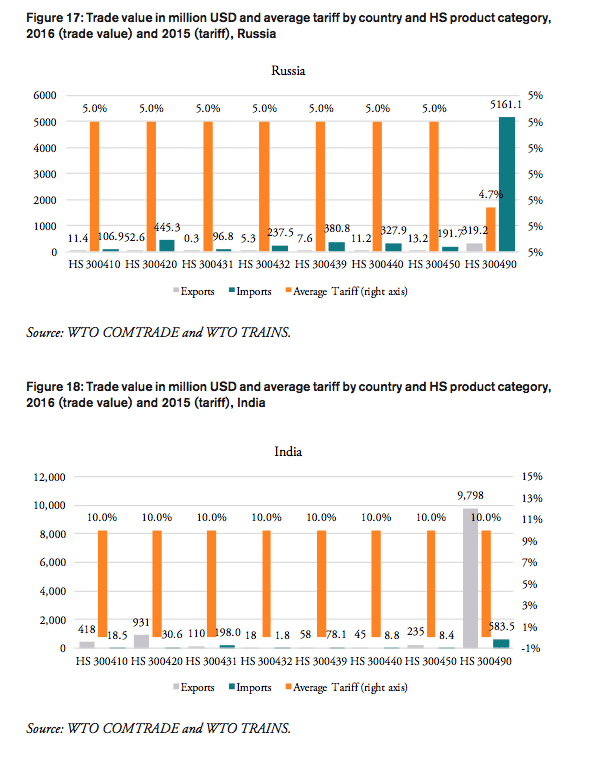

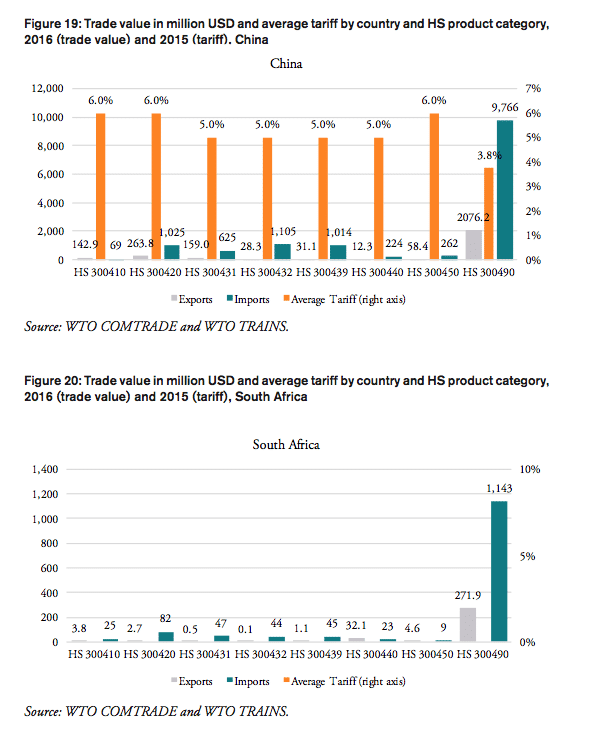

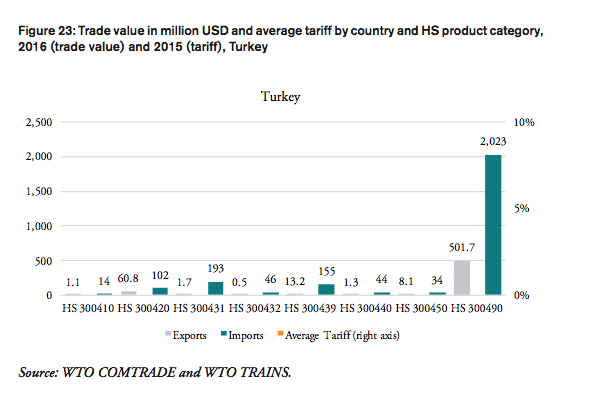

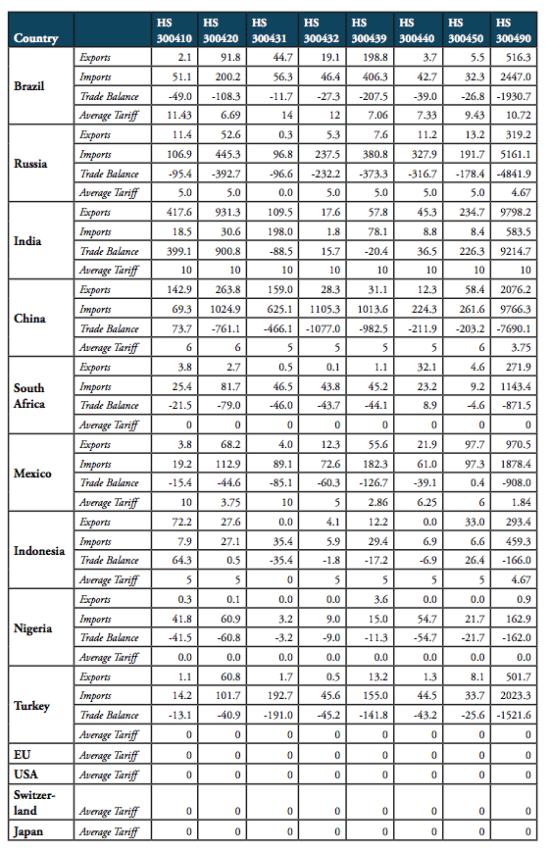

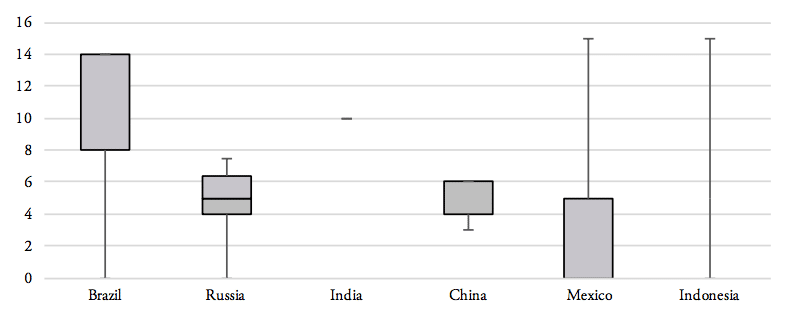

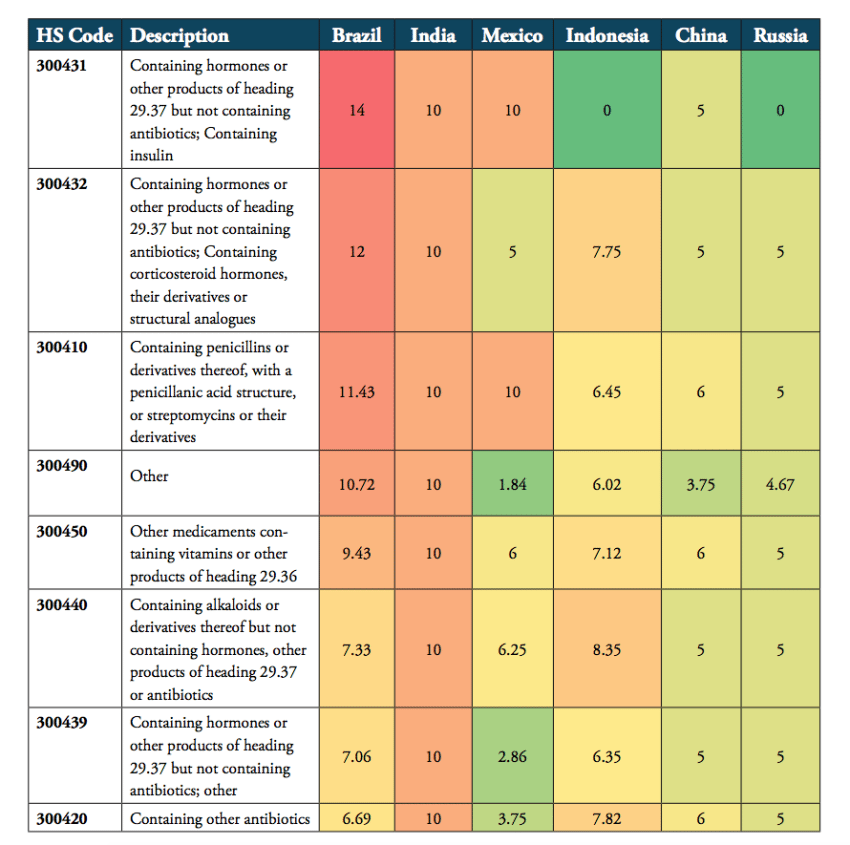

Table 2 shows that weighted applied average tariffs vary considerably across major sub-groups of pharmaceutical products. While India imposes a 10 per cent lump sum tariff across the board of imported medicine products, applied import tariffs for different products categories range from 0 to 14 percent for Brazil, 0 to 7.5 per cent for Russia, 3 to 6 per cent for China, 0 to 15 per cent for Mexico and 0 to 15 per cent for Indonesia (see Figure 7).

Table 2: Trade flows and weighted average import tariffs for major medicaments’ product categories, 2016, trade flows, in million USD, tariffs, in per cent

Source: WTO COMTRADE and WTO TRAINS. For Nigeria, trade values are given for 2014 (the latest data available).

Patterns in the Distribution of Import Tariffs on Pharmaceuticals (HS 3004)

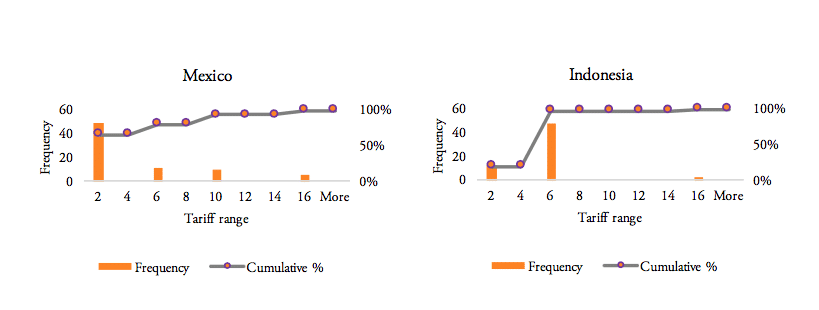

Our analysis of the distribution of import tariff levels across product-specific tariff lines reveals that half of Brazil’s tariff lines set import tariffs at levels of at least 8 per cent. Similarly, 50 per cent of pharmaceutical products’ tariff lines of Russia’s tariff schedule show import duties larger than 5 per cent. India, on the other hand, imposes a lump sum tariff of 10 per cent on every medicine product that is imported from abroad. 50 per cent of Mexico’s tariff lines show zero tariffs, while 25 per cent of Mexico’s tariff lines are set levels between zero and 5 per cent and another 25 per cent of Mexico’s import tariff lines show tariff levels between 5 and 15 per cent. Finally, 75 per cent of tariff lines in Indonesia’s tariff schedule are set at levels of at least 5 per cent (see Figure 8).

Figure 7: Distribution of pharmaceutical product tariffs within applied tariff lines

Source: WTO TRAINS. Note: numbers represent minimum, 1st quartile, median, 2nd quartile and maximum values for the entire range of applied tariff lines, by country.

Figure 8: Histograms representing the distribution of pharmaceuticals tariffs by country, 20obsc

Source: WTO TRAINS. Own calculations for the entire range of applied tariff lines, by country.

Tariffs imposed on pharmaceuticals of specific product categories vary considerably across BRICS-MINT countries. For the 8 product categories of the HS 3004 category, Brazil, India and Mexico are the most protectionist countries among the group of BRICS-MINT countries. All three countries employ a very high number of tariff lines and relatively high tariffs on almost all pharmaceutical products of the HS 3004 product group. For these countries, high tariffs are applied across the board of pharmaceutical products, i.e. medicines containing hormones, penicillin, vitamins, alkaloids, and, except for Mexico, antibiotics. Indonesia also applies relatively high tariffs for imported drugs that contain vitamins, penicillin, hormones and antibiotics. By comparison, tariffs applied by the governments of China and Russia are still far from zero, but lower than those applied by the governments of Brazil, India, Indonesia and Mexico (see Table 3).

As applied tariffs also vary substantially within HS 3004 product lines, foreign importers willing to export to these countries have to employ specialized, and therefore expensive resources to administer databases, certificates, customs and payment procedures and liaise with government authorities to be eligible to serve customers in these markets. All of these costs are passed on to importers in these countries, which, in addition to the nominal import tariff and domestic sales taxes, are passed on to distributors, pharmacies, hospitals, doctors and, finally, patients. The alignment and simplification of heterogeneous customs procedures and import requirements is the key rationale of the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), which was concluded in 2013 and entered into force on 22 February 2017. The full implementation TFA, if effectively implemented, is estimated to reduce trade costs by an average 14.3 per cent for African countries, while least developed countries (LDCs) could enjoy an even bigger reduction in trade costs (WTO 2017).

Table 3: Heat map of average tariffs for HS 3004 product categories, 2016, in per cent

Source: WTO TRAINS.

[1] On 16 January 2017, MEDICALWORLD NIGERIA wrote that Nigeria fixed her Common External Tariff at 0 per cent, and that the effect “is that despite the astronomical rise in foreign exchange rates, many Nigerians can still afford to buy daily used drugs and medicaments.” See https://www.medicalworldnigeria.com/2017/01/association-of-pharmaceutical-importers-of-nigeria-press-statement-on-imminent-scarcity-and-high-cost-of-medicament-looming#.WakeOa2B1eg, accessed on 1 September 2017.

[2] A tariff line reflects a product as defined in lists of tariff rates. Products can be sub-divided, the level of detail reflected in the number of digits in the Harmonized System (HS) code use to identify the product.

Effective Rates of Import Protection in BRICS-MINT Countries

The nominal tariff charged by customs authorities only tells part of the story of the real burden imposed on final consumers. At the counter, the final price of a medicine paid for by a consumer is a combination of the manufacturer’s price, various mark-ups by importers, wholesalers and distributors, and retail pharmacies, doctors and hospitals respectively (see, e.g., IFC 2017; IMS 2014a). Survey data presented by the International Finance Corporation (IFC 2017; referring to Health Action International (HAI) survey data) show that numerous mark-ups along the medicine distribution chain can account for up to 90 per cent of the final price to the consumer, and often are in the 30-50 per cent range in countries with unregulated mark-ups. Specifically, according to the IFC (2017), mark-ups range from

- 25 to 30 per cent for importers,

- 25 to 50 per cent for wholesalers,

- 25 to 75 per cent for sub-wholesalers,

- and 50 to 80 per cent for retailers (for generics products).

At a first glance, tariffs on pharmaceutical products in BRICS-MINT countries may look as if they make up a small proportion of the total cost of medicines only, adding a negligible amount of money to the price of medicines paid exclusively by importers. Yet, because of multiple percentage mark-ups that are added to the base import price of medicines (i.e. the ex factory price of a drug), even low tariffs add significantly to the final price of a medicine product when several mark-ups are charged by distributors along the distribution chain (see, e.g., Goel 2015; Olcay and Laing 2005[1]).

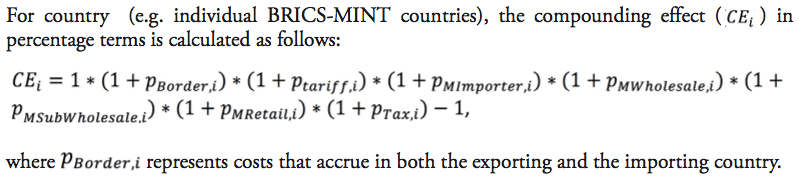

The compounding effect (CE) of import tariffs is reinforced by other measures, such as additional administrative costs due to inefficient border compliance procedures and documentation requirements.

In addition, in some countries, such as India, exclusive supply and distribution agreements, mandatory approvals and no-objection certificates issued (or not issued) by trade associations, limitations on the number of wholesalers, the abuse of market power and other forms of anti-competitive behavior may adversely affect competition in the market and final prices paid by consumers (patients or the government, i.e. taxpayers and contributors to health insurance programs; see UNCTAD India 2015). Importantly, in cases where anti-competitive behavior along the distribution chain of medicines gives power to incumbent companies to maintain (high) fixed percentage mark-ups, an import tariff will always work as a subsidy to distributors as it increases the upstream price on which mark-ups are based and absolute revenues of distributors respectively (see conclusion for additional considerations).

In the following, we estimate the compounding effect of imports tariffs on pharmaceutical imports to BRICS-MINT countries. We take into consideration average trade-weighted import tariffs for the HS 3004 product category. Since non-pecuniary border measures effectively contribute to the thickness of borders for imported commodities in general (see, e.g., Hornok and Koren 2011), we also take into consideration pre-shipment costs for exporters and importers due to current inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirements. We do not take into consideration the tariff equivalents of non-tariff trade barriers (NTBs), which may arise due to complex and lengthy pharmaceutical testing and marketing approval procedures in the importing countries.

Methodological Considerations

For exporters, import tariffs create two major types of distortions, which directly and indirectly feedback to prices at the counter: first, the nominal import tariff charged by customs authorities in the importing country, and second, administrative and trade facilitation costs related to import requirements, which increase the pre-shipment value of a commodity and its ex factory price respectively. As these two components add to the price of a medicine product at the very beginning of national distribution chains, the final distortions that they create for consumers in pharmacies, hospitals or doctors’ medical practices go well beyond the level of the actual tariff rate.

The following estimation illustrates how these distortions are passed on along the distribution chain of pharmaceutical imports in BRICS-MINT countries. We take into consideration a variety of components and their compounding effect on prices charged along the distribution chain of a pharmaceutical product, including:

- weighted average import tariffs for BRICS-MINT countries ),

- pre-shipment administrative costs related to country-specific inefficiencies in border compliance and import documentation procedures ),

- mark-ups charged by importers ),

- mark-ups charged by wholesalers),

- mark-ups charged by sub-wholesalers ),

- mark-ups charged by retailers ), and

- country-specific sales taxes on pharmaceutical products ),

It should be noted that the results presented below should not be taken by their precise face value. Due to data limitations and the use of proxy estimates for agents’ mark-ups across the distribution chain of medicines in low and middle income countries, we are not able to account for country-specific peculiarities in the logistics of medicines. In addition, we also did not account for preferential treatments of some imported medicines, e.g. special treatment resulting from tariff exemptions, tax exemptions or drug price controls and product-specific mark-up regulations,[2] due to data limitations. However, the methodology chosen for this analysis stylizes the major determinants of final prices for medicines in a way that allows us to estimate the direction and the size of the financial distortions created by import tariffs and border facilitation inefficiencies in a common way across all countries under study. At the same time, all our assumptions are based on empirical observations in pharmaceutical markets. Table 4 provides an overview of those variables that are used in our estimations as well as the sources of this data.

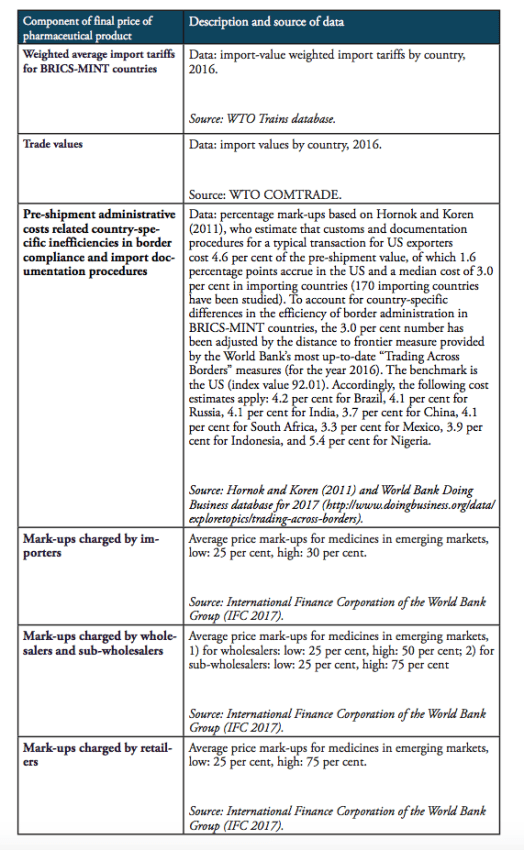

Table 4: Description of data and data sources

The compounding effect of import tariffs on pharmaceutical products is calculated for low and high mark-ups along national distribution chains, according to the estimates provided by IFC (2017). We provide estimates for two hypothetical trading regimes: one regime that is characterized by zero import tariffs on pharmaceutical products (i.e. the elimination of all existing import tariffs on HS 3004 pharmaceutical products) and a second regime that is, in addition to zero tariffs, characterized by a 50 per cent reduction of costs resulting from prevailing inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirements (based on the World Bank’ Doing Business indicators).

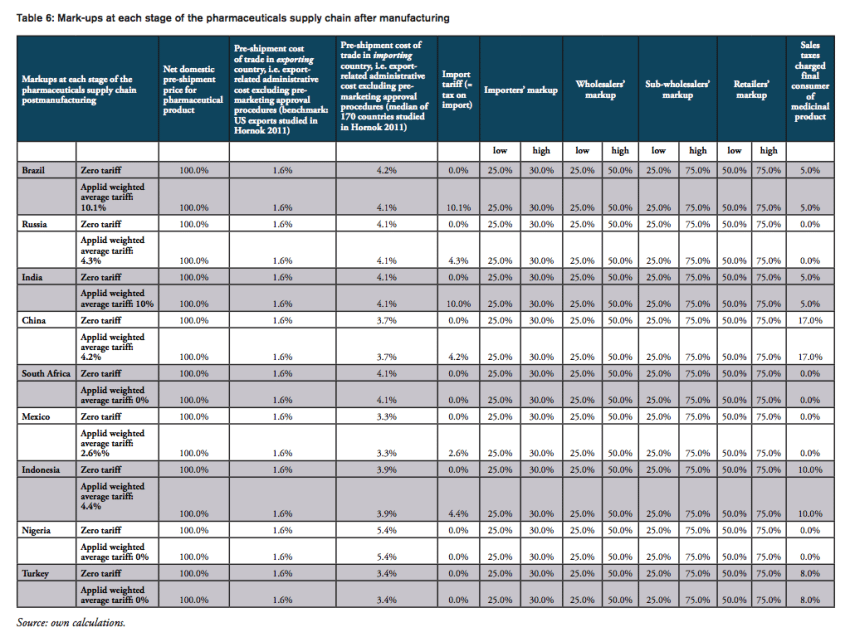

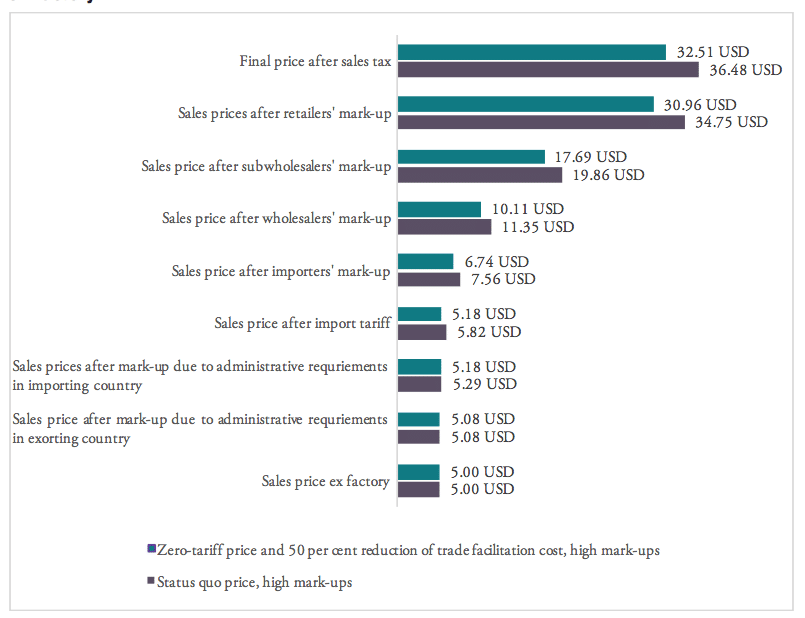

Figure 9 provides estimated numbers for the example of India. The Indian government imposes a lump sum tariff of 10 per cent on any kind of pharmaceutical product listed in the HS 3004 category. Assuming high mark-ups along the Indian distribution chain of a medicine product imported from abroad, the final sales price of a product sold at 5.00 USD ex factory (which corresponds to the pre-shipment value of a hypothetical drug) would be 36.48 USD under the current regime. This price is 3.97 USD higher compared to a price that would result from trade at zero-tariffs including a 50 per cent reduction of the costs resulting from prevailing trade facilitation inefficiencies (all other things equal). Accordingly, the overall compounding effect, i.e. the percentage mark-up on the pre-shipment import price of a drug, is 79.5 per cent of the sales price ex factory. For all countries under study, country-specific assumptions are outlined by Table 6 in the Appendix I.

Figure 9: Composition of the compounding effect for a medicine product sold at 5.00 USD ex factory

Source: own calculations.

Results

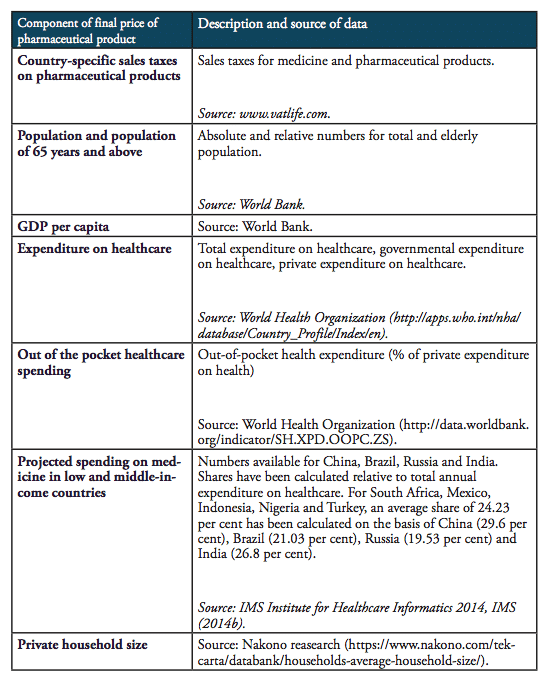

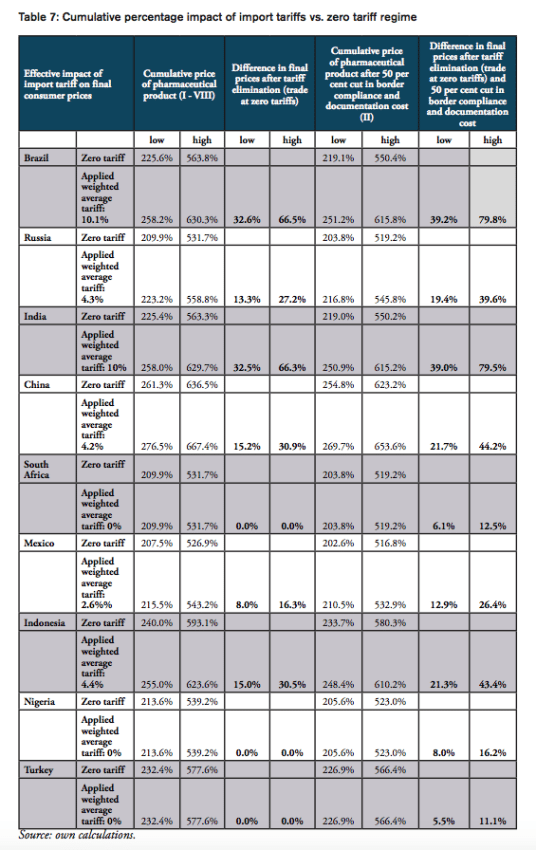

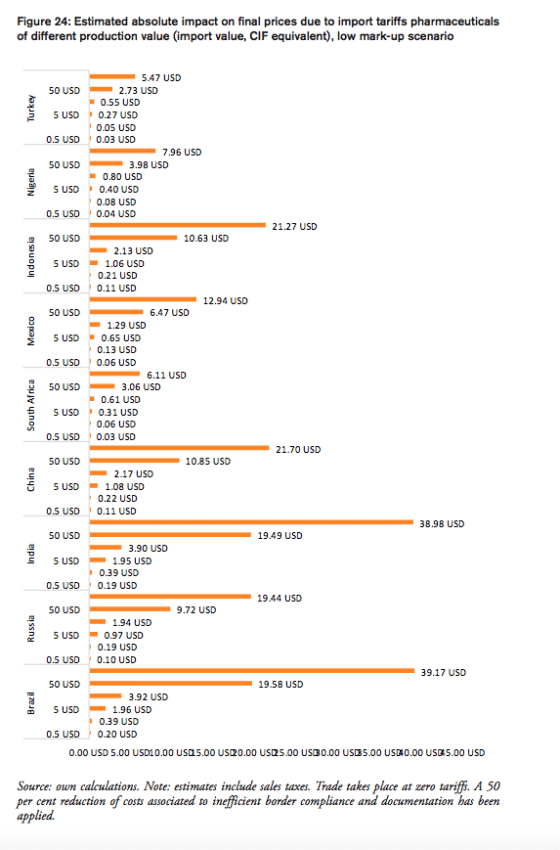

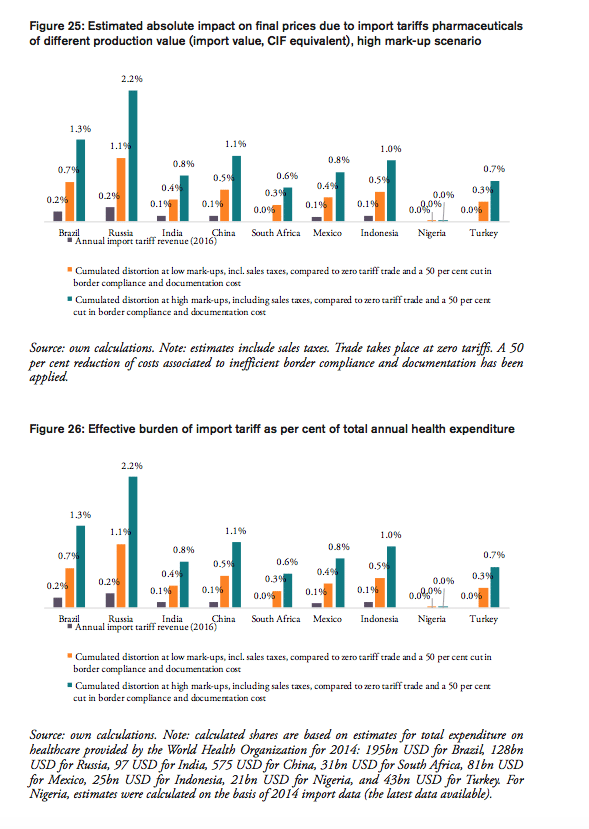

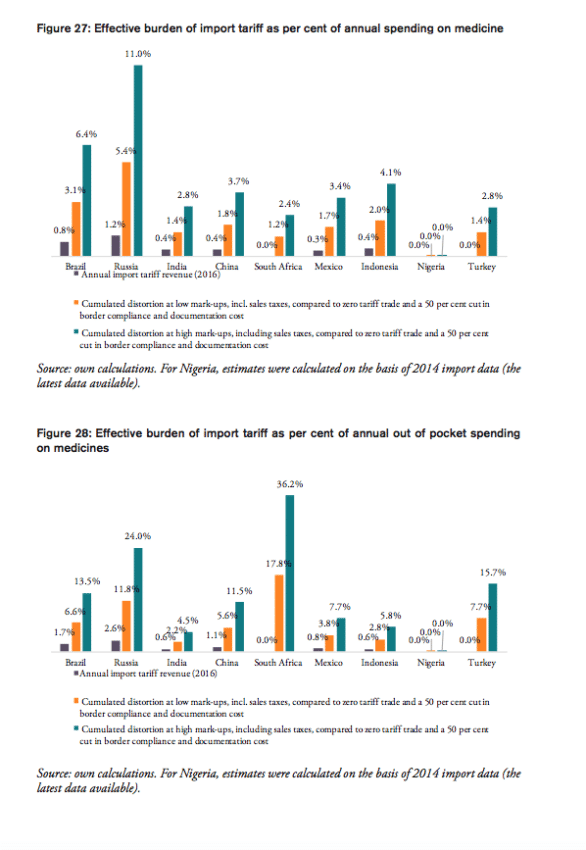

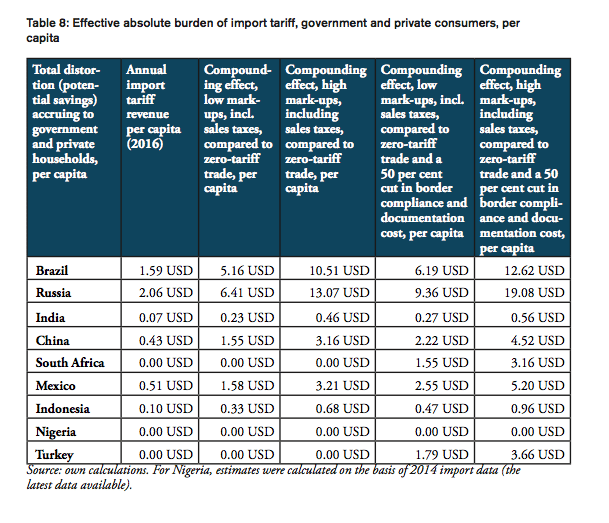

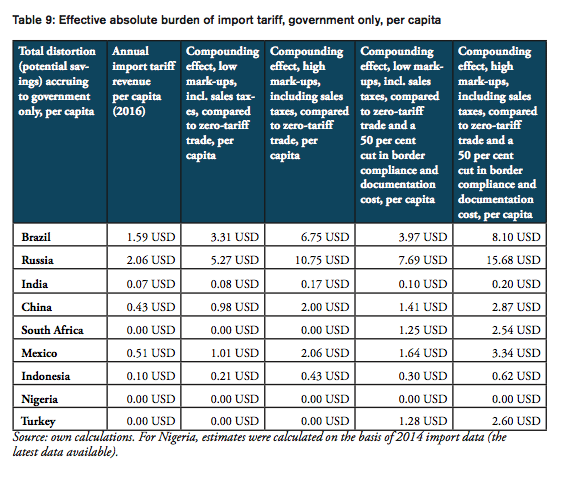

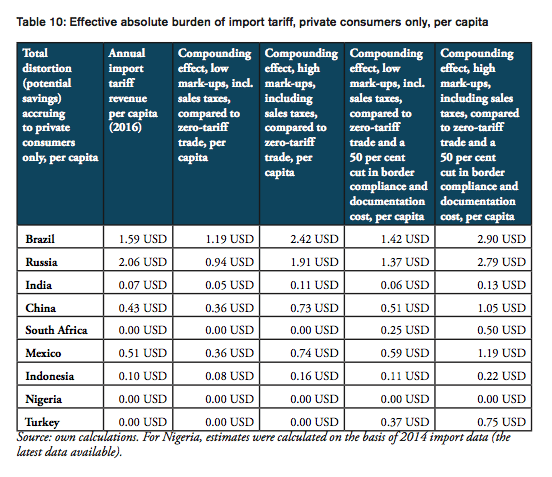

For all BRICS-MINT countries, a summary of country-specific estimates and the final country ranking is provided by Table 5. We provide estimates for (1) the compounding effect in per cent of the net import value of pharmaceutical products (see Figures 10 and 11 and Table 7 in Appendix I), (2) the absolute aggregate compounding effect based on 2016 import values (see Figure 12), (3) absolute price effects for a range of import prices ranging from 0.50 USD to 100.00 USD (see Appendix I, Figures 24 and 25), and estimates for the financial burden (potential savings) expressed (4) in per cent of total annual health expenditure (see Appendix I, Figure 26), (5) in per cent of total annual spending on medicines (see Appendix I, Figure 27) and (6) in per cent of total annual out of pocket spending on medicine (see Appendix I, Figure 28). Finally, estimates for the compounded financial burden are provided (7) on a per capita basis (see Appendix I, Table 8) and attributed to (8) the government (see Appendix I Table 9) and (9) individual private consumers and private households (see Appendix I, Tables 10 and 11). Country snapshots are provided in Appendix II.

Table 5: Summary of country-specific estimates and final ranking, high mark-ups scenario

Source: own calculations. Note: numbers represent absolute and relative estimates derived from the compounding effect () on the basis of high mark-ups in comparison to a scenario that is based on zero-tariff pharmaceuticals trade and a reduction of 50 per cent of costs related to general inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirement. For Nigeria, estimates were calculated on the basis of 2014 import data (the latest data available).

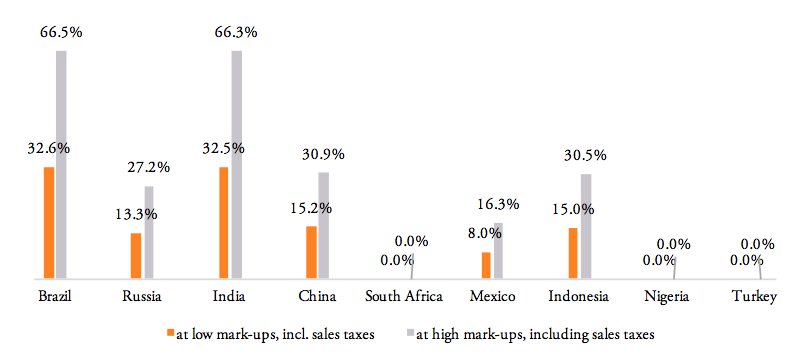

For the high mark-ups scenario, a summary of indicators (1) to (9) as well as country-specific ranking is given by Table 5. When measured in per cent of the ex factory price of a medicine product (Figures 10 and 11), the compounding effect is highest in Brazil (up to 79.8 per cent) and India (79.5 per cent), followed by China (44.2 per cent), Indonesia (43.4 per cent), Russia (39.6 per cent), and Mexico (26.4 per cent). Even though Nigeria, Turkey and South Africa apply zero tariffs on imports of pharmaceuticals, the financial burden of inefficient trade facilitation measures amounts up to 16.2 per cent (Nigeria), 12.5 per cent (Turkey) and 11.1 per cent (South Africa) of the ex factory price.

Figure 10: Effective financial burden of import tariff, in per cent of import value

Source: own calculations. Note: estimates do not include a reduction of (pre-shipment) trade costs due to inefficient border compliance procedures and documentation requirements.

Figure 11: Effective financial burden of import tariff and border inefficiencies, in per cent of import value

Source: own calculations. Note: estimates include sales taxes and a reduction of 50 per cent in (pre-shipment) trade costs due to inefficient border compliance and documentation inefficiencies. For Nigeria, estimates were calculated on the basis of 2014 import data (the latest data available).

The compounding effect per capita is highest for Russia (19.08 USD), Brazil (12.62 USD), Mexico (5.20 USD) and China (4.52 USD), followed by Turkey (3.66 USD), South Africa (3.16 USD), Indonesia (0.96 USD), and India (0.56). Due to low import volumes as well as zero import tariffs, the estimated numbers are only marginal for Nigeria.

When measured in per cent of annual out of pocket spending on medicine, the financial burden “directly” imposed on patients is highest in South Africa (36.2 per cent), Russia (24.0 per cent), Turkey (15.7 per cent), Brazil (13.5 per cent) and China (11.5 per cent), followed by Mexico (7.7 per cent), Indonesia (5.8 per cent), and India (4.5 per cent). The fact that total government spending on healthcare relative to total spending on healthcare is comparatively high in China (63 per cent), Russia (82 per cent) and Brazil (64 per cent) explains the relatively low direct impact on patients out of pocket spending in these countries. However, as the citizens of these countries have to pay taxes and make financial (health insurance) contributions to government-run healthcare programs, the citizens of these countries have to bear the financial burden imposed by import tariffs and inefficient trade facilitation measures and, accordingly, leaves them with less disposable income. Due to low import volumes as well as zero import tariffs, the estimated numbers are only marginal for Nigeria.

The results also indicate that the aggregated adverse impact of import tariffs on pharmaceuticals and cross-border trade facilitation inefficiencies (see Figure 12), is highest in China (up to 6.2bn USD), Russia (up to 2.8bn USD), Brazil (up to 2.6bn USD) and India (737mn USD; high tariffs, low import volume), followed by Mexico (663mn USD), Turkey (290mn USD; zero import tariffs), Indonesia (251mn USD), South Africa (177mn USD; zero import tariffs) and Nigeria (60tsd USD; zero import tariffs)[3].

Taking into account annual government tariff revenues reveals that the financial burden of import tariffs and trade facilitation inefficiencies that can be attributed to government spending on medicines exceeds tariff revenues by 3.36bn USD in China, 1.97bn USD in Russia and 1.35bn USD in Brazil, followed by 360mn USD in Mexico, 171mn USD in India, and 15mn USD in Indonesia. In other words, due to the compounding effect of import tariffs, governments alone tend to finally pay (or reimburse) between two and six times the amount they collect as tariff revenues at the border, while they would save that amount if trade would take place at zero tariffs.[4]

The aggregate average ranking indicates that the adverse financial impact of import tariffs on pharmaceuticals and prevailing cross-border trade facilitation inefficiencies is highest for Russia, Brazil and China, followed by Mexico, Turkey and Indonesia. Although import tariffs for pharmaceutical products are comparatively high for imports to India, the overall compounding effect for India is contained by India’s comparatively low volume of pharmaceutical imports. The fact that South Africa and Nigeria do not impose tariffs on pharmaceutical imports reflects these countries’ good overall score in the ranking of BRICS-MINT countries.

Figure 12: Aggregate compounding effects (CE) in USD

Source: own calculations.

[1] In their study, Olcay and Laing (2005) report that the compounded effect on final prices may add 20 per cent to the price of a medicine product. They conclude that “there are NO good reasons why those countries should retain tariffs. Tariffs on medicines target the sick which cannot be good public policy” (see page 36).

[2] Prices for individual medicines can significantly vary among countries. In a survey of 60 countries, a study by Health Action International (HAI 2010) found that the price a patient would have to pay for10ml soluble human insulin in 2010 varies significantly. Although Indonesia ($16.61-$51.15) and South Africa ($32.89-$40.47) had high prices, Nigeria ($18.65-$23.65), Brazil ($20.23-$25.46), India ($3.35-$7.89), and Turkey’s ($16.48-$16.80) prices were very low. None of these countries had higher prices than the US ($51.95-$62.39) and Austria ($76.69).

[3] For Nigeria, estimates were calculated on the basis of 2014 import data (the latest data available).

[4] Due to data limitations we did not account for preferential treatments of some imported medicines, e.g. special treatment resulting from tariff exemptions, tax exemptions or drug price controls and product-specific mark-up regulations. As several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration. Although sales taxes impact on the revenues and expenditures of several strands of government, the net impact on total government revenues would be neutral. For final consumers, i.e. patients, applicable sales taxes substantially increase the price of medicines that are purchased in hospitals, doctors’ practices and pharmacies.

Concluding Remarks

The volume of pharmaceutical products traded to and from BRICS and MINT countries has increased substantially in the past 20 years. While global trade in pharmaceutical products increased by 33 per cent between 2007 and 2016, BRICS-MINT countries’ trade in pharmaceuticals grew by 98 per cent over the same period. Accordingly, a larger proportion of globally marketed medicine products are subject to tariffs, which our analysis shows substantially increase upstream prices along national distribution chains of medicines.

Except for South Africa, Turkey and Nigeria, tariffs on pharmaceuticals are still high among BRICS-MINT countries. While South Africa, Turkey and Nigeria successfully eliminated import tariffs on pharmaceuticals, other countries still apply tariffs of up to 15 per cent for some product categories. In addition to general inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirements, the high number of actively managed “applied tariff lines” causes foreign producers and importers to struggle with opaque administrative procedures and government discretion over product classification issues.

The analytical component of this study has shown that even a low nominal import tariff and tariff equivalents related to inefficient trade facilitation procedures add significantly to the final price of a medicine product in BRICS-MINT countries, where several wholesalers and sub-wholesalers amplify the compounding effect of import tariffs across the supply chain. Depending on country-specific characteristics, the overall compounding effects, i.e. the total financial burden accruing to consumers (patients) in the importing countries, range from 6 to 11 per cent of the import value in Turkey to 39 to 80 per cent of the import value in Brazil and India. The results indicate that the potential aggregate savings for consumers (patients) would be highest in China (up to 6.2bn USD), Russia (up to 2.8bn USD), Brazil (up to 2.6bn USD), and India (737mn USD) – a financial burden that has so far not entered the scene of public debates about access to affordable medicines, and money that could be spent on other purposes and create additional economic activity and employment respectively. Assuming an average annual income of 10,000 USD, for example, the estimated compounded burden of import tariffs and prevailing trade facilitation inefficiencies amounts to an equivalent of up to 620,000 jobs in China. Similarly, assuming that low and medium skilled workers in India earn between 1,500 and 3,000 USD per year, the estimated compounded burden amounts to an equivalent of up to 250,000 to 500,000 jobs in India (even though India’s current import volumes of pharmaceuticals are comparatively low).

Most BRICS-MINT governments directly buy, settle or reimburse patients’ invoices for a bulk of medicine products. Although we were not able to account for idiosyncratic characteristics of government purchase and reimbursement programs for medicines, e.g. price controls, exemptions from tariffs and sales taxes (Russia, South Africa, Mexico and Nigeria do not apply sales taxes on medicines products), the sum of all tariff-induced premiums on final prices for pharmaceuticals paid for by governments tends to exceed by far the tariff revenues initially collected by these governments’ customs authorities – raising the serious question of whether the net burden for taxpayers and consumers alike constitutes an unintended consequence of national protectionism or deliberate industrial policymaking to the detriment of low income patients’ access to medicines. In any case, patients in these countries could either pay less out of their own pockets for medicines or make fewer contributions (lower taxes, insurance premia) on governmental healthcare spending programs.

There is another important phenomenon that merits policymakers’ attention: the compounding effect is significantly reinforced by prevailing inefficiencies and anti-competitive behaviour of firms that operate in national distribution chains. In countries where anti-competitive behaviour along the distribution chain of medicines gives power to incumbent companies to maintain (high) fixed percentage mark-ups, an import tariff will always work as a subsidy to distributors, because the tariff increases the upstream price on which mark-ups are based and absolute revenues of downstream distributors respectively. This may lead to a political economy, in which customs authorities and pharmaceutical distributors may have a common interest in maintaining (high) import tariffs – to the detriment of patients and government healthcare programs, which effectively have to redistribute income to customs authorities and distributors. Paradoxically, mark-up regulations that set maximum percentage limits on mark-ups charged by distributors may reinforce this effect.

Our results show that BRICS-MINT countries would strongly benefit from acceding the zero-for-zero agreement on pharmaceuticals, to which “only” 34 developed economies so far signed up to. Tariff-free trade should include all prescription drugs, all unfinished products (including antibiotics, vitamins, hormones and alkaloids), chemical intermediates used in the production of pharmaceuticals as well as vaccines. Regarding the latter, contrary to popular opinion, imports of vaccines are still subject to import tariffs in six BRICS-MINT countries (tariffs on vaccines are 3.8 per cent for Brazil, 3.0 per cent for China, 10.0 per cent for India, 2.2 per cent for Indonesia, 3.9 per cent for Mexico, and 3.4 per cent for Russia). Accordingly, given the high volumes of imports of vaccines, the financial burden on patients in BRICS-MINT countries would be even higher if vaccines were taken into consideration. Similar to pharmaceuticals, the public debate about access to vaccines does not touch on the adverse distortions created by import tariffs and trade facilitation inefficiencies, which are a direct responsibility of national governments, and neither in the reach of pharmaceutical manufacturers nor importers and distributors.

Summarizing the above, contrary to political endeavors to tackle local frictions in the distribution of medicines in most low and middle income countries, such as a lack of education of doctors and medical advisors, effective and non-discriminatory price and mark-up controls, high levels of corruption across the distribution chain, or the lack of domestic innovative and productive capacities, the elimination of all tariffs on pharmaceutical imports would be low hanging fruit. It would increase the access to medicine for low income patients and contribute to the realization of the right to health in low and middle income countries. Further empirical research should focus on tariffs and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) and their socio-economic impact on access to medicines in BRICS and MINT economies as well as other low and middle income countries. Future research should also include vaccines, active and inactive ingredients of pharmaceutical products, medical devices and barriers to healthcare services that are traded across borders.

References

Banik, N. and Stevens, P. (2015), Pharmaceutical tariffs, trade flows and emerging economies, publication of the Geneva Network, September 2015, available at: http://geneva-network.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/GN-Tariffs-on-medicines.pdf, accessed on 10 August 2017.

Goel, N. (2015), Assessing the impact of price control measures on access to medicines in India, IMS Health, July 2015, available at: http://freepdfhosting.com/65888ecb0d.pdf.

HAI (2010), Life-saving insulin largely unaffordable – A one day snapshot of the price of insulin across 60 countries, available at: http://www.haiweb.org/medicineprices/07072010/Global_briefing_note_FINAL.pdf, accessed on 20 August 2017.

Hornok, C. and Koren, M. (2011), Administrative barriers and the lumpiness of trade, EFIGE Working Paper 36, October 2011.

IFC (2017), Private Sector Pharmaceutical Distribution and Retailing in Emerging Markets

Making the Case for Investment, International Finance Corporation of the World Bank Group.

IMS (2014a), Understanding the pharmaceutical value chain, IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

IMS (2014b), Global Outlook for Medicines Through 2018, IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

OHCHR (2017), Access to medicines – a fundamental element of the right to health, available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Development/Pages/AccessToMedicines.aspx, accessed on 1 September 2017.

Olcay, M. and Laing, R. (2005), Pharmaceutical Tariffs: What is their effect on prices, protection of local industry and revenue generation?, Prepared for the Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation and Public Health, May 2005.

Sammut, M. and Levine, S. (2016), Neat, Plausible, and Wrong: Why the focus on intellectual property fails to address the complexities of medicinal access in India, Publication released in June 2016, prepared for the Biotechnology Innovation Organization and the Association of Biotechnology Led Enterprises.

UN (2016), Report of the of the Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines – Promoting innovation and access to health technologies, September 2016, available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/562094dee4b0d00c1a3ef761/t/57d9c6ebf5e231b2f02cd3d4/1473890031320/UNSG+HLP+Report+FINAL+12+Sept+2016.pdf, accessed on 10 August 2017.

UN (2015), Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E, accessed on 10 August 2017.

WHO (1946), Constitution of the World Health Organization, available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf?ua=1, accessed on 10 August 2017.UN (2016), Report of the of the Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines – Promoting innovation and access to health technologies, September 2016, available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/562094dee4b0d00c1a3ef761/t/57d9c6ebf5e231b2f02cd3d4/1473890031320/UNSG+HLP+Report+FINAL+12+Sept+2016.pdf, accessed on 10 August 2017.

UN (2015), Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E, accessed on 10 August 2017.

UNCTAD India (2015), Seventh United Nations Conference to review the UN Set on Competition Policy, Roundtable on: Role of Competition in the Pharmaceutical Sector and its Benefits for Consumers, Geneva, 6-10 July 2015.

WHO (2004), The World Medicines Situation, World Health Organization, available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s6160e/s6160e.pdf, accessed on 20 August 2017.

WHO (1946), Constitution of the World Health Organization, available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf?ua=1, accessed on 10 August 2017.

WTO (2017), WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Fact Sheet, available at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tradfa_e/tfa_factsheet2017_e.pdf, accessed on 1 September 2017.

Appendix I

Appendix II – Country Snapshots

Brazil

In 2016, the weighted average tariff for pharmaceuticals imported to Brazil was 10.1 per cent, while imported pharmaceutical products were worth 3.3bn USD. While tariff revenues collected by the Brazilian government amount to 330mn USD, the total financial burden imposed on Brazilian consumers of medicines amounts up to 2.2bn USD compared to trade at zero tariffs and 2.6bn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For Brazil, the compounding effect ranges from 33 per cent (low mark-ups, zero-tariff trade) to 80 per cent (high mark-ups, zero-tariff trade, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies) of the import value of a pharmaceutical product. In other words, Brazilian consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 80 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to the imposition of an import tariff at the border.

Compared to a zero-tariff trade regime and more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in Brazil currently pay a premium ranging from 0.20 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.40 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Brazilian consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 39.17 USD to 79.83 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from the elimination of import tariffs and the reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 1.3 per cent of Brazil’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 6.4 per cent of Brazilians total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 13.5 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 12.62 USD per capita. While the Brazilian government collects net tariff revenues of 1.59 USD per capita, it spends up to 6.75 USD per capita more on medicines compared to trade at zero tariffs and 8.10 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Brazilian government accounts for 64 per cent of total Brazilian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the Brazilian government amounts up to 6.51 USD per capita or 1.35bn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 36 per cent of total Brazilian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the average financial burden on Brazilian consumers amounts up to 2.90 USD per capita and 9.28 USD per household respectively.

Russia

In 2016, the weighted average tariff for pharmaceuticals imported to Russia was 4.3 per cent, while imported pharmaceutical products were worth 6.9bn USD. While tariff revenues collected by the Russian government amount to 297mn USD, the total financial burden imposed on Russian consumers of medicines amounts up to 1.9bn USD compared to trade at zero tariffs and 2.8bn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For Russia, the compounding effect ranges from 13 per cent (low mark-ups, zero-tariff trade) to 40 per cent (high mark-ups, zero-tariff trade, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies) of the import value of a pharmaceutical product. In other words, Russian consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 40 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to the imposition of an import tariff at the border.

Compared to a zero-tariff trade regime and more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in Russia currently pay a premium ranging from 0.10 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.20 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Russian consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 19.44 USD to 39.63 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from the elimination of import tariffs and the reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 2.2 per cent of Russia’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 11.0 per cent of Russians total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 24.0 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 19.08 USD per capita. While the Russian government collects net tariff revenues of 2.06 USD per capita, it spends up to 10.75 USD per capita more on medicines compared to trade at zero tariffs and 15.68 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Russian government accounts for 82 per cent of total Russian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the Russian government amounts up to 13.62 USD per capita or 1.97bn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 18 per cent of total Russian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the average financial burden on Russian consumers amounts up to 2.79 USD per capita and 7.20 USD per household respectively.

India

In 2016, the weighted average tariff for pharmaceuticals imported to India was 10.0 per cent, while imported pharmaceutical products were worth 927mn USD. Although tariff revenues collected by the Indian government amount to 93mn USD, the total financial burden imposed on Indian consumers of medicines amounts up to 615mn USD compared to trade at zero tariffs and 737mn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For India, the compounding effect ranges from 33 per cent (low mark-ups, zero-tariff trade) to 80 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, zero-tariff trade, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, Indian consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 80 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to the imposition of an import tariff at the border.

Compared to a zero-tariff trade regime and more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in India currently pay a premium ranging from 0.19 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.40 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Indian consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 38.98 USD to 79.46 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from the elimination of import tariffs and the reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 0.8 per cent of India’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 2.8 per cent of India’s total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 4.5 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 0.56 USD per capita. While the Indian government collects net tariff revenues of 0.07 USD per capita, it spends up to 0.17 USD per capita more on medicines compared to trade at zero tariffs and 0.20 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Indian government accounts for 36 per cent of total Indian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss for the Indian government amounts up to 0.13 USD per capita or 171mn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 64 per cent of total Indian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the average financial burden on Indian consumers amounts up to 0.13 USD per capita and 0.53 USD per household respectively.

China

In 2016, the weighted average tariff for pharmaceuticals imported to China was 4.2 per cent, while imported pharmaceutical products were worth 14bn USD. While tariff revenues collected by the Chinese government amount to 596mn USD, the total financial burden imposed on Chinese consumers of medicines amounts up to 4.36bn USD compared to trade at zero tariffs and 6.23bn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For China, the compounding effect ranges from 15.2 per cent (low mark-ups, zero-tariff trade) to 44.2 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, zero-tariff trade, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, Chinese consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 44.2 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to the imposition of an import tariff at the border.

Compared to a zero-tariff trade regime and more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in China currently pay a premium ranging from 0.11 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.22 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Chinese consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 21.70 USD to 44.23 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from the elimination of import tariffs and the reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 1.1 per cent of China’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 3.7 per cent of China’s total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 11.5 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 4.52 USD per capita. While the Chinese government collects net tariff revenues of 0.43 USD per capita, it spends up to 2.00 USD per capita more on medicines compared to trade at zero tariffs and 2.87 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Chinese government accounts for 63 per cent of total Chinese healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the Chinese government amounts up to 2.43 USD per capita or 3.36bn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 37 per cent of total healthcare expenditure in China (WHO data), the average financial burden on Chinese consumers amounts up to 1.05 USD per capita and 3.18 USD per household respectively.

South Africa

The South African government does not impose tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals. In 2016, South Africa imported pharmaceutical products worth 1.4bn USD. The total financial burden imposed on South African consumers of medicines amounts up to 176mn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For South Africa, the compounding effect amounts to 12.5 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, South African consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 12.5 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to costs resulting from inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirements.

Compared to a regime of more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in South Africa currently pay a premium ranging from 0.03 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.06 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, South African consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 6.11 USD to 12.46 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from a reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 0.6 per cent of South Africa’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 2.4 per cent of South Africa’s total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 36.2 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine (out of pocket spending on healthcare, as measured by the WHO, amounts to 7 per cent of total spending on healthcare in South Africa, which is low compared to other BRICS-MINT countries).

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 3.16 USD per capita. The South African government spends up to 2.54 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the South African government accounts for 80 per cent of total South African healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the South African government amounts up to 2.54 USD per capita or 142mn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 20 per cent of total healthcare expenditure in South Africa (WHO data), the average financial burden on South African consumers amounts up to 0.50 USD per capita and 1.95 USD per household respectively.

Mexico

In 2016, the weighted average tariff for pharmaceuticals imported to Mexico was 2.6 per cent, while imported pharmaceutical products were worth 2.5bn USD. Tariff revenues collected by the Mexican government amount to 65mn USD and the total financial burden imposed on Mexican consumers of medicines amounts up to 409mn USD compared to trade at zero tariffs and 663mn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For Mexico, the compounding effect ranges from 8.0 per cent (low mark-ups, zero-tariff trade) to 26.4 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, zero-tariff trade, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, Mexican consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 26.4 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to the imposition of an import tariff at the border.

Compared to a zero-tariff trade regime and more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in Mexico currently pay a premium ranging from 0.06 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.13 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Mexican consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 12.94 USD to 26.38 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from the elimination of import tariffs and the reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 0.8 per cent of Mexico’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 3.4 per cent of Mexico’s total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 7.7 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 5.20 USD per capita. While the Mexican government collects net tariff revenues of 0.51 USD per capita, it spends up to 2.06 USD per capita more on medicines compared to trade at zero tariffs and 3.34 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Mexican government accounts for 64 per cent of total Mexican healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the Mexican government amounts up to 2.83 USD per capita or 360mn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 36 per cent of total healthcare expenditure in Mexico (WHO data), the average financial burden on Mexican consumers amounts up to 1.19 USD per capita and 4.60 USD per household respectively.

Indonesia

In 2016, the weighted average tariff for pharmaceuticals imported to Indonesia was 4.4 per cent, while imported pharmaceutical products were worth 578mn USD. Meanwhile, tariff revenues collected by the Indonesian government amount to 25mn USD, the total financial burden imposed on Indonesian consumers of medicines amounts up to 176mn USD compared to trade at zero tariffs and 250mn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For Indonesia, the compounding effect ranges from 15 per cent (low mark-ups, zero-tariff trade) to 43.4 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, zero-tariff trade, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, Indonesian consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 43.4 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to the imposition of an import tariff at the border.

Compared to a zero-tariff trade regime and more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in Indonesia currently pay a premium ranging from 0.11 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.22 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Indonesian consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 21.27 USD to 43.35 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from the elimination of import tariffs and the reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 1.0 per cent of Indonesia’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 4.1 per cent of Indonesia’s total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 5.8 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 0.96 USD per capita. While the Indonesian government collects net tariff revenues of 0.10 USD per capita, it spends up to 0.43 USD per capita more on medicines compared to trade at zero tariffs and 0.62 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Indonesian government accounts for 64 per cent of total Indonesian healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the Indonesian government amounts up to 0.52 USD per capita or 136mn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 36 per cent of total healthcare expenditure in Indonesia (WHO data), the average financial burden on Indonesian consumers amounts up to 0.22 USD per capita and 0.83 USD per household respectively.

Nigeria

The Nigerian government does not impose tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals. In 2014 (latest import data available), Nigeria imported pharmaceutical products worth 369,000 USD. The total financial burden imposed on Nigerian consumers of medicines amounts up to 60,000 USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For Nigeria, the compounding effect amounts to 16.2 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, Nigerian consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 16.2 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to costs resulting from inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirements.

Compared to a regime of more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in Nigeria currently pay a premium ranging from 0.04 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.08 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Nigerian consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 7.96 USD to 16.23 USD per unit.

As Nigeria’s imports of pharmaceutical products are relatively low compared to other BRICS-MINT countries, the percentage savings are only marginal when expressed in per cent of the country’s overall spending on healthcare as well as medicines and out of pocket spending.

Turkey

The government of Turkey does not impose tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals. In 2016, Turkey imported pharmaceutical products worth 2.6bn USD. The total financial burden imposed on Turkish consumers of medicines amounts up to 291mn USD when border compliance and documentation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. For Turkey, the compounding effect amounts to 11.1 per cent of the import value of a pharmaceutical product (high mark-ups, reduction in trade facilitation inefficiencies). In other words, Turkish consumers currently have to pay a premium of up to 11.1 per cent of the import value of a medicine product due to costs resulting from inefficiencies in border compliance procedures and documentation requirements.

Compared to a regime of more efficient trade facilitation procedures, consumers in Turkey currently pay a premium ranging from 0.03 USD (low mark-ups) and 0.06 USD (high mark-ups) on a medicine product that is initially exported at a price of 0.50 USD. For medicines sold at 100 USD per unit at the border, Turkish consumers currently pay a premium ranging from 5.47 USD to 11.14 USD per unit.

The potential savings that would result from a reduction of existing inefficiencies in trade facilitation procedures amount up to 0.7 per cent of Turkey’s total annual healthcare expenditure in 2014 (based on WHO data), 2.8 per cent of Turkey’s total annual spending on medicines (based on IMS 2014b projections for 2018) and 15.7 per cent of total out of pocket spending on medicine.

The total financial burden imposed on both government and private consumers of pharmaceutical products amounts up to 3.66 USD per capita. The Turkish government spends up to 2.60 USD more per capita when border facilitation inefficiencies are taken into consideration. In other words, given that the Turkish government accounts for 71 per cent of total Turkish healthcare expenditure (WHO data), the net loss of the Turkish government amounts up to 2.60 USD per capita or 207mn USD per year (as several exemptions apply for sales taxes and government(-mediated) purchases of pharmaceutical products, government revenues from sales taxes have not been taken into consideration). Given that private household expenditure on healthcare accounts for 29 per cent of total healthcare expenditure Turkey (WHO data), the average financial burden on Turkish consumers amounts up to 0.75 USD per capita and 2.90 USD per household respectively.