Sweden, UK and the EU: Managing post-Brexit Relations and Defining a new Agenda for European Competitiveness

Published By: David Henig

Subjects: EU Single Market EU Trade Agreements UK Project

Summary

There is an urgent need to move on from the shock of the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, and all the melodrama in the past two years over what form Brexit should take, and focus on building a new relationship between the UK and EU including Member States such as Sweden. Trade and political relationships face change, but there is much that can be done to make sure that negative effects are temporary, and that we find a stable future path.

Both the EU and the UK wish to pursue a deep economic relationship, maintaining trade links insofar as possible in line with the stated red lines of both. The relationship will only be decided with many years of talking, but in this paper we suggest a structure that builds on existing EU practice of putting in place a web of agreements with third countries, anchored by something like an Association Agreement.

Part of this will be dependent on the way the EU’s competitiveness agenda develops. Sweden and the UK achieved much together as members of the EU, in progressing their shared agenda to pursue an open, competitive Europe, with a deepening single market and trade agreements increasing in number and ambition. It is now down to Sweden to work with others across the EU to maintain this agenda, against some strong influences which suggest the development of a more closed EU, a defensive trade policy and dirigiste industrial policy.

It is likely that the most economically significant trade agreement that the next Commission will negotiate is with the UK. Sweden can, with like-minded countries, help to facilitate a mutually beneficial arrangement, drawing for instance on the experience of Nordic cooperation. Existing structures such as the Northern Futures Forum should be strengthened. It will not be easy, but Sweden is one of those best placed to provide leadership. Creating a conceptual framework for what team Sweden want to see in the EU, then working with others to make this happen, should therefore be a priority for the Swedish government and business. The UK government should equally prioritise rebuilding previously strong relations with Sweden and others.

Delivering such a close relationship will also be in the interests of the Swedish economy. At the moment there are few barriers to UK-Sweden trade, and two-way economic exchange has been flourishing. This will inevitably be affected by Brexit, as numerous studies such as that by the National Board of Trade have shown. Such studies have identified the many individual issues that will face individual sectors.

There are however major cross-cutting issues for trade that, if given priority, will alleviate key Brexit concerns for business. These come in areas such as the UK’s participation in Europe’s single standard model, mutual recognition of conformity assessment testing, and data adequacy. In some cases the regulation is national, such as in financial services, where domestic changes could help trade continue to flow.

The EU’s response to Brexit will help define, and be defined by, the EU’s future development. Is this to be a Europe espousing openness to trade and continuing to develop the most advanced single market in the world, or a Europe retreating to fortress EU, where complete adherence to EU regulations is a pre-requisite to any sense of openness? The EU without the UK will be a different organisation, and countries such as Sweden will have to step up to protect their interests. In short, the future relationship with the UK could also define the future of the EU.

Introduction

This report discusses future economic and business relations between the UK, EU and Sweden, post-Brexit, in the context of developments in the EU[1]. Much has been written about Brexit, about the likely impacts and short term options, but there have been few studies taking a longer term view. For the departure of the UK from the EU will lead to changes:

- For Sweden, on top of potential new barriers to trade the loss of a major ally at the European Council means Brexit will lead to reduced ability to influence the EU in a liberal direction in terms of trade, regulation and other matters;

- For the UK, the loss of trade opportunities with the EU will be felt, and it will no longer be able to influence the direction of policy with its closest economic ally;

- For the EU the departure of one of the largest Member States will affect the balance of power, in particular affecting the trade and competitiveness agenda.

Any serious consideration of the future must consider these factors together. The EU has made progress on the trade and single market agendas. At this stage, however, it seems it will be difficult to sustain this progress between 2019 and 2024: protectionist forces growing and the global political weather conditions are giving more power to inward-looking and interventionist policies. This in turn will have an impact on the development of EU-UK relations. A more closed EU will be less inclined to reach a comprehensive agreement with the UK to maintain significant trading links, bolstering those in the UK favouring a more decisive break with the EU. Moreover a closed EU will also be further from meeting the objectives of Sweden or other countries associated with a similar agenda.

This is the context we shall examine further below. The main argument of the paper is that countries like Sweden – economies that depend on openness to trade, competition and innovation – have incentives to provide leadership for establishing strong and mutually beneficial economic arrangements between the EU and the UK. While Sweden, like other EU countries, have watched the Brexit process with a growing sense of unease, it now needs to come up with a political strategy for resolving bilateral trade and regulatory problems, and keeping the UK a close economic ally whose economic assets remain plugged into the wider European economy. And on the UK side, there is an urgent need to again build strong political relations with governments in Europe that want to progress an open and dynamic Europe.

The report is structured as follows:

Chapter 2 sets the context in terms of Brexit and alternative future models, providing a short overview of the proposed UK-EU relationship, and the possible alternatives, including consideration of ‘the Brussels effect’ where EU regulations tend to have impact beyond physical boundaries;

Chapter 3 examines UK-Sweden relations politically, and in more detail trade links. This section identifies in particular the main horizontal issues that we will need to tackle to maintain strong trade relations, which are considered in detail in the Annex;

Chapter 4 considers the future development of the EU, using as a particular frame the competitiveness agenda that Sweden and the UK were so influential in advancing together with other countries. The section will consider future scenarios for the development of the EU in terms of what these could mean for the future of UK-Sweden relations;

Chapter 5 proposes ways in which we can maintain close UK – Sweden / EU ties, looking at the drivers of the UK-EU relationship from each side’s point of view, and the role Sweden can play;

Chapter 6 provides a conclusion and recommendations.

[1] An early version of this paper was presented at a conference in Stockholm in December 2018

Brexit and models for the future

The discussion about future UK-EU relations has largely evolved on the basis of the Brexit negotiations between the parties. Although the EU has frequently said that these are discussions about the divorce, not the future, in reality talks have covered both issues interchangeably, not least on the issue of the Irish backstop.

We therefore start this chapter by focusing on the impact of the agreement unveiled by the UK and EU in November 2018, then move on to looking at other potential models.

Future UK-EU relations and the Brexit agreement

If the UK and EU agree to the Withdrawal Agreement[1] as drafted, the UK will leave the EU on 29 March to enter a ‘Transition Period’ during which to all intents and purposes it will be treated as an EU member state, with the exception of representation. This period will last until the end of 2020 but could be extended, potentially to the end of 2022[2]. The impact of this will be to allow for the continuation of the existing trading relationship until this time.

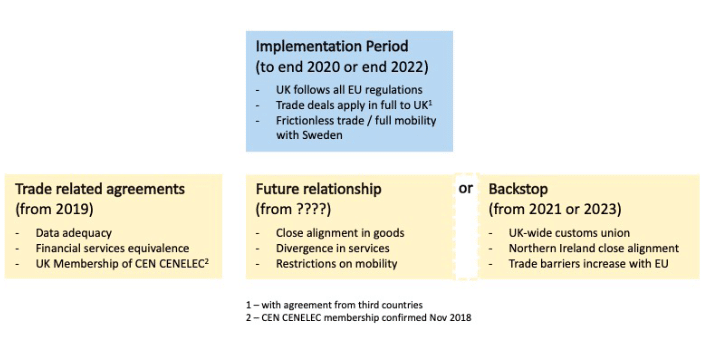

Thereafter as illustrated below either a new relationship will commence, on which negotiations have not commenced, or we will enter the ‘backstop’ designed to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland[3]. Judging by the Political Declaration these will be accompanied by other agreements such as on data adequacy.

Chart 1: Overview of future UK-EU relationship

In the case of the backstop, Article 6 of the Protocol on Ireland / Northern Ireland within the Withdrawal Agreement says: “The Joint Committee shall adopt before 1 July 2020 the detailed rules relating to trade in goods between the two parts of the single customs territory for the implementation of this paragraph.” The reality is that agreeing detailed relations will be complex particularly with regard to differences between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. Thus for example if companies based in Northern Ireland have to have products tested for the EU market, can this happen on the territory, which notified body will be involved, and could a UK based company based in England take advantage of such relations? Issues such as these will take time to resolve.

The future relationship will be negotiated on the basis of the Political Declaration, but there is considerable ambiguity within this document. It is likely that several years of negotiation will be required, along the lines of previous EU deals with Canada and Japan. Equally, the known issues which have hampered negotiations so far will continue to apply. These are best illustrated by the Northern Ireland question, where there are currently no alternatives to a close relationship on customs and regulatory issues to avoid a border either in the Irish Sea or on the island of Ireland, where such a border would affect the delicate peace established by the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. However this issue is also symbolic of a larger incompatibility, namely that the UK seeks a close economic relationship with the EU but rejects any of the existing models.

Potential future relationship models

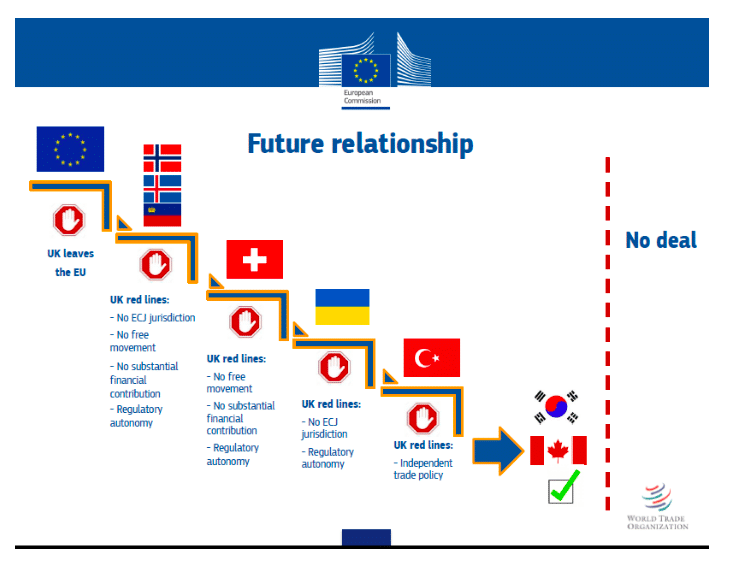

The EU’s Chief Brexit Negotiator, Michel Barnier, has frequently deployed the ‘waterfall’ picture (below) to illustrate the future UK-EU relationship, concluding that the answer is a Canada style Free Trade Agreement. This however does not resolve the Northern Ireland issue, and does not necessarily provide the template for the kind of close relationship that in reality geography and business would suggest.

Chart 2: Models of future UK-EU relationship (aka Barnier’s waterfall)

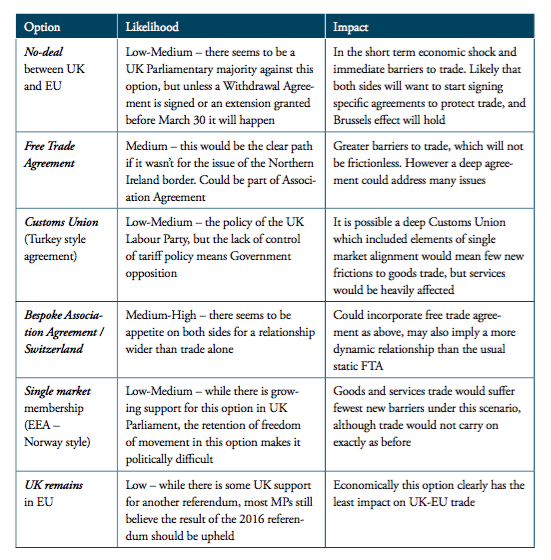

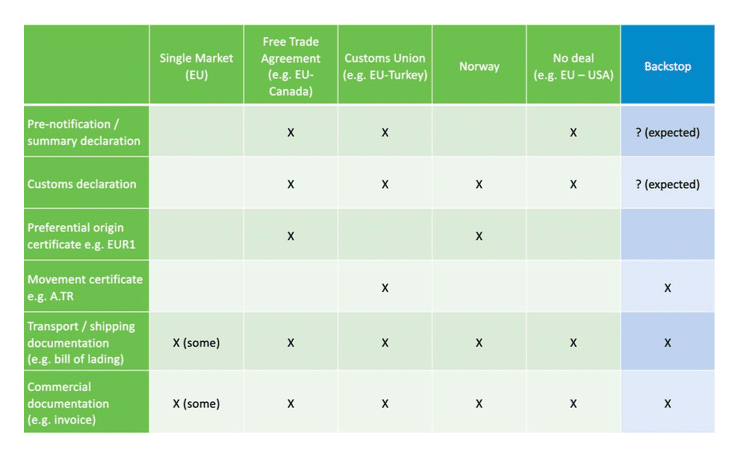

The table below examines in more detail the models identified by the Barnier ‘waterfall’ picture, noting that it may be some time before we are clear of the outcome, and that the backstop could therefore persist for a number of years:

Table 1: Potential Models for future UK-EU relationship

It is worth noting that in all cases except the UK retaining full membership of the EU, there will be a loss of UK influence in rule making, that is the UK will become to a degree a rule-taker (there is of course some consultation for EEA members). This is an inevitable consequence of leaving the EU and the Brussels effect described below, although the UK will have greater scope for independence in some areas of regulation. This is one of the most consequential impacts of the UK leaving the EU.

A further factor that applies to all except the last option is continued uncertainty. It is unclear when the relevant decisions affecting trade will be taken, and in the case of a free trade agreement these could take some years. This is to a degree inevitable, but it would be good for policy makers on all sides to acknowledge this issue and help companies to manage uncertainty, for instance by setting out clear and realistic views of what type of future arrangement that they will seek.

The Brussels Effect and the case for close cooperation

Britain will be affected by EU regulation also after its departure. This is due to the so-called ‘Brussels effect’. A term coined by Professor Anu Bradford, it holds that, regardless the discussion about models, UK businesses will be substantially regulated by Brussels in the future simply because the EU is a big market. In the first instance, companies will have to keep following EU law after Brexit in order to keep trading with the bloc. But what is equally important is that ´the Brussels Effect’ will encourage companies to choose EU rules also as their global standard rather than adopting different regulations for domestic markets. It is often too complicated, and costly, to produce for a variety of standards and, says Prof. Bradford, “for all the talk of the EU economic model being in trouble, the ‘Brussels effect’ is getting stronger.[4]” The EU has become a global power of regulation and in many sectors countries chose to use the EU standard for all global sales. For instance, the US’s Dow Chemical Company in effect complies with EU regulations in its global business.

Consider some basic metrics of UK trade. Close to 50% of the UK’s trade is with the EU, and at least 50% of the population are likely to support close economic relations with the bloc. On top of ‘the Brussels effect’, this implies that the UK will have a continuing close relationships with the EU in terms of regulations. Consequently, it should be in the economic interest of the UK to choose a model including close regulatory cooperation, not least because it benefits substantially from a solution where UK products will be easily approved for being in compliance with standards that businesses will follow anyway. However, the absence of clarity about the future direction of the negotiations has caused substantial uncertainty about the future terms of market access. While this remains such a political question in both UK and EU, there is a risk of short-term disruption, even if both parties acknowledge the economic benefits of a close relationship.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/withdrawal-agreement-and-political-declaration

[2] In the event of a delay to Brexit it is unclear if these dates will be changed

[3] Unless either the whole UK or Northern Ireland alone are aligned to EU Customs and Regulatory policies, EU rules require checks at the border.

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/7059dbf8-a82a-11e7-ab66-21cc87a2edde

Sweden-UK trade and political relations

Where do bilateral Sweden-UK relations fit into the picture? The two countries have for many years maintained close economic and political relations, bilaterally and through the EU. The UK’s vote for Brexit has disrupted these relations, and they will take time to recover. The scale of the damage will also depend on what each country decides about the future. It is certainly possible to limit the negative effects of Brexit by purposeful efforts on both sides to build new forms of collaboration, directly and indirectly through the EU.

While the UK’s exit from the EU will lead to changes, there should be mutual benefit in retaining close political and economic relations. The predominant political culture in both countries continues to be aligned in support of open, well-regulated markets, trade, and international cooperation. Whatever the shape of the future relation between the EU and the UK, there are several reasons – such as geography and ‘the Brussels effect’ – why all sides will have strong interests in maintaining close economic ties.

This chapter will predominantly consider the changes to trading relations likely as a result of Brexit, but will commence with a brief discussion of political relations, which will be built upon in Chapter 5.

Political relations

The UK and Sweden have been united on numerous issues within the EU, in particular in the competitiveness agenda. For example on trade policy, the development of the single market, and ensuring good regulatory practice within the European Commission they have consistently worked together. The departure of the UK will change this relationship, and indeed the dynamics of the EU. However, although the incentives to cooperate will change, there will still be benefits to both countries in maintaining close political links. As political relations have grown cold during the past years, both sides will need to make new efforts in building political intimacy, and the UK in particular needs to craft a policy and strategy for post-Brexit relations with European partners. While there is already a very tight relation in matters like student exchange and commerce, it is notable how few connections that Britain’s two main political parties have with Sweden. Brexit negotiations have exacerbated notions that it is only the big EU member states that matter – and, consequently, that the UK should prioritise them. However, the best chance for the UK to influence the future direction of the EU will come though building a strong rapport with countries who share the belief in openness to trade and better competitiveness, and that are willing to invest their limited political capital to that effect.

The UK has become increasingly politically insular in the last two years, and as a result has frequently not considered the trading issues and how they relate to partners like Sweden. Although UK Ministers and officials have travelled extensively through the EU, much of recent diplomacy has been transactional, with regard to specific UK’s needs in an EU negotiation. There have been times when the UK has given the impression of not needing friends after Brexit, which is surely not correct.

For Sweden, the incentives to cooperate with the UK will also change. In the first place, the UK is an important market for Swedish trade and commercial exchange. Defending current commerce and building opportunities for new trade will require more effort from Sweden, both from the government and from business. Moreover, if Sweden wants to keep the UK as a source of energy in European politics, it will have to build up attendant structures for it. Rather than being a leader within the EU, the UK will soon be requesting information from EU members and will be looking for bilateral partners to channel their ambitions for an open and competitive Europe. Sweden is one of the leading candidates.

Economic relations

There have been numerous detailed studies of the issues that will face businesses trading between the UK and the EU after Brexit, with one of the most detailed being produced by the National Board of Trade. According to this study, “in 2016, the UK was the sixth largest export market and the fifth largest import market for Sweden’s trade in goods. The UK was the third-largest market for Sweden’s exports of services in 2016 and the largest market for imports of services.” Sweden is not quite as important for the UK’s trade, but remains the UK’s 8th largest export market of EU Member States, and among non-EU trade partners is only exceeded by USA, China, and Japan .

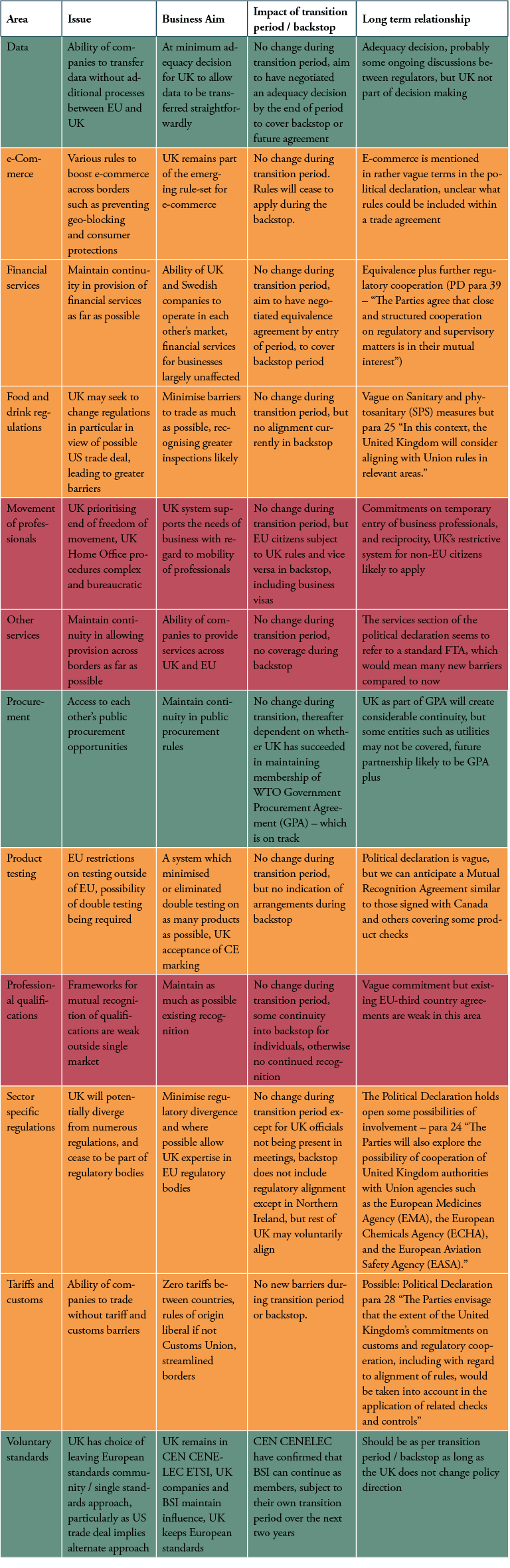

Typically, post-Brexit studies have taken a sectoral focus, and focused on the problems likely to be caused by Brexit. We have taken a more cross-cutting look at issues likely to be faced by Swedish businesses, and looked at the likely impacts in the different models of future relationship previously discussed. These issues and the impact of different economic models are described in the Annex, and summarised in the table below.

The issues selected are data transfers, e-commerce, financial services, food and drink regulations, movement of professionals, other services, procurement, product testing, professional qualifications, sector specific regulations, tariffs and customs, and voluntary standards. What we particularly find when examining these is that, in the event of the UK and EU agreeing a Withdrawal Agreement and transition period, little would change in the short-term, but that business face potentially multiple changes from the introduction of a backstop relationship, followed by the future relationship. Originally, Brexit talks aimed at avoiding multiple transitions, which might not be achieved. In the case of no-deal there would be immediate business issues in most of these areas.

Table 2: Summary of cross-cutting business issues affected by Brexit

Longer term Sweden-UK business priorities

The provision of services and movement of people currently appear to be the biggest potential problems in the future UK-Sweden relationship. This is particularly true in the event that there is a standard trade agreement signed between the EU and the UK. EU Free Trade Agreements have become increasingly sophisticated in terms of trade in goods, but on services fall far short of the provisions in the single market. The mutual recognition of professional qualifications are put into a framework where specific agreements can be made later, and the Political Declaration only mentions short term business visits. The UK process for handling longer term business visas is well known as inefficient, expensive, time-consuming, and generally hostile to business and individuals. Sweden has a clear interest in ensuring better access to business visas than what is generally offered by the UK to third countries. Sweden’s unpredictable system for foreign labour from third countries that are based in the country over a longer period of time is also a source of concern for future bilateral relations.

Should the UK and EU be in discussions for a Free Trade Agreement there is a further complication of existing trade agreements which the EU would have to improve if the UK got a better deal, for example with Canada. For some, this makes it difficult to envisage the UK being offered a substantially better deal. However, it shouldn’t be the case. First, services trade between the EU and the UK is profoundly different from services trade between the EU and Canada – in scope as well as profile. The EU is far more dependent on access to the UK services economy, both for exports and imports, and its own economic interest suggest that an agreement on services with the UK cannot be a replica of the agreement on services with Canada. Second, in the services sectors that will need a better framework than a standard FTA, Canadian exporters aren’t a substitution for the UK providers. Extending direct market-access openings to Canada aren’t going to have much effect on Canada’s export of services to the EU.

A more important problem is how the EU and the UK can find the technical solutions that are required – on direct market-access commitments and regulatory standards – for services trade to flourish. There is yet no clear idea how that could be achieved, and the first step would be to examine what the main losses would be through a typical EU FTA approach, and then consider what different type of agreements could do to help that situation[1].

Such an exercise is also needed at the bilateral level between Sweden and the UK. Regulatory changes within Member States could make a difference, and in some sectors these are clearer than in others. For Sweden for example this could include financial services, where there are notable restrictions.

EU directives establish the base conditions for banking regulations in Sweden. These directives, however, are by necessity general and do not go into specific regulatory behaviour; there is far too much variance in the regulatory tradition and setup of financial services in Europe for a detailed EU-wide approach to be possible. Furthermore, the directives aim to establish the necessary conditions for the single market and only tangentially address what applies to ‘third countries’.

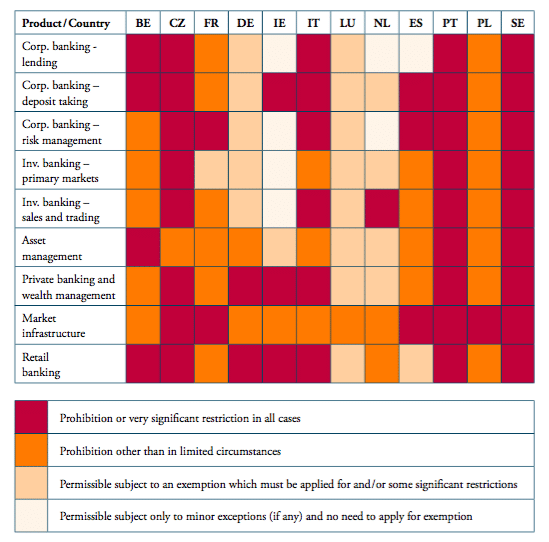

Much of the real market access in EU countries for banking services from ‘third countries’ are addressed through national licensing regimes, which vary substantially in Europe. Sweden is one of the most closed markets in Europe for banking services from ‘third countries’ as illustrated below.

Table 3: The difference between a subset of the EU membership for a variety of professional banking services.

Many of the other issues discussed above will be the subject of significant debate during future relationship talks. One way in which the private sector – also at the national level – can assist is in ensuring that their own bodies allow the participation of the UK as a non-member. There are many such bodies, some of which play a quasi-formal role in EU regulations. The example of CEN CENELEC is instructive, in that they appear to have recognised the benefit in the UK staying as members, even though it was not obvious this would be allowed by the rules. The Annex contains further information on this subject.

Immediate business priority – reducing uncertainty

The immediate issue business face is uncertainty. At the time of writing, no one knows if trade between the UK and EU will be unaffected or completely changed after March as the result of a Brexit with no deal. Even if there is Brexit with a deal, while negotiations on the future relationship are ongoing, the detailed outcomes (and the level of trade friction) will still be uncertain.

This is no basis for future planning – not for business, nor for governments. What makes uncertainty all the more troubling is that the backstop negotiated within the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement is inadequate and cannot support existing trading relationships. Combined with an unrealistic sense of how long a new agreement will take to negotiate, there is a very real possibility of a cliff edge in 2020 or 2022. While this is not in the interest of EU and UK business, and while some problem can be mitigated by smaller agreements such as on data adequacy and financial services equivalence, the simple fact is that uncertainty dominates.

Obviously, it should be a major priority to ensure greater predictability in the entire Brexit process and that future arrangements deliver greater certainty to business. This would mean in particular encouraging both sides to set a realistic timetable for the transition period, that allow a proper transition to the new arrangements. The last two years have set a very bad example in terms of uncertainty. Continuing in this way will inflict real damage on economies across Europe.

A case in point regards EU trade agreements with third countries and the process of the UK departure from them. During the transition period, or a backstop, the UK will be subject to EU tariffs, and UK products will continue to count towards EU content for rules of origin purposes. However, it is not clear whether UK firms will be able to benefit directly from all EU trade agreements in this period in terms of reduced tariffs or increased access to services compared to WTO terms. Some major trading partners such as Switzerland or Japan have indicated that the UK will continue to form part of the EU as far as they are concerned during a transition period.

During a backstop period however the UK would be reliant on making separate agreements with EU trade partners, to allow UK companies to benefit directly. In the event of no-deal, the UK would need to renegotiate all agreements from scratch, a process which has begun but proved to be slow going[2].

This uncertainty over trade agreements adds to the general Brexit uncertainty, especially for Swedish and other European firms that trades with inputs from the UK.

[1] Such an approach could build on OECD work described here https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2019/02/14/not-fit-for-service-the-future-uk-eu-trading-relationship/

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/c44581c2-1a75-11e9-9e64-d150b3105d21

The Future Development of the EU

In March 2011 the Prime Ministers of the UK and Sweden, along with those from Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, wrote to then European Council President Van Rompuy calling for a new direction in economic policy, prioritising completing the single market, unlocking the benefits of trade, reducing the costs of doing business, and making Europe the number one region for innovation. This was accompanied by a pamphlet translated into a number of EU languages.

This work, in which the UK and Sweden were prominent, was successful in many aspects. On trade, although conclusion of the Doha round already looked unlikely in 2011, agreements have been concluded with Japan, Canada, Singapore, and Vietnam, as has an update with Mexico, and talks started with Australia and New Zealand. There has been progress on the Digital Single Market, not least in terms of content portability and the abolition of mobile roaming charges. The EU’s Better Regulation agenda under Vice President Frans Timmermans has improved consultation and sought, perhaps as yet without enough results, to tackle an overly-bureaucratic culture. In terms of innovation the main aim was the creation of a Unitary Patent & Unified Patent Court, which is due to come into force in the first half of 2019.

Clearly some of the agenda was less successful, for example the UK and Swedish governments worked hard to bring TTIP to successful conclusion but were not able to overcome fundamental challenges, though some of the regulatory agenda is still being pursued. Nonetheless the direction of travel was positive and reflective of good joint working. The challenge will be maintaining such an agenda in the new Commission.

The challenge – Maintaining competitive Europe

There are few signs at the moment of a similar competitiveness agenda gaining traction within the EU for the period 2019 – 2024. Indeed a number of factors seem to have encouraged a more defensive or protectionist view of the EU’s future development:

- The departure of the UK and difficulty of a former member state asking for a privileged future relationship;

- The rise of populist governments seeking to challenge the EU, particularly in Italy, Poland and Hungary;

- Continuing challenges over migration from outside the EU, and then movement within;

- Aggressive US trade policy, on tariffs and towards the WTO;

- Unresolved issues around the Euro and monetary union;

- Questions over neighbourhood policy and whether any more new countries should join.

European elections in 2019 and the appointment of a new Commission will take place against this backdrop. It is likely that the new European Parliament will see further swings away from the European People’s Party (EPP) and Socialists & Democrats (S&D) groups, and growth of the far-left and far-right groups. With the EPP and S&D groups also showing signs of increasing nervousness over an open agenda, and the recent example of the move to relax EU antitrust rules and establish more activist industrial policies favouring European or national champions[1], it is unlikely that such an ambitious competitiveness agenda will be delivered in the near future. Indeed we already see backward steps such as the new EU inward investment screening regime.

Nonetheless, although the rise of populism has not predominantly been caused by a lack of growth, there is no question that a slowing economy, remote governments and unequal distribution can play a role. Thus trade policy and continuing development of the single market must be one of the policy responses, however politically difficult this may be. Brexit and a future FTA instead of the current relationship could cause a decline in EU GDP of 0.6% according to one reliable study[2]. By comparison new trade deals with Australia and New Zealand would be likely to deliver negligible economic growth. There is also the continued danger of trade wars and risks to the future of the WTO to account for.

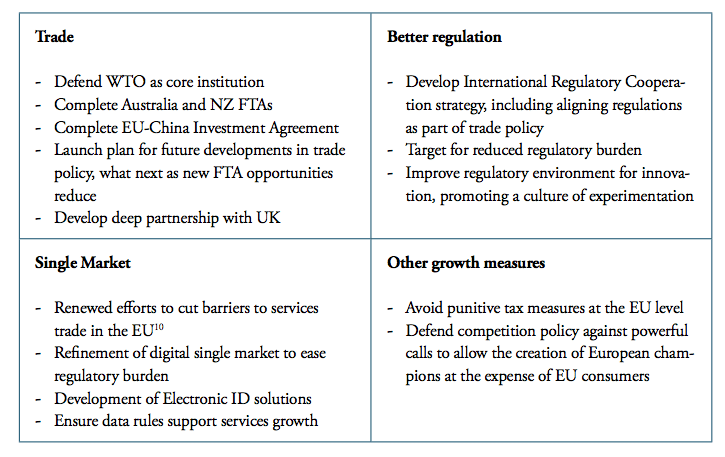

The question then would be what a new competitiveness agenda could look like for the period of 2019 – 2024. Amending the headings used in 2011 slightly, we can start to identify some key targets for this period.

Table 4: Potential EU competitiveness agenda 2019-2024

One interesting factor to consider is whether EU trade deals will be less valuable without the UK as a large market, assuming of course the UK does leave a Customs Union. Certainly this could be the case with major negotiations such as with Mercosur, but not be such a factor with the likes of New Zealand and Australia. However in all three cases the strong agricultural interests of the other party may be a barrier to reaching agreement. The future trajectory of EU trade policy, given the success in signing Free Trade Agreements, needs further discussion, as it is unclear what the next steps should be.

Political balance in the EU

The departure of the UK will make a big difference to the political balance of the EU. Even if the full consequences are yet unknown, the political fallout should already be causing concern to those countries pushing for more open policies in the EU. Without the support of Germany it is now unlikely that such countries will be a blocking minority, and the impetus for new trade agreements and further single market reforms is likely to be reduced.

The formation of the “New Hanseatic League” by 8 EU countries[4] has been seen as an attempt to maintain impetus for the competitive agenda, although thus far it has mostly focused on fiscal policy and the completion of the Capital Markets Union. However this was enough to provoke a response from the French Government, describing their opposition to clubs within the EU[5].

There has been a suggestion that the Commission would in fact provide a counterweight to what is likely to be a more cautious Franco-German spine to the EU in future years. However, although the Commission is institutionally well regarded to trade and single market deepening, it is not a substitute for member-state leadership and has to balance the wishes of all member states. Like all other government-like entities, the Commission is not a singular unity with one set of beliefs and one agenda of priorities; it has many fractions and power bases, many of whom are competing to set the policy agenda.

There is an expectation, both within the EU and among other countries, that Sweden will be one of the countries spearheading the openness and competitiveness agenda, along with the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland in particular. Indeed there have been comments to suggest some surprise that the Swedish Government has been quiet in Brexit talks, perhaps because it was not completely clear what the optimal Swedish position should be.

Building on the UK-Sweden trade section above, and next section discussing wider political relations between the EU and UK, we believe that Sweden can have a clear road map of priorities for the EU’s competitiveness agenda. However, the difficulty will come in being able, as a smaller EU state, to turn these priorities into a sense of direction. It will be important for the Swedish government to work with other like-minded countries and ensure there is always a voice for these priorities in meetings.

The impact of the UK’s departure may not be evident until the formation of the new Commission and the plans they start to put in place. Given the pivotal nature of this, it would be advisable for countries advocating a continuing competitive Europe to ensure they have clear proposals ready to be taken forward from late 2019.

[1] https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/19-eu-countries-call-for-new-antitrust-rules-to-create-european-champions/

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/6d00353c-2616-11e8-b27e-cc62a39d57a0

[3] https://dbei.gov.ie/en/Publications/Publication-files/Copenhagen-Economics-Making-EU-trade-in-services-work-for-all.pdf

[4] Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Netherlands, Ireland. The continuity of countries that also signed “Let’s Choose Growth” is worthy of note.

[5] https://www.ft.com/content/d47c60cc-ef20-11e8-8180-9cf212677a57?emailId=5bfad2f217a34c00049cc5db&segmentId=488e9a50-190e-700c-cc1c-6a339da99cab

Maintaining close ties

Will there be a close UK-EU relationship?

The proposed Political Declaration between the UK and EU is ambiguous about the nature of the future relationship. In the opening paragraphs there is a clear statement of intent, suggesting that “this declaration establishes the parameters of an ambitious, broad, deep and flexible partnership across trade and economic cooperation, law enforcement and criminal justice, foreign policy, security and defence and wider areas of cooperation.” This is not sustained throughout the document however, with a later paragraph saying: “The Parties envisage that the extent of the United Kingdom’s commitments on customs and regulatory cooperation, including with regard to alignment of rules, would be taken into account in the application of related checks and controls, considering this as a factor in reducing risk.”

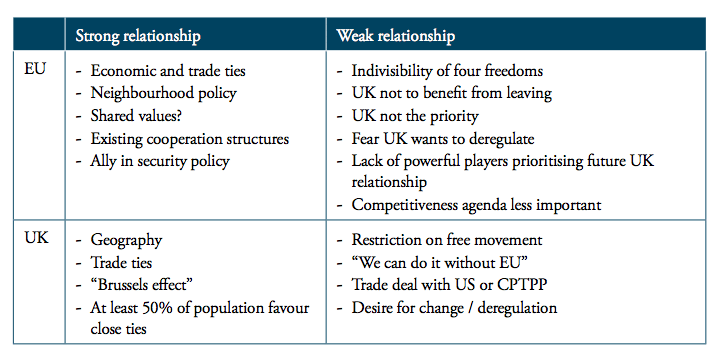

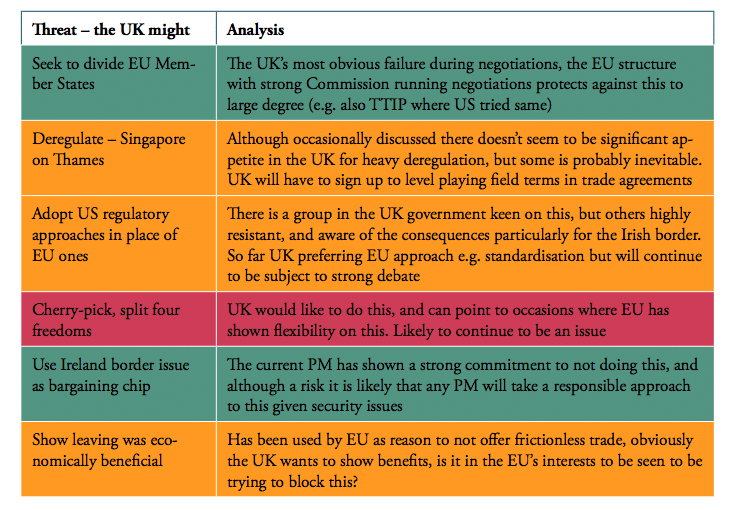

In truth, there are strong forces for and against a future close relationship. In the UK, these forces are relatively balanced, but in the case of the EU the stronger position seems to be in support of a weaker relationship. The table below summarises this, and illustrates why we cannot take a future close relationship for granted.

Table 5: Arguments in favour of strong or weak relationship

Trade ties are important for both sides. However, in both the EU and UK political factors act against the economic factors that would suggest a close relationship, and in the case of the EU these could easily tilt the balance of debate. A hard-bargaining approach from the EU is likely to be met with the same from the UK, risking a deterioration in relations. This is especially the case as the UK’s asks currently are rather transactional, focusing only on trade, whereas the EU has more of a balanced picture of hoping for but also slightly fearing wider cooperation.

The trade agreement with the UK is likely to be the most important in terms of economic and political value to be negotiated by the next Commission. A relatively closed approach to the UK will have an effect on other negotiations. There is a need for those with an interest in a different outcome to act to make this happen.

The UK Approach to future relations

The UK Government, Parliament and other institutions still do not seem to have come to terms with what leaving the EU actually entails. As a consequence, it has been difficult to get to a point where we get clarity rather than confusion about exactly what type of the relation with the EU that the UK will seek. During the last two years there have been regular references from Cabinet Ministers to, for example, attending post-Brexit council meetings in different capacities, having an easy trade deal as we will start from the same regulations, the EU needing the UK more than vice-versa on financial services, and using our security capabilities to get a good trade deal. All these propositions are missing the essential truth that a non-member will have little influence in EU decision making and that the starting point for the EU in a negotiation with any third country is the existing models of EU relationships with third parties.

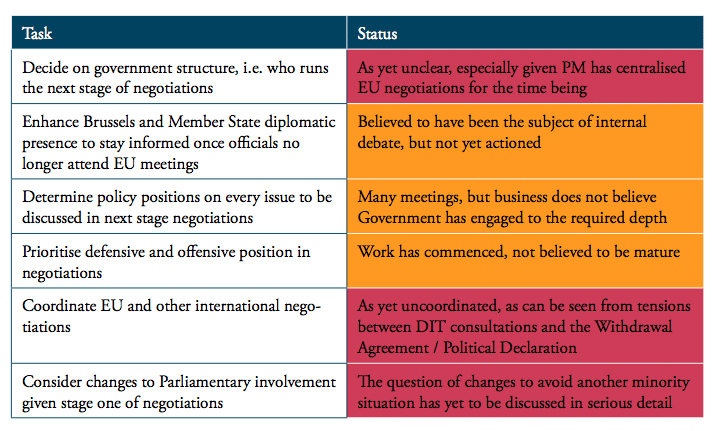

Negotiations on the future UK-EU relationship should start soon after the UK’s formal exit from the EU at the end of March. This however will require both sides to be prepared, and in the case of the UK we see that current political difficulties and the need to prepare for a no-deal Brexit mean that the UK is simply not preparing also for imminent negotiations. As the table below shows, there is little clarity on the most significant questions the UK Government must answer:

Table 6: Key UK decisions required ahead of future EU negotiations

The Brussels effect discussed earlier suggests that UK business will lobby the UK Government strongly to maintain a relatively close future relationship with the EU, for example in terms of regulatory alignment. Such close alignment will also have substantial public support. In terms of day-to-day government decisions this is likely to produce a bias towards a close relationship, as we have already seen[1].

We have also seen that the EU debate within the UK is not fully determined on economic grounds, that sovereignty has also been a significant issue. There is already a popular narrative in the UK that the EU has punished the UK for leaving in the negotiations to date, and this narrative could become more widespread in the future given that we know trade negotiations are often divisive. Thus we can expect a continued tension within the UK of wanting a close trading relationship, while rejecting the Commission’s existing models to achieve this.

A further complicating factor is that the UK government will also be wanting to pursue a ‘Global Britain’ agenda[2], including a trade deal with the USA or joining CPTPP – either of which will threaten alignment with EU regulations. There is a degree of awareness in the UK that this may not be compatible, but further debate is inevitable, which will interact with the EU-UK talks. The bottom line is that there is no shared understanding in the UK polity about its future foreign economic policy and relations. The negotiations with the EU over the future relationship will likely be happening in a context of political ambiguity and vexed discussions about the costs and benefits of alternative courses of actions.

The EU approach to the UK

It is natural for other EU members to be sore about the UK’s departure: it is a serious blow to the European project. There has been an element of denial in the EU’s response to the departure of the UK, essentially that the EU will be fine and the UK will suffer. In the short term, that is what has happened, certainly politically. But just as the UK cannot escape geographical reality, neither can the EU. The UK is a neighbour and two-way integration is strong in virtually all areas of policy. Consequently, there should also be a debate in the EU about what the future relationship should look like.

The EU has some sort of formal relationship with every neighbouring country, and there are several models for cooperation. Many neighbours are accession countries, some are part of EFTA, while others are covered by the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which “aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer, to their mutual benefit and interest[3].” However, it is not yet clear that the relationship with the UK will fit into any existing category. Nor is it obvious that the existing models would serve European interests, commercial as well as political. While it could rational to seek an agreement with the UK that is different from existing models, the EU suspects that the UK is attempting to craft a new relationship that includes the benefits but excludes the cost of EU membership.

Threats to the EU from the UK’s Brexit have been often mentioned, but less often subject to serious analysis. When such an analysis is carried out we can see that EU fears are not without merit, certainly the UK does want to split the four freedoms, as others have done before, and regulatory divergence remains distinctly possible. On the other hand UK efforts to divide EU member states have failed badly.

Table 7: Analysis of UK threats to the EU

This analysis strengthens the view that there will be tensions in the approach to the future UK relationship just as significant as those on the UK side. Similar to the UK the tension will be between the political imperatives, in maintaining the indivisibility of the four freedoms and showing that being a member also delivers economic benefits, and the economic and other benefits of retaining close ties. To add to the EU’s challenge, adopting a hard line approach to UK asks may also help to bring about some of the scenarios that are most feared, such as a deregulatory UK economy and financial services centre next to the EU. On balance, while being suspicious of UK desires to take all the benefits without any of the costs of membership, the EU would benefit if it starts with this appraisal of its own interests and how they could be attended in a future arrangement, rather than attempting to shoehorn an existing approach to another third country.

Formalising a future relationship

During the Brexit talks to date there have been a small number of serious proposals as to how the future EU-UK relationship could be structured. Former MEP Andrew Duff has persistently advanced the case for an Association Agreement model[4] as being in the case of both the EU and UK. As he writes

“It is absolutely in Europe’s interest to hug Britain as close as possible. In its present unreformed condition, poised uneasily as it is between the confederal and federal, the Union would not be insulated from damage wrought by a belligerent, nationalistic Britain sulking 40 kilometres off Calais. The EU’s immediate interest lies in keeping the British within its regulatory orbit. The EU’s long-term strategy must be to return with more confidence to its historic mission of promoting the ever closer union of the peoples of Europe – not excluding the British peoples. For everyone’s sake, the United Kingdom is better half in than right out of Europe.”

Ferry et al[5] see a similar need to keep the UK close but in a more ambitious “Continental Partnership” with the aim “to sustain deep economic integration, fully participating in goods, services, capital mobility and some temporary labour mobility, but excluding freedom of movement of workers and political integration.” This would become an outer tier of the European integration project, with the potential to also include current EEA members and other potential new joiners such as Ukraine.

The UK Government’s ‘Chequers’ proposals published in July 2018[6] essentially proposed a balance between Turkey, Canada, and Norway relationships, with shared rules on goods trade, a customs arrangement allowing the UK to make trade deals while still having frictionless trade with the EU, but less alignment in services. While the customs element of this was never acceptable to the EU, the paper did help to inform the discussions which led to the Political Declaration.

These proposals all share the view that the future relationship with the UK is an opportunity to define a wider ‘Europe’ outside of the EU, continuing to bind economies relatively tightly in a dynamic arrangement but with enough leeway for countries who don’t wish to be part of political union. The possibility of such an arrangement with the UK has always been problematic to the Commission, anxious to avoid the complex web of agreements that make up the Switzerland agreement, seen to also allow particular privileges for the Swiss. Yet the EU’s third party relations typically do consist of a number of agreements in different subjects with each country, often underpinned by one overall agreement.

A structure of an overall agreement that can be enhanced over time by specific cooperation in different fields would allow both sides breathing space to re-establish a beneficial mutual relationship, as well as ensured continued cooperation on the island of Ireland. Such a structure is compatible with the Political Declaration, which already references specific agreements that could be reached. Thus for example the UK and EU can start to reach agreement such as:

- Data adequacy;

- Financial services equivalence;

- Recognition of Authorised Economic Operators;

- UK membership of the Pan European Mediterranean convention on Rules of Origin, mentioned above in Section 4;

- Conformity Assessment Testing, such as the Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance (ACAA) of Industrial Products between the EU and Ukraine / Israel

- Agreement on Supply Chain security such as that with Canada;

Sweden and other like-minded countries should be able to help in facilitating a mutually beneficial model such as that outlined above. Particularly as there is an alternate model, which we can think of as “Fortress EU” where the departure of the UK is seen as a possible forerunner to the departure of others such as Hungary or Poland, and the essence of the EU is defined as protecting the four freedoms and ensuring a member who departs must not benefit. In this version the likely relation with the UK is legalistic and largely static, based on a Free Trade Agreement model.

The UK relationship presents the chance for the EU to formalise a new model of external relations. This would be aligned with an open approach, in ensuring that many institutions are not just open to EU members, but are genuinely Europe wide.

The future UK-Sweden relationship

The Brexit process has not been a comfortable one for those countries who were formerly close to the UK on issues such as trade and competitiveness, particularly given losing their most consistent large Member State ally. It is understandable that there has been a strong wish that the UK changes its mind and remain in the EU. However, while countries like Sweden has been focusing at trying to help business to understand the practical consequences of Brexit, many countries have neglected to form their own opinion about what arrangement they would like to have with the UK in the future. The model described above should hopefully help to answer this question.

The UK government have also appeared careless at times with close relationships such as those with Sweden. Little thought seems to have been given to these relationships after Brexit, specific questions have received curt replies, and the UK’s hope that Member States might support them over the EU seen as naïve at best. The Brexit process and its outcome therefore risk permanent damage to the UK-Sweden relationship.

Once the UK Parliament has confirmed the terms of withdrawal from the EU, it will be important that the UK and Sweden seek to rebuild their previous relationship and repurpose for a new time and context. In the matter of close relations with non-EU members, Sweden has prior experience and can help significantly so long as the UK is receptive. As long as the UK does not expect any country to choose them over the EU, this experience could be used to help the UK to define and navigate their new status. There will of course be other countries who could be in a position to help, not least Ireland and the Netherlands, but Sweden has unique experience to bring about close future economic relations.

Assuming the UK will be open to such dialogue, there are other areas where it should be able to provide reciprocation outside of the oft-discussed security relationship. In taking up an independent space at the WTO, the UK should be party to more discussions about trade liberalisation, and be able to discuss these with those in the EU who favour such policies. Here it should be recalled that Sweden are one of the few countries in the EU to show their commitment in having a full time Ambassador to the WTO, and this role has in the past been active in pushing new initiatives on green goods and trade in services among others. The UK’s regulatory experiences once outside the EU are also likely to provide an interesting source of discussion.

There are also institutions which could help. The Nordic Council is an existing body with EU and non-EU members included, and has taken on policy questions such as the 2017 declaration on digital policy[7]. Another example is the Northern Future Forum, established on the suggestion of former Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt in 2010, and first meeting in 2011. Bringing together the UK along with countries of the Nordic-Baltic region, there was no annual meeting in 2016 in 2017, but meetings resumed in 2018.

It is recommend that both the UK government and a new Swedish government should make a priority of deepening such ties with the UK from 2019. UK and Swedish officials have been used to cooperating within the EU, and these personal relations should not be left to gradually decline.

[1] See for example the work by BSI to maintain membership of CEN CENELEC

[2] Though note issues rolling over existing EU trade deals, e.g. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/feb/07/trade-deals-britain-liam-fox-brexit

[3] https://www.euneighbours.eu/en/policy

[4] For example http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_8347_brexit-halfinhalfoutorrightout.pdf?doc_id=1958

[5] http://bruegel.org/2016/08/europe-after-brexit-a-proposal-for-a-continental-partnership/

[6] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/725288/The_future_relationship_between_the_United_Kingdom_and_the_European_Union.pdf

[7] https://www.norden.org/en/declaration/nordic-baltic-region-digital-frontrunner

Conclusion

Brexit has brought challenges to the UK, EU and to individual Member States like Sweden. It has created uncertainty in business, and not just about the future of trading links between the EU and the UK. During the last two years there have been many reports considering the precise impact on business ties, and companies have therefore been considering their contingency plans.

Beyond negotiation of the Withdrawal Agreement there has been little attention on the political dimension of Brexit. Against a backdrop of other global problems such as President Trump’s attacks on the WTO it is important that Brexit isn’t another influence towards closed markets and reduced trade.

Right now this is in the balance. There are forces encouraging a deep split between the EU and UK, and contrary ones pointing towards a retention of strong links. We think that on balance the UK will seek relatively close links, and we hope that the EU will respond positively with an open offer for a dynamic relationship that can form a new EU model for relations with a third country.

Governments and business in both UK and Sweden can help to make this happen:

The UK Government should;

- Provide more clarity on preferences and priorities;

- Recognise the damage of the last two years on close relationships such as that with Sweden, and find ways to work together in the future such as pursuing the multilateral agenda at the WTO;

- Demonstrate realism in their views on future relationships and timescales;

- Consider modifications to the way long-term business visas are handled once EU citizens fall under the Home Office.

The Swedish Government can help through:

- Developing with like-minded countries a new competitiveness agenda;

- Supporting close economic ties and appropriate future structures between EU and UK where there is a strong case for doing so;

- Using their experience with Norway to propose deeper UK-Sweden political ties;

- Examining where regulatory changes at domestic level can help retain ties.

There are also roles for Swedish and UK businesses can play:

- Continue to make the case for close economic relations;

- Ensure that UK companies can be part of Europe-wide bodies;

- Identify the main priority areas for the new UK-EU relationship.

It should be possible to develop the EU competitiveness agenda in tandem with a new UK relationship, to mutual benefit. It will not however be straightforward, and has not been to date. This report suggests with effort on all sides there can be a positive outcome.

Annex – Horizontal Issues

This Annex provides more detail on the horizontal business issues identified in Section 4 of the report. A final part examines one way in which the UK and EU business can help to maintain close relations after Brexit, namely through continued UK membership of EU representative bodies.

Data

Maintaining provisions that allow data to be easily transferred between the EU, UK, and rest of the world is recognised as one of the most important trade issues to be tackled as part of Brexit. UK industry body Tech UK has said “Without a clear legal framework to allow the free flow of personal data, the burdens both on tech businesses and businesses across the whole of our rapidly digitising economy, would be significant.[1]”

There is a clear process through which the EU recognises the adequate level of data protection in other countries, and aical Declaration sets out that the EU will begin the processes of assessing the UK for such an agreement as soon as the UK leaves the EU, with the aim of ensuring adequacy by the time the backstop may come into force.

Simultaneously the UK will also start its own adequacy process, in order to meet commitments under the General Data Protection Regulation, which will be retained in full. This process will declare the EU, and other third countries, adequate for the purposes of sharing data.

In terms of a deeper relationship Tech UK hope that the UK Information Commissioner may be able to engage on the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which ensures a “uniform application of EU rules to avoid the same case potentially being dealt with differently across various jurisdictions.[3]” At present only EU countries are full members, with EEA countries members without voting rights. On this basis the most likely outcome is informal consultation, but no UK membership.

Should the UK leave the EU without an agreement, or an adequacy decision is not reached in time, the Institute for Government in a helpful primer on the subject explain that “transfers of EEA data to the UK after Brexit would only be permitted subject to additional safeguards.[4]” The UK would continue to recognise EU data protection as being adequate though, allowing UK data to be transferred. However there would inevitably be extra costs in this situation, and it is likely that both sides will want to make a data adequacy agreement a priority as soon as politically possible.

E-Commerce

The UK is currently a leader in e-commerce, defined here as business to consumer sales, with over a third of total sales in the EU[5]. E-commerce trade across the EU is governed by numerous regulations, such as those on distance selling, postal services, VAT and geo-blocking, and if the UK does not stay a part of the single market there is no simple solution to avoiding disruption.

The European eCommerce and Omni-Channel Trade Association (EMOTA) has produced one of the more comprehensive guides to the issues surrounding Brexit in this area[6]. Customs, including tax issues, and regulatory alignment in various areas are the two main areas of focus.

Unless there is a particularly close economic relationship after the transition period ends there will be delays in goods being processed at the border compared to today. This will also inevitably add to shipping costs. Similarly the UK will no longer be part of the EU VAT area. For low value consignments under £135 coming into the UK a technology solution should be put in place allowing VAT to be added at point of sale, for goods values above this VAT will be collected once the goods are brought into the UK[7]. However no such special scheme is envisaged by the EU[8], so that standard procedures for goods exported and imported outside the EU must be followed.

In terms of regulations the UK and EU will be aligned after the transition period in key areas like postal services and consumer protection, though EMOTA note that “Certain laws and legal provisions are unlikely to apply to the UK, such as the Injunctions Directive, Online Dispute Resolution and Alternative Dispute Resolution Directive, together with the infrastructure they provide.” It will be useful to maintain dialogue in these areas, to avoid unnecessary divergence. Of more immediate concern in no-deal or after a transition period will be conformity assessment (covered below) and geo-blocking, for the latter the UK Government note that “In a ‘no deal’ scenario, the UK version of the Geo-Blocking Regulation would be repealed. The original EU Regulation will continue to apply to UK businesses operating within the EU, and indeed all other non-EU businesses selling goods and services into the single market.[9]”

It is likely that e-commerce will be one of the areas most directly affected by a no-deal or backstop Brexit. Amazon has already warned UK sellers to move inventory to the EU[10]. This should therefore be an area of horizontal focus in talks about the future relationship.

Financial services

Financial Services are of particular importance to the UK economy. The vote to leave the EU could also have significant implications for the financial services sector across Europe. The degree of inter-linkage between the ‘City’ and the EU economies is substantial, economically speaking, and intricate in terms of the legislative interface[11].

Fortunately the impact of these matters on UK-Sweden trade have been specifically considered in detail by Finansinspektionen (FI) as Sweden’s financial supervisory authority[12]. The scenario considered by FI was one where the UK leaves the Single Market, meaning changes to the way financial services were provided between the UK and EU.

The summary of the report is that “The supply of financial services is expected to largely remain the same for Swedish households and businesses since British firms have announced that they will apply for authorisation within the EU to be able to continue to conduct business.” However there are particular concerns that more than 90 per cent of interest rate derivatives trading in SEK is cleared in London. The concern over derivatives, shared across the EU, has led to the Commission announcing in December 2018 that there would be “A temporary and conditional equivalence decision for a fixed, limited period of 12 months to ensure that there will be no immediate disruption in the central clearing of derivatives[13].”

In the event of a Transition Period the EU expects to start the process of granting UK equivalence in terms of the provision of financial services, with a view to completion by the end of 2020. However according to a briefing by Linklaters “the scope of EU equivalence is limited and patchy[14].” According to FI, due to the narrow EU regulations regarding equivalence, British firms will only be able to conduct very limited business directly from the UK. The extent to which Swedish firms can conduct business in the UK will be dependent on British rules, but there are strong indications that it will be possible to do so through subsidiaries or branches. In practice UK based financial services companies have also been setting up subsidiaries across the EU to mitigate likely market access barriers.

As stated above much of the real market access in EU countries for banking services from ‘third countries’ are addressed through national licensing regimes. These vary substantially in Europe, and Sweden is one of the most closed markets in Europe for banking services from ‘third countries’. Sweden, like every other member of the EU will have to decide for itself the exact regulatory conditions for market access between Sweden and the UK in banking services post Brexit.

Thus in terms of financial services the post-Brexit position will be determined by a combination of Member State and EU level activity. It is likely that in the short term, London will continue to be an important financial services player across the EU.

Food and Drink

Within the UK Brexit debate the future of EU-UK trade in food and drink products has been one of the most prominent. The UK food and drink industry is the largest manufacturer in the country, there is considerable UK-EU trade, and checks for goods coming into the EU are typically more onerous than for any other sector[15]. Food exports from the UK are valued at more than £20bn each year, and 60% of them head to the EU[16]. In the event of no deal being agreed considerable disruption is expected. However even a backstop or Free Trade Agreement would represent considerable barriers compared to the current situation.

The two key issues in this sector are tariffs, and product checks. As is well known, the tariffs on food and drink products are high, for example cheddar cheese faces a tariff of 42%, making trade largely uneconomic outside of reduced rate quotas. The UK and EU are in the process of splitting existing WTO quotas which attract reduced or zero tariffs, however this is with regard to other countries[17]. Should the quotas need to be adjusted for UK-EU trade we can expect a lengthy process, and it is not clear what would happen for a no-deal Brexit at the end of March. These issues would not arise in the backstop or a long-term Customs Union.

The need for product checks is if anything causing more concern if there is a no-deal Brexit at the end of March. A large percentage of UK-EU trade comes via the Dover-Calais route, and neither port is currently designated as a Border Inspection Post, where food imports can be checked. There is a high level of checks for many food related products, and the expectation therefore of severe disruption to trade. This disruption would be reduced by the UK remaining part of the single market after Brexit, or a veterinary agreement[18].

There are numerous other issues which may affect food and drink trade after Brexit, including changes to labels[19], obtaining certifications as approved exporters, trans-shipment for goods coming to and from the EU, and the possible divergence of regulations after Brexit. The latter could become a particular issue should the UK pursue a trade agreement with the US that is likely to involve accepting US rather than EU food standards[20].

Typically many of these issues would be discussed and appropriate procedures put in place as part of a Free Trade Agreement. There has been some discussion of whether all food and drink tariffs would be removed in a UK-EU agreement, and most experts believe this would be the case, unusually in an EU FTA. Alongside procedures to streamline checks we could expect that such an agreement would go a long way to removing barriers to trade, so it is the prospect of no deal in the short term that is particularly worrying.

Movement of Professionals

The UK Government has made it a priority of Brexit talks to restrict freedom of movement after Brexit[21]. Although those from the EU already resident in the UK and vice versa should be protected even under no-deal, there are likely to be significant restrictions on the movement of professionals in any future relationship.

Should the UK and EU sign a Withdrawal Agreement then Freedom of Movement continues under the Transition Period, and under all circumstances between Ireland and the UK under the Common Travel Area. The backstop does not however contain any provisions outside of those pertaining to Ireland, and under no-deal there will similarly be no arrangements.

Without a new agreement being reached business travel will be covered by existing EU and UK rules. Whilst both the EU and UK have ruled out visas for short visits in the event of a no-deal Brexit these will not cover ‘paid work’ for entry to the EU[22]. The UK has announced a new Temporary Leave to Remain scheme, but it is not completely clear whether this apply in all circumstances, for example for regular work visitors[23]. It is likely work visas will be required in the circumstance of no-deal or backstop, in the absence of a new agreement.

Should the UK remain in the Single Market then Freedom of Movement will continue. In the event of a Customs Union or Free Trade Agreement this is unlikely to be the case. The UK’s commitments under the General Agreement on Trade in Services in Mode 4, the temporary movement of natural persons, are limited[24]. In December the Government published a White Paper on migration which envisaged that in the future there would be a “a single skills-based system” for both EU and non-EU, including a willingness “to expand, on a reciprocal basis, our current range of “GATS Mode 4” commitments which we have taken as part of EU trade deals. These commitments may cover independent professionals, contractual service suppliers, intra company transfers and business visitors[25].”

In practice the UK has been restrictive with Mode 4 commitments in the past, even in the EU-Canada agreement it is noted that “the UK is notably restrictive in terms of mode 4 regulations; in CETA the UK registers restrictions in every single mode 4 category that we distinguish.[26]” Given an already complex system and the operation by a Home Office that many businesses have seen as unhelpful, we believe that the UK’s visa system will be the single biggest obstacle to UK-Sweden trade in the future. By comparison the situation in Sweden, for UK workers, is likely to be much more straightforward though the environment can be unpredictable[27].

Other services

Services comprises a number of individual areas, best structured by the OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index[28] into Digital Network, Transport and Distribution, Market Bridging and Supporting Services (legal and professional services for example), and Physical Infrastructure Services. In all of these there will be a significant difference between the barriers encountered under EU Membership, the transition period, or EEA membership, and any other arrangement including a Free Trade Agreement. As Sam Lowe notes in a CER briefing paper “Although barriers to trade in services between member-states exist across most sectors, and the single market for services is not as developed as the single market for goods, it remains the most comprehensive example of multi-country services liberalisation in the world. Indeed, in some areas it has liberalised services trade between its members further than some countries have managed within their own borders. For example, the EU has been much more successful in developing a framework for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications than the US[29].”

Starting with transport and distribution, EU laws in areas like haulage and aviation are extensive, and there will be impacts from any non-EEA Brexit after any transition period. For example the rights of UK-owned haulage and aviation firms will be significantly reduced, with likely knock-on effects to the cost of doing business with the UK. Temporary measures will be put into place by the Commission to cover a no-deal in 2019 scenario[30], but thereafter there are likely to be ongoing negotiations balancing trade with upholding EU laws.

The main issue in the Digital Network cluster is data, covered above, but without further agreements there will be restrictions on broadcasting from the UK across the EU (though UK content can still be considered European), some issues in copyright such as the sharing of orphan works[31], and potentially the return of mobile roaming charges between EU countries and the UK. In any Free Trade Agreement we could expect the EU to implement the usual audio-visual carve-out meaning arrangements in this area would need to be stand-alone.

Issues in the other clusters, covering mainly professional services, will be particularly affected by issues discussed elsewhere under Freedom of Movement and Professional Qualifications. There will be particular difficulties in the field of legal services with a much restricted ability for legal services professionals to work across the EU[32].

The CER study mentioned earlier suggest that services trade between the UK and EU will change substantially, with less supply directly from the UK and EU across-border, and more based on commercial presence in the market (from Mode 1 to Mode 3 in GATS parlance). There are limits to the rights of establishment in the UK and EU but these are less than the new limits on cross-border provision of services, judged on the basis of existing GATS schedules. Negotiations for a new Trade in Services Agreement at the WTO have stalled, but pushing this could be a priority for UK and Swedish Governments.

Procurement

Access to public procurement contracts from EU to UK and vice versa should be one of the least impacted areas of business operations from Brexit. In November 2018 a meeting at the WTO confirmed that the UK’s application to continue membership of the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) in its own right, as opposed to as part of the EU, had been successful[33]. As both the UK and the EU will therefore be part of this agreement companies will still be able to tender for work as they do currently.

There will be some differences between the new and previous procurement regimes. As in other areas these would not come into force until the end of any transition period. Most notably the coverage of the GPA is less than that from being EU members, as an article for law firm Monckton notes “The scope of procurement activities covered under the GPA schedules for the EU (and the UK at present) is, however, narrower than the scope of covered procurement under the EU procurement laws. For example, market coverage access is particularly more limited in terms of below-threshold or private contracts subsidised by government; defence; and utilities[34].”

Procurement notifications will also no longer be published in the EU Official Journal in the case of no-deal or after a transition period. As the Government’s no deal notice states “Contracting authorities have a legal obligation to publish public procurement information. In a no deal scenario, contracting authorities may no longer have access to the EU Publications Office and the online supplement to the Official Journal of the EU dedicated to European public procurement (Tenders Electronic Daily). Therefore the Government will be amending current legislation to instead require UK contracting authorities to publish public procurement notices to a new UK e-notification service[35].”

In the case of the UK remaining in the single market public procurement will remain as per EU membership, however public procurement is not covered in the EU-Turkey Customs Union. In such an agreement or a Free Trade Agreement we would expect that both the UK and EU would be keen to move slightly beyond GPA commitments. However in general this is one of the areas where least action is required for companies doing business between the EU and UK.

Product Testing

The interface between UK and EU conformity assessment procedures in the post-Brexit period is particularly dependent on the exact nature of the UK-EU relationship. There should be no or very limited effective change to trading procedures during any transition period, but outside of this there are four potential trade and conformity assessment pathways:

- UK formally part of a Turkey-style Customs Union or the European Economic Area, in which case we would expect no change in UK or EU conformity assessment procedures for goods traded between the two;

- UK negotiates a Free Trade Agreement with the EU covering conformity assessment, or a stand-alone Mutual Recognition Agreement such as those the EU already has with countries such as Australia and Israel[36]. Such an agreement would set out “the conditions under which one Party (non-member country) will accept conformity assessment results (e.g. testing or certification) performed by the other’s Party (the EU) designated conformity assessment bodies (CABs) to show compliance with the first Party’s (non-member country) requirements and vice versa.” Such an arrangement would however be unlikely to cover all products required to be tested by third parties;

- The UK unilaterally recognises products recognised as passing EU procedures as being safe to import, as is planned in the case of a no-deal Brexit but “intended to be for a time-limited period.[37]”

- There is no recognition of each other’s conformity assessment, for example if there is no-deal in March UK products requiring third party conformity assessment already on sale in the EU must make new arrangements with a Notified Body within the EU[38].

It should be noted that at the moment if the Irish backstop were to come into operation then without any further agreement this would mean pathway 4 would be followed for trade between the EU and Great Britain, as the backstop does not cover conformity assessment. The relationship between the EU and Northern Ireland in this situation is yet to be specified and likely to be complex.

According to the UK Government’s no-deal notice there will be a new UK marking to replace the CE marking for goods placed for sale in the UK. Plans for this new marking are expected in the coming weeks. Companies with existing EU marking derived from UK bodies are in many cases transferring these and future approvals to EU27 regulators.

The situation with regard to conformity assessment procedures between UK and EU from March 2019 is not therefore completely clear, and may not be for some time. It is likely that there will be new barriers to trade in this area, and it will be important for business to monitor and potentially pressure the UK to seek a continuing close relationship with the EU system, which could be available in a stand-alone agreement or as part of a larger package.

Professional Qualifications

Unless the UK remains in the European Economic Area it is unlikely that any comprehensive system for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications between EU Member States and the UK will continue after the Transition Period. In the case of no-deal, the system will end on Brexit day. It is important to note that this will not apply to individuals whose qualifications have been recognised prior to Brexit day or the end of the Transition Period if there is to be one.

Although the methods of mutually recognising professional qualifications across the EEA vary in practice, systems are in place to facilitate the movement of professionals[39]. There are no similarly comprehensive systems established under EU Free Trade Agreements or Association Agreements.

For example under the EU-Canada CETA agreement the two parties encourage professional organisations to negotiate Mutual Recognition Agreements and provide a rough template of what should be covered including the verification of equivalency, evaluation of substantial differences, compensatory measures, and the identification of the conditions for recognition. However no actual agreements have as yet been reached[40].