Trade in the Great Sea: A Brief State of Play of EU-Southern Neighbourhood Trade Relations

Published By: Jan A. Micallef

Subjects: Africa European Union

Summary

The Mediterranean is a vibrant economic geography that could grow significantly. This paper reviews the trade relations between the EU and Southern Neighbourhood Countries (SNCs) – their history and the current status of the bilateral trade agreements. While these agreements have many similarities, there are also some differences in scale and scope. The paper also looks at the development of trade between the EU and SNCs and concludes that developments have generally been positive.

1. Introduction

The Mediterranean is a cradle of civilisation and has been a geography of human development for thousands of years. It also has a rich history when it comes to trade as it was the home of many great trading civilisations and states. Today it is one of the most heterogenous regions in the world bringing together countries in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, whilst connecting with the Atlantic in the West through the Straits of Gibraltar, the Black Sea through the Dardanelles and the seas and oceans in the South and the East of the world through the Suez Canal. It is no wonder that in naming his book on the history of this sea David Aboulafia took up the Hebrew term used in the Bible – “the Great Sea” – to refer to the Mediterranean[1].

Beyond its history, the Mediterranean is still a key region of the world with which the EU is bound. It is also in this context that EU-Mediterranean trade relations merit special consideration.

For the purposes of trade, in view of how trade between EU and non-EU Mediterranean countries is structured, the geographical Mediterranean can be broadly divided into the following four parts:

(i) the Western Balkan countries which have a coast on this sea, namely Albania, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (even though the latter just has a coast of 20km). The EU has concluded Stabilisation and Association Agreements that cover trade with these countries;

(ii) Turkey, with which the EU has a customs union agreement that is in the process of being modernised;

(iii) microstates and entities such as Monaco, Gibraltar and the Sovereign Bases of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, with which the EU has various ad-hoc agreements; and

(iv) the Southern Neighbourhood, which comprises Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Syria and Tunisia.

This paper shall be focusing specifically on the Southern Neighbourhood and will aim to provide a brief state of play of trade relations between the EU and this region of the Mediterranean, together with a background on how these relations developed. The value of this information lies in having a platform to evaluate where these relations stand and to consider whether and how they can be improved for the future.

In this regard, the paper will first look into the evolution of EU trade relations with the Southern Neighbourhood and outline the various existing trade instruments and initiatives that apply. It will then look more specifically into the content of current trade agreements between the two sides and finally give an overview of how trade flows between the two sides fared in the light of the existing trade regime.

[1] Abulafia, D. (2014) The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. London: Penguin

2. The Evolution of EU Trade Relations with the Southern Neighbourhood

The structure of the EU-Southern Neighbourhood trade relations as we know it today originates from the launch of the so-called Barcelona Process in 1995. The Barcelona Process launched a Euro-Mediterranean partnership with the aim of establishing an area of peace, stability, and economic prosperity where democratic values and human rights are upheld.

Prior to 1995, Southern Neighbourhood Countries (SNCs) benefitted from a partial or full removal of customs duties on many tariff lines (with a notable industrial focus and limited coverage of agricultural products) under the EU’s General System of Preferences and under the EU’s Global Mediterranean Policy (a policy that brought together various EU-Mediterranean Co-operation Agreements dating from the 1970s).[1]

Paradoxically, the 1995 watershed moment was brought about by a non-Mediterranean event: the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This event was seen by Germany as a great opportunity for reunification and for attracting Eastern European countries to the West through the promotion of a major policy of cooperation and aid. This policy was expected to help transitioning Eastern countries towards democratic free market systems. Seeing this, Southern European countries, particularly Spain, wanted to grant the same opportunity to the SNCs. The result of these visions was the delivery of the Phare and Thacis policies for the East and the Barcelona Process for the South.[2]

Other political events also created gravitation towards new levels of cooperation with the region. A case in point was the Oslo Agreement of 1993 between Israel and the Palestinian Authority that brought a wind of optimism that helped carry the Euro-Mediterranean partnership of 1995 forward.[3]

Through its economic dimension the Barcelona Process aimed to establish a free trade area by 2010 in the Mediterranean region on the basis of the argument that economic development, political liberalisation and democratisation complement each other. The rationale was that economic liberalisation and the reinforcement of trade interdependence between partners should in the long term remove the causes of inter-state conflicts, with the economy becoming an instrument of peace between states.[4] This free trade area was meant to be built on a series of bilateral agreements that also covered trade.

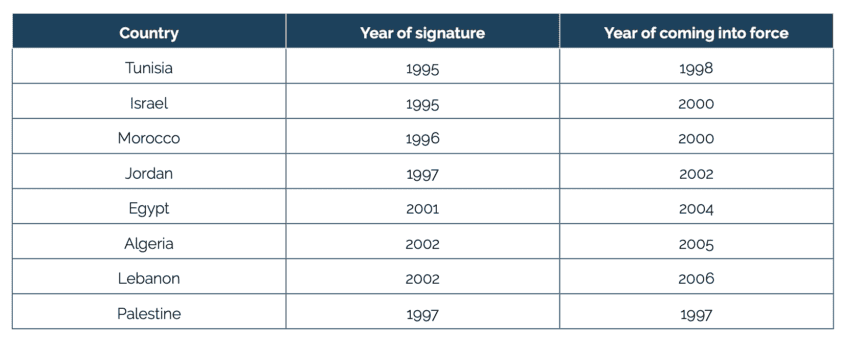

The EU and countries in the region proceeded to establish Association Agreements (AAs) respectively that also contained free trade agreements embedded within them. AAs were concluded by the EU with Tunisia (in 1995), Jordan (in 1997), Morocco and Israel (in 2000), Lebanon and Algeria (in 2002) and Egypt (in 2004). An interim agreement was also signed with Palestine in 1997. These agreements created asymmetric free trade areas for manufactured goods, with concessions on agricultural products and fisheries. Negotiations with Libya were never concluded (due to the isolation imposed on it after the Lockerbie and Berlin terrorist attacks), whilst a simple cooperation agreement with Syria was eventually suspended in 2011.

Beyond these AAs, economic relations continued to evolve year by year in the framework of the Barcelona Process through the implementation of various initiatives. In 2002 the FEMIP fund (Facility for Euro-Mediterranean Investment and Partnership) was launched. The fund is managed by the European Investment Bank[5] and aims to provide for financial assistance for small businesses and other innovations in SNCs.

March 2003 saw the launch of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) comprising the Southern Neighbourhood. The objective of this policy was to avoid the emergence of new dividing lines between the enlarged EU and its neighbours, and to strengthen the prosperity, stability and security of all. The ENP also had an economic dimension which was important for trade.

In December 2003, the Euro-Mediterranean Parliamentary Assembly (EMPA) was established. This gave the Barcelona Process a more inclusive and democratic dimension. (NB: The EMPA was later renamed Parliamentary Assembly of the UfM in 2010 (PA-UfM). The EMPA had competences to cover trade issues.

In 2008, the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) was launched. The UfM upgraded the Barcelona Process to a new dimension and in a way also institutionalised it. The scope of this organisation, aptly based in Barcelona, was to enhance regional cooperation, dialogue and the implementation of concrete projects and initiatives with tangible impact on the lives of citizens. Pushed by the then French President, Nicolas Sarkozy, its aim was to adopt a more pragmatic approach towards the region with the promotion of specific projects of a practical and applied nature, through co-ownership by partner countries.[6]

In 2011, another important legislative step for trade was taken when the Regional Convention on Pan-Euro-Mediterranean Preferential Rules of Origin (RoOs) was signed and ratified by all SNCs30. This instrument complemented the existing trade agreements between all countries.[7] The Convention establishes common rules of origin and cumulation among the partner countries and the EU to facilitate trade and integrate the supply chains within the zone.

Developments kept on going smoothly, until another watershed moment in the region came about in 2011. This moment was the Arab Spring, and it changed Mediterranean relations.

In view of the Arab Spring upheavals, the Commission and the EU’s High Representative urgently adopted ‘A New Strategy for a Changing Neighbourhood’ on 25th May 2011, which emphasised democratic reforms, strong support for civil society, reduction of inequalities and a dialogue on human mobility. Aid was conditioned to reforms and the principle of “more assistance for more reforms”. At the same time the Commission was given a mandate to negotiate Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) with Egypt, Morocco, Jordan and Tunisia to boost investment in these SNCs. These DCFTAs were to be similar to those then being negotiated with Eastern Partnership States.[8] The implementation of the free trade agreements that were part of the AAs with SNCs was close to completion anyway. As some provisions of these FTAs called for additional negotiations on deeper integration (e.g. in the area of services trade and FDI), the EU started the process of negotiating the DCFTAs accordingly. Negotiations with Tunisia and Morocco were launched in 2013 but got quickly interrupted. After four rounds, they were put on hold on the request of Morocco to carry out additional studies before going ahead with the negotiations. In Tunisia, negotiations were put on hold for the same reason and because of a change in government. Business communities and NGOs in both countries got cold feet as they feared their industries would be taken over by more competitive European businesses. Ever since then there have been calls at various levels for negotiations to resume but still they have not. Similarly, negotiations with Egypt and Jordan never got off the starting blocks.

Despite these setbacks, initiatives that cover trade also continued at various levels in the context of the new Arab Spring reality. The so-called Partnership Priorities are worth noting. These emanate from the revised EU Neighbourhood Policy and the EU Global Strategy for foreign and security policy. The Priorities were agreed with all SNCs except Morocco, which was overhauling its overall partnership with the EU. Their rationale is to go for more targeted and jointly agreed cooperation informed by mutual interests. The Partnership Priorities are important for trade as they call for the deepening of existing trade agreements.

After the Arab Spring, there were also a number of smaller but important concrete initiatives that were delivered. For example, in 2016 Autonomous Trade Measures (ATMs) were adopted in favour of Tunisia for olive oil, which was its main agricultural export to the EU. These measures allowed for the entry of this product to the EU on the basis of a duty-free tariff quota. The purpose of this initiative was to instill some momentum in the Tunisian economy following a terrorist attack in Sousse in 2015. In the same year another trade initiative was adopted to help Jordan cope with an influx of migrants from Syria. This initiative simplified the rules of origin that Jordanian exporters use in their trade with the EU when they increase the legal employment of Syrian refugees. The initiative was amended in December 2018 to accelerate its uptake and extend its duration. Another worthy instrument was the package of measures to facilitate trade of Palestinian products with other Euro-Mediterranean partners. This was launched in 2010 and is still ongoing up till this day.

Another good initiative was the launching of the Euromed Trade Helpdesk in 2017. The Helpdesk was funded by the EU and is being implemented by the International Trade Centre (ITC). It constitutes a free online portal for country and product-specific information on tariffs and duties, import and export procedures, and market requirements. In addition, the Helpdesk offers a network of national focal points in each participating Mediterranean country to respond to enquiries on intra-regional trade issues.

The Pan-Euro-Mediterranean (PEM) convention on preferential RoOs was also modernised. As a result, a new set of RoOs are applicable as from mid-2021. In November 2019, the final adoption of the proposed revised version had failed. To allow companies to benefit from the modernised and simplified RoOs, most contracting parties that were willing to engage decided to allow the application of the revised rules bilaterally on a transitional basis. Only Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco have rejected the application of the transitional rules. The two sets of rules, that is the original rules and the transitional rules, will coexist and will be applied alongside one another with economic operators being able to choose which set of rules they want to apply to their consignments.[9]

Since 2020 there have also been some new efforts to create political momentum for trade in the region. On 10 November 2020, the trade ministers of the Union for the Mediterranean convened for the 11th Trade Ministerial Conference. In their Joint Statement they called for the strengthening of trade ties as a crucial element for regional economic recovery. The Conference came on the 25th anniversary of the Barcelona Process and was an opportunity to reflect on the EU’s strategic partnership with its Southern Neighbourhood in light of the political, socioeconomic, financial and environmental challenges exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, and to reassess the EU’s partnership with the region. This reflection resulted in a Joint Communication entitled ‘A Renewed Partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood – A New Agenda for the Mediterranean’, as well as an annexed ‘Economic and Investment Plan for the Southern Neighbours’.

In February 2021, under the new EU Trade Policy Review, the EU announced a new sustainable investment initiative for interested partners in the Southern Neighbourhood and Africa.

Also in 2021, the European Commission published an ambitious Ex-Post Evaluation of Trade Chapters of the Six Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreements with the EU’s Southern Neighbours: Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia. The evaluation’s main objective was to assess the effects of trade chapters and propose recommendations for further enhancing economic integration in the Euro-Mediterranean area.

This is how EU-Southern Neighbourhood trade-policy relations developed up till this day. Through these developments relations are now governed by the trade agreements embedded in the AAs and the various legislative, political and institutional initiatives that were implemented throughout the years.

[1] European Commission (2021) Ex-post Evaluation of the impact of trade chapters of the Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreements with six partners: Algeria, Egypt. Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia – Final Report: p.41

[2] Florensa, S. (2021) From the Barcelona Process to the Union for the Mediterranean – A project for a Shared Future. Available at: https://revistaidees.cat/en/from-the-barcelona-process-to-the-union-for-the-mediterranean/ (Accessed 25 February 2023)

[3] Mirel, P. (2021) From the Barcelona Process to the Mediterranean Programme, a fragile partnership with the European Union. – European Issue No.601, Fondation Robert Schuman. Available at https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/0601-from-the-barcelona-process-to-the-mediterranean-programme-a-fragile-partnership-with-the-european (Accessed 25 February 2023)

[4] Kasmi, S. (2015) 25 Years of the Barcelona Process – Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Background Paper.

[5] op.cit 3

[6] op.cit 3

[7] op.cit 2 p.45

[8] op.cit 4

[9] Stein. R.M. & Von Rummel, L. (2021) The Revised PEM Convention: Parallel Application of the Transitional PEM Rules of Origin since 1 September 2021 Lexology (Blomstein). Available at: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=18f6e142-8b6f-40cc-8044-7fa7c30c36f9 (Accessed on 25 February 2023)

3. The Trade Agreements Between the EU and the Southern Neighbourhood

Even though there were various developments in the EU-Southern Neighbourhood on trade since 1995, the linchpin of EU-SNC trade relations remains the concrete old generation trade agreements that are embedded in the AAs, together with the ad-hoc legal instruments that accompany them.

In this regard it is pertinent to take a closer look at them. The Agreements are the following:

Table 1: EU-SNC Trade Agreements

What is the content of the trade agreements?

In reviewing the content of these agreements, it is useful to first get a bird’s eye view of them by looking at their architecture. The Association Agreements can be divided into the following parts: (i) political dialogue; (ii) trade related issues; (iii) economic cooperation; (iv) cooperation in social and cultural measures; (v) financial cooperation; (vi) institutional provisions; and (vii) Annexes and Protocols which mainly contain the technical details in order to make the trade related parts of the agreement work. The part that is mainly of interest to this paper is the second.

The interesting parts in this second part mainly take the following general form as a model:

Title II: Free movements of goods

Chapter 1 Industrial Products

Chapter 2 Agricultural, fisheries and processed agricultural products

Chapter 3 Common Provisions

Title III: Right of Establishment and Trade in Services

Title IV: Payments, capital, competition and other economic provisions

Chapter 1 Current payments and movement of capital

Chapter 2 Competition and other economic provisions

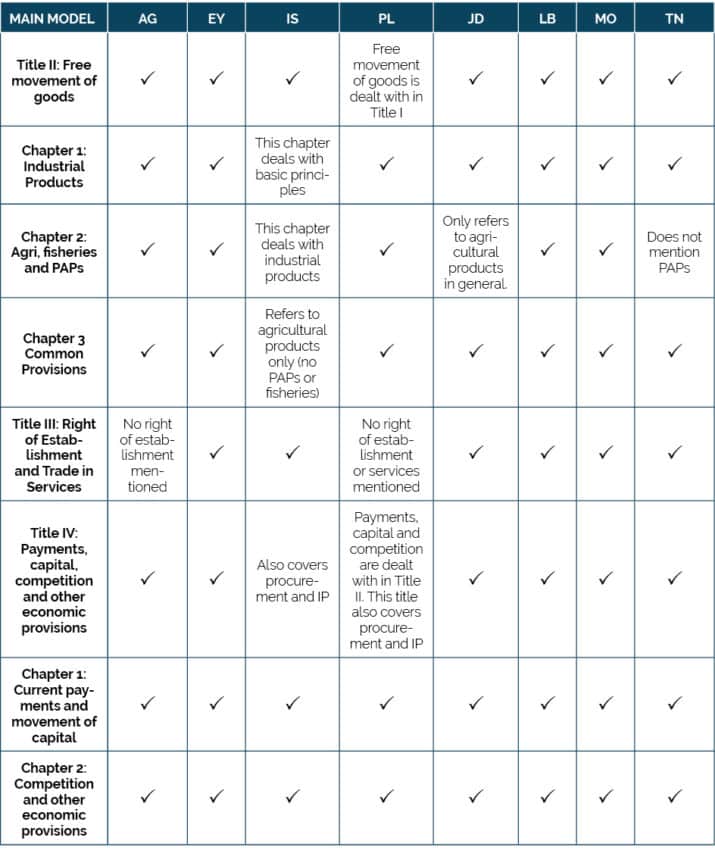

The architecture follows this model and the content is thus nearly identical in all the agreements. However, there are differences that reflect the sensitivities of each SNC and the context in which they were negotiated.[1]

Taking this model as a starting point, the specific parts in the architecture of each agreement are the following:

- Algeria: In Title III there is no Right of Establishment mentioned

- Egypt: the architecture is identical to the model above.

- Israel: Chapter 1 in Title II deals with Basic Principles. Industrial Products are then dealt with Chapter 2. Chapter 3 only refers to agricultural products, as opposed to also mentioning processed agricultural products and fisheries. Title IV also covers procurement and intellectual property.

- Palestine: Free movement of goods is dealt with in Title I. There is no right of establishment or trade in services mentioned. Payments, capital and competition are dealt with in Title II. At the same time Title II also mentions procurement and intellectual property as issues (in the same way that they are mentioned in Title IV of the EU-Israel AA)

- Jordan: Even though all AAs contain provisions on agricultural products, processed agricultural products and fisheries products[2], here Chapter 2 refers only to agricultural products in general, as opposed to mentioning all of these products.

- Lebanon: the architecture is identical to the model above

- Morocco: the architecture is identical to the model above.

- Tunisia: Chapter 2 under Title II does not mention processed agricultural products.

Overall, these differences in architecture are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Architecture of agreements

Moving on from the architecture to the content per se, on trade in goods the agreements mainly set out a reduction of tariffs, namely for industrial goods. To a lesser extent they also cover trade in agricultural goods, processed agricultural products and fisheries.[3] Here the market access benefits that were already provided under the agreements prior to the AAs were reproduced, whilst additional access was also provided. The products liberalised and the time period for liberalisation vary between agreements as they reflect the sensitivities of each SNC and the EU.[4] Furthermore, all AAs contain provisions on agricultural products, processed agricultural products and fisheries products. It is important to note that additional agreements on these products were concluded with Egypt, Jordan, Israel and Morocco.[5]

The AA’s also touch upon trade in services, FDI and capital movements. However, the provisions here relate more to restating existing WTO commitments and laying the ground for future initiatives, rather than advancing new or binding commitments.[6] When it comes to services the agreements with Algeria, Jordan and Lebanon are more detailed than for the other agreements.

As to the Right of Establishment, the AAa with Algeria, Israel and Jordan largely refer to providing MFN treatment in this area, whilst the AAs with Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia invite the parties to consider allowing the establishment of companies in each other’s territories to provide services to the consumers of the respective party.

On the movement of capital and competition, all AAs provide for the parties to allow all current payments for current transactions be made in a freely convertible currency and that capital relating to direct investments can move freely from one party to the other. Moreover, the agreements define prohibited anti-competitive behaviour such as that related to state aid and state monopolies.

The AAs also touch upon issues such as technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) rules. However, rather than providing concrete and binding commitments, the AAs mainly push for transparency on these elements.[7] The AAs also tackle intellectual property, emphasising that the respective parties grant protection in line with international standards.

Public procurement is also mentioned, in that it commits the parties to gradually liberalising their public procurement markets.

The AAs also have common provisions tackling principles of the trade relationship between the two sides, such as providing safeguards against increases in trade that harm any of the parties and a standstill clause that prevents the parties from introducing new duties on imports or exports.

Overall, the AAs are mainly asymmetrical to the advantage of SNCs. They aim at establishing free trade agreements over a transitional period that lasts for a maximum of 12 years from the date of entry into force of the respective agreements.[8]

When it comes to the specificities of the content of each Agreement the following can be noted[9]:

Algeria

The Agreement provides for reciprocal liberalisation of trade in goods, with elements of asymmetry in favour of Algeria, such as a 12-year transitional period for dismantling tariffs for industrial goods and selective liberalisation on agriculture. In 2012, the EU and Algeria agreed to review the timetable for tariff dismantling set forth in the Agreement for certain products (steel, textile, electronics, and automobiles), extending the transitional period from 12 to 15 years. The complete dismantling of tariffs and thus completion of the EU-Algeria free trade area was foreseen for September 2020 but has only been implemented partially. In the meantime, Algeria unilaterally established additional duties for a series of products while prohibiting imports of certain other products, in particular cars.

The market opening for agricultural products so far only concerns a limited number of tariff lines, which are subject to either full liberalisation, tariff rate quotas (TRQ) or a reduction of Most Favoured Nation (MFN) rates respectively for both parties.

Egypt

The EU Egypt AA provides for reciprocal liberalisation of trade in goods, with elements of asymmetry in favour of Egypt. Egypt was able to export to the EU all industrial products covered by the Agreement tariff-free from the day of entry into force of the Agreement, while it benefited from a transitional period of 3 to 15 years, depending on the product, to dismantle tariffs on imports from the EU. Egypt finalised the process of fully dismantling tariffs applied to industrial goods on 1 January 2019.

In October 2008, the EU and Egypt signed an Agreement providing for liberalisation in agricultural, processed agricultural and fisheries goods. The latter entered into force on 1 June 2010 and extended the list of agricultural products covered by the original Agreement. Today, 80% of trade in agricultural goods is covered by duty-free treatment.

Israel

The terms of the Agreement provided for full elimination of customs duties applicable to industrial products and partial liberalisation for agricultural products. The EU and Israel had already had an FTA from 1975, eliminating duties on industrial products and over 80% of agricultural tariff lines. The AA improved the provisions on rules of origin and included a series of further reciprocal agricultural concessions.

The EU and Israel subsequently upgraded the FTA by signing agreements which further liberalised trade in agricultural products (notably in processed agricultural products) and fish and fishery products. The latter further increased reciprocal market access in agro-food products and is based on the “negative list approach” (i.e. all agro-food trade is liberalised on both sides apart from a limited number of sensitive lines on either side). For the sensitive agricultural products, such as sugar, fruits and vegetables, market access on both sides is provided in the form of duty free quotas. Moreover, the EU maintains its entry price system, but with an ad valorem duty component set at 0%.

Jordan

The Agreement liberalised two-way trade in goods, with asymmetrical transition periods in favour of Jordan, whereby Jordan phased in tariff reductions over a 12-year period. Tariff dismantling has been completed.

The EU and Jordan upgraded the Agreement in 2006 by concluding an additional agreement on trade in agricultural and processed agricultural products. Today all Jordanian agricultural products can enter the EU duty free with the exception of virgin olive oil and cut flowers, which are subject to tariff rate quotas (TRQs). Agricultural liberalisation on the Jordanian side is substantial, but not complete.

Under the simplified Rules of Origin initiative, adopted in 2016 and amended in 2018, Jordanian exporters of 52 product groups can benefit from the same rules of origin as those applied by the EU on the Least Developed Countries, provided that certain conditions are met with regards to the employment of Syrian refugees.

Lebanon

The Agreement liberalised trade in industrial goods with an asymmetrical transition period of 12 years in favour of Lebanon. The phased-in liberalisation of industrial products by Lebanon started in 2008 and was completed in 2015.

With regard to agri-food trade, the Agreement as of its provisional application, granted tariff- free access to the EU market for most Lebanese agricultural and processed agricultural products (i.e. 89% of products enter tariff and quota free), with only 27 agricultural products facing a specific tariff treatment, mostly tariff rate quotas (TRQs). On the other hand, agricultural liberalisation by Lebanon has been more limited.

Morocco

Trade in industrial products is now entirely liberalised, while market opening for agricultural products is also substantial compared to other AAs. The Agreement provides for a reciprocal liberalisation of trade in goods, with elements of asymmetry in favour of Morocco. Since the day of entry into force of the Agreement, all industrial products covered could be exported by Morocco to the EU tariff-free, while Morocco benefited from a transitional period of 12 years. The transitional period for Morocco to reduce its tariffs on industrial products to zero ended in March 2012.

The EU and Morocco also signed an agreement on additional liberalisation of trade in agricultural products, processed agricultural products, fish and fisheries products, which entered into force in October 2012. A number of EU products remain subject to tariff rate quotas when exported to Morocco while for the other products the full liberalisation was completed on 1 October 2020. Only a few Moroccan products are still subject to tariff rate quotas when imported into the EU.

Palestine

The Interim Association Agreement creating a free trade area between the EU and Palestine was signed in 1997 and entered into force on 1 July 1997. The Interim Agreement liberalised two-way trade in industrial goods by providing duty-free and quota-free access for industrial goods traded in both directions, with some limited liberalisation of agricultural products by both parties. The latter was an asymmetrical liberalisation to the extent that the EU dismantled its tariffs on the first day of the agreement while Palestine had a phased reduction of tariffs.

The Agreement was first updated in 2005 and a more significant update was signed in 2011 to further liberalise trade in agricultural, processed agricultural products, fish and fishery products. The EU removed all tariffs and quotas on agricultural products and processed agricultural products (PAPs) imported into the EU for a period of ten years, which is renewable. Palestine continues to maintain a number of tariffs and quotas on selected agricultural and PAP imports from the EU.

Products from Israeli settlements in Palestinian territory do not benefit from the preferential tariff preferences under the EU-Palestine and EU-Israel Association Agreements.

Tunisia

The Agreement provided for reciprocal liberalisation of trade in goods. Since the day of entry into force of the Agreement, Tunisia is free to export to the EU all industrial products covered by the Agreement tariff-free, while it benefited from a transitional period of 12 years for imports from the EU, which ended in 2010.

With regards to agricultural, agri-food and fisheries products, the Agreement foresees liberalisation for selected products, with the EU granting tariff-free quotas for a number of products. Contrary to other countries in the region (ex. Morocco or Egypt), the EU and Tunisia have not yet negotiated an agricultural agreement and hence market access on both sides is more limited than is the case with most other SNC partners.

[1] op.cit 2 p.44

[2] op.cit 2 p.51

[3] op.cit 2 p.42

[4] ibid.

[5] op.cit 2 p.51

[6] op.cit 2 p.44

[7] ibid.

[8] op.cit 2 p.50

[9]The following information was extracted from the Report from the Commission on Implementation and Enforcement of EU Trade Agreements COM(2022)730 – 11 October 2022.

4. How Have EU-Southern Neighbourhood Trade Flows Fared with the Current Trade Regime?

To understand the trade relations between the EU and SNCs, it is necessary to also review the developments of actual trade. The statistics of these flows are far from being a precise instrument to measure the role and significance of these agreement. Trade flows are affected by many factors such as whether the competitiveness and economic activity of the countries in question has arisen or diminished due to reasons unrelated to the trade regime, whether the international price of goods has gone up or down or the development of trade relations of each country with other third countries. Nevertheless, trade data is a good starting point and do have value in giving a general picture to determine the effects of evolving EU trade policy.

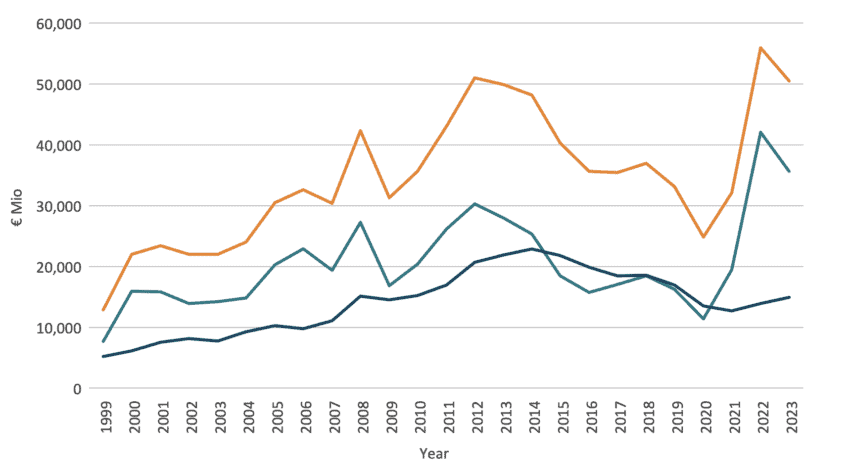

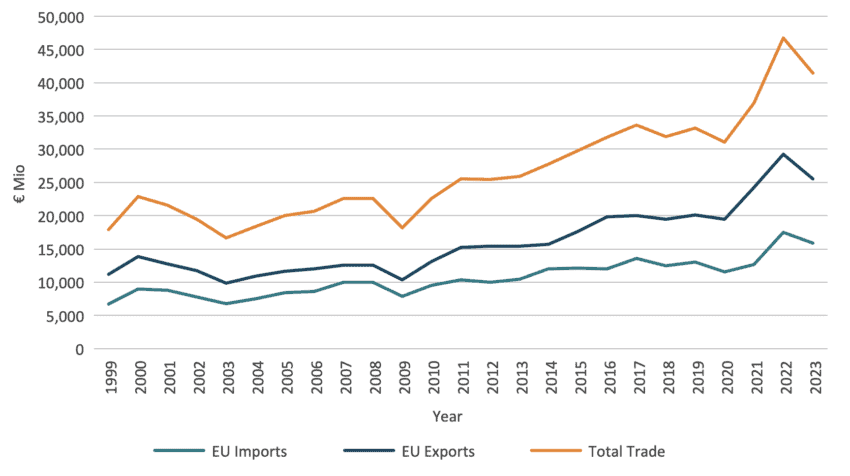

Figure 1: Trade between the EU and Algeria Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Algeria stands out because it is the only SNCs with which the EU has a trade deficit. This is mainly because Algeria’s exports to the EU constitute oil. Trade relations have improved overall from when the AA came into force in 2005. Exports to the EU rose suddenly in 2008 then dropped back in 2009 (the year of the financial crisis). Algerian exports rose gradually again with a peak in 2012 and then decreased gradually till 2020. These decreases were due to the reduction of oil prices at the time. 2021 then saw an increase. On the other hand, EU exports to Algeria showed gradual increase till 2014 until they went on a gradual downward trajectory. Overall trade flows for both Algeria and the EU are positive when compared to the pre-2005 period when the AA was not in force yet.

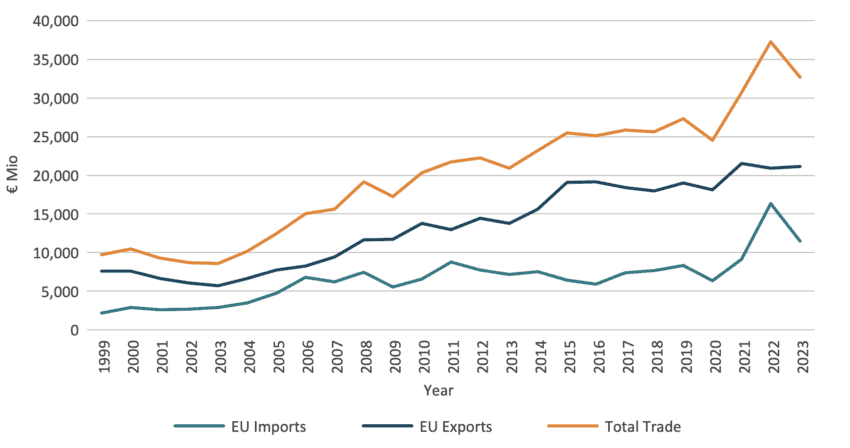

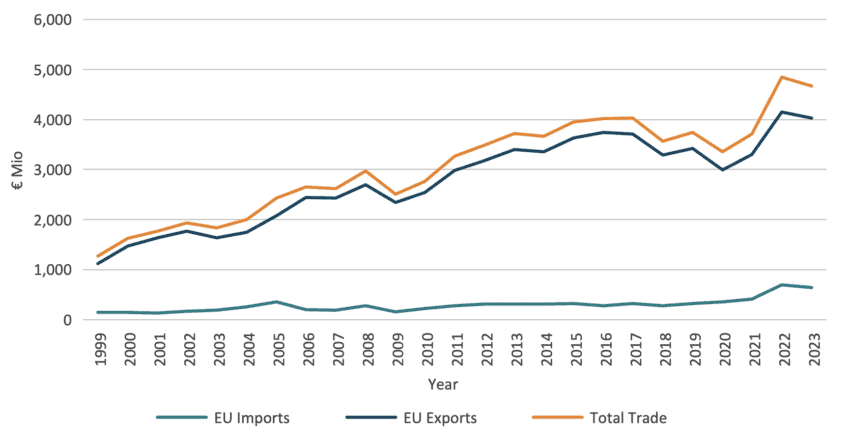

Figure 2: Trade between the EU and Egypt Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Trade flows for both the EU and Egypt started going on a positive trend since the AA came into force in 2004. The trade flows are more advantageous for the EU. However Egyptian exports went on a positive trend too. EU imports peaked in 2022 and started coming back down in 2023. Since the AA came into force trade flows never went below the pre-2004 period.

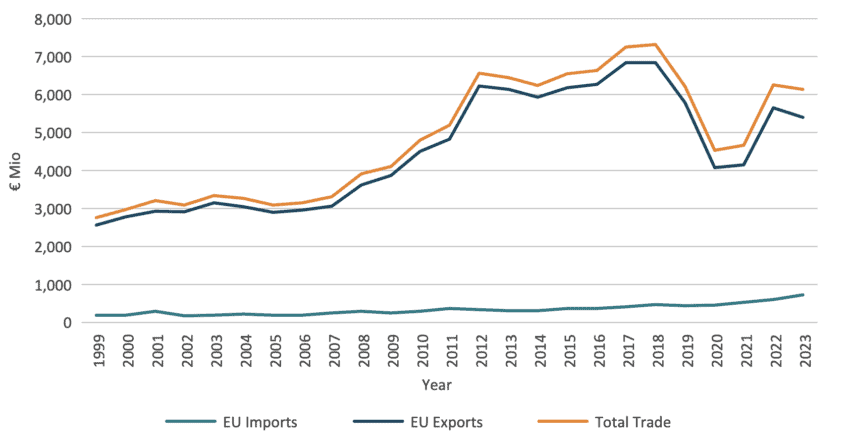

Figure 3: Trade between the EU and Israel (incl. Gaza and the West Bank) Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

The EU-Israel AA came into force in 2000. Israel has a trade deficit with the EU. Trade between the two sides has fluctuated with eventual ups and downs. Nevertheless, the trend in trade flows is an upward one.

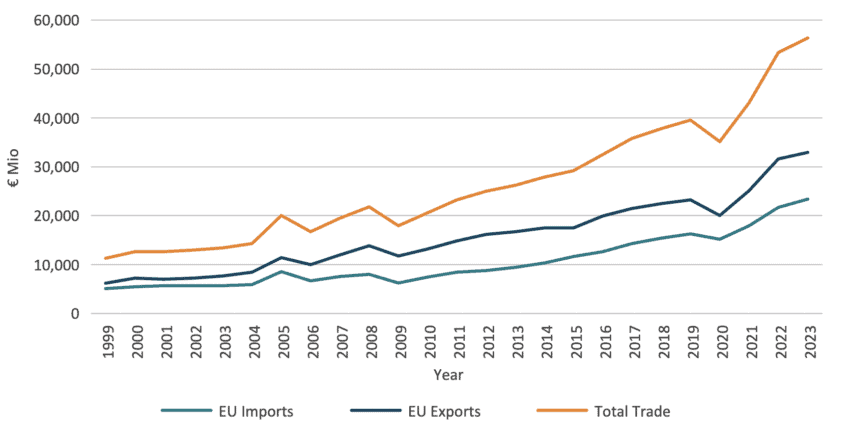

Figure 4: Trade between the EU and Jordan Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

The EU-Jordan AA came into force into 2002. Whilst EU exports to Jordan saw a steep rise upwards throughout the years, Jordanian exports to the EU only saw very slight improvements.

Figure 5: Trade between the EU and Lebanon Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Since the EU-Lebanon AA came into force in 2006, the EU exports to Lebanon rose considerably whilst Lebanon’s exports to the EU remained relatively constant, similar to Jordan’s exports to the EU.

Figure 6: Trade between the EU and Morocco Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Ever since the AA came into force in 2000 both exports and imports between the two sides saw a steady gradual increase, with considerable growth taking place as from 2021

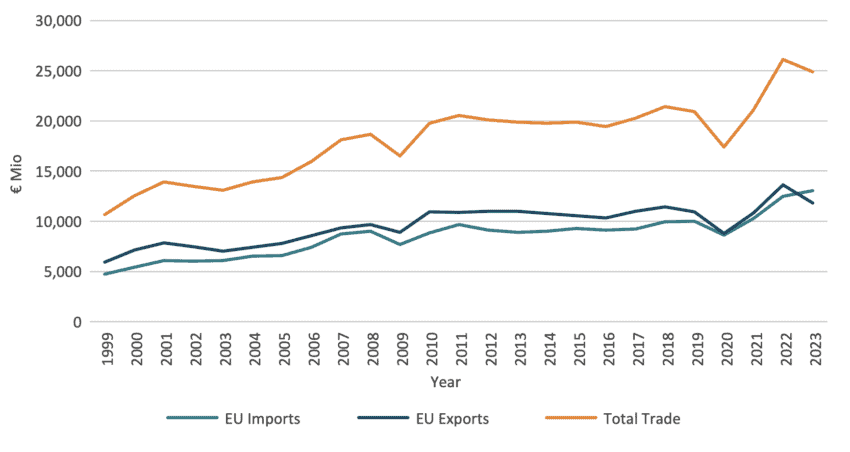

Figure 7: Trade between the EU and Tunisia Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

Source: The chart has been compiled using figures obtained from Eurostat’s Data Browser

The EU-Tunisia AA was implemented as from 1996. Statistics from 1999 onwards show a gradual steady increase in imports and exports between both sides with occasional ups and downs.

These trade statistics show that, throughout the years, as the trade regime between the EU and SNCs developed, trade flows generally grew in a positive manner. The Commission report on the ex-post evaluation of the impact of trade chapters of the Euro-Mediterranean Association Agreements which went into much more technical detail and used advanced modelling techniques, also reached the same conclusion. The study showed that the effects of the Euro-Med FTAs on trade (as well as on GDP, welfare, consumers and workers) have been positive. SNCs also gain relatively more than the EU from the Euro-Med FTA preferences even if the estimated changes are not large. The study also concludes that diversification and economic complexity of exports of SNCs have also recorded improvements since the entry into force of these AAs.[1]

[1] op.cit. 2, page 75.

5. Conclusion

From the watershed moment of 1995 onwards, EU trade relations with SNCs developed through various initiatives. Today, trade relations are mainly governed by the free trade agreements embedded in the AAs and the various other institutional and political initiatives outlined in this paper. The AAs nevertheless remain the backbone of these trade relations up till this day. Trade flows also show that the developments throughout the years brought positive results both for the EU as well as for the SNCs.

Nevertheless, the question arises as to whether these trade relations are developed enough and whether all sides are harnessing trade to its full potential. The answer to this is in the negative. Despite the positive results it brings, the EU-SNC trade regime is lacking and needs to be upgraded. This and more will be the subject of another paper.