The New Globalisation: SMEs and International Trade – The Supply Chain is as Important as Direct Exports

Published By: David Henig Renata Zilli

Subjects: New Globalisation Sectors

Summary

The disproportionately small share of exports from Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) is a cause of concern in modern trade policy. For developed countries, they typically account for over 95% of all businesses, two-thirds of the labour force, yet less than 50% of economic activity, and under a third of total export value. There is a compelling global narrative which argues we are missing a major economic opportunity.

Conventional policy responses have been to implement targeted help and propose improvements such as SME chapters in Free Trade Agreements. Yet, these have proven inadequate, unsurprisingly given the many and varied trade barriers which represent a disproportionate marginal cost for SMEs.

It is worth considering that since the formation of the GATT the majority of trade will have been carried out by large companies. This has been a common feature of international trade for many years, and while the new globalisation may help in some ways, such as services exporters using platforms, it will hinder in others, such as the growth of regulatory costs.

This need not be a significant economic problem provided SMEs are able to grow domestically, and can indirectly contribute to international trade through supply chains. Arguably, the focus of attention around this subject has not been well placed.

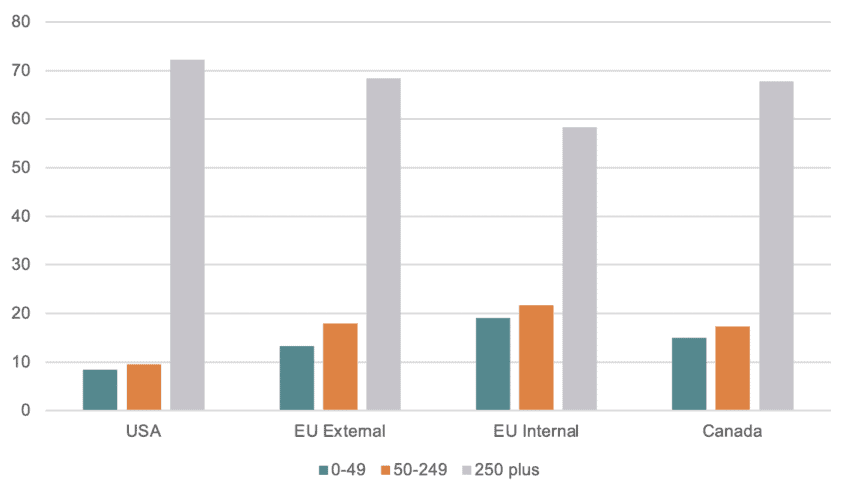

Large companies carry out the majority of global trade

The strength of large companies in global trade is broadly agreed. For example, looking at the US, Canada and EU, around 70% of the value of goods exports comes from larger companies. More small than large firms export, however the average size of exports per firm is far higher for large companies, being ten-times the amount of medium sized companies, and over fifty-times the size of small ones for the EU.

Figure 1: 2019 Goods exports by firm size (%) Sources: Eurostat, OECD, US Census Bureau

Sources: Eurostat, OECD, US Census Bureau

It is notable though that the share of large EU companies in exports within the Single Market is significantly lower than their share for extra-EU exports. This suggests that the removal of virtually all tariff and regulatory barriers can make a difference. In general, this has not been a consequence of Free Trade Agreements. For example, a July 2021 paper examining EU exports to South Korea after that FTA[1] finds that “French exporters with larger pre-FTA sizes expand their exports to South Korea by larger rates than firms further down the size distribution” and that “this confirms a widely-held prior that FTAs benefit larger firms more than smaller ones.” This is of particular significance for the UK having recently left the EU single market, with early data suggesting that the expected outcome of a reduced share of SME exporting is occurring.

The share of SME exports in services seems to more closely reflect that of their economic activity. For example, figures from Canada show that companies with fewer than 500 employees represent a higher share of exports than those with greater than this number[2]. Similarly, an EU paper of May 2020[3] suggested that “the limited data we have at our disposal suggests that the share of SMEs in extra-EU export of services is around 40%.” Similarly, SME import shares are also higher than for exports.

While it is possible to extrapolate figures of how much trade could rise if more SMEs exported, it is not obvious why this is a particularly helpful metric in terms of government action given global norms. Indeed, the absence of any baseline means we shouldn’t assume such intervention is the answer.

[1] Kiel Working Paper, Trade Liberalization along the Firm Size Distribution: The Case of the EU-South Korea FTA, Sonali Chowdhry and Gabriel Felbermayr July 2021, retrieved from https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/-ifw/Kiel_Working_Paper/2021/KWP_2176_Chowdhry_Felbermayr/KWP_2176_July_2021.pdf

[2] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/211207/dq211207b-eng.htm

[3] https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2020/june/tradoc_158778.pdf

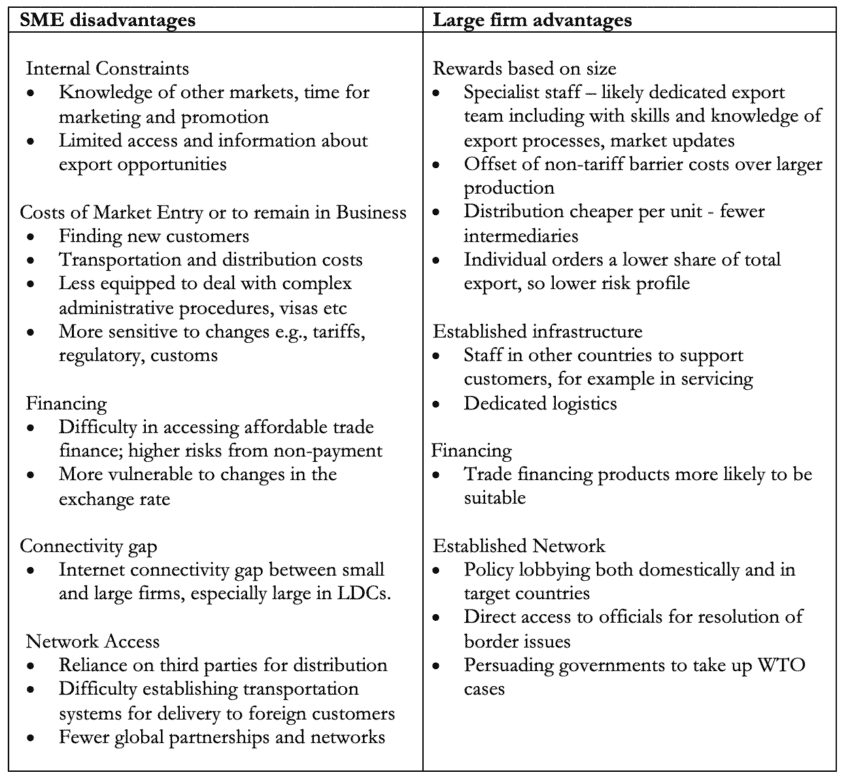

Far more international barriers than trade policy for smaller companies

At the heart of the lower SME export share is that the more output a firm produces, the easier it becomes to absorb the many costs and risks involved in exporting. While SMEs may have other advantages, perhaps an ability to innovate more quickly, the structural hurdles remain huge.

There is indeed such a myriad of barriers to SME exporting that they are individually difficult to evaluate. Those listed below, coupled with the number of SMEs, their heterogeneity and the specificities according to their local business and regulatory environment, means a picture so differentiated that it is unlikely to be dramatically affected by a single policy prescription.

Table 1: Export barriers affecting different firm sizes

Efforts by governments to raise SME exports have not been equal to the diverse challenges, not least given more efforts are made for the largest companies. While half of all Free Trade Agreements notified to the WTO incorporate at least one provision explicitly mentioning SMEs, all of them will reflect the priorities of larger companies who are often seen as national champions.

That the international trade playing field is so uneven reflects both inherent factors of size and active government policy decisions to support large companies. In thinking about potential policy interventions, therefore, there is a need to examine further the problem to be solved.

Policy Prescriptions – Finding different pathways for SME growth

Studies suggesting economic growth from increasing the number of SMEs exporting are based primarily on a productivity boost for companies that trade, together with potential competition effects. Given that more productive companies in any case seek to increase exports, the impact may be lessened, and also suggests that encouraging companies to grow in other ways could have a similar impact.

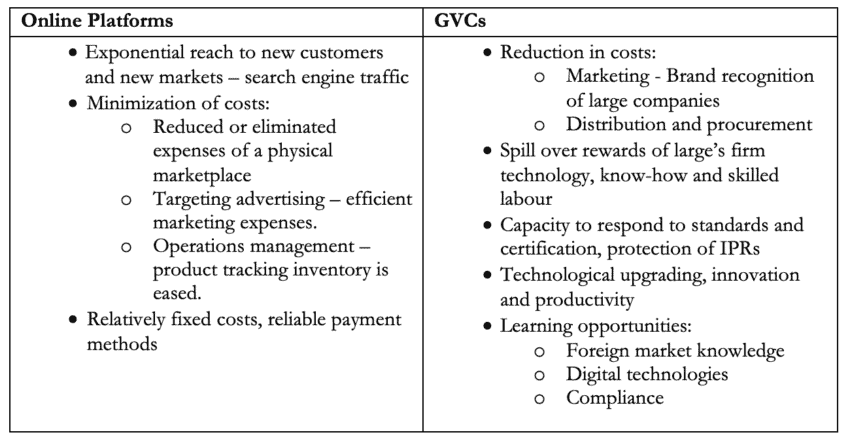

While some of these pathways will be purely domestic, today’s global trade also offers the opportunities from platforms and through global value chains. In 2020 there were around 21 million SMEs in the EU, but figures from 2017 showed only 700,000 exporting outside the bloc. Given 2020 figures from the UK showing 530,000 exporting SMEs, compared to 300,000 UK businesses selling through eBay, potentially internationally, online marketplaces would be one obvious place to look to increase export numbers.

Meanwhile large companies offer equally significant opportunities, and while they rarely publish such internal data some examples include French oil company Total stating it has more than 150,000 suppliers; Walmart counting over 100,000 and Proctor & Gamble at least 75,000. A previous study by the US International Trade Commission showed that “In 2007, direct exports of goods and services by U.S. SMEs totalled… approximately 28 percent of total U.S. exports. According to Commission calculations, if the value of intermediate inputs that SMEs supplied to exporting firms is taken into account, SMEs’ total contribution to exports in 2007 would increase to $480 billion, or 41 percent of the total value of U.S. exports of goods and services.”[1] This is clearly another pathway to SME growth and exports.

Table 2: Advantages to SMEs of exporting through online Platforms or Global Value Chains

Growth through these channels has taken place largely without government assistance. Indeed, when compared with the dedicated SME chapters of FTAs which only offer improved information, the use of platforms and large companies would seem to offer far more. Neither represent a perfect answer, for there will be limitations and costs, but both should be part of a balanced set of policy options.

[1] https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4189.pdf

How governments should approach SMEs and trade policy

Encouraging SME growth is important for competition and productivity. Direct export is however only one path, and this should be reflected in government actions. As an important start, consistent data sets on Global Value Chain participation should go alongside figures on share of exports in both goods and services.

There is still an argument for trade policy support to SMEs on grounds of fairness for government intervention to at the very least provide as much support as is provided for larger companies. This should however be based on a greater understanding of need. For example while the provision of information is useful, doing more to facilitate direct international business-to-consumer trade would probably be of more direct use.

Probably more important however will be to ensure regulatory changes do not undermine SME participation in value chains. Proposed measures such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive requiring supply chain monitoring could act as a disincentive to larger companies using smaller suppliers. Equally, measures to exempt SMEs from certain regulations have the potential to create a confusing landscape with the same outcome. Such measures need to be considered for their impact on indirect SME exports.

The likelihood remains that larger companies will continue to dominate international trade, the worry is that this could in fact worsen. The pathways for smaller companies to grow need to be protected, with direct exports only one of these.