Reinventing Europe’s Single Market: A Way Forward to Align Ideals and Action

Published By: Matthias Bauer Dyuti Pandya Vanika Sharma Elena Sisto

Research Areas: Digital Economy EU Single Market European Union

Summary

It is essential for EU institutions and Member State governments to shift their focus from the abstract concept of the “Single Market” to the concrete objective of “legal harmonisation in the EU.” This transition represents a strategic realignment towards more pragmatic policymaking. Adopting a 28th regime to address national regulation discrepancies would align with this goal and enhance the Single Market’s effectiveness in promoting economic growth and competitiveness. Given the EU’s ongoing loss of relative global economic clout, it is crucial to establish an ambitious timeline for implementing the most critical Single Market reforms.

The Letta Report serves as a wake-up call to revitalise the EU’s Single Market, emphasising the need for decisive action. Its vision largely hinges on legal harmonisation within Europe, building on early efforts to liberalise markets and establish a truly integrated European market.

Despite efforts, “integration fatigue” remains a significant challenge due to legal fragmentation across European economies. Previous reports, from the Cecchini Report in 1992 to the Europe 2020 Strategy, have highlighted persistent issues like regulatory divergences and declining political support for market integration. Despite numerous proposals, progress has been limited, and many challenges persist or have worsened (see Section 2).

An analysis of EU reports reveals a shift in policy priorities over time. Initially, there was a strong focus on liberalisation and market opening, with less attention given to state aid and industrial policymaking. The Letta Report highlights the importance of regulatory convergence and harmonisation, reflecting a deeper understanding and recognition of the drivers of EU competitiveness. The rise of nationalism and a shift towards “Strategic Autonomy” within the EU have hindered crucial market reforms. This highlights the importance of aligning laws across Member States to strengthen and reinforce EU’s economic resilience and international competitiveness (see Section 3).

EU institutions and Member State governments should set specific goals for “legal harmonisation in the EU.” This shift would address real challenges faced by businesses and citizens, and build political will for necessary reforms. Prioritising legal harmonisation would enhance internal cohesion and align national laws with Union-wide goals. An actionable roadmap – potentially with a 2028 deadline – is crucial to address the substantial gap between ambitious EU strategies and Europe’s economic realities. (see Section 4).

Implementing sector-specific and horizontal policies in a new regulatory regime would improve cross-border operations and competitiveness. The Letta Report advocates for a European Code of Business Law to establish a unified regulatory framework, introducing a 28th legal regime to address national regulation discrepancies. Extending this regime to include tax and labour market policies would significantly enhance cross-border operations.

The EU and Member State governments can eliminate substantial internal barriers by prioritising key horizontal policies affecting all businesses, such as fragmented tax laws, labour market policies, and social security systems. Simplifying and harmonising these policies on the basis of the facilitation of four freedoms is crucial for unlocking the Single Market’s potential for businesses and workers, boosting the EU’s global competitiveness.

Allowing coalitions of willing countries to advance in certain areas of legal integration provides a viable solution to the long-standing Single Market “fatigue”. By enabling smaller groups of Member States to pursue integration in specific areas, the EU can bypass the constraints imposed by rigid voting requirements and achieve greater agility, accountability, and acceptance in EU law-making. This approach not only fosters flexibility but also upholds the fundamental principles and objectives of the EU. To ensure the integrity of the EU legal order and prevent unjustified barriers or discrimination against non-participating members, it is essential to establish safeguards and oversight mechanisms. These measures would maintain cohesion within the Union while allowing for progressive legal integration among willing Member States.

1. Introduction

The EU, with its 27 countries and 24 official languages, faces significant trade and business challenges due to its linguistic diversity.[1] This multilingualism complicates cross-border business activities, from contractual agreements to daily communications, increasing operational costs and perceived legal risks for businesses within the Single Market.[2] Unlike the US, where English potentially mitigates the negative impacts of internal regulatory barriers, the EU’s linguistic diversity and legal fragmentation require additional resources for translation, legal counsel, and compliance management. This results in higher operational costs and complexities, impacting business efficiency and trust in the Single Market.[3]

The EU’s historical linguistic and regulatory diversity have long presented substantial challenges for commerce across its member states. Despite ambitions for a more integrated Europe, progress has been limited, with the Single Market far from complete. National political and protectionist tendencies often prioritise individual state interests over collective European goals, obstructing the vision of a seamless economic area allowing free movement of goods, services, people, and capital.

The Letta Report of April 2024 was commissioned by the Belgian and Spanish governments. Titled “Much More Than a Market,” it proposes strategies to modernise the European Single Market to address pressing challenges for Europe. The report was authored by Enrico Letta, former President of the Italian Council and President of the Jacques Delors Institute, together with the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen.[4] It is supported by the entire European Council. The Letta Report urgently calls for the rejuvenation of the EU Single Market.

The significance of the Letta report can be questioned, given the numerous previous attempts of creating a genuine internal market within Europe. Rising nationalism and shifts towards “Strategic Autonomy” in the EU have stalled essential market reforms and fostered protectionist policies, undermining global trade norms and the liberalisation progress achieved in the past decades. If the European Parliament shifts further towards national-populist representation following the 2024 elections, these inward-oriented, protectionist tendencies could be exacerbated.

To counteract such developments and achieve a truly unified market, the EU needs a deep re-evaluation of its integration strategies, addressing legal fragmentation and cultural barriers through substantial reforms. The success of new initiatives, such as the Letta Report and the upcoming Draghi Report, in increasing the EU’s international competitiveness heavily depends on overcoming national interests, prioritising policy coherence and enforcement, and committing to deep, structural reforms that align with the broader goals of market integration and competitiveness. This requires a shift in political will across Member States and a commitment to pragmatic and sustained policy action.

In this paper, we address the overarching question of the relevance of the Letta Report, considering the countless reports and EU initiatives that preceded it in the past 30 years or so. We highlight the most significant and persistent structural problems of EU economic integration and discuss potential policy priorities, from harmonising major horizontal policies to reforming the mode of political and economic integration, with the political objective of significantly enhancing the EU’s economic competitiveness and securing its economic future.

Section 2 delves into the gap between political ambitions and the legal and economic realities in the EU. Section 3 offers an overview of several high-level EU reports and strategies, highlighting the challenges in their implementation. Drawing from the in-depth analysis conducted in the paper, Section 4 outlines what we consider to be ambitious yet relevant policy recommendations.

[1] See, e.g. EPRS (2018). Languages and the Digital Single Market. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/625197/EPRS_BRI(2018)625197_EN.pdf.

[2] As concerns differences in language, research finds, for example, that a 10% increase in the Language Barrier Index can result in a 7% to 10% decrease in trade flows between two countries. See Lohmann, J. (2011). Do language barriers affect trade? Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165176510003617.

[3] ERT (2021) Renewing the dynamic of European integration: Single Market Stories by Business Leaders. Available at: https://ert.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/ERT-Single-Market-Stories_WEB-low-res.pdf

[4] See Letta, E., (2024). Much more than a market. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/ny3j24sm/much-more-than-a-market-report-by-enrico-letta.pdf. The Letta Report focuses on building the Single Market of the future, stressing challenges such as the Europe’s economic security and the digital and green transitions. The analysis is within the scope of the mandate received from the EU Council and the Commission, developed under the Belgian, Spanish, and Hungarian trio Presidency of the Council of the EU. The aim of the report is to provide concrete and operational contributions to the work programs of these institutions and to complement Mario Draghi’s report on the future of European competitiveness. The report acknowledges the profound support and passionate engagement of the European Commission, including its President, Commissioners, Directors, Officials, and especially those responsible for the Single Market, including Commissioner Thierry Breton, Belgian Vice Prime Minister Dermagne, and his Ministry in the Belgian Presidency.

2. The Gap between Political Ambition and Legal Realities in the EU

The US has shown more economic resilience over the past two decades than the EU, attributed to business-friendly policies, lower taxes, and a robust innovation ecosystem driven by venture capital and risk-taking.[1] This has fostered diverse commercial and research clusters, enhancing global competitiveness. Conversely, the EU faces slower productivity growth and higher unemployment, partly due to stringent labour market regulations and social welfare emphasis, which, while providing stability, increases labour costs and bureaucracy. Despite initiatives like Horizon Europe, the EU’s fragmented regulatory environment and complex bureaucracy impede rapid technology adoption and scaling of start-ups.[2]

Economic indicators highlight distinct trends: the US’s dynamic GDP growth and declining unemployment rates contrast sharply with the EU’s low productivity and high unemployment rates, especially in countries like Greece, Spain, and Italy.[3] The US’s approach, characterised by lower taxes on labour and corporate income and less regulation, incentivises investment and entrepreneurship. This has resulted in the world’s most robust innovation ecosystem, with thriving commercial and research clusters. In contrast, the EU’s stringent labour market regulations and emphasis on worker protections, while providing social stability, lead to higher labour costs and bureaucratic hurdles, affecting international competitiveness. Initiatives like Horizon Europe aim to boost innovation, but the EU’s fragmented regulatory landscape often hinders the rapid adoption of new technologies and the growth of start-ups.

Despite past efforts by leaders like Merkel, Hollande, and Sarkozy to promote European unity, recent years have seen reduced political will to enhance the Single Market through liberalisation and harmonisation.[4] Political tensions and nationalistic sentiments have repeatedly prevented the realisation of a seamless internal market.

The European Single Market, designed to enhance economic performance through the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people, faces significant challenges due to prevalent nationalistic and protectionist tendencies.[5] These tendencies prioritise state interests over collective EU benefits, hindering the completion of a unified market. Political tensions expose the struggle to balance national sovereignty with EU integration goals. Recent calls for a substantially more interventionist approach in EU trade and industrial policy, as illustrated by President Macron, highlight the resurgence of protectionism.[6] This rising nationalism has stalled crucial reforms and eroded earlier liberalisation efforts,[7] leading to a new focus on “Strategic Autonomy”[8] and more restrictive practices, which challenge global trade norms and the WTO.

The theoretical advantages of deeper legal and economic integration among EU Member States are evident, promising increased competitiveness against global powers like the US and China. However, translating this theoretical framework into practical reality reveals a different landscape, where national interests often take precedence over collective EU economic policies.[9] A significant challenge lies in attaining regulatory and economic convergence among Member States, a process that has been slow and marred by obstacles. For instance, despite the European Commission’s efforts to advance major Single Market initiatives, a significant portion of proposed legislative measures have faced delays or hurdles in adoption by the European Council.[10]

Under the von der Leyen Commission, the focus of economic and technology policymaking has shifted, expanding to address not only legal fragmentation within the EU but also economic dependencies arising from interactions with non-EU nations, as perceived by policymakers. This shift in focus has led to an allocation of excessive resources towards negotiating new EU legislation rather than ensuring the effective implementation and enforcement of existing regulations, thereby diverting attention from internal integration challenges.[11]

The persistent lack of economic integration within the EU has contributed to Europe’s declining role in today’s global supply chain landscape. Over time, as European economies have undergone structural changes driven by technological advancements and globalisation, the incompleteness of the EU market in adapting to these changes has become increasingly apparent. Internal barriers, lack of harmonised rules, and the complexity of regulatory frameworks have all posed significant challenges to achieving legal and economic integration.

A notable example highlighting the hurdles to economic integration is the services sector, which plays a pivotal role in the EU economy, accounting for a substantial portion of GDP.[12] Unlike goods trade, which benefits from zero tariffs, the services sector faces significant legal fragmentation, primarily governed by national rather than EU-wide regulations.[13] This disparity underscores the complexity of achieving true economic integration within the EU.

Numerous reports, both historical and contemporary, have documented the challenges facing EU economic integration. For instance, the recent Single Market Obstacles Technical Study gives a very comprehensive and detailed overview of very specific policy barriers that prevent cross-border commerce in the EU and impede Member States’ legal and economic integration respectively. Illustrative examples from this study are presented in Box 1 below.[14]

Box 1: Barriers to trade and investment within the EU (excerpt)

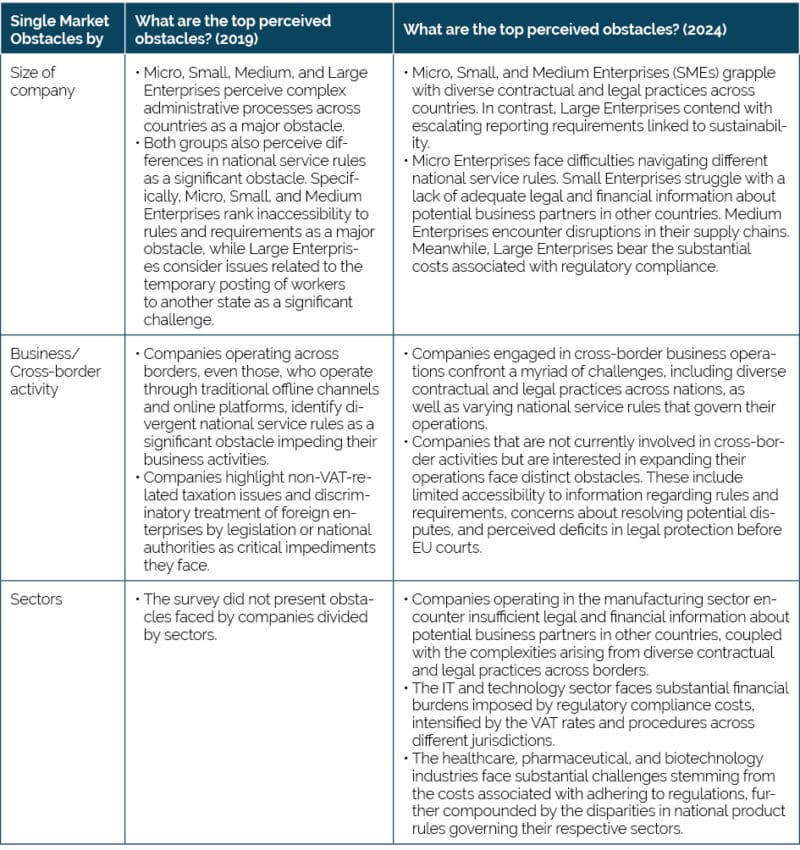

The results of an older Eurochambres survey, dating back to 2019, when the von der Leyen Commission entered office, mirror the existing apprehensions of EU businesses concerning the disparities in contractual and legal practices across Member States.[15] These concerns are compounded by complex service regulations and insufficient access to critical information (see Table 1). A significant 80 percent of respondents cited complicated administrative procedures as their primary obstacle. Following closely behind were worries about varying national service regulations, noted by 72 percent of participants, and the lack of accessible information regarding regulatory requirements, identified by 69 percent of those polled. These findings underscore the persistent challenges that remain unaddressed despite the apparent need for substantial policy reforms to tackle them effectively.[16] Alternatively, a 2024 Eurochambres survey reveals that, even after six years, EU businesses remain deeply concerned about discrepancies in contractual and legal practices across Member States due to varying service regulations, as well as limited access to information about different rules and requirements.[17]

Table 1: Top obstacles faced by businesses in 2019 and 2024[18]

Moreover, both surveys highlight that when these obstacles are viewed through the lens of “internal trade policy,” progress towards economically integrating EU Member States has, at best, stagnated. This is demonstrated by a notable rise in barriers to intra-EU trade, accompanied by an insufficient enforcement of Single Market principles. Legal fragmentation within the EU signifies a concerning decline in meaningful political cooperation, leading to increased barriers to intra-EU trade.

A detailed analysis by ECIPE examining regulatory trade restrictiveness and regulatory fragmentation across two periods highlights the challenges faced within the Single Market for services. The findings reveal a significant tightening of regulations affecting services trade among EU Member States, alongside a reduction in measures facilitating freer trade (see Figure 1), which in many cases will hinder the European economies’ adaptability to emerging economic and technological trends.

Figure 1: Development of Services Trade Restrictiveness, 2014-2018 and 2018-2022 Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, and values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, and values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

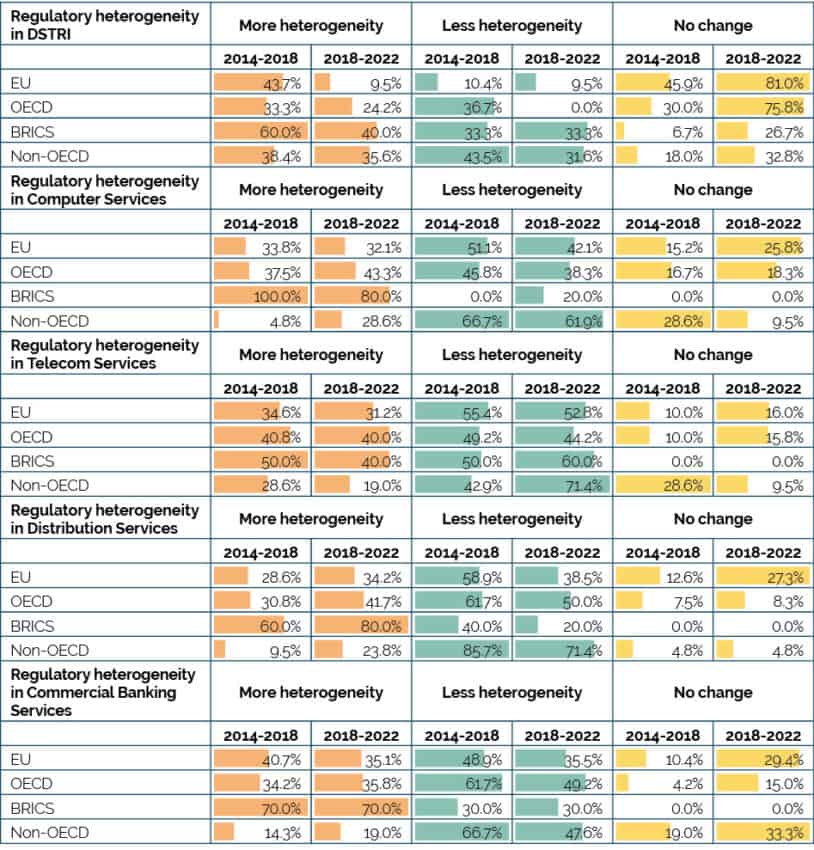

Furthermore, as concerns regulatory fragmentation, while there is a “statistical” shift towards a more harmonised regulatory framework for digital services trade within the EU, the substantial increase in the “No change” category suggests a reluctance to align multiple regulations across the Single Market See Table 2). This raises concerns about the EU’s proactive adjustment to foster innovation and competitiveness. To be fair, outside the EU, despite a statistical decline in regulatory heterogeneity, the rise in the “No change” category also indicates stagnation in adapting uniform regulatory frameworks, posing risks to capitalising on digital trade’s potential.

Table 2: Development of heterogeneity in services trade restrictiveness, 2014-2018 and 2018-2022 Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More heterogeneity/fragmentation”, and values < 0 equals “Less heterogeneity/fragmentation”.

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More heterogeneity/fragmentation”, and values < 0 equals “Less heterogeneity/fragmentation”.

[1] Peter G. Foundation (2023, April 7). Six Charts That Show How Low Corporate Tax Revenues Are In The United States Right Now. Available at: https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2023/04/six-charts-that-show-how-low-corporate-tax-revenues-are-in-the-united-states-right-now ; Koop, A. (2022). Which are America’s best states for business? Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/marketsranked-america-s-best-states-to-do-business-in/ ; Greenwood, J., Han, P., and Sanchez, J. (2022) Venture Capital:

A Catalyst for Innovation and Growth. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Second Quarter 2022, 104(2), pp. 120-30. Available at: https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/2022/04/21/venture-capital-a-catalyst-for-innovation-and-growth.pdf

[2] See, e.g., ResearchFDI (2023). Why The US Leads The World In Entrepreneurship And Innovation. Available at: https://researchfdi.com/resources/articles/why-the-us-leads-the-world-in-entrepreneurship-and-innovation/.

[3] IMF (2024). Unemployment rates. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/LUR@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD.

[4] Normanton, T. One step forward, two steps back—European regulation grapples with the same old problems. (January 4, 2024, Waterstechnology). Available at: https://www.waterstechnology.com/trading-tech/7951575/one-step-forward-two-steps-back-european-regulation-grapples-with-the-same-old-problems

[5] Single European Act, Official Journal of the European Communities L 169 of 29 June 1987; the aim was to guarantee freedom not only between EU Member States, but also European Economic Area (EEA) and European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

[6] For a recent example, see, e.g., Emmanuel Macron (2024). Europe – It Can Die. A New Paradigm at The Sorbonne. Available at: https://geopolitique.eu/en/2024/04/26/macron-europe-it-can-die-a-new-paradigm-at-the-sorbonne/.

[7] See, e.g., Brunazzo (2022). The Politics of EU Differentiated Integration: Between Crises and Dilemmas. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03932729.2022.2014103.

[8] See: 2022 State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_5493; President Macron gives speech on new initiative for Europe, Available at: https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2017/09/26/president-macron-gives-speech-on-new-initiative-for-europe and ‘Strategic autonomy for Europe – the aim of our generation’ – speech by President Charles Michel to the Bruegel think tank, Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/09/28/l-autonomie-strategique-europeenne-est-l-objectif-de-notre-generation-discours-du-president-charles-michel-au-groupe-de-reflexion-bruegel/

[9] Bauer, M., Pandya, D. (2023). EU Autonomy, the Brussels Effect, and the Rise of Global Economic Protectionism. (No.2/2023). ECIPE Occasional paper

[10] European Commission, (2018) ‘The Single Market in a changing world: A unique asset in need of renewed political commitment.’ Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/32662

[11] ERT. (2024). Single Market Obstacles Technical Study. Available at: https://ert.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ERT-Single-Market-Obstacles_Technical-Study_WEB.pdf

[12] Eurostat. (2021) Services represented 73% of EU’s total GVA. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20211021-1

[13] Erixon, F. (2016) What is Wrong with the Single Market? ECIPE, Available at: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/5Freedoms-012016-paper_fixed_v2.pdf

[14] Ibid, also see: ERT. (2024). Single Market Compendium. Available at: https://ert.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Single-Market-Compendium-of-obstacles-8-March-2024-1.pdf

[15] Eurochambres (2019) Business Survey The state of the Single Market: Barriers and Solutions. Available at: https://www.eurochambres.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Business-Survey-The-state-of-the-Single-Market-Barriers-and-Solutions-DECEMBER-2019.pdf

[16] Ibid

[17] Eurochambres (2024) Overcoming Obstacles, Developing Solutions. Available at: https://www.eurochambres.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/2024-Eurochambres-Single-Market-Survey-Full-Report.pdf

[18] Several of these challenges overlap each other, and hence for a distinct overview, top unique challenges for each category have been covered.

3. What to Make of Well-intended Reports and Strategies

The recent Letta Report highlights the need for political realism in revitalising the Single Market, suggesting a focus beyond economic metrics to include governance and policy execution. However, effective change requires more than well-intended reports; it requires sustained political will and cohesive action among Member States. Historical EU strategies often faltered due to a lack of implementation, raising questions about the realistic expectations for the Letta Report’s impact.

3.1 Historical context of EU strategies and reforms

The EU has repeatedly sought to strengthen the Single Market through various reports and strategies, which often lacked tangible progress. Analysis of past initiatives reveals a shift from liberalisation and competition to regulatory convergence and state aid, reflecting changing political priorities. Reports like the Cecchini Report (1988) and the White Paper Growth (1994) focused on liberalisation, and market opening, while more recent reports like the Monti Report (2010) and the Letta Report (2024) emphasise regulatory harmonisation and competitiveness. This evolution reflects the complexities of achieving a unified market, underscoring the need for aligning regulatory frameworks to enhance global competitiveness, potentially through state aid and industrial policies. Despite recognising the importance of liberalisation and harmonisation, the EU continues to struggle with substantial political and bureaucratic challenges in realising these goals.

Annex 1 provides an overview of major reports and strategies shaping the evolution of the EU’s Single Market ambition. Initially, the focus was on economic integration and achieving a unified market. Over time, there has been a shift towards enhancing economic growth, competitiveness, and positioning the EU as a dynamic, knowledge-based economy. However, despite numerous proposals, tangible progress has been limited, as indicated by recurring discussions and stagnant indicators in areas like economics, trade, and technology.

A content analysis (see Figure 2) reveals changing policy priorities across EU reports. Initially, there was a strong emphasis on liberalisation and market opening, with much less focus on state aid. However, later reports increasingly prioritised state aid measures to strengthen European industries, reflecting a broader shift in policy approaches. Recent reports, including the Letta Report, emphasise regulatory convergence and harmonisation, indicating a renewed understanding and recognition of the deeper structural challenges in achieving a truly integrated Single Market.

What’s more, there is a clear correlation between mentions of liberalisation, harmonisation, and competitiveness across reports. Liberalisation is seen as a means to enhance competitiveness within the Single Market by promoting innovation and efficiency. Similarly, harmonisation is viewed as crucial for creating a competitive environment within the EU by reducing regulatory barriers and fostering a level playing field for businesses. These trends underscore the EU’s ongoing efforts to enhance its competitiveness in the global economy through regulatory convergence and fostering a business-friendly environment.

Figure 2: Number of mentions of terms associated with the development of the European Single Market[1] Source: Commissioned reports (Cecchini, Monti, Letta Report), EU White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness, Employment, European Commission Strategies (Lisbon Agenda, and EU 2020 Strategy).

Source: Commissioned reports (Cecchini, Monti, Letta Report), EU White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness, Employment, European Commission Strategies (Lisbon Agenda, and EU 2020 Strategy).

The challenges highlighted in various reports remain highly relevant in contemporary discussions on the Member States’ legal and economic integration within the EU.[2] As emerging technologies and businesses continuously reshape economies globally, there remains a need to reassess obstacles stemming from declining political and social support for market integration efforts. Diminished confidence in the EU’s ability to deliver conducive legislative outcomes for commerce and intra-EU trade underscores the urgency for more effective EU policymaking.

While the Letta report may steer discussions and provide a basis for more concrete actions, its impact will critically depend on decisive and unified political actions across the EU, a significant hurdle historically. To effectively implement meaningful changes, particularly through regulatory harmonisation among Member States, a reform of the political mode of integration could become essential; without it, success is highly unlikely.

One standout effort from the European Commission in this regard was the “Juncker White Paper on the Future of the European Union”, introduced in 2017, which outlined five scenarios for the EU’s trajectory post-Brexit and amid other challenges. While it sparked debates and raised awareness of potential paths for the EU, it lacked concrete proposals to address pressing issues like legal fragmentation and economic disparities. However, may still serve as a valuable starting point for discussions on EU policymaking.[3]

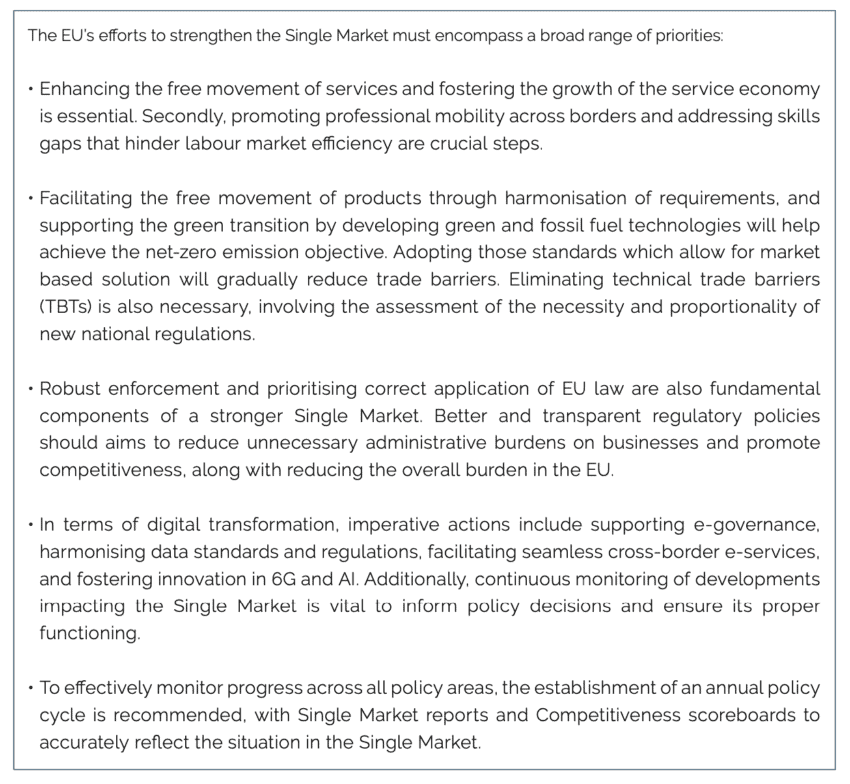

In another concerted effort, a recent call for action led by Finland and 14 other EU Member States highlighted measures to enhance the EU’s competitiveness through a better functioning Single Market. Recommendations included deepening integration, removing barriers in high-growth service sectors through digitalisation and sustainability efforts, and prioritising fair competition and participation in the global economy.[4] Box 2 outlines major recommendations from the White Paper spearheaded by Finland. These recommendations cover various policy areas such as services, professional mobility, product movement, enforcement of EU law, and digital transformation. Priorities include harmonising rules, reducing regulatory burdens, and establishing mechanisms for monitoring progress and ensuring consistency across sectors. However, limited in scope, these measures alone are unlikely to make a significant difference in making the EU “systemically” more competitive.

However, it is important to recognise that these measures alone are unlikely to make a significant difference in making the EU more competitive. A comprehensive approach that includes these initiatives, along with broader economic and structural reforms, is necessary to truly enhance the EU’s competitiveness on the global stage.

Box 2: Major recommendations made in the White Paper led by the Finnish government

3.2 The significance of the Letta Report

Publicised as a fresh approach to revitalising the European Single Market, the Letta Report mirrors past reform endeavours such as the Lisbon Strategy[5] and the EU2020 strategy,[6] both of which faced implementation challenges despite ambitious beginnings. This recurrence highlights a persistent issue in EU policymaking: the gap between ambitious visions and effective execution. It remains uncertain whether this report will make a significant impact where previous efforts have faltered.

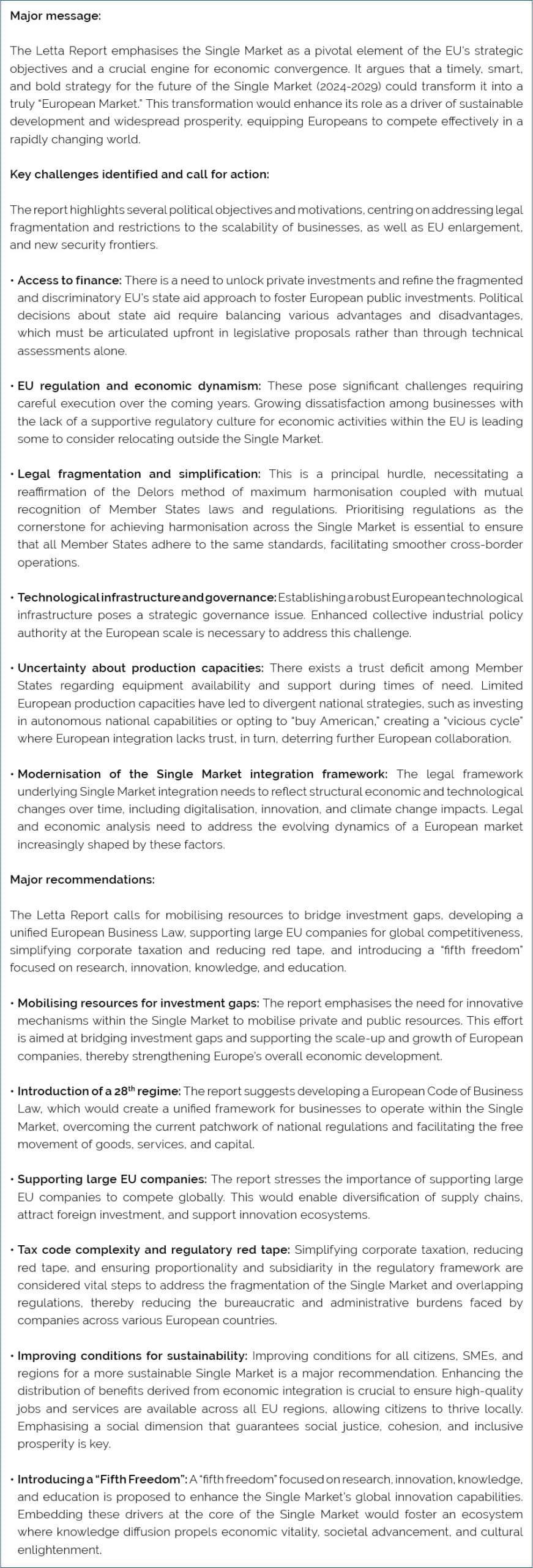

Notably, while advocating for essential reforms to address flaws in Single Market policies, the report lacks a detailed blueprint and relies heavily on broad concepts rather than practical solutions. It highlights concerns over regulatory developments in Brussels and national capitals. It also promotes the idea of more industrial policy and subsidies, albeit funded by the EU rather than national governments (see Box 3).

However, its emphasis on industrial subsidies raises questions about their effectiveness in fostering innovation and sustainable growth, especially considering the recent struggles of companies receiving substantial state support. Thus, while the Letta Report contributes to the ongoing political debate, its proposals demand rigorous evidence and careful consideration to ensure meaningful impact and avoid unintended consequences.[7]

The Letta Report rightfully underscores the necessity of tackling legal fragmentation and enhancing economic integration to boost the EU’s global competitiveness and long-term stability. It also calls for a pragmatic approach to regulatory improvements, aiming for increased speed and efficiency. Achieving these reforms, however, requires strong political commitment and cohesive action among Member States, addressing the recurring issue of ambitious visions versus effective execution in EU policymaking. In anticipation of political tensions, the report stresses that without tangible changes, the EU risks continued stagnation and diminished economic performance.

The report advocating for a reimagined European Single Market, promising both freedom of movement and the “freedom to stay” for European citizens, presents a vague and somewhat populist notion of EU policymaking. It lacks concrete strategies, raising concerns about necessity, efficacy, and proportionality. Similarly, the proposal for a “Fifth freedom,” centred on research, innovation, knowledge, and education, echoes this sentiment, lacking clear policy recommendations and overlooking key economic and societal development aspects.

Box 3: The Letta Report: Major message, challenges, recommendations

[1] While cooperation and convergence are distinct terms, the reports have used these terms to represent levels of integration and unification showcasing that the concepts are interlinked.

[2] In addition to the reports mentioned above, several other reports were identified whose aim and objectives were also strengthening the market by eliminating barriers that caused fragmentation on a daily basis. These include the Sapir report, Gonzalez report, Five President’s Report, Werner Report, McDougall Report, Lamfalussy Report, and Larosière Report.

[3] See, e.g., Janning, J., (2017) Scenarios for Europe: Deciphering Juncker’s White Paper. Available at: https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_scenarios_for_europe_deciphering_junckers_white_paper/

[4] Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland. (2024) Finland proposes new horizontal EU Single Market strategy. Available at: https://tem.fi/en/-/finland-proposes-new-horizontal-eu-single-market-strategy. Other Member Countries include: Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden

[5].European Parliament (2000) Lisbon European Council 23 and 24 March 2000 Presidency Conclusions. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_en.htm

[6] European Commission (2010a) Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Communication from the European Commission, Brussels, 3.3.2010, COM(2010) 2020 final

[7] Erixon, F., (2024, April 17). The Letta Report – the Good and the Bad! ECIPE. Available at: https://ecipe.org/blog/the-letta-report-the-good-and-the-bad/

4. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The EU and Member State governments must prioritise key strategic areas to consolidate the Single Market and address the Single Market fatigue more effectively. These priorities include robust policy enforcement and simplified, harmonised regulations for businesses operating across borders within the EU27.

Focusing on horizontal policies that apply to any European business, regardless of industry, policymakers could bring forth substantial economic benefits swiftly. An ambitious approach is essential for realising the full potential of an integrated and dynamic internal market. EU policymakers should shift their focus from the broad concept of the “Single Market” to “legal harmonisation in the EU,” as emphasised by the Letta Report, to address protectionist policies, mobilise support for structural reforms, and realise a truly integrated market.

A bold EU strategy with actionable policies should support cross-border economic activity, innovation, and entrepreneurship, ultimately strengthening the EU’s global economic position and improving the welfare of its citizens. Fostering cooperation and trust and allowing coalitions of willing countries to advance specific policies would promote flexible and more effective integration. To safeguard the integrity of the EU legal order and prevent unjustified barriers or discrimination against non-participating members, it is crucial to implement oversight mechanisms. These measures will ensure cohesion and fairness within the Union while permitting progressive legal integration among willing Member States.

4.1 A new rhetoric for the EU: emphasising legal harmonisation

Given the continuous emphasis on the EU’s Single Market and the sobering realities highlighted in the Letta Report, EU policymakers should shift their focus from the broadly framed concept of the “Single Market” to the more specific and action-oriented theme of “legal harmonisation in the EU.”

The Letta Report highlights the Single Market’s incompleteness and the persistent barriers that hinder its full realisation. Addressing protectionist policies and nationalistic tendencies that favour individual state interests over collective European benefits is thus becoming crucial. Focusing on and institutionalising the term legal harmonisation provides strategic advantages by enabling more realistic and grounded discussions that resonate with the challenges businesses and citizens face.

Moreover, by adopting a more focused narrative, the EU and willing Member State governments could better mobilise support towards the tangible benefits of a truly integrated market, supporting a broader consensus for deep, structural reforms.

4.2 Changing the mode of political integration to integrate, simplify, and liberalise

The EU’s ambitious strategies for economic integration often face significant challenges, leading to a gap between policy objectives and practical execution. Addressing this requires a comprehensive approach, including a critical reassessment of the power dynamics between EU institutions and Member States. A more flexible and adaptive integration model is essential, promoting cooperation, solidarity, and trust among member countries to navigate complex geopolitical dynamics effectively.

EU policymakers should thus start working towards a more cohesive and effective institutional regime that minimises fragmentation and enhances cooperation across Member States governments. Indeed, numerous suggestions have already been proposed to resolve the EU’s fundamental institutional challenge. For example, in a report from 2023,[1] a Franco-German expert working group put forth a proposal suggesting immediate actions to enhance the EU’s functionality and suggests more substantial reforms, including treaty revisions, for the upcoming legislative term from 2024 to 2029. The authors emphasise the need for the EU to adapt institutions and decision-making processes in preparation for future enlargements, suggesting significant modifications to enhance efficiency and accountability. As already seen earlier in the Juncker White Paper (see above), the authors of the Franco-German report explore the concept of allowing a coalition of willing countries to advance certain policies, even if other Member States choose not to participate. Clearly, considering the incompleteness of the Single Market with regards to sector-specific and horizontal policies, this approach may facilitate progress and deeper integration among agreeable governments without requiring unanimous (or qualified majority) consent across all EU countries .

Achieving a truly integrated Single Market may thus necessitate a shift in political mind-set at both the EU and Member State levels. This includes new political leadership and also a move away from Franco-German-centric integration modes. Strengthening enforcement mechanisms and simplifying regulatory frameworks, particularly in taxation and labour markets, will create a more conducive environment for economic activity and innovation. Harmonising standards across Member States is crucial to fostering a dynamic and competitive landscape.

The EU must address fragmentation in digital policies to reduce complexity for businesses.[2] Ensuring uniform policy enforcement across Member States is vital for achieving real progress. A centralised oversight mechanism is needed to monitor, report, and ensure compliance with EU regulations. Enhanced enforcement will facilitate the adoption of regulatory simplifications, providing clear incentives for businesses and fostering a conducive environment for economic activity.

4.3 Policy priorities

Building on the research presented above, the following recommendations aim to address the current challenges and unlock the potential of the European Single Market by simplifying and harmonising regulations for businesses operating across borders.

Policy recommendations for simplifying and harmonising regulations: To address the challenges and unlock the potential of the European Single Market, EU policymakers and national governments should focus on simplifying and harmonising regulations for all businesses wishing to operate across borders. By targeting horizontal policies applicable to all European businesses, regardless of industry, substantial economic benefits can be achieved.[3]

Simplifying key horizontal business regulations: Harmonising tax policies, such as labour income taxes, corporate taxes, and sales taxes, will substantially enhance Europe’s business environment and investment attractiveness. Aligning labour market policies and social security systems to reduce legal uncertainties and compliance costs, along with establishing unified corporate taxation rules, would ensure fairer competition. This does not mean harmonising tax rates or social security contributions, but implementing a uniform rulebook would simplify operations for companies, especially SMEs, and make cross-border business easier and more efficient.

Exploring the possibilities and limitations of a 28th legal regime: The concept of a 28th legal regime, as vaguely proposed by the Letta Report, refers to the establishment of a unified set of regulations that would operate alongside the national laws of EU Member States. The regime could provide a single, coherent framework applicable to businesses operating across borders within the EU, thus simplifying the regulatory landscape and reducing the burden of navigating multiple languages and legal systems.

Harmonising digital regulations: Unifying existing digital regulations is crucial. Aligning data policies and competition enforcement would reduce compliance costs and legal uncertainties, including SMEs. Ensuring consistent enforcement across Member States would prevent overlapping and contradictory regulations, fostering a more cohesive digital (and non-digital) market.

Strengthening impact assessments: Enhancing the impact assessment rulebook for new EU regulations by making mandatory detailed, country-specific analyses will provide a clearer understanding of their effects. Increasing the powers of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) and ensuring transparency in assessments could lead to more informed policymaking and better outcomes for individual Member States.[4]

Improving enforcement mechanisms: Establishing a central EU enforcement body to oversee Single Market regulations may be necessary. Conducting regular audits and addressing regulatory disparities by mitigating over-regulation in some Member States and under-regulation in others could help achieve better and more uniform compliance and strengthen the Single Market.

Facilitating technology diffusion: Avoiding regulations that hinder the seamless transfer and adoption of innovative technologies will enhance the EU’s global competitiveness. Increasing cross-border opportunities for technology startups and SMEs, while fostering international collaboration with technologically advanced non-EU entities, will drive economic growth and innovation across all Member States.[5] This may require bold reforms in non-digital regulations, including those affecting, for instance, taxi markets, national healthcare, and public services, to ensure a conducive environment for technological advancements across intra-EU borders.

Addressing economic opportunities and professional qualifications: Concerning the “right to stay” as proposed in the Letta Report, EU and national governments should prioritise measure to increase economic opportunity. For instance, aligning formal professional qualifications with labour market demands and incentivising continuous professional development would enhance employability, labour mobility, and economic efficiency. Simplifying regulatory frameworks for professional qualifications and licensing will remove barriers to entry, fostering a more vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem. It is crucial to stress that there is no need to regulate to the bottom. Instead, maintaining high standards while streamlining compliance requirements ensures that quality and competitiveness are upheld. Enhancing access to finance, simplifying market entry processes, and supporting the integration of advanced technologies such as AI and blockchain into traditional industries will further drive growth and innovation.

[1] Report of the Franco-German working group on the EU institutional reform, Available at: https://institutdelors.eu/en/publications/sailing-on-high-seas-reforming-and-enlarging-the-eu-for-the-21st-century/

[2] For a compressive overview of EU digital regulations see Bruegel (2024). Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/Bruegel_factsheet.pdf.

[3] See, e.g. ECIPE (2023). What is Wrong with Europe’s Shattered Single Market? Lessons from Policy Fragmentation and Misdirected Approaches to EU Competition Policy. Available at: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ECI_23_OccasionalPaper_02-2023_LY04.pdf.

[4] See, e.g., ECIPE (2022). The Impacts of EU Strategy Autonomy Policies – A Primer for Member States. Available at: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ECI_22_PolicyBrief_AutPol_09_2022_LY02.pdf.

[5] See, e.g., ECIPE (2024). ICT Beyond Borders: The Integral Role of US Tech in Europe’s Digital Economy. Available at: https://ecipe.org/publications/the-role-of-us-tech-in-europes-digital-economy/. Also see ECIPE (2024). Openness as Strength: The Win-Win in EU-US Digital Services Trade. Available at: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_05-2024_LY03.pdf.

Annex 1: Overview of Objectives and Recommendations of Major Single Market Reports and Strategies (1992-2024)

THE CECCHINI REPORT on the COST OF NON-EUROPE (1988)

The European Commission tasked Paolo Cecchini, Head of the Task Force of the Commission of the European Communities for the enlargement of the Communities, to research a series of papers focusing on the ‘costs of non-Europe.’ The resulting report brought attention to the substantial economic burdens imposed by existing barriers on the Member States of the European Economic Community (EEC).[1]

Political objectives and motivation:

The main goals included establishing a borderless market to foster scientific, technical, and commercial cooperation across the European Community, thereby improving its overall competitiveness. Another key aim was increasing employment rates and economic growth through better management of economic policies, creating a balanced market that could integrate smoothly into the global economy. There was also a re-emphasis on the original objective of developing both the social and economic dimensions of the market, creating unified Community policies that would lead to shared prosperity. The report documented the economic benefits and potential welfare gains from achieving a fully integrated internal market. It identified public sector procurement as the top priority for integration. The report found that by eliminating inefficiencies in public sector procurement caused by barriers to intra-EU trade, annual savings ranging from EUR 8 to 19 billion (in 1984 prices) could be realised in the five member states studied at that time.

Identified challenges and analysis:[2]

The report highlighted the fragmentation of the European economy into 12 distinct national markets due to the heavy costs associated with market barriers at that time. This fragmentation was exacerbated by the emergence of new regulatory and standardisation initiatives across member states. The presence of such barriers inhibited the free flow of goods, services, and capital across borders, impeding economic integration and market efficiency within the European Community. The barriers were categorised into three main types: physical, technical, and fiscal. Physical barriers like border controls, customs procedures, and bureaucratic hurdles created inefficiencies and delays in cross-border trade and movement of goods. Technical barriers such as divergent product standards, regulations, conflicting business laws, and protected public procurement markets made it complex for businesses to operate across multiple jurisdictions, potentially stifling innovation and competitiveness. Fiscal barriers like varying VAT and excise duty rates distorted market competition and disincentivized cross-border trade and investment. The significant unrealised growth potential in the service sector due to divergent regulations and practices across Member States impeded free flow of services and fair competition. This underscored the importance of regulatory harmonisation to unlock the sector’s full potential and drive economic growth.

Major recommendations:

The report emphasised that economic gains could be realised from the actual integration of European financial services markets. The underlying focus of the report stemmed from the “non-price” factors that are central to businesses, and the role of innovation in driving the expansion of technology sectors, given the positive link between innovation and competition for economic growth. To safeguard fair competition and prevent the resurgence of barriers post-removal, it advocates for robust enforcement of competition policy by both community and national administrations. This entails ensuring that eliminated barriers aren’t replaced by anti-competitive practices, thus enabling firms to compete fairly with their commercial counterparts. Moreover, for market integration to be truly effective, competition policy should facilitate the welcoming of parallel imports wherever unjustified price differences exist. The distribution of gains from market integration must be fair, just as the distribution of associated costs must be equitable across stakeholders. Economic policy must be align with integration efforts which would result in increased sales and output – favourable expectations. All of these will need to be backed by well-coordinated, growth-oriented macroeconomic policies. Furthermore, monetary policy must continue promoting a zone of stability within Europe by removing barriers between financial markets and fully liberalising capital movements.

WHITE PAPER ON GROWTH COMPETITIVENESS AND EMPLOYMENT (1994)

The Commission during the Copenhagen European Council in 1993 was asked to present a White Paper on a medium-term strategy for growth, competitiveness and employment. The objective underlying the white paper was to create a new service market which maximised the impact on employment, removed regulatory obstacles that would allow the development of new markets and create the conditions for European companies to develop their strategies in an open internal and competitive environment not only on an intra-basis but also on an inter-basis.[3]

Political objectives and motivation:

The study indicated that the integration of the Single Market remained incomplete, with only certain sectors open to competition. Adopting protectionist tendencies to integrate the market would undermine the original objectives behind establishing the European Community. It highlighted that increased government spending would only yield temporary results, further compounded by existing issues like inflation, external imbalances, and rising unemployment rates. Challenges also arose from conflicts between governments and social partners. Reducing working hours and enabling job-sharing at the national level could lower productivity due to an inability to strike the right balance between the demand for skilled workers and the available labour supply.

Identified challenges and analysis:

Europe’s potential economic growth rate during the time declined from around 4 percent to 2.5 percent annually. Unemployment steadily increased from cycle to cycle and was categorised into cyclical, structural, and technological unemployment. A gap emerged between the rapid pace of technical progress, which often eliminated jobs through improved manufacturing processes and work organisation, and the capacity to identify new individual or collective needs that could provide employment opportunities. The investment ratio had fallen by five percentage points. Europe’s competitive position relative to the USA and Japan worsened in areas like employment, export market share, R&D, innovation, and bringing new products to market. The absence of open and competitive markets, to varying degrees, hampered the optimal utilisation of existing networks and their expansion in the interests of both consumers and operators. Education systems faced major difficulties beyond budgetary constraints, rooted in social issues like family breakdowns and unemployment-induced demotivation. There was a lack of coordination across various levels of research, technological development activities, programs, and strategies in Europe. However, Europe’s most significant weakness was its comparatively limited ability to translate scientific breakthroughs and technological achievements into industrial and commercial successes.

Major recommendations:

The study emphasised that only properly managed interdependence could guarantee a positive outcome for all. Firstly, the body of rules (laws, regulations, standards, certification processes) ensuring the smooth functioning of the market needed to be supplemented in line with the initial targets, such as intellectual property or company law. These rules also required simplification and alleviation. Crucially, their development had to be safeguarded against the risk of inconsistencies between national and Community laws, necessitating fresh cooperation between governments during the legislative drafting stage. Consistency in Community legislation affecting companies, particularly environmental legislation, was also essential. Regulatory and financial obstacles needed to be removed, and private investors should be involved in projects of European interest, applying the provisions of the Treaty and ‘Declaration of European Interest.’ Improving external flexibility meant enabling more unemployed individuals to meet the identified requirements of businesses. The rapid dissemination of new information technologies could certainly accelerate the transfer of certain manufacturing activities to countries with distinctly lower labour costs. Helping European firms adapt to the new globalised and interdependent competitive situation was crucial. Exploiting the competitive advantages associated with the gradual shift towards a knowledge-based economy was also necessary. Promoting sustainable industrial development and reducing the time lag between the pace of change in supply and the corresponding adjustments in demand were essential.

THE MONTI REPORT: A NEW STRATEGY FOR THE SINGLE MARKET (2010)

In 2010, European Commission President Manuel Barroso identified the Single Market as a key strategic objective for Europe. The European Commission tasked the former Prime Minister of Italy Mario Monti to examine the challenges associated with the re-launching of a Single Market and identify the policy solution to build a strategy.[4]

Political objectives and motivation:

The European debt crisis from 2009 to mid-2010s, revealed a tendency among some member states to retreat from the principles of the Single Market and embrace economic nationalism, especially during challenging times. However, the full potential of the Single Market has yet to be realised, and many areas remain fragmented, hindering its ability to drive economic growth and deliver maximum benefits to consumers. The report recognised that the EU’s industrial capacity to innovate and create value in the digital realm is hindered by a number of obstacles: fragmented online markets, inadequate intellectual property legislation, lack of trust and interoperability, insufficient high-speed transmission infrastructure, and a shortage of digital skills. The report also highlighted the costs associated with Europe’s digital deficiencies and underscored the importance of adopting digital technologies to bridge these gaps. Additionally, some member states’ excessive reliance on self-regulating financial markets led to delays and inadequacies in establishing appropriate regulatory and supervisory frameworks, contributing to the fragility of this crucial component of the Single Market.

Identified challenges and analysis:

The declining political and social backing for market integration across Europe is hindering the Single Market progress. The Single Market is viewed with suspicion, fear, and overt hostility. There are two mutually reinforcing trends at play: “integration fatigue,” which erodes the appetite for further European integration and the Single Market, and the more recent “market fatigue,” characterised by dwindling confidence in the role of the market. Due to the decrease in its popularity, there is now declining support for the principles of market integration and the EU itself, driven by a combination of factors that have fuelled scepticism and distrust among the people and the leaders. The erosion of public trust in the benefits of a unified market and the perceived threats it poses to national interests and identities have contributed to this trend. There is an uneven policy attention given to developing the various components necessary for an effective and sustainable Single Market. Difficulties faced by the Single Market can be attributed to the unfinished tasks on two other fronts: expanding the Single Market to new sectors to keep pace with a rapidly changing economy, and ensuring that the Single Market is a space of freedom and opportunity that serves the interests of all stakeholders, including citizens, consumers, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Failure to adequately address these multiple fronts has contributed to the fragmentation and inefficiencies that currently undermine the full potential of the Single Market.

Major recommendations:

Reforming the EU budget both in terms of revenue and expenditure is considered crucial, to address the EU’s priorities and tackle contemporary challenges, whether economic, security-related, geopolitical, social, or cultural. The EU budget should focus on areas that bring the highest European added value, where European action is not only relevant but indispensable. The EU budget should find synergies between EU and national funding. The need for improving the functioning of the Single Market and fiscal coordination, through measures like a reformed VAT-own resource, a corporate income tax-based own resource, a financial transaction tax, or other financial activities’ taxes needs to be realised. An alternative EU framework through a 28th regime providing for a single legal framework needs to be considered to provide options for businesses and citizens. To better reflect the costs and benefits of EU membership, the current indicators, mostly focused on net balances, should be supplemented with additional indicators that capture the added value of EU policies and participation in the largest Single Market, providing a more comprehensive picture. Better information channels should be established to align shared objectives between national/European procedures. There is a need for a comprehensive and balanced approach to strengthening the Single Market, addressing both the structural and sectoral aspects of integration. While the unity and universality of revenue should not be jeopardised, a certain degree of differentiation should be allowed when some Member States are willing and able to move forward, particularly for the further development of the euro area or for policies under enhanced cooperation. Further, private enforcement is important to contribute towards ensuring the effectiveness of the Single Market.

THE LISBON STRATEGY (LISBON EUROPEAN COUNCIL 2000 PRESIDENCY CONCLUSIONS)

The European Council decided to set a strategic goal for the Union to strengthen employment, and implement economic reforms and social cohesion as part of a knowledge-based economy. This was done as means towards achieving sustained economic growth and greater social cohesion. [5]

Political objectives and motivation:

The underlying objective was that to complete the internal markets in certain sectors and to improve performance by aligning the market goals with the interests of the businesses and the consumers, there needs to be a framework for achieving the full benefits of market liberalisation. This required a framework which would realise the benefits of market liberalisation, prioritising fair competition and state aid rules and alignment with the Treaty provisions relating to services of general economic interest.

Identified challenges and analysis:

Key challenges included low employment rates due to insufficient labour force participation by women and older workers, regional unemployment imbalances, and an underdeveloped service sector. There was a need to fill skills gaps and improve the overall economic situation. The analysis pointed to the EU’s shift resulting from globalisation and the new knowledge-driven economy, with the aim of responding to economic backwardness compared to main competitors by increasing innovation, research performance, and setting a strategic goal to build knowledge infrastructures, enhance economic reform, and modernise social welfare and education systems.

Major recommendations:

The requirement to transition to a knowledge-based economy and society through better policies for the information society, R&D, structural reforms for competitiveness and innovation, and completing the internal market was emphasised. Other recommendations included modernising the European social model by investing in people and combating exclusion, sustaining economic outlook and growth prospects via an appropriate macro-economic policy mix, introducing more competition in local networks to reduce internet costs by 2000, creating an “information society for all”, facilitating a high-speed pan-European network for scientific communication by 2001, establishing a European Area of Research and Innovation by 2002 to attract talent and enable inexpensive EU-wide patent protection, fostering an environment for innovative businesses especially SMEs, using macro-economic policies to drive the transition to a knowledge economy with an enhanced structural policy role, and applying a new open method of coordination to spread best practices and achieve convergence on main EU goals.

THE EUROPE2020 STRATEGY (COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION)

The 10-year strategy aimed at making the European Market a “smart, sustainable, inclusive” with greater coordination of national and European policy and a renewed focus on research and development.[6]

Political objectives and motivation:

The political motivations stemmed from the millions left unemployed and the debt burdens from the preceding two years, which strained social cohesion. There was recognition that maintaining “business as usual” would relegate Europe to gradual economic decline on the global stage. The crisis served as a wake-up call for change. The objectives centred on: 1) Smart growth – Developing a knowledge and innovation-based economy, 2) Sustainable growth – Promoting a greener, more resource-efficient and competitive economy, 3) Inclusive growth – Fostering a high-employment economy delivering social and territorial cohesion.

Identified challenges and analysis:

Europe’s structurally lower growth rates compared to major partners, largely due to a widening productivity gap over the preceding decade stemming from differences in business structures, lower R&D and innovation investment, insufficient ICT utilisation, societal resistance to innovation, market access barriers, and a less dynamic business environment has resulted in EU fragmentation. Additionally, Europe’s employment rates at 69 per cent for ages 20-64 lagged behind other regions with gender and age participation gaps persisting as only 63 per cent of women and 46 per cent of older workers (55-64) were employed, while Europeans worked 10 percent fewer hours compared to US and Japanese counterparts. The demographic challenges of an ageing population and shrinking workforce from 2013/2014 onwards threatened additional strains on welfare systems.

Major recommendations:

The EU should aim to establish several initiatives: An “Innovation Union” to improve frameworks for research and innovation, provide financing, and facilitate the commercialisation of products; “Youth on the Move” to enhance performance in education systems and ease the entry of youth into the labour market; A “Digital Agenda” to accelerate the rollout of high-speed internet and reap the benefits of digital markets; A “Resource Efficient Europe” initiative to decouple economic growth from resource use, shift towards low-carbon economies, increase the use of renewable energy sources, modernise transport systems, and boost energy efficiency; An updated industrial policy to improve the business environment, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and foster a strong, sustainable industrial base; A “New Skills and Jobs Agenda” to modernise labour markets, empower people through skills development initiatives, increase labour force participation, and better match labour supply with demand; And a “European Platform Against Poverty” to ensure social and territorial cohesion so that the benefits of growth were widely shared and the impoverished could actively participate in society.

[1] Cecchini, P., M. Catinat and A. Jacquemin (1988), The European challenge –1992-The benefits of a Single Market. Wilwood House, Adelshot.

[2] The report also commissioned a survey involving 11,000 business people. The results indicated that “administrative and customs barriers, coupled with divergent national standards and regulations, are top of the aggravation list,” for fragmenting the Single Market. Moreover, the most obstructive barrier to cross-border trade for businesses were administrative formalities and border controls. This has been due to differences in VAT and excise rates, enforcement of bilateral trade quotas and other quantity restrictions with non-EC countries for certain goods, to name a few.

[3] European Commission. (1994) Growth, Competitiveness, Employment: The Challenges and Ways Forward into the 21st Century White Paper. Available at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4e6ecfb6-471e-4108-9c7d-90cb1c3096af/language-en

[4] Report to the President of the European Commission. A New Strategy for the Single Market by Mario Monti. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/empl/dv/empl_monti_report_/empl_monti_report_en.pdf

[5] European Parliament. (2000) Lisbon European Council 23 and 24 March 2000 Presidency Conclusions. Hereinafter referred as the Lisbon Agenda. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_en.htm

[6] European Commission. (2010) Communication from the Commission European 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth