Addressing the Regulatory Divergences in the Medical Devices Sector

Published By: Hosuk Lee-Makiyama

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements Healthcare North-America Services

Summary

Medical devices are not just simple commodities. They are the result of decades of research and development and scientific advancement, and an increasingly important sector for future economic development. Not simply because of the imminent demographic changes, the medical technology industry is one of the innovative and research intensive sectors that creates high- skilled jobs within its own sector and those sectors that use them.

Yet hip implants or cardiovascular equipment cannot be sold like most commercial goods. The marketing conditions for medical devices are to a great extent determined by public health pol- icies and regulations. The inherent policy dilemma is to establish a balance between promoting innovation and access to new devices while ensuring product safety.

Due to different political histories and regulatory traditions, countries have different regulatory regimes for the medical devices industry. As a result, duplicate testing of products, including du- plication of clinical trials, as well as non-value adding administrative requirements are common. Such procedures may delay access to certain devices, lead to higher prices for patients and are detrimental to the sustainability of healthcare systems. In practice, the range of available medical technologies differs between the EU and the US.

Previous attempts to address regulatory divergences in the field of medical devices have basically been fruitless. International regulatory coordination has progressed slowly and existing interna- tional agreements have very modest scopes. Products still have to go through duplicate clinical tests even though they have already been authorised in other countries.

This is where the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) comes into the picture. Aiming to promote economic growth and jobs, one of the original key objectives of TTIP is to foster ‘enhanced compatibility of regulations and standards’.1

There is no doubt that the medical devices sector should be a key sector within TTIP. To begin, Europe, the US and Japan are highly dominant in both production and usage for medical devic- es, and economic benefits could be derived from further integrating the markets. Although tariffs are already relatively low, even if further progress needs to be made on some categories of devices, the next step must be to address the regulatory discrepancies. Meanwhile, it seems unfeasible to expect regulatory harmonisation to take place elsewhere – be it at multilateral level amongst the 159 members in the World Trade Organisation (WTO), or other forums. Considering the importance and complexity involved, any meaningful approach to regulatory issues in the sector are only likely to take place in bilateral agreements with like-minded economies of similar im- portance and level of development.

Additionally, a substantial amount of engagement from policy-makers, industry and regulators will be needed to achieve any results, which means that any deal on medical devices would have to be part of a bigger grand bargain with other sectors. Previous experiences in regulator-to-reg- ulator dialogue show that it is unlikely that a standalone agreement would mobilise the necessary political capital to achieve any meaningful progress in the sector. Meanwhile comprehensive economic integration is already taking place elsewhere, with or without Europe – most notably through Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Against this backdrop, this policy brief analyses possible ways of addressing regulations on med- ical devices in TTIP. First, the paper analyses the current market structure and past attempts of integrating the markets. Second, it explores possible ways of dealing with medical devices in TTIP, taking the defining features of both regulatory systems into consideration.

A STRONG CASE FOR ADDRESSING MEDICAL DEVICES IN TTIP

The economic rationale behind further market integration in the medical devices sector is underpinned by the dominance of the US and Europe on the world market and their shared export interests. The United States, Europe and Japan together represent almost 90 percent of global production and consumption of medical devices. Out of the total worldwide sales, amounting to approximately $300 billion, the US accounted for 40%, the EU for 30% and Japan just above 10%.[1] In size, the European medical technology market is estimated at $100 billion.[2] This dominance of the US and European producers in the global market strengthens the case for further market integration.

The medical devices industries in the EU and the US are organised slightly differently. Broadly speaking, the US industry consists of larger corporations, such as for example Johnson & Johnson, GE Healthcare, Medtronic, Baxter, Cardinal Health, Tyco Healthcare, Boston Scientific, Stryker, and others. These multinationals are very competitive in the segment and trade in highly innovative products, such as cardiovascular and orthopaedic devices. They invest large amounts to stay in the forefront of developing new advanced technologies, and US firms reinvest above 10 percent of their sales into R&D, while their European competitors spend merely 6 percent of their sales on R&D.

Also, thanks of the competitive business environment of their home market, US firms tend to have better access to capital and funding. But spending resources on R&D is not a self-fulfilling goal. The rate of return on the invested capital is essential in order to maintain a competitive edge. But even in this regard, the US medical devices industry outperforms the others. US labour productivity in medical devices is extremely high, over 70% higher than the EU firms in the sector.[3] In effect, any capital invested the US medical devices sector generate significantly higher output compared to Europe.

This is partly due to the fact that the medical technology industry in Europe is fragmented, with a large number of small- and medium sized companies. In fact, 95% of the almost 25,000 European-based medical technology companies are SMEs with less than 250 employees.[4] This does not only affect their ability to attract capital, but also affects the way in which they operate and trade: Few European-based companies have any significant market presence outside their home market, with the exception of multinationals like Siemens, Philips and B. Braun. SMEs in general have lower capacity to surmount non-tariff barriers (NTBs) and adapt to different regulatory systems in potential export markets.

Also, SMEs are less able to build and capitalise on global supply chains in their production. With less ability to diversify their risks, EU firms are more vulnerable to e.g. restrictive reimbursement policies that have become permanent fixtures of through austerity programs of recent years.[5]

In other words, the EU would expect high benefits from regulatory harmonisation.

In geographic terms, the medical devices industry is concentrated in certain European countries, with Germany, France, United Kingdom and Italy dominating. The relative importance of the medical devices per capita is also significant in Ireland, Switzerland and Sweden. A key additional factor in favour of addressing medical devices in TTIP is the high concentration of high-skilled jobs that the industry supports in Europe, 575,000 (including Norway and Switzerland). While Germany has the highest absolute number of employees in the med-tech sector in the EU, Ireland has the highest per capita employment. The US medical technology sector employs a similar number, 520,000 people.

In addition, many medical devices firms in the EU compete in the low-end of the market, with established products. These are volume-driven markets with slim profit margins, where competition from third markets are expected. It is generally easier for competitors to ‘build-around’ a patented product in the medical equipment sector in comparison with the pharmaceutical sector.[6]

Given the barriers to entry are higher for sophisticated products due to high start-up costs, EU firms face difficulties in climbing higher up in the value chain.

Strong demand for medical devices

The demand for medical devices is high and likely to increase in view of future demographic changes. In 2010, OECD-countries spent 9.5% of their GDP on health care on an average. This represents a significant increase from 4% in the year 2000. The expenditures have increased in recent years due to demographic factors, as well as the development of technically sophisticated equipment, which is more expensive. However, following the economic crisis, expenditures have slowed down in relative terms or even decreased.[7]

Medical devices accounted for 6.7% of total health care expenditures in the European Union in 2012, with the corresponding figure for the US at 4%, bearing in mind that the US spends more than any other country on health care – approximately 14% of GDP.[8]

The demand side of the market is heavily affected by political decisions. This is due to the way in which the health care systems are being administered, particularly in Europe, where health care is a universal service provided and subsidised by the public systems. Health care authorities often have monopsony power, i.e. they are often the sole or the main purchasers of medical equipment. Consequently, reimbursement policies implemented by governments or private insurers have a decisive impact on the industry. Furthermore, authorities also control market entry though testing and premarketing authorisation procedures, resulting in unparalleled market control.

Trade in medical devices

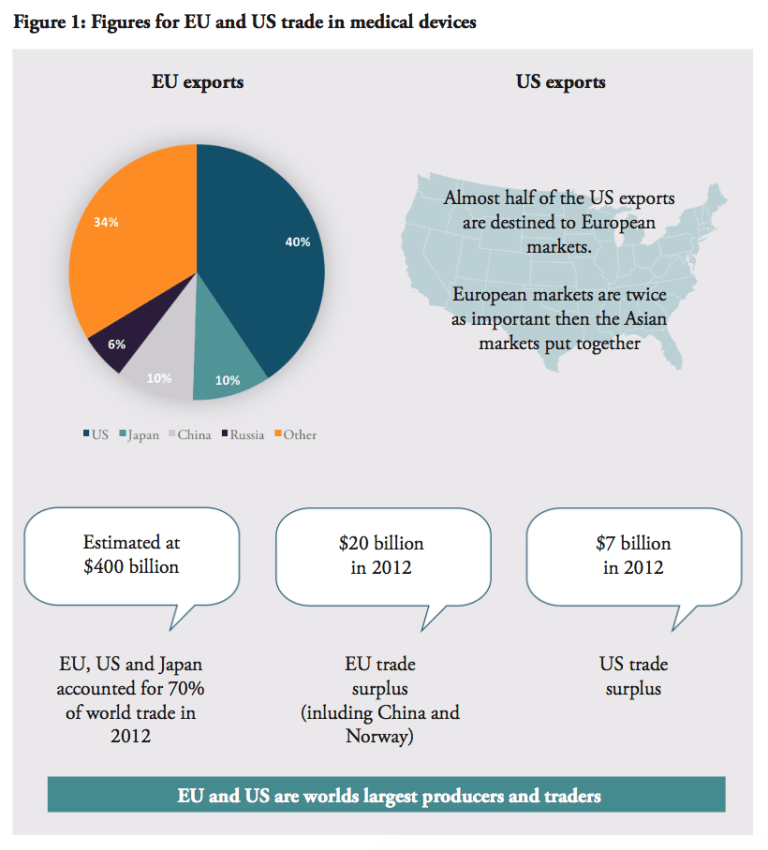

Europe and the US are not only the world’s two largest producers, but also the largest traders. Together with Japan, they accounted for around 70% of world trade in medical technologies in 2012, estimated to almost $400 billion in total.[9] Europe (including Switzerland and Norway) enjoy positive trade balances in the sector; $20 billion in 2012, more than a twofold increase since 2006, while the US trade surplus is just $7 billion. The US market is Europe’s largest export destination, receiving 41% of EU exports. No other market comes near the US in this regard, compared to EU exports to Japan (10%), China (9.5%), Russia (5.5%).

This importance is reciprocated – the US accounts for 65% of EU imports. Almost half of US exports in the sector is destinated to European markets, which are twice as important than the Asian markets put together.[10] Other important exporters to Europe are China (10.5%) and Japan (7%). Amongst the EU Member States, Germany is by far the major trader amongst the European countries, followed by the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Ireland and France.[11

Against this background, it is clear that the EU and the US have a shared interest in promoting exports of medical devices to each other’s markets as well as to third country markets and emerging economies, in particular China with its rising healthcare system: the sales of US medical devices to China increased by over 20% between 2009 and 2010.

As stated in the onset, tariffs are arguably not the main trade barrier in the sector, compared to the regulatory divergences. Harmonisation between the EU and the US would promote sales and secure access to medical technologies, which would also incentivise third markets to adopt similar regulations and pave the way for lower costs to market and market access on a global scale.

Conversely, Europe’s position in the medical devices are likely to be lost if an ambitious outcome cannot be achieved. Considering the European industry organisation and revenue models in the medical technologies are, by large, dependent on economies of scale, the EU depends on TTIP more than ever and anyone else. It is also unlikely that other countries would engage Europe in liberalising the medical devices sector. For example, the EU and Japan recently launched negotiations on a FTA where non-tariff measures are the main hurdles to accessing Japan.

[1] USITC (2007)

[2] The European Medical Technology Industry in Figures. MedTech Europe, 2014

[3] USITC (2007)

[4] Eucomed (2013)

[5] USITC (2007)

[6] USITC (2007)

[7] Eucomed (2013)

[8] USITC (2007)

[9] USITC (2007)

[10] World Trade Daily (2011-07-21)

[11] MedTech Europe (2014)

PAST ATTEMPTS AT TRANSATLANTIC INTEGRATION

With the case for transatlantic regulatory cooperation being strong, the idea to integrate the medical devices market is not an untested idea. The most advanced form of market integration is regulatory harmonisation that applies to both existing and future regulations. This complete form of cooperation is difficult both at a technical level and also at a political level. It requires that regulators relinquish a certain amount of decision-making power.

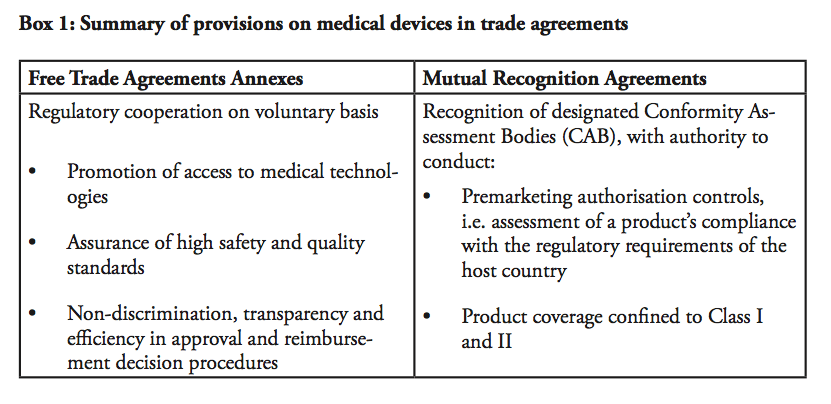

Given the difficulties of regulatory harmonisation, efforts of regulatory cooperation have instead taken two other forms. First, provisions on medical devices and pharmaceutical products that goes beyond mere tariff eliminations are included in free trade agreements (FTA), for instance in the EU-Korea FTA, the EU-Singapore FTA and the US-Korea FTA (KORUS). In a nutshell, these provisions provide acceptance of each other’s standards, some acceptance of conformity assessment results on good practices and common definitions. In some cases, they assure that the signatories will be given non-discriminatory, national treatment on public reimbursement.

An annex on medical devices, pharmaceutical products and cosmetic products has also been proposed to the Trans-Pacific Partnership by the US. A second way to address regulations is through mutual recognition agreements (MRAs). There are several MRAs in place, notably the EU-US agreement on mutual recognition, the EU-Australia MRA on conformity assessment as well as the EU-Japan MRA on good manufacturing practice for medical products. However, as this section will demonstrate, these previous efforts have failed to deliver significant efficiency gains due to their modest scopes and the complexity of the regulatory systems.

Medical devices in Free Trade Agreements

Let us first look at provisions on medical devices in FTA annexes. As this section will show, no FTA concluded up to date has fostered any significant market integration. In effect, there is nothing beyond regulatory cooperation and transparency with respect to the administrative procedures. These commitments are, however, not subject to legal review.

Both the EU and the United States have high standard FTAs with Korea. The agreements address not only tariffs but also behind-the-border barriers such as regulatory issues. The annexes on medical devices in the EU-Korea and the KORUS are very similar – they are designed to address same barriers, and the EU sought to maintain level playing field with KORUS that was already signed. In fact, the wordings of two texts are to a large extent identical. There are provisions recognising the parties’ commitments to promote patients’ access to medical devices and to assure high standards of safety, efficacy and quality. Moreover, the FTAs state that both parties shall ensure that the procedures regarding reimbursement decisions, listing, pricing and regulations are fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory. With respect to transparency of the administrative procedures, the parties shall, for example, “permit a manufacturer of the […] medical device, after a decision on a reimbursement amount is made, to apply for an increased amount of reimbursement”. Furthermore, there are provisions obliging health authorities to publish proposed regulations before these are adopted and allow stakeholders to submit comments. Each party “shall ensure that its laws, regulations, procedures, administrative rulings and implementing guidelines of general application […] are promptly published or otherwise made available”. Both FTAs also establish working groups with the objective of facilitating regulatory cooperation.

There are, however, a couple of important differences between the EU-Korea and the KORUS texts. Unlike the EU-Korea text, the KORUS annex does not refer to international organisations such as the WHO, OECD, the International Conference on Harmonization and the Global Harmonization Task Force or the new International Medical Device Regulatory Forum. Nonetheless, there are certain nuances with respect to the obligations of health authorities to inform manufacturers during the course of the administrative procedure. In this respect, the EU-Korea agreement is more detailed, stating for example that “if the information submitted by the applicant is deemed inadequate or insufficient and the procedure is suspended as a result, the Party’s competent authorities shall notify the applicant of what detailed additional information is required”. Also, unlike the KORUS, the EU-Korea annex states that “[…] in case of a negative decision on listing prices and/or reimbursement, or should the decision-making body decide not to permit in whole or in part the price increase requested, the decision-making body shall provide a statement of reasons that is sufficiently detailed to understand the basis of the decision, including the criteria applied and, if appropriate, any expert opinions or recommendations on which the decision is based”.

KORUS, on the other hand, includes a paragraph on companies’ rights to disseminate information, which is not found in the EU-Korea. It is stated in KORUS that “each Party shall permit a pharmaceutical manufacturer to disseminate through the manufacturer’s official Internet site registered in the Party’s territory and through medical journal Internet sites registered in the Party’s territory, that include direct links to the manufacturer’s official Internet site, truthful and not misleading information regarding the manufacturer’s pharmaceutical product […]”.

In comparison to the agreements with Korea, the EU-Singapore FTA annex on medical devices is shorter and less detailed. Still, akin to the EU-KOR FTA, it contains provisions on transparency, non-discrimination and stakeholder dialogue.

The annex on “transparency and procedural fairness for pharmaceutical products and medical devices” in TPP follows broadly the language of the KORUS FTA, but the annex appears less detailed. The text also includes a provision for the non-application of dispute settlement mechanism.

In sum, none of these FTA annexes contain any legal provisions that could prompt market integration. There is no formal recognition of test results or marketing authorisation decisions. The provisions are confined to encourage the parties to ensure transparency and non-discrimination within the decision-making and testing procedures. Accordingly, the FTA annexes remain statements of the parties’ good intentions to pursue regulatory cooperation.

Mutual Recognition Agreements on medical devices

Mutual Recognition Agreements on medical devices

Let us turn to mutual recognition agreements (MRAs), which were the main regulatory pathway to market integration prior to bilateral FTAs. MRAs in the medical device sector have had limited scopes – in fact, looking at existing MRAs in the sector, e.g. the EU-US MRA, the EU-Australia or the EU-Japan MRAs, none of them are actual real mutual recognition agreements in the meaning they are mutually recognising each others products legitimately circulated on the market. In other words, none of these agreements state that one country accepts and recognises products that are authorised and marketed according to the regulations in the other country. In the EU-US MRA, for instance, it is explicitly stated that the “agreement shall not be construed to entail mutual acceptance of standards or technical regulation of the Parties and […] shall not entail the mutual recognition of the equivalence of standards or technical regulations”.

Instead, the MRAs on medical devices state that the parties will accept each other’s products provided that they have been approved by appointed Conformity Assessment Bodies (CABs). In practice, this means that a European-based medical device manufacturer will first have to get marketing approval from a European Notifying Body (NB) in order to sell its product in Europe. In order to sell the exact same product in the US, the manufacturer can submit an application for premarket approval to a CAB within the EU, recognised by the US. The CAB is authorised to make a preliminary report regarding the product’s conformity with US regulations. The file is thereafter forwarded to the US health authority that takes the final decision. In sum, the only impact of the MRA is that the European-based manufacturer can submit the application for market authorisation to an agency based in Europe, instead of applying to the responsible authority in the US. The EU-US MRA does not remove the need for duplicate testing, and products still need to be assessed against both the American and European regulatory requirements in order to be sold on both markets.

Moreover, the product coverage of the EU-US agreement is very limited, including only products in Class I and Class II, excluding Class III. Also, the agreement includes a number of safeguards, namely that it does not limit the health authorities’ power to implement measures considered appropriate in order to guarantee safety etc. In addition, both the EU and the US retain the right to withdraw their respective obligations under the agreement in the event that an industry suffers from a loss of market access.

Similarly to the EU-US MRA, the EU-Australia MRA from 1999 states that “both the European Union and Australia recognise and accept the technical competence of each other’s conformity assessment bodies (CABs) to certify products for compliance with the regulatory requirements of the other Party”. Although it is claimed that the agreement is “largely eliminating the need for duplicative testing or re-certification when the goods are traded”[1], that is hardly the case, as demonstrated above in the example of the EU-US case.

Furthermore, the EC-Japan MRA on good manufacturing practice for medicinal products from 2001 is designed along the same lines. According to the agreement; “each Party shall accept […] the results of conformity assessment procedures required by the applicable laws, regulations and administrative provisions of that party specified in the relevant Sectoral Annex, including certificates and marks of conformity, that are conducted by the registered conformity assessment bodies of the other party.”[2] In practice, products still go through duplicate testing procedures. Besides, the EU-Japan agreement only covers a limited number of products in the categories of chemical pharmaceuticals, homeopathic medicinal products and vitamins, minerals and herbal medicines.[3]

To the defence of MRAs, they have some merit – which is largely political and symbolical – rather than conducive to market integration. Their limited scope often arises from the positive listing, meaning that only products that are explicitly listed are covered by the agreement. This reduces the usefulness of these agreements significantly.

What is mutual recognition?

In fact, it seems fair to say that these MRAs are not actual instruments for mutual recognition, in the original sense of the word. In the context of trade agreements, the WTO does not pin down any legal definition of the concept. The WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade encourages countries to recognise conformity assessment decision by other countries’, stating that (art. 6.3) “Members are encouraged […] to be willing to enter into negotiations for the conclusion of agreement for the mutual recognition of results of each other’s conformity assessment procedures”.

In addition, mutual recognition of professional services was part of the so called Built-in Agenda issues, set-up at the Singapore WTO Ministerial Conference in 1996. Following up on the Uruguay Round and the negotiations on professional services, WTO members then agreed on guidelines for mutual recognition negotiations on accountancy services.[4] However, these discussions have basically been put on the back burner ever since they saw the day as other issues came to dominate the WTO’s agenda.

Within the EU, mutual recognition has come to be defined by the European Court of Justice’s ruling in the Cassis de Dijon case from 1979, establishing that “any product lawfully produced and marketed in one Member State must, in principle, be admitted to the market of any other Member State”.[5] This principle is today underpinning the free circulation of goods in the internal market. It has been upheld and reinforced by subsequent rulings by the ECJ, which is the supranational guardian of the EU treaties.

Cassis, or blackcurrants, are far less popular in the US, perhaps preventing this savoury berry from establishing a legal precedent. Nonetheless, the US Constitution, Article 1 Section 10, prohibits states from introducing duties on imports or exports between each other. Yet there is no constitutional obligation for the states to recognise each other’s standards for products or services.

Despite the absence of a Cassis de California case, federal standards do exist in certain sectors. In the field of medicine, for instance, federal rules pre-empt state regulations. Also, according to the Commerce Clause in the Constitution, “The Congress shall have Power To […] regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. This basically means that Congress can adopt regulations at federal level that supersede state regulations with respect to activities that have an effect on trade.

In addition, there are codes of mutual recognition in the US in certain sectors or professions. The establishment of such codes usually result from initiatives taken by professional interest groups, for instance in the accounting, engineering and architecture sectors. At the end of the day, however, the states decide whether or not to adhere to such mutual recognition codes.

In sum, there is no universally accepted understanding of the concept of mutual recognition. It can refer to the recognition of another country’s standards and regulations, or more simply to the recognition of the conformity assessment procedures carried out by agencies in another country.

Europe and the United States have different experiences when it comes to recognising products and services from other countries or states. The individual US states arguably have more power in introducing requirements that products and services have to comply with state regulations. In the EU, on the other hand, mutual recognition applies in principle to all products. Without reference to the conformity assessment procedures, all EU Member States are required to accept products that are lawfully sold and marketed in another Member States. All in all, it cannot be assumed that American and European negotiators have the same reference points when they sit down to discuss regulatory cooperation.

This needs to be taken into consideration in the TTIP negotiations. In particular, TTIP must include a concrete prospect of market integration if it is to achieve meaningful results. A half-hearted exercise similar to existing FTAs or MRAs will not suffice if TTIP is to have an impact on economic efficiency. It is also clear that regulatory cooperation with respect to medical devices has to be part of a grand bargain, like TTIP. Without political pressure, there is a significant risk that a dialogue between regulators will lead to a stalemate as there is no incentive to compromise. On this note, the regulatory dialogue in the Transatlantic Economic Council on rules regarding chlorine-washed chicken should discourage most policy-makers from sector-specific standalone agreements.

[1] Australian Government, Department of Health (2012-11-30) ‘Medical device amendments to the EU-Australia MRA on conformity assessment to come into effect 1 January 2013’

[2] OJEC (2001)

[3] EMEA (2004)

[4] WTO Council for Trade in Services, Guidelines for Mutual Recognition Agreements or Arrangements in the Accountancy Sector, S/L/38, 28 May 1997

[5] Communication from the Commission concerning the consequences of the judgement given by the Court of Justice on 20 February 1979 in case 120/78 , available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CLEX:31980Y1003%2801%29:en:HTML

EU/US REGULATORY DIVERGENCES*

TTIP was launched with the highest possible level of ambition on regulatory harmonisation, matched by an unprecedented mobilisation of political capital, at least in European capitals. Yet, it ran into severe difficulties very early on.[1]

The position paper by the European Commission on medical devices in TTIP reveals a cautious approach,[2] focusing on procedural streamlining, such as ‘similar’ electronic forms in both systems, and closer cooperation between the regulators on practical level. Examples of the latter include making the Unique Device Identification (UDI) databases compatible for traceability, co-operating on recalls and, in various ways, enhancing patient safety. The position paper explicitly lists harmonisation of approval process as a sensitive issue, possibly explained by the current revision of the EU Medical Devices Regulations. In sum, at least the EU is veering towards maintaining legislative sovereignty rather than freeing up new trade.

Given the narrow scope of the EU-US MRA, a number of practical challenges remain before a product that is approved for marketing in Europe can be sold in the US, and vice versa. Mutual trust between the regulatory agencies is key to the negotiation process, but far from all. Both sides would have to accept each other’s way of regulating their markets if integration is to advance beyond the MRA and deliver better consumer and patient value for money. This will admittedly be challenging. As both the EU nor the US are used to negotiate with a counterpart of equal size to themselves, neither of them are being “demandeurs” or deviating from their own template trade agreements based on their own domestic laws. Yet, both the systems of the EU and U.S are underpinned by the paramount objective to assure product and patient safety – that tend to produce similar results. In this respect, there is no need to reinvent the wheel by establishing a third, common system between the EU and the US in order to integrate them.

Let us first look at some of the systemic divergences before examining the possible methods of overcoming them in the following section.

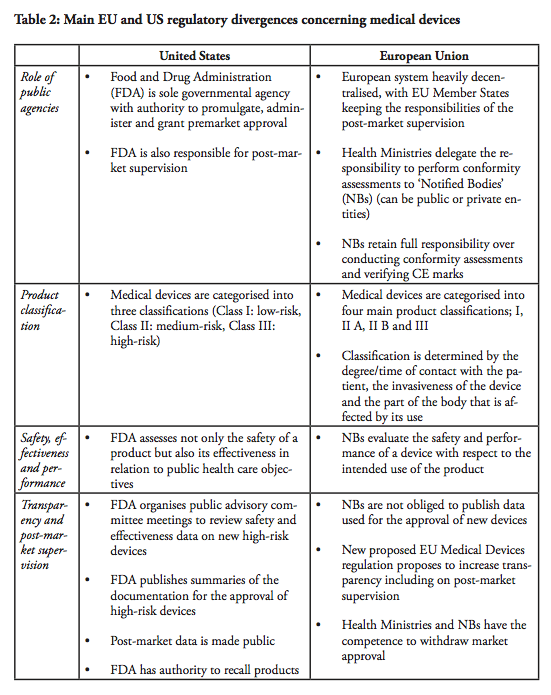

Role of public agencies

Role of public agencies

The first major divergence between the EU and US systems concern the role of the regulator. In the end, regulators are also the lead-negotiators in the trade negotiations – and there is a fundamental difference with respect to how the public agencies and the markets are organised. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the sole governmental agency with authority to promulgate, administer and grant premarket approval in the United States. The FDA is also responsible for post-market supervision. In the European Union, the health ministries in the Member states are the ‘competent authorities’ with overall responsibility for public health care policies. However, the ministries delegate the responsibility to perform conformity assessments to designated independent third-parties, so called ‘Notified Bodies’, which can be public or private entities. There are currently around 75 Notified Bodies in the EU. The NBs retain the full responsibility over conducting conformity assessments and verifying that the Conformité Européenne (CE) marks can be affixed by the manufacturer. Although there are independent agencies in the US that are accredited by FDA to perform third party review of premarket submissions for certain low to moderate risk devices, these agencies may only conduct primary reviews of Class I devices that are not exempt from premarket notification, as well as certain Class II devices for which device-specific guidance and/or FDA recognised standards are in place. Class III devices and other Class II devices that require clinical data are not eligible for third party review (see below). In all cases, the recommendations resulting from third-party reviews have to be sent to the FDA for final approval. In short, whereas the European system is heavily decentralised, with EU Member States keeping the responsibilities of the post-market supervision, one agency, the FDA maintains the sole authority over all market supervision in the US.

However, there is no reason why these administrative differences should impede recognition of the results of the assessment carried out. On a more general level, TTIP is too important for the medical devices sector to block it. Besides, the central agency in the US as well the independent NBs in Europe have all been appointed with the purpose of assessing requests for market authorisation and ensuring a high level of safety for patients and citizens. But while the Notified Bodies in the EU are used to operating in a decentralised system, it would mean a huge change within the US system, to shift from its current centralised regulatory framework and recognise decisions taken by other agencies. Amid budgetary restraints everywhere, however, a deal with Europe would allow the FDA to focus its resources elsewhere. Medical devices that are already authorised and marketed in the EU are arguably not those with the most dangerous health risks.

Moreover, a commonly expressed concern regarding the European system is the alleged differences between the Notified Bodies, as well as their commercial character. The NBs, which are designated and monitored by the national competent authority, are usually financed by a combination of public funding and user fees, although it varies depending on the Member state. As a result, some NBs operate on more or less the same basis as commercial companies, although some of them are public entities. Medical companies can in theory ‘shop-around’ among NBs and submit their applications to whichever NB they prefer. Arguably, the best way for NBs to attract clients, i.e. medical companies that want to have their products certified, would be to establish a reputation of efficient service with respect to the issuance of CE marks. In contrast, this type of direct market competition does not exist in the US, although the FDA is funded to approximately 65% by fiscal means whereas the remaining 35% is derived from user fees.[3] In all fairness, however, public funding is never a guarantee of objectivity or impartiality, not in any system. The quality of the system rather depends on a number of control- and surveillance mechanisms. These systems have been recently strengthened in the EU by the regulation on designation and supervision of NBs.[4]

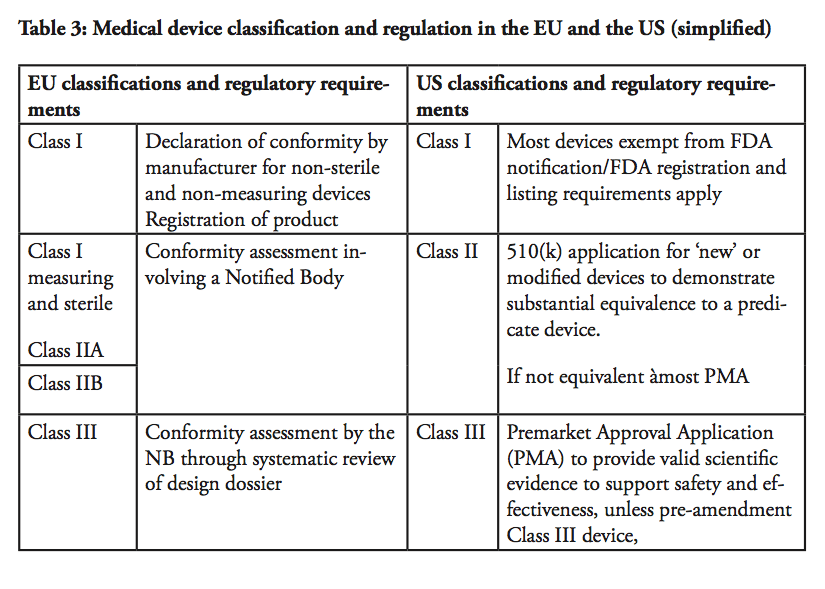

Product classifications and testing requirements

There have been efforts among countries to establish common international product classifications, notably in the International Medical Device Regulators Forum and its predecessor, the Global Harmonization Task Force. The classifications in the EU and the US are guided by the international guidelines but remain different. This being said, they are not incompatible.

In view of regulatory cooperation in TTIP, different classifications are not necessarily an issue per se. The problem is rather that different categories of products are subject to different requirements, among others, the need to perform clinical trials.

In the US, medical devices are categorised into three classifications. Class I devices are typically low-risk devices where ‘general controls’ alone are sufficient to provide reasonable assurance of the safety and effectiveness of the device. This means that Class I products in most cases can be placed on the market without prior FDA notification, provided that the general controls, such as establishment registration and listing, have been satisfied. Around 47% of all medical products belong to Class I – whereas approximately 74% or 572 of these Class I devices are exempt from pre-market notification process.

Class II devices are medium-risk devices such as x-ray apparatus and many orthopaedic implantable devices that are subject to both general and special controls, and require a Premarket Notification (so called a 510(k) submission) to the FDA.[5] As part of the 510(k) process, the manufacturer has to demonstrate to the FDA that a new product is ‘substantially equivalent’ to a ‘predicate’, i.e. a legally marketed device cleared by the FDA or a pre-amendment device In practice, around 43% of all medical devices are categorised in Class II. Approximately 10% of these devices require clinical data to support their substantial equivalence to a predicate device.

Class III products are defined by the FDA as devices that ‘support or sustain human life or are of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health or present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury’. Life-supporting high-risk devices such as implantable defibrillators and pacemakers are examples of Class III products. Such devices are subject to Premarket Approval (PMA), which requires the manufacturers to provide valid scientific evidence, often by conducting clinical trials, in order to establish that the products are safe and effective. Class III devices also have more stringent post-market approval requirements compared to Class I and Class II devices, including annual reporting and, in some cases, post-market clinical trials.

In comparison, in the EU, there are four main product classifications; I, II A, II B and III. The classification of a product is determined by the degree/time of contact with the patient, the invasiveness of the device and the part of the body that is affected by its use.

Class I devices are considered to involve a low risk for users. For such products, the Manufacturer shall prepare a technical file demonstrating compliance with the applicable medical device directive, and issue a ‘declaration of conformity’, in order to affix a CE mark. The manufacturer takes the responsibility to certify that the product complies with all applicable EU legislations. Once a product has obtained a CE mark; it can be distributed within the European Union as well as within EFTA countries and in Turkey. As there is no rule without exceptions, for Class I devices that have a measuring function and those which are sterile, a Notified Body needs to be involved in the process.

Medium risk products, such as hearing aids, are classified in Class II A as they are considered invasive to the human body. Class II B products also involve a medium risk-level but are invasive or partially or totally implantable into the body, including for example a screw to consolidate a bone fracture. Class II B products must pass design controls on a random basis and systematic manufacturing controls.

High-risk Class III devices and active implantable devices, e.g. active implantable medical devices such as cardiac pacemakers, are subject to a design dossier review by the Notified Body which can take up to 10 months before approval in the form of a CE certificate is granted. This approval includes clinical evidence demonstration through published clinical data and new clinical trials, design dossier reviews and assessment of the quality management systems. Only certain Notified Bodies are accredited to approve Class III devices.

For all class of products except Class I, the Quality Management System and technical file or design dossier are assessed and audited by the Notified Bodies, in yearly follow up audits and re-certification audits. Only upon successful completion of the audit the Notified Body will issue a CE certificate. The certificate granted by a Notified Body in the EU has, in any case, a limited validity of five years maximum, which means that the product has to go through a complete re-evaluation every five years, including all the new evidence and data gathered since the product is marketed. This frequency of audits, as well as the need for a full recertification of products every five years at most are unique to the EU system and do represent a significant burden for manufacturers.

In sum, there are in essence three main product classification categories in both systems with some differences, as there are a significant higher number of devices considered as high-risk products under the European system than under the US system. There are roughly around 500 Class III products approvals annually in EU although in 2013, while there were 22 originals pre-market approvals approved by FDA.

These three main categories have not all been covered in previous mutual recognition agreements, however. The existing MRA between the EU and the US covers a positive list of Class I and Class II products. For Class I products, US companies that want to sell Class I products in the EU have to go through the same procedure as European-based companies selling products in Europe and vice versa. The catch is that a legal representative in the host country is required.

US (or other non-EU) producers need to contract a European Authorised Representative (EAR), i.e. a legal entity with a physical office within the EU. In the same way, European-based companies are required to have a US agent. In practice, the procedure implies, for example, that the American company pays both the EAR as well as the registration fees charged by the health ministries. The fact that the product is already registered with the FDA does not make any difference.[6] A patient or hospital using a device must be able to get in contact with the manufacturer if a problem occurs; therefore, adequate labelling, including appropriate contact information and instructions for use, must be provided. Relevant product information should also be available in the language(s) of the country where the product is sold as per national laws.

Medical devices for which clinical evidence would be required according to current legal requirements will be more difficult to address. As mentioned above, even if representing a very small number, some Class I products must pass premarket evaluation in the US The existing MRA covers evaluation reports from Conformity Assessment Bodies on Class I and II products, but only products for which third-party reviews are allowed in the US Class II products for which FDA has exclusive authority to assess safety and effectiveness are not included in the MRA, neither are high-risk Class III products. Safety, effectiveness and performance for medical devices

Safety, effectiveness and performance for medical devices

The Notified Bodies and the FDA operate under different mandates. In the EU, the NBs evaluate the safety and performance, which is a benefit risk assessment, of a device with respect to the intended use of the product as specified by the manufacturer. In other words, a product may be approved if the clinical evidence demonstrates that it works as intended. In comparison, the FDA uses other criteria. It assesses not only the safety of a product but also its effectiveness in relation to public healthcare objectives. The effectiveness criterion has been applied since 1962,[7] and is product-specific in the sense that the conditions vary depending on the product category. The FDA may, for example, consider the severity of the disease that the device is used to treat and the availability of alternative treatments. The FDA may also take into account whether a product is of lifesaving character or aims to improve the quality of life.

The differences in the mandates are arguably the main disparity between the European and the American systems. The effectiveness criterion applied by the US appears to be the main potential challenge when it comes to mutual recognition.

The more rigorous requirements in the US seem to be related to the different views on rights and obligations. Following legal question marks regarding the relationship between federal and state regulators, the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 established that federal regulations pre-empt state laws. The Supreme Court has upheld this principle in subsequent legal cases.[8] In simplified terms, this implies that a state court cannot overrule a decision by the FDA. In other words, it may be challenging to rule in favour of a patient suing a manufacturer on grounds that a Class III device approved through a PMA was not safe and effective, as FDA has already authorised it for marketing. In practice, this means that it would be difficult to sue a manufacturer of a Class III device which was approved through a PMA with respect to the safety and effectiveness of a product, as long as the manufacturer has correctly informed about potential foreseeable risks. Lawsuits are instead commonly based on the use or advice regarding the device, provided by hospital staff,[9] but may also be based on alleged manufacturing deficiencies.

In comparison, lawsuits in the medical sector are less common in Europe. In theory, it is nevertheless possible for users to claim compensation on grounds that the device is defective and that the manufacturer has been negligent.

Transparency and post-market supervision

Another difference is the transparency aspect of the approval procedures for medical devices. The FDA is more transparent in its works compared to the European NBs. For example, the FDA organises public advisory committee meetings to review safety and effectiveness data on new high-risk devices and the committee members are asked for their input and recommendations on approvability of the devices, although FDA always makes the final determination. FDA also publishes summaries of the documentation justifying the approval of high-risk devices. In addition, post-market data, i.e. the evaluation of the performance of the device following its approval, is made public and may be used as reference material in future premarket assessments. In contrast, the NBs in the EU are under no obligation to publish the data on the basis of which a new device is approved. Post-market supervision is the responsibility of the regulatory authorities of each Member State, but the level of transparency on those data is not yet consistent throughout EU. The new proposed EU Medical Devices regulation is proposing to increase transparency, including on post-market supervision.

Regarding post-market controls, both systems thus guarantee that if a product turns out to be defective, it can be swiftly withdrawn from the market. In the EU, both health ministries in the Member States and NBs have the competence and the authority to take a safeguard clause, or withdraw the certificate and/or to ask for the product to be recalled from the market which would be equivalent to revoking the marketing authorisation of a product. The EU Commission has the competence to judge if the safeguard clause is justified and shall be limited to a country or shall be extended to the whole of the EU. On the US side, FDA has authority over product recalls. However, generally in both systems such field actions are most often conducted on a voluntary basis by the manufacturer.

In summary, the US and EU systems fundamentally serve the same purpose of assuring product, patient and user safety. They are, however, forged differently. Notwithstanding the regulatory differences and challenges, mechanisms to integrate the markets for medical devices could be established in TTIP. Mutual recognition in different forms, aiming for regulatory harmonisation, is what will ultimately spur market integration.

* The facts on the regulatory systems included in the section build on USITC, FDA, Kramer et. al, and Chai

[1] Vastine, Jensen and Lee-Makiyama, The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership: An Accident Report, Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy, 2015

[2] European Commission, Medical devices in TTIP, April 2015

[3] MPO, Latest Budget Proposal Green-Lights Access to FDA’s User Fees, January 15, 2014, accessed at: http://www.mpo-mag.com/contents/view_breaking-news/2014-01-15/latest-budget-proposal-green-lights-access-to-fdas-user-fees/#sthash.L9UeD5qL.dpuf

[4] COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 920/2013 Of 24 September 2013 On The Designation And The Supervision Of Notified Bodies Under Council Directive 90/385/EEC On Active Implantable Medical Devices And Council Directive 93/42/EEC On Medical Devices

[5] Premarket Notification, Or The 510(K) Submission, Refers To the regulations in Section 510(k) of the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act

[6] Health Enterprises (2013) ‘Comments in Response to Request for Public Comment: “Transatlantic Trade & Investment Partnership”, Docket Number: USTR-2013-0019

[7] cf. Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962 to the Food and Drugs Act of 1906

[8] cf. Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962 to the Food and Drugs Act of 1906

[9] Bailey R. and Schleiter K.E. (2010)

WHAT IS ACHIEVABLE THROUGH TTIP

Let us now look at the possible scenarios of market integration in the framework of TTIP. At a bare minimum, the procedural gains as outlined by the European Commission are a part of any outcome. A common database for registration of medical devices based on a global unique device identifier (UDI) would permit hospitals or patients to properly identify the device, get in contact with the manufacturer, and allow traceability along the supply chain as well as fight counterfeiting.

But for the agreement to be a meaningful exercise, TTIP must overcome the regulatory divergences that we have outlined in the previous chapters, especially in how the products are classified and approved for market circulation, which is essential for market access and bringing societal costs down. TTIP must also go beyond the existing Transatlantic MRA that has failed to generate new trade, due to its narrow scope, especially for European exporters. The question of how to harmonise post-market governance of the markets and the role regulators play throughout the process follows the decision on how to open up both EU and US markets.

After all, the ultimate objective of all the scenarios is to accelerate innovation, enhance competition and increase cost-effectiveness, with a view to improve the health of the population. This imperative is urgent at a time when cost of the healthcare provision in the EU and the US is coming under increasing pressure and constraints. In the same way as the mutual recognition principle established by the Cassis de Dijon case triggered regulatory harmonisation in Europe; a bold agreement in TTIP could serve as a political catalyst for further transatlantic cooperation.

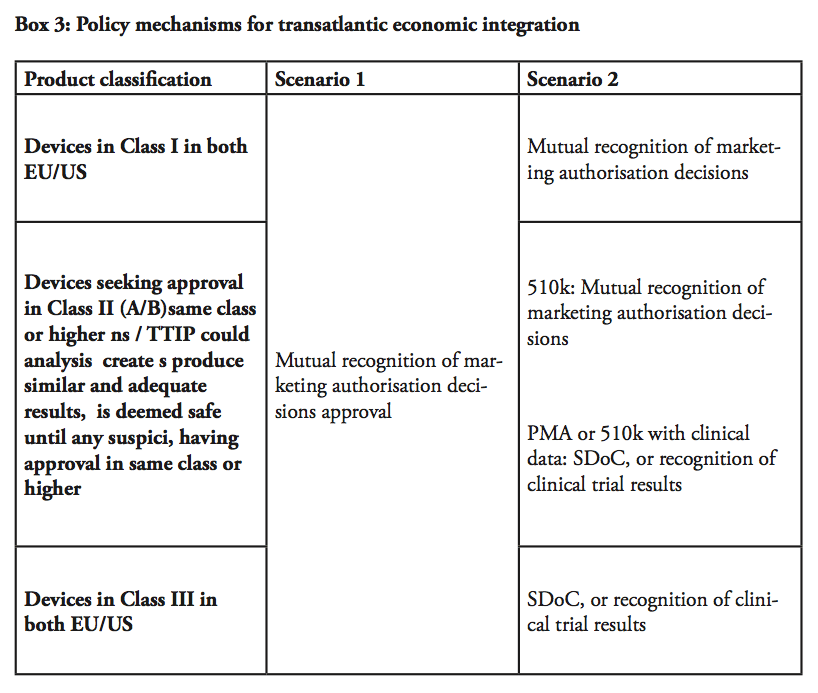

First scenario: recognising the equivalence between the systems

The most ambitious (yet the most obvious) step towards market integration would be to establish one single transatlantic market for medical devices by introducing mutual recognition of marketing authorisation or conformity assessment decisions, similar to the system established internally within the European Single Market. In practice, the FDA would have to recognise conformity assessment decisions by NBs in Europe, and European NBs would have to accept pre-market approval decisions by the FDA – once either of the jurisdictions allow a product into a market, it must be assumed that the product is safe to enter into the other market until they prove themselves to be not market worthy.

One could argue that full harmonisation of existing and future regulations and marketing authorisation procedures is a prerequisite of a full mutual recognition, and regulators would need to agree on similar product classifications and requirements. If so, a number of challenges lie ahead before such complete market integration can materialise, as all guidelines and assessment criteria would need to be streamlined through close regulatory cooperation. The experiences of the unfruitful regulator-to-regulator dialogue in the Transatlantic Economic Cooperation (TEC) seem to suggest that such regulatory harmonisation would take a long period of time.

It is safe to say that the EU’s Single Market would have never been completed in such a step-by-step approach to mutual recognition where full harmonisation was a pre-requisite. In fact, positive market integration (through harmonisation of national legislation) was a result of a negative one (mutual recognition) that deemed harmonisation necessary as products were entering into the domestic market in any case.

In this regard, it is a fundamental importance that the approval process of the EU and the US are already largely functionally equivalent – meaning they already produce similar, or near identical results using different means. The key difference between the EU and US systems is the effectiveness criteria used in the US approval process (arguably equivalent to the performance and benefit/risk factor in the EU), which is primarily a market criteria, meant to anticipate whether the device fills a gap in the market or whether alternative treatments already exist rather than whether the device is safe to use.

Moreover, both systems already have built-in acceptance of equivalence decisions: The European system is built upon delegated equivalent decisions between EU Member States and NBs, whereas in the US, equivalence (for predicates) exists in the 510(k) process. It is not too far-fetched to argue that US FDA is an agency equivalent to a European NB; or that a medical device already approved by European authorities is equivalent to an already approved predicate.

Post-market supervision could be coordinated in order to assure a uniform approach to product safety – if either side, i.e. the FDA, NBs, or a health ministry in an EU Member state, decide to withdraw a product from the market, it is very likely under any scenario that the device will be revoked from both the European and the US markets – especially if there is a common UDI database in place. However, it is also feasible that the mutual recognition ends at the market approval process, and that the revocation and appeals process would be subject to separate procedures under each jurisdiction. In other words, the mutual recognition provides a prima facie notion that a product safe under one legislation is deemed safe under the other, but each jurisdiction maintains the right to a different decision at a later stage. In this manner, the sovereignty of the public agency is maintained.

Second scenario: relying on existing FTA techniques (SDoC, duplicate testing)

In our second scenario, different conditions would apply depending on the product classification. For devices falling under Class I and certain Class II (falling under 501(k) or IIA), TTIP could establish mutual recognition of market authorisation decisions as per the earlier scenario, meaning that an authorised product could be marketed throughout the entire transatlantic market. It is important to bear in mind that in all scenario, we are dealing with devices that are already approved by one legislation, but not yet in the other – given most Class I products are self-certified through declaration of conformity (in the EU), or notified and listed (in the US), this outcome is practically the next incremental step of liberalisation for products for such devices.

Then remains high-risk Class III devices and class II devices, for which clinical evidence/trials are required. Even in the cases where the requirements in these evidence and trials differ between the EU and the US, the requirements are fully transparent and available to the manufacturer. The regulator could accept a self-declaration of conformity (SDoC) in such cases – in other words, a product that is already approved under the EU jurisdiction could be granted the right to self-certificate whether it also fulfils the criteria of the US jurisdiction, and vice versa – a technique that is applied in FTAs for other sectors, e.g. electronics, including potentially hazardous electrical equipment.

Alternatively, the FDA and NBs should be able to recognise clinical trials conducted in preparation for the submission on the other market. In this manner, already finalised clinical trials would not have to be remade. Similarly, the clinical evidence demonstration, which includes the literature review and assessment, would be made only once. However, there may be cases where additional documentation or tests not yet undertaken under the initial process may be required before a device can be authorised also in the second jurisdiction. The provisions in TTIP could, in this regard, draw from techniques for regulatory cooperation established in other sectors within the framework of prior FTAs. Balancing with post-marketing supervision

Balancing with post-marketing supervision

Two conclusions can be drawn from the prior analysis on divergences and the two scenarios. The first point concerns the level of ambition. As we have seen, the vast majority of products under Class I are either under self-declaration or exempt from notification. Whether TTIP is a worthwhile exercise is determined by what is already achieved for products in either Class II or III approved in one jurisdiction, but not yet in the other.

The second conclusion follows from the fact that the trade barriers, thus the majority of consumer productivity enhancements, are derived from the pre-marketing approval stage. Regulatory scrutiny is a balancing act between approval and post-market authority where a costly approval process may hinder innovation, whereas an overly lax approval process could potentially increase the need for post-marketing supervision. In both scenarios, the public agencies maintain their competences, while there should be no increased burden on the post-marketing phase – assuming that the systems are functionally equivalent.

This does not necessarily entail that there should be no co-operation in the post-marketing phase of regulation: One of the key areas that should certainly be considered is more alignment on requirements for re-certification of marketed products. Devices in the US do not need to be re-certified every 5 years after approval like in the EU. This has a little benefit in terms of patient safety, which is better supported by an appropriate post market supervision system while creating a high administrative burden in EU, which diverts resources from innovation.

Also – perhaps it goes without saying – in both scenarios, serious consideration should be given to institutionalising or formalising regulatory cooperation on new regulations or new guidelines between the jurisdictions, especially given the internationalisation work under the auspices of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum where both the EU and the US are stakeholders.

HURDLES FOR TTIP: RECENT DOMESTIC LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVES

In a dynamic technology like medical devices, TTIP has to maintain a certain flexibility. It must not hinder future regulatory reforms for either party. By the same token, current regulatory reforms should not put TTIP on hold.

There are ongoing legislative initiatives in the field of medical devices. Notably in the EU, where the European Commission recently proposed to reform existing directives (where implementation is left to EU Member States) into regulations on EU-level. If adopted, the proposals may imply significant changes to the marketing authorisation procedures for medical devices.[1]

The Commission’s initiative was triggered by a scandal in 2013. Not everything was in apple-pie order, as it turned out that the French company Poly Implant Prothese had been producing breast implants containing unauthorised silicone gel filler with potential health risks. Around 300 000 women in 65 countries were affected and the French health authorities subsequently recommended that patients remove the implants.[2]

The scandal raised calls for political action. The reaction of the Commission was to propose further harmonisation at European level including on the level of quality and expertise of Notified Bodies. Part of the stated purpose is to “[…] do away with diverging national registration requirements which have emerged over recent years and which have significantly increased compliance costs for economic operators”. It is proposed that a central European registration database is established. Transparency of the system would also be increased in order to increase the trust of the stakeholders in the system. Manufacturers will be required to “make publicly available a summary of safety and performance with key elements supporting clinical data”. In addition, Notified Bodies who were allowed to conduct unannounced factory inspections[3] are now mandated to perform unannounced audits on a regular basis.

While product safety is essential, the Commission is striking when the iron is hot to propose further centralisation. Arguably, however, there is no guarantee that a centralised registration system can assure product safety, but other requirements aiming at centralisation, like the central European registration database, would dramatically improve transparency and safety. A similar scandal could have happened both in a centralised and a decentralised system for granting market authorisation. Ultimately, it comes down to the conduct of manufacturers and whether or not it can be assured that they follow safety regulations.

Whatever the outcome of the Commission’s proposal, it does not run counter to further economic integration within the framework of TTIP. The European Commission goes as far as saying it does “not want to harmonise the approaches for the approval of a medical device in the EU and US”. This may be a matter of semantics – but neither mutual recognition nor abolishing of duplicate testing harmonises any laws in either jurisdiction – it merely creates an assumption that one product safe under one system is conforming with the criteria for approval until there is any suspicion of the contrary.

Regarding the legislative process for the upcoming regulation, the EU negotiators state that “TTIP does not, and will not, interfere with that internal process” – quite the contrary; the proposals would imply further centralisation and actually enhance the similarities between the US and the EU systems. This could, however, spell the end of the highly efficient and decentralised system in the EU.

Another possible stumbling block to transatlantic market integration are the divergent views on protection of personal data. In several state of the art medical devices register personal data is stored and processed, often offshore by the manufacturer or even a third party. Cross border data flows have become a necessity for delivering customised services and new products – and so even in medical devices and medical testing and research.

The European Commission recently proposed a new regulation, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), in view of updating the existing Data Protection Directive from 1995. GDPR would not only harmonise the national data protection within the EU Member States, but also by default prohibits the storing or processing personal data outside the EU, with limited exceptions. Meanwhile, the US applies a more lenient regulatory framework in the form of the Privacy Act of 1974, which does not apply to personal data on non-US citizens.

[1] cf. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on medical devices, and amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009, COM(2012) 542 poses to amend the regulatory framework for active implantable medical devices (AIMDD), medical devices (MDD) and in vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVD)

[2] BBC News Health (2013-12-10) ‘Q&A: PIP breast implants health scare’, available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/health-16391522

[3] European Commission (2012) COM(2012) 542 final

CONCLUSION

The medical devices sector could potentially be the main beneficent from regulatory cooperation within the framework of TTIP. In view of future demographic changes and a high demand for medical devices, the US and the EU now have the possibility to promote an already competitive industry where they have common export interests.

The US and Europe are (together with Japan) the main producers and users of medical equipment – it is not a cliché that increased competition, innovation and better market access can be life saving and bring quality of life and comfort to patients, as well as create resources for new jobs and new technologies.

The US and EU regulatory systems fundamentally serve the same purpose of assuring product safety, although a number of regulatory divergences remain. Subsequently, there is an economic rationale behind closer regulatory cooperation, which would remove unnecessary costs that occur because of duplicate assessments, without compromising on product safety.

Acknowledging that both the EU and US regulatory systems produce similar and adequate results, we see that there are two ways for these gains to come into fruition: In the first approach, any approved product from one jurisdiction would enjoy prima facie market approval in the other. In the second approach, manufacturers would be allowed to self-declare the conformity of an approved product from one jurisdiction in the other given they are in the equivalent product classification. As an alternative to self-certification, parties could at least abolish duplicate testing in their approval process.

In both approaches, the EU and the US would maintain their standards and not surrender any sovereignty or need to harmonise their relevant laws. However, the focus of their governance would turn towards post-market supervision.

Previous efforts of regulatory rapprochement have been fruitless. Medical devices therefore need to be part of a major political deal. A great amount of political will and engagement from industry and regulators will be required before regulatory harmonisation can materialise. Mutual recognition of marketing authorisation decisions or clinical trials or limiting the frequency of re-certification in Europe can generate further regulatory harmonisation and economic integration, ultimately to the benefit of patients in need.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (1999) ‘Agreement on Mutual Recognition in relation to Conformity Assessment, Certificates and Markings between Australia and the European Community’ and ‘Sectoral Annex on Medical Devices’, Australian Treaty Series 1999 No. 2

Australian Government, Department of Health (2012-11-30) ‘Medical device amendments to the EU-Australia MRA on conformity assessment to come into effect 1 January 2013’

Bailey, R. & Schleiter, K.E. (2010) ‘Testing Manufacturer Liability in FDA-Approved Device Malfunction’, Virtual Mentor, American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, Volume 12, Number 10, pp. 800-803

Chai, John Y. (2000) ‘Medical Device Regulation in the United States and the European Union: A Comparative Study’, Food and Drug Law Journal, Vol. 55, pp. 57-80

Eucomed (2013) ‘Medical Technology – key facts and figures’, accessed at: http://www.eucomed.org/facts-figures , accessed 2014-02-19

European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, EMEA (2004) ‘EC-Japan Mutual Recognition Agreement, Sectoral Annex on Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products’, EMEA/MRA/JP/8/04

European Commission, DG Enterprise (2001) ‘Guidelines for the classification of medical devices’, MEDDED 2.4/1 Rev.8, July 2001

European Commission (2012) ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on medical devices, and amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and regulation (EC) No 1223/2009’, Brussels, 26.9.2012, COM(2012) 542 final, 2012/0266 (COD)

Food and Drug Administration (2013) ‘CFR – Code of Federal Regulations 21CFR860.3 Medical Device Classification Procedures’

Food and Drug Administration (2014) ‘Medical Devices – Premarket Notification 510(k)’; ‘Medical Devices – Products and Medical Procedures – PMA Approvals‘, accessed at: http://www.fda.gov

Free Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States and the Republic of Korea (2010) Annex 2-D, Pharmaceutical Products and Medical Devices

Free Trade Agreement between the European Union and its Member States and Singapore, Annex 2-C, Pharmaceutical Products and Medical Devices

Free Trade Agreement between the United States and the Republic of Korea, Chapter Five, Pharmaceutical Products and Medical Devices

Kramer, D.; Xu, S.; Kesselheim, A. (2012) ’Regulation of Medical Devices in the United States and European Union’, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 366, Issue 9, pp. 848-855

MedTech Europe (2014) ‘The European Medical Technology industry in figures’, accessed at: www.eucomed.be

Official Journal of the European Communities (1999) ‘Agreement on mutual recognition between the European Community and the United States of America’, 4.2.1999, L 31/5

Official Journal of the European Communities (2001) ‘Agreement on mutual recognition between the European Community and Japan’, 29.10.2001, L 284/3

Sorenson, C.; Drummond, M. Burns, L. (2013) ‘Evolving Reimbursement and Pricing Policies for Devices in Europe and the United States Should Encourage Greater Value’, Health Affairs, Volume 32, No. 4, pp. 788-796

US International Trade Commission (2007) ‘Medical Devices and Equipment: Competitive Conditions Affecting US Trade in Japan and Other Principal Foreign Markets’, Investigation No. 332-474, USITC Publication 3909, March 2007

World Trade Daily (2011-07-21) ‘Trade Report: US Medical Equipment Exports; US Sellers & Foreign Buyers’, by Robert, T.