On the Importance of Placebo and Nocebo Effects in International Trade

Published By: Lucian Cernat

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements WTO and Globalisation

Summary

Trade agreements are powerful drivers of global economic integration, leading to increased trade flows between countries. Usually, trade agreements are extensive documents with hundreds of provisions and different levels of enforceability. Are all these provisions useful, even those that are “best endeavours” and do not introduce legally binding obligations on trading partners?

This policy brief proposes a new methodological approach to evaluate these effects. The basic idea is inspired by the “placebo effect” in medicine: under the right conditions, one can get positive results, even when the actual intervention is simply a “sugar pill”. Similarly, trade policies may have positive effects even when they lack strong, enforceable commitments. A placebo trade policy effect can emerge from “soft provisions” that bring positive trade effects, compared to the “do nothing” scenario.

The main hypothesis behind this new methodology is that even if trade interventions lack the force to solve problems outright, a positive placebo effect can arise if stakeholders believe that such a policy will generate favourable market access. Conversely, a negative nocebo effect might emerge when stakeholders are convinced that certain trade policy initiatives (notably FTAs) have a detrimental impact, despite undeniable evidence to the contrary.

The paper concludes with a few concrete examples illustrating both the placebo and nocebo effects and identifies factors that may lead to more positive outcomes from current and future trade policies.

*The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect an official position by the European Commission.

1. The Placebo Effect: Beyond Medicine

The placebo effect usually refers to a beneficial health effect that is triggered in patients not by the impact of a real treatment but by the patient’s belief in the effectiveness of the treatment. In a nutshell, the placebo effect can be summarised as a fake treatment (usually a plain “sugar pill” with no real pharmacologic action) that leads to real, positive health results.

Despite countless studies showing its existence, the placebo effect has divided the medical profession for centuries, between those who accept and embrace it, and those who deny or reject its benefits. This psychological effect where people’s own beliefs become a powerful source of change works not only in medicine but also in other areas. In the business world, it is well documented that consumers often believe and, therefore, judge higher-priced items to be of higher quality. The same product, when offered for a higher price, triggers a higher level of satisfaction in consumers than when offered for a discounted price (Shiv, Carmon and Ariely, 2005). Thus, high prices have a “placebo effect” in marketing. This proves that the old saying “one gets what one pays for” might be, at least subjectively, true.

Similar placebo effects are found not just in marketing but also in other areas, such as law enforcement and public policies (McConnell, 2019). Sometimes, the value of a policy intervention is not really in terms of trying to fix a problem (which perhaps could never be fixed), but in managing public perception and expectations, by showing that the government is seeking to address the problem. Thus, the term “placebo policy” captures the secondary effects of many government policies: governments need to be seen as doing something, even though the policy intervention might do little to actually address the problem. Psychology matters increasingly in public policies. Faced with growing complexities and the need to be “results-oriented”, policymakers worldwide have started to show growing interest in psychological factors and behavioural economics techniques, such as nudging, that can maximise the effectiveness of various public policies. Hence, identifying the factors that may lead to a placebo effect in the area of trade policy could be worth the effort.

2. Trade Policy and Placebo Effects

As in medicine, a “placebo policy” is an intervention that is not addressing the underlying problems faced in that particular area. Administering a placebo pill or policy is clearly a second best scenario. Ideally, any problem would be treated with a potent molecule or an effective intervention that would offer a long-lasting remedy, without any side effects. Unfortunately, both in medicine and public policies, there is no potent remedy for all our problems. This is where placebo trade policy interventions can bring about positive trade effects, compared to the “do nothing” scenario. Despite such a policy intervention not addressing materially and objectively a problem, there could be a placebo effect if the stakeholders believe in the possibility of such a policy to make a difference. There is some evidence in the academic literature of the existence of a placebo effect induced by several post-Brexit UK trade policy initiatives (Garcia, 2023).

A “trade policy placebo” could be defined as a policy intervention having no direct effect on trade conditions (e.g. tariffs, non-tariff barriers, other regulatory or administrative procedures), but its very existence makes stakeholders feel as if there are new trade and business opportunities created by the policy intervention, thus leading to more business efforts being put into trying to benefit from the new policy, which in turn leads to an increase in trade flows.

A placebo effect stemming from various trade policy initiatives is not necessarily a bad thing, quite the contrary. Being based on psychological factors, a placebo trade policy effect is somewhat similar in its underlying logic to the anticipatory effect of FTAs. The fact that trade deals have unexpected positive effects even when they do not exist yet has been amply documented. The economic literature has found that FTAs have positive anticipatory effects on trade flows, from the moment negotiations start. A strong presumption that an FTA will be concluded may be sufficient to generate an increase in exports before the conclusion and implementation of the agreement. Such anticipatory trade effects have been estimated to be as high as 25 percent (Magee, 2008). For the EU-Korea FTA, there is strong evidence suggesting that the EU increased its exports to Korea by 5.6 percent in the period after the start of negotiations, by around 10 percent between initialling and entry into force and by more than 14 following the entry into force of the FTA (Lakatos and Nilsson, 2017). Similarly, Latorre et al. (2021) found an increase in digital trade between the EU and Mercosur after the announcement that EU-Mercosur FTA negotiations were concluded.

Such anticipatory effects and the placebo effect have one thing in common: positive expectations. In the case of anticipatory effects, people expect FTAs to be concluded and their provisions to have tangible trade facilitation effects. However, unlike anticipatory effects, a placebo effect only occurs once the policy intervention is in place and depends crucially on the ability to convincingly present its potential benefits. In the case of FTAs, for instance, a placebo effect can be triggered by “soft law” provisions that may have only non-binding nature, or best endeavour clauses. While core FTA provisions need little or no advocacy efforts (e.g. tariff dismantling or other core market access issues), for a placebo effect to emerge with regard to other “softer” FTA provisions, a strong and persuasive communication effort projecting a positive narrative is needed to generate expectations. Such trade narratives require many elements, both facts and figures, but also (and perhaps more importantly) testimonials from exporting and importing firms.

If trust and expectations are created, a placebo effect is to be expected in the case of ‘soft’ commitments in trade agreements. Example of non-binding, placebo commitments in FTAs can be easily recognised by their wording, e.g. ‘recognise the importance’, ‘shall work towards’, ‘endeavour to’ or ‘promote’. Cooperation provisions are always considered as non-binding unless an obligation to cooperate in certain areas is made explicit in the text, within a specific framework and time.

According to Mcconnell (2019), the probability to obtain such a placebo effect from a “sugar pill” policy intervention depends, inter alia, on three important factors:

- Public visibility of the issue addressed;

- Expectations for policy intervention;

- Uncertainty about impact from policy intervention.

A placebo effect is more likely to occur when all these conditions are simultaneously met: high public visibility, high expectations and high uncertainty would likely lead to a stronger placebo effect. The public visibility is a basic prerequisite for a placebo effect to emerge as a result of policy interventions. Once public visibility is achieved, the next level is to ensure high expectations from stakeholders for the need of policy interventions. Uncertainty also affects the likelihood of placebo effects. In uncertain situations where no single policy intervention can be demonstrated to be (in)effective, the possibility to present certain trade provisions as potentially “beneficial” is higher (regardless of their proven impact), as long as expectations about them are also high. Hence, higher uncertainty is expected to lead to a higher likelihood of a placebo effect. Apart from FTAs, a separate set of policy instruments that are likely to produce a placebo effect are especially those that are non-legally binding in nature, such as Memoranda of Understanding and other types of trade “mini-deals”. The EU has in place over 2000 trade “mini-deals”, of various kinds and shapes in terms of their legally binding nature.

The distinction between core trade facilitation provisions and placebo clauses in FTAs is somewhat academic. In reality, most trade policy tools and interventions are a combination of effective “medicines” and placebos. Often, the placebo effect of a trade policy initiative can complement, rather than substitute, its real trade facilitation effects. Moreover, if trade agreements are very effective in certain areas, thus boosting their overall trade facilitation credibility, this would tend to reinforce the placebo effects even in areas where effectiveness would otherwise be low. Hence, the more effective a trade agreement is implemented in its “hard” provisions, the more likely it is to be perceived as effective even in its “soft” provisions, thus triggering a stronger placebo effect.

For example, the fact that EU FTAs have “soft” provisions that increase the visibility of an issue or expectations among stakeholders, even if such provisions do not necessarily lead to strong and real market access in the FTA partner, may nonetheless have a positive trade effect by mobilising a business response and increase the propensity to trade with FTA partners. Hence, regardless of the domain (medicine, business, politics) a placebo effect hinges critically on expectations and beliefs of the “consumers.” Without faith and a persuasive narrative, there is no placebo effect.

3. An Illustrative Example: The Case of Public Procurement

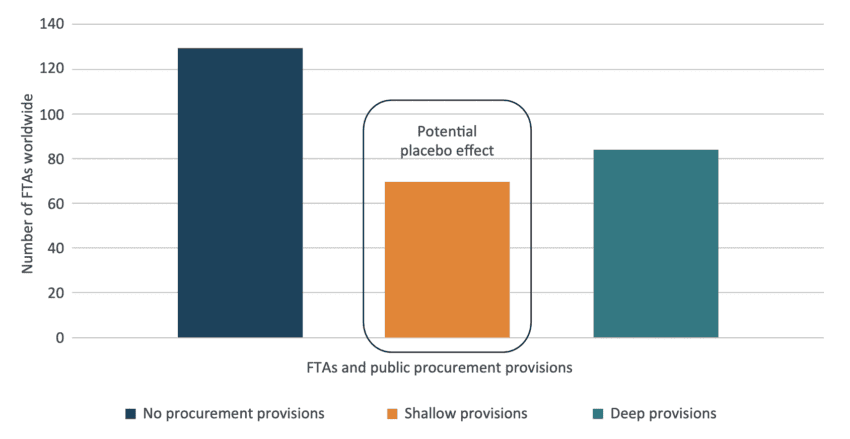

To illustrate the potential for a placebo effect to occur as a result of “soft” trade policy provisions in FTAs, let us examine the case of public procurement provisions found in the FTAs notified to the WTO (World Trade Organisation). Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020) have carried out a comprehensive and detailed assessment of FTAs notified to the WTO and categorised their “depth” across their main provisions. In the case of public procurement provisions, there are three distinct categories of FTAs: (i) FTAs with no procurement provisions; (ii) FTAs with shallow procurement provisions; (iii) FTAs with deep procurement provisions. Of the 283 FTAs in force as of March 2017, 129 agreements (about 45 percent) have no provisions on public procurement; 70 agreements (25 percent) have shallow provisions; and 84 agreements (30 percent) have deep provisions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: FTAs and types of public procurement provisions Source: Author’s elaboration based on the data contained in Mattoo, Rocha and Ruta (2020).

Source: Author’s elaboration based on the data contained in Mattoo, Rocha and Ruta (2020).

Among the 129 agreements with no provisions on public procurement, 85 FTAs are between South-South trading partners. The EU has a handful of such old agreements, mostly with small and/or developing states (e.g. Faroe Islands, Andorra, Lebanon, Syria, Papua New Guinea).

The group of shallow procurement FTAs is dominated by North-South agreements, which represent 50 of the 70 FTAs. Such agreements are, for instance, the US-Jordan, EFTA-Morocco, Türkiye-Israel FTA, or the EU-Cariforum FTA. Australia also has several North-South FTAs with shallow provisions on public procurement. But there are also North-North agreements, such as the EFTA-Canada or the EU-Korea FTA, where the bulk of the provisions qualified as shallow FTAs in public procurement.

Those FTAs with no procurement provisions are not expected to produce any placebo effect in this area, as the lack of such provisions indicate that the FTA partners have no intention to encourage cross-border activities and liberalise this sector. FTAs with strong procurement provisions are expected to generate a real trade facilitation impact. In contrast, shallow FTAs are particularly prone to produce trade placebo effects, if the expectations and the narrative surrounding the public procurement chapter are both positive. Even though the FTA provisions may not bring significant and legally binding guaranteed market access, a strong advocacy campaign about the procurement opportunities available in those FTA partners may increase business interest and the likelihood for companies to participate in international public procurement. Greater interest and participation from foreign bidders in the procurement market of shallow FTA partners may increase the likelihood of winning more public contracts by foreign bidders, despite the lack of guaranteed market access. Another effect might be stronger awareness by contracting authorities of the possibility to award contracts to firms located in the FTA partner, which can help reduce the otherwise natural home-bias effect in public procurement.

FTA public procurement chapters also provide a good example to illustrate the synergies that can be created between provisions that offer objectively strong trade benefits and the placebo trade provisions. The EU has signed not only FTAs with shallow procurement chapters, but also many more with deep procurement provisions, usually FTAs concluded in the last two decades. According to the World Bank analysis, there were only a handful of FTAs worldwide that were signed before the year 2000 that contained deep procurement provisions. In contrast, there has been a surge in the number of such agreements after 2000. The EU-Japan FTA, CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement), the EU FTA with the Andean community, and most recently the EU-New Zealand FTA are good examples of such FTAs with deep procurement provisions. Similarly, the GPA (Government Procurement Agreement) is also built on strong and deep procurement rules. The WTO GPA agreement is the only plurilateral trade agreement containing specific trade facilitation and market access provisions in the area of public procurement among several WTO members. Whenever such bilateral or plurilateral trade agreements lead to tangible procurement gains for EU bidding companies, there may be an increase in the positive expectations that arise from procurement chapters in shallow FTAs. As a result, these general positive expectations may reinforce the placebo effect of those FTAs containing only shallow procurement provisions.

Another type of actions that can lead to stronger placebo effect in the area of public procurement is the “easification” of FTA provisions via online tools such as the #Access2Procurement[1] (Cernat, 2021). Typically, FTA procurement provisions are complex and lengthy, running over hundreds of pages, and require a good understanding of the legal concepts contained therein. By simplifying those FTA provisions and allowing prospective bidders, including SMEs (small and medium enterprises), to figure out what rules apply to public procurement contracts in FTA partners, the #Access2Procurement tool increases the visibility of this topic and puts it on the radar screen of companies. Even though the tool may only offer such trade facilitation benefits for a subset of procurement contracts covered by the FTAs, once companies are “nudged” into trying to win public contracts abroad, those efforts may also pay off in winning contracts not covered by the FTAs, such as lower-value contracts below FTA thresholds. For instance, based on contract award data provided by Canada[2], more than half of all the federal public contracts won by EU firms in Canada between 2018-2022 were small-value contracts not covered by the CETA procurement chapter.

[1] European Commission (2024). Access2Markets. Retrieved from https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/procurement/#/country

[2] Government of Canada (2024). Procurement and contracting data. Retrieved from https://canadabuys.canada.ca/en/procurement-and-contracting-data

4. The 'Nocebo Effects' of Trade Policies

While the placebo effect is a familiar concept in common parlance, the “nocebo effect” is mostly confined to a scientific vocabulary. Put simply, the nocebo effect is the opposite of a placebo effect. It describes negative outcomes that can happen if someone believes something will cause them harm. For example, if you think a treatment will be painful, there is a higher chance that you will experience pain. The fact that the nocebo effect is not part of common parlance does not mean its occurrence is rare. On the contrary, there is psychological evidence suggesting that nocebo effects may have a larger incidence than placebo effects, as negative thoughts and perceptions are formed much faster than positive ones.

The nocebo effect can easily be generated by media campaigns. Widespread dissemination of concerns about adverse reactions to a medicine could lead to an increase in the number of reports about adverse reactions. For example, in 2013, British media highlighted the adverse effects of statins following an article in a scientific journal indicating such a possibility. An estimated 200’000 patients stopped taking statins within six months of the story being published, accusing side effects. The incidence of such self-reported side effects was much lower prior to the story (Brasil, 2018). Thus, the nocebo effect is proof that, in some cases the tail can wag the dog.

Is there evidence of nocebo effects in trade policy? One does not have to look far to find some potential candidates for a nocebo trade policy effect. The most recent one is the negative vote in the French Senate against CETA, based on the belief that French farmers have been negatively affected by this trade agreement. Over the years, many French politicians and farmers have been exposed to media reports arguing that, as a result of CETA, there will be a surge in Canadian exports of beef and other agricultural products that will compete unfairly with domestic products (Cabot, 2024). Although such an increase in imports never materialised, the nocebo effect persisted and no trade statistics proving the contrary could reverse the negative attitude vis-à-vis CETA. The nocebo effect of CETA was strong enough to dominate the overall debate and neutralise the statistically documented CETA benefits for French farmers, notably for cheese producers.

Similar nocebo effects have also been generated by the EU-Mercosur FTA, with recent protests by European farmers citing this “not-yet-there” FTA as one of the causes for their current and future economic difficulties (Chini, 2024). Such examples confirm that whether it is about medicine or public policies, perceptions and psychological factors play an important role. Hence, any policy maker ignoring potential placebo and nocebo effects will do so at their own peril.

5. How to Make the Most Out of Placebo Effects in Trade Policy?

This short paper is not meant to provide definitive answers or an exhaustive empirical analysis on the existence of a placebo effect in trade policy but rather to trigger subsequent reflections and more in-depth analyses on the positive effects that can be derived from promoting the “placebo effects” of trade policy, not just its “clinically proven”, tangible trade facilitation effects.

A few tentative remarks may be valuable for future reflections. First, the perceived value of an FTA can be augmented by the placebo effect of “soft” FTA provisions, if the necessary conditions for a placebo effect to occur are in place. For instance, the effect of such placebo provisions can be enhanced if accompanied by a strong communication and advocacy campaign (Cernat, 2018). It is worthwhile investing in communication efforts that increase the awareness among stakeholders of trade policy initiatives. More visibility means stronger placebo effects.

Second, direct engagement with business associations and individual companies and raising expectations among stakeholders of the potential business opportunities offered by trade policy can also increase the likelihood of placebo effects. This is especially important in areas where uncertainty is high and acts as a trade barrier, and where tangible effects are obtained if businesses are persuaded of long-term benefits stemming from “soft” provisions in trade agreements.

Third, detailed firm-level data and success stories confer more credibility to both real and placebo policy effects, rather than dry, macroeconomic figures (Cernat and Díaz, 2024). Exporter stories[1] and concrete firm-level examples can be more persuasive than statistical analyses. Hence, the need to have more such anecdotal information about various trade policy initiatives, including the “soft law” areas, to create favourable conditions for a placebo effect to occur.

To conclude, if faced with a choice between having no FTA chapter in a particular trade policy area, or some “placebo” provisions in a chapter with a lower level of ambition, there are good reasons to choose the latter, if strong expectations are in place from stakeholders for such an FTA chapter. In the current context, it is important to put forward solid and convincing arguments that lead to a positive perception about the impact of trade policy, including its potential placebo effects. Since, as Edward de Bono (a famous psychologist) once said: “Perception is real even when it is not reality.” (de Bono, 2011:37).

[1] European Commission (2024). Belgium – Bidding for public contracts under the EU-Canada trade agreement. Retrieved from https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/exporters-stories/belgium-bidding-public-contracts-under-eu-canada-trade-agreement_en

References

de Bono, E. (2011). The six value medals: The essential tool for success in the 21th century. Ebury Digital Press.

Brasil, R. (2018). Nocebo: the placebo effect’s evil twin. The Pharmaceutical Journal 300 (7911): 05.

Cabot, C. (2024, January 31). ‘Unfair competition’: French farmers up in arms over EU free-trade agreements. France24, Retrieved from https://www.france24.com

Cernat, L (2018). How to make trade policy cool (again) on social media? ECIPE Blog. https://ecipe.org/blog/how-to-make-trade-policy-cool-again-on-social-media/

Cernat, L. (2021). Trade policy 2.0 and algorithms: towards the “easification” of FTA implementation. Series Perspectives Cirano No. 2021PE-05, Montreal.

Cernat, L. & Díaz, C. (2024). CETA and SMEs: a firm-level trade assessment. ECIPE Blog. https://ecipe.org/blog/ceta-and-smes/

Chini, M. (2024, February 27). ‘Sowing despair and misery’: Farmer protests denounce EU’s free trade agreements. The Brussels Times, Retrieved from https://www.brusselstimes.com

European Commission (2024). Access2Markets. Retrieved from https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/procurement/#/country

European Commission (2024). Belgium – Bidding for public contracts under the EU-Canada trade agreement. Retrieved from https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/exporters-stories/belgium-bidding-public-contracts-under-eu-canada-trade-agreement_en

Garcia, M. J. (2023). Post-Brexit trade policy in the UK: placebo policy-making? Journal of European Public Policy, 30(11), 2492–2518.

Government of Canada (2024). Procurement and contracting data. Retrieved from https://canadabuys.canada.ca/en/procurement-and-contracting-data

Lakatos, C. and L. Nilsson (2017). The EU-Korea FTA: anticipation, trade policy uncertainty and impact. Review of World Economy, 153, 179–198.

Latorre, M. C., Yonezawa, H. and Z. Olekseyuk (2021). El impacto económico del acuerdo Unión Europea-Mercosur en España, Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo.

Magee, C. S. (2008). New measures of trade creation and trade diversion. Journal of International Economics, 75(2), 349-362.

Mattoo, A., N. Rocha, M. Ruta (eds.) (2020) Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements. World Bank: Washington.

McConnell, A. (2019). The use of placebo policies to escape from policy traps. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(7), 957-976.

Shiv, B., Carmon, Z., and D. Ariely (2005). Placebo effects of marketing actions: Consumers may get what they pay for. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(4), 383–393.