The Participation of Foreign Bidders in EU Public Procurement: Too Much or Too Little?

Published By: Lucian Cernat

Research Areas: European Union

Summary

This policy brief examines EU public procurement data from the Tenders Electronic Daily (TED) to evaluate foreign bidders’ participation and success in winning EU public contracts. Despite data coverage limitations, the available information shows an increase in foreign participation in both full and partial contracts, with most activity concentrated in a few countries. Countries like the United States, Japan, and Canada focus on securing full contracts, while nations such as Norway and Turkey often engage through partial contracts. Notably, since Brexit, UK bidders have faced a significant decline in market share, benefiting other countries.

The main conclusion is that foreign participation via cross-border procurement (Mode 1) – the only one available in the TED database – is not very high. Although it increased over time, it remains relatively modest, mainly due to low participation rates, rather than discriminatory practices. Between 2016 and 2019, only about 7 percent of EU procurement authorities received foreign bids. This fact alone largely explains the low level of cross-border procurement taking place via Mode 1: put simply, there is no winning without trying.

Another important conclusion is that a comprehensive assessment of the participation of foreign bidders in EU procurement would require two new key metrics in the TED data collection process to capture the more important yet missing modes of international procurement. Having reliable and comprehensive data is not just an academic pursuit but a necessity for shaping effective EU policy in the face of rising global protectionism in public procurement.

1. Recent Trends in International Procurement

Public procurement has recently attracted significant attention from policymakers in the context of the new industrial policy debates. The idea behind the strategic use of public procurement for industrial policy purposes is that public spending that is specifically directed towards domestic suppliers will lead to a revival of certain economic sectors. The United States has a longstanding history of implementing “Buy American” in public procurement policies in favour of domestic producers. For instance, the first Trump administration enacted three executive orders aimed at reinforcing and maximising the effectiveness of all “Buy American” procurement rules.[1] During his first week in office, President Biden also signed an executive order strengthening the “Buy American” rules to increase the federal government’s procurement of American-made goods.[2] The US domestic content threshold increased to 60 percent in 2022, was further increased to 65 percent in 2024, and is planned to reach 75 percent in 2029. A new “Made in America” Office was created to oversee these new initiatives. In his second term, President Trump issued a new “America Trade First Policy”[3] executive memorandum on 20 January 2025, instructing the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to review the impact of all trade agreements, including the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), on the US federal procurement, with a view to ensure that such agreements are being implemented in a manner that favours domestic manufacturers.

The US is not the only country with “buy local” requirements or domestic preferences in procurement. China has also implemented a series of legislative measures for decades aimed at favouring domestically produced goods and services in public procurement contracts. In December 2024, the Chinese Ministry of Finance released new draft standards for government procurement that include, inter alia, a 20 percent price preference for domestic products (Global Trade Alert, 2024). These are only a couple of examples showing how different countries try to use discriminatory public procurement policies favouring domestic bidders but the list could continue, since international public procurement worldwide is affected by a plethora of such barriers in many countries (e.g. India, Indonesia, Brazil, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Tunisia, Morocco, Colombia, Australia, etc.) either across the board or in specific sectors (Cernat, 2023).

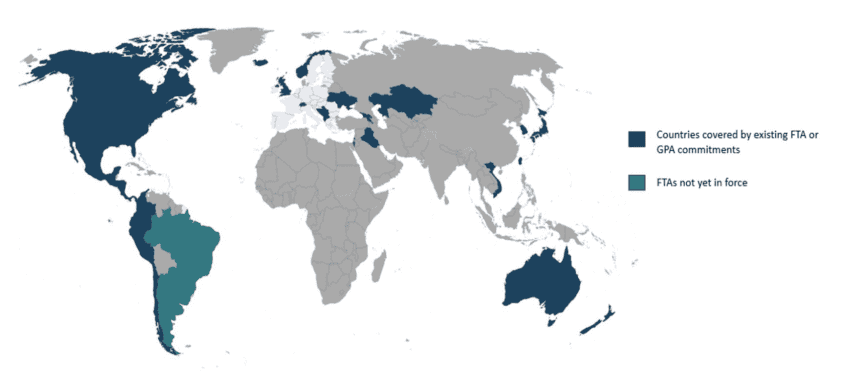

To address the lack of reciprocity in public procurement in a world plagued by so many procurement barriers, the EU adopted in 2022 the International Procurement Instrument (IPI). The IPI is an essential instrument in the EU strategy aimed at the strengthening global competitiveness of EU companies and the bargaining power of the European Union in public procurement. The IPI empowers the EU to initiate investigations in cases of alleged restrictions in third-country procurement markets, engage in consultations with the country concerned on the opening of its procurement market and, if all attempts fail, reciprocate with proportionate restrictions in the EU procurement market against those countries. The EU has been, and remains, by and large, open to foreign bidders. Unlike other jurisdictions, there are no “Buy European” rules. The EU also has the largest network of trade agreements containing binding legal obligations for reciprocal access to public procurement markets with 38 countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Countries with binding reciprocal procurement provisions in trade agreements vis-à-vis the EU Source: Author’s elaboration.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

As a result, with such an open procurement market, one would expect market penetration by foreign firms on par with, or close to, the overall EU trade openness. However, the public procurement market differs from international trade markets. In public procurement, distance and gravity matter much more than in the rest of the economy. Public procurement is often affected by home bias. While the world median trade distance for business-to-business (B2B) international trade transactions is almost 5000 km (Berthelon and Freund, 2008), in public procurement, the distance between public buyers and their suppliers is far smaller. A study of the EU procurement market found that around 40 percent of suppliers were located less than 500 km from the public procurement buyers, and less than 5 percent of suppliers were located more than 2000 km away from public buyers (European Commission, 2021).

The level of competition in public procurement is also often lower than in the private market. A recent report by the European Court of Auditors found that 40 percent of public contracts are awarded to firms located in the same region (ECA, 2024). The Single Market Scoreboard for public procurement also found that for a large share of public tenders, contracting authorities receive only one offer. In 2022, the proportion of public procurement tenders with a single bidder rose to its highest level in the past 10 years. Moreover, only a small fraction of procurement tenders received offers from foreign bidders. Recent studies carried out by the European Commission found that the share of public procurement contracts awarded to non-domestic firms (i.e., firms situated either in other EU countries or in third countries) remains below 5 percent (European Commission, 2021).

This low level of cross-border participation in public procurement (also known as Mode 1 procurement) raises concerns about competition in the EU procurement market. Fortunately, Mode 1 procurement does not tell the whole story. In reality, there is more international participation in public procurement than meets the eye. International procurement also takes place via foreign affiliates (Mode 2 procurement) and indirectly through subcontractors or outsourcing (Mode 3 procurement). Unfortunately, data for Mode 2 and Mode 3 procurement are not currently available.

Despite this important gap, existing estimates indicate that these missing procurement modes are more important than Mode 1 (direct cross-border procurement). Cernat and Kutlina-Dimitrova (2020) estimated that, in 2017, the value of international procurement (i.e. public contracts won directly or indirectly by non-EU companies) across all modes was in the range of €50 billion, with Mode 2 accounting for the largest share of total international procurement. For that year, the value of EU public procurement contracts covered by the GPA amounted to around €360 billion. In percentage terms, this means that foreign companies won around 14 percent of the EU procurement market that was open for international procurement. When all the procurement modes are considered, EU openness in public procurement appears to be, by and large, comparable to the overall openness of the EU economy: in 2017, the share of EU imports (goods and services) in GDP was around 17 percent. However, as indicated above, home bias in EU public procurement still persists, notably with regard to Mode 1 procurement.

[1] Executive Order 13788 of April 18, 2017 (Buy American and Hire American), Executive Order 13858 of January 31, 2019 (Strengthening Buy-American Preferences for Infrastructure Projects), and Executive Order 13975 of January 14, 2021 (Encouraging Buy American Policies for the United States Postal Service).

[2] Executive Order (EO) 14005 of January 25, 2021 (Ensuring the Future Is Made in All of America by All of America’s Workers).

[3] America First Trade Policy Presidential Memorandum of January 20, 2025, The White House. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/america-first-trade-policy/

2. Mode 1 Procurement: Dissecting the Low-Hanging Fruit

Although Mode 1 procurement accounts for a small share of overall international procurement, the readily available data on cross-border procurement (Mode 1) from the Tenders Electronic Daily makes it an ideal low-hanging fruit, allowing for a more in-depth analysis of the participation of foreign bidders in EU public procurement.

One interesting dimension that can be explored via the detailed firm-level data available from the Tenders Electronic Daily about the participation of foreign bidders in EU public procurement relates to the ability of foreign bidders to win either full contracts or only parts of them when public procurement contracts are divided into lots or when foreign bidders are part of international consortia. The EU Public Procurement Directive 2014/24 encourages contracting authorities to divide large contracts into lots as a way to increase competition and the participation of SMEs in public procurement. Splitting contracts into lots, however, is not always possible or advisable. Certain studies argue that splitting contracts into lots may, under certain conditions, encourage bid rigging, collusion, and economic inefficiencies (Grimm et al., 2006; Giosa, 2018).

The EU rules favour a “divide or explain” logic, whereby individual contracting authorities are responsible for deciding on procurement methods, the number and value of various lots, etc. Dividing contracts into lots may also affect foreign bidders’ participation. Contracts that are divided into lots may increase the chances of a new entrant obtaining a public contract abroad, especially if the contracting authorities include specific pro-competition provisions reserving certain lots for new entrants and avoiding single-supplier dependency (OECD, 2016). In contrast, a study conducted by the European Commission found that certain suppliers consider that dividing a contract into too many small lots decreases the incentives of foreign firms to submit a bid and thus reduces the value of cross-border Mode 1 procurement (European Commission, 2021).

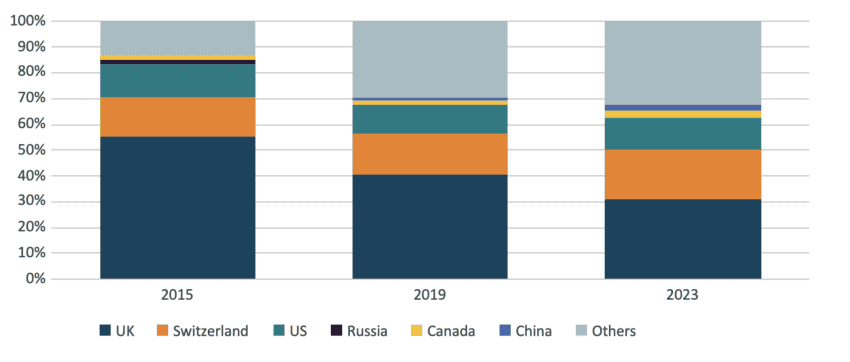

This raises an interesting empirical question: is there too much or too little participation by foreign bidders in EU public procurement procedures? To answer this question, the EU Tenders Electronic Daily (TED) database could be used. Looking at the period between 2011 and 2023 (the data for 2024 is incomplete), the TED data indicates that participation by foreign firms in EU procurement is diverse, yet also fairly concentrated. Even though the share of contracts awarded via Mode 1 to firms located outside the EU remained at a fairly low level, it has tripled over that period, with bidders from over 100 non-EU countries winning at least one public procurement contract from EU contracting authorities. At the same time, firms located in the UK, Switzerland, and the US won over 80 percent of all contracts awarded to foreign firms located outside Europe in 2015. Although this geographical concentration declined over time, the UK-Swiss-US trio still accounted for over 60 percent of contracts awarded to foreign firms in 2023 (Figure 2).

As Figure 2 indicates, this increased diversification of foreign bidders participating in the EU procurement market appears to have been triggered by Brexit. One way to estimate the Brexit effect on public procurement is to notionally consider that British firms as “foreign” prior to Brexit, to compare their performance before and after Brexit. The Brexit effect on the success rate of UK firms in the EU procurement market is quite stark: during the 2011-2018 period, UK “foreign” firms won one out of every two EU public contracts awarded to foreign firms. In 2024, UK firms were winning only one out of three EU public procurement contracts awarded to foreign firms. Thus, as a result of Brexit, the market share of UK firms in EU procurement awarded to foreign bidders shrank from over 50 percent to around 30 percent in 2023. The incomplete and preliminary data indicates that this downward trend continued in 2024.

This is a rather unexpected development, given that access for UK firms to the EU procurement market under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement remained mostly unchanged, compared with the pre-Brexit conditions. This significant drop in UK firms’ participation in the EU procurement market could be understood as another manifestation of the “nocebo trade effect” (Cernat, 2024). The basic idea behind the placebo-nocebo effects of trade policy initiatives is best understood through a quote from Edward de Bono, a renowned psychologist: “Perception is real, even when it is not reality”. The nocebo effect refers to a negative outcome that can happen if someone believes something will cause them harm. In the case of Brexit, negative perceptions about increased trade barriers created by the fact that the UK was no longer part of the Single Market may have led UK firms to belief that they no longer enjoyed the same level of access to the EU procurement market, even though that was not actually true.

Figure 2: The EU procurement market: top foreign winners  Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Tenders Electronic Daily database. The chart is based on the total number of EU public procurement contracts won by foreign firms (both full and partial contracts).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Tenders Electronic Daily database. The chart is based on the total number of EU public procurement contracts won by foreign firms (both full and partial contracts).

The other noticeable change between 2015 and 2023 is the significant increase in the share of bidders from “other countries”. While the countries included in this category are highly heterogeneous, a possible complementary explanatory factor for this trend is that, since 2015, the EU has continued to expand its network of trade agreements, which offer legally guaranteed market access to the EU for several trading partners. Unlike the Brexit-induced nocebo trade effect, the growing number of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) may have triggered a (positive) placebo trade effect: even though third-country bidders were not subject to discriminatory or exclusionary measures in the EU procurement market, having a trade agreement in place that offers legally guaranteed market access may have increased the propensity of third-country bidders to successfully participate in the EU procurement market.

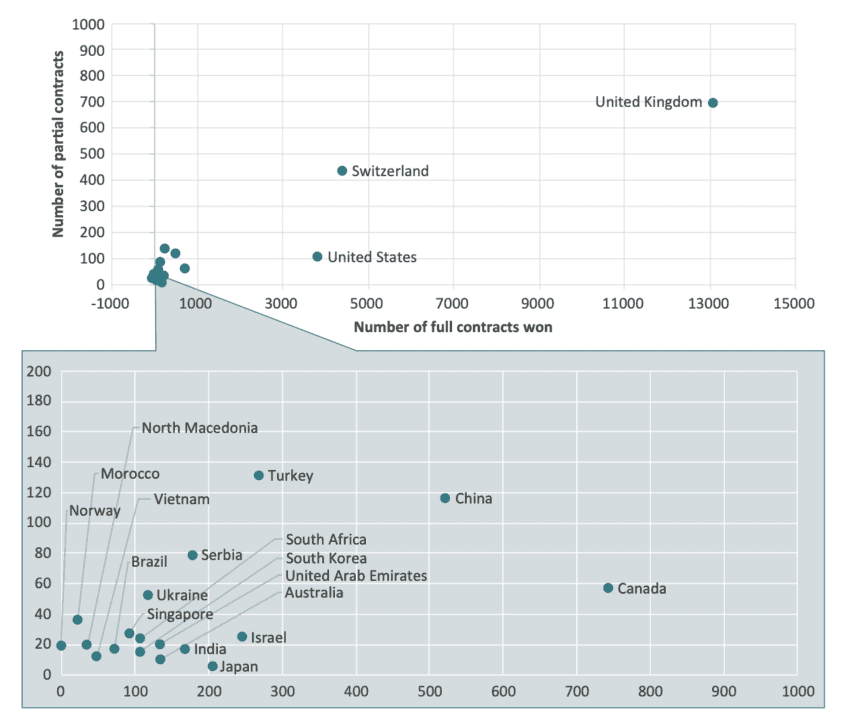

A second empirical question is whether foreign bidders are successful in the EU procurement market when contracts are split into lots or when they are part of international consortia. The TED data indicates that foreign firms won both full and partial contracts. Figure 3 illustrates the differences between various foreign bidders in terms of two metrics: (i) the number of full contracts won on the x-axis; and (ii) the number of partial contracts won by foreign bidders (either when contracts are split into lots or won via consortia) on the y-axis. As seen before, the UK, Switzerland, and the US remain the dominant players among foreign bidders in terms of the number of contracts won either fully or partially. A second tier of successful foreign bidders also comes from countries that are relatively close to the EU or countries that benefit from preferential market access to the EU via various trade agreements, such as Canada, Turkey, Israel, Japan, and Serbia. China is the only country that appears in the top five countries participating in the EU public procurement without having the proximity advantage or a secure preferential market access via trade agreements (FTAs or the WTO GPA).

Another interesting feature illustrated in Figure 3 is that the relevance of partial contracts remains fairly limited for most foreign bidders. In the case of bidders from major foreign countries (UK, Switzerland, and the US), the vast majority of contracts won by foreign bidders are full contracts. This confirms the findings of previous studies indicating that foreign bidders are discouraged from participating in contracts split into lots (European Commission, 2021).

Figure 3: Top foreign bidders in EU procurement: full contracts vs partial wins (2011-2024) Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Tenders Electronic Daily database. Apart from the UK and Switzerland, which are the countries with the largest number of contracts won in Europe, the chart includes the next top 20 countries that won the largest number of contracts in the EU over the 2011-2024 period (both full and partial contracts).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Tenders Electronic Daily database. Apart from the UK and Switzerland, which are the countries with the largest number of contracts won in Europe, the chart includes the next top 20 countries that won the largest number of contracts in the EU over the 2011-2024 period (both full and partial contracts).

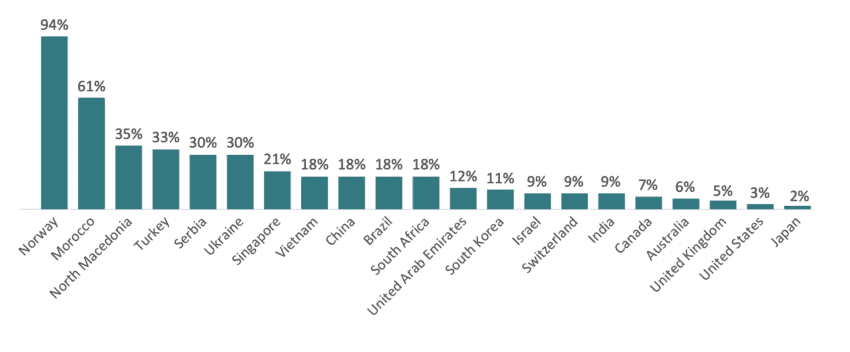

While the share of partial contracts in the total number of contracts won by foreign bidders over the 2011-2024 period remained on average at around 7 percent, for a number of countries, the recipe for success in the EU procurement market was precisely the participation in contracts split into lots or as part of an international consortium (Figure 4). For instance, Norwegian bidders seem to have almost exclusively won contracts that were split into lots and via consortia. Moroccan bidders are also particularly successful at winning partial contracts: over 60 percent of all contracts won by Moroccan bidders were partial contracts. Contracts divided into lots were also important for bidders from Turkey, Serbia, Ukraine, Singapore, Vietnam, China, Brazil, and South Africa. US and Japanese firms were the least interested or successful in participating in contracts divided into lots.

Figure 4: Partial contracts for foreign bidders (% of total contracts won) Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Tenders Electronic Daily database.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Tenders Electronic Daily database.

3. Going Beyond Mode 1: Further Improvements in the Monitoring and Analytical Toolbox of EU Public Procurement

The overall conclusion from this analysis is that foreign firms have continued to enjoy unrestricted access to the EU procurement market, leading to increased participation and a higher success rate in winning both full and partial contracts. Contrary to previous evidence, although most contracts won by foreign firms are in cases where contracts are not split into lots, for several countries, partial contracts and participation in international consortia provide them a better chance of winning a lot in a larger contract and establishing a presence in the EU procurement market.

Is the participation of foreign bidders in the EU procurement market too little or too much? The full answer is more nuanced than a simple “yes” or “no”. When looking at cross-border procurement (Mode 1), the only mode for which detailed data is readily available from the TED database, the answer cannot be “too much”. Although the participation of foreign bidders (in terms of the number of contracts won) has increased over time for both full and partial contracts divided into lots, overall participation remains relatively modest and concentrated in a small number of countries. It is also revealing that the main reason for this low success rate in winning contracts in the EU procurement market is not due to discriminatory measures, but mostly due to a lack of participation. For instance, only around 7 percent of all EU public procurement authorities received an offer from a foreign bidder during the 2016-2019 period (European Commission, 2021). This fact alone explains the low level of cross-border procurement taking place via Mode 1: simply put, there is no winning without trying.

Beyond Mode 1, the participation of foreign firms in the EU procurement market is more substantial. Foreign companies win contracts either via their EU subsidiaries (Mode 2 procurement) or as subcontractors and second-tier suppliers to the successful bidders, including EU firms. These broad conclusions are well supported by the limited existing evidence. However, the current state of the EU toolbox for monitoring international procurement is inadequate. A more detailed and comprehensive assessment of foreign participation in EU public procurement would require the introduction of two key metrics in the current monitoring platforms used to collect data on public procurement in Europe. The first indicator is the ultimate ownership of successful bidders. This indicator would allow a comprehensive assessment of Mode 2 procurement. The information required to create this key performance indicator is already available due to the legal requirements with regard to ultimate business ownership introduced by the Fourth EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which requires EU member states to set up registers of the ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) of legal entities.

The second key, yet missing, indicator that would be required to monitor the magnitude and the detailed structure of Mode 3 procurement is the origin of the goods and services procured in Europe, irrespective of the nationality of the successful bidder. This is arguably a more difficult metric to introduce in the EU procurement process, given the difficulties in anticipating the origin of goods and services to be supplied under a public procurement contract, at the moment of the bidding process. However, for those bidders that are the manufacturers of the goods to be supplied, this information is straightforward and can be provided on the basis of self-declaration of origin by the manufacturing company. For those bidders planning to import, outsource, or subcontract all or parts of the goods to be provided, the information would be based on the usual certificates of origin required by the EU customs authorities. For services, well-established rules exist to determine their origin, including for software and other digital services (cloud computing, data storage, etc.). Thus, information about country of origin for goods and services can be provided and uploaded into the TED platform at the execution and delivery phase of the contract.

Having these two key metrics as part of the mandatory fields required by the TED platform whenever tenders and contract award data are published by all EU contracting authorities will allow for a rigorous answer to the “too little or too much” question. This is not merely an academic question. Given the need to put in place an effective EU policy in response to growing protectionism and the acute polarisation of public procurement policies in many trading partners, getting the basic facts right is a necessity, not an option.

References

Berthelon, M. and Freund, C. (2008) On the Conservation of Distance in International Trade, Journal of International Economics, 75(2), 310-320.

Cernat, L. (2024) On the Importance of Placebo and Nocebo Effects in International Trade, ECIPE Policy Brief no. 13/2024. Available at: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_13-2024_LY02.pdf

Cernat, L. (2023) The International Procurement Instrument (IPI): promoting a level playing field around the world. ICE, Revista De Economía, (930).

Cernat, L., and Kutlina-Dimitrova, Z. (2020) Public Procurement – How open is the European Union to US firms and beyond?, CEPS Papers 26698, Centre for European Policy Studies.

European Court of Auditors (2023) Public procurement in the EU – Less competition for contracts awarded for works, goods and services in the 10 years up to 2021, Special report 28/2023.

European Commission (2019) Analysis of the SMEs’ participation in public procurement and the measures to support it. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42102.

European Commission (2021) Study on the measurement of cross-border penetration in the EU public procurement market – Final Report, Brussels.

Giosa, P. A. (2018) Division of Public Contracts into Lots and Bid Rigging: Can Economic Theory Provide an Answer? European Procurement & Public Private Partnership Law Review, 13(1): 30-38.

Global Trade Alert (2024, December 5) China: Proposed preference margin in public procurement for goods produced in China. Available at: https://www.globaltradealert.org/state-act/89636/china-proposed-preference-margin-in-public-procurement-for-goods-produced-in-china

Grimm V., Pacini, R., Spagnolo, G. and Zanza, M. (2006) Division into lots and competition in procurement. In: Dimitri N, Piga G, Spagnolo G, (Eds), Handbook of Procurement. (pp. 168-192). Cambridge University Press.

OECD (2016) Division of Contracts into Lots, SIGMA Policy Brief no. 36, OECD Publishing. Available at: https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/public-procurement-policy-brief-36-200117.pdf