Negotiating Uncertainty in UK-EU Relations: Past, Present, and Future

Published By: David Henig

Research Areas: EU Trade Agreements UK Project

Summary

Ten key points to negotiating the UK-EU relationship

Europe has been weakened by difficult UK-EU relations at a time of international challenge. Eight years after the Brexit referendum a new UK government and European Commission provides a good opportunity to reset approaches and put obstructions aside. Too big for either side to ignore, this will always be an important, time-consuming, and slightly chaotic relationship – which thus needs a much firmer footing based on the following shared understanding:

- Probably the broadest, deepest bilateral relationship in the world, adding the world’s second largest trade flow to integrated neighbourhood challenges, meaning inevitable complexity and ongoing negotiation of many different topics. This has been insufficiently recognised, and should ideally be considered jointly, e.g. in terms of a shared vision, road map, scoping, implementation, otherwise even agreeing sequencing will always be problematic;

- Wide scope, with inevitable challenges and tensions, requiring regular senior-level contact, this should start with annual summits that develop mutual understanding, supported by regular meetings between UK Ministers and Commissioners, senior official meetings, and the sharing of information at expert level. There should not be a single undertaking negotiation;

- Divorce taking time to overcome, emotions on both sides are settling but still livelier than normal between nominal allies, with many involved who would simply like the unattainable return to the pre-2016 state, and others just as strongly opposed in various ways;

- EU needs to be less rigid given the UK will not neatly fit into existing models, there being too many mutual interests, from which will flow multiple arrangements and deals. Showing greater willing to a now more constructive counterpart means creativity in how to structure the relationship to deliver mutual interests as well as specific asks of both sides;

- Negotiations must informally include many actors, such as businesses, civil society, lower-level governments, academics, listening to whom should be the basis for the UK and EU shaping mutually acceptable deals. All of these stakeholders will equally have to learn to live with the uncertainty and difficulties of an ongoing relationship with multiple strands;

- UK previously a naïve negotiator failing to understand this collaborative yet still competitive, and increasingly public, nature of modern trade negotiations, or its new third country status. Positive signs of learning shown with the Windsor Framework should be developed – to include ‘Team UK’ negotiating, openly testing ideas with specialists, and understanding the EU, importance of trust in implementation, and limits of taking back control;

- Northern Ireland will always require special handling as a part of the UK whose peace process requires strong relations with the rest of the country and the EU. Ambiguity and flexibility will continue to be needed;

- There is no perfect model for future UK-EU relations, all potential options having drawbacks rendering them somewhat unstable, and no swift negotiating path to most of them. While the UK is not a member of the EU there will always be barriers to trade and movement of people which both sides with their priorities will aim to discuss, negotiate, and seek to ease;

- Public communications and understanding around the relationship must be improved, whether that is in terms of negotiating progress, realistic options for both sides, care with overly-simplistic messaging, or particular terminology with often multiple meanings;

- Despite uncertainty there will be a steady move towards deeper, more robust arrangements, since both UK and EU have strong interests in making these happen, but this will not be a quick or steady process, instead it will come from considerable engagement, flexibility, and patience, to create something that is tolerable if always slightly sub-optimal.

This paper has benefitted from numerous conversations with various experts in UK and EU politics, negotiators on UK-EU and other talks, and officials past and present, to all of whom I owe gratitude.

Introduction

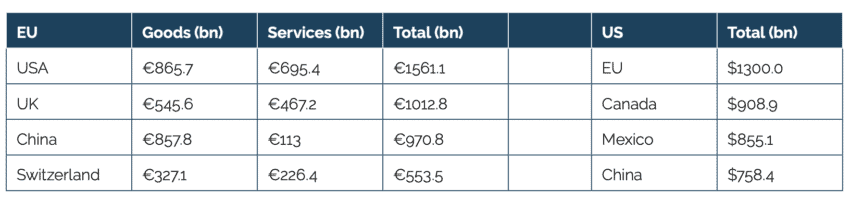

UK-EU relations matter for both sides. Economically, as the UK is the EU’s second largest trade partner, and the EU first for the UK. As neighbours in confronting shared regional challenges such as war in Europe and moving to net-zero. Historically, with the legacy of the UK’s membership.

In the UK, the aftermath of the Brexit referendum of 2016 has been intense, questions of economic impact and the future of Northern Ireland to the fore amidst tumultuous politics seeing six Prime Ministers in just over eight years. While less dramatic in Brussels and across the EU, there have been strong emotions as long-standing ties with the UK need to be reconsidered.

Though key to this story, relationship dynamics and negotiations have received little attention. For once politicians have made their decisions, it is for officials to reconcile their content, experts to advise on feasibility, and stakeholders to seek their influence. That is the prime focus of this paper, considering past and future against ideal third-country negotiations in which broad teams set objectives, test red lines, find common ground, and manage domestic politics. This is of course rather a different model to that of all-powerful lead negotiators assumed by previous UK governments.

Relative size and power always play a part in such negotiations. The UK needed a deal more than the EU, because approximately 48% of its trade was at stake[1] compared to 13%[2]. As will be shown, involvement of two major countries, USA and Japan, added to the pressure on the UK. Nonetheless, this relationship must matter to the EU as probably the world’s second largest trade flow[3].

Figure 1: Top EU and US Trading Partners in 2022 (sources Eurostat and USTR)

Tales of Brexit take many different starting points, and this one uses 2016 in focusing mostly on the immediate past and future. Many prior tales can be debated, for example those suggesting the UK was always special or never a mainstream part of the EU, but ultimately this is just speculation. Likewise, it only considers in passing potentially transformative developments in the future such as a shrinking UK, or dissolved EU. Negotiators should have a wide hinterland of knowledge and views, but mostly focus on the matters at hand to achieve their overall policy goals.

Part 1 of this paper analyses UK-EU negotiations in the period of 2016 to 2024, to understand how we got here and what should be learnt on both sides. Part 2 looks at current relationships and the expectations under a new UK government and European Commission, and Part 3 takes a longer-term view of potential relationship models, and why these will still require extensive negotiation. Throughout, it seeks to reflect the view from both London and Brussels, from the point of view of an informed observer largely but not always on the sidelines of the negotiating process.

[1] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7851/CBP-7851.pdf

[2] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/160/the-european-union-and-its-trade-partners#:~:text=Main%20EU%20trade%20partners&text=In%202023%2C%20the%20United%20States,%25)%20and%20T%C3%BCrkiye%20(4%25).

[3] US figures for 2023 have yet to be published, however the UK remained the EU’s second largest trade partner. Figures indicate different statistical approaches, notably towards services, making exact comparison difficult.

Part 1: The Past

There was, famously, no UK government plan for a vote to leave the EU in 2016. That set the tone for eight years of haphazard and inconsistent handling strongly determined by the characters of those involved. As of 2024, this means that there is no settled way in which the UK political system handles EU relations, whether in Whitehall, Parliament, or for the country. This is a clear political failure.

Calling Brexit handling a success for the EU may however mistake its system clicking into a typical third-country negotiating approach for a UK-specific plan. An orderly withdrawal was achieved, but there have been signs that the rigid approach adopted in doing so is not sustainable for the future. With a reset being discussed, there is value in both sides reflecting and learning.

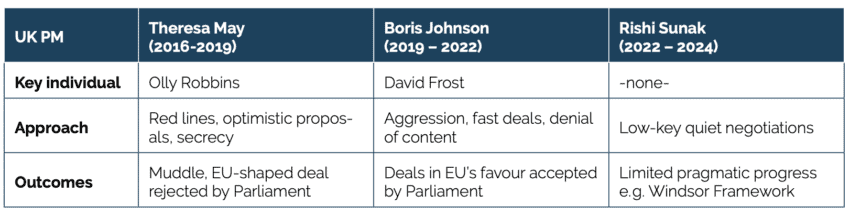

Different UK negotiating approaches since 2016

Centralisation of power allows a UK government to take any approach to negotiation provided it has a working majority in Parliament. Such freedom does not always deliver well considered plans, as has been shown with Brexit negotiating approaches often evidently untested before deployment.

One of Theresa May’s first acts on becoming UK Prime Minister after the referendum was changing Whitehall structures for handling EU matters. Particularly disruptive was breaking up the Europe and Global Issues Secretariat (EGIS) of the Cabinet Office, whose weekly cross-government meeting with the UK Head of Mission in Brussels coordinated the UK’s EU policy. Replacing it with a Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU) headed up by a powerful lead negotiator created significant tension over reporting lines. These were exacerbated by secrecy, a defining characteristic of both May and Olly Robbins as that individual. Neither had a significant EU or international negotiating record.

One mystery of these early days of UK Brexit handling is why officials with deep knowledge of Brussels were excluded. Written accounts of UK Brexit handling[1] typically show only the Permanent Representative in Brussels, Ivan Rogers, fully understanding the new landscape. Undermined by May’s closest advisors, he resigned in January 2017. Such a fate may give a clue, then Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood possibly foresaw that expertise would not be welcomed at a political level. An inexperienced team in a new structure were thus deployed.

UK senior officials were probably complacent, thinking that typically getting their way in Brussels meetings as a large member state meant the same would happen as a third country. Such experience may also have lay behind the longstanding incorrect assumption that appealing to large Member States would help, when third country negotiations are tightly controlled by the European Commission. Problems on the UK side were obvious by June 2017 when the EU’s sequence for Brexit negotiations was agreed, to cover withdrawal issues before a trade agreement.

May’s rather incoherent approach to negotiations that started with strong red lines which she then tried to get round with proposals never acceptable to the EU was rejected by Parliament, her secrecy providing no basis for explaining trade-offs or building support. This was even less surprising given that the Commission more or less had to dictate what they thought an acceptable deal would be in the absence of any serious UK attempt to understand all the negotiating parameters[2] and that it could not continue to have trade free of barriers outside of the EU.

Boris Johnson became Prime Minister in 2019 as a direct result, and took a far more aggressive approach led by negotiator David Frost, who had some Brussels experience. If the aim was simply to “get Brexit done” then this was achieved, both Withdrawal and Trade and Cooperation (TCA) agreements approved by his own party deeply suspicious of the EU. Frequent threats to walk out, claims no deal would be fine, and overt hostility may have been crucial in gaining this support.

This is not least as their content from a UK point of view was inadequate. Johnson denounced both deals soon after agreement as in effect breaking his promise not to erect a goods trade border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Other examples of unsatisfactory details to Brexit supporters included failure to fully take back control of fishing waters, and the most stringent level playing field terms ever included in an EU trade deal when the UK originally wanted none. Businesses meanwhile had to deal with a broad but thin agreement which meant many new barriers.

Performative hostility and miscommunication of content may have been required given unrealistic expectations of what was possible. What this could not bring was a stable relationship when Johnson kept threatening not to implement the agreements. Rishi Sunak inherited this mess in October 2022, and resolving it to a degree was his greatest achievement as Prime Minister, albeit one angering staunch Brexit supporters in his party. The Windsor Framework of February 2023 required patient work by officials, though with most details supplied by the Commission, and is not accepted by a significant element within Northern Ireland. Relations overall were at least stabilised, with UK finally acceding to the Horizon science research program, and working level ties improved from a low base.

Figure 2: Summary of UK approaches to Brexit negotiations

Despite obvious differences there were significant commonalities to UK approaches. Empty threats, a belief proposing text would shape the deal to UK advantage no matter the content, and secrecy preventing broad lasting support were all common. Behind these lay the absence of a realistic shared set of objectives refined through meaningful discussions. This meant no attempt to explain trade-offs, and little meaningful involvement for stakeholders including the businesses who would have to use the agreements. Parliament was treated as an annoyance, as were devolved governments. A more constructive approach would almost certainly have delivered better outcomes in some areas.

Consensus model of EU-Third Country negotiations

Two significant books describing Brexit from the EU point of view[3] stand in contrast to those focused on the UK in describing a calm, orderly process, sometimes in a somewhat smug tone. Certainly, the EU is used to complex negotiations with third countries, indeed at the time of the UK referendum was trying and failing to finalise one with their largest trade partner, the US.

Such understanding, and Michel Barnier’s appointment to lead the process, provided the EU with a significant head start. He understood the English separatist mentality around Brexit as perhaps only a Frenchman could, certainly different to many views in Germany that the UK was simply wrong to vote as it did. He also provided a single political figurehead engaging extensively across the EU to answer questions and build a common position, something the UK never achieved.

Consensus is crucial to considering EU negotiations with third countries. Understanding that many conversations will happen, involving member states, stakeholders, and politicians, the Commission seeks to shape these into a single agreed position through a patient process that includes a formal mandate. Sometimes the Commission encourages third countries to talk directly to member states, but only as a diversionary tactic. Power for third country relations lies in Brussels, and the Commission shaped the Withdrawal Agreement, Trade and Cooperation Agreement, and Windsor Framework, on the basis of the broad agreement on its own side. UK input was possible but limited.

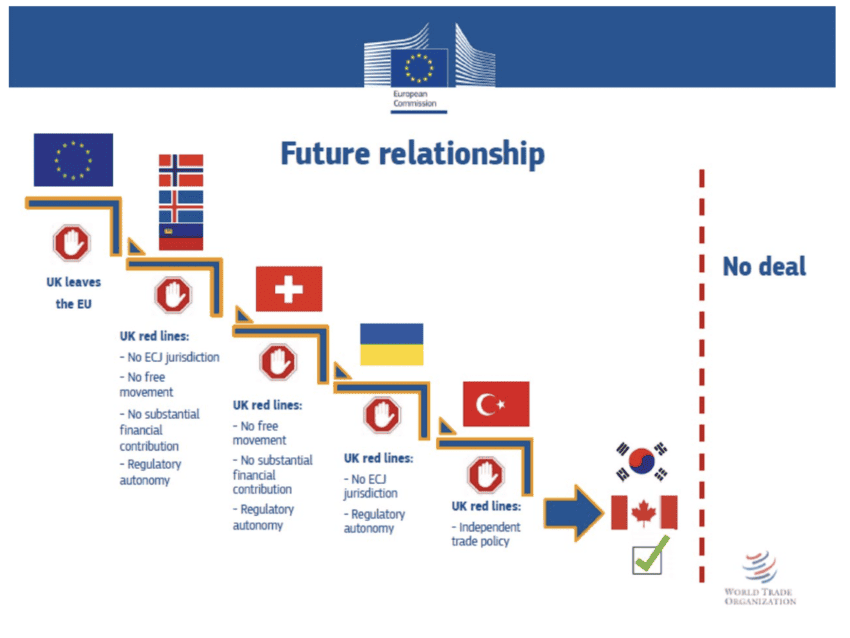

This is the EU’s great strength as a negotiator of third-country relationships, but potentially also a weakness, in prioritising order. For Brexit, it worked for a time, a strategy for withdrawal followed by limited trade deal maintaining as many other EU priorities as possible. UK attempts to undermine or change this were consistently ineffective. In particular, the EU had the constant challenge of demands for trade privileges without accompanying obligations, with a UK media who would take any sign of possible concession as weakness. This meant some rather crude and simplistic messaging which was exemplified by Barnier’s picture of the options for the future relationship.

Figure 3: The Barnier ‘waterfall’ In reality this ‘waterfall’ model is a poor fit to a relationship with a major neighbour. For the EU has multiple agreements with many third countries, especially for major trade partners, notwithstanding the institutional dislike of the “Swiss-style” approach this suggests. EU protection of its single market or resistance to cherry picking is similarly rather variable in practice. Seeking a single unchanging agreement worked fine initially, but the ambiguous trading situation of Northern Ireland was not a good fit, similarly the territorial issues around Gibraltar.

In reality this ‘waterfall’ model is a poor fit to a relationship with a major neighbour. For the EU has multiple agreements with many third countries, especially for major trade partners, notwithstanding the institutional dislike of the “Swiss-style” approach this suggests. EU protection of its single market or resistance to cherry picking is similarly rather variable in practice. Seeking a single unchanging agreement worked fine initially, but the ambiguous trading situation of Northern Ireland was not a good fit, similarly the territorial issues around Gibraltar.

Where the UK has failed to come to terms with the implications of Brexit for trade, the Commission has struggled for a model to manage the complexity and dynamism of the UK relationship going forward. In an early Brexit success story, the UK stayed as part of the European standardisation framework, and building on this by joining regulatory bodies wouldn’t obviously sit within the TCA. Similarly, joint industry demands to extend generous rules of origin provisions related to e-vehicles caused some problems to the EU in how this should be formalised. A rethink may be required.

Not just about the governments

Modern negotiations do not just take place in anonymous meeting rooms between government officials. This is particularly the case for a relationship between neighbours as large and closely intertwined as the UK and EU. Business associations, think-tanks, parliamentarians, media, and politicians and officials from different administrations constantly engage with both sides.

As described above, while the EU follow this wider debate and build it into their wider consensus, the UK has seen it as an inconvenience to be ignored. At times such a UK approach has taken on slightly surreal qualities, for example in 2018 when UK proposals for novel customs approaches were being debunked by informal meetings of specialists, sometimes including officials working on them. Meanwhile an opportunity was largely lost, for where stakeholders on both sides apply joint pressure there is evidence that this has made a difference, for example on standardisation and e-vehicles.

Third countries also played significant roles quite unexpected at the start of the process. While a UK-US trade deal was a clear goal for many Brexit supporters, bipartisan Washington support for the Northern Ireland peace process proved to be the higher US priority. Far from the UK moving towards US regulatory norms, there was actually pressure to avoid a border on the island of Ireland, meaning the UK sticking closer to EU regulations. No UK government could easily ignore this, not least when US companies based in the UK also emphasised EU ties as the priority. All of which counted as a triumph for Ireland’s diplomatic efforts with the US, its own preparations[4], and the EU backing them.

Japan’s involvement in UK-EU negotiations was even more of a surprise. Soon after the referendum its government signalled to the UK that investment from companies such as Nissan was based on the expectation of continued access to the EU single market. With Nissan being a symbolic manufacturer in the leave voting north-east of England, this meant little chance of the UK leaving the EU with no deal. This was well understood by EU negotiators, who were thus able to call the bluff of UK leaders saying otherwise.

That was not the end of Japan’s Brexit engagement. Considerable support was offered in UK accession to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in the view this would ensure continued adherence to international trade norms. Repeated threats to breach treaty commitments with regard to Northern Ireland were considered a major obstacle, not least with China having also applied to join. Concerted efforts to make sure the UK government understood the linkage at the highest level were eventually successful, the Sunak administration dropping the threat and signing the Windsor Framework one week, and confirming accession to CPTPP the next.

Such situations are unlikely to be repeated in the same form. There is however a strong lesson to a UK government that negotiations particularly of major relationships involve many players, and that this needs to be factored into a cohesive and far more publicly engaged approach than has been seen to date.

[1] Chris Cook “Defeated by Brexit”, Tim Shipman “Fall Out” and “No Way Out”, Peter Foster “What went wrong with Brexit”

[2] In particular that an FTA model didn’t work for Northern Ireland – see https://ecipe.org/publications/fresh-thinking-on-northern-ireland-and-brexit/

[3] Lead negotiator Michel Barnier’s “My Secret Brexit Diary” and “Inside the Deal” by one of his deputies Stefaan de Rynck

[4] See “Brexit & Ireland” by Tony Connolly

Part 2: The Present

Brexit in the UK, from calling the referendum to struggles in negotiations, was predominantly about a Conservative Party increasingly hostile to the EU. By contrast the Labour government elected in July 2024 sees the EU positively, and most of its support would like closer ties. An immediate change was new UK Cabinet Ministers contacting their Commission counterparts in a way predecessors had not.

Then again, UK politics remains an issue even in seeking a reset, red lines on not rejoining single market, customs union, or accepting freedom of movement are designed to reassure leave voters. These together with existing agreements are the starting point. From an EU point of view, a new Commission searching for both protection and growth may see engagement with the UK as helpful, though cautiously given painful previous experience and its own red lines. Mis-steps from mutual suspicion are inevitable and have already happened to a degree, so strengthening political structures is an early priority. These will in turn need to make sense of a scope almost too wide to comprehend.

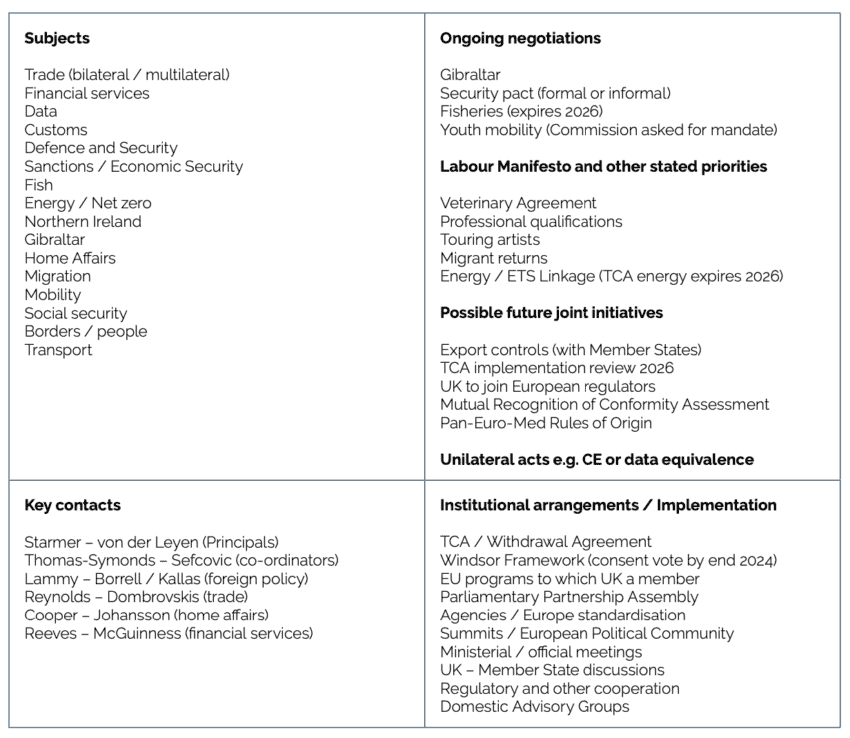

The unmanageable negotiation?

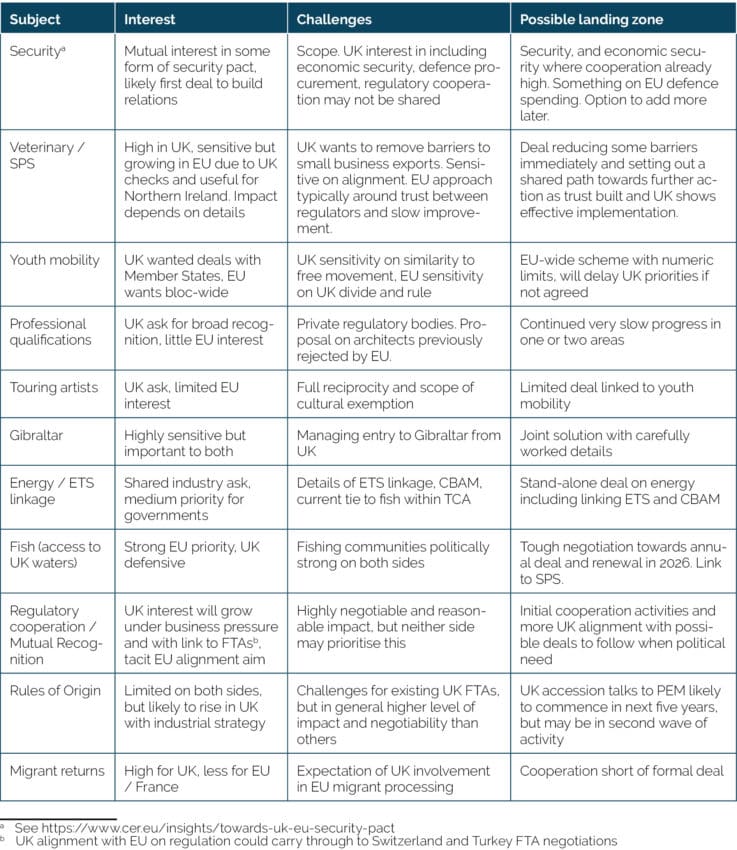

In the rush that was establishing post-Brexit arrangements the breadth and depth of the UK-EU relationship was downplayed. As new UK Ministers contact EU counterparts, its full scale becomes clearer. There are numerous topics of shared interest, existing agreements to implement, talks under way such as on Gibraltar, and various relevant unilateral activities. Topics below cover main areas but there is no definitive publicly agreed list – jointly agreeing this would be useful.

Figure 4: Scoping the UK-EU relationship This sprawl of UK-EU subjects is a combination of a number of factors:

This sprawl of UK-EU subjects is a combination of a number of factors:

- Most geographically integrated EU neighbour apart from Switzerland

- World’s second largest trade flow, the EU’s economically most significant neighbour

- UK’s previous EU membership leaving strong legacy in law, people, expectations

- Nature of modern trade covering so many different issues and regulations

Managing such a broad range of topics would be challenging enough, but various linkages make this even tougher. Some are historic, such as the UK not obtaining greater EU market access than countries with greater alignment, on which other neighbours keep a close eye, or the entanglement of energy and fish in the TCA. Others will become issues as both sides seek to pursue their interests, such as ties between mobility demands of both parties, UK aims to expand security talks into wider areas, and specific ties such as between youth mobility and any UK return to the Erasmus student program. Meanwhile, some issues such as energy would be almost certainly better served by a discrete negotiation between experts untethered from wider aims at balanced negotiations.

With the return of EU-coordination to the UK Cabinet Office, the two sides should have similar structures with a political lead seeking to shape and implement the relationship. These teams cannot however control everything, there is too much ground to cover, and this would block the specialists deepening their own engagements. Similarly, subjects are too many and varied, and likely to proceed at different speeds, to make for a pure single undertaking negotiation.

Given history and complexity, building suitable trust across the relationship is essential and should start from the top with a regular schedule of summits. From the first of these would usefully come an agreement on structure, coordination and joint working. In particular both sides should be agreeing to take the requests of each other seriously, and work together on appropriate consultation and briefing of the media and stakeholders. Jointly managing public expectations is a sign of the best negotiations but has so far been seen to be counter-cultural to the UK in particular.

Both sides have challenges to show flexibility and set suitable expectations, for the UK that it cannot fully take back control or ignore EU asks, for the EU that this will be an evolving relationship with variable structures necessitating flexible mandates. For both, that implementation of existing agreements is crucial, and mutual appreciation of constraints and understanding of the possible also important. There will be negotiations, unilateral actions, meetings between officials, stakeholder discussions, all forming an integral part of the picture. One could envisage the lead official on each side speaking weekly to share understanding of what is happening, such is the scale of activity.

Some agreement on the role of EU Member States and UK devolved governments would also be useful. While international relations are clearly UK and EU competences, discussing the broad relationship in particular with lower-level governments must be allowed, not least given they have specific interests. In the case of EU member states these include security, export controls, trade promotion, and specific shared interests such as North Sea energy, for UK devolved government this includes agriculture and fishing. Engagement should be seen as entirely natural, indeed part of the ongoing work of shaping the overall relationship along with all stakeholders.

Closeness in arrangements should not be mistaken for either side abandoning core asks or red lines. Similarly, the UK cannot expect special favours from the EU and just asking for them tends to lead to a bad reaction because of past experience. Nor are individual moves ever likely to be economic game-changers for either. Reaching the stage of mature ongoing cooperation suggested above is of course challenging in all major relationships, and will require initially some leap of faith followed over time by the sustained delivery of positive outcomes. This is of course far from guaranteed.

Rebuilding relations after divorce

Focus on the practical asks that both the UK and EU have in their ongoing relationship will not obscure the rawness of recent events best seen as divorce and bitter aftermath. This affects both sides, but with a large amount of denial, and no therapists in international relations.

From an EU point of view, the UK left the club and bad-mouthed it extensively on the way out, while also wanting untouched trading privileges. This has inevitably left resentment and a view among many that rebuilding simply shouldn’t be any sort of priority. This is not however a uniform view, there are anglophiles in the institutions who miss the UK, others who believe that the UK made a mistake it should be helped to correct, and another category who simply want to move on particularly given the changed circumstances after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Such EU splits are rather less commented upon than those in the UK, where the tensions between those holding pro and anti-EU positions has eased only marginally. Although opinion polls suggest a majority of the public would vote to rejoin the EU, printed media remains largely hostile, as currently does a Conservative Party that will one day return to power. There are particular areas of concern including anything that resembles freedom of movement, automatically following EU rules, or the European Court of Justice deciding on disputes.

More generally, the instability of the entire Brexit process caused a great deal of evident political trauma to a UK public unused to this, leading to an understandable desire among most politicians not to allow this to happen again. This links to a desire to treat the matter as closed, lest there be any risk of repeat. This enhances instincts to secrecy in Whitehall, but these caused some of these problems originally and greater openness will be the better basis for the reset.

Notwithstanding such sensitivities, the red lines of both sides do seem to leave space for agreement, for example that alignment would be by discussion and the ECJ only the final point for understanding of EU law. In the past reaching such a point was made difficult by a hostile environment, and scarring will continue to be an issue. There may be exacerbated by a certain aspect of cakeism on both sides, such as the EU expecting exemptions from UK charges for example regarding mobility or veterinary inspections, while many in the UK still don’t understand why there are now barriers.

Moving on from the divorce emotions would be an important function of regular summits. Another opportunity may be provided by Poland’s Presidency of the EU in the first half of 2025, as a Member State that particularly seeks closer relations with the UK. A Presidency has little more than agenda-setting powers, but using them to discuss more fully how to move on from the past could be a rare example of good timing in the Brexit saga.

EU-Labour Party negotiations effectively started in July 2022

While the Conservative Party’s challenge on the EU was balancing hostile backbenchers with the realities of such an important relationship, Labour must manage demands from the party for a closer relationship against respect for events since 2016. Seeking to get ahead of problems, Keir Starmer laid out two years ahead of the election his priorities[1]. What was stated in this July 2022 speech, security, SPS agreement, professional qualifications, and touring artists, became the manifesto.

There are greater ambitions. Broad indication of these came in the work of the UK Trade and Business Commission, whose Blueprint[2] on UK trade was published in June 2023. Chaired by then Labour backbencher Hilary Benn, who had formerly headed up the Parliamentary committee looking at future UK-EU relations, this was a compendium of asks from UK business and civil society mostly EU focused. With Benn returning soon after to the front-bench with responsibility for Northern Ireland, there was some indication that this work was looked upon kindly by the Labour leadership.

These 114 Recommendations sparked interest from those in the Commission preparing for a new UK government, for example in terms of seeing a wider agenda in areas such as regulatory cooperation. Separately the then government had been trying to negotiate youth mobility agreements with selected Member States, and concerns from some of these led to the Commission seeking a common position. This draft mandate revealed in early May 2024 was criticised by Labour, and saying “we’ll listen” might in future be a better approach. Other EU priorities such as security, wider mobility, and regulatory alignment have also been mentioned, not all of which are however considered urgent.

This can all be seen as the early stages of negotiations. Formal talks on any issues will be difficult prior to the full establishment of the new Commission by the end of 2024. This allows some months for planning, in which both sides should be considering the scope of potential deals, respective levels of interest, linkages, and time to completion. Such preparation will be important to success as there are many potential pitfalls in both individual files, and the overall packaging.

Arguably, this time is particularly important for a UK government which has previously overlooked the importance of a semi-public process in setting clear, realistic objectives, and also faces demands from business for unilateral action such as aligning with EU regulations. If the reset is to be substantive it must start with change in Westminster and Whitehall, and a poor start was made when the government decided not to allow Parliament any specific scrutiny of EU policy through a Select Committee. At best it is likely that UK handling will improve only slowly given past experience.

Figure 5: Challenges of individual negotiations

Creating a roadmap to identify how to progress these issues over the lifespan of this government and Commission is likely to be the first part of more formal negotiations. Ideally this should include identifying early harvests such as areas where existing cooperation could be formalised as a way of showing early results. Handling processes for new issues will also be important, for example these could include alignment with healthcare trials, regulatory or advisory bodies which the UK could join, and whether UK audio-visual content counts as ‘European’.

More such matters will be raised once generally better relations make it safe and potentially profitable for stakeholders to do so, indeed some increased activity has already been seen since agreement to the Windsor Framework ended the EU’s prohibition on UK engagement. There is also the review of the implementation of the TCA, once seen as an opportunity in the UK for renegotiation, now more reasonably viewed as a chance for discrete improvements in current deals.

With sufficient goodwill and priorities on both sides there is reason to believe that progress can be made. Nonetheless the scale of the task and the difficulties that have occurred in the past present significant barriers. These have continued, with Labour’s initial failure to hear that the review was not a renegotiation, and more recently their negativity on youth mobility, suggesting to many across the EU that not enough has yet changed in the UK. There is time to find better approaches, but almost certainly the ongoing process of deepening ties will not proceed smoothly.

Global difficulties may help UK / EU relations – a little

One consistently misleading reading of UK-EU relations since 2016 is that of an EU disinterested in building a relationship with the UK, or more recently that it has everything it wants in the TCA. For different reasons both pro and anti-EU campaigners in the UK have stated such views, supported by the Commission’s simplistic messaging and endlessly repeated injunctions against special deals.

UK political debate tends to naïve generalisations about the EU, and there is an opposing one in which the re-election of President Trump forces the UK and EU closer together. Under this scenario, a withdrawal of the US from European defence and global trade requires Brussels to seek allies of which the UK is the obvious one. As per the disinterest claim, there is some truth but it is limited.

Signs that even separated the UK and EU have similar approaches are helpful. This has been the case towards China, despite US pressure, to continue engagement while being cautious, and towards the US, of not following disdainful attitudes towards the WTO and other institutions. One could also see the Brexit vote as a prototype for a pushback against openness since seen in the EU. While some leading Brexiters claimed a vote for global Britain, the reality was that the arguments underpinning the vote were more about immigration. That applies in the EU context, and like the UK the bloc is also struggling to reconcile competitiveness and the net—zero transition.

Open Strategic Autonomy as an EU policy agenda has prioritised the development of new tools like the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and corporate sustainability due diligence as a way of seeking to protect its companies from being undercut. Where this may help the UK is that the EU is struggling to find trading partners who are happy with such an aggressively extra-territorial regulatory approach. In turn there is a distrust inside the bloc to offering significant trade concessions if these could lead to EU production being undercut, even though there is increasing acknowledgment that competitiveness also needs to be a focus.

Though there was at one point a suggestion of a lightly regulated “Singapore-on-Thames” this was never a realistic approach for a UK government facing its own domestic pressures to regulate, and internationally from businesses wanting easier trade from aligned regulations. With Westminster also finding new trade deals harder and less economically rewarding than was suggested during the referendum campaign, there does seem to be an opportunity that in the coming years the UK and EU are ideal partners with roughly aligned approaches that could deliver cooperative competitiveness.

While an absence of alternatives can certainly be useful to building a deeper relationship it should not be seen as decisive. Similarly, EU willingness to listen to UK asks is just good manners in a trade relationship, but reaching a mutually beneficial agreement something entirely different. There’s little chance that the EU will suddenly decide to provide the UK with special deals or make this the priority above all others, not least given some EU concerns about adjoining countries attracting inward investment. At best, the global context is a further incentive for conversations, a driver for politicians always keen to sign international deals. That won’t however change the expectation of the EU that it has to strongly protect its own interests in all third-country negotiations including or maybe even particularly with the UK.

[1] https://labourlist.org/2022/07/a-plan-to-make-brexit-work-keir-starmers-speech-to-the-cer-think-tank/

[2] https://www.tradeandbusiness.uk/blueprint

Part 3: The Future

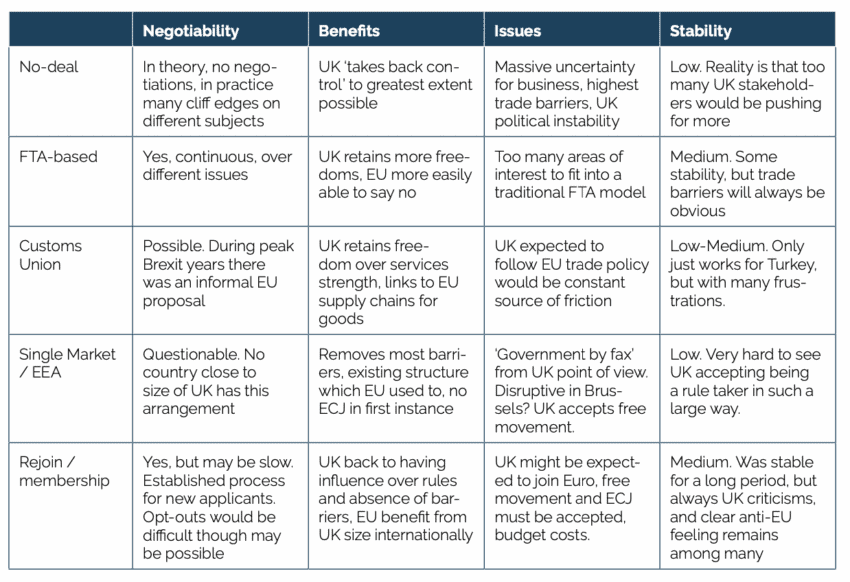

EU membership as an aspiration provides a shared vision for much of the neighbourhood, but that doesn’t currently work for the UK. Even before the referendum there was some debate as to which model of relationship could suit the country best, and this has continued ever since with devotees at all positions between no-deal and membership, often making rather heroic assumptions about what their preferred choice would involve. Without a major change in political and public views, what this means is no clear context for negotiations, or possible shared long-term vision for the relationship.

Equally, for all the chatter, there is little sign of EU developments that might help remain elusive, such as some sort of ‘concentric circles’ model. Such an uncertain future provides another incentive to better working within the current situation, for no easier answer currently exists.

There is no stable UK-EU relationship

Brexit partisans at both ends of the UK debate have their distinct views on a sustainable model of relations, which is a limited deal or none on the leave side, membership on the remain side. This polarisation acts against stability, in that either position would be attacked strongly by the other. Shallow or no-deal approaches will also be seen by business and other stakeholders as inadequate, but membership would reopen controversies such as free movement of people or adopting the Euro.

Middle way options such as joining the single market or customs union require the UK to obviously cede control with little say, which would inevitably cause political difficulties over time. Wanting these trade privileges without the sacrifices is exactly the cakeism that Brussels dislikes intensely. Notwithstanding this, many UK commentators have long believed in the possibility of the UK as part of the single market for goods without joining for services or free movement, sometimes known as the Jersey model. While movement towards this based on an FTA is possible, formalising it has never been a popular idea in Brussels even though it helps resolve Northern Ireland difficulties.

As shown below, there is thus at present no fully stable model, though two that would appear to be the obvious compromise for a split population, one based on a Free Trade Agreement to which further topics were added, or as close to the pre-2016 model as possible, of full membership but with various opt-outs. Politically, somewhere between these probably reflects the balance of UK public opinion, and unless this changes dramatically, it is the likely zone for discussions.

Figure 6: Different UK-EU relationship models EU developments are unlikely to help

EU developments are unlikely to help

Some of those looking at the UK-EU relationship see a possibility for significant change coming from the way the EU may develop or fragment in coming years. Most commonly this comes from the longstanding French suggestion of an EU of concentric circles, in which the UK gains privileges by formally being part of one of the outer rings. In the most plausible version, the EU is unable to accept Ukrainian membership for varying reasons including corruption and budget concerns, but instead opens up a new category of enhanced trade privileges into which that country, Turkey and UK as the largest EU neighbours are able to fit.

While far from impossible, there are formidable barriers. EU Member State agreement to significant changes has become increasingly difficult. If that can’t be achieved then the likeliest fudge would be to argue that the kind of relations that these countries have can already be considered as privileged access, which could perhaps be topped up a little with some new institutional form of consultation without power, perhaps an enhanced tier of the European Political Community. For Ukraine, anything short of membership would however be a crushing disappointment, while ongoing issues between some Member States and Turkey seem unlikely to be resolved any time soon.

European politics is arguably going in the reverse direction. With the cordon sanitaire around populist-nationalist parties weakening, there is some push for the EU to put up barriers including in the neighbourhood, and return powers from Brussels to Member States including over trade. Even if these are also unlikely to pass, some sort of ongoing stalemate in EU development seems plausible. Such a scenario will arguably add difficulty to the UK-EU relationship.

Some in the UK have long seen the EU as likely to fragment, and the results of the 2024 European elections were the latest evidence for their theory. Soon after the Brexit referendum this argument looked rather silly as the UK looked more unstable than the EU, but there may be more grounds now. All unions of states are inherently fragile, and the EU should not be considered exempt. More pertinent though is that populist-nationalist parties are having to become more supportive of EU membership to come close to power, making further fragmentation unlikely in the coming years.

For the last eight years there have been hopes of some dramatic EU development to resolve Brexit problems. For a bloc whose loss of dynamism since expanded membership of the early 2000s has been obvious, this has always seemed to be more wishful thinking than anything serious. That continues to be the case.

Learning to live with uncertainty

There is a natural desire for order in trade and international relations that isn’t just restricted to the EU. Businesses, governments, and other stakeholders all want to be able to plan effectively beyond a couple of years. This is amplified for the UK and EU given recent memories of almost completely seamless trade across the Channel or between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Businesses want to see that returning, particularly the many SMEs who simply cannot afford the normal costs of international trade. Pressure groups want to see the UK match the EU where there are more stringent regulatory approaches, noting this may also work the other way round. With London and Brussels separated by a two-hour Eurostar journey, there will always be two-way exchanges.

Prior to leaving the EU those trains contained many UK officials negotiating different topics with their counterparts from other Member States. What is too rarely considered is that many of the same issues still need to be discussed, but now from the point of view of a third country, neighbour, and significant trade partner. Every regulation adopted or amended by the EU has the potential to affect the UK, and one could argue there is now double the work as every UK measure could also affect trade likewise. Whether it is fishing, data, films, SPS regulations, financial services, Artificial Intelligence, or thousands more topics, crossing a modern regulatory economy with a large neighbourhood relationship inevitably means a huge amount of activity and mutual interest.

Even with the best efforts of everyone involved, such a relationship cannot ever be static. Similarly, it will never be controlled in a single agreement, whether called the Trade and Cooperation Agreement or an Association Agreement, or one negotiation. There can only ever be an evolution of arrangements, a sprawling organic relationship involving a diverse array of players in which the parameters and priorities will be constantly shifting. Many future developments will also require further negotiations not now foreseen, with all of the stresses that this will bring.

Businesses, other stakeholders, politicians, Ministers, Commissioners, have to learn to live with such a situation in which there is no simple answer, where arguments have to be made, coalitions formed, and progress will only ever be incremental. Only in the EU can there be an assumption that trade will be seamless and the details will be worked out later. Outside, there will be barriers until arrangements are made for that to change. This will take up a considerable amount of everyone’s time, but such is the nature of modern international relations and trade.

Expectations must therefore change not just among those most directly involved in both UK and EU. There will be no sweeping one-size-fits-all negotiations. At best there can be a clear signal from both sides that they want to deepen relations. Brexit was far from the end of the process of engagement, and in the cold light of day after recent traumas, all of those with an interest now need to be thinking anew about how best to advance their interests.

Conclusion: There Is No Conclusion to UK-EU Relations – but a Shared Understanding Will Help

Resetting the UK-EU relationship means recognising the reality of many shared interests which will only in exceptional moments of either joining or leaving be contained in a single negotiation. While there is much to learn from recent years, a new approach is therefore needed for the current moment. This isn’t just about moving on from the divorce, modern economies that are interconnected and highly regulated make this a new challenge in the two-thousand-year history of the relationship between the British Isles and European mainland.

A new UK government less institutionally hostile to the EU, while helpful, does not change fundamentals. This is an extensive unbalanced relationship important to both but more to the UK, creating underlying differences, with no simple answers. As a result of these factors, the world’s second largest trade flow is an inevitably diverse relationship reflected in a number of different agreements, a situation likely to continue to varying levels of discomfort for all involved.

What is needed more than anything else is a shared understanding of the situation, the parameters and constraints that apply to both the UK and EU. For this to happen however requires both to be honest about their own situations, of the limitations to control on both sides. Few politicians have wanted to say this in the UK, arguably even fewer across the EU. Until this happens there will always be a somewhat superficial element to the relationship.

Any evolution of attitudes will take time, maybe years, and there must continue to be engagement in this time, given pressing issues. There is considerable room for improvement even without a full agreement of the context. What was previously a negotiation between a government without clear objectives and an EU with a rigid desire for order could usefully see flexibility on both sides in deepening relations. In the first instance, implementing a regular programme of summits supported by senior meetings can provide a shared sense of short-term direction, to be supported by regular dialogue between respective coordinating teams.

As a shared priority, there should be a security deal. Improving joint handling of energy is an obvious neighbourhood priority. Relatively low-hanging fruit such as the UK joining Europe-wide schemes, discussion of multilateral trade objectives, and greater regulatory cooperation should be taken even if considered less important than some other aims. This would leave a more difficult but traditional trade negotiation around mobility of people and reduction of checks on foodstuffs, where progress would probably only be gradual.

There will inevitably be ups and downs, difficulties exposed by media, stakeholders with demands, campaigners wanting to go further, political opposition, all of which are relatively business as usual. Ideally these would be handled in at least semi-public debate, jointly, but that may again take time and will never happen fully. Similarly, the negotiations will be taking place against a backdrop of those debating the broader picture, which again should be considered normal.

Whether the current institutional structure centred on the Trade and Cooperation Agreement will survive for the long-term is impossible to tell. Those arguments will continue. Meanwhile, the best starting point is to enhance that politically and supplemented by specific additions. While improvements will be incremental, at least this will give some confidence in the future path for those whose investment is needed to strengthen the whole European economy, an interest that political leaders must also share.