The Art of the Mini-Deals: The Invisible Part of EU Trade Policy

Published By: Lucian Cernat

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements WTO and Globalisation

Summary

Trade policy is usually defined by the kinds of deals it can strike. Typically, the attention is focussed either on big multilateral trade rounds or on bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs). This policy brief goes beyond the conventional wisdom and sheds light on other trade agreements (trade mini-deals), which so far were less in the focus of EU trade experts and academics. The paper offers a preliminary assessment and a taxonomy of these trade mini-deals. The main takeaway is that there is a lot more going on than what meets the eye when it comes to EU trade policy. In reality, FTAs are just the tip of the trade policy iceberg. When taking a systematic look, it becomes apparent that FTAs are only one of the many trade policy instruments. Apart from FTAs, the EU has signed a much larger number of trade mini-deals that have, potentially, a significant impact on EU trade. The paper concludes with a short assessment of the role such mini-deals could play in the future, given the evolving nature of trade policy objectives and the growing complexity of international trade negotiations.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the European Commission

1. Introduction

In a book[1] that spent several weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, a former US president said: “I like thinking big. I always have. To me it’s very simple: If you’re going to be thinking anyway, you might as well think big.”

Despite this inspirational quote, most of the trade deals pursued by the Trump Administration were not “big deals”. In contrast, most free trade agreements (FTAs) signed by countries around the world – the kind of trade agreements that nowadays capture people’s interest and political attention – are quite big. First, FTAs are big for they cover trade flows worth billions, and “essentially all products”, to use a well-known expression. The best proof for this assertion is that EU bilateral FTAs cover 52% of extra-EU exports (DG TRADE, 2023). Hence, almost by default, FTAs are seen as important trade policy instruments as they eliminate tariffs affecting billions of euro worth of commercial interests. FTAs are a “big deal” also for other reasons beyond tariffs: for instance, if and when they open up new market access for services. Furthermore, FTAs cover many important areas such as sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, technical barriers to trade (TBTs), intellectual property rights (IPR) and public procurement. The red thread linking all these areas in an FTA is the overarching objective of trade facilitation and reduction in trade costs. Hence, FTAs are central to the widely accepted view of current global trade relations, governed essentially by multilateral rules established at the WTO and complemented by a large (and growing) number of FTAs.

This paper goes beyond the conventional wisdom and sheds light on other trade agreements (trade mini-deals), which so far were less in the focus of EU trade experts and academics. The paper offers a first, preliminary assessment and a taxonomy of these mini-deals. The main takeaway is that there is a lot more going on than what meets the eye when it comes to EU trade policy. In reality, FTAs are just the tip of the trade policy iceberg. When taking a systematic look, it becomes apparent that FTAs are only one of the many trade policy instruments. Beyond FTAs, the EU has signed a much larger number of trade mini-deals that have, potentially, a significant impact on EU trade. A corollary of this proposition is that, over time, the cumulative impact of these mini-deals may be very significant. The paper concludes with a short assessment of the role such mini-deals could play in the future, given the evolving nature of trade policy objectives and the growing complexity of international trade negotiations.

[1] Trump, D J. J. and Schwartz, T. (1987). Trump: The Art of the Deal Random House.

2. EU Trade Mini-Deals: The Invisible Commercial Policy

For decades, the EU common commercial policy has been at the heart of the European integration, a key example of a policy area in which internal and external policies are inextricably linked and where EU integration greatly enhanced the economic welfare and global role of EU Member States. The EU common commercial policy typically refers to the collective set of international initiatives and policy actions that directly affect international trade in goods and services, the commercial aspects of intellectual property, public procurement, and foreign direct investments (FDIs). The expansion of international trade made the common commercial policy into one of the Union’s most important policies. Essentially, every measure concerning trade with third countries, as well as every measure intended to influence trade flows and trade volumes, can be seen as part of EU trade policy.

Given this large and complex trade landscape, one would expect the toolbox available to policy makers to reflect such diversity. At first sight, the answer to this question would point only to the main types of trade policy instruments that typically capture the headlines, such as multilateral negotiations, WTO litigation, FTA negotiations or anti-dumping measures. However, when looking at all the existing legal instruments that the EU has concluded with third countries and which fall in the remit of trade policy, the picture becomes more nuanced.

One way to map all the existing instruments in the EU trade policy toolbox is to “follow the paper trail”. In principle, any instrument that has legal implications and involves third countries would be published in the EU Official Journal (EUR-LEX). The search tool in EUR-LEX allows for filtering based on several criteria, one of them based on the policy areas to which the legal instruments belong. A EUR-LEX search query for all trade-related instruments that have been published over the years returned over 2000 entries. Many of these were trade mini-deals covering certain specific elements of EU trade policy. For instance, there are around 200 entries (exchange of letters and decisions of bodies established under existing agreements) pertaining to “origin of goods”. There are also over 400 mini-deals related to technical barriers to trade.

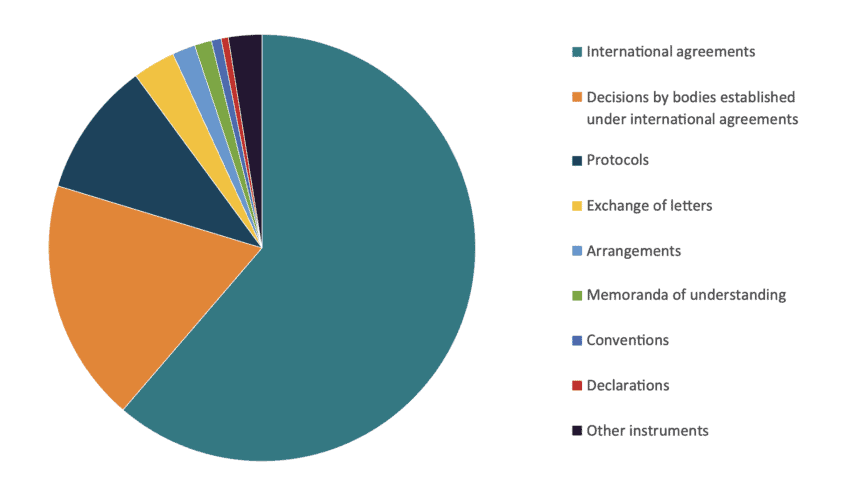

Other agreements are related to specific agricultural commodities (e.g., beef, wine, organic products) or certain SPS measures. There are also mini-deals concerning sustainable trade (e.g., bilateral voluntary agreements on sustainable timber), or trade in industrial products, such as mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) on conformity assessment, agreements on hazardous chemicals, narcotics, waste, etc. The main types of such trade mini-deals are presented in Figure 1.

While the category defined as “international agreements” is rather obscure, and possibly quite eclectic and inflated by various types of documents (e.g., an agreement may have been amended, or accompanied by a notice to stakeholders), the taxonomy indicates a diverse set of instruments that have been used over time as part of EU trade policy.

FIGURE 1: EU Trade Mini-Deals: A Taxonomy

Source: Author’s calculations based on EUR-LEX database.

One caveat that applies to this analysis is that the EUR-LEX search functionalities are not well suited for a more advanced assessment. As mentioned, the actual number of mini-deals falling under “international agreements” is quite likely to be an inflated number. At the same time, there can be other relevant mini-deals covering several policies classified under a different policy area than common commercial policy, despite them having important trade effects. On the other hand, due to their non-binding characteristics or limited administrative nature, some trade mini-deals are probably flying below the “radar screen” and are not even published in the Official Journal.

Despite these limitations, it is safe to assume that the order of magnitude remains valid: the EU has generated hundreds of mini-deals that affect different aspects of EU trade policy. When comparing the extent of such activity to the number of FTAs, the overall picture is quite telling. Figure 2 shows that the number of mini-deals is huge, compared to the number of FTAs currently in force. While it is true that the scope and the legal nature of mini-deals vary considerably and fall short of the deep and comprehensive nature of modern FTAs signed by the EU with over 40 countries around the world, this does not necessarily mean that the cumulative scope of mini-deals (both in number of issues covered and countries that are signatories to such mini-deals) is less impressive.

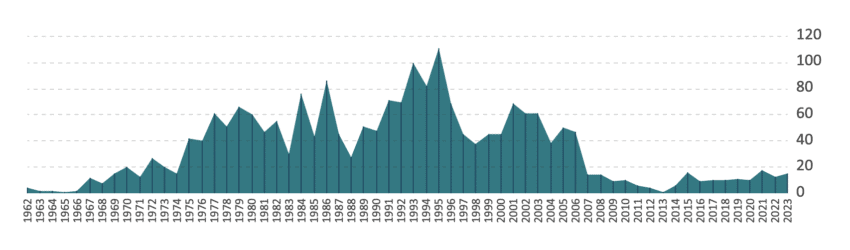

When looking at the number of instruments concluded over time (see Figure 3), the EUR-LEX records suggests that the art of the trade deals (big or small) was at its best a few decades ago. Compared to the mid-1980s, the 1990s and even the early 2000s, we are nowadays at one of the lowest points in terms of number of trade deals concluded, regardless of their size, scope, and type. Even though the “golden age” of trade deals seems to be behind us, every year more than a dozen of mini-deals are still being enacted. Several FTAs are also in the process of being concluded and ratified (e.g., EU-New Zealand, EU-Mercosur, EU-Mexico, EU-Chile, EU-Australia, to name just a few).

FIGURE 2: FTAs vs Mini-Deals: Comparing the Numbers

Source: Author’s calculations based on EUR-LEX database.

FIGURE 3: The Evolution of Trade Agreements Over Time, All Types

Source: Author’s calculations based on EUR-LEX database.

The EU is not the only trading partner using such trade mini-deals. Kathleen Claussen (2022) analysed a large number of mini-deals negotiated by the United States with a wide range of trading partners. She argues that such mini-deals (many of which are not even easily publicly available) have become a prominent fixture of US trade policy making. The US has more than 1,200 such trade mini-deals that govern the trade in goods and services between the US and some 130 countries. Such mini-deals have become the principal tool for trade policy making in the Biden Administration, given the US reluctance to engage in “big deals”. Claussen also argues that the US appears to skilfully combine the mini-deals with existing FTAs. For instance, a side letter changed the NAFTA formula determining how much sugar Mexican exporters could export to the United States, and effectively increased the amount US producers could sell. This is not an isolated example. Trade mini-deals have been used in conjunction with many FTAs (e.g., the US-Peru FTA has six side letters, and the U.S.-Singapore FTA has 18 mini-deals attached to it). The US has also negotiated such mini-deals with the EU, e.g., a Mutual Recognition Agreement on conformity assessment for industrial products[1], an agreement with the EU regarding mutual recognition of product labels on energy efficiency[2], by now expired, and MoUs with many EU Member States to facilitate reciprocal access to defence procurement and to waive customs duties on imports under such procurement contracts.

[1] The Agreement on mutual recognition between the European Community and the United States of America covers telecommunication equipment, electromagnetic compatibility, electrical safety, recreational craft, pharmaceutical good manufacturing practices and medical devices. Available online at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:21999A0204(01)

[2] Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the European Community on the coordination of energy efficiency labelling programmes for office equipment, available online at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2013:063:FULL

3. On the Economic Importance of Mini-Deals

So far, we have seen that mini-deals are a very diverse and prolific instrument in the legal ecosystem. However, quantity (the number of mini-deals negotiated) does not represent either quality or content. At one extreme, some mini-deals are purely administrative, procedural paperwork, with no impact whatsoever on the real world. At the other extreme, some mini-deals contain crucial provisions for thousands of EU exporters and importers, affecting billions of euros of trade flows. Think of the EU-US Organic Equivalency Arrangement. This “mini-deal” confers US farmers the right to affix the official EU organic logo on their products, whenever their products are in compliance with EU legal requirements for organic products, following specific provisions and procedures stipulated in that Arrangement.

One special category that illustrates this paradox of mini-deals being, in fact, quite big trade deals are the Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs). Unlike FTAs, MRAs are mini-deals specifically designed to cut the unnecessary costs of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) to trade. It does not come as a surprise that mini-deals aiming to reduce red tape and duplication of regulatory compliance costs are a priority for businesses engaged in global supply chains and are high on the trade policy agenda. Let us take the example of the EU-Japan MRA on conformity assessment. This MRA confers EU exporters the right to place products on the market in Japan based on a conformity certificate guaranteeing that the EU product complies with relevant Japanese laws and product regulations. The MRA allows for such certificates to be issued by accredited EU conformity assessment laboratories, without the need for EU products to undergo further testing and certification in Japan. Hence, the MRA offers significant trade costs reductions, without reducing the safety and quality controls applicable to imported products. The economic literature offers robust estimates of the resulting trade gains. Different empirical econometric estimates agree that the existence of an MRA tend to increase the value of exports by 15-40% and the probability of firms to export new products to new markets by up to 50% (Baller, 2007 and Cernat, 2022).

Such trade facilitation arrangements are crucial nowadays for exporting firms, notably SMEs. Trade flows have evolved over time and become increasingly intricate, with countless components crossing multiple borders at different stages of production along global supply chains before reaching the final consumer. While trade flows today face historically low tariffs, NTBs have proliferated. A lack of regulatory cooperation is typically a primary source of NTBs. While regulations play an important role in addressing public policy objectives, such as consumer safety or environmental protection, they may differ from one country to another. Companies and products engaged in complex global supply chains therefore need to comply with a whole range of different national administrative and technical requirements, including testing and certification obligations, which can become an unnecessarily costly trade barrier for millions of exporters. EU exporters offered clear examples of such barriers, as part of a pan-European business survey (European Commission and UNITC, 2016).

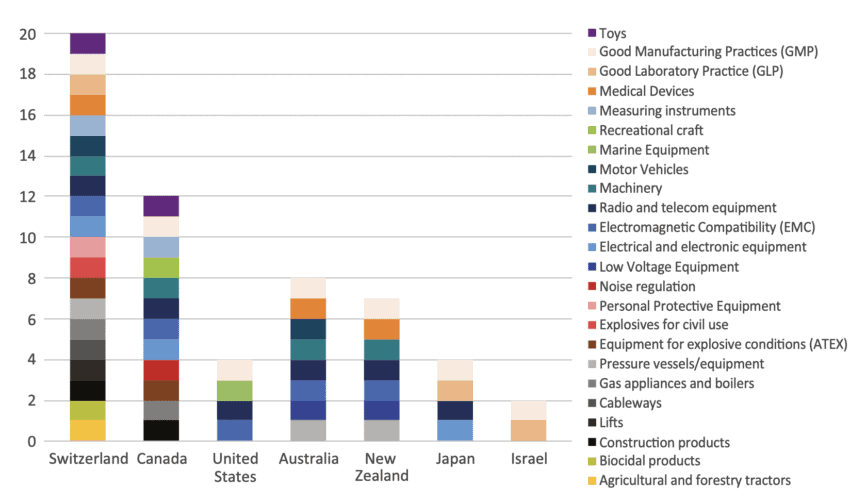

FIGURE 4: Existing Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs): Sectoral Coverage

Source: Author’s compilation based on the legal texts of MRAs.

Given the wide diversity of mini-deals (ranging from simple, administrative exchange of letters to sectoral mini-deals like MRAs), it is difficult to assess their individual economic relevance. Since mini-deals are not commensurate in what they do neither among themselves, nor vis-a-vis FTAs, it is also equally difficult to assess their cumulative economic importance.

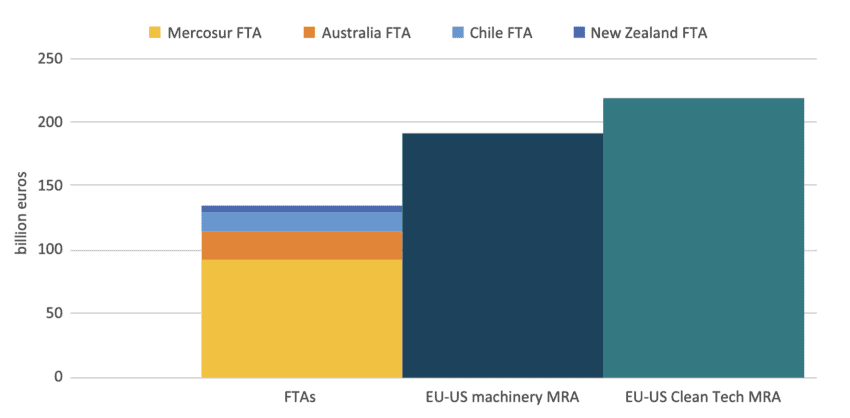

To offer a point of comparison, let us put in perspective the liberalisation potential of several FTAs and two trade mini-deal proposals currently under discussion at the Trade and Technology Council.[1] These proposals aim at the expansion of the existing EU-US Mutual Recognition Agreement to machinery and cleantech products that would reduce certification costs (which are typically higher than existing tariffs in the EU and US on these products). The comparison of trade flows affected by FTAs and these two proposed mini-deals is quite stark: when looking at the trade flows at stake, sometimes mini-deals could become “big deals” (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5: Bilateral Trade Value Subject to Trade Cost Reductions

Source: Author’s calculations based on Eurostat. The FTA trade data (imports and exports) excludes MFN duty-free trade for the EU and its trading partners. The US MRA on machinery covers bilateral trade under HS chapters 84 and 85. The trade flows potentially covered under a Cleantech MRA is based on the proposals for environmental goods that were submitted by participating WTO members during the Environment Goods Agreement negotiations.

While FTAs cover “substantially all trade” and eliminate MFN tariffs, not all their provisions provide for a direct cost reduction for exporters and importers. In the case of the EU and of many trading partners, a significant share of trade is already MFN duty-free. For instance, over 60% of New Zealand imports are already MFN duty-free, even before the conclusion of the EU-New Zealand FTA. In the case of Australia, the share of MFN duty-free trade is even higher (76%). Similarly, the EU also has over 30% of its imports coming under MFN duty-free tariffs. Hence, for those MFN duty-free products, the FTA will not remove any tariffs, neither in Europe nor in those export markets. When accounting for this MFN duty-free trade, the tariff removal value of those FTAs is therefore more limited.

Moreover, these days, average tariffs can be significantly lower than the cost that NTBs mini-deals could reduce. For instance, the average tariffs in New Zealand and Australia are below 2%, in Chile they are around 6% and in Mercosur tariffs are in the range of 8%. The cost arising from conformity assessment in the EU and in the US that an MRA could reduce was estimated to be in double digits, depending on the products (Felbermayr and Larch, 2013). Of course, FTAs achieve more than tariff reductions. However, it is uncommon for FTAs to change existing legislation in their signatories and therefore many FTA provisions are an “insurance policy” that bind a government to pursue policies already in place. This is important for future legal certainty among governments, but it does not lead to a direct and measurable trade cost reduction for exporting and importing companies since they do not change anything in the current rules. Instead, reducing current trade costs is usually what matters most for individual firms engaged in international trade. At the end of the day, countries do not trade, firms do.

[1] For instance, the Joint Trade and Technology Council Statement of May 2023 indicates that the European Union and the United States are working to facilitate conformity assessment across a range of sectors, such as machinery, and goods that can help promote the green transition. (European Commission, 2023a).

4. If Some Past Trade Mini-Deals Are Important, What to Expect in the Future?

The few metrics presented in the previous sections indicated that, while most mini-deals are invisible, some of them might be quite important in terms of trade impact. This raises several questions: are these mini-deals well-positioned on the EU trade policy radar screen? Are there any blind spots? Can we distil some best practices or new ideas for future trade policy initiatives?

The answer to the first question is, yes. There are several recent examples of trade mini-deals dealing with many trade issues that are essential for EU policy objectives and for the functioning of global supply chains. One of them is the recently signed Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership on Sustainable Raw Materials Value Chains between the EU and Argentina (European Commission, 2023b). The European Commission is also deploying a new set of digital partnerships with several trading partners. The first one with Japan has been already concluded in 2022 (European Commission, 2022). These important trade policy objectives, enabling the competitiveness of EU companies in key sectors (e.g. critical raw materials, clean tech, digital, biotech, etc.) and the importance of resilient global supply chains have been recently reiterated by President Von der Leyen in the 2023 State of the Union speech.

Moving to the second question, the answer is also “probably, yes”. Three possible areas for improvement offer promising trade enhancing opportunities. The first, and most obvious one, is to ensure that the existing trade mini-deals are updated and function well. Some mini-deals have a built-in “expiry date” and a renewal mechanism. If the renewal mechanism is not activated, the mini-deal is no longer valid. Such an example is the EU-US agreement on the mutual recognition of product labels on energy efficiency, which has already expired. Another way in which mini-deals become obsolete is by failing to keep up with the revisions of the legislation underpinning their functioning. Whenever a party adopts a new piece of legislation that is not clearly or explicitly included in the scope of the mini-deal, that reduce the scope of the mini-deal. Several sectoral annexes of existing EU MRAs currently fall into that category. Ensuring a proper MRA governance (e.g. annual meetings of the joint committees, regular updates of their legal scope, etc.) is therefore essential for these mini-deals to deliver their expected benefits.

The second area of improvement is related to the uneven coverage of existing MRAs. As can be seen from Figure 4, the sectoral coverage of existing MRAs is very uneven. So, one possibility that could be explored would be to extend the existing mini-deals and ensure a more consistent sectoral coverage across trusted partners that fulfil the requirements for such a regulatory cooperation and engagement. The existing EU-US MRA, given its very limited sectoral scope compared to the large transatlantic trade, would appear as a prime candidate.

The third area that looks promising is to ensure that 21st century regulatory challenges are adequately addressed in the scope of mini-deals. Recent surveys indicate that there is a “business case” for mini-deals (MRAs, MoUs, etc.) in areas where domestic developments across the globe lead to new regulatory requirements. In the area of digital standards, cybersecurity, 5G, interoperability of electronic invoices and other topics related to the digital transformation, there are important regulatory developments not only in the EU, but in many important trade partners. Similarly, there is a global trend to introduce new “green” legislation that would regulate cleantech, energy efficiency, use of renewable energies, or sustainable supply chains. For instance, WTO members have notified via the ePing platform over 7000 legislative acts worldwide that have environmental concerns among their objectives. A fivefold increase in the last decade. This creates a new set of trade challenges for new non-tariff barriers if regulators around the world think in isolation. At the same time, these new developments clearly illustrate the need for transparency (Cernat, 2023) and stronger global regulatory cooperation, that is best framed by the kind of formal arrangements offered by mini-deals.

Another opportunity is to forge greater synergies between FTAs and other trade mini-deals to ensure that they work in tandem, and to expand the trade facilitation opportunities at bilateral level. Exploring greater synergies between “big deals” and mini-deals might be worthwhile. Despite their potential impact, most mini-deals rarely become newsworthy. When not ignored, mini-deals trigger ambivalent views. They are neither widely praised nor are they controversial. So far, one thing is clear: mini-deals are faster to conclude than “big deals” and, if well negotiated and calibrated, they can have a tangible trade impact.

To conclude, trade policy in Europe and elsewhere relies not only on “big” trade deals (FTAs) but also a plethora of mini-deals that address tangible barriers affecting trade flows of different goods and services, from tomatoes to industrial equipment or cleantech. While multilateralism and FTAs are here to stay and provide the main building blocks that underpin the global trading system, there may be valuable lessons to be learned from the existing successful mini-deals. The lyrics of a famous song by Rolling Stones are very fitting for the role mini-deals can play, in a modern trade policy toolbox: “you can’t always get what you want”. But, “if you try sometimes, well, you might find you get what you need”.

References

Baller, S. (2007). Trade effects of regional standards liberalisation: a heterogeneous firms approach. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4124, February 2007.

Cernat, L. (2022). How Important are Mutual Recognition Agreements for Trade Facilitation? European Centre for International Political Economy, December 2022.

Cernat, L. (2023). How valuable is WTO transparency: the 15 trillion dollar question. European Centre for International Political Economy, June 2023.

Claussen, K. (2022). Trade’s mini-deals. Virginia Journal of International Law, 62(2), 315-382.

DG TRADE (2023). Annual Activity Report 2022, Directorate General for Trade, European Commission. Available online at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/annual-activity-report-2022-trade_en

European Commission and UNITC (2016). Navigating Non-Tariff Measures: Insights from a Business Survey in the European Union. Brussels and Geneva.

European Commission (2022). Japan-EU Digital Partnership. Available online at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/56091/%E6%9C%80%E7%B5%82%E7%89%88-jp-eu-digital-partnership-clean-final-docx.pdf

European Commission (2023a). Joint Statement EU-US Trade and Technology Council of 31 May 2023 in Lulea, Sweden. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_23_2992

European Commission (2023b). Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership on Sustainable Raw Materials Value Chains between the EU and Argentina. Available online at: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-07/MoU_EU_Argentina_20230613.pdf

Felbermayr, G. and M. Larch (2013). The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP): Potentials, Problems and Perspectives. CESifo Forum 14(2), 49-60. Ifo Institute, Munich. Available online at: https://www.cesifo.org/DocDL/forum2-13-special3.pdf