Merger Policy, Competition and Innovation Leadership: Implications for the UK’s Investment Attractiveness

Published By: Matthias Bauer Oscar du Roy Vanika Sharma

Subjects: Digital Economy UK Project

Summary

The UK’s competition regulator has adopted hard-sitting views in its assessment of transnational mergers and acquisitions. Since 2019, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has blocked a historic 59% of all mergers that were under investigation, which is double compared to the previous five years. With increased competence to set conduct requirements for large technology companies, aggressive enforcement by the CMA risks undermining Britain’s ambitions to become a leader in global trade, technology, and innovation.[1]

Acquisitions in the technology sector have increasingly been scrutinised by competition authorities over the past decade, often based on the hypothesis that transactions involving large multinational companies tend to be anti-competitive. Authorities’ concerns are based on theories about post-acquisition market structures and the impacts of “killer acquisitions”. While their theories lack empirical justification, competition authorities have increasingly quoted them to assess cases through an ideological lens. Indeed, investigations into acquisitions show that competition authorities can come to markedly distinct conclusions when assessing the impacts on competition over time, especially in technology-intensive industries. The premise that acquisitions of small rivals by large tech companies inherently result in decreased competition lacks solid empirical evidence.

Competition authorities often fail to adequately consider efficiency criteria and the resultant benefits for consumers. The proposed acquisition of Activision Blizzard, a video game maker, by Microsoft is a case in point. The UK CMA had initially found that the acquisition would reduce competition in gaming markets. EU and US competition regulators, by contrast, have cleared the transaction, highlighting the uncertain nature of merger review results for international transactions.

Large multinational technology companies are major sources of innovation and productivity growth. The services they provide are increasingly pervasive across developed market economies, promising large productivity gains. Small, medium, and young companies in high-tech sectors are also important sources of innovation and productivity growth and, therefore, major targets for investment. Ideologically charged competition enforcement would have a negative impact on the UK’s investment attractiveness. The prospect of an innovative and commercially successful company being taken over by another company is an important precondition for investors to make early-stage and continued seed capital investments. Acquisitions also play an important role in driving investments in business growth and internationalisation. By contrast, there is no hard evidence to support the presumption that acquisitions by major tech companies result in decreased competition. A continuation of aggressive merger enforcement by the UK CMA would undermine investments in innovation-driven UK businesses and reduce access to funding for British venture capital-backed start-ups.

[1] New legislation was introduced to Parliament in July 2023, which proposes updating UK competition law and creating a new regulatory regime for digital markets. The new powers included in the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Bill (DMCC) will give the CMA the ability to set conduct requirements for large technology companies.

1. Introduction

Competition authorities around the globe formally share the same objectives. Their aim is to prevent or sanction anti-competitive behaviour. The overarching rationale behind merger enforcement, for example, is to prevent monopolistic practices and promote consumer welfare. Merger and acquisition policies are typically designed to strike a balance between allowing companies to merge and achieve synergies, such as increasing economic efficiency and innovative capacities, while also preventing the concentration of market power that could harm consumers. Competition authorities, however, often fail to adequately consider efficiency criteria and the resultant benefits for consumers, most notably in technology and innovation-driven industries.[1]

Competition authorities assess mergers and acquisitions through a comprehensive and systematic process to determine whether they are likely to result in anti-competitive outcomes. Assessing potentially anti-competitive effects requires lengthy investigations of company characteristics and relevant markets to get a solid understanding of the complex competitive effects. When conducting merger control, however, different jurisdictions apply different legal tests, standards and procedures for assessing the potential impact of acquisitions.[2] Merger control regimes also differ in the extent to which they accept defences based on efficiency considerations and structural or behavioural remedies offered by merging entities. Differing standards of assessment can imply that certain acquisitions are not considered problematic in some countries, while authorities in other countries apply much more restrictive standards and reviews respectively.

In this policy brief, we discuss the link between national merger enforcement and a country’s investment attractiveness. We argue that legal certainty is an important factor for investors, affecting the choice of investment targets and destinations. Uncertainty about the future legality of an acquisition may discourage investors from financing companies based in countries that are known for aggressive merger enforcement practices. The paper is structured as follows:

- Section 2 addresses concerns regarding over-enforcement of competition policy in the United Kingdom. We start with a discussion of the UK CMA’s recent investigation into Microsoft’s planned acquisition of Activision Blizzard before discussing recent developments in the in the way the CMA operates.

- Focusing on the impact of competition policy on investment and innovation, Section 3 discusses four aspects of competition policy and, in particular, merger enforcement which deserves greater attention by competition authorities and policymakers. These four aspects are: 1) the role of large companies in driving productivity growth, 2) the importance of a dynamic understanding of competition and innovation in technology-intensive industries, 3) the link between acquisitions and incentives to invest in start-ups and the provision of seed capital, and 4) misconceptions around killer acquisitions.

- Section 4 concludes with policy recommendations.

[1] See, e.g., ITIF (2021). Two Meanings of Dynamic Competition. Available at https://itif.org/publications/2021/12/23/two-meanings-dynamic-competition/. Also see, Petit and Teece (2021). Innovating Big Tech Firms and Competition Policy: Favoring Dynamic Over Statis Competition. Available at https://www.dynamiccompetition.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/DCI-WP2-–-Petit-and-Teece-2021.pdf.

[2] In Australia, the UK and the US, for example, the test is whether a merger can be expected to give rise to a substantial lessening of competition. In the EU, the European Commission considers whether a merger can be expected to give rise to a significant impediment to effective competition, and in Germany the test is whether the merger will create or strengthen a dominant position.

2. The UK’s Shift Towards a More Aggressive Approach to Competition Enforcement

The recent veto by the CMA on the Microsoft and Activision Blizzard merger has sparked criticism regarding the authority’s commitment to fostering competition and business growth. In contrast to EU and US approvals of the merger, the CMA declined it citing potential negative impacts on competition in the cloud gaming industry. The CMA’s recent decision, as well as the increased tendency of the CMA to prohibit mergers, has drawn serious criticism from the business community. Business representatives and policymakers are increasingly worried about the attractiveness of Britain as an international investment hub.

In January 2022, Microsoft announced plans to acquire Activision Blizzard (a leader in game development and interactive entertainment content publisher).[1] The goal of the acquisition is to accelerate the growth of Microsoft’s gaming business across mobile, PC, console and cloud and provide building blocks for the metaverse. The acquisition is worth USD 68.7 billion, making Microsoft the world’s third largest gaming company by revenue. Given that both parties are multinational corporations, the merger is subject to regulatory approval from competition authorities around the world.

The transaction is “vertical,” i.e., Microsoft and Activision are not direct rivals in the same relevant market (at least not principal rivals). The merger, therefore, has little or no “horizontal” effect. Accordingly, no significant “head-to-head” competition is likely to be lost or there will be no immediate increase in the market share.[2] In the past, the lack of horizontal effects may have been enough to push a vertical deal over the finish line. However, regulatory bodies and competition authorities are gaining more power and deeply investigating mergers and acquisitions that could turn into “killer acquisitions” and significantly harm competition. This explains the challenges faced by the Microsoft-Activision merger in the UK, but also concerns voiced in the US and the EU.

In February 2022, the US antitrust agency Federal Trade Commission (FTC) decided to launch an investigation to examine the impact of the deal on competition.[3] The UK CMA also raised competition-related concerns over the deal after a provisional investigation. The CMA said in a statement that the deal would hurt competition and that Microsoft could use its control over “Call of Duty” games to stifle competition in cloud gaming, multi-game subscriptions, and gaming consoles.[4] In November 2022, the European Commission also started an “in-depth investigation” over similar concerns.[5]

In December 2022, the FTC filed a lawsuit to block the deal in its in-house court over similar alleged harms as the CMA. The FTC was also concerned that the deal could foreclose competition in the market for multi-game content library subscription services,[6] and argued that the deal would hurt consumers whether they played video games on consoles or had subscriptions because Microsoft would have an incentive to shut out rivals like Sony Group. On 11 July 2023, a US judge denied the FTC’s motion for a preliminary injunction to stop Microsoft from completing its purchase of Activision Blizzard on the basis that the merger would not substantially lessen competition and to the contrary, there would be increased consumer access to Activision content.[7] The FTC withdrew its challenge in July 2023 and the merger is now a go in the US.[8]

In the EU, on 15 May 2023, the merger received the greenlight from the EU competition authority by agreeing to a free ten-year license for consumers in the European Economic Area, allowing gamers who bought an Activision game to stream it on gaming streaming platforms of their choice, including personal computers and consoles.[9] The Commission’s preliminary investigation found that Microsoft could harm competition (i) in the distribution of console and PC video games, including multi-game subscription services and cloud game streaming services; and (ii) in the supply of PC operating systems. However, the Commission’s in-depth market investigation indicated that Microsoft would not be able to harm rival consoles and rival multi-game subscription services. At the same time, it confirmed that Microsoft could harm competition in the distribution of games via cloud game streaming services and that its position in the market for PC operating systems would be strengthened.[10] As an additional form of remedy, Microsoft has agreed to bring Xbox PC games to Nvidia’s cloud gaming service and announced that it would offer royalty-free licenses to cloud gaming platforms to stream Activision games, if a consumer has purchased them.[11]

In contrast to these decisions in the US and the EU, the UK CMA provisionally blocked the deal, citing harm to the emerging cloud gaming industry[12] arguing the merger could result in higher prices, fewer choices and less innovation for UK gamers.[13] The CMA said that Microsoft would find it commercially beneficial to make Activision’s key games, such as Call of Duty, exclusive to its own cloud gaming platforms. However, the CMA also said that the acquisition would not reduce competition in the console market.[14] Microsoft offered a similar remedy to UK authorities as it did to the EU, but the CMA did not deem it sufficient on the basis that they would be difficult to monitor and enforce, and the rapidly fluctuating nature of the nascent cloud gaming sector means such a remedy may not take into account changes in the cloud market.[15]

It is noteworthy, however, that the deliberations in the EU and the US have had an impact on the CMA’s decision and negotiations may actually restart between CMA and Microsoft. In August 2023, the CMA has confirmed its decision to block the merger, but simultaneously announced to open a new investigation into a restructured acquisition proposal Microsoft had submitted for review.[16] The new remedies could include a divesture of Microsoft’s cloud gaming rights in the UK to appease the CMA officials.[17]

The CMA’s decision to block the acquisition of Activision by Microsoft is not an isolated case.

The growing assertiveness of the CMA towards mergers and acquisitions is clearly reflected in its rate of veto decisions. Between 2013 and 2017, CMA officials blocked only 30% of mergers. Since 2019, that has risen to 59%, as estimated by Frontier Economics (described as deal mortality comprising prohibition, unwind, and deal abandonment upon referral or during Phase 2). In addition, 76% of all investigations resulted in an intervention, i.e., either a prohibition or the imposition of remedies, with 24% unconditionally cleared.[18]

In 2022, nearly 60% of decisions taken by the CMA have resulted in a prohibition, abandonment, or remedies (compared to 43% in 2020 and 25% in 2021).[19] For example, the CMA blocked four deals and three more were abandoned due to the authority’s concerns. Three of the prohibitions were completed deals, resulting in the acquirer having to unwind the transaction (or, in one case, the UK part of the transaction). And there is no sign of a regime change.

Moreover, as reported by Linklaters, prominent cases like Facebook-Giphy, Sabre-Farelogix, and Illumina- PacBio mark a significant shift in the CMA’s approach toward merger enforcement. Notably, these cases involved relatively “small-target” deals, both on a global scale and particularly within the UK. In contrast to previous practices, the CMA seems to take a more proactive prosecutorial stance. This has also become evident when compared to merger enforcement by the European Commission. Since Brexit, the European Commission and the CMA issued unconditional clearance decisions in close proximity, often within a month of each other, in half of the cases subject to parallel reviews. Although the Commission usually granted clearance first, these parallel processes appeared relatively smooth from a timing perspective, considering the CMA’s lengthier statutory timetable for Phase 1 reviews and the unpredictable nature of the pre-notification process on both sides.[20]

There are a few cases that stand out in terms of differences in the substantive conclusions by the European Commission and the CMA. Divergences in decisions between the CMA and the European Commission have arisen from different interpretations of competitive dynamics and perspectives on remedies. Some cases reveal instances where investigators evaluated the same markets but reached contrasting conclusions, often hinging on remedy considerations. For example, in addition to the Microsoft-Activision case, the CMA blocked Meta from purchasing the gif repository Giphy, on the contested grounds that a Giphy might someday become a significant competitor to Facebook for digital advertising.[21] In Cargotec-Konecranes, the CMA effectively blocked the deal at Phase 2 by requiring a full divestiture, while the European Commission approved it with a remedy package. The CMA’s perspective was that it had to focus on the UK’s impact, even if the markets were supra-national.

There have been various reasons for the behavioural shift of the CMA from more passive to more aggressive.

Intellectually, the shift has partly been driven by research and consultations indicating that British competition regulators have long been too lenient towards mergers.[22] Moreover, the impacts of new technologies and digital services on competition have led to a departure from traditional indicators of competition such as prices, output and market concentration and led to tighter rules and tougher enforcement on technology-driven businesses globally. For example, notions that the power of a small number of technology firms is holding back innovation and growth in the UK have been quoted to defend the creation of a Digital Markets Unit (DMU) in the CMA.[23] The proposed regulatory body would target large technology platform companies and potentially enable the CMA to micromanage platform services through company “code of conduct” regulations, with minimal government oversight. The current proposal would grant the CMA wide discretion over the enforcement of new legal concepts, some of which are not defined in the current legal proposal, and provide only extremely limited appeal mechanisms.[24]

Institutionally, there has been a change in the CMA’s panel composition in 2017-2018. Between 2014-2015 and 2016–2017, the CMA’s panel of members tasked with running merger and market inquiries remained essentially unchanged. During 2017-2018, however, 24 members’ terms expired and over the following two years 22 people were appointed. “This rapid turnover brought a whole new cohort more amenable to the prevailing winds and with greater unified loyalty to the permanent CMA’s desires”.[25]

The Microsoft-Activision case demonstrates competition authorities can come to very different conclusions. Ultimately, it is the votes of the members of the panels and committees that determine whether a takeover can take place or not. In developed economies, it is reasonable to presume that specific principles of accountability are in effect, and these are considered during the process of investigations. However, it is always individual panel members who decide on structural or behavioural remedies and thus have an active influence on the operations of the target companies.

Procedurally, the appeals process against a CMA order is also extremely limited. The appeal goes to the Competition Appeals Tribunal, (CAT), which can only overrule the CMA when it finds that “the CMA acted irrationally, illegally or with procedural impropriety.” Appeals from the CAT to the UK courts can only centre around a dispute on a point of law meaning that the CMA wins most cases on appeal.[26]

Finally, there have been concerns that the CMA may be aiming to become a “world leader” in policing the actions of large non-UK firms. Accordingly, some of the CMA’s decisions may have been motivated by the observation that business conduct of large technology companies has not been properly addressed by EU and US competition authorities due to the need to change legal doctrines in the US and the need for unanimity in the EU. Because of its unique structure and powers as an independent non-ministerial department, so the argument goes, the CMA may be able to respond to changing ideologies in antitrust enforcement more freely.[27] The recent tightening of British competition law within the framework of the Digital Markets Unit and the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (DMCC) supports this thesis. For example, the proposed DMCC could empower the CMA to prohibit acquisitions of small companies by larger ones more easily. Intended to restrain large technology companies, the proposed DMCC would introduce new filing thresholds for “killer acquisitions” of nascent businesses, which would eliminate the need for an overlap between merging parties’ activities in the UK where one party has a high share of supply and substantial UK presence.[28]

[1] Microsoft (2022). Microsoft to acquire Activision Blizzard to bring the joy and community of gaming to everyone, across every device. 18 January 2022. Available at https://news.microsoft.com/2022/01/18/microsoft-to-acquire-activision-blizzard-to-bring-the-joy-and-community-of-gaming-to-everyone-across-every-device/.

[2] National Law Review (2023). Ideology or Antitrust? U.S. FTC and U.K. CMA Move to Block Microsoft / Activision Deal. 28 April 2023. Available at https://www.natlawreview.com/article/ideology-or-antitrust-us-ftc-and-uk-cma-move-to-block-microsoft-activision-deal.

[3] FCT (2023). In the Matter of Microsoft Corporation, a corporation, and Activision Blizzard, Inc. Available at https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/2210077-microsoftactivision-blizzard-matter.

[4] CMA (2023). Anticipated acquisition by Microsoft of Activision Blizzard, Inc. – final report. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/644939aa529eda000c3b0525/Microsoft_Activision_Final_Report_.pdf.

[5] European Commission (2022). Case M.10646. Available at https://competition-cases.ec.europa.eu/cases/M.10646.

[6] Bloomberg (2023). Microsoft-Activision Deal’s Bumpy Regulatory Road: Explained. 16 May 2023. Available at https://news.bloomberglaw.com/antitrust/microsoft-activision-deals-bumpy-regulatory-road-explained.

[7] CNBC (2023). Microsoft-Activision deal moves closer as judge denies FTC injunction request. 11 July 2023. Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2023/07/11/microsoft-activision-deal-moves-closer-as-judge-denies-ftc-injunction.html.

[8] The Verge (2023). FTC withdraws its in-house challenge to Microsoft’s Activision Blizzard deal. 21 July 2023. Available at https://www.theverge.com/2023/7/20/23795591/ftc-microsoft-activision-administrative-challenge.

[9] Bloomberg (2023). Microsoft-Activision Deal’s Bumpy Regulatory Road: Explained. 16 May 2023. Available at https://news.bloomberglaw.com/antitrust/microsoft-activision-deals-bumpy-regulatory-road-explained.

[10] European Commission (2023). Mergers: Commission clears acquisition of Activision Blizzard by Microsoft, subject to conditions. 15 May 2023. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_2705.

[11] CNBC (2023). The UK — which blocked the Microsoft-Activison deal — is ready to negotiate. Here’s what happens next. 12 July 2023. Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2023/07/12/microsoft-activision-uk-cma-softens-stance-after-blocking-deal.html.

[12] Bloomberg (2023). Microsoft-Activision Deal’s Bumpy Regulatory Road: Explained. 16 May 2023. Available at https://news.bloomberglaw.com/antitrust/microsoft-activision-deals-bumpy-regulatory-road-explained.

[13] The Washington Post (2023). The Hurdles That Remain for $69 Billion Microsoft-Activision Deal. 11 July 2023. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/07/11/the-hurdles-that-remain-for-microsoft-activision-deal-quicktake/c2f3ba5a-200b-11ee-8994-4b2d0b694a34_story.html.

[14] CNBC (2023). EU approves Microsoft’s $69 billion acquisition of Activision Blizzard, clearing huge hurdle. 15 May 2023. Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/15/microsoft-activision-deal-eu-approves-takeover-of-call-of-duty-maker.html.

[15] https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/15/microsoft-activision-deal-eu-approves-takeover-of-call-of-duty-maker.html

[16] See TechCrunch (2023). UK’s CMA confirms decision to block Microsoft-Activision but opens fresh probe of restructured deal proposal. 22 August 2023. Available at https://techcrunch.com/2023/08/22/microsoft-activision-uk-cma-new-probe/?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAI1ytffioXOwMewHuKohj9h3lqW0iH9jimF2nhseidfobygvGkCa_iDwPoeo03RHsFPLfppIyWLs2zHHrOpkcvr0YNxFUfMFAMQd_dEbjuDdlbW44M0rbNNjjV-IoNTF0AbSikegpbibk-loPzKn3-pL8dzeoL306d_RlN1_ZVV4.

[17] Bloomberg (2023). Microsoft, Activision Eye UK Rights Sale to Get Merger Done. 14 July 2023. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-13/microsoft-activision-weigh-sale-of-some-uk-cloud-gaming-rights.

[18] Frontier Economics (2023). Platypus: UK Merger Control Analysis. Available at https://www.linklaters.com/en/insights/publications/platypus/platypus-uk-merger-control-analysis.

[19] Allen & Overy (2023). Aggressive merger control enforcement causes a rise in frustrated deals. 23 February 2023. Available at https://www.allenovery.com/en-gb/global/news-and-insights/publications/aggressive-merger-control-enforcement-causes-a-rise-in-frustrated-deals.

[20] Linklaters (2023). Is breaking up that hard to do?: taking stock on parallel EU/UK merger reviews since Brexit “freedom”. 17 March 2023. Available at https://www.linklaters.com/en/insights/publications/platypus/platypus-uk-merger-control-analysis/seventeenth-platypus-post—is-breaking-up-that-hard-to-do.

[21] UK CMA (2022). CMA orders Meta to sell Giphy. 18 October 2022. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-orders-meta-to-sell-giphy.

[22] See, e.g., Travers Smith (2021). UK merger control and markets reform – where next? Available at https://www.traverssmith.com/knowledge/knowledge-container/uk-merger-control-and-markets-reform-where-next/.

[23] Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2021). A new pro-competition regime for digital markets

July 2021. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1003913/Digital_Competition_Consultation_v2.pdf.

[24] New legislation was introduced to Parliament in July 2023, which proposes updating UK competition law and creating a new regulatory regime for digital markets. The new powers included in the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Bill (DMCC) will give the CMA the ability to set conduct requirements for large technology companies.

[25] Bourne, R. (2023). Handing Regulators a Blank Cheque Will Make Britain a Tech Turn‐off. Available at https://www.cato.org/commentary/handing-regulators-blank-cheque-will-make-britain-tech-turn

[26] See, e.g., Field Fisher (2023). Stiff competition: The difficulty of appealing a CMA decision in a merger review. 4 May 2023. Available at https://www.fieldfisher.com/en/insights/stiff-competition-the-difficulty-of-appealing-a-cma-decision-in-a-merger-review.

[27] CEI (2021). Britain’s Competition and Markets Authority Is Becoming a Global Problem. Available at https://cei.org/blog/britains-competition-and-markets-authority-is-becoming-a-global-problem/.

[28] See, e.g., Skadden (2023). UK To Revamp Merger Control, Expanding CMA’s Jurisdiction and Making Procedures More Flexible. 2 May 2023. Available at https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2023/05/uk-to-revamp-merger-control.

3. Merger Enforcement and Potential Impacts on Investment and Innovation Attractiveness

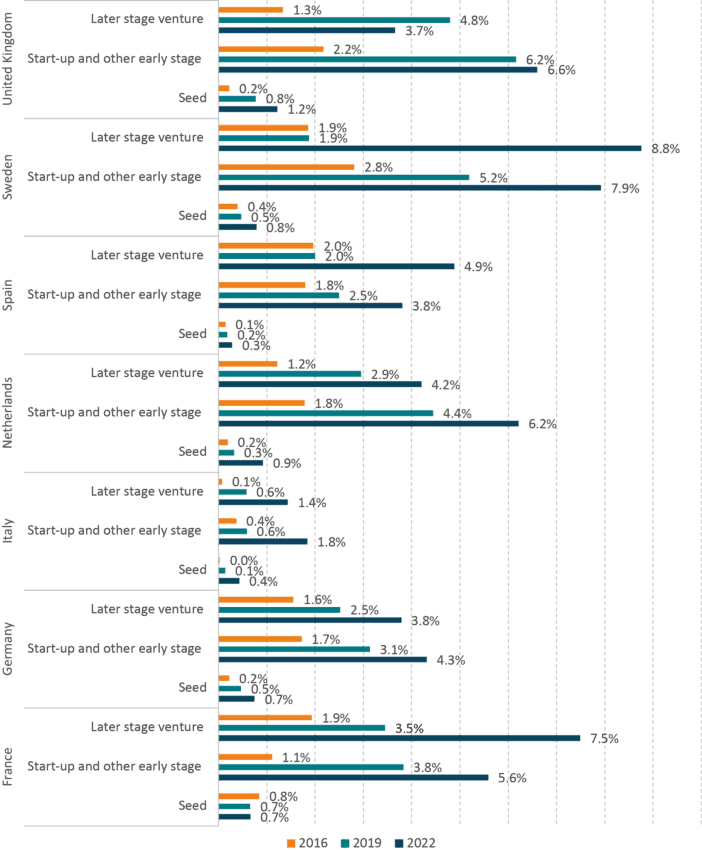

The CMA’s ruling to block Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision Blizzard has sparked strong reactions. The decision was heavily criticised for harming the UK’s economic prospects, hindering businesses’ growth strategies, and presenting the UK as unwelcoming to global innovators and investments. Concerns were also raised about the impact on new start-ups, emphasising the need for exit strategies and avenues for investment.

The ruling was also seen as an example of the increasing difficulties of doing business in the UK due to increasing regulatory burdens for companies. The negative commentary is surrounded around the lack of legal predictability in the UK because of a missing transparent and consistent framework that guides open and competitive markets. Moreover, it was argued that new regulatory mechanisms such as the DMCC bill are adding to the uncertainty and regulatory burden for companies investing in the UK. Many observers are now calling for more political accountability and a transparent, consistent framework to encourage investment and maintain open and competitive markets while minimising political intervention risks (Table 1).

Table 1: Commentary on the current UK competition and regulation framework Source: authors’ own research.

Source: authors’ own research.

Overall, many commentators emphasise the importance of fostering a favourable environment for innovation, investment, and competitive markets, addressing concerns about over-enforcement of competition policy. Observers who expressed more positive views are citing regulators taking their responsibilities seriously and allowing for robust scrutiny. The broader sentiment is that regulators should actively vocalise concerns about the behaviour of large tech companies when necessary.

During discussions about the DMCC Bill in Parliament, some observers argued that the new regulatory framework may actually contribute to attracting investment into the UK’s digital sector. However, it is unclear how this can be accomplished with a UK competition policy that is both aggressive in its approach to merger control and looking to expand its powers under a competition law reform that is based on untested theories and misconceptions around dynamic competition and killer acquisitions.

Focussing on potential impacts on investment and innovation, below we discuss four aspects of competition policy and, in particular, merger enforcement that deserve greater attention by competition authorities and policymakers.

3.1. The Role of Large Companies in Driving and Economy’s Productivity Growth

Large companies play a significant role in driving and economy’s productivity growth. Many economic arguments suggest that governments should be open to mergers to enable efficiency gains. For example, larger production leads to lower average costs (economies of scale), enabling them to offer competitive prices and generate higher profits. Better access to financial resources allows larger companies to invest relatively more in research, technology, and new processes, fostering industry-wide productivity improvements. In fact, large companies significantly outperform small companies in R&D investments.[1] Better financial access allows them to undertake large projects, expand, and explore new markets, driving growth. Large companies’ capacity for significant investment in technology and markets spurs adoption of advanced tools and practices. Large companies also tend to have a better skilled workforce. Investments in training enhance workforce efficiency, reducing errors and improving overall productivity. Large companies typically operate in international markets. Complex networks streamline sourcing, distribution, and inventory, cutting costs and boosting productivity. Operating globally exposes them to competitive markets and practices, enhancing productivity through knowledge sharing and the adoption of new technologies. Competition and international innovation incentivizes them to innovate, resulting in efficiency gains, cost reductions, and novel strategies. Research shows, for example, that subsidiaries of multinational enterprises in the UK are on average more R&D-intensive and have a higher level of investment in intangibles which significantly impact regional productivity growth in the UK.[2]

The activities of large technology companies and opportunities to scale (expansion of market size) are particularly important for investments in innovation and productivity growth. Corporate data reveals that EU and UK’s underperformance in technology development and international competitiveness is largely caused by businesses struggling to successfully grow and invest in and beyond Europe. A recent analysis of corporate data shows that between 2014 and 2019, large European companies with more than USD 1 billion in annual revenue were on average 20% less profitable than their US counterparts. Also, European businesses’ revenues have grown 40% less than those of US companies, and European businesses spent about 40% less on corporate R&D.[3] It is highlighted that Europe’s remarkable underperformance cannot be merely attributed to a few “US superstar companies” in computer and digital services industries. Indeed, in a large part, European corporate underperformance can be attributed to underperformance in a broad spectrum of technology-creating (sometimes called transversal or general purpose technologies) industries, including ICT and pharmaceuticals, which “together account for more than 90% of the return on invested capital gap, over 80% of the gap on capital expenditure relative to the stock of invested capital, more than 60% of the revenue growth gap, and over 70% of the R&D intensity gap“.[4]

Competition authorities do not inherently condemn large companies simply for being large. The primary goal of major competition authorities has long been to prevent anticompetitive behaviour that could harm consumers or the overall competitive landscape. For a long time, being a large company was not considered a problem in itself; rather, the concerns arose when a large company engaged in practices that stifled competition, limited consumer choice, or distorted the market. In the US, for example, the consumer welfare standard generally implies that overall consumer welfare and economic efficiency of (large) companies, should be the main criteria regulators look to when evaluating a merger or alleged anticompetitive behaviour.[5]

The CMA’s statutory duty, as outlined in the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013, is to promote competition for the benefit of consumers. Like other competition regulators, the CMA considers a range of factors beyond just consumer welfare, including the impact on competitors, innovation, and market structure. However, while consumer welfare still is a central principle, the CMA’s recent decisions point towards a deviation from consumer welfare to other priorities, often underpinned by ill-defined concepts about fairness, potential competition, and nascent competition. The latest developments in UK merger enforcement, but also the far-reaching enfacement powers from the proposed DMCC give cause for concern that the UK CMA could in the future deviate further from consumer welfare and efficiency considerations. Stricter merger enforcement and restrictions on the behaviour of large technology companies would have a negative impact on the UK’s investment climate. Should the UK become less attractive to large investors, this would have a negative impact on investment and productivity growth.

3.2. The Importance of Dynamic Competition in Technology-Intensive Industries

A competition policy in support of innovation and growth should not attempt to systematically prevent mergers. Considerations by competition regulators often overlook the complexity of value creation in industries that are adopting technologies and services provided by large tech companies. Online platform providers, for example, provide services as part of integrated platform ecosystems, where joint value generation and interdependence among participants play crucial roles. The enormous value and innovation created by large online platforms and their contributors as well as the continuous pressure to innovate reveal that the rationale for regulation typically does not fit the narratives of competition regulators.

In digital markets, it is important not to adopt too “static” a view of competition; a firm may have a high market share at a particular point in time but be vulnerable to entry by a firm with a new technology.

Static competition refers to competition that occurs within the current state of a market, where firms compete primarily based on existing factors such as prices, quality of products, marketing, and other immediate attributes. Competition authorities should rather prioritise dynamic competition. Dynamic competition pertains to the ongoing rivalry among businesses that extends over time, taking into account their strategic actions aimed at enhancing their positions within the market for the long haul. This encompasses not solely the present conditions of the market but also how companies engage in innovation, allocate resources, and modify their approaches to establish competitive edges and influence the trajectory of the market in the future.

Dynamic competition encompasses elements such as advancements in technology, the pursuit of research and development, strategic capital investments, and the capacity to adjust to shifts in market trends. For example, while large online platforms reduce costs and improve productivity, their primary efficiency effects stem from continuous innovation and the sharing and recombining of digital and non-digital resources. The generative potential of integrated digital ecosystems is significant, as platforms actively contribute to the creation of new services and processes, and constantly react and shape global competition.

Competition authorities, including the UK CMA, tend to view large platforms as statically dominant, potentially causing harm when expanding into new markets. However, platforms are evolving entities that continuously enter new areas and engage in competitive dynamics with other platforms, often challenging each other in unexpected ways. Accordingly, a “dynamic” view of the market is needed when deciding whether an incumbent firm has market power.[6]

3.3. The Link Between Acquisitions and Incentives to Invest in Innovation

Competition regulators must recognise that ideologically charged investigations into mergers and acquisitions ultimately have a negative impact on a country’s investment attractiveness as they undermine traditional forms of equity investments in innovation-driven industries and venture capital-backed start-ups. The prospect of an innovative and commercially successful company being taken over by another company is an important precondition for investors to make early-stage and continued seed capital investments. Acquisitions also play an important role in driving investments in business growth and internationalisation.

Mergers and acquisitions are a key exit option for venture capital and seed investors. Venture capital investors (VCs) typically fund start-ups and early-stage companies including those that bear high business and R&D risks. Due to high risks, these investors demand high returns on investment reflected by monetisation strategies that include mergers and acquisitions. Data indicates that VCs achieve the highest return on investment through Initial Public Offerings (IPOs). However, because IPOs tend to be the exception, many VC investors have no choice but to sell their shares to other owners, often of other companies.[7] Stricter merger rules would worsen investors’ prospects with regard to exit options, which can have a negative impact on investments in the regulated economy.

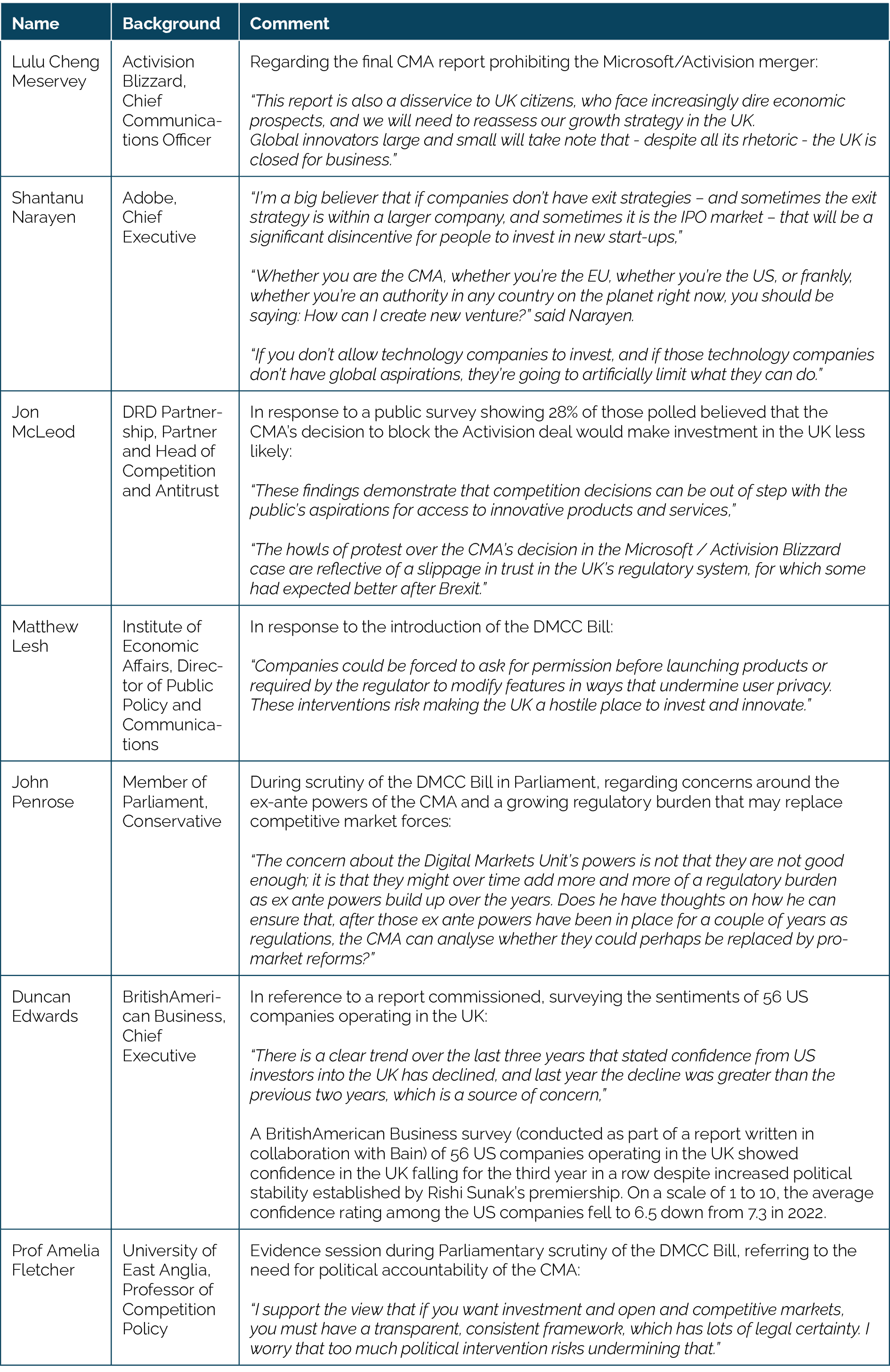

Anticipating the possibility of a blocked merger or acquisition, investors could stop providing seed capital in the first place, or refuse to extend additional funding to VC-backed companies to continue operations as a standalone company. Given that late-stage ventures generally account for the largest portion of total VC investments, divestments can have a major impact on domestic investment capacities (see Figure 1).

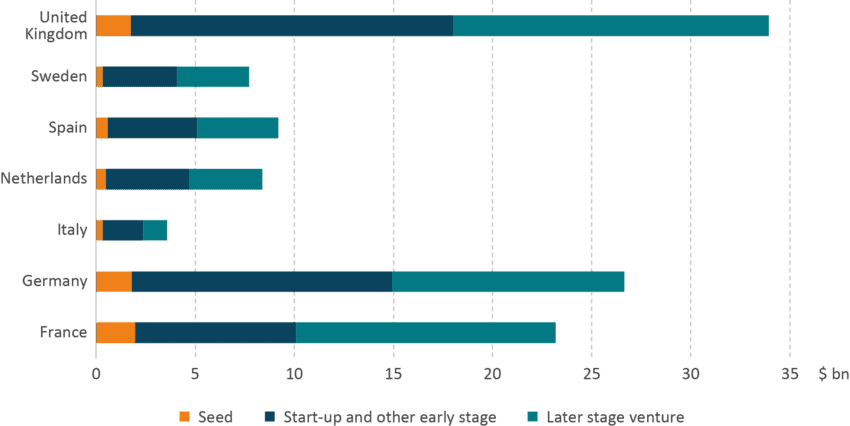

Although it is difficult to quantify the economic risks, it would be inappropriate to understate the long-term effects of a competition policy that discourages takeovers of small companies by large companies. Restrictive merger policy can have significant negative consequences for investments in promising (high impact) innovations. Data for the US, for example, reveal that firms once backed by venture capital accounted for 92% of R&D spending and patent value generated by US public companies founded over the past 50 years.[8] VC investments are of particular importance in the development and diffusions of transversal technologies, e.g., software and digital services and biopharmaceutical industries. The software and digital services sector has been a major driver of VC deal-making in the past (see Figure 2), and it is expected to continue its expansion given previous investments.[9] If transactions are increasingly scrutinised by the UK competition authority, Britain’s venture capital ecosystem may shrink significantly.

Figure 1: Venture capital investments in Europe, 2007-2022 Source: OECD Entrepreneurship Financing Database.

Source: OECD Entrepreneurship Financing Database.

Figure 2: Venture capital investments in Europe, 2007-2022 Source: Pitchbook

Source: Pitchbook

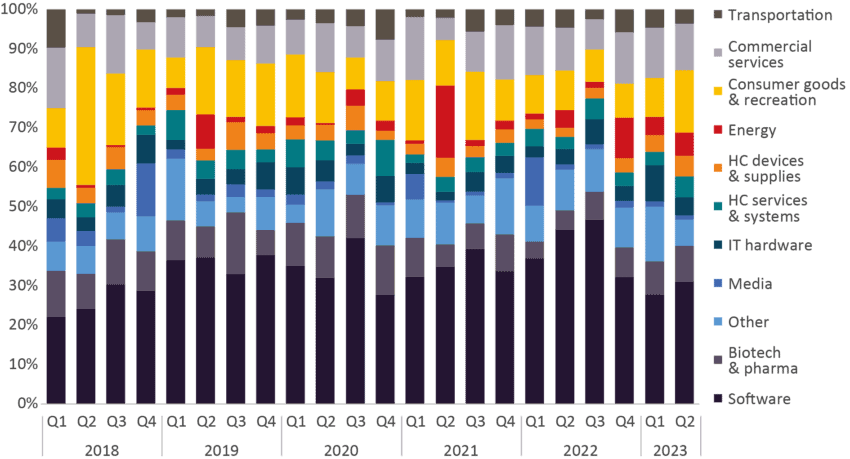

Mature economies like the UK naturally compete with other developed countries for investment, including foreign direct investment (FDI) and venture capital. As concerns the latter, the UK, Germany, and France have been the leading European countries in terms of cumulative venture capital investments over the past 15 years. Although the UK has been the leading ecosystem in terms of VC, other European countries, such as France, the Netherlands, and Sweden, have recently seen a rapid increase in VC activity (see Figure 3). Following Brexit and the loss of gravity of a large EU market, the UK may by default become less attractive to investors. This development alone should prompt UK competition policy not to drain the country’s investment climate through aggressive merger policies and bold interventions in the conduct of large technology companies, which are the top investors in technological innovation globally.[10]

Figure 3: Development of venture capital investments in Europe, in % of GDP, 2016, 2019, 2022 Source: OECD Entrepreneurship Financing Database.

Source: OECD Entrepreneurship Financing Database.

3.4. Misconceptions Around Killer Acquisitions

Killer acquisitions are based on a dynamic view of competition in the digital platform sector. Killer acquisitions have become a central topic in antitrust discussions due to concerns that they could remove sources of future competition from markets because of acquiring firm’s monopoly power in the present. However, the premise that acquisitions by prominent tech companies inherently result in decreased competition lacks a solid evidential basis. As there is no evidence of killer acquisitions, transactions between large and small companies should not be prosecuted by competition authorities. Systematic interference by competition regulators would inhibit investment incentives

In theory, the term “killer acquisition” refers to the strategy where large corporations acquire smaller companies that have the potential to become their rivals, with the intention of shutting down these competitors. Based on such notions, killer acquisitions can be classified as acquisitions of rival companies with the sole purpose of terminating their operations. By contrast, it is also argued that such acquisitions may in fact reflect a desire to exploit complementarity effects by combining the assets of the target with those of the acquirer.[11] And others argue that acquisitions of smaller companies are motivated by an aim to diversify product portfolios[12] or combine R&D activities.[13]

Transactions that involve smaller companies are often not automatically reviewed by competition authorities as the turnover threshold for merger control is usually not met. In the digital sector, empirical evidence shows that killer acquisitions are rare. A recent study finds that only one in 175 transactions qualify as killer acquisitions.[14] Moreover, upon analysing the European Commission merger cases for killer acquisitions in the EU, it was found that acquisitions did not lead to the termination of innovative products of the acquired firm by the acquiring company, i.e., the products or services because of which the acquisition took place did not disappear from the market. Furthermore, no evidence was found for a weakening of competition, and lowering or absence of entry and innovation.[15]

[1] See, e.g., Harvard Business Review (2019). The Gap Between Large and Small Companies Is Growing. Why? Available at https://hbr.org/2019/08/the-gap-between-large-and-small-companies-is-growing-why.

[2] MRPA (2015). The Impact of Multinational and Domestic Enterprises on Regional Productivity: Evidence from the UK. MPRA Paper. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00343404.2018.1447661#:~:text=The%20empirical%20evidence%20shows%20that,outperform%20MNEs%20from%20certain%20countries.

[3] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness – Addressing its technology gap. September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/strategy%20and%20corporate%20finance/our%20insights/securing%20europes%20competitiveness%20addressing%20its%20technology%20gap/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap-september-2022.pdf.

[4] The authors stress that high ROIC can reflect entrenched market positions and pricing power. However, “the growth and R&D gaps are clearly not sustainable for Europe.”

[5] See, e.g., ITIF (2018). Why the Consumer Welfare Standard Should Remain the Bedrock of Antitrust Policy. Available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/JU/JU05/20181212/108774/HHRG-115-JU05-20181212-SD004.pdf.

[6] See, e.g., Garces, Eliana (2023). Eliana Garces: “Regulation and Competition in Digital Ecosystems: Some Missing Pieces”. Available at https://www.networklawreview.org/digital-ecosytems-missing-pieces/.

[7] American Bar Association (2023). Merger Enforcement Considerations – Implications for Venture Capital Markets and Innovation. June 2023. Available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/antitrust_law/resources/source/2023-june/merger-enforcement-considerations/.

[8] Atomico (2022). State of European Tech. Available at https://stateofeuropeantech.com/5.outcomes/5.1-private-markets.

[9] Pitchbook (2023). European Venture Report (2023). Available at https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/Q2_2023_European_Venture_Report.pdf.

[10] See, e.g., Insider Monkey (2023). 20 Largest R&D Companies in the World. 4 May 2023. Available at https://www.insidermonkey.com/blog/20-largest-rd-companies-in-the-world-1144181/.

[11] Luis, C. (2021). Merger Policy in Digital Industries. Information Economics and Policy.

[12] Geoffrey, Bowman and Auer (2022). Technology Mergers and the Market for Corporate Control. Missouri Law Review.

[13] Lundqvist (2022). Killer Acquisitions and Other Forms of Anticompetitive Collaborations in Time of Corona. BRICS Competition Law and Policy Series Working Paper No. 22/2022/01.

[14] Gautier and Lamesch (2021). Mergers in the Digital Economy. Information Economics and Policy.

[15] Ivaldi et al. (2023). Killer Acquisitions: Evidence from EC Merger Cases in Digital Industries. TSE Working Paper No. 13-1420, Available http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4407333.

4. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The recent veto by the UK CMA on the Microsoft and Activision Blizzard merger has raised concerns about the authority’s commitment to promoting competition, business growth, and consumer welfare. Unlike the EU and US, the CMA rejected the merger due to potential negative effects on competition in cloud gaming. This decision, coupled with the CMA’s growing tendency to block mergers, has faced strong criticism from the business community, fuelling worries about Britain’s attractiveness for international investment.

The CMA’s veto of the Microsoft-Activision merger is not an isolated incident. Its increased assertiveness in mergers is evident in a rising rate of veto decisions. 76% of merger cases resulted in an intervention, either through prohibition or remedies, while 24% were unconditionally cleared. This shift in approach is attributed to several factors, including the CMA’s institutional set-up and an inclination of panel members to take a more aggressive stance towards mergers and large technology companies.

Critics emphasise the need for a favourable environment for innovation and investment, and the sentiment is regulators should voice concerns about tech giants when necessary. Concerns also pertain to the proposal of establishing the Digital Markets Unit, a big tech watchdog, which is argued to potentially have a detrimental impact on the UK’s appeal to start-ups and large-scale investors.

The CMA’s tendency to assume that large tech companies’ acquisitions harm competition lacks empirical evidence. Strict merger enforcement negatively impacts the UK’s investment attractiveness, undermining equity investments in innovation and start-ups. Acquisitions drive business growth and internationalisation. There is no systemic evidence of negative effects on competition and innovation from so-called killer acquisitions.

The prospect of an innovative and commercially successful company being taken over by another company is an important precondition for investors to make early-stage and continued seed capital investments. Acquisitions also play an important role in driving investments in business growth and internationalisation. Large companies are in fact major drivers of productivity enhancements and economic growth.

Competition policy supporting innovation should avoid taking ideological views on mergers and acquisitions, which could lead to a systematic prevention of mergers. Regulators often overlook the complexity of value creation in tech-driven industries. Competition regulators need to prioritise dynamic competition, innovation, and resource allocation over time.