Mass Litigation and the Future of Litigation Funding in Ireland and Europe

Published By: Oscar Guinea Dyuti Pandya Vanika Sharma Renata Zilli

Research Areas: European Union

Summary

Across Europe, collective actions are on the rise. Expanding liability regimes and the rapid growth of third-party litigation funding (TPLF) are fuelling a new wave of lawsuits that reach far beyond traditional consumer claims. Ireland has until now been shielded by common law restrictions on TPLF, but that protection is weakening. The transposition of the EU Representative Actions Directive (RAD) opens the door to new collective claims, including those backed by commercial funders that invest in such litigation in order to make a profit.

Ireland is uniquely exposed to these developments. Its economic model relies heavily on foreign direct investment, particularly from the US. Of more than 460 collective action cases tracked in the EU over the past 18 years, 40 involved US companies, many of which operate their European headquarters from Ireland. Information and communication technology and life sciences sectors, two of Ireland’s most important economic engines, are among the most frequent targets of collective lawsuits. If the conditions for launching a collective action and granting access to TPLF become too favourable, Ireland – the only EU country with common law procedures, broad disclosure rules and English-language litigation could become an attractive venue for mass litigation.

The supposed benefits of mass litigation are, in practice, limited. Evidence from the US and UK shows that consumers rarely receive meaningful compensation. Lawyers and funders capture the bulk of settlements, while claimants often receive token amounts. By contrast, the costs are large and measurable: higher legal expenses, falling market valuations, and weaker incentives for innovation. For Ireland, the scenario analysis suggests potential economic costs in the billions of euros, exceeding the annual public budget for infrastructure. The negative impact is not confined to domestic cases: collective actions pursued elsewhere against firms headquartered in Ireland also ripple back to the Irish economy through lost growth and reduced investment.

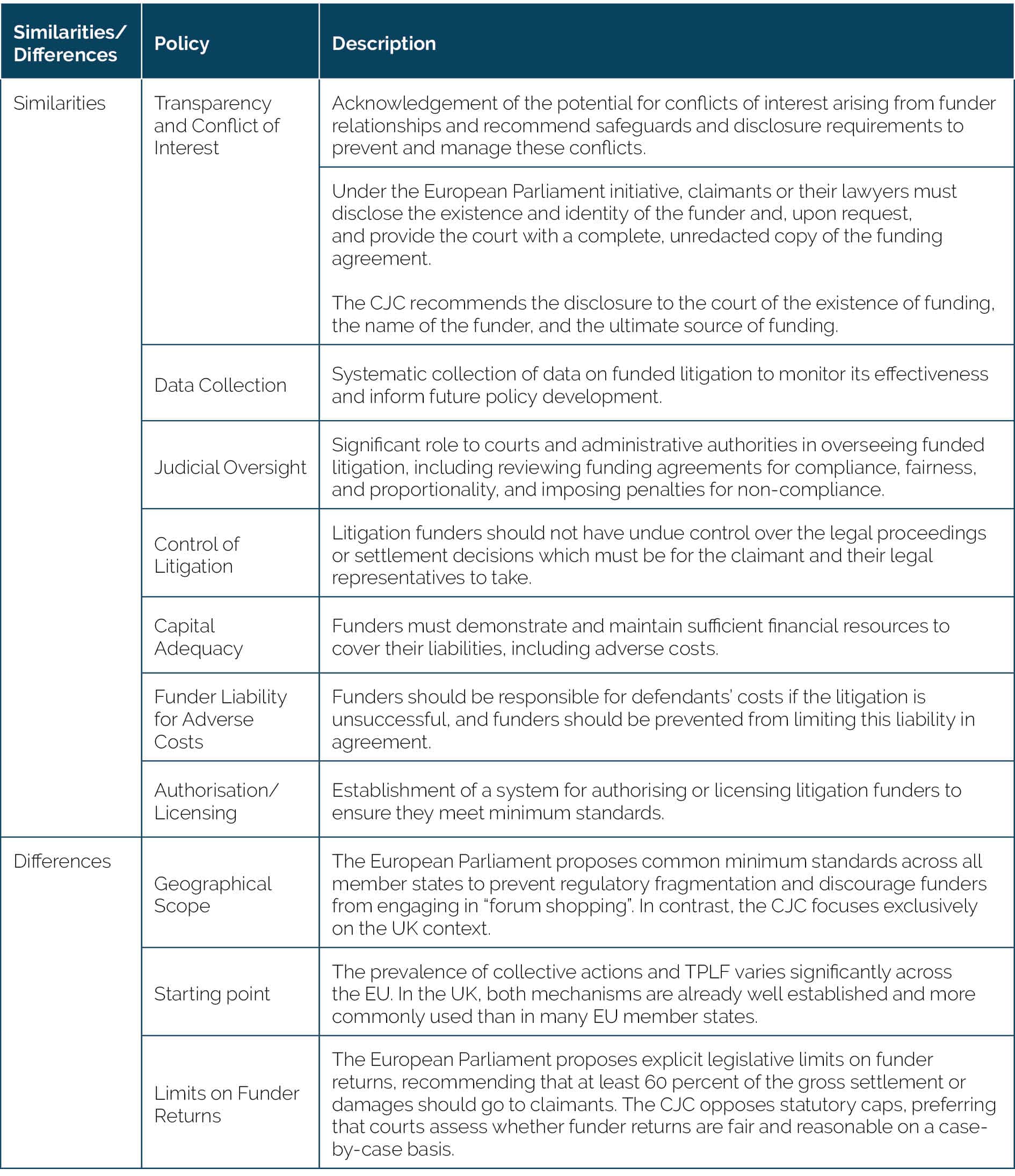

These risks cannot be managed through national policy alone. The RAD’s cross-border provisions and the free flow of capital mean that litigation funding can reach Irish courts even if TPLF remains restricted domestically. This underlines the need for a coherent EU-wide framework. The European Parliament and more recently the UK Civil Justice Council (CJC) have called for tighter oversight, including transparency rules, limits on funder returns, judicial scrutiny of funding contracts, and liability for costs if cases fail. Minimum standards cannot be achieved by member states acting alone.

Ireland has a chance to lead. As the incoming holder of the EU Council Presidency from July 2026, it will be well positioned to put the regulation of TPLF on the European agenda. A robust framework would not only protect consumers but also safeguard Europe’s competitiveness, reduce the risk of forum shopping, and ensure that litigation funding enables the delivery of justice rather than financial speculation via the courts. For Ireland, the stakes are high: the country has the most to lose if unchecked mass litigation undermines foreign investment and innovative industries upon which its prosperity rests.

This report was commissioned by the European Justice Forum, a coalition of businesses, individuals and organisations that are working to build fair, balanced, transparent and efficient civil justice laws and systems for both consumers and businesses in Europe.

Foreword by Former Tánaiste Mary Harney

Ireland’s economic transformation is rightly described as a miracle. From modest beginnings, we have built one of the world’s most competitive economies, anchored in life sciences, food and drink, information and communications technology, and financial services. Foreign direct investment has brought high-quality jobs, boosted exports, and delivered corporation tax receipts that have allowed us to invest in public services and infrastructure and improve living standards. Ireland is now a recognised hub for international services and is one of the most attractive destinations for global business.

But this success must also be protected. Our prosperity depends disproportionately on a small number of multinational firms and a few strategic sectors. Just ten companies provide more than half of all corporation tax, and three alone account for a third. As a recent Financial Times article made clear, without these receipts Ireland would have run deficits every year since 2008. That concentration is both a strength and a vulnerability.

This ECIPE report highlights a new and underappreciated risk: the unchecked rise of third party-funded mass litigation. Ireland has so far avoided the wave of investor-driven lawsuits that has swept other jurisdictions, but our exposure is unusually high. The very sectors that underpin our prosperity – life sciences and ICT, which account for nearly one-third of Ireland’s inward FDI – are also those most targeted by mass claims. Many of the multinationals here have already faced such actions abroad.

The report’s modelling shows what is at stake. Depending on the scenario, a wave of mass litigation could cost Ireland between €1.2 and €3.6 billion annually – more than the country’s entire infrastructure budget. For a small, concentrated economy, such costs would not just weigh on companies but on employment, innovation, and the public finances. Ireland already has one of the highest litigation cost environments in Europe, and even a conservative growth in mass claims would raise us to among the very highest.

The risks to innovation are particularly troubling. Ireland punches above its weight in R&D, with firms headquartered in Ireland making up almost 2 percent of the market value of the world’s top R&D investors – four times the country’s share of global GDP. If these firms were exposed to mass litigation claims in Ireland, their potential losses in market value could reach €6.6 billion – a direct hit to research budgets and to Ireland’s reputation as a hub for innovation.

The example of the UK offers a cautionary lesson. Since the early 2010s, the UK’s collective action caseload has increased nearly five-fold, with the most recent CMS European Class Action Report estimating the cumulative value of such claims at more than €154 billion. These cases are often driven not by consumers but by funders, with large portions of awards consumed by fees and opaque returns. Ireland should not follow the same path.

Our challenge is to ensure that access to justice is preserved without allowing litigation to be distorted into an extractive industry. That means building transparency, fairness, and accountability into our system – and acting now to prevent costly mistakes later. Ireland’s Presidency of the EU Council in 2026 is a unique opportunity to shape EU rules on third-party litigation funding in a way that reflects these priorities.

This ECIPE study is a valuable and timely contribution. By combining rigorous analysis with clear policy recommendations, it shows how Ireland can safeguard its economic miracle. With foresight, we can remain one of the world’s best places to innovate and invest – not a playground for speculative litigation.

Mary Harney, Former Tánaiste

October 2025

1. Introduction

Across the European Union, the number of collective actions is rising. Consumers, investors and other affected groups are increasingly using the courts to seek redress on a wide range of issues, from data protection breaches to product liability. This growth is no coincidence. It has been fuelled by a combination of EU and national policies to increase access for consumers to collective actions for the purpose of obtaining redress, continuously enlarged regulatory liability and the expansion of third-party litigation funding (TPLF) where private investment firms finance claims in exchange for a share of the proceeds. While such funding can improve access to justice, it also introduces new risks. By bankrolling lawsuits, funders may exert control over legal strategies, settlements, and even procedural decisions taken by claimants during the litigation process.

Ireland, however, has stood apart from this trend. As explained in Chapter 3, its legal system still upholds the common law principles of maintenance and champerty which prohibit the funding of litigation by third parties who have no direct interest in the case. These rules have, to date, shielded the Irish legal and economic system from the challenges associated with TPLF, but this situation may change soon. The implementation of the EU Representative Actions Directive (RAD) obliged all member states, including Ireland, to provide mechanisms for collective redress.[1] As described in the next chapter, the first such collective action has already been accepted by the High Court. Due to the cross-border nature of the Directive, Irish courts may formally recognise judgments initiated in other EU jurisdictions, even if they are backed by third-party funders.[2]

These developments are not just legal technicalities. They strike at the heart of Ireland’s economic model. As this study later shows, many recent collective actions in the EU and abroad have targeted companies in the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and life sciences sectors, two of Ireland’s most strategically important industries. Both sectors have attracted high levels of foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly from the United States. If the use of TPLF in the EU continues to grow unchecked, Irish-based multinationals may find themselves entangled in a growing number of mass litigation cases arriving from the continent.

To safeguard its interests, Ireland cannot rely on national policy alone. Even with restrictions on domestic litigation funding, the free flow of capital and legal claims across the EU makes national borders, including Ireland’s, porous to the risks posed by TPLF. What is needed is a coherent, EU-wide regulatory framework. Ireland should, therefore, take the lead in shaping such a policy: one that limits the risks of abuse, ensures transparency and accountability, and protects Europe and Ireland’s economic competitiveness. As Chapter 6 of this paper argues, Ireland is uniquely positioned to champion this cause during its upcoming Presidency of the Council of the EU in 2026.

The structure of this ECIPE Occasional Paper reflects this evolving legal and economic context. Chapter 2 outlines Ireland’s current enforcement framework, contrasting the longstanding primary role of public regulators with the limited scope for private enforcement through the courts. Chapter 3 focuses on third-party litigation funding, including its legal status in Ireland. Chapter 4 sets out why Ireland is especially vulnerable to the risks associated with TPLF, examining both the legal incentives and the level of economic exposure. Chapter 5 presents the limited benefits to be gained and calculates the significant potential costs of expanding mass litigation in Ireland based on empirical literature, actual cases, and scenario analysis. Chapter 6 broadens the lens to the European level, explaining how EU rules are driving mass litigation and why Ireland should respond by supporting a well-designed EU regulation of TPLF. Finally, Chapter 7 presents the main conclusions.

[1] S.I. No. 181 of 2024. Available at: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2024/si/181/made/en/pdf Note that the implementing legislation applies to representative actions initiated on or after June 25, 2023.

[2] This possibility is illustrated in Michael Scully v. Coucal Limited [2025] IESC 20. The case shows the willingness of Irish courts to accept the enforcement of judgements with cross-border and third-party funding elements. See Section 6 for further details on the case. Judgment available here: https://www.courts.ie/acc/alfresco/7024fc68-0cbc-48d0-95d5-f4e84165b805/2025_IESC_20_CJ.pdf/pdf#view=fitH;; also see: Addleshaw Goddard. Third Party Funding Considered by the Irish Supreme Court. Available at: https://www.addleshawgoddard.com/en/insights/insights-briefings/2025/dispute-resolution/third-party-funding-reconsidered-by-the-irish-supreme-court/

2. Private and Public Regulatory Enforcement in Ireland

2.1 Private Regulatory Enforcement

2.1.1 Collective Actions

Private enforcement of regulation occurs when individuals or groups take the initiative to bring cases before the courts. For example, consumers may sue companies whose products fail to meet regulatory standards and cause harm, either in tort or under the Liability for Defective Products Act 1991. When regulatory breaches affect multiple consumers in similar ways, they may seek redress collectively through the courts. These are commonly referred to as mass litigation or class or collective actions.

Prior to the transposition of the RAD, Ireland did not have a formal collective actions regime. A limited form of representative litigation existed but it remains restricted in scope and rarely used. Order 15, Rule 9 of the Rules of the Superior Courts 1986 allows one or more individuals to sue or be sued on behalf of others who share the “same interest” in a matter; however, the requirement of “same interest” has been interpreted strictly by the courts, limiting its applicability to cases where the factual and legal issues are virtually identical across all parties.

Importantly, the Supreme Court has declined to extend representative procedures to actions based in tort,[1] such as personal injury or negligence, and Order 15 does not permit the recovery of damages, limiting its use to claims seeking injunctive or declaratory relief[2] such as statements by the court to clarify a party’s legal rights or status.[3] In addition, there is no provision for civil legal aid in representative actions,[4] thereby precluding collective legal representation through the state-funded legal aid system.

In the absence of a comprehensive collective redress framework, claimants in Ireland have traditionally relied on ad hoc mechanisms to address mass harm or group grievances. One such method is the use of test cases where a single claimant is selected to litigate issues that are representative of a broader group of similarly affected individuals. Although the outcome of a test case can serve as a persuasive precedent for related claims, it is not legally binding on other proceedings and does not ensure uniformity of outcomes.[5] The Irish Law Reform Commission (LRC) and the Civil Justice Review have highlighted these and other limitations of test cases in several reports.[6]

In 2024, Ireland transposed the RAD through the Representative Actions for the Protection of the Collective Interests of Consumers Act.[7] Under this new framework both domestic and cross-border actions may be brought by qualified entities (QEs) designated by the Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment provided they meet the criteria set out in the RAD for cross-border representation.[8] These QEs are empowered to seek injunctive relief and/or redress measures in response to infringements of consumer protection laws listed in the RAD.[9] QEs are permitted to charge a fee, currently capped at €25 per consumer per legal action. Furthermore, consumers must opt in to be represented in such actions seeking redress. However, where an action seeks injunctive relief only, no opt-in is required.

Finally, all collective settlements involving redress are subject to court approval and all representative actions initiated under the Act will be published in the Register of Representative Actions.[10] The High Court of Ireland recently granted the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL)[11] permission to bring the first representative action under the new regime. The case targets Microsoft’s online advertising practices due to alleged breach of data protection and privacy rights under EU law.[12]

2.1.2 Alternative Dispute Resolution

While collective actions are a relatively new phenomenon in Ireland, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) processes are much more established. Mediation and conciliation have long been part of Irish statutory frameworks, covering areas ranging from industrial relations to commercial litigation, as well as private disputes between citizens.

In fact, it is now a mandatory requirement for lawyers to advise their clients in writing that mediation is available and should be considered as an option for resolving disputes. Mediation is also treated as a precondition to litigation in many cases, and even once litigation has commenced, parties are encouraged to explore mediation at any stage of the proceedings.[13] The High Court of Ireland has imposed costs penalties on parties where solicitors failed to comply with their statutory duty to advise clients, before commencing proceedings, about the availability and potential benefits of mediation.

The recently enacted Courts and Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2023 amended the Arbitration Act 2010 by inserting a new section 5A which explicitly provides that the offences and torts of maintenance and champerty do not apply to international commercial arbitration, to any proceedings arising out of such arbitration, or to any mediation or conciliation proceedings connected to it, although such amendments are yet to commence.

2.2 Public Regulatory Enforcement

2.2.1 The Role of Regulators

As in most EU countries, Ireland uses a public enforcement model where norms and regulations are specific and prescriptive, setting out what companies can and cannot do and the steps to be followed to achieve regulatory compliance. Irish regulatory authorities actively monitor markets for potential safety issues or infringements and enforce the rules rigorously.

The powers of these regulatory authorities have been strengthened over time. Since 2018, sectoral economic regulators have been granted financial sanctioning powers, enabling bodies such as the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI), the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (CCPC), the Commission for Communications Regulation (ComReg) and the Data Protection Commission (DPC) to impose substantial fines and, where appropriate, compel the establishment of redress schemes. Furthermore, the Consumer Rights Act 2022, Section 137, authorised some of these regulators, including consumer organisations,[14] to apply to the courts for a declaration that a specific contractual term is unfair. Finally, the CCPC has extensive powers under the Consumer Protection Act 2007 and the Competition and Consumer Protection Act 2014 to obtain prohibition orders or prosecution for criminal offences in order to enforce compliance. In 2023, more than 35,000 individuals contacted the CCPC helpline seeking advice on consumer rights and personal finance while its website recorded more than 2.4 million visits, a very significant number given Ireland’s population of 5.38 million people.[15]

There are several examples where Irish authorities have addressed and resolved regulatory breaches that, in other jurisdictions that rely on private enforcement, would have been resolved through the courts. For example, the CBI forced banks to pay compensation and legal costs to tens of thousands of customers affected by the tracker mortgage scandal, imposing sanctions amounting to a total of €272 million.[16]

Other examples come from the Irish DPC. Given the importance of Ireland as a base for multinational ICT companies, as we will see in Chapter 4 – the Irish regulator has a key role to play not just for the protection of personal data in Ireland but in the EU too.[17] As an example, in 2024, the DPC concluded an inquiry into whether Meta had complied with its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) obligations concerning personal data breaches and the secure processing of user passwords. The DPC found that Meta had infringed Articles 33(1) and 33(5) of the GDPR by failing to notify the DPC of a personal data breach and by failing to adequately document the incidents involving the storage of passwords in plaintext. Additionally, the DPC found violations of Articles 5(1)(f) and 32(1), determining that Meta had failed to implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure the security of users’ passwords. As a result, the DPC issued a reprimand and imposed administrative fines totalling €91 million.

Similarly, an inquiry was launched against LinkedIn to assess the lawfulness, fairness, and transparency of its processing of personal data belonging to EU/EEA members for the purposes of behavioural analysis and targeted advertising. The inquiry was initiated in August 2018 following a complaint filed by the French NGO La Quadrature du Net on behalf of affected data subjects under the procedure outlined in Article 80(1) of the GDPR. In its Final Decision, the DPC found that LinkedIn had infringed Articles 5(1)(a), 6(1), 13(1)(c), and 14(1)(c) of the GDPR. As a result, the DPC issued a reprimand, ordered LinkedIn to bring its processing operations into compliance, and imposed administrative fines totalling €310 million.

In a separate case, the DPC commenced an own-initiative inquiry in September 2024 into Google’s processing of personal data associated with the development of its foundational AI model, Pathways Language Model 2 (PaLM2). The inquiry is focused on whether Google fulfilled its obligations under Article 35 of the GDPR and specifically the requirement to conduct a data protection impact assessment prior to initiating the processing of personal data.[18]

2.2.2 The Role of Ombuds Bodies

Regulators are not the only institutions that are responsible for ensuring compliance with consumer protection rules in Ireland. Ombuds bodies also play a part.[19] It can be argued that Ombuds bodies provide a middle ground between the private and public approaches to regulatory enforcement by leveraging the deterrent power of public enforcement while also enabling consumers and businesses to seek redress for specific grievances.

Irish Ombuds bodies such as the Financial Services and Pensions Ombudsman (FSPO) and the Office of the Ombudsman have discretion to use a range of informal resolution methods, including conciliation and mediation, to address individual complaints. Where informal resolution is unsuccessful, these bodies may initiate a formal investigation and issue either a recommendation or a binding decision, depending on their statutory mandate.[20] They are not designed for delivering large-scale collective redress; however, these schemes can potentially respond to systemic issues when multiple complaints highlight broader patterns of misconduct or maladministration.

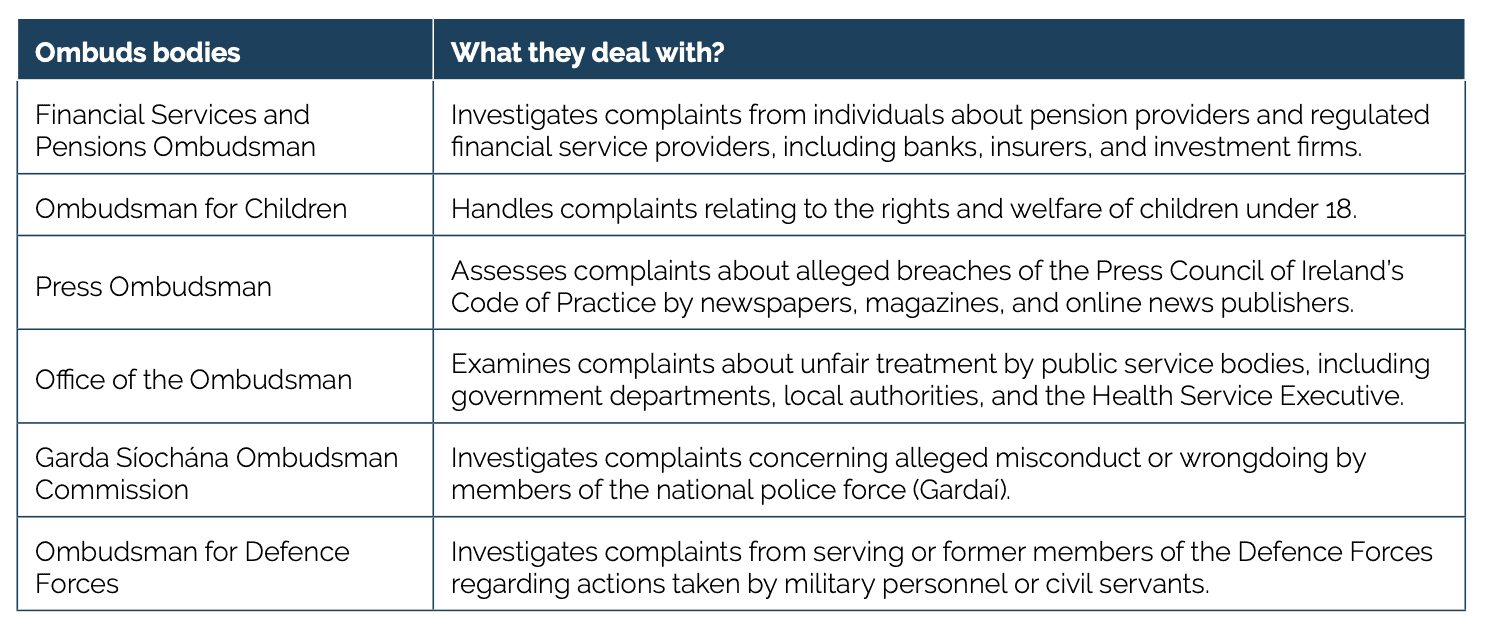

For example, the FSPO resolves around 2,000 complaints per year[21] and, on average, it issues close to 400 legally binding decisions of which around half are upheld fully or partly in favour of the complainant.[22] Examples of complaints that are handled include disputes over interest rates, the assessed value of stolen property, and the rejection of insurance claims. The table below presents a list of Irish Ombuds bodies in different sectors and areas of public policy.

Table 1: Irish Ombuds bodies Source: Citizens Information

Source: Citizens Information

2.3 Consumer Protection in Ireland

It could be argued that the absence of strong private enforcement leaves Irish consumers worse off than in other EU countries where mass litigation is more common. However, this does not appear to be the case. According to the European Commission, nearly eight in ten Irish consumers believe that retailers and service providers respect their consumer rights, above the EU average of 70 percent. Similarly, 72 percent trust public authorities to protect their rights, compared to an EU average of 61 percent.[23] The same survey assessed individuals’ knowledge of consumer rights. Ireland had the highest number of households with a medium level of knowledge and ranked 11th in terms of households with a high level of knowledge across the EU.

Moreover, Irish consumers do not receive lower quality goods and services than the EU average. On the contrary, they often fare better. When asked whether they had experienced any problems when buying or using goods or services, 76 percent of Irish households said no, 22 percent said yes, and 2 percent were unsure. These results closely match the EU average, where 76 percent reported no problems and 24 percent did. Only 13 percent of Irish consumers believed that a significant number of non-food products were unsafe, one of the lowest figures in the EU, compared to the EU average of 24 percent. At the same time, Ireland had the highest percentage of households receiving a recall notice for a product purchased in the previous two years (22 percent, compared to the EU average of 13 percent), suggesting that when problems do arise, producers in Ireland are proactive in taking responsibility.

When problems did occur, most EU citizens, including those in Ireland, complained directly to the retailer or service provider. However, Irish consumers stand out for being more likely than their EU peers to bring complaints to public authorities. Among Irish households that experienced a problem when buying goods or services, 28 percent reported it to a public authority, almost double the EU average of 15 percent. In addition, 11 percent of Irish households turned to an out-of-court dispute resolution body, such as an Ombuds body, compared to 9 percent across the EU. This route appears to be relatively satisfactory, with 54 percent of Irish respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that it was easy to settle disputes through such bodies, above the EU average of 46 percent. With the transposition of the RAD, however, the balance may shift. Chapter 5 shows that collective actions carry the risk of imposing additional litigation and compliance costs without necessarily delivering meaningful compensation to individuals.

[1] Moore v Attorney General (No 2) [1930] IR 471

[2] Injunctions refers to court orders to stop or require certain actions while declaratory relief refers to statements by the court clarifying legal rights or status.

[3] This limitation is reinforced by Order 6, Rule 10 of the Circuit Court Rules 2001, which clearly states that the Circuit Court will not hear any representative actions involving tort law.

[4] Section 28(9)(a)(ix) of the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995 excludes from the scope of legal aid any application “made by or on behalf of a person who is a member, and acting on behalf of, a group of persons having the same interest in the proceedings concerned”.

[5] For example, in Cotter and McDermott v Minister for Social Welfare (No. 1 ([1987] ECR 1453) and No. 2 ([1991] 1 ECR 1155)), test cases were brought on behalf of approximately 11,200 litigants. The European Court of Justice held that the 1978 Directive, which mandates equal treatment in social security matters had direct effect, entitling the claimants, married women, to the same payments as married men from December 1984. The cases were settled without admission of liability, resolving 2,700 similar pending claims, but leaving about 8,500 additional claims to be addressed, along with approximately 58,000 married women who had not yet initiated proceedings.

[6] LRC. (2005). Report Multi-Party Litigation. Available at: https://www.lawreform.ie/_fileupload/reports/report%20multi-party%20litigation.pdf;

Civil Justice Review. (2020). Review of The Administration of Civil Justice Report. Available at: https://www.civiljusticereview.ie/en/CJRG/04112020%20FINAL%20REPORT%20WEB1.pdf/Files/04112020%20FINAL%20REPORT%20WEB1.pdf

[7] S.I. No. 181 of 2024. Available at: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2024/si/181/made/en/pdf Note that the implementing legislation applies to representative actions initiated on or after June 25, 2023.

[8] RAD Article 6 lists four conditions: advance designation; cross-border recognition; proof of standing; and cross-border harm.

[9] See RAD Annex 1 which includes a list of 66 EU directives and regulations cover under RAD.

[10] Pinsent Masons. (June 6, 2024). Ireland’s mass actions law ‘significant development’ for consumer protection. Available at: https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/ireland-mass-actions-law-consumer-protection ; Houthoff. (2024) Houthoff Class Action Survey: Ireland. Available at: https://www.houthoff.com/insights/firm-news/houthoff-class-action-survey-2024/ Department of Enterprise, Tourism and Employment. Register of Representative Actions. Available at: https://enterprise.gov.ie/en/publications/register-of-representative-actions.html

[11] The Irish ICCL reported in its 2023 Annual Report that the majority of its funding derives from charitable trusts and foundations committed to advancing human rights and civil liberties.

[12] The litigants claimed that Microsoft’s Real-Time Bidding (RTB) digital advertising process in which online ad space is bought and sold through automated auctions that occur in real time as a user loads a webpage or app exposes highly sensitive personal data to advertisers. Source: ICCL. (2025, May 26). ICCL secures permission to take Ireland’s first ever class action. Available at: https://www.iccl.ie/news/iccl-secures-permission-to-take-irelands-first-ever-class-action/

[13] Influential reports such as the Wolff and the Kelly Reports, emphasised that court proceedings should be regarded as a last resort and that ADR should be pursued both before and after the commencement of proceedings in order to facilitate early settlement.

[14] The 1995 Regulations with S.I. No. 27/1995 – European Communities (Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts) Regulations, 1995.

[15] CCPC. (2024, March 15). Almost 40,000 people contacted Irish consumer helpline in 2023. Available at: https://www.ccpc.ie/business/almost-40000-people-contacted-irish-consumer-helpline-in-2023/ ; also see: CCPC. (2024). Understanding Consumer Detriment in Ireland. Available at: https://www.ccpc.ie/business/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/02/CCPC-Understanding-Consumer-Detriment-in-Ireland.pdf

[16] Pinsent Masons. (2025, February 26). Irish tracker mortgage inquiry highlights focus on individual accountability. Available at: https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/irish-tracker-mortgage-inquiry-individual-accountability

[17] Under the “One-Stop Shop” regime introduced by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018, the Irish Data Protection Commissioner (DPC) has become the key EU regulator in this field for several leading US tech firms.

[18] The High Court, in its judgment dated October 11, 2024 gave parties two weeks to file brief written submissions on the terms of the final order, on costs, and on any other matters arising. The matter was then listed for mention on November 5, 2024, for the purpose of making final orders, but no official updates appear to have been recorded since. Record No. H.JR.2024/81 [2024] IEHC 577.

[19] The term Ombuds body is used instead of Ombudsman, as a gender-neutral alternative.

[20] For example, under Section 62 of the Financial Services and Pensions Ombudsman Act 2017, the FSPO has the power to publish legally binding decisions in relation to complaints concerning financial service providers.

[21] In 2018 and 2019, FSPO resolved 2,300 and 2,160 complaints respectively. FSPO. Ombudsman’s Digest of Legally Binding Decisions Volume 1. Available at: https://www.fspo.ie/documents/Ombudsmans_Digest_of_Decisions_Vol1.pdf?v=2.0 and Volume 2. Available at: https://www.fspo.ie/documents/Ombudsmans_Digest_of_Decisions_Vol2.pdf?v=2.0f

[22] Ibid.

[23] Data presented in this section was sourced from the European Commission 2024 Consumer conditions survey. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/2024-consumer-conditions-survey-presentations_en

3. Third-Party Litigation Funding in Ireland

Litigation in Ireland is expensive. The World Bank estimates that, as a percentage of the claim value, attorney fees in Ireland are among the highest in the EU.[1] Moreover, Ireland operates under a “costs follow the event” rule meaning that a losing party may be liable not only for their own legal fees but also for those of the opposing side, substantially increasing their financial exposure. In this context, TPLF[2] has the potential to provide the necessary capital to finance collective actions which can be particularly costly, facilitating access to the courts for those claimants who cannot afford to self-fund.

However, TPLF remains prohibited under long-standing common law doctrines of maintenance and champerty that prohibit parties with no legitimate or independent interest in a legal dispute from funding litigation.[3] The legal status of TPLF was tested in the case of Persona Digital Telephony Ltd v Minister for Public Enterprise [2017] IESC 27. In this case, the claimants had entered into a TPLF agreement to fund their litigation against the Minister. However, the agreement was challenged on the grounds that it violated the rules against maintenance and champerty. The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the prohibition. Therefore, as it stands, Irish law continues to prohibit third-party funding in civil proceedings, unless the funder is directly connected to the dispute.[4]

Reform to allow TPLF in Ireland has been considered following the publication of the LRC’s consultation paper, Third-Party Litigation Funding, in July 2023.[5] Moreover, Section 27 of the Representative Actions for the Protection of the Collective Interests of Consumers Act 2023 implements Article 10 of the RAD, which provides a framework for the regulation of TPLF. This means that if TPLF is ultimately made lawful in Ireland, its operation will be subject to regulation in accordance with the standards set out in the RAD.

The LRC identified three possible approaches for legalising TPLF in Ireland.[6] The first is the preservation model, followed in England and Wales, which no longer recognises the torts of maintenance and champerty but retains their underlying public policy concerns.[7] The second option is the abolition model, which would entirely remove maintenance and champerty from the legal system. The third option is the legalisation model, where torts of maintenance and champerty are kept but the law explicitly states that third-party funding will become a statutory exception to the general ban on maintenance and champerty. Importantly, and as described in Section 2.1.2, Ireland has already moved in this direction: the Courts and Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2023 amended the Arbitration Act 2010 by the insertion of Section 5A, which now permits third-party funding in international arbitration,[8] albeit the permission is yet to commence. Moreover, the Third-Party Funding Contracts (Certain Proceedings) Bill 2024 proposes to permit third-party funding of certain insolvency proceedings. The Bill also provides for Ministerial regulations to prescribe criteria for funding contracts, particularly in relation to transparency requirements for both funders and recipients.

The LRC also proposed five potential frameworks to regulate TPLF in Ireland. The first is a voluntary self-regulation model which would allow litigation funding companies (LFCs) full autonomy to regulate themselves. The second option is an “enforced self-regulation” model under which a representative body appointed by the LFCs would be empowered to establish codes of practice and industry rules. The third approach involves court certification, requiring each third-party funding agreement to be approved by a court before becoming binding. The fourth model proposes assigning regulatory responsibility to an existing body, such as the CBI. Lastly, the creation of a new, dedicated regulator is also suggested as a way to ensure focused and specialised oversight of the TPLF industry.

[1] World Bank (2020), Doing Business in Europe. Available at: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Profiles/Regional/DB2020/EU.pdf

[2] According to the LRC, TPLF refers to an arrangement where an entity that is not a party to the legal dispute, nor an affiliate, nor a legal practitioner acting for one provides financial support to cover part or all of the legal costs. This funding is typically offered in exchange for a share of any proceeds. Law Reform Commission, Third-Party Litigation Funding (LRC CP 69 – 2023), Available at https://www.lawreform.ie/_fileupload/consultation%20papers/lrc-cp-69-2023-third-party-funding-full-text.pdf

[3] The Irish courts have consistently held that the mere provision of financial support for litigation by a party with no legitimate interest in the proceedings constitutes unlawful maintenance. Furthermore, where such financial support is provided in exchange for a share of any damages recovered, it constitutes champerty, which remains both a tort and a criminal offence under Irish law.

[4] While TPLF remains generally unlawful in Ireland, several recognised exceptions have emerged. These include: (1) the tentative recognition of TPLF in international arbitration and related court proceedings under section 5A of the Arbitration Act 2010 (as inserted by section 124 of the Courts and Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2023); (2) possible court-approved TPLF under the Representative Actions for the Protection of the Collective Interests of Consumers Act 2023 (which implements Directive (EU) 2020/1828); (3) funding by immediate family, community groups, trade unions, and others falling within the common law “charity” exception; (4) before-the-event (BTE) legal expenses insurance, including Directors and Officers (D&O) insurance; (5) after-the-event (ATE) legal expenses insurance; (6) subrogation rights of insurers; (7) pro bono legal services; (8) deferred fee arrangements by legal practitioners under the Legal Services Regulation Act 2015; (9) regulator-ordered legal assistance, such as under the Central Bank’s tracker mortgage redress schemes; (10) amicus curiae interventions; (11) certain assignments of debts and other choses in action, though not bare rights to litigate; and (12) state-funded legal aid under both statutory and non-statutory schemes.

[5] Law Reform Commission, Third-Party Litigation Funding (LRC CP 69 – 2023), Available at https://www.lawreform.ie/_fileupload/consultation%20papers/lrc-cp-69-2023-third-party-funding-full-text.pdf

[6] See, for example, the submission of the Law Society to the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Justice and Equality, 27 November 2019; Corbett, “Third-Party Litigation Funding – Time for a Rethink?” (2023) 69 Irish Jurist 12.; see, for example, Dáil Éireann Debates 31 January 2017 question 3969/17; See, for example, the submission of FLAC to the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Justice and Equality, 27 November 2019 and see, for example, the submissions to the public consultation run by the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment on the transposition of Directive (EU) 2020/1828. The different models as proposed operate in many common law jurisdictions.

[7] Law Commission of England and Wales, Proposals for Reform of the Law Relating to Maintenance and Champerty (LC 0071966). The Law Commission’s 1996 Report contained draft statutory provisions, which formed the basis for sections 13 and 14 of the English Criminal Law Act 1967.

[8] Section 124. The Arbitration Act 2010 is amended by the insertion of the following section after section 5: 5A. (1) This section applies to dispute resolution proceedings. (2) The offences and torts of maintenance and champerty do not apply to dispute resolution proceedings. (3) A third-party funding contract that meets the criteria (if any) prescribed under subsection (4) shall not, insofar as it relates to dispute resolution proceedings, be treated as contrary to public policy or otherwise illegal or void. (4) The Minister may, for the purposes of subsection (3), by regulation prescribe criteria, including criteria relating to transparency in relation to funders and recipients, for third-party funding contracts.

4. Why Ireland Faces a Unique Threat from Mass Litigation

4.1 The Irish Legal System

If Ireland were to ease its current restrictions on TPLF it could experience a disproportionately greater rise in collective action cases than any other EU member state. This is because the Irish legal system offers a unique combination of common law procedural tools, EU legal alignment, cross-border enforceability, and English-language litigation.[1]

Firstly, judgments issued in Ireland are automatically recognised and enforceable across all EU member states under the Brussels I Recast Regulation. This is particularly relevant for collective actions that frequently involve systemic breaches of EU consumer or product safety rules affecting claimants across several jurisdictions. Secondly, a significant share of mass litigation in the EU has been shaped by practices imported from the US.[2] Because Ireland shares the same underlying legal tradition as the US, it may be seen as more receptive to new cases and novel claims, particularly if there is a relaxation of the rules governing mass litigation and TPLF.

Finally, the broad disclosure provisions under Irish law, which require parties to share a wide range of documents and evidence with the opposing side before the trial begins, significantly enhance the likelihood of starting a collective action in Ireland. In addition, Section 34 of the Protection of the Collective Interests of Consumers Act 2023 introduces a mechanism specifically designed for collective actions. It allows courts, at the request of a QE, to order the disclosure of relevant evidence held by the defendant.[3] This statutory right strengthens the position of QEs by enabling them to build more robust claims, increasing the likelihood of early-stage success, and again, positioning Ireland as an attractive environment for initiating this type of litigation.[4]

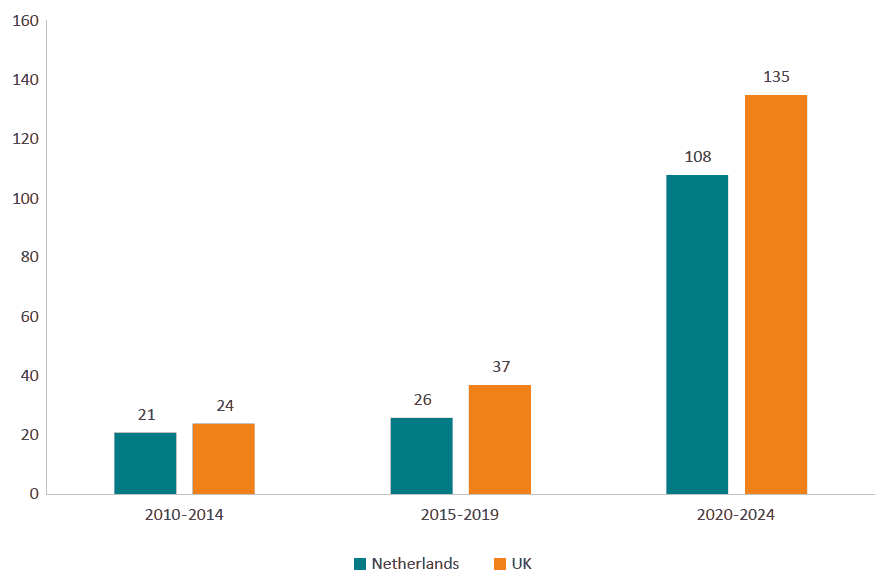

The experience of other countries offers a cautionary tale of what can happen if the conditions for launching collective actions and granting access to TPLF become too favourable. Figure 1 shows the number of collective actions in the Netherlands and the UK across five-year periods from 2010 to 2024. Both countries record a sharp increase in collective actions during 2020-2024. This is no coincidence but stems directly from legislative changes in both countries and subsequent court rulings. In 2020, the Netherlands passed the Collective Actions for Mass Damages Act (WAMCA), which empowered ad hoc entities to seek compensation on behalf of consumers for breaches of a broad range of laws.[5] In the UK,[6] the Supreme Court lowered the threshold for collective action certification in 2020, while Collective Proceeding Orders were introduced in 2021, creating a framework for collective redress in competition law cases[7]. Similar dynamics have been also observed in other jurisdictions such as the US and Australia, where rapid growth in TPLF followed regulatory reforms that opened these markets to litigation funders.[8]

Figure 1: Number of collective action cases in the Netherlands and the UK, 2010-2024 Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

4.2 The Irish Economic Model

Beyond legal considerations, there are economic factors, specific to Ireland that heighten its exposure to mass litigation. Ireland’s successful economic model is closely tied to US FDI, particularly in the ICT and life sciences sectors both of which are increasingly targeted by collective actions.

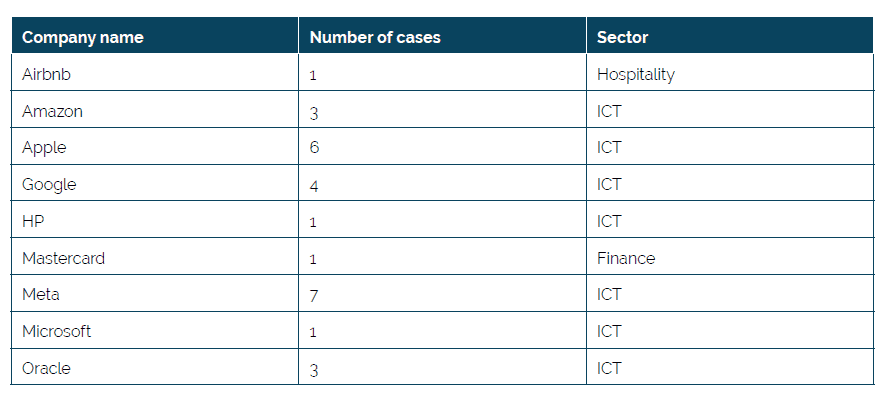

Across a database of 469 collective action cases recorded in EU countries between 2008 and 2025,[9] 40 involved US companies. Of these, 27 concern firms that operate their European businesses from Ireland. Examples include Meta’s international headquarters, Mastercard’s European Technology Hub, Google’s European headquarters, Airbnb’s international base in Dublin, and Apple’s European headquarters in Cork. As this list suggests, most of the cases involve companies in the ICT sector. The following table lists US companies in our database that have faced collective actions in the EU and have major operations office located in Ireland. It also shows the number of cases linked to each company and the sector in which they operate.

Table 2: US companies with headquarters in Ireland that are involved as defendant in collective litigation in the EU, 2008-2025 Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

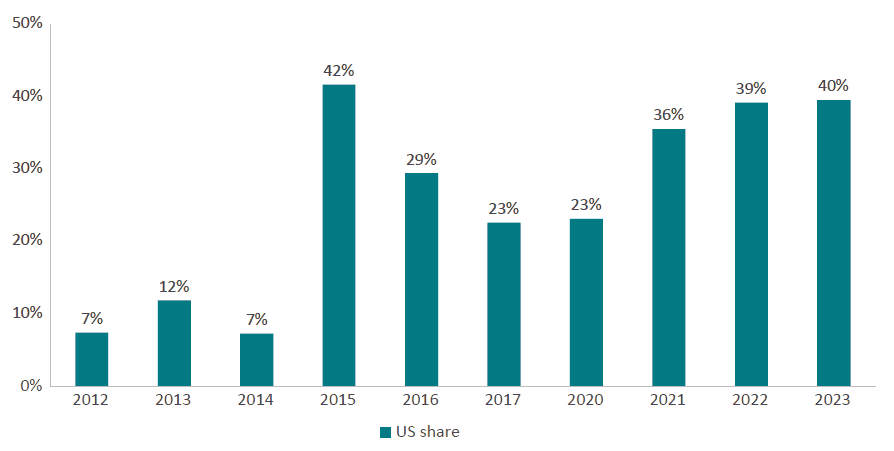

The number of cases brought against US companies is highly relevant to Ireland given the economy’s reliance on US-led FDI. Between 2012 and 2023, Ireland’s FDI stock surged from €290 billion to €1.3 trillion, far outpacing the country’s GDP growth.[10] US companies were a major driver of this increase. As shown in Figure 2, US companies accounted for 40 percent of Ireland’s total FDI stock in 2023, up sharply from just 7 percent in 2012.

Figure 2: Share of US FDI stock in Ireland, 2012-2023 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Ireland Central Statistics Office. Data for 2018 and 2019 are unavailable.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Ireland Central Statistics Office. Data for 2018 and 2019 are unavailable.

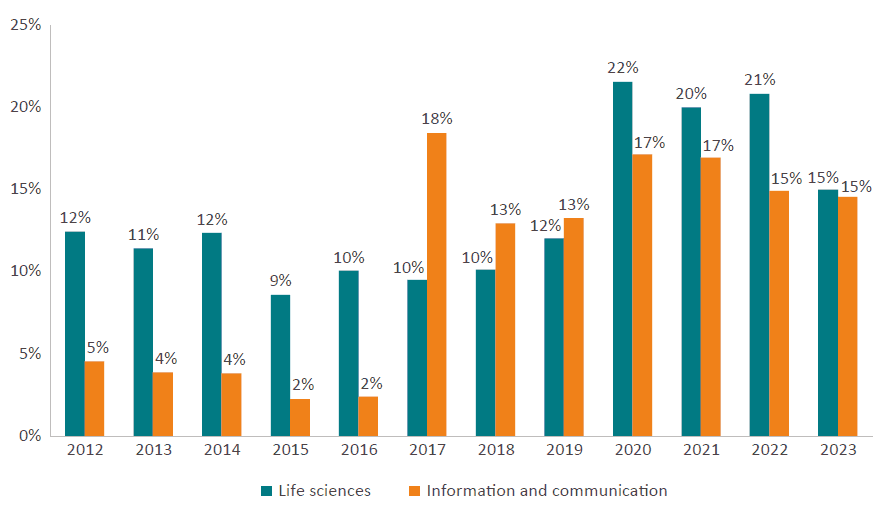

The sectoral breakdown of Ireland’s FDI stock further underscores its exposure to mass litigation. As shown in Figure 3, the life sciences and ICT sectors accounted for 30 percent of inward FDI in 2023, and their share of total investment has steadily grown over the past decade.

Figure 3: Share of FDI stock in life sciences and ICT in Ireland, 2012-2023 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Ireland Central Statistics Office. Note: Life sciences refers to sector 21 – Basic pharmaceutical products and preparations; ICT corresponds to sector J – Information and Communication.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Ireland Central Statistics Office. Note: Life sciences refers to sector 21 – Basic pharmaceutical products and preparations; ICT corresponds to sector J – Information and Communication.

ICT and life sciences are particularly sensitive to mass litigation. Our database records a significant number of collective actions in Europe against companies operating in these two sectors.[11] Therefore, if Ireland were to make bringing collective claims easier, it is likely that old or new cases may appear in Irish courts too. The impact on the Irish economy will be more profound than for any other EU county. This is because the economic costs of a collective action in a country where the defendant company has little or no employment and investment are much more limited. As mass litigation worldwide increasingly impacts companies’ bottom lines, the negative effects on their growth and investments will be felt in the countries where these companies have placed their operations, including Ireland.

Moreover, the vitality of sectors such as life sciences and ICT is important not just for the companies and workers in these sectors but for the Irish economy as a whole since these sectors push up the average across several indicators of economic prosperity. For instance, in 2023, labour productivity in the ICT sector reached nearly three times the national average at €293 per hour compared to €106 per hour across the entire economy. [12] Between 2022 and 2023, the ICT sector was among the largest contributors to GDP growth, adding nearly €6.4 billion to Ireland’s economy. [13] [14]

This analysis highlights two important findings. First, companies with their headquarters or significant operations in Ireland have been targeted by collective actions not only in the US but also within the EU. Second, these companies make a significant contribution to Ireland’s economic prosperity. Irish policymakers should, therefore, carefully consider any relaxation of the rules governing mass litigation and TPLF, as such changes could make these types of legal actions more common. If that were to happen, as illustrated by the first collective claim brought in Ireland against Microsoft – it is likely that mass litigation targeting key sectors such as ICT and life sciences will become more frequent.

[1] NYSBA. (2021). Ireland for Law. Available at: https://nysba.org/ireland-for-law/?srsltid=AfmBOoqwyAafXxtvYZ_NYKsAhlwwl2K-A3o-Si-9e3oYuMKygU2aoYGa

[2] Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, 108 p.

[3] Similarly, courts may compel disclosure from a QE or third-party if required by the defendant.

[4] Disclosure is not a unique factor for Ireland; other EU countries such as Czech Republic also offer disclosure rules. However, the combination of a common law legal system and well-established discovery procedures is unique to Ireland in the EU.

[5] For more information on the Netherlands see Guinea, O., Pandya, D., & Sharma, V. (2025). Collective Action in the Netherlands: Why It Matters for the Transposition of the Product Liability Directive. ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 11/2025, 35 p. and Section 3.5 in Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, 108 p.

[6] CMS estimates that the cumulative value of collective actions in the UK reached €154.6 bn in 2024 up from €13.03 bn in 2016. CMS (2025). European Class Action Report 2025. Available at: https://cms.law/en/media/international/files/cms-european-class-action-report-2025?v=2

[7] Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., & Zilli, R. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in the UK. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 6/2025, 78 p. It is also important to note that the growth in the UK can be linked to the presence of opt-out mechanisms, which remain the dominant approach for mass litigation in England and Wales. Opt-out procedures are largely confined to competition law, where the number of cases has increased since 2016.

[8] See Legg, M. (2021). The Rise and Regulation of Litigation Funding in Australian Class Actions. Erasmus L. Rev., 14, 221 and Avraham, R., Sebok, A. J., & Shepherd, J. (2024). The WHAC-A-Mole game: An empirical analysis of the regulation of litigant third-party financing. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 25(2), 117-140.

[9] The database used in this Policy Brief is an updated version of Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, 108 p. For further details on the database see Annex 3 of that publication.

[10] Ireland Central Statistics Office, Foreign Direct Investment. Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/statistics/internationalaccounts/foreigndirectinvestment/

[11] Past cases of mass litigation in the ICT and life sciences sectors coincide with a rising trend of personal injury lawyers taking on data breach claims. See Loten, A. (2025, 3 September). More Personal Injury Lawyers Are Chasing Data-Breach Settlements. Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/more-personal-injury-lawyers-are-chasing-data-breach-settlements-39b2ec8c This development is particularly relevant for Ireland, after the Irish Supreme Court concluded that such claims constitute personal injury claims (see Dillon v. Irish Life IEHC 203). The Court clarified that claims for distress, upset and anxiety do not qualify as personal injury claims. As a result, claimants are not required to meet the higher threshold for personal injury litigation, where medical evidence and expert reports are typically necessary. The Supreme Court also noted that compensation for mental distress should remain modest. However, even relatively small awards in such cases can create significant exposure for companies, as a single incident may affect thousands or even millions of individuals. See Dentons. (2025, 31 July). Irish Supreme Court Removes Procedural Hurdle for Data Breach Claims: Are More “Mass Claims” on the Horizon? Available at: https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/articles/2025/july/31/irish-supreme-court-removes-procedural-hurdle-for-data-breach-claims Moreover, Article 82 of the GDPR provides that data subjects may claim compensation for both material and non-material loss resulting from a breach of data protection law by a data controller or processor.

[12] Ireland Central Statistics Office, Productivity in Ireland 2022–2023. Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-pii/productivityinireland2022-2023/labourproductivity/

[13] Ireland Central Statistics Office, Annual National Accounts 2023. Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-ana/annualnationalaccounts2023/gdpandgrowthrates/

[14] Business statistics for Ireland’s life sciences sector are not reported by the Central Statistics Office or Eurostat. However, sector 2, Basic pharmaceutical products and preparations, is included within the broader manufacturing category, and likely represents a significant share of it.

5. Costs and Benefits of Mass Litigation

5.1 Potential Economic Benefits from Increased Mass Litigation

A significant potential benefit of mass litigation is the compensation received by consumers. However, growing evidence suggests that most often the compensation is modest. This outcome is not accidental: it is inherent in two aspects of the model. First, mass litigation typically bundles a high number of low-value consumer claims, which means that even when successful, the individual payout is small. Second, the financial structure of these actions requires that a substantial share of the award is diverted to lawyers and funders before reaching consumers. Together, these features make modest compensation the norm rather than the exception.

The evidence confirms this conclusion. A study by the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that on average consumers are awarded US$ 32 in class actions cases while claimants’ lawyers take home nearly US$ 1 million.[1] Another study of class action settlements from 2019-2020 found that on average more than half of the compensation agreed in collective settlements went to attorneys or others who were not class members and, in some cases, the class members received less than 30 percent of the total monetary award.[2] These and other[3] studies indicate that in most instances the “winners” in the mass litigation system are the claimants’ lawyers and not the claimants themselves.[4]

The recent ruling in the Merricks v. Mastercard[5] case in the UK shows how high settlement amounts can underdeliver for claimants. The litigant sought redress from Mastercard’s breach of EU antitrust rules, covering an estimated 46.2 million consumers.[6] After 10 years of costly litigation, £100 million was finally awarded as compensation, leaving claimants with up to £70 each if only 5 percent claim but as little as £2.50 each if the full class of 44 million people comes forward.[7] About £46 million will go to the litigation funder that financed the claim, with a further £54 million payable as a return on the funds, depending on how many people ultimately come forward to submit a claim. The legal team representing Mr. Merricks has billed more than £18.1 million while the legal costs incurred by Mastercard have not been disclosed but they are likely to be significantly higher.[8]

It is also worth noting that the initial claim was for an amount in the range of £16.7 billion,[9] whereas the final award, £100 million, is a fraction of that figure. In this context, the outcome highlights the limited compensation ultimately achieved for the claimants, especially when compared with the substantial costs to both parties paid in legal fees and funder returns. Moreover, it is important to remember that these figures do not take account of the significant costs that collective action cases impose on public budgets, primarily through years of court time and related expenses such as the costs of shifting through vast numbers of claims to identify those with genuine merit, all of which are ultimately borne by taxpayers. This raises a broader concern about the efficiency of collective action proceedings, which often consume vast amounts of public and private resources while generating limited added value for consumers.

Another well-known example from the UK is the Post Office Horizon scandal.[10] In this case, the number of affected individuals was smaller but the story was the same. £46 million in legal fees and funders’ payments were deducted from a £57 million settlement, leaving a paltry sum of just over £20,000 per claimant, despite the seriousness of the injustice.

Other examples from the US present a similar picture. The US Company Thinx reached a settlement of up to $5 million in a class-action lawsuit concerning the safety claims of its intimate apparel products for which eligible consumers could receive just $7 per item (up to three items) or a 35 percent discount voucher.[11] In contrast, the legal fees amounted to $1.5 million.[12] Similarly, Mondelez’s $10 million settlement over misleading Wheat Thins labelling offered $4.50 per household without proof of purchase, and up to $20 with documentation.[13] The legal team stated they might take up to $3.3 million of this for their fees.[14] In the Apple Siri privacy case – where the total settlement reached $95 million – individuals were entitled to only $20 per device, capped at five devices.[15] In contrast, claimants’ lawyers will receive up to $28.5 million in legal fees, plus $1.1 million in other expenses.[16]

Moreover, as indicated in the Merricks case, it is not always guaranteed that all consumers receive the compensation since many of them may not claim what they owed. This was the case in a settlement in the Netherlands where so-called undistributed damages have been left sitting idle in escrow accounts.[17] The case involved the Swiss insurance company, Converium that became the subject of a securities class action in the Netherlands. Notably, the claimants seemed largely indifferent to the compensation that was awarded and an amount of €10 million was left unclaimed. This issue is not unique to the Netherlands. In the US, the opt‑out class action model means that very few class members come forward, either because they are unaware of the proceedings or because the individual compensation on offer is insignificant. As a result, funds remain held for long periods in escrow accounts instead of being put to productive use.

5.2 Potential Economic Costs from Increased Mass Litigation

5.2.1 Methodology

To assess the economic costs of mass litigation on the Irish economy, we apply a scenario-based methodology. Our methodology begins with a selection of variables based on a US literature review. These variables had to fulfil two conditions: first there had to be similar variables in Ireland to those used in the US studies, and second there had to be reliable statistical data available for them. The variables we selected are: litigation costs, costs of private enforcement as a share of GDP, and market capitalisation.

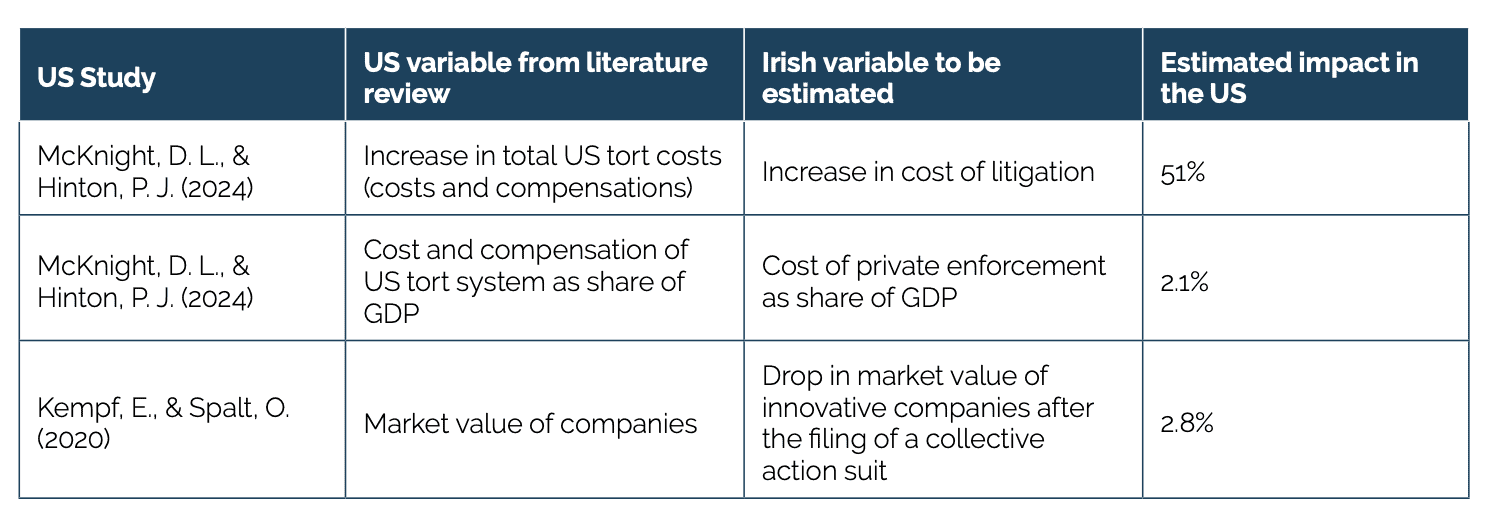

The next table presents these variables, the corresponding empirical study, the definition of the variable in that study, and an estimation of the impact.

Table 3: Variables affected by mass litigation Having identified these variables, the scenarios analysis assumes that if the Irish system of collective litigation were to resemble that of the US, the impact on the Irish economy would be proportional to the effects found in the US studies. Based on a comparison of the legal and institutional frameworks in Ireland and the US and on discussions with legal experts, we define three growth scenarios that equate to the degree to which the US and Irish mass litigation systems may converge, and as a result, the proportional effect on economic costs for Ireland.

Having identified these variables, the scenarios analysis assumes that if the Irish system of collective litigation were to resemble that of the US, the impact on the Irish economy would be proportional to the effects found in the US studies. Based on a comparison of the legal and institutional frameworks in Ireland and the US and on discussions with legal experts, we define three growth scenarios that equate to the degree to which the US and Irish mass litigation systems may converge, and as a result, the proportional effect on economic costs for Ireland.

- Low Growth Scenario: assumes that the economic impact of mass litigation growth in Ireland will be equivalent to 10 percent of the economic effects observed in empirical studies in the US.

- Medium Growth Scenario: assumes that the economic impact of mass litigation growth in Ireland will be equivalent to 20 percent of the economic effects observed in empirical studies in the US.

- High Growth Scenario: assumes that the economic impact of mass litigation growth the Ireland will be equivalent to 30 percent of the economic effects observed in empirical studies in the US.

Annex 1 includes a detailed explanation of the methodology and the calculations behind the results.

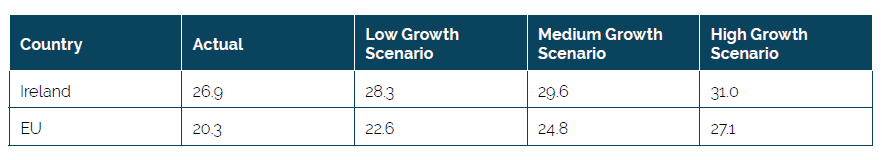

5.2.2 Litigation Costs

McKnight & Hinton found that tort costs in the US increased by 51 percent between 2016 and 2022.[18] For Ireland, this variable is taken from the World Bank, Doing Business in Europe (2020) report.[19] It measures the average of attorney costs (also mentioned in Chapter 3), court costs and enforcement costs as a share of claim value. The indicator focuses specifically on commercial litigation, including collective actions and non-collective actions. In 2020, it estimated that litigation costs in Ireland amounted to 26.9 percent of the claim value.[20]

However, the chosen variable includes a note of caution. The estimates for litigation costs from the McKnight & Hinton 2024 study not only include the costs of the tort system but also the compensation amounts. Meanwhile, the Irish estimate for this indicator only includes the litigation costs and not the compensation values. The McKnight & Hinton data for the US are the most recent and the most similar estimates we were able to find in an extensive literature review for this report.

We apply the 51 percent increase in US tort costs over time to the three scenarios for Ireland. The resulting estimates are 5.1, 10.2 and 15.3 percent (representing 10, 20, and 30 percent of the 51 percent figure respectively). Applying the projected growth rates of 5.1, 10.2, and 15.3 percent to the Irish value of 26.9 percent, litigation costs could reach 28.3, 29.6, and 31 percent of the claim value in the respective scenarios.

Table 4: Increase in litigation costs based on scenario-based analysis (percentage) Source: Author’s calculations based on World Bank, Doing Business in Europe (2020).

Source: Author’s calculations based on World Bank, Doing Business in Europe (2020).

These results are important. In 2020, Ireland already had the fourth highest litigation costs of all EU member countries, significantly above the EU average of 20.3 percent. If mass litigation increases according to either the low or medium growth scenarios, i.e., 28.3 percent or 29.6 percent, Ireland would have the third highest litigation costs in the EU, surpassing Italy.[21] If the increase reaches the level suggested in the high growth scenario, Ireland would have the second highest litigation costs in Europe, surpassing Sweden.

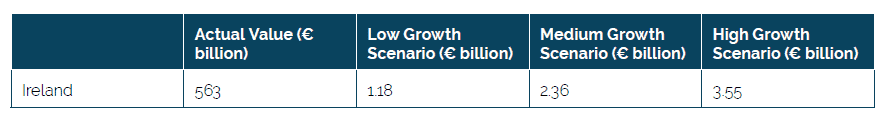

5.2.3 Private Enforcement Costs for Businesses

Table 5 estimates the cost of private enforcement as a share of Ireland’s GDP. It builds on the empirical estimates of McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024) mentioned earlier that found that in 2022 the total cost, including compensation awards, of the US tort system as a share of GDP was 2.1 percent.[22] 10, 20 and 30 percent of 2.1 is equal to 0.21, 0.42, and 0.63 percent respectively. Since Ireland’s GDP amounted to €563 billion in 2024, the cost of private enforcement for each of the three scenarios would be equal to €1.18 billion, €2.36 billion, and €3.55 billion respectively. To put these figures into perspective, the entire 2025 budget for infrastructure spending in Ireland was set at €3 billion

Table 5: Cost of private enforcement as a share of GDP under scenario analysis Source: Author’s calculations based on Eurostat data on GDP 2024.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Eurostat data on GDP 2024.

Moreover, using these estimates, a cost-benefit analysis for mass litigation can be built. A potential benefit of increased mass litigation could be growth in Ireland’s legal sector. In 2022, Ireland’s legal sector contributed €2.6 billion in value added to the economy. The scenario analysis suggests that increased mass litigation could impose additional costs on businesses, which could range from €1.18 billion €3.55 billion depending on the level of growth. To offset these costs, the economic size of the legal sector would need to expand by 45 and 137 percent, an unlikely prospect. Such large increases are not only improbable, but they would also divert significant future resources from other sectors of the economy. If those resources, such as labour and capital, are drawn from the most productive sectors – such as ICT and life sciences, as presented in Chapter 4 – overall labour productivity and economic prosperity in Ireland would likely decline.

5.2.4 Innovation Costs

Kempf & Spalt (2020)[23] found a direct and long-term negative effect of a 2.8 percent decline in the market valuation of companies targeted by a collective action lawsuit. This result helps identify a significant cost of mass litigation. Firstly, a fall in market capitalisation could undermine investor confidence and either lead to a pulling out of resources or a decrease in investment. Secondly, faced with the risk of mass litigation, firms may shift towards “safer” product development, reducing their appetite for bold R&D investment. This matters because radical innovation is a key engine of modern economic growth, especially in the ICT and life sciences sectors.

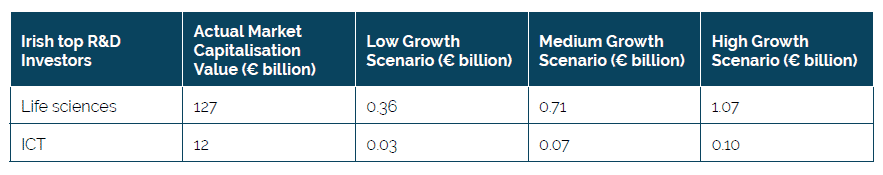

To quantify these risks, this section analyses the top R&D performers headquartered in Ireland based on the EU’s Joint Research Centre annual report that identifies the top 2,500 Research and Development (R&D) spending companies globally.[24] The report includes 24 Irish companies (see Annex 2 for a table listing these companies).[25] 24 companies out of a total of 2,500 might seem like a small number; however, the market capitalisation for these companies as a share of the market capitalisation of the top 2,500 companies globally amounted to 1.8 percent. Compared with Ireland’s 0.46 percent share of the world’s GDP,[26] 1.8 percent is a significant value.

We applied 10, 20, and 30 percent of Kempf & Spalt’s 2.8 percent finding to the aggregate market capitalisation of the 24 companies to produce estimates for the Low, Medium and High Growth Scenarios respectively. The results are shown in Table 6. The impact on the market capitalisation of those top 24 companies would reach €2.2 billion, €4.4 billion, and €6.6 billion respectively per scenario.

Table 6: Estimated fall in market capitalisation of the top 24 Irish R&D investors Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

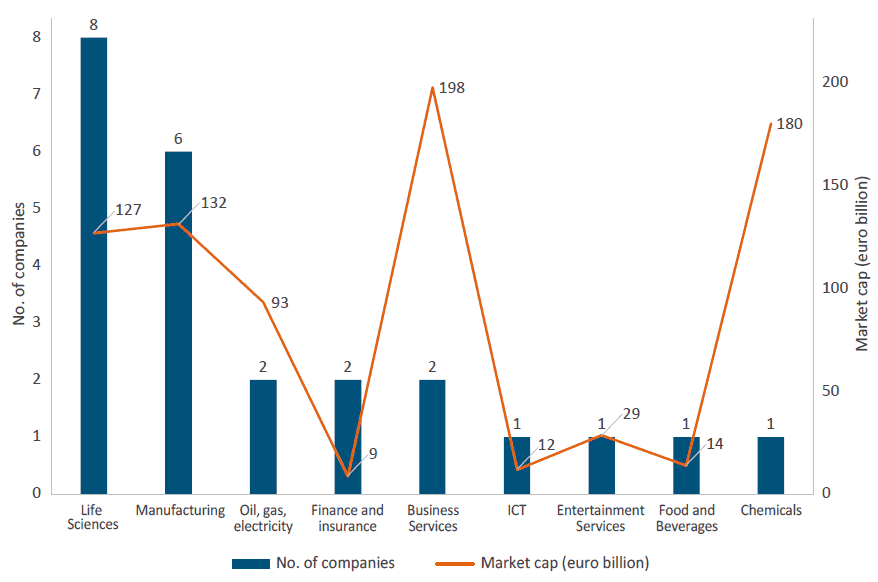

As explained in Chapter 4, the Irish life sciences and ICT sectors stand out as particularly vulnerable. Figure 4 shows that these sectors are especially important: nine of the 24 Irish most innovative companies belong to one of the two, eight in life sciences and one company in ICT. These companies had a market capitalisation of €138.8 billion, 17 percent of the total market capitalisation of the 24 Irish companies.

Figure 4: Market capitalisation of the top 24 Irish R&D investors, by sector Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Table 7 applies Kempf & Spalt’s estimate of a 2.8 percent drop in market capitalisation linked to mass litigation to the nine Irish companies in the life sciences and ICT sectors alone. The estimated loss in market capitalisation would reach €0.39 billion, €0.78 billion, and €1.17 billion, respectively, under each scenario.

Table 7: Estimated fall in market capitalisation of the top 9 Irish R&D investors in life sciences and ICT Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

The impact of mass litigation on publicly-listed companies extends beyond corporate boardrooms. In particular, it can affect savers. In 2024, Irish households saved 14 percent of their gross disposable income[27] and invested 15 percent of these savings in equity. While there is no public data on how much of these savings are invested in Irish-listed companies, it is likely that a significant share is held in domestic firms. This suggests that a fall in market capitalisation due to mass litigation could also negatively affect household savings.

[1] Consumer Fin. Protection Bureau, Arbitration Study: Report to Congress 2015, at section 6, p. 37 (2015), http://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/arbitration-study-report-to-congress-2015

[2] Jones Day, (2021). Update: An Empirical Analysis of Federal Consumer Fraud Class Action Settlements (2019-2020). Available at: https://www.jonesday.com/-/media/files/publications/2021/07/update-an-empirical-analysis-of-federal-consumer-fraud-class-action-settlements-(20192020)/files/an-empirical-analysis-of-federal-consumer-fraud-21/fileattachment/an-empirical-analysis-of-federal-consumer-fraud-2.pdf

[3] Kakalik, S. J. & Pace, M. N. (1986) Costs and Compensation Paid in Tort Litigation. RAND. The Institute for Civil Justice. Available at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2006/R3391.pdf

[4] Beisner, J. H. et al. (2022) Unfair, Inefficient, Unpredictable: Class Action Flaws and the Road to Reform. US Chamber of Commerce, Institute for Legal Reform. Available at: https://instituteforlegalreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ILR-Class-Action-Flaws-FINAL.pdf

[5] Walter Hugh Merricks CBE v Mastercard Incorporated and Others, (Competition Appeal Tribunal August 9, 2016). https://www.catribunal.org.uk/cases/12667716-walter-hugh-merricks-cbe

[6] Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., & Zilli, R. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in the UK. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 6/2025, 78 p.

[7] Ibid

[8] FCJ. (2025, February 25). Merricks-Mastercard Settlement Shows Real Winners from Class Actions. Available at: https://fairciviljustice.org/news/the-merricks-mastercard-settlement-shows-the-real-winners-from-class-actions/

[9] Global Legal Post. (2025, May 22). Merricks v Mastercard – landmark settlement or Pyrrhic victory? Available at: https://www.globallegalpost.com/news/merricks-v-mastercard-landmark-settlement-or-pyrrhic-victory-808734974

[10] Coleman, C. (2025, February 20). Post Office Horizon IT scandal: Progress of compensation. House of Lords Library; UK Parliament. Available at: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/post-office-horizon-it-scandal-progress-of-compensation/

[11] Treisman, R. (2023, January 19). Thinx settled a lawsuit over chemicals in its period underwear. Here’s what to know. NPR.org. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2023/01/19/1150023002/thinx-period-underwear-lawsuit-settlement

[12] Steinberg, J. (2023, February 27). Attorneys Seek $1.5 Million for Period Underwear PFAS Settlement. Bloomberg. Available at: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/litigation/attorneys-seek-1-5-million-for-period-underwear-pfas-settlement.

[13] Stempel, J. (2025, February 19). Wheat Thins purchasers settle with Mondelez over labeling. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/wheat-thins-purchasers-settle-with-mondelez-over-labeling-2025-02-19/

[14] Ibid.

[15] Cherruault, N. (2025, June 30). Apple Siri users to get one time check from $95m eavesdropping settlement – you only have hours to claim cash The US Sun. Available at: https://www.the-sun.com/money/14589768/apple-siri-users-settlement/

[16] Greene, J. (2025, January 7). What’s a consumer’s privacy worth? About $20. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/column-whats-consumers-privacy-worth-about-20-2025-01-06/

[17] Telegraaf. (2021). Door Pels Rijcken-topman beroofde claimstichting: ’we zijn genaaid’ Copy On Record. Also see: Bentham. (2014). Submission to the Ministry of Security and Justice Dutch Draft Bill on Redress of Mass Damages in a Collective Action.

[18] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024), Tort Costs in America: Third Edition. US Chambers of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform.

[19] World Bank (2020), Doing Business in Europe. Available at: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Profiles/Regional/DB2020/EU.pdf

[20] Ibid

[21] Litigation costs as a share of claim value across EU countries can be found in World Bank (2020), Doing Business in Europe. Available at: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Profiles/Regional/DB2020/EU.pdf

[22] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024), Tort Costs in America: Third Edition. US Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform. The study defines tort costs as the aggregate amount of judgments, settlements, and legal and administrative costs to adjudicate private claims and enforcement actions. The costs of the tort system also include the portion of liability insurance premiums used to pay administrative expenses and overheads and contribute to the profits of insurers.

[23] Kempf, E., & Spalt, O. (2020). Attracting the sharks: Corporate innovation and securities class action lawsuits. Management Science, 69(3), 1805-1834.

[24] Nindl, E., Confraria, H., Rentocchini, F., Napolitano, L., Georgakaki, A., Ince, E., Fako, P., Tuebke, A., Gavigan, J., Hernandez Guevara, H., Pinero Mira, P., Rueda Cantuche, J., Banacloche Sanchez, S., De Prato, G. and Calza, E., The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2024, doi:10.2760/506189, JRC135576

[25] The data was taken from the 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard which assigns geography to the country based on where a firm is headquartered.

[26] Global GDP value was taken from the IMF, GDP at current prices, accessed at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

[27] Eurostat. (2024, November). Households – statistics on income, saving and investment. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Households_-_statistics_on_income,_saving_and_investment

6. Regulating Third-Party Litigation Funding in Europe

6.1 The Europeanisation of Collective Actions

Even though several member states have long included some form of collective redress in their national legal systems, the EU has been keen to expand the availability of this type of procedure, in particular for consumers. The key driver that epitomises this shift is the RAD, discussed in Chapter 2, which requires all EU member states to introduce in their national laws collective redress mechanisms for consumer protection. It has compelled those countries with no previous group litigation framework, such as Ireland, to adopt entirely new procedures,[1] while encouraging others to reassess and modernise what they already have. In both cases, it has paved the way for a broader use of mass litigation in the EU.

A second driving force is the growing body of EU regulation that, directly or indirectly, encourages mass litigation. For instance, both the GDPR and the Digital Markets Act (DMA) explicitly support the bringing of collective actions. Article 80 of the GDPR allows certain organisations to bring claims on behalf of data subjects and the DMA enables collective actions under the RAD to be brought against gatekeepers that breach its provisions where such breaches harm the collective interests of consumers. More recently, the updated Product Liability Directive (PLD) expanded the range of issues that can be litigated and introduced other changes that tilt the balance of risks in favour of claimants (e.g., regarding the burden of proof), encouraging litigation against producers and other economic operators, including via collective actions.[2]

This expansion is significant because the EU, acting as a regulator, continues to introduce legal standards that broaden the scope of liability for companies doing business in Europe. In turn, this encourages claimants, particularly in collective actions, to test the boundaries of these new rules. It is then left to national courts to interpret them. This often results in diverging interpretations across EU countries that leads to fragmented case-law and legal uncertainty which hinders the deepening of the EU’s single market. Such fragmentation creates fertile ground for forum shopping as litigants seek to bring claims in those jurisdictions where courts are more receptive to collective actions or where litigation funding is available or that offer clearer procedural rules, or have a track record of claimant-friendly decisions.

For example, in Michael Scully v Coucal Limited, the Irish Supreme Court considered whether to enforce a Polish judgment under the Brussels I Recast Regulation even though the original case had been funded through TPLF (which remains prohibited in Ireland, as outlined in Chapter 3). The Court held that while Irish law prohibits assigning the right to sue to an unrelated third-party, it was nonetheless required to enforce the judgment as TPLF is legal under Polish law.[3]

6.2 Why the EU Should Regulate Third-Party Litigation Funding