Future-proofing the EU’s Investment Attractiveness: A Bold Reform Agenda for Competition Enforcement, Taxation and Digital Policy

Published By: Matthias Bauer Dyuti Pandya Oscar du Roy

Subjects: Digital Economy EU Single Market European Union

Summary

Reducing the deterrent effects from EU and Member State laws in three key cross-sector policy areas – competition policy, business taxes and VAT, and digital policies – could significantly enhance the business environment within the Single Market and boost the EU’s attractiveness to both domestic and foreign investors.

The EU’s future competitiveness is at risk due to a significant disparity in investments, particularly in technological innovation, compared to the US. Despite having a larger population and labour force, the EU lags behind in large business activities, with US firms consistently outspending their European counterparts in key tech-intensive sectors such as software, computer services, pharmaceuticals, and biotechnology. Moreover, China and other emerging nations are rapidly catching up, dramatically diminishing the EU’s relative economic and political influence on the global stage. The urgency for the EU to bridge these gaps is more critical than ever (Section 2).

The EU’s profound investment gap highlights a systemic advantage for the US in fostering innovation and economic growth. The EU’s regulatory complexity, largely driven by legal fragmentation in horizontal policies, further exacerbate the situation, deterring cross-border activities reducing the region’s attractiveness to global investors (Section 3).

EU Competition Policy in Support of Scale and Productivity

To enhance EU competition policy and reinforce productivity, the European Commission and national governments must distinguish between firms gaining market power through innovation versus firms engaging in anti-competitive practices, such as cartels. Harmonising competition enforcement across the EU will reduce compliance costs, foster a predictable business environment, and eliminate legal uncertainties, particularly critical for the digital economy’s growth. A risk-based prioritisation framework should allocate resources to high-impact cases, such as cartels, ensuring timely and effective enforcement.

Strengthening institutional capabilities of the European Commission and courts is vital to maintain market fairness without stifling large enterprises. Additionally, a balanced, evidence-based approach to mergers accounting for global markets and competition could better promote consumer welfare and market efficiency. Reducing regulatory protectionism and compliance costs across sectors will free up resources for innovation, driving a more dynamic and competitive market environment (Section 4).

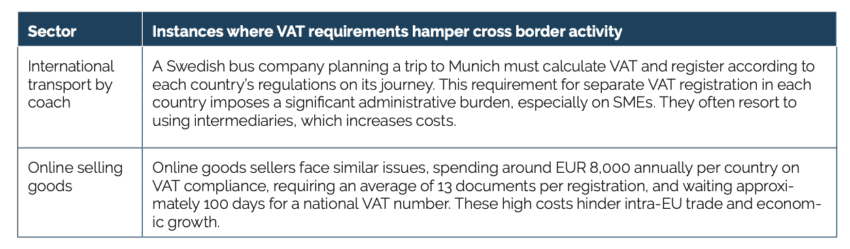

Reassessing Taxation in Support of Economic and Technological Change

The EU’s diverse VAT rates, labour income tax regimes, and social security rules create a complex legal environment that results in high compliance costs and administrative burdens, particularly for businesses operating across multiple Member States. This legal diversity encourages tax evasion, undermines government revenues, and distorts economic activities. Simplifying and harmonising tax and social security regimes would significantly reduce these costs and legal risks, making the EU more attractive for investments by businesses of all sizes. It would facilitate smoother cross-border operations, enhance competition, and reduce opportunities for tax avoidance, thereby fostering a fairer economic environment.

Given the significant drawbacks of the current corporate income tax (CIT) systems, there is a strong case for abolishing corporate income taxes in the EU. This move would simplify tax code compliance, reduce administrative burdens, and enhance the EU’s attractiveness for investment. To offset the relatively insignificant revenue loss, the EU could enhance other forms of taxation, such as taxes on capital income, labour income, and sales taxes. Additionally, direct support targeted at critical sectors like green technologies and R&D could replace opaque corporate tax incentives, ensuring funds reach intended sectors and promoting innovation and growth. This approach would support the EU’s economic and environmental goals, while fostering a much more appealing investment climate (Section 5).

EU Digital and Technology Policy to Support Technology Adoption and Diffusion

To navigate the digital economy, the EU must balance regulatory policies to foster innovation and growth, recognising digital policy as a key horizontal strategy essential for cross-sector advancement. Critical changes include reconsidering overly stringent data protection standards, promoting an innovation adoption-centric Digital Single Market, and actively engaging in global digital integration, especially with the US, to enhance competitiveness. Achieving a unified digital market requires broad policies to reduce cross-border barriers and regulatory costs.

Ensuring the free flow of data globally will remain vital for supporting innovation and technology diffusion. Well-drafted, evidence-based regulations are needed to protect consumer and human rights without stifling innovation. Encouraging advanced cloud computing and AI integration, including public services, would drive technological progress and foster a competitive, future-oriented European economy (Section 6).

Political Ambitions

Implementing these reforms will demand significant political will, which may differ across the EU27. Coalitions of willing governments could initiate the process, showcasing the benefits and encouraging other Member States to follow. This phased approach would enable pioneering countries to lead by example, fostering broader acceptance and eventual adoption of the necessary reforms throughout the EU. Additionally, Member States could act independently on taxation, social insurance, and digital policies to achieve better economic governance and systemically enhance the competitiveness of their domestic economies.

1. Introduction

The European Union, once acclaimed for its principles of market economy, competition, and trade openness, faces significant challenges that threaten its foundational ideals and future economic vitality. Despite the core values enshrined in its legal framework, the EU’s regulatory landscape has evolved in ways that increasingly reduces the competitiveness of EU-based companies and its attractiveness as a predictable investment destination.

Under the political leadership of Ursula von der Leyen, who took office as President of the European Commission in 2019, there has been a marked shift towards interventionist industrial, trade, and technology policies. This shift, exemplified by initiatives aimed at increasing the “EU’s strategic autonomy” in the world, has introduced several complex and cumbersome regulations that often impede economic freedom and counteracts European industries international competitiveness.[1]

Key economic and technological innovation indicators suggest that the EU is progressively falling behind when compared to major jurisdictions across the globe.[2] In our extensive research and analysis concerning the EU Single Market and trade policy, we have provided numerous recommendations aimed at enhancing the EU’s long-term international competitiveness.[3]

In this paper, we concentrate on three central horizontal policies that urgently require reforms: EU competition policy, tax policies, and digital policies. We caution against political complacency, emphasising the necessity to make Europe significantly more attractive for private-sector investments which heavily rely on accommodating economic, trade, and technology policies, with benefits extending to large as well as smaller and growing enterprises. We consider these three policies as extremely important. Other policies to consider are capital market conditions and energy policies, which, however, fall outside the scope of this paper.

Targeting these major horizontal policies, our analysis is guided by the following questions:

- Is EU competition policy suitable for an era where innovation and productivity, driven by large enterprises, are paramount, or does it penalise its most productive, innovation-oriented and competitive industries?

- Can the EU afford to maintain complex and extremely cumbersome and costly business tax laws that not only fail to ensure fair taxation but also discourage investment by innovative and productive technology companies?

- How can the EU streamline digital and technology policies to enhance its appeal as a destination for technology-fuelled companies aiming to compete on a global scale?

While considerable political effort is often directed towards harmonising sector-specific policies, legal fragmentation remains a pervasive issue in horizontal policies affecting businesses across all sectors and technologies. Indeed, excessive regulation not only complicates business operations, but also builds barriers to commerce, hindering innovation and deterring investment. However, the imperative for regulatory reform extends beyond simply reducing regulatory red tape. It also encompasses the critical task of addressing policy fragmentation across the 27 EU Member States. In our recommendations, we underscore the urgency of reform and urge policymakers to act swiftly to harmonise horizontal policies to enhance Europe’s competitiveness on the global stage.

The remainder of this paper is organised into several sections that delve deeper into specific regulatory areas: Section 2 discusses the state of investment and implications for the EU’s future competitiveness. Section 3 provides an overview of determinants of a jurisdiction’s investment attractiveness and discusses of the deterrent effect of regulation on investment decisions. Sections 4, 5, and 6 are devoted to three key policy areas, where we see need for reform: EU competition policy, taxation policies, and digital policies respectively. Section 7 concludes.

[1] See, e.g. ECIPE and Kearney (2022). Measuring the Impacts of the European Union’s Approach to Open Strategic Autonomy. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Strategic-Autonomy-Impacts.pdf. ECIPE (2022). The EU Digital Markets Act: Assessing the Quality of Regulation. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/the-eu-digital-markets-act/. Bruegel (2024). A dataset on EU legislation for the digital world. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/dataset-eu-legislation-digital-world.

[2] See, e.g., McKinsey (2024). Accelerating Europe: Competitiveness for a new era. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/accelerating-europe-competitiveness-for-a-new-era#. IMF (2024). Europe: Turning the Recovery into Enduring Growth. Available at https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2024/05/14/sp051424-alfred-kammer-at-the-ecb-house-of-the-euro-brussels. McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness: Addressing its technology gap. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap.

[3] See, e.g. ECIPE (2024). Reinventing Europe’s Single Market: A Way Forward to Align Ideals and Action. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/reinventing-europes-single-market-align-ideals-and-action/. ECIPE (2023). What is Wrong with Europe’s Shattered Single Market? Lessons from Policy Fragmentation and Misdirected Approaches to EU Competition Policy. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ECI_23_OccasionalPaper_02-2023_LY04.pdf. ECIPE (2022). The Impacts of EU Strategy Autonomy Policies – A Primer for Member States. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ECI_22_PolicyBrief_AutPol_09_2022_LY02.pdf. ECIPE (2024). ICT Beyond Borders: The Integral Role of US Tech in Europe’s Digital Economy. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/the-role-of-us-tech-in-europes-digital-economy/. Also see ECIPE (2024). Openness as Strength: The Win-Win in EU-US Digital Services Trade. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_05-2024_LY03.pdf.

2. The State of Investment and Implications for the EU’s Future Competitiveness

In an increasingly interconnected and innovation-driven global economy, commercial investments in business operations (e.g., infrastructure and staff) and research and development (R&D) serve as the cornerstone for sustaining and enhancing future competitiveness. As industries evolve and technological advancements reshape global markets, the ability of firms to innovate becomes paramount for maintaining relevance and seizing new opportunities. Continuous investments not only foster product and process innovation but also cultivate a culture of adaptability and resilience, crucial qualities in navigating changing market environments. However, recent analyses indicate a substantial disparity between the US and the EU in terms of commercial and technological R&D investments.[1]

While especially large US corporations demonstrate a proactive approach towards innovation, with firms consistently allocating significant resources to R&D activities, the EU businesses lag substantially behind. The relative attractiveness of the US in commercial R&D and capital investments becomes even more striking when considering the relative size of population and labour force between the two jurisdictions. As of 2023, the EU has a population of approximately 447 million and a labour force of about 220 million, compared to around 333 million people and a labour force of about 170 million in the US. Despite the EU’s larger population and labour force, American firms consistently outstrip their European counterparts in R&D spending, highlighting a pronounced “systemic” advantage in corporate innovation and capital investment.[2]

2.1. Technology-intensive Investments: Benchmarking the EU against the US

Recent data reveals that the cumulative R&D spending in the US in 2022 amounted to EUR 527 billion, significantly outpacing the EU’s total of EUR 219 billion. For instance, the US corporations invested EUR 178 billion in Software & Computer Services and EUR 122 billion in Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology, compared to the EU’s EUR 14 billion and EUR 37 billion, respectively.

Furthermore, the cumulative capital expenditure (Capex) spending also highlights this disparity. In 2022, the US’s total Capex spending was EUR 381 billion, compared to the EU’s EUR 313 billion. These figures underscore a pronounced advantage for American firms in innovation investment, which is crucial for fostering long-term economic growth and competitiveness. This pronounced dichotomy underscores a pressing necessity for European policymakers and corporate stakeholders to pro-actively redress the prevailing asymmetry by devising and implementing strategies aimed at increasing R&D investments to ensure sustained competitiveness within the regional economic landscape (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1: Cumulative R&D spending by sector in EU and US in 2022, in EUR billion Source: EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard 2023 (World 2,500)

Source: EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard 2023 (World 2,500)

Table 2: Cumulative Capex spending by sector in EU and US in 2022, in EUR billion Source: EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard 2023 (World 2,500)

Source: EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard 2023 (World 2,500)

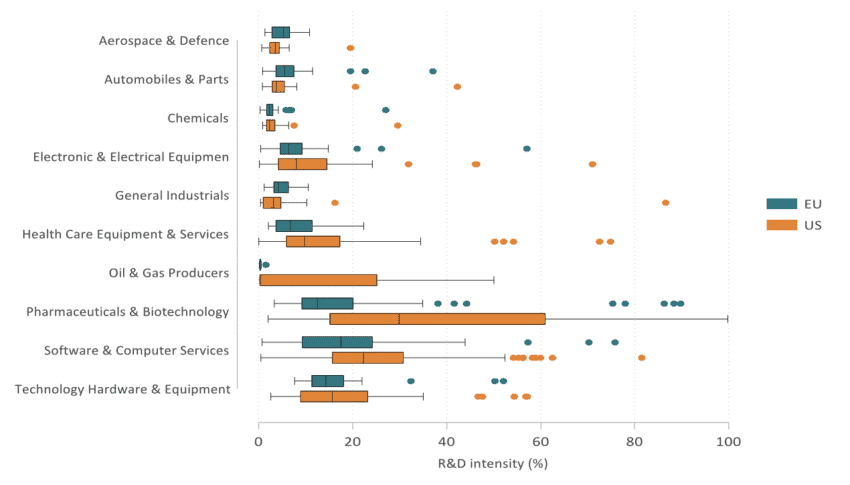

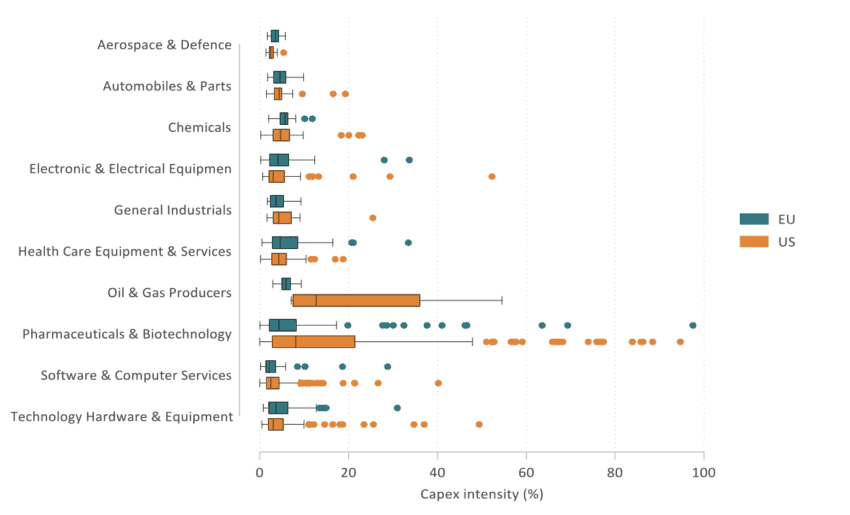

We also examine the metrics of Capital and R&D intensity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2), seeking insights into the investment performance of firms in both jurisdictions.[3] R&D intensity, a measure encompassing R&D and Capex spending relative to revenues, serves as a crucial indicator of the extent to which companies allocate resources towards innovation. This metric unveils the intricate interplay between risk-taking and innovation, as future-oriented companies typically channel earnings and external funds into research endeavours, anticipating solid returns in the future.[4]

The numbers also reveal a distinct disparity between the US and the EU regarding R&D intensity across various sectors. Specifically, sectors such as pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, software, ICT hardware, and healthcare exhibit markedly higher levels of R&D intensity in the US compared to their European counterparts. This discrepancy underscores a greater propensity among US firms to allocate a larger share of their revenues towards research and development activities. Consequently, sectoral averages for R&D intensity tend to be significantly higher in the US than in the EU. Similar patterns are found for capital intensity.

Figure 1: R&D intensity among ten most innovative sectors in EU and US (5-year average, 2018-2022) Source: authors’ calculations based on the EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard 2023 (World 2500). Note: For clarity reasons, the X-axis is capped at 100 percent, due to the presence of outliers. Less than 25 percent of the firms in the dataset have been omitted.

Source: authors’ calculations based on the EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard 2023 (World 2500). Note: For clarity reasons, the X-axis is capped at 100 percent, due to the presence of outliers. Less than 25 percent of the firms in the dataset have been omitted.

Figure 2: Capex intensity among ten most innovative sectors in EU and the US (5-year average, 2018-2022) Source: authors’ calculations based on the EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard (World 2500). Note: For clarity reasons, the X-axis is capped at 100 percent, due to the presence of outliers. Less than 5 percent of the firms in the dataset are omitted.

Source: authors’ calculations based on the EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard (World 2500). Note: For clarity reasons, the X-axis is capped at 100 percent, due to the presence of outliers. Less than 5 percent of the firms in the dataset are omitted.

2.2. The EU’s Attractiveness to Foreign Investors

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is crucial for a jurisdiction’s long-term competitiveness, positively impacting productivity growth by introducing new technologies, expertise, and capital, fostering a skilled workforce, and increasing competition.

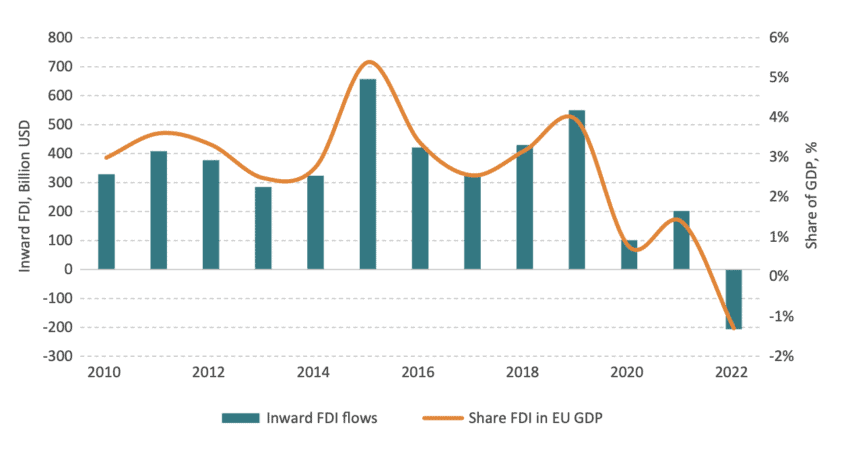

Data on EU inward FDI from 2010 to 2022 reveals significant fluctuations, with notable spikes in 2015 and 2019, reaching USD 658 billion and USD 550 billion, respectively. However, recent years have shown a dramatic decline, with FDI dropping to USD 101 billion in 2020 (largely a reflection of the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic) and EUR 203 billion in 2021, representing only 1 percent of GDP each year. Moreover, 2022 saw a net disinvestment of EUR 206 billion, equating to approx. 1 percent of GDP. This downward trend suggests increasing investment uncertainties, regulatory challenges, and, overall, a reduced attractiveness of the EU as an investment destination (see Figure 3).

Globally, FDI totalled USD 1.3 trillion in 2022, which was 34 percent above 2020 levels, reflecting a robust post-COVID recovery. However, there was a year-on-year decrease of 14.3 percent compared to 2021. The EU27 significantly contributed to this global decline. Despite the overall decline in FDI inflows, the cumulated number of foreign transactions into the EU27 displayed an increasing trend between 2015 and 2022, with an average yearly number of 2,200 foreign acquisitions and 3,200 greenfield investments.[5] However, the second half of 2022 saw a significant fall in deal-making due to economic slowdowns and rising financing costs driven by higher interest rates implemented by central banks to control inflation. Inflationary pressures, worsened by Russia’s war against Ukraine and the resulting impact on energy and commodity prices, along with widespread supply chain disruptions, led investors to adopt a more prudent approach, waiting for more favourable conditions. These factors collectively contributed to the weakening confidence in the EU as an investment destination.[6]

Figure 3: Inward FDI flows, absolute terms and share in % of GDP Source: OECD and Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: OECD and Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

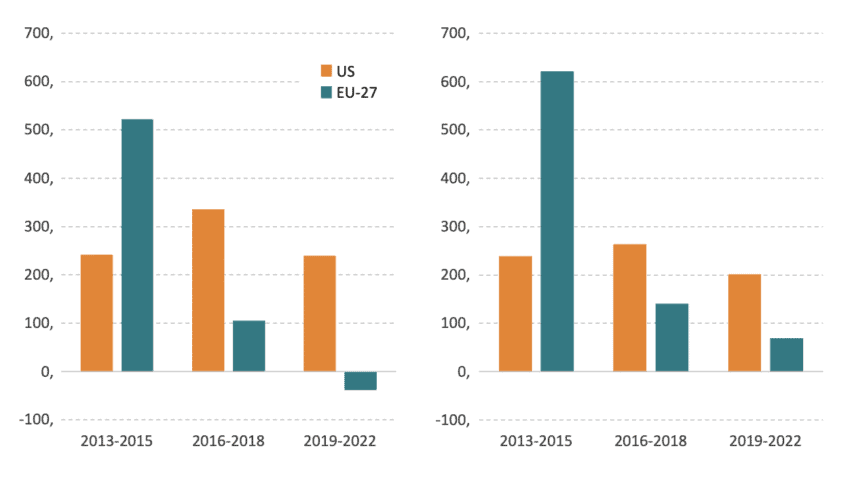

Recent FDI data also reveals a stark contrast in investment flows between the EU and the US from 2013 to 2022 (see Figure 4). The EU experienced a dramatic decline in both inward and outward investments, with inward investments dropping from EUR 621 billion to EUR 69 billion, and outward investments plummeting from EUR 522 billion to a net disinvestment of some EUR 38 billion. In contrast, the US maintained relatively stable investment patterns, with inward investments peaking at EUR 264 billion and only slightly decreasing to EUR 202 billion, while outward investments peaked at EUR 336 billion and later settled at EUR 240 billion. This significant disparity also underscores potential economic or policy challenges within the EU, highlighting the need for a reconsideration of broader economic policies to enhance its investment attractiveness and the international competitiveness of EU-based corporations.

Figure 4: Inward and outward (right) FDI flows, three-year averages, in billion euros Source: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat.

While the EU aims to create a unified market, its regulatory complexity and legal fragmentation increase legal uncertainty, affecting investment decisions. Despite the EU’s political ambitions to create a unified market, regulatory complexity and legal fragmentation often deter investments. Regulatory complexity, bureaucratic obstacles, and varying national policies impede investment and economic growth within the EU. Regulatory uncertainty introduces risks regarding the potential revenue from projects, which decreases their feasibility and thus dampens investment, private sector engagement, and innovation.

In contrast, emerging economies are becoming increasingly attractive to investors as they enhance their economic and technological capabilities and improve the quality of their institutions. These countries are implementing reforms to streamline business operations, reduce regulatory burdens, and foster a more conducive environment for investment, thus drawing attention away from the EU.

Generally, legally fragmented markets reduce the incentives for producers to invest by shrinking the potential size of the market, making substantial investments in research and development or new production facilities increasingly uncertain and risky [7] Based on feedback from corporations, several major business associations (EuroCommerce, Business Europe, ERT, DIGITALEUROPE, and Eurochambres) have voiced concerns about the European economy’s downturn and the EU’s failure to effectively deepen the Single Market over the last decade. They point out that the Single Market no longer functions as a true free trade area due to inconsistent implementation of EU laws across member states and obscured enforcement mechanisms against national regulations that lead to market fragmentation. This situation hinders companies’ expansion and innovation capabilities, particularly affecting SMEs struggling with high compliance costs.[8]

A recent survey-based study by the European Investment Bank demonstrates the economic significance of uncertainty for investment decisions. European firms perceiving uncertainty as a major impediment are more likely to reduce investment and less likely to increase investment, with negative impacts on employment (growth).[9] Even though the measure of uncertainty goes beyond regulatory complexity and uncertainty about regulatory changes in the EU, the study findings indicate that prolonged uncertainty can have large very negative economic consequences.

2.3. EU Regulations Undermining Public R&D Incentives

Despite substantial government support for R&D through tax incentives and direct funding, the EU continues to lag behind, raising concerns about the effectiveness of these incentives and suggesting that they may constitute a waste of taxpayers’ money.

Between 2006 and 2019, government support for business R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP increased in 19 EU countries and the US. This support is provided through two main channels: direct funding and tax incentives. The EU allocates a greater proportion of this support through tax incentives (EUR 13 billion) compared to direct funding (EUR 10 billion), while the US maintains a more balanced approach, with 52 percent of support coming from direct funding and the rest from tax incentives (see Figure 5). This indicates that both regions recognise the importance of R&D for economic growth, though they differ in their methods of support.

Figure 5: Direct government funding and government tax support for business R&D, 2019 and 2006 (percentage of GDP) Source: OECD.

Source: OECD.

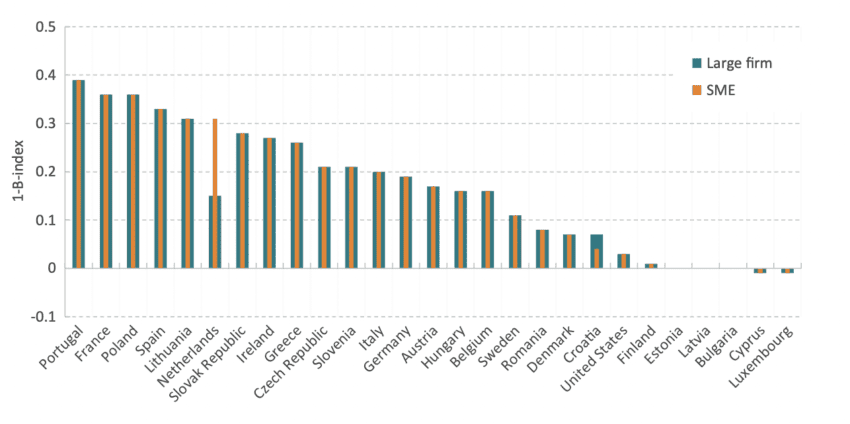

In 2022, the implied tax subsidy rate for R&D expenditure, measured by the B-Index, reveals the extent of preferential tax treatment for R&D investments (see Figure 6). A higher implied subsidy rate means more generous tax provisions, reducing the cost of R&D for businesses. For example, an implied subsidy rate of 0.1 indicates a 10 percent reduction in R&D investment costs due to tax incentives. These rates highlight how tax policies can significantly lower the financial barriers for businesses investing in R&D, promoting innovation and enhancing global competitiveness. Despite the higher implied tax subsidy rates for R&D expenditure in many EU Member States, including large countries such as France and Spain (with rates between 0.3 and 0.4), the US continues to see significantly more investment in R&D, even with a much lower rate of 0.1. This paradox highlights the limitations of relying solely on tax incentives to stimulate R&D investment.

Figure 6: Implied tax subsidy rates on R&D expenditure in 2022 (1- B-Index, for profitable firms) Source: OECD.

Source: OECD.

The pronounced advantage of US-based firms in both R&D and capital expenditure underscores the urgent need for European policymakers to re-evaluate accompanying policy strategies. The EU’s recent decline in FDI and the lower R&D intensity across key sectors highlights systemic issues that current policies have failed to address. Rather than continuing with ineffective R&D incentives that do not translate into competitive investment levels, the EU should focus on creating a more conducive environment for innovation and investment through streamlined regulations, harmonised tax codes, and enhanced digital policies. Only by addressing these fundamental challenges can the EU hope to close the gap with the US and ensure long-term economic dynamism and international competitiveness.

[1] ECIPE (2024) ICT Beyond Borders: The Integral Role of US Tech in Europe’s Digital Economy. Available at: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_06-2024_LY03.pdf

[2] World Bank data.

[3] Comparing the economic performance of the EU to the US provides a valuable means of evaluating the EU’s economic development and competitiveness. Both regions share market economy principles and have a deep-rooted transatlantic relationship. By benchmarking against the US, policymakers can identify areas of strength and weakness within the EU’s economy, helping to inform decisions aimed at improving competitiveness, attracting investment, and fostering economic growth and structural economic change.

[4] Our analysis encountered a notable challenge stemming from outliers, exemplified by companies such as Arena Pharmaceuticals, whose R&D intensity figures exhibit extreme values. These outliers, with their exceptionally high R&D intensity readings, significantly skew sector averages, rendering them unreliable as indicators of overall sectoral performance. To address this issue, we opted for a more nuanced approach, focusing on the distribution of R&D intensity across sectors. By employing visualisation techniques such as box plots, we were able to present a more accurate representation of sectoral performance, excluding outliers and thus providing a clearer understanding of prevailing investment trends.

[5] Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council : Third annual report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union. (2023) COM(2023) 590 final. Available at : https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14427-2023-INIT/en/pdf

[6] ibid

[7] See, e.g., European Investment Bank (2024). Investment barriers in the European Union 2023 – A report by the European Investment Bank Group. Available at https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/20230330_investment_barriers_in_the_eu_2023_en.pdf.

[8] See, e.g., EuroCommerce (2022). Fresh political engagement required to renew economic integration in the Single Market. For an overview of major barriers to the free movement of goods, services, capital and people in the Single Market, see ERT (2024). ERT Single Market Stories. Available at https://ert.eu/single-market/stories/; ERT (2024). Single Market Obstacles – Technical Study. Available at https://ert.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ERT-Single-Market-Obstacles_Technical-Study_WEB.pdf.

[9] European Investment Bank (2024). The effect of uncertainty on investment. Evidence from EU survey data April 2024. Available at https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/20240131_economics_working_paper_2024_02_en.pdf.

3. Regulation and the Deterrent Effect on Investments

Under the von der Leyen Commission, the EU has emphasised strategic autonomy and industrial policy initiatives, shifting focus away from legal harmonisation and structural reforms to improve the international competitiveness of Member State economies.[1] This shift towards increasing legal intervention reduces the EU’s long-term investment attractiveness, especially as global economic, trade, and technological capabilities rapidly advance, increasing economic gravity for global investment flows. Over the past decade, emerging market economies have significantly improved their technological and economic capabilities. Key factors driving this growth include substantial investments in technology, enhanced economic policies, and the increasing global competitiveness of large companies within these markets.[2]

The EU’s comprehensive regulatory framework and ambition to influence global trade and technology standards often result in legal uncertainty for businesses, impacting capital risk in several ways:

- Ambiguous or frequently changing regulations in the EU increase compliance costs and diminish profitability, as businesses must allocate significant resources to navigate complex and varying rules across Member States, which is especially burdensome for companies operating in multiple countries. The ERT survey, titled “ERT Single Market Stories,” offers numerous clear examples, ranging from plastic production and standards for new medicines to regulations for elevators.[3]

- Regulations also cause operational delays by creating bureaucratic obstacles and necessitating legal clarifications, adversely affecting time-sensitive business opportunities and reducing competitiveness. For example, biopharmaceutical manufacturers introducing the same new medicine in different EU countries face time and financial losses due to inconsistent evidence requests, leading to higher costs. Ultimately, this undermines the EU’s competitiveness and attractiveness for pharmaceutical innovation.[4]

- An unpredictable regulatory environment makes investors cautious, leading to reduced investment inflows as businesses and investors prefer more stable and predictable settings.[5]

Overall, the EU faces substantial challenges with complex, often vague regulations and legal fragmentation across Member States, amplified by linguistic diversity. This necessitates additional resources for legal counsel, translation, and compliance management, further increasing operational costs. Meanwhile, companies in the US benefit from clearer regulations, which, despite some state-level differences, are easier to navigate due to the common language. The EU, with its 27 countries and 24 official languages, faces significant trade and business challenges due to its linguistic diversity.[6] Unlike the US, where English potentially mitigates the negative impacts of internal regulatory barriers, the EU’s linguistic diversity and legal fragmentation require additional resources for translation, legal counsel, and compliance management. This results in higher operational costs and complexities, impacting business efficiency and trust in the Single Market.[7]

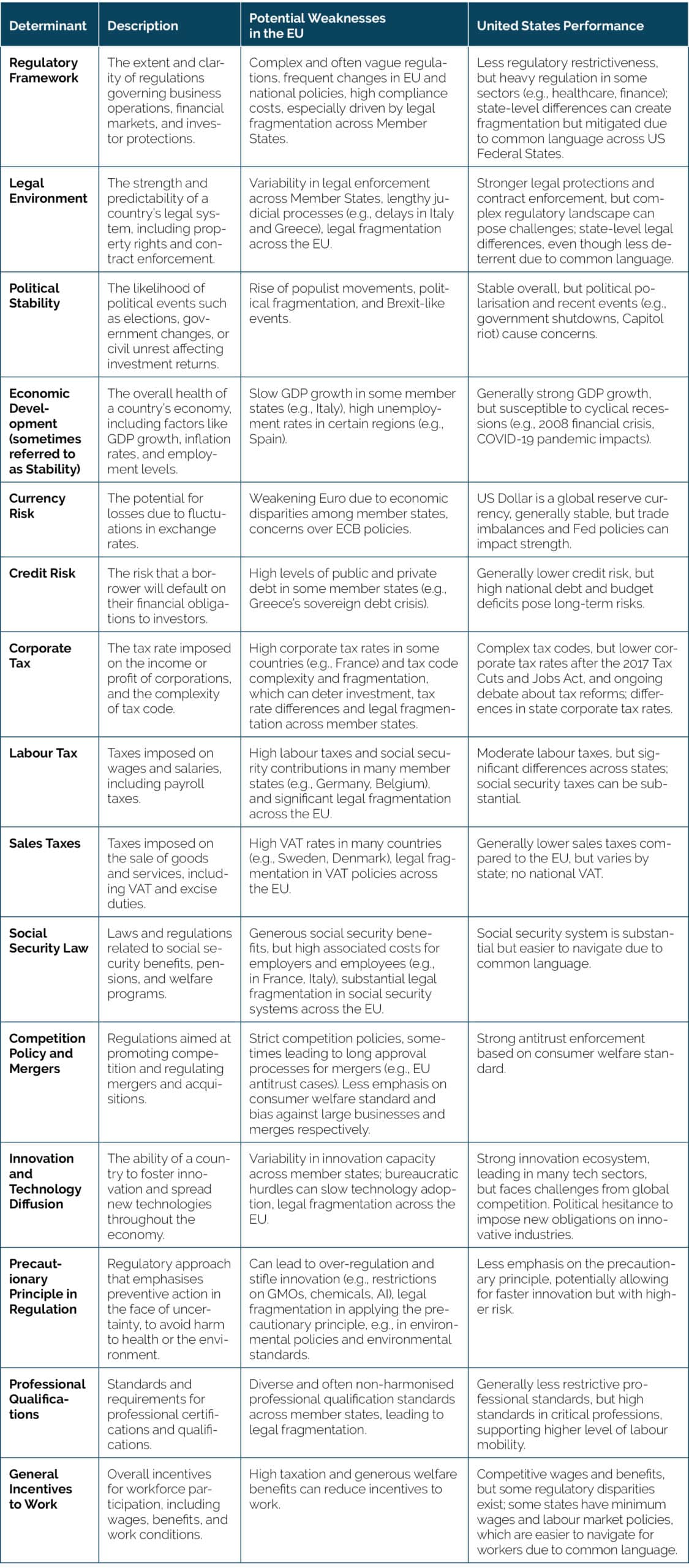

Moreover, the EU’s regulatory approach, emphasising preventive action to avoid harm – embodied in the precautionary principle – can result in over-regulation and stifle innovation, particularly in areas like GMOs, chemicals, and AI. By contrast, US policymakers have historically placed less emphasis on the precautionary principle, allowing for faster innovation and business churn.[8] A general overview of determinants of investment risks for globalised businesses and differences between the EU and the US is provided in Table 3.

Table 3: Overview of determinants of major investment risks for globalised businesses Source: compilation by ECIPE.

Source: compilation by ECIPE.

Considering the above, much needs to be done policy-wise in the EU to enhance Member States’ investment attractiveness and foster economic growth. Below, we focus on areas where meaningful changes in EU and Member State legislation could benefit industries across all Member States and all sizes of corporations.

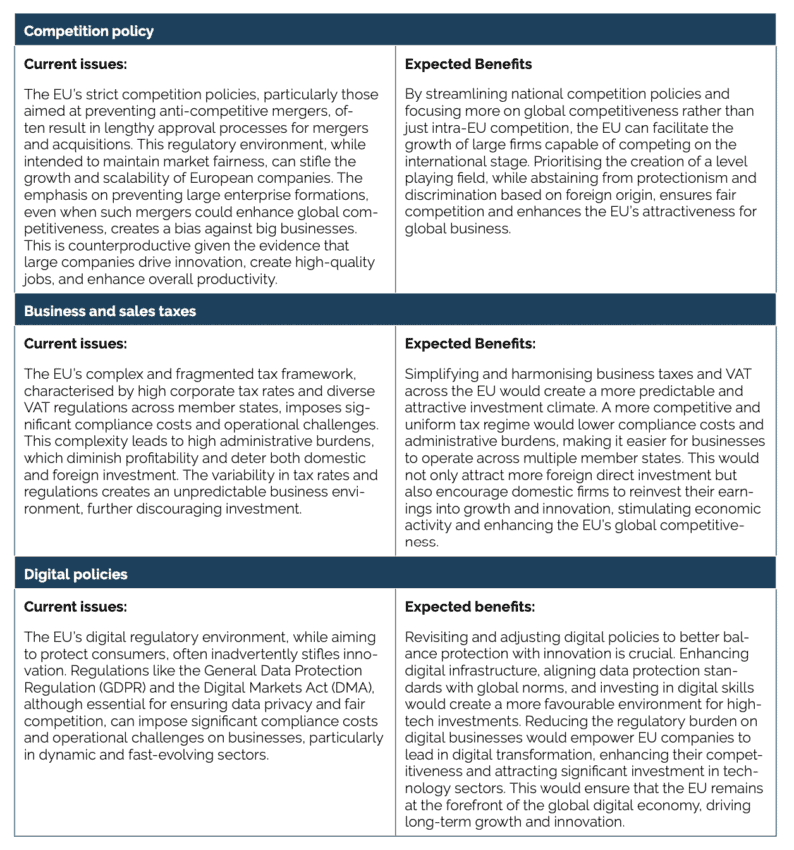

Reducing the deterrent effect from EU and Member State laws in three key horizontal (cross-sector) EU policy areas – competition policy, business taxes and VAT, and digital policies – could significantly enhance the business environment within the Single Market and increase the EU’s attractiveness to both domestic and foreign investors.

Streamlining competition policies would support the growth of large, competitive firms, and their ability to innovate and compete on global markets. Simplifying and harmonising the tax framework would create a more predictable investment climate. Revisiting digital policies to balance protection with innovation would foster a favourable environment for high-tech investments. Overall, material changes to existing legal regimes in these areas would drive economic growth and innovation, and thereby increase the economic competitiveness of EU Member States.

Table 4 provides a summary of key issues and the expected benefits of reducing regulatory deterrents in major EU horizontal policy areas. A more detailed discussion is provided in the following sections.

Table 4: Key issues and expected benefits of reducing regulatory deterrents in major EU horizontal policy areas Source: compilation by ECIPE.

Source: compilation by ECIPE.

[1] See, e.g. ECIPE (2024). Reinventing Europe’s Single Market: A Way Forward to Align Ideals and Action. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/reinventing-europes-single-market-align-ideals-and-action/. ECIPE (2023). What is Wrong with Europe’s Shattered Single Market? Lessons from Policy Fragmentation and Misdirected Approaches to EU Competition Policy. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ECI_23_OccasionalPaper_02-2023_LY04.pdf.

[2] See, e.g., McKinsey (2018). Outperformers: High-growth emerging economies and the companies that propel them. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/Outperformers-high-growth-emerging-economies-and-the-companies-that-propel-them.

[3] ERT (2024). ERT Single Market Stories. Available at https://ert.eu/single-market/stories/; ERT (2024). Single Market Obstacles – Technical Study. Available at https://ert.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ERT-Single-Market-Obstacles_Technical-Study_WEB.pdf.

[4] See, e.g., ERT (2024). What’s in a pill? Why the EU needs a single approach to assessing innovative medicines.. Available at https://ert.eu/single-market/stories/whats-in-a-pill/.

[5] See, e.g., European Investment Bank (2024). The effect of uncertainty on investment. Evidence from EU survey data April 2024. Available at https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/20240131_economics_working_paper_2024_02_en.pdf.

[6] See, e.g. EPRS (2018). Languages and the Digital Single Market. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/625197/EPRS_BRI(2018)625197_EN.pdf.

[7] ERT (2021) Renewing the dynamic of European integration: Single Market Stories by Business Leaders. Available at: https://ert.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/ERT-Single-Market-Stories_WEB-low-res.pdf

[8] In the US, bipartisan hesitance to regulate has often been a notable feature of the policy landscape. While the US approach to regulation has fostered a robust innovation ecosystem, it has also highlighted the need for a balanced regulatory framework that can mitigate the risks associated with rapid technological and market changes.

4. EU Competition Policy

The traditional approach of the EU to competition policy has addressed anti-competitive behaviour through case-by-case investigations, merger reviews, and legal proceedings, ensuring targeted enforcement. This approach allowed for tailored responses to specific market conditions and behaviours, maintaining competitive markets effectively without over-regulation.

At the same time, the EU’s stringent merger policies have been criticised for being too restrictive, potentially hindering the competitiveness and innovation of European firms compared to their global counterparts. Overly stringent merger policies can also deter investors from supporting small tech companies due to the perceived risks and limitations associated with potential mergers and acquisitions. Investors may be reluctant to provide funding to start-ups and smaller firms if they believe that future growth opportunities through mergers or acquisitions will be stifled by regulatory hurdles. This is important as investments and acquisitions by large technology companies have a positive impact on initial seed funding and, generally, venture capital investments (worldwide).[1] A lack of investment support can hinder the development and scaling of innovative tech companies, ultimately preventing the emergence of a dynamic and thriving tech ecosystem akin to “Silicon Valley in Europe”. Without the ability to grow and consolidate, small tech firms may struggle to compete on a global scale, hindering the overall advancement and competitiveness of the European tech sector.

With the introduction of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) in 2022, the EU imposed broad though untested ex-ante regulations on large technology companies. While the DMA formally aims to enhance competition, its broad and prescriptive approach has been criticised for stifling innovation and imposing disproportionate burdens on designated “gatekeepers” and less choice for European users of digital services.

Rapidly evolving global markets and technological advancements necessitate a reassessment and enhancement of EU merger policies and the DMA to ensure that access to new technologies remains conducive to economic growth. With respect to mergers and acquisitions, Enrico Letta and Mario Draghi have recently called for a re-thinking on the EU competition enforcement which should allow for market consolidation and creation of European Champions. Previously, in a joint paper, the governments of Germany and France had proposed new objectives to enhance EU’s competitiveness. The underlying ambitions include making Europe an industrial and technological powerhouse by removing unjustified barriers, promoting industrialisation, and increasing investments.[2] [3] However, the EU and Member State authorities should avoid redesigning merger policies solely to benefit EU-headquartered companies. Instead, competition policies should be crafted to allow for mergers and acquisitions involving EU companies and those based in non-EU market economies, ensuring a level playing field. Asymmetric regulations that privilege companies with an EU passport could lead to protectionism, limiting the potential for beneficial international collaborations and innovation.

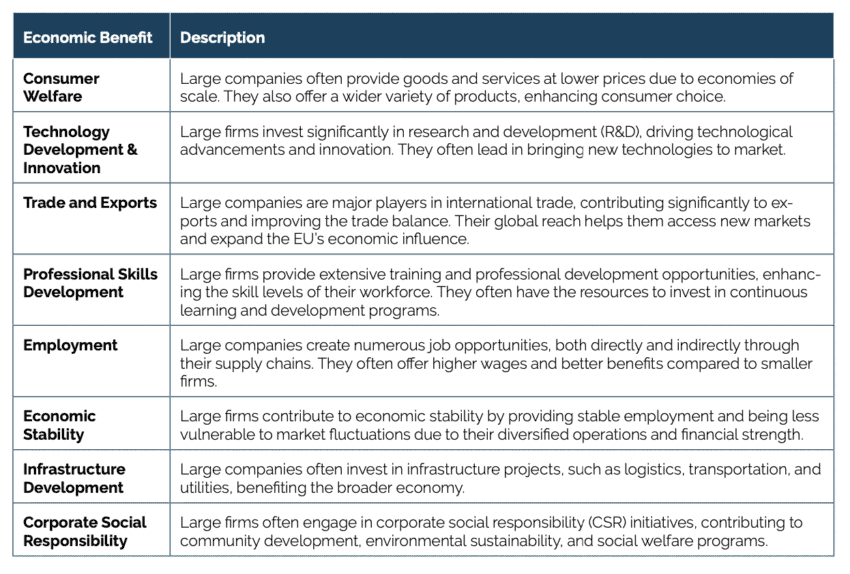

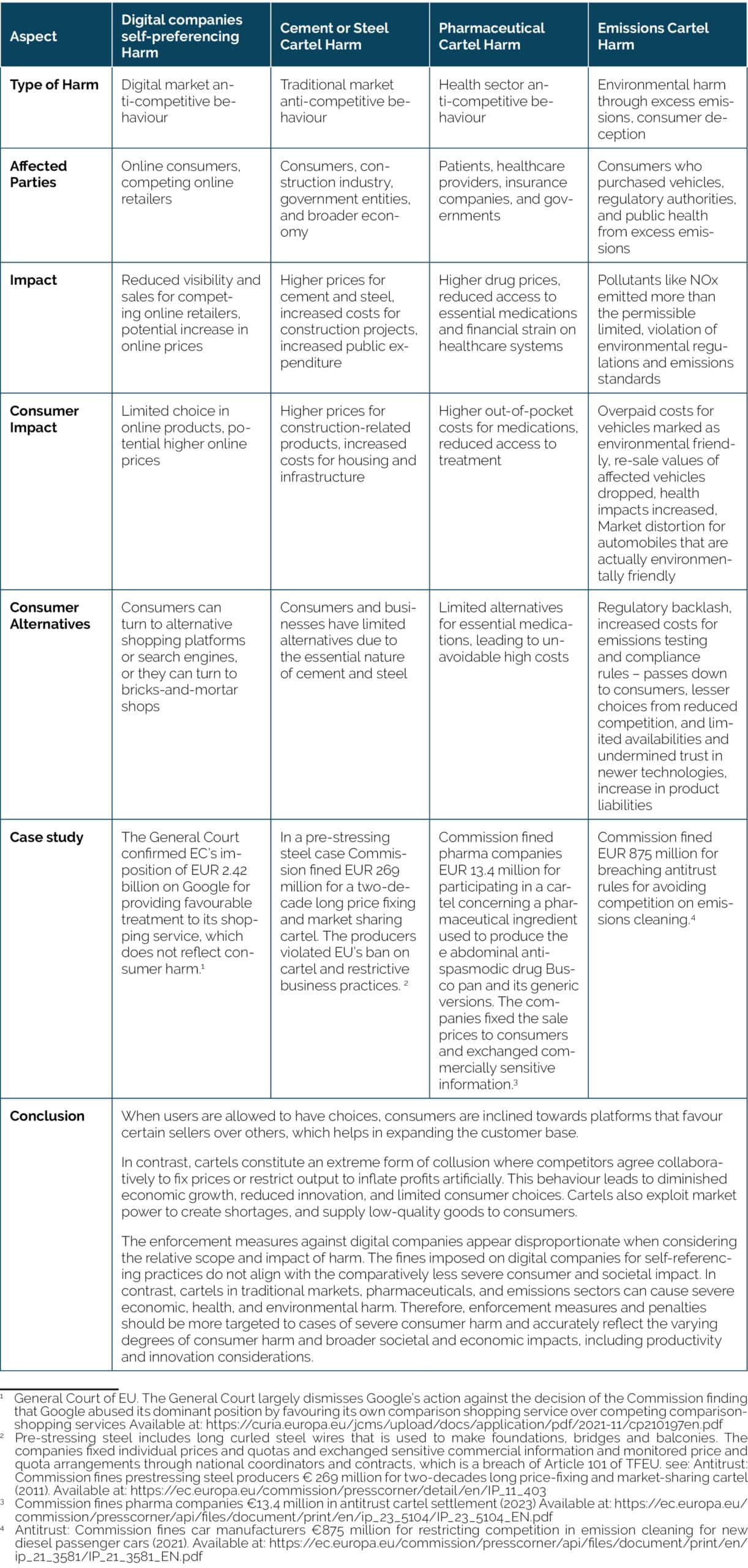

4.1. How Large Firms Drive Innovation and Productivity in the EU

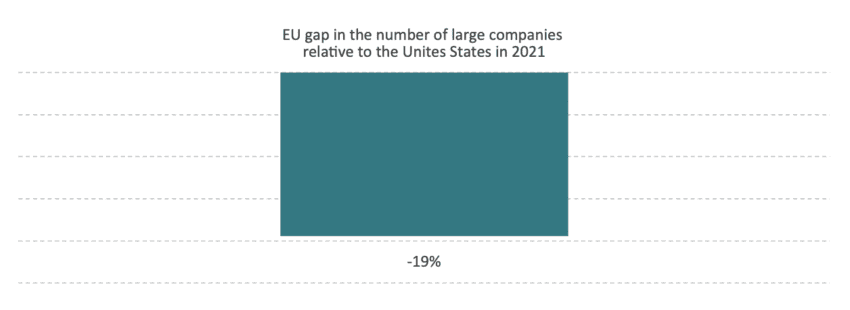

The EU’s competition policy must acknowledge the significant role that large companies play in driving economic growth and delivering societal benefits (see Table 5). An excessively stringent antitrust approach can inadvertently stifle the economic and technological advantages these firms provide.[4] One major benefit is the positive productivity spillovers that large firms confer on smaller enterprises.[5] For instance, a recent study indicates that when a supplier engages with a larger firm, its Total Factor Productivity (TFP) increases by 7 to 9 percent, and its sales grow by 25 percent within four years of the partnership.[6] These benefits are unique to relationships with large companies, highlighting their critical role in enhancing economic productivity and fostering growth. Consequently, it is imperative for governments to support large enterprises or minimise barriers to grow organically rather than excessively regulate their business practices. Against this background, it should also be noted that the EU has a gap in the number of large companies relative to the US. In 2021, this gap amounted to 19 percent when adjusted for the size of the US and EU27 populations (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: The EU’s large business gap (2021) Source: Eurostat and BLS for number of enterprises and World Bank population statistics.

Source: Eurostat and BLS for number of enterprises and World Bank population statistics.

Against this background, it is important to consider how “superstar firms” invest and contribute to innovation and productivity growth. The rapid growth of very large global companies, often referred to as “superstar” companies, has fuelled widespread debate about their impact. These companies, which include global banks, manufacturing giants, and fast-growing tech firms, capture a disproportionate share of economic profit. The top 10 percent of these firms account for 80 percent of positive economic profit, with the top 1 percent alone generating 36 percent of this profit. This concentration highlights the significant role these firms play in the global economy.[7] Superstar firms are distinguished by their substantial investment in intangible assets such as R&D, software, data, brands, and supply-chain partnerships. On average, they spend two to three times more on R&D than their peers, accounting for 70 percent of total R&D spending among the largest companies. This investment strategy results in higher productivity and innovation, as evidenced by the market value of their patents.

Importantly, in Europe, the gap in intangible investment between high- and low-growth companies is notably large. European low-growth companies invest only 1.4 percent of revenues in intangibles, below global and North American rates. In contrast, high-growth European companies invest 6.2 percent of revenues in intangibles, which is 4.4 times more. These data suggest that many European low-growth companies would benefit from allocating more revenue to intangible investments.[8]

Additionally, superstar companies utilise their significant capital investments in intangible assets to achieve increasing returns to scale. This results in higher return on invested capital over time, as intangible investments can easily scale and complement other intangible assets. These companies also engage more in mergers and acquisitions, further boosting their growth and market position. However, while superstar firms may have higher markups, these are typically established early in their life cycle and persist due to their superior productivity and innovation capabilities. There is no indication that star firms use market power to reduce output for supernormal returns. Instead, they maximise value by increasing output, investment, and R&D.[9]

Moreover, the R&D activities of large firms have substantial spillover effects, enhancing the innovation capabilities of smaller firms. This interaction is particularly evident in business-to-business (B2B) sectors, where companies closely collaborate within supply chains.[10] In key sectors such as construction, ICT, manufacturing, trade, and transportation, the productivity gap between larger companies and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) is narrower due to these collaborative relationships.[11] Approximately 66 percent of MSMEs and larger companies operate synergistically, particularly in 45 sectors where their close cooperation results in an overall productivity level of USD 163,000 (in purchasing power parity terms). This figure is 1.5 times higher than in domains where only small or only large businesses excel.[12]

Multiple industry cases underscore the political importance of fostering a balanced regulatory environment that supports the growth and innovation potential of both large and small enterprises. The networks and links between MSMEs and large companies tend to benefit the growth and performance of both. Large companies are also dependent on smaller companies for development to supply, production, service delivery, distribution and sales, and there exists an incentive to raise smaller firms’ capabilities (R&D, workforce) and achieve network efficiencies. For example, German wholesalers gain spill over benefits from being part of a larger ecosystem. They operate as legally independent subsidiaries which remain integrated with upstream purchasers or distributors for large manufacturers for the EU.[13] The ability of firms to have a large-scaled operations which has a substantial customer base can also help the suppliers to extend their supply networks and reach scale economies, which has an effect on the overall economy. Large firms also provide significant development of new technologies, contributing to knowledge diffusion and allowing smaller firms to conduct follow-on innovation.[14]

Table 5: Overview of key economic benefits of large companies in various domains Source: compilation by ECIPE.

Source: compilation by ECIPE.

It is crucial to establish an ecosystem that allows the presence of larger firms and smaller firms to exist together (see Table 6). MSMEs grow fast into large companies and can add to the dynamism of the economies they operate in. Therefore, there exists a cyclic process which if allowed, can promote innovation, and competition among companies and can enhance the overall economy wide participation. About 1 in 5 large companies scaled up from being MSMEs since 2000.[15] There are unique factors which contribute to this, but an overall picture suggests that – availability in resources that can allow expansion of growth opportunities, prioritising technological advancement and reliance on profits to fund their growth can allow companies to scale up. The size of smaller companies plays an important role in their productivity which is relative to large companies. The overall productivity gap increases when the ratio of MSME productivity to large company productivity is brought closer to fuller potential. Narrowing the productivity gap is equivalent to 5 to 10 percent of GDP.

Table 6: Overview of key economic benefits derived by smaller firms from large companies Source: compilation by ECIPE.

Source: compilation by ECIPE.

4.2. The Need for Policy Re-Evaluation

EU merger regulation effectively limits the ability of Member States to interfere and gives an exclusive competence to the Commission to intervene and block the ones they think would impede competition in the market, and the test for merger review is based on competition considerations only.[16] While it is generally beneficial to have merger competence at the EU level, ensuring a consistent and fair approach across all EU Member States, the European Commission should broaden its assessment criteria to include global competition, especially imports and investments from non-EU countries, and dynamic competition. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how mergers impact the competitive landscape beyond the EU.

The European Commission’s decision to block the merger between Siemens and Alstom in February 2019, based on the EU Merger Regulation, has sparked significant political controversy. The prohibition, which aimed to prevent a significant impediment to effective competition (SIEC), has been criticised for not sufficiently considering the global competitiveness of European enterprises. Critics argue that this decision hindered the creation of a “European champion” capable of competing with global giants like the state-owned China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC). Despite the political outcry and calls for mechanisms to overturn such decisions, akin to Germany’s “Ministererlaubnis,” the Commission’s role as an enforcer of legislation limits its political discretion in these matters.[17]

Despite the Commission’s detailed appraisal, which included a global market analysis for high-speed trains, the prohibition highlighted a critical need to re-evaluate the EU’s merger assessment criteria, which may not actually require legal revisions. While the SIEC test ensures competition within the EU by considering both foreign and local companies in the market definitions it establishes, it may not always fully capture the broader global context in which companies operate. The European Commission already considers competitive pressures from both EU and non-EU companies in its assessments, aiming to level the playing field for all companies, regardless of origin. However, the European Commission could, as it has in the past, show greater flexibility in its assessment of potential competition by considering longer time frames. Extending this assessment period may not require new legislation but rather an adjustment in the Commission’s approach, thereby better supporting the strategic interests of European firms.[18]

The application of the SIEC test is inherently prone to interpretation and is heavily dependent on assumptions about future market conditions. This subjectivity can lead to differing conclusions on the potential longer-term impacts of mergers.[19] In the context of the railway industry, which operates as a network industry with significant public procurement, the dynamics differ markedly from many other sectors of the economy. Indeed, public procurement plays a crucial role in shaping competition and market structure in the railway sector, adding an additional layer of complexity to merger assessments. However, the EU utilises various tools to address state-supported foreign firms, including Trade Defence Instruments (TDI) to counter unfair trade practices, which can be made more effective with increased transparency and stricter enforcement. Public procurement rules, including the International Procurement Instrument (IPI) and the new the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) aim to prevent such firms from gaining unfair advantages and ensure reciprocity in public procurement access, enhancing the EU’s ability to maintain fair competition in the internal market, e.g., by scrutinising and addressing financial contributions from non-EU countries.

Beyond these issues, in the application of the SIEC test, the European Commission may omit certain factors related to the price sensitivity of buyers, such as the impact on quality/performance and buyer profits. Such omissions, however, can become significant in the context of assessing competitive constraints in industries where business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-government (B2G) transactions are prevalent.[20] This specificity necessitates a nuanced approach that recognises the unique challenges and opportunities within such network industries, ensuring that regulatory decisions foster a competitive yet globally resilient market environment.

More generally, EU competition policy faces significant challenges in balancing the prevention of anti-competitive practices with fostering innovation and growth, particularly regarding large companies and mergers. Influenced by neo-Brandeisian and anti-corporate ideologies, there is a push for stringent antitrust enforcement to dismantle large firms perceived as market-dominating. This approach, evident in recent actions against major tech companies, aims to address the “market power problem” but may overlook the broader economic benefits these firms provide, such as productivity boosts to their suppliers, and innovation and productivity effects, especially for vertical mergers.[21] Generally, research indicates that the increase in market power often correlates with a firm’s productivity rather than purely anti-competitive measures.

At the core of the competitive process is the principle that market actors should be free to make their own economic choices within a framework supervised by public bodies. Antitrust agencies play a crucial role by preventing anti-competitive conduct that harms the development of level playing field, such as cartels or predatory exclusion.[22] A vital aspect of competition is allowing firms with market power to charge prices that reflect their scale of production. This dynamic is essential for promoting innovation and efficiency within the market.

An effective antitrust policy should enable firms to capture the surplus generated by their investments, innovation, and foresight. Policies that prioritise static efficiency at the expense of dynamic efficiency, or those that aim to protect competitors instead of consumers, risk impeding long-term economic growth and welfare. Therefore, it is critical to strike a balance that fosters competitive markets while also recognising the substantial contributions of large firms to the broader economy. As noted, “[a]n essential element of appropriate antitrust policy is to allow a firm to capture as much of the surplus that, by its own investment, innovation, industry, or foresight, the firm has itself brought into existence.”[23] This relaxed approach to competition enforcement in the EU would ensure that antitrust policies support overall economic welfare and sustainable growth.

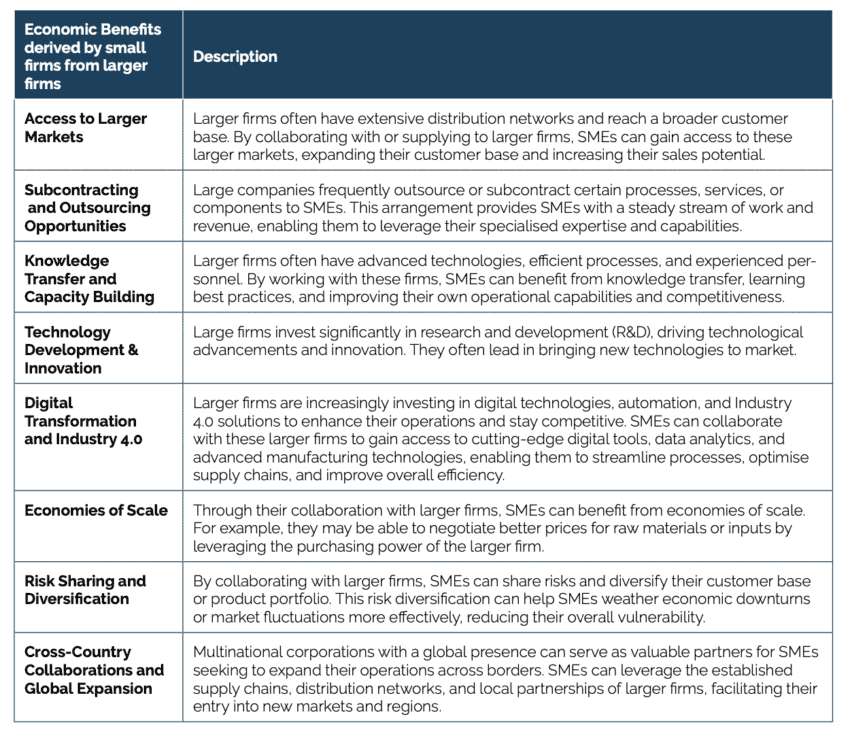

4.3. The Need to Introduce Urgency and Proportionality Checks

The European Commission’s efforts to regulate large tech companies, particularly through the DMA, have raised concerns about potentially stifling innovation and harming consumer benefits. For example, the DMA’s obligations under Articles 5 and 6, which include rules on self-preferencing, data access, and interoperability, aim to prevent anti-competitive practices. However, these rules may often overlook the broader and dynamic benefits that large companies and their online platforms provide, such as enhanced-quality services, innovation, and significant productivity growth. In fact, the EU’s strict regulatory stance, as seen in the DMA’s enforcement against several major tech companies, seeks to address “market power problems” but does not consider and weight all the economic advantages these firms offer.

There is also a need for proportionality in the assessment of mergers, which means evaluating not only the ability and incentives of companies to engage in anti-competitive practices post-merger, such as foreclosure of competitors, but also the actual probability and broader economic impact of mergers. It is thus crucial to consider the broader economic benefits that mergers can bring. Mergers often drive innovation, improve service quality, and enhance productivity growth. Overly stringent regulations would stifle these positive contributions, leading to unintended longer-term consequences for consumers and the economy at large. Therefore, proportional measures should be implemented to ensure that merger enforcement rules are not excessively burdensome and are adaptable to dynamic market developments, ultimately supporting both competition and economic dynamism.

To ensure that EU competition policy effectively balances the need to prevent anti-competitive practices with fostering innovation and growth, the EU should introduce urgency and proportionality checks. These checks would help the Commission target genuinely harmful practices without impeding the positive contributions of large firms. This approach would focus regulatory efforts on clear-cut violations, such as cartels, that have much more obvious negative impacts on consumers, while allowing beneficial business practices to continue (see Table 7 comparing alleged harm of self-preferencing and harm by cartels).

By implementing urgency and proportionality checks, the EU can ensure its competition policy effectively targets abusive practices that harm consumers without stifling the beneficial contributions of large firms. This balanced approach would support innovation, protect consumer welfare, and maintain fair competition across the market.

Table 7: Comparing online platform “self-preferencing” and cartel harm to consumers

Source: compilation by ECIPE.

Source: compilation by ECIPE.

4.4. Proportionality in EU Merger Policy

The EU’s stringent stance on large companies, particularly in the technology sector, undermines the competitive edge of European companies on a global scale. While mergers between companies can significantly increase innovation by boosting R&D productivity and generating spillovers from R&D spending,[28] recent merger cases and the adoption of ex-ante regulations demonstrate the EU’s rigorous approach to preventing the formation of large enterprises, thereby undermining productivity gains and impeding the development of innovative products and services.

For instance, in 2012, the European Commission prohibited a merger between Deutsche Boerse and NYSE Euronext, citing concerns that the merger would result in a quasi-monopoly in exchange-traded European financial derivatives. Deutsche Boerse in its appeal pointed that European Commission’s prohibition of the merger on grounds that merging the parties will constrain innovation competition was incorrect. The company’s claim was dismissed.[29]

The European Commission has continued to pursue investigations into mergers and acquisitions made by American technology companies. In 2020, the Commission opened an investigation against Apple on the grounds whether Apple discriminated its rivals like Spotify on its app store and “how other competitors were treated on its mobile payment service app.”[30] In the Commission report, “[c]ompetition policy for the digital era,” the report pointed that dominant digital firms are likely to have “strong incentives to engage in anti-competitive behaviour” and “require vigorous competition policy enforcement and justify adjustments to the way competition law is applied.”[31] The report also highlights a significant shift in the burden of proof, requiring companies to demonstrate that their actions are not anti-competitive in nature. Specifically in some cases if a company introduces a new product or a service which can potentially restrict competition, it must now prove that the product actually benefits the consumers. [32]

As outlined above, the debate about urgency and proportionality in EU competition policy thus extends to the merger enforcement. An overly restrictive approach to mergers and acquisitions will ultimately hinder European firms from achieving the scale necessary to compete globally, particularly against larger US and Chinese competitors. Restrictive merger regulations can limit the ability of EU companies to expand and integrate across borders, imposing high compliance costs and creating legal uncertainties that discourage investment and innovation.[33] [34]

In 2019, the French and the German governments adopted a manifesto for a European industrial policy fit for 21st century (the Franco-German Manifesto, see Table 8). The manifesto called for a redefined distribution of authority through a centralised decision-making concerning competition policy. It urged the Member States to also adopt a more interventionist approach in shaping their industrial policies.[35] Following the 2019 Commission’s dismissal of the merger of Alstom and Siemens, the governments of France and Germany presented a manifesto with a set of far-reaching proposals designed to reshape EU industrial and competition policy.[36]

The manifesto is a follow up call from 19 EU governments to update EU antitrust rules to facilitate the presence of European industrial firms to compete against China and US.[37] The proposal to veto European Commission decisions on competition policy, is defended by the overall claim that Europe ́s competitiveness in manufacturing is in decline. The manifesto’s goal was increase political and advance an ideological shift in how the European Commission implements competition policy in the future.[38]

Table 8: Re-forming the Competition Policy under industrial pre-text[39] Guided under the pretext of national/economic security, countries within the EU may very likely proceed to form a coalition to advocate for protectionist policies which will undermine competition. For instance, in the “Friends of an Effective Digital Markets Act” coalition, which includes Germany, France, and the Netherlands, the trio introduced a position paper “Strengthening the Digital Markets Act and Its Enforcement” which said that Member States should have the discretion to set and enforce national rules around competition law because the “importance of the digital markets for our economies is too high to rely on one single pillar of enforcement only.” The coalition paper also mentioned that “a larger role should be played by national authorities in supporting the European Commission,[40] an underlying base for targeting the big tech, and non-EU companies.

Guided under the pretext of national/economic security, countries within the EU may very likely proceed to form a coalition to advocate for protectionist policies which will undermine competition. For instance, in the “Friends of an Effective Digital Markets Act” coalition, which includes Germany, France, and the Netherlands, the trio introduced a position paper “Strengthening the Digital Markets Act and Its Enforcement” which said that Member States should have the discretion to set and enforce national rules around competition law because the “importance of the digital markets for our economies is too high to rely on one single pillar of enforcement only.” The coalition paper also mentioned that “a larger role should be played by national authorities in supporting the European Commission,[40] an underlying base for targeting the big tech, and non-EU companies.

4.5. Key Changes to Consider for a Pro-Productivity EU Competition Policy

To address pressing issues in EU competition policy, the European Commission and national governments should more clearly differentiate between firms that gain market power through anti-competitive practices and those that can become market leaders through genuine productivity and innovation. This differentiation is crucial for ensuring that competition policies effectively target and penalise companies engaging in unfair practices, while simultaneously fostering an environment that encourages and rewards innovation and efficiency.

Harmonising the Enforcement of Competition Policies

Harmonising competition and merger enforcement across the EU would create a more predictable business environment, reducing compliance costs and fostering a healthier market for investment and productive economic activity. At the same time, the need to keep competition policy independent from political interference and European industrial policy ambitions and goals need to be prioritised.

To reduce legal uncertainties and support scaling and cross-border investments, the EU must harmonise competition enforcement. Currently, differences in national enforcement creates unnecessary legal uncertainties and compliance burdens for businesses operating across multiple Member States. Harmonising procedural laws and encouraging the establishment of specialised competition courts across Member States can create a more consistent judicial framework. Promoting uniform economic assessments with standardised tools and conducting joint market studies can help align the economic context for enforcement decisions. Continuous monitoring, performance metrics, and regular reporting from National Competent Authorities (NCAs )to the European Commission could ensure ongoing alignment and effectiveness of competition law enforcement across the EU.

A much more unified approach would reduce these burdens, provide a predictable legal environment, and eliminate the uneven playing field that currently exists. This alignment is particularly crucial as the EU faces the rapid growth and importance of the digital economy.

Investigations and Enhanced Institutional Capabilities

A clear prioritisation framework shall be established to identify and allocate resources to cases with the highest potential for consumer harm or market impact. This risk-based approach will ensure that critical cases receive timely attention and resolution. Existing investigative and judicial processes shall be reviewed and optimised to eliminate redundancies, improve coordination between relevant authorities, and expedite decision-making without compromising due process or the quality of assessments.

Improving the capabilities of the European Commission and the courts to enforce competition laws effectively is vital. Well-resourced institutions capable of responding swiftly to market abuses are essential for maintaining market fairness without overly constraining large enterprises. Recent antitrust cases against major tech companies underline the EU’s commitment to competitive markets, but there is a delicate balance to maintain—policies must not stifle the growth and scaling of European tech firms. Moreover, negative merger decisions can have a harmful impact on the startup ecosystem and the investability of Europe, as they may discourage investment in innovative ventures due to perceived regulatory hurdles. When startups and investors perceive the regulatory environment as overly restrictive, it can lead to reduced venture capital inflows and hinder the ability of new businesses to scale effectively (see discussion above). Ensuring that competition policies are balanced and do not disproportionately affect the dynamism and attractiveness of the European tech landscape is crucial for fostering a robust and investable startup ecosystem.

Urgency and Proportionality Checks

In addressing mergers and compliance with ex-ante policies, as in the case of the DMA, competition authorities shall always adopt a balanced and evidence-based approach. Investigations shall be conducted impartially, considering both the potential pro-competitive benefits and anti-competitive risks of such activities. Decisions shall be based on sound economic analysis, transparency and aimed at promoting consumer welfare and market efficiency.

[1] See, e.g., Prado and Bauer (2022). Big Tech platform acquisitions of start-ups and venture capital funding for innovation. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167624522000129. Also see American Bar Association (2023). Merger Enforcement Considerations – Implications for Venture Capital Markets and Innovation. June 2023. Available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/antitrust_law/resources/source/2023-june/ merger-enforcement-considerations/.

[2] A new agenda to boost competitiveness and growth in the European Union. Available: https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/975226/2288870/c080323912f0e4229d1dbb5ae8333879/2024-05-28-deu-fra-papier-eng-data.pdf?download=1

[3] Over the last fifteen years, EU’s portion of global capital markets dropped from 18 percent to 10 percent. Its share of global GDP declined by 27 percent from 2006 to 2022, Breen, C. et al. (2023) EU Capital Markets: A New Call to Action. New Financial. Available at: https://newfinancial.org/wp-content/uploads/2023.09-EU-capital-markets-a-new-call-to-action-New-Financial.pdf; Within the past seven years, the EU’s representation in the market capitalisation of the top 100 global companies decreased from 11 percent to 5 percent, Demarigny, F. (2024, January 11). L’autonomie stratégique passe par l’Union des marchés de capitaux. Le Grand Continent. Available at: https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2024/01/11/lautonomie-strategie-par-lunion-des-marches-de-capitaux/

[4] Long, T. (2024, April 12). Large Firms Generate Positive Productivity and Non-Productivity Spillovers for Their Suppliers. ITIF. Available at: https://itif.org/publications/2024/04/12/large-firms-generate-positive-productivity-non-productivity-spillovers-for-suppliers/

[5] Amiti, M., Duprez, C., Konings, J., & Van Reenen, J. (2023). FDI and superstar spillovers: Evidence from firm-to-firm transactions (No. w31128). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[6] Long, T. (2024, April 12). (see note: 24)

[7] See McKinsey (2019). What every CEO needs to know about ‘superstar’ companies. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/what-every-ceo-needs-to-know-about-superstar-companies.

[8] See, e.g., McKinsey (2022). Why intangibles are the key to faster growth in Europe. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/why-intangibles-are-the-key-to-faster-growth-in-europe.

[9] See Center for Global Development (2022). The Rise of Star Firms: Intangible Capital and Competition. Available at https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/rise-star-firms-intangible-capital-and-competition.pdf.

[10] McKinsey. (2024). A microscope on small businesses. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/mckinsey%20global%20institute/our%20research/a%20microscope%20on%20small%20businesses%20spotting%20opportunities%20to%20boost%20productivity/a-microscope-on-small-businesses-spotting-opportunities-to-boost-productivity.pdf?shouldIndex=false

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Bernhard Dachs et al., EU wholesale trade: Analysis of the sector and value chains, European Commission, June 2016.

[14] Braguinsky, S., Choi, J., Ding, Y., Jo, K., & Kim, S. (2023). Mega firms and recent trends in the us innovation: Empirical evidence from the us patent data (No. w31460). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[15] McKinsey. (2024). (see note: 27)

[16] See Council Regulation 4064/89, on the Control of Concentrations Between Undertakings, 1989 O.J. (L 395) 1–12 (EC) [hereinafter Merger Regulation 1989], and Council Regulation 139/2004, on the Control of Concentrations Between Undertakings, 2004 O.J. (L 24) 1–22 (EC) [hereinafter Merger Regulation 2004].

[17] See, e.g, FWP (2019). Why the Siemens – Alstom rail merger was prohibited by law. Available at https://www.fwp.at/en/news/blog/why-the-siemens-alstom-rail-merger-was-prohibited-by-law.

[18] France, Germany, and other critics of current EU merger rules argue that these rules cause the Commission to adopt an overly rigid stance when assessing potential competition. Specifically, they contend that the time frame for evaluating potential future market entry should be extended. Currently, Commission guidelines state that market entry is generally considered timely only if it occurs “within two years.” See, e.g., Amory et al. (2019). Beyond Alstom-Siemens: Is there a need to revise competition law goals?

EU policy after Siemens/Alstom: A look into the right tools to preserve the EU industry’s competitiveness at global level. Available at https://www.concurrences.com/en/review/issues/no-4-2019/conferences/beyond-alstom-siemens-is-there-a-need-to-revise-competition-law-goals-new.

[19] Stockhaus (2015) outlined that he SIEC test relies heavily on the definition of the relevant market. This dependence can lead to arbitrary decisions and may not fully capture the competitive dynamics involving substitutes outside the narrowly defined market. See Stockhaus (2015). How Forceful is EU Merger Control? – the SIEC test meets the five forces. Available at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:855682/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Roeller and de la Mano (2006) highlight the difficulty in providing conclusive evidence of the test’s effectiveness, given the limited number of cases and challenges in establishing a clear counterfactual. They also criticise the negligible role that efficiency claims play in practical merger assessments, which undermines the potential benefits of the SIEC test. Despite the shift towards evaluating competitive effects, dominance still plays a significant role in assessments, sometimes overshadowing the intended effects-based approach. Additionally, the transition to the new test requires significant adaptation and expertise in industrial economics, leading to potential initial inconsistencies and application challenges. See Roeller and de la Mano (2006). The Impact of the New Substantive Test in European Merger Control. European Competition Journal. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/dgs/competition/economist/merger_control_test.pdf.

[20] Stockhaus (2015). How Forceful is EU Merger Control? – the SIEC test meets the five forces. Available at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:855682/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

[21] See, e.g., ITIF (2023). Why Merger Guidelines Must Do More to Support Productivity, Innovation, and Global Competitiveness. Available at https://itif.org/publications/2023/05/03/merger-guidelines-must-do-more-to-support-productivity-innovation-global-competitiveness/.

[22] Ibid

[23] Dennis W. Carlton & Ken Heyer, Extraction vs. Extension: The Basis For Formulating Antitrust Policy Towards Single-Firm Conduct,4 Competition Pol’y Int’l 285, 285–86 (2008).

[24] General Court of EU. The General Court largely dismisses Google’s action against the decision of the Commission finding that Google abused its dominant position by favouring its own comparison shopping service over competing comparison-shopping services Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2021-11/cp210197en.pdf

[25] Pre-stressing steel includes long curled steel wires that is used to make foundations, bridges and balconies. The companies fixed individual prices and quotas and exchanged sensitive commercial information and monitored price and quota arrangements through national coordinators and contracts, which is a breach of Article 101 of TFEU. see: Antitrust: Commission fines prestressing steel producers € 269 million for two-decades long price-fixing and market-sharing cartel (2011). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_11_403

[26] Commission fines pharma companies €13,4 million in antitrust cartel settlement (2023) Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_23_5104/IP_23_5104_EN.pdf

[27] Antitrust: Commission fines car manufacturers €875 million for restricting competition in emission cleaning for new diesel passenger cars (2021). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_21_3581/IP_21_3581_EN.pdf

[28] Suominen, K., (2020, October 26). On the Rise: Europe’s Competition Policy Challenges to Technology Companies. CSIS. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/rise-europes-competition-policy-challenges-technology-companies

[29] European Commission, Case M. 6166, DEUTSCHE BÖRSE/NYSE EURONEXT, Commission Decision of February 1, 2012. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_12_94/IP_12_94_EN.pdf; also see: General Court of European Union. The General Court confirms the Commission’s decision prohibiting the proposed merger between Deutsche Börse and NYSE Euronext. Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2015-03/cp150032en.pdf

[30] Adam Howorth, the company spokesman, said, “It’s disappointing the European Commission is advancing baseless complaints from a handful of companies who simply want a free ride, and don’t want to play by the same rules as everyone else,” in Scott, M., and Dorpe, V., (2020, June 16). Apple thrust into EU antitrust spotlight. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-opens-two-antitrust-probes-into-apple/

[31] European Union. (2019). Competition policy for the digital era. Publications for the Digital Era. Available at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/21dc175c-7b76-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1/language-en; also see: Suominen, K., (2020, October 26). (See note: 48)

[32] Ibid

[33] These practices are addressed under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and are a highly contested area of European competition policy. For example, the Commission has taken the stance that offering low prices in the form of loyalty rebates may be deemed anti-competitive behaviour.

[34] In contrast to the US, which views loyalty rebates as a pro-competitive business practice, European authorities are concerned that dominant companies may exploit their market position by offering discounts that prevent equally efficient competitors from competing for consumer demand. This debate came to a head in 2009 when the European Commission ruled that Intel had abused its market dominance through loyalty rebates, a decision later overturned by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). However, the case highlighted the European perspective that loyalty rebates can harm competition and consumers, primarily serving to shield less efficient competitors from their own competitive shortcomings. See, e.g., Suominen, K. (2020) (see note: 48); Intel Corp. v European Commission. Appeal — Article 102 TFEU — Abuse of a dominant position — Loyalty rebates –– Commission’s jurisdiction — Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 — Article 19. Case C-413/14 P.

[35] A Franco-German Manifesto for a European industrial policy fit for the 21st Century.(2019) Available at: https://presse.economie.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/fd32d63828617cc973af75261e66209d.pdf

[36] European Commission (2019). Mergers: Commission prohibits Siemens’ proposed acquisition of Alstom. 6 February 2019. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/it/IP_19_881. The European Commission has prohibited Siemens’ proposed acquisition of Alstom under the EU Merger Regulation. The merger would have harmed competition in markets for railway signalling systems and very high-speed trains.