Financial Repression and the Debt Build-up in China: Is There a Way Out?

Published By: Miriam L. Campanella

Subjects: Far-East

Summary

China’s old recipe book for economic success, based on market distorting policies, is hindering the process toward a market-driven economy and the chance of being granted Market Economy Status (MES). The consequences of policy passivity may derail China into the middle income trap and pose severe uncertainty to global markets. As China’s debt keeps mounting, particularly due to financial repression, mere domestic monetary reform may not be enough and may further harness the transition. Given China’s fiscal and financial space, prudent fiscal policy, along with an acceleration in domestic economic reforms, can improve the social safety net, promote consumer confidence and spending and may be the most effective way to balance the China’s economy and make its finances stable.

Introduction

China’s economic rebalancing stands at the centre of global economic attention. In a way, slower manufacturing output, higher domestic consumption and the increasing importance of the services sector seem to suggest China’s transition to a demand-driven economy is steadily progressing. However, data on a slowing economic activity, in itself a natural part of a rebalancing economy, are subject to interpretation and few would concur that China is rebalancing as fast as it should. Moreover, while China’s rebalancing is important for the health of the world economy, failure to generate positive consequences from it trigger concerns about one of its consequence – falling rates of growth. Last year a McKinsey survey of executives found that respondents widely cited the slowdown of China as the riskiest factor for the future, along with geopolitical instability. At every investment conference on Asia and China today, there will be repeated references to “zombie” firms and overcapacity in manufacturing and heavy industry, and how they prevent China to sustain economic growth at the current level.

The worst may be yet to come, however, and China’s leadership should prepare itself for tougher international scrutiny. Its mixed economy, with a significant role of the state in the business sector, causes legitimate concerns, and not just about rebalancing. They are now at the heart of China’s ambition to earn so-called Market Economy Status (MES). Other leading trade powers, however, do not seem to share China’s view of itself as a market economy. The row centres upon the terms of China’s agreement of accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, which China has long interpreted as automatically entitling the country MES by the end of 2016, 15 years subsequent its formal accession to the WTO.

The Obama Administration and several European governments, under pressure from businesses and trade unions at home, are concerned about the impact of Chinese imports on jobs and are so far rejecting automatic MES recognition. Political opposition to Chinese MES graduation has also emerged from Members of the U.S. Congress and European Parliament; the latter institutions recently rejected MES graduation it in a non-binding vote. The final result remains to be seen. Some in Europe are willing to award China MES on substantive grounds. Others are eager to attract Chinese investments and opposition to granting China MES may eventually crumble in the face of China’s check book diplomacy. However, China’s government will still have a hard time convincing others that it is reforming its economy and reducing the role of the state in a way that creates better terms for competition and foreign firms.

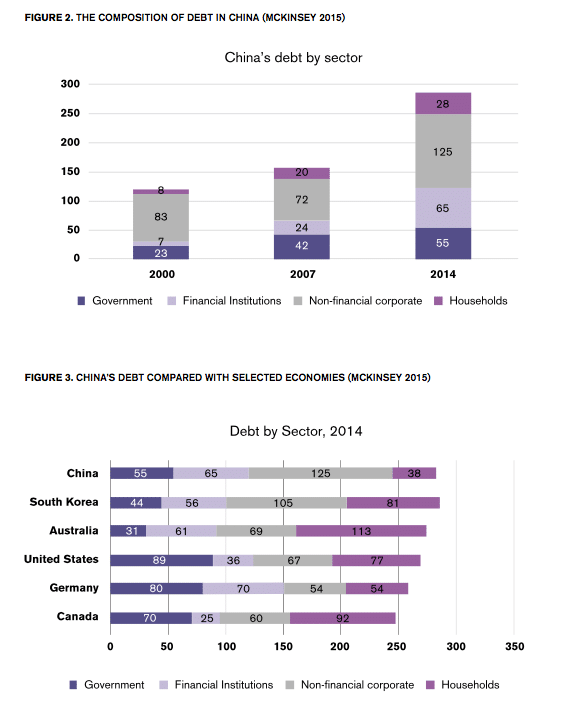

Indicators of overcapacity and subsidies to certain industries feed the suspicion that China is not rebalancing its economy fast enough – and, regardless of WTO definitions, that it does not work as a market economy. The Wall Street Journal recently documented how public companies in China get billions of dollars in cash assistance from the Chinese government, electricity subsidies, and other benefits. “Recipients include steelmakers, coal miners, solar-panel manufacturers, and other producers of other goods including copper and chemicals”, the Journal noted (WSJ, May 9 2016). Despite general overcapacity problems in world commodities markets, China has seen continued export growth of key products such as steel and aluminium. Both American and European policymakers urge rapid changes in China and have issued threats of trade remedies against China’s steel exports.

China’s subsidies not only risk causing trade disputes, protectionism, and retaliatory actions. They also sit at the centre of the much-vaunted rebalancing of its economy. Fuelling credit to a saturated manufacturing sector and a market with low global demand also puts the country’s banking system at risk, and further dulls the government’s declared objective of re-allocating resources towards domestic consumption and domestic-driven industries, especially those in the services sector. The way China has regulated its financial sector has exacerbated economic imbalances and created vested interests that would be disadvantaged by economic reforms. China can rebalance its economy, but it will not happen without deeper economic reforms.

China’s subsidies not only risk causing trade disputes, protectionism, and retaliatory actions. They also sit at the centre of the much-vaunted rebalancing of its economy. Fuelling credit to a saturated manufacturing sector and a market with low global demand also puts the country’s banking system at risk, and further dulls the government’s declared objective of re-allocating resources towards domestic consumption and domestic-driven industries, especially those in the services sector. The way China has regulated its financial sector has exacerbated economic imbalances and created vested interests that would be disadvantaged by economic reforms. China can rebalance its economy, but it will not happen without deeper economic reforms.

Escaping the middle-income trap

China may go slow on its ambition to rebalance its economy, but it is increasingly troubled with the risk of getting stuck in the “middle income trap” – and for the country to avoid it, it needs to address the problems caused by its old model of growth. Cutting overcapacity and transitioning into higher value-added manufacturing, as Yiping Huang of the Peking University argues, is “a lifeline for China in avoiding the middle-income trap”. For him, “the transition to high income status is probably one of the most important economic questions facing the world today. Success can lift the living standards of 1.4 billion people. Failure may lead to economic and social instability in China and the world could lose one-third of its global economic growth engine” (Yiping Huang 2015).

For economists, a country becomes middle income when its GDP per capita reaches $US7,500. China entered this stage of economic development in 2014. What haunts the country’s economic-policy observers is that relatively few countries in the past three or four decades have graduated to achieve high-income status, or reached per capita income levels of over $US16, 000. As for China, its GDP is steadily losing steam and has gradually lost 2 percentage points on a yearly basis for a while now, but at same time China is approaching a median income of $17.000 when measured in purchasing-power parity. The timing of these developments signals that China is getting closer to the “middle income trap”. If that happens, China would end up joining the group of economies that caught up fast with frontier economies but failed to rise to the stage of being a high-income economy (Eichengreen et. al. 2013).

What is delaying China’s transition into a higher stage of market-driven growth? Every answer should start by pointing to the huge factor-market distortions in the Chinese economy, many of which have been enacted in the past decades by the Chinese government in the pursuit of growth. Those factors still spur the investment-driven economic model, and give powerful stakeholders a reason to thwart the process towards a market-driven model (Lardy 2008; Borst and Lardy, 2015). Importantly, government controls on energy, land use, and household savings have massively advantaged manufacturing investors. They have worked as a subsidy to domestic and foreign firms to relocate activities in the country. In the last two decades, control policies favouring investment over consumption and the services industry have made China’s export-led manufacturing sector a success story. However, these controls have caused financial repression. They generate resources which are captured by the government and transferred to state entities – and these resources amount to a big part of the nation’s wealth. Lardy (2008) argues that only the interest rate established by the PBoC for the whole Chinese banking system represents a hidden tax on household savings that equals “more than three times the proceeds from the only tax imposed directly on households—the personal income tax”.

Withdrawing this wealth from savers has compressed consumption, lowered capital investment to the private sector, boosted credit expansion and spurred the build-up of debt, now standing at about 228 percent of GDP. In the early stage of industrialization, financial repression aimed at curbing domestic consumption via low interest on deposits and that helped to create faster capital accumulation. As expected in the Gerschenkron model (Gerschenkron 1962), financial repression worked as an accelerator of Chinese industrialization.

Currently, this form of financial repression originates domestically via government-led policy (Lardy 2008; Johansson 2013), combined with external factors such as developed-country central bank policy based on “zero-bound” interest rates. In the current dollar standard, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s short-term rates and downward pressure on long rates through quantitative easing affect the countries in the dollar standard’s periphery. Since the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan have followed the same direction as the Fed, central banks in emerging markets economies, which have naturally higher interest rates, are forced “to use capital controls on inflows and repressive bank regulations to lower their domestic deposit rates of interest” (Schnabl 2012, McKinnon, and Schnabl 2013). In other words, emerging economies (including China) have to operate with interest rates that are excessively low. If they did not do that, McKinnon and Schnabl argue, they “would lose monetary control as foreign hot money poured in the recipient emerging market government would be forced [to] intervene to prevent its exchange rate from appreciating precipitously” (McKinnon, Schnabl 2013).

Financial repression and debt accumulation

The “double pressure” on the interest rate feeds self-reinforcing dynamics on both the interest and the exchange rates. While domestic authorities are unable to disentangle them, they have strong consequences on debt expansion in emerging economies. In China, low international interest rates have fuelled debt through onshore banks. The IMF (2013) finds that Chinese state-owned banks have served as intermediaries for corporate borrowing overseas through the provision of bank guarantees and letters of credit. The IMF notes: “Chinese firms have also taken advantage of low global interest rates through offshore bond issuance, which has increased substantially since 2010. Half of the debt issued abroad has been for operations in China. Since 2009, real estate developers have been the largest issuers of offshore bonds among nonfinancial firms”.

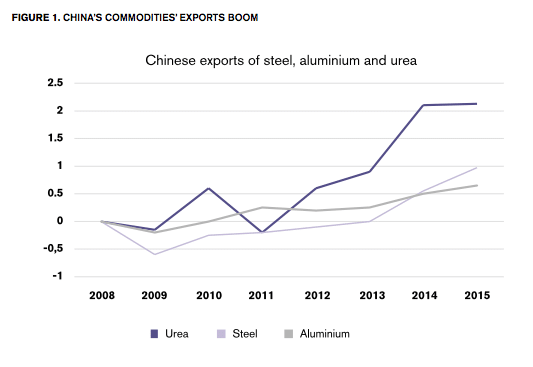

Debt accumulation in areas such as real estate, shadow banking, provincial governments and SOEs has nearly quadrupled since 2007, rising to US$28 trillion by mid-2014, up from US$7 trillion in 2007. At 282 percent of GDP, China’s debt as a share of GDP, while manageable, is larger than that of the United States or Germany (Figures 2 and 3). According to the McKinsey Global Institute (2015), overall indebtedness is concentrated in non-financial corporations.

Yet evidence of unsustainable debt exposures are clearly visible. In China’s financial markets, problems are just getting bigger. A recent Bloomberg article summed it up well: “Firms now take a record 192 days to collect payment for their goods or services from when they pay for the inputs, according to data compiled by Bloomberg on non-financial corporations traded in Shanghai and Shenzhen. The cash conversion ratio is up from 125 days five years ago. Liquidity is tightening in China after company profits declined for the first time in three years and as debtors face their hardest time ever paying interest.” And the article quote Iris Pang of Natixis “the longer the cash conversion cycle, the higher the risk of corporates not having enough cash to repay their debts.” (Bloomberg 19 April 2016). That the state-owned Dongbei Special Steel Group Co. recently defaulted on a RMB700 million repayment has been interpreted as a harbinger of bigger problems to come (Caixin 12 May 2016).

Concluding notes: Is there a way out?

Financial repression and the old model of economic growth is a root cause of China’s debt escalation. The country’s investment dynamics have been distorted and has now reached the stage where investments have neared their saturation point, a stage which indicates that “investments exceed the growth in debt-servicing capacity” (Pettis 2016a).

Fixing the debt problem by monetary policy or taxes on households and the tertiary sector is no viable future. As Pettis notes, such policies undermine “the most productive part of the Chinese economy” and reinforces the logic of financial repression because “allocating debt-servicing costs, either directly or indirectly, to specific sectors within the economy” is just a new form of an old habit, and it puts at the risk the transition to domestic-led economic growth.

Next to an acceleration of domestic economic reforms, Ben Bernanke has just re-hashed an older idea for China to manage both its economic transition and address growing debt problems: use fiscal policy. In crude form it means that China’s government should target fiscal policy to aid the transition in China’s growth. Importantly, that should not be done through spending on infrastructure like roads and bridges; that is part of the old growth model. Fiscal policy should rather aim to support emerging social safety nets, covering the costs of health care, education, and retirement. In this view, increasing income security in China would promote consumer confidence and consumer spending.

There are merits to this view. China certainly has the fiscal and financial space to improve the social safety net and help labour transition between sectors. Targeted fiscal policy could also help households to shift the balance between savings and consumption, and thus accelerate the rebalancing project. With a central government budget deficit at 43.9 percent to GDP in 2015, there is fiscal space for it as well.

Bernanke’s approach is an alternative to current monetary easing and new forms of financial repression, adding to old forms. If pursued, it has to be done with care. But it would help to shift the centre of gravity in China’s economy and put it closer to domestic sources of growth. Now, China’s old model is making the country economically vulnerable and without an end to instruments of financial repression, the country is just going to get even more exposed to financial imbalances and risks.

Bibliography

Bernanke B. (2016) China’s Trilemma – A Possible Solution, www.brookings.edu/blogs/ben-bernanke/…/09-china-trilemma

Bloomberg (2016) China Default Chain Reaction Looms Amid 192 Day Cash Turnaround, April 19 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-19/china-default-chain-reaction-looms-as-bills-take-192-days-to-pay

Borst, N. , Lardy N. (2015) Maintaining Financial Stability in the People’s Republic of China during Financial Liberalization. Peterson Institute of International Finance. WP 15 – 4 March 2015, https://piie.com/…/maintaining-financial-stability-peoples-repub…

Caixin (2016) Rash of Debt Defaults Should Spur Regulators to Act, 11 May 2016 http://english.caixin.com/2016-05-11/100942211.html

Eichengreen B., et Alii (2013) When Fast Growing Economies Slow Down: International Evidence and implications for China. Working Paper 16919 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16919

Gerschenkron A. (1962) , Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

IMF(2015) Corporate Leverage in Emerging Markets. A Concern ? https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/2015/02/…/c3_v2.pdf

Yiping H. (2015) The questions about China’s steady climb towards high income. EastAsia Forum11 October 2015 www.eastasiaforum.org/2015/…/the-questions-about-chinas-stea

Borst N. (2008) Financial Repression in China. PB 08-8. Peterson Institute of International Finance. https://piie.com/publications/policy…/financial-repression-china

Johansson Anders C. (2012) Financial Repression and China’s Economic Imbalances. Stockholm School of Economics CERC Working Paper 22 April 2012 https://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/hacerc/2012-022.html

McKinsey (2015) Debt and (not much) deleveraging. www.mckinsey.com/global…/debt-and-not-much-deleveraging

McKinnon R., Guenther S. (2014) China’s Exchange rate Currency, and Financial Repression: The Conflicted Emergence of the Renminbi as an International currency. CesIFO WP 4649. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_4649.html

Pettis M. (2016) Will China’s new “supply-side” reforms help China ?, blog.mpettis.com/…/will-chinas-new-supply-side-reforms-help..

Schnabl G. (2012) Monetary Policy Reform in a world of central banks.

Working Papers on Global Financial Markets. University Jena. N. 26 https://ideas.repec.org/p/hlj/hljwrp/26-2012.html

Schnabl G. (2015) China’s Exchange Rate and Financial Repression: The Conflicted Emergence of the Renminbi as an International Currency” Seminar to Economic Research Dept. and Emerging Economy Research Dept. Institute for International Monetary Affairs (IIMA) Tokyo. https://www.iima.or.jp/Docs/occasional/OP_No29_e.pdf

Wall Street Journal (2016) China Continues to Prop Up its Ailing Factories, Adding to Global Glut, 9 May 2016 http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-exports-surge-amid-overcapacity-at-home-1462746980