Europe’s Quest for Technology Sovereignty: Opportunities and Pitfalls

Published By: Matthias Bauer Fredrik Erixon

Research Areas: Digital Economy EU Single Market European Union New Globalisation Services

Summary

Covid-19 and its broader implications have highlighted the importance of Europe’s digital transformation to ensure Europeans’ social and economic well-being. It provides important new learnings about Europe’s quest for “technology sovereignty”.

While the debate about technology sovereignty is timely, the precise meaning of sovereignty or autonomy in the realm of technologies remains ambiguous. It should be noted that the political discussions about European technology sovereignty emerged far before the outbreak of the Coronavirus. The European Commission’s recently updated industrial and digital policy strategies “institutionalised” different notions of sovereignty, reflecting perceptions that more EU action is needed to defend perceived European values and to secure Europe’s industrial competitiveness. Often the political rhetoric reflected perceptions that Europe is losing global economic clout and geopolitical influence. It was said that dependency on technological solutions, often originating abroad, would require a European industrial and regulatory response. Against this background, the Corona crisis provides two important lessons for EU technology policymaking.

Firstly, during the crisis digital technologies and solutions made European citizens stronger. Technology kept Europe open for business despite the lock-down by enabling Europeans to work from home, receive essential home deliveries, home schooling, online deliveries and to use online payments, etc. In addition, Europe’s citizens became more sovereign with respect to accessing information and data that helped track and contain the spread of the virus.

Secondly, the crisis tested Europe’s resilience and perceived dependency on (foreign) technology solutions. Early developments indicate that Member States’ homemade solutions did not fare better than existing European and international solutions. A few national and EU IT solutions failed while existing European and global solutions, from cloud infrastructure to communications, payments to streaming services, all continued to work well.

Politically, however, the crisis could be used to justify more EU or national government interference in Europe’s digital transformation. Indeed, for some the debate about European technology sovereignty is largely about designing prescriptive policies, which paradoxically risk reducing Europeans’ access to the innovative technologies, products and services that helped Europe through the crisis. Policies taken into consideration include new subsidies to politically picked companies, or new rules and obligations for certain online business models. Policy-makers advocating for such policies tend to ignore critical insights from the Covid-19 crisis and failed industrial policy initiatives, including sunk public investments and protracted subsidies for industrial laggards.

In a time of economic hardship, the EU and national governments should be wary of spending even more taxpayer money to replicate existing world-class technology solutions, that in most cases are used in combination with local technologies, with “Made in EU” services of inferior quality and reliability. Moreover, due to different levels of economic development and differences in regulatory cultures, prescriptive technology policies would exclude many Member States from utilising existing and new opportunities that arise from digitalisation, slowing down economic renewal and convergence.

The EU cannot be considered a monolithic block that thrives on a unique set of prescriptive technology policies. Before the Corona pandemic, initiatives towards European technology sovereignty were mainly pushed by France and Germany, fed by concerns over their companies’ industrial strength in times of growing economic and geopolitical competition. Industrial and technology policies favoured by the EU’s two largest countries will have a disproportionately negative impact on Europe’s smaller open economies, whose companies and citizens could be deprived from cutting-edge technologies, new economic opportunities and partnerships on global markets, undermining these economies’ development and international competitiveness.

Any EU-imposed technology protectionism along the lines suggested by some policy-makers in large EU Member States would leave the entire EU worse off. It would disproportionately hurt countries in Europe’s northern, eastern and southern countries more than the large countries whose economies are generally more diverse than Europe’s smaller Member States.

It would, however, make sense for the EU to agree on a shared definition of “technology sovereignty”. Different interpretations could cause serious policy inconsistencies, undermining the effectiveness of EU and national economic policies. Anchored in technological openness, technology sovereignty can indeed be a useful ambition to let Europe’s highly diverse economies leapfrog by using existing technologies. To become more sovereign in a global economy, Europeans need to focus on becoming global leaders in economic innovation – not just in regulation. If anchored in mercantilist or protectionist ideas, technological sovereignty would make it harder for many Member States to access modern technologies, adopt new business models and attract foreign investment – with adverse implications on future global competitiveness, economic renewal and economic convergence.

Policymaking towards a European technology sovereignty that benefits the greatest number of Europeans – not just a few politically selected “winners” – should aim for a regulatory environment in which technology companies and technology adopters can thrive across EU Member States’ national borders. The European Single Market has deteriorated in recent years and significantly during the crisis. The new von der Leyen Commission has now repeatedly called for a strengthening of the Single Market. Becoming a world leader in innovation requires a real Single Market in which companies can scale up, with as few hurdles as possible, and then compete globally. It should be supplemented by pro-competitive policies and incentives for research and investment.

Brussels cannot set the global standards in technology policymaking alone. Europe’s policy-makers should aim for closer market integration and regulatory cooperation with trustworthy international partners such as the G7 or the larger group of the OECD countries. It is in the EU’s self-interest to advocate for a rules-based international order with open markets. International cooperation should be extended beyond trade to include cooperation on technology policies, e.g. artificial intelligence. Regulatory cooperation with allies such as the USA is essential to jointly set global standards that are based on shared values. Both the EU and the US have much more to gain if they prioritise such alignment, to advance a shared vision for a revamped open international trading system, in a world increasingly influenced by regimes with fundamentally different views on state intervention and human rights. Anchored in technological openness, the EU and the US can promote technology sovereignty that allows for development and renewal elsewhere in the world.

ECIPE gratefully acknowledges support to this study by the Computer & Communications Industry Association. The paper was completed in May 2020.

1. Introduction

Some leaders in Europe are calling for policies to promote “European Technology Sovereignty” or “Digital Sovereignty” (we use these terms interchangeably in this paper). The concept of technology sovereignty is not new – it has a long and chequered past – and its exact meaning is disputed. For some it is mostly about economic strategy, while others view technology sovereignty through the lenses of values, history or international public law.

It is obvious that economic success will never be the result of a policy that intends to make Europe independent of technological developments abroad, and – thankfully – there aren’t many politicians making the case for technology independence. It is equally obvious that such a conception of sovereignty does not sit comfortably in the European Union: for some EU countries, it would primarily mean independence from other Member States, leading to more friction in Europe. Consequently, a European policy of technology independence would imperil Europeans’ own economic future.

Fortunately, there are other ways to look at technology sovereignty and the purpose of this paper is to explore how Europe could improve its technology sovereignty while promoting technology openness. The two aren’t mutually exclusive: in a modern economy they rather reinforce each other. Our view takes aim at deepening the Single Market – which is still incomplete and fragmented by national regulations – and how that would improve Europe’s capacity to influence its own future. We will make the point that, for the economy and the protection of key values, Europe should encourage closer market integration and regulatory cooperation with key international partners, such as OECD countries. The transatlantic relationship will also be key, especially its combination of values, economic size and a place at the technological frontier(s). By working together, Europe and the US can set the market norms and the global standards. However, if both sides pursue competing standards, then neither side will be able to shape how a digital and technology-driven economy will influence them.

It is critical for Europe’s ability to shape its own technological future that European policy-makers cooperate with others. If the economic and societal consequences of Covid-19 and the pandemic have showed anything, it is that resilience comes from adaptability and reliance on a multitude of sources – not from autarkic policies or “putting all your eggs in one basket”. During the pandemic crisis, many different domestic and foreign actors have contributed to the supply of much-needed medical goods and food products, or taken actions to ensure basic services like telecoms and audio-visual services work despite enormous stress.

The Covid-19 crisis disrupted industrial value chains, while digital services continued to work, kept Europe open for business, more resilient and thus more sovereign. This was recognised by Werner Stengg, Cabinet Expert for Digital Policy to European Commission Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager, who stated in May 2020 that the “[t]he only thing that really worked during the height of the crisis was digital.” (Access Partnership 2020)

For a country or a regional entity like the EU, the capacity to effectively shape outcomes – to have effective sovereignty – depends crucially on policies and behaviour that harness the energy and ingenuity of many actors. The same conclusion holds for technology policy: Europe’s capacity to prosper on the back of technology comes from the ability of individuals, firms and governments to make use of frontier technologies in many different ways.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses notions of sovereignty and autonomy (occasionally independence) and their implications for policymaking. Section 3 explains the background to the current debate about a European technology sovereignty. We explore multiple origins of the debate, which we classify as the “4 Cs” – culture, control, competitiveness and cybersecurity. Section 4 discusses misguided industrial policy and the potential cost of an EU-imposed technology protectionism in the light of the EU’s new industrial and digital policy strategies. It provides recommendations on how the EU’s diverse Member States can become more sovereign from policies that embrace investment, encourage innovation and help facilitate structural economic renewal.

2. Sovereignty, Autonomy and International Economic Interdependence

What is sovereignty, and what does it mean in the context of technology and digital policy?

Obviously, sovereignty can have different meanings. At its core, it refers to having “supreme authority within a territory” largely corresponding with “political authority over a certain territory”.[1] The notion of “sovereignty” in the context of technology has been used in recent years to describe various forms of independence, control and autonomy over digital technologies, business models and contents. In France, for example, a popular view of digital sovereignty means “the control of our present and of our destiny as they manifest and orient themselves through the use of technologies and computer networks” (Bellanger 2011). According to the author of these words, it is a loss of sovereignty when the government does not control the evolution of digital networks (Couture and Toupin 2017).

In more general terms, sovereignty means that countries are “free to choose their own form of government” and that they are protected from interventions in their internal affairs by other countries (see, e.g., Besson 2011; Berger 2010; Krasner 2001). In this way, sovereignty for states became a rather straightforward concept enshrined in international law. However, it gets more problematic once sovereignty gets to mean something else, e.g. policy-makers suggesting that states are or should be truly independent from each other and free to make any decision about its affairs, even when it affects others. For a long time now, governments have cooperated and contracted with other governments about what rules that should apply in interstate relations. Even if governments can renege on their international obligations, they tend to accept certain limits on national sovereignty because alternative forms to govern intergovernmental relations come with negative consequences.

In international economic regulation, for instance, states agree with each other on specific behavioural codes of conduct – in everything from sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) rules to the conduct of competition policy. A good example is the European Union itself: in commercial policy, it establishes the rules of competitive behaviour. This is also true for digital and technology regulations. Even if such regulations remain incomplete, there are many international agreements – including bilateral trade agreements – that reduce the sovereignty of governments to make certain decisions.

The real ability to influence the future also depends on actual performance. To become more sovereign in an increasingly interlinked global economy, Europe needs to focus on becoming a global leader in economic innovation – not just a leader in regulation and good governance. As argued by Leonard et al. (2019),

[t]here is no such thing as technological independence in an open, interconnected economy. But an economy of 450 million inhabitants (excluding the UK) with a GDP of €14,000 billion can aim to master key generic technologies and infrastructures. The EU’s aim should be to become a player in all fields that are vital for the resilience of the economic system and/or that contribute to shaping the future in a critical way.

A popular way to think about sovereignty is based on autonomy. Jean-Claude Juncker, the former President of the European Commission, proclaimed in 2018 that now is the “The Hour of European Sovereignty”. (European Commission 2018) There is also much talk about “strategic autonomy” for the EU as a whole and such claims featured widely in the European election in 2019. While strategic autonomy was often thought of as a vehicle for closer European cooperation, it is notable that individual Member States also increasingly refer to autonomy in relation to big EU countries like France and Germany. For several Member States, strategic autonomy often means avoiding dependence on European economic and political powers.

For the European Commission, European autonomy largely means that Europe’s policy-makers retain the capacity to cater for European firms and advance Europe’s economic interests globally (European Commission 2020a, 2020b, 2020c). While this starting point makes sense, it immediately follows that Europe should focus on realistic opportunities for European policy-makers to shape – together with non-Europeans – the laws, rules and norms that will define digital performance, commercial cooperation and competition. In a digitised world with global value chains, autonomy simply cannot mean independence from others. It’s too costly. Trade controls, subsidies or industrial policy cannot substitute for the benefits that Europeans and others draw from technological and digital openness.

Global economic developments suggest that Europe has strong interests to collaborate with others. The centre of the world’s economic gravity is shifting. McKinsey (2019) suggests Asia will account for 50% of global GDP by 2040. Until 2050, says the PWC (2017), the EU and the US will steadily lose ground to the rising economies of India and China. The share of EU-27 gross domestic product (GDP) in global GDP will fall to some 9%, while US GDP is expected to stand at a somewhat higher 12% of world GDP in 2050.[2]

There are three important takeaways for Europe as policy-makers consider their options. First, neither Europe nor the US will be able to rely on their own market size as the main source of maintaining autonomy, sovereignty and influence in the global economy. Other countries, e.g. Japan, are confronted with the same reality. Rising powers like China and India may gain tremendously in market clout and increase political pressure on others to conform to their laws, rules and norms, but none of them will come close to the same dominance in global rulemaking that the US and Europe had in the period that followed the Second World War. Global economic power will be rather more distributed.

Most regions in the world struggle to improve data integrity and protect networks from intrusions – even when their governments are perpetrators.[3] Europe is not alone in wanting the behaviour of Internet users – governments, businesses and citizens – to follow fundamental rights. Similarly, Europeans are not alone in feeling that the economic payoff from digitalisation could improve. Several governments also feel that digitalisation is just a one-way street of benefits going to big technology firms. It is an opinion also shared among some American politicians, despite the US being the birthplace of internationally successful technology companies. However, it is a testimony to the current structural technology transformation of the economy that everyone seems to think they are a loser and that the winners are foreigners. In reality, the benefits of the digital economy are much more evenly spread across economies – proven by the uptake of ICT goods and digital services by consumers. After all, most of the economic benefits from new technologies and new business models are reaped where they are adopted.

The second takeaway point is that, with falling relative economic power, Europe will have to improve its capacity to influence global rules and performance by being home to innovative companies. When quantity does not count in its favour anymore, at least not in the way it used to do, Europe will have to improve regulatory skills at home to encourage innovation and become an example that others want to follow. With a 9% share in the global economy, Europe will become increasingly dependent on other parts of the world in the provision of frontier technology and digital services. Frankly, it is not possible to reduce global dependence at the same time as one’s relative economic size is falling.

The third takeaway point is that the Single Market is the source of Europe’s autonomy – and that it needs to deepen for autonomy to increase. Size matters, and with a larger economy that allows for cross-border commerce and technology development, Europe can make itself more attractive as a place to innovate and develop the future economy. Moreover, with more economic clout, the EU will also have a stronger voice to influence global norms and standards for technology.

[1] See, e.g., Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[2] Expectations of this shift are already strong. Even though the EU is still the world’s second-largest economy by GDP, only a few people globally actually consider it an economic leader ahead of the US or China. According to a PEW (2017) survey across the 38 nations, a median of just 9% considered the countries of the EU as the world’s leading economic power. 42% named the US and 32% pointed to China, while an additional 7% referred to Japan. It is noteworthy that even in the 10 EU countries covered by the survey, a median of only 9% viewed the EU as the world’s top economy.

[3] We view “data integrity” as overall accuracy, completeness and consistency of data, but also safety of data in regards to regulatory compliance, e.g. compliance with data protection regulations.

3. Major Root Causes of Europe’ Debate on Technology Sovereignty

Why is Europe exploring concepts of technology sovereignty – and why now? Motivations vary between observers. Many concepts of technology sovereignty revolve around data privacy, trust and reliable content (e.g. Popp 2019; Benhamou 2018; Goujard 2018; Pohlmann 2014). Some use sovereignty to make a case for addressing perceived challenges arising from certain technology companies (Gueham 2017). Others refer to consumer protection (e.g. German Advisory Council for Consumer Affairs 2017). A large body of the technology sovereignty literature is about artificial intelligence (e.g. DigitalGipfel 2018) and cybersecurity (e.g. Bonenfant 2018). Others refer to payment sovereignty (e.g. ECB 2019). Further notions relate to “general” access to critical technologies (e.g. Drent 2018) and “technology dependencies” in defence and general public procurement (e.g. Fiott 2018; FMIBC 2019; Lippert et al. 2019). Obviously, many of these motivations aim to define the concept of economic sovereignty.

There are, in our view, four broader factors behind the emergence of technology sovereignty as a desirable political ambition. These factors are summarised in what we call the 4Cs: culture, control, competitiveness and cybersecurity.

- Culture: the “cultural” approach to technology sovereignty starts from the assumption that Europe is different from other parts in the world in our defence of values and market regulations – manifested for instance in data protection rights. At the heart of this view is the perception that, in particular, digital regulation presents a fundamental choice between individual rights and business freedom, and that Europe has made its choice to protect human values and rights over business freedom.

- Control: there is a strand in the debate that takes a command-and-control view of technological sovereignty, arguing that the EU or individual Member States need to have the policy instruments to control the outcomes of the digital economy in general and how citizens and companies use modern digital services.

- Competitiveness: another viewpoint collects different thoughts and considerations around industrial competitiveness – the future capacity of European multinational enterprises to compete on world markets and fears about declining European influence vis-à-vis other standard-setting powers.

- Cybersecurity: finally, there is a growing demand for new policies to protect personal and business data, and to have at disposal all the tools and technologies necessary to protect digital integrity and digital resilience.

3.1 Culture and Control: A Static Approach to Regulation

3.1.1 Culture

The cultural approach to technology sovereignty – the first C – reflects two views that are often taken by European policy-makers to support certain regulatory approaches: first, the view that Europe is a monolithic block with respect to key values (all share the same preferences) and that these values are different from the values of other countries, e.g. China, the USA or Switzerland. It is assumed that if other countries regulate their digital economies in a different way than Europe, for instance, they do so because their values are different. And second, that digital and technology regulation often (but not always) is a choice between values and rights, on the one hand, and economic freedom on the other. Both views are reflected in the economic policy mandates of the executive branch of the European Commission (see Box 1).

Both views are misguided and see value conflicts where there are none. There are of course value differences in the world, and they can also manifest themselves in regulations. But the reality is that most governments in the world have converged quite substantially in how they regulate – and also in the motivations for why they regulate. Likewise, the conflict between individual rights and economic freedoms is an exaggeration. It is true that such conflicts over values sometimes arise, but what is more fundamental is that long-term economic freedom and economic success are indivisible for a culture that also promotes human integrity and individual rights.

An example of Europe’s value-based approach is the EU’s new digital strategy, Shaping Europe’s digital future. The communication was published by the European Commission in February 2020 and says it wants a “European society powered by digital solutions that are strongly rooted in our common values […]” (European Commission 2020b, p. 1). Furthermore, it argues that “[w]hile we cannot predict the future of digital technology, European values and ethical rules and social and environmental norms must apply also in the digital space” (p. 10).

Box 1: European Commissioners’ economic policy mandates in defence of European values

Sources: Letters sent by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (2019a, 2019b, 2019c).

These are good ambitions, but they are not novel or exclusive to Europe. Unfortunately, they all too often come at the expense of policy detail – and if there is one charge that can be made against this type of value-based policymaking, it is that it comes across as hollow grandstanding. In this case, notions of European values aim to guide a large package of legislation on data, artificial intelligence, industrial policy, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and the Single Market. Furthermore, these values intend to influence regulatory standards, public procurement and trade policy – all in the purpose of improving Europe’s global influence and the competitiveness of its industry. A similar policy motivation became obvious in the EU’s attempt to establish a Union-wide tax on certain digital services. Another example of how European values power political thinking was the attempt by the new Commission to have a Commissioner to protect the “European way of life” (“protecting our citizens and our values”).

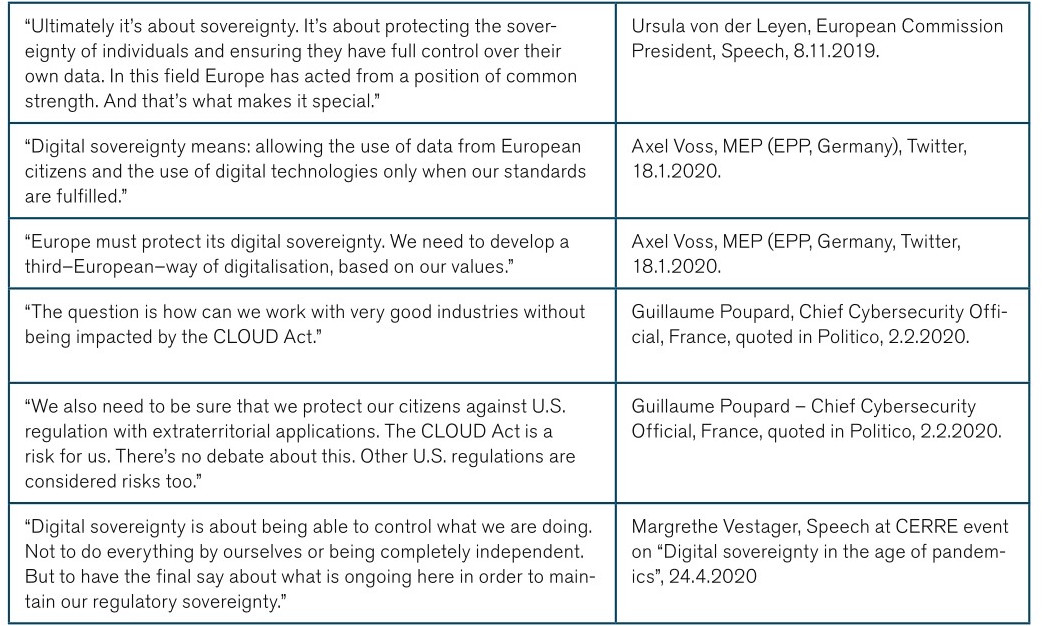

In the political guidelines for the new European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen stated that “[i]n this field [protecting the sovereignty of individuals and ensuring they have full control over their own data] Europe has acted from a position of common strength. And that’s what makes it special.” Referring to one of the Juncker Commission’s major political achievements, the adoption of a largely harmonised EU data protection regulation, the new Commission President wants to call out the willingness to maintain “our European way, balancing the flow and wide use of data while preserving high privacy, security, safety and ethical standards. We already achieved this with the General Data Protection Regulation [GDPR], and many countries have followed our path” (von der Leyen 2019d). In the debate about a European technology sovereignty, similar statements have been made by policy-makers from Member States and the European Parliament (see Table 1).

Table 1: European policymakers’ stated motivations for digital policies: culture

Source: ECIPE.

A good example to show how the real policy choice is often not about commercial freedoms versus individual rights can be found in the debate about the new policy ideas set out by the Commission in February 2020, in which the Commission acknowledges the general positive impact of digitalisation on Europe’s societies. The Commission recognises the need for substantial investment in the EU to narrow the gaps vis-à-vis China and the USA. But it is striking how different Commission documents take aim at different strategies, suggesting that there is severe clash between regulatory cultures within the Commission. While the (French) Single Market commissioner has set out a somewhat interventionist Data Strategy, the (Danish) Competition and Digital Strategy commissioner has launched more liberal approaches in her recent Digital Strategy and the White Paper on Artificial Intelligence. Recent discussions on European competition policy demonstrate that there are similar clashes between EU Member States on competition issues.

While Commissioner Vestager’s approach aims to spur competition, avoid market and data concentration, and create dynamic opportunities for Europe to benefit on the back of a global technology revolution, Commissioner Breton appears to see opportunities in an approach that creates market opportunities for those that would benefit from getting EU and national government protection against foreign competition. Commissioner Breton’s Data Strategy advances the idea of creating a European Data Space that may limit the participation of foreign providers of data services. It is stated that “for access […] use of data […] there is an open, but assertive approach to international data flows, based on European values” (European Commission 2020c, p. 5). A European data space would, it is claimed, improve security and trust, and “give businesses in the EU the possibility to build on the scale of the single market” (p. 17), while stimulating creators of industrial data to share this data more freely. As Europe hosts some of the biggest generators of industrial data in the world, it is said to have a comparative advantage in this field that can only be exploited if there is a higher degree of European control of the data infrastructure.

Data storage has become a bugbear for those who think that current market solutions do not respect European values. Germany now wants to create a cloud-computing platform, Gaia-X, that is, by origin, European and would work with rules that eventually can become the European regulatory standard. Many supporters of the initiative think this is the starting point for getting a cloud platform that is a better fit with European values.

Perhaps that is the case, but it remains unclear exactly what market problem that a “European” platform would resolve. After all, the idea of creating a European data space is not new at all. A few powerful European legacy operators and their national governments have, over the years, pushed similar ideas, e.g. a “Schengen area of data”. EU legislation is already in place to ensure the free flow of data in the EU Single Market (GDPR and the Regulation on the free-flow of non-personal data). Legal exemptions for allowing the flow of personal data from the EU to the rest of the world are few and under constant threat of invalidation.

But more to the point, European companies and public authorities can already today decide how and where they want to store their data, e.g. in-country or even on-premise. There are hundreds (if not thousands) of cloud service providers operating on the promise to exclusively store data within the border of EU Member States, e.g. nextcloud and owncloud (Stackfield 2019). Europeans have a much greater choice than they admit over where and how to store their data. It appears that the main reason is rather to fix a perceived commercial problem: that many of the most popular companies in the fields of data storage and processing are non-European. What is new is the political will in some EU Member States and in Brussels, to accommodate repeated calls by some national champions to stack market rules in their favour.

To be fair, Europe is not so different from other countries in its desire to safeguard data integrity. Most OECD countries already have or are considering high standards for data privacy and security. Accordingly, Europeans can rely on commercial solutions from a host of its partners in its quest for data integrity. Also, most actors, including European governments and industrial firms, take a far more sophisticated view on data security. They partner with several application and security vendors in a strategy to make it impossible for anyone who may get their hands on their data to actually make use of it. For those who store data that is covered by European data protection regulations, they routinely contract with their cloud providers about a strategy that comply with these regulations. These contracts rarely rest on the notion that data storage can only take place within one territory for the simple reason that the more data is distributed, the less it is concentrated and therefore less vulnerable. Data residency in itself does not equate IT security. The security of the data depends on the security governance and controls implemented, not on the localisation of the data. Data can be localised in a certain premise with a very low level of security.

It is notable how fast that some European policy-makers are jumping to the conclusion that radical measures are needed to create notional data sovereignty, reinforcing a misguided view that in order to create a greater digital autonomy, Europe must close itself off from the rest of the world. Europe’s digital sovereignty is rather based on the capacity to have access to key services and be independently capable to understand, use and alter these services, with the view of using it for the purposes of protecting rights and generating economic and social development.

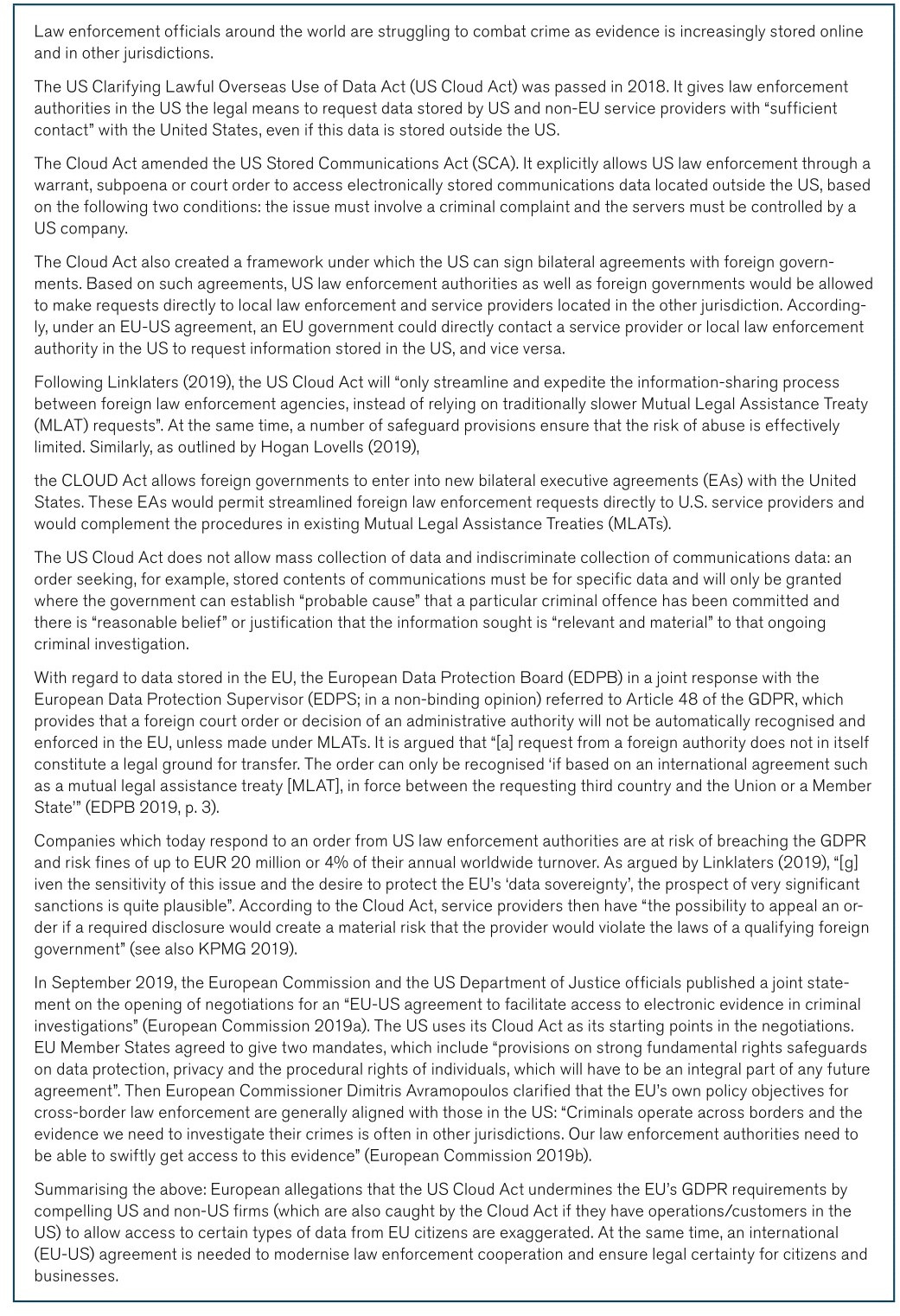

Supporters of European data spaces often argue that the US Cloud Act from 2018 allows for widespread snooping and mass data surveillance of personal data by US law enforcement agencies. That view is clearly exaggerated and misleading (see Box 2). European institutions and governments are in fact pushing for their own legislation to more effectively access data stored abroad in their criminal investigations. To make this work, the EU is conducting negotiations with US authorities for an EU-US cloud framework. This agreement would help European agencies to facilitate faster access to electronic (or data) evidence in criminal investigations. France, Germany and the European Commission have signalled that their ambitions are aligned with the US view and that there is a need to speed up data sharing between law enforcement agencies that have legitimate requests about data evidence stored in another country (European Commission 2019a).

This makes sense. As an open and export-driven economy, it is in the EU’s interest to advocate for a rules-based international order. An EU-US cloud framework assisting the investigation of serious crime would be in Europe’s interest. Yet the EU-US negotiations have stumbled and the EU still does not have a clear negotiation position, e.g. an adopted EU e-evidence legislative proposal. The US, on the other hand, is moving ahead with Cloud Act agreements with non-EU countries, e.g. the recent UK-US agreement and the agreement between the US and Australia (USDJ 2019a; 2019b).

Box 2: US Cloud Act, GDPR and the future of an EU-US agreement for e-evidence data-sharing

3.1.2 Control

The second C – control – is rooted in political desires to control technology and digital platforms that store Europe-generated data. It links up with some general attitudes around data protection. At the heart, however, it considers the reliance on foreign platforms and cloud providers to be a source of instability for data integrity: European firms and public authorities are considered victims. It is said that Europeans are forced to use foreign technologies and services because there are no European options.

Command-and-control approaches generally rest on a state-centric approach to digitalisation. Its core manifestation is reflected by the notion that the digital revolution has left Europe a bit stranded by making European firms less globally competitive and its governments less able to control the outcomes of markets and technological change. There is a sentiment that European blue-chip firms, in particular, are losing out to global tech giants and that there is inevitably a loss of competitiveness for Europe when the industrial heartland gets ever more dependent on data and services provided by these (foreign) firms (see Table 2).

Table 2: European policy-makers’ stated motivations for digital policies: control

Source: ECIPE.

Such perceptions are echoed in the European Commission’s recent strategy for governing data in the EU. The Commission sets out the ambition for the EU to become a leader in data innovation, but then wants to spend several billions of EU taxpayers’ money on replicating data infrastructure that already exists or which there appears no commercial demand for. A “key action” outlined by recent Data Strategy is to invest “in a High Impact project on European data spaces, encompassing data sharing architectures” (including standards for data sharing, best practices, tools) and governance mechanisms, as well as the “European federation (i.e. interconnection) of energy-efficient and trustworthy edge and cloud infrastructures (Infrastructure-as-a-Service, Platform-as-a-Service and Software-as-a- Service services)”, with a view to facilitating combined investments of “€4-6 billion”, of which the Commission “could aim at investing €2 billion”. (European Commission 2020c, p. 16)

Europe’s policy-makers should not expect European companies to become more innovative by embracing dirigiste – government-directed – policies. Data-sharing obligations can create the opposite of what was actually intended. In the European Commission’s White Paper on data it is argued that “data should be available to all”. However, the Commission does not take its own claim too seriously. A few lines below the radical vision of an open data space, it is argued that data should be “as open as possible, as closed as necessary”. Commissioner Breton also stated: “[w]hen we talk about data sharing, we’re not talking about essential data, because companies would never do it — and rightly so” (Politico 2020a). Indeed, many companies are unwilling to give away data, such as trade secrets, that are essential for their survival.

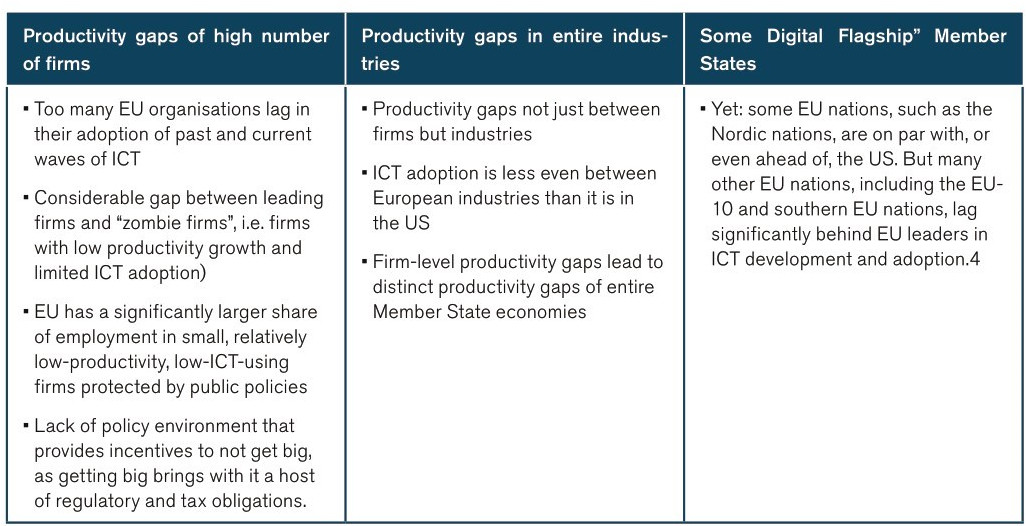

For some time now there have been growing concerns about the lack of speed in Europe’s digitalisation, especially on the corporate side. While Europe hosts many multinational firms that are at the frontier of the digital revolution, many SMEs have failed to seize digital opportunities and to make necessary investments. As a result, Europe is generally considered to lag behind many other advanced economies on key indicators for the adoption of digital technologies.

The concept of data sovereignty gets interesting in this context. Two things are obvious from economic research. First, many European firms do not have the autonomy and the opportunity to follow digital developments, let alone to be at its vanguard. There are critical problems for the provision of all the tools and instruments needed to be at the frontier – and many of them are based on the lack of supply of human capital (IT skills) and policy barriers to the supply of services across European borders (i.e. a Single Market problem). There is a significant shortage of computer engineers and labour with the right IT skills, e.g. in artificial intelligence. The lack of supply of educated labour naturally creates a wedge between large multinationals (that can draw on international supply and expertise) and the smaller home-oriented firms.

There are clear and direct policy implications that follow from these observations. None of them implies shutting foreign providers off from Europe. On the contrary, without them Europe would be even less sovereign when it comes to having the autonomy to access, understand and use digital opportunities. In the area of data, Europe’s policy-makers should rather work towards making more data publicly available, starting with public data, and then allow citizens to use the best infrastructure and software tools available to nurture the next wave of data innovations.

Secondly, and related, Europe can improve its own capacity by reducing the barriers to cross-border supply of digital services. Business statistics indicate that companies in the EU find it harder to grow compared to companies in the US. The average number of employees of a large US company is about twice as high as the average number of employees of a large company that is based in the EU. These numbers indicate that in the past it was generally easier for US companies to scale than for companies in the EU. This situation seems to persist: of the top 10 companies in the US, five are less than 20 years old, while all of the top 10 companies in Europe are more than a century old (CSIS 2020). Compared to companies in the EU, US businesses benefit from less legally restricted and therefore easier access to a greater US consumer base (Table 3). In other words: the United States Single Market is more complete than the common market shared by EU Member States.

Table 3: The EU’s distinct productivity performance gaps

Source: ITIF (2019).

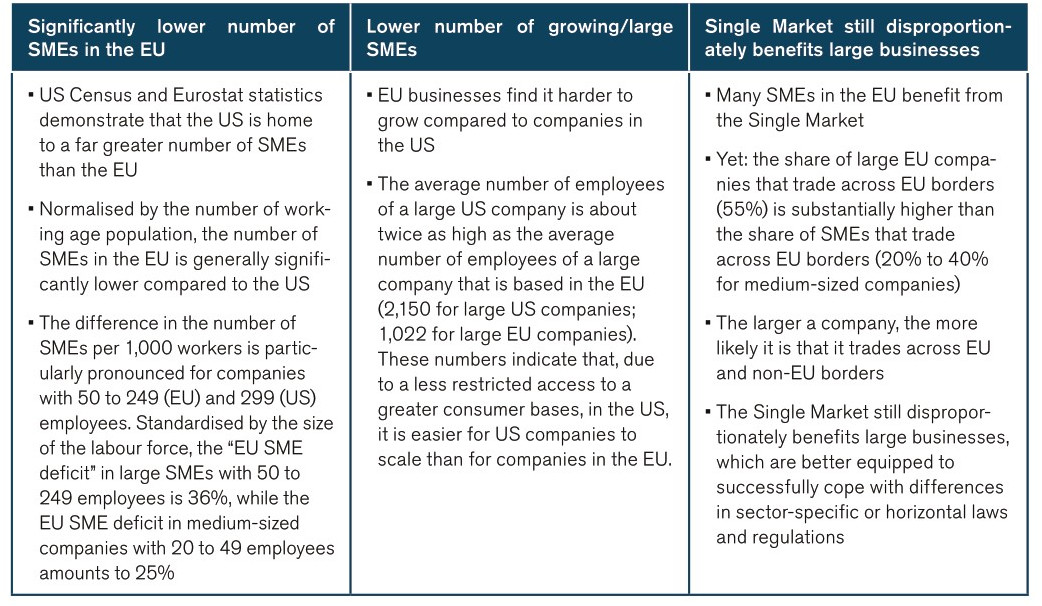

Similarly, most companies in the EU are SMEs (99%). However, business statistics also demonstrate that despite a much smaller total population, the US is home to a far greater number of SMEs than the EU. Adjusted by the size of the labour force, the number of SMEs in the EU is still significantly lower compared to the US. The EU’s “SME deficit” in large SMEs (50 to 249 employees) is 36%, while the EU’s SME deficit in medium-sized SMEs (20 to 49 employees) is 25% (Table 4).

Table 4: The EU’s distinct SME performance gaps

Source: ECIPE (2020).

In fact, a market that is more single will have a direct impact on reducing these gaps. A more complete single market would also close the gap between European firms at the frontier and those that are distant from the frontier. It would allow European SMEs and start-ups to innovate and scale to competitiveness. A more complete single market that encourages entrepreneurship would also increase the likelihood of “more radical innovation”: new firms that are more likely to commercialise radical innovation than incumbents.[1]

The importance of a real European Single Market is increasingly emphasised by the new Commission. In its 2020 Single Market Barriers report, the Commission acknowledges the “cost of non-Europe” and outlines a number of “frequently reported” policy obstacles and highlights Member States’ resistance to properly transpose, implement and enforce EU Directives (European Commission 2020f). However, it remains to be seen if these observations will form part of a powerful agenda for revitalising the Single Market and make Europe more friendly to digital investment and innovation.

Commissioner Vestager has pointed to the non-existence of a real European Single Market several times, and she has made the point that regulatory fragmentation is at the heart of Europe’s underperformance in digital industries. In her opening statement in the European Parliament Hearing in October 2019 on a “Europe fit for the Digital Age”, she praised the Single Market and the digitalisation of European economy. She argued that “our Single Market gives European businesses room to grow and to innovate and be the best in the world at what they do” (Vestager 2019). Vestager also stated that “as global competition gets tougher, we’ll need to work harder to preserve a level-playing field […] [b]ecause Europeans deserve an economy where companies compete to serve customers better not just to get bigger subsidies from government.”

In February 2020, Commissioner Vestager followed that up and said that “[o]ne of the reasons why we don’t have a Facebook and we don’t have a Tencent is that we never gave European businesses a full single market where they could scale up […] Now when we have a second go, the least we can do is to make sure that you have a real single market” (Politico 2020b).

Policy-makers in many European capitals have in the past objected the development of a complete and deep single market, and they have done so because it would entail a loss of control or a loss in national sovereignty on their part. For example, under the Juncker Commission the regulatory restrictiveness increased in many of the EU’s service industries, sectors that are relevant for cross-border commerce in the EU. EU and Member State governments defended national laws regarding these sectors and generally failed to give up on own regulations, with adverse effects on businesses using these services.

The EU’s exclusive focus on perceived digital barriers has created another problem. Current political rhetoric and the latest communications from the European Commission demonstrate that Europe’s political leaders are still largely ignoring the need to implement fully harmonised EU rules for trade in a truly common European market. The promotion of politically “easy-to-sell” digital policies distracted public attention and political capital away from the fragmentary nature of the Single Market. EU governments continued to use their legal competences to implement laws and regulations that, on aggregate, resulted in more differences (layers) in Member State regulations, increasing confusion and uncertainty for EU businesses and consumers respectively.

A more complete Single Market would essentially entail that countries and firms would make themselves more dependent on each other, which is the reality of modern business and the international division of labour. No firm can excel at everything and they have to draw on the inputs and services from others to be competitive. To increase the autonomy of firms – their capability to better manage their own future – they have to become less independent.

A recent example of command-and-control thinking in EU digital policymaking can be observed in the EU thinking of future regulation of artificial intelligence (AI). While European policy-makers have embraced the promises of AI, including in mitigating the Coronavirus and future pandemics, they have often started on a defensive note, fearing that the development may lead to outcomes they cannot control. A new idea that has been going around European capitals in recent time is the concept of establishing a sort of “conformity assessment” for AI, based on testing the applications before they can be marketed in the EU (European Commission 2020e).

There are some obvious practical implications of such an idea: there is generally an AI skills shortage in Europe, and this shortage is even stronger among government agencies. A process of ex-ante testing of AI applications risks becoming a time-consuming affair that will slow down the market entry of technologies that would help Europe’s industry to improve their performance and competitiveness. A bureaucratic EU AI testing system would almost guarantee that Europe would always run behind the USA and China in the global AI race, in particular for European SMEs with little capacity to handle administrative burdens. The proposed system will inevitably have adverse feedback effects on downstream sectors. As outlined in the EU’s 2019 R&D Investment Scoreboard: “Big Data and AI can be broadly applied in most sectors [of the economy]. Looking at the sector level, AI and Big Data are also most widely considered as highly relevant for future competitiveness” (European Commission 2019c).

Another concern is that the system will provide opportunities for the EU to deny market access for AI applications from other countries. It has long been established by economic research that a licence-to-operate procedure has negative consequences on competition and dynamic market behaviour, and there are clear risks of that kind in this case as well. Remove sufficient AI skills among authorities and there is a risk that the actual testing of foreign AI applications would be outsourced to firms in Europe that are competitors to the firm that apply for an AI market licence. This conflicts with EU policies to protect intellectual property rights and trade secrets, which are at the heart of Europe’s knowledge-driven economies.

Ex-ante conformity assessments would incentivise European companies to relocate to other jurisdictions, most likely the US, where they can launch immediately rather than wait for EU approval. The EU’s scarce AI expertise would be spent on testing the AI innovations created elsewhere. Non-EU technology companies would reconsider engagements in the EU because of high compliance cost, bureaucratic hurdles and the risk that their knowledge falls into the hands of potential competitors. From a dynamic perspective, mandatory conformity assessments would worsen the EU’s R&D investment gaps and exert a negative impact on European firms that are prevented from the application of Big Data and AI solutions.

The process forward for an effective form of control is to work with non-European governments that share Europe’s view of rights and associated regulations. A licence procedure only gives the semblance of being in control of the actual concern, while it provides ample opportunities to rig market rules and approvals in a way that lead to fewer opportunities for European firms to access AI applications on competitive terms. Fewer opportunities, together with potential retaliatory measures targeted at European businesses in non-European markets, would leave the EU with a profound loss of autonomy and sovereignty.

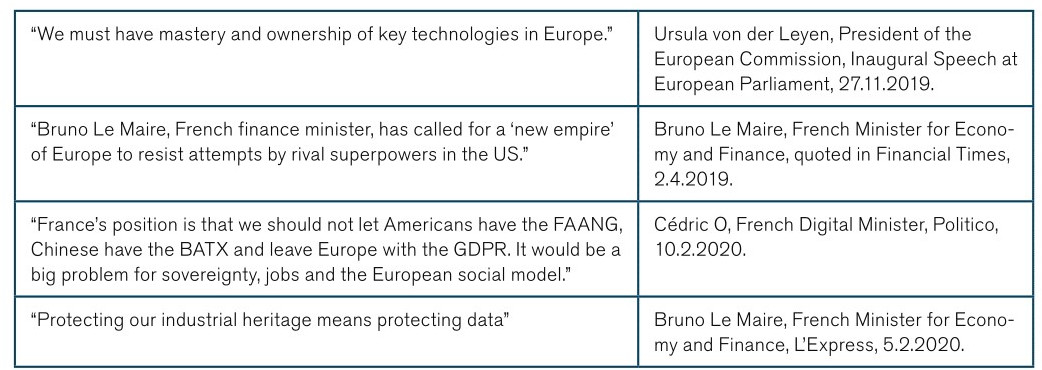

3.2 European Responses to Stronger International Competition: Competitiveness

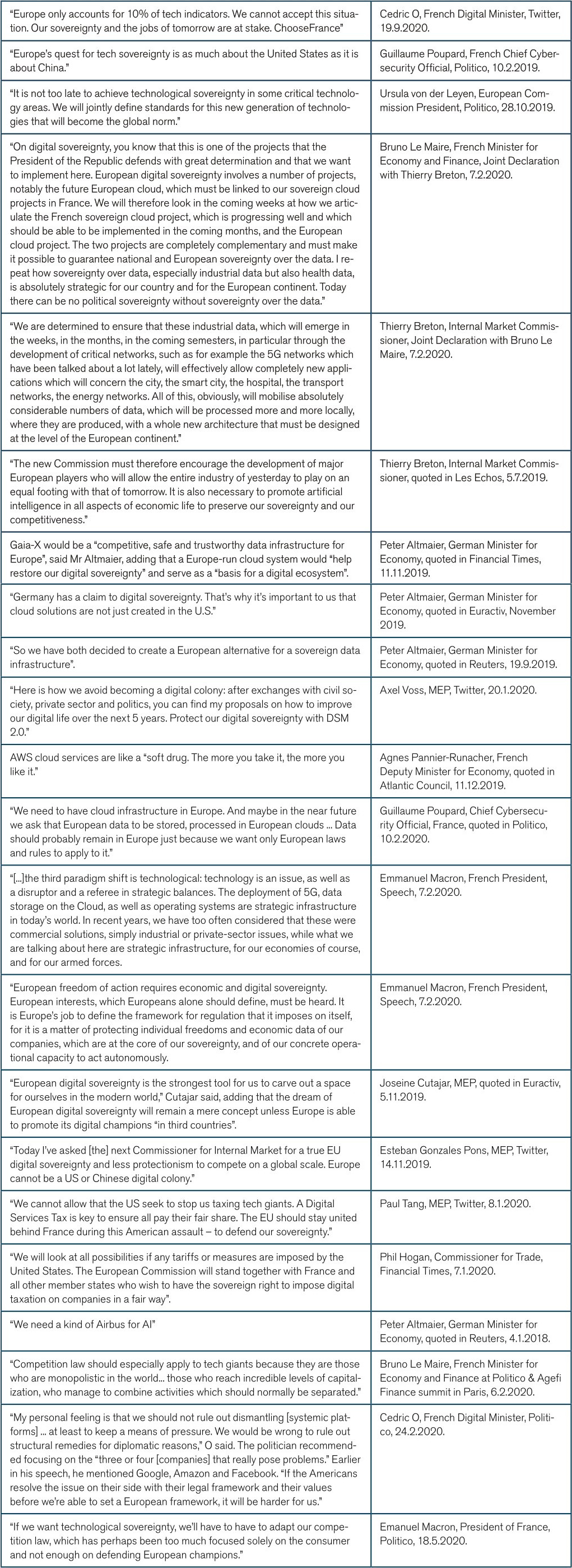

A major concern behind the calls for technology sovereignty is the fear of declining industrial competitiveness and international relevance – leading to less influence shaping new international standards for industries.[2] Our third C – competitiveness – thus reflects the widespread (but misplaced) anxiety that Europe is inevitably on the decline and that competitiveness can only be rescued by direct and indirect industrial support. In this section, we will take a closer look at some initiatives that are associated with such views, of which some manifestations are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5: European policymakers’ stated motivations for digital policies: competitiveness

Source: ECIPE.

3.2.1 Classic Industrial Initiatives

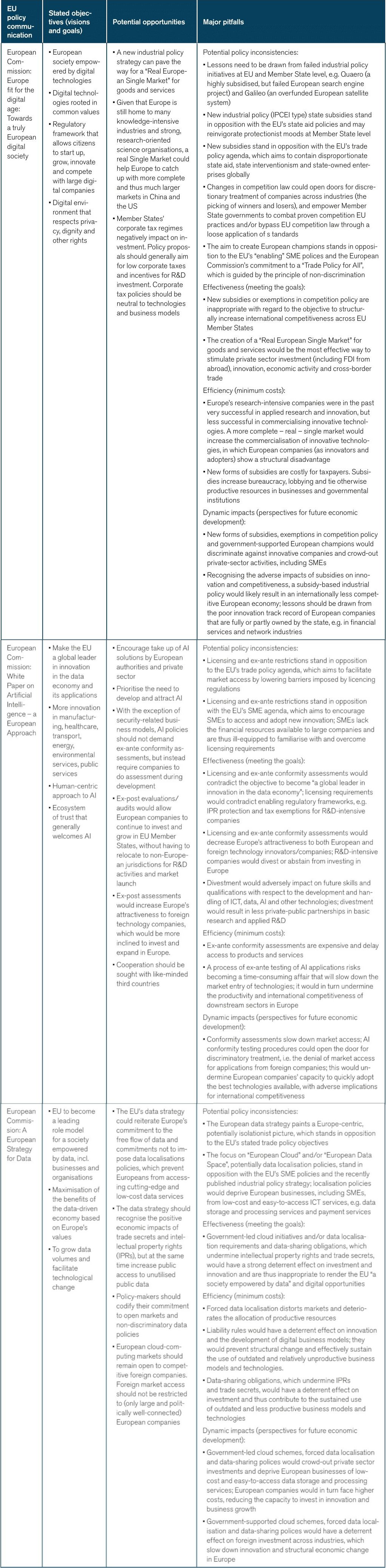

Policy-makers pointing to the “need to create” truly European industrial champions tend to disregard that many EU-based companies still hold very strong global positions in a wide range of industries. Similar to the US, EU patterns of specialisation and R&D activity remained relatively stable over the past decade (European Commission 2019d). Industry intelligence shows that European companies are still particularly strong in the automotive sector, environmental technologies and machinery sectors. Moreover, political claims regarding the lack of “European champions” – a frequent reference in the debate about European technology sovereignty – also neglect to mention that many technology and Internet companies, which successfully operate across the EU and globally, are actually headquartered in the EU, e.g. France’s Atos, Germany’s SAP, Poland’s Allegro, Sweden’s Spotify, Finland’s Wolt and many other (see, e.g. ECG 2020).

Companies in more traditional sectors such as carmakers are increasingly moving towards more digitised business models across their product and services portfolios. In the area of autonomous driving, for instance, numerous EU operators are partnering with international firms and taking part in autonomous vehicle (AV) testing abroad. The European Commission has welcomed such international cooperation for connected and autonomous vehicles. That, however, has not stopped some companies from proposing limits on AV competition and market access in the EU (see, e.g., El Referente 2019).

Despite these patterns and the general trend towards the digitalisation of traditional industries, the governments of France and Germany have taken the lead in shaping the design for new “all-EU” industrial policies. The influence has also shaped the Commission’s recent policy communications. However, complaints by smaller states about the drive for a new industrial policy is often passing unnoticed in Brussels. A recently launched campaign, led by the government of Lithuania, aimed “to stop Brussels’ focus on industrial strategy from stealing the show”. Marius Skuodis, Lithuania’s Vice-Minister for Economy, has said that the Single Market has been sidelined by discussions about the EU’s industrial policy (Politico 2020c). The governments of nine smaller Member States have underlined the urgency of the Single Market as a response to big-ticket industrial policy. Lithuania was joined by Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Ireland, Latvia, Estonia, the Netherlands and the Czech Republic. They have a point. Attempts to defend national industries have always clouded European attempts to create competitive markets.

3.2.1.1 European Data Sovereignty: European Clouds

The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, warned in a speech late last year about Europe having “dependencies” on foreign firms – predominantly US technology firms. Germany’s Economic Minister, Peter Altmaier, has argued that Europe “is losing part of our sovereignty” when firms and agencies have to store their data on cloud platforms such as Amazon and Microsoft (CDU 2019). Gaia-X would be a “competitive, safe and trustworthy data infrastructure for Europe”, said Altmaier, adding that a Europe-run cloud system would “help restore our digital sovereignty” and serve as a “basis for a digital ecosystem” (FT 2019). Gaia-X was created by the German Government and later supported by the French Government. It is however not (yet) an EU project and its outcomes remain unclear. This data governance project could potentially become a driver for cloud adoption, with high security and privacy standards, to the benefit of cloud services to public and private organisations.

Germany’s recent federal cloud data initiative, which aims to become the “cradle of a vibrant European ecosystem” was mainly “conceived and drawn up” by representatives of Germany-based firms. France’ Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire recently stated that France has enlisted tech companies Dassault Systemes and OVH to “break the dominance of U.S. companies in cloud computing” (Reuters 2019).

3.2.1.2 European Payments Sovereignty

Launched in November 2019, around 20 European banks from eight Eurozone countries are now supporting a new European payment system to challenge leading non-European payment services providers such as Visa, MasterCard, AliPay, Apple, Google and WeChat Pay. Banks headquartered in Germany and France make up a large share of this “European Payment Initiative” (EPI) project membership. A decision on whether or not to pursue the EPI is expected at the earliest in mid-2020.

The EPI project enjoys strong support from the European Central Bank (ECB), which for a long time has criticised the inability or unwillingness of European banks to develop a pan-European payment system. In 2010, 12 banks from eight countries joined the Monnet project, a consortium aimed at creating a European card scheme. The Monnet project was initially launched by major French and German banks but the project failed shortly after over lack of clarity on a sustainable business model.[3]

Renewed motivations for pursuing a regional European payments player with global reach are multi-faceted, with geopolitical considerations understood to be one of the key catalysts. On 26 November 2019, Benoît Cœuré, the former French Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, welcomed that Europe’s banks are consolidating efforts to set-up a new pan-European payment system. Cœuré warned that

[d]ependence on non-European global players creates a risk that the European payments market will not be fit to support our Single Market and single currency, making it more susceptible to external disruption such as cyber threats, and that service providers with global market power will not necessarily act in the best interest of European stakeholders.

He added that Europe’s “[s]trategic autonomy in payments is part and parcel of the European agenda to assert the euro’s international role.” At the same time, Cœuré admitted that consumers increasingly demand payment services that work across borders and that are faster, cheaper and easier to use (ECB 2019).

Similarly, in March 2019 the European Commission was reported to be considering new regulations to support and accelerate the adoption of the ECB’s new instant payments settlement system in an effort to challenge popular card and technology companies in Europe. In June 2019, the Commission formally announced that it was exploring policy options to strengthen the role of the euro and bolster its global relevance, and to “increase the autonomy of payment solutions in Europe and challenge the dominance of American and Asian apps and cards that Europeans use for their cross-border payments” (European Commission 2019). Similar to the ECB, Dombrovskis added in March 2020 that “[p]ayments matter because they are also a way to boost the international role of the euro”.

However, an EU-only retail payment system will hardly reinforce the international role of the euro. Nor will it provide the EU with a new option, which already exists with Instex[4], to allow for some trade with countries when there is, for example, an EU-US divide over sanction policy. Also, retail banking or payment systems have not been subject to blanked prohibitions under US sanction policy.

Moreover, payment networks and users of payment services alike are interested in network security and resilience, data protection and trust as well as transactional efficiency and innovation. Users go to these networks partly because they offer resilience and high levels of security. Policy-makers promoting purely European infrastructure solutions, such as the EPI, need to be clear about this. International payment networks have the ability to route via multiple data centres around the world: local systems usually don’t. International networks can rely on access to global data for cyber threat analysis, which allows for the detection of fraud outside of Europe in order to react faster to threats to Europeans. In a world where crime, especially cybercrime, travels across borders, national or siloed payment systems are more vulnerable to attacks because they lack global analytics and real-time global warning systems. Globally organised cybercrime, like cash-out attacks, are more likely to be detected and/or prevented through real-time analytics of big data, e.g. through a “rich global data lake of retail banking activity” leveraging machine learning and artificial intelligence (FICO 2018, Enisa 2016).

Consequently, a European payment initiative will not improve privacy or the security of payment data. The geographic location of data has no bearing on the security of that data, neither does it increase data privacy. Data security critically relies on the security systems and protocols that organisations have in place, regardless of where the data is stored.

Moreover, a purely European approach – in the name of technology sovereignty – would slow down innovation. For example, European FinTech players, such as Revolut and Klarna, benefit from their collaboration with global payment networks, particularly as it facilitates their expansion beyond European markets. The continued success of European FinTechs hinges on working collaboratively and interdependently with leading global companies.

If Europe wants to stay ahead in payment innovation and encourage the emergence of European FinTech players, it is better to promote innovation and set open standards that facilitate collaboration and exchange, rather than build new infrastructure and/or seek to regionalise the payment value chain. European regulation, such as the Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2), through a focus on standard setting, has already paved the way for open finance to flourish and created new opportunities for innovations that consumers need and want to adopt. However, Europe’s homegrown FinTechs all largely operate within their own national borders, without a Single Market in retail banking or payments. Therefore, attention should be given to removing obstacles to allow these EU FinTech players to develop across national borders and become pan-European players.

3.2.2 Protectionist Interpretations of Technology Sovereignty

Even though there is little detail about concrete policies, the EU’s Industrial Policy Strategy seems to be guided by fears of being locked in a US-dominated cloud space without any European champion. It is therefore no surprise that some initiatives run the risk of stoking European protectionism. It is equally unsurprising that foreign governments have identified that threat.

However, the Covid-19 crisis has shown that reliance on foreign technologies is not a threat to European autonomy. First, during the confinement period technologies and tech companies made Europeans – and their governments – stronger. Technology kept Europe open for business despite the lock-down by enabling Europeans to work from home, access to computing power via cloud solutions, receive essential home deliveries, home schooling, online banking, etc. Europe’s citizens became more sovereign with respect to accessing information and authorities used data to track and contain the spread of the virus.

Secondly, the crisis tested Europe’s resilience and perceived dependency on (foreign) technology solutions. Early findings indicate that homemade solutions didn’t fare better than existing European and international solutions. For example, a remote teaching tool by the French government failed to offer support for all those that needed online teaching. A few national prestige solutions failed while existing European and global solutions, from cloud infrastructure to communications, payments to streaming services, all continued to work. Many tech companies have acted swiftly to address concerns, e.g. by reducing bandwidth consumption to avoid congestion.

Obviously, some politicians might ignore this new evidence and capitalise on the crisis by calling for a more protectionist understanding of technology sovereignty. Policy-makers should however recognise that Europe benefits substantially from the technologies and services offered by innovative, domestic and foreign, technology companies. A misguided attempt to hinder access to the most popular foreign tech companies would leave Europe with less competition, less choice and less access to innovation.

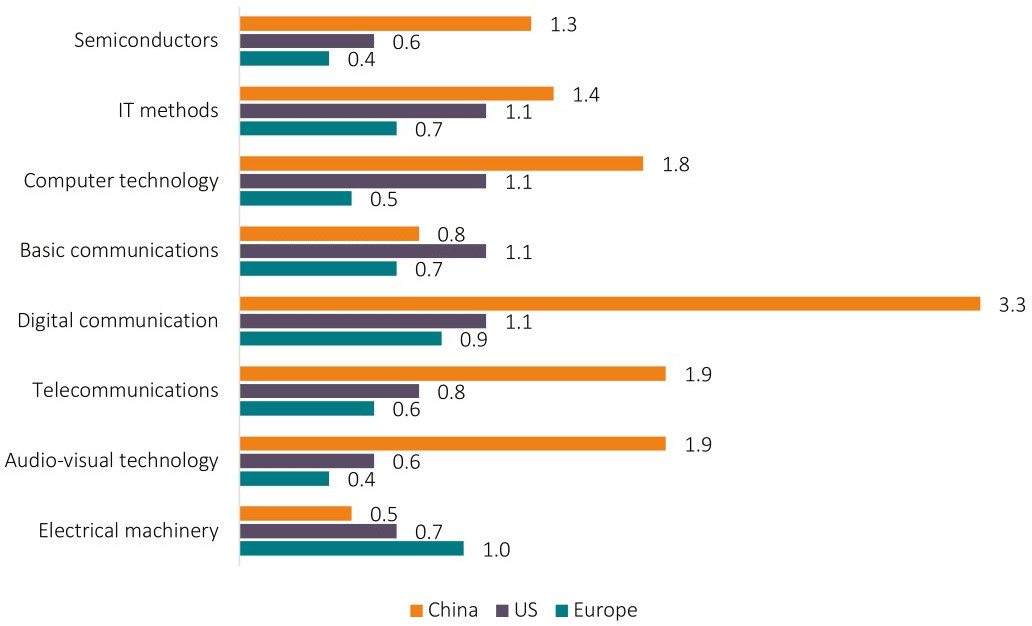

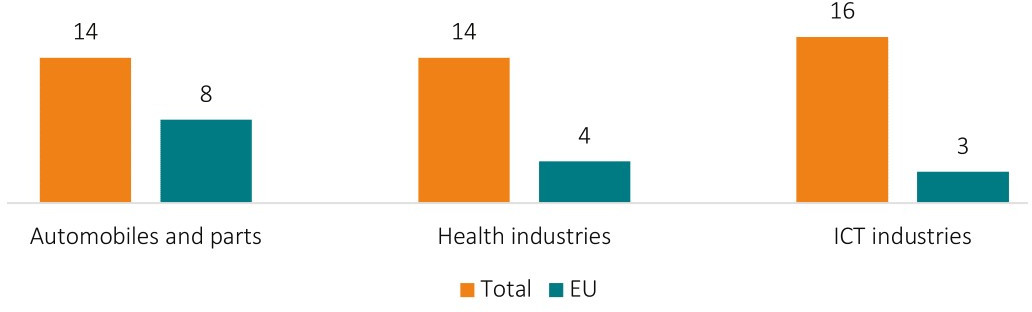

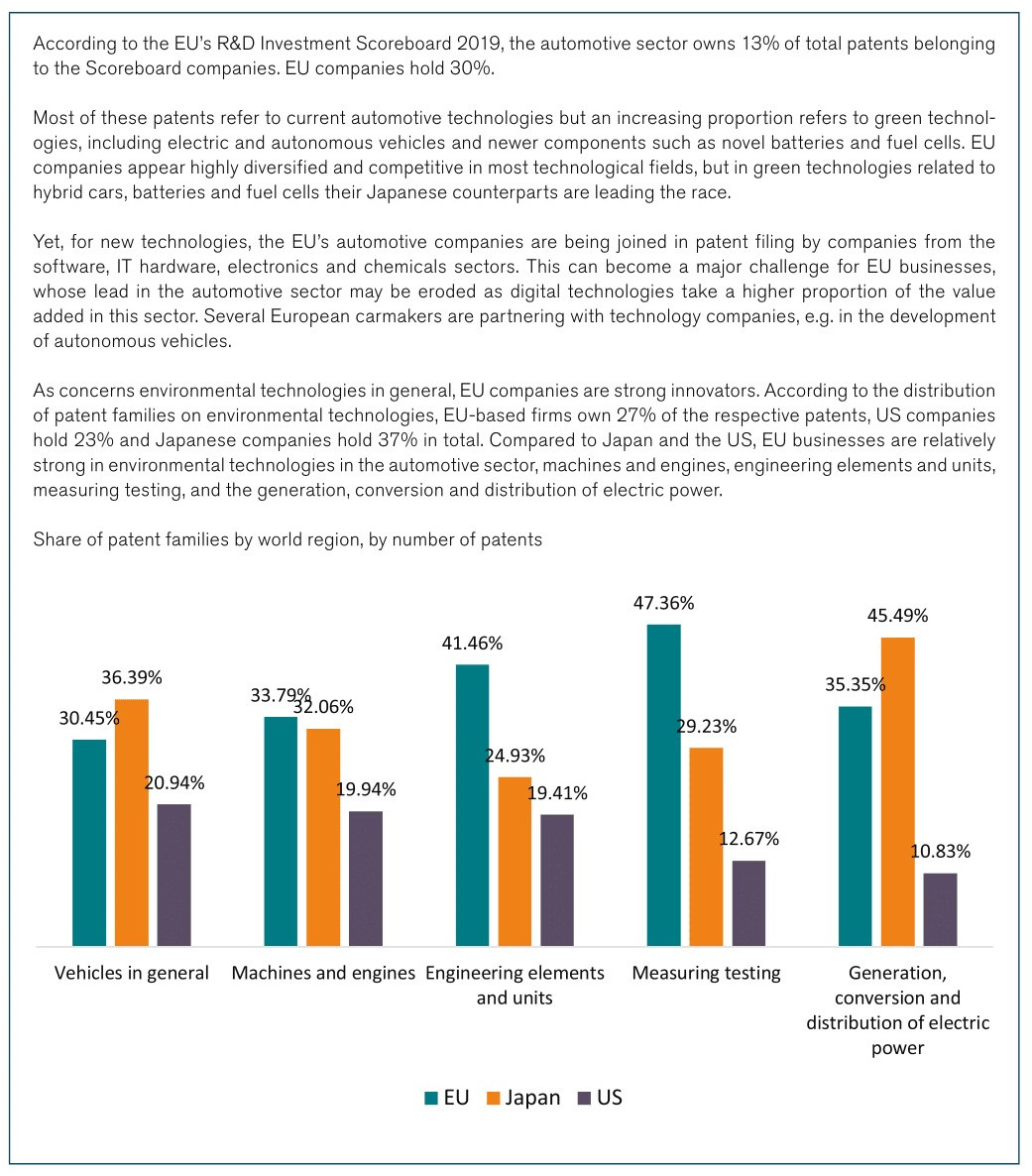

A recently published report from the EU’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the OECD, for example, comes to the conclusion that EU businesses are indeed significantly lagging behind in terms of their innovative capacities. Based on data for patents, trademarks and scientific publications of the world’s top corporate R&D investors, JRC-OECD (2019) investigates the role of key industry players in shaping the future of technologies, and of AI in particular. It is shown that until 2016, businesses in the EU-28 and Switzerland continued to be specialised in largely the same fields of technology as in 2010-2012. It should be noted that the same pattern holds generally true for US-based companies, which continued to be specialised in the exact same technologies in which they were specialised in 2010-2012. As outlined by Figure 1, US (and Chinese) companies outperform European companies (EU-28 and Switzerland) in new (ICT and AI) technologies that are increasingly important for more traditional sectors.

These are sectors in which European companies are currently relatively strong, e.g. automobiles and parts, healthcare, environmental technologies and machinery equipment (as outlined by Figure 2 and Box 3). Europe’s automotive and other transport sectors perform the largest proportion of their R&D activities within the EU. Based on the very strong past performance of the EU’s automotive sector and the high specialisation of the EU, more than 90% of the research activities still take place in the EU. On the other hand, European companies show a significant technological disadvantage in semiconductors, IT methods, general computer technologies, basic communications technologies, digital communications technologies, telecommunications technologies, audio-visual technologies and electrical machinery.

With regard to new technologies, as outlined by the EU’s 2019 R&D Investment Scoreboard, “Big Data and AI can be broadly applied in most sectors [of the economy]”. Looking at the sector level, AI and Big Data are also most widely considered as highly relevant for future competitiveness, with being among the top three technologies in six out of eight sectors. These technologies will have the most diverse application possibilities. This can also be seen in the joint study of the JRC and OECD on patents in the field of AI, where AI is both widely used but also developed in sectors that are traditionally low ICT-intensive. Other ICT-related technologies are considered as much less important for future competitiveness. The relevance of other technologies, such as I4.0 and Robotics, is much less widespread. ICT services and ICT hardware technologies are not mentioned amongst the most relevant technologies for future competitiveness in any of the sectors. Europe’s current technology gap in many ICT or digital technologies may thus put at risk the international competitiveness of companies that are still strong in traditional, less digitalised industries, such as Europe’s carmakers and machine manufacturers.

Figure 1: Revealed technology advantage (RTA) of world’s top R&D investors, 2014-16, by field of technology and geographical location of headquarters

Source: JRC-OECD (2019, p. 30). Note: RTA indices were compiled for the major economic areas where the top worldwide R&D investors have their headquarters. The index value is computed using the IP5 patent families. The RTA is defined as the share of patents in a field of technology for an economic area, divided by the share of patents in the same field at the global level. The index number is zero companies headquartered in an economic area hold no patent in a given technology. The index value grows with the increase of the patent share in the given technology.

Figure 2: Distribution of the top 50 companies by main industrial sector, 2018

Source: EU R&D Investment Scoreboard 2019.

Box 3: EU-based companies hold a strong position in the automotive sector and in environmental technologies

Source: EU R&D Investment Scoreboard 2019.

Industry data indicate that the EU performs poorly with respect to R&D activities and the number of companies that successfully commercialise digital technologies and business models. The European Commission is generally right in arguing that a different regulatory framework and new policies are needed to secure the competitiveness of key European sectors, including ICT and digital industries. However, current perceptions on a European technology sovereignty are unlikely to remain static. The next wave of technological innovation, which, according to ITIF (2019, p. 3), “holds the potential to reverse the 20-year productivity growth lag [in and beyond ICT industries] suffered by the EU”, will alter political attitudes towards sector priorities and policies respectively.

Many Member States are already home to large Internet and technology companies and innovative start-ups. Europe’s leading technology companies, e.g. France-based Atos and Criteo, Poland-based Allegro, Germany-based SAP, Finland’s Wolt, Sweden’s Spotify and others, benefited considerably from the last technology wave, including Internet-based intermediations, mobile communications, cloud and online payment services. Many European information technology firms innovated and adapted. Others were successful entrepreneurial tech start-ups. At the same time, many of Europe’s information technology firms were unable to scale up at the same speed as US technology firms and, to a somewhat lesser extent, successful Chinese Internet giants, which also strive for global market-leading positions.

Protectionist interpretations of technology sovereignty would add to existing tensions in international trade and investment policy, provoking retaliatory measures against Europe’s strong export industries. The current debate about how to relax EU competition rules to support European industrial champions, while at the same time tightening them through ex-ante rules and mergers and acquisitions (M&A) scrutiny to limit foreign tech giants, is considered a major provocation by the EU’s main trading partners. European politicians should abstain from picking winners and losers.

Picking politically well-connected companies would inevitably distort markets. Subsidies would have a crowding-out effect on private sector risk-taking and investment in the EU. Special taxes on digital services, aimed at foreign technology companies, are discriminatory by design. They would be largely borne by the users of digital services and unnecessarily provoke retaliatory measures (Bauer 2019).

3.3 European Responses to Internet Security Risks: Cybersecurity

The fourth C in the European debate about technology sovereignty is cybersecurity. European concerns about cybersecurity are generally about the safety of business and personal data in an increasingly global data environment. And these concerns are shared by governments, businesses and citizens across the EU. Cybersecurity threats are both big and increasing, and they are shared by each one of Europe’s allies. These threats often tend to come from certain governments with little interest in freedom and democracy, with the aim of eroding current structures of international economic policy.

With regard to commercial data, the emergence and application of new technologies, such as cloud services, the Internet of Things (IoT) and 5G, has changed the strategic paradigm for protecting European commercial interests (Lee-Makiyama 2018). Critical commercial information, e.g. on contract negotiations, customer and marketing data, product designs and R&D, are commonly uploaded to clouds today. With respect to personal data and consumer protection, policy-makers are generally concerned about data privacy and potential harm to citizens and consumers caused by cyberattacks. These concerns have led to a number of regulations at EU and Member State level in recent years, e.g. the GDPR, the NIS Directive, the Cybersecurity Act, and the proposed e-Privacy Regulation proposal. However, European policy-makers wish to go further.

In its 2020 Digital Future Strategy, the European Commission highlights the risk of cyberattacks. It is argued that “malicious cyberactivity may threaten our personal well-being or disrupt our critical infrastructures and wider security interests (European Commission 2020b, p. 1). It is further stated that “[t]o tackle this growing threat, we need to work together at every stage: setting consistent rules for companies and stronger mechanisms for proactive information-sharing; ensuring operational cooperation between Member States, and between the EU and Member States; building synergies between civilian cyber resilience and the law enforcement and defence dimensions of cybersecurity; ensuring that law enforcement and judicial authorities can work effectively by developing new tools to use against cybercriminals; and last but by no means least, it means raising the aware- ness of EU citizens on cybersecurity.” (p. 4)

In the case of consumer electronics and their rapid proliferation, policy-makers across Europe have already pushed for initiatives to improve consumer security, privacy and safety. Concerns about wider economic implications include risks from large-scale cyberattacks, e.g. concerted attacks launched from large volumes of insecure data storage applications and IoT devices. Policy-makers seek to address such risks through regulation and standardisation, e.g. the UK “secure by design” policies, Germany’s IT Security Law and the EU’s Cybersecurity Act, which (aim to) establish certification frameworks for ICT digital products, services and processes (DCMS 2018; BSI 2020; European Commission 2020).

Whether these measures help to make Europeans’ data safer may be disputed. Regulatory actions may indeed contribute to safer devices and, perhaps more importantly, a more educated public with regard to the use of modern ICT devices and software applications. Harmonisation of Member State regulations on security standards would limit the regulatory burden imposed on businesses and consumers. At the same time, data residency and localisation requirements, e.g. within the scope of a “European Cloud”, would neither increase the safety of Europeans’ data nor allow Europeans to benefit from cutting-edge technologies and business solutions offered by superior foreign suppliers.

Europe’s policy-makers need to ensure that citizens and businesses retain access and continue to benefit from new technologies and technology-based business models. At the same time, as highlighted by Lee-Makiyama (2018), cyber espionage is undetectable in most cases. Moreover, cyberattacks from government entities cannot be sanctioned under international law, so there is little potential for a UN-style solution. This situation is untenable to European policy-makers, and motivates calls for new diplomatic approaches, such as the proposal to condition market access on good government (no spying) behaviour by autocratic regimes.

Restrictions to market access might indeed serve as a workable lever to induce good government behaviour – after all, this is part of the rationale of economic diplomacy. However, such endeavours can also open the doors for new protectionist policies, and they can hurt EU allies whose support is needed in cybersecurity protection. Lessons can be drawn from the debate about the need to protect investments of strategic importance to Europe (see, e.g., Bauer and Lamprecht 2019). A sensible starting point could be the EU-US continuous dialogue on US law enforcement and national security laws during the Privacy Shield Framework annual review, and the potential prospect of a repeal of this data transfer tool should the Commission consider that US laws adversely affect EU citizens’ data protection.

Similar to investment screening policies, the actual design of an EU cybersecurity framework needs to recognise the integrity of the EU’s overarching economic policy objectives, particularly the EU’s long-standing commitment to open markets and non-discriminatory policymaking (see, e.g., European Commission DG Trade 2015). With respect to China – whose government is a concern for Europe with respect to cyberattacks – policy initiatives on cybersecurity could seize the current moment of opportunity from the EU’s negotiations of an investment agreement, committing China’s government “not to spy”, on the condition of sustained market access for Chinese trade and investment. If such a commitment were to be backed up by cooperation and review mechanisms, and restriction instruments used if other efforts fail, the chances of success would be higher.

Europe’s policy-makers should recognise the risk of policy inconsistencies, e.g. the impacts of cybersecurity regulations on the integrity of the Single Market and international rules for trade and investment. New cybersecurity regulations need to be designed on the basis of scientific evidence regarding the actual impact on the safety of personal and commercial data rather than simplistic geopolitical considerations. European data localisation requirements, a frequently proposed policy (also pushed and enforced by the governments of China, India and Russia), would neither improve data safety nor reduce the number of cyberattacks from hackers and foreign governments. Data localisation requirements would reduce Europe’s technology sovereignty by reducing citizens’ and businesses’ access to trustworthy services. European data localisation requirements would also send undesirable signals to authoritarian governments, which do not share European values with respect to fundamental human rights, by empowering them to localise data to increase their capacities to spy on their own citizens. This would also contradict the goal of the GDPR and policymakers to export EU fundamental values to non-EU countries.

[1] Due to incumbents’ established processes and management practices (Henderson and Clark 1990); incumbents’ rigidity due to accumulated organisational and technological knowledge (Christensen and Bower 1996); incumbents inability to lead several technological waves (Benner and Tushman 2002); and incumbents’ fears to cannibalise own markets.

[2] Reding (2016, p. 1-2), for example, argues that the “EU is the largest economic and trading block in the world but is at risk of losing its digital sovereignty – its capacity to influence the norms and standards of the information technology that play a crucial role in 21st century development.” She continues stating that “[s]overeignty ‘is the capacity to determine one’s own actions and norms’. It is easy to agree on this general definition. But the deep sense of sovereignty lies in our actions. We can use it to build borders and fences, thereby transforming ourselves into islands. That’s what some European politicians risk doing, when they get lost in a maze of motley national prerogatives. If you think small, you stay small, giving up all possibilities to shape globalisation.”

[3] BNP Paribas, BPCE, Crédit Agricole, Crédit Mutuel, La Banque Postale, Société Générale, Deutsche Bank, DZ BANK, Postbank (French Banking Federation 2010).

[4] The Instrument in Support for Trade Exchange (Instex) is a European special-purpose vehicle established in January 2019. Its mission is to facilitate non-USD and non-SWIFT transactions with Iran to avoid breaking US sanctions.

4. Recommendations Regarding Principles and Opportunities from Technology Sovereignty