EU and Mercosur in the Twenty-First Century: Taking Stock of the Economic and Cultural Ties

Published By: Oscar Guinea Vanika Sharma

Subjects: EU-Mercosur Project

Summary

This policy brief examines the latest developments in the EU-Mercosur economic relationship and outlines the existing non-economic relationship in order to contextualise the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement and its potential for strengthening common bonds between both regions.

Trade between the EU and Mercosur is significant, with both regions holding an important place as large markets for each other’s exports. Currently, trade between the two is dominated by trade in machinery, agriculture, and chemicals. As relevant as these traditional sectors are, their trade is also increasingly supported by trade in services, which unlike trade in traditional agricultural products such as soya, beef and sugar that are either stable or declining, is rapidly increasing.

In addition to trade, EU and Mercosur economic bonds are also supported by investments. EU member states hold a large stock of investment in the Mercosur countries while investment flows from Mercosur into the EU are also increasing. This increase has been particularly marked in high-tech sectors like R&D and computer software, emphasising again the changing economic relationship between the EU and Mercosur from traditional to advanced sectors.

These trade and investment dynamics are complemented by changes in the EU-Mercosur supply chains. Over the past ten years, the effects one region has on the competitiveness of the other have increased and will continue to do so into the future. The EU is the largest contributor to Mercosur exports, meanwhile Mercosur countries provide the biggest value-added to EU agricultural products.

A primary underlying trend found across all dimensions of the EU-Mercosur economic relationship has been the rise of China. In trade, it takes two to tango, and since 2015, it has been China, rather than the EU, that has risen to become Mercosur’s main trading partner. Over the past nine years, the amount of Chinese value-added embedded in Mercosur exports has more than tripled. Moreover, China has ramped up its investment into Mercosur countries, while also receiving increased investments from Mercosur. So, although the EU-Mercosur relationship is changing and bonds have deepened, the EU faces constant competition from China in its relationship with Mercosur.

Despite these changes, the EU and Mercosur share a long history of close non-economic relationships. Both have been at the receiving end of large migration flows from each other. This has led to the development of kindred cultures, shared languages, and strong non-economic ties. These similarities have long supported the establishment of deep economic bonds through meaningful collaborations in science and technology, ease of doing business, and provisions for working professionals through various cooperation agreements. However, with the rapidly changing nature of their commercial relationship, these cultural links might not be enough to sustain the economic relationship between the two. These ties need to be complemented by the ratification of the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement to nurture their changing relationship.

1. Introduction

The economic relation between the EU and Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay) has the potential to become a lot stronger, if the rules for trade and investment improve. For a while now, Europe’s trade with Mercosur has been taken for granted and political leaders have invested far too little time and effort to nurture it. The EU-Mercosur Association Agreement – although not yet ratified – could rectify many decades of neglect. It addresses various areas of contention such as high tariffs and the lack of regulatory alignment in several industries such as in the automotive sector. The agreement could benefit both sides – as well as firms of all sizes – and take the EU-Mercosur economic relation into the twenty-first century.

The debate around the agreement continues prior to its ratification and the goal of this policy brief is to inform this debate with facts and figures and to anchor it into the modern realities of the EU and Mercosur relationship. For years, EU and Mercosur trade and investment has been misrepresented as one based on old colonial ties and trade in commodities. Spain and Portugal are often presumed to be Mercosur’s primary trading partners, while agricultural products are seen as the most important traded goods. This is wrong. In reality, all EU member states have developed economic links and complementarities with the Mercosur countries, and these ties include all sectors that drive technological change and economic modernisation. Mercosur firms working on engineering, finance, and IT have opened factories and offices in the EU. Some of the EU major companies in chemicals, telecommunication, automotive, machinery, and banking are also the leading ones in Mercosur.

Moreover, the connections between the EU and Mercosur go beyond trade and investment. Several people in Mercosur hold an EU passport and many others are of European heritage. The two regions share similar cultures, and their legal systems and institutions are cut from the same cloth. These non-economic relationships often play a subtle yet important role in enabling stronger economic ties. Family connections, common languages, and similar institutions lower bilateral trading costs which are particularly relevant for the more than 30,000 European SMEs exporting to Mercosur.

Any debate on the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement should start from an accurate understanding of what binds the EU and Mercosur together. This policy brief offers a starting point for this debate as it describes the modern realities behind the EU and Mercosur relationship in trade and investment, as well as the non-economic bonds that connect the two regions with each other.

2. EU and Mercosur Trade

In 2019, the EU exported €62 billion worth of goods and services to Mercosur countries. For their part, Mercosur sold goods and services to the EU for a value of €47 billion. This bilateral trade made Mercosur the tenth most important destination for EU exports while the EU was the second most important market for Mercosur exports.

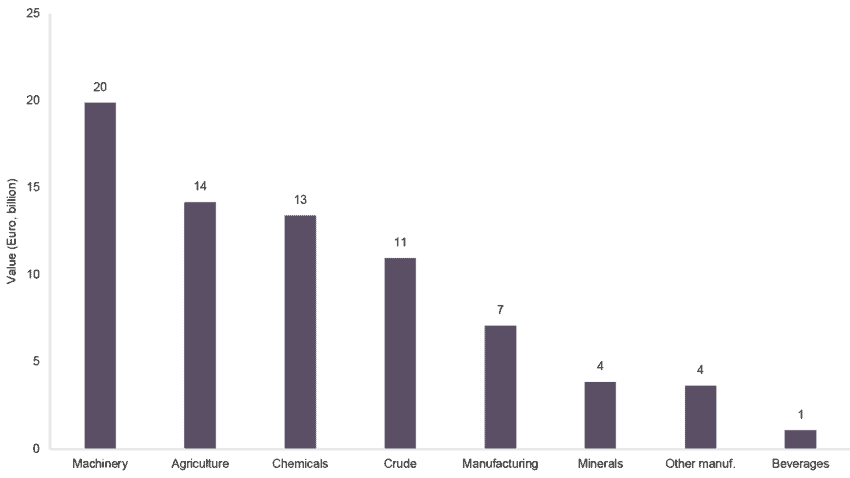

Figure 1 shows the combined trade in goods of EU exports to Mercosur and Mercosur exports to the EU broken down by economic sector in 2019. The total value of goods traded between both regions was around €77 billion, with 53% exported from the EU and 47% from Mercosur. Trade between the EU and Mercosur is dominated by machinery (25%), agriculture[1] (18%), chemicals (17%), and crude materials (14%). The composition of this trade has been relatively stable over time. However, while the exchange remains substantially driven by trade in commercial vehicles and agricultural products, these two industries have become less relevant for EU-Mercosur trade since 2007.

Figure 1: EU-Mercosur exports by economic sector (2019, billion euros)

Source: Eurostat. Authors’ Calculations.

The agricultural sector deserves special attention, not just because of the significant role that it plays in the Mercosur-EU trade, but also due to the sensitivities the sector raises for the ratification of the Association Agreement. The EU is the largest buyer of Mercosur’s agricultural exports: 18% of Mercosur’s total agricultural exports goes to the EU. Yet, trade in agricultural goods between the EU and Mercosur becomes less relevant when put into the context of the EU’s total imports. Mercosur exports in agricultural products to the EU represent just 3.5% of EU total agricultural imports once trade in agricultural goods within the EU is taken into account[2]. As a result of Mercosur’s lesser importance as a source of agricultural products for Europe, any increase in Mercosur’s agricultural exports to the EU resulting from the trade deal is likely to have a limited impact on EU’s agricultural production[3].

Trade between the EU and Mercosur is more than just trade in goods, as the commercial relationship between both regions is increasingly supported by trade in services. In 2019, the EU and Mercosur exchanged services for a value of €32 billion, with 66% exported from the EU and 34% from Mercosur. To put this figure into context, Mercosur service exports to the EU (€11 billion) were of similar value to Mercosur as the region’s total agricultural exports to the EU (€13 billion). Or take the exports of soya, beef, and sugar – three goods that occupy much of the attention in the EU debate. The combined value of Mercosur’s exports in these three goods to the EU in 2019 was lower than Mercosur exports of business services to the EU (€3 billion compared to €4.3 billion). Moreover, exports in these agricultural products have either been stable or decreased since 2012, while Mercosur exports to the EU of high-tech services experienced strong growth.

The significant amount of trade in business services and in other service sectors such as telecommunications highlights the importance of trade in high value-added activities between the two regions. It symbolises a movement away from trade in traditional sectors such as agriculture towards trade in more complex products such as engineering, research, and digital services. For instance, the exports of business services from Mercosur to the EU doubled between 2010 and 2019. Moreover, within business services, Mercosur exports of R&D services to the EU in 2019 grew by 56% from €271 million in 2010 to €424 million in 2019. For their part, EU firms exported close to €1.7 billion of information and telecommunication services to Mercosur in 2019. This bilateral trade in digital services will certainly increase in the near future as new links between the EU and Mercosur become operational (See Box 2: EllaLink). Only the announcement of the Association Agreement between the EU and Mercosur led to a 10% increase of cross-border Internet visits to e-commerce websites among the EU and Mercosur countries[4].

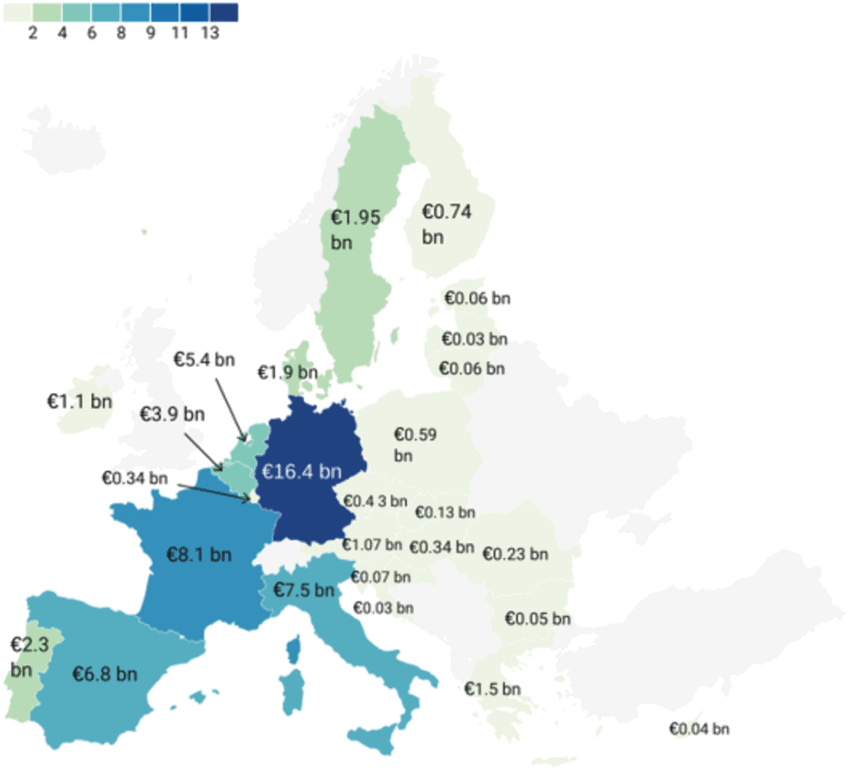

Trade between the EU and Mercosur is also more geographically diverse than what is commonly understood. Figure 2 shows that EU exports to Mercosur were led by Germany, France, Italy, and Spain – they account for 63% of the EU’s total exports to Mercosur. However, other countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Ireland, and Austria also export substantial amounts to Mercosur whilst Denmark, Portugal, and Greece are significant exporters to Mercosur on a per capita basis. For Mercosur, the majority of its exports to the EU – in goods and services – were exported from Brazil (74%), followed by Argentina (20%), Uruguay (4.5%), and Paraguay (1.5%).

Figure 2: EU exports of goods and services to Mercosur by EU member states in 2019 (Euro, billion)

Source: Eurostat. Authors’ Calculations.

Yet, despite these strong commercial ties, each region has gradually declined in relevance to one another in terms of trade. Between 2000 and 2020, EU-Mercosur trade grew at an average annual rate of 3%, which is less than the growth rate of each region’s trade with the rest of the world (8.2% for Mercosur and 3.6% for the EU). The fall in their relevance to each other has been exacerbated by the rise of China. The EU used to be the premier destination for Mercosur exports, but in 2015 China surpassed Europe to claim this position. Between 2009 and 2019, Mercosur’s exports to China increased by over €38 billion while Mercosur’s exports to the EU grew by just €0.48 billion. In spite of these changes, the EU has managed to maintain its position as the leading market for Mercosur’s agricultural and industrial exports. In 2019, EU trade in these sectors with Mercosur was €6 billion more than China’s trade with Mercosur in the same sectors. The resilience of EU-Mercosur trade is built upon a strong cross-regional integration of EU and Mercosur supply chains and substantial bilateral investments that are explained next.

[1] Agriculture refers to the Food and Live Animals specification of SITC Rev 1 trade classification.

[2] It is important to highlight that the EU is not the main buyer of some Mercosur agricultural exports such as soya or beef. Even though the EU was the second largest importer of soya beans from Mercosur after China, the difference between the share of the two regions was significant with China claiming 75% of the soya bean exports from Mercosur and the EU only 6%. Similarly for exports of beef, China took the largest share with 47% followed by the EU with 9%.

[3] Mendez-Parra, M., et al (2020). Sustainability Impact Assessment in Support of the Association Agreement Negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur. Luxembourg. Publications Office of the European Union.

[4] Latorre, M. C. (2021). El impacto económico del acuerdo Unión Europea-Mercosur en España (Doctoral dissertation, Escuela de Economía, Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica).

3. EU and Mercosur Supply Chain Integration

Trade in parts and components which are used as inputs for production, and later consumed domestically or exported abroad, is a crucial part of the EU-Mercosur trade dynamic. The contribution of one country’s domestic production to another country’s exports can be measured in the value that a trading partner adds to the other partner’s exports.

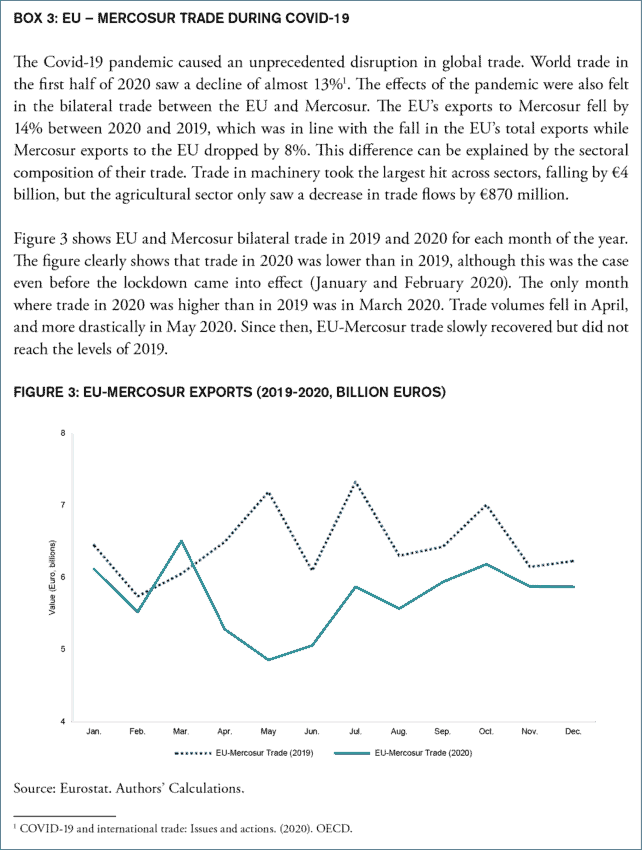

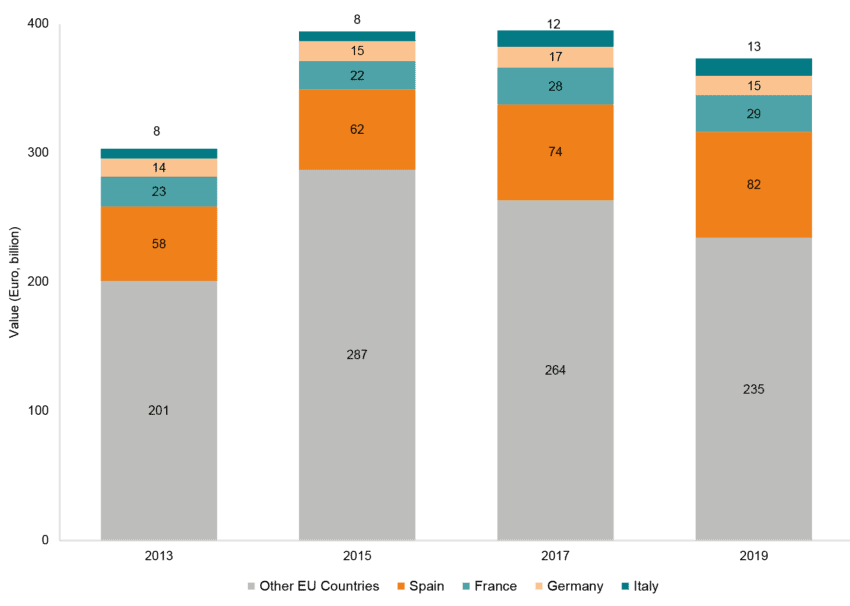

For Mercosur countries, EU businesses are the largest foreign contributors to Mercosur (Brazil and Argentina) exports. In 2015, EU value-added in Mercosur exports reached €8 billion. Over the past nine years, starting from 2007, EU value-added in Mercosur exports almost doubled (see Figure 4). To put this value in context, while 90% of the value of Mercosur exports comes from Mercosur’s own domestic production, EU value-added in Mercosur’s export represents one of every four euros contributed by non-Mercosur companies to Mercosur’s exports. At the same time, Chinese value added into Mercosur exports tripled over the same period.

Figure 4: Value-added in Mercosur Exports from other regions

Source: OECD. Authors’ Calculations.

As a result of the EU-Mercosur supply chain integration, companies on both sides of the Atlantic contribute to each other’s competitiveness. EU businesses play a part in the success of several Mercosur export industries such as chemicals, manufacturing, and automotive. The German company BASF is the largest chemical company not only in Europe but also in Brazil . BASF Europe and Brazil subsidiaries undertake a substantial amount of intra-firm trade which constitutes an example of how cross-regional EU-Mercosur supply chains are forged. Other EU companies like Fiat and Scania have built several manufacturing plants in Mercosur (see Section 4 on EU and Mercosur bilateral investment) which are supplied by Mercosur and EU companies alike as part of their supply chains.

Mercosur countries also contribute to EU exports. Mercosur producers were the largest contributors to EU agricultural exports. An example of this is soya – currently entering the EU market tariff free – which is a critical ingredient for EU’s competitiveness in agriculture as it is used by European farmers to feed their livestock. Another relevant example is Brazilian leather, which represents 10% of Italian total leather imports and is used by the Italian clothing industry to produce high-end and world-renowned products such as shoes and bags. Other EU industries, like the food sector, also benefit greatly from Mercosur agricultural imports such as oilseeds, biofuels, cereals, and coffee.

4. Profiling EU and Mercosur Investment

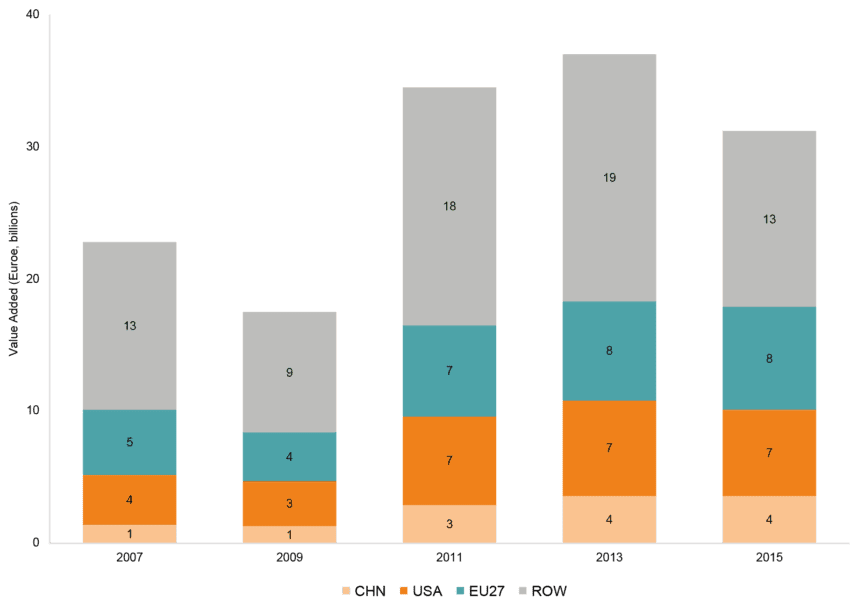

Investment flows between EU and Mercosur are another critical component of the EU-Mercosur economic relationship. In 2019 alone, EU companies invested €379 billion in Mercosur, making it the fifth largest destination of EU Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Between 2013 and 2019, the stock of EU’s FDI into Mercosur exceeded a total of €2.6 trillion. This significant amount of investment comes as a result of strong economic integration. However, it is also a consequence of Mercosur’s high import tariffs – higher than 10% on all import goods – which historically has incentivised EU businesses to jump over Mercosur high tariff wall by investing in new production capacities in Mercosur. It might sound surprising, but the stock of EU FDI in Brazil is higher than the EU FDI stock in China and approximately six times larger than the EU FDI stock in India[1]. Yet, given the increasing importance of supply chains, using import tariffs as a leverage to attract FDI is no longer as effective as before. In addition, the Mercosur economy – particularly Brazil – has not performed as well as expected which has been reflected into Europe’s falling appetite for further investments in the region (Figure 5).

As with EU trade with Mercosur, EU FDI into Mercosur is comprised by investments from numerous EU member states. Between 2013 and 2019, companies based in 22 EU member states made investments in the Mercosur countries. The top EU member states investing in Mercosur were Netherlands (€1.3 trillion), Spain (€0.5 trillion), Luxembourg (€0.4 trillion), France (€0.2 trillion), and Germany (€0.1 trillion)[2]. As can be seen in Figure 5, EU member states – other than Spain, France, Germany, and Italy – represent 60% of the €2.6 trillion that the EU invested in Mercosur between 2013 and 2019. This demonstrates that EU FDI into Mercosur involves companies from across the EU and not just from the larger economies.

Figure 5: EU investment in Mercosur (billion euros)

Source: Eurostat. Authors’ Calculations.

A deeper dive into sector-wise data shows that Mercosur’s manufacturing sector was the largest recipient of EU FDI with a stock of €546 billion euros between 2013 and 2018. These investments were made by companies like Fiat, which invested €8.8 billion in Brazil between 2006 and 2015 to build cars for the Brazilian and regional market, and Scania, which in 2017 launched an investment programme of €800 million that included product development and the modernisation of several of its Brazilian plants[3].

Other prominent sectors of EU investment in Mercosur are finance, insurance and telecommunications services which together accounted for €547 billion of EU investments in Mercosur between 2013 and 2018. These investments were carried out by companies like SAP – a German IT company – which brought its technology to Brazil and built a new R&D centre there. Extractive activities such as mining and quarrying also received significant EU investments (€403 billion), through companies like ThyssenKrupp (Germany) and ArcelorMittal (Luxembourg) that invested €6.3 billion and €5.4 billion in Brazil between 2006 and 2015[4].

At the same time, Mercosur companies have also invested significant amounts in the EU. Brazilian companies invested €5 billion between 2013 and 2020 in EU member states like the Netherlands (€ 3 billion), France (€ 0.8 billion), Germany (€ 0.5 billion), Portugal (€ 0.25 billion), and Spain (€ 0.16 billion)[5]. These investments were not just mergers and acquisitions but also greenfield investments that led to the creation of new subsidiaries from the ground up. Germany and France, for example, profited from 28 and 24 greenfield investment projects done by Brazilian businesses during this period. In terms of the sectoral breakdown, FDI from the Mercosur countries into the EU went to sectors such as agriculture and the food industry. Other sectors like crude petroleum have also received significant investments from Mercosur. In 2020, Brazilian Petrobras invested €1 billion in the relocation of its oil exploration services to the Netherlands to serve the European market[6]. Mercosur investments into the EU were also made in high-tech sectors like financial technology and engineering. Brazilian companies like Nubank – the largest digital bank outside Asia – invested €125 million in Germany to open a data centre in Berlin[7], the Argentinian computer software BSF opened its European headquarters in Barcelona with a €57 million investment[8], while long-established Mercosur companies within the EU like the Brazilian electrical company WEG expanded their presence to Austria, Germany, Portugal, and Spain[9].

However, the EU-Mercosur investment relationship has been overshadowed by the rise of China as both a big investor into Mercosur and a destination for Mercosur investment. As Mercosur and China benefit from mutual exchanges, their economies have become increasingly interconnected, and investments have naturally followed on the heels of the trade growth (See Box 4: Mercosur Public Procurement). Chinese investment in Mercosur includes infrastructure projects such as rail networks connecting Brazil’s mining heartland with the Barcarena port in the State of Pará in Brazil to facilitate the exports of iron and other natural resources[10]. Meanwhile, Brazilian investment in China has also been on the rise: outside of the Americas, China is the only country to receive more than €1 billion in investment between 2015 and 2020 from Brazil[11]. This includes companies like Embraer, a Brazilian plane manufacturing company, which is exploring an expansion into the Chinese market to meet the rising regional demand[12].

[1] Orth, C. F., Santos, C. d., Celeste, I. I., Melo, R. G., & Gusman, T. P. (2017). Bilateral Investments Map: Brazil – European Union. APEX-Brasil.

[2] The large amounts of investment coming from the Netherlands and Luxembourg could be partly explained by the role of these two countries as investment platforms.

[3] Scania celebrates 60 years in Brazil. (2017, April 26). Retrieved from Scania: https://www.scania.com/group/en/home/newsroom/news/2017/scania-celebrates-60-years-in-brazil.html

[4] Orth, C. F., Santos, C. d., Celeste, I. I., Melo, R. G., & Gusman, T. P. (2017). Bilateral Investments Map: Brazil – European Union. APEX-Brasil.

[5] Orbis Cross Border Investment. Retrieved from Bureau Van Dijk: https://www.bvdinfo.com/en-gb/our-products/data/economic-and-ma/orbis-crossborder-investment

[6] Orbis Crossborder Investments. ‘Petrobras to relocate oil exploration services office to Rotterdam, Netherlands’.

[7] Olá, Berlim: Nubank abre seu primeiro escritório internacional. (2021, August 2). Retrieved from Nubank: https://blog.nubank.com.br/nubank-escritorio-berlim/

[8] Orbis Crossborder Investments. ‘BSF opens a regional headquarters in Barcelona, Spain’.

[9] WEG Operations. Retrieved from WEG: https://www.weg.net/institutional/US/en/weg-operations

[10] United Nations ECLAC. (2020). La Inversión Extranjera Directa en América Latina y el Caribe 2020

[11] Wavteq based on fDI Markets

[12] Obe, M. (2021). Brazil’s jet maker Embraer eyes home turf of China’s COMAC . Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/Interview/Brazil-s-jet-maker-Embraer-eyes-home-turf-of-China-s-COMAC

5. EU and Mercosur Integration: More than Trade and Investment

The bonds that connect the EU and Mercosur span beyond economics. Historically, the Mercosur countries have received large flows of European migration – not just Spaniards, Italians and Portuguese but thousands of Germans, Poles, and other European nationalities fleeing Europe because of war, persecution, and bleak economic prospects. Overall, it is estimated that between 9 and 13 million Europeans moved to Latin America between 1870 and 1950[1]. As a result of this historical migration, many citizens in Mercosur have European ancestry, family links, or an EU passport. When Spain passed a law allowing the relatives of those who were persecuted and fled Spain during the Spanish Civil War to apply for Spanish nationality, almost half a million Argentinians requested it, and most of them received it[2]. It is not by chance that the largest population of Italians outside Italy is in Argentina[3], with 30 million Argentines – in a population of 46 million – claiming some degree of Italian descent. Moreover, three million Brazilians speak German which is the same number of people in the country who claim to have Polish heritage[4].

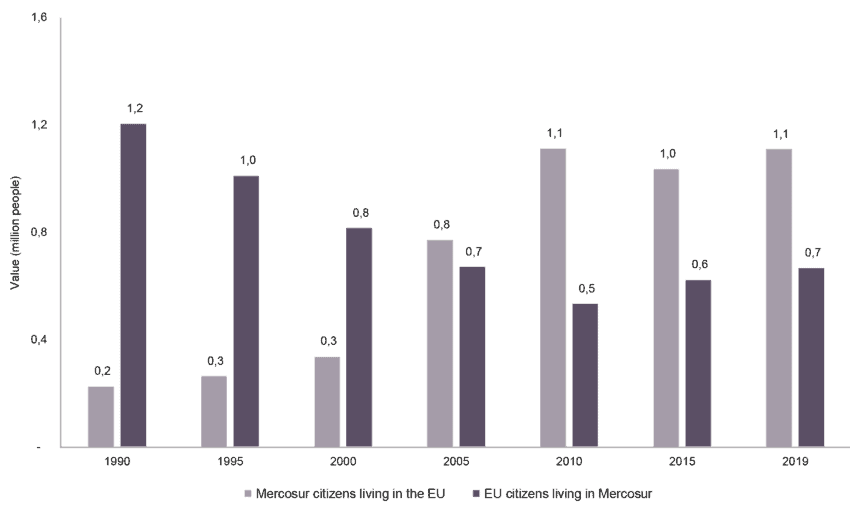

More recently, the flow of migration has been reversed and Europe has become the recipient of Latin American migration, including from the four Mercosur countries. Figure 6 below shows the number of migrants living in the opposite region between 1990 and 2019. The data shows that the number of Mercosur citizens living in the EU increased while the number of EU citizens living in Mercosur fell as compared to the levels reached in the 1990s. In the last ten years, the total number of Mercosur nationals who have migrated to the EU has stabilised at around 1 million while the number of EU migrants in Mercosur is above 650,000 people. Despite the fall in the number of European migrants in Mercosur, EU citizens still represent 20% of the total number of migrants in Mercosur. Migration from Mercosur to the EU makes for more than a quarter of all Mercosur migration and is larger than Mercosur migration to the US[5].

Figure 6: EU and Mercosur migrants living in the other region

Source: Authors’ calculation. UN Global Migration Database

The two regions also share friendly diplomatic relations which are exemplified by the Brazilian and Portugal cooperation agreement, signed in 2000. The agreement recognises most academic qualifications and allows for professionals to work and live in the other’s region for a number of years without visa requirements or residency fees. This agreement came in handy during the Great Recession (2007-2009), when many Portuguese decided to relocate to Brazil to take new employment opportunities. More recently, Brazilians have taken advantage of the agreement to move to Portugal.

The European influence in Mercosur is strong in education and culture too. There are 24 German schools in Argentina, five lycée français in Brazil, three French schools in Paraguay, and one Italian school in Uruguay. Compared to the number of international schools in India and China, these are substantial. For instance, there are only four French schools[6] and three German schools[7] in India, while China has four German[8] and five French schools[9]. Moreover, the investments that EU governments make to promote their culture in Mercosur is evident in the number of EU cultural institutions based in these countries. Danish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish cultural institutes have a physical presence in Mercosur countries and many EU cultural institutes organise regular activities in Mercosur to promote their culture. The cultural links between both regions also appear in the trade data. The EU exported €406 million in audiovisual services to Mercosur in 2019, being the fifth largest destination of this type of service for European firms.

These cultural links not only lead to business opportunities but also to cross-border exchanges in higher education and science that will be given further impetus by projects like EllaLink (See Box 2: EllaLink). Many young professionals from Mercosur move to the EU searching for the next step in their professional ladder or to enhance their academic pursuits. For instance, the IE and IESE Business schools – which rank at the top of several world rankings for business schools – have 20% and 59%[10] of their respective foreign students coming from Latin America. The research exchanges between Mercosur and the EU are intense especially in terms of collaborations on science, technology, and innovation. Since 2004, EU and Brazil have been signees to the Science and Technology cooperation agreement which focuses on priority areas such as ICT, health, and renewable energy[11]. Under the EU’s Horizon 2020 initiative, EU has funded 291 projects involving Brazil, 199 with Argentina, and 35 in Uruguay[12]. There also exists strong collaboration between several EU member states and the Mercosur countries on agricultural innovation and research to monitor and promote scientific advances of interest to agricultural businesses[13] (See Box 1: Brazil’s Green Revolution).

Underpinning these exchanges in knowledge, culture, and people, lies a common history which has led to similar legal systems and institutional structures across both regions. All EU (with the exception of Ireland) and Mercosur countries follow civil law, a system of law that took root in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, a European conflict that ignited Latin America’s independence movement and led to the Mercosur countries becoming sovereign nations. Moreover, the institutional set-up based on rule of law, separation of power, parliamentary democracy, and representation of labour and businesses broadly based on trade unions and business organisations is shared among both regions.

These legal and institutional similarities, as well as the strong economic links, have led to Mercosur countries adopting EU legislation and standards by their own accord. The Brussels Effect – as popularised by Anu Bradford[14] – can be seen in the regulation of the beef industry in Brazil, which includes a system of animal traceability that enables Brazilian’s exporters to provide the necessary sanitary and phytosanitary certification required by the EU, as well as in the data protection legislation developed in Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay out of which Argentina and Uruguay already received EU data adequacy, while the Brazilian legislation is very similar to the EU GDPR[15] (See Box 2: EllaLink).

[1] Pardo, F. (2017). Challenging the Paradoxes of Integration Policies: Latin Americans in the European City (Vol. 2). Springer.

[2] Rebossio, A (2012, January 2). Unos 446.000 descendientes de españoles han solicitado la nacionalidad. El País, Retrieve from https://elpais.com/

[3] RIM 2020. Allegati Socio-Statistici. Popolazione residente. Retrieved from: https://www.migrantes.it/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2020/10/RIM-2020_allegatistatistici.pdf

[4] Wojciech, T., / Krzysztof, S. (2009). The official report on the situation of Poles and Polonia abroad. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland.

[5] It is important to note that UN data on migration underestimates the number of EU and Mercosur nationals living in each other’s region. This is because Figure 6 counts the number of migrants while some of the EU and Mercosur citizens have lived in the other region for a long time, holding double-nationality or are registered as permanent residents. For example, Italian statistics counted 869 thousand Italians living in Argentina while the Spanish electoral register includes more than 430 thousand Spaniards registered to cast their vote in Spanish election from Argentina.

[6] Category: French international schools in India. Retrived from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:French_international_schools_in_India

[7] Category: German international schools in India. Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:German_international_schools_in_India

[8] Category: German international schools in China. Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:German_international_schools_in_China

[9] Category: French international schools in China. Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:French_international_schools_in_China

[10] Statistics of Internationalisation (2020). Ministry of Universities. Spanish Government. Figures for IESE correspond to the University of Navarra where the IESE Business school belongs.

[11] ‘Mapping of collaborative activities on Science, Technology and Innovation between Brazil and the European Union, Member States & Associated Countries’ 2020, EU delegation to Brazil?

[12]Cordis EU Research Results. (2021). Retrieved from European Commission: https://cordis.europa.eu/search?q=contenttype%3D%27project%27%20AND%20(programme%2Fcode%3D%27H2020%27)%20AND%20(%27brazil%27)&p=1&num=10&srt=Relevance:decreasing

[13] OECD (2019), Innovation, Productivity and Sustainability in Food and Agriculture: Main Findings from Country Reviews and Policy Lessons, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c9c4ec1d-en

[14] Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press, USA.

[15] European Commission. Adequacy decisions. Access on the 28 May 20201. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/international-dimension-data-protection/adequacy-decisions_en#:~:text=The%20European%20Commission%20has%20so,Uruguay%20as%20providing%20adequate%20protection.

6. Conclusion

EU and Mercosur countries enjoy long-established bonds; from trade and investment to a shared history and culture. These bonds have, over time, changed and become more complex and nuanced. For instance, one of the key features that distinguishes the EU-Mercosur relationship in the twenty-first century is that trade and investment in industrial goods and services are much larger and much more important than in agriculture. Another area that often is misrepresented is which member states are assumed to dominate EU-Mercosur trade. Instead of being restricted to traditional partners such as Spain and Portugal, the data shows that all EU countries participate in EU-Mercosur trade and investment flows.

A more recent defining feature that characterises EU-Mercosur relationship in the twenty-first century is the role of China as EU’s economic competitor in the region. Since 2015, China became Mercosur’s main trading partner and Mercosur-China trade combined was €33 billion larger than the EU-Mercosur trade in 2019. As Mercosur and China benefit from this mutual exchange, their economic integration is a reality that will continue to grow in the future. So far, the EU has had a certain advantage in terms of the rich non-economic and cultural relationship that complements the economic relationship between the two regions. However, the changing reality of business, commercial opportunities, and politics cannot be sustained by past relationships alone.

It is against this background of an ever-evolving EU and Mercosur landscape that policy-makers and the public should judge the opportunities and risks arising from the agreed EU-Mercosur Association Agreement. At the same time, the agreement also presents the space for the two to build newer and stronger bonds based not just on the economy but a common history, similar institutions, and a continuous exchange of people, knowledge, and ideas.

References

Alonso, B. S. (2007). The other Europeans: immigration into Latin America and the international labour market (1870–1930). Revista de Historia Económica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 25(3), 395-426.

Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press, USA.

Cariello, T. (2019). Chinese Investments in Brazil 2018. The Brazil-China Business Council (CEBC).

Carmo, A. S., & Bittencourt, M. V. (2011). O comércio intra-industrial entre Brasil e os países da OCDE: decomposição e análise de seus determinantes. IPEA.

European Investment Bank. (2020). EIB Activity in Latin America in 2019

EU Delegation to Brazil. (2020). Mapping of collaborative activities on Science, Technology and Innovation between Brazil and the European Union, Member States & Associated Countries.

Latorre, M. C. (2021). El impacto económico del acuerdo Unión Europea-Mercosur en España (Doctoral dissertation, Escuela de Economía, Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica).

Mendez-Parra, M., et al (2020). Sustainability Impact Assessment in Support of the Association Agreement Negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur. Luxembourg. Publications Office of the European Union.

OECD. (2019). Chapter 5. Innovation policy and the agricultural innovation system. Retrieved from Innovation, Productivity and Sustainability in Food and Agriculture: Main Findings from Country Reviews and Policy Lessons.

OECD. (2020). COVID-19 and international trade: Issues and actions.

Orth, C. F., Santos, C. d., Celeste, I. I., Melo, R. G., & Gusman, T. P. (2017). Bilateral Investments Map: Brazil – European Union. APEX-Brasil.

Pardo, F. (2017). Challenging the Paradoxes of Integration Policies: Latin Americans in the European City (Vol. 2). Springer.

Statistics of Internationalisation (2020). Ministry of Universities. Spanish Government.

United Nations ECLAC. (2020). La Inversión Extranjera Directa en América Latina y el Caribe 2020.

Wojciech, T., / Krzysztof, S. (2009). The official report on the situation of Poles and Polonia abroad. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland.