Increasing Economic Opportunity and Competitiveness in the EU: The Role of Micro-Credentials

Published By: Matthias Bauer Elena Sisto Renata Zilli

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union

Summary

As Europe experiences rapid technological advancements driven by innovations such as automation, Artificial Intelligence, and the Internet of Things, the demands on the workforce are evolving at an unprecedented pace. This shift has exposed the limitations of traditional education systems, which struggle to equip individuals with the skills needed to thrive in a dynamic job market. Micro-credentials – short, targeted learning experiences – are emerging as a powerful tool to bridge this gap, enabling a more skilled and agile workforce that can adapt to changing industry needs.

Europe’s labour market is shifting towards valuing specific skills that do not necessarily require traditional university degrees. Skills-based hiring is broadening talent pools and creating more opportunities, especially for those without formal education, women in under-represented fields, and younger generations. This change calls for a re-evaluation of candidate assessment methods and underscores the importance of Continuing Vocational Education and Training (CVET) to help workers stay competitive in an evolving job market (Section 2).

Micro-credentials offer a flexible, efficient way for individuals to acquire in-demand skills, enhancing their employability and supporting broader economic growth. These credentials are designed to be portable and stackable, allowing learners to build a portfolio of skills that can be easily recognised across borders and industries. Many large firms have already established high-standard micro-credentialing systems to retrain and upskill their workforce. This firm-driven education helps bridge the gap between academia and the private sector by aligning with market needs. While challenges such as standardisation, recognition, and alignment with global standards must be addressed, there is not necessarily a strong role for governments to play, aside from increasing awareness and ensuring transparency to support the wider adoption of micro-credentials in society (Section 3).

To maximise the benefits of micro-credentials, EU and Member State policymakers should focus on several key areas (Section 4):

- Raising Awareness of Skills-Based Hiring and Micro-Credentials: Promoting skills-first hiring practices that prioritise competencies over traditional qualifications can help broaden the EU’s talent pool. Aligning with global corporate best practices and creating industry-recognised frameworks will allow workers to continuously upskill and meet changing job demands.

- Aligning EU Micro-Credentials with Global Standards: Developing EU guidance for micro-credentials that integrates global standards and corporate best practices can enhance their portability and value. This alignment will make EU-recognised credentials more competitive and appealing in international markets.

- Supporting SMEs in Micro-Credential Adoption: Financial incentives, such as tax credits, could assist SMEs in utilising micro-credentials for workforce development. Access to shared platforms and resources, informed by global best practices, can help reduce costs and support SMEs in building a globally competitive workforce.

- Encouraging Public-Private Partnerships: Fostering collaboration among educational institutions, businesses, and government entities can support the development of accessible, affordable micro-credentials tailored to current and emerging labour market demands. Partnering with multinational corporations will further ensure these credentials align with global industry trends and incorporate best practices.

- Government-Sponsored Platforms for Micro-Credential Providers: Developing public platforms that list reputable micro-credential providers, including those recognised by multinational companies, can build trust and support wider adoption. These platforms would help promote transparency and facilitate the global recognition of EU micro-credentials, supporting workforce development.

1. Expanding Economic Opportunity with Micro-Credentials

Europe is undergoing a period of rapid technological advancement, driven by innovations such as automation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT). These emerging technologies are not only transforming industries but also reshaping markets at an unprecedented pace. While technology has always been a catalyst for change, the current era is distinguished by the speed at which these developments are taking place. This technological disruption has created a ripple effect, altering production processes and the skills required to remain competitive in the workforce. As a result, employers are increasingly struggling to find individuals with the right skills to meet the evolving demands of the market.

Traditional educational paths, though fundamental, are increasingly struggling to keep pace with these rapid technological shifts. Employers face significant challenges in attracting the right talent as changing demographics, legal constraints, early retirements, and immigration policies constrict labour supply in many European countries. The need for educational reform is clear – systems must become more flexible and adaptable to equip individuals with the skills demanded by today’s dynamic labour market.

Education is not just a means of individual development; it is a cornerstone of free, democratic societies where individuals must have the opportunity to pursue their chosen careers and lives. A high-quality, adaptive educational framework is essential to achieving this freedom of choice. Expanding access to relevant skills training will be crucial in increasing economic opportunity, allowing individuals to engage with new industries and drive innovation.

Micro-Credentials in Education and Professional Qualification

Within this context of fast-paced economic and technological transformation, micro-credentials are gaining traction as a novel approach to continuing education and professional qualification. These short, targeted learning experiences are increasingly becoming an integral part of education and qualifications systems globally, offering individuals the ability to respond swiftly to market needs. As with other supply-side oriented economic and technology policies, micro-credentials can become a significant catalyst for economic opportunity across the EU, enabling a more agile and responsive workforce that can adapt to the demands of changing job markets. By equipping individuals with relevant, in-demand skills, micro-credentials not only enhance personal career prospects but also contribute to broader competitiveness within the EU.

Unlike traditional government-centric education and qualifications systems, micro-credentials can be more effective in equipping learners with the specific skills required in today’s rapidly evolving job market. The European Commission has already underscored the importance of micro-credentials in achieving its 2030 target of 60% adult participation in annual training programmes, highlighting their critical role in ongoing skills development.[1]

Given their potential to quickly deliver relevant, market-driven skills, it is crucial that the development of micro-credential systems becomes a political priority at both the EU and national Member State levels. Our paper seeks to support this by evaluating how micro-credentials benefit both learners and employers. Additionally, we will provide policy recommendations to ensure the effective implementation and scaling of micro-credential systems, enabling them to fully realise their potential as a transformative tool for education and economic growth.

This policy brief is structured as follows: Section 2 will start with a discussion of the significance of skills-based hiring, highlighting how it is reshaping the job market by prioritising specific competencies over traditional credentials. Section 3 will delve into the concept of micro-credentials, explaining their function, benefits, and how they are being implemented in practice to meet the demands of modern industries. Finally, Section 4 will conclude and provide actionable policy recommendations to support the transition towards a skills-first, micro-credential-driven employment landscape.

[1] EU Commission (2021) Proposal for a Council Recommendation on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0770.

2. The Rising Significance of Skills-based Hiring

The evolving job market, driven by demographic shifts and technological advancements, is increasingly valuing specific skills over traditional credentials like job titles or university degrees. As skills requirements rapidly change, a shift towards a skills-first hiring approach is expanding talent pools, particularly benefiting those without degrees, women in under-represented fields, and younger generations. This approach also underscores the importance of Continuing Vocational Education and Training (CVET) to adapt to new demands, with participation varying across the EU. Emphasising skills over formal education not only broadens opportunities for workers but also helps employers better meet the challenges of a modern, dynamic workforce. As such, EU policymakers should not stand in the way of skills-first hiring practices, expand access to a broad array of vocational training, improve awareness across Member States, and foster a culture of lifelong learning to better prepare the workforce for the evolving job market.

The Evolving Job Market: The Shift Towards Skills-First Hiring

In today’s fast-changing job market, the demand for highly skilled workers is growing due to demographic shifts and technological advances. As the working population shrinks in many countries, the skills needed for success are evolving rapidly. LinkedIn data shows that the skills required for a given job have changed by about 25% since 2015, and this is expected to double by 2027.[1]

Traditional methods of evaluating candidates, such as relying on job titles or degrees, are increasingly seen as outdated. A recent survey found that 88% of hiring managers admit they may be overlooking highly skilled candidates just because they lack conventional credentials.[2] As a result, more than 45% of recruiters on LinkedIn now use skills data to fill roles, a 12% increase over the past year. In the US, for instance, one in five job postings no longer requires a degree, up from 15% in 2021.

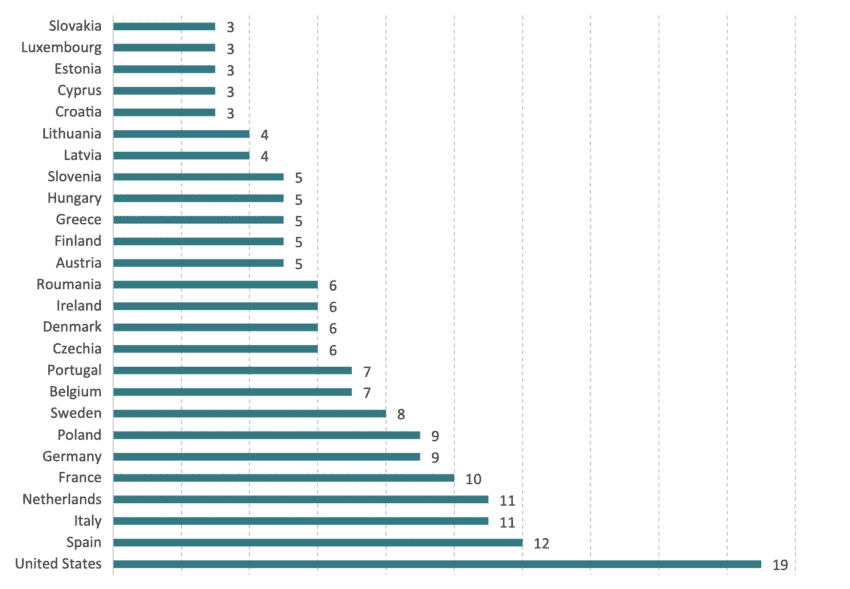

A skills-first hiring approach has the potential to dramatically expand talent pools (see Figure 1). Globally, it could increase the number of eligible workers by up to 20 times, especially benefiting those without bachelor’s degrees, women in under-represented fields, and younger generations. In the EU, the potential increase in the talent pool could be as high as 12 times in Spain, 11 times in both Italy and the Netherlands, and 10 times in France. Even in countries like Germany and Poland, the talent pool could expand by 9 times, offering substantial opportunities for both employers and job seekers.

Figure 1: Skills-first talent pool increase, talent pool growth multiplier Source: LinkedIn.

Source: LinkedIn.

Rethinking Hiring and Training in a Skills-Driven World

Despite the clear benefits, traditional hiring practices remain common, although their flaws are becoming more apparent. Research suggests that conventional measures like years of experience are not reliable indicators of a candidate’s ability to perform a job effectively.[3] Moreover, many workers lack access to higher education, limiting their job prospects. With ongoing economic changes and demographic shifts, rethinking approaches to hiring and professional qualification is becoming increasingly urgent. Declining worker populations, lower-than-expected population growth, early retirements, and reduced immigration are all contributing to a tighter labour supply in many countries.

Continuing vocational education and training (CVET), particularly employer-sponsored CVET, plays a crucial role in adapting to these changes. CVET contributes to both economic performance and personal development by enhancing career progression, maintaining competitiveness, and adapting to evolving labour market demands. However, participation in CVT courses varies significantly across the EU. For instance, in 2020, 82.8% of workers in Czechia engaged in CVT courses, while only 11.8% did so in Greece.[4] These disparities reflect different levels of commitment to lifelong learning and skills development among EU countries, influenced by economic conditions, cultural attitudes, and employer investment in workforce development.

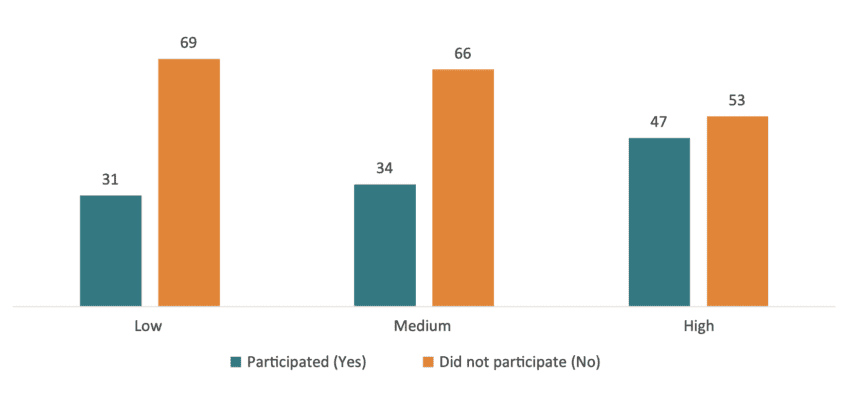

Figure 2: Participation in Job-Related Education or Training Courses by Education Level Over the Last 12 Months, 2021 Source: ESJS2, Cedefop.

Source: ESJS2, Cedefop.

Bridging the Gap: The Increasing Role of Job-related Education and Training

As shown in Figure 2, participation in job-related education or training courses is more common among people with higher levels of education. Specifically, 47% of those with a high level of education participate in such courses, compared to only 34% with a medium level of education and 31% with a low level of education. This trend can be attributed to graduates seeking additional training to acquire practical skills not fully covered in their formal education. Conversely, individuals with lower levels of education may gain practical experience directly through their studies or early career opportunities, reducing their need for additional training.

Company size also plays a significant role in access to training opportunities. Data from 2020 shows that in the EU, 88.5% of employees in large enterprises participated in CVT courses, compared to 72.3% in medium enterprises and only 50.3% in small enterprises.[5]

As concerns market penetrations, the choice of CVT providers varies across the EU. According to Eurostat’s 2020 data, private training companies are the most used providers across most EU27 countries, with 68.4% of enterprises relying on them. Public training institutions, often financed or guided by the government, are significant in countries like Estonia, Denmark, Belgium, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Finland, and Austria, reflecting strong government involvement in education and training[6]. These institutions are utilised by 12.1% of enterprises. Some enterprises also use private companies where the main activity is not training, such as equipment suppliers or parent companies; Greece, for instance, shows a relatively high usage rate of 32.1%, suggesting a specialised or industry-specific approach to training. Employers’ organisations, chambers of commerce, and trade unions as training providers show varying levels of usage. In Germany, Austria, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Belgium, employers’ organisations are involved, with usage rates between 51% and 29%. Across the EU27, 22.8% of enterprises engage with employers’ organisations and chambers of commerce, while 2.8% use trade unions. Formal education institutions are used by 9.7% of enterprises, indicating their role in complementing vocational training.

Embracing a Skills-First Future

As employers increasingly prioritise skills over degrees or job titles, there is a growing need for CVT programs that develop specific, in-demand skills. This shift could make CVT more accessible to a wider range of people, including those without higher education. A skills-first approach to CVT would also emphasise transversal skills—those that apply across various roles and industries—allowing for greater workforce mobility and better alignment with the needs of the modern job market.

By focusing on skills rather than traditional credentials, employers can tap into a broader and more diverse talent pool, while employees can enjoy greater opportunities for career advancement. This approach helps bridge the gap for under-represented groups in the workforce and values non-traditional learning paths, such as online courses, apprenticeships, and on-the-job training. Ultimately, a skills-first approach is not just a trend but a necessary adaptation to the evolving demands of the global job market.

[1] LinkedIn (2023). Skills First – Reimagining the labour market and break down barriers. Available at https://linkedin.github.io/skills-first-report/.

[2] Fuller, J. B., Raman, M., Sage-Gavin, E., & Hines, K. (2021). Hidden workers: Untapped talent. Harvard Business School Project on Managing the Future of Work and Accenture.

[3] Van Iddekinge, C. H., Arnold, J. D., Frieder, R. E., & Roth, P. L. (2019). A meta‐analysis of the criterion‐related validity of prehire work experience. Personnel Psychology, 72(4), 571-598.

[4] Eurostat (2023). Enterprises providing training by type of training and size class – % of all enterprises. Available at https://doi.org/10.2908/TRNG_CVT_01S.

[5] Eurostat (2023). Enterprises providing training by type of training and size class – % of all enterprises. Available at https://doi.org/10.2908/TRNG_CVT_01S.

[6] Eurostat (2023). Main providers used for external CVT courses by type of provider and size class – % of enterprises providing external CVT courses. Available at https://doi.org/10.2908/TRNG_CVT_30S.

3. Reinforcing Skills-based Hiring Through Micro-Credentials

The European approach to micro-credentials has evolved as a strategic response to the rapidly changing labour market and the need for flexible, targeted education options. This initiative, formalised in a 2021 EU Council recommendation, aims to create a standardised framework that ensures the quality, transparency, and cross-border recognition of micro-credentials across Europe.[1] The approach supports lifelong learning and employability by allowing learners to acquire specific skills quickly, with these credentials being stackable and portable, thereby enhancing their value in both educational and professional contexts. This effort is part of a broader vision to establish a cohesive European Education Area by 2025.[1]

Micro-credentials – small, targeted learning experiences – are designed to help individuals quickly acquire specific skills and competences that respond to societal and labour market needs, complementing traditional qualifications rather than replacing them.[2] According to the European Commission:

- Definition and Characteristics: A micro-credential is a documented record of the specific learning outcomes a learner has achieved through a short educational experience. These credentials are intended to be portable, shareable, and sometimes stackable into larger qualifications. They are validated through assessments that meet transparent, clearly defined standards and are underpinned by robust quality assurance mechanisms.

- EU Standards: To ensure trust and comparability across borders, micro-credentials should include certain mandatory elements, such as the learner’s identification, the title of the credential, the issuer’s country, learning outcomes, workload (measured in ECTS credits if possible), and the type of assessment. Optional elements may include prerequisites, grading, and stackability options.

- Design and Quality Assurance: The European approach outlines ten principles that guide the design and issuance of micro-credentials, emphasising the importance of quality assurance, transparency, relevance, valid assessment, and learner-centeredness. Quality assurance is key, involving both internal processes by the provider and external evaluations to ensure the credentials meet established standards.

- Recognition and Portability: Micro-credentials should be recognised for academic and employment purposes through standard procedures, facilitating their use across different countries and sectors. They should also be easily portable and storable in digital formats, such as digital wallets, with systems in place to ensure data interoperability and security.

- Guidance and Accessibility: Information about micro-credentials should be readily available to learners, integrated into lifelong learning guidance services, and designed to be inclusive, reaching a broad audience to support education, training, and career decisions.

Regional Focus at the Expense of Global Standards?

The European approach to micro-credentials primarily focuses on creating a standardised framework within the EU to ensure quality, transparency, and cross-border recognition of these credentials. While this focus on “European” standards aims to foster cohesion and trust across EU member states, it can be critiqued for not sufficiently considering global standards, especially those developed by private sector multinational companies that operate across different regions and markets.

Global cooperation is essential as the labour market is increasingly globalised, and skills need to be transferable across borders beyond the EU. The current approach may limit the applicability of EU-recognised micro-credentials in non-EU countries if global standards are not sufficiently integrated. This focus on regional standards could potentially create barriers for individuals and companies operating globally, where many private sector standards are already well-established and widely recognised.

However, there is an opportunity for the EU to align its approach with global standards, potentially through partnerships with international bodies or by incorporating elements from globally recognised frameworks into its own standards. This would enhance the portability and acceptance of micro-credentials on a global scale, making them more valuable for learners and employers who operate internationally.

Diverse Micro-Credential Terms May Create Barriers to Standardisation and Recognition

The definition of micro-credentials varies widely across countries. Three essential reasons explain the differences in semantics. First, it is a new sector on the foothills of its development. This means that it hasn’t reached its maturity point. Micro-credentials are certainly not a completely new feature, but they have gained momentum since the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.[3] Many traditional educational business models had to adapt to a new online setting, resulting in a proliferation of companies and online platforms targeting the new demand. The fast-paced environment increased competition among businesses, and companies started advertising their products using a specific nomenclature to position themselves in the market. Therefore, micro-credentials should be understood as an umbrella term for many others, such as nano-degrees, micro-masters, badges, licences, digital credentials, etc.[4] Ultimately, what all these short courses have in common is that they emerge because of a paradigm change in how individuals are acquiring skills for an intensive tech era.

The variety in names and types of micro-credentials does create challenges. According to some researchers, the absence of a definition is currently perceived as “the most substantial barrier to further development and uptake of micro-credentials” in the EU.[5] This is partly because the different terms still create confusion for businesses, employers, and recruiters regarding what a person is qualified to do. In addition, since micro-credentials follow different learning methodologies, there is a lack of consistency across the broad spectrum in the micro-credential market. For example, while for some short courses, the methodology is strict and follows a similar evaluation path as traditional education, for other degrees, there aren’t robust accreditation systems in place that can certify the person’s identity or the knowledge gained.

The EU acknowledges that “the lack of standards causes concerns about their value, quality, recognition, transparency, and portability.”[6] An emerging solution from a European perspective is that a micro-credential could confer a minimum of ECTS, which could be further integrated into other studies or credentials.[7] In the EU context, this proposal would be compatible with the subsidiarity principle, as Member States are fully responsible for teaching content. However, this does not preclude efforts to design recognition systems for these certifications at the EU level. One of the ways in which this goal could be achieved is with the help of technology. For example, blockchain technology in certification is another mechanism that can help raise trust and validity.[8]

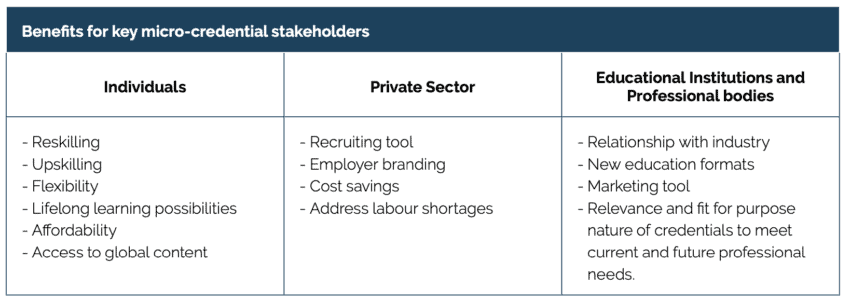

Benefits of Micro-Credentials for Multiple Stakeholders

Micro-credentials offer significant benefits to various stakeholders, even though implementing them as a new path for qualification and lifelong learning comes with challenges. These benefits are wide-ranging, addressing needs of learners, employers, educational institutions, and even policymakers. However, the perceived value and utility of these credentials can vary based on stakeholder objectives, market changes, and specific industry hiring practices.

For learners, micro-credentials provide a flexible and affordable alternative to traditional education pathways. They allow individuals to acquire specific skills that are directly relevant to their careers or personal development goals without committing to long-term, costly degree programs. This is especially useful in rapidly changing industries where upskilling or reskilling is essential to remain competitive. Additionally, micro-credentials help learners build a portfolio of verified skills to present to potential employers, improving their job prospects.

Employers benefit from micro-credentials by having a more accurate and efficient way to identify candidates with the specific skills required for a job. In fast-changing industries, traditional degrees may not always reflect the most up-to-date knowledge and skills. Micro-credentials allow employers to quickly confirm that a candidate has the necessary competencies, making the hiring process smoother. This is especially valuable in fields like IT, where skills such as coding, data analysis, and cybersecurity are in high demand and continually evolving.

For educational institutions, micro-credentials provide an opportunity to innovate and expand their offerings. Higher education systems are experiencing rapid transformation. However, the emergence of skill-based degrees is unlikely to replace traditional structures. On the one hand, university degrees function as a “proxy,” indicating the level of maturity and intellectual capability of the individual and a skillset of qualifications. For most recruiters, the university’s prestige is still a significant determinant in the hiring process. Learners taking courses by Microsoft or Stanford University also trust the brand name for quality assurance.[9] On the other hand, the education industry is experiencing an affordability crisis, as it is becoming increasingly expensive to pay increasing tuition fees in many industrialised countries. Although micro-credentials will certainly not solve this predicament, they can help educational institutions to broaden their offer to different market segments.

Policymakers and governments can also leverage micro-credentials to address workforce development challenges. By promoting micro-credentials, they can support the creation of a more agile and responsive education system that meets the demands of the modern labour market. This can help reduce skills gaps and ensure that the workforce is equipped with the competencies needed for economic growth and innovation.

Empowerment and Economic Opportunity

Micro-credentials provide many benefits for learners. Although education is often thought to be a process meant for the early years of life, the importance of life-long learning is increasingly emphasised. In his influential report for UNESCO titled “Learning: The Treasure Within,” former EU Commissioner Jacques Delors articulated the purpose of education as a means for fostering holistic human development. Delors argued that education should impart knowledge and skills and nurture individual autonomy, creativity, and the ability to coexist harmoniously with others. While this isn’t a new report, the ideas still hold true. Europe has always been at the forefront of human development, and in light of the significant transformations in the global economy, it is imperative to reassess how Europe’s future society should be constructed.

Micro-credentials serve as instruments for empowerment. By giving them control over their learning journey and professional development, it is possible for individuals to achieve both professional fulfilment and a sense of contribution to society. Unlike traditional education degrees, which often require significant time and financial commitments, micro-credentials allow learners to acquire relevant skills efficiently. For some mid-career professionals, these short, practical and up-to-date courses could fit into their daily schedules and are the most likely option for their continuing education. According to experts, micro-credentials can address the increasing need for reskilling or upskilling. The first term implies being able to keep up with the level of employability, and the latter involves improving career opportunities by extending existing skills[10]. These degrees are also a good fit for self-employed individuals or entrepreneurs who need to regularly update their skills to keep up with changing business conditions. Ultimately, any job promotes independence and allows people to shape their own lives and futures. Beyond economic advantages, micro-credentials can help people find meaningful work that meets their need for empowerment and belonging, affirming their dignity and place in society.

Bridging the Gap Between Academia and Industry

Micro-credentials, being outcomes-based, offer a strong focus on employment, making them particularly valuable for the business sector. Unlike traditional qualifications, micro-credentials clearly demonstrate the specific knowledge, skills, and competencies a person has gained. This clarity can streamline the hiring process by enabling more informed decisions, leading to better job matches. As demographic shifts reshape the workforce, micro-credentials could enable businesses meet the immediate demand for specialised talent. This targeted continuous learning approach could mitigate the impact of labour shortages in a rapidly changing business environment. However, given the heterogeneity in the micro-credentials landscape, some employers remain sceptical of their effectiveness. While most employers recognise that a master’s degree indicates a higher level of preparation than a bachelor’s degree, it is harder to determine whether, for example, a Coursera Specialization provides more or better preparation than an EdX Professional Certificate.[11]

Many large firms have developed and established high-standards micro-credentialing systems to retrain and upskill their labour force. For example, with VWeLab Volkswagen has established education and qualification tools providing micro-credentials in technical fields such as 3D printing and physical computing. In addition to tracking technical skills, the tools document the development of essential skills like creativity and communication. FabFolio integrates seamlessly with popular Learning Management Systems like Canvas, Google Classroom, and Blackboard, and supports single-sign-on systems like ClassLink, making it easy for users to engage with the app.[12] IBM offers badges to both its employees and the public through a partnership with Coursera. IBM has also partnered with North Western University, allowing these badges to count towards professional master’s degree programs. Similarly, EY’s badging system lets staff earn badges in areas like data visualisation, AI, data transformation, and information strategy.[13] CISCO’s Networking Academy provides badges as part of its IT certification programs.[14] Likewise, Deloitte offers a range of micro-credentials through a B2B marketplace called ‘Learning Academy, which provides upskilling across five key business sectors: business governance and risk, digital transformation, finance and accounting, leadership and management, tax and regulation.[15] Additionally, Amazon Web Services (AWS) offers data-specific skill training through its program.[16] This company-driven education helps bridge the gap between academia and the private sector by creating programs that meet market needs. However, this can develop inequalities, as larger companies are usually the only ones able to afford these training programs, putting small and medium-sized enterprises and their employees at a disadvantage.

Table 1: Benefits for key micro-credential stakeholders Source: ECIPE compilation.

Source: ECIPE compilation.

Micro-credentials are an effective way for individuals to demonstrate expertise in particular skills. They also provide a clear path for organisations to adopt skills-based hiring practices, which could benefit industries or sectors requiring specific skills. According to a LinkedIn study,[17], the impact of a skills-first approach could increase the talent pool in Education, Consumer Services, Retail and Administrative and Support Services. This is partly attributed to the fact that many workers do not necessarily need a bachelor’s degree for many of these industries. Well-designed micro-credentials can be used as part of targeted measures to support inclusion and training for a wide range of learners, which includes disadvantaged and vulnerable groups, minorities, etc. From a gender equality perspective, research indicates that more women are encouraged to apply if they have the right skills.[18]

Another challenge is that micro-credentials are mostly used in informal sectors. In highly regulated industries like healthcare, where many jobs require licensing, micro-credentials could still play a role in continuing education. Achieving this will require closer collaboration between government, associations, and educational institutions. The same applies to firms across industries, where research shows that a skill-first approach could significantly increase the pool of potential candidates, helping to address labour shortages.[19] If designed well, micro-credentials could benefit both high-skilled and lower-skilled sectors alike.

[1] See, e.g., NESET (2020). Towards a European approach to micro-credentials: a study of practices and commonalities in offering micro-credentials in European higher education. Available at https://nesetweb.eu/en/resources/library/towards-a-european-approach-to-micro-credentials-a-study-of-practices-and-commonalities-in-offering-micro-credentials-in-european-higher-education/.

[2] European Commission (2021). A European Approach to Micro-Credentials. Available at https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-01/micro-credentials%20brochure%20updated.pdf.

[3] Brown, M., Nic Giolla Mhichíl , M. ., Beirne, E., & Mac Lochlainn , C. (2021). The Global Micro-credential Landscape: Charting a New Credential Ecology for Lifelong Learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 228–254. Available at https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.525.

[4] UNESCO. (2018). Digital credentialing: Implications for the recognition of learning across borders. UNESCO Education Sector. Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264428.

[5] Shapiro, H. (2020). Background paper for the first meeting of the Consultation Group on Micro-credentials. Available at https://www.heilbronn.dhbw.de/fileadmin/downloads/news/ab_2014/Background_paper_on_Microcredentials.pdf.

[6] EU Commission (2021) Proposal for a Council Recommendation on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0770.

[7] Brown, M., Nic Giolla Mhichíl , M. ., Beirne, E., & Mac Lochlainn , C. (2021). The Global Micro-credential Landscape: Charting a New Credential Ecology for Lifelong Learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 228–254. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.525.

[8] Resei, C., Friedl, C., Staubitz, T. (2019) Micro-credentials in EU and Global. Corporate edupreneurship. Available at: https://openhpi-public.s3.openhpicloud.de/pages/research/27kLG703NBaxDgjuaNjOWe/Corship-R1.1c_micro-credentials.pdf.

[9] Resei, C., Friedl, C., Staubitz, T. (2019) Micro-credentials in EU and Global. Corporate edupreneurship. Available at: https://openhpi-public.s3.openhpicloud.de/pages/research/27kLG703NBaxDgjuaNjOWe/Corship-R1.1c_micro-credentials.pdf.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Pickard, cited in Brown et. Al (2021). The Global Micro-credential Landscape: Charting a New Credential Ecology for Lifelong Learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 228–254. Available at https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.525.

[12] Volkswagen (2024). A web-based app that empowers students to curate a personalized digital portfolio as they document and develop key skills with micro-credentials. Available at https://www.vwelab.org/fabfolio.

[13] Brown, M., Nic Giolla Mhichíl , M. ., Beirne, E., & Mac Lochlainn , C. (2021). The Global Micro-credential Landscape: Charting a New Credential Ecology for Lifelong Learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 228–254. Available at https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.525.

[14] See: https://www.cisco.com/site/us/en/learn/training-certifications/certifications/index.html.

[15] See: https://www2.deloitte.com/in/en/pages/about-deloitte/solutions/deloitte-learning-academy.html.

[16] See: https://findyourfuturenl.ca/programs/aws-certification/.

[17] LinkedIn. (2023). Skills First – Reimagining the labour market and break down barriers. Available at https://linkedin.github.io/skills-first-report/.

[18] See, e.g., HBR (2014). Why Women Don’t Apply for Jobs Unless They’re 100% Qualified. Available at https://hbr.org/2014/08/why-women-dont-apply-for-jobs-unless-theyre-100-qualified.

[19] LinkedIn. (2023). Skills First – Reimagining the labour market and break down barriers. Available at https://linkedin.github.io/skills-first-report/.

4. Policy Recommendations for Boosting Economic Opportunity through Micro-Credentials

Micro-credentials hold significant potential for enhancing economic opportunities across the EU by creating a more agile and responsive workforce. As industries rapidly transform due to technological advancements, the demand for new skills is outpacing the ability of traditional government-centric educational systems to meet these needs. Micro-credentials offer a flexible solution by allowing individuals to quickly acquire and demonstrate specific competencies required in the workforce, thus supporting both personal career growth and broader economic development.

However, to maximise the benefits of micro-credentials, the EU and national policymakers must avoid a narrow focus on purely European standards. The evolving global landscape for micro-credentials, particularly those developed by multinational companies, should be considered. These companies often lead in setting industry standards and disseminating technology-related skillsets that are globally recognised and valued. By aligning EU standards and guidelines with these global benchmarks, the portability and recognition of micro-credentials can be enhanced, making them more useful for individuals and employers operating in an international context.

Moreover, the development and implementation of micro-credentials should be inclusive, extending benefits to small and medium-sized enterprises. While large corporations often have the resources to create bespoke micro-credentialing systems, SMEs may struggle to keep pace. Policy initiatives could include support mechanisms such as tax incentives or shared platforms that allow SMEs to access high-quality micro-credentialing resources, thus levelling the playing field.

Practical Policy Recommendations:

- Increase Awareness of Skills-Based Hiring Practices Across the EU: Encourage the adoption of skills-first hiring practices that prioritise specific competencies over traditional qualifications. This shift can be further strengthened by integrating global development insights and corporate best practices, particularly those of large multinational corporations. Establishing industry-driven frameworks that validate skills gained through micro-credentials, online courses, apprenticeships, and work experience will allow the EU to remain competitive on the global stage. By recognising the importance of these practices, policymakers can broaden the talent pool in the EU and ensure that workers from all backgrounds, including those in SMEs, have the opportunity to continuously upskill and adapt to evolving job requirements.

- Align EU Micro-Credentials with Global Developments and Corporate Best Practices: Developing common EU guidance for micro-credentials should incorporate elements from globally recognised standards and corporate best practices, particularly those established by multinational enterprises. These enterprises, often pioneers in skills-based hiring, can provide a blueprint for aligning micro-credentials with the needs of the global workforce. By doing so, the portability and acceptance of EU-recognised micro-credentials will be enhanced in the global market, making them more valuable for learners and employers who operate internationally. This alignment ensures that the EU remains competitive and its workforce is prepared for both local and international job markets.

- Support SMEs in Adopting Micro-Credentials: Provide financial incentives, such as tax credits, to help SMEs integrate micro-credentials into their workforce development strategies. SMEs, which are often key players in both local and global economies, often lack the resources to independently adopt new systems. By incorporating corporate best practices and global standards into shared information platforms or consortia, SMEs and individual entrepreneurs can access high-quality micro-credentialing resources at a reduced cost. This approach not only simplifies adoption but also ensures that SME workers are equipped with globally relevant skills, enabling them to compete in international markets.

- Foster Public-Private Partnerships for Micro-Credential Development: Encourage collaboration between educational institutions, private sector companies, and government bodies to design and deliver accessible, affordable micro-credentials that address current and future labour market needs. By partnering with multinational corporations and global industries, these alliances ensure that micro-credentials remain relevant, aligning with EU and international corporate best practices. Collaborating with private sector companies enables academic institutions to continually update and refine their curricula, reflecting the latest global industry trends and technological advancements. This integration fosters practical, real-world skills in graduates, enhancing employability and supporting the institution’s global standing, while making these credentials readily attainable for diverse learners.

- Implement Government-Sponsored Platforms for Micro-Credential Providers: To enhance trust and promote the widespread adoption of accessible micro-credentials, the EU could develop public platforms that list reputable providers. These platforms should also provide insights into whether micro-credentials are recognised by reputable multinational companies and aligned with global corporate best practices. Such transparency ensures that individuals and employers are able to easily access reliable information about the quality, reliability, and industry acceptance of various offerings. By making these platforms accessible, the EU can facilitate the global relevance and recognition of micro-credentials, thereby bolstering economic opportunity and driving workforce development across borders.