Shared Liability: The European Parliament’s Misstep in Fighting Financial Fraud

Published By: Matthias Bauer Andrea Dugo Dyuti Pandya

Subjects: European Union Services

Summary

The rise in financial fraud has prompted regulatory proposals under the Payment Services Regulation in the form of a shared liability model provisioned under Article 59. The potential proposal by the European Parliament could now extend liability beyond Payment Service Providers to Electronic Communications Service Providers and online platforms. While the intent to address fraud is commendable, this model misallocates responsibilities by requiring non-financial entities to oversee fraudulent activities, despite their lack of visibility and technical control over financial transactions. Extending liability to non-financial entities risks undermining consumer vigilance and diluting payment services providers’ efforts to maintain fraud awareness. A shared liability regime covering non-financial entities would also disproportionately burden smaller “digital” firms, leading to legal uncertainties, costly legal disputes, and market exits. This would not only drive market concentration and reduce competition in digital services but also undermine EU and Member State efforts to support Europe’s lagging digital start-ups and scale-ups. The resulting harm to innovation and entrepreneurship would be a significant setback to the EU’s broader digital ambitions.

1. Introduction

The rise in financial fraud within the EU’s digital payment landscape has led the European Commission to propose stronger consumer protection through the Payment Services Regulation (PSR) and an updated Payment Services Directive (PSD3). A key proposed provision would require Payment Service Providers (PSPs) to compensate users impacted by fraud. The obligation for PSPs to compensate customers is controversial in itself as compulsory reimbursement could significantly increase costs associated with “first party fraud,” where fraudsters pose as users or consumers.[1]

The European Parliament has further proposed a “shared liability model” under the PSR’s Article 59, expanding PSP liability to include Electronic Communications Service Providers (ECSPs) and online platforms. This broad definition encompasses online platforms, e-commerce businesses, telecoms, social media firms, and more.[2] Article 59 introduces uncertainty by exposing ECSPs and online platforms to financial liability, despite their lack of control over financial transactions. The proposal raises concerns about proportionality, compliance costs, and legal ambiguities, while potentially reducing consumer caution and PSP fraud prevention efforts.[3]

The revisions to Article 59 is a significant departure from the original European Commission’s Impact Assessment. The Impact Assessment Report for PSD2 and PSR recommends targeted strategies that place liability on PSPs.[4] Crucially, it avoided extending liability to ECSPs or online platforms, recognising their limited role in overseeing and managing transaction-based fraud. Considering these limitations, the UK and Singapore have recently adopted frameworks that focus responsibility exclusively on financial institutions and, in Singapore’s case, telco providers.

This ECIPE policy brief examines the European Parliament’s expanded liability model under Article 59 of the proposed PSR, highlighting its risks and advocating for targeted, sector-specific fraud prevention. Section 2 reviews the amendments to Article 59, Section 3 explores operational and legal challenges in fraud detection and removal, and Section 4 concludes with policy recommendations.

[1] See, e.g., Meyers (2024). Is the EU taking the right approach to APP fraud? Available at https://www.academia.edu/125484010/Is_the_EU_taking_the_right_approach_to_APP_fraud.

[2] A&O Shearman. (September 30, 2024). Combatting payment account fraud – latest regulatory developments from the European Union. Available at: https://www.aoshearman.com/en/insights/ao-shearman-on-fintech-and-digital-assets/combatting-payment-account-fraud-latest-regulatory-developments-in-the-european-union.

[3] A&O Shearman. (September 30, 2024). (see footnote: 2).

[4] European Commission (2023). Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the Documents Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on payment services in the internal market and amending Regulation (EU) No 1093/2010 and Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of The Council on Payment Services and Electronic Money Services in the Internal Market amending Directive 98/26/EC and Repealing Directives 2015/2366/EU and 2009/110/EC {COM(2023) 366 final} – {COM(2023) 367 final} – {SEC(2023) 256 final} – {SWD(2023) 232 final}.

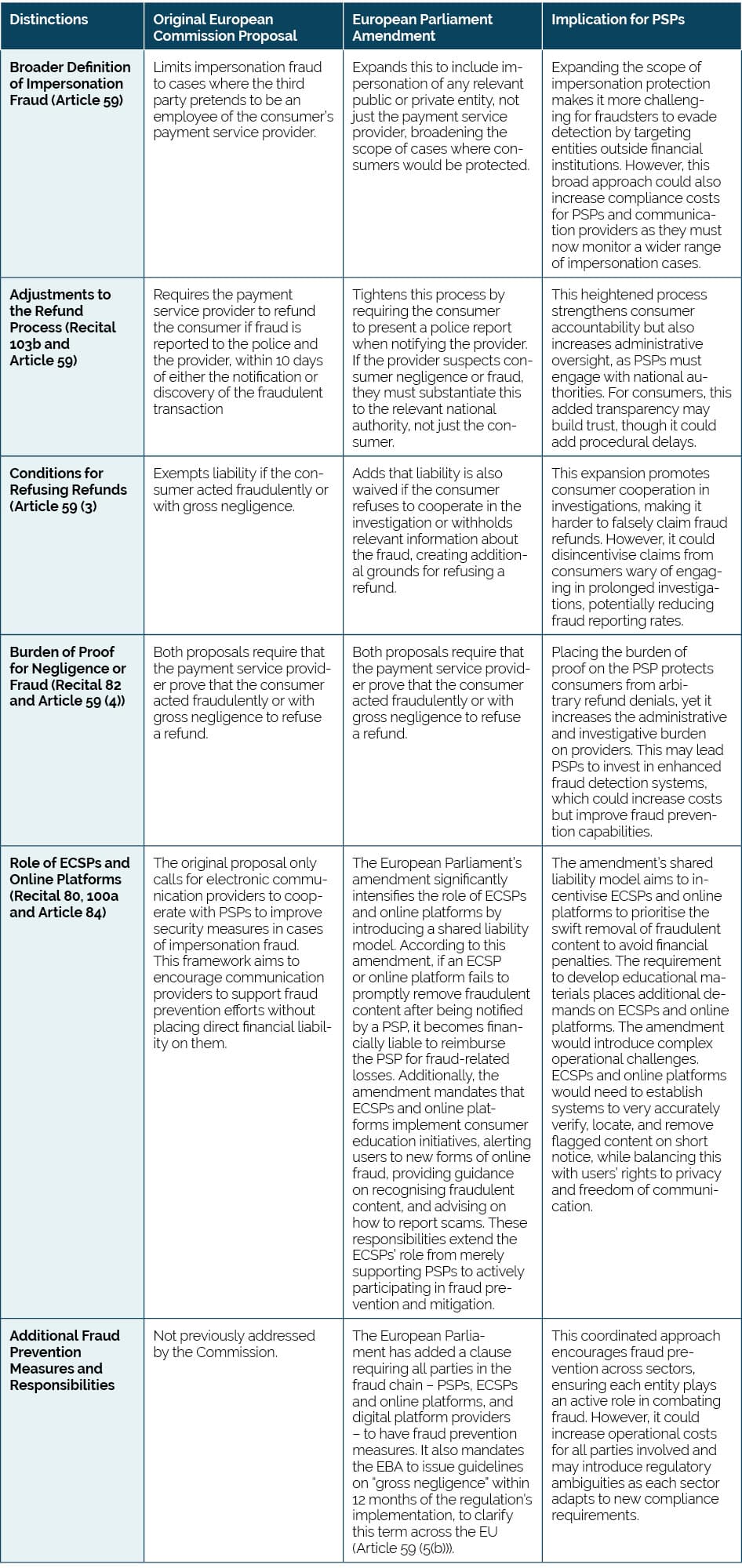

2. The European Parliament’s Amendments to Article 59 of the Proposed PSR

The European Commission’s original proposal for Article 59, prior to the amendments introduced by the European Parliament, aimed to clarify PSP liability in cases of impersonation fraud to enhance consumer protection.[1] This focused on PSPs’ responsibilities in refunding fraudulent financial transaction losses, given that PSPs oversee and control these transactions. The proposed amendment significantly broadens this scope by introducing shared liability across PSPs, ECSPs and online platforms.[2] The amendment proposes that ECSPs and platforms be financially liable if they fail to remove fraudulent content after notification from a PSP. This shifts responsibility to sectors outside the payment processing industry (see Table 1).

By contrast, the UK and Singapore have recently adopted frameworks that place the burden of responsibility for financial fraud primarily on financial institutions and telecommunications providers (in the case of Singapore), without extending formal liability to content providers or online platforms.

- In the UK, the shared liability framework focuses on Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud, requiring banks to reimburse victims up to a cap, provided that certain conditions are met and that the customer has not acted negligently.[3] Payment services providers must now enhance fraud detection, customer warnings, and systems to handle claims under the “consumer standard of caution”. This includes training staff on evaluating claims, especially in recognising vulnerabilities and mitigating fraud risk. While online platforms are not directly liable under this regime, initiatives like the Online Fraud Charter[4] encourage voluntary measures by tech companies to tackle fraud on their platforms.

- In Singapore, the proposed Shared Responsibility Framework (SRF) covers financial institutions and telecommunications providers, particularly regarding phishing scams. Online platforms are not included in the SRF, although the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) recognise the role of these platforms in facilitating some types of scams. The SRF assigns clearly defined duties to financial institutions and telcos, such as deploying scam filters and ensuring the secure delivery of SMS communications.[5]

The European Parliament’s extended liability model reflects underlying political expectations to boost consumer trust, harmonise fraud liability, and strengthen the Single Market. However, it simultaneously introduces operational and legal complexities that could misallocate responsibility and overburden non-financial entities, especially because ECSPs and online platforms do not have the same visibility and tools of financial institutions of the fraud ecosystem.

Moreover, the liability framework proposed by the European Parliament would grant discretion to PSPs, potentially resulting in an arbitrary approach when requesting ECSPs and online platforms to take action. This occurs without a clear determination of the validity of a customer’s claim, creating uncertainty regarding when to remove content or issue compensation. Table 1 contrasts the Commission’s original proposal with the Parliament’s amendment, highlighting these challenges.

Banks and PSPs support shared liability, arguing it may create a robust anti-fraud ecosystem and calling for cross-sector collaboration, data-sharing, and uniform standards.[6] ECSPs and platforms, however, contend that their role is limited by privacy regulations, technical constraints, and their intermediary status, advocating for a balanced approach based on influence and control.[7]

Table 1: Key distinctions between the Commission’s proposal and the Parliament’s amendment Source: ECIPE compilation.

Source: ECIPE compilation.

[1] For example, the evaluation report underlying the proposed PSR “concludes that PSD2 has had varying degrees of success in meeting its objectives. One area of positive impact has been that of fraud prevention, via the introduction of Strong Customer Authentication (SCA); although more challenging to implement than anticipated, SCA has already had a significant impact in reducing fraud. PSD2 has also been particularly effective with regard to its goal of increasing the efficiency, transparency and choice of payment instruments for payment service users. However, there are limits to PSD2’s effectiveness in achieving a level playing field, most notably given the persisting imbalance between bank and non-bank Payment Service Providers (PSPs) ensuing from the lack of direct access by the latter to certain key payment systems.” See Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament And Of The Council On Payment Services In the Internal Market and Amending Regulation (EU) No 1093/2010. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52023PC0367.

[2] According to recital 81a, introduced by the European Parliament, “[o]nline platforms can also contribute to increasing instances of fraud. Therefore, and without prejudice to their obligations under Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council[26] (Digital Services Act), they should be held liable where fraud has arisen as a direct result of fraudsters using their platform to defraud consumers, if they were informed about fraudulent content on their platform that and did not remove it.”

[3] See, e.g., PSR (2024). Groundbreaking new protections for victims of APP scams start today. Available at https://www.psr.org.uk/news-and-updates/latest-news/news/groundbreaking-new-protections-for-victims-of-app-scams-start-today/.

[4] The Online Fraud Charter is a voluntary commitment by UK-based tech firms to implement measures to tackle online fraud and money laundering on their platforms. It establishes a framework of actions that firms should adopt to protect users and reduce criminal exploitation of digital services. The Charter is available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65688713cc1ec5000d8eef96/Online_Fraud_Charter_2023.pdf.

[5] See, e.g., MAS (2024). MAS and IMDA Announce Implementation of Shared Responsibility Framework from 16 December 2024. Available at https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2024/mas-and-imda-announce-implementation-of-shared-responsibility-framework-from-16-december-2024. Also see MAS and INFOCOMM (2023). Consultation Paper on Proposed Shared Responsibility Framework. Available at https://www.mas.gov.sg/-/media/mas-media-library/publications/consultations/pd/2023/srf/consultation-paper-on-proposed-shared-responsibility-framework.pdf.

[6] European Competitive Telecommunications Association (ECTA), European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association (ETNO) and Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA). (2024, April 23). ECTA, ETNO & GSMA Joint Statement on the European Parliament proposals to payment services regulation after the plenary vote. https://connecteurope.org/insights/position-papers/ecta-etno-gsma-joint-statement-european-parliament-proposals-payment. European Banking Federation. (2024, September). Report of the ERPB Working Group on fraud related to retail payments. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/groups/erpb/shared/pdf/21st-ERPB-meeting/Report_from_the_ERPB_Working_Group_on_fraud_prevention.pdf.

[7] Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA). (2024, June 17). Joint-industry letter for effective and efficient fraud prevention in Europe. https://ccianet.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Joint-industry-letter-for-effective-and-efficient-fraud-prevention-in-Europe.pdf.

3. The Enormous Complexities in Addressing Fraudulent Content Removal

The European Parliament’s shared liability proposal risks significant unintended consequences by diluting accountability across sectors. It creates a moral hazard, as financial institutions may reduce investments in fraud prevention tools, relying instead on shifting liability to intermediaries, while consumers may become complacent, assuming broad protection regardless of vigilance. This approach also weakens anti-fraud awareness campaigns, as shared liability diminishes consumers’ sense of personal responsibility. Furthermore, smaller ECSPs face significant compliance burdens, discouraging innovation and forcing them to prioritise regulatory adherence over developing new services, stifling competition and reducing market diversity.

The European Parliament’s proposal to extend liability to ECSPs and online platforms represents a major shift in the regulatory framework for fraud prevention. This misalignment raises serious questions about feasibility, efficiency, and the unintended consequences for competition and innovation within the communications sector. The European Commission’s 2023 Impact Assessment for PSD2 and PSR highlighted the need for targeted, sector-specific solutions to address fraud risks effectively, focusing on financial institutions and PSPs as the primary actors capable of managing transaction-based fraud. The assessment did not advocate for extending liability to ECSPs and online platforms, recognising the operational and legal challenges such a shift would entail. It underscored the importance of aligning regulatory obligations with the roles and capabilities of each sector, warning that disproportionate burdens on non-financial actors could lead to fragmented enforcement, reduced efficiency, and diminished trust among stakeholders.

3.1. Evolving Fraud Challenges in Payment Systems: Risks and Responsibilities

Financial fraud indeed remains a challenge within the EU, with financial losses reaching EUR 4.3 billion in 2022 and EUR 2 billion in the first half of 2023.[1] Banks, telecom companies, and online platforms already have strong incentives to protect users and comply with extensive regulatory commitments requiring action against fraud (see discussion of digital policies below).

Importantly, PSPs have already developed advanced tools, such as Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) under PSD2, to combat fraud, particularly for remote payments. Moreover, to combat scams and fraud, a broad spectrum of initiatives and collaborations has emerged, leveraging technology, partnerships, and consumer education. Examples include the Tech Against Scams coalition[2] and the Global Signal Exchange,[3] which enable knowledge-sharing and real-time insights; further tools to extend security protection like Google’s Cross-Account Protection and Vodafone’s Scam Signal API, designed to detect and block scams in real-time; and partnerships such as Stop Scams UK and Europol’s EC3, which unite industries, governments, and law enforcement agencies.[4] Educational efforts, such as Google’s Scam Spotter and the UK’s Take Five campaign, complement industry-driven solutions like IBM Trusteer, Visa’s Advanced Authorisation, and Apple’s App Store Fraud Prevention. Together, these initiatives demonstrate a coordinated and evolving global response to safeguard users against emerging threats.[5]

Shifting liability for APP fraud risks undermining trust and cooperation among stakeholders by discouraging shared responsibility and proactive prevention. Like product liability, where manufacturers ensure safety but are not liable for unreasonable consumer behaviour, imposing blanket liability on ECSPs and online platforms could reduce vigilance, and weaken PSPs’ fraud prevention efforts.[6] Shared liability may also incentivise banks to offload responsibility onto intermediaries by overwhelming them with requests (“moral hazard”), eroding accountability and leading to inefficiencies and a fragmented approach to fraud prevention.

Moreover, considering consumers, extended shared liability risks undermining fraud awareness and educational programmes by encouraging users to be less vigilant, “trusting” that liability rests elsewhere in the value chain. This reduced caution may even create a “honeypot” effect, attracting even more fraud attempts and exacerbating existing challenges.[7]

3.2. Operational and Technical Challenges

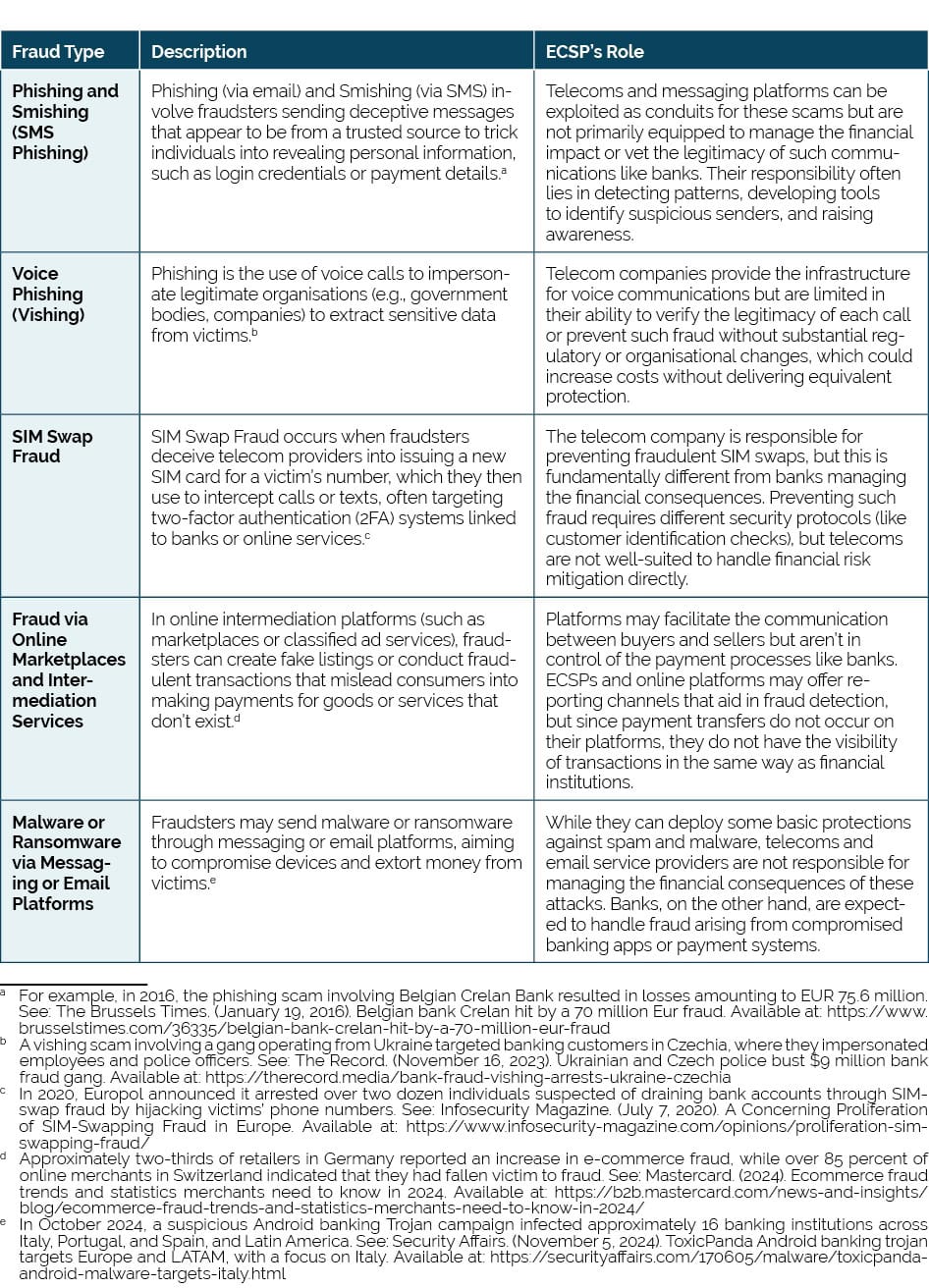

Fraudulent activities are increasingly sophisticated and adaptive, often exploiting communication channels in ways that are difficult to detect without specialised fraud prevention tools, expertise, and dedicated personnel.[8] In contrast to PSPs, ECSPs and online platforms face different types of fraud risks, such as phishing, smishing, and SIM swap fraud. These fraud tactics exploit communication channels but do not involve direct financial transactions. While ECSPs and platforms can play a supporting role by detecting patterns of fraudulent behaviour, they lack the specialised systems and capabilities required to manage fraud effectively, as they do not oversee, facilitate, or control financial transactions.

The examples outlined in Table 2 highlight that for SMEs and new entrants outside payment services, such obligations create significant operational and legal barriers. While larger ECSPs can allocate significant resources to compliance infrastructure and better manage unforeseeable legal risks, smaller firms often lack the capacity to do so. This disparity not only undermines competition and market churn but also conflicts with the foundational goals of a single European market, which aims to ensure equal opportunities and a level playing field for all market participants, regardless of size.

Despite efforts to monitor and remove suspicious content, complying fully with proposed liability obligations is challenging due to the volume and variability of fraud tactics. For ECSPs and smaller platforms, this increases administrative burdens, liability risks, and potential legal disputes. Lawmakers must consider these challenges, which could result in costly litigation as providers face expectations of near-universal fraud prevention. These issues will be explored further in the next section.

Table 2: Fraud types and ECSP responsibilities Source: ECIPE compilation.

Source: ECIPE compilation.

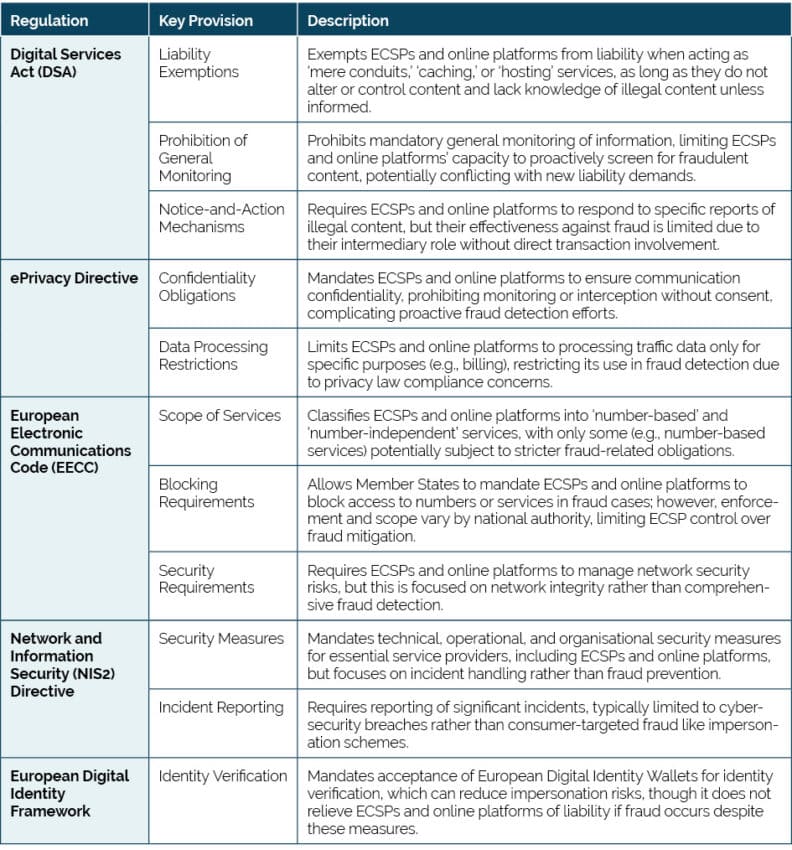

3.3. EU Legal Constraints on ECSPs and Online Platforms’ Roles in Fraud Detection and Mitigation

A recent report by the European Commission discusses several legislative frameworks and their implications for ECSPs and online platforms concerning fraud risk and new liability obligations proposed by the European Parliament.[14] Key legal issues affecting their capacity to engage in fraud risk elimination are outlined in Table 3. Fragmented EU data regulations pose legal and operational challenges for ECSPs and platforms, compounded by the Parliament’s liability proposals, which exceed their intermediary role. Privacy laws like the ePrivacy Directive prioritise user confidentiality, complicating fraud monitoring. Unclear liability frameworks and restricted data access are likely to spur litigation, as providers challenge disproportionate demands and the extension of liability to non-financial entities.

Table 3: Relevant legislation applicable to providers of electronic communications services and providers of intermediary services in the fight against payment fraud Source: ECIPE compilation based on European Commission (2024).

Source: ECIPE compilation based on European Commission (2024).

[1] EBA (2024). 2024 Report On Payment Fraud. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/intro/publications/pdf/ecb.ebaecb202408.en.pdf. High-value channels, such as credit transfers and card payments, are primary targets for fraudsters, representing the bulk of these losses. For instance, fraudulent credit transfers alone accounted for EUR 1.13 billion, while card fraud amounted to EUR 633 million in the first half of 2023.

[2] BlackHat (2024). A tech coalition to combat scams. Available at: https://insights.blackhatmea.com/a-tech-coalition-to-combat-scams/.

[3] GASA. The Global Signal Exchange. Available at: https://www.gasa.org/global-signal-exchange.

[4] StopScamsUK. Available at: https://stopscamsuk.org.uk/; also see: Europol. European Cybercrime Centre: EC3. Available at: https://www.europol.europa.eu/about-europol/european-cybercrime-centre-ec3.

[5] See, e.g., Metro Banks (2024). Meta partners with UK banks to combat scams. Availble at https://www.metrobankonline.co.uk/about-us/press-releases/news/meta-partners-with-uk-banks-to-combat-scams/. GASA (2024). GASA, Google, and DNS Research Federation Join Forces to Launch the Global Signal Exchange to Tackle Online Scams. Available at https://www.gasa.org/post/gasa-google-dns-research-federation-launch-global-signal-exchange. Amazon (2024). Protecting Consumers from Impersonation Scams. Available at https://trustworthyshopping.aboutamazon.com/focus/scam-prevention.

[6] See, e.g., Varner et al. (2022). Product Regulation and Liability Review Tenth Edition. Available at https://www.wolftheiss.com/app/uploads/2023/04/The-Product-Regulation-And-Liability-Review.pdf.

[7] See, e.g., Meyers (2024). Is the EU taking the right approach to APP fraud? Available at https://www.academia.edu/125484010/Is_the_EU_taking_the_right_approach_to_APP_fraud.

[8] See, e.g., Bello et al. (2023). Analysing the Impact of Advanced Analytics on Fraud Detection: A Machine Learning Perspective. Available at https://eajournals.org/ejcsit/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2024/06/Analysing-the-Impact-of-Advanced-Analytics.pdf.

[9] For example, in 2016, the phishing scam involving Belgian Crelan Bank resulted in losses amounting to EUR 75.6 million. See: The Brussels Times. (January 19, 2016). Belgian bank Crelan hit by a 70 million Eur fraud. Available at: https://www.brusselstimes.com/36335/belgian-bank-crelan-hit-by-a-70-million-eur-fraud.

[10] A vishing scam involving a gang operating from Ukraine targeted banking customers in Czechia, where they impersonated employees and police officers. See: The Record. (November 16, 2023). Ukrainian and Czech police bust $9 million bank fraud gang. Available at: https://therecord.media/bank-fraud-vishing-arrests-ukraine-czechia.

[11] In 2020, Europol announced it arrested over two dozen individuals suspected of draining bank accounts through SIM-swap fraud by hijacking victims’ phone numbers. See: Infosecurity Magazine. (July 7, 2020). A Concerning Proliferation of SIM-Swapping Fraud in Europe. Available at: https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/opinions/proliferation-sim-swapping-fraud/.

[12] Approximately two-thirds of retailers in Germany reported an increase in e-commerce fraud, while over 85 percent of online merchants in Switzerland indicated that they had fallen victim to fraud. See: Mastercard. (2024). Ecommerce fraud trends and statistics merchants need to know in 2024. Available at: https://b2b.mastercard.com/n.

[13] In October 2024, a suspicious Android banking Trojan campaign infected approximately 16 banking institutions across Italy, Portugal, and Spain, and Latin America. See: Security Affairs. (November 5, 2024). ToxicPanda Android banking trojan targets Europe and LATAM, with a focus on Italy. Available at: https://securityaffairs.com/170605/malware/toxicpanda-android-malware-targets-italy.html.

[14] Report prepared by European Commission Services submitted to the Council of the European Union, Working Party on Financial Services and the Banking Union (Payment Services/PSR/PSD). Financial Services Attachés. 13 September 2024.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

The European Parliament’s proposed shared liability model risks significant unintended consequences by imposing disproportionate responsibilities on ECSPs and online platforms:

- Misaligned Roles: ECSPs and online platforms are communication intermediaries, not fraud managers, and lack the tools or involvement to oversee and control financial transactions. This misalignment fosters a moral hazard, as financial institutions may shift responsibility away from themselves, reducing their investment in fraud prevention.

- Privacy Conflicts: Fraud monitoring clashes with privacy laws like the ePrivacy Directive, creating legal and operational challenges.

- Litigation Risks: Ambiguous liability attribution would lead to costly legal disputes and slow fraud responses, deterring market entry, market churn, and competition.

To ensure effective fraud prevention, regulatory focus should remain on financial institutions directly managing transactions, identities, and accounts. Targeted and collaborative solutions, rather than broad liability extensions, can address fraud risks effectively while preserving innovation, competition, and consumer protection.

- Enhanced Consumer Education: Coordinated awareness campaigns should empower consumers to identify and avoid scams. Strengthened consumer vigilance reduces the burden on companies and bolsters fraud prevention efforts.

- Proportionate Regulatory Burden: Non-financial entities should be encouraged – but not legally required – to collaborate on fraud prevention, as they already have strong incentives and are actively working to combat fraud to protect their businesses. Introducing legal liability for non-financial entities risks disproportionately burdening smaller firms, which may leave the market or avoid entering it altogether due to the extreme complexity of managing fraud detection. This would lead to legal uncertainties, costly legal disputes, and market exits, driving market concentration and reducing competition in communication and digital services. A shares liability regime for non-financial entities would thus undermine EU and Member State efforts to spur Europe’s lagging digital start-ups and scale-ups, creating setbacks to the EU’s digital ambitions.

- Improved Data-Sharing Mechanisms: Establish an EU-wide fraud database to streamline data collection and analysis across Member States. Such a centralised system would enhance fraud prevention, especially for smaller PSPs that lack advanced detection systems. However, any data-sharing mechanisms must comply with GDPR to safeguard consumer privacy.

- Fostering Voluntary Cooperation: Encourage private-public partnerships between financial institutions and regulators to address fraud collaboratively without imposing legal liability on entities that cannot oversee and as such do not control financial transactions. Examples such as the “Fraude Fight Club” in France, where law enforcement, the Central Bank, retailers, e-commerce platforms, and PSPs coordinate anti-fraud strategies, and the Integrated Approach to Online Fraud in the Netherlands, which brings together web shops, banks, carriers, and law enforcement, showcase the effectiveness of voluntary cooperation in combating fraud.[1]

- Recognition and Alignment of Existing Frameworks: Harmonise data policies such as the DSA and GDPR, to prevent legislative overlap, barriers to data-sharing, and legal risks. Public-private partnerships, such as Finland’s collaboration between Traficom and telecom operators to block scam calls, and Hong Kong’s partnership between the police and banks to provide real-time scam alerts, demonstrate how sector-specific cooperation and innovation can empower consumers and reduce fraud risks without imposing disproportionate legal liability on non-financial sectors. [2]

[1] See, e.g., FBF (2023). Fraude Fight Club : une initiative inédite sur Instagram pour sensibiliser les jeunes aux cybermenaces. Available at https://www.fbf.fr/fr/fraude-fight-club-une-initiative-inedite-sur-instagram-pour-sensibiliser-les-jeunes-aux-cybermenaces/. GASA (2024). The Dutch Integrated Approach to Online Fraud, Julia Smeekes, Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security – Global Anti-Scam Summit Europe 2024. Available at https://www.gasa.org/post/the-dutch-integrated-approach-to-online-fraud-julia-smeekes-dutch-ministry-of-justice-and-security.

[2] See, e.g., Traficom (2023). Obligations of the Regulation come into effect – up to 200,000 scam calls are prevented per day. Available at https://www.traficom.fi/en/news/obligations-regulation-come-effect-200000-scam-calls-are-prevented-day. Vixio (2022). Scameter: Hong Kong’s New Tool In Fight Against Fraud. Available at https://www.vixio.com/insights/pc-scameter-hong-kongs-new-tool-fight-against-fraud.