Covid-19 and the Danger of Self-sufficiency: How Europe’s Pandemic Resilience was Helped by an Open Economy

Published By: Johan Norberg

Subjects: European Union New Globalisation WTO and Globalisation

Summary

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Europe has benefitted strongly from being an open economy that can access goods and services from other parts of the world. Paradoxically, some politicians in Europe think that dependence on foreign supplies reduced the resilience of our economy – and argue that Europe now should wean itself off its dependence on other economies. In this Policy Brief, it is argued that self-sufficiency or less economic openness is a dangerous direction of policy. It would make Europe less resilient and less capable of responding to the next emergency.

It is key that people, firms and governments can get supplies from other parts of the world. It is diversification, not concentration of production, that will make Europe more resilient when the next emergency hit. We don’t know where the next crisis will come from. Nature will throw nasty surprises at us, and we will make stupid mistakes, some of which will have devastating consequences. What we do know, though, is that we stand a better chance to fight the next emergency if we get richer and improve our technology. The best policy for resilience is one that encourages specialisation and innovation – and, when the emergency hit, allow for people to improvise in search for solutions. For that to happen, we need openness to goods, services and technology from abroad.

Johan Norberg’s latest book is Open – The Story of Human Progress.

The rise of disaster protectionism

In Naomi Klein’s book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, she argues that economic liberals have used disasters to ram through unpopular economic reforms.[1] It is true that emergencies tend to change the policy direction of a country, but it is far more common that crises lead to the exact opposite of what Klein proposed. Public spending and government power tend to expand in response to a crisis, a terrorist attack, war, economic depressions – and pandemics.[2] And perhaps there’s a human logic to it: when we feel threatened, we look to the government for protection. This also goes for trade protection – and the present pandemic is a case in point. Call it disaster protectionism.

Consider Europe’s initial response to the pandemic. The European Union shut its external borders in March 2020 to keep the virus out – just when Europe had become the global epicentre of the disease. And for a while, trade dropped like a stone – affecting the supply of food, labour and hand sanitizers across the continent. If Pfizer and BioNtech had not had access to corporate jets, they would not have been able to send genetic material over the Atlantic Ocean to develop the first successful Covid-19 vaccine.

Meanwhile, new borders within the union were erected, suspending free movement, sometimes stopping citizens from getting back to their home country after losing their jobs during lockdowns.

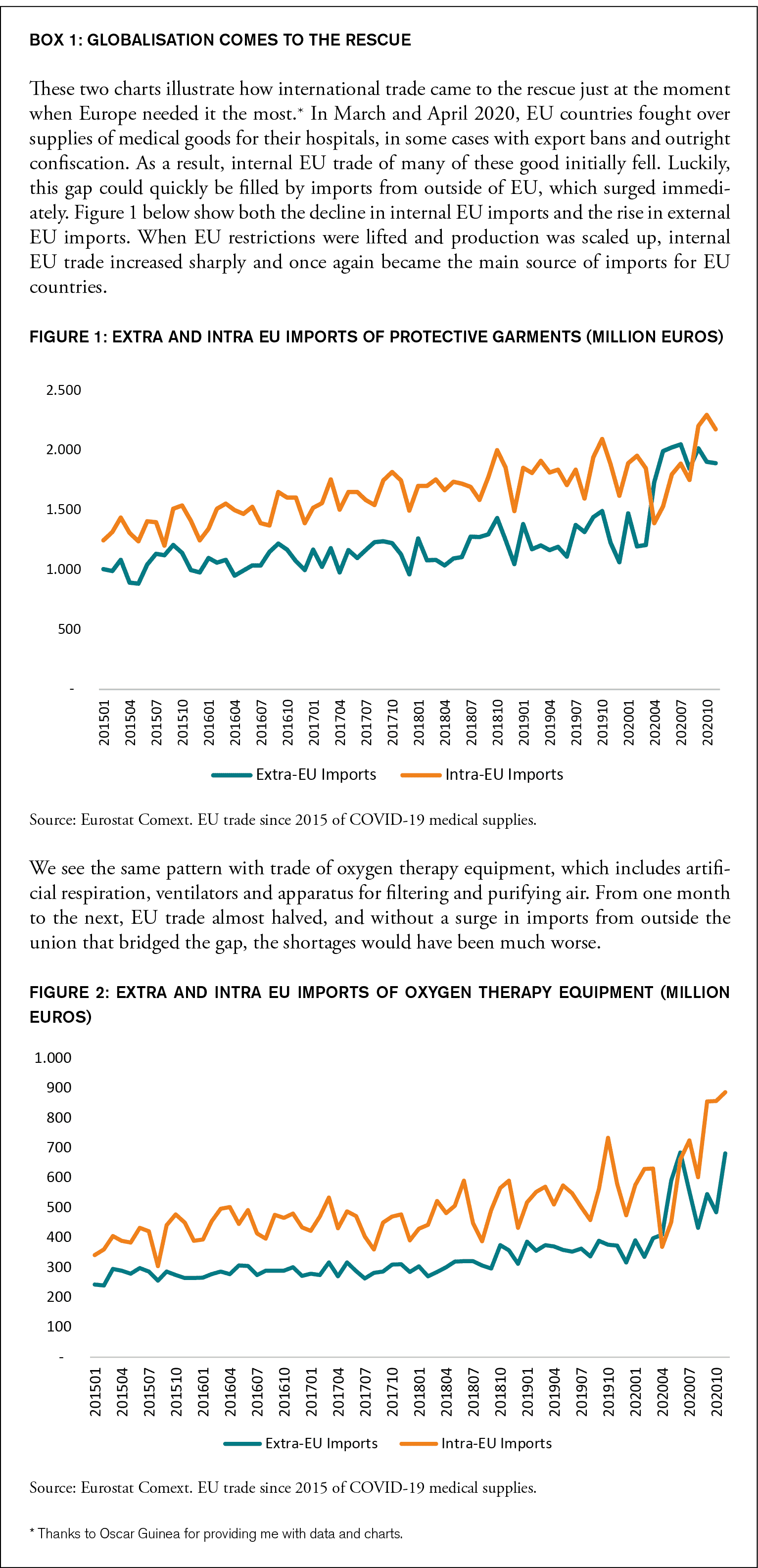

France and Germany banned the export of personal protective equipment. In March 2020, France even started confiscating equipment produced in other countries sent through the country by third parties. As a result of these restrictions, internal EU trade of the medical goods needed to treat Covid-19 went down by 13 percent between March and April of 2020, a reduction that was especially damaging for oxygen therapy equipment, which fell by 42 percent (see Box 1 Globalisation comes to the rescue) After the European Commission stepped in, controls were lifted, but other forms of export restrictions were re-created at the EU level, prohibiting exports unless a license was obtained. Companies producing medical supply were wrapped in extra red tape just when the speed of supply was a matter of life and death.

The pandemic spurred strong calls for bringing manufacturing back home. Some politicians asked: How can we withstand a crisis like this, if we don’t even have local production of face masks, surgical gloves and pharmaceutical inputs? The fact that most of this production is based in Asia is worrying, said the German Chancellor Angela Merkel in April 2020, and called for “a pillar of domestic production here too”.[3] The European Commissioner for Health, Stella Kyriakides, expressed the same sentiment: “we need to ensure that we reduce our dependency on other countries.”[4]

For some, the pandemic urged new calls for broader trade protection – not just in medical goods. The pandemic, they argued, have revealed how dependent that countries and supply chains are on companies on the other side of the globe: if these suppliers would reduce or divert supplies, wouldn’t our assembly lines grind to a halt? Some governments created incentives to repatriate supply chains and build national champions, rushing headlong back in time to the industrial policy of the 1970s.

Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton claimed that “the question posed to us by this crisis is that we have perhaps gone too far in globalisation”, not just when it comes to pharmaceuticals and protective equipment, but also in manufacturing and agriculture. And as an harbinger of what policies he would later propose, Breton said: “I am convinced that our relationship to the world after this crisis will be different.”[5]

And when the solution seemed to be at hand, in the form of vaccines developed through global research collaboration and the international flow of data, the EU succumbed to vaccine nationalism, raising the prospect of banning exports of vaccines produced within the union, even momentarily threatening a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

When international cooperation was needed the most, Europe undermined its reputation as a champion of open markets and the rule of law in international affairs. Poor countries that had opened up their economies to the EU are now questioning whether it is a reliable supplier of essential medical equipment in the future. Pharmaceutical companies ask themselves if they should relocate to smaller countries that would never have an incentive to block exports.

This development was sadly predictable. In times of crises, societies often react with a fight-or-flight instinct. We pick fights with some and make scapegoats of others – immigrants, neighbouring countries, or pharmaceutical companies. Some politicians want to hide behind walls, others behind trade barriers. Instinctively rushing to defend the perimeter might have made sense in mankind’s pre-history, when the threat was predators and roving bandits. But in a complex and global economy, where necessary resources to solve societal problems are spread across the world, we surely shouldn’t attack outsiders. And when the common enemy is a virus, wouldn’t it better to cooperate with outsiders to build up more knowledge and produce better solutions? And wasn’t that the spiritual foundational of the EU?

[1] On closer inspection, it turned out that she came to the conclusion by taking quotes out of context, distorting timelines and confusing free market policies with crony capitalists, hungry for government support. See Johan Norberg, ”The Klein Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Polemics”, Cato Briefing Paper No 102, 14 May, 2008.

[2] Robert Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government. Oxford University Press, 1987. Johan Norberg, Open: The Story of Human Progress, Atlantic Books 2020.

[3] “Statement by Federal Chancellor Merkel”, Office of the German Federal Government, 6 April, 2020, <https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/coronavirus/statement-by-federal-chancellor-merkel-1739724>

[4] ”Covid-19 exposes EU’s reliance on drug imports”, Financial Times, 20 April, 2020.

[5] Thierry Breton estime nécessaire l’émission d’obligations pour faire face à la crise”, Le Figaro, 2 April, 2020, <https://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-eco/thierry-breton-estime-necessaire-l-emission-d-obligations-pour-faire-face-a-la-crise-20200402>

Self-defeating protections

Many of the protectionist measures were immediately self-defeating, because you can’t shut out a world that you are an integral part of. Supply chains are not really chains, but complex webs of production and exchange, where a single medical product has many inputs that crosses external borders, sometimes several times.

When Romanian ventilator hoses were classified as a “medical device”, their export to Switzerland was initially banned, threatening the production of Swiss ventilators that EU hospitals waited for (and leaving Romania with hoses that are completely useless on their own).

Half of the workers in a major Czech factory producing personal protective equipment travel from Poland every morning. The closure of the border between the countries meant that these workers could not make it to their jobs, resulting in a shortage of necessary products for European countries.

On 5 March 2020, French authorities confiscated Mölnlycke’s entire supply of surgical masks in Lyon. This stopped one million masks purchased by Italians and one million by Spanish customers. The masks were produced in Asia, and Lyon was just a distribution centre, so Mölnlycke quickly rerouted supplies via Belgium and used air freight to get them to the worst affected parts of Europe. The end result was increased costs and delayed access to critical protective gear.

Restricting exports of PPE is like hoarding toilet paper. It provokes everybody else to hoard as well, with the result that the product cannot be accessed on the market for those who need it. Such beggar-thy-neighbour policy has often been seen during food price crises. Partly due to higher fuel prices, international food prices started increasing in 2010 and to keep prices low, many countries banned exports – triggering others to do the same. Around 40 percent of the increase in wheat prices was the result of such bans.[1]

[1] Csilla Lakatos, David Laborde and Will Martin, “Reacting to Food Price Spikes: Commodity of Errors”, Let’s Talk Development blog, World Bank, 5 February 2019, <https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/reacting-food-price-spikes-commodity-errors>

Impossible self-sufficiency

Self-sufficiency is not possible for a rich, industrialised economy. The very basis of our economy, even local transportation and agriculture, requires the import of fuel, seeds and mineral fertilizer. That is why autarky has been abandoned as a concept also in governments contingency plans: governments rather make plans for how to keep markets open and reroute supplies in the event of war.

One difficulty is that no government knows where the next crisis will come from. In the summer of 2018 we had major forest fires in Sweden and many Swedes complained that the country had too few fire trucks and water bombers. In 2019, we had too little animal feed, and many claimed that Sweden needed to set aside more land to grow it. In 2020, the new coronavirus created a shortage of important supplies and Swedes complained that we had too few face masks.

So what’s the best response? To have a chronic oversupply of everything that might come in handy – water bombers, animal feed or face masks – when the next unpredictable disaster strikes? Or to be flexible, keep supply lines open and steer resources to where it turns out to be needed for the moment?

For example, instead of every country having expensive water bombers that almost never take off, the EU has decided to pool and therefore expand their resources. So water bombers could fly from Italy to Sweden to deal with the forest fires in 2018.

International trade functions in the same way. We produce what we need where it’s possible to do it better and cheaper, so that we can get more of it when we need it. Of course, we could subsidize a face mask industry in Europe that churns out 10 cent masks, but having such excess capacity when there is no pandemic would be incredibly costly – and not just through the subsidy. It would use resources – labour and capital – that could be allocated to higher value-added activities. Importing the masks at a fifth of the cost and put some of them in stockpiles for a possible emergency would be a far better option.

Perhaps it’s costly to have an overcapacity, some say, but it would save us when disaster strikes. But no, it wouldn’t. China is the world’s biggest producer of face masks, the country that is so dominant in this industry that we all worry about it. Still, that was not anywhere close to enough when demand suddenly jumped 20-fold. China had to import two billion masks to deal with the outbreak in Wuhan, before it could ramp up domestic production sufficiently.[1]

[1] “China Delays Mask and Ventilator Exports After Quality Complaints”, New York Times, 11 April 2020.

Dangerous self-reliance

The new disaster protectionism is based on the assumption that local production is the safer option. If only we weren’t dependent on global supply chains, the thinking goes, we wouldn’t have to fear major disturbances in times of crisis. It is true that it is not risk-free to rely on foreigners for necessary supplies. However, even the most cursory glance at human history shows that it is not risk-free to rely on local supplies either.

Before the era of modern infrastructure and international trade, bad weather could mean that an entire region starved. Most emergencies are by their nature local or regional. Epidemics, wars, depressions or extreme weather events – they tend to strike regions that are close geographically and integrated economically and culturally. Even when the threat is global, like the Covid-19 pandemic, it does not affect every region at the same time. When it first affected East Asia, Europe was still open and could supply Asia with important goods. When Europe went into lockdown, Asian factories had started opening up, and could export essential products. Had European countries been completely dependent on local supply chains, we would have been more vulnerable – not less.

An assessment of the impact of a pandemic shock on 64 economies showed that a country with repatriated supply chains would not just be a much poorer country, but also suffer a stronger contraction than others in times of crisis. The reason? The supply of good is much more resilient when they come from a variety of geographic sources – compared to just one country, your own. The researchers also looked at individual economic sectors and concluded: “There is no sector in which supply chain renationalization notably improves resilience, measured either by GDP, or by value added of the sector itself.”[1]

The claim that we are completely at the mercy of the outside world is not accurate. Partly due to the success of the internal market, European goods are usually imported from other European countries. EU members capture more than half of the EU imports market share in three quarters of all imports.

In an ECIPE study, Oscar Guinea and Florian Forsthuber find that there are only 112 products (out of 9,700) for which the four largest suppliers are non-EU countries. These 112 goods represent no more than 1.2 percent of all EU imports. Strikingly, none of them is a Covid-19 related medical good. Those supplies are already diversified. The average Covid-19 good is imported from 46 countries. There was no Covid-19 related product where the EU had less than a 20 percent market share, which means that there is already a “pillar of domestic production”, to quote Chancellor Merkel. The knowhow exists here and it is possible to ramp up production if other countries were to cut us off.[2]

Much has been made of the fact that Europe has made itself dependent on China for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), but the EU actually hosts twice as many factories that produce them as China – 26 versus 13 percent. 28 percent of the roughly 2,000 manufacturing facilities are in the United States, and 18 percent in India.[3] Around 71 percent of EU imports of APIs were imported from within Europe: 51 percent from the EU itself, 17 percent from Switzerland, and 3 percent from the UK. It’s true that China and India accounted for 25 percent of the volume of EU total imports of pharmaceutical ingredients, but these countries only represent 11 percent of the value of EU imports of these products[4]. The point is: Europe simply isn’t dependent on China for its supply of APIs.

Those in Brussels who make big claims about the need to reduce dependency should be careful what they wish for. Europe has a big trade surplus in pharmaceuticals: if Europe cuts its dependency on the rest of the world, the rest of the world is likely to cut its dependency on Europe. And if that argument doesn’t bite: there are already those in Europe who claim that their country is too dependent on others for their medicines – that is, too dependent on other EU countries. The agenda for greater independence risks striking at the heart of the EU.

It isn’t just about pharmaceuticals. You would not guess it from the media reports, but eight of the world’s ten biggest exporters of medical goods are European. The world leader is Germany, which exports two and a half times more than China. China is just the 7th biggest exporter of medical goods, with 5 percent of the world market, and its exports are mostly about low value-added goods – like personal protective products, where China has a 17 percent share.[5]

Resilience is built through diversification, not the concentration of supply chains. The reason why you shouldn’t put all your eggs in one basket is that there is a greater risk that one basket will break than many. EU countries are already dependent on each other. By opening up, Europe becomes more diversified and therefore more resilient when the unexpected happens. For example, in 2020, year-on-year imports from outside the EU of medical gloves, thermometers, and disinfectant went up by 61, 76, and 242 percent[6]

Some companies that have developed a manufacturing model with on-time deliveries suffer from disruptions, and they are now learning that they need more inventory or more diverse suppliers. Sometimes they do it by cutting down on custom parts and rather designing products with standardized components. Every company has to find its own balance between just-in-time and “just in case”. Where to find that balance is not given, there is no simple formula: it depends on local circumstances and it changes with the development of technology. We need experiments, not commands.

[1] Barthélémy Bonadio, Zhen Huo, Andrei Levchenko & Nitya Pandalai-Nayar, “Global Supply Chains in the Pandemic”, NBER, Working Paper 27224, May 2020.

[2] Oscar Guniea & Florian Forsthuber, “Globalisation Comes to the Rescue”, ECIPE, Occasional Paper, 6, 2020.

[3] Scott Lincicome, “On ‘Supply‐Chain Repatriation,’ It’s Buyer (And Nation) Beware”, National Review, 28 April 2020.

[4] Erixon, F., & Guinea, O. (2020). Key Trade Data Points on the EU27 Pharmaceutical Supply Chain. ECIPE, Brussels.

[5] WTO, “Trade in Medical Goods in the Context of Tackling Covid-19”, Information Note, 3 April 2020.

[6] Data for December 2020 was not yet available in Eurostat at the time of writting, therefore the year-to-year comparison comprises January to November of 2019 and January to November of 2020.

Globalisation worked

You rarely hear anyone making the case that global markets failed during the crisis; we are mostly confronted with hypothetical scenarios about how they could have broken down. Disaster protectionism is the solution to an imagined problem, not a real one. In fact, globalisation has been tested under the most difficult circumstances, and it passed it with flying colours.

Europe had local knowhow and a level of wealth and technology that made it possible to quickly expand production of everything that we suddenly needed. Vodka distilleries and perfume producers began manufacturing disinfectants and hand sanitizer. Hygiene businesses switched to producing medical gloves and surgical masks. In less than two months, the number of European companies producing face masks increased from 12 to 500.[1]

Meanwhile, globalisation came to Europe’s rescue. EU countries could buy 40 percent of its test kits from outside the union and while imports of face masks from other EU members increased by 45 percent, imports from the rest of the world surged by 769 percent.[2]

Other countries did not stop their exports to us but instead expanded production to meet our orders. And if Europe wants to minimise the risk of that happening in the future, it surely doesn’t help if we get the reputation of being an unreliable trading partner that – if given a chance – would treat them badly.

If you are looking at the capacity for market adaption, look no further than the shelves of your local supermarket. During the pandemic, the world’s food industry has faced a perfect storm of sudden restrictions, shipping disturbances, labour shortages (especially migrant workers), and more. Yet, by around-the-clock production, switching suppliers, changing production methods and rerouting distribution, the global food industry managed to overhaul and rebuild global supply chains in just a few weeks. As a result, our shelves are well-stocked. It is an amazing achievement that has gone largely unnoticed. It was the dog that didn’t bark.

This worked because the food market isn’t planned and centralized. Every tweaking of the manufacturing process and every rerouting of supplies depended on local knowledge about what can be done in a particular place with the workers and inputs available, and what they could stop doing without creating devastating shortages in other places. This knowledge only exists on the ground, in individual businesses, and is transmitted through the price system. A functioning price system is never more important than when the world changes quickly in unpredictable ways.

[1] “EU should ‘not aim for self-sufficiency’ after coronavirus, trade chief says”, Financial Times, 23 April, 2020.

[2] Guinea & Forsthuber 2020.

Mobilitate Vigemus

An important policy implication is that we should take a long hard look at the speedbumps in our economy. We have countless of regulations and local standards that are meant to keep us safe, but which slows down the adaptation when things suddenly change. When businesses source goods from a new place, they have often been bogged down in lengthy approval processes.

Hospitals lack PPEs even though some companies have warehouses filled with unsold stock, since WHO and government guidelines restrict the marketing of new products. It is supposed to keep inadequate gear off market, but has the perverse effect that it’s easier to find anti-vax propaganda online than information on where to buy protective equipment.

If we want to encourage swift adjustments, we should get rid of import tariffs and export restrictions. We should enter trade agreements with more countries, to diversify our potential supplies. We should accept the regulatory processes of more countries so that we can instantly buy medical products from them when needed. Inspiration could come from the regulatory system South Korea created after the 2015 MERS epidemic, which fast-tracks medical approvals when the country faces emergency situations.

We don’t know where the next crisis will come from, so there is no one protected basket in which we can put all our subsidised eggs. Nature will throw nasty surprises at us, and we will make stupid mistakes, some of which will have devastating consequences. What we do know, though, is that we stand a better chance to fight the next emergency if we get richer and improve our technology. The best policy for resilience is one that encourages specialisation and innovation – and, when the emergency hit, allow for people to improvise in search for solutions. For that to happen, we need openness and decentralised economic structures.

Local is unsafe and protectionism is hazardous for your health. Instead of building fortresses, we should heed the old cavalry motto “Mobilitate Vigemus”. In mobility lies our strength.