Combating Unsafe Products: How to Improve Europe’s Safety Gate Alerts

Published By: Guest Author

Subjects: European Union Sectors

Summary

By Joana Purves, Researcher at E+Europe and William Echikson, Director E+Europe

The European Union has built a one-stop-shop for its member state regulators to post product safety notifications – Safety Gate (European Commission 2021d). Constructed on top of the Rapid Alert System for Dangerous Non-Food Products, or RAPEX, the Safety Gate web portal is designed to make public the “quick exchange of information” between 31 European countries and the European Commission “about measures taken against dangerous non-food products.”

While Safety Gate represents a significant achievement, our research revealed areas for improvement to increase its utility for manufacturers, marketplaces and consumers. Many product notifications published on the website lack details required to facilitate speedy removals and recalls.

The study graded eight essential criteria for a total of 918 Safety Gate notifications published over eight months in 2020. The average notification score was a respectable 70 out of 100, but over 98% of the notifications omitted at least one key criterion. Only 14 notifications included all the information to enable efficient and accurate product identification.

Key failings include:

- Notifications often lack complete information for easy detection and removal of unsafe products from sale.

- Recalls often contain few contact details, complicating efforts to remove them from the sale.

- Poor quality notifications come from all over the continent. No significant quality differences are visible in notifications from any single country or region.

- Notification quality even varies from within the same country, such as these two examples published by the same authorities: a well-designed alert for a USB charger (RAPEX 2020s) and a poor alert for another USB charger (RAPEX 2020t).

This study aims to provide ideas for filling the gaps. The Commission itself recognised the need for modernisation in its 2019 updated guidelines (European Union 2019a). These provide extensive explanations of how to assess risks and tackle dangerous products.

Product safety enforcement represents a European policy priority. The European Consumer Organisation BEUC demands, justifiably, that consumers be protected and that the EU “keep its safety legislation up to date” (BEUC 2020a). At the same time, BEUC recognises that “even the strongest laws will be meaningless unless authorities enforce them in practice. A major role lies with EU member states to dedicate enough resources, time and energy to do so” (BEUC 2020a).

The COVID-19 pandemic adds urgency for reform. “Due to the coronavirus crisis, online purchases have surged and so have online scams. We cannot stand by and watch how fraudsters play on consumers’ vulnerabilities,” European Justice and Consumer Affairs Commissioner Didier Reynders warned at last year’s International Product Safety Week (Reynders 2020).

In March, 2021, the European Commission published its annual Safety Gate report, reporting a record 5,377 “follow-up actions,” compared to 4,477 in the previous year (European Commission 2021c). Although details of the action were not offered, 9% of alerts concerned dangerous masks and sanitizers to protect against the virus. Many of these notifications lacked sufficient details to facilitate quick removal. Several notifications of unsafe masks, such as this mask that contained no product name, no product reference code or no model name (RAPEX 2020l).

The upcoming review of the General Product Safety Directive represents an opportunity for improvement. The Directive “is almost 20 years old and as such does not reflect recent developments in products and markets,” the Commission noted in its recent paper outlining policy options (European Commission 2020). A formal proposal is planned for the second quarter of 2021.

Well-documented notifications speed-up public knowledge and effective recalls of dangerous products. Both the U.S. and Australia, with a single federal government and a single working language, operate effective, centralised unsafe product notification and recall systems. In contrast, the European Union needs to coordinate the work of 31 national authorities and in multiple languages. The national regulators produce the dangerous product notifications. While the European Commission unit responsible for product safety reviews them before publication asking for clarifications or corrections, it depends on the work of these national regulators.

Progress will require action from all stakeholders. A single, standardised format for unsafe product notifications represents a basic framework for ensuring safety in the Internet age. Manufacturers, marketplaces and consumers must receive clear descriptions of dangerous products that have been placed on the market and clear instructions on how to respond to risks. Increased dialogue between marketplaces, consumer groups, and both European and national regulators could prove fruitful.

The authors acknowledge financial support from Amazon and Rakuten for this report. Justus Becker and Benjamin Echikson assisted in the research. William Echikson consults for Rakuten and helps represent the company in the Product Safety Pledge.

1. Introduction: Europe's Product Safety Challenge

Efforts to harmonise European regulations on unsafe products began in the 1970s. Progress proved slow. While several directives clarified definitions of consumer rights and required member states to inform the Commission about measures to combat dangerous products, national governments retained overwhelming responsibility for detection and enforcement.

The 2001 General Product Safety Directive represented a milestone. It gave birth to the Rapid Alert System for Dangerous Non-Food Products, or RAPEX (European Union 2002a). For the first time, European Union law required member states to notify unsafe products to Brussels. RAPEX includes EU countries, as well as Liechtenstein, Norway, Iceland and post-Brexit UK. In all, a total of 31 countries participate. Although Northern Ireland remains in the network, the rest of the United Kingdom left after Brexit. Businesses benefit from the Business Gateway to warn national authorities about a product that they have put on the market, which might be unsafe (European Commission 2021b).

Literature Review

The European debate on product safety centres around the proper balance between decentralization and centralization. In the article “Product Liability and Product Safety in Europe: Harmonization or Differentiation” (2000), Maastricht University professor Michel Fauré called into question the plausibility of the European Commission’s goal of harmonising recalls. Although Fauré acknowledged that centralised product safety standards could facilitate trade within the single market, he questions the economic logic behind these efforts. In his view, local authorities are most effective in developing and enforcing appropriate rules for their individual markets, and member states need to enjoy the freedom to impose strict or weaker standards depending on their overall economic policies.

After the passage of the 2001 General Product Safety Directive, the rise of the Internet, e-commerce, and a rise of non-European imports, the tone shifted. In their article “General Product Safety – a Revolution Through Reform?” (2006), Duncan Fairgrieve of Université Paris Dauphine and Geraint G. Howells of Lancaster University Law School, back increased central enforcement, or what they describe as the “‘Americanization’ of EU product safety” (2006, 65). In the U.S., the federal government runs a single nationwide product safety program, with both notification and enforcement powers. Fairgrieve and Howells see the same need in Europe.

Over the following decade and a half, in a series of articles and books, Professor Fairgrieve stepped up his calls for reform (2013; 2017; 2020). In order to counter diverging and varying standards between the Member States, he endorsed a reinforced EU-wide system.

The U.S. centralised recall system soon emerged as a model. In her 2014 paper, Professor Lauren Sterrett of the Michigan State University College of Law, compared EU and U.S. product liability laws. The U.S. provides accurate and clear information and instructions to all parties in the production and distribution chain. A clear philosophical difference exists across the Atlantic Ocean. The U.S. system allows consumers to sue in court and obtain large financial damages. In Europe, Professor Sterrett notes that this right still does not exist.

Recent studies suggest practical improvements. Europe’s definition of ‘serious risk’ must be strengthened and clarified (Wijnhoven et al., 2013). A separate 2018 report suggests notifications should be required to contain the exact product name, description and the name of the manufacturer and/or seller (Pigłowski 2018, 183). Improved communication with consumers was recommended, including the creation of a smartphone application to send out alerts about dangerous products.

Evolution of RAPEX and Introduction of Safety Gate

RAPEX has expanded in scope and quality over time. In 2004 the Commission provided clearer criteria for alert notifications and a methodological framework to help authorities assess product risk. In 2010 the Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 expanded RAPEX’s scope from just consumer health and safety to include other risks such as security and environmental damage (European Union 2008).

In 2018, the Commission renamed RAPEX as Safety Gate and instituted significant consumer-friendly improvements (Jourová 2018). Public data of Safety Gate became available in 25 languages, and its notifications could now be shared easily on social media. The 2019 guidelines offered details of the information required for effective withdrawals.

We examined four different weekly reports published on the Safety Gate website from the same week in June over five-year intervals to illustrate improvement.

- In 2005, alerts were bare-boned. A single sentence warned about this jacket (RAPEX 2005) that could suffocate small children. The notification contained no brand name, no model number, and no serial number. Recall measures were weak.

- In 2010, the weekly reports included corrections and updates about products from national authorities at the top of the page. Many alerts still involved only voluntary actions for the manufacturer or distributor to remove the product from sale, such as this toy (RAPEX 2010).

- The 2015 report included additional significant upgrades, such as the possibility of a personalised alert subscription.

- The 2020 weekly report from June 9th contained alerts of varying quality: some included most of the key details needed for effective follow-ups by other Member States such as these fireworks (RAPEX 2020f). Others lacked crucial details, such as this ear-piercing jewellery (RAPEX 2020m).

In March 2021, the European Commission unveiled a revamped Safety Gate. The makeover improved the search engine and design. On the old Safety Gate website, notifications of dangerous products were categorised under colour-coded headings denoting different risk levels. This categorisation was vague and confusing to consumers. The modernized Safety Gate eliminates the color coding and testifies to the European Commission’s commitment to improve product safety communication.

Are there more unsafe products reaching the European Single Market?

Targeted mystery shopping by European consumer groups offer worrying reports of fire alarms that failed to detect smoke, toys that contained high chemical levels, and a power bank that melted (BEUC 2020b).

Yet these mystery shopping exercises target a narrow range of risky products and the overall number of notifications of unsafe products does not reflect increasing danger. While Safety Gate witnessed a steady increase of notifications during its first decade of operation, it has recorded around 2,000 alerts annually over the past eight years. A total of 2,253 alerts were published in 2020 (European Commission 2021a, pp.5). Either the continent’s market surveillance authorities have failed to keep up with e-commerce, or consumer groups are exaggerating the problem.

Despite the challenges of verifying online purchases, European Commission studies show that brick-and-mortar stores continue to sell the vast majority of unsafe products. Some 80.1% of consumer concerns about unsafe products “were linked to offline purchases,” compared to only 18.6% purchased online. Even after discounting the large percentage (46.5%) of automobile recalls – almost all cars are purchased in-person – complaints about in-person purchases outnumber online ones by about two to one (European Commission, 2019b, pp.16).

A few product categories account for most safety issues. In the Commission’s most recent Safety Gate annual report looking at results from 2020, 27% of unsafe concerned toys, 21% motor vehicles, 10% electrical appliances and 9% COVID-19 related (European Commission 2021c).

Consumer knowledge about recalls of products remains weak. A 2018 European Commission report polled European consumers and concluded that only about half had been exposed to product recall information. Knowledge of product recalls varied by product type, from 22.5% for cosmetics to 78.8% for cars and other motor vehicles (European Commission 2019b, pp.15).

When consumers become aware of a recall notice concerning a purchase, 55.7% of them contact the manufacturer or seller for more information and 41.3% for reimbursement (European Commission 2019b, pp. 20). Almost half, 46.3%, return the unsafe product. Another 7.3% threw it away. More than a third (35.1%) continue using recalled products, suggesting that the danger is either not severe enough or communicated in a clear enough fashion for them to take action.

The European Commission collaborates with international partners such as OECD in campaigns to raise awareness about recalls (OECD 2019). It pledged in its latest Safety Gate report to make recall effectiveness a priority (European Commission 2021a, pp.11). A new study on improving the success of product recalls for consumers is set to be published later in 2021.

China represents the source of the biggest percentage of problematic products, accounting for about half of Safety Gate alerts (European Commission 2021a, pp.9). The European Commission launched formal cooperation on product safety with Chinese authorities in 2006. Chinese authorities follow up on dangerous Chinese products notified in the Rapid Alert system and inform the Commission of their actions. The EU-funded SPEAC project (Safe non-food consumer Products in the EU And China) offers training to Chinese manufacturers about European product safety rules (SPEAC 2021).

Four marketplaces, Alibaba, Amazon, eBay and Rakuten, signed a Product Safety Pledge in 2018 with the European Commission. The marketplaces committed to check Safety Gate and remove dangerous product listings from their websites. In July 2019, the Commission’s first progress report reported that 87% of the product listings flagged to them by the authorities were removed within two working days (European Commission 2019a). In 2020, five other marketplaces Wish, Allegro, Cdiscount, bol.com and eMag – entered the pledge, and on March 1, 2021, other Etsy and Joom joined.

2. Methodology

We graded alerts from a total of 33 Safety Gate weekly reports from January to August 2020.

Our research omitted notifications about automobiles because manufacturers have developed an effective vertically-integrated recall system. Though that system works well for automobile recalls, it is not relevant to most retail items, which follow a tortuous path from manufacturer to consumer.

We did not review food products either. They are not included in Safety Gate and are covered instead under a separate General Food Law (European Union 2002b).

We graded notifications of physical consumer products, many of which are sold online by third-party merchants. Toys, electrical goods, and chemicals appear most often. These consumer products presenting dangerous profiles depend on a decentralised production and distribution channel.

Safety Gate includes two types of notifications: a notification for information and a formal alert.

For products that pose little risk to consumers or for which authorities have few details or for which the risk level cannot be determined, a notification for information is published. For this type of notification, no legal obligation exists for other countries of the network to follow up on these cases. By definition, the Commission acknowledges that these alerts contain insufficient information. It works under the principle that it is best to publish something rather than nothing and ignore a potential danger. We did not grade these notification alerts.

For a formal alert, the dangerous product must meet several criteria of either Article 11 or Article 12 of the General Product Safety Directive (European Union 2019a, 124) and article 23 and 22 of Regulation EC N0 765/2008. We graded these formal alert notifications.

A total of 1020 products were graded. After excluding the 102 “notifications for information” from our final analysis, the final total of graded product alerts was 918. The Safety Gate alerts studied for this analysis were accessed from September to December 2020. Since that time, some of the notifications may have been updated or amended and may continue to be updated to improve their quality. For example, the link to the 2005 alert for a jacket now has a brand and reference numbers Jeans jacket “H&M” for boys of 8 – 18 months (432740-6512 & 432741-6512, code CN 620920009.

2.1 Criteria and Scoring

Each product was graded according to the below criteria. We chose these categories after discussing with product safety experts, who considered them the key data points required to locate and recall unsafe products.

- PRODUCT NAME (20 points). All Safety Gate notifications list the product category such as cosmetics and toys. It would be best to also have a specific product name such as mascara and toy gun. We awarded 20 points to notifications with a product name, even if the name remained generic such as ‘protective mask’ or ‘toy light.’ A name represents the basic detail needed for an effective recall. That is why we gave 20 points for a product name – and 0 if only the product category was listed.

- BRAND NAME (20 points). Brands represent the second, crucial indicator to allow easy location on online marketplaces. For this reason, we counted the inclusion of a brand name for 20 points.

- TYPE/NUMBER OF MODEL (10 points) Beyond a product name and brand, the model number represents a third important identifier. It helps pinpoint the specific production faulty and dangerous batches. Without the model name or number, products often remain possible to locate, explaining why we made their presence worth 10, not 20, points.

- WEIGHT, SIZE, COLOUR, SERIAL NUMBER (10 points). These additional descriptive details increase the opportunity for detection and effective recall. Points were awarded if a minimum of two additional pieces of the information featured on the notification.

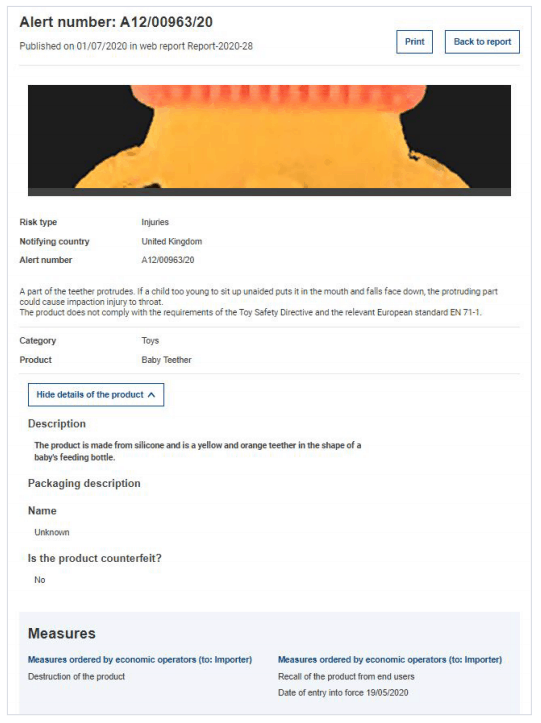

- IMAGE (10 points). The presence of at least one good quality photo is essential. Although all of the notifications contained a photo, their quality varied. In cases where we judged the image too fuzzy to assist in its location, we gave 0 points.

- SAFETY ISSUE (10 points). Details of product risks and safety issues, while useful for consumers, do not help locate and remove from sale or recall. That’s why they did not merit additional weight in our grading.

- REQUIRED ACTION (10 points) This category concerned legally required courses of action. While clear identification of dangerous products represents a crucial first step, clear actions on how to respond are critical. Without them, the manufacturer, distributor, merchant, and consumer are left to guess what actions to take. This could include safety warnings, a recall from end-users, a sales ban or the rejection of the product at the border.

- RECALL INFORMATION (10 points) A final 10 points depended on the clarity of enforcement instructions. While we did not expect detailed recall information on the notification, consumers should receive a link to a company website and instructions on what to do: send the product back to the manufacturer or distributor or throw it away.

For the sake of consistency and clarity, we assign either no or full marks for each category rather than partial grades.

2.2 Examples

This children’s product (RAPEX 2020a) represents a poor quality notification. It contains no product name, no brand, no model number nor barcode, and no recall information despite a recall from users being ordered.

- PRODUCT NAME – 0

- BRAND NAME – 0

- MODEL NAME/NUMBER – 0

- OTHER INFORMATION (WEIGHT, SIZE, COLOUR, SERIAL NUMBER) – 0

- IMAGE – 10

- SAFETY ISSUE – 10

- REQUIRED ACTION – 10

- RECALL INFORMATION – 0

TOTAL 30 points

Figure 1: Inadequate Safety Gate alert

Alert notification for a silicone baby teether, July 10 (RAPEX 2020a)

In contrast, the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 (RAPEX 2016) rates as a good example, with a clear brand, model number, a clear picture, and a clear description of the product safety risk – burns. The required action is also clear – the manufacturer Samsung is recalling the item. The only detail missing is a link to Samsung’s company recall page or point of contact.

- PRODUCT NAME – 20

- BRAND NAME – 20

- MODEL NAME/NUMBER – 10

- OTHER INFORMATION (WEIGHT, SIZE, COLOUR, SERIAL NUMBER) – 10

- IMAGE – 10

- SAFETY ISSUE – 10

- REQUIRED ACTION – 10

- RECALL INFORMATION – 0

TOTAL 90 points

Figure 2: Exemplary Safety Gate alert

Alert notification for the Samsung Galaxy Note 7, September 23 (RAPEX 2016)

Although any scoring methodology remains, to a certain extent, subjective, we note that any changes in either the criteria or weighting would have changed the results or its conclusions. Poor notifications would remain poor. Our grading system allowed a consistent review of notifications and it includes the major data points considered important under Safety Gate guidelines.

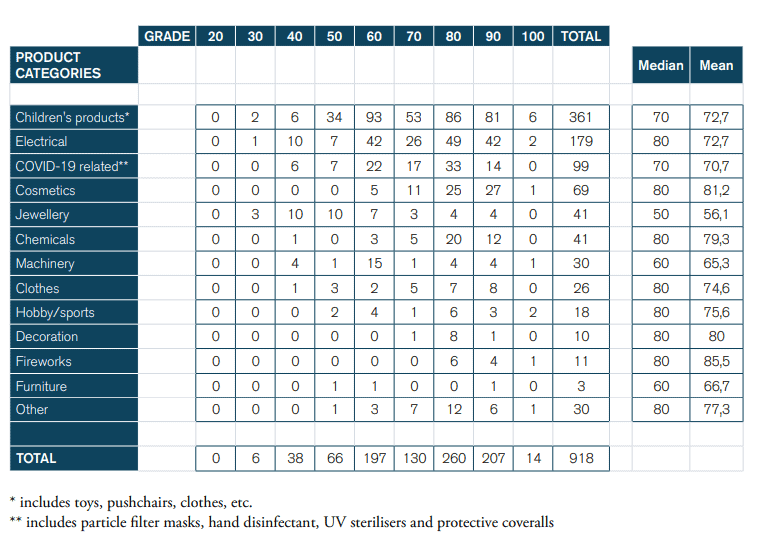

3. Results

Of all notifications, 98.5% omitted at least one key criteria required for identification.

One in five notifications (207) received a grade of 90, and a small handful (14) received a perfect 100. Some 94% of the notifications included at least one measure ordered or taken to deal with the defective product. All of the alerts included descriptions of the safety issues and over 98% included at least one image. The average score was 72.8.

Yet we found notifications received grades as low as 30, and a third (307) scored 60 or under. Many lacked product and brand names, serial numbers, detailed descriptions which are all needed in order to effectively identify and locate defective products causing harm to the public.

Cumulative grades are tabulated in Annex 1. Individual grades are listed in Annex 2.

Safety Gate’s challenges look structural. Under the European framework, national authorities are responsible for producing notifications. The European Commission depends on the information it receives from national authorities, though it asks for additional details when insufficient data are submitted before validating alerts. By law, though, the Commission is required to publish available information as early as possible on Safety Gate, with the understanding that it can be updated later. Many incomplete notifications never seem to be updated.

The decentralised approach of data submission by national European authorities poses challenges. While one could argue that local authorities are best placed to understand local conditions, this approach results in different and varying levels of quality. U.S. and Australian systems allow a single agency to direct the work of both notifying and enforcing the recalls.

Australian Consumer Law contains minimum statutory notification requirements for manufacturers, importers, brick and mortar retailers, and online sellers undertaking recalls. The country’s Product Safety Australia website has an online form that guides suppliers to describe product defects and hazards. Before publication on Product Safety Australia (ACCC 2020a), the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) assesses each notification. Consumers are provided with clear and concise warnings written in simple language. The ACCC is strict about the need for effective warnings in recall notices. “We talk to companies about not publishing unclear warnings,” says Neville Matthew, the ACCC’s General Manager, Risk Management and Policy. “Complicated, technical language, jargon or ‘weasel words’ can weaken the consumer warning” (Matthew 2020).

Consider again the case of the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 phone. Although the UK’s detailed notice outlines the dangers of overheating and explosion (RAPEX 2016), it lacks clear instructions compared to the U.S. notification. The U.S. Galaxy Note notification (US CPSC 2016) is written in a clear, declarative language. It provides the colours of the dangerous model – “black onyx, blue coral, gold platinum and silver titanium with a matching stylus” – and details the potential danger to consumers. It orders consumers to immediately stop using the device and provides links and addresses for consumers to contact suppliers and claim a refund.

Key ingredients to a successful recall notification include clarity in the explanation of the defects and hazards, a sharp image of the product, and serial number and/or date range of production, according to Australian regulators. Products with serial numbers or other tracking ensure effective identification. Suppliers are encouraged to include phone, website, and email, making it easy for consumers to take action.

Many European notifications lack these details and instructions. We identified five major shortcomings in Safety Gate notifications.

3.1. Missing and Incomplete Information

Almost a fifth of Safety Gate notifications lacked a product name, such as this notification of dangerous children’s clothing (RAPEX 2020d). A fifth missed a model name or number and 26% had no brand name. See the following examples:

- An anonymous electric charger came without a brand name, product name, or barcode (RAPEX 2020r). It is difficult to distinguish it from dozens of similar products found with a few clicks of a keyboard.

- This dangerous light purple yoga mat lacked a brand name and contained only a generic identification: “a small black stopper on the carrier lace containing short-chain chlorinated paraffin” (RAPEX 2020v).

- A self-balancing scooter (2020o) failed to provide a brand name and cannot be easily identified among dozens of other available scooters.

- This metal chain necklace (2020j) contained high levels of cadmium that can cause damage to the kidneys or bones. A photo was provided with serial numbers, but without a brand or product name it is unclear what the numbers relate to (ie. barcode, batch number or model number). This makes tracking down the necklace difficult.

Many notifications included, at best, basic product information. Only 40% of those studied included additional details such as colour, size, weight, or batch number to help pinpoint unsafe products.

COVID-19 shines a glaring light on these inadequacies. Pandemic-related products such as masks and disinfectants began appearing in late April 2020, a month after most of the EU entered lockdown. Many alerts of filter masks omitted key details and were classified in the category “For information”.

Admittedly, most mask notifications were published as notifications for information, with the caveat that it is better to provide some information about dangerous products rather than no information. While understandable, these notifications for information risk for unsafe masks confusion. Safe masks look the same as unsafe ones.

Even after notifications for information are removed from the calculations, problems remain. More than a third of COVID-19 products received grades of 60 or under within the serious risk category.

3.2. Poor Images

Almost all (98.2%) of the Safety Gate notifications reviewed in our research contained at least one clear image. This is good news.

The bad news is that in spite of the effort taken by the Commission to ensure quality pictures, some photos could be improved. Seventeen notifications graded 0/10 in images, often because they were too blurry or generic to allow certain identification. The majority, 10 out of 17, concern COVID-19 related products: masks, protective coveralls, and UV steriliser lamps. These deficiencies seem to stem from the image quality on the vendor platform.

Figure 3: Blurry photo

Image of a protective coverall from a Safety Gate alert notification, June 12th (RAPEX 2020n)

Figure 4: Blurry photo

Image of a LED UV steriliser lamp from a Safety Gate alert notification, July 10 (RAPEX 2020i)

Figure 5: Blurry photo

Image of a Fishing toy for children from a Safety Gate alert notification, January 10 (RAPEX 2020g)

3.3. Jewellery versus Firework

Safety Gate notifications for certain products are better than for other types of products.

Jewellery notifications stand out for their poor quality. More than half of the 41 jewellery products graded 50 or less out of 100. Jewellery often comes with limited packaging and identifying markers. Many jewellery products notified come from small companies in small quantities from outside the EU, which limits their traceability and their identification. Other products receiving poor grades include various machine tools such as metal grinders and lawn mowers. Two-thirds of these notifications received grades 60 or below.

In contrast, alerts for fireworks are of good quality: all 11 dangerous fireworks notices scored above 80. Cosmetics also receive high grades, with an average of 81.2. The explanation seems to be that these products are subject to extensive regulations.

Grades for Safety Gate alerts by product category

Source: Author’s calculations

3.4. Inconsistent National Alerts

We could not draw any definitive conclusion on the geographic distribution of the results. Good quality notifications came from all over the continent – alongside poor quality ones. Often, the same country publishes both good and poor quality alerts.

- Germany published both this necklace notice lacking model, brand, and product names (RAPEX 2020k), and this earring notice containing many details including a link to a recall page (RAPEX 2020e).

- Lithuania published this alert for fuel additive (RAPEX 2020h) with several descriptive details and product/brand names, while another chemical product alert – windscreen cleaning fluid (RAPEX 2020u) – lacked some basic information and provided no recall information despite a recall being ordered.

The lack of consistency stems from several factors. Few regulatory requirements often exist for dangerous low-priced products. The quality of product information depends on the distribution channel and Europe’s decentralised approach of national regulators produces inconsistency despite Commission efforts. One department in a member state may be responsible for tracking toy safety, while another is responsible for car products. National regulatory bodies need additional resources and should be obliged to become more consistent in their notification of dangerous products.

3.5. Vague Product Recalls

Recall information remains a final, crucial concern. While unsafe products may still be located without brand names, product details, and images, authorities are in control of requesting the correct recall action. Should a product be returned to the manufacturer or seller? Should it be destroyed? Or should consumers just pay attention to the product while using it? This recommendation is fundamental. Lack of sufficient information cannot be attributed to vendors or platforms alone.

Not all dangerous products listed on Safety Gate are recalled. Some are just banned from being imported and others have warning risks printed on them. In either case, consumers need to know who to contact after discovering a dangerous product and most RAPEX alert notifications lack contact information or clear instructions for consumers to receive advice and compensation.

Of the 918 graded notifications, only 58 (6.3%) include working links to the pages of their manufacturer such as this bicycle in weekly report 28 (RAPEX 2020b). Several alerts list the product name and brand but do not include a link to the recall page. Fashion retailer Primark, for example, recalled these unsafe shoes and this bracelet, but only the shoes contain a link to Primark’s recall page (RAPEX 2020c; RAPEX 2020p).

Some recall links did not work, leading the viewer to an ERROR 404 page. This is the case with a toy slime kit notified by Polish authorities in February 2020 (RAPEX 2020q).

4. Policy Recommendations

Widespread support exists to improve Safety Gate. The European Commission’s publication of detailed 2019 guidelines represented an important step demonstrating the need for improvement. In addition to these updated guidelines, additional efforts are required to build an effective, consumer, and business-friendly recall notification system. This report is designed to help.

European policymakers are engaged in a vigorous debate about how to share responsibilities in the digital world. In July 2020, the new Platform to Business regulation came into effect, requiring e-commerce platforms to increase transparency about their rankings and terms and conditions for merchants (European Union 2019c). The 2019 Goods Package requires non-European manufacturers and sellers to name a “responsible” European entity to assume liability for safety issues (European Union 2019b), starting on July 1, 2021. These initiatives address some of the challenges, and we should allow them time to be fully implemented and enforced.

The upcoming proposal for a revised General Product Safety Directive will grapple with the issue of dangerous products (European Commission 2020). A proposal is expected in the second quarter of 2021. Everyone agrees that dangerous products should be removed from sale and recalled. The policy debate centres around the proper repartition of roles, responsibilities, and legal liability between manufacturers, distributors, marketplaces, brick and mortar retailers and regulators. In its consultation document, the Commission looks at a variety of options, ranging from option one of “improved implementation and enforcement, without revision” to option two of a “targeted revision,” option three of a “full revision” or option four of a “new legal instrument” (European Commission 2020).

Each link of the product safety chain needs to step up and improve, within the realm of what they control. Marketplaces, as agreed in the Product Safety Pledge, must increase their ability to remove dangerous products from sale. Once identified, the platforms and brick and mortar stores need to keep the products from popping back up. Consumers and other interest groups should participate in the discussion and in identifying unsafe products, rather than acting outside the system.

Regulators must improve their notifications. A notification system containing sufficient information on dangerous products will allow marketplaces and brick and mortar stores to speed takedowns. Europe needs a strong, centralised product safety system: this means giving the European Commission additional powers to instruct and insist on timely, effective recall notices.

This report presents what we consider non-controversial constructive suggestions for improvement. Any of the options of General Product Safety Directive reform, from no revision to total revision, could incorporate these improvements. Our recommendations centre on ensuring consistent and harmonised details, allowing efficient detection and recall of unsafe products. These include these basic pieces of information:

- Product Description and description: model and batch number

- High-quality pictures

- Clear safety risk information

- The full address and contact details of the producer and legal representative, if legally allowed.

Together, if implemented, the changes will allow improvement in the performance of all the actors in the retail chain, manufacturers, merchants, importers, distributors, and consumers.

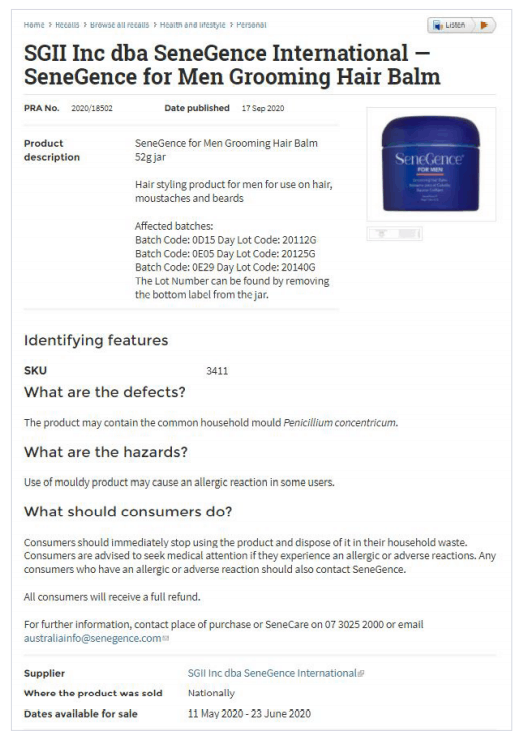

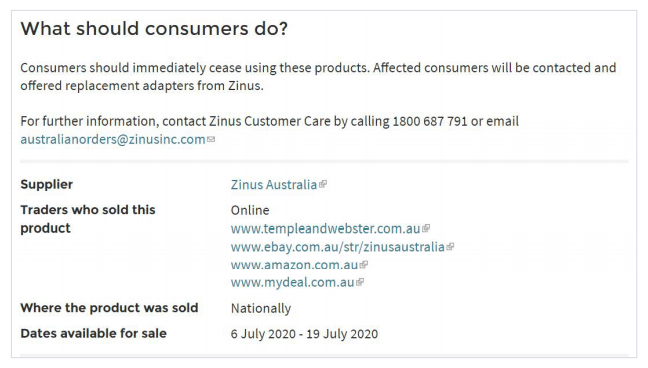

1. Prioritise consumers

The 2021 Safety Gate modernisation provides significant progress in creating a consumer friendly interface. Additional improvements still should be envisioned. Australian notifications provide a strong model. To take an example, we looked at an alert for a cosmetic product from September 2020:

Figure 6: Australian alert

Alert notification for a hair product, September 17 (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2020b)

Key features include:

- Clear questions are posed.

- Answers to “What should consumers do?” are detailed and provide clear actions for consumers to follow, including seeking medical advice if necessary or requesting a refund.

- Dates of sale help pinpoint when problematic products could have been purchased by consumers.

- Contact details of suppliers and company recall pages are provided.

Some notifications such as this dangerous USB charger list online marketplaces selling the item.

Figure 7: Australian alert

Excerpt from an alert notification for a USB charger, September 23, (ACCC 2020c)

2. Insist on precise recall information

Unlike American or Australian notifications, RAPEX alerts give little guidance to consumers about next steps to take. Many alerts for dangerous products lack crucial information such as links to a company recall page. Even in cases when a recall has not been ordered and other measures have been used instead to deal with a dangerous product, information should still be provided about what a consumer should do if they recognise a product that they own on Safety Gate.

Suggestion: For effective recalls, information about suppliers and manufacturers should be provided, and the law changed to limit the confidentiality offered to manufacturers and distributors. Contact details and links to relevant web pages should be included in all alerts.

3. Set a common standard for product details and images

Many European notifications lack details about the model numbers, serial numbers, colour, shape, size, and weight of the product and its packaging. Some of these details may well be discernible from the images of the product but these do not provide enough detail alone, particularly in cases of poor quality images.

Suggestion: Ensure all descriptions of products are detailed and complete.

4. Improve images

Some alerts contain poor and blurry images, making the unsafe product difficult to identify. Others, like those of COVID-protecting masks and many electric chargers, lack details, making them indistinguishable from dozens of similar products.

The European Commission has made efforts to tackle this problem. Regulators are provided with an infographic on how to provide quality pictures. Yet national authorities continue to take different approaches to photos. Some show packaging and the product. Others select only the part of the product which is not in compliance.

Suggestion: the Commission has provided national authorities with clear guidance to ensure good product descriptions and strong quality images. Yet many regulators remain under resourced and struggle to keep up with these requirements. Their funding must be increased.

This report highlights important weaknesses in Europe’s product safety regime that require corrective action. All parties can help. Manufacturers and distributors need to provide clear markings that retailers and consumers can identify. Regulators then will be able to provide sufficient details for unsafe products to be located and recalled. Europe needs well-documented unsafe product notifications. All reforms to the continent’s product safety regime should include requirements to produce them.

5. References

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission – ACCC (2020a). Product Safety Australia. Available at: https://www.productsafety.gov.au/

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission – ACCC (2020b). SGII Inc dba SeneGence International — SeneGence for Men Grooming Hair Balm, 2020/18502, Product Safety Australia, September 17. Available at: https://www.productsafety.gov.au/recall/sgii-inc-dba-senegence-international-senegence-for-men-grooming-hair-balm

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission – ACCC (2020c). Zinus Australia — USB Charger Adapter for Zinus Suzanne Bed, 2020/18461, Product Safety Australia, September 23. Available at: https://www.productsafety.gov.au/recall/zinus-australia-usb-charger-adapter-for-zinus-suzanne-bed

Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs – BEUC (2020a), Product Safety, available at: https://www.beuc.eu/safety/product-safety

Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs – BEUC (2020b), “Two-thirds of 250 products bought from online marketplaces fail safety tests, consumer groups find”, February 24, Available at: https://www.beuc.eu/publications/two-thirds-250-products-bought-online-marketplaces-fail-safety-tests-consumer-groups/html

European Commission (2018), Product Safety Pledge: Voluntary commitment of online marketplaces with respect to the safety of non-food consumer products sold online by third party sellers, Brussels, June 25. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/voluntary_commitment_document_4signatures3-web.pdf

European Commission (2019a). First progress report on the implementation of the Product Safety Pledge, Brussels, July 24. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/product_safety_pledge_-_1st_progress_report.pdf

European Commission (2019b), Survey on Consumer Behaviour and Product Recall Effectiveness: Final Report, Brussels, April. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumers_safety/safety_products/rapex/alerts/repository/tips/Product.Recall.pdf

European Commission (2020), Inception Impact Assessment, Brussels, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12466-Review-of-the-general-product-safety-directive

European Commission (2021a), Facing the unexpected together: Safety Gate 2020 results, Brussels, March 5, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate/#/screen/pages/reports

European Commission (2021b), Product Safety Business Alert Gateway. Available at: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/gpsd/

European Commission (2021c), “Protecting European consumers: Safety Gate efficiently helps take dangerous COVID-19 products off the market”, Press Corner, Brussels, March 2, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_814

European Commission (2021d). Safety Gate: The rapid alert system for dangerous non-food products. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumers_safety/safety_products/rapex/alerts/repository/content/pages/rapex/index_en.htm

European Union (2002a), Directive 2001/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 December 2001 on general product safety, OJ L 11, 15.1.2002. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32001L0095

European Union (2002b), Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety, OJ L 31, 1.2.2002. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32002R0178

European Union (2008), Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 July 2008 setting out the requirements for accreditation and market surveillance relating to the marketing of products and repealing Regulation (EEC), OJ L 218, 13.8.2008. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32008R0765

European Union (2019a), Commission Implementing Decision (EU) No 2019/417 of 8 November 2018 laying down guidelines for the management of the European Union Rapid Information System ‘RAPEX’ established under Article 12 of Directive 2001/95/EC on general product safety and its notification system (notified under document C (2018) 7334) OJ L 73, 15.3.2019. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32019D0417

European Council (2019b), Regulation (EU) No 2017/0353 of the European Parliament and of the Council on market surveillance and compliance of products and amending Directive 2004/42/EC and Regulations (EC) No 765/2008 and (EU) No 305/2011, PE 45 2019 REV 1, 24.05.2019. Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-45-2019-INIT/en/pdf

European Union (2019c), Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services, OJ L 186, 11.7.2019. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1150/oj

Fauré, M. G. (2000), “Product Liability and Product Safety in Europe: Harmonization or Differentiation” in KYKLOS, Vol. 53 – 2000 – Fasc. 4, pp. 467-508

Fairgrieve D. & Howells G. (2006), “General Product Safety: a Revolution through Reform?” in The Modern Law Review, Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 59-69

Fairgrieve D., Howells G. & Pilgerstorfer, M. (2013), “The Product Liability Directive: Time to get Soft?” in Journal of European Tort Law, vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 1-33

Fairgrieve D. et al (2016), “Product Liability Directive”, in P. Machnikowski (Ed.), European Product Liability: An Analysis of the State of the Art in the Era of New Technologies (pp. 17-108). Intersentia. Principles of European Tort Law

Fairgrieve D. et al (2020), “Products in a Pandemic: Liability for Medical Products and the Fight against COVID-19” in European Journal of Risk Regulation, vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 1-53

Jourová, V. (2018), “Speech at the International Product Safety Week 2018”, Brussels, November 12. Available at: https://audiovisual.ec.europa.eu/en/video/I-163176

Matthew, N. (2020), Personal communication, interviewed by William Echikson, 14 December

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – OECD (2019), “Global awareness campaign on product recalls”, available at: http://www.oecd.org/sti/consumer/product-recalls/

Pigłowski, M. (2018), Notifications of Dangerous Products from European Union Countries in the RAPEX as an e-service, European Journal of Service Management, vol. 2, No. 26, pp. 175–183.

RAPEX (2005), Jacket, 0307/05, European Commission, Brussels, June 17. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/-1379

RAPEX (2010), Toy, 0905/10, European Commission, Brussels, June 11. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/-17182

RAPEX (2016), Samsung phone, A11/0087/16, European Commision, Brussels, September 23. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/226971

RAPEX (2020a), Baby teether, A12/00963/20, European Commission, Brussels, July 1. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001582

RAPEX (2020b), Bicycle, A12/00988/20, European Commission, Brussels, July 10. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001568

RAPEX (2020c), Bracelet, A12/00030/20, European Commission, Brussels, January 17. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000435

RAPEX (2020d), Children’s Clothing set, A12/00053/19, European Commission, Brussels, January 3. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000195

RAPEX (2020e), Earrings, A12/00737/20, European Commission, Brussels, May 22. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001221

RAPEX (2020f), Fireworks, A12/00866/20, European Commission, Brussels, June 12. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001405

RAPEX (2020g), Fishing Toy, A12/00075/19, European Commission, Brussels, January 10. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000274

RAPEX (2020h), Fuel additive, A12/00770/20, European Commission, Brussels, May 29th. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001293

RAPEX (2020i), LED UV steriliser lamp, A12/00968/20, European Commission, Brussels, July 10. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001524

RAPEX (2020j), Necklace, A12/00100/20, European Commission, Brussels, January 24. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000459

RAPEX (2020k), Necklace, A12/00432/20, European Commission, Brussels, March 20. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000821

RAPEX (2020l), Particle Filter Mask, A12/00978/20, European Commission, Brussels, July. Available at:https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001601

RAPEX (2020m) Piercing jewellery, A12/00098/20, European Commission, Brussels, January 24. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000316

RAPEX (2020n), Protective coverall, A12/00863/20, European Commission, Brussels, June 12. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001432

RAPEX (2020o), Self-balancing scooter, A11/00005/20, European Commission, Brussels, January 17. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000222

RAPEX (2020p), Shoes, A12/00453/20, European Commission, Brussels, March 27. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000877

RAPEX (2020q), Toy slime, A12/00187/20, European Commission, Brussels, February 14. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000550

RAPEX (2020r), USB Charger, A12/00060/19, European Commission, Brussels, January 3, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000212

RAPEX (2020s), USB charger, A12/00754/20, European Commission, Brussels, May 22. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001271

RAPEX (2020t) USB charger, A12/01133/20, European Commission, Brussels, August 14. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10001655

RAPEX (2020u), Windscreen washer fluid, A12/00434/20, European Commission, Brussels, March 20. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/safety-gate-alerts/screen/webReport/alertDetail/10000862

RAPEX (2020v), Yoga mat, A12/00116/20, European Commission, Brussels, Jan 31. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumers_safety/safety_products/rapex/alerts/?event=viewProduct&reference=A12/00116/20&lng=en

Reynders, D. (2020), “Virtual meeting between two new product safety pledge signatories and Didier Reynders, European Commissioner”, Brussels, November 9. Available at: https://audiovisual.ec.europa.eu/en/video/I-198187

Safe non-food consumer products in the EU and China – SPEAC (2021), Homepage, available at: https://speac-project.eu/

Sterrett, L. (2014), “Product Liability: Advancements in European Union Product Liability Law and a Comparison between the EU and U.S. Regime” in Michigan State University International Law Review, 23, pp. 885-924

Ullrich, C. (2019), “New Approach meets new economy: Enforcing EU product safety in e-commerce” in Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 558-584

United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (2016). “Samsung Expands Recall of Galaxy Note7 Smartphones Based on Additional Incidents with Replacement Phones; Serious Fire and Burn Hazards”, Product Recalls, October 13. Available at:

United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (2020). Product Recalls. Available at: https://www.cpsc.gov/Recalls

Wijnhoven, S.W.P., Janssen, P.J.C.M., & Schuur, A.G. (2013) “Definition of serious risk within RAPEX notifications”, Dutch National Institute for Public Health and Environment, Report 090013001/2013, Bilthoven, pp. 1-42