Collective Action in the Netherlands: Why It Matters for the Transposition of the Product Liability Directive

Published By: Oscar Guinea Dyuti Pandya Vanika Sharma

Subjects: European Union

Summary

This policy brief explores the implications of the Netherlands’ transposition of the new EU Product Liability Directive (PLD), focusing on its interaction with the Dutch collective action system. As one of the first EU countries to implement PLD and a key hub for mass litigation, the Netherlands offers a compelling case study.

Features such as low claim thresholds, opt-out mechanisms, flexible settlements, limited cost-shifting, and the ease of creating litigation-backed entities make the Netherlands particularly attractive for mass claims, reinforcing its reputation as a “litigation magnet.” The new PLD simplifies liability claims, broadens the definition of “product” to include software, digital files, and related services, lowers evidentiary thresholds, extends liability to third-party actions such as cyberattacks, and includes post-market defects. These provisions, combined with the Netherlands’ collective redress regime, are expected to drive a rise in mass litigation.

This rise poses particular economic risks for the Netherlands, one of the EU’s most digitised economies. Ranked sixth in digital adoption by Eurostat’s Digital Intensity Index, Dutch firms – especially in finance, insurance, ICT, and manufacturing – may also face growing exposure to collective actions under the PLD, which extends liability across the entire value chain. These sectors account for 27 percent of the value added in the Dutch market economy and are widely recognised as key drivers of economic growth. Increased legal uncertainty may also reduce the Netherlands’ attractiveness to multinational corporations, threatening levels of foreign direct investment and employment, both essential pillars of the Dutch economy.

Growing mass litigation may also hinder innovation by redirecting R&D resources toward legal risk management. This is particularly concerning for the Netherlands, one of the EU’s top R&D investors. Drawing on US evidence, large-scale litigation can significantly erode market capitalisation, and based on our estimates, the cumulative loss in value for 31 Dutch companies featured in the EU R&D Scoreboard could reach €5.5 billion under the high-growth scenario.

Such declines could impact household wealth, as Dutch households save approximately 14.6 percent of their gross disposable income, of which 20 percent is invested in equity. Pension funds, which also play a central role in Dutch long-term savings, can also hold significant stakes in publicly traded Dutch companies. As a result, the effects of collective actions on the market value of Dutch companies extend beyond corporate balance sheets, posing potential negative consequences for Dutch savers, as well as current and future pensioners.

This report was commissioned by the European Justice Forum, a coalition of businesses, individuals and organisations that are working to build fair, balanced, transparent and efficient civil justice laws and systems for both consumers and businesses in Europe.

1. Introduction

The Netherlands is preparing to transpose the new EU Product Liability Directive (PLD) (Directive (EU) 2024/2853) into national law. The transposition of the EU PLD will primarily involve amendments to Books 6 and 7 of the Dutch Civil Code (BW), as well as the Transitional Act of the new Civil Code. The Dutch government has published a draft bill to implement these changes and has opened a public consultation on the proposed amendments.

The country provides a highly relevant case study, as the first EU country to transpose the EU PLD and one of the key centres for mass litigation in Europe. This paper aims to offer evidence that helps us understand the impact of the EU PLD implementation in the Netherlands, particularly if the implementation of the Directive results in an increasing number of collective actions. To achieve this, the paper outlines the following steps:

- Chapter 2 explores the interaction between the PLD and collective action in the Netherlands. It explains why the legal and institutional features that make mass litigation more prevalent in the Netherlands, compared to other EU countries, combined with the new avenues for mass litigation introduced by the EU PLD, could lead to an increase in such litigation.

- Chapter 3 examines mass litigation cases in the Netherlands, focusing on the costs associated with a system that provides consumer redress through the courts.

- Chapter 4 introduces an updated database of mass litigation cases in the Netherlands and identifies the sectors most affected by this form of litigation. The chapter also evaluates which sectors are likely to be further impacted by the introduction of the PLD, highlighting the economic significance of these sectors for the Netherlands.

- Chapter 5 presents evidence suggesting that the Netherlands has become a litigation magnet, emphasising the role of US law firms and funders. The chapter also discusses how the introduction of the PLD could exacerbate this situation.

- Chapter 6 assesses the impact of increased mass litigation resulting from the implementation of the PLD on the Dutch economy, particularly its most innovative sectors and foreign direct investment. The chapter also explores how a decline in the valuation of Dutch innovative companies due to mass litigation could affect Dutch citizens, especially through a reduction in the value of their investments.

- Chapter 7 summarises the main findings and presents the key data points drawn from the analysis, which can inform the public consultation on the transposition of the PLD in the Netherlands.

2. The Dutch Collective Action System and the Impact of the EU PLD on Mass Litigation in the Netherlands

2.1 Understanding the Dutch Collective Action System

Under Dutch law, there are three distinct mechanisms for collective redress:[1] (1) The Dutch Collective Settlement for Mass Damages Act (WCAM); (2) The Dutch Collective Actions for Mass Damages Act (WAMCA); and (3) actions on the basis of power of attorney or transfer or assignment of claims to a special purpose vehicle.[2]

Of particular importance are WCAM and WAMCA. WCAM, introduced in 2005, allows for the global settlement of collective proceedings. Notable examples include the Shell Petroleum, Vedior, and Converium settlements.[3] In 2020, WAMCA was enacted in response to the EU Representative Actions Directive (RAD). It enables ad hoc entities to seek financial compensation for legal breaches. WAMCA complements WCAM by introducing a comprehensive regime for both injunctive relief and monetary compensation. Under WAMCA, qualified entities from any EU member state can now bring collective actions before Dutch courts, significantly expanding the jurisdictional reach of the Dutch legal system.

The Dutch system has certain characteristics which contributes to it being a preferred destination for mass litigation in the EU. Unlike other jurisdictions within the EU, the threshold of initiating a collective action is substantially lower in Netherlands. This procedural flexibility is enabled by an opt-out system which automatically includes individuals with similar claims in the proceedings, naturally leading to a larger pool of beneficiaries entitled to claim compensation if the court rules in their favour.[4]

In addition, Dutch law upholds the principle of freedom of contract, allowing parties to settle disputes as they see fit, provided such agreements do not contravene public policy.[5] This contractual flexibility increases the likelihood that class actions will ultimately be settled. This feature introduces two significant risks. The first is the danger of sweetheart settlements, where class counsel may compromise the interests of class members by settling meritorious claims for far less than they are worth, effectively “selling out” the class in exchange for legal fees or a faster resolution.[6] The second is the problem of blackmail settlements, in which defendants feel pressured to settle for more than the actual value of the claims due to the threat of costly and risky litigation.[7]

There are other characteristics that make the Dutch legal system more appealing to mass litigation. First, even though the Netherlands applies the loser pays rule, which makes the losing party pay the court costs and legal fees,[8] it also has minimal cost-shifting risks. If the defendant wins, they are awarded only a small fraction of the actual expenses incurred.[9] Second, under the Dutch law, ad hoc qualified entities can be set up at short notice to bring claims, which are often supported by litigation funders.[10] And thirdly, collective actions are permitted across all areas of civil law.

2.2 Combining the Dutch Collective Action with the Product Liability Directive

Every legal rule comes with specific economic consequences linked to its implementation. The EU’s revised PLD serves as a prime example. By simplifying the process of bringing liability claims to court, including through mass litigation, the PLD also significantly alters the burden of proof, particularly in cases involving complex technology. Moreover, the Directive broadens the scope for claimants to pursue liability across time, products and the supply chain.

These features interact with the Dutch legal system where collective actions are allowed across all areas of law, raising concerns that the transposition of the PLD could lead to an increase in the number of collective actions. This section presents five crucial factors in the transposition of the EU PLD that may contribute to more mass litigation.

- Uncertainty in assessing product defects and the expanded definition of “product”;

- Lowered evidentiary burden and facilitated proof process on claimant side;

- Broader definition of liable parties;

- Expansion of liability to include defects caused by third-party actions, such as cyberattacks; and

- Extension of liability for defects that emerge after the product’s release.

2.2.1 Uncertainty in Assessing Product Defects and the Expanded Definition of “Product”

A product is considered defective if it does not provide the safety that the general public is entitled to expect. Whether this objective standard is met must be assessed on the basis of the presentation of the product and the reasonably foreseeable use and the time at which the product was put into circulation.[11] However, the core standard of “what the public is entitled to expect” remains vague and context-dependent. This creates legal uncertainty, as producers might not be clearly able to assess whether their products meet the safety threshold. Multiple factors will have to be considered, making it easier for consumers to claim that some aspect of a product fell short. In other words, the more broadly defined the public expectation, the easier it becomes to argue collective harm.

The new PLD expands liability to new products. Firstly, digital technologies, including software and digital manufacturing files, are now explicitly defined as products (see Recitals 13 and 16). The term “software” is broadly interpreted to encompass operating systems, firmware, computer programs, applications, and AI systems, regardless of delivery or use methods. Secondly, and in line with the Directive, Dutch law will also classify digital manufacturing files as products, digital templates used to produce tangible objects through tools like 3D printers (Article 4(2); see Recital 16). Thirdly, it also expands to “associated services” referred to as digital services that are integrated into or interconnected with a product such that the product cannot perform one or more of its functions without the service (Article 4(3)).

This expansion of the product definition, broadening potential liability and increasing the range of claims under the product liability regime, also increases the risk exposure for players involved in the product supply chain. For instance, in the case of software, courts may have to determine whether the software was defective, when the defect occurred, and whether the cause lies in original code, an update, or a failure to monitor system behaviour. This blurs the line between initial manufacturing duties and ongoing obligations, raising the question of whether manufacturers must monitor irregular data patterns and act pre-emptively, especially in the case of products belonging to the Internet of Things (IoT).[12]

Legal uncertainty is further amplified by a regulatory blind spot regarding open-source software (OSS). While the Directive rightly excludes OSS supplied outside of commercial activity to avoid hampering innovation (Recital 14), it does apply to OSS provided in exchange for payment or for personal data which is not solely used to improve functionality. It also applies when non-commercial OSS is later integrated into a commercial product and causes damage, in which case, the manufacturer, not the OSS developer, bears liability (Recital 15). Given that OSS development is decentralised, layered, and often anonymous, manufacturers may not have a clear way to verify or trace bugs or defects. This lack of traceability could encourage claimants to file speculative claims more readily, particularly where there is confusion over who is responsible.

2.2.2 Lowered Evidentiary Burden and Facilitated Proof

While the European Consumer Organisation (BEUC) argues that new technologies make it harder for consumers to prove damage and causation,[13] in practice, national courts appear familiar with these challenges. In civil law jurisdictions especially, courts recognise the information asymmetry between consumers and producers. To address complex product liability claims, they often appoint technical experts to investigate defects on behalf of the claimant who often request technical disclosures from the producer. This practice creates a de facto burden of proof, requiring producers to demonstrate that their products were not defective.[14] Under the revised PLD, the Dutch courts may adopt a similar approach. As a result, industry actors already on the defensive in such cases could face even greater challenges, regardless of the formal legal standard.

The harmonised right to evidence disclosure between parties enables claimants to access relevant documentation from defendants, addressing the information asymmetry often faced when challenging large manufacturers. While addressing information asymmetries in favour of individual claimants may be justifiable, primarily given their relative disadvantage in accessing legal, technical, or market data, such justification weakens in the context of collective actions supported by Third-Party Litigation Funding (TPLF). In these cases, the collective’s informational disadvantage can be often offset by the resources, expertise, and strategic coordination brought by professional funders and legal teams.

The PLD also introduces rebuttable presumptions about defects or causation in certain cases, such as failure to disclose evidence, non-compliance with safety requirements, or clear product malfunctions.[15] These provisions ease the burden of proof and support collective actions. Within the Dutch WAMCA collective redress regime, these presumptions may significantly increase the volume of complex product liability claims by lowering the threshold for bringing group actions.

2.2.3 Broader Scope of Liable Parties

As pointed earlier, the PLD complicates responsibility by allowing the injured party to hold both the manufacturer of the defective end product and the manufacturer of a defective component liable.[16] Importers may also be considered “producers” under the Directive.[17] If the product’s producer cannot be identified, any supplier is deemed the producer, though they may be relieved of liability by disclosing the producer’s identity within a reasonable timeframe.[18] This broadens the scope for claims, particularly in technology products with multiple suppliers or software developers. In cases where embedded or connected software (e.g. smart appliances, medical devices, cars) causes defects, consumers may file claims against the manufacturer, importer, producer, or supplier, depending on the circumstances, pursuing liability across the supply chain.

This is particularly important for the Netherlands. As described in Chapter 4, Dutch SMEs employ digital technologies more intensively than other EU SMEs. Some of these Dutch SMEs are not only users but also producers of digital technologies, such as software. As a result, it is entirely plausible that they could become caught up as defendants in a mass litigation case.

2.2.4 Data Protection and Product Liability

Another potentially problematic provision is Article 13(1) of the new Directive 2024[19]: While Article 13(2) concedes to Member States (“Without prejudice to national law concerning rights of contribution or recourse”) to do the opposite, Article 13(1) states that “the liability of an economic operator is not reduced or disallowed where the damage was caused both by the defectiveness of the product and by an act or omission of a third party”. This includes, for instance, situations where a third party exploits a cybersecurity vulnerability in a product and thereby contributes to the harm suffered (see Recital 55). In such cases, the economic operator remains fully liable to the injured party, regardless of the third party’s involvement.[20] This approach has raised concerns in the legal literature, especially given the rising complexity of software, AI, and cybersecurity risks, which make it more likely that defects emerge post-market.

Scholars suggest the “later defect” defence, claiming the defect arose only after placement, may be used more often.[21] However, Article 13(1) of the Directive, to be transposed in Dutch law, already weakens this defence, allowing liability even when unforeseeable third-party actions contribute to the harm. This heightens legal uncertainty for manufacturers and digital service providers, particularly in sectors dependent on continuous updates and third-party integrations.

The risk of litigation (individual or collective) is real. In Article 6 of the Directive, the destruction of private data may qualify as damage, introducing important new grounds for product liability claims. Moreover, data can raise product liability issues when it functions as an integral component of a product’s performance. A grey area arises when a defective device does not cause physical harm but is compromised, through hijacked connections or stolen personal data. While traditional malfunctions can still cause injury, smart devices introduce new risks, including malicious access to sensors and data loss.

In another significant expansion of the current law, consumers suffering psychological harm (e.g. distress), even indirectly, from such breaches may attempt to claim under the strict liability regime.[22]

In conclusion, given the rising cybersecurity threats, the PLD’s recognition of both physical safety and “digital well-being” clearly broadens the liability for defective digital products.

2.2.5 Addressing Latent Defects and Post-Market Issues

As explained, the PLD heightens risk for developers by imposing liability for defects that emerge later, even if unforeseeable at launch. The risk of collective action may arise even if consumers fail to install safety updates since such a failure could be caused by poor manufacturer communication, complex update processes, or flawed mechanisms and it impacts large groups of consumers similarly. In essence, the broader liability of the PLD encourages collective actions, particularly in complex tech cases where latent defects surface post-market and affect many consumers in comparable ways.

Additionally, Article 191a provides that the injured party’s right to compensation against the operator under Article 185(1) shall lapse ten years from the date the defective product that caused the damage was placed on the market or put into service. In the case of a substantially modified product, this period begins from the date the modified product was made available on the market or put into service. However, by way of derogation, the right to compensation may instead lapse after 25 years if the injured party was unable to bring a claim within the 10-year period due to the latency of a bodily injury.

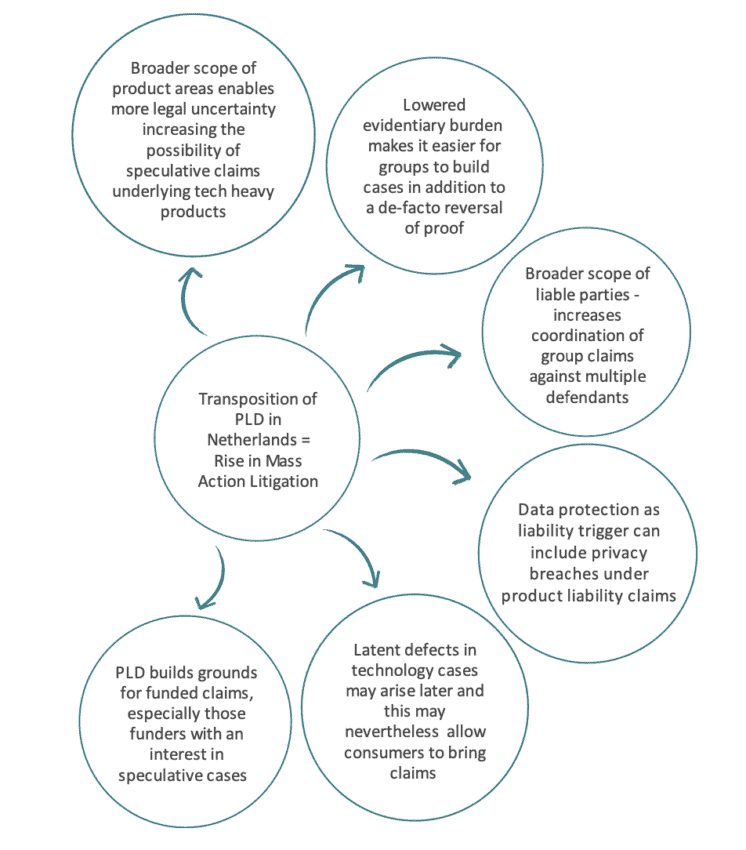

Figure 1 provides a visual summary of the key factors discussed in this Chapter, highlighting the interaction between the Dutch collective action system and the transposition of the EU PLD. It outlines how the legal framework for collective actions in the Netherlands, combined with the expanded scope of liability under the PLD, could potentially lead to an increase in mass litigation.

Figure 1: PLD transposition bringing new legal framework while unlocking avenues for class action lawsuits Source: ECIPE

Source: ECIPE

[1] BIICL & ICLJ. (2023) Class and Group Actions Laws and Regulations Netherlands 2024. Available at https://iclg.com/practice-areas/class-and-group-actions-laws-and-regulations/netherlands

[2] A claimant can either bundle individual claims based on a power of attorney granted by individual claimants or bring a bundle of claims in their own names after obtaining ownership through assignment. The term “special purpose” refers to ad hoc legal entities – stichting (foundation) or claimstichtingen. See: BIICL. (2020). Collective Redress: The Netherlands. Available at: https://www.collectiveredress.org/documents/31_the_netherlands_report.pdf; also see: Knigge, A. and Wijnberg, I. (2020, September 1). Class/collective actions in The Netherlands: overview. Houthoff. Available at: https://www.houthoff.com/-/media/houthoff/publications/aknigge/thomson-reuters_class_collective-actions-in-the-netherlands_overview.pdf

[3] In the Shell Petroleum case (29 May 2009, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2009:BI5744), shareholders alleged securities fraud concerning the restatement of petroleum reserves by Royal Dutch Shell. In the Vedior case (15 July 2009, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2009:BJ2691), the allegations involved securities fraud related to mergers and acquisitions. In the Converium case (17 January 2012, (ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2012:BV1026), shareholders claimed securities fraud due to the inaccurate disclosure of loss reserves, see: Hensler, D. R. (2010). The future of mass litigation: Global class actions and third-party litigation funding. Geo. Wash. L. Rev., 79, 306.

[4] See: Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025. The Dutch legislator and courts claim worldwide validity of that opt-out approach which remains to be challenged while it is far from certain that courts in other countries would accept this claim. The EU legislator, at least, has explicitly excluded the opt-out approach for cross-border consumer matters under the RAD, prompting the Dutch legislator to explicitly limit WAMCA accordingly for cases within the increasing remit of the RAD.

[5] Kramer, X. E., Tzankova, I. N., Hoevenaars, J., & van Doorn, C. J. M. (2024) Financing Collective Actions in the Netherlands. Erasmus, 9(789047), 302186

[6] Koniak, S. P. (1994). Feasting While the Widow Weeps: Georgine v. Amchem Products Inc. Cornell L. Rev., 80, 1045.

[7] Hay, B., & Rosenberg, D. (1999). Sweetheart and Blackmail Settlements in Class Actions: Reality and Remedy. Notre Dame Law Review., 75, 1377.

[8] Article 237 (1) of Dutch Code of Civil Procedure

[9] The losing party is ordered to pay the litigation costs, including the legal fees. Legal fees, in particular, are determined based on a liquidation tariff (Liquidatietarief), which is a standardised fee schedule that takes into consideration the complexity and financial importance of the case. The amount awarded based on the liquidation rate is often lower than the actual fees paid to the attorney or representative. Additionally, in certain instances, the court may choose to offset the litigation costs if both parties were partially unsuccessful. The court may also decide to waive or reduce costs if specific circumstances exist that would prevent fully burdening the losing party with costs. See: Heussen. Understanding Litigation Costs. Available at: https://www.heussen-law.nl/es/noticias/news-archive/view/241#:~:text=NEWS- ,Understanding%20Litigation%20Costs,-Legal%20costs%20can

[10] Tzankova, I. N. (2011). Funding of mass disputes: lessons from the Netherlands. JL Econ. & Pol’y, 8, 549. referenced in BIICL. Collective redress: The Netherlands. Available at: https://www.collectiveredress.org/documents/31_the_netherlands_ report.pdf

[11] See Article 6 of Directive 85/374/EEC.

[12] Recent IoT Class Actions Highlight Need for Manufacturers & Vendors of Connected Products to be Aware of Liability Risks, Nilan Johnson Lewis Pa (Jan. 28, 2020), https://nilanjohnson.com/recent-iot-class-actionshighlight-need-for-manufacturers-vendors-of-connected-products-to-be-aware-of-liability-risks/

[13] BEUC (2020). Product Liability 2.0 – How to make EU rules fit for consumers in the digital age. BEUC-X-2020-024 – 07/05/2020

[14] Centre for Strategy and Evaluation Services. (2018). Impact assessment study on the possible revision of the Product Liability Directive (PLD) 85/374/EEC– No. 887/PP/GRO/IMA/20/1133/11700, P 34

[15] In its 2020 Report on the safety and liability implications of Artificial Intelligence, the Internet of Things and robotics, the European Commission notes that IoT and AI systems complicate efforts to establish the conditions for a successful claim. In response, the Directive introduces rebuttable presumptions (Article 10(2) – (5)) to ease the claimant’s evidentiary burden. See: European Commission. (2020). Commission Report on safety and liability implications of AI, the Internet of Things and Robotics. COM (2020) 64 final. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/commission-report-safety-and-liability-implications-ai-internet-things-and-robotics-0_en

[16] See Article 3(1) of Directive 85/374/EEC

[17] See Article 3(2) of Directive 85/374/EEC

[18] See Article 3(3) of Directive 85/374/EEC.

[19] The previous wording of 1985 was in principle the same. Article 8: “(1) Without prejudice to the provisions of national law concerning the right of contribution or recourse, the liability of the producer shall not be reduced when the damage is caused both by a defect in product and by the act or omission of a third party. (2) The liability of the producer may be reduced or disallowed when, having regard to all the circumstances, the damage is caused both by a defect in the product and by the fault of the injured person or any person for whom the injured person is responsible.”

[20] European Commission. (2020). Commission Report on safety and liability implications of AI, the Internet of Things and Robotics. COM (2020) 64 final. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/commission-report-safety-and-liability-implications-ai-internet-things-and-robotics-0_en

[21] Centre for Strategy and Evaluation Services. (2018). Impact assessment study on the possible revision of the Product Liability Directive (PLD) 85/374/EEC– No. 887/PP/GRO/IMA/20/1133/11700, P 34

[22] Becker, M. et al. (2024, October 10). The EU Product Liability Directive: Key Implications for Software and AI. Risk and Compliance. Available at: https://riskandcompliance.freshfields.com/post/102jk3j/the-eu-product-liability-directive-key-implications-for-software-and-ai

3. The High Costs of Collective Action as a Method of Consumer Redress (Including Product Liability)

Mass litigation is an expensive approach to deliver consumer redress. This is because, regardless of the awards granted to consumers, lawyers’ fees account for a substantial portion of the non-damages costs. In the Netherlands, these fees could be about €25,000 for summary proceedings; between €40,000 and €50,000 for substantive proceedings, depending on the complexity of the case; and €150,000 to €500,000 for drafting the summons.[1] In the Shell Petroleum settlement, claimants’ counsel walked away with $47 million. Similarly, in the Converium settlement, claimants’ counsel pocketed 20 percent of the $58 million payout to claimants.[2] Moreover, in opt-out cases, undistributed damages often sit idle in escrow accounts, as was seen in the Converium settlement, which raises the question as to who should receive those undistributed funds.[3]

To fund these cases, the Dutch litigation system relies on TPLF.[4] The expansion of TPLF has been supported by flexible rules and substantial rewards. For example, during the 2014 consultation on the WAMCA Bill, Australian litigation funder IMF Bentham submitted a paper to the Dutch Ministry of Justice (MoJ) revealing that it had historically achieved average gross returns on investment of 298 percent. This return was exceptionally high, especially considering that investors from major international corporations typically consider a return on investment (RoR) of 8-25 percent to be favourable.[5]

Judges may rule against claimants, and funders risk losing their investments. This was evident in a data breach case that allegedly affected 6.5 million individuals in the Netherlands. However, in reality, only the data of 1,250 individuals had been “misused,” and no material damage was suffered by the claimants.[6] The funder invested EUR 1 million in the case and, had it succeeded, stood to earn a 500 percent return on investment.[7] While such a decision is part of a “portfolio” strategy for litigation funders, the Dutch National Health Service (GGD) incurred significant legal and litigation costs – resources that could have been better directed towards patient care, medical research, advanced medical technologies, or essential medicines.

The case against the GGD provides an example of an additional effect of mass litigation on the Dutch economy. Many of the mass claims cases have been brought against public entities, such as government authorities or publicly owned organisations, with resulting payouts from the public budget being substantial. In the context of the transposition of the PLD, Dutch public entities regulate or enforce safety standards in certain markets and products, and therefore share part of the responsibility when these products cause harm. As a result, state responsibility in mass harm events could increase, amplifying the financial impact of mass litigation on the public purse.

Given the expanded liability for digital technologies supported by the new PLD, compensatory actions to address alleged infringements are likely to become more common. On the one hand, the nature of latent faults in digital products means that large numbers of consumers could be affected by the same defect. On the other hand, the extended limitation period creates a broad window for potential claims over time.

These two dynamics increase the likelihood that the PLD’s transposition will give rise to long-tail liabilities, creating grounds for future mass litigation. As is the case with some current collective actions, claimant lawyers may struggle to provide credible evidence to justify these damages. This challenge may encourage companies to go to court to defend themselves. However, they will also face media scrutiny which can damage their reputation (See “blackmail settlements” in Section 2.1). In such situations, CEOs and CFOs may opt to settle a case for reputational reasons, particularly considering the potential impact on the company’s stock price (see Chapter 6).

The combination of collective actions and out-of-court settlements raises the costs of delivering collective redress. This raises questions about the entire system, as the combined costs of providing consumer redress in the Netherlands – such as legal fees, pressure on the judicial resources, direct costs to companies, and the opportunity costs of the resources spent on litigation – can be far more substantial than the actual reward granted to consumers. Moreover, since consumers do, particularly in opt-out cases, as in the Netherlands, often not even claim the compensation they have been awarded and are entitled to, the imbalance between the financial burden that collective action imposes on the system and the total compensation actually paid to affected individuals is much more pronounced, as mentioned especially for opt-out cases. If the transposition of the PLD leads to an increase in collective actions in the Netherlands, the costs of consumer redress will rise correspondingly, disproportionately exceeding the actual compensation paid to affected individuals.

[1] Kramer, X. E., Tzankova, I. N., Hoevenaars, J., & van Doorn, C. J. M. (2024) Financing Collective Actions in the Netherlands. Erasmus, 9(789047), 302186

[2] In an essay based on a keynote address given at a conference at the George Washington University Law School, the author discusses insights from several interviews conducted with the participants in the Shell case. It was disclosed that Grant & Eisenhofer covered the legal fees and expenses for the foundation involved. The fees paid to both US and non-US law firms as part of the global settlement did not require review or approval from the Amsterdam Court of Appeals, although the amount was disclosed during the approval process. Grant & Eisenhofer received $47 million for negotiating the settlement of claims which they reportedly shared with two other firms. See: Hensler, D. R. (2010). The future of mass litigation: Global class actions and third-party litigation funding. Geo. Wash. L. Rev., 79, 306.

[3] Telegraaf. (2021). Door Pels Rijcken-topman beroofde claimstichting: ’we zijn genaaid’ Copy On Record. Also see: Bentham. (2014). Submission to the Ministry of Security and Justice Dutch Draft Bill on Redress of Mass Damages in a Collective Action.

[4] About 48 funders are active in the Netherlands, the highest number for any EU country. Source: Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p. 37.

[5] Conversation with a legal expert, On Record.

[6] The case was recently thrown out by a judge as basically being frivolous., Ibid

[7] TV program of the Dutch public broadcaster NOS called “Nieuwsuur” of 8 February 2022. Source: https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2416277-de-uitzending-van-8-februari-meer-gevallen-grensoverschrijdend-gedrag-hoe-de-politie-demonstraties-aanpakt-chinese-camera-s-in-nederland-het-verdienmodel-achter-massaclaims

4. The Growing Reach of Mass Litigation in the Netherlands and Its Threat to Economic Competitiveness

For this study, the database of collective actions in the Netherlands compiled for a previous study has been updated, resulting in the inclusion of seven additional cases. However, the findings regarding the number of collective actions over time and across economic sectors remain largely consistent with that previous research.[1]

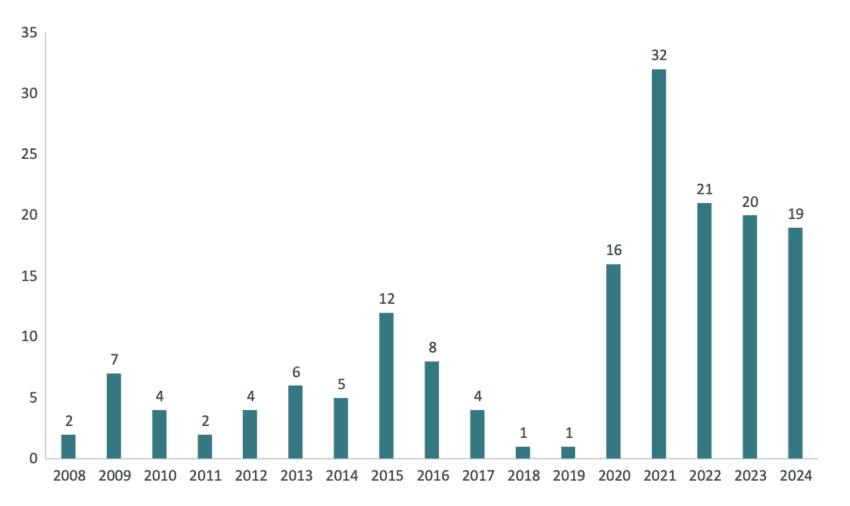

The Netherlands has experienced a significant increase in collective action lawsuits over time. Between 2008 and 2019, the average number of cases per year was just five, with a peak of twelve in 2015. Following the implementation of the WAMCA in 2020, the average rose to twenty-two cases per year, peaking at thirty-two in 2021. Since then, approximately twenty cases have been filed each year (in 2022, 2023, and 2024).

Compared to other EU countries, the Netherlands has the highest number of collective actions. Adjusted for population size, the Netherlands had 9.3 cases per million people from 2008 to 2023, significantly higher than the UK (2.3), Germany (0.5), and France (0.4), making it the most litigation-intensive jurisdiction per capita in Europe. In the more recent period (2020-2023), the Netherlands recorded 89 cases, a number comparable with the UK, a common law country with an established tradition of collective actions, for the highest absolute number. The following figure illustrates the number of collective action lawsuits in the Netherlands from 2008 to 2024.

Figure 2: Number of collective action lawsuits in the Netherlands (2008-2024) Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

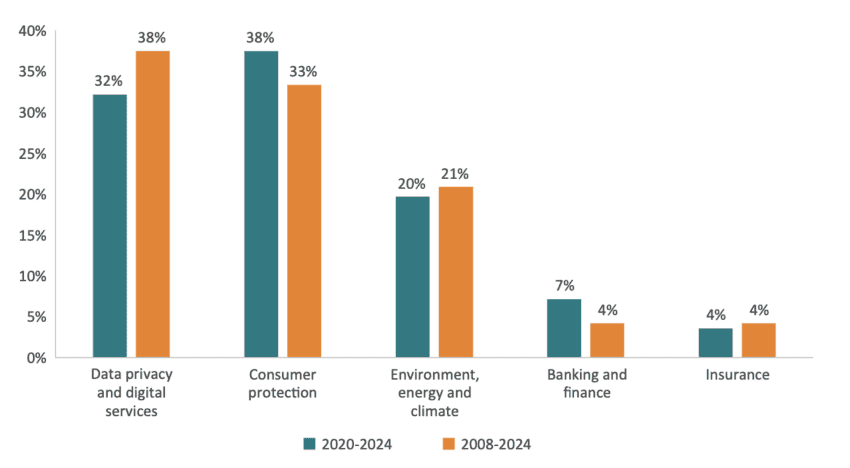

Figure 3 presents the breakdown of cases across broad economic categories. Between 2008 and 2024, consumer protection was the sector with the highest number of collective action lawsuits. However, the data also reveals that privacy and digital services became the sectors with the most cases in the period from 2020 to 2024. This finding reinforces the trend described earlier, where a significant number of collective actions in the Netherlands involve digital companies and data.

Figure 3: Share of collective action lawsuits by economic area in the Netherlands (2008-2024) and (2020-2024) Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits. Note: not all the cases included sufficient information to allocate the case to a particular economic area. In the period 2008-2024, 66 percent of the cases could not be allocated and for the 2020-2024 period, the figure was 56 percent.

Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits. Note: not all the cases included sufficient information to allocate the case to a particular economic area. In the period 2008-2024, 66 percent of the cases could not be allocated and for the 2020-2024 period, the figure was 56 percent.

The growing importance of data privacy and digital services collective action cases in the Netherlands is particularly relevant when discussing the economic impact of the interaction between the transposition of the EU PLD and the Dutch collective action system. PLD will likely generate additional claims by introducing, as outlined in Chapter 2, new legal grounds for liability, expanding the scope of damages and products covered and by providing significant new procedural advantages for claimants, thereby amplifying the impact of not only individual litigation but also existing collective mechanisms like WCAM and WAMCA on the Dutch economy. Therefore, it is far more probable that the total number of collective actions in the Netherlands will rise following the transposition of the PLD as it currently stands.

This is particularly relevant for the Netherlands, not only because it has a legal system more conducive to collective action, but also because the digital sector and digital technologies – which is likely to see an increase in collective actions – are a vital part of the Dutch economy. In fact, Dutch firms are among the most digitally advanced in the EU. According to the Digital Intensity Index (DII) produced by Eurostat,[2] the Netherlands ranks sixth in the EU for the average number of companies with the most intensive use of digital technologies.[3] Such strong performance did not occur by chance. It is the result of a concerted and ongoing effort by the Dutch government to accelerate the digital transition in Netherlands.[4]

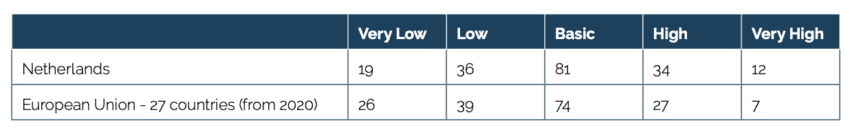

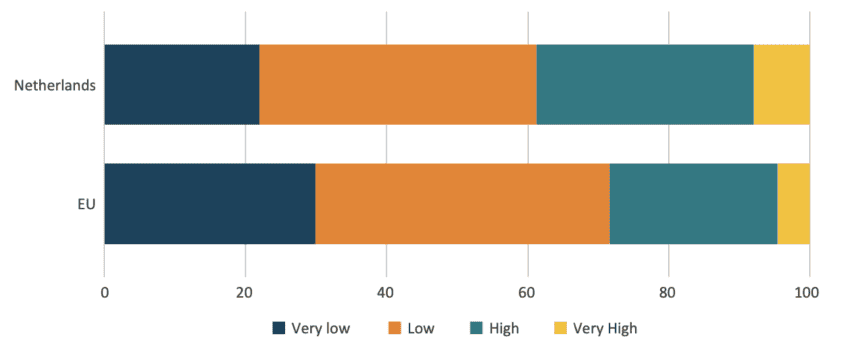

Table 1 below presents the percentage of firms with very low, low, basic, high, and very high usage of digital technologies for both the Netherlands and the EU. The data clearly demonstrates that the Netherlands has a higher percentage of companies with basic, high, and very high digital intensity, and a lower percentage with low and very low digital intensity compared to the EU.

Table 1: Percentage of firms with very low, low, basic, high, and very high digital intensity in the Netherlands and the EU, 2024 Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat

A similar argument applies when comparing Dutch SMEs with their EU counterparts. The following figure shows that a higher percentage of Dutch SMEs have high or very high usage of digital technologies, while the share of Dutch firms with very low or low digital intensity is lower than that of the EU.

Figure 4: Percentage of SMEs with very low, low, high, and very high digital intensity in the Netherlands and the EU (2024) Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat

Therefore, given the broad scope of the PLD, which holds producers, importers, and companies along the value chain potentially liable, Dutch companies incorporating digital technologies into their goods and services may face the risk of collective action under the PLD. This is particularly concerning given that digital technologies have become a crucial tool for boosting competitiveness and overall economic prosperity.[5]

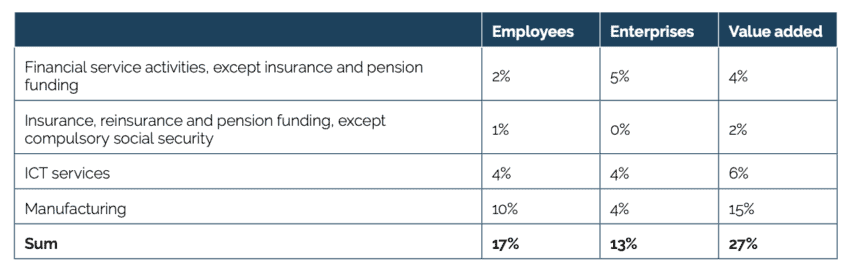

When assessing the economic sectors likely to be impacted by the new PLD and collective action, the expanded scope of products covered by the Directive (outlined in Chapter 2) suggests that a significant portion of the Dutch economy will be affected by its transposition. For example, it is reasonable to assume that sectors such as financial services, insurance, Information and Communications Technology (ICT) services, and manufacturing will fall under the new PLD. Table 2 presents the size of these sectors within the business economy, measured by the number of employees, enterprises, and value added. The table shows that these four sectors together account for 17 percent of employees, 13 percent of enterprises, and 27 percent of the total value added in the Dutch market economy.[6]

Table 2: Share of employees, enterprises, and value-added over the Dutch market economy (2022) Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat

These are not just any sectors; they are key drivers of the current economic growth in the Netherlands. In fact, some of these sectors, or subsectors within them, have received specific attention from the Dutch government as long-established pillars of the Dutch economy.[7]

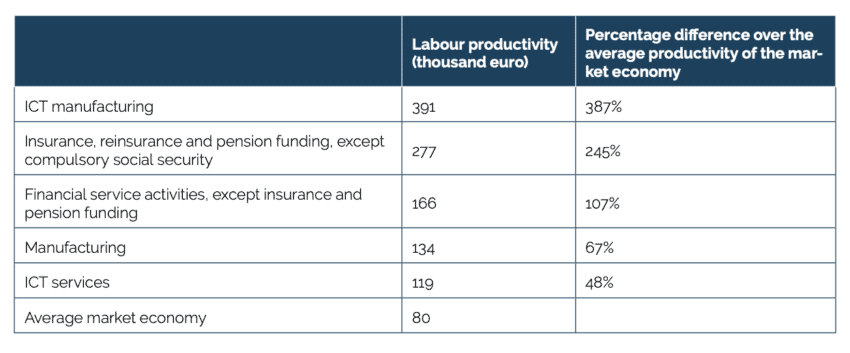

Table 3 shows the labour productivity (measured in thousand euros) of these sectors, disaggregating ICT manufacturing from overall manufacturing, as ICT manufacturing will be particularly affected by the new PLD. The table compares this productivity with the average productivity of the market economy. Clearly, these sectors not only represent a large share of the Dutch economy (See Table 2) but are also among the most powerful engines driving its growth.

Table 3: Labour productivity in thousand euro in selected sectors and comparison with market economy, the Netherlands (2022) Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat. Labour productivity is defined as value added at factor costs divided by the number of persons employed.

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat. Labour productivity is defined as value added at factor costs divided by the number of persons employed.

Based on the transposition of the PLD into Dutch law presented previously, the ICT sector is clearly going to face an increased risk of mass litigation. In the past, many collective actions in the Netherlands have been launched against US digital companies (see Chapter 5). However, as the Dutch economy becomes more digital, with companies like ASML, some of the largest and most productive in the ICT sector, it is highly likely that, as was the case with the Dutch National Health Service, Dutch companies producing or using digital technologies will be impacted by this kind of litigation.

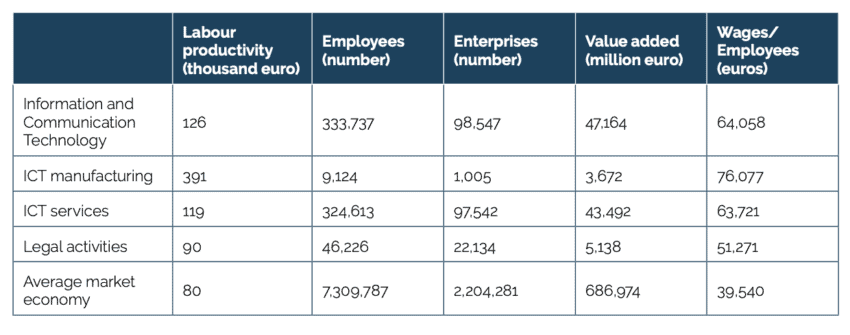

Table 4 highlights the importance of the Dutch ICT sector. It presents labour productivity, the number of employees, the number of enterprises, value added, and the average wage per employee for the overall ICT sector, its manufacturing and services component, the average market economy, and legal services. The inclusion of legal services is due to address the argument that collective actions particularly benefit this sector. The table clearly shows that, across all economic indicators, the Dutch ICT sector is significantly more economically important and contributes more to the market economy than the legal sector.

Table 4: Economic indicators for selected sectors, the Netherlands (2022) Source: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat

[1] Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025

[2] Eurostat. Digital Intensity by NACE Rev. 2 activity. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ISOC_E_DIIN2__custom_5140920/default/table?lang=en

[3] The 12 digital technologies assessed by the DII include: (1) Internet access for more than 50 percent of employees; (2) Employment of ICT specialists; (3) Use of fast broadband (≥30 Mbps); (4) Provision of portable devices with mobile internet for over 20 percent of employees; (5) Having a website; (6) Website with sophisticated functionalities (e.g., online ordering, tracking); (7) Use of 3D printing; (8) Purchase of medium-high cloud computing services; (9) Sending invoices suitable for automated processing; (10) Use of industrial or service robots; (11) E-commerce sales accounting for at least 1 percent of total turnover; and (12) Analysis of big data internally or externally.

[4] Nederland Digitaal. (2023, July 11). Digital Economy Strategy. https://www.nederlanddigitaal.nl/documenten/publicaties/2023/07/11/digital-economy-strategy

[5] Guinea, O., & Sharma, V. (2025). The Future of European Digital Competitiveness. ECIPE, Brussels, policy brief 2/2025.

[6] The market economy includes industry, construction and market services and excludes public administration and defence; compulsory social security; and activities of membership organisations.

[7] Netherlands Enterprise Agency. (2019, September 27). Joining a Top consortium for Knowledge and Innovation (TKI). Available at: https://english.rvo.nl/subsidies-financing/pps-toeslag-onderzoek-en-innovatie/joining-tki

5. The Netherlands as Europe’s Litigation Magnet

As explained in Chapter 2, the Netherlands has a relatively more favourable legal system for mass litigation compared to other EU countries. This was clearly demonstrated in our previous research. The Netherlands ranks at the top of the Index of Institutional Framework for Mass Litigation (IFML) with a score of 0.9. Furthermore, as discussed in the previous chapter, the Netherlands recorded the highest number of collective actions in the EU and the highest number of cases per capita in Europe (EU27 and the UK). In our previous study, we showed a close correlation between the IFML and the number of collective actions.[1] This is particularly evident in the Netherlands: the easier it is to launch a collective action in the Netherlands, the more cases the country will register.

There is an external dimension to the ease of launching a collective action and the number of cases. Litigation claims can be “imported”. Mass litigation cases often originate in the US, and depending on the level of traction they gain in US courts, similar claims are frequently filed in other jurisdictions. It can be assumed that when deciding where to bring a claim within the EU, US claimant lawyers will choose the jurisdiction that offers the greatest advantages in terms of ease of bringing the claim and the likelihood of winning the case or securing a settlement.[2]

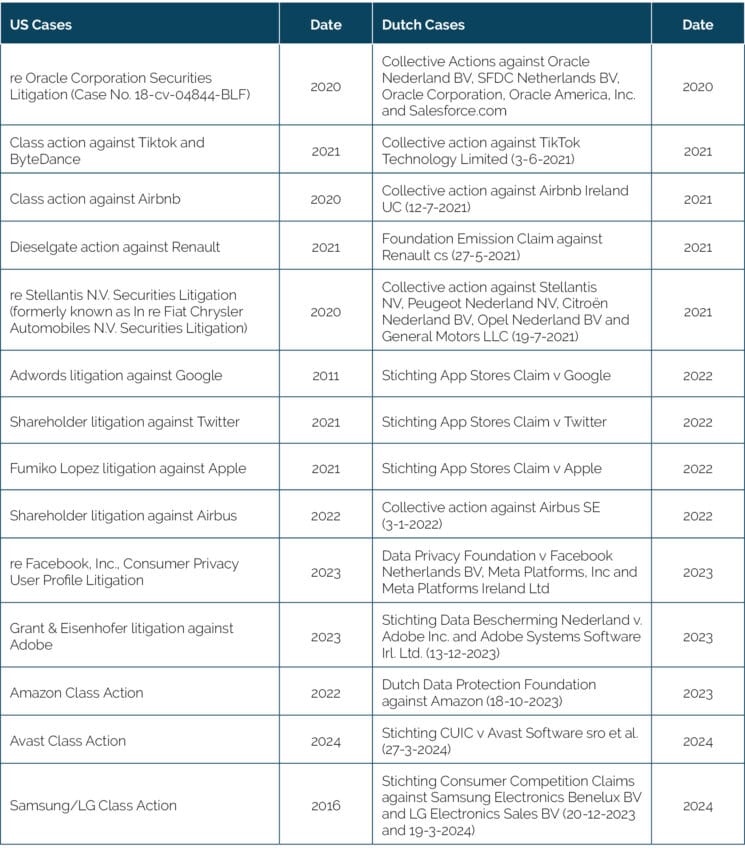

In Erixon et al (2025), we showed that out of the 373 collective action cases in all of the EU, 48 lawsuits were related to cases filed against the same companies in the US, the so-called “copy-cat cases”. Of those 48 cases, 14 (29 percent) were filed in the Netherlands. The following table presents these 14 cases launched in the Netherlands alongside the corresponding cases in the US.

Table 5: Collective action lawsuits in the Netherlands against the same company as a US case Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

Source: ECIPE’s database of collective action lawsuits.

Liability cases and collective actions are closely related. If liability cases become more common in the Netherlands following the transposition of the PLD into Dutch law, it is likely that some of the collective action cases previously pursued in the US for liability breaches will also be tried in the Netherlands.[3] There are two key factors supporting this argument that have been explained previously in Chapter 2: the relatively favourable legal system to mass litigation in the Netherlands and the expansion of what qualifies as a product under the revised PLD.

In the past, the strategy employed by some plaintiffs’ counsel in mass litigation cases was not focused on winning individual claims on their merits but rather on creating the perception that a large number of people had experienced issues with a particular product.[4] The same approach can be applied to liability cases based on other arguments but the traditional one of a direct defect of the very product as such itself. Most such liability claims are not based on allegations that a product is inherently defective, but rather on the argument that it posed a risk that users were not adequately warned about. Claims are then filed on behalf of a minority who allegedly suffered side effects or harm due to insufficient warnings.[5] Multi-jurisdictional product liability claims, from the US to the Netherlands, align with this dynamic. If a company is found liable in the US for the malfunction of a product or service that caused harm, similar arguments can be made in other jurisdictions. Given that the institutional framework for mass litigation is more favourable in the Netherlands than in any other EU country, cases involving US-based liability may also be brought to Europe, with Dutch courts potentially serving as the first venue for such claims.

Following the expansion of what qualifies as a “product” under the revised PLD, as described in Chapter 2, an increase in claims involving digital products or products containing digital technologies, such as IoT devices, is to be expected. Two class action lawsuits have already been filed in the US, alleging that consumer security systems are defective due to vulnerabilities that allow hackers to spy on and harass users in their homes.[6] While these cases are primarily framed as product failures and torts, they also intersect with data privacy law, highlighting the expanding scope of product liability claims.

Similarly, product liability claims are emerging against social media platforms. US plaintiffs have brought cases against platforms such as YouTube and TikTok, alleging that the in-app reporting tools were defectively designed.[7] Specifically, they argue that these features failed to prevent harmful or dangerous content from remaining online even after being flagged, contributing to personal harm. This litigation builds upon earlier claims against TikTok for breaches of data protection and privacy law, which have already been filed in the Netherlands. It reinforces the notion that liability can arise not only from the content on these platforms, but also from the underlying architecture and design choices. In a separate case, In re: Social Media Adolescent Addiction/Personal Injury Products Liability Litigation,[8] the US court determined that “in certain circumstances a reporting tool could be a defective product.”

The European Commission acknowledges[9] that IoT and AI systems introduce complexities in proving defect and causation. However, it does not suggest that these complexities preclude claims from being filed. Given the Dutch courts’ openness to adopting US-style litigation, either in a multi-jurisdictional context or involving similar claims, it is plausible that the previously mentioned examples of IoT and platform-based liability claims will find similar legal grounding in the Netherlands, especially after the transposition of the PLD.

[1] Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p.53

[2] American firm Hausfeld has opened operations in several EU member states and has launched a class action claim in the Netherlands on behalf of 13.4 million Google Android users. See: Lexology (2022, October 20) Google hit with Dutch class action Android claim. Available at: https://www.lexology.com/pro/content/google-hit-with-dutch-class-action-android-claim

[3] Conversely, the low thresholds and burden-shifting provisions introduced by the PLD, along with court rulings that may find liability against approved products in the EU, could lead to follow-on mass claims against the same product and its producer in the US. This marks an important reversal of current practice.

[4] Bird and Bird. (2018). Multijurisdictional Product Liability Claims. Available at: https://www.twobirds.com/-/media/pdfs/news/articles/2021/uk/cd_multijurisdictional-product-liability-claims_jonathan-speed_apr2018.pdf

[5] Ibid

[6] Nilas Johnson Lewis. Recent IoT Class Actions Highlight Need for Manufacturers & Vendors of Connected Products to Be Aware of Liability Risks. Available at: https://nilanjohnson.com/recent-iot-class-actions-highlight-need-for-manufacturers-vendors-of-connected-products-to-be-aware-of-liability-risks/

[7] Dechert. (2025). Federal Court Dismisses Products Liability Challenge to Social Media Platforms’ Content Moderation Tools. Available at: https://www.dechert.com/knowledge/re-torts/2025/3/federal-court-dismisses-products-liability-challenge-to-social-m.html

[8] United States District Court for the Northern District of California. (n.d.). In re: Social Media Adolescent Addiction/Personal Injury Products Liability Litigation (MDL No. 3047). Retrieved May 16, 2025, from https://cand.uscourts.gov/in-re-social-media-adolescent-addiction-personal-injury-products-liability-litigation-mdl-no-3047/

[9] European Commission. (2020). Commission Report on safety and liability implications of AI, the Internet of Things and Robotics. COM (2020) 64 final. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/commission-report-safety-and-liability-implications-ai-internet-things-and-robotics-0_en

6. The Impact of Collective Action and PLD on the Dutch Economy

6.1 The Impact of Collective Actions on the Economy: A Summary of the Empirical Evidence

There have been several empirical studies that attempt to estimate the costs of collective action. However, most of these studies have been done for companies operating in the US. Yet, they provide useful data that illustrate the impact of private enforcement on a variety of economic indicators.

- Impact on Gross Domestic Product (GDP): a study by the US Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform (2024) estimates that private enforcement in the US incurs substantial costs, amounting to approximately 2.1 percent of US GDP in 2022.[1]

- Increase in litigation costs: the 2024 US Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform study also quantifies the increase in US tort costs (both costs and compensation) over time, showing a 51 percent rise between 2016 and 2022.[2]

- Impact on business decisions: a study examining US private companies revealed that the threat of lawsuits, including potentially frivolous or unfair claims, influences the business decisions of 62 percent of respondents. This pressure leads companies to prioritise avoiding litigation over other strategic considerations, such as business growth.[3]

- Impact on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): even though SMEs account for approximately 20 percent of commercial revenue, they bear nearly 48 percent of the burden of tort liability costs in the US.[4] This imbalance is further exacerbated by the impact of insurance premiums and legal penalties, with very small businesses (those generating under $1 million annually) facing significantly higher tort costs per dollar of revenue than larger firms.[5]

6.2 The Impact of Mass Litigation on Innovation

One of the most significant economic impacts of collective action is on innovation. Collective action introduces unpredictability both in terms of the subject (courts ultimately decide whether a firm has met its regulatory obligations) and the object (the likelihood of being taken to court varies across firms depending on their size). This added uncertainty fundamentally affects a firm’s behaviour. A company that is or could be sued is likely to direct its Research and Development (R&D) efforts towards conventional technologies, as litigation risks are predominantly associated with new products that have not been tested before.[6] As a result, the true impact of collective action on innovation is a list of inventions that have not been launched.

The reallocation of resources from R&D towards current or potential litigation is particularly concerning for the Netherlands. Dutch firms are among the most innovative in the EU. For example, the Netherlands is the third largest investor in business R&D (R&D spending by private companies) in the EU, behind only Germany and France, which have much larger economies. As a percentage of GDP, private R&D represents 1.56 percent, above the EU average and higher than in 20 other EU countries. On a per capita basis, Dutch companies invested 934 euros per person, the eighth highest in the EU, nearly double the amount spent in France.[7]

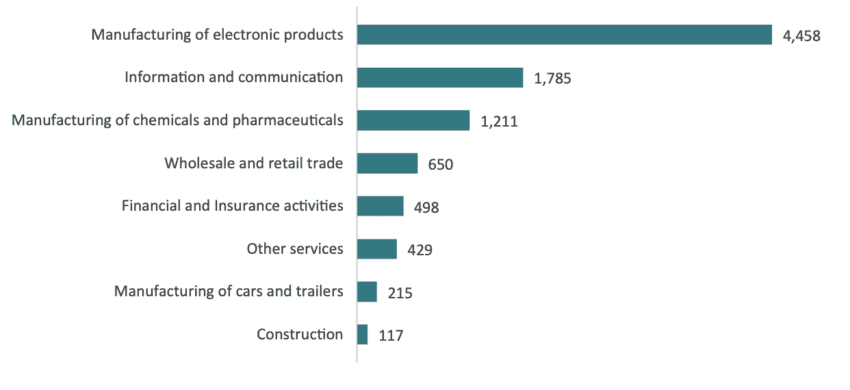

Similarly to the findings presented in Chapter 4, which describes the digital intensity of the Netherlands and the importance of economic sectors that use digital technologies, most of the R&D spending by Dutch firms is focused on sectors that will be subject to the new PLD and, therefore, are more likely to face mass litigation. Figure 5 highlights the importance of digitally intensive sectors, such as electronic products, information and communication, as well as the pharmaceutical, chemical, financial, insurance, and the transport sectors, as key drivers of private R&D spending in the Netherlands.

Figure 5: Business spending on research and development in the Netherlands (million euros, 2021) Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on OECD Analytical Business Enterprise R&D.[8]

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on OECD Analytical Business Enterprise R&D.[8]

Any factor that may undermine R&D spending in the Netherlands should raise concern among Dutch policymakers. Across various papers and initiatives,[9] the Dutch government has placed innovation at the heart of its economic policy. The government not only recognises the social benefits of R&D spending across Dutch regions,[10] but also actively supports knowledge accumulation, innovation, and R&D through public funding.

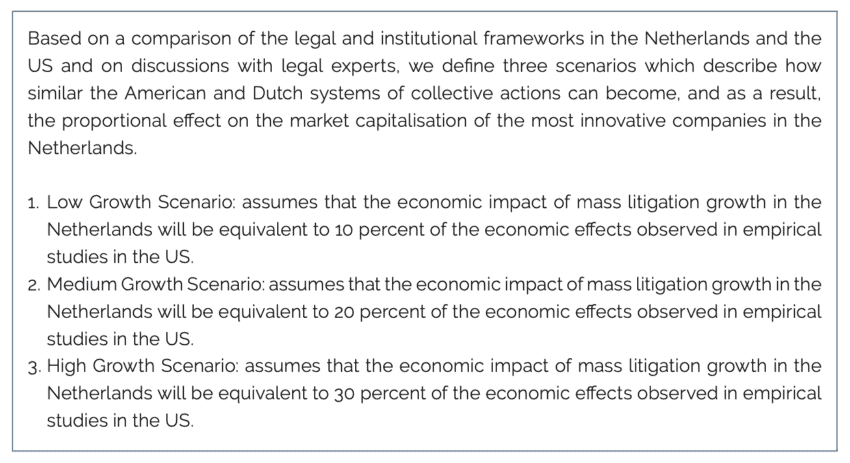

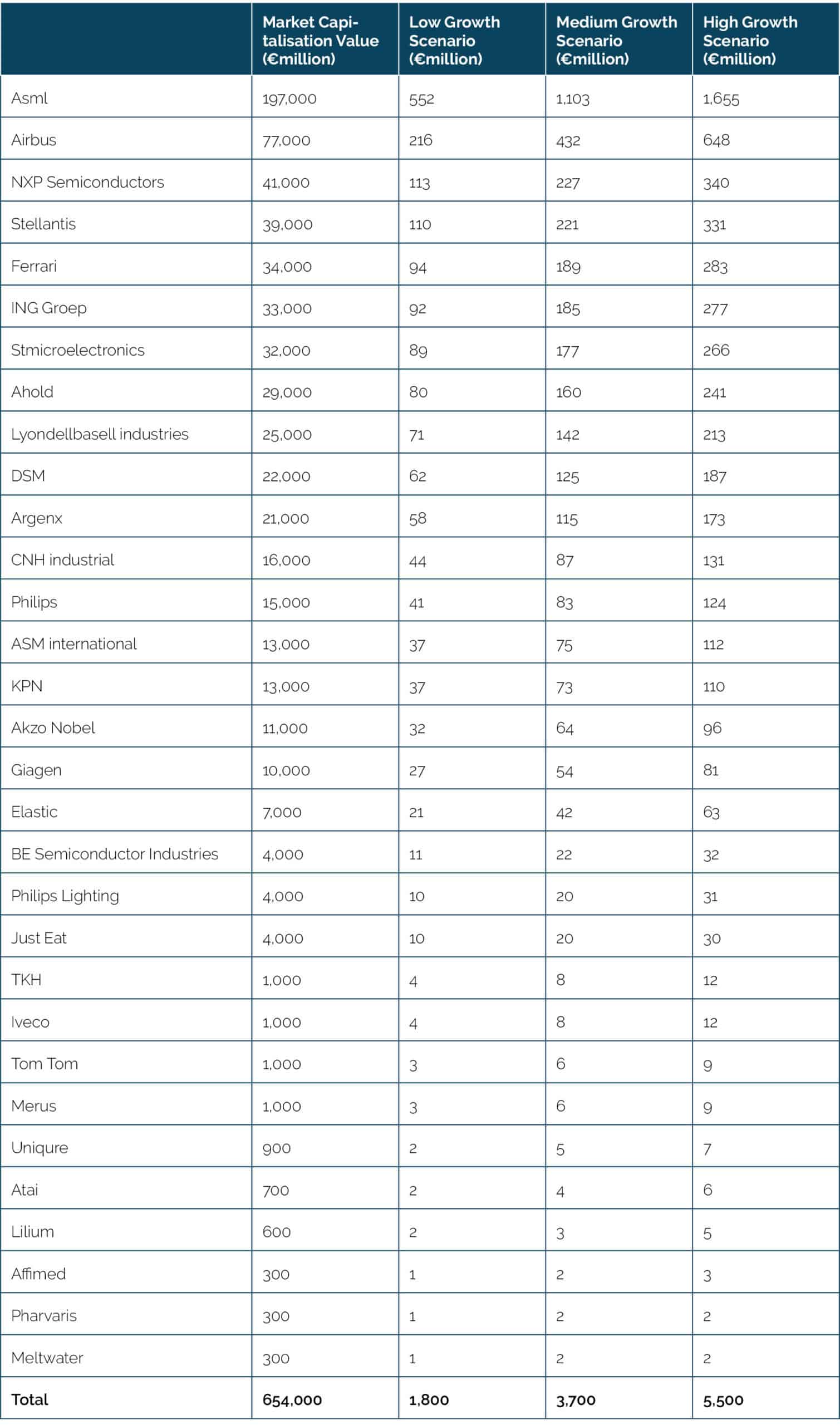

Empirically, a study by Kempf & Spalt (2020) found that mass litigation in the US adversely impacts highly innovative companies. The study reported that within three days of being targeted by a collective action lawsuit, the market value of a highly innovative company drops by 2.8 percent.[11] Following the methodology developed in our previous study[12] and briefly described in Box 1, we use the estimates from Kempf & Spalt (2020) to calculate the potential impact of collective action on the market value of the most innovative companies in the Netherlands.

Box 1: Methodology for the scenario analysis The EU’s Joint Research Centre publishes an annual report identifying the top 2,500 Research and Development (R&D) investors globally, which are regarded as the most innovative companies in the world.[13] The report includes market capitalisation data for 31 Netherlands-based companies.[14] We applied 10, 20, and 30 percent of Kempf & Spalt’s 2.8 percent finding to the aggregate market capitalisation of these companies to produce estimates for the Low, Medium, and High Growth Scenarios, respectively. The results are presented in Table 6. The impact on the market capitalisation of these 31 companies would reach €1.8 billion, €3.7 billion, and €5.5 billion per scenario, respectively.

The EU’s Joint Research Centre publishes an annual report identifying the top 2,500 Research and Development (R&D) investors globally, which are regarded as the most innovative companies in the world.[13] The report includes market capitalisation data for 31 Netherlands-based companies.[14] We applied 10, 20, and 30 percent of Kempf & Spalt’s 2.8 percent finding to the aggregate market capitalisation of these companies to produce estimates for the Low, Medium, and High Growth Scenarios, respectively. The results are presented in Table 6. The impact on the market capitalisation of these 31 companies would reach €1.8 billion, €3.7 billion, and €5.5 billion per scenario, respectively.

Moreover, the potential payment from a mass litigation case, as a share of a company’s market capitalisation, tends to be higher for Dutch companies than for US firms, which generally have a larger market capitalisation. As a result, the financial risk associated with exposure to mass claims is greater for Dutch companies.

Table 6: Reduction in market capitalisation for the top 31 Dutch R&D investors Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on European Commission (2023). The 2023 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on European Commission (2023). The 2023 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

The impact of mass litigation on public companies extends beyond corporate boardrooms. In particular, it can affect Dutch savers as well as present and future pensioners. Dutch households save around 14.6 percent of their gross disposable income, the eighth highest rate across the EU.[15] In addition, 20 percent of these savings are invested in equity. Although there is no public data on how much of these savings are invested in Dutch public companies, it is likely that a significant proportion of Dutch savers hold shares in Dutch companies.

Yet, the Netherlands truly stands out across other EU countries in terms of the amounts that Dutch households invest in their pensions, which represent 52 percent of their total investments. As a result, pension fund assets in the Netherlands amount to nearly 150 percent of its GDP. This is one of the highest shares among all EU member states, second only to Denmark at 200 percent. [16]

Pension funds in the Netherlands allocated 32 percent of their assets to capital market investments. While it is true that Dutch pension funds invest heavily in American and European companies,[17] Dutch pension funds invested a total of €189 billion in the Netherlands. Moreover, the share of pension fund investments in Dutch companies has been increasing. Between 2022 and 2023, the share of investments in the Netherlands rose from 15.7 percent to 18.3 percent.[18]

Therefore, a decline in the market capitalisation of public Dutch companies, driven by increased mass litigation, poses a risk to the financial returns of Dutch pension funds and savers. If sustained litigation pressures lead to persistent underperformance of equity holdings, especially those in high-growth, innovative sectors that have traditionally delivered strong long-term returns, then investors may experience diminished pension outcomes and returns on their savings.

6.3 The Impact of Mass Litigation on Multinational Corporations (MNCs)

Attracting multinational corporations (MNCs) to establish headquarters[19] or invest in the Netherlands has long been a priority for Dutch governments.[20] Multinational corporations assess host jurisdictions based on several criteria, including tax regimes, infrastructure, access to talent, and the legal environment. A key element of the successful Dutch business environment has been legal certainty and predictability. However, the rise of mass litigation has made the Dutch legal system increasingly uncertain and costly. With the adoption of the PLD, the legal climate for doing business in the Netherlands could become even riskier.

There is growing qualitative evidence that Dutch and foreign multinational enterprises are responding to the changing legal environment by reassessing their investments in the Netherlands. Some have relocated their legal headquarters abroad, while others have reduced their planned investments due to concerns about a deteriorating litigation climate. Although most of these decisions are officially attributed to broader corporate restructuring goals, the risk of collective action lawsuits in the Netherlands could be a contributing factor in both cases.

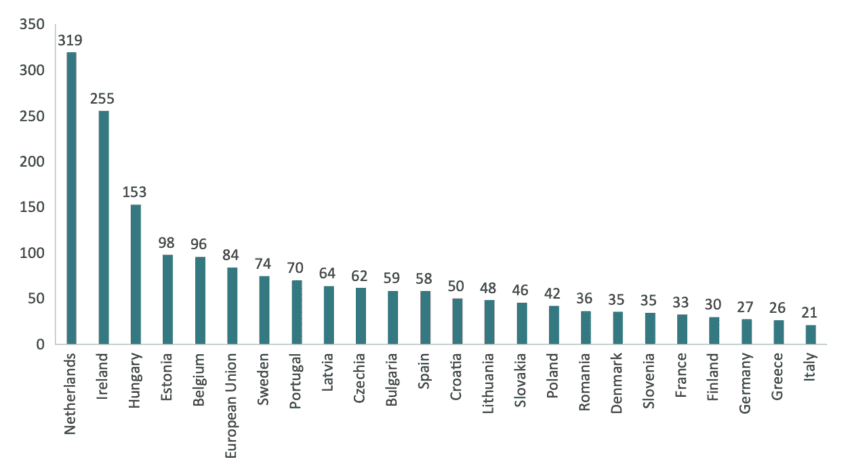

These developments pose significant risks for the Netherlands, given the importance of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to the Dutch economy. Figure 6 shows that, as a percentage of its GDP, FDI in the Netherlands was the highest in the EU, significantly surpassing the EU average and economies of similar size, such as Belgium and Spain.

Figure 6: Inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) stock as percentage of GDP (2023) Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat. Note: Luxembourg and Cyprus are outliers, with inward FDI stocks representing 3,269 percent and 1,555 percent of their respective GDPs. No data available for Malta and Austria.

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on Eurostat. Note: Luxembourg and Cyprus are outliers, with inward FDI stocks representing 3,269 percent and 1,555 percent of their respective GDPs. No data available for Malta and Austria.

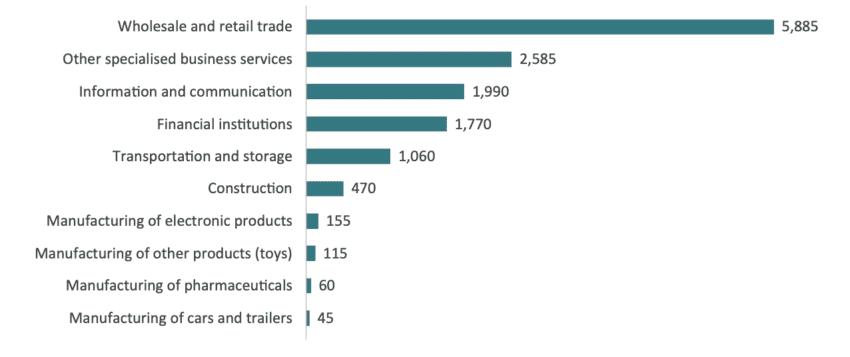

Moreover, Figure 7 shows that a significant number of foreign-owned multinationals belong to sectors where the risk of being subjected to mass litigation could increase as a result of the transposition of the PLD. Wholesale and retail trade had the highest number of foreign-owned firms, followed by the information and communication sector, and the financial sector.

Figure 7: Number of foreign-owned multinationals by sectors in the Netherlands (2022) Source: Central Bureau of Statistics Netherlands.

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics Netherlands.

While it is difficult to prove empirically, it is likely that ongoing litigation pressure could trigger broader disinvestment or the relocation of innovation-driven activities. Companies that view the Netherlands as an unpredictable or costly jurisdiction for launching new technologies may choose to move critical parts of their operations to other EU countries or markets with more balanced litigation environments. Such shifts would have real economic implications. Within the Dutch business economy, 19 percent of total employment is supported by foreign multinationals and 18 percent by Dutch multinationals.[21] Moreover, long-established economic literature demonstrates a connection between FDI and competitiveness.[22] Given the outsized role of FDI in driving GDP growth, exports, and technological leadership in the Netherlands, the potential negative impact of collective action on MNCs is an issue policymakers in The Hague must consider.

[1] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024), Tort Costs in America: Third Edition. US Chambers of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform.

[2] Ibid

[3] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2011). Creating conditions for economic growth: the role of the legal environment. NERA Economic Consulting.

[4]Ibid.

[5] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2023). Tort Costs for Small Businesses. US Chamber Institute for Legal Reform.

[6] W. Kip Viscusi & Michael J. Moore, Product Liability, Research and Development, and Innovation, 101 J. Pol. Econ. 161 (1993).

[7] European Commission. (n.d.). Research and development expenditure by business sector – indicator (rd_e_berdindr2). Eurostat. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

[8] OECD. Analytical Business Enterprise Research and Development. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/analytical-business-enterprise-research-and-development.html.

[9] Ministerie van Financiën. (2025, May 16). Beleidsartikel 2 Onderzoek, ontwikkeling en innovatie. https://www.rijksfinancien.nl/memorie-van-toelichting/2025/OWB/L/onderdeel/3151477

[10] Raspe, O., Oort, F. v., & Bruijn, P. de (2004). Kennis op de Kaart: Ruimtelijke patronen in de kenniseconomie. NAi Uitgevers & Ruimtelijk Planbureau. https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/Kennis_op_de_kaart.pdf

[11] Kempf, E., & Spalt, O. (2020). Attracting the sharks: Corporate innovation and securities class action lawsuits. Management Science, 69(3), 1805-1834.

[12] European Commission. (2020). Commission Report on safety and liability implications of AI, the Internet of Things and Robotics. COM (2020) 64 final. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/commission-report-safety-and-liability-implications-ai-internet-things-and-robotics-0_en

[13] Nindl, E., Confraria, H., Rentocchini, F., Napolitano, L., Georgakaki, A., Ince, E., Fako, P., Tuebke, A., Gavigan, J., Hernandez Guevara, H., Pinero Mira, P., Rueda Cantuche, J., Banacloche Sanchez, S., De Prato, G. and Calza, E., The 2023 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023, doi:10.2760/506189, JRC135576

[14] The market capitalisation of each firm in Table 6 refers to the value at the time the data was gathered (during 2022), rather than the most recent figure. As a result, there will be differences between the market capitalisation presented in Table 6 and the current market capitalisation.

[15] Eurostat. (2024, November). Households – statistics on income, saving and investment.

[16] OECD. (2023). Share of households and NPISHs’ currency and deposits, debt securities, equity, investment fund shares, life insurance and annuity entitlements and pension entitlements as a percentage of their total financial assets.

[17] In 2024, Dutch pension funds invested €490 billion in Europe (excluding the Netherlands) and €499 billion in the US. Source: De Nederlandsche Bank, (2025). Dutch pension funds invest more in US companies than in European companies. Accessed at: https://www.dnb.nl/en/general-news/statistical-news/2025/dutch-pension-funds-invest-more-in-us-companies-than-in-european-companies/

[18] Ibid

[19] In 2020 there were 20,000 international companies headquartered in the Netherlands. A significant increase from the 5,810 recorded in 2008. Source: Centraal Bureau Statistiek.

[20] In the early 2000s, the Dutch government actively sought to position the Netherlands as a prime location for multinational headquarters. This involved creating a favourable business environment characterised by competitive tax policies, a skilled workforce, and robust infrastructure. For instance, in 2010, the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture, and Innovation established a dedicated headquarters team with the objective of maintaining the Netherlands’ position among the top 10 global locations for multinational companies. Koster, H. (2013, October 21). Multinationals and the local economy: Implications for the Dutch ‘Topsectoren’ Policy. Urban Economics. https://www.urbaneconomics.nl/multinationals-and-the-local-economy-implications-for-the-dutch-topsectoren-policy/

[21] Statistics Netherlands. (2024, October 31). Dutch trade in facts and figures 2024. https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/publication/2024/37/dutch-trade-in-facts-and-figures-2024

[22] Multinational corporations (MNCs) tend to operate at the technological frontier, bringing advanced technology, know-how, and management practices that improve the productivity of the host economy. See Javorcik, B. S. (2004). “Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers Through Backward Linkages.” American Economic Review, 94(3), 605–627. In addition, FDI can lead to productivity gains in local firms through spillover effects when domestic firms are capable of learning from MNCs. See Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (1999). “Foreign Direct Investment as a Catalyst for Industrial Development.” European Economic Review, 43(2), 335–356.

7. Policy Considerations for the PLD Transposition

1. A Legal System Primed for Mass Litigation

- The Dutch collective redress regime is already the most active in the EU. Since the introduction of the WAMCA in 2020, the average number of collective actions has quadrupled compared to the previous decade.

- The revised PLD interacts with this legal environment in ways that make litigation more likely. The broader definition of “product”, the shift in burden of proof, and extended liability windows will amplify the trend of growing mass litigation.

2. Digital Firms Face the Highest Risk

- Digital technologies are central to the new PLD. These are also the sectors with the highest collective litigation exposure in the Netherlands. Between 2020 and 2024, most collective actions concerned digital services and data privacy. At the same time, Dutch firms are among the EU’s digital frontrunners. SMEs and large corporations alike are highly digitised, placing a large swathe of the economy in the PLD’s firing line.

- The risk is not abstract. The Dutch ICT sector alone employs over 330,000 people, generates €47 billion in value added, and outpaces legal services across every economic metric. It is among the sectors most vulnerable to long-tail liabilities.

3. Litigation Costs May Dwarf Consumer Gains

- While collective actions are often presented as tools for justice, the financial flows they generate suggest otherwise. Lawyers and litigation funders frequently receive a larger share of settlements than consumers. For example, legal fees in the Shell Petroleum and Converium settlements reached tens of millions of euros.

- The expanded pathways created by the PLD will only increase the cost of redress. Even when claims are weak or speculative, the reputational risks and legal uncertainties may force companies to settle early, diverting financial and managerial resources away from innovation and growth.

4. A Threat to Innovation and Investment

- Dutch companies are among Europe’s top investors in R&D. However, evidence from the US shows that litigation risk is disproportionately harmful to innovative firms. Using conservative assumptions, we estimate that mass litigation could reduce the market capitalisation of the Netherlands’ top R&D investors by up to €5.5 billion.

- This risk is not borne by companies alone. It spills over to households and pensioners. Nearly 20 percent of Dutch household savings are invested in equities, and pension funds, whose assets exceed 150 percent of the country’s GDP, have increased their domestic exposure to the negative impacts of collective action. A hit to the valuation of Dutch firms will impact the country’s national wealth.

5. Multinationals May Rethink Their Strategy

- Legal uncertainty is a key factor in location decisions. Foreign-owned multinationals play a pivotal role in Dutch employment and innovation. But recent examples show that a hostile litigation environment can at least contribute to accelerating, if not even trigger, disinvestment. With 19 percent of Dutch jobs tied to foreign MNCs, and FDI stock already the highest in the EU, policymakers should treat the legal unpredictability brought by collective action as a serious risk to economic prosperity.

References

Becker, M. et al. (2024, October 10). The EU Product Liability Directive: Key Implications for Software and AI. Risk and Compliance. Available at: https://riskandcompliance.freshfields.com/post/102jk3j/the-eu-product-liability-directive-key-implications-for-software-and-ai

Bleichmar Fonti and Auld LLP. In re Facebook, Inc., Consumer Privacy User Profile Litigation – Settlement Amount: $725 Million. Available at: https://www.bfalaw.com/cases-investigations/facebook-consumer-privacy

Bentham. (2014). Submission to the Ministry of Security and Justice Dutch Draft Bill on Redress of Mass Damages in a Collective Action.

Bernstein Liebhard. In re Stellantis N.V. Securities Litigation (formerly known as In re Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. Securities Litigation). Available at: https://www.bernlieb.com/featured-cases/in-re-stellantis-n-v-securities-litigation/

BEUC (2020). Product Liability 2.0 – How to make EU rules fit for consumers in the digital age. BEUC-X-2020-024 – 07/05/2020.

BIICL. (2020). Collective Redress: The Netherlands. Available at: https://www.collectiveredress.org/documents/31_the_netherlands_report.pdf

BIICL & ICLJ. (2023) Class and Group Actions Laws and Regulations Netherlands 2024. Available at https://iclg.com/practice-areas/class-and-group-actions-laws-and-regulations/netherlands

Bird and Bird. (2018). Multijurisdictional Product Liability Claims. Available at: https://www.twobirds.com/-/media/pdfs/news/articles/2021/uk/cd_multijurisdictional-product-liability-claims_jonathan-speed_apr2018.pdf

Business Wire. (2023, October 20). Grant & Eisenhofer Files Class Action Lawsuit Against Adobe Inc. on Behalf of Institutional Investors. Available at: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20231020990975/en/Grant-Eisenhofer-Files-Class-Action-Lawsuit-Against-Adobe-Inc.-on-Behalf-of-Institutional-Investors

Centre for Strategy and Evaluation Services. (2018). Impact assessment study on the possible revision of the Product Liability Directive (PLD) 85/374/EEC– No. 887/PP/GRO/IMA/20/1133/11700, p. 34.

Competition Policy International. (2016, September 12). US: Lawsuit accuses Samsung, LG of agreeing to not poach each other’s employees. Available at: https://www.pymnts.com/cpi-posts/us-lawsuit-accuses-samsung-lg-of-agreeing-to-not-poach-each-others-employees/

Dechert. (2025). Federal Court Dismisses Products Liability Challenge to Social Media Platforms’ Content Moderation Tools. Available at: https://www.dechert.com/knowledge/re-torts/2025/3/federal-court-dismisses-products-liability-challenge-to-social-m.html

De Nederlandsche Bank, (2025). Dutch pension funds invest more in US companies than in European companies. Accessed at: https://www.dnb.nl/en/general-news/statistical-news/2025/dutch-pension-funds-invest-more-in-us-companies-than-in-european-companies/

Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p. 108.

European Commission. (2020). Commission Report on safety and liability implications of AI, the Internet of Things and Robotics. COM(2020) 64 final. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/commission-report-safety-and-liability-implications-ai-internet-things-and-robotics-0_en