Building a Mature UK Trade Policy

Published By: David Henig

Research Areas: European Union UK Project

Summary

Global Britain has not delivered according to the hopes expressed by supporters of leaving the EU. Trade with the rest of the world has not grown to make up for leaving a bloc with seamless trade, early Free Trade Agreements with Australia and New Zealand are of minor economic significance, and it is hard to discern much of a strategy beyond completing a few more similar deals.

Meanwhile the world of trade policy is transformed since 2016, negatively. The US has essentially declared its national interests to be more important than global rules, while the EU wants to act unilaterally as the global regulator. In both, the climate crisis is being used as an excuse to reintroduce protectionist measures threatening economic damage and global stability.

Expectations of what a UK outside of the EU could achieve were exaggerated, but nonetheless the country could be doing a lot better in its trade policy. There is no good reason for such tensions as exist with a broad range of frustrated stakeholders, the absence of clear purpose on UK strengths such as services, or the defensiveness that seemingly takes pride in secrecy and resistance to proper scrutiny. Adjustment time was inevitable, but six years should have been enough.

UK Trade Policy needs a reset, and three foundational principles can help achieve this:

Embracing the complexity of the modern inter-dependent economy. Trade policy needs to achieve multiple aims including economic growth, domestic distribution, tackling the climate emergency, and supporting international relations, based on a sophisticated understanding of modern supply chains, economic strengths and weaknesses, geopolitics, and levers available to government. The new UK trade policy should work across the public sector in particular with regulatory, migration, and foreign policy, and with fellow mid-sized powers, all aligned to a revamped industrial strategy.

Understanding that results will be incremental. No single trade policy instrument is likely on its own to deliver more than marginal economic benefits. All policies will have costs as well as benefits, and that therefore multiple actions must be grounded in a comprehensive strategy and a deepened understanding of how to measure results.

Delivering with professionalism, above all pursuing the complex choices of UK trade policy in a true partnership with all relevant stakeholders including business, consumers, NGOs, parliament, and devolved governments. The UK should be gradually deepening expertise of all of those involved, discussing the rationale for inevitable choices in a way that strengthens the quality of decisions, and treating implementation of existing arrangements as important as delivering new ones.

Within such a framework, there will in turn be numerous individual actions taken, for example targeting trade growth with key partners, ensuring regulatory changes take into account trade costs, and removing official hostility in visa applications. These should build on the UK’s diverse but not universal strengths across manufacturing and services, working with those delivering trade.

Optimism in the UK’s economic prospects has been fading. The allure of the simple answer must be resisted as absolutely the wrong approach to restoring stability, and instead trade policy needs to show a country attractive to investors through a renewed ability to successfully navigate complexity.

This paper has benefitted from extensive discussions with ECIPE colleagues, UK stakeholders, and trade policy experts in different countries grappling with similar challenges.

1. Introduction

Control of UK trade policy was widely considered a key benefit of the UK leaving the EU. This has subsequently meant new Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) being signed with Australia and New Zealand, with membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and an India deal possibly following in 2023.

Focusing on FTAs as a success measure is understandable but limited as a long-term policy. The majority of UK trade is already covered by them and they arguably do little for a services superpower such as the UK. Their primary focus on tariff reduction is also outdated in an age when regulations are the main barriers to trade, and multiple factors considered in trade policy.

UK trade policy must find a broader purpose. This paper examines the context and challenges in chapter 2 and outlines potential solutions in Chapter 3. It isn’t quantitative and does not lay out detailed sectoral policy recommendations. Taking a broad view of the policy challenges of constructing a modern trade policy in complex, changing global circumstances, it rather provides a new framework of thinking for UK trade policy in what are changing times globally.

Although the UK has faced the unique challenge of establishing a trade policy framework from scratch since 2016, there is read-across for other economies contemplating a new period in global trade. Since 1945 we have seen two eras, the first running to the 1980s focusing on multilateral tariff reduction, the second extending partially into services and regulatory barriers through primarily bilateral agreements. While work was not completed, many economic gains have been realised.

- Flows of goods and services across borders is broadly accepted;

- Trade in goods grew dramatically and trade in services and ideas is now following;

- There is an extensive web of international agreements facilitating trade;

- Extensive supply chains deliver a greater range of goods and services than has ever previously been experienced.

The contours of the new world of trade are yet unknown, and some of what is now taken for granted is at risk. In particular citizens are increasingly demanding policies that are in effect contradictory, such as wanting wide consumer choice and extensive domestic production, widespread regulation and affordable goods and services. Satisfying these demands requires a mature UK trade policy to move past the often-shallow debates of Brexit into more effective identification and support for UK interests in collaboration with stakeholders.

2. UK Trade Policy Context

2.1 The New Global Context is Problematic for the UK and Other Mid-Sized Powers

For the first time since 1945, global trade liberalisation is not the primary purpose of trade policy[1]. What started with the formation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1947, in which successive rounds of talks brought tariffs down as new members joined, followed by the formation of the WTO in 1995 and a wave of Free Trade Agreements, is for the time being halted. That is the deliberate choice of the UK and its primary allies, who were crucial to this history.

The UK chose a high-trade-barrier Brexit. The USA under Presidents Trump and Biden have taken multiple actions that clearly breach WTO rules, as well as preventing the functioning of the appellate body. They have shown declining interest in bilateral trade deals which they believe are bad for US jobs particularly in the now crucial states known as the rust belt. In their place is coming informal cooperation and dialogues, and this does not seem likely to change much in the coming years.

The EU approach of ‘Strategic Autonomy’ seeks to unilaterally set global rules in areas like climate change and supply chain due diligence, as well as responding to perceived coercion. Like the US and China, it wishes to support manufacturing with subsidies particularly through a low carbon transition. The concept of weaponised interdependence, in which the major powers use vulnerabilities in supply chains to strengthen their own position at the cost of others, is spreading[2].

There was never the deliberate hyper-globalisation suggested by free-trade critics, as all countries maintained policy space, such as protecting the NHS, US Buy America rules or diverging regulations. But the current situation, of flagrant challenge to global trade foundations and an emerging subsidy war benefitting the largest economies, is of a different order, and a particular challenge to the middle powers of the global economy like the UK who rely on stable rules.

This is however just the political context. Trade is carried out predominantly by private sector companies, and changed fundamentally across the world from 1990 to 2008, driven by technology and domestic political decisions reducing direct state intervention in production. The results of this change have been dramatic yet under-appreciated, and included the following:

- Composition of trade moving from final product to intermediates;

- Shrinkage of factories that produced all elements of a product to final assembly lines;

- Replacement of direct supply restrictive regulations with those setting competitive rules;

- Private standards used by major companies growing alongside state regulation;

- Growth of global value chains for both goods (e.g. cars, pharma) and services (e.g. international universities, major sporting events, IT platforms).

Failing to comprehend these changes has been an issue for UK governments before the Brexit referendum vote and since, driving as they did both disenchantment in former manufacturing areas, and why there is no easy global deregulatory path. Similarly, they have been reasons why the UK’s trade policy agenda since leaving the EU has appeared so out of touch with its times. That the UK government has been right that countries should benefit in aggregate from open trade has been less indicative of the times than saying this while presiding over a huge rise in trade barriers.

2.2 UK Trade Policy Focus on Free Trade Agreements is Running out of Targets

While there have been a few other initiatives such as establishing freeports, Free Trade Agreements have been central to UK trade policy since 2016. This was for understandable political reasons as a demonstration of progress. Independent control of trade policy had been a frequently mentioned ‘Brexit dividend’, interpreted primarily as meaning FTAs geared to UK interests.

Starting with replicating existing FTAs to which the UK was a party as an EU member, the vast majority were completed on similar terms, an achievement considerably helped by the elongated Brexit timetable. Some including South Korea and Canada require renegotiation now under way, a handful were not completed[3], and for most European countries an FTA is an economic downgrade compared to previous integration arrangements between the EU and neighbours.

Since leaving the EU, FTAs were completed with Australia and New Zealand, essential building blocks towards joining the 11-country Comprehensive and Progressive agreement for a Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which has become a key priority, notwithstanding existing bilaterals with 9 members. While the economic benefit seems slim, the opportunity to be part of a grouping with many like-minded countries has value. Accession along with an India FTA may come in 2023.[4]

These priorities arose in the absence of a US FTA that had been central to the case made by many Brexit supporters. Discussions that took place in the years before 2016 particularly between free-trade supporting Republicans and leading Conservative politicians to build such a relationship was overtaken by the election of President Trump in what should be seen as an early blow to Brexit.

Without a US FTA, and given that similar arrangements also seem impossible with China and Taiwan for different political reasons, this leaves the possibly addressable market for new FTAs as limited, and difficult. Indeed, only 6% of UK trade would be left that is not covered by some form of arrangement. Based on this, FTA negotiations cannot be central to UK trade strategy going forward.

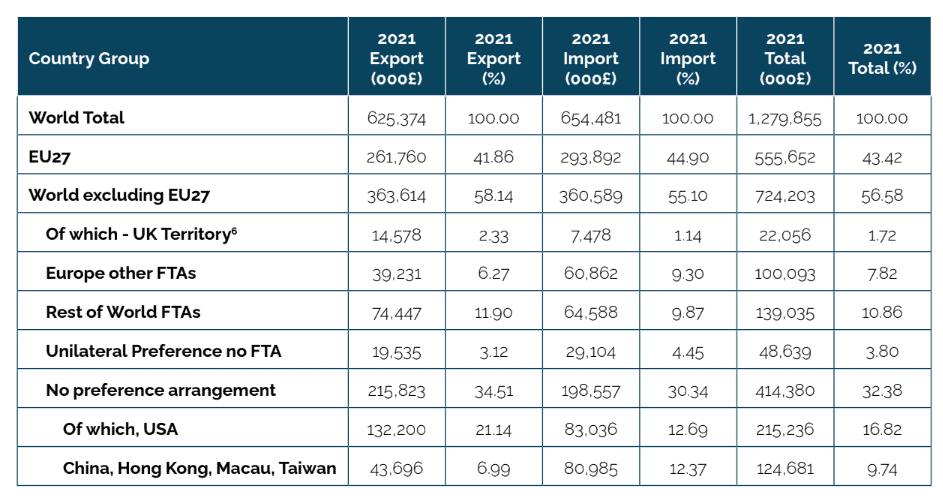

Table 1: UK goods and services trade – coverage by trade agreements Source: Calculations by author based on ONS UK Total Trade By All Countries, Non-Seasonally Adjusted, Q4 2021.

Source: Calculations by author based on ONS UK Total Trade By All Countries, Non-Seasonally Adjusted, Q4 2021.

2.3 FTAs are not a Good Fit for the UK

In broad terms, the UK is a services exporter and a goods importer. In 2021, 48.5% of exports were services; it rises to 53.8% for trade with non-EU countries. By contrast, 73% of imports were goods. The services figure might be considerably higher once the services components of goods sales are considered. The UK has been called a “services superpower”, and is the world’s second largest exporter. By contrast, though still a significant goods exporter with particular niche strengths such as aircraft engines, sports cars, and Scotch Whisky, the UK is at risk of slipping out of the global top ten.

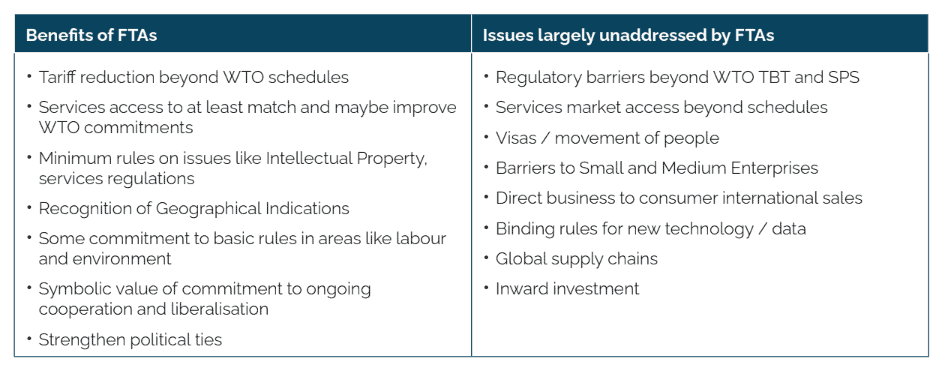

Considering in detail FTA strengths and weaknesses shows that even after the content has been bolstered in recent years they have considerable weaknesses, particularly in UK areas of strength:

Table 2: Strengths and weaknesses of FTAs

Essentially, while FTAs have importance, they no longer tackle the greatest modern barriers to trade. This is one reason for a common perception that Australia and New Zealand FTAs were unbalanced in almost completely removing UK agricultural tariffs[6] while offering little new to UK exporters in return. Lower import costs are a trade policy benefit, and time will tell if the risk in particular to Welsh and Scottish lamb production is realised, but the risk comes more from a narrative suggesting UK desperation to gain FTAs as a Brexit benefit regardless of the particular content.

Many other trade policy tools exist, treaty based such as Mutual Recognition Agreements and Bilateral Investment Treaties, more informal such as digital trade agreements and trade diplomacy including tackling market access barriers, or emerging such as on raw materials. The UK already does much of this, though impact and take-up are not currently measured and often seems limited.

Some UK strengths such as education owe very little to trade rules, and domestic measures such as more generous visa policy could have a major impact, if it is politically acceptable. Attracting inward investment that places supply chains within the UK is similarly not fully linked to trade policy. Such options should be some reassurance to the UK given major powers undermining the WTO. None however has the brand of the FTA, on which governments are measured, and whose symbolic value of seeking close relationships may provide business with confidence to invest. This suggests the need for more than just technical agreements if FTAs are not to be a major future policy tool.

Looking to the future though it seems fair to say that FTAs and even the WTO should only be a part of a successful trade policy, that the UK will need to use a variety of methods suitable to its particular strengths and objectives. Finding these will not however be straightforward.

2.4 Growth Needed, Other Policy Challenges Cannot be Ignored

UK economic performance has been poor since the global financial crisis of 2008, and this is forecast to continue. Trade policy must as its first priority thus support growth and well-being, with openness central. However, there are other considerations that voters now expect trade policy to consider, notably the climate emergency and emerging issues around supply chains and economic security.

Supporting growth through trade policy requires deep knowledge of the UK economy, current and projected. This would usually come via an industrial strategy, so that for example FTAs can include appropriate rules of origin for particular products. However, the UK faces a peculiar issue in that its economic strengths are often unpopular, whether defence manufacturing or finance, as well as joining global trends romanticising mass manufacturing employment that is unlikely to return.

Focusing on manufacturing as compared to known services strength could at worst lead to the UK still struggling in the former, but also risking being overtaken in the latter. This becomes even more apparent when looking at examples in two policy areas traditionally considered separate to trade, but which are as already discussed are essential to it in the 21st century: visas and regulations.

Obtaining work visas for the UK is burdensome and sometimes hostile, which in the past has even affected official government meetings with business from other countries. Meanwhile at a policy level, education services that bring thousands of foreign students to the UK every year are seen as negative by some. The UK’s failure to grow is less surprising given such attitudes.

Regulatory policy is just as confused. To trade, we need to meet the regulations of others, but UK politicians continue to talk as if diverging from others approaches is cost free and potentially of major benefit. If we want to participate in the supply chains which are such a significant percentage of world trade, we cannot be so reckless. As a relatively small market the UK needs to be thinking that divergence dividends, however attractive they sound, are probably unrealistic in many areas. The opposite may in fact be the case, that regulatory stability and competence are major attractions.

The emerging global concern is economic security, particularly with regard to China, driven by extensive private sector supply chains. Some of this is simple protectionism dressed up otherwise, but governments do need to better understand any risks from being dependent on trade in general, or single suppliers in particular. Yet, one should equally be careful not to declare the end of globalisation or openness, since companies will always account for the vast majority of trade, and combine intermediate goods and services from across the world to deliver consumer demands.

Demands regarding for example environment, labour, or specific countries equally cannot be ignored in a democracy. The power of trade can be used as a tool for pursuing many policy goals and governments need to think of how best to balance these with openness. It is however much harder for the UK to act unilaterally than the EU or US, but just following their actions such as on China may also be damaging. However, the UK should not return to pre-2016 discussions of either EU membership or a US alliance to challenge EU regulatory supremacy. Circumstances have changed.

There are many other factors to consider, from digital trade to local production. Given all of them, it is increasingly unclear what trade liberalisation even means or can be measured, as compared to the easier world where tariffs could just be reduced. Governments must navigate this complexity, knowing their actions will favour some business and other interests over others, and be ready to explain that to maintain support. As such, a trade strategy is needed that recognises and responds to such complexity, not one that imagines it away through instruments like FTAs.

[1] https://www.iisd.org/articles/policy-analysis/multipurpose-trade-policy

[2] https://uc.web.ox.ac.uk/article/henry-farrel-and-abraham-newman-weaponized-interdependence

[3] Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Algeria

[4] https://ecipe.org/blog/2023-brexit-and-trade/

[5] Crown Dependencies / Overseas Territories

[6] The UK applied average tariff for agricultural goods is 10%, for industrial goods 3% (source: WTO)

3. An action plan for UK Trade Policy

With one of the largest trade policy teams globally, the UK government has officials working on many subjects discussed. However, this has yet to translate into a coherent comprehensive policy. While partly understood given the scale of the challenge, this leaves the UK without a clear approach on far too many issues, such as subsidies, a low carbon trade policy, or trade with China.

What is missing is a framework on which substantive trade policy recommendations can be built. Putting this right needs to start with understanding what principles should underpin actions at a time of complexity and change, upon which decisions can be developed. These need to be developed with stakeholders in a refreshed relationship that recognises this has been a particularly weak part of the UK’s development of its trade policy capability since 2016.

3.1 Define the Principles of UK Trade Policy – Recognising its Complexity

Even focusing only on economic objectives, few other measures had a wider policy coverage than a Free Trade Agreement. Given other goals which can be delivered through trade, and other possible tools, all departments of government are affected. Tariffs, customs, and regulations are at the heart, but the UK-Australia chapters also include for example Intellectual Property, animal welfare, innovation, consumer protection, development, and gender equality, though not always with firm commitments. Realistically, no ‘back to basics’ approach is possible amid such complexity.

Trade policy is carried out by government on behalf of stakeholders with widespread demands, including from business, campaign groups, trade unions, devolved governments, and consumers, that cannot all be met. Choices between them are inevitably political, and whether it is demand for local manufacturing, immigration, visas, there will always be issues, disagreements and contention, which must ultimately be discussed by Parliament arbitrating all of the interests.

Considering trade policy solely in terms of the impact on exporters, as is traditional, is therefore an extremely unhelpful, overly simplistic prism. Notional economic benefit is broader but also limited. Increasingly, trade policy must demonstrate what a country stands for, and how the government is seeking to meet broad policy goals. This is in turn in line with nature of commitments made in a treaty, which as the UK has found with the Northern Ireland Protocol should not be entered lightly.

At the foundation of trade policy should therefore be a stable, medium-term, cross-party approach, much as was the case in the UK prior to 2016. The country has an advantage, not yet taken, in a broad consensus existing, albeit one that has been obscured by the loudest voices being the most extreme. This encompasses broad support for open trade and investment with all countries subject to suitable rules that make this fair and sustainable[1].

Greater openness than either the US or EU should not therefore be confused with unrealistic notions of ‘pure’ free trade ignoring for example environmental or agricultural concerns. The UK believes in a balance leaning towards openness, underpinned by strong global institutions such as the WTO, and work with like-minded countries.

A trade strategy that builds on this notional consensus to provide direction for many of the detailed trade-offs in practise is the essential first step towards a more mature UK trade policy. Also binding departments and framing stakeholder engagements, content should elucidate around the following:

- Open trade delivers prosperity, more competitive businesses, better products and services for consumers, and higher wages and better conditions for employees, as well as facilitating solutions to global issues such as the climate emergency;

- Modern trade is however always subject to fairness conditions, the balance of which must be discussed, these include development, environment and labour, but will be extensive for example from animal welfare to domestic skills;

- Similarly, there are choices to be made between seamless trade in goods and services and other policy objectives such as regulatory independence, climate change, developing country preferences etc, while also considering the context of UK as mid-size trade power;

- Multiple tools are available to governments facilitating trade and investment by businesses, but the fundamental basis are strong international institutions and rules covering trade, and the UK should work with like-minded other countries to retain and strengthen these as far as possible at multilateral and plurilateral levels;

- Participation in global and regional supply chains is essential to all economies, suggesting the need to provide good conditions for inward investment in productive capacity;

- UK economic security is unlikely to be delivered by direct government intervention in supply chains or investment, but monitoring of the economy and trade should be improved including in particular for services, where providing reliable figures should be a priority;

- Trading globally starts with good relations in our own neighbourhood and among established allies, as these are the easiest countries in terms of culture and cost, and with agreements we already have, which we should ensure are delivering benefits;

- Trade policy must be aligned with industrial strategy, such that it reflects actual priorities and strengths, making particular efforts to ensure agreements benefit the diversity of the UK economy including often forgotten sectors such as culture, broadcasting, and universities;

- Recognising that regulatory policy is an essential part of trade and that divergence is likely in general to cost more than the benefits, aiming for global best practice and cooperation should be the starting points and the basis for mutual recognition arrangements, where diverging the impact on trade should be evaluated along with other issues;

- For data in particular the UK should seek to balance openness and privacy in seeking pragmatic solutions supporting consumers and business;

- Unilateral actions can generate more trade, and easing visa processes for business visitors, and recognising the regulations of others without reciprocation are examples of what could be considered – indeed given these are essential parts of trade, a more effective way to handle inter-government tensions is required;

- A level playing field for imports and domestic production should be emphasised, this may involve restrictions based on production and process methods, and a strong trade remedies framework against unfair competition;

- A single government department should cover both EU and non-EU trade relations, with cross-departmental decisions facilitated by a dedicated Cabinet Office team and committee;

- Reporting is an essential part of incentivising delivery, and will be strengthened by it being carried out independently of government;

- Implementation is just as important as new agreements, and there should be commitment to reporting on how trade is contributing to the UK economy to help drive improvements.

The complexity of issues individually and collectively makes strategy difficult, and some ongoing evolution is likely to be needed. Ultimately, though, good governance requires this as opposed to reconsidering the range of issues for each individual decision.

3.2 Implement Based on Relevant Targets – Understanding Results will be Incremental

In trade policy generally, there are no longer simple policy solutions that will significantly boost trade and investment on their own (given the political complexity, this includes for the UK rejoining the EU or Single Market). A balanced set of actions to further economic and wider interests should however deliver incremental economic value, however, as well as tackling other challenges.

A starting point are the traditional trade policy actions of all developed country governments, for which arguably the sign of a maturing UK will be when they are seen as business-as-usual:

- Implement existing Free Trade Agreements and other tools including regulatory cooperation effectively to benefit policy interests, seeking to deepen them where this is possible;

- Resolve trade barriers faced by UK business across the world, typically mostly around discriminatory access conditions, regulations and business environment, also including ensuring effective domestic processes such as at the border;

- Develop export plans in joint teams with stakeholders, with dedicated global government resources sufficient to make an impact including in training global staff in trade intricacies;

- Support efforts to retain effective global trade rules at the WTO, to include participation in plurilateral initiatives such as the interim appellate body that the UK has so far not joined;

- Seek new agreements to facilitate trade supporting UK business, aligned to a renewed industrial strategy, these should include areas such as the low carbon transition, digital, professional qualifications, food, visas, and investment facilitation;

- Attract inward investment recognising the need that this will at times require various forms of government support, but within global rules;

- Provide preferences to developing countries that assist them to grow through trade;

- Protect UK business from unfair competition.

Much of this is already done, but all could be improved, particularly through doing so on an open and collaborative basis with all stakeholders ultimately represented by Parliament, backed up by rigorous analysis set out in an Annual Trade Report. Setting some targets around this activity will focus attention, though this will also need a commitment to improving measurement metrics:

- An overall reduction of trade barriers faced by business over the course of a government;

- Services contribution to the UK economy given its importance;

-

Plans to deepen relations with the UK’s 25 most significant trading partners, through various means including ministerial summits, intensive work with posts.

Such a workplan would stabilise UK trade policy operations but seems insufficient for future challenges particularly given the hit to competitiveness suffered from recent political instability and erecting trade barriers to integrated neighbours. UK companies face higher barriers to trade than each of them, which has disrupted supply chains and affected SME exports in particular.

More discussion will be required on the issue of EU and broader European trade relations, where Brexit debates since 2016 have arguably demonstrated that there is no optimal relationship for long term commitments. Equally, there will be suspicion from the EU as to the UK seeking to return to any formal structures such as the Single Market. Recent rebuilding of political relations would seem an essential first step, followed by a more realistic view of options and constraints, and finding ways which work for both sides to reduce barriers. Without reopening the fundamental basis of the UK’s relationship with the EU, there are still many improvements that can be sought. In particular, this means rethinking the dominant regulatory narrative that independence is best, which does not work well for a trading country, particularly one next to a regulatory superpower. This would mean:

- Accepting that the UK will seek to align with the regulations of major markets for many products and services, in such a way as to maximise UK market access, supported by formal regulatory cooperation, and underpinned by robust impact assessments;

- Focusing on the rules passed by the EU and others likely to affect UK trade, and seeking to influence them while accepting that this will be difficult;

- Increasing the priority given to trade with the entire near neighbourhood, to include non-EU countries such as Turkey, Switzerland, and Morocco;

- Targeting relatively seamless trade particularly in services, recognising that there are few models for this, and that for example digital trade agreements are currently limited;

- Considering dynamic alignment where helpful, UK unilateral action where beneficial, for example possibly in financial services, but predictability and competence in all cases;

- Understanding the need to rebuild investor confidence through broader stability, implications of which include that while Freeports are an outdated trade policy mechanism their immediate removal would also not send the right signals.

Thereafter, further evolution of UK-EU relations can be based on solid foundations. This will be necessary as the changing nature of trade has not diminished the importance of gravity.

A final cluster of actions are needed responding to emerging global challenges, that will significantly complicate the above. These include the breakdown of global trade norms in particular the US and China challenge, climate crisis, and concern about whether supply chains are sufficiently robust and responsive to local conditions which can also go under the name of economic security. Responding to these will test UK trade policy making skills, and will involve the following:

- Using a comprehensive trade strategy developed early in the lifetime of a new government to generate a shared understanding of the challenges and the parameters of the approach;

- Joining with like-minded countries seeking to protect a functioning global trade system, using the UK’s convening power to facilitate joint work where possible, while finding suitable relations with each of the US, EU and China as major trade powers who cannot be ignored;

- Recognising however that the WTO is struggling and unlikely to deliver much for immediate UK trade policy objectives, which in particular around disputes may require intensification of trade diplomacy efforts or finding alternatives;

- Defining economic security including gathering data on dependencies in areas like food, and working with business to reduce risks;

- Setting domestic policy constraints over trade and investment recognising that there have always been limits for example around the impacts on particular communities such as upland farmers, while still maintaining the general principle of openness;

- At the same time resisting in so far as possible immediate demands for intervention, which are likely to create unhelpful precedent;

- Similarly, avoiding actions placing the UK in a subsidy war with other countries that inefficient companies will exploit, or actively seeking to manage trade given complexities;

- Encouraging and developing UK strengths in both services and manufacturing more than focusing on weaknesses.

Above all, the UK government needs to be responsive to the world if it is to re-establish international respect, and pick areas of unilateral action carefully. There has been too much loose talk of leading where it is neither considered or useful. No country has all the answers, but the UK can be a contributor as well as gaining from trade policy, as long as it anchors its actions in today’s realities.

In an evolving policy environment, suggested actions are inevitably just a starting point, to be built upon in an open policy-making process including through government discussion papers.

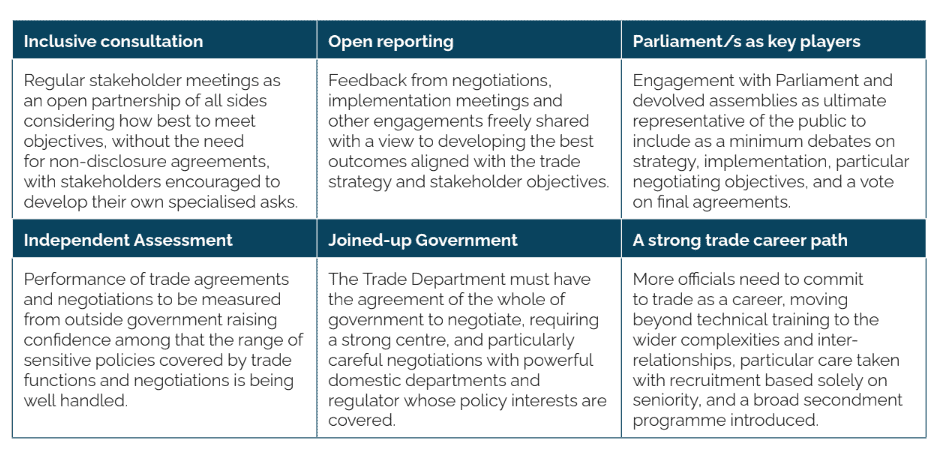

3.4 Create a new open relationship with stakeholders – increasing professionalism

Delivering this agenda while global trade politics continues evolving will require much improved government operations. Notwithstanding the steep learning curve that many dedicated officials have been through, changes are needed most obviously in attitude but also structure.

The relationship between the Department for International Trade and stakeholders is on the surface relatively constructive, but private conversations reveal a different picture sometimes verging on the dysfunctional. Experienced stakeholders complain of being ignored then consulted far too late, and that their warnings are routinely dismissed. They see the Department as too often arrogant and naïve, in general obsessively secretive, and therefore uninterested in a partnership approach. Officials by contrast see stakeholders as liable to leak any information given, whatever the sensitivity, and preferring to whinge rather than engage. Ministers ridiculously have often seen any criticism as protectionism, an unfortunate throwback to a different age.

Cross-Whitehall working has also been problematic since 2016. It is often said by trade professionals only slightly in jest that the UK Home Office is the biggest barrier to trade and investment. There is no evidently strong Cabinet Office coordination team reporting directly to the Prime Minister responsible for effectively joining-up trade and other international policy objectives. Lead negotiators do not appear empowered on behalf of the whole of government, and Ministerial statements often seem to appear at random rather than supporting particular negotiations.

The idea of trade policy as a secret function carried out only by government has been discredited some time ago, and it has been the UK government’s largest fault to date to take such an old-fashioned approach to extreme. It has prevented a team UK approach, Government is negotiating on behalf of stakeholders, not inviting them on sufferance. Equally, little in modern trade negotiations is truly sensitive given the knowledge of other countries, and the need to actually build mutual benefit. Drawing on inclusive approaches such as New Zealand’s Trade for All would be helpful, and should lead to better decisions to the complex overlapping challenges described above.

A mature UK Trade Policy function must thus ensure the following:

[1] See for example “Scotland’s Vision for Trade” at https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-vision-trade/pages/5/

4. Conclusion

Such an agenda as outlined above can feel dull when compared to the promises of the Brexit campaign and beyond, but that version of a buccaneering UK expanding trade performance through extensively customised Free Trade Agreements was never realistic. 21st century public policy in general must balance many complexities in a professional manner, and trade policy with its extensive scope is a classic example of this. Simple solutions will be inadequate almost by default.

Restoring stability and openness to UK trade policy is in any case in the grain of UK consensus opinion, as well as being the demand of business, and the expectation of countries around the world. Balancing this with meeting domestic objectives should be at the core of successful national politics, an essential foundation upon which to build.

Diminished growth does not mean an absence of UK strengths, and one key to reversal is to return to classic values rather than chasing populist fantasies likely leading to further decline. A trade policy grounded in industrial strategy, broader policy challenges, and consent can contribute to an economic recovery, even if none of the individual measures may on their own significantly move the dial.

Relationships with neighbours set against global visions have been a key part of UK policy discussions throughout modern history. These will doubtless continue, but more choices will be available from pursuing a sensible trade policy that considers the many possible choices and trade-offs in a coherent manner alongside the many stakeholders.