Unintended and Undesired Consequences: The Impact of OECD Pillar I and II Proposals on Small Open Economies

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Research Areas: Digital Economy DTE WTO and Globalisation

Summary

Corporate tax laws vary significantly between different jurisdictions. Over the past four decades, governments globally competed for business activity by lowering statutory and effective corporate tax rates. Many governments provide special tax incentives for businesses to invest and expand employment. Special economic zones often grant full corporate tax exemptions to stimulate commercial development. Corporate income tax incentives for research and development activities are common across countries’ corporate tax codes reflecting governments’ desire to stimulate innovation and business development.

While corporate tax competition is common government practice in the world economy, the OECD currently aims to curb international corporate tax competition. The OECD’s corporate tax reform proposals officially aim to address “corporate tax avoidance” and “unfairness in taxation”. The policy debate is driven by some governments’ motivation to increase revenues from taxes on corporate income. Economic impact assessments of the OECD’s current Pillar I and II proposals are still scarce. Individual governments have so far failed to conduct impact assessments or are hesitant to make their assessments available to the general public. The OECD’s secretariat expects additional tax revenues of 100bn USD annually, which are said to be evenly distributed among the 137 countries comprising the Inclusive Framework. The narrow focus on changes in governments’ revenues and the static nature of the OECD’s analysis is in various respects misleading.

This paper highlights that the proposed reforms would shift taxing powers (tax sovereignty) and economic activity away from small open economies to the world’s largest countries, of which most (currently) apply very high statutory corporate tax rates. The implementation of Pillar I and II proposals would pave the way for a global tax redistribution framework transferring financial funds away from governments that embrace free international trade and investment to the many of the world’s worst-performing governments with respect to economic openness, acceptance of the rule of law, corruption, state interventionism, and the recognition of basic human rights (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and Russia). Conversely, the OECD’s proposed corporate tax reforms would punish the world’s best performing economies with regard to economic freedoms, trade and investment openness and the rule of law (e.g. Estonia, the Czech Republic, Ireland, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland, including small city and island states, such as Hong Kong, Luxembourg and Singapore).

The reforms proposed by the OECD would have a significant impact on how much and where multinational enterprises would have to pay corporate income tax in the future. The proposed measures would therefore impact where large companies produce and invest in the future. Continued tax competition would contribute to a narrowing of international corporate tax rate differentials up to the 12.5% minimum tax threshold level proposed by the OCED. The narrowing of tax rate differentials between today’s high-tax jurisdictions, of which most are very large countries, and today’s low-tax jurisdictions would direct international and domestic investments and investment-induced tax revenues away from small countries. Estimates show that inward FDI in today’s high-tax countries would increase and outward FDI would decrease. In a symmetrical way, inward FDI in today’s low-tax countries would decrease and outward FDI would increase. Overall, the shift in effective taxing powers would undermine small countries’ relative attractiveness to international businesses and, on top of that, would induce domestic businesses to relocate to larger countries with the gravity of larger markets.

Contrary to claims made by the OECD, the implementation of Pillar I and II proposals would not improve the global allocation of capital. Global trade and investment flows would still be subject to tax competition and prevalent trade and investment barriers. The OECD’s current proposals would likely incentivise the governments of large countries to maintain long-standing barriers to trade and investment. The economic gravity of large countries may even incentivise large country governments to erect additional barriers that would restrict market access for companies from small open economies. For small open economies that are home to research- and knowledge-intensive multinational companies, the OECD’s proposed tax reforms would undermine future investments in R&D, innovation and business model development, with adverse implications for existing research clusters, education systems and high value-added jobs.

Policymakers should reconsider whether taxes on corporate income actually contribute to governments’ overall social and economic policy objectives, such as economic development, redistribution and fairness in taxation. Replacing tax systems that include taxes on corporate income by systems that rely more or exclusively on direct taxes on labour income, capital income and consumption (VAT/sales taxes) would increase transparency about the distributional effects of taxation and significantly improve governments’ tax manoeuvrability in response to citizens’ preferences for fairer taxation. A regime change towards greater use of VAT/sales taxes would also have a positive impact on global capital allocation. Companies would no longer have to pay attention to corporate tax rate differentials, while governments would have additional invectives to embrace foreign trade and investment, materialising in lower barriers to trade and investment and a more efficient allocation of global capital respectively.

1. Introduction

The OECD’s Inclusive Framework (IA), which comprises the governments of 137 highly diverse countries, discusses new international rules for the taxation of multinational enterprises. In May 2019, the Framework agreed a program of work for addressing the “Tax Challenges of the Digitalization of the Economy.” The program sets out two pillars of work:

- Pillar I aims to design new rules for the (re)allocation of taxing rights between jurisdictions. It considers several new mechanisms for profit allocation and new nexus rules. Pillar I proposals are framed as a policy remedy to corporate income that is currently not taxed in the countries where it is generated. Recent proposals indicate that the new rules under Pillar I go beyond digital companies, i.e. they will affect more companies in more industries.

- Pillar II (also referred to as the “Global Anti-Base Erosion” or “GloBE” or “Minimum Tax” proposal) aims to design a new set of rules for a minimum taxation of corporate income. It is framed as an attempt to address “ongoing risks” from corporate structures that allow multinational enterprises to shift profits to jurisdictions where they are subject to no or low taxation. Rules resulting from Pillar II would provide (high-tax) jurisdictions with a right to “tax back” where (low-tax) jurisdictions have not exercised their primary taxing rights or the payment is otherwise subject to low levels of effective taxation.

The reforms proposed by the OECD would have a significant impact on how much and where multinational enterprises would have to pay corporate income tax in the future. The proposed measures would impact where companies invest and locate in the future, impacting the revenues collected from sales taxes, labour-income taxes and taxes on corporate income. From a geopolitical perspective, the reforms proposed by the OECD would shift taxing powers and economic activity away from small countries to large, populous countries. This shift in the balance of power would impact how governments formulate domestic economic policies as well as trade and investment policymaking.

The aim of this study is to discuss major economic implications of the OECD’s Pillar I and II proposals on small open economies. The analysis will go beyond the few existing impact assessments, which almost exclusively focus on potential changes in governments’ revenues from taxes on corporate income. While the focus of this analysis will be on small open economies, the analysis and its conclusions are particularly relevant for governments that generally support good governmental institutions, the rule of law and open markets for trade and investment.

Section 2 will begin with an overview of potential economic impacts outlined by existing impact assessments. Section 3 provides an overview of key economic and institutional features of large countries and small open economies. The analytical focus will be on the Inclusive Framework’s top 30 most and top 30 least export-intensive (or, generally, trade-intensive) economies and how they perform with regard to corporate tax rates, the legal manifestation of economic freedoms, the level of existing trade and investment barriers, and the domestic state of the rule of law. Accounting for the tax sensitivity of international investment and governments’ continuing incentives for tax competition to maintain foreign investment and/or prevent divestment, Section 4 analyses the impact of a narrowing or international corporate tax rate differentials on the reallocation of FDI and FDI-induced tax revenues changes. Section 5 concludes that Pillar I and II are much more impactful than presented by the OECD and national governments.

2. Potential Impacts of the OECD’s Reform Proposals

Both the OECD’s Pillar I and Pillar II proposals have been described in rather broad terms. The impacts of Pillar I critically depend on the final design of the reallocation rules and the future definition of residual profits. For Pillar I, the OECD’s own (rudimentary) impact assessment estimates that a) effective average corporate tax rates (EATRs) are going to rise between 0.6% and 1.9%, and b) that governments of low-income (developing) countries would be the main beneficiaries of the reform proposals. The estimated effects from Pillar II are particularly sensitive to the minimum effective corporate tax threshold, which was set at 12.5%. Referring to its preliminary impact assessment from February 2020, the OECD claims that the combined effects from Pillar I and II would result in revenue gains that would be “broadly similar” across high, middle and low-income economies, amounting to some 4% of current corporate tax revenues (OECD 2020b).

Public statements and official publications demonstrate that the policy debate about OECD’s reform proposals is centred around the overarching objective to combat “corporate tax avoidance”. The narrow focus on avoidance and governments’ future revenues is reflected by recent impact assessments. Comprehensive economic impact assessments of the OECD’s reform proposals are still scarce. Those that are available merely focus on the changes in corporate tax revenues and aggregate corporate tax bills. Due to the vagueness of the latest proposals, all obtainable assessments are based on a number of assumptions, and they generally suffer from a lack of available data. Individual governments have so far failed to conduct impact assessments or are hesitant to make their assessments available to the general public. So far, the debate has paid little attention on the proposals’ effects on countries’ economic activity, investment (incl. R&D) and innovative capacities, including effects on small and open economies. Virtually no attention has been paid to the impact on the future development of the quality of governmental institutions, governments’ future incentives to increase their countries’ attractiveness for entrepreneurs and investors, and governments’ own capacities to improve the quality of infrastructure, education, professional qualifications and basic research in their countries.

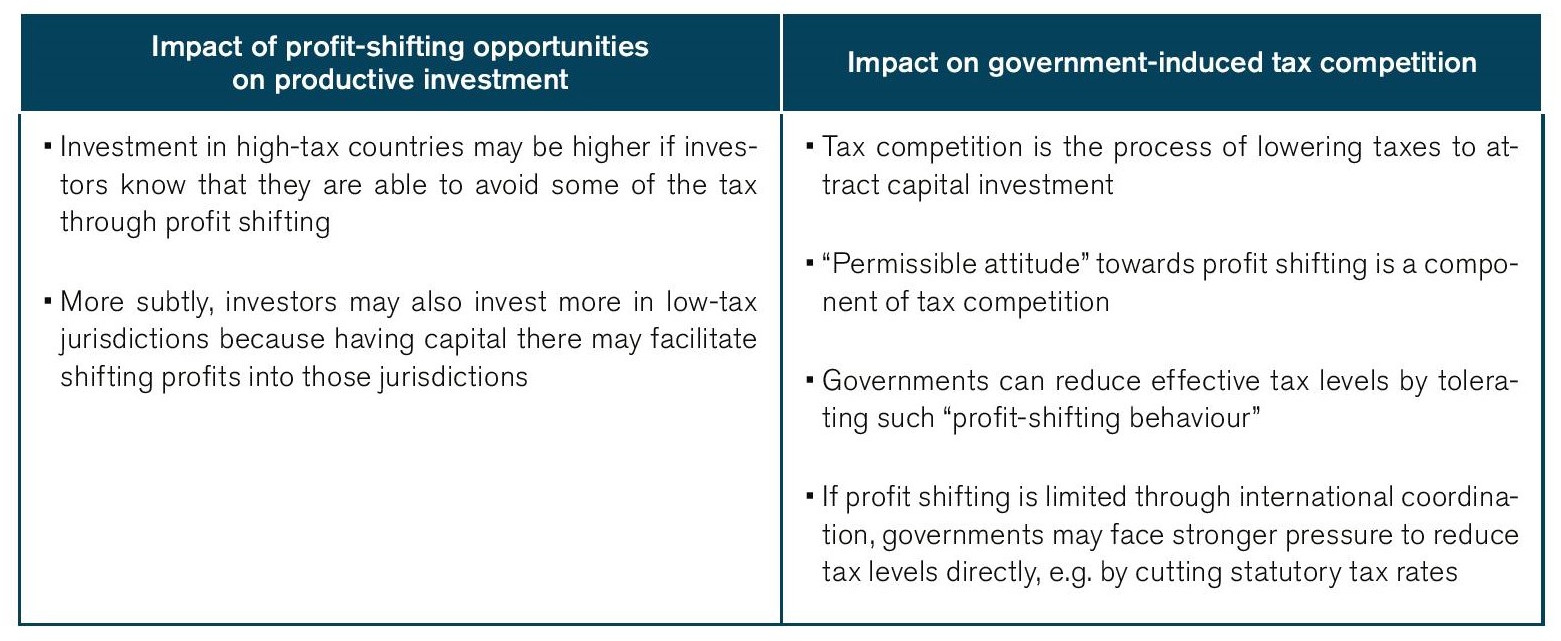

An IMF Working Paper from 2019 (No. 19/287) investigates the impact of internationally operating companies’ profit shifting behaviour on investment activities and the implications of restraints on profit shifting on future tax competition (Klemm and Liu 2019). Following the empirics as well as their own analysis, they conclude that “profit shifting opportunities unambiguously reduce the cost of capital in all countries [analysed].” It is stressed that profit shifting opportunities raise the global stocks of capital. It is concluded that “[g]iven the ambiguity of many of the findings, the recent strength of international [OECD BEPS] efforts at curbing profit shifting may appear surprising.” They also argue that a “permissible attitude” towards profit shifting is a component of tax competition and that governments are unlikely to give up on tax competition in the future.

A study published by the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation analyses the impacts of Pillar II (Devereux et al. 2020). It is emphasised that the proposals suffer from a “lack of obvious principles”. It is also argued that the proposals are inconsistent with the objective to tax corporate income where value is created. The authors point to flaws in the notion of “taxation according to the place of value creation”. It is outlined that the global decline in statutory corporate tax rates is the result of tax competition and governments’ interest to attract real economic activity and “mobile profit”. It is cautioned that tax competition will continue irrespective of an OECD agreement: “many countries […] implemented many forms of anti-avoidance rules at the same time as competing on other aspects of their tax systems,” while corporate tax revenues have not fallen considerably. The authors demonstrate that “[t]here is a clear trade-off between the aims of reducing profit shifting and supporting investment.” It is argued that Pillar II policies would increase the cost of capital, with adverse implications on overall investment activity.

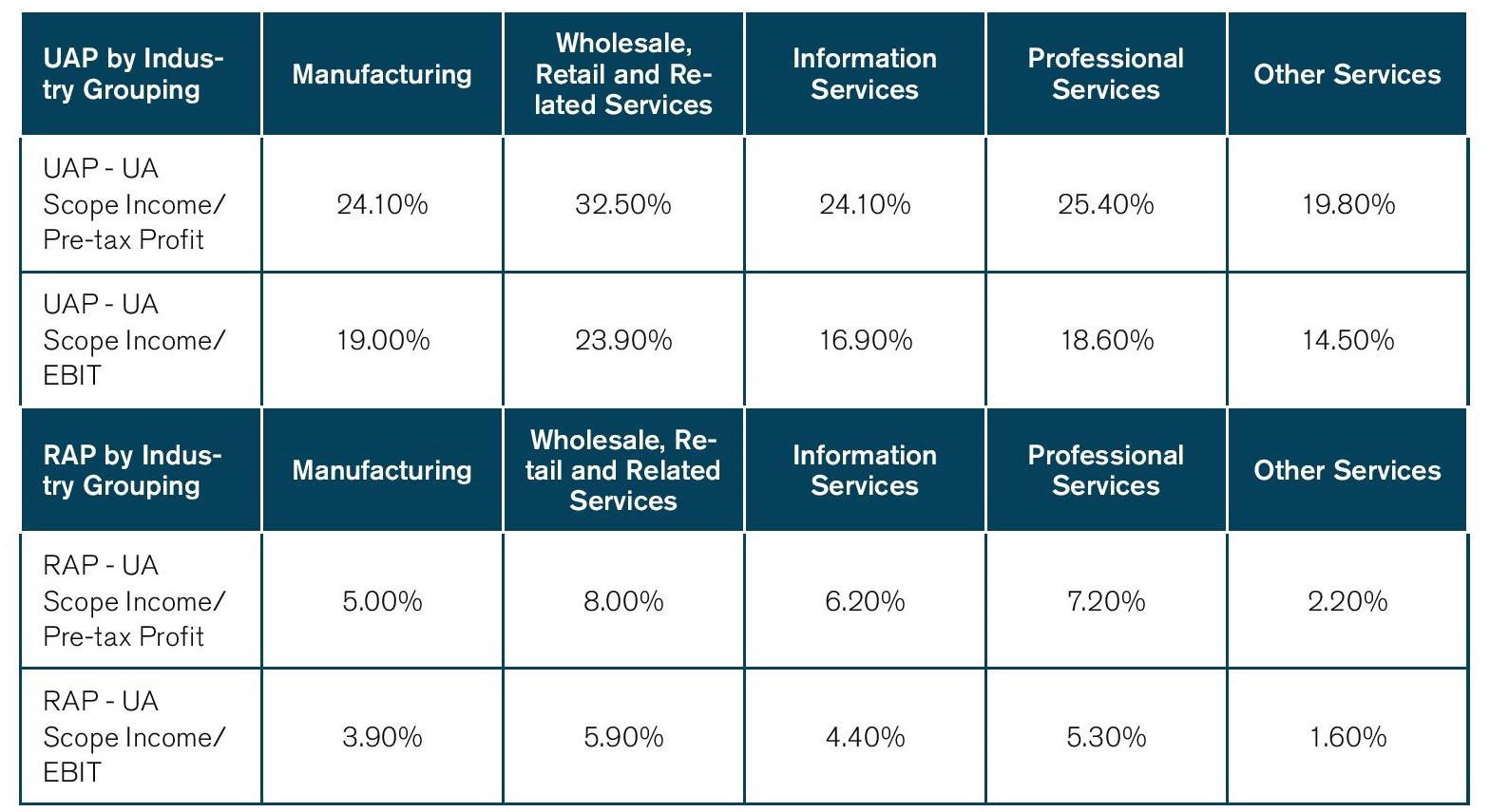

A study conducted by tax practitioners looks into the likely impacts of Pillar I, i.e. changes in nexus and income allocation rules for internationally operating companies’ taxable income (Singh et al. 2020). The authors estimate the extent of change the OECD’s unified approach will bring about. The numbers estimated indicate that the new formulaic elements of the OECD’s unified approach may directly govern the allocation of a large portion of an MNE’s pre-tax income. However, the impact on changes in the allocation of pre-tax profits and tax revenues is modest compared to the status quo. The authors highlight that existing nexus and income allocation rules grounded in the permanent establishment concept and the arm’s-length principle will continue to be relevant in the future. It is stated that “[r]umors of the arm’s- length principle’s demise may have been somewhat exaggerated”.

In a recent opinion note released by ZEW (2020), it is argued that the OECD’s latest proposals stand in opposition to the OECD’s stated policy objectives. The authors highlight that the OECD is currently pursuing a “fundamental and potentially overshooting corporate tax reform”. For Pillar I, the authors argue that the proposals would increase arbitrariness in determining the amount of profit subject to taxation and increase the risk of double taxation. For Pillar II, the authors highlight that the “proposed coexistence and reinforcement of the residence and source based taxation principle […] could also increase tax competition between OECD member states with the coordinated minimum tax level being the lower bound.” It is also highlighted that “the risk of double taxation increases if all jurisdictions try to expand their access to the tax base of multinational enterprises.” It is concluded that the OECD should focus on “indirect taxes to generate tax revenues at the location of user participation. The value added tax (VAT) is an already existing suitable tool to tax consumption in market countries.”

3. Impacts on Small Open Economies

This Section will discuss the potential impacts of the OECD’s reform proposals on small open economies. Various stakeholders report that the Inclusive Framework is not as inclusive as its name suggests. Expert opinion as well as media coverage suggest that the policy reform debate is to a large extent shaped by the governments of large countries, such as the US, China and India. The Covid-19 situation has put small country governments even more on the side-lines as it became more difficult for their representatives to participate in ongoing discussions.

The economic interests of smaller countries are at risk of being swept under the rug by a political consensus crafted by the governments of the world’s largest economies. The negative implications from the OECD’s reform initiative are likely to be strongest for small open economies, including (but not exclusively) countries that are home to innovative and internationally competitive businesses. The negative implications go beyond direct impacts on the tax burden of multinational companies and governments’ corporate tax revenues. They are also about future incentives for governments to strive for good governmental and legal institutions and a political culture that embraces commerce, entrepreneurship, and open markets in support of economic development and high standards of living. This section continues with a discussion of characteristics of small open economies, followed by an outline of major institutional characteristics of countries comprising the OECD’s Inclusive Framework.

3.1 Characteristics of “Small Open Economies”

The term “small open economy” is frequently used in the economic literature. The expression is referred to characterise a set of countries that are, on aggregate and compared to other countries, “too small” to affect world interest rates, world prices or labour incomes.[1] Similar considerations apply for international political relations. In international economic diplomacy, the political influence of a government is generally based on the economic clout of the country this government represents. Political influence is positively correlated to a country’s aggregate purchasing power, its overall production capacity and the amount of capital available for investment.

More generally, a country can be considered an “open economy” if its government allows its citizens to engage in international exchange, i.e. trade across national borders. Exchange is largely about trading goods and services, but can be more intangible, e.g. exchanges in procedural know-how, managerial practices and technological knowledge. Another important feature of an open economy is that its government allows citizens to invest their savings abroad and foreigners to invest in the domestic economy, which in economics lingo is described as free flow of capital.[2]

Economic history demonstrates that countries whose governments embrace international trade and investment also benefit from knowledge spillovers, which positively impact on the quality of governmental institutions and the rule of law. In addition, exposure to international trade and investment improves, over time, the effectiveness and efficiency of domestic market regulations, the ease of doing business and, as a result, economic development, structural economic change and standards of living.

For the purpose of this paper, it is useful to distinguish economies on the basis of their involvement in the international economy. A traditional measure of “trade openness” is the ratio of trade to GDP (overall economic activity in a given year). A relatively high trade-to-GDP ratio is a sign of a more open country. The trade-to-GDP ratio also functions as a rough indicator of how much a country’s citizens and companies engage in international trade and to what extend they are participating in the international division of labour. Economic evidence demonstrates that as individuals and companies engage more in foreign trade (exporting, importing, investing), the more they and their counterparts benefit in terms of productivity growth and income generation.

The world’s most open economies in terms of trade/GDP, imports/GDP and exports/GDP are small – often very small – economies. The OECD’s Inclusive Framework is generally comprised of countries, which show a high variation in terms of the state of economic development, openness to foreign trade and investment, the state of the rule of law and the quality governmental institutions. As concerns trade openness, Inclusive Framework countries are characterised by a high degree of heterogeneity with regard to their participation in international trade, both in exports and imports.

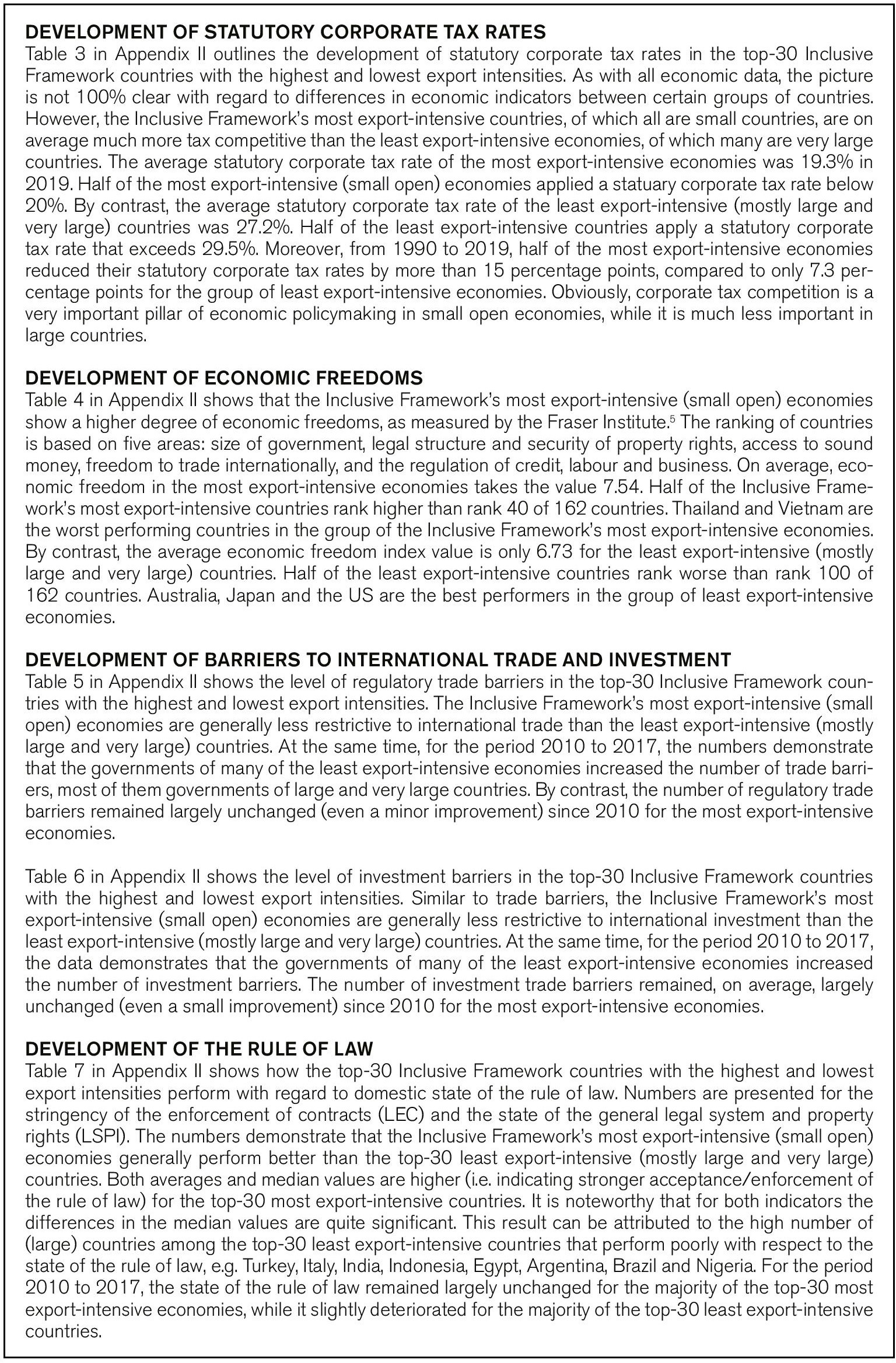

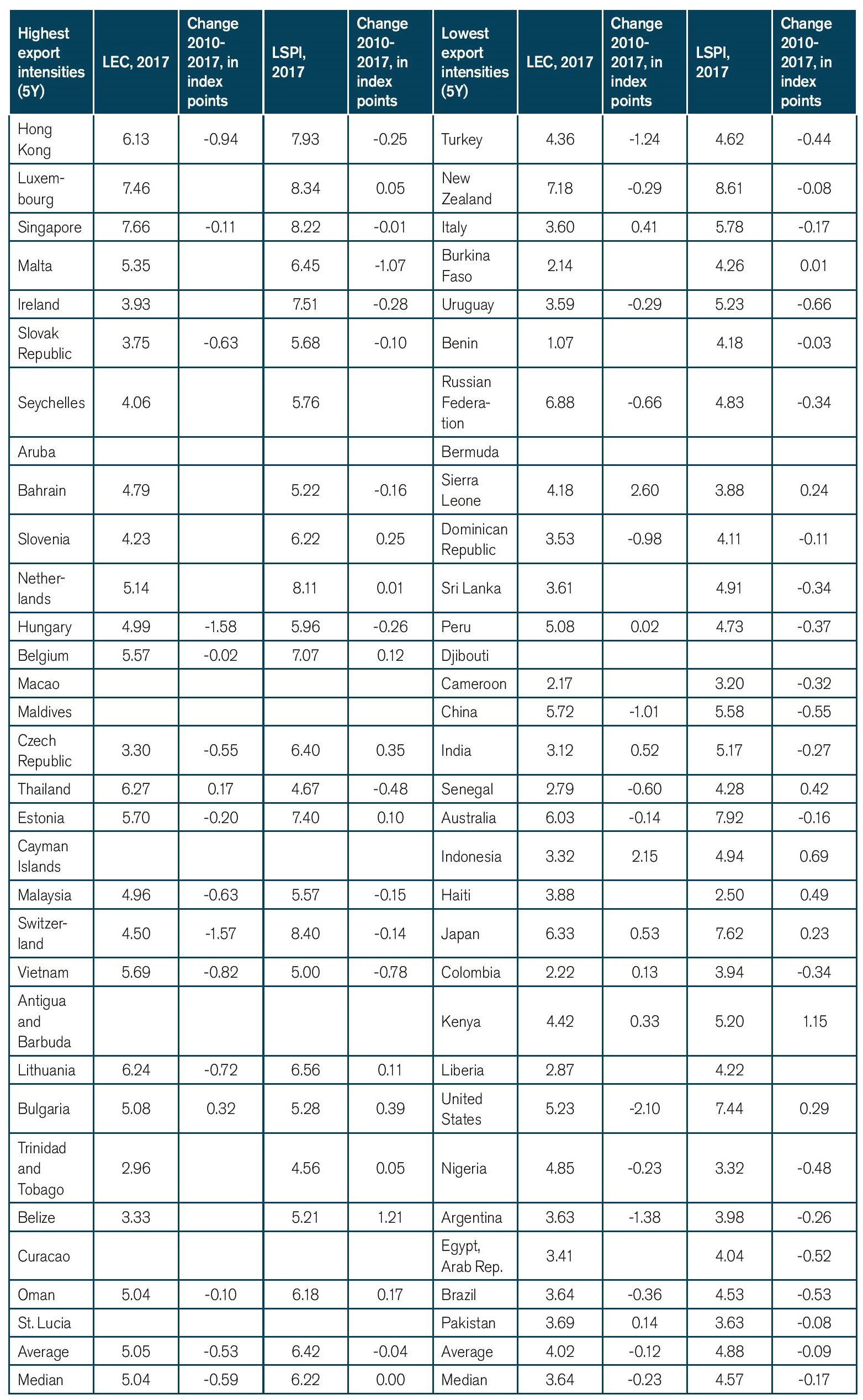

Figure 1 shows the Inclusive Framework’s top-30 most export-intensive and the top-30 least export-intensive economies for the past 5 years. The numbers show that the Inclusive Framework’s 30 most export-intensive economies are generally relatively small countries, e.g. Estonia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland, Thailand and Vietnam, and very small city and island states, e.g. Hong Kong, Luxembourg and Singapore. By contrast, the Inclusive Framework’s 30 least export-intensive countries comprise many of the world’s largest countries, including Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, and the US.[3] Many more Inclusive Framework countries, of which most are also relatively small in terms of population and overall economic output, are somewhere in the middle range of trade, export and import intensities.

It should be noted that the export-intensities depicted in Figure 1 generally reflect countries’ dependency on international trade. Due to their sheer size, large countries are generally more self-sufficient with regard to natural resources and the products and services that are or could be produced in these countries. In addition, due to market size effects, large countries are much more attractive to investors than small countries.

Figure 1: Top-30 “Inclusive Framework” countries with the highest and lowest export intensities

Source: World Bank data. Note: export intensities have been calculated on the basis of 5Y average export to GDP ratios. The numbers depicted in the chart represent the distance from the sample mean, which is 0.49 for the countries participating in the Inclusive Framework.[4]

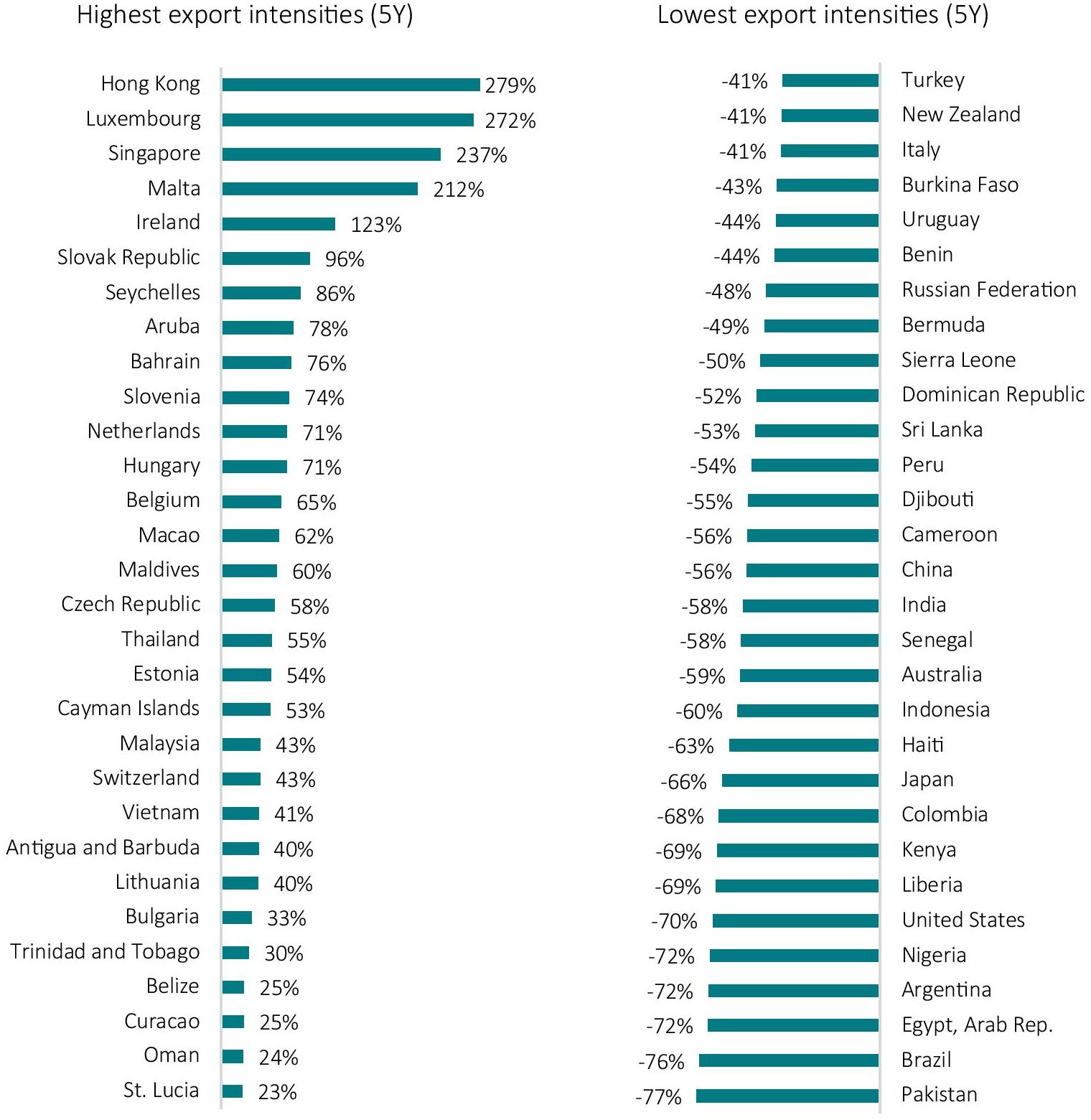

A large body of economic research demonstrates that country size matters most for foreign investors. A country’s population size is generally positively correlated with market size. Market size is the key determinant of FDI, as firms can expect to benefit from higher economics of scale as well as a larger potential demand (ECB 2017, World Bank 2011). Figure 2 outlines several aspects that are also critical for foreign investors, amongst them the quality of legal and governmental institutions and regulations governing international trade and investment.

As will be shown in more detail below, the Inclusive Framework’s most export-intensive countries (as outlined by Figure 1) are generally much more tax competitive than large countries, much freer with respect to domestic regulations and at the same time much more open to international trade and investment. In other words, the degree of “trade and investment dependence”, on the one hand, and “self-sufficiency”, on the other hand, is reflected in domestic regulations for commerce and policies governing trade and investment.

Figure 2: Key determinants of foreign investment

Source: World Bank (2011).

3.2 Corporate Taxation and Economic Freedom in Inclusive Framework Countries

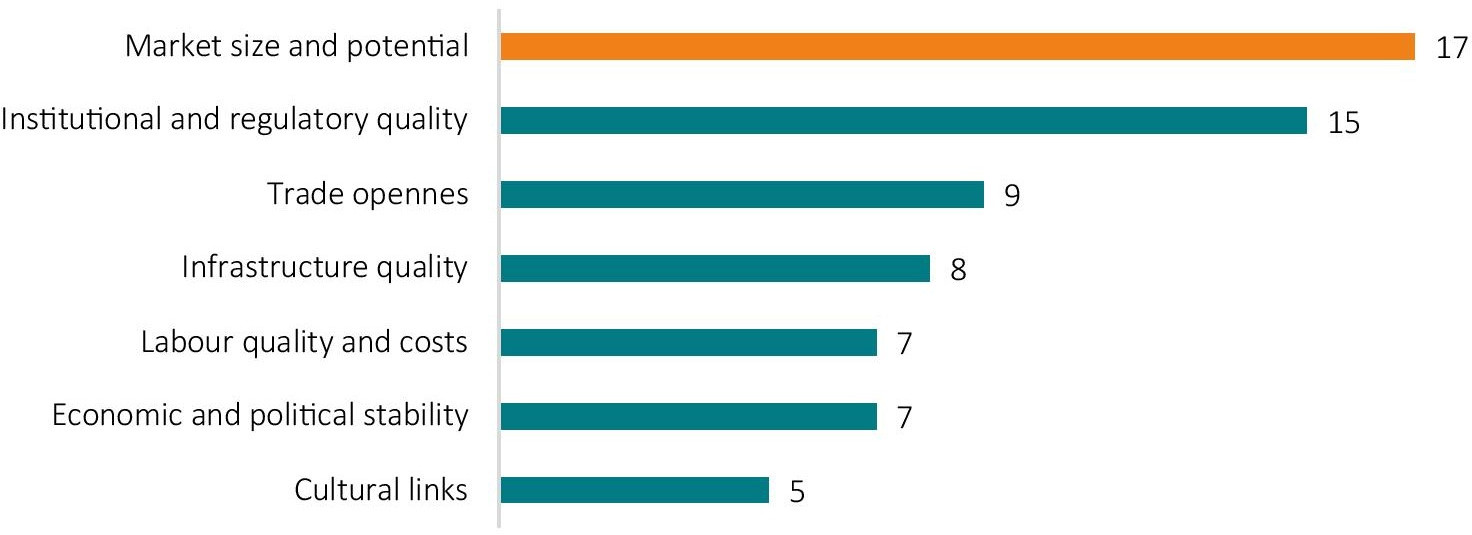

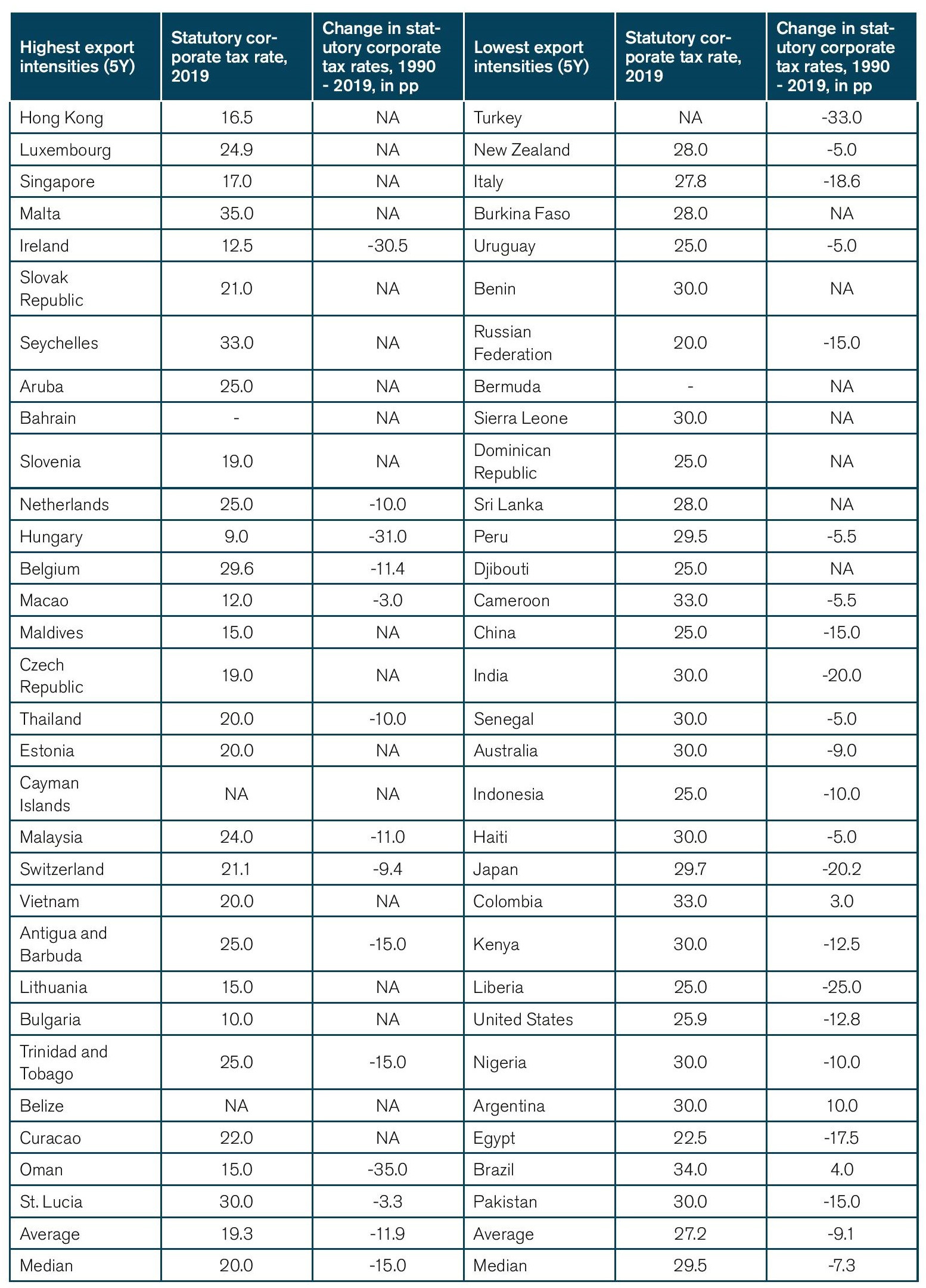

Empirical data indicates that governments of large economies have less incentives to compete for business activity on characteristics of the corporate tax system, e.g. the headline corporate tax rate. Indeed, the Inclusive Framework’s most export-intensive countries, of which all are small countries, are on average much more tax competitive than the least export-intensive economies, of which most are large and very large countries. The average statutory corporate tax rate of the IF’s most export-intensive economies was 19.3% in 2019. Half of the most export-intensive economies applied a statutory corporate tax rate below 20%. By contrast, the average statutory corporate tax rate of the IF’s least export-intensive countries was 27.2%. Half of the least export-intensive countries applied a statutory corporate tax rate that exceeded 29.5% in 2019. Moreover, from 1990 to 2019, half of the most export-intensive economies reduced their statutory corporate tax rates by more than 15 percentage points, compared to a median of only 7.3 percentage points for the group of least export-intensive (large) economies (see Figure 3 and, for a detailed overview, Table 3 in Appendix II.

Figure 3: Top-30 “Inclusive Framework” countries with the highest and lowest export intensities, 2019 statutory corporate tax rates and 1990 – 2019 changes in statutory corporate tax rates, median values

Source: World Bank and Tax Foundation.

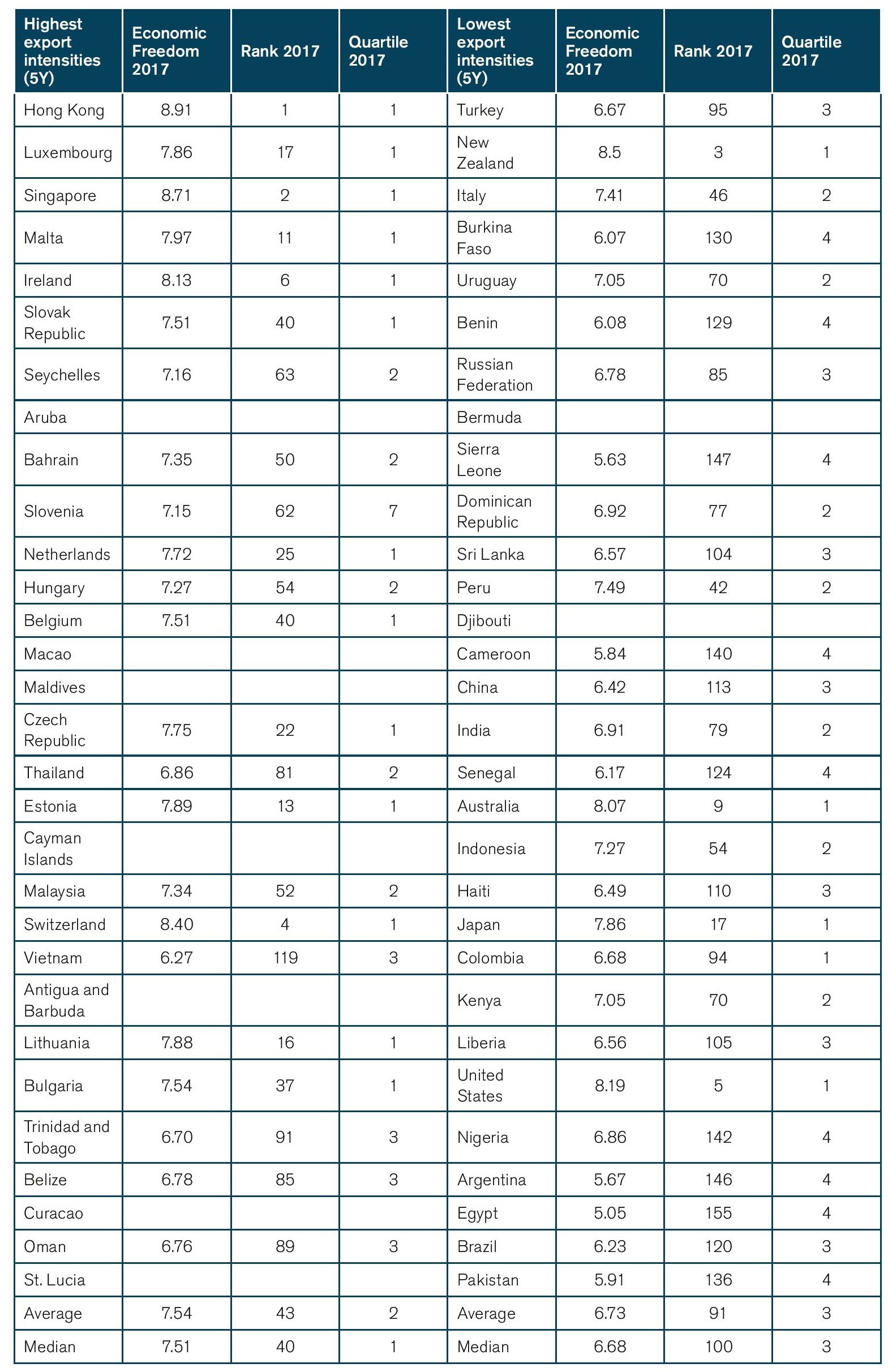

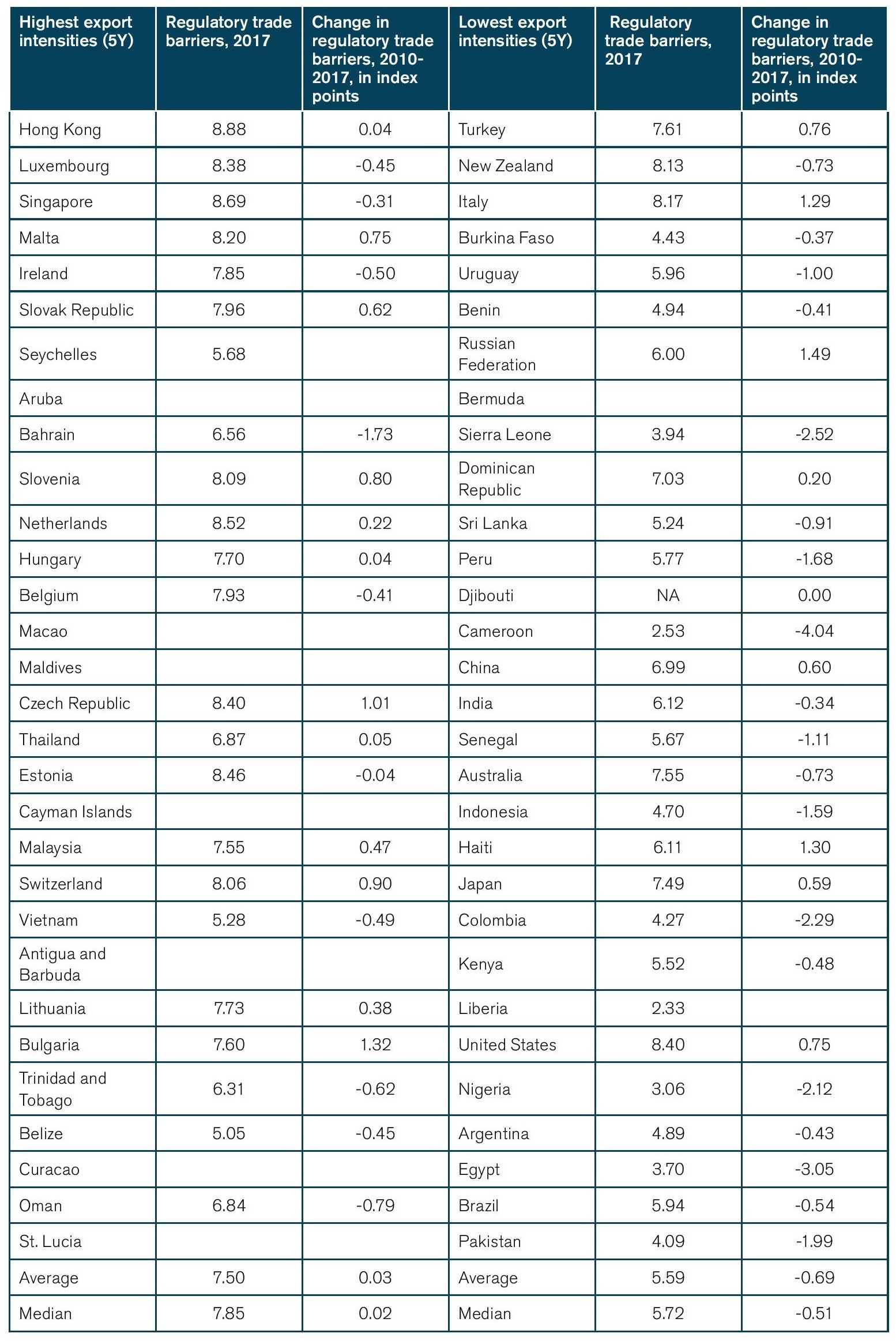

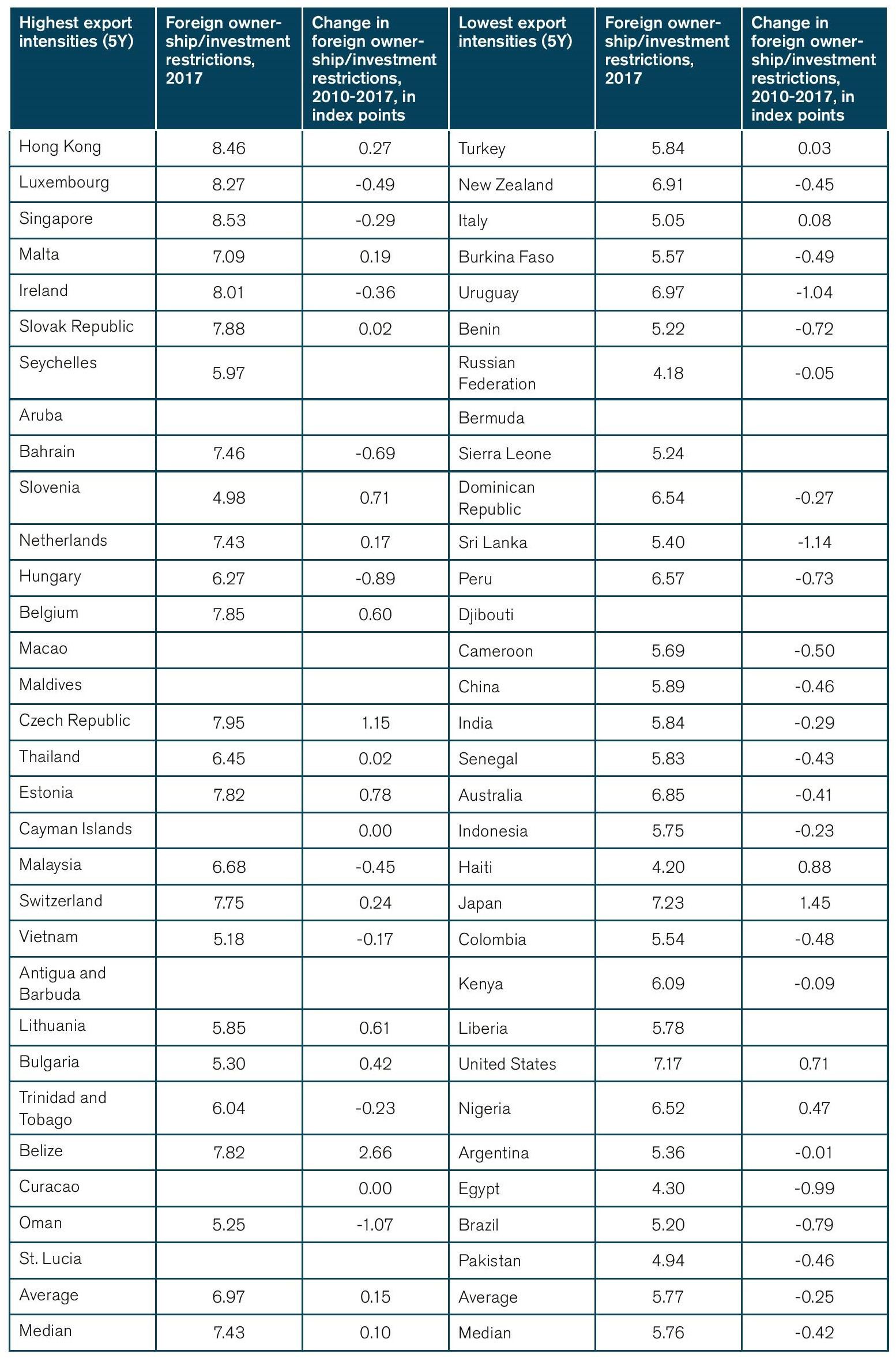

Empirical data also shows that the Inclusive Framework’s most export-intensive countries show on average a substantially higher degree of economic freedoms. Half of the Inclusive Framework’s most export-intensive countries rank higher than position 40 of 162 countries studied by the Fraser Institute. By contrast, half of the least export-intensive (large) countries rank worse than position 100 of 162 countries. In addition, the Inclusive Framework’s most export-intensive economies are generally much less restrictive to international trade than the least export-intensive countries. As concerns the state of the rule of law, numbers presented for the stringency of the enforcement of contracts and the state of the general legal system and property rights demonstrate that the IF’s most export-intensive economies generally perform better than the 30 least export-intensive countries. This result can be attributed to the high number of large countries among the 30 least export-intensive countries that perform poorly with respect to the state of the rule of law, e.g. Turkey, Italy, India, Indonesia, Egypt, Argentina, Brazil and Nigeria (see Figure 4 and, for a detailed overview Table 7, 8, 9 and 10 in Appendix II).

Figure 4: Top-30 “Inclusive Framework” countries with the highest and lowest export intensities, quality of domestic legal institutions, median values

Source: World Bank and Fraser Institute. For the state of the rule of law, numbers are presented for the stringency of the enforcement of contracts (LEC) and the state of the general legal system and property rights (LSPI).

Box 1: Key institutional characteristics of the OECD Inclusive Framework’s top 30 countries with the highest and the lowest export intensities

[1] For example, consider the case of the USA and Canada. Although Canada is larger in geographical terms, it is much smaller in economic terms. In fact, Canada is so small that, compared to the rest of the world, the interest the Canadian government and Canadian citizens pays on its debts cannot be influenced by Canadian market participants themselves. By contrast, the market of the USA is large enough, compared to the rest of the world, that the decisions inside the USA actually do affect the interest rate at which the USA is able to borrow. Similarly, a huge surge in demand in the US for an internationally traded commodity might well increase world prices and incomes in the commodity-producing sector, while a surge in demand in Canada would leave world prices and incomes rather unchanged. Similar considerations apply for the supply side, i.e. the provision of capital that is made available for foreign borrowers or domestic production that is made available for foreign buyers.

[2] By contrast, the main characteristic of a “closed economy” is self-sufficiency. Individuals and companies in a closed economy are not willing or not allowed to take part in any exchange with actors from other countries. An economy that is to a large extent closed to foreign exchange and investment relies solely on domestic activities without exposure to foreign products, services, technology and knowledge. The world of 2020 does not know fully closed economies. Although North Korea could be thought of as an example for a closed economy, North Koreans’ are also trading with partners from other countries, namely with companies and individuals from China.

[3] The patterns are largely similar for import intensities and overall trade (import plus export) intensities.

[4] A list of countries is available at https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/inclusive-framework-on-beps-composition.pdf (as of May 2020, last updated: December 2019).

[5] Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report is the world’s premier measurement of economic freedom, ranking countries based on five areas: size of government, legal structure and security of property rights, access to sound money, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation of credit, labour and business. See Fraser Institute: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom.

4. Implications for International Investment and Tax Revenues

According to the OECD’s own impact assessment from February 2020, Pillar I and II combined would “overall significantly impact on global tax revenues”. It is further stated that most governments’ tax revenues would increase, with “investment hubs experiencing some loss in tax revenues”. It is also claimed that the “overall direct effect on investment costs is expected to be small in most countries, as the reforms target firms with high levels of profitability and low effective tax rates.” The OECD further claims that “the reforms would also reduce the influence of corporate taxes on investment location decisions”.

The OECD’s own analysis does not account for governments’ responses to the shift in taxing rights under Pillar I and limitations on tax competition imposed by Pillar II. In other words, the OECD’s analysis is comparative-static. It does not take into account future changes in individual governments’ tax policymaking behaviour, particularly the future path of tax competition and how internationally-operating companies would react to new developments in tax competition, e.g. lower statutory corporate tax rates in some jurisdictions and/or greater use of tax incentives by governments to drive down effective corporate tax rates. As both Pillar I and II aim to change governments’ tax policy behaviour, assessments should be forward-looking in the sense that they account for trade-offs and consistency problems over time. This has also been suggested by the theory of international tax competition. Keen and Konrad (2012), for example, state that “[t]ax competition takes place, in practice, in a dynamic framework. This has several implications. […] [D]ecisions are made sequentially. Some early decisions may generate stock effects that determine the environment in which later decisions take place. Today’s capital stock is the result of earlier decisions on savings and consumption, and this may generate time consistency problems for the optimal tax policy that interact with the effects of tax competition. A third aspect is the relationship between stocks and flows and the trade-off between taxing stocks and attracting an inflow of new capital. (p. 36)

Despite the existence of dynamic effects, expert discussions often disregard the relevance of tax policies for companies’ investment decisions. Similarly, media coverage and the public debate often fall short to reflect on the impacts of tax policymaking and tax competition on the development of commerce and investment over time. Dynamic effects on companies’ commercial and investment activities should be addressed by impact assessments of the OECD’s proposals. The literature on the theory of international tax competition suggests that governments will continue to compete for investment and business activity in the future (see, e.g. Kee and Konrad 2012 for an extensive coverage of the theory of international tax competition and cooperation). Governments’ past behaviour strongly suggests that tax competition will continue with Pillar I and II implemented.

Tax competition may even intensify under the limitations of OECD’s Pillar I and II proposals. The degree of tax competition can be captured by the development of differences in effective tax rates over time (henceforth tax rate differentials). The differentials between statutory corporate tax rates and effective corporate tax rates recently outlined by ZEW (2019), for example, indicate that EU and non-EU governments implemented various tax incentive polices. Similarly, tax policy measures outlined by the recent World Investment Report confirm that governments of developing and emerging market economies consider tax incentives a key policy measures to stimulate domestic investment and to attract foreign investors (UNCTAD 2019; Box 2 below).

Box 2: Tax and other fiscal incentives still important investment promotion tools (UNCTAD)

Moreover, the OECD itself highlighted in 2008 that “[v]irtually all governments are keen to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). It can generate new jobs, bring in new technologies and, more generally, promote growth and employment. The resulting net increase in domestic income is shared with government through taxation of wages and profits of foreign-owned companies, and possibly other taxes on business (e.g. property tax). FDI may also positively affect domestic income through spillover effects such as the introduction of new technologies and the enhancement of human capital (skills). Given these potential benefits, policy makers continually re-examine their tax rules to ensure they are attractive to inbound investment. […]” The OECD (2008, p. 1)

As suggested by ZEW (2020), Devereux et al. 2020) and others, the OECD’s tax reform proposals could increase tax competition, with the proposed minimum threshold tax level of 12.5% being the lower bound. A global minimum effective tax rate may even accelerate tax-cutting competition for countries that already apply relatively low corporate tax rates (Langenmayr (2020). The simple reason is that companies’ investment behaviour is influenced by the financial burden imposed by corporate taxes. Governments will likely anticipate that changes in countries’ effective corporate tax rates would trigger decreases in inward investment (less companies investing in the country) and increased in outward investment (more and more companies leaving the country. Governments, small and large, can be expected to lower effective corporate tax rates in order to contain negative effects on outward investment (less divestment of domestic businesses) and inward investment (maintaining/increasing attractiveness for companies from abroad.

The following analysis shall inform policymakers about the direction and potential magnitude of the impacts from the OECD’s Pillar II proposals on investment positions and investment-induced changes in tax revenues over time. The focus is on changes in investment and tax revenues that would result from continuing tax competition over time, taking into consideration a lower bound 12.5% minimum effective corporate tax rate on global corporate profits.

4.1 Methodological Considerations

The aim of this analysis is to show the direction and magnitude of effects on investment and tax revenues that would result from a gradual narrowing of OECD countries’ effective corporate tax rates – a process that may intensify as a result of the imposition of a lower effective corporate tax bound rate of 12.5%, which is anticipated by governments that compete for investment and business activity, mainly small open economies. The results are in various respects also relevant for an assessment of the potential implications of Pillar I on FDI positions and tax revenues.

For the group of OECD countries, the following analysis provides estimates for the investment and revenue impacts of changes in the differential of effective tax rates for three scenarios:

Scenario 1:

In Scenario 1, we assume that investors’ “home countries” unilaterally reduce their effective corporate tax rate to 12.5%, while the effective corporate tax rates in the partner countries remain unchanged.

Scenario 2:

In Scenario 2, we assume that investors’ FDI destinations reduce their effective corporate tax rate to 12.5%, while the effective corporate tax rate of the home country remains unchanged.

Scenario 3:

All OECD countries reduce their effective corporate tax rates to 12.5%, which represents a full elimination of present tax rate differentials (“full narrowing”) within the group of OECD countries – similar to the estimations conducted in OECD (2017).

Scenarios 1 and 2 are included for illustrative purposes, highlighting governments’ need to react to changes in other countries’ corporate tax regimes if they wish to maintain domestic investment in their country and/or attract additional investment from abroad. For example, ceteris paribus, a unilateral reduction of the effective corporate tax rate to 12.5% would increase investment in the tax-cutting country when all other countries continue to apply previous tax rates. By contrast, maintaining a high effective corporate tax rate would reduce domestic investment in the respective country if the effective tax rates decreases in all other countries.

Scenario 3 is considered the most relevant scenario. It outlines the potential end state of a process of sequential tax competition up to the lower bound of 12.5%. Scenario 3 represents the aggregation of effects from scenarios 1 and 2. It can be interpreted as a new equilibrium after a period of gradual and, for some countries, intensified tax competition where neither small nor large countries can compete on effective corporate tax rate differentials anymore. An important implication for small open economies is that in this equilibrium, ceteris paribus, large countries would be more attractive to investors than small countries due to market size and economic gravity effects.

While a global minimum effective tax rate is only foreseen under Pillar II, the incentives and investment relocation mechanisms at work are similar for Pillar I. The government of a country that is home to large internationally operating companies may have an incentive to lower the effective corporate tax burden at home if these companies face a higher total tax burden due to additional taxation in market jurisdictions. Additional or higher taxes in market jurisdictions may increase the effective corporate tax rate of a company to an extent that may cause a competitive disadvantage as compared to competitors headquartered in jurisdictions with lower effective corporate taxes. A higher group-wide tax burden may therefore cause companies to reconsider their overall international investment positions including their country of headquarter. Confronted with such situations, governments may have to reconsider their effective corporate tax rates if they want to keep successful international businesses in their country. Governments would have to change tax policies at home, e.g. through lower statutory tax rates or measures intended to lower their effective tax rates.

The methodology underlying this analysis follows the considerations of a 2017 Working Paper published by the OECD’s Economics Department (OECD 2017), which analyses the impact of corporate tax rate differentials on OECD countries’ FDI positions (stocks) and tax revenues.[1] The authors estimate the redistribution effect of corporate tax rate differentials on FDI and changes countries’ corporate tax revenues that result from companies’ responses to international differences in corporate tax rates.

The authors acknowledge that different “policy- and non-policy” factors impact on multinational companies’ investment decisions. Non-policy factors include gravity forces, such as market size and distance between home and host countries, but also factor endowment characteristics. Policy factors include regulatory (trade and investment) openness, product-market regulation, labour-market arrangements and infrastructure. It is highlighted that policy factors can generally raise or lower the overall cost of investment and other commercial transactions. In line with a vast body of economic literature, the authors stress that “[t]axation is another important policy factor affecting [multinational enterprises] real investments decisions. Ceteris paribus, lower-tax countries are expected to have larger inflows (and smaller outflows) of capital than higher-tax countries.” (p. 6)

The authors estimate changes in OECD countries’ bilateral FDI positions (inward and outward FDI) in response to a full elimination of corporate tax rate differentials. They find that “in the absence of bilateral tax rate differences, the inward FDI position of high tax countries would increase and their outward FDI position would decrease. In a symmetrical way, the inward FDI position of low tax countries would decrease and their outward FDI position would increase. […] For most OECD countries, the calculated effects of tax rate differentials on FDI positions range between -15% and 15% of current FDI positions, assuming a semi-elasticity of -1.5”.[2] (p- 12) It is also found that “[t]he share of OECD countries aggregate outward FDI positions into partner countries that can be explained by the tax rate differential is decreasing with partner countries statutory tax rate. This reflects that in most cases, taxes are not the major driver of FDI position.” (p. 13) Similarly, their “analysis suggests that higher-tax OECD countries lose revenue due to the effect of tax differentials on FDI positions, while lower-tax countries gain revenue.” (p.14)

It should be noted that OECD (2017) does not report results on a country-by country level. Results are only plotted for ranges of countries’ “current statutory corporate tax rates”. The highest relative changes in inward FDI, outward FDI and tax revenues are generally estimated for low-tax countries (statutory corporate tax rate of less than 15%) and high-tax countries (statutory corporate tax rate of more than 35%).

For the three scenarios outlined above, this analysis replicates the methodology of OECD (2017). We compute changes in OECD countries’ inward and outward FDI positions and corresponding changes in tax revenues that may result from the imposition of a global minimum effective tax rate of 12.5%. The calculations are based in the following formulas:

Equation 1: Scenario 1: ΔFDIout,r=∑pFDIr,p×ε×(tr−12.5),

Equation II: Scenario 2: ΔFDIout,r=∑pFDIr,p×ε×(12.5−tr),

Equation III: Scenario 3: ΔFDIout,r=![]() FDIr,p×ε×(tr−tp)

FDIr,p×ε×(tr−tp)

whereby ΔFDIout,r is the change in total FDI from the home country r to the host country, tr is the effective corporate tax rate in the home country, tp is the effective corporate tax rate in the host country and ε is the semi-elasticity of investment (in response to changes in the effective corporate tax rate). Changes in inward FDI positions of country r can be obtained by a similar approach. In line with OECD (2017), we provide estimates for two semi-elasticities ε : -1.5 and -3, representing the percentage change in FDI positions (stock) associated with a one percentage-point change in the effective corporate tax rate.[3]

In line with OECD (2017), FDI is treated as an investment in equity. For outward FDI, for example, it is assumed that any extra outflow of equity caused by tax rate differences would have been invested at home in the absence of tax rate differences. It is also assumed that this investment at home would generate a taxable profit equal to a “normal” rate of return, which is set at 10%. Multiplying the normal return with the effective corporate tax rate in the home country results in an estimate of the FDI-induced tax revenue effect caused by the differences in tax rates between the home country and the partner (host) countries and the elimination of these differences respectively.

It should be noted that, in line with OECD (2017), we compute hypothetical changes in bilateral FDI positions, i.e. changes in FDI positions that may evolve in the absence of tax rate differences, everything else being equal. The numbers should not be taken by face value but considered indicative with respect to direction and relative magnitude of the effects from continued tax competition on a country’s FDI positions and corporate tax revenues.

4.2. Data

FDI data: FDI data are taken from the OECD’s foreign direct investment statistics database. Bilateral data is only available for the period 2003 to 2013, while for most countries the latest year for which data is published is 2012. The data available is generally patchy. Many governments did not consistently report FDI data in the past. Some governments refer to classified (confidential) information, while other do not further specify why data is not made publicly available. To address this problem, average values were calculated for the period 2003-2013. If the 2003-2013 average value is greater than the value reported in the latest year available (2012 or 2013), the higher value is used for the calculations.[4]

Corporate income tax rates: due to complete coverage of OECD countries, composite effective average tax rates were taken from the OECD, representing the year 2017.[5] To account for the 2017 corporate tax reform in the US, an updated effective average corporate tax rate has been taken from ZEW (2019).[6] For scenario 1, we applied the 12.5% effective corporate tax rate to the home countries and 2017 effective corporate tax rates to partner counties. For scenario 2, we applied 2017 effective corporate tax rate for the home country and the 12.5% minimum effective rate for partner countries. In scenario 3, the 12.5% minimum effective rate was applied for all OECD countries.

4.3. Results

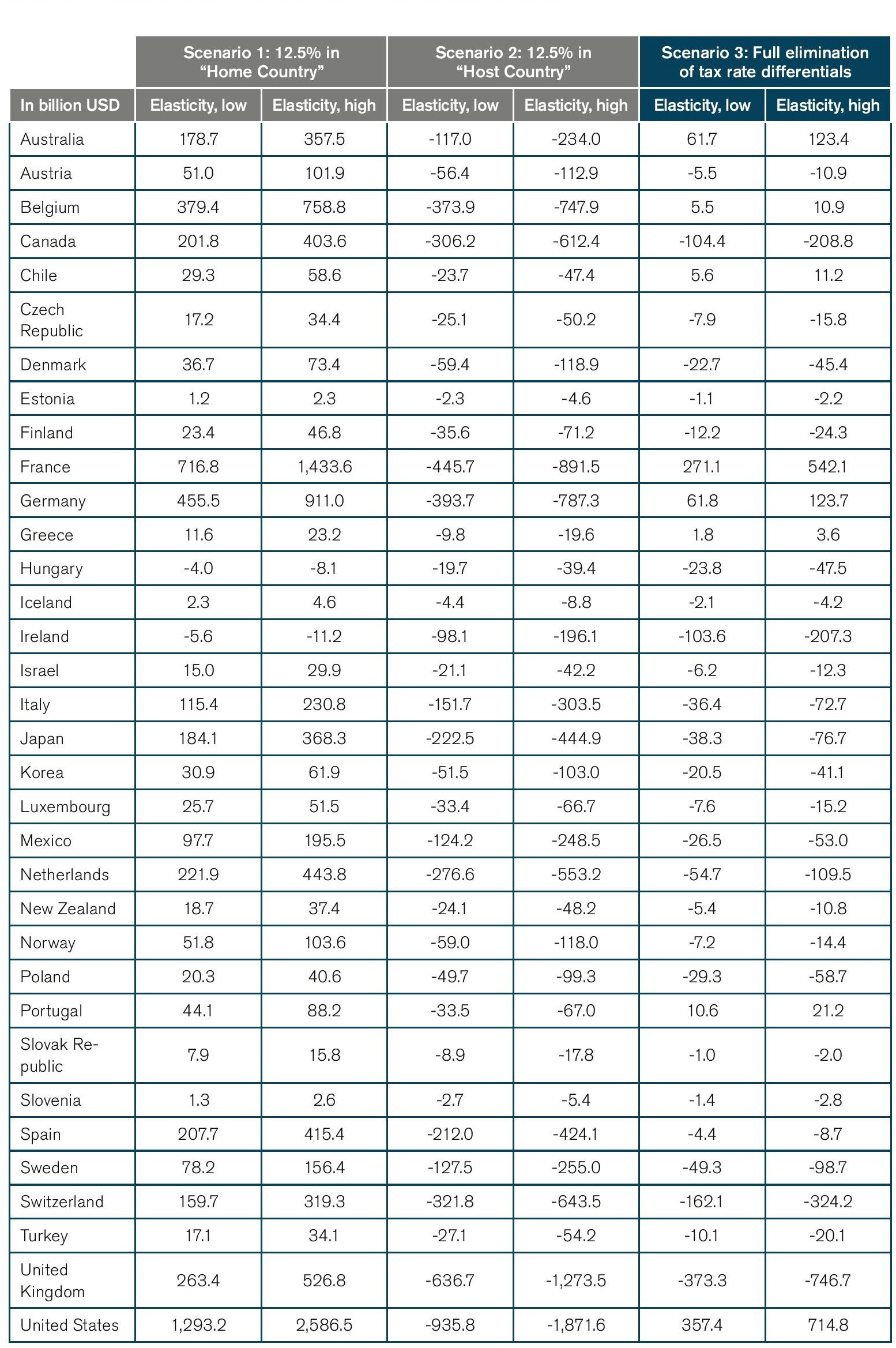

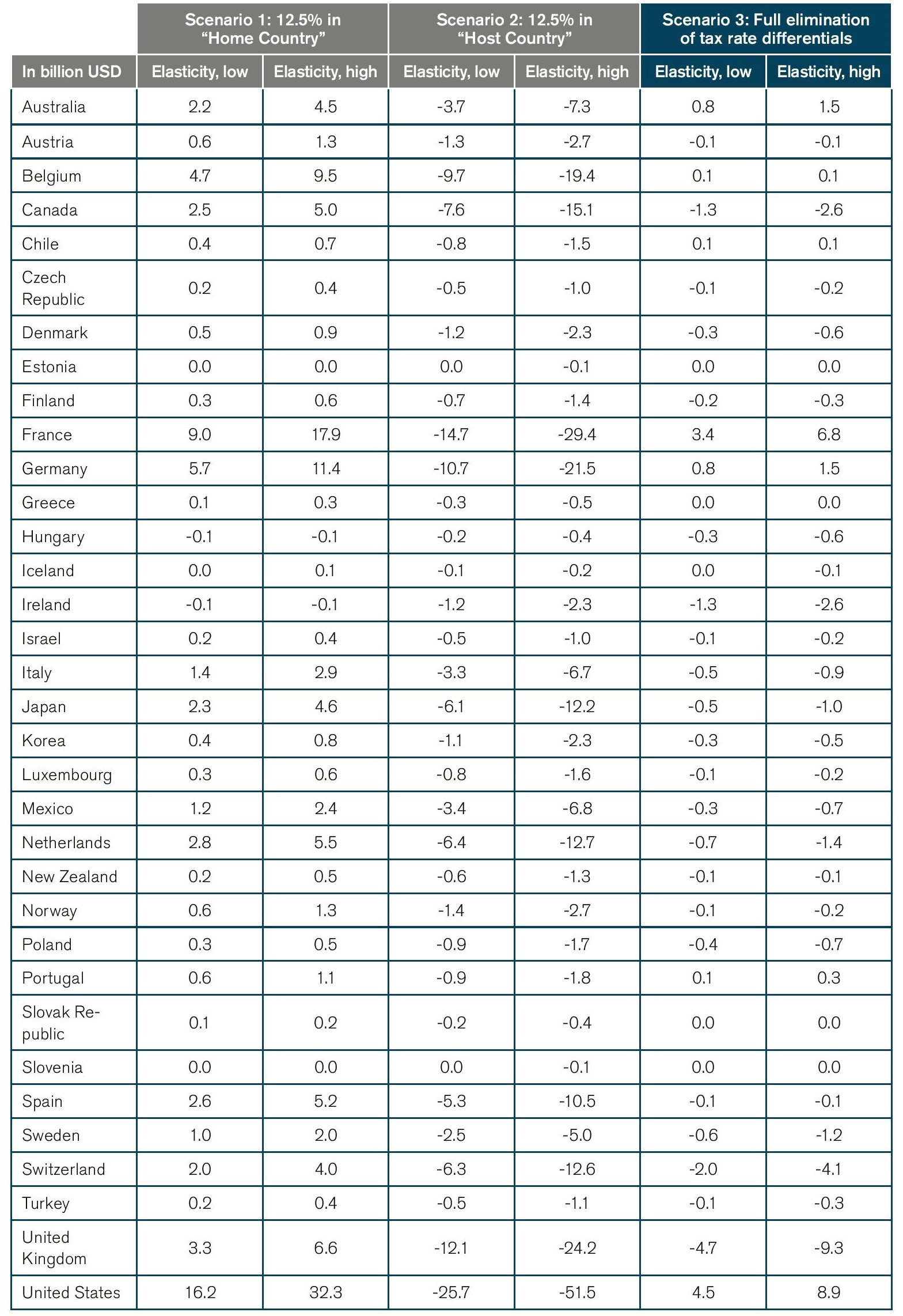

In the main body of this paper, results are only plotted for scenario 3. For scenarios 1 and 2, results are provided in Appendix III – Estimation results. As concerns scenario 1, with the exception of Hungary and Ireland, which currently show effective corporate tax rates lower than the OECD-proposed minimum effective corporate tax rate of 12.5%, domestic investment would increase in all countries if their governments would unilaterally lower the domestic effective corporate tax rate to 12.5% while all other countries would maintain effective corporate tax rates at 2017 levels (2019 level for the US). Countries’ increases in investment are driven by higher levels of inward investment from abroad and “returning” outward investment. In contrast, countries would lose domestic investment if their governments would maintain effective corporate tax rates at current (2017) levels while all other governments would lower their effective corporate tax rates to 12.5%.

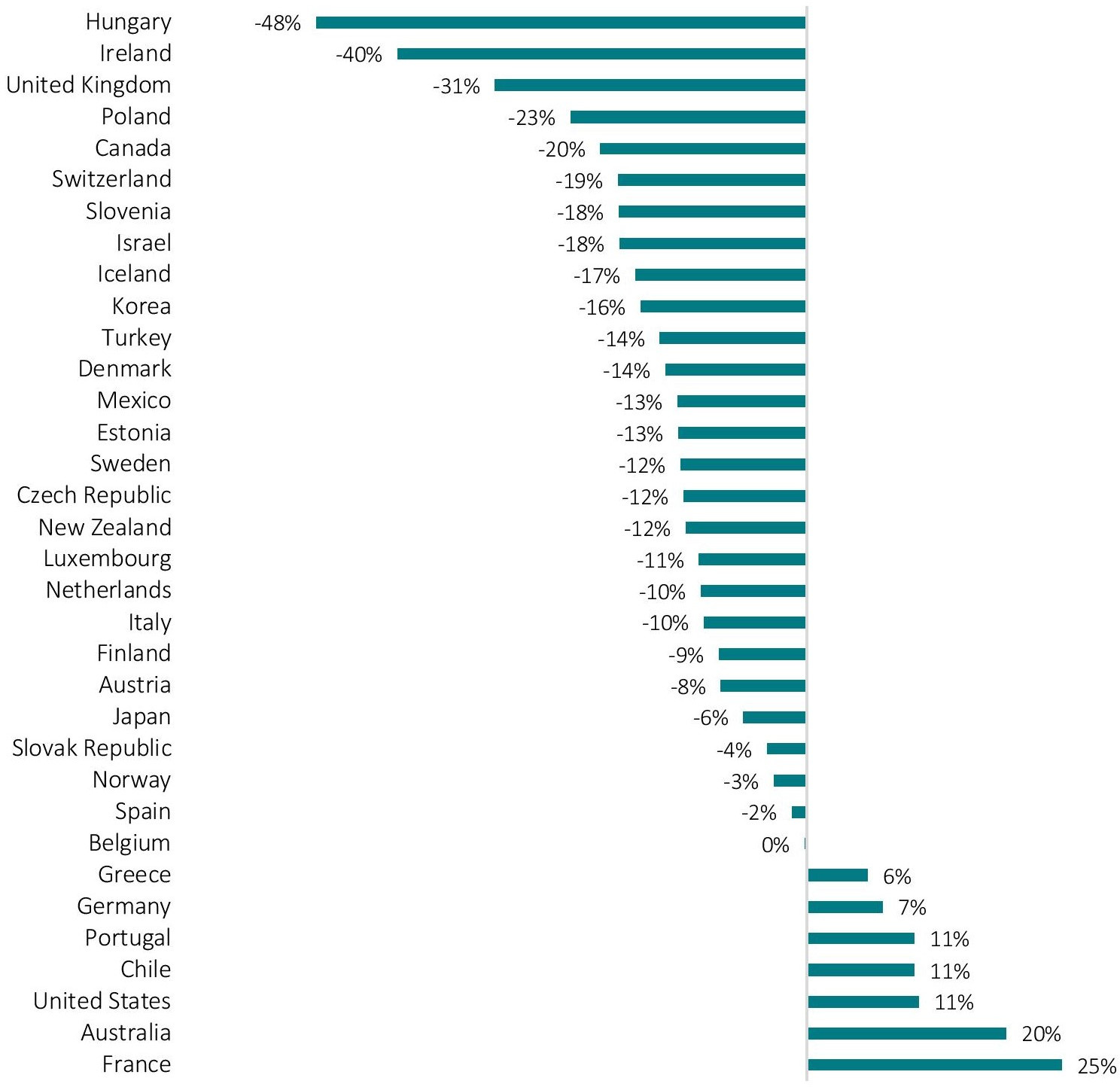

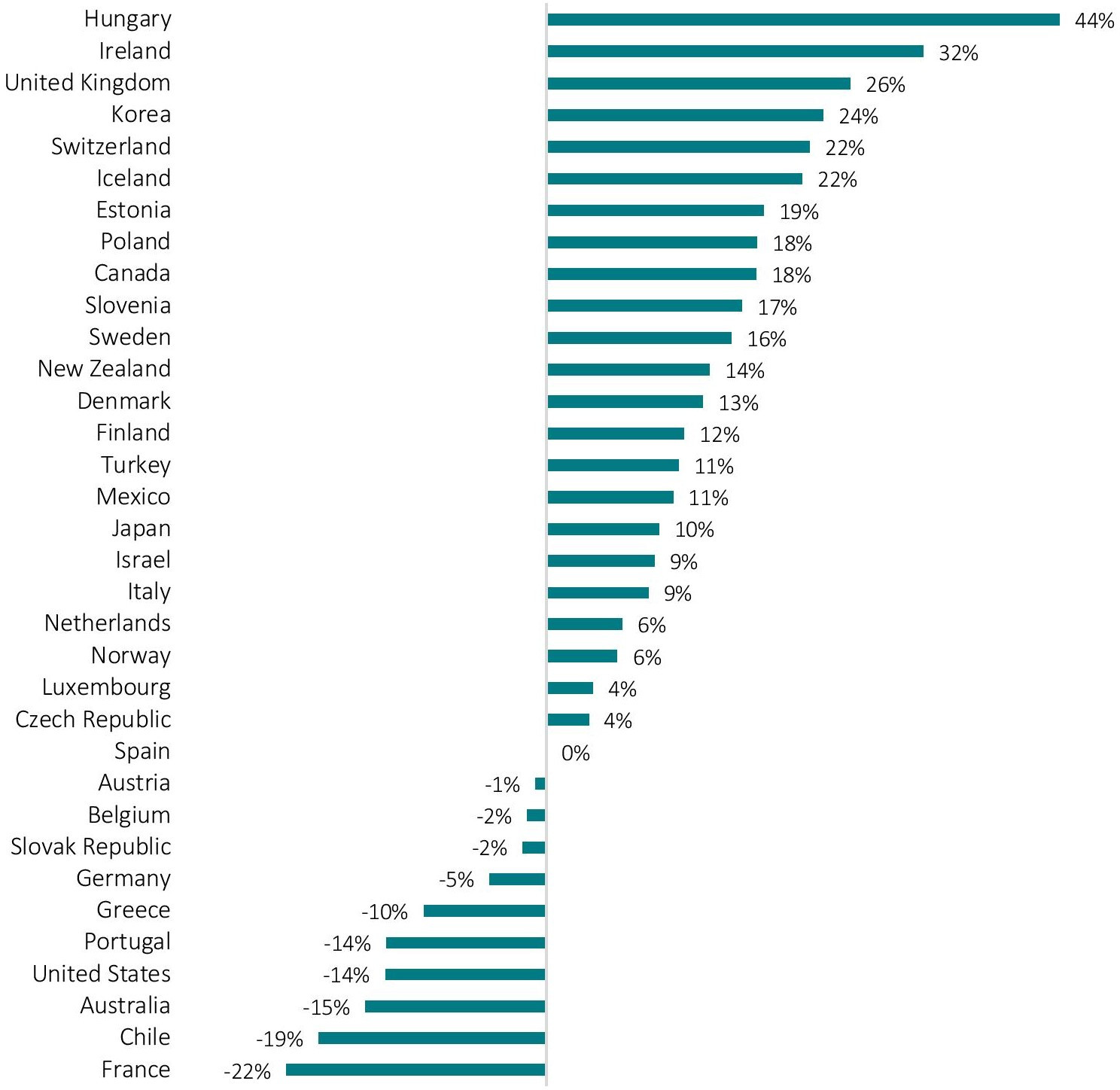

Scenario 3 assumes a full elimination of effective corporate tax rate differentials among OECD countries. For scenario 3, inward investment would increase in Greece, Germany, Portugal, Chile, the US, Australia and France, while inward investment would decrease in all other countries. At the same time, Austria, Belgium, the Slovak Republic, Germany, Greece, Portugal, the US, Australia, Chile and France would experience returning outward investment (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5: Changes in inward investment in % of total inward investment from OECD countries resulting from the full elimination of effective corporate tax rate differentials, scenario 3

Source: ECIPE calculations based on methodology of OECD (2017). Note: the estimates depicted are for scenario 3 and based on a semi-elasticity of -3.

Figure 6: Changes in outward investment in % of total outward investment in OECD countries resulting from the full elimination of effective corporate tax rate differentials, scenario 3

Source: ECIPE calculations based on methodology of OECD (2017). Note: the estimates depicted are for scenario 3 and based on a semi-elasticity of -3. Positive values imply divestment in the home country. Negative values reflect returning investment to the home country.

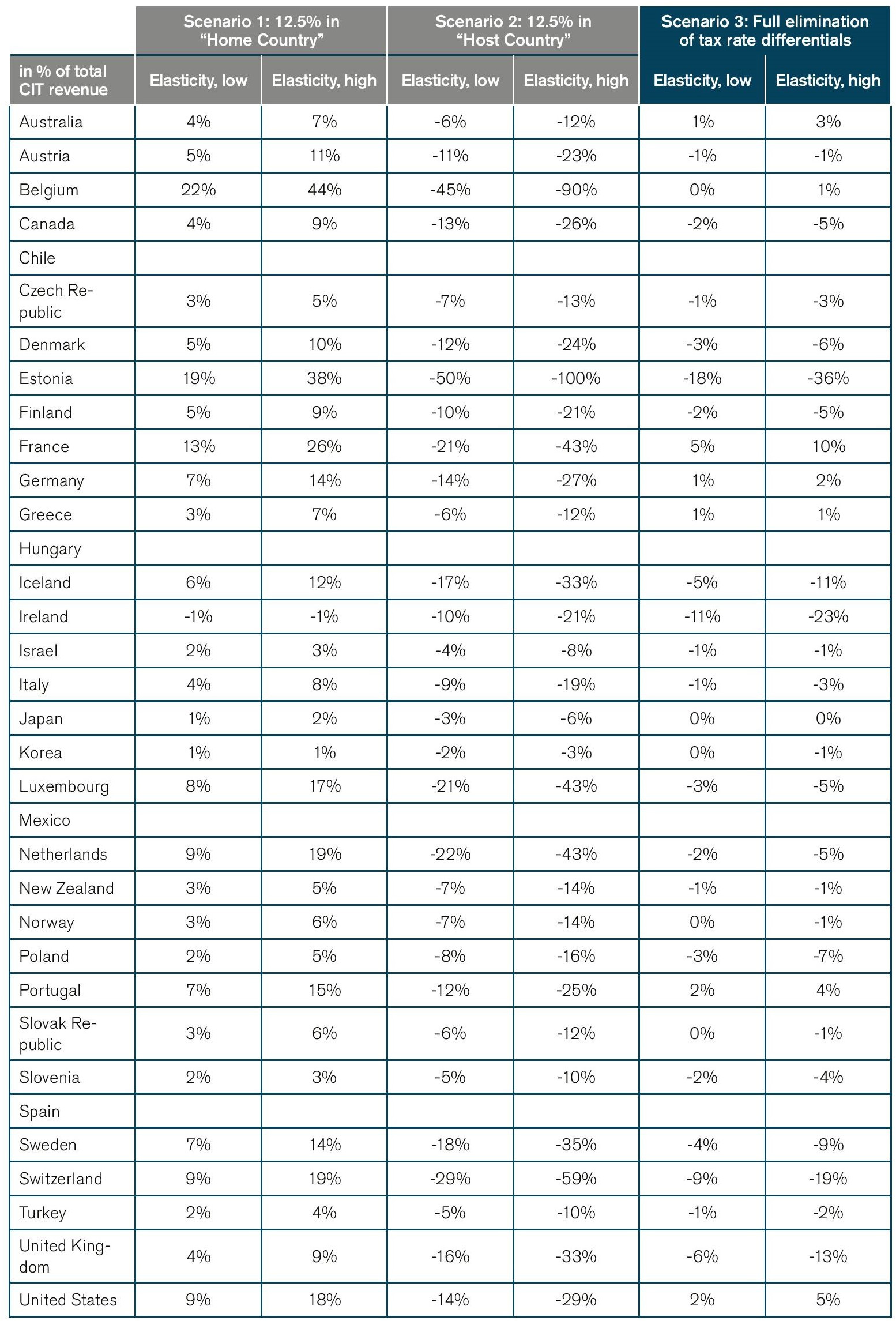

As outlined by Table 8 in Appendix III – Estimation results, for scenario 3 the highest positive net impacts on aggregate domestic investment are estimated for the US (+715bn USD), France (+542bn USD), Germany (+124bn USD), and Australia (123bn USD). The highest negative net impacts in terms of domestic investment are estimated for the UK (-747bn USD), Canada (-209bn USD), Switzerland (-324bn USD), Ireland (-207bn USD), the Netherlands (-110bn USD), Sweden (-99bn USD), Japan (-77bn USD), Italy (-73bn USD), Poland (-59bn USD) and Mexico (-53bn USD).

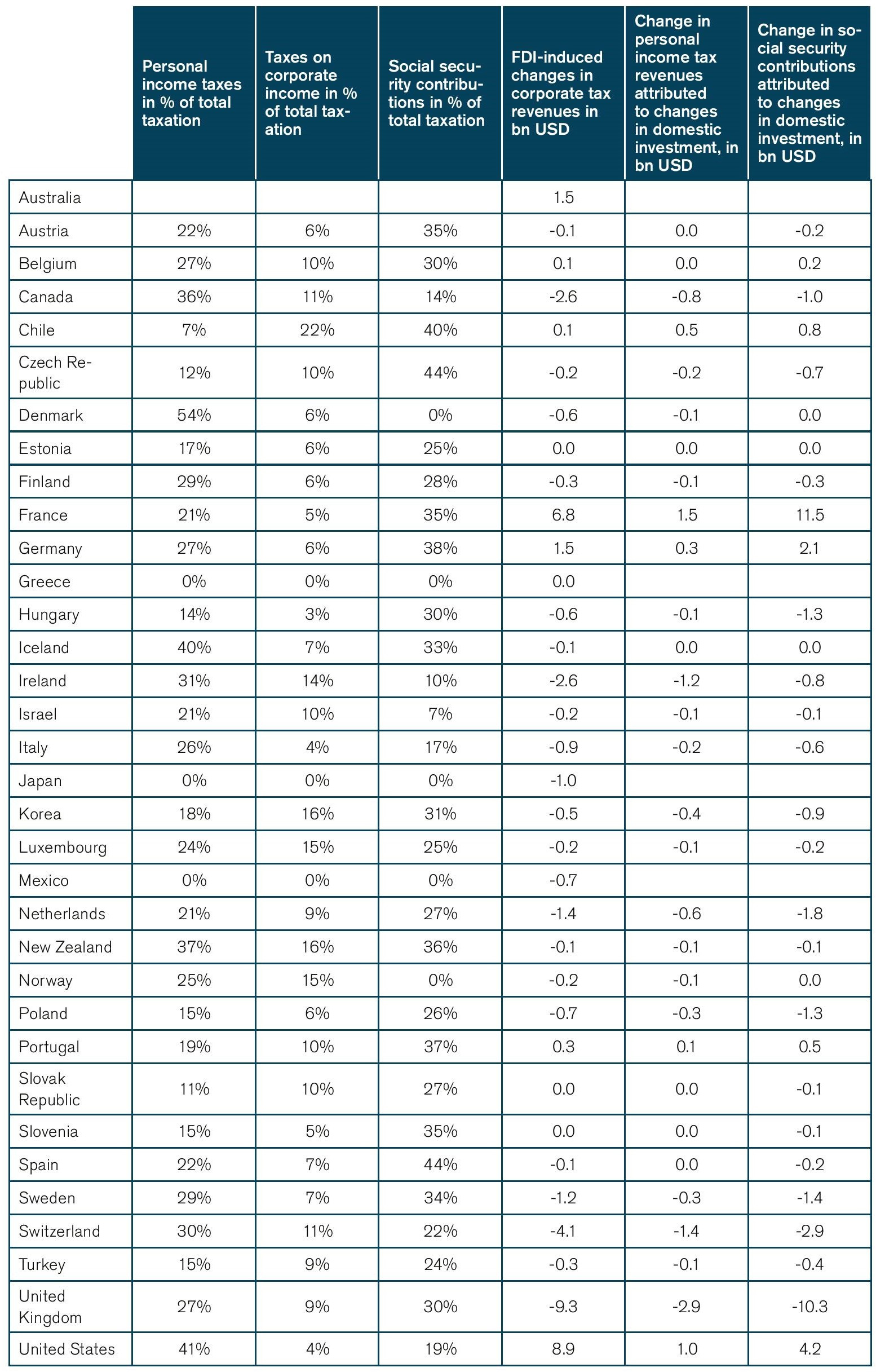

The estimated changes in domestic investment are generally mirrored in the changes in government revenues from corporate income taxes (Table 9 and Table 10). For the high elasticity scenario 3, the aggregate FDI change-induced corporate tax revenues would rise in the US (+8.9bn USD annually; +5% of 2018 CIT revenues), France (+6.8bn USD; +10%), Germany (1.5bn USD; +2%), and Australia (+1.5bn USD; +3%). The highest decreases in FDI-induced corporate tax revenues changes are estimated for Estonia (-36% of 2018 CIT revenues), Ireland (-23%), Switzerland (-19%), the UK (-13%), Iceland (-11%), and Sweden (-9%). It should be noted that these estimates are based on a comparison of tax revenues generated by countries’ current FDI stock and tax revenues generated by countries’ FDI stock in the new equilibrium, everything else remaining equal. The numbers do not reflect the revenue impact resulting from tax revenues generated by other businesses that are subject to corporate income taxes.

Rising and falling levels of domestic investment would also impact governments’ tax revenues on personal income and revenues from social security contributions. As outlined by Table 11, for most OECD countries, taxes on personal income as well as social security contributions are a much more important source of tax revenue than revenues generated from corporate income. The OECD median multiplier is 1.45, i.e. the sum of revenues from taxes on personal income and social security contributions exceeds corporate income tax revenues by about 45%. Taking into account changes taxes on personal income and social security contributions, the increases in FDI change-induced revenue gains would amount to 20bn USD for the French government, 4bn USD for the German government, and 14bn USD for the US government.[7] Again, it should be noted that these estimates are based on a comparison of tax revenues generated by countries’ current FDI stock and tax revenues generated by countries’ FDI stock in the new equilibrium, everything else remaining equal. The numbers do not reflect the revenue impact resulting from tax revenues generated by other businesses that are subject to corporate income taxes.

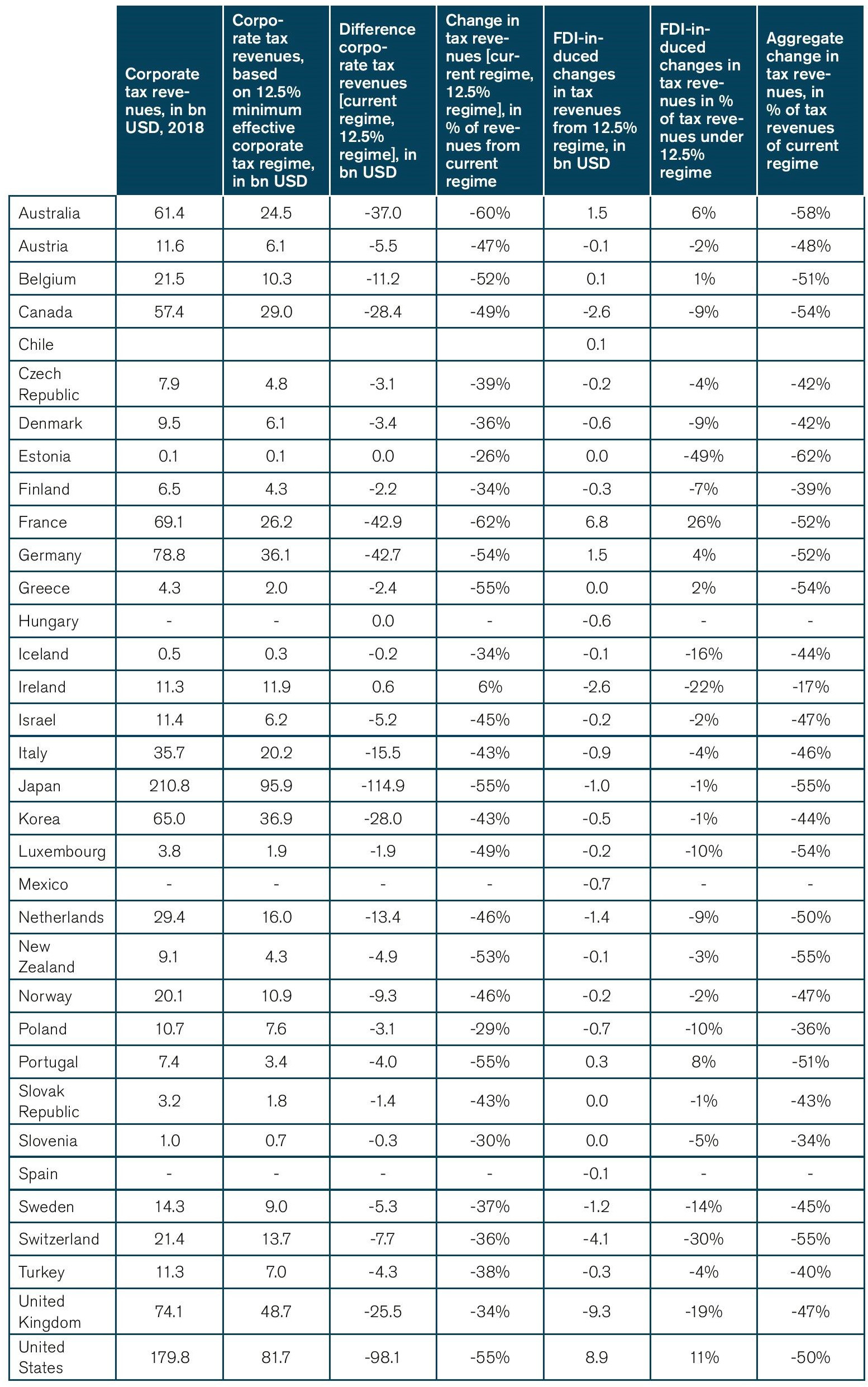

A much more significant change in tax revenues may result from the reduction of current effective corporate tax rates to the minimum effective rate proposed by the OECD. If individual governments would lower their effective tax rates to 12.5%, these rates would more or less (depending on specific tax privileges granted for certain sectors or activities) apply for all businesses, including SMEs and micro businesses. It is an often-stated policy objective of the OECD, the European Commission and individual governments to level the tax playing field for businesses of all sizes by eliminating tax loopholes for large multinationals. Assuming a linear relationship between the current levels of countries’ effective corporate tax rates and governments’ tax revenues, we can derive hypothetical annual tax revenues for the 12.5% threshold rate proposed by the OECD. Accordingly, annual corporate tax revenues would decrease significantly for most countries. As outlined by Figure 10, the largest losses in corporate tax revenues would arise in the countries with the highest effective corporate tax rates, i.e. France (-62%), Australia (-60%) and Greece, Portugal (-55%), and the US (-55%). The losses would be lower in relative terms, but still significant in low tax jurisdictions (except for Ireland). For OECD countries, compared to 2018 corporate tax revenues the median percentage loss estimate is -44%.

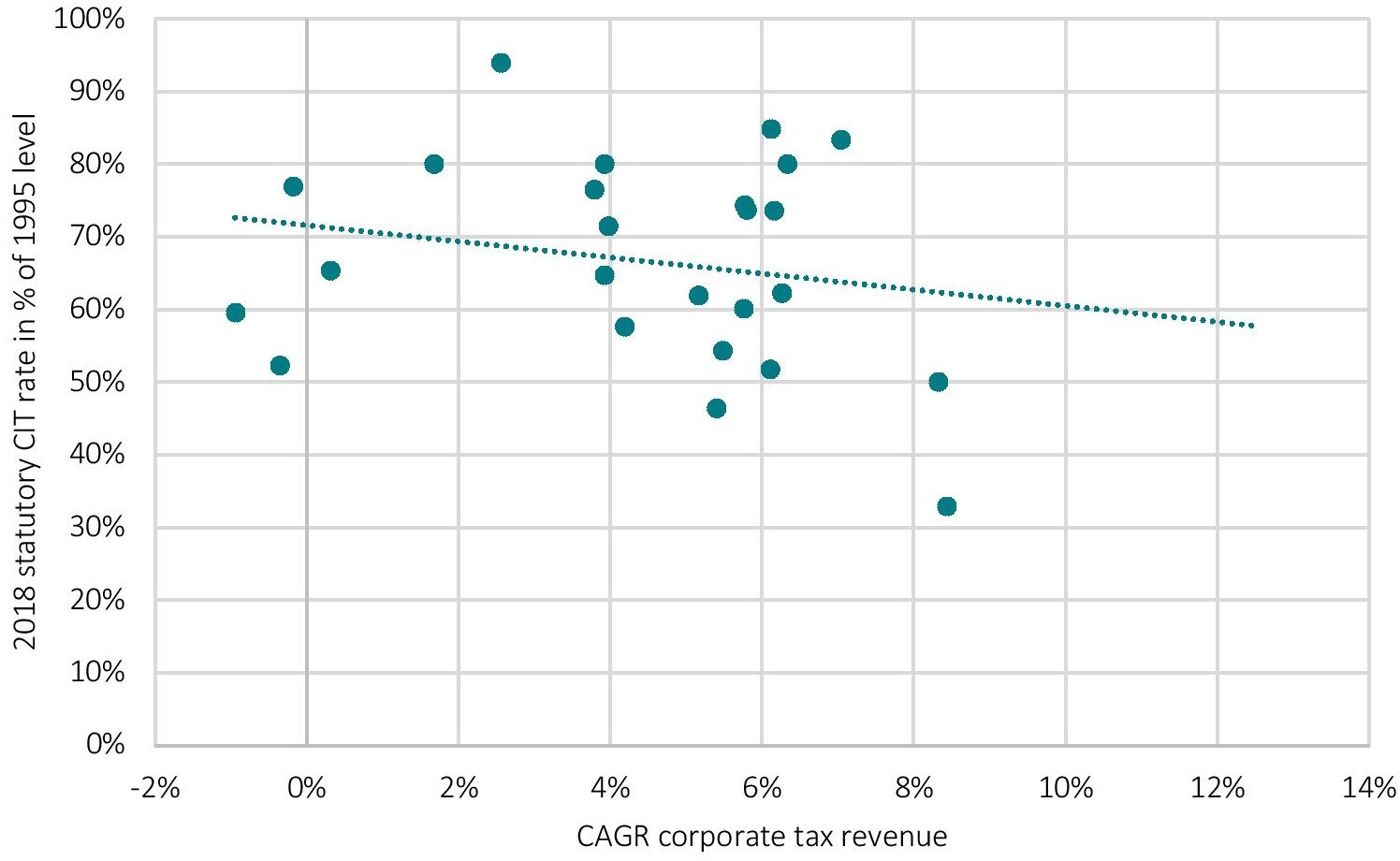

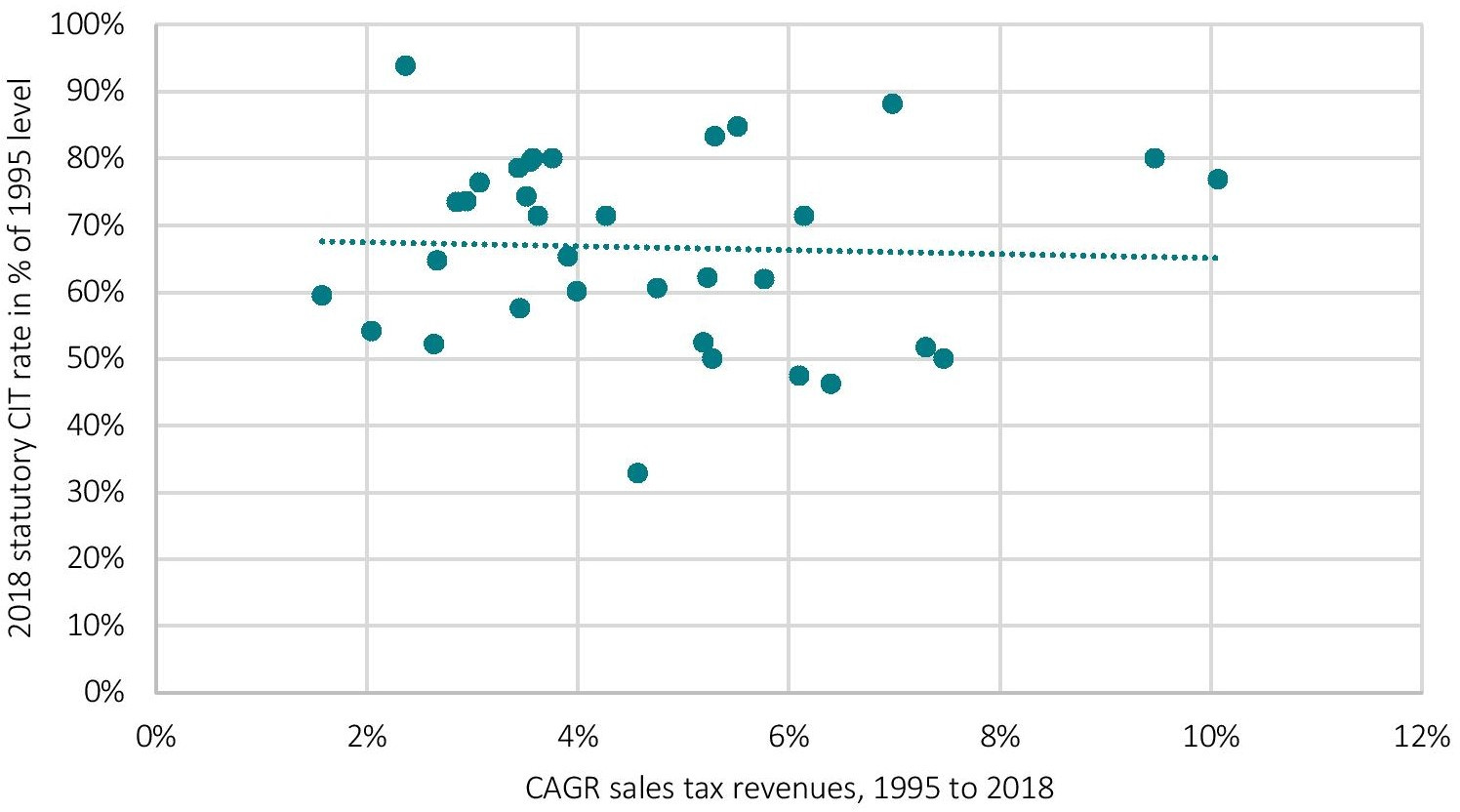

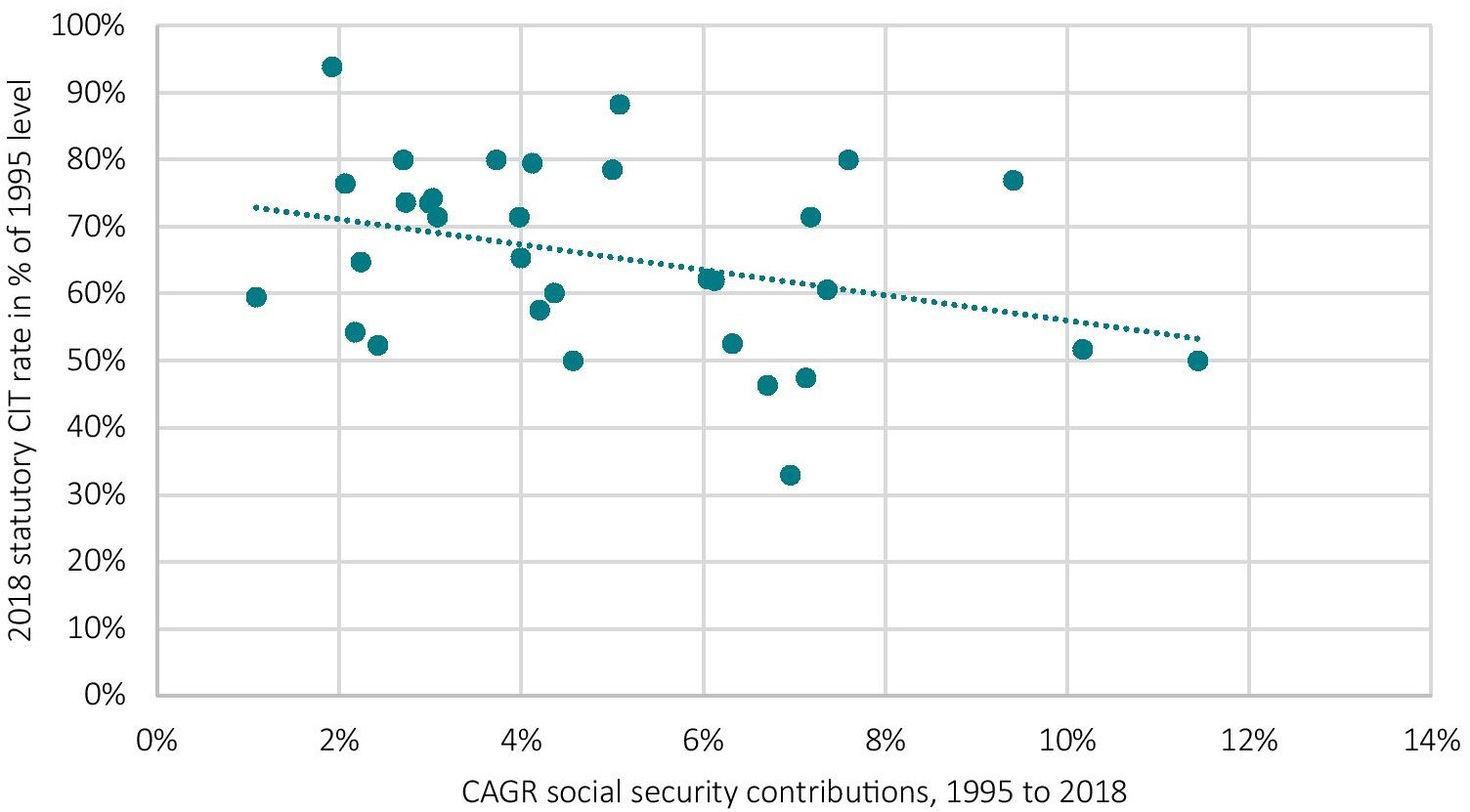

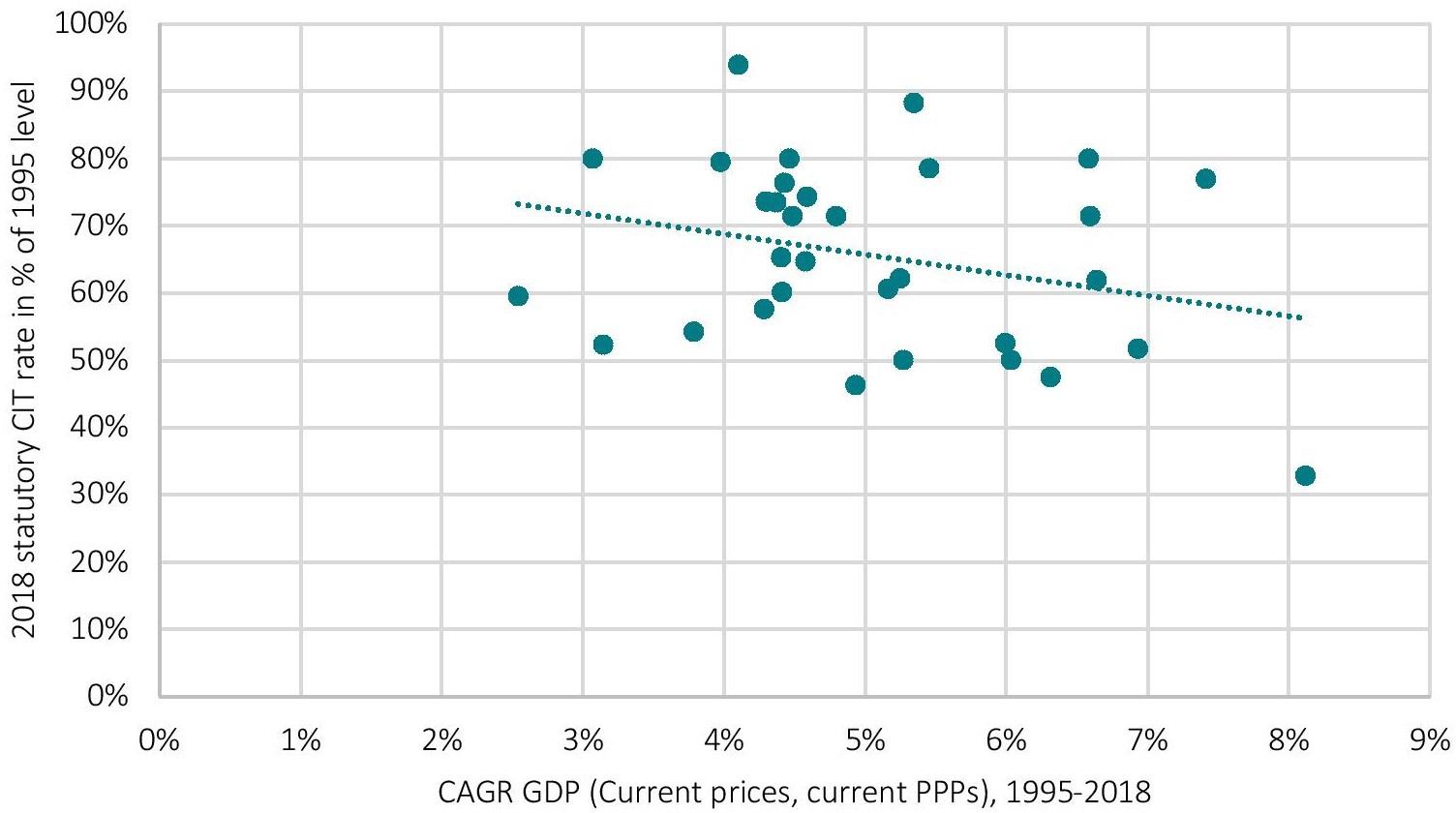

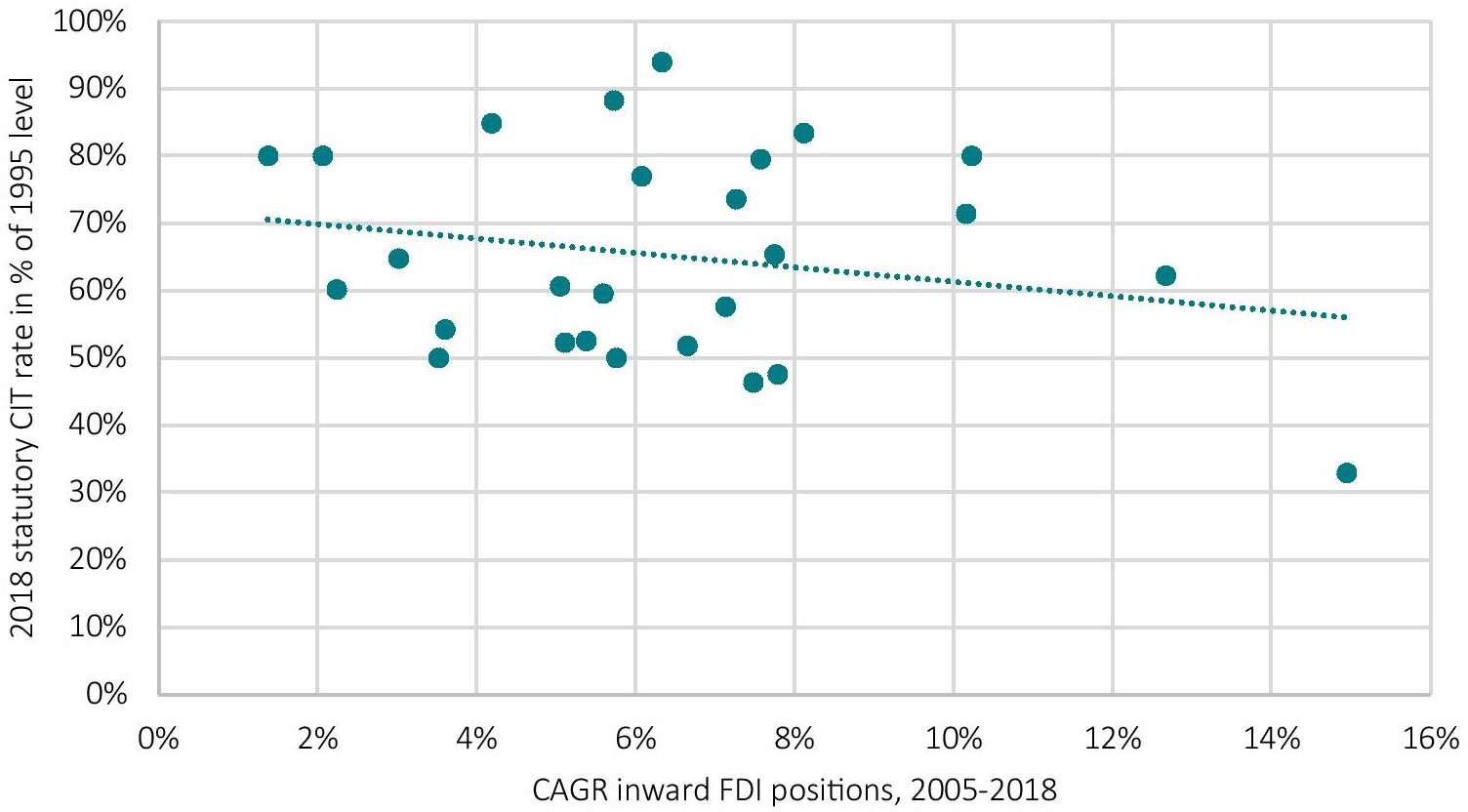

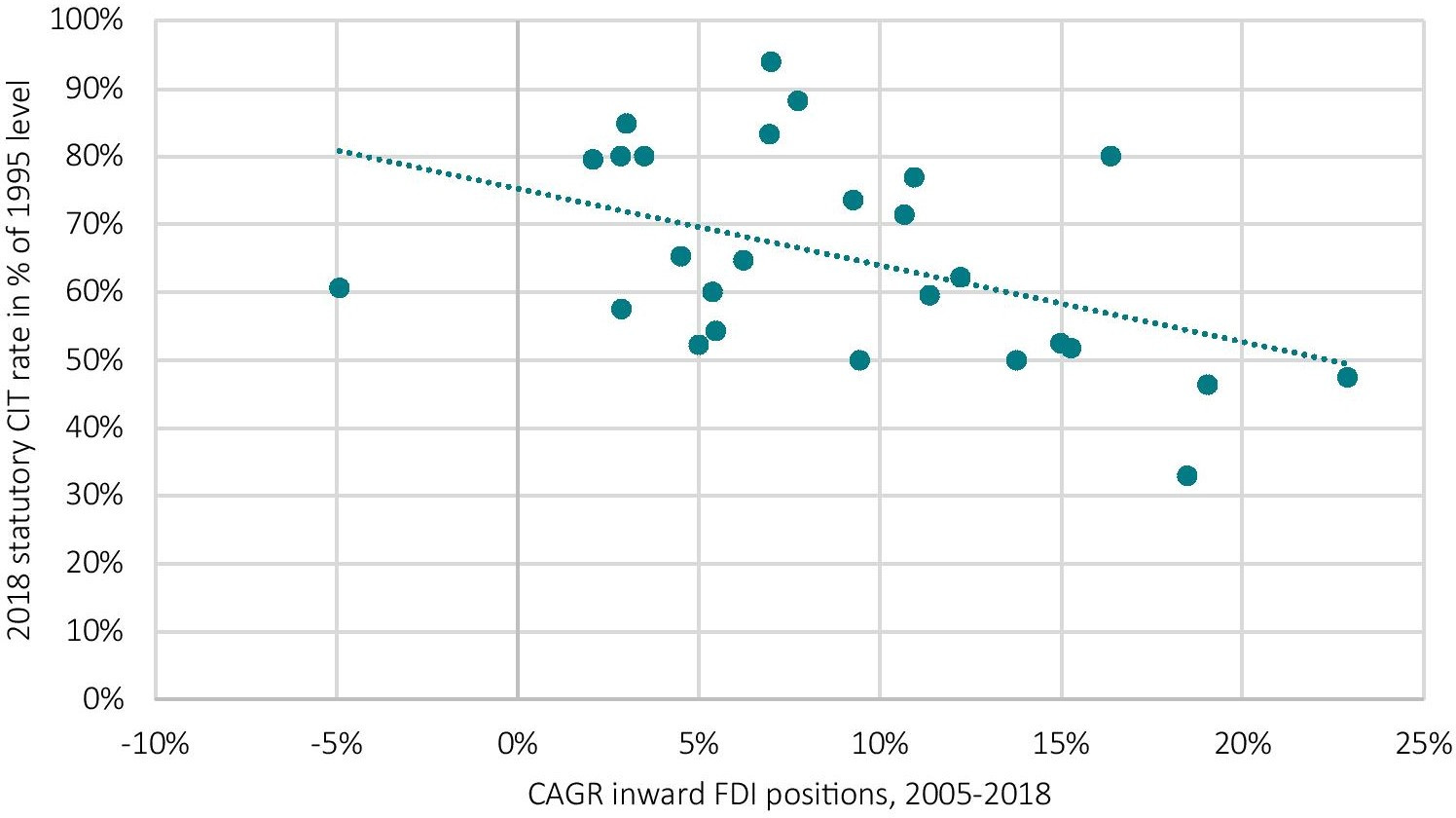

Everything else being equal, the losses in overall corporate tax revenues would decrease government budgets unless compensated by lower public spending or higher taxes on other sources of tax income, e.g. higher sales taxes or higher labour income taxes. At the same time, it should be noted that historical data suggest that reductions in corporate income tax rates have a positive effect on investment and overall economic activity, which would increase overall tax revenues over time. As outlined by Figure 11 to Figure 16, the reductions of statutory corporate tax rates by OECD countries since 1995 had a generally positive impact on corporate tax revenues, sales tax revenues, social security contributions (which are positively correlated with labour income tax revenues, for which OECD data is patchy), overall GDP growth as well as inward and outward FDI positions.

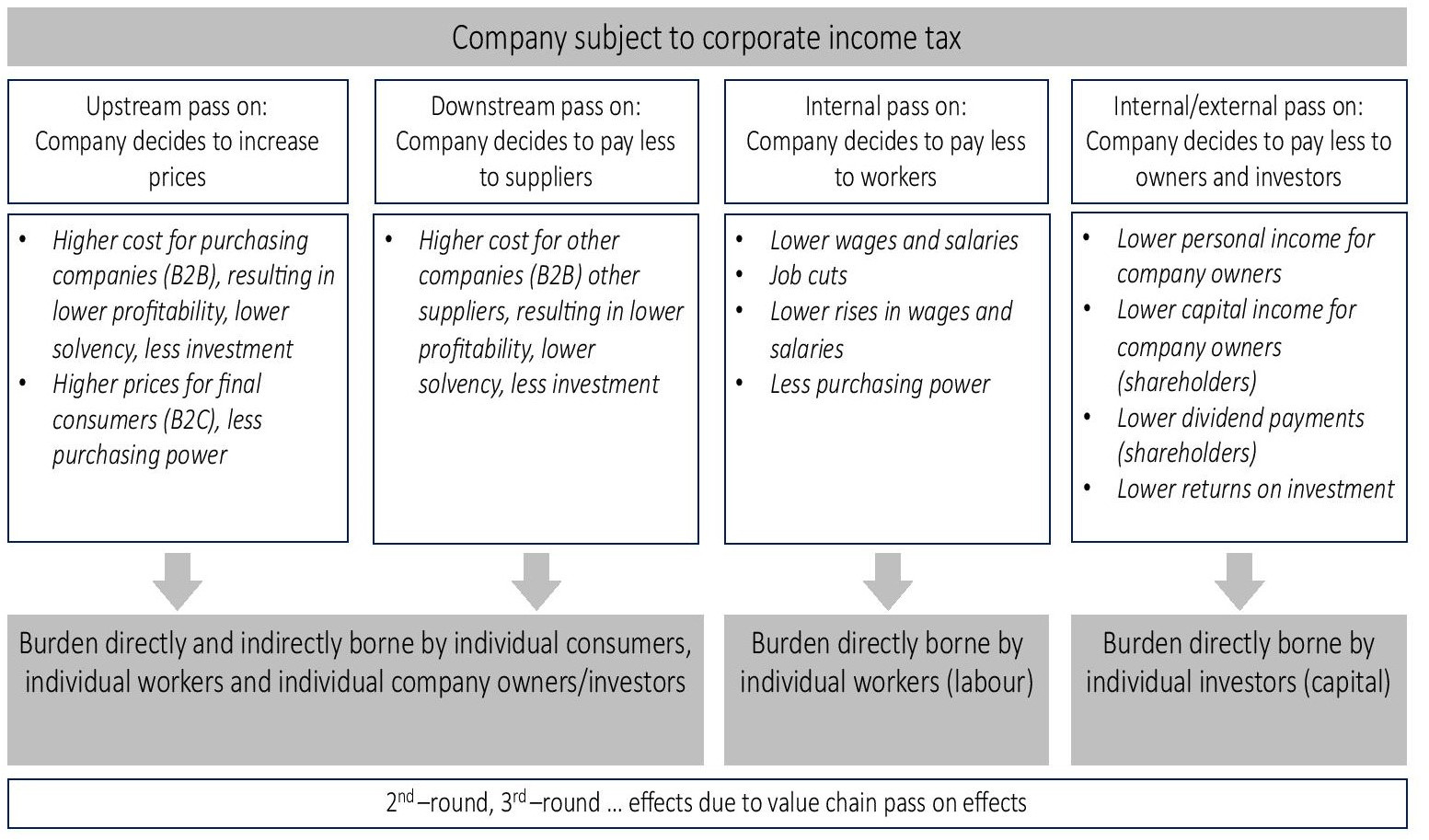

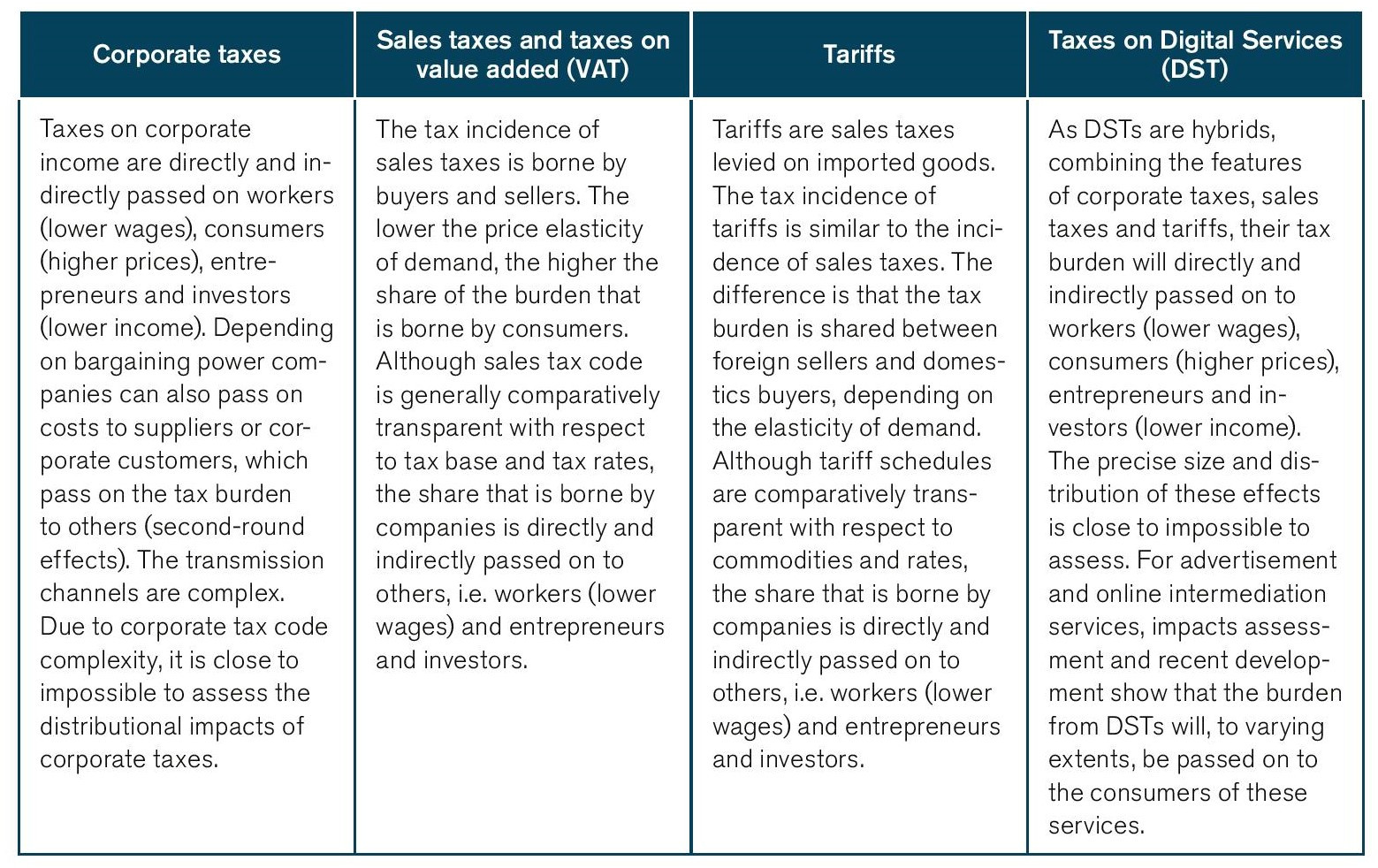

Overall positive economic and tax revenue implications from lower corporate taxes are also suggested by recent data provided by the OECD’s recent 2020 Corporate Tax Statistics report (OECD 2020c). However, these relationships are not consistent over time. Their magnitude is sensitive to country-specific characteristics, e.g. market size (economic gravity) and regulatory policies for domestic commerce as well as international trade and investment. At the same time, the mechanisms at work are largely the same for all countries, irrespective of geographical and institutional characteristics: a meaningful reduction of corporate income tax rates would increase the disposable income of companies. Lower taxes on corporate income would thus stimulate overall investment and commercial, i.e. income-generating activities, which have a positive impact on tax revenues from labour-income taxes, sales taxes and other taxes. Also, lower corporate taxes would decrease social policy distortions that arise from tax incidence effects. A lower corporate tax burden would increase the disposable income of workers over time, which would improve the degree of tax progressivity in the overall tax system (see, e.g. Fuest et al. 2018; Fuest 2015).[8] Figure 17 in Appendix V – Tax incidence effects) outlines the transmission channels for the incidence of taxes on corporate income. Similar considerations apply for sales taxes, tariffs and taxes on digital services, for which the economic costs and tax incidence effects are outlined by Table 13.

4.4. Interpretation of Results in Light of the OECD Proposals

Accounting for the tax sensitivity of FDI and governments’ continued incentives for tax competition, the above analysis reveals hypothetical bilateral FDI positions in the absence of tax rate differentials. The net effects for domestic investment are calculated for a hypothetical equilibrium in which all OECD countries have lowered their effective corporate tax rate to the OECD-proposed minimum rate of 12.5% (scenario 3).

In line with the findings of OECD (2017), it becomes obvious that the OECD’s corporate tax proposals would primarily benefit large OECD countries that currently apply relatively high statutory and effective corporate tax rates. The analysis suggests that large OECD countries with high effective corporate tax rates would gain most in FDI and tax revenues respectively. Large countries’ outward investment would decrease, while inward investment would increase if tax rate differentials narrow. The analysis does not include large non-OED countries such as China and India and large high-tax countries participating in the OECD’s Inclusive Framework (see Table 3). Small OECD countries, of which most apply relatively low effective corporate tax rates, would lose domestic investment and FDI-related tax revenues to the OECD’s largest economies. The estimated revenue gains and losses increase substantially if taxes FDI-induced revenues from taxes on personal income and social security contributions are taken into consideration. Similar considerations apply for non-OECD countries.

The 12.5% target rate may appear extreme given that most OECD countries, with the exception of Ireland and Hungary, currently apply much higher effective corporate tax rates. While it is very likely that governments across the globe will continue to lower their effective corporate tax rates, it is questionable whether governments will enter a corporate tax “race to the bottom”, which would be marked by the OECD’s 12.5% target rate. However, the results for scenario 3 would not change if a different target rate would be applied, e.g. 15% or 50%, as the net effect (from scenario 1 and scenario 2) depends on current and future tax rate differentials (see equation III above).

The estimations illustrate that lower-tax OECD countries’ future scope for tax competition would be limited by any lower bound threshold for the effective corporate tax rate. If high-tax countries gradually lower their effective corporate tax rates, lower-tax countries’ tax advantage would be squeezed, i.e. existing tax differentials would decline and, depending on the intensity of tax competition, may eventually disappear. At any rate, a narrowing of international effective corporate tax rate differentials works exclusively to benefit of large and very large countries with high effective corporate tax rates and at the expense of small open economies, particularly small open economies with low effective corporate tax rates.

Everything else being equal, for large countries with high effective corporate tax rates the positive impact of “economic gravity” on inward and outward investment would increase in relative terms over time, i.e. the marginal increase in domestic investment in a large country increases with the narrowing of the corporate tax differentials between the large country and small countries and vice versa. Importantly, this relative increase in attractiveness to foreign investors would not require the governments of large countries to improve the domestic business and investment climate in their countries, while at the same time governments’ marginal return from improving the business and investment climate in small countries would also decrease.

Would a narrowing of effective corporate tax rates contribute to a more efficient allocation of capital, as is suggested by the OECD? This answer to this question is clearly no.

First, governments will continue to compete on tax code characteristics to lower effective corporate tax rates, which is why tax-induced distortions will continue to prevail in the future, even more so if governments increasingly rely on obscure tax privileges which reduce effective tax rates in the domestic economy. This is highlighted by Devereux et al. (2020), who argue that “it appears likely that the GloBE proposal will not achieve its two primary objectives unless […] countries agree to a detailed set of harmonised rules; and (iii) the harmonised rules incorporate a strong form of minimum tax. Even then, it is not clear that some technical issues, such as those involved in the calculation of effective tax rates, can be solved.” (p. 2)

Second, a more efficient allocation of global investment would require more harmonised policies for trade and investment or, at least, much less discriminatory (protectionist) rules for international trade and investment. However, countries’ legal and institutional characteristics, which are presented in Section 3 ab, indicate that a narrowing of tax rate differentials would effectively shift taxing powers to the world’s largest countries, of which most perform poorly with respect to economic freedoms, openness to trade and investment and the state of the rule of law. In addition to tax policies, these are important policy factors that impact on multinational companies’ investment decisions (OECD 2017).

As outlined by OECD (2011), “[l]arge jurisdictions with agglomeration economies are less affected by tax base mobility and tend to set higher tax rates.” (p. 5) The same rationale is valid for regulations on trade and investment, which are much more restrictive in large countries than in small open economies (see above discussion and Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6). Accordingly, the shift of taxing powers away from and well-performing small economies to the governments of large countries with poor legal, political and governmental institutions may result in a much more inefficient allocation of capital over time as governments of large countries have much lower incentives than small country governments to compete for investment on the basis of good legal and governmental institutions. For business and citizens in the world’s largest and most protectionist countries, the OECD-proposed minimum corporate tax may therefore become a tax on longer-term social and economic development.

Third, higher corporate tax rates generally reduce companies’ “disposable income”, which decreases companies’ capacity to invest in R&D, new business models and (international) business expansion. The OECD’s own impact assessment comes to the conclusion that multinational companies’ total tax burden would increase as a result of the implementation of Pillar I and II proposals. Following the reasoning of the OECD, which does not account for continued tax competition among governments globally, the reform proposals would reduce the financial resources of companies, implying lower levels of domestic and international investment. As financial resources would be allocated away from businesses to governmental institutions, which spend tax funds according to political will, the reallocation of financial resources would likely generally result in a less efficient allocation of financial resources, particularly in countries that show high levels of corruption and cronyism.

Moreover, many R&D activities currently take place in countries that allow for special tax deductions or special tax treatment of losses carried forward. These and other measures are designed to encourage private sector investment and innovation. In economic lingo, tax incentives were explicitly designed to achieve a more efficient allocation of capital investments. Many large and small open economies actually allow companies to carry forward losses from R&D expenditures, which lower companies’ taxable income in subsequent years (and significantly impact on companies’ actual effective tax rates). Due to their economic and political clout, the governments of large countries could use their political leverage to challenge such behaviour under the OECD’s new rules for Pillar I and II. The OECD’s reforms would thus undermine tax practices that are intended to stimulate investment and innovation, particularly in small open economies.

The implementation of the OECD’s reform proposals is likely to result in a rising number of disputes between governments over the calculation of multinational enterprises’ annual profits and the number of years to net losses against future profits, which can have significant implications on how much and where companies invest in R&D in the future. Accordingly, for small open economies that are home to research- and knowledge-intensive multinational combines, the OECD’s proposed tax reform could undermine investments in R&D, innovation and business model development, with adverse implications on existing research clusters, education systems and high value-added jobs.

[1] It should be noted that this publication does not represent “the official views of the OECD or of its member countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author(s).” (p.1)

[2] The semi-elasticity indicates the percentage change in FDI associated with a one percentage-point change in taxes. A change in the semi-elasticity would change the size of the estimated effects proportionally, but the relative revenue effects will be unchanged.

[3] The tax sensitivity of FDI generally varies for countries as well as sectors and business models. Ballpark numbers or “consensus estimates” such as the ones applied by OECD (2017) and used in this study are indicative and should not be taken by face value. “Studies examining cross-border flows suggest that on average, FDI decreases by 3.7% following a 1 percentage point increase in the tax rate on FDI. But there is a wide range of estimates, with most studies finding decreases in the range of 0% to 5%. This variation partly reflects differences between the industries and countries being examined, or the time periods concerned.” (OECD 2008, p.2) It should be noted that the tax rate equalisation effect of scenario 3 does not require the effective tax rate to be 12.5%. Tax rate equalisation would also take place at any tax rate including very low or very high tax rates. However, the level of effective tax rates also impacts on the level of semi-elasticities. The higher the corporate tax rate the higher the decrease in investments and vice versa.

[4] The authors of OECD (2017) encountered the same problem, stating that “[t]he coverage of FDI data increases over time and some observations are missing. This is especially true for FDI positions and flows between OECD countries and non-OECD countries. Thus, changes in FDI over time should be interpreted with care, because some of the observed variations might reflect changes in data coverage and not real changes in FDI. The effects of taxes reported in this paper might underestimate the actual effects due to missing observations. However, for the countries included in this study the coverage of bilateral FDI data is fairly good after 2006, so this bias is likely to be small.” (p. 11).

[5] In OECD (2017), the authors used statutory corporate tax rates due to data coverage.

[6] We apply the OECD’s 2017 estimates for effective corporate tax rates, which are based on a harmonised methodology. ZEW (2019) does not provide data for the full sample of OECD countries.

[7] Businesses generate economic activity, which generates revenues from labor income taxes and social security contributions. Taxes on payroll and workforce covers taxes paid by employers or the self-employed either as a proportion of payroll or as a fixed amount per person, and which (unlike social security contributions) do not confer entitlement to social benefits. Social security contributions cover compulsory payments to general government by individuals or businesses that confer an entitlement to receive a contingent future social benefit. In most countries, social security contributions are applied to both an employer’s payroll and an individual’s wages (see, Milanez (2017).

[8] As argued by Fuest et al. (2018, p. 1) “[a]ccording to surveys, most people think that capital owners bear the burden of corporate taxation”. By contrast, the authors find that workers bear about half of the total economic burden resulting from a tax change, whereby low-skilled, young and female employees bear a larger share of the tax burden. The authors highlight that, overall, the findings indicate that taxes on corporate income reduce the progressivity of the overall tax system. Accordingly, and different to the notions of most policymakers and tax justice activists, corporate tax avoidance can increase the progressivity of the overall tax system.

5. Conclusions

The reforms proposed by the OECD would impact where large multinational companies produce and invest in the future. The above analysis has shown that continued tax competition would contribute to a narrowing of international corporate tax rate differentials up to the 12.5% minimum tax threshold level proposed by the OCED. The narrowing of tax rate differentials between today’s high-tax jurisdictions, of which most are very large countries, and today’s low-tax jurisdictions, which are exclusively small open economies, would direct international and domestic investments and investment-induced tax revenues away from small countries. Overall, the shift in effective taxing powers would undermine small countries’ attractiveness to international businesses and, in addition, induce domestic businesses to relocate to larger countries with the economic gravity of larger markets.

Contrary to claims made by the OECD, the implementation of Pillar I and II proposals would not improve the global allocation of capital. Global trade and investment flows would still be subject to tax competition and widespread trade and investment barriers. The OECD’s current proposals would likely incentivise the governments of large countries to maintain long-standing barriers to trade and investment or to erect additional barriers that would restrict market access for companies from small open economies. For small open economies that are home to research- and knowledge-intensive multinational companies, the OECD’s proposed tax reforms would undermine future investments in R&D, innovation and business model development, with adverse implications for existing research clusters, education systems and high value-added jobs.

The investment relocation mechanisms at work under Pillar II are similar for those that can be expected for Pillar I. Additional or higher corporate taxes in market jurisdictions would increase the effective corporate tax rate of a company to an extent that may cause a competitive disadvantage as compared to competitors headquartered in jurisdictions with lower effective corporate tax rates. A higher group-wide tax burden may therefore cause companies to reconsider their overall international investment positions including their country of headquarter. Confronted with such situations, governments may need to reconsider their effective corporate tax rates if they want to keep successful international businesses in their country. They may adopt lower statutory tax rates or new measures intended to lower their effective tax rates.

The high level of variation in countries’ corporate tax codes demonstrates that governments actively encourage internationally operating companies to lawfully reduce their (global) corporate tax bills. The measures proposed by the OECD would not stop future governments from lowering their countries’ effective corporate tax rates. The measures proposed by the OECD would also fail to address a systemic problem of corporate tax law: enormous legal complexity and tax law obfuscation:[1] corporate income taxes are at the heart of numerous inefficiencies. They are at the root of double taxation for multiple sources of individual incomes. As a result of the economic incidence, taxes on corporate income depress the real income of workers, consumers and entrepreneurs. More corporate tax avoidance would have a positive impact on households’ disposable incomes and, due to the sensitivity of low-skilled workers, tax progressivity respectively (see Fuest et al. 2018).

The OECD’s recent proposals for international corporate tax reform would add another complex layer of tax law to non-transparent corporate tax regimes whose actual distributional effects on workers, consumers and company owners are currently almost impossible to assess. The adoption of the OECD’s reform proposals would cement corporate tax-induced wage depression and shield complex national corporate tax regimes that are incomprehensible for most citizens and politicians. Policymakers in small and large countries should be wary of the path dependency in corporate taxation, i.e. the historical pattern that tax complexity bred further tax complexity, effectively taking corporate tax rules out of the control of taxpayers and elected lawmakers.

Given the path dependency of national tax systems and the political economy barriers to reform, tax competition is the most promising way to achieve simpler and more transparent tax systems globally. Any multilateral limitations on tax competition would impede the evolution of modern, i.e. simpler and more transparent, tax systems that stand a chance of being considered fairer by countries’ local populations. Policymakers should reconsider whether taxes on corporate income actually contribute to governments’ overall social and economic policy objectives, such as economic development, redistribution and fairness in taxation.

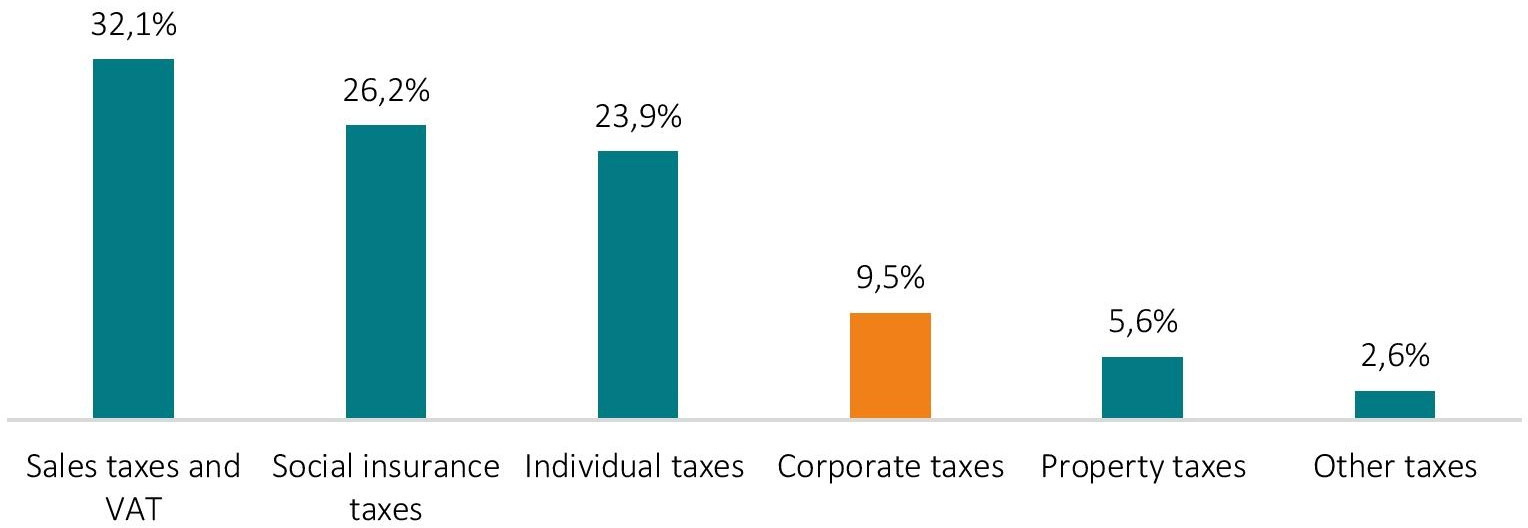

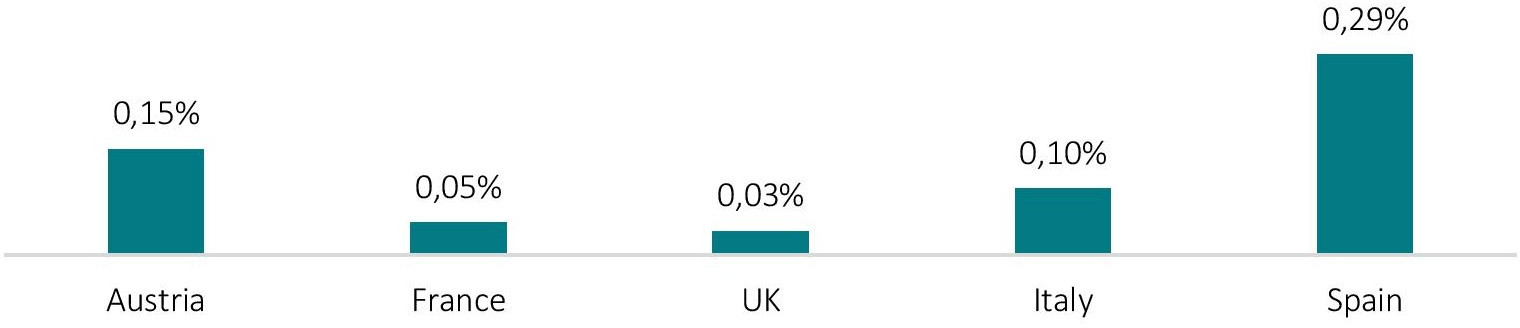

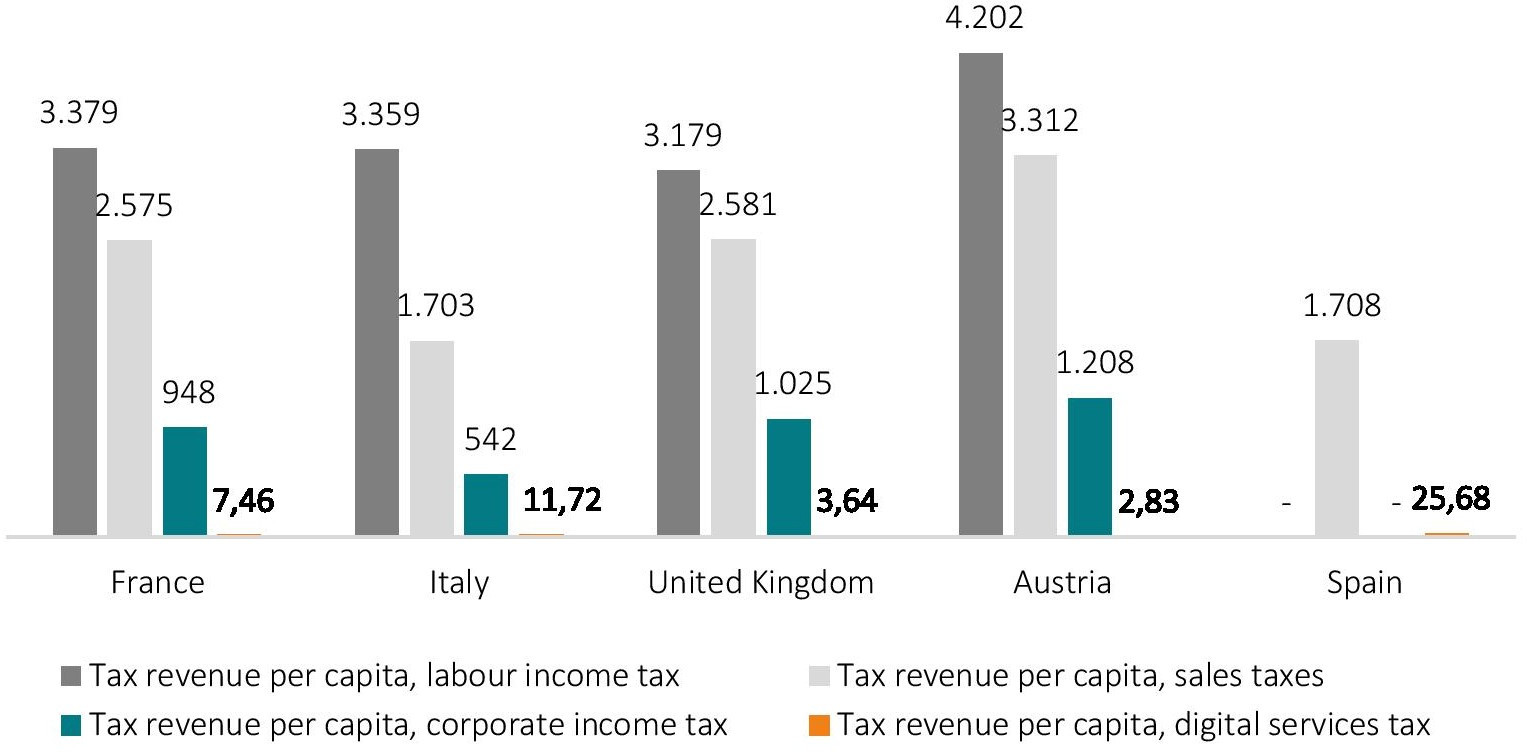

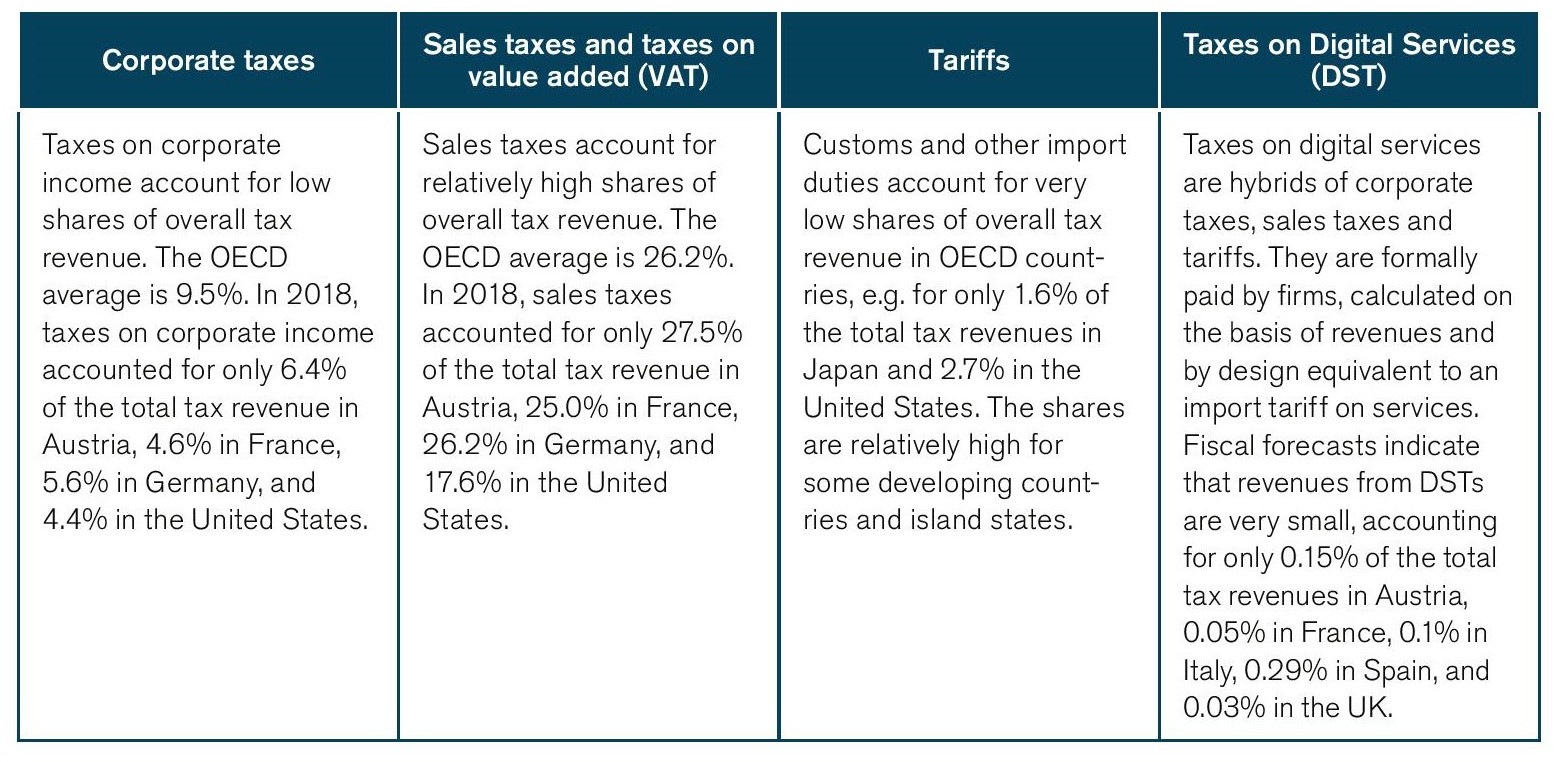

As outlined by Figure 7, taxes on corporate income account for only 9.5% of OECD countries total tax revenues. Similarly, as shown by Figure 8, new taxes on digital services would also account for very low – de facto negligible – shares on governments’ total annual tax revenues. As shown by Figure 9, this order of magnitude is generally mirrored by countries tax revenues per capita values. Against this background, policymakers should consider replacing corporate income taxes by taxes on consumption to generate tax revenues from economic activities and user participation, including user participation in certain locations. As argued by ZEW (2020) and others, value added taxes (VAT) and sales taxes are a suitable (and already available) tool to tax consumption in market countries. Sales taxes already account for relatively high shares of overall tax revenue (see also Table 14). Enforcing VAT/sales taxes on both digital services and less digital sectors of the economy would allow governments to generate and sustain tax revenue in market jurisdictions.

Replacing tax systems that include taxes on corporate income by systems that rely more or exclusively on direct taxes on labour income, capital income and consumption (VAT/sales taxes) would not only increase transparency about the distributional effects of taxation; it would also significantly improve governments’ tax manoeuvrability in response to citizens’ preferences for fairer taxation. A regime change towards greater use of VAT/sales taxes would also have a positive impact on global capital allocation: companies would no longer have to pay attention to corporate income tax rate differentials, while governments would have additional incentives to embrace foreign trade and investment, materialising in lower barriers to trade and investment and a more efficient allocation of global capital respectively.

Figure 7: Tax revenue in total tax revenues, OECD countries, 2018

Source: OECD, Tax Foundation. Note: individual taxes include taxes on labour income and taxes on capital income. For Greece, only the aggregate of taxes on income, profits and capital gains was available for the year 2018. To split this aggregate into the three categories Individual Income Taxes, Corporate Income Taxes and Other Income Taxes, the average of the distribution of these categories in the three years prior (2015-2017) was used.[2]

Figure 8: Government-estimated tax revenues from special taxes on digital services as share of total annual tax revenues from 2018

Source: revenues projections of national finance ministries. OECD tax revenue data for 2018. Note: for Spain, the technical experts’ union at the Finance Ministry stated that this forecast “could be an overestimate.”

Figure 9: Annual tax revenue per national citizen: labour income taxes, sales taxes, corporate income taxes, digital services taxes (DST), in EUR

Source: ECIPE calculations based on Eurostat tax and World Bank population statistics from 2018. DST estimates based on national governments’ own fiscal forecasts. Note: the government of Spain does not report revenues for corporate income tax and labour income tax. For the Spanish government’s DST proposal, the technical experts’ union at the Finance Ministry stated that this revenue forecast “could be an overestimate.”

[1] In software development, obfuscation is the deliberate act of creating source or machine code that is difficult for humans to understand.

[2] The data is available at: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RS_GBL.

References

Bénassy-Quéré, A., Fontagné, L. and Lahrèche-Révil, A. (2005). How Does FDI React to Corporate Taxation? International Tax and Public Finance. International Institute of Public Finance, vol. 12(5), p. 583-603.

Devereux, M., Bares, F., Clifford, S., Freedman, J., Güçeri, I., McCarthy, M., Simmler, M. and Vella, J. (2020). The OECD Global Anti-Base Erosion Proposal. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation. Report was commissioned by PwC.

ECB (2017). Determinants of FDI inflows in advanced economies: Does the quality of economic structures matter? ECB Working Paper Series, No. 2066, May 2017.

Englisch, J. and Becker, J. (2019). “International effective minimum taxation – the GLOBE proposal” World Tax Journal 11.4, 5.

Feld, L. P. and Heckemeyer, J. H. (2008). FDI and Taxation – A Meta-Study. ZEW Discussion Paper 08-128.

Fischer, L., Klein, D., Ludwig, C., Müller, R. and Spengel, C. (2020). Global Corporate Tax Re-form to the Worse? – Assessing the OECD Proposals. ZEW Policy Brief No 1, February 2020.

Fuest, C., Peichl, A. and Siegloch, S. (2018). Do Higher Corporate Taxes Reduce Wages? – Micro Evidence from Germany. American Economic Review, Vol. 108, No. 2, February 2018.

Fuest, C. (2015). Who bears the burden of corporate income taxation? ETPF Policy Paper 1. Available at http://www.etpf.org/papers/PP001CorpTax.pdf.

Hebous, S., Klemm, A. and Stausholm, S. (2019). Revenue Implications of Destination-Based Cash-Flow Taxation. IMF Working Paper 19/7. International Monetary Fund.

Keen, M. and Konrad, K. A. (2012). The Theory of International Tax Competition and Coordination. Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance Working Paper 2012 – 06 July 2012. Available at http://www.tax.mpg.de/RePEc/mpi/wpaper/Tax-MPG-RPS-2012-06.pdf.

Klemm, A. and Liu, L. (2019). The Impact of Profit Shifting on Economic Activity and Tax Competition. IMF Working Paper 19/287. International Monetary Fund.

Langenmayr, D. (2020). Panel contribution at debate hosted by DIW Berlin. OECD Berlin Centre Blog. 8 June 2020. Available at https://blog.oecd-berlin.de/internationale-unternehmensbesteuerung-im-digitalen-zeitalter-reformplane-und-mogliche-effekte.

Milanez, A. (2017). Legal tax liability, legal remittance responsibility and tax incidence: Three dimensions of business taxation. OECD Taxation Working Papers No. 32. Available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/legal-tax-liability-legal-remittance-responsibility-and-tax-incidence_e7ced3ea-en.

OECD (2020a). Statement by the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS on the Two-Pillar Approach to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy. 31 January 2020. Available at www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-by-the-oecd-g20-inclusive-framework-on-beps-january-2020.pdf.