The Swiss Cheese of Trade Policy: The Case Against Product Exclusions in Trade Agreements

Published By: Fredrik Erixon

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements WTO and Globalisation

Summary

There have been calls to exclude certain products from trade agreements because they cause damages to public health or the environment. Lately, campaigns for product exclusions have included chemicals (generally or specific chemicals like glyphosate), sugary drinks and candy (or sugar generally), and alcoholic beverages. Previously the same case has been made for tobacco products. In this paper, it is argued that product exclusions are neither legally feasible nor desirable. Measures to exclude products would run foul of the rules and market-access commitments that countries have agreed in the WTO, and that serve as a basis also for other trade deals, like bilateral Free Trade Agreements. Importantly, excluding products from current market-access commitments in the WTO would per se do nothing with regard to public health because the main effect is that local production of the excluded goods would substitute goods that are now imported. The conclusion is that trade policy is not a tool for regulatory ambitions. Nor does it stand in the way for regulations that aim to improve public health. Trade policy concerns trade, and the instruments and agreements that exist for the pursuit of better and less-discriminatory trade conditions simply cannot be used for sundry regulatory proposals, however relevant they may be.

Introduction

The purpose of trade policy is to improve the conditions for economic exchange in the world by reducing barriers to trade and taking away discrimination of goods and services. For any long-term observer of trade policy, that statement is so obvious that it neither needs clarification nor explanation. Trade policy is about – trade. However, in the more recent debate around trade, there have been calls to upend decades of international trade policy and rules by simply taking away various types of goods and services from international trade agreements – either by excluding products from current schedules of commitments in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), or not including them in future FTAs. It has been argued that, principally, products that cause damages to health or the environment should not get the embrace of trade rules that protect against arbitrary and discriminatory practices, and that they should not be covered by agreements that have cut or are cutting tariffs. In the extreme version, the view is that past concessions in trade agreements – the conditions that governments voluntary have signed up to – should be nullified. Ultimately, it means stopping trade in these particular goods.

This is a ‘Swiss cheese’ approach to trade agreements: certain products would be exempted from trade disciplines and liberalization. It would be a radical approach and overturn trade policy and rules that are based on the general principle in trade agreements to progress increased openness across different sectors – without picking out specific products for the embrace of or the exclusion from liberalisation. Liberalization has of course not been advanced at the same pace in all sectors; the gradual reduction of tariffs over the years has varied between goods, and even if the direction has been similar across sectors, the pace of tariff reductions have been different. But there has been a growing consensus on the need to converge trade openness between various types of goods. An important reason behind that consensus is that an increasing number of the products that are traded are input rather finished goods, and that finished goods that are traded include many different inputs. Simply, a restriction on one type of good would affect trade in a host of other goods and services. The more companies have designed their supply chains in a globalized and fragmented way, all the more sense it has made to look at broad multi-sectoral liberalization. Today, a finished product is based on a huge accumulation of cross-border trade in inputs, and in order to generate significant gains from liberalization, there will have to be liberalization in many, if not all, parts of the supply chain to also lower the effective tariff or barrier.

Another key reason behind the growing consensus of multi-sectoral liberalization concerns political economy – or, in plain speak, the conditions that are required for multiple governments to actually come to an agreement on trade. If bilateral or multilateral trade policy would only deal with a selected number of goods and services, there would be a number of countries that couldn’t enter trade agreement because the products they care most for wouldn’t be included in the agreement. At a broad headline level, it would be impossible for countries that are exporting food and food staples to enter a trade agreement that doesn’t cover the liberalization of those products, let alone an agreement that worsens trade openness for food and food staples. And in a similar fashion, trade agreements that would exclude industrial goods from new exporting opportunities would be a red blanket for many countries with strong trade capacities in that particular area.

The viewpoint now, however, is that – regardless of the consequences for trade policy – certain products should be excluded from new trade agreements and/or lose their rights in current trade agreements because they are detrimental to health or the environment. Admittedly, that view is not entirely new because there has been calls over a long period of time to exclude tobacco products from trade agreements. But the scope of the argument has radically widened and there are now campaigns for excluding from trade agreements products such as chemicals – in general or specific chemicals like glyphosate – alcohol, sugary drinks, candy and food products that contain higher levels of salt. The basis for the exclusion may vary a bit, but the conclusion is the same: these goods should ideally lose their current status in current agreements in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and, pointedly, they should not be considered in the scope of new trade agreements.

This Policy Brief will consider the arguments behind excluding products from existing and new trade agreements. The paper, however, takes a critical view of these arguments and arrives at the opposite conclusion: for new trade agreements to be economically meaningful – and, in the first place, achievable – liberalizing measures need to be broad and multi-sectoral, and the rules that underpin trade agreements should apply across the board. FTAs should follow the principle of liberalizing “substantially all trade” and naturally work from the basis of the schedule of commitments in the WTO.[1]

There is a case to be made for having rules and liberalizing measures that attend to the different regulations that exist in countries for products that could cause harm to health and the environment – regulations that are specifically about public health and the environment, but that do not distort the competitive relation between domestically-produced goods and foreign goods. However, that is a different issue and is already a central plank of rules and measures in all modern trade agreements, including the core agreements in the World Trade Organization. Joint work by the WTO and the World Health Organization have also helped to clarify the scope for domestic regulation in the area of public health.[2]

It is the core argument of this paper that in matters related to products that are detrimental to health or the environment, trade agreements basically allow for countries to impose stronger regulations as long as they don’t discriminate and have the consequence of giving domestic producers an advantage over foreign producers. Trade policy is not and never has been a regulatory policy that directly addresses specific concerns for public health or the environment. Nor could it be. An effective policy on protecting the environment, addressing obesity or reducing smoking – to take just three examples – includes many different measures such as tax and product and sales regulations. Taking away products from trade agreements, however, does not change the content of these taxes and regulations: it only means that domestic producers will substitute foreign producers.

The next chapter will consider international trade rules and how matters of regulation are dealt with internationally. Chapter 3 steps into the world of trade substitution and shows how limiting trade in certain products would only reshuffle production and favor protected firms at home against foreign companies. Chapter 4 concludes the paper. Generally, and to make the paper less wieldy, most elements of the analysis are anchored in a European economic and policy context.

[1] GATT Article XXIV states: “A free-trade area shall be understood to mean a group of two or more customs territories in which the duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce (except, where necessary, those permitted under Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XX) are eliminated on substantially all the trade between the constituent territories in products originating in such territories”.

[2] WHO and WTO (2002) WTO Agreements and Public Health: A Joint Study by the WHO and the WTO Secretariat. Geneva: World Trade Organization

International Trade and Regulatory Objectives

There is an underlying assumption in the commentary by some campaign groups that excluding certain products from trade agreements is necessary in order to progress domestic regulation and make trade agreements to service the greater good. This argument has in Europe been employed recently to make the case for excluding in trade agreements products that are detrimental to health and the environment, for instance certain chemicals, sugary drinks and tobacco. In order to analyze the arguments, and put them in a context of international trade agreements, we will divide this chapter into different sections because they are thematically and legally different.

First we will discuss the growing trend in Europe and across the world to regulate products. What we will show is that the products under discussion are increasingly subject to regulation (and, for some products, taxation) and that increasing regulation is not in conflict with rules and measures in international trade agreements.

Second we will discuss how international trade rules address barriers to trade for products that are regulated. This is a key section because the case for excluding products such as chemicals and sugary drinks in trade agreements effectively concerns products that are allowed to be placed on markets and that have been explicitly covered in all trade agreements in the past. Furthermore, the calls in Europe for certain product exclusions typically concerns products that are also produced in Europe, leading to obvious problems of direct product discrimination.

Third we will discuss why a global agreement to change existing trade agreements with the consequence of excluding products would be legally possible but politically unrealistic.

2.1 Regulatory Trends for Certain Products

The regulatory landscape for products that cause harm to public health and the environment vary. Many products, like chemicals, are subject to a regime of testing and authorization, with the view of establishing a scientific basis for how that product could be used, and what restrictions that should be applied on the product, usage, and waste arrangements. A product like glyphosate, for example, is subject to a market approval – or a license – that regularly has to be renewed and, in that process, go through a scientific review. Alcoholic beverages and tobacco products are subject to tax regimes that aim to reduce the consumption of these products, and most countries apply restrictions on whom that can buy these products and where they can be sold. Sugary products like sodas and candy are not confronted by such regulations, but VAT rates in some countries are higher on these products than on other beverages and there has been attempts at different ‘sugar taxes’ with the purpose of lowering the consumption of these products.

It is notable that there are very few examples of trade disputes concerning the shape and design of domestic taxes and regulations that aim to reduce the consumption of products that cause harm to public health. Despite substantial variation between countries in how they have chosen to regulate products, these have not been matters for dispute resolution. The disputes that have taken place mostly concern domestic taxes and regulations that have been discriminatory – where a government have advanced a regulation or a tax but applied it differently to imported products than to domestically-produced products.[1] The fact that there has not been many disputes is all the more indicative in light of the regulatory development over the past decades. For most of the products that are referenced in debates over product exclusions in trade agreements, there has been an increase in the burden of regulation and taxes, especially for chemicals, alcoholic beverages and tobacco products. Taxes have not changed much for chemical products, but the regulatory demands on chemicals have increased substantially.

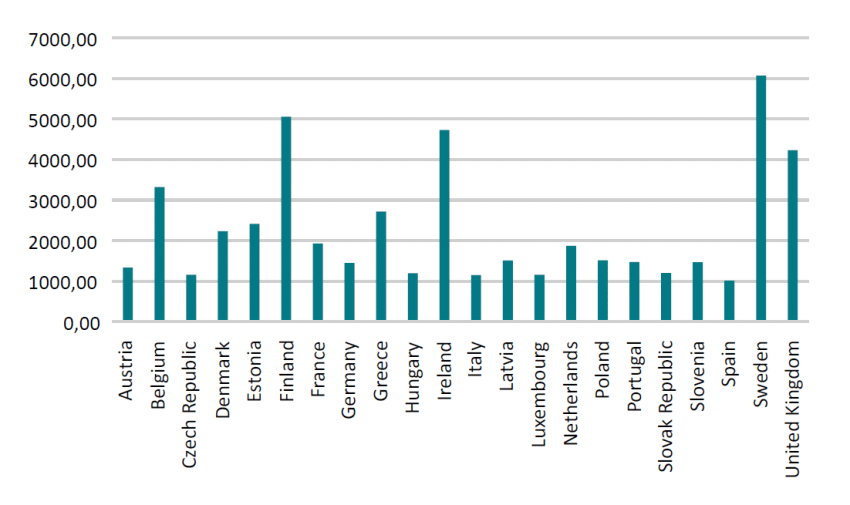

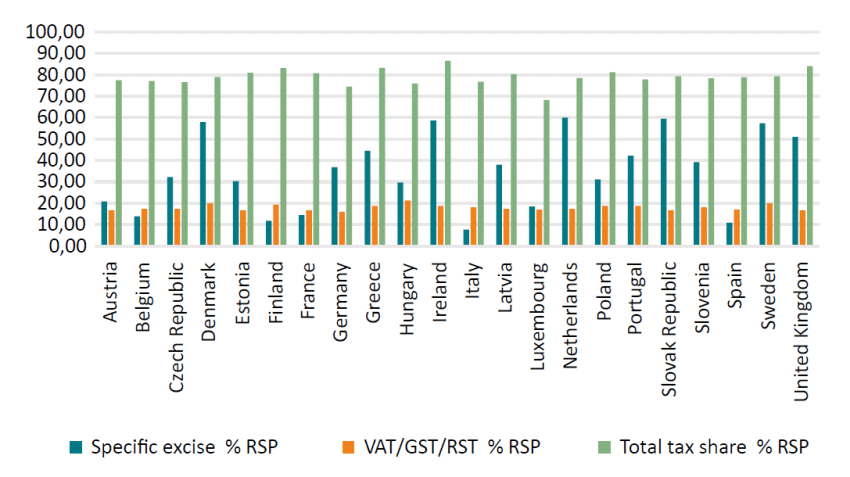

The tax burden for alcoholic beverages and tobacco products have increased and is generally high. In the EU, the average tax burden on tobacco products is about 79 percent, when both excise taxes and VATs are included (see table 2).[2] The excise tax on an hectoliter or absolute alcohol in the EU averages at about 2850 USD, and on top of that comes VAT that vary between 17 and 27 percent. In the past ten years, more than half of all EU members have raised the combined tax rates on alcohol. There is a discussion about the extent to which nominal duties have risen enough to effect the real tax burden, but that varies much between countries and there are many special circumstances that apply, such as the level of economic growth and inflation.[3] Given the established link between the total tax burden and consumption, the variation between EU countries also points us in the direction of what policy governments should apply if they like to reduce consumption by policy means: raising excise duties.

Table 1: EU Excise Duties on Alcohol (per hectoliter of absolute alcohol), 2016

Table 2: Tobacco Taxes as Share of Retail Sales Price

Source: OECD; The European Commission; World Health Organization

Source: OECD; The European Commission; World Health Organization

In Europe, taxation of products such as alcohol and tobacco are anchored in EU directives that mandates consumption taxes. In the case of tobacco, the EU requires member states to have an excise duty in the range of 7.5-76.5 percent, and in real terms the duty must be at least 90 EUR per 1000 cigarettes and 60% of the weighted average retail selling price. Other tobacco products are subject to similar rules, and the specific demand on an excise tax burden has been increasing through rules in EU directives.

In its essence, taxation of harmful products aims to depress consumption and to increase the price elasticity of harmful products. Tax rates can therefore vary between different categories of, say, alcohol, and for some it is not just important to reduce consumption but to steer consumption away from some categories of alcoholic beverages to others. What is more, these type of policies usually come with strong economic and public-health evidence, which means that there is a scientific basis for legislation that controls consumption. This is important in the context of trade policy because general consumption restrictions do not discriminate between domestic and foreign goods, and in the scenario where a consumption restriction only affects foreign-produced goods, because there is no domestic production, there cannot be a complaint that a consumption restriction is a restriction on trade if the scientific basis for controlling measures are strong.

Regulations have also increased over time and, for some products, more so in the past decades than previously. This is particularly true for chemicals. After the introduction of the REACH legislation in Europe in 2007[4], all chemicals have had to go through mandatory testing and for those with clearly established hazards, the regulatory restrictions have increased substantially. In any cases, licenses and market approvals now set specific threshold limits that cannot be exceeded, and those thresholds are established on the basis of scientific evidence and the precautionary principle. As a consequence, the exposure to hazardous chemicals – either in the production or the consumption of a product – is very different today compared to the period before the entry of REACH.

Tobacco products have also been subject to increased regulation. European countries have for long been required to have controlling measures on the sales, marketing and taxation of tobacco products, but the Tobacco Products Directive from 2014 ushered in new restrictions. There is now stronger regulations on flavors and ingredients in tobacco products, with the purpose of making cigarettes less attractive. There are also new regulations on health warnings on tobacco packages – and what type of tobacco packages that could be put on the market (e.g. size limitations). Furthermore, the directive allows countries to introduce new bans on internet sales and opt for so-called plain-packing regulations that prevent a producer from displaying its brand on the tobacco package.

New EU rules have also been tested in courts, who have found these new restrictions to stand up to existing law on commercial and treaty rights. A non-EU case of plain packaging has also been subject to complaints in the WTO because of allegations that plain-packaging rules erodes rights under the TRIPS-agreements. However, the complainants have not won that case, even if there´s a pending appeal before the WTO Appellate Body.

On top of the EU directives comes national legislation on tobacco control. They vary between countries but routinely and in most countries include measures like sales, display and usage restrictions. The use of tobacco products in restaurants or public places are restricted in many countries. Tobacco products can only be sold at certain places. There are also age restrictions for tobacco products. When all these measures are added up, the obvious conclusion is that, firstly, regulatory restrictions on tobacco products are generally high and, secondly, that they have been increasing. We cannot find any example in the past ten years when the EU governments have introduced liberalizing measures on tobacco products. There are, however, thousands of registered examples of increasing regulatory restrictions.

The conclusion that can be drawn is that there is no principle conflict between trade rights and trade agreements, on the one hand, and existing measures to reduce the consumption of harmful products, on the other hand. Governments and the European Union have been introducing many different regulatory measures and can continue to raise taxes and impose regulations without their being any need to renege or nullify concessions given in international trade agreements.

2.2 Product Exclusions of Legal Products

Let us now turn to the case for excluding products in international trade agreements – existing or future – and carve out those from market-access commitments and rules in the WTO and FTAs – and why this is undesirable. The previous section already established that trade rules do not stand in conflict with ambitions and the practice of increasing the regulation of products like alcohol, beverages, chemicals and tobacco, or seeking to reduce the consumption of these types of products. Hence, the task now is not to consider whether more regulation is warranted or not, but if these products actually could be excluded from trade agreements without erring against obligations in international trade agreements.

We start with the World Trade Organization, and its General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, because the commitments that countries have made in the WTO are strong disciplines on the way governments operate their trade policy and also serve as the basis for other trade agreements.[5] Declarations from those groups that argue in favour of product exclusions propose that such measures are WTO consistent. While there are admissions about the risks of direct discrimination, these are seen as less important as it is alleged that Article XX of the GATT – which gives signatories the right to take measures that would otherwise be inconsistent with the GATT if such measures are “necessary” and has demonstrable good consequences for public health and the environment – gives sufficient cover. Hence, a possible WTO dispute would authorise a government, or – in the European case – the EU to exclude products from its rules and market-access commitments in the WTO.

However, this view is based on a very selective reading of GATT agreements and what they actually entail. An exemption based on Article XX is not a free pass for any sort of policy with implications for trade and the obligations that members of the WTO have to observe and respect. It is correct that GATT Article XX suggests that measures that are “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health” are compliant with the entire GATT agreement, but the main point of this article – established already in its preamble – is that such measures cannot be “arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination” or “a disguised restriction on international trade”.

Apart from the Article itself, there is also a fairly significant body of case law which has set precedents on the application of so-called General Exception Article (Article XX). Examining the consistency of product exclusions with this jurisprudence is a necessary test, but it is also a difficult one for those supporting product exclusions because exclusions would be erring on the wrong side of core GATT rules and the WTO panels have been very clear about separating legitimate regulatory concerns from direct discrimination.

Let us consider in greater detail the relevant Articles in the GATT that a product exclusion regulation in a country would violate. There are three core GATT articles of relevance: Articles I, III and XI.

GATT Article I. GATT Article I concerns treatment of like products. It sets out one of the core principles of the GATT/WTO system: like products should be treated equally. In the words of the Article:

“With respect to customs duties and charges of any kind imposed on or in connection with importation or exportation or imposed on the international transfer of payments for imports or exports, and with respect to the method of levying such duties and charges, and with respect to all rules and formalities in connection with importation and exportation, and with respect to all matters referred to in paragraphs 2 and 4 of Article III, any advantage, favour, privilege or immunity granted by any contracting party to any product originating in or destined for any other country shall be accorded immediately and unconditionally to the like product originating in or destined for the territories of all other contracting parties.” [emphasis added]

This article is important for any member of the WTO that would seek to exclude a product and withdraw established rights for other countries to export that product to them. The central issue is that a measure that reduce or close market access would confer advantages to domestic producers that are not covered by the exclusion of the product in a trade agreement.

“Likeness” is not defined in the GATT. Case law, however, offers interpretations. Two unadopted Panel reports have ruled that products are not unlike just because there are differences in production methods, when these differences do not affect the physical characteristics of the final product.[6] Even if these reports were unadopted, they can, as later cases have shown, be a “useful guidance”[7], especially as they have never been opposed in subsequent cases.

In rulings from the Appellate Body (AB), four criteria have consistently been used to define likeness. These criteria derive from the GATT Working Party in 1970:[8]

- The properties, nature and quality of the products; that is, the extent to which they have similar physical characteristics.

- The end-use of the products; that is, the extent to which they are substitutes in their function.

- The tariff classification of the products; that is, whether they are treated as similar for customs purposes.

- The tastes and habits of consumers; that is, the extent to which consumers use the products as substitutes – determined by the magnitude of their cross elasticity of demand.

None of these criteria provide legal cover for product exclusion. In fact, they make it pretty obvious that a product exclusion would deal with directly substitutable products that are like. The physical “properties” or “characteristics” of a can of soda, a chemical or a package of cigarettes are the same between similar products that are produced in different countries. The end-use and the tariff classification of the products are also the same. And it would be a very difficult case to prove that consumers treat differently, because of tastes and habits, products that are the same. Admittedly, it has been suggested that a recent case with consequences for products that cause harm provides the legal legitimacy to distinguish products, if not generally so at least on the basis of the impact of production methods.[9] In that case, the Appellate Body ruled that consumer perceptions are relevant when considering “likeness”, and it is easy to see the point that this is relevant to general tests of likeness. But the Appellate Body ruled on the basis of the use of chemical components with physical characteristics and hence established a link between the production process and physical properties of the end product. Therefore, this link is not likely to hold for a product exclusion as long as there is no evidence suggesting that the particular good discriminated against is physically different from the domestic good. A soda produced abroad is not physically different, at least not in a substantial way, from a soda produced in the home country.

One important case in this context concerns tobacco and US measures to treat clove cigarettes – imported from Indonesia – different from menthol cigarettes produced in the United States.[10] Other countries were also parties to this case because it also concerned them and, potentially, their exports to the US. While the complaint mostly (but not entirely) concerned the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, it is of interest as both the WTO Panel and the Appellate Body found the US measure (in effect, an import ban) to be discriminatory. Both instances agreed that clove cigarettes and menthol cigarettes are “like” products, and hence that a ban on clove cigarettes but not menthol cigarettes were a direct violation of national treatment. Again, the ‘likeness’ test was critical and it shows that products that are like have to get similar treatment if a regulation is to be compliant with international trade rules.

GATT Article III and Article XI. Paragraph 4 of GATT Article III says that “the products of the territory of any Member imported into the territory of any other Member shall be accorded treatment no less favourable than that accorded to like products of national origin in respect of all laws, regulations and requirements affecting their internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution or use.” The law, and the application of it, is straightforward and sets out the core principle of national treatment. Clearly, a product exclusion fails the test of consistency as it clearly will affect sales of foreign producers discriminated by a regulation that will withdraw a product from the trade agreement and confer an advantage to home-producers that is not conferred to like products from other WTO members. Consequently, the discriminatory aspect of likeness discussed under GATT Article I applies equally to GATT Article III.

WTO tribunals have over the years worked with several complaints in the field of alcoholic beverages that relate to Article III and that are of importance, not least in the context of excluding certain beverages from trade agreements. For instance, several countries have applied different tax rates on spirits that are produced nationally compared to spirits that are imported. In Chile-Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages both a WTO panel and the Appellate Body found that a law mandating higher taxes on imported spirits compared to local blends violated Article III because the tax differences were directly related to competitive and substitutable products – in essence, like products.[11]

Hence, it is clear that a product exclusion would run counter to some of the core GATT articles. There is, however, the theoretical possibility that measures that de jure or de facto would exclude products from market-access commitments in the WTO could be consistent with core GATT principles if it can be established that the measure qualifies to be treated under the General Exception clause – Article XX. As mentioned above, this article justifies exceptions if it can be established that an otherwise GATT-inconsistent regulation is necessary to – in this case – “protect human, animal or plant life and health”. There are similar bases for exemptions based on the exhaustion of natural resources and the environment more broadly. However, Article XX is not providing an open-ended excuse to adopt any sort of trade-restrictive measure and it takes a lot of evidence to prove that trade discrimination actually conforms to the objectives of product exclusions. The use of Article XX is not accepted just because a country declares that a measure that violate GATT articles are necessary in order to achieve a larger goal. If that was the case, the WTO system would have collapsed a long time ago because many countries would then claim exception under Article XX for all sorts of measures.

There are a few WTO cases that have provided guidance on the application of GATT Article XX and instances when core rules to protect the principles of national treatment and non-discrimination are subject of legal complaints. All of them do not deal specifically with public health, but they are nevertheless of importance. What they suggest is that many measures that claim the status of Article XX exception do not stand up to the so-called “chapeau” requirements of this article.

The chapeau (or preamble) of Article XX disciplines the potential misuse of the Article – the use of the Article for other purposes than those stated in the particular paragraphs. To that end, the Appellate Body has clarified in rulings, e.g. Brazil-Retreaded Tyres, that there must be a rational connection between the measure and the regulatory goal in order to avoid ‘arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination’. Panel reports have opined that the way to test this is to examine whether ‘the design, architecture and revealing structures’ indicate an intention to ‘conceal the pursuit of trade-restrictive objectives’.[12] This will be a difficult test for any measure that directly or indirectly concerns product exclusion. As long as a product is defined as legal and allowed for consumption and production domestically, a product exclusion is clearly a pursuit of a trade-restrictive objective.

In a more recent dispute, EC-Seal Products, the dispute-settlement bodies of the WTO also added more guidance on discriminatory measures and claims that those can be authorised under Article XX. The case concerned a ban in the EU of placing on the market seal products, and the general outcome of the dispute is that the ban remains.[13] However, the ban had to be changed because, initially, it had exempted some seal hunters and their products from this ban. Unsurprisingly, the Appellate Body found that, while seal products can be banned, discrimination between different producers were not compliant with the chapeau requirements. The exemption conferred advantages to some producers that were not accorded to others. Hence, a classic example of discrimination.

What these – and other – cases show is that a member of the WTO that seeks to ban imports of certain products (by excluding them from their obligations under trade agreements) would run foul of the most basic rules in the WTO and that such actions would not be authorized under GATT Article XX. WTO agreements are particularly attentive to measures that discriminate between producers, and that is only natural since one of the most established practices in trade politics is that governments want to give advantages to national producers at the expense of foreign producers. The principle error of excluding products from a trade agreement is that it would give direct and obvious advantages to local producers that are not affected by what would become a trade ban.

2.3 International Agreements on Product Exclusion

The previous section addressed the specific situation when one member of the WTO (or, more generally, a trade agreement) withdraws from current obligations in the trade agreement with the purpose of banning trade in a particular good, or a set of goods. It is obvious that such an action would be ruled against in a dispute-settlement proceeding in the WTO. Nor can a trade agreement between only two parties nullify the market-access commitments established in the WTO.

The situation is different, however, if all parties to the WTO agree to renegotiate existing agreements with the purpose of excluding certain products. If that would be the outcome of the new agreement – a voluntary change of the market-access obligations that countries previously have accepted – it would not run into legal problems. However, there are good reasons why such attempts and measures would fail and should be avoided.

A first reason is that it is not political feasible. In fact, it is a political pipe dream. To put it shortly, many countries would protest against the exclusion of certain goods from trade agreements. There is a great deal of variation between countries in how they view offensive and defensive trade interests. There is also variation in what political priority they attach to certain regulatory goals. While a measure to ban trade in alcoholic beverages may be seen as legitimate by some countries, it certainly is not a legitimate objective in the view of other countries. In practice, opening up existing WTO trade agreements with the intention of getting products excluded from them would effectively mean that a large part of WTO agreements would have to be renegotiated. It should be obvious to any informed observer that this simply is not plausible.

A second reason against starting a process of product exclusions is that a ban on trade in one product would imply a trade restriction on several other products. Take, for instance, the case for a ban on sugary drinks. A can of a sugary drink is a finished product, but it contains several products that are used in the production process and in the packaging – sugar and aluminum, to name just two – and trade in those products would be affected by the ban. The drink is made of lots of different ingredients and it is bottled or sold in a metal or a glass product that under current WTO concessions cannot be restricted. The list of different input goods that are used to produce the sugary drink can be made very long, but the main point is that the ban on trade in a finished product immediately would distort trade in the input goods market.

Let us now turn to Free Trade Agreements. Another course of action that has been raised in the discussion is that products that cause harm to public health and the environment should be excluded from FTAs and don’t get advantages like reduced tariff rates and access to more liberal rules of origin. Obviously, it is a less extreme approach than excluding products from the commitments in the WTO. However, it is a strategy that will cause a lot of damage to trade, but not reduce the harm to public health and the environment that is caused by the consumption of such products.

The first argument against excluding products from FTAs builds on the political-economy argument above. There are potentially many goods that can cause harm and, assuming that all sides to an agreement would follow their preferences of what products that are harmful, significant volumes of trade will have to be exempted. Even if the selection of good is narrower, there is still a tit-for-tat logic in trade negotiations.

If that approach is extensively used, it is obvious that it would not work since it could lead to exemptions for significant volumes of trade. There are many products that directly or indirectly can cause harm to public health and the environment.

The second argument is that the consequence of product exclusions in trade is first and foremost that domestic production of the harmful product will be protected and that there will not be disadvantages for other countries that are exporting the same product the countries that exempt products from an agreement. Product exclusions are not measures that take aim at the use and consumption of a product: the mechanism is rather one that distorts the condition for production and trade between different territories. This is particularly the case with Free Trade Agreements. A key economic feature of FTAs is that they reshuffle trade between different countries. FTAs provide better trade opportunities for the parties that sign the agreement and therefore they reshuffle a lot of existing trade. Consequently, exempting products from FTAs don’t mean that a country will import smaller volumes of these products: it rather means that current imports of that product from other countries will remain intact. Hence, there is no direct link between excluding products from an FTA and the total volume of imports of these products.

The third argument against product exclusions in FTAs is that – when practiced by many countries in many FTAs – they would create a “noodle bowl” of different conditions for rules and market access, leading to much more complexity and far less utilization of FTAs. Already now, FTAs are criticized for not creating so much new trade because of complex conditions for accessing the preferences offered in an FTA. Adding new layers of complexity for firms that want to trade would take down utilization rates even more, especially for SMEs that don’t have the experience of using bilateral trade agreements and lack resources to obtain trade expertise in their work to sell more products to consumers abroad.

[1] The next section discusses some of these disputes.

[2] OECD, Tax Burden on Tobacco.

[3] World Health Organization, 2012, Alcohol in the European Union: Consumption, Harm and Policy Approaches.

[4] REACH is an acronym for the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals.

[5] A market-access concession obtained in the WTO is legally valid even if a Free Trade Agreement between parties state something different. Consequently, an FTA or any other form of agreement does not nullify WTO concessions.

[6] GPR, US-Tuna (Mexico); GPR, US-Tuna (EEC)

[7] ABR, Japan-Alcoholic Beverages

[8] GATT (1970), Report by the Working Party on Border Tax Adjustments.

[9] ABR, EC-Asbestos

[10] PR and AB, US-Clove Cigarettes.

[11] AB, Chile-Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages.

[12] PR, EC-Asbestos; PR, US-Shrimp; PR, Brazil-Retreaded Tyres.

[13] Interestingly, seal products were not excluded from the EU’s schedule of commitments in the WTO, which underlines the point that countries actually can ban products without excluding them from their obligations in an international trade agreement.

Trade Substitution and Product Exclusions

The past chapter has demonstrated that, from the viewpoint of international trade rules, discrimination of like products are a central area of concern. Both the rules and the precedents set by past cases show that trade restrictions – like exempting categories of products from current WTO agreements – cannot stand up if they only affect goods produced abroad and not those produced at home. Therefore, for any government that would exclude products like chemicals, sugary drinks, candy, alcoholic beverages or tobacco products from trade agreements, the only way to do so and be respectful of international agreements would be to ban the placing of the market of these products (regardless of their origin).

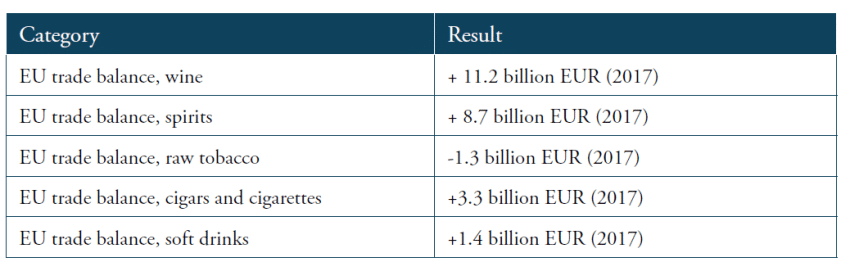

If countries would restrict or prevent trade in these type of goods, the first effect would be that imported goods would be substituted by local goods. The restriction would reshuffle production but not itself lead to less consumption of a good. Assuming that other countries would respond by not accepting imports from the country that introduced the trade ban, the reshuffling would in the first place be constituted by export volumes replacing import volumes for national consumption. If we assume that the EU would exclude certain products from its international trade obligations, the first effect would be that chemicals, wine, spirits, manufactured tobacco, and soft drinks would be entirely sourced domestically. The EU runs a positive trade balance in all those categories – hence, exports that now goes to non-EU countries would instead be placed on the EU market, provided that there is demand for them.

Table 3 outlines how the immediate effect could happen. The EU runs a substantial trade surplus in wine and spirits. If alcoholic beverages are excluded, the obvious first effect is that wine and spirits produced locally would substitute the volumes that previously were imported. Even if the trade balance is smaller in other product categories discussed here, there would be a similar effect in, for example, the market for soft drinks and finished cigarettes.

Table 3: Trade Balance and Import Substitution

Source: The European Commission

Source: The European Commission

Note: Chemicals are not included because trade in that category is varied and substantial

However, this is not the only effect. If imports are higher than exports, the effect would likely be that all or some of the import volumes would be replaced also by new local production. If there is an excess demand, there will be many producers that will adjust their business to serve that demand. The EU’s trade deficit in raw tobacco is a case in point. The EU now runs a trade deficit at 1.3 billion EUR, which represents a bit more than the total production of tobacco in the EU. In other words, to substitute current imports of raw tobacco, the EU would have – in rough terms – to double its own production.

While a doubling of production would take time, it is most likely what would happen. The EU has seen a big shift in its own production of raw tobacco over the past years, with growing production in some countries (e.g. Bulgaria) and declining production in other countries. The price effect has broadly guided this change, with farmers reducing their output because of competition. But if the EU totally stopped its import of raw tobacco, the price would go up in the EU and it would again be profitable for farmers to switch to tobacco. If those countries that have declined their production of raw tobacco would go back to area levels used for tobacco production ten years ago, that would cover up to 50 percent of the import volumes that would be lost because of a product exclusion. Agricultural areas are partly fungible and farmers react to changing price conditions by switching crops and output. The same, of course, holds for other crops that would be affected by product exclusion. The main effect would be a reshuffling of production patterns.

Conclusion

In this Policy Brief, we have argued strongly against excluding certain products from trade agreements – products whose consumption are harmful to public health (or the environment). The paper has shown that:

- International trade agreements are not in conflict with the ambition to increase regulation and taxes on certain products with the view of reducing their consumption. In fact, taxes and regulation have increased substantially on products that are usually referenced as worthy of exclusion from trade agreements. Consequently, creating a principled conflict between international trade agreements and public health creates neither more or better regulation of certain product, nor better trade policy.

- A unilateral withdrawal from obligations in existing trade agreements would run foul of core trade rules in the WTO. Banning trade in certain products would confer very strong advantages to national producers of those products, and other countries would file legal complaints against the entity that undertakes the unilateral action.

- A global renegotiation of international trade agreements with the view of excluding products from those agreements is totally unfeasible because countries do not have the same economic interests and do not necessarily share the same regulatory goal. Moreover, the exclusion of a finished product would severely restrict trade in the inputs goods used to produce the finished good.

- The main effect of a product exclusion would be a re-shuffling globally of production of the goods in question. A trade ban on products like alcohol or sugar beverages, tobacco, or certain chemicals would mainly have the effect of substituting production. Consumption of the good would hardly be affected. Nor would greater concentration of consumed goods to national producers be a stimulant for greater regulation; it would rather create powerful national-producers lobby with strong interests to reduce regulation or change their effect on consumption.

What these conclusion suggest is that trade policy is not a tool for regulatory ambitions. Trade policy concerns trade, and the instruments and agreements that exist for the pursuit of better and less-discriminatory trade conditions simply cannot be used for sundry regulatory proposes, however relevant they may be.