Assessing the Solar Energy Dispute between the European Union and the People’s Republic of China

Published By: Sylvain Plasschaert

Research Areas: Far-East Trade Defence

Summary

Sylvain Plasschaert is Honorary Professor at the University of Antwerp and at the Catholic University of Leuven

1. Introduction

China is a major trading partner of the European Union (EU), the destination of much Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) by EU firms – and by far the most targeted country of anti-dumping investigations by the EU (and other economies like the US). In the spring of 2012, the European Union and China got embroiled in a tense dispute about trade in the novel but rapidly growing solar energy field. The surge in EU imports of such goods from China – especially of solar panels used in the last stage in the production sequence of photovoltaic energy – prompted a group of EU-located producers of solar equipment to request trade defense measures from the European Commission. After conducting investigations the Commission imposed a provisional anti-dumping duty on such imports in June 2013 while threatening to impose significantly heavier levies on solar panel imports from China if no satisfactory arrangement could be found before 6 August 2013. Close to that deadline, an amicable ‘understanding’ was reached, whereby China agreed to reduce its overall quantity of exports to the EU and put a floor price on those exports. Thus, a major trade conflict about the largest contested trade volume ever was averted.

The paper assesses this recent antidumping case in the light of a changing world economy and the current anti-dumping framework of the European Union. Chapter 2 of the paper introduces the issue by presenting a factual narrative of the specific antidumping dispute about solar panels and recalling its antecedents, in which an almost worldwide hypertrophy of solar energy enthusiasm collapsed into a deep downturn in the solar energy sector.

As exports of certain products are targeted by anti-dumping duties, Chapter 3 of the paper first recalls China’s impressive export performance since around 1980, when China opened its economy to the wider world. It then positions the latter within the broader setting of three deeply impacting and intertwined changes in the world’s economy which provide a relevant background to the analysis. As a more exhaustive treatment of such complex topics would inflate the length of this paper, only the main essential features are sketched. These three metamorphoses that transformed the traditional channels of cross-border trade into highly complex sets of links between enterprises from different countries are: (a) the continual multinationalisation of a large number of enterprises (via foreign direct investment and contract manufacturing), (b) the increasing fragmentation of production in global value chains, in which multiple tasks are performed and various ‘slices’ of intermediate goods are manufactured and traded between different countries, and (c) the presently applicable convention in the statistical reporting of trade flows.

In order to provide an adequate understanding of the subject matter, Chapter 4 and 5, furthermore, provide a succinct look at two relevant strands of EU trade policies: The trade and investment relations between the EU and China (Chapter 4) and the methodologies used by the EU in its anti-dumping (AD) actions, particularly those pertaining to China (Chapter 5).

Against this background, Chapter 6 of this paper presents a critical analysis, in economic terms, of the solar energy case conducted by the EU (and by implication, of other similar anti-dumping cases). It thereby considers, on the one hand, various more general aspects of anti-dumping disputes such as the roles of governments versus those of firms, the conflict of interest between producers and importers, and the impact of anti-dumping duties on the competitiveness of domestic firms. On the other hand, specific aspects of the anti-dumping framework of the European Union are discussed, such as the ‘public interest’ test used in EU anti-dumping proceedings, the market economy treatment of foreign suppliers, the analysis of the economic impacts of anti-dumping duties on different stakeholders, as well as the political dynamics of the solicitation of trade defense measures. Based on these considerations, specific aspects of the dispute between China and the EU are considered, such as the controversial question about China’s market economy status and other arguments which have been invoked to discredit imports from China.

Chapter 7 provides some final considerations about the potential lapse of China’s market-economy status at the end of 2016. Chapter 8 concludes with some remarks on the future of the EU system of trade defense instruments, suggesting some paths to arrive at more satisfactory arrangements between the various stakeholders involved in anti-dumping disputes.

Before embarking on this ambitious agenda, however, it is necessary to clarify a few self-imposed limits on this paper, lest it becomes unwieldy. First, the paper looks essentially at anti-dumping measures proper, which are still the most frequently operated trade defense instruments (TDI) of the EU. Hence, countervailing’or anti-subsidy measures, which nowadays tend to be resorted to somewhat more frequently, are not included in the following analyses. Yet, the third conceivable instrument, a safeguard against import surges, will be mentioned, as it appears to have been introduced de facto as a, perhaps temporary, solution to the solar energy conflict. Second, the paper considers in essence only trade in manufactured goods, not trade in services. Third, the paper looks at the ’real’ world of international economics, as related to the border-crossing flows of goods and services, not at the even more globalized field of international financial transactions.

2. The Solar Energy Sector in the European Union and China

2.1. The Boom and Bust of the Solar Energy Sector

Renewable energies, tapped from nature itself, open a wide horizon for scientific progress that would bestow incommensurable economic benefits to the world as a whole. Indeed, as soon as developers of solar energy, no longer buttressed by government subsidies, would succeed in improving the technologies (for the generation, the storage, and the transmission of solar power) to the ‘grid parity’ level, the benefits would be truly revolutionary. The ‘grid parity’ level is the level at which the cost to install solar energy capacity would descend to that of electricity provided by fossil fuels (coal, petroleum or gas). Solar energy, for example, is inexhaustible, clean and – if it is efficiently captured – has low variable costs. Moreover, and vitally important, photovoltaic solar energy does not release carbon dioxide. Sunshine is also available all over the world, albeit in unequal doses. Hence, the operation of a solar energy system can be organized in a fairly decentralized manner. In due time, solar energy could be delivered in small quantities into individual households and such micro-units might become ‘prosumers’, who combine the roles of producers and consumers, in the terminology of Rifkin (2014), who anticipates their emergence in thirty years.

Looking back at around the turn of the century, solar energy came to exert a strong appeal in the business world within the span of a few years. In the US, especially in sunny California, a number of firms started to manufacture chips, cells and /or panels. In Europe a similar hype in solar energy took root in several countries, especially in Germany which had established a strong position with respect to silicon, a widely used material, and cell production. Elsewhere in Europe many firms in the energy sector, or even in plumbing, eagerly engaged in the solar sector, especially with respect to the installation of solar panels. The initially rather lavish subsidies to consumers by governments in a number of countries, propelled a booming business. Moreover, the installation of solar panels was viewed favorably by governments, on account of its labor-intensity. In Germany a law in 2000, aiming at developing renewable energies, provoked a real outburst of activities in solar energy. As a result, Germany had the world’s highest output of solar energy by mid-2011. Italy and Spain, more generously gratified with sunshine, reached about the same modest, but rapidly rising, coverage of electricity needs.

The interest in solar energy erupted quite suddenly in China also, but it occurred at a later stage. The interest arose once the Chinese government had announced that it would provide rather generous subsidies to the enterprises that would enter this new field, which were initially focused on wind energy. Furthermore, firms in China were typically heavily involved in the end phase of the production process, such as that of assembly into solar panels, and intermediary inputs, such as Germany-made silicon cells, were often imported.

In such a propitious setting, the solar industry experienced a meteoric growth over the last decade. A great number of firms initiated the production of solar panels, especially in China, or of components, such as silicon cells. In other regions, particularly in Europe and the US, more on the ‘consumer’ side, the installers of solar panels tended to purchase panels from the lower-cost producers, quite often located in China. The hype of the solar energy sector (and of its ‘cousin’, the wind sector) reminds us of the internet hype in the first years of the new century, but which soon capsized into a deep crisis.

The breakdown of the photovoltaic energy sector was as sudden and deep as its ascent had been speedy and promising. The causes of the downfall were largely similar in most of the countries already cited above. Some of the general reasons for the breakdown of the sector include:

- Over-optimism had attracted many firms to start production. Some of these firms were seasoned large firms, with a solid technological craft, but others were small firms with a weak financial backbone.

- Many firms, encouraged by government subsidies, did not hesitate to borrow heavily, especially since interest rates were notoriously low. In the prevailing bullish ambiance, they perceived a golden opportunity that should be availed of as soon as possible and on a large scale. Thereto a number of firms at once set up affiliates abroad, but their forward financial planning was often inadequate.

- The overinvestments entailed considerable overproduction, which, in itself, provoked a downward turn of the prices of their products and of their profit rates, in an already fiercely competitive market.

- Concurrently, some technological advances pulled down the production costs and heightened the rivalry.

- In sum, investing firms had inadequately factored in some characteristics of a seemingly attractive new business, but in a still immature industry, with rapidly evolving technologies. Therefore, there was the related risk that a price war may soon ensue and the likelihood that this new field would attract many new rather adventurous producers.

In addition, the development of the solar energy sector in China aggravated the situation. In China the response of the business world – typically rather by fairly small non-state companies, not large State-owned enterprises (Freeman, 2015) – to the prospects of benefiting from the government subsidies, was much more forthcoming than the government had anticipated. About 400 firms, of varying solidity, plunged into production. Outlets in China remained limited, as the electricity generated could not be loaded on the underdeveloped distribution grids. Yet, due to some economies of scale and partly to lower labor costs, and to some public subsidies, firms in China were able to supply panels at a cheaper price than their foreign rivals (serious estimates, such as at the Asian Development Bank put their price advantage at around 20 % (Xie, 2012)). Several of them, once they were in severe financial straits, emptied their stocks at discounted prices, and flooded the export market, where they found eager importers of panels in the EU and the US.

In the main countries involved, quite suddenly several of the factors just mentioned, coincided and provoked a widespread cataclysm, which caused the downfall of a significant number of firms, even among those that were in pole position. The very rapid surge of producers in China and of their exports provoked real disasters in the US and even more in the EU. Furthermore, the concomitant financial crisis that engulfed the world did not provide a favorable background to the solar industry, although the financial tsunami in itself cannot be held accountable for the catastrophe in the solar energy field, as the latter occurred not only in the Western world, but equally in China.

An example which illustrates the downfall of the sector in the United States is the American firm Solyndra, which was first acclaimed as a shining innovating firm. At the end of 2006, it requested a government guarantee for the construction of a new robotized manufacturing facility. In September 2009, the US government granted a subsidy amounting to 535 million USD. However, less than a year later Solyndra ran out of cash. The prices of its panels had dived deeply, while the company was launching a more efficient, but more expensive, technology. In August 2011 the firm was declared bankrupt and more than 1,100 employees were laid off. The strong competition by the Chinese firms Suntech and Yingly was mentioned as a contributing factor, but allegations of illegal accounting manoeuvers have also been leveled.

In Germany, a significant percentage of the firms involved went bankrupt, on account of the keen competition of Chinese imports, the overambitious expansion plans of some firms and the burden of the debts incurred. Amongst the victims were some well-known firms, such as Q Cells and Conergy.

In China, the destiny of many participants in the solar energy sector was similar. Suntech, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, which in 2011 proudly proclaimed that it was the world’s largest solar energy firm, was declared insolvent in 2013. Its creditors, notably the state-owned Development Bank of China and the Bank of China, did not renew their outstanding loans and bills to several suppliers of inputs – among them South Korean firms – remained unpaid. Suntech was finally salvaged, in a much slimmed format, by the city of Wuxi, where it is headquartered and employed 10.000 workers, and by a Hong Kong investor. Other Chinese firms, such as Trina and Yingly, which had already built up a solid position in foreign markets, also went through tough times, due largely to the drying up of consumer subsidies in importing countries, but they survived.

2.2. The Anti-Dumping Case between China and the European Union

The preceding exposé already presages the sharp anti-dumping conflict that occurred between the EU and China. This dispute soon became a hot topic in the media and unleashed accusations of varying veracity from interest groups, and even from official spokesmen. As already mentioned in the introduction to this paper, a last minute agreement settled the case, at least temporarily. A succinct narrative of this clash is provided herewith.

As in some other similar disputes, the solar energy anti-dumping (AD) measures were enacted first in the US, ahead of those in the EU. A complaint by producers in the US, led by the American subsidiary of the German firm Solar World, together with six other producers (which chose to remain anonymous), requested action against the imports from China, which had been growing rapidly. The US Department of Commerce enacted an AD duty, amounting to 31% (and an anti-subsidy levy of 73%, as well). Those levies were instantly challenged by a ‘coalition for the affordable solar energy’, which stressed that the cheaper imports from China benefited consumers in the US and that many more workers were employed in the installation of the imported solar panels than in the domestic manufacturing of solar products.

A similar complaint was lodged with the EU Commission by a Pro Sun coalition, equally spearheaded by Solar World, which grouped about 40 producers. The allegation was that manufacturers in China practiced dumped export prices and benefited from massive and unfair subsidies at various levels of governments in China. This move was immediately protested by the ‘Alliance for affordable solar energy’ (AFASE), an ad hoc coalition of about 400 importers, installers and large distributors, who advocated the free entry of solar panels into the EU. As in many other EU-China trade conflicts, the opposition of interests between producers versus importers, and users, was obvious and highly mediatized (an issue also discussed in Chapter 6).

While the Commission was investigating the complaints, and statements by EU decision-makers strengthened the expectation that tough trade defense measures were forthcoming, opposing opinions were voiced as well, even within the same country. Member states were openly divided on the issue. In Germany, for example, Chancellor Merkel, who was hosting the Chinese premier, counseled caution. The fear that China, a major outlet for EU business, might retaliate even in unconnected areas was conceivably a major consideration underpinning her position.

Despite strong political headwinds, the European Commission persisted in its AD investigation and stated that it found evidence of price dumping. This is plausible, as in a number of cases Chinese producers facing overproduction and with little scope for outlets within China itself may have directed their sales to the EU at lowered prices to empty their excessive stocks. In June 2013, the Commission introduced a preliminary, rather lenient, anti-dumping levy of 12%. It threatened to transform this into a definitive duty of 47% if, before 6 August 2013 no agreement would be forthcoming. However, a compromise (valid until the end of 2015) was reached at the end of July. In an official memo of 4 June 4 2013, the Commission held that “this (action) is not about protectionism, and not about a trade war, but about re-establishing fair market conditions”. It also added that “in the absence of measures, 25,000 jobs in the EU would be at risk … and the EU’s technological leadership would be lost” (European Commission, ‘Frequently asked questions’, 2013). Close to the expiry date, China undertook to request its exporters to raise their export prices to the level of the prices applied by Korean exporters in the solar panel spot market. In substance, this agreement embodied a (not so) “voluntary export restraint”. In the end, 90 firms in China, accounting for nearly 60% of the EU market, accepted that norm while the others were subjected to the higher definite anti-dumping levy (for more details see Naman, 2014).

This agreement has significantly relaxed the tensions and looks balanced. One may surmise that the Chinese government also had misgivings about the overproduction at home which had not been anticipated to its actual extent. This interpretation finds support in the steps that were subsequently taken in China to severely thin out the number of producers and to redirect them more to the domestic market.

There were some dissenting reactions to this outcome. The ProSun group decided to contest the Commission’s decision at the European Court of Justice. In September 2015, the ProSun coalition requested the re-opening of the anti-dumping levies. Furthermore, a few other subsequent developments related to the EU-China dispute are also worth mentioning. In May 2015, the Commission initiated an ‘anti-circumvention’ action, alleging that its anti–dumping duties were sidelined via Taiwan and Malaysia, and in June 2015 the Commission terminated the undertakings by three major enterprises in China, including Canadian Solar. Additionally, the Commission enacted an anti-dumping levy on glass used in the manufacturing process of solar panels. This file, of much lesser importance, stands apart from the solar panel case, which would have been the largest anti-dumping dispute ever, with 23 billion USD at stake.

3. Implications of a Changing World Economy for Chinas Export Performance

Anti-dumping actions impose import duties on specific goods which are indicted of being imported at dumped prices (see Chapter 5 for the specific EU-China anti-dumping nexus). For many years, China stood out as the country whose exports are the most targeted by anti-dumping duties (and for a few years also by anti-subsidy actions). Hence, it is advisable to put the overall course of China’s exports in a proper and wider perspective.

Therefore, the following chapter provides first a discussion of the role of foreign direct investment for the Chinese economy. Then it provides some comments (in highly abridged format) about three interrelated world-shaking developments, namely (a) the still ongoing process of multi-nationalization of a growing number of firms, (b) the more recent spread of global value chains (GVC’s), and (c) the spectacular growth performance of China since 1980, and more particularly of its export trade, although the gross trade statistics need several qualifications.

3.1. The Role of Foreign Direct Investments in the China Setting

The significant role of foreign multinational firms in the Chinese economy and in its exports is widely acknowledged. Hence their role requires only few, but nevertheless important, comments. A firm that establishes merchanting or, more impressively, productive facilities in a foreign jurisdiction earns the epithet of a ‘multinational enterprise’ (MNE). The latter are most often rather small, especially in their early stages, although the expression MNE naturally evokes an image of giant MNEs, which play a leading role in the world economy.[1] Even though the very word of ‘MNE’ often raises criticism, one must confess that they are courted by most governments as they are harbingers of jobs and of technological progress.

These firms must obviously assess whether to supply a promising market abroad by way of exports from a ‘home’ production platform or by implanting production in the ‘host’ country. Outward FDI may be motivated by the low cost of manufacturing of labor-intensive goods, such as textiles, shoes and toys. The Pearl River Delta has attracted a plethora of such direct investments, largely on account of their relocation from Hong Kong or Taiwan with the aim of subsequent re-exporting, either back to the home market or to a third-country destination. Yet, already in the early days of incoming FDI in China (in the 1980’s) the ‘market-seeking’ intention of capturing a slice of a promising market in China itself was the primary objective. The ‘market-seeking’ intention overshadowed the motivation to serve foreign countries out of one’s own new installations in China, as was typical for simple, labor-intensive goods.

3.2. Contract Manufacturers

So far, this text has brought to the fore the stylized categories of firms, which set up production with a similar product range in their own affiliates in ‘host countries’. Yet, the present-day international business scene is much more diversified, in its functional specializations, and in its complex nexuses.

The rapid expansion of outward FDI to take advantage of lower production costs inspired, not surprisingly, the emergence of ‘contract manufacturers’ in East Asia, which, against the payment of a modest fee, perform the task of manufacturing the merchandise according to instructions specified by principals such as Apple, Wal-Mart, Sony or Samsung – with the brand of those firms affixed on the goods in question. The large production volumes which such ‘contract manufacturers’ can produce, as well as their ability to provide flexible responses to the injunctions by the principals (including their insistence on speedy delivery), allow them to submit competitive offers. Provided they can enlist solid clients, they thus avoid the risk of unsuccessful marketing, as the sale of their output is already pre-ordained. Typically, however, their principals want to maintain control of the ‘head’ (more particularly of their brand) and ‘tail’ portions of the ‘global value chains’ (which are discussed in the next subchapter). One may notice that most operations in the ‘head’ and ‘tail’ sections of the overall value chains are typically categorized by economists as ‘services’, although they also bear on physical goods.

The outstanding example of these ‘contract manufacturers’ is Foxconn, a Taiwanese firm, which supplies electronic goods from its 14 factories in China and elsewhere to Apple and other ICT giants such as Intel, Toshiba or HP. That means that Foxconn supplies multiple customers – which, ironically, may compete intensely amongst each other. Foxconn employs more than one million workers in continental China. Contract manufacturers are not a rare phenomenon, with most of them headquartered in Asian countries, more particularly in Taiwan and Singapore, but shortly also in China. In the terminology of UNCTAD, such arrangements belong to the category of ‘non-equity modes of international production’. Such firms nowadays expand the reach of their activities to comprise design or distribution whereby they own the related intellectual property.

One should also underline that a large percentage of trade in goods and services, conducted by MNEs, occur between the parent company and its affiliates abroad. In an estimate of the global gross exports of goods and services in 2010, UNCTAD (2013) put the percentage of internal transactions at 33% of the total gross trade of MNEs, with total trade of MNEs accounting for about 80% of the world’s global trade flows. A major vector of those intra-firm flows consist of the final goods transferred to commercial affiliates abroad. Another vector, in vertically-integrated MNEs, consist of intermediate goods transmitted to other members of the group for further elaboration. Furthermore, there are also various internal financial flows (not all of them related to trade transactions) as MNEs tend to pool cash resources in jurisdictions that grant tax gratifications.

Thus, the emergence and the still ongoing spread of multi-nationality, now being joined by ambitious Chinese firms (which have joined the chorus of multinational firms and are positioning themselves in the EU, the US, or elsewhere), have already shaken the traditional outlook on international economic relations. It also follows that a government policy that would only seek, in mercantilist fashion, the maximization of export proceeds, is likely to misfire. One should add that about 60% of global trade is composed of trade in intermediate goods and services for final consumption (UNCTAD, 2013). Hence, there is a need to revamp the analysis of the more traditional canons of trade theory and policies. The exports achieved by a country’s domestic firms are often far from measuring accurately the success which that country achieves in a foreign territory. Therefore the sales of its affiliates in that host country should also be encompassed.

The next topic, which sketches another more recent development in international business, adds to the complexity. Thereafter, when reporting on China’s impressive entry in the international world in subchapter 3.5, the intimate interlinking of inward FDI with China’s export trade (and the largely related flows of imports) will be considered

3.3. The Fragmentation of Production Processes in Global Value Chains

The preceding overview rested on the inherent assumption that FDI remains conducted within the compass of the same MNE — excepting the last mentioned case of ‘contract manufacturers’, which involves subcontracting to another, unrelated actor. A real-life look at the international business scene today imposes to transcend that already fairly globalized, and complex picture, and to highlight the rapid expansion of Global Value Chains (GVCs), about which laudable efforts at their statistical registration are now coming on stream.

GVCs – this rapidly acclimatizing acronym is likely to provoke some confusion. In its genuine global dimension, economic value is produced (‘added’) along all the successive stages of design, fabrication, assembly, marketing and distribution of products or services, up to the final consumer, or another user firm for further elaboration. International dispersion or fragmentation of such economic processes is not at all novel. Consider not only a present-day car manufacturer, and a fortiori Boeing or Airbus, but a modest cotton shirt, whose basic material is grown in a subtropical climate. Admittedly, when looking at the complete production-cum-commercialization sequence, it becomes obvious that the production cost of a given traded product only represents a modest percentage of the overall value chain in internationally-traded goods. Various studies, already Linden and others (2007), estimated that for the (then) Apple iPod MP3 Player out of a retail price of USD 299, only USD 4 was paid to Foxconn for its assembly and testing in China. At the point of exporting from China, however, a wholesale price of USD 183 was declared (and assigned to China’s export statistics).

Yet, the expression GVC is nowadays mainly circulated in a stricter sense, as it focuses on the physical products and the services that compose a product which enters the international market after its assembly. Such products tend to contain many inputs that originate in firms located in other jurisdictions, often in the East Asian region. Quite often they are assembled or subjected to a final elaboration in China whence they are sold abroad. Those products frequently contain parts or components which are themselves originating from other countries. The facilities located in different jurisdictions may belong to the same (multinational) enterprise or are operated by virtue of ‘horizontal’ contractual arrangements between unconnected firms. The links into GVCs can be either forward ones (where a firm in a given country provides inputs to an enterprise in another country for exports from the latter), or backward ones (when the country in question imports inputs that are inserted in its own exports). The role of China for such value chain linkages in both directions has been substantial in recent years (for more details see Banga (2015)).

Thus, the essential feature of internationally-fragmented production is that the very physical final objects that are internationally traded are often composite ones. This means that they contain many intermediary inputs procured by firms from different countries which are able to prove their proficiency in offering a more up-to-date or a cheaper component. Yet, such components, or ‘tasks’, are also the object of fierce international competition. And, obviously, as such components involve cross-border trade, the market for intermediate goods has grown worldwide, but particularly in East Asia

3.4. Implications of GVCs for Trade Statistics and Policies

The present-day reality of GVCs and their frequent fragmentation, even if only viewing the manufacturing stage of the exported ‘hardware’ product, cannot be denied. This also is relevant to trade statistics. Traditional trade statistics concerning gross exports do not reflect which portion of the value added can be attributed to which components and to which firm in which country. Yet, a joint initiative of the OECD and the WTO allows a better understanding of such trade in ’values added’, as it has established a database by linking national ‘input-output’ or ‘inter-industry analysis’ with data from bilateral trade flows. This data shows that for China the foreign value added component in final demand stands at around 17%. At first glance, this may appear surprising, considering China’s apparently impressive export performance. But the reality is somewhat more nuanced, as will be explained in the next subchapter.

In this connection, it is also worth noticing that GVCs which involve several countries entail some double counting in the statistics about international trade. Consider a good physically exported from China at USD 100 which is attributed to China. If, however, the good contains a major component that was formerly imported from Japan at USD 40, the international trade statistics must also encompass the trade between Japan and China. Aggregate trade statistics then figure USD 140, with the Japanese input double-counted.

Overall, it must be reaffirmed that the excessive attention to the maximization of export earnings, in a traditional mercantilist style, is no longer valid, as it does no longer conform to the structure and dynamics of much of today’s globalizing economy. Indeed, if a product which is manufactured in e.g. China is inserted as an intermediate input in a further elaboration process, import duties or anti-dumping levies on such goods would hurt those local processing firms and the latter’s’ competitive export position

3.5. The Impressive Growth of China’s Export Earnings Call for Qualifications

The phenomenal growth pace of China’s GDP since 1980 and the resulting unprecedented improvement in the living standards of hundreds of millions of its citizens is undoubtedly one of the defining events of the last half century.

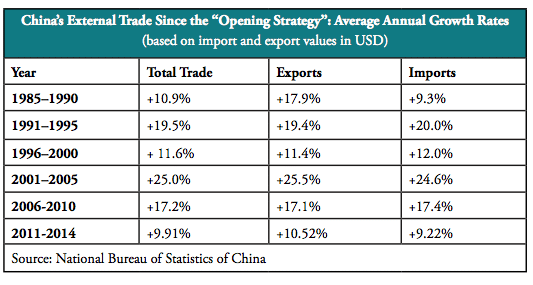

There is agreement among China observers that this truly impressive surge of exports proceeds since 1980 – when the then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping professed the mantra of ‘reform and opening to the outside world’. This has provided a major plank to China’s economic growth. In most years, the rise of receipts from export trade has exceeded that of its GDP, i.e. that of its overall economy. In the process, China has negated the general expectation that large countries tend to be less open than small countries – as measured by the percentage of exports and/or imports to GDP. Thus, China is nowadays much more open than India, Brazil, Russia and the US.

The ‘opening up’ of China was no doubt inspired by the successful rise of exports of Japan and of the ‘little tigers’ in East Asia, particularly of South Korea and Taiwan, where the previous import substitution strategy has been drastically revamped into an export-led strategy in the 1960s.[2] This redirection resulted in a steady growth of their export trade, initially focused on labor-intensive goods.

In 2001, the People’s Republic of China became a member of the WTO, sixteen years after it had applied and at the cost of extra concessions by the Chinese side, which included being treated as a non-market-economy for 15 years. China’s membership of the WTO has significantly accelerated its insertion in the international economy. In the meantime, China had substantially lowered its previously high import duties, which until then played more a fiscal than a protective role, because all handles of international trade policy were directly controlled by the State. Today China’s import duties are significantly lower than those of India, Brazil and Russia. The accession to the WTO, which was eagerly pursued by the Chinese leadership, has naturally imparted a strong impetus to the flow of exports from China (and to the direct investments by foreign firms). There is no need and no space to recount this sequence here in detail, but the following statistical indicators about China’s trade performance in the two directions of international trade in goods and in the resulting balances show China’s impressive performance.

A few more general points about Chinas export performance are also worth stressing (in Chapter 4 the China-EU relationship is discussed in more detail). In 1985 the overall value of exports from China was already rising perceptibly, largely due to three related factors:

- The first factor stems from the opening of four ‘special economic zones’, particularly that of Shenzhen, just across the border with Hong Kong, which accorded tax and other advantages to inward FDI. Many other areas in China soon followed, including the eastern side of the Pu river which crosses Shanghai, and where from 1995 high-tech firms came to constitute a first-class cluster.

- The second factor was the readiness of firms from Hong Kong and soon also from Taiwan (which has succeeded in mastering an enviable position in high-tech areas) and from enterprising businessmen in the Chinese ‘overseas diaspora’ in South East Asian countries to take advantage of the availability of an ample and cheap labor force on the mainland, whence they could successfully export labor-intensive products. Thus, in the 1990’s the toy industry was largely moved from Hong Kong across the border to Shenzhen, which was once a poor fishermen’s village (see Enright, Scott and Chang, 2005) and which is nowadays a full-grown metropolis that is often hailed as the ‘world’s capital of electronics’.

- A third factor that has favored the flourishing of exports stems from the fairly flexible attitude of the Chinese leadership, although (as confessed by their erstwhile top managers (see the memoirs of Zhao Ziyang, 2009)) the route which China would follow was not at all clear. Yet, the Chinese leadership has been much more open to inward foreign direct investments than Japan and South Korea which have remained reluctant to accommodate such inflows. Thus, the initial restriction of inward FDI to joint ventures with Chinese counterparts was abandoned in 1986. The foreign affiliates of foreign firms were gratified with a more favorable rate in the corporation tax than the domestic firms until 2008, a fairly unique case in the area of international taxation.

Over the years, the (gross) value of China’s exports of goods has been boosted not only by the rise of the quantities exported, but also by a gradual shift in the composition of China’s export portfolio. Higher valued goods, amongst them electrical appliances and ICT products, have been substituted for labor-intensive goods, or complemented the latter. UNCTAD (2014) recently stated on its homepage that “China stands out in many ways in the ICT landscape… In 2012, ICT goods made up as much as 27 per cent of China’s total merchandise exports…and China remained the world’s top exporter of all main categories of ICT goods”.

Yet, the gross nominal export data are not a fully reliable metric of the value added by exports to the welfare of a country, say its GDP per capita.[3] They must be qualified by three major features of China’s international trade patterns.

- First, a large portion of exports (estimated at about half of total exports) from China does not originate from firms that are registered and are located in mainland China. In other words, the ‘made in China’ label does not equate with ‘made by China’. One may thereby not overlook that (the many) firms from Hong Kong, which constitutes a separate customs area, are treated formally as ‘foreign’ in Chinese eyes and statistics. There also has been a remarkable involvement of Taiwanese firms, despite the often tense political relationship between Taiwan and the People’s Republic and the necessity to organize such operations over Hong Kong until quite recently. An official Taiwanese source mentions that 80,000 of the firms operating on the Chinese continent are of Taiwanese origin.

- The second factor which qualifies China’s export data is that of China’s intensive involvement in global value chains, as has already been mentioned in the previous section. China’s role as the giant participant on the East Asian economic scene is a major one, because the final elaboration often occurs within its territory.[4]

- Another relevant qualification of the prima facie overwhelming figure of the gross value of China’s exports stems from the international convention to attribute the value of a good, which undergoes successive elaborations before it is effectively exported, to the country where the last-stage processing is conducted. As mentioned previously, some final, labor-intensive arrangements towards an export product, more particularly their assembly, are typically carried out in China. Thus, Taiwanese products are often finalized in the PRC. To the extent such ‘final touch’ to an exportable product is managed on the Chinese continent, it would be misleading to infer from the gross value of the product that is effectively exported from China that such exports fully represent value adding activities in China itself. This caveat is particularly relevant in the present business world with its wide spread of global value chains, in which the Eastern shores of China have become important hubs.

[1] Recent research at Bruegel on European firms document that large enterprises score better than Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) on the criteria of economic performance, such as profitability, innovation and wage levels (Veugelers (2013)).

[2] It is worth mentioning that this turnaround in economic strategy in Taiwan and (South) Korea has been buttressed by innovative economic analyses by an impressive group of economists, such as Gustav Ranis, Anne Krueger, Jagdish Bhagwati and Bela Balassa.

[3] In strict logic, imports are the primary vectors of of welfare of a country as they satisfy needs. Export proceeds allow securing imports.

[4] As noticed recently (Constantinescu a.O. (2015), the relative role of foreign inputs into China’s exports may now be declining, as already suggested by statistical data. ‘Processed trade’ appears to shrink somewhat, whereas ‘ordinary trade’ expands. The authors hint that this sequence may point to some impact from the new strategy which wants to replace imports by domestic production.

4. The Economic Relations Between the EU and China

4.1. The Relations in General

In 1985, the signing of an ‘Agreement on trade and economic cooperation’ sealed the renewal of commercial and direct investment deals between the PR China and the EU (then numbering 11 member states). Subsequently, the economic relations and the political dialogues between the two partners have significantly broadened and deepened. High-level dialogues, including annual summit meetings (since 1993), are periodically held. More specialized contacts have been institutionalized in not less than 60 sectorial dialogues, which sometimes result in agreements and cooperative projects.

Recently, the two sides started negotiations on a bilateral direct investment agreement (BIA). Such an ambitious BIA would substantially solidify the overall relationship. It would substitute the slightly differentiated agreements which apply today between China and 27 individual EU member states with one single format. Yet, today the EU-members already extend a quite liberal welcome to incoming FDI, whereas in China access for foreign companies remains subject to authorization and may be disallowed, especially in the services area, which is still substantially restricted. However, recent shifts in China’s development strategy herald relaxations of the barriers to entry for foreign firms. In due time, a BIA agreement may pave the way for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) – which appears to be favored more from the Chinese side.

All in all, the relationship remains positive and reflects the benefits which each side expects from a closer interchange. In contrast to the US, there are no geopolitical frictions between the EU and China. The EU is a large market for Chinese exports and also a source of valued technology, appropriated either by way of licensing or through inward FDI. Conversely, European firms are attracted by the vast potential of outlets for their output and, until recently, by the scope for sourcing labor-intensive goods production.

Yet, the bilateral relationship between the EU – which, as an entity, is vested with responsibility for trade relations and now also for direct investments – is occasionally marred by incidents and misunderstandings. On some topics, as in the dialogue on human rights, on which the EU insists, progress remains meagre. Moreover, in various strata of the EU population the awe for China’s rapid surge is mingled with fears that Chinese firms will outperform European ones. This is reflected in an image of China, which, for good and less sound reasons, is far from uniformly positive (Shambaugh, 2013).

The EU is bent upon obtaining easier access for its firms to some Chinese sectors, especially as regards services, such as telecommunications, construction and banking. The EU resents the frequent interventions of Chinese governmental entities, at various levels, in the operations of European firms in China, which induce the latter into perceiving China as a non-level-field player. The prohibition of access to public procurement, a WTO undertaking which China has so far not signed, and the still occurring infringements of intellectual property rights (evidenced by the high proportion of fake goods from China seized at European borders) also draw criticisms.

The Chinese side formulates several complaints about its relations with the EU. The preservation by the EU (equally by the US and Japan) of China’s status as a non-market economy (at least until December 2016) and the resulting facilitation of anti-dumping procedures ranks high in the Chinese list of misgivings. This issue is discussed in more depth in subchapter 7 of this paper. The refusal of the EU to export arms to China is also resented. The Chinese leadership is also often dismayed by the complex and incoherent lines of command in the EU-28 institutional setting — although in populous China a rather autocratic government in Beijing may also face obstacles when enforcing its instructions at sub-central levels.

4.2. Bilateral Trade Between the EU and China

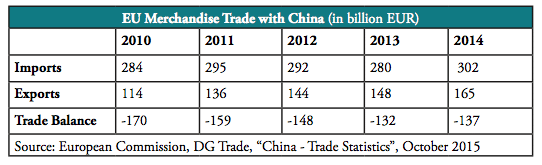

Bilateral trade between China and the EU has grown in a fairly steady fashion. In 1978 China and the EU had a bilateral trade volume of only 4 billion, whereas in 2014 EU-28 imports from China reached EUR 302 billion and exports to China EUR 165 billion.

A look at subcategories of trade in manufacturing reveals that China’s exports exceed by far those of the EU with respect to electronic data processing and office equipment, telecom equipment and (although less unequally) integrated circuits. This illustrates that China’s export portfolio has decisively diversified into higher-tech products. However, as explained in Chapter 3, the gross trade data hide China’s prominent role in the final assembly stage which incorporates a high percentage of imported inputs of parts and components.

The bilateral trade between China and the EU in goods has consistently exhibited a wide imbalance in favor of the Chinese side. This trade deficit tends, at times, to raise criticisms in some European circles, although less than in the US Congress.[1] China now represents the top origin of merchandise imports to the EU. The PRC is also the EU’s second largest export market. In terms of services, the exports by European firms, although still low and hampered by rather stringent restrictions to access to the Chinese market, are larger than those of China to the EU.[2]

Although trade between the EU and China reaches now more than 1 billion EUR every day and may be expected to further develop, the trade relationships between the two partners remain modest when evaluated against worldwide trade. Admittedly, the EU-28 represents the largest import outlet for China-produced goods, but, again, one should not overlook the high coefficient of imported inputs in the registered value of exports from China. Still, EU imports of goods from China represented not more than 18% of the EU-28 total in 2014. And the EU exports to China amounted to only 10% of the total EU-28 exports, slightly more than to Switzerland. The value of exports to the US was almost double of that to China.

4.3. Direct Investment Flows Between the EU and China

The close interaction of international trade with inward FDI was already underlined (see Chapter 3). Especially after 1992, China became a magnet in attracting foreign firms. The latter were attracted by the low labor costs in the export-geared manufacturing, but even more by the potentially huge outlets in China’s domestic market. China is now recorded as the largest recipient of inward FDI. The share of EU-originating FDI into China, while having grown substantially in absolute figures, and nowadays involving almost all major European multinational companies, remains nonetheless rather modest in relative magnitudes. In 2014, it amounted to 16 billion USD, which corresponds to a fairly stable 22% of inward FDI flows into China.[3] However, statistics about FDI in and from China must be approached with care. The statistics collected by the Chinese authorities are affected by methodological discrepancies and by the somewhat nebulous data of FDI by and through Hong Kong.

While minimal until 2010, the outflows of Chinese FDI funds are now growing impressively and are expected to exceed soon inward FDI flows. Within the EU, Germany and the UK appear to be favorite destinations, respectively in engineering sectors and real estate. Some Chinese firms, such as Huawei (telecommunications), Haier (appliances such as refrigerators), and Lenovo (which has taken over IBM’s segment of personal computers) have already carved out an enviable position in international markets. More outward FDI from China can be anticipated as the Chinese authorities now encourage outward FDI as a vector of China’s ‘go global’ strategy. The huge foreign exchange reserves of China allow their firms to have their outward initiatives underpinned by ample financing facilities at home. As regards the EU, Chinese firms are eager to secure patents and brands, so as to enhance their commercial appeal. Acquisitions are the preferred route instead of ‘greenfield’ direct investments. According to recent data, the US remains the most important destination of outgoing FDI from China. Hong Kong is recorded as an important destination of Chinese FDI, although it often acts as a stop-over. Although officially Chinese FDI appears to enjoy a growing welcome, and is nowadays solicited by a growing number of European or other governments the intended take-over of major domestic firms has sometimes been impeded by authorities in the host country. Besides, outward FDI moves are not assured of success, as they must be navigated in a culturally alien environment.

[1] A myopic look at a bilateral balance is obviously mistaken as the competitive stance of an economy must be inferred from its worldwide trade

[2] It is noteworthy that in recent years the Renminbi, the Chinese currency, has enjoyed growing use in trade transactions into or from China. A deeper analysis of this new phenomenon cannot be attempted here the more that new moves are being prepared that will enlarge the role of the Renminbi. A fairly recent analysis of the internationalization of the Chinese currency is given in Plasschaert, 2013.

[3] In most recent years, the proportion of FDI into the service sectors and the interior provinces is rising.

5. The Anti-Dumping Policy Framework of the EU vis-à-vis China

The narrative in Chapter 1 has already offered some pointers to the methodologies and the underlying philosophy of the trade defense instruments of the EU. The latter should, nonetheless, be elucidated in their main relevant tenets, so as to allow a proper assessment of the efficiency and the wisdom of the anti-dumping battery of the EU vis-à-vis China.

5.1. The Concept of Dumping

Dumping occurs, according to the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement (1994), in its Article 2.1 “when [a product] is introduced into the commerce of another country at less than its normal value”. The latter is defined as “a price lower than the one prevailing in the exporting market or lower than the cost of production, augmented with a reasonable profit margin”. The application of this seemingly logical definition represents an exception to the general rule which forbids discriminatory treatment of imports, i.e. the favoring of domestic producers over their foreign competitors. Yet, unsurprisingly, considering the bewildering heterogeneity of the goods and services that are internationally traded, the application of anti-dumping rules by a growing number of countries is highly complex and entails frequent controversies that lead to litigation at the courts and at the WTO conflict-solving entities.

The investigations and the possible subsequent sanctioning of dumping are conditional upon the proof adduced by the complainant companies in the importing countries that the indicted imports cause ‘material damage’ to their domestic industry. As compared to the traditional import duties, anti-dumping actions relate usually to particular and minor segments of a more general category of traded goods. Besides, the trade-defense instrument is directed against the imports from one or a few explicitly named exporting countries and firms, whereas import duties have more general applicability.

Apart from anti-dumping measures proper, the WTO rules allow two other trade defense instruments. First, the ‘countervailing’ or anti-subsidy measures aimed at correcting the impact of subsidies which are granted by the government of the exporting country in various ways (e.g. favorable conditions attached to loans, or the condoning of government loans, etc.) and which cause ‘material‘ damage to the relevant business sector in the importing country. The anti-subsidy weapon has now been unearthed more often in recent years, both in the US and in the EU. It should be noticed that, by their very nature, anti-subsidy actions directly challenge the trade policies of the government of the exporting country, whereas anti-dumping measures relate primarily to the behavior of individual firms, or specific sectors, in the trade-partnered country.

The other third trade defense remedy consists of temporary import duties that counteract imports “in such increased quantities and under such conditions as to cause or threaten serious injury to domestic producers” (Art. 2 of the WTO Agreement on Safeguards). While much less commented upon in the specialized literature than anti-dumping measures, this measure is quite often invoked in a rather roundabout way. As a matter of fact, the rapid rise of the imports of specific subspecies of goods acts as an eye-opener to the afflicted business sections in the importing jurisdiction, thus inducing them to request import-reducing actions from their authorities.

5.2. The Proliferation of Anti-Dumping Measures

Tariffs, i.e. the imposition of a payment at customs on imports from abroad, have traditionally been resorted to by governments as the main instrument for protecting domestic producers against imports. Such levies succeed in drastically curbing the flow of imports, if the domestic demand for the good in question is price-elastic. Quotas, i.e. the interdiction of imports beyond a specified value or quantity, would act even as a more potent instrument of retrenchment from international trade. In this connection, one should notice that the import tariffs, by and large, have traditionally been and still are ‘escalated’, whereby lower rates are applicable on intermediate products than on final goods. Such escalated system clearly serves the purpose of favoring the growth of domestic industry. This quite prevalent practice of import levies has entailed the sophisticated calculation of so-called ‘effective protection’ rates, which assesses the protection accorded to domestic value added. Such effective protection can reach very high levels when an economic activity involves modest domestic value added, as for example in the final assembly of durable consumer goods.[1]

The relevant point in this essay is that in recent decades the importance of import duties has been declining significantly in many countries, especially in the richer industrialized ones, thanks to successive rounds of multilateral tariff negotiations. This reduction took place first in the GATT and after 1995 in the World Trade Organization (WTO), but also on account of unilateral tariff dismantlement in a number of countries, among which China is noteworthy. Tariffs are still markedly higher in emerging economies, but the gaps between advanced and emerging economies have narrowed over time.

Once the worldwide financial crisis took hold, although the international economy has remained more open than could be feared, in several countries protectionist measures have been enacted. They were imposed sometimes as import duties or even as outright import quotas, but were often clothed in subtler forms, amongst them anti-dumping levies. The latter are catalogued as non-tariff barriers (NTB) —although one might argue that they are akin to tariff barriers, as they result in often prohibitive import levies on the (admittedly limited) categories of imports targeted by such ‘trade defense measures’.

When China acceded to the WTO in December 2001, its import duties had already been drastically slashed, and were, upon accession, further reduced to an average of 8.9% for industrial products. The entry of China into the WTO has been a lengthy undertaking, having been requested already in 1986. It was conditioned on the acceptance by China of restrictions that were tougher than those requested from other candidate-members, and about which the US acted as a pacemaker (Lardy, 2003). Thus, a ‘China-specific safeguard’ against imports from China could be imposed on products imported from China during a span of 12 years, whenever (only) ‘market disruption’ was threatened, whereas the corresponding WTO provision requires a ‘serious injury’ to domestic industry. Besides, for anti-dumping purposes, until 2016 China would remain treated as a non-market economy, which usually results in a readier conviction of dumping behavior – as elucidated below.

The recent decades have witnessed the rapid spread of anti-dumping (and anti-subsidy) investigations and of their subsequent levies on imports which are meant to correct infringements of fair trade norms and practices, as framed and supervised by the WTO. Throughout the 1980s and the early 1990s, the US and the EU were the heaviest users of anti-dumping actions. Japan was a foremost target of anti-dumping and some other overt protectionist measures (Davis, 2009). Since then, however, other users entered the field and emerging and developing economies now form the majority of users. A recent tally (Blonigen and Prusa, 2015), notices that between 1995 and 2014, the EU was the world’s largest user of anti-dumping measures (297 cases) behind India (519) and the US (323). Over the 2007-12 period, India and Brazil resorted more frequently to the anti-dumping weapon than the US or the EU (BKP Report, 2012), although they use higher import duties and stronger other protectionist instruments than is the case in China.

5.3. Evolution and Elements of the EU Anti-Dumping Framework

The first EU-wide legislation in the anti-dumping area was enacted in 1968 (Snyder, 2010). Two basic texts[2], dated March 1996 and October 1997, undergird the EU anti-dumping battery. The Commission is under the obligation to initiate proceedings when 25% or more of the producers of a (sub-)species of a product lodge indictments about dumping practices by firms in foreign countries. Thereto the complaints must provide evidence of the dumping event, of ‘material’ injury to the (Union) industry and of a causal link between the dumping practice and the injury.

This basic set of rules has not been much altered. In 2006, a Green Paper, submitted by the then Commissioner Mandelson, contained a proposal to enlarge the definition of the ‘Union producer’ (and hence entitling to request protection) by encompassing companies which outsource production outside the EU but retain significant operations within the EU (such as product design at the head of the value chain and distribution at the tail end). This would acknowledge the phenomenon of internationally fragmented ‘global value chains’. The Mandelson initiative failed to materialize.

In 2010, Commissioner for Trade Karel De Gucht launched an initiative to modernize the Trade Defense Instruments (TDI) arsenal of the EU. Previously, an external consultant, the BKP Development Research and Consulting GmbH of Munich, analyzed the current practices of TDI’s in ‘peer’ countries – namely the US, Canada, Australia, India, China, New Zealand and South Africa – and carried out an economic analysis of the TDI. This study, published in March 2012, while basically supporting the present course of action of the Commission, contained nonetheless a number of reservations on actual practices, and even a more fundamental questioning about the deeper rationale of the TDI (which is discussed in Chapter 6).

The steps towards a ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the modernization of trade defense instruments’, in a co-decision framework, comprised a wide range of consultations of stakeholders, and a workshop and public hearing in the European Parliament in November 2013. At the workshop there was fairly wide consensus on various steps that would render the procedures more transparent. There was also support for more openness about the criteria to assess the ’Union Interest’ test. The divergence in views – in fact in interests and in more basic ‘philosophies’ vis-à-vis international trade – between the representative EU-wide organizations of producers and those of importers in the EU clearly surfaced again at the workshop.

The initial intention to arrive at an amended set of trade defense instruments on the propositions by the Commission and to be adopted not only by the Council but also by the Parliament has run into serious opposition and into a split amongst the member states in the Council. Half of the member states are reported to have rejected the new proposals (Borderlex, June 2014).

The disagreements centered mainly on the proposal of the Commission whereby the ‘lesser duty’ rule would be abandoned in a rather extensively drawn number of circumstances. The’ lesser duty’ rule, a long-standing principle adhered to by the EU, holds that the EU levy aims at rectifying the injury, not at penalizing the exporting enterprise and country. Hence, if the injury margin remains below the dumping margin, the former standard should prevail. All in all, the original proposal of the Commission would have hardened the stance of the EU against foreign exporting countries. The De Gucht proposal has also been shelved and, for the time being, no change to the EU rules is being contemplated.

Looking at the specific features of the EU anti-dumping arsenal, it can be stated that the EU body of TDI shares many commonalities with that of other countries, as they are all basically embedded in WTO prescriptions. Actions by the US appear to have been inspiring analogous positions of the EU. Yet, there are also some notable differences between the sets of rules in the EU and in the US.

5.4. EU Anti-Dumping Measures against China and the Question of Market Economy Status

In the 2005-10 period covered by the BKP (2012), the EU initiated 68 anti-dumping (and 10 anti-subsidy) investigations. 80 new measures were imposed. 79 expiry reviews led to the extension of measures in 54 cases. Sectorwise, the chemical and metal products were the most targeted. During the same period, anti-dumping actions were aimed predominantly against developing countries, with China representing for over one third of all actions.

In recent years China has become the main target for trade defense measures by the EU, but also by the US. This comes not as a surprise, if one considers the following facts, which have already been alluded to in this essay:

- The startling growth of China’s export trade, especially when looking (myopically) at the gross export statistics.

- The bilateral trade, and the current account balance of the EU (and of the US), which have been consistently in deficit vis-à-vis China.

- The perception, somewhat lingering on, that the Chinese economy is still a tightly controlled economy applying the Soviet model of a centrally-managed economy.

- The absence of recognition that China, prodded by the desire to join the WTO, had substantially slashed its maximum (‘bounded’) and average tariffs. This turnaround was contrasting with the aversion of most developing countries to liberalize their trade (Messerlin and Wang, 2008). Nor was there adequate attention to the more stringent conditions for membership that had been imposed on China, which were mentioned earlier in this paper.

- In such an intellectual climate, the fears of being outcompeted by the imports from China exacerbated the requests for protective measures and the accusation, rightly or wrongly, that exporters in China practiced dumping was more readily raised.

Another important factor, which plays a role when looking at anti-dumping measures applied to imports from China, is the question of the market-status of the Chinese economy, as a whole and (in more restricted circumstances) of individual exporting firms in China. Since their early days, the GATT and the WTO provided for the ‘non-market economy’ (NME) status. In such a setting, when investigating a suspected dumping behavior, the actual price of the exported product is not compared with that of a like good in the same exporting country, but with that of an ‘analogous’ market-economy country, at a similar level of development. At its inception, the NME status was justifiably targeted at Soviet-type economic systems (including Mao-China ), whose fundamental tenets and their ways of operating, even at the micro-level of individual (state) enterprises, were imposed by the State and its Planning Organization, indeed. A consequence of the NME status is that, whenever the price of the contentious import product is shaped by lower labor costs, dumping can more easily be proven and, accordingly, anti-dumping levies tend to hit more severely.

The WTO documents do not specify which parameters characterize a NME status, nor the one’s that govern the choice of an analogue comparator. The EU applies a list of countries which are considered as running a non-market economy, amongst them China and Vietnam. It is noteworthy that Russia, which acceded to the WTO in 2012, had been granted market economy status by the EU in 2002.

In its protocol of accession to the WTO, China accepted vis-à-vis the EU (in the footsteps of the US) that Market Economy Status (MES) would be granted 15 years after accession, i.e. in 2016 (apparently automatically, as also stated in the BKP Report). Amongst the countries that still apply the Non-Market Economy Status one lists major developed countries, namely the US, the EU, Japan and Canada, but there is rather wide disparity among their procedures. Hence, in the wording of the BKP, those countries enjoy ample policy space.

To be recognized as a MES, the EU posits that the country in question must satisfy five criteria, namely (i) a low level of government interference with the allocation of resources and decisions by the exporting firms, (ii) no distortions that stem, when privatizing, from their previous centrally planned economy, (iii) a transparent and non-discriminatory company law, (iv) a coherent set of laws on property laws and bankruptcy and (v) exchange rate conversions carried out at market rates.

Requests by China to be accorded MES in 2004 and 2008 were rejected by the EU, which contended that its assessment was a technical exercise for the sole purpose of the trade defense investigations which do not involve a judgment about the general functioning of the Chinese economy – a rather specious turn of logic. Upon a question from the audience at the November 2013 hearing at the European Parliament, the representative of the Trade Commissioner replied that the Commission does not envisage any change in its treatment of the status of China before 2016.

Yet, as from 2001, when China was henceforth viewed as an economy in transition, individual firms in, say China, can request Market Economy Treatment (MET), which is then, in principle, valid for the sector in question. Thereto they must produce the proof that their exports are occurring under market conditions; this would allow them to be subject to lower anti-dumping duties. The five prerequisites to enjoy MET are analogous to those prescribed for the recognition of the country as a MES.

Exporters from countries which belong to the category of non-market economies can also request (most often done concurrently with that for MET) “individual treatment” and be exempted from anti-dumping levy. Private ownership of the shares is here a fundamental condition. This route may be useful for Chinese affiliates of foreign companies, provided that they can freely transfer their profits to their parent.

How these criteria were actually applied will be further commented upon in Chapter 6. As to the procedures, the EU Regulation adds that previous to deciding on the adequacy of the claim by the defendant firm in China, the EU Commission consults its Advisory Committee and gives the opportunity to the (Union’s ) industry to comment on the enquiry by the Commission.

China has introduced anti-dumping regulations in 1997, ahead of its accession to the WTO. While for most of the period since then China has been cast in the role of a defendant against the large number of procedures targeted at its exports, in most recent years China acts more offensively and initiates itself more actions, some of which have a retaliatory aim, such as a challenge raised against the importation of French wines.

[1] About half a century ago, various authors, particularly Balassa (1971), who have advocated the shift in development strategies towards an export-oriented one, stressed the ‘effective protection’ dimension of trade policies.

[2] Council Regulation (EC) n. 184/96 of 22/12/1995 on protection against dumped imports from countries not members of the EDC and Council Regulation (EC) n. 2026/97 of 6/10/1997 on protection against subsidized imports from countries not members of the EC

6. A Critical Assessment of the Anti-Dumping Case on Solar Panels

After assessing some of the background concepts relevant to this complex and potentially explosive conflict between the EU and China, a number of conclusions can be drawn, not only about some often overlooked dimensions of that conflict, but also as regards recommendable policies by the authorities involved. These considerations extend somewhat beyond the particular features of the anti-dumping case at issue and address more general aspects of anti-dumping disputes and specific aspects of the anti-dumping framework of the European Union.

There is no need to rehearse the plea that the implantation of solar and other vectors of renewable energy for the generation of electricity by power stations, but beyond the latter ultimately also for heating purposes by households and for transport modes, is highly advisable, not only for the EU and China but for the whole of mankind. This offhand instills the obvious conclusion that efforts should be joined across borders to pursue such objectives. This calls for forceful endeavors by enterprises and for substantial cooperation between them (and their governments), which includes, in a first stage, accelerated efforts to overcome the technological and logistical problems still underway. This would greatly contribute to winning the vital battle against pollution and detrimental climate change.

The deep crisis of 2010-12 of the photovoltaic (and wind) energies appears to have passed. The initially excessive number of producers has been drastically thinned out and consolidated by market pressures within the private sector itself, and (particularly in China) under injunctions by the authorities. The general expectation is that only a relatively small number of firms of an adequate size will be able to prosper in China and even worldwide.

The present scoreboard displays an undeniable revival in the solar energy field, especially in the US and in China. In the US, the new capacity in solar energy installed in 2014 was 418% larger than in 2009, although still only accounting for 1% of electricity generation. Yet, it is expanding faster than the other energy sources, except for gas (which is scoring a rapid growth of output, thanks to the recently unearthed shale gas deposits). But admittedly these official statistics imply a substantial underestimate, as only solar ‘farms’ are encompassed without accounting for the thousands of solar panels installed on roofs of buildings.

Boosting renewables would be particularly beneficial for the European Union, which lacks ample deposits of oil and gas. Although targets have been established in the EU up to 2030, the steps to achieve an integrated EU energy market are still inadequate. A fairly ambitious policy blueprint was issued in February 2015 which may hopefully bring about an energy union, at least to the extent possible.

In China in 2014 a further extension of capacity in the solar field was envisaged. Various concurrent factors presage a shining future in China. As a matter of fact:

- The country is confronted with serious environmental problems. Chinese cities are amongst the most polluted in the world and this creates deep anxieties amongst the population. The present upsurge in the installation of renewables reflects the somewhat belated recognition that China faces serious environmental problems, in terms of pollution of air (and water).

- Concurrently, the rapid growth in China further drives the need for energy, despite efforts now underway to improve the efficiency of energy use, which is still low. Almost all conceivable energy sources are called to the rescue. Apart from coal (abundant at home, but dirty), China also expands the capacity in the hydro and the nuclear power segments. Renewables have been accorded a priority ranking in the present Five Year Plan (2012-16). In absolute terms, China is already the top producer of wind and solar energy – a destiny which China cannot possibly escape in most statistical exercises on account of its immense dimensions.

- While Chinese firms have been successful in exporting solar panels in previous years, thus inducing the anti-dumping reaction in the US and the EU, the solar firms that survived the recent hecatomb will greatly benefit from the new dual policy plank of the government. The latter intends to redirect the solar industry away from exporting towards the domestic market and to covering the entire solar production chain instead of focusing on solar panels only. The thinning out of the number of firms in the solar energy area is another vector of industrial policy. Its aim consists in building up a few solid firms that can perform well in the international arena.

- Financing will be available, largely through the Development Bank of China, for investments in line with the new strategy for solar energy.

- Recently it was stated that private and foreign enterprises will be admitted to invest in the renewables sectors, also as regards the setting up of solar farms, whereas previously their role was circumscribed to the manufacturing of the machinery involved.[1]

6.1. The Respective Roles of Governments and Individual Firms

In the world’s media, the production and the use of renewable energies tends to be approached usually as a battle between countries, mainly involving the US, the EU and China. This approach, while an unavoidable dimension of any analysis in international trade, is rather myopic, as it tends to belittle the essential role of individual enterprises in international trade and investment. The latter are opposed as competitors but also often cooperate on specific issues. Therefore, one should not overlook that anti-dumping actions are aiming at individual enterprises from a given country, and not directly at the latter.

Governments obviously play an important role as they shape energy policies, including pricing arrangements. Besides, governments (i.e. in the EU the Commission) are also the agencies from which domestic producers solicit the imposition of trade defense instruments against what they view as ‘unfair’ competition from abroad. And, in geo-political terms, national pride cannot be ruled out in the international arena of energy strategies.

Yet, in Western market economies and in Japan private companies are the driving forces and international rivalry is primarily waged amongst them. In this connection, one must recall that often such firms have already a wide-ranging multinational profile. As will be illustrated below, and contrary to frequent allegations, the relevant decisions that led to a massive invasion of solar panels into Europe in 2008-09 were not the result of a deliberate strategy of the Chinese authorities, but were mainly engineered by a large cohort of non-public firms. Government intervention in this sector in China appears to have remained rather low. Subsidies are an exception, but until recently, the latter have also been overly generously dedicated in many European countries and in the US not only to producers, but even more to installers and end-consumers. To their discharge, one must concede that in a yet untested and immature industry, in which the firms cannot easily assess the chances of success, government support to producers (or end consumers) may be justified in the initial stages.

6.2. The Inherent Conflict-of-Interest Between Producers and Importers

A striking phenomenon in the subject area of this essay is the frequent clash of economic interests in the home countries between, on one side domestic producers who request protection against allegedly ‘unfair’ imports, and on the other side the importers of final goods (and behind them, the ultimate consumers) or firms that import intermediates which are incorporated into their final products. The solar energy case bears witness to this almost congenital conflictual configuration.