Online Platforms, Economic Integration and Europe’s Rent-Seeking Society: Why Online Platforms Deliver on What EU Governments Fail to Achieve

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: Digital Economy EU Single Market European Union

Summary

Online platforms create “more perfect” markets. Online platforms are a market-driven cure to the imperfections of the EU’s incomplete Single Market. Platforms provide well-functioning technical infrastructures that allow users to easily deal with country-specific legislation in the EU, e.g. VAT and invoicing requirements, consumer protection laws, sector-specific licenses and the particularities of national contract law.

Modern online platforms have “skin in the game”. They have an intrinsic motivation to create value for, and trust between, users and to enforce high and widely accepted standards for business conduct. In the EU, therefore, platforms encourage value-adding interactions that would not emerge without platforms when markets are locked by regulations and barriers that effectively protect insiders and deter new entrants. By doing so, platforms help consumers and businesses to “bypass” the effects of rent-seeking activities in the EU, which are at the root of significant differences in Member State regulations – and which for a long time have been known for being harmful to cross-border trade and economic integration and convergence in the EU.

The EU and some Member State governments are neither unique nor extreme in their political calls to restrict or even ban certain platform businesses from operating. Yet, Europe’s persistent hesitation – sometimes outright hostility – to platforms has to be seen in a broader perspective of political power and control. In the EU, old-fashioned national regulators have an organisational incentive to stick to and defend old approaches to regulation. In many cases, they have an intrinsic incentive to respond to vested interests in business and civil society.

At the same time, through a bottom-up trial-and-error process, online platforms culturally appropriate customs and practices of governments and regulatory authorities in regulating markets and commercial behaviour, which are often “unacknowledged” by policymakers or considered “inappropriate”. However, policymakers’ hostilities towards modern online platforms disincentivise innovative companies to invest, grow and expand within and beyond the EU, with adverse implications for the Single European Market.

“We do what you promise so why do you hate us so much?”

All the big and famous digital platforms have probably got the message by now: European policymakers don’t like them very much. Antitrust case after antitrust case has been filed against the likes of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and others. While there are good reasons for competition authorities to keep big firms on their toes and prevent competition from stagnating, it’s difficult to escape the feeling that, for platform firms, EU competition law – which is less attentive to consumer welfare – has been stretched to the breaking point in order to keep platforms on a tighter leash.

And that’s just one part of the EU’s policy armoury. The European Commission and several EU governments have advocated a special platform regulation with the effect of slowing down the competitive effect of both larger and smaller platform firms. Indeed, a new ‘special tax’ on services of digital platforms has been proposed by the Commission. Around Europe, Uber and Airbnb have been restricted – or outright banned – by national or local governments. And in the European Parliament, there have been repeated calls for breaking up platforms and companies like Google and Facebook. On top of these initiatives comes the hostile tone of argument inherent in several positions by the European Parliament, which has been the demonisation of Internet platforms for being too big, too powerful or too dangerous.

They are getting it wrong. The ascent of the platform economy has been a boon for the European economy. Online platforms encourage competition and the consumer by reducing information and trade costs in municipal, regional, national and cross-border commerce. They stimulate entrepreneurship and new economic activities, ultimately leading to economic renewal and economic convergence. Accordingly, for friends of economic integration in Europe, platforms have been powerful tools to break up local oligopolies and create access to goods and services across the EU.

In the process, online platforms have helped to expose protectionist governments in Europe that – despite nominal support for the Single Market – have introduced a series of regulations that force businesses to follow national regulatory borders rather than consumer preference. Importantly, while regulatory heterogeneity in the EU effectively reduces – or prevents – intra-EU commerce and economic integration, online platforms facilitate cross-border trade and therefore contribute to economic development and convergence. In a way, online platforms deliver on what EU institutions and governments repeatedly promised to voters – but largely have failed to achieve: creating a deeper Single Market and strengthening economic integration in Europe.

Indeed, much of what the platform economy accomplishes is firmly anchored in classic EU economic orthodoxy. The guidelines for economic policymaking, which are laid down in the Lisbon Treaty, state that the EU policymakers “shall work for […] a highly competitive social market economy” and “promote scientific and technological advance.” (Article 3 TFEU) The purpose of the Single Market is to stimulate competition and trade, to “improve economic efficiency, to raise quality, and to help cut prices” (European Commission 2018a). The intention of the EU’s new data protection policies, to give a more recent example, is to make “businesses benefit from a level playing field” in the EU (European Commission 2018b). As far as the Digital Single Market is concerned, EU policymakers explicitly aim to facilitate “better access for consumers and business to online goods and services across Europe” by removing the “key differences between online and offline worlds, to break down barriers to cross-border online activity.” (European Commission 2018c) The same spirit is heralded in trade and competition policy: EU Trade Agreements should make “European businesses, particularly SMEs, more competitive” and to encourage “Trade for All” (European Commission 2015), while competition policy is “designed to ensure fair and equal conditions for businesses, while leaving space for innovation, unified standards, and the development of small businesses” (European Commission 2018d).

There is another, perhaps much more important characteristic of modern online platforms, which is, however, rarely appreciated in the public debate: the platform economy has helped consumers to get around ubiquitous problems of rent-seeking and public policy cartels in EU policymaking. Despite efforts to reduce the legal fragmentation between markets in the EU, most markets are still organised along national lines. In addition, new regulations all too often have the effect of segmenting structures of competition along national borders. That isn’t an accident. It is the result of policymakers responding to the demands of different political or economic interest groups that fear the consequences of new competition for their market control. That said, modern digital platforms are no panacea for creating new market access for producers and consumers to other EU markets, but they have made the European market much more single.

There is a discussion to be had over each and every policy idea regarding digital platforms – and those listed above for platform businesses are far from being the only ones. But in Europe, policymakers have gone further than in other major markets to hamstring digital platforms. The revealing architecture of the policy and its evolution indicates that European policymakers are hesitant to online platforms and their effects on traditional markets, old market hierarchies, and the loss of political control over market outcomes. At the same time, many EU policymakers don’t like the design of new digital business models, which often are, however, highly welcomed by European citizens.

These are misguided views about the platform economy – and this paper argues that platforms should rather be seen as a blessing by all those policymakers in Europe that want to stimulate intra-EU integration, better market access for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), more and faster diffusion of innovation, and faster rates of regional convergence throughout the European Union.

Regulatory heterogeneity: the “rent-seeking” disease of the Single Market

In China and the US, traditional businesses and start-ups have immediate access to hundreds of millions of potential customers. Not so in the EU, where regulations of digital and non-digital industries still differ substantially across individual countries and often even within EU Member States. Since the creation of the Single European Market in 1993, attempts to harmonise national laws that regulate businesses and the markets for products and services across the EU have been a cat-and-mouse game: when old national approaches have been knocked down, new ones have risen elsewhere in the economy. Especially, with the structural change of the economy – leading to a greater role for services and digital output – the result became a European market that remains fragmented and that still comes with high costs of doing business across borders. Unsurprisingly, cross-border commerce by all those that are sensitive to regulatory differences, particularly small-, medium and micro-sized businesses, have failed to grow across intra-EU borders (see, e.g., Eurobarometer 2015).

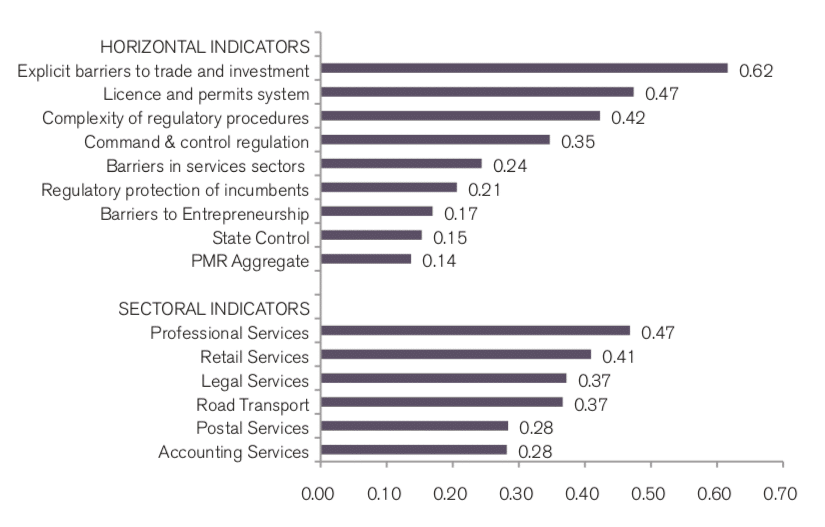

Regulatory heterogeneity is a subsidy to big business. It generally reduces the willingness of smaller firms to engage in cross-border commerce. For market regulations in the EU, survey data show substantial differences in both the scope and the restrictiveness of sectoral regulations, indicating an enduring resistance of Member State governments to give up control over many legislative and regulatory powers. Evidence on intra-EU variation in the OECD’s market regulation data shows that regulatory heterogeneity within Europe’s Single Market is still substantial. Widely differing national approaches to taxation, investment, market entry and entrepreneurship regulations limit the scope and economic significance of the Single Market. Given highly diverse sets of national rules (in different languages) for a wide range of services sectors – including transport, postal, retail and professional services (see Figure 1), the EU lacks the gravitation of large markets such as the US and China. Accordingly, the EU has – by default – a comparative disadvantage in attracting investors and innovative start-ups wishing to roll out and expand new business models.

In addition to legal fragmentation, many EU regulations are still highly restrictive for both digital and traditional (or less digital) business models. In many areas of regulation, EU Member States apply regulations that are more restrictive than in other comparable jurisdictions, and often without providing more benefits to consumers, public health, the environment or public safety. Healthcare services are a case in point, but the same case could be made for transportation services, professional services, education services and construction services. Some of these regulations have clear negative effects for intra-EU competition and quality and innovation in these industries and up- and downstream sectors. While they nominally seek to achieve non-market objectives, a key feature of different national regulations is that they effectively protect industry incumbents, decrease the contestability of markets, and reduce economic opportunities for many in the EU.

Figure 1. Cross-country regulatory heterogeneity in the EU

Source: OECD. Indicators of Product Market Regulation, 2013 (most up-to-date indicators). Own calculations. Numbers represent calculated variation coefficients based on national regulatory restrictiveness indices in 2013. The measure reflects the dispersion in national regulations for different regulatory areas. Countries in sample include Sweden, Finland, Belgium, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Austria, France, and Spain.

The problem of regulatory fragmentation is widely recognised. A study commissioned by the European Parliament (2016), points to significant market access barriers, which continue to prevail across the EU, for example:

- national technical restrictions and de facto discrimination based on country of residence,

- anticompetitive conduct and unfair trading practices,

- a lack of access to information and redress mechanisms, and

- frictions in cross-border payments and deliveries,

- national taxation rules imposing by far the greatest administrative burden for businesses.

For these reasons, the European Parliamentary Research Service (European Parliament 2017, pp. 12) highlights the “urgent need to bring EU single market rules up to date, in particular as regards online payments, e-invoicing, the protection of intellectual property rights, data protection and privacy, as well as value added tax (VAT) requirements [and points out] that measures in these areas would generate trust in e-commerce and provide more adequate protection for EU consumers, who are still more inclined to shop online at domestic shops rather than with a seller in another country.” The authors of this study indicate that the potential gain in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from a more complete Digital Single Market could amount to up to 500bn EUR per year, which corresponds to up to 3.6 per cent of EU GDP.

On current trend, however, the Digital Single Market is held back by numerous horizontal and vertical barriers hampering EU-wide commercial activities in the digital sector and the wider economy. In addition, many EU countries are among the most restrictive as regards regulations that affect digital services, while many apply highly diverse policies (Digital Trade Estimates Project 2018). Regarding the adoption of digital business models and new technologies such as algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI), there is a growing concern among policymakers that the EU is falling behind compared to other jurisdictions that have already adopted much more innovation-friendly policies (DigitalEurope 2018; Springford 2015).

High levels of regulatory heterogeneity in the EU increase businesses’ fixed cost

High levels of regulatory heterogeneity in the EU increase businesses’ fixed cost of market entry because they need to devote resources to comply with diverse country-specific provisions. As a result, private-sector business activity, particularly that of SMEs, and levels of competition still differ substantially across sectors within the EU. Survey data from Eurobarometer (2015) points to a number of systematic legal and transactional problems that SMEs face in cross-border trade within the EU. Major findings are:

- Only three out of ten SMEs in the EU either imported from or exported to another EU country.

- For SME exporters, the local market still represents the largest proportion of sales.

- Complicated administrative procedures and high delivery costs are the most common problems faced by SMEs when exporting.

- 51 per cent of EU SMEs find resolving cross-border complaints and disputes too expensive.

- 49 per cent find that that identifying business partners abroad too difficult.

- 49 per cent find dealing with foreign tax law too complicated.

- 45 per cent lack the language skills to deal with foreign countries.

- 41 per cent do not know where to find information about the potential foreign market.

Due to different regulatory regimes, low levels of competition and rigid market structures are a common feature of many industries in many Member States. As a consequence, national legal borders still exert much more negative effects on commerce within the EU than sub-federal policies do in the US, even if differences in language are taken into consideration, with adverse implications for economic diversification and economic convergence (see, e.g., Kommerskollegium 2015).

By contrast, online platforms have ushered in greater opportunities for businesses to engage in cross-border commerce. By creating more competitive level-playing fields for businesses in many sectors, modern online platforms empower regional businesses, particularly SMEs and micro businesses, which benefit most from the lower cost of doing business with other countries. Against this background, it is no surprise that almost half (42 per cent) of SME respondents to a recent Eurobarometer (2016) survey on online platforms already use online marketplaces such as Amazon to sell their products and services. At the same time, a great majority (82 per cent) of those firms that sell online rely on search engines to promote their products and/or services.

Online platforms: a market-driven cure to the imperfections of the EU’s incomplete Single Market

The ascent of the platform economy has boosted the growth of commercial activities in the EU. Both online intermediation platforms and online advertising networks have spurred commercial interactions between the suppliers and the consumers of content, goods and services. Importantly, both search engines and online marketplaces created trust among platform users of different countries, nationalities and cultures by significantly decreasing search and information costs (Martens 2016). In this chapter, we will walk through key economic aspects of the platform economy and the role they play in the EU.

Online platforms create “more perfect” markets

Benchmarked against the model of perfect competition and real-world frictions in goods and services markets, modern online platforms improve markets and the process of market mediation. Perfect competition describes a market structure where competition is at its greatest possible level. Online platforms are characterised by different network effects and it is these effects that allow platforms to make markets much more competitive. In theory, a perfectly competitive market is characterised by

- an infinite number of buyers and sellers,

- no barriers to entry,

- perfect factor mobility (inputs in production processed, e.g. information, land, labour and capital),

- perfectly available information, and

- zero transaction cost.

Generally, network effects (also known as network externalities) are the positive effects that additional users of a certain platform have on the value of the same platform to others. Because of direct network externalities, online platforms become more valuable for both sellers and buyers when the overall number of connected users grows. In addition to network effects, many platforms – e.g. Google’s search engine and Amazon’s online marketplace, two of the most successful online companies operating in the EU – benefit from economies of scale. Google’s search machine, for example, gets better the more people use it because more data helps the platform to improve its algorithms. Similarly, Amazon’s size allows the platform to operate more efficiently (less platform operation cost per user), allowing it to pass on savings to sellers and consumers (these are scale externalities, not necessarily network externalities).

Modern online platforms are characterised by three major network externalities (see, e.g., Evans and Schmalensee 2017): the usage externality, the membership externality and the behavioural externality.

- A usage externality is created when online platforms enable or facilitate transactions between the two or more sides conditional on their willingness to interact. Accordingly, both consumers and the suppliers of content, goods or services benefit when each uses the system to make a transaction.

- Membership externalities result from additional membership on one side, which benefits the opposite side. In other words, using online platforms is more valuable to one side the more members of the other side join the platform, since that increases the likelihood of a value-creating transaction.

- Behavioural network externalities result from online platforms’ intrinsic motivation to be good governors and the need to manage the behaviours of their members. In their motivation to create trust between the members, online platforms design standards and enforce rules against harmful conduct, which otherwise would reduce the value of its platform for other users.

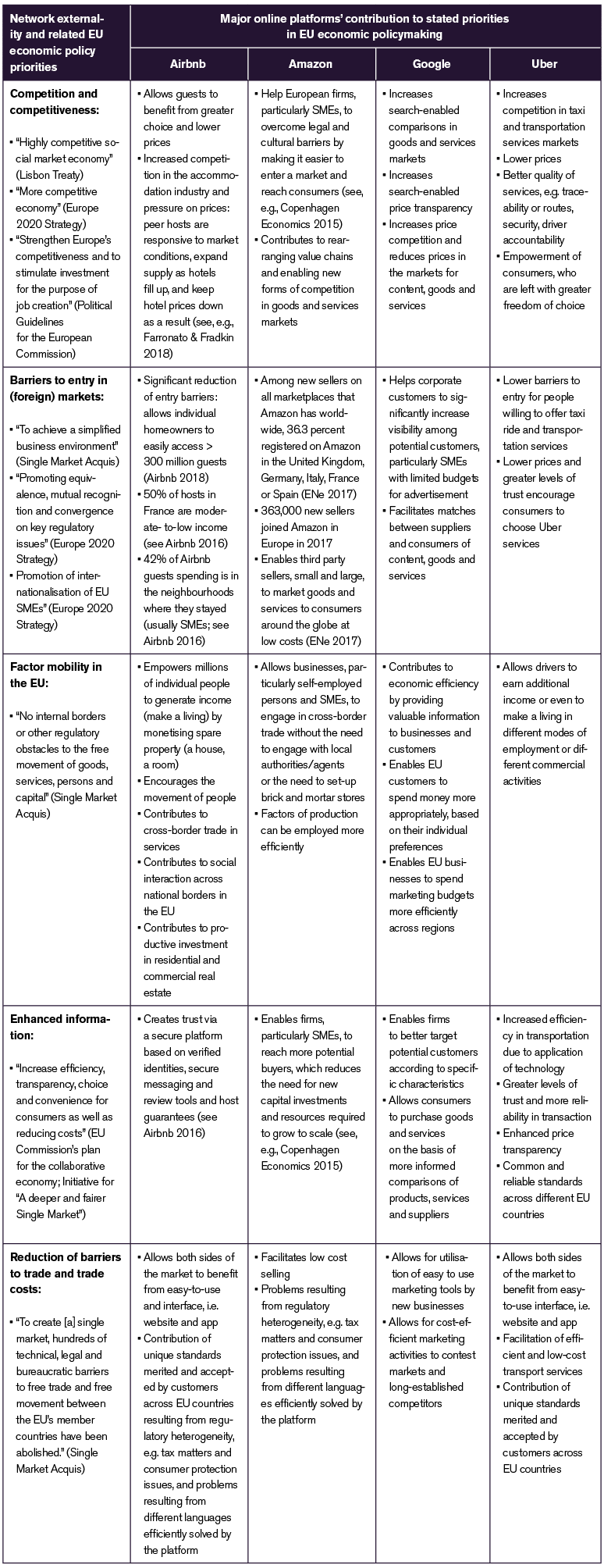

Due to network effects and platform operators’ intrinsic incentive structure, a common though unique feature of modern online platforms is that they tend to improve all properties of competitive markets at the same time, and thereby create better markets for both sides of the market, i.e. consumers and sellers. Figure 2 provides an overview of online platforms’ network effects and explains how they impact on marketplace competition.

Figure 2. Network externalities and online platforms’ contribution to “more perfect” competition

Source: ECIPE.

The utilisation of network effects by platform users significantly contributes to commerce inside Member States and, in addition, promotes economic integration in the EU. Platforms allow European citizens, i.e. consumers and businesses, to easily engage in economic transactions with each other, regardless of whether transactions take place at the municipal level (e.g. restaurants, taxi services) or across EU borders (e.g. hoteling, road and air transport, e-commerce services). Importantly – and different to common notions of the disruptive impact of platforms –, the “disruptive economic value” of modern online platforms in the EU is that they encourage transactions in markets that are either characterised by regulations not conducive to commerce inside EU Member States or regulations that hamper or even prevent commerce between citizens and businesses located in different Member States.

Uber, for example, created new, fast-growing niche markets for transport services in the EU, which are still tightly and differently regulated in individual EU Member States (and have traditionally been among the most regulated markets in the world, characterised by considerable problems of regulatory capture; see, e.g., OECD 2007). The same is true for Airbnb, which injected new types of accommodation services into regional markets for lodging services in the EU. The e-commerce platform Amazon provides unique and significant value to millions of businesses willing to enter foreign markets inside the EU’s fragmented Single Market at low costs. And even if it has not been appreciated by competition officials, Google’s Android mobile phone system has allowed millions of European smart-phone users to easily buy and install thousands of apps developed by foreigners (see, e.g., Oxera 2018).

Against the background of legal fragmentation in the EU, platforms provide well-functioning technical infrastructures that allow users to easily deal with country-specific VAT and invoicing commitments, consumer protection requirements and the particularities of national contract law, i.e. to cope with significant differences in horizontal regulations that are known for being harmful to cross-border commerce and investment.

Moreover, trends in platform approaches to self-regulation and safeguarding measures to protect legitimate interests of consumers, producers and suppliers (i.e. so-called behavioural externalities of online platforms) illustrate that online platforms increasingly compete with public regulators and public consumer protection agencies for standard-setting power and publicly accepted standards respectively. In June 2018, for example, eBay, Amazon and others signed a “Product Safety Pledge” by which they agreed to a series of commitments to ensure EU consumers are well protected (European Commission 2018).

More detailed examples of how major online platforms facilitate “more perfect competition” and at the same time contribute to the EU’s stated political priorities, particularly the objective to promote intra-EU trade and economic integration, are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Major online platforms’ contribution to “more perfect competition” and to stated EU policy priorities

Platforms are essential to create a digital single market and to make that EU ambition real

Online platforms should not be considered a threat to marketplace competition in the EU. On the contrary, thanks to their unique capacities to facilitate and grow commerce and entrepreneurship, platforms should be considered a natural vehicle for competition and the economic empowerment of many. As found by Stripe (2018, p. 1), for example, even though many online platforms benefit from first-mover advantages (also known as the-winner-takes-it-all situation), platforms continue to “compete on product quality against persistent rivals, much like traditional businesses without substantial network effects.“ The findings also indicate that industries are likely to see various competing marketplaces in the future.

For Europe, this is all the more important. Single Market reforms are unlikely to remove the systemic regulatory fragmentation between its Member States anytime soon. In many Member States there are powerful incumbents, who have successfully adjusted to national laws and regulatory procedures, that stand in the way for broader regulatory convergence, particularly in services sectors. There’s a historical path dependency: regulatory heterogeneity and incumbency protection are intertwined. Both can be major sources of inefficient resource allocation in many industries – irrespective of whether they find themselves in primary sectors, manufacturing or services industries. It follows, therefore, that the paramount task for policymakers in the EU should be to reduce the barriers that hold digital business models back from transforming European economies faster than today and to promote economic convergence (Bauer and Erixon 2016). Addressing this challenge would also be a catalyst for marketplace competition in the EU and appease competition authorities.

On current trend, however, the ambitions of those who like the idea of more marketplace competition in a less fragmented (Digital) Single Market are unlikely to materialise. In the past, EU institutions and Member State governments neither designed nor developed institutions whose economic and social achievements come close to the merits of modern online platforms in enabling informed interactions between producers, suppliers and consumers of different EU Member States. And the EU, which is suffering from a number of legitimacy crises (see, e.g. Schweiger 2018; Wood 2018; Chalmers et al. 2016), is unlikely to do so in the future: too many EU and national policymakers don’t like the idea of innovation-friendly open markets, digitalisation, competition and creative destruction.

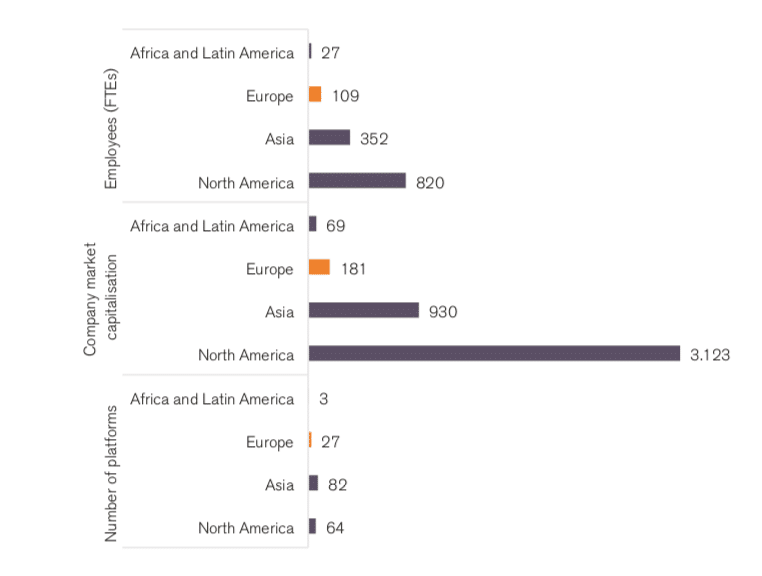

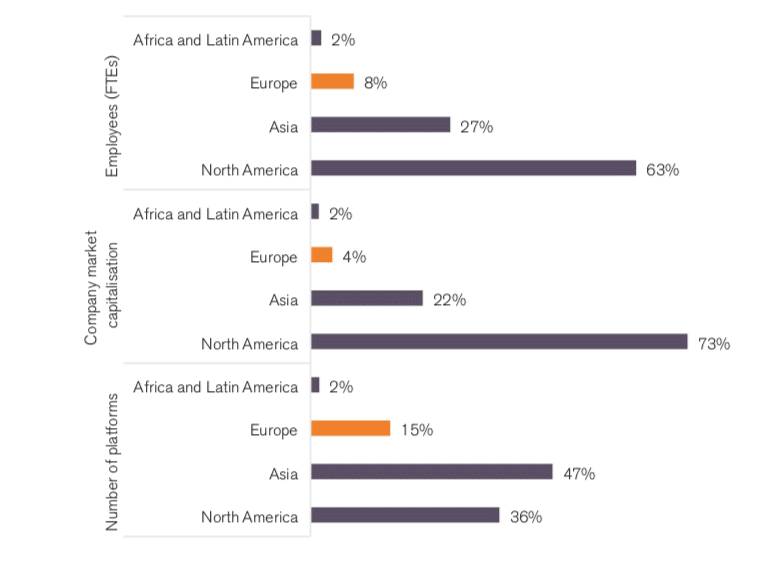

While questions of identity and economic nationalism dominate political debates, Europe is likely to continue trailing the US and Asia in platform developments and usage (see Figure 2 and 3), preventing EU citizens from enjoying the “disruptive value” that online platforms create for citizens, firms and workers alike. Thereby, the public hostilities against large digital companies and political discontent about the success of their platforms are to a large extent rooted in vested interests in both the private sector and governmental institutions, defending their own (political) business models.

Figure 3. Platform companies by region, absolute numbers

Source: The Center for Global Enterprise (2016). FTE = full time equivalents.

Source: The Center for Global Enterprise (2016). FTE = full time equivalents.

Figure 4. Platform companies by region, percentage numbers

Source: The Center for Global Enterprise (2016). FTE = full time equivalents.

Source: The Center for Global Enterprise (2016). FTE = full time equivalents.

Understanding the hostility to the platform economy

The ascent of the platform economy has given rise to negative political and regulatory receptions in several parts of the world. In Europe, there is the oft-repeated view that platforms are less beneficial to the European economy because most of the big platforms are American (and more recently Chinese). It should be noted though that the economic benefit (i.e. additional economic activities and wealth creation) of new technology and market innovation comes much more from the actual use of new goods and services, not from their creation. Yet the persistent hesitation – if not outright hostility – to platforms has to be seen in a broader perspective of political power and control.

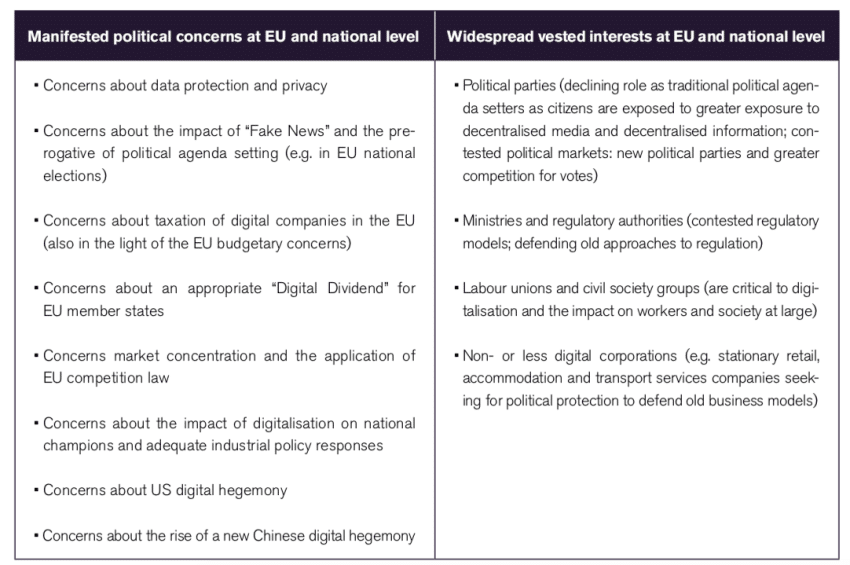

Bypassing the “rent-seeking” externality

Rent-seeking activities have for a long time preserved anti-competitive market structures and patterns in profits and earnings (see, e.g., OECD 2018). Generally, rent-seeking occurs when individuals, businesses, or governmental institutions attempt to use government laws and regulations to defend or increase personal incomes, profits or political privileges. Rent-seeking is most common when companies and/or public institutions aim to defend existing businesses or regulatory models and have sufficient economic or political influence to do so (see Table 2). A company may, for example, seek laws for import protection from the government. Regulatory agencies may seek to maintain regulatory powers even though economic developments, social trends or new technologies rendered them obsolete. And political institutions may seek rents by seizing control of certain business operations of private-sector companies (and other features of state capitalism). In addition to these phenomena, political hostilities against online platforms in the EU are also shaped by traditional political parties, which, as a consequence of social online media (e.g. Google, Facebook, Twitter etc.), decentralised information and new political narratives, are exposed to greater levels of competition in political agenda setting and new political groups respectively.

Table 2. Political economy determinants of EU policymakers’ hostilities towards modern online platforms

The platform economy plays a critical role in helping consumers to deal with the malaise of politically defined and protected markets. Besides the recognised network externalities, the platform economy has an additional quality that is critically important for economic integration in Europe: it bypasses markets characterised by rent-seeking regulation. For want of a better word, let us call it the “bypass–rent-seeking externality” of online platforms.

The bypass-rent-seeking externality can be described as follows: based on their intrinsic organisation-specific motivation to create value for and trust between their members (users, businesses, consumers), online platforms design and enforce widely-accepted standards and rules for user conduct. As creators of trust, they encourage value-adding interactions that would not emerge without platforms when markets are locked by regulations and barriers that protect insiders and deter new entrants. Section 2 has already outlined many of these barriers, e.g. country-specific tax laws, labour market and wage regulations, transportation and shipping regulations, retail regulations, national contract law, and consumer protection laws. The platform economy creates a brand-new opportunity for consumers and businesses to engage in formerly non-existent or inaccessible markets.

Most observers accept this quality of platforms, but many policymakers in the European Commission and the Parliament are less certain about the extent to which such developments should be encouraged. At the same time, political rent-seeking does not happen by accident: it is the result of actions by regulators and businesses that have benefited from old regulations that distribute gains to some actors, but not to others. As a result, market developments that diminish the size of these gains will not be universally accepted. This is why so many of the regulations that also constrain platforms have emerged from those companies that have previously benefited from regulations that made markets to follow national borders rather than the preferences of consumers. Well-defended horizontal regulations in the EU include national tax codes and tax exemption policies. Country-specific vertical regulations are dominant in the services sectors, e.g. financial and insurance services, healthcare, transport services (public transport, taxi, railway), construction services, architectural services etc.

Better markets and renewed forms of economic internationalism

The network effects of platforms tend to create markets that function better. In a similar vein, the possibility of platform users to bypass the commerce-prohibitive effects of regulations also drives new and better forms of economic internationalism. What can be described as “Skin in the Game” (Taleb 2018), i.e. the extent of decisionmakers personal stakes in particular outcomes, works as an intrinsic motivation of platform operators to deliver effective regulatory outcomes that are accepted by citizens across borders (or in trade policy lino: rules accepted at multilateral level). Accordingly, the lack of skin in the game in politics, ministries and regulatory authorities can delay or even prevent much needed and/or much-communicated policy change.

For the EU, the notion of “false internationalism”, a term used by Germany’s influential post-war scholar Wilhelm Röpke (1954) helps explain why legal market fragmentations are a salient feature of the EU’s Single Market. It also puts additional light on why governments and regulators have been overly hostile to online platforms, which tend to be much better equipped to facilitate and govern economic interactions and serve citizens preferences respectively. For Röpke, internationalism couldn’t be created from above – by political instruction. He argued that economic internationalism commonly “springs from more dubious motives, such as faulty thinking, inability to comprehend the problems, or, what is worse, the aversion to tackling the real tasks involved in a radical reform of society, and finally the endeavour to meet the desire of the peoples for smoothly-functioning international interrelations by means of sham solutions on the principle of ‘ut aliquid fieri videatur’“[1] (Röpke 1959, pp. 17)

As argued by Sally (1998, pp. 196-97), all too often “international regimes are manifestations of government failure transplanted to the international level.” Real internationalism emerges “bottom-up – not “top-down” – by the actions of consumers and businesses that find value in interacting with each other. This is true of all voluntary exchange – and it is a particularly acute element of the platform economy. This economy has grown “bottom-up” and, assisted by real market innovation, has caused patterns of exchange that have been distant from whatever prescriptive behaviour that many market regulations incite. Despite many – and growing – frictions in the world economy, it is notable that platforms like Amazon, Alibaba or Facebook continue to create manifest change in market behaviour and lead the world economy towards more integration. Even if that outcome is welcomed by most observers, it has also provoked fears and reactions among those that have lost their previous market power and their ability to control how patterns of economic exchange should develop.

Cultural appropriation: the neck-breaker for modern online platforms?

A systematic problem that most modern online platforms face in the political domain can be described as “cultural appropriation”. Cultural appropriation, a term coined by social scientists in the early 1990s (see, e.g. Coombe 1993), refers to the “unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society” – or simply the adoption of elements of a minority culture by members of the dominant culture (see, e.g., Oxford Dictionaries). Applying this concept to digital platforms and politics, online platforms can be viewed as competitors – or substitutes – to historically dominant regulators that feel threatened by the rise of the platform economy.

One outstanding feature of modern online platforms is that they have an incentive to be good governors to satisfy their users. On the one hand, they “are indescribably thin layers that sit on top of vast supply systems” Goodwin (2015). On the other hand, they are hybrids characterised by the incentive structures of private businesses and traditional competences of governments or public regulatory authorities. In other words, as outlined by Skinner (2018), companies like “Amazon, Facebook, Google, Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba, Uber, Twitter and co have nothing but a critical mass of buyers and sellers, content producers and content consumers, drivers and passengers that are connected through their platforms. Their platforms then need to manage the behaviours of their constituencies: in other words, to be good governors.”

In a similar vein, early in 2018 Jack Ma, the executive chairman of Alibaba Group, said that online platforms operate more as governors rather than managers of a company: “At Alibaba we treat it more like governing an economy, as we have to manage so many companies dependent upon us as partners. By 2036 we will have built an economy that can support 100 million businesses for billions of users. We won’t own that economy. We will just govern it” (quoted by Skinner 2018).

Modern online platforms apply and enforce regulations that serve citizens’ legitimate public interests – regulations or equivalents thereof, which in the past have been exclusively enforced by governmental institutions. And by doing so, they create safe and reliable, e.g. trusted, marketplaces for their users. As the rules of these marketplaces are widely recognised by users across different nationalities, platforms have been fuelling commerce across national and legal borders in the EU. What’s important from a political economy perspective: online platforms tend to increase citizens’ awareness that existing regulations, which have been invented by (often politicised) public institutions, are either inappropriate, not fit for purpose anymore or even detrimental to the achievement of associated policy objectives. Given that online platforms pose a challenge to traditional regulatory control by law, it should not come as a surprise that many policymakers in governments, ministry officials and regulatory authorities have been quick to join the bandwagon of platform sceptics.

[1] The Latin term “ut aliquid fieri videatur” translates to “pretending to do things for the better” or “doing something for the sake of appearing that action is being taken”.

Rent-seeking and the erosion of online platforms comparative advantages

Online platforms are increasingly “appropriating” the customs and practices of governments and regulatory authorities in regulating markets and commercial behaviour. Despite the fact that online platform activities emerged “bottom-up”, i.e. through a trial-and-error process in an attempt to best serve users, the customs and practices of platforms are often “unacknowledged” by policymakers or considered “inappropriate”. A case in point is the criticism of Google’s Android platform: Google’s business model, as well as the customs and practices that govern technical standards and interoperability across platforms, have been deemed anti-competitive by the European Commission. The social value of the ecosystem created by Android has largely been neglected by the Commission, e.g. the “virtuous circle of growth on both sides of the market,” such as greater diversity and competition among of Android-powered devices and an ever-increasing range of software applications for smartphones (see, e.g., Oxera 2018, p. 28). Similar considerations hold for online advertising platforms such as Facebook and Google whose socio-economic value is not exclusively created in the Silicon Valley, but to a large extent on European streets and European firms including millions of European SMEs.

Importantly, traditional public regulators have an organisational incentive to stick to and defend old approaches to regulation. In many cases, they also have an intrinsic incentive to respond to vested interests in business and civil society. Europe is neither unique nor extreme in that sense, but these incentives have already defined political calls in the EU to restrict or even ban certain platform businesses from operating. Some of the most striking examples are Uber, Lyft and Airbnb: federal and sub-federal regulators have an organisational incentive to regulate or even ban innovative, self-regulating and safe ride-sharing platforms such as Lyft and Uber (Dickinson 2018a) or online platforms offering peer-to-peer accommodation services (Dickinson 2018b).

Due to their competitive impact on many existing traditional, and usually less digital, businesses, modern online platforms are highly exposed to rent-seeking activities intended to privilege incumbents. Firms that have succeeded with existing business models often look to governments as their first line of defence against platform-driven competition. Voicing concerns about public safety, lacking quality or job losses, they have frequently lobbied against the new entrants. Ride-sharing platforms, for example, are accused of exploiting workers and putting passengers at risk. Amazon and other e-commerce platforms are accused of putting stationary retail stores under such pressure that many of them have to lay off workers, and short-term rental platforms are accused of depriving citizens of affordable housing.

Similarly, even though it is shown that the EU’s arguments for imposing special taxes on online intermediation and online advertising services are based on data and analyses with little association with the reality of corporate taxation (see, e.g., Bauer 2018a; 2018b and PWC 2018), taxes on digital services are is still supported by Brussels and some EU finance ministries (see, e.g., Bhatti 2018; Reuters 2018; Sledz 2018; Smyth 2018). At the same time, official documents indicate clearly that the proposal to tax the “digital sector” is linked to ambitions of expanding the fiscal power of European institutions (see, e.g., European Commission 2018f). As regards the decision to fine Google for bundling certain app services to its mobile operating system Android: it explicitly disregards the beneficial effects on marketplace competition for mobile software apps and cell phones (see, e.g., Akman 2018; Morris 2018; Oxera 2018) but it was welcomed by some of Google’s major competitors, who also happen to be companies that have profited from fragmented markets in the EU (OIP 2018).

In the EU, existing regulations and political decisions targeted at modern online platforms effectively increase users’ transaction costs. Political measures that erode the unique network externalities of platforms also erode their comparative advantage over traditional businesses. Online platforms can only pass on their benefits to users if transactions costs are low. It is exactly for this reason that platform providers created new, more transparent and more competition-friendly marketplaces in the EU. And it is for this reason that modern online platforms contributed to significant reductions in the transaction cost of entire cross-border supply chains in Europe.

The number of users of modern online platforms in the EU testifies to their contribution to the diffusion of digital services and economic opportunities enabled by digital technologies. This is true for online sellers of physical goods and non-digital services, content providers and app developers. A special tax on certain digital services would effectively erode Europeans’ benefits from the use of online platforms. Similarly, the European Commission’s demand on Google to exclude some of its services from an online platform that is offered for free to many hardware device manufacturers, hits all those who already have invested in Android-based software and hardware technologies and benefits those that run on other platforms not affected by the EU’s verdict. Figure 2 provides a more detailed overview of how these policies impact on platforms network externalities. Generally, such policies render marketplace competition more imperfect, increase the barriers to entry for platform users, slow down or even reverse the use of factors of production, hamper the diffusion of information, and increase the costs of commercial and social interactions. In addition, such policies send strong warning signals to those considering setting up shop in the EU as investors, start-ups or innovators.

Figure 5. EU policies/decisions eroding online platforms’ network externalities

Conclusions

Online platforms are often accused of exploiting market power and, due to their disruptive impacts on consumer choice, considered a threat to traditional businesses. What’s often neglected in the debate about the economic impact of online platforms is that they help European consumers to get better access to goods and services and that they spark new life into markets that often have been politically defined and protected. Looking at what online platforms have achieved in the past decade, they should be considered a blessing for the European Single Market and a catalyst for competition and economic and social integration in the EU.

Considering stated EU policy objectives, modern online platforms live up to the promises raised by politicians and government officials alike. They enhance diversity in commercial activities in the EU, they promote business models and product innovation, they create new economic opportunities, they allow for more SME engagement and, after all, they deepen integration within the Single Market and encourage regional economic development.

In Europe, layers upon layers of laws and regulations in non-digital sectors significantly hamper digital businesses in their efforts to gain scale and economic clout within and beyond the EU. Europe’s complex rent-seeking society is biased to defend the status quo. On top of that, political decisions whose real-world implications effectively erode online platforms’ beneficial network effects send strong warning signals to investors and innovators. Given the significance of legal fragmentation in the EU, Europe does not have the same gravity of market size compared to the US and China, which renders platform-friendly policies even more important to encourage innovators – from inside and outside the EU – to set up shop in the EU.

Modern platform companies have grown “bottom-up” through a trial-and-error process about how best to cater to the preferences of their users. It is partly because of the close proximity to users and consumers that platforms are often vilified by governments and competitors. Governments and regulatory authorities have all too often displayed an organisational incentive to defend old approaches to regulation – approaches that respond to the economic reality offline and that aren’t neutral to technology and business models. Accusing online platforms of being too big, too powerful or too dangerous disguises the fact that governments’ capabilities to create jobs and high value-added activities and to spur competition and economic development are fairly limited.

The sometimes-toxic debate about online platforms bears the risk that policymakers lose sight of the fragmentary nature of the EU’s non-digital markets and online platforms’ contribution to cure many of the Single Market’s defects. The European platform economy has not been as successful as in many parts of Asia and in the United States. 18 of the Top 20 tech companies are headquartered in the Western US and Eastern China. Indeed, platforms operating on online search, e-commerce and social media have a solid competitive edge over new entrants. However, revolutionary business models continue to spark far-reaching disruptions in other industries in which European companies are still strong, e.g. automotive, manufacturing, financial services, healthcare services, and retail services.

EU policymaking today will have an impact on future investment, innovation and absorption of digital technologies in the EU. The hostilities against large digital companies and modern online platforms, which provide disruptive value to European citizens, are likely to further disincentivise innovative companies to invest, grow and expand within and beyond the EU. To become a tech powerhouse in these and other industries, the EU has a long way to go in deepening the European Single Market, especially across conventional, non-digital sectors. More regulatory constraints on modern platform businesses, e.g. special taxes on digital services or narrow and discriminatory interpretations of EU competition law, would further disincentive innovative companies to invest, grow and expand within and beyond the EU.

References

Airbnb (2018). Fast Facts. Available at https://press.atairbnb.com/fast-facts/.

Airbnb (2016). Airbnb and Europe. Presentation by Patrick Robinson, Head of Public Policy EMEA. Available at https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&ved=0ahUKEwiy0InJyqbcAhUDzqQKHf53DIUQFghBMAI&url=http%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2FDocsRoom%2Fdocuments%2F18321%2Fattachments%2F13%2Ftranslations%2Fen%2Frenditions%2Fpdf&usg=AOvVaw1xHWHJ1g5s85TkKKA_eD5L.

Akman, P. (2018). Will the European Commission’s Google Android Decision Benefit Consumers?. Truth in the Market. Published on 19. July 2018. Available at https://truthonthemarket.com/2018/07/19/will-the-european-commissions-google-android-decision-benefit-consumers/. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

Bauer, M. (2018a). Digital Companies and Their Fair Share of Taxes: Myths and Misconceptions. ECIPE Occasional Paper 03/2018.

Bauer, M. (2018b). Five Questions about the Digital Services Tax to Pierre Moscovici. ECIPE Occasional Paper 04/2018.

Bauer, M. & Erixon, F. (2016). Competition, Growth and Regulatory Heterogeneity in Europe’s Digital Economy. Working Paper 2/2016. Five Freedoms Project at ECIPE.

Bhatty, J. (2018). Austria to ‘Campaign’ for EU Digital Tax Support. Bloomberg. Published on 23 July 2018. Available at: https://www.bna.com/austria-campaign-eu-n73014477815/. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

The Center for Global Enterprise (2016). The Rise of the Platform Enterprise – A Global Survey. New York, January 2016.

Chalmers, D., Jachtenfuchs, M. and C. Joerges (2016). The End of the Eurocrats’ Dream: Adjusting to European Diversity. Cambridge University Press.

Coombe, R. J. (1993). The Properties of Culture and the Politics of Possessing Identity: Native Claims in the Cultural Appropriation Controversy. Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence. Volume 6, Issue 2 July 1993, pp. 249-285.

Copenhagen Economics (2015). Online Intermediaries – Impact on the EU Economy. October 2015.

DigitalEurope (2018). Accelerate to a trusted Digital Single Market. February 2018.

ECIPE, (2018). Digital Trade Estimates Database. Available at: https://ecipe.org/dte/.

Evans, D. S. & Schmalensee, R. (2017). Multi-Sided Platfroms. In: Palgrave Macmillan (eds) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan. London.

Financial Times (2018). Why is Britain leaving the single market for services? Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/16c9fea6-8501-11e8-96dd-fa565ec55929. Accessed on 17 July 2018.

Dickinson, G. (2018a). How the world is going to war with Uber. The Telegraph. Published on 26 June 2018. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/where-is-uber-banned/. Accessed on 20 July 2018.

Dickinson, G. (2018b). How the world is going to war with Airbnb. The Telegraph. Published on 8 June 2018. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/where-is-airbnb-banned-illegal/. Accessed on 20 July 2018.

ENe (2017). 363 thousand new sellers joined Amazon in Europe. Ecommerce News Europe. $ December 2017.

Eurobarometer (2016). Flash Eurobarometer 439, The use of online marketplaces and search engines by SMEs. June 2016.

Eurobarometer (2015). Flash Eurobarometer 421. Internationalisation of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. October 2015.

European Commission (2018a). The European Single Market. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market_en. Accessed on 5 July 2018.

European Commission (2018b). 2018 Reform of EU Data Protection Rules. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/priorities/justice-and-fundamental-rights/data-protection/2018-reform-eu-data-protection-rules_en. Accessed on 5 July 2018.

European Commission (2018c). Better access for consumers and business to online goods. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/better-access-consumers-and-business-online-goods. The EU’s rules on competition. Accessed on 5 July 2018.

European Commission (2018d). 2018 Reform of EU Data Protection Rules. Available at https://europa.eu/european-union/topics/competition_en. The EU’s rules on competition. Accessed on 5 July 2018.

European Commission (2018e). European Commission and four online marketplaces sign a Product Safety Pledge to remove dangerous product. Press release. 25 June 2018.

European Commission (2018f). Modernising the EU Budget’s Revenue Side. 2 May 2018.

European Commission (2016). Annual Report on European SMEs 2015/2016.

European Commission (2015). Trade for All – Towards a more responsible trade and investment policy.

European Commission (2010). Communication from the European Commission, Europe 2020 – A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. 3 March 2010.

European Parliament (2017). Mapping the Cost of Non-Europe, 2014-2019, Fourth Edition. European Parliamentary Research Service, December 2017.

European Parliament (2016). Reducing Costs and Barriers for Businesses in the Single Market. Study for the IMCO Committee. April 2016.

Farronato, C. & Fradkin, A. (2018). The Welfare Effects of Peer Entry in the Accommodation Market: The Case of Airbnb. NBER Working Paper No. 24361. Issued in February 2018, Revised in March 2018.

Goodwin, T. (2015). The Battle Is For The Customer Interface. Published by TechCrunch. 4 March 2015. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2015/03/03/in-the-age-of-disintermediation-the-battle-is-all-for-the-customer-interface/. Accessed on 10 July 2018.

Kommerskollogium (2015). Economic Effects of the European Single Market. Review of the empirical literature. Swedish National Board of Trade, May 2015.

Martens, B. (2016). An Economic Policy Perspective on Online Platforms. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies Digital Economy Working Paper 2016/05.

Morris, J. (2018). The European Commission’s Google Android decision takes a mistaken, ahistorical view of the smartphone market. Truth on the Market. Published on 23 July 2018. Available at https://truthonthemarket.com/2018/07/23/the-european-commissions-google-android-decision-takes-a-mistaken-ahistorical-view-of-the-smartphone-market/. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

OECD (2018). Market Concentration – Note by Jason Furman Prepared Testimony to the Hearing on “Market Concentration”. Paris, 7 June 2018.

OECD (2015). Taxi Services: Competition and Regulation. Document replacing the same document from September 2018. Paris, 8 April 2015.

OIP (2018). The OIP welcomes the European Commission’s Android decision against Google. Published on 18 July 2018. Available at http://www.openinternetproject.net/news/102-the-oip-welcomes-the-european-commission-s-android-decision-against-google. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

Oxera (2018). Android in Europe – Benefits to consumers and business. October 2018.

PWC (2018). Understanding the ZEW-PwC Report “Digital Tax Index, 2017”. April 2018. Available at https://www.pwc.com/us/en/press-releases/2018/understanding-the-zew-pwc-report.html. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

Reuters (2018). European Finance Leaders Press for Digital Tax at the G20 Meeting in Argentina. Reuters News. Published on 25 July 2018. Available at: https://www.firstpost.com/tech/news-analysis/european-finance-leaders-press-for-digital-tax-at-the-g20-meeting-in-argentia-4807241.html. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

Röpke, W. (1954). International Order and Economic Integration. Reidel Publishing. Avalibale at https://mises-mdia.s3.amazonaws.com/International%20Order%20and%20Economic%20Integration.pdf.

Sally, R. (1998), Classical Liberalism and International Economic Order: Studies in Theory and Intellectual History. London.

Schweiger, C. (2018). Exploring the EU’s Legitimacy Crisis. The Dark Heart of Europe. New Horizons in European Politics series, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sledz, R. (2018). Greek Government Supports EC Digital Tax Proposals. Thomson Reuters. Published on 20 April 2018. Available at: https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/blog/greek-government-supports-ec-digital-tax-proposals/. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

Skinner, C. (2018). What did Jack Ma say? Available at https://thefinanser.com/2017/07/jack-ma-say.html/. Accessed on 10 July 2018.

Smyth, P. (2018). EU finance ministers give cool reception to digital tax plan. The Irish Times. Published on 29 April 2018. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/eu-finance-ministers-give-cool-reception-to-digital-tax-plan-1.3478055. Accessed on 27 July 2018.

Springford, J. (2015). Offline? How Europe can catch up with US technology. Published by the Centre for European Reform.

Stripe (2018). How do Marketplaces Compete? The View from Stripe Connect. Study conducted by Nate G. Hilger, Stripe Inc. 2018.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas (2018). Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life. Penguin Random House, New York.

Wood, M. (2018). Europe’s legitimacy crisis isn’t just about identity, it’s about institutions. Blog published at EUROPP. Available at http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2017/07/03/europe-legitimacy-crisis-identity-institutions/. Accessed on 27 September 2018.