Memo to Ursula von der Leyen and António Costa: Make the Right Priorities for the EU-CELAC Summit 2025

Published By: Renata Zilli

Subjects: European Union Latin America

Summary

The EU–CELAC Summit in Santa Marta, Colombia, in November comes at a time when both regions need to get down to business. The EU-CELAC cooperation has long offered both sides opportunities to advance their economic and strategic interests, but so far, they have not used them. Past summits have rarely moved beyond lofty declarations and have not matched the level of expectations. Since the first Rio Summit in 1992,[1] successive joint meetings between the two regions have highlighted shared values and cooperation on democracy, economic development, and sustainability. Yet, two decades of summitry have not yielded the tangible progress that citizens and businesses expect. In a world of heightened geopolitical rivalry, technological disruption, and recurring supply shocks, Europe and Latin America should make a deeper investment in their relationship. For the European Union, reducing overdependence on a small number of suppliers has become a strategic priority. For Latin America and the Caribbean, diversifying trade and investment partners is essential to avoid being squeezed between the US and China in their strategic competition. A forward-looking agenda on trade and economic security can transform EU–CELAC relations into a strategic Atlantic partnership. This agenda should prioritise:

- Deepening EU-CELAC economic security cooperation to mitigate supply chain shocks and the weaponisation of economic dependencies through trade diversification.

- Promoting the integration of regional value chains by fostering diversified comparative advantages across CELAC countries, enabling each to specialise in different segments of production.

- Funding digital infrastructure: Utilise the EU-LAC Global Gateway Investment Agenda to plug investment gaps, specifically in digital transformation.

- Completing trade agreement implementation: Use the cooperation to propel the full implementation of Association and Trade Agreements between the EU and CELAC partners, and accelerate the ratification of signed agreements while pushing ongoing processes like the modernisation of agreements with Mexico

- Make the EU-CELAC cooperation a springboard for a “Coalition of the Willing” for a rules-based international trade.

[1] The first high-level meeting between the European Community and Latin American and Caribbean countries took place in 1999, launching the EU–LAC Strategic Partnership. This dialogue evolved into the current EU–CELAC framework in 2013, when the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States became the EU’s formal counterpart, giving the relationship a more structured and political foundation

1. Introduction: The Santa Marta Moment

The upcoming EU–CELAC Summit in Santa Marta will test whether Europe can still turn diplomacy into delivery. Political turbulence across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)—weak coalitions, electoral cycles, and eroding public trust—means that many regional leaders are approaching this summit with scepticism and may not even attend. For them, the EU often looks like a distant partner with good intentions but limited impact.

The challenge for EU leaders at the summit is therefore to demonstrate that partnership with the EU delivers tangible economic and strategic value at a time when LAC economies face fiscal pressures, volatile commodity prices, and US protectionism. While the EU’s trade and investment footprint in the region remains large,[1] its relative weight is shrinking, both in commerce and in political imagination. While China has become the main trading partner for the majority of LAC countries, the US remains their main security interlocutor. Therefore, the EU should come to the summit and demonstrate why it remains relevant – not merely as an aid donor, but as a genuine partner for growth, diversification, and economic security.

The last EU-CELAC meeting, held in Brussels in 2023, took place after an eight-year hiatus – a remarkably long pause considering mounting economic, political, and environmental problems. While different motives explain the limited diplomatic activity – and fingers are pointed across regions –the reality is that it takes two to tango. Over the last years, the priorities for actors in the two regions have diverged, directing all sides to address their own domestic or regional crises.[2] Now, however, the situation is different. The global economy is changing. New technologies are transforming production processes, which in turn impact business and consumer behaviour. Industrial-based economies, such as those in the US and the EU, are increasingly transitioning towards a service-oriented economy, in which most of the value is generated from the production of services like ICT, healthcare, finance or cybersecurity. As new technological developments are increasingly dual use, some of these industries are becoming tied to national security concerns.

LAC has moved from being a passive supplier of raw materials to becoming an active node in advanced manufacturing. According to PwC, Mexico has become home to the leading global players of the A&D (aerospace and defence) industry,[3] using the country’s advantages in precision machinery, electric and power systems.[4] Mexico’s A&D supply chains are integrated with North America. Europe owns 30 per cent of the market share of the A&D industry, while North America captures 60 per cent. As Europe faces numerous economic security threats today, it should deepen its Atlantic ties. Yet it still fails to acknowledge Latin America as a fellow Atlantic actor.

In LAC, individual leadership often sets the tone for regional dynamics and the region’s place in the world. The return of strongmen may be a global trend, but it feels like a familiar pattern in LAC. This speaks to the deep roots of hyper-presidentialism across many CELAC countries, where power tends to concentrate in the executive and institutions remain fragile. In recent years,[5] elections have increasingly become a vehicle for protesting against the incumbent rather than casting an ideological choice: voters punish those in power instead of rallying behind a vision. The consequence is a cycle of discontinuity, where each new leader seeks to erase their predecessor’s legacy. Strikingly, this same impulse is beginning to echo beyond the region, even in the United States.

The new Trump disruptive mandate has transformed the transatlantic trade and economic relations, which impact the configuration of regional alliances in the Western Hemisphere. These circumstances make it more likely that several leaders—among them Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico, Gabriel Boric of Chile, and Peru’s new President Jose Jeri,[6] who is facing a political crisis will judge that their absence from the summit better serves their interests. Such decisions would significantly increase the risk of a diplomatic failure. Then, the real stress test of the summit may not be who attends, but how to handle the moment when your headline guests skip the party altogether.

If the Santa Marta summit is to avoid becoming another missed opportunity, the EU must arrive with clear and deliverable priorities: a plan to deepen economic security cooperation, integrate regional value chains, close digital investment gaps, and complete the network of trade agreements that could transform EU–CELAC relations from polite dialogue to strategic partnership. For Ursula von der Leyen and António Costa, the chief priority should be to convince Latin American leaders that partnership with the EU is still a relevant and pragmatic response to their domestic challenges. To do that, Europe should move from promises to performance, translating its rhetoric on “shared values” into policies that deliver visible outcomes in trade, digital infrastructure, and supply-chain resilience.

[1] The EU has negotiated cooperation and economic agreements with 27 of the 33 countries in Latin America, making it the region with the broadest institutional links to the EU. The stock of FDI by the EU-27 in LAC is higher than the EU’s total investment in China, India, Japan and Russia (even before it invaded Ukraine).

[2] Scholars use the term “polycrisis” to describe a situation in which multiple crises—such as the financial crash, migration pressures, Brexit, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and now geopolitical and energy insecurity—occur simultaneously and interact in ways that amplify one another.

[3] PwC (2015) Aerospace Industry in Mexico. Retrieved from: https://www.ivemsa.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PWC-2015-06-04-aerospace-industry.pdf

[4] Luna, J. et al (2018) Assessment of an emerging aerospace manufacturing cluster and its dependence on the mature global clusters. Procedia Manufacturing (19) 26-33. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351978918300052

[5] In the early 2000s a phenomenon known as the pink tide, in which most South American countries were governed by the left-leaning leaders. With the election of Amlo, Boric, Petro, Castillo and Lula, many analysts prompted in drawing a parallelism with the first pink tide. However, this is a misinterpretation of the anti-incumbent vote that dominates the trend. The only colour of this year’s tide is not pink but Maga red flowing from the north.

[6] Peru finds itself once again at the heart of political turbulence: Congress removed President Dina Boluarte in October 2025 for “moral incapacity,” after months of deep unpopularity, corruption scandals, and growing insecurity. José Jeri, the head of Congress, stepped in as interim president while protests erupted nationwide. Boluarte had herself taken power in 2022 following the downfall of Pedro Castillo, who was impeached and imprisoned after trying to dissolve Congress in an attempted self-coup.

2. Lessons From the Past

This is the historical stage on which the summit in Santa Marta is set to take place. Since its first meeting in 2013, the EU–CELAC partnership has sought to institutionalise the long-standing dialogue between Europe and Latin America under a single bi-regional framework. However, the record of the last decade shows a recurring pattern: summit declarations with ambitious priorities, but limited implementation.

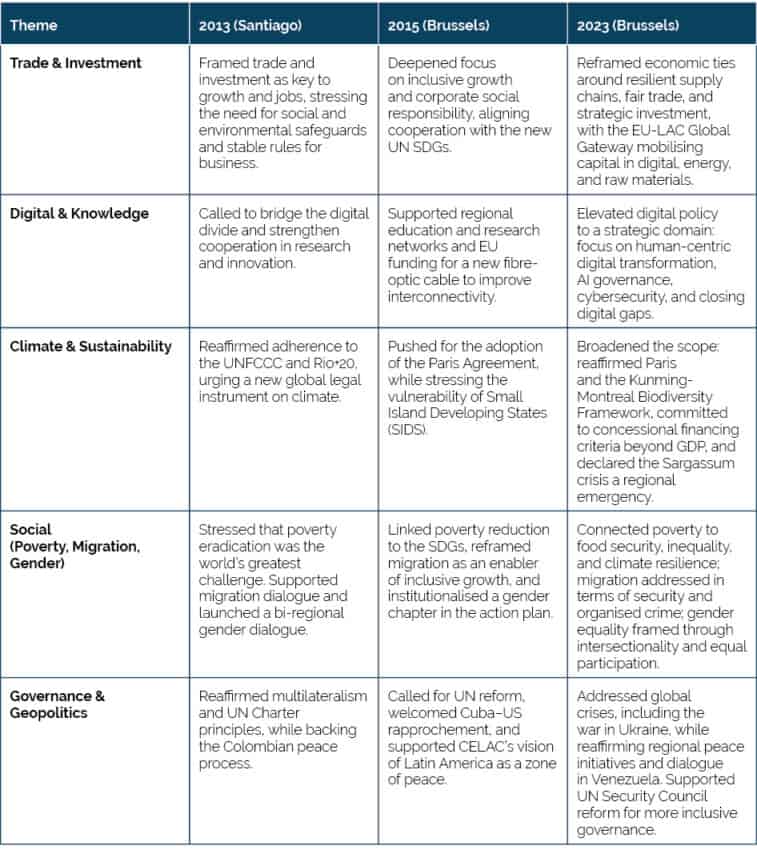

The stated priorities and focus areas of the EU-CELAC partnership have evolved over the years, as shown in Table 1. The 2013 Santiago Declaration stressed investment, innovation, and social cohesion. The 2015 Brussels Declaration shifted toward inclusive growth, climate action, and citizen security. These first summits were framed around development-oriented cooperation. The 2023 Brussels Summit revived the partnership with an emphasis on green and digital transitions, economic security, and supply chain resilience.

Table 1: Evolution of the strategic priorities of the EU-CELAC At the same time, it is equally revealing to examine which issues have been dropped or deemphasised over time. These omissions also shed light on how EU-CELAC priorities have shifted in response to the global and domestic contexts. Earlier declarations reflected a moment when both regions were deeply interested in the multilateral agenda following the 2008 financial crisis, expressing commitments to financial and trade negotiations. Similarly, the 2013 and 2015 declarations explicitly called for an “ambitious, comprehensive and balanced” conclusion of the Doha Round. By contrast, the 2023 declaration adopts a more strategic tone, pivoting toward economic security, digital transformation and geopolitical autonomy.

At the same time, it is equally revealing to examine which issues have been dropped or deemphasised over time. These omissions also shed light on how EU-CELAC priorities have shifted in response to the global and domestic contexts. Earlier declarations reflected a moment when both regions were deeply interested in the multilateral agenda following the 2008 financial crisis, expressing commitments to financial and trade negotiations. Similarly, the 2013 and 2015 declarations explicitly called for an “ambitious, comprehensive and balanced” conclusion of the Doha Round. By contrast, the 2023 declaration adopts a more strategic tone, pivoting toward economic security, digital transformation and geopolitical autonomy.

The past decade of EU–CELAC relations reveals a striking lesson: comprehensive declarations and institutional trade links do not build strong partnerships on their own. Each summit has updated the vocabulary of cooperation, from social cohesion and sustainable growth to digital and green transitions, but the instruments to deliver on those ambitions have not always matched the scale of expectations. While association and trade agreements have created a dense institutional framework, their potential remains underused, often constrained by fragmented coordination, limited follow-up, and fluctuating political commitment on both sides.

3. Bringing Words Into Action

What should von der Leyen and Costa prioritise for the summit? Turning commitments into action requires aligning incentives, budgets, and institutions on both sides of the Atlantic. The following recommendations outline priorities and concrete steps to make the EU–CELAC partnership not just aspirational, but actionable—anchoring it in shared economic security, deeper value-chain integration, and a renewed commitment to a rules-based international trade order.

A) Deepen EU-CELAC economic security cooperation to mitigate supply chain shocks and the weaponisation of economic dependencies through trade diversification. Both regions should prioritise a structured agenda that strengthens resilience to external shocks and reduces vulnerability to geopolitical coercion. For example, one initiative that could be implemented is to create a joint EU-CELAC Economic and Supply Chain Resilience Task Force assigned with identifying vulnerabilities and bottlenecks in logistics, trade facilitation and customs harmonisation. Diversifying shipping routes and establishing “resilience hubs” within multimodal logistics systems can help both anticipate shocks and reduce overdependence on a limited number of transatlantic corridors. The A.P. Moller-Maersk and Hapag-Lloyd Gemini Initiative,[1] launched in early 2025, was built to enhance resilience against geopolitical instability. Traditional shipping networks rely on fixed routes, whereas Gemini was designed to concentrate operations around targeted hubs, enabling quick pivots to minimise disruption risk. This model could be replicated in establishing a limited number of Atlantic ports in Santos, Brazil; Cartagena, Colombia; Cristobal, Panama; or Veracruz, Mexico.

The EU-CELAC Economic and Supply Chain Resilience dialogue could be further organised into working groups that address international trade operations targeted to strategic sectors such as energy, critical raw materials and high-tech manufactures. Supplier-mapping initiatives can help companies identify alternative suppliers in these critical sectors. In the 2023 EU Critical Raw Material assessment, China is both the largest global supplier to the EU and the world of CRMs such as rare earths, gallium, magnesium, etc. In Latin America, Chile and Argentina are the largest suppliers of Lithium,[2] and Mexico is the leading supplier of fluorspar.[3] However, this assessment only considers the extraction of these minerals, i.e. mining. In practice, China dominates nearly every stage of the value chain—from extraction and refining to component manufacturing.[4] For this reason, Europe should move beyond a narrowly extractivist approach that views Latin America mainly as a provider of raw materials: a forward-looking EU–CELAC agenda should focus instead on developing regional research clusters, processing capacities, and innovation networks that enable Latin American countries to retain a greater share of value within strategic supply chains. Targeted investment in technology transfer, industrial upgrading, and joint scientific projects would not only reflect the EU’s own sustainable development commitments but also contribute to diversifying its global partners.

B) Promote the integration of regional value chains and foster diversified comparative advantages across CELAC countries, enabling more specialisation. One of the persistent impediments to development in Latin America and the Caribbean is the region’s low level of economic integration. Despite decades of dialogue and trade integration in LAC, intra-regional trade accounts for approximately 14% of total exports, with limited progress in recent years remaining[5] far lower than in Asia or Europe—reflecting political fragmentation, uneven infrastructure, and institutional weaknesses. Most CELAC economies remain structured around the export of primary goods, limiting their capacity to move up the value chain and exposing them to external shocks.

The EU–CELAC cooperation should help to diversify production and trade in the region. Practical initiatives might include supporting lithium processing and battery component manufacturing in the Southern Cone, developing semiconductor testing and packaging hubs in Brazil and Costa Rica, or linking Mexico’s aerospace industry with suppliers in the Andes. By fostering such differentiated specialisation, CELAC could evolve from a collection of commodity-based economies into an integrated economy that attracts European investment and generates higher value-added growth and jobs across the region.[6] Strengthening regional capabilities would make both partners less vulnerable to external shocks and build a genuinely strategic, long-term economic partnership.

C) Utilise the EU-LAC Global Gateway Investment Agenda to plug investment gaps, specifically in digital transformation. The EU–LAC Global Gateway Investment Agenda sometimes reads like a letter to Santa Claus—filled with ambitious requests that far exceed its limited budget. Latin America and the Caribbean, in fact, receive the smallest regional allocation within the program, even though digital transformation is one of the most pressing areas for cooperation. To be credible, the EU must expand and strategically orient the Global Gateway’s resources toward projects that enhance connectivity. This means prioritising the rollout of secure broadband networks, data centres, and digital infrastructure that support regional integration and facilitate the free flow of information between the EU and CELAC. A strengthened digital pillar within the Global Gateway would thus serve a dual purpose: reducing Latin America’s digital divide while advancing a rules-based, secure, and interoperable digital partnership.

Building on flagship projects such as BELLA II or the EU-LAC Digital Alliance, which aims to expand the transatlantic fibre-optic cable connecting Europe with Latin America, the Global Gateway could support the development of intra-regional digital corridors and local data centres. Currently, BELLA II is funded with just €13 million from the EU, plus a matching co-investment.[7] The wider EU-LAC Digital Alliance has an initial EU budget of about €50 million out of a €145 million Team Europe pledge;[8] the scale is small relative to the digital needs of the region. Even the European Investment Bank’s 15 Global Gateway contracts signed since 2022 total €1.7 billion,[9] which is modest compared to what is needed for digital connectivity, broadband infrastructure, and data centres across LAC. By investing in infrastructure, standards, and research, the EU can help Latin America leap forward technologically, while anchoring a shared digital space that reflects democratic values and reduces dependence on non-like-minded tech providers.

Digital connectivity is also about trust, interoperability, and data standards. Ensuring that data transfers between both regions are secure and consistent with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) should be a cornerstone of this cooperation. Currently, Argentina remains the only country in Latin America formally granted “adequacy status” by the European Commission,[10] meaning its data protection regime is considered equivalent to EU standards. Extending regulatory cooperation and technical assistance to help other CELAC countries move toward similar recognition would create a trusted digital ecosystem capable of supporting e-commerce, fintech, and public services across borders.

D) Finish trade agreements and their implementation. The EU’s trade links with Latin America and the Caribbean remain one of its most underleveraged geopolitical assets. While the EU has signed association and trade agreements with 27 of the 33 CELAC countries, many of these agreements remain only partially implemented or await full ratification. Completing and modernising these agreements, particularly with Mexico and Mercosur, is a strategic priority. The modernised EU–Mexico Global Agreement, for example, would open the Mexican procurement market to European firms at sub-federal government procurement. It also incorporates trade disciplines typically found in the EU’s most contemporary and comprehensive trade deals. This update also expands agricultural market access while protecting sensitive products—dairy for Mexico and beef and poultry for the EU. On intellectual property, the EU secured Mexico’s protection for over 500 European products in the Mexican market.[11]

Similarly, the EU-Mercosur Agreement would create a market of more than 700 million people and consolidate Europe’s access to key agri-food, industrial, and green transition inputs at a time when economic security is a priority. Mercosur provides the EU with a large and complementary market that supports Europe’s industrial, services, and agricultural exports, offering diversification beyond its traditional partners. EU firms hold over €2.6 trillion in investment stock across Mercosur, benefiting from expanding market access and strong returns in manufacturing, finance, and telecommunications.[12]

Trade between the EU and Mercosur is dominated by machinery, agriculture, chemicals, and crude materials. Yet, despite its modest scale, agriculture manages to occupy a disproportionately large space in Europe’s political imagination. In reality, Mercosur’s agricultural exports account for barely 3.5% of the EU’s total agricultural imports once intra-EU trade is considered[13]—a figure that hardly supports the alarmist rhetoric often heard in Brussels. Mercosur’s strategic value lies in its role as a partner in maintaining Europe’s global competitiveness and open strategic autonomy.

The alternative for the EU, relying only on purely domestic industrial policies to achieve diversification or resilience, is a fantasy. No amount of reshoring or EU funding can replicate the scale, consumer base, or strategic resources of external partners. The single market is rightly celebrated as one of Europe’s greatest achievements in the history of economic integration. But it is not a silver bullet. As the Letta Report underscores, the EU’s single market remains incomplete.[14] Its external dimension must therefore be recognised as the missing piece in the formula to strengthen the EU’s competitiveness and resilience. Implementing these agreements would deliver tangible benefits: diversified supply chains, enhanced market access for European firms, and greater regulatory convergence on sustainability and digital standards. For Latin America, these accords would translate into industrial upgrading, technology transfer, and access to stable and rules-based markets at a moment when many economies face high volatility and fragmented domestic policy environments. Beyond economics, each completed agreement represents a geopolitical source of strength, a must for anchoring Europe’s strategic presence in the region.

E) Make the EU-CELAC a springboard for a “Coalition of the Willing” for a rules-based international trade. The Santa Marta Summit is a timely opportunity for the EU and CELAC to springboard a “coalition of the willing” committed to defending a rules-based international trading system, as suggested in President von der Leyen State-of-the-Union speech in September. Both regions have a shared interest in reinforcing predictability, transparency, and legal certainty in global trade. This coalition should coordinate positions within the World Trade Organisation (WTO), expand on new mechanisms for dispute settlement, launch plurilateral initiatives on trade facilitation, digital commerce, and sustainability standards, and collectively push back against the erosion of multilateral trade norms.

The EU has already signalled its openness to engage more closely with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) — one of the few trade frameworks that continues to expand and modernise its rulebook. Several CELAC countries, including Mexico, Chile, and Peru, are full CPTPP members, placing the region at the crossroads of two major trade governance spaces. Forming such a coalition would not only protect the integrity of open trade but also allow both regions to shape the rules of the future economy—those that will govern the flow of data, green goods, and critical technologies by the end of the century, not merely today’s tariff irrational schedules. By aligning on the principles of openness, sustainability, and fairness, a renewed EU–CELAC partnership could ensure that international trade remains a source of stability, prosperity, and shared progress.

[1] A.P. Moller – Maersk. (2025). The Maersk East-West Network. Retrieved from: https://www.maersk.com/east-west-network

[2] Chile and Argentina own the 14 and 8 per cent, respectively, of the market share in lithium production. See: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/document/download/a5a7b598-6542-42c3-9b32-ba98b6a959f8_en

[3]Fojtíkova, L. et. al (2025) Determinants of critical raw material imports: The case of the European Union and China. Mineral economics. doi.org/10.1007/s13563-025-00528-4. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13563-025-00528-4

[4] Joint Research Centre. (2023, March 16). Solutions for a resilient EU raw materials supply chain. European Commission. Retrieved from: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/solutions-resilient-eu-raw-materials-supply-chain-2023-03-16_en

[5] Giordano, P., & Michalczewsky, K. (2024). Trade Trends Estimates: Latin America and the Caribbean – 2024 Edition. Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0005513

[6] Ibid

[7] BELLA Programme. (2022, December). BELLA II. Retrieved from: https://bella-programme.eu/index.php/en/about-bella/bella-ii

[8] European Commission. (2023, March 16). Global Gateway: EU, Latin America and Caribbean partners launch in Colombia the EU-LAC Digital Alliance. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Retrieved from: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/global-gateway-eu-latin-america-and-caribbean-partners-launch-colombia-eu-lac-digital-alliance

[9] European Investment Bank. (2023, July 14). The Global Gateway in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/2023-0171-the-global-gateway-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-en.pdf

[10] Erixon, F., Lamprecht P., van der Marel, E., Sisto, E. Zilli, R. (2024) The Extraterritorial Impact of the EU Digital Regulations: How can the EU minimise Adverse Effects for the Neighborhood? Retrieved from: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/the-extraterritorial-impact-of-eu-digital-regulations-how-can-the-eu-minimise-adverse-effects-for-the-neighbourhood

[11] The discussion on the challenges of negotiating with the European Union is drawn from the comments of César Guerra, who served as chief negotiator for the modernisation of the agreement between Mexico and the European Union. The full transcript for the podcast episode, Mexico between the United States and Europe: Trade Challenges and Opportunities (Episode 1) from the series Sin Arancel de Por Medio, is available from the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) (2025) at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/SAdpM-1-EN-Transcript_2.pdf

[12] Guinea, O., & Sharma, V. (2021). EU and Mercosur in the Twenty-First Century: Taking Stock of the Economic and Cultural Ties (Policy Brief No. 15/2021). European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). Retrieved from: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ECI_21_PolicyBrief_15_2021_LY01.pdf

[13] Ibid

[14] Letta, E. (2024). Much more than a market: Speed, security, solidarity—Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU citizens. European Union. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/ny3j24sm/much-more-than-a-market-report-by-enrico-letta.pdf

References

A.P. Moller – Maersk. (2025). The Maersk East-West Network. Retrieved from: https://www.maersk.com/east-west-network

BELLA Programme. (2022, December). BELLA II. Retrieved from: https://bella-programme.eu/index.php/en/about-bella/bella-ii

Borrell, J. (2025). Foreword. In J. A. Sanahuja & R. Domínguez (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of EU-Latin American relations (pp. v–xi). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-80216-4

European Commission. (2023, March 16). Global Gateway: EU, Latin America and Caribbean partners launch in Colombia the EU-LAC Digital Alliance. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Retrieved from: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/global-gateway-eu-latin-america-and-caribbean-partners-launch-colombia-eu-lac-digital-alliance

European Investment Bank. (2023, July 14). The Global Gateway in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/2023-0171-the-global-gateway-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-en.pdf

Erixon, F. et al (2024) Trading up: An EU Trade Policy for Better Market Access and Resilient Sourcing. European Centre for International Political Economy. Retrieved from: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_08-2024_LY05.pdf

Erixon, F., Lamprecht, P., van der Marel, E., Sisto, E., Zilli, R. (2024). The Extraterritorial Impact of the EU Digital Regulations: How can the EU minimise Adverse Effects for the Neighbourhood? Retrieved from: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/the-extraterritorial-impact-of-eu-digital-regulations-how-can-the-eu-minimise-adverse-effects-for-the-neighbourhood

Fojtíkova, L. et. al (2025). Determinants of critical raw material imports: The case of the European Union and China. Mineral economics. doi.org/10.1007/s13563-025-00528-4. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13563-025-00528-4

Global Trade Alert (Sept 2025). Relative Trump Tariff Advantage Chart Book. Retrieved from: https://globaltradealert.org/reports/Relative-Trump-Tariff-Advantage-Chart-Book

Giordano, P., & Michalczewsky, K. (2024). Trade Trends Estimates: Latin America and the Caribbean – 2024 Edition. Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0005513

Guinea, O., & Sharma, V. (2021). EU and Mercosur in the Twenty-First Century: Taking Stock of the Economic and Cultural Ties (Policy Brief No. 15/2021). European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). Retrieved from: https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ECI_21_PolicyBrief_15_2021_LY01.pdf

Joint Research Centre. (2023, March 16). Solutions for a resilient EU raw materials supply chain. European Commission. Retrieved from https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/solutions-resilient-eu-raw-materials-supply-chain-2023-03-16_en

Letta, E. (2024). Much more than a market: Speed, security, solidarity—Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU citizens. European Union. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/ny3j24sm/much-more-than-a-market-report-by-enrico-letta.pdf

Luna, J. et al (2018). Assessment of an emerging aerospace manufacturing cluster and its dependence on the mature global clusters. Procedia Manufacturing (19) 26-33. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351978918300052

Morales, C. (2025) Dos nuevas encuestas revelan el nivel de aprobación de Gustavo Petro en Colombia: los resultados muestran la cruda realidad. Retrieved from: https://colombia.as.com/actualidad/dos-nuevas-encuestas-revelan-el-nivel-de-aprobacion-de-gustavo-petro-en-colombia-los-resultados-muestran-la-cruda-realidad-n/

PwC (2015) Aerospace Industry in Mexico. Available at: https://www.ivemsa.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PWC-2015-06-04-aerospace-industry.pdf

Ríos Méndez, G. & Rodríguez Pinzón, E. (2025). Latin America and the Caribbean-European Union Relations: Strengthening a Strategic Alliance. Fundación Carolina and IE University Global Policy Centre. Retrieved from: https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/ESPECIAL-IE_UNIVERSITY_eng.pdf