India and the World Economy: Policy Options at a Time of Geopolitical Drama, Technological Shifts, and Rising Protectionism

Published By: Fredrik Erixon Dyuti Pandya Vanika Sharma

Subjects: South Asia & Oceania

Summary

What trade policy should India pursue? Geopolitical drama and a faltering multilateral system have made choices of trade policy harder for many countries. Rising protectionism, economic nationalism, and growing scepticism towards globalisation eat into most trade relations. Technology-driven innovation and rapid changes in the composition of trade have added additional layers of complexity, forcing governments to develop new policies for cross-border economic integration. This is the inflection point for India’s trade policy: its traditional approach is increasingly unable to respond to new economic and political realities, and new approaches may be needed to deliver better economic outcomes.

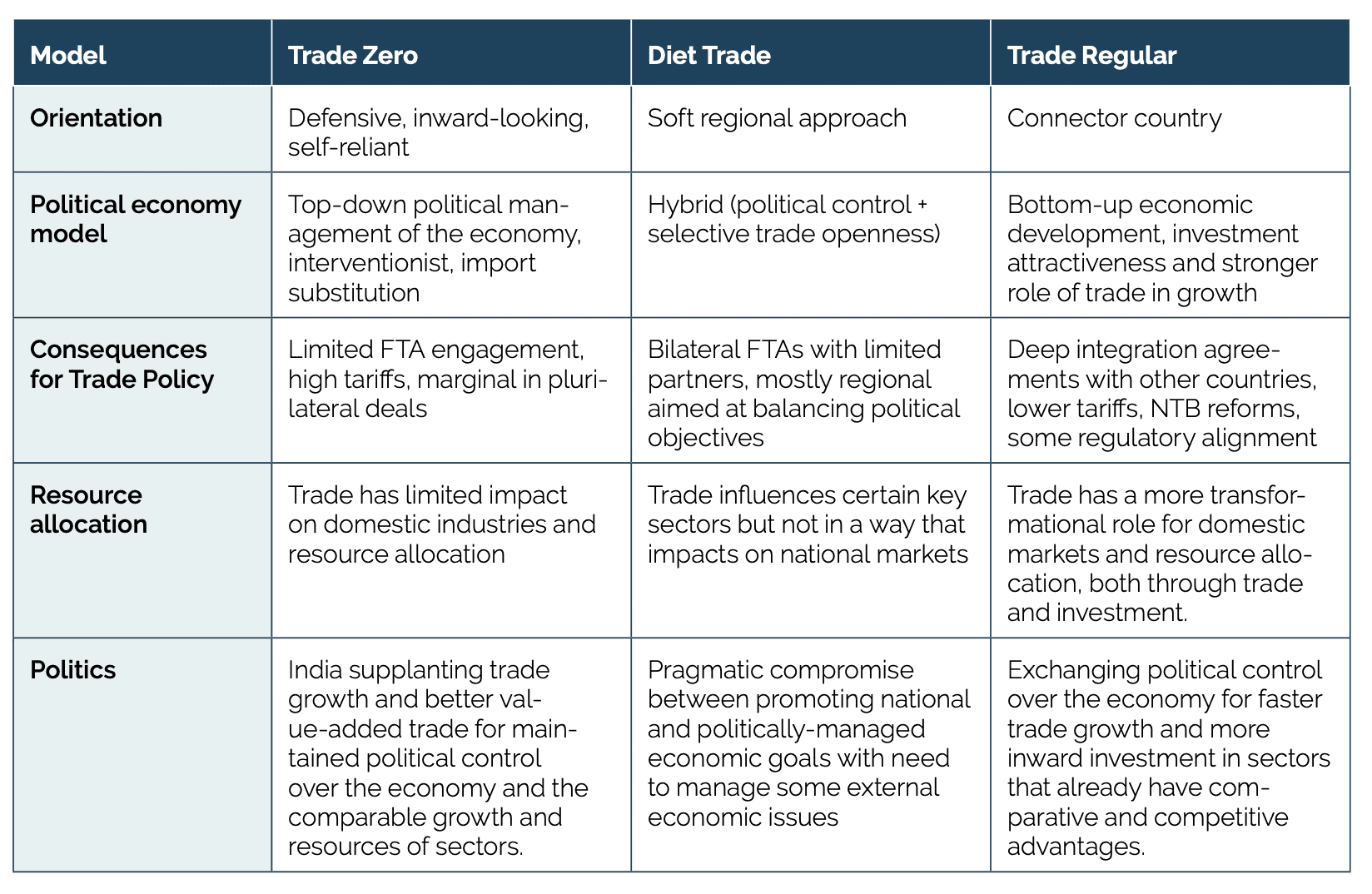

Using India’s external trade strategy as a starting point, this policy brief presents three strategic options for India, each reflecting varying degrees of trade openness as a means to drive economic development. Using categories from the world of soft drinks, we call them “Trade Zero”, Diet Trade” and “Trade Regular”.

First, the Trade Zero approach allows India to maintain its defensive stance on trade, focusing primarily on the growth of its domestic market and demand. Trade only serves as a means to manage production surpluses. Second, the Diet Trade approach pushes India to softly enhance trade with its already well-established trading partners, ideally by focusing on high-value-added goods and services. The model emphasises deepening diplomatic relations through trade: however, not at the cost of domestic policy priorities. And lastly, the Trade Regular approach encourages the adoption of a more ambitious trade strategy with the aim of establishing India as a central hub connecting major global economic regions. This would happen through upgrading existing trade agreements, signing new multilateral trade agreements, as well as adopting significant domestic reforms for further economic liberalisation.

India’s trade performance provides the actual context of the realities of India’s trade policy. There are some notable features in India’s trade performance: its trade sector is small (international trade as a share of the GDP); it has a large services export sector compared to the export of goods; exports of high-value added goods and services has increased substantially; there is a consistently large share of big economies such as the United States and the European Union in India’s exports. All these features point to India’s position in global trade as a relatively high-value added economy.

India, therefore, not only has an opportunity to leverage its trade capacity to significantly improve economic growth but can also adapt to newer forms of trade and increasingly engage with the global economy. Moreover, given the shifting global context and the increasing trade reciprocity demands from larger economies, India will also need to strengthen its trade relations with a diverse set of partners.

In a way, India’s economy has already made the choice of which model that suits it best. Given the key features of the country’s trade sector, India’s real economy is already moving towards a Trade Regular model. However, there is a gap between the actual performance and policy positions, which remain defensive. Future trade growth, however, will likely depend on India becoming more pro-active in its trade policy and better equipped to negotiate trade agreements that respond the ambitions of its outward-oriented companies.

1. Introduction

World trade policy has changed a lot in the past ten years. Until a decade ago, the underlying assumption in most countries was that international exchange would continue its path of gradual liberalisation, even if some efforts to that end had proven difficult.[1] Fundamentally, major economies like the US were still willing to tolerate non-reciprocal trade relations and unequal rates of growth in exports. Multilateral frameworks under the WTO facilitated this by emphasising developing-country exceptions and a philosophy that accommodated the desire to encourage economic development and poverty reduction through trade and economic modernisation.

By contrast, today’s trade environment features rising protectionism, economic nationalism, and growing scepticism towards globalisation. Security threats have also become reflected in various policies on global commerce and they have exacerbated the trend towards a managed approach to trade and less emphasis on the principles of most-favoured nation (MFN) and non-discrimination. The whole WTO system has hit a roadblock and we may be at the cusp of a fundamental re-orientation of America’s commercial relations with the world. Trade policy is no longer seen as a general tool for development but has become conditioned on the role of trade for building security and resilience, and for promoting advantaged sectors – sometimes even privileged firms.

Then there is the structural change of trade, happening on the back of broader technological developments that impact heavily on the relative tradability and competitiveness of sectors. While growth in trade in goods has stagnated since 2010, technological shifts have allowed for new types of cross-border commerce – a development which, paradoxically, has strengthened in parallel to rising protectionism. This means that the composition of global trade is also undergoing a significant shift, leading countries to reevaluate their priorities for trade policy. While traditional trade focused on the export of goods, newer forms of trade are increasingly centred on services, e-commerce, and intangible assets such as intellectual property (IP), research and development (R&D), and organisational capital. This is a development which offers huge opportunities for companies and countries alike – if they can arrange their policies in adequate ways.

Where does India find itself in this world of turbulent global commercial policy and structural changes to international trade? For sure, India stands at a critical juncture in its economic development. It is a rising economic power and its own process of economic modernisation entails substantially more economic contact with the outside world. An increasing number of Indian companies have sales to customers in other countries. Indian firms such as Tata, Mahindra, Infosys, HCL, Wipro, and Airtel have made their mark in global markets.[2] Additionally, state-owned companies like Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL), Maharatnas and Navratnas are also increasingly expanding their international presence.[3] More and more firms are also plugged into global production and development networks that provide new impulses of economic globalisation. It’s clear that the country’s trade profile has changed because of economic modernisation and technology. However, the new patterns of economic output have only affected internal and external economic policies up to a point.

Historically, India has been taking defensive negotiation positions in international trade talks, reflecting a general hesitant approach to external trade and further exposing its economy to foreign competition. Under the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) and later the WTO (World Trade Organisation) framework, India claimed special and differential (S&D) treatment, allowing it to maintain a more protectionist stance while principally getting improved market access to other economies, an approach it is unwilling to relinquish.

Two key goals are driving India’s external trade approach. One is its opposition to plurilateral agreements, which allows India to preserve its own policy space and protective measures while avoiding commitments to higher standards.[4] For instance, under the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, India has delayed joining the trade pillar as a direct result of domestic concerns related to India’s economic sovereignty and democratic processes.[5] Similarly, in 2023, India strongly opposed the Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) Agreement at the World Trade Organisation, which aimed at improving transparency and governance in domestic investment processes to foster a favourable investment climate and attract foreign direct investment (FDI).[6]

Second, by aligning itself with developing countries, despite not fully sharing their challenges,[7] India maintains its influence in trade negotiations and retains its autonomy in shaping its own domestic policies. For instance, in 2019, the US proposed restricting Special & Differential Treatment (S&D) eligibility based on economic criteria, which would have made India ineligible, but India put forth strong resistance claiming longstanding treaty rights and existing development disparities.[8] This defensive stance reflects a broader pattern in India’s trade policy, which has often been reactive and misaligned with its own stated objectives or its long-term interests. Ultimately, this posture has made it less competitive in securing market access and adapting to the norms of international trade.

However, economic and political realities have changed – both in India and in its key trading partners. With the WTO’s negotiation framework becoming increasingly dysfunctional, countries have turned to bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs) – an area where India has been less active than many other countries. As of 2025, India has signed 13 FTAs and 6 preferential trade pacts. And when it has been active, it has struggled to secure favourable terms[9] – principally because the reciprocal, like-for-like nature of bilateral trade deals has been sitting awkwardly within New Delhi’s traditional trade philosophy. Nor have regional trade agreements, with their ambitions to encourage the growth of regional production networks and supply chains, been seen as attractive.

The trade opportunities that are presenting themselves in this new era of trade policy often seem unappealing to India because they require a different policy attitude. Worse, they are not reflecting the opportunities presented in the past, when some emerging economies could aim for an export-led model of economic growth. Unlike earlier periods when defensive stances on domestic market openness could be accommodated, India now faces a trade environment where openness, reciprocity, and deeper economic integration are necessary to gain market access.

This is the starting point for this Policy Brief. Given developments in global markets – and in India’s domestic market too – it is natural to ask: does India need to rethink its trade strategy to promote economic growth and reach its global ambitions or can it sustain itself based on the current trajectory? If a rethink is needed, what are the strategic options available to India? This Policy Brief highlights three strategic options for India’s external trade policy going forward which align with India’s ambitions to position itself as a global economic power. Using categories from the world of soft drinks, we call them “Trade Zero”, “Diet Trade” and “Trade Regular”.

This Policy Brief is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines three potential models for India’s trade strategy, offering distinct approaches to navigating the evolving trade landscape. Section 3 provides an analytical assessment, examining the practical realities of India’s trade landscape and the necessary steps for progress. Section 4 concludes the Policy Brief.

[1] Even if the Doha Round in the World Trade Organisation had lost impetus and direction, it was largely believed that new efforts could rejuvenate trade multilateralism.

[2] Tata International operates in 100 countries across China, the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa, Europe, and North America. See: Tata. Available at: https://www.tata.com/tata-worldwide; Mahindra Group has a presence in 100 countries spanning the Americas, Europe, Asia-Pacific, Africa, and the Middle East. See: Mahindra. Available at: https://www.mahindra.com/our-businesses/global-presence; As of 2023, Infosys operates in 56 countries across the Americas, Asia-Pacific, Europe, the Middle East, and South Africa. See: Infosys. (2023). Navigating change. Available at: https://www.infosys.com/investors/reports-filings/documents/global-presence2023.pdf; HCL Tech has a presence in 60 countries and is expanding in Eastern Europe and Central America, based on the latest available information. HCLTech. Available at: https://www.hcltech.com/global-presence ; Wipro’s WIN has manufacturing facilities in India, Northern and Eastern Europe, the US, Brazil, and China. See: Wipro. Available at: https://www.wipro.com/about-us/wipro-group-companies/; Airtel operates in 22 countries across Africa, Asia-Pacific, the UK, France, and the US. See: Airtel. Available at: https://www.airtel.com/

[3] FDI Intelligence. (2024). India Inc flexes muscles on global stage. Available at: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/291e6421-fc21-52f3-807c-5ccb55a1ae63

[4] Manak. I. (2025). How India Disrupts and Navigates the WTO. Council for Foreign Relations. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/article/how-india-disrupts-and-navigates-wto

[5] CSO Letter to the Commerce Minister on the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and India joining the trade pillar. Available at: https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPEF_Letter-to-MoC_May-26-1.pdf

[6] WTO. (2023, December 21). Statement By India On Agenda Item 18 General Council Meeting – 13 – 15 December 2023. WT/GC/262. Available at: https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/262.pdf&Open=True

[7] Manak. I. (2025). (see note: 4)

[8] The Continued Relevance of Special and Differential Treatment in Favour of Developing Members to Promote Development and Ensure Inclusiveness: Communication from China, India, South Africa, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Plurinational State of Bolivia, Kenya, Cuba, Central African Republic and Pakistan,” World Trade Organization, WT/GC/W/765/Rev. 2, March 4, 2019. Also see: Strengthening the WTO to Promote Development and Inclusivity: Communication from Plurinational State of Bolivia, Cuba, Ecuador, India, Malawi, Oman, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda and Zimbabwe,” World Trade Organization, WT/GC/W/778/Rev.1, July 22, 2019.

[9] This is reflected in India’s prolonged trade negotiations with the EU, UK, Canada, and Oman, alongside its stalled efforts to secure a comprehensive FTA with the US and subsequent talks to pursue a managed trade agreement as an alternative.

2. Three Models of Trade for India: Structures and Potential Outcomes

We have sketched three principle options for India’s approach to the global economy. They all take aim at broad political and political economy features of trade policy: features that will shape different types of outcomes for the economy and in the space of national economic management. Just as other countries have realised in the past when they made a choice about how they want to engage with the world economy amid a phase of economic catch-up, the available choices are limited. The interesting aspect of available choices is often how they shape the relative performance of different sectors and different factors of production. For an economy that traditionally traded a lot in commodities, food, and textile products, India has rapidly grown into a services trade powerhouse. Now, through domestic programs and policies, it is attempting to engineer a new wave of industrialisation and the growth of home-controlled manufacturing firms, with consequences for its trade performance.

However, India’s policy choice may be even more limited, given the pre-dominance of trade philosophies and practices that require reciprocal trade, sometimes artificially focused on a balance in trade volumes within sectors. Thus, the choices have consequences for the balance between the internal and the external economic sector in India, and which of them that carry most impact on political decision-making. Still, all three models offer Indian policymakers a framework for thinking and addressing different challenges in India’s trade policy. Each strategy reflects varying degrees of trade openness and provides different perspectives on the role of trade as an instrument for achieving India’s economic development (Table 1).

The first model is “Trade Zero” and it basically represents status quo: India is not going to make any significant change to its trade policy but attempt to boost its exports through domestic economic policy that impacts what India can export and what it needs to import. The second model is “Diet Trade” and it includes a soft regional approach, representing a calibrated engagement with selected trade partners. The third model is based on a “Connector Country” approach: we call it “Trade Regular”. It is based on an ambitious approach to grow faster through international trade and allow the global economy to have a larger impact on India’s markets and how economic resources are allocated. It includes more ambitious trade agreements, especially with its key trading partners, that reduces trade costs and barriers. Philosophically, it builds on the regular economics of trade: trade performance is a result of natural economic factors and choices, with internal and external economic policies being united.

Table 1: Comparative Trade Policy Approaches for India

Model 1: Trade Zero

This model contains: Maintained domestic economic focus, prioritises self-reliance, trade as an avenue for surplus domestic production, little impetus to negotiate trade and investment agreements.

The first policy choice for India is Trade Zero – a status quo approach. India retains its defensive stance on trade, prioritising production for domestic demand. Trade policy remains subservient to what broadly is a state-led development model focused on domestic industrial growth, narrowly defined national interests, and cautious engagement with global markets. India maintains the ambition to grow the political management of sectors and patterns of economic growth.

The Trade Zero model also points to an increased focus on the growth of domestic industries. Trade negotiations are viewed through two broad domestic policy lenses: the Modi administration’s industrial policy, which seeks to attract global manufacturing away from China, and Atmanirbhar Bharat, which aims to foster domestic production through subsidies. Under this framework, the government has introduced several programs to promote domestic industries. For instance, in 2017, followed by an update in 2019, the Indian government introduced the Domestically Manufactured Iron & Steel Products (DMI&SP) policy to prioritise domestically manufactured iron and steel products in government procurement.[1] In 2019, the government launched the National Policy on Electronics (NPE) to boost domestic electronics manufacturing and exports.[2] Additionally, in 2020, the government implemented the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes targeting 14 critical sectors to strengthen manufacturing capabilities, drive technological innovation, and enhance India’s competitiveness in global markets.

In this scenario, India remains cautious about signing new trade agreements. In line with its old agreements, New Delhi actively seeks to avoid binding commitments on sensitive issues, including those that are important for some of its outward-oriented sectors (e.g., digital trade, cross-border data flows). As a result, Trade Zero implies no change to India’s tariff policies. Generally, India has comparatively high tariffs: the average tariff, according to the latest WTO review, was 14.3 percent (a bit higher if ad valorem equivalents are considered). The share of the tariffs that are above 10 percent and above 30 percent remains substantial and have further increased between 2014/15 and 2020.[3] Thus, in this model India retains higher protection against imports and inward investment. This approach, therefore, results in no significant resolutions to India’s long standing domestic challenges that are affecting trade, including weak enforcement of laws, arbitrary decision-making, and the protection of domestic incumbents. It also reflects a continued reluctance to engage in deeper bilateral and regional trade agreements and investment treaties.

Model 2: Diet Trade

This model contains: Incremental trade expansion with existing partners while prioritising regional markets and having some moderate ambitions for growing value-added trade. Remaining avoidance of big and comprehensive agreements that necessitate policy overhauls, instead opting for a gradual, selective approach to market openness. Maintains a stable investment regime with minimal structural changes.

The second policy choice for India is Diet Trade which builds on a soft regional trade approach, emphasising broader engagement with regional partners while continuing to maintain trade relations with established markets like the US and the EU. This model focuses on gradual but moderate trade expansion, particularly with smaller but high-growth economies. It also encourages growth in higher-value-added goods, services, and intangibles rather than relying on commodity exports. The approach emphasises strategic diversification, ensuring that India’s trade partnerships are spread across multiple regions, reducing dependency on any single bloc.

Rather than making trade a key driver of economic growth, this approach views trade as a tool for non-economic objectives (e.g., strengthening diplomatic ties) while advancing domestic economic goals. The model encourages trade deals but only insofar as they are selective and flexible, and does not reduce India’s own policy space much. Such trade deals are predominantly tailored to specific sectors and countries.

The soft regional trade model does not push for deep liberalisation but instead decides to selectively lower trade barriers to facilitate economic engagement with strategic partners. Although India’s recent trade agreements demonstrate its ambition to expand economic influence, they remain limited in scope, focusing on traditional exports while falling short of fostering deeper integration into high-value global value chains.[4] Depending on whom to provide market access to, India may also consider reducing tariffs on intermediate goods to promote integration into regional supply chains without fully opening up domestic markets.

Unlike a fully liberalised market, this approach does not involve major shifts in India’s domestic economic structure. The government retains its focus on domestic manufacturing for growth, ensuring that trade expansion aligns with national economic goals. Policies remain responsive rather than transformational, allowing for gradual adjustments to changing global conditions.

The economic benefits from trade are seen as positive spillovers rather than being part of the core objective. This choice employs policies that are responsive to both changing conditions and past mistakes. In 2020, for instance, Prime Minister Modi acknowledged this need, proposing the reshaping of global supply chains based on trust and stability rather than, in his view, solely on cost-benefit frameworks.[5] This aligns with India’s preference for managed trade expansion rather than fully integrating into global trade frameworks that might require significant domestic policy shifts.

A key aspect of this trade model is maintaining the competitiveness of India’s domestic industries while expanding trade relationships. Through this approach, India aims to develop its own regional production networks and strengthen its position in global trade. India’s major conglomerates along with numerous state owned and private companies operating under initiatives like the Indian Development Economic Assistance Scheme (IDEAS), have already played a crucial role in expanding the country’s presence in Africa. Industry bodies such as the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (Assocham), and Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) have also facilitated Indian businesses’ entry into African markets. In both Africa and South Asia[6], companies like KEC International Limited, Shapoorji Pallonji Group, Sterling & Wilson, and Afcons Infrastructure have been actively involved in major developments.[7] And in Latin America, Indian companies such as Glenmark, Zydus Cadila, Sun Pharma, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Pidilite Industries, ONGC Videsh Limited (OVL), NMDC Limited, TVS, Tata Motors, Infosys, and Wipro are actively expanding their presence in Brazil.[8]

Furthermore, utilising soft diplomacy, India can further tap into “South-South” trade opportunities[9], to engage with fast-growing economies seeking sustainable solutions. This strategy ensures that trade expansion remains aligned with national development goals, rather than being shaped by factors related to external competitiveness.

The Diet Trade model is a bargain between national policy space, on the one hand, and the use of India’s agency to shape rules and the terms of trade on the other hand. It is a pragmatic compromise between the protection of India’s own political-commercial model and the obvious need to manage external economic relations, including ensuring access to technology and new ideas. Favouring soft and selective trade engagements over deep integration with foreign markets, this model will limit India’s access to markets where firms from other countries can compete through stronger preferential agreements. While sector-specific trade deals offer short-term flexibility, they naturally hinder participation in global and complex value chains – leading to a trade profile based on pure sales of inputs or finished goods and services. A responsive rather than transformational trade policy means India can react to global and regional shifts but not shape trade rules that ultimately will affect India. Using trade as a diplomatic tool without deeper economic integration naturally weakens bargaining power, there is a limit to how much other countries would want to engage with India.

Model 3: Trade Regular

This model contains: India as a “connector country”; increasingly integrated in global value chains and having larger contribution to economic growth from trade. External markets (gtrade and investment) have a great role in driving India’s economic modernisation. Greater focus on engagement with liquid foreign markets with strong high-tech qualities. Acceptance of trade liberalisation – although not necessarily classic free trade – and reduced policy space through binding trade agreements.

The third model, Trade Regular, is a more ambitious trade approach which would expand the volumes of trade significantly and aim for more inward investment as India is positioned as a global hub. Linking Asia with other major economic regions – and leveraging its geographic, political, and demographic advantages – Trade Regular aims for India to be better integrated in global value and supply chains. Moreover, it focuses on expanding trade with major markets and significantly engaging in trade in high-value added sectors in a more integrated fashion compared to trade opportunities that emerge under the Diet Trade model.

Trade Regular requires upgrading existing trade agreements and signing new ones to increase reciprocal market access and align policies with emerging norms on trade in “new” areas (e.g., digital and ICT services) and sectors with opportunities to climb the value-added chain (e.g., pharmaceutical products, scientific services, machine technologies). In other words, India would have to accept deeper trade agreements with old and new partners; join mega-regional trade pacts, and promote more dense trade networks. Moreover, India would need to accept binding commitments on investment openness and protection, and in selected areas of regulation, reduce its policy space.

Obviously, this model – connector country – is partly rooted in geography, leveraging India’s strategic location to enhance trade connectivity with a wide range of partners. India’s export markets are already geographically diversified, reflecting its capacity to engage with and integrate into multiple regional and global trade networks. By becoming part of larger regional alliances, India can connect with broader geopolitical networks and move beyond limited integration.

Fundamentally, Trade Regular entails a shift in India’s growth strategy: natural market developments will have a greater influence over defined national goals on which sectors should grow. It basically means that India’s own comparative advantages and changes in global markets and trade will have a greater effect on how resources are used and allocated at home. In short, more investments and human capital will go into sectors with stronger comparative and competitive advantages. It follows that a key feature of Trade Regular will be the development of technologically advanced and knowledge-based industries such as information technology (IT), biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals. By focusing on value addition rather than merely increasing export volumes, this strategy aims to enhance India’s global trade profile.

A connector country will trade a lot in intermediate products and services which will require serious tariff reductions for a large number of products. This will help build on forward and backward supply chain linkages in the economy with the aim of facilitating Global Value Chain (GVC) trade. The government could retain power through an industrial policy that promotes trade and seeks to include a growing number of firms in its manufacturing and services supply chains. Obviously, improved infrastructure and logistics sit at the heart of Trade Regular. Each day of transit delays reduces trade by 1 percent, and a connector country approach is crucially reliant on supporting structures of trade facilitation – also in the area of services [10]

Financial openness is also required, including greater capital account openness, which is important for drawing and attracting FDI, encouraging portfolio investment, and securing foreign bank lending.[11] The model also calls for systemic reforms aligning regulations with global standards in areas such as digital governance and intellectual property rights (IPR). Reducing traditional border barriers is part of Trade Regular policy which should also include better Rules of Origin (RoOs) regulations.

Essentially, Trade Regular would require significant domestic, economic and institutional reforms. It goes without saying that such reforms are often controversial, drawing the resistance from protected industries, policymakers, and labour groups. At the same time, such resistance should not be exaggerated, especially in an economy that is already rapidly modernising. Modern deep FTAs and mega-regional pacts demand commitments but they do not conform to past fears of laissez faire and the loss of government agency. Nor do they have to reflect modern fears of accepting “regulatory imperialism”. It is more about making sure that production in India which is destined for foreign markets can comply with their standards.

[1] Ministry of Steel. सरकारी खरीद में घरेलू रूप से विनिर्मित लोहा एवं इस्पात उत्पादों को प्राथमिकता देने हेतु नीति (डीएमआई एंड एसपी). Available at: https://steel.gov.in/en/policies/policy-providing-preference-domestically-manufactured-iron-and-steel-product-govt

[2] Niti Aayog. National Policy on Electronics, 2019. Available at: https://nitiforstates.gov.in/policy-viewer?id=PNC510C000342

[3] WTO (2020) Trade Policy Review, India. Report by the Secretariat. WT/TPR/S/403.

[4] Batra, A. (2022). India’s trade policy in the 21st century. Routledge.

[5] Sharma, K. & Gakuto, T (2020, September 4). ‘Modi Calls for “Trustworthy” Supply Chains, in Alternative to China’ Nikkei Asian Review, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Modi-calls-for-trustworthy-supply-chains-in-alternative-toChina

[6] In South Asia, projects are primarily concentrated in Bangladesh, focusing on railways, highways, and energy, followed by infrastructure initiatives in Bhutan and Nepal.

[7] Saklani, U. (2023). Building infrastructure abroad: India’s enterprises in Africa and South Asia. Future DAMS Policy Report. Manchester: The University of Manchester.

[8] Ministry of External Affairs. India-Brazil Relations. Available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Brief_on_India Brazil_Relations__unclassified___22.1.24_.pdf

[9] By upgrading existing FTAs, such as the India-Malaysia Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA) (2011), India-Korea Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) (2009), India-Sri Lanka FTA (2000), SAARC Preferential Trading Agreement (PTA) (1993), India-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) FTA (2004), and the India-Nepal Treaty of Trade (1991) and exploring opportunities with other Global South countries, India can enhance its global trade engagement.

[10] Djankov, S., Freund, C., & Pham, C. S. (2010). Trading on time. The review of Economics and Statistics, 92(1), 166-173.

[11] Aman, Z., Granville, B., Mallick, S. K., & Nemlioglu, I. (2024). Does greater financial openness promote external competitiveness in emerging markets? The role of institutional quality. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 29(1), 486-510.

3. India’s Trade Profile: Impulses to Policy Choices

Obviously, India’s actual trade performance should be a determining factor for its trade policy. While it is sometimes tempting to build policy on abstract theory or obtuse ideological premises, the first condition for successful trade policy is that it reflects the actual reality of industry structures, competitive advantages, and how the economy links up with the rest of the world. These are factors that are exposed to change, especially in economies that are going through a period of modernisation: they should not be approached as eternal truths. Importantly, good governance in trade policy basically means that internal and external factors of economic performance are united. Poor trade policy is usually defined by the opposite: the separation of internal and external policy and performance, leading to significant imbalances in the economy.

3.1. Trade and FDI Performance

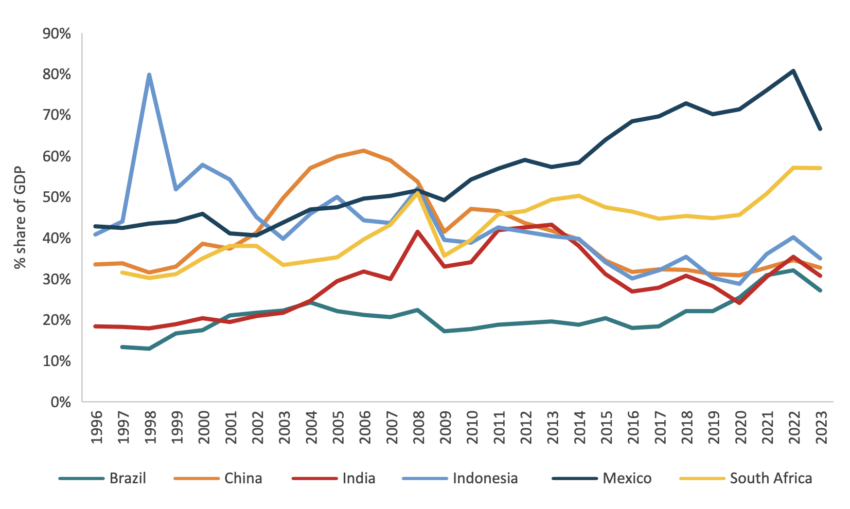

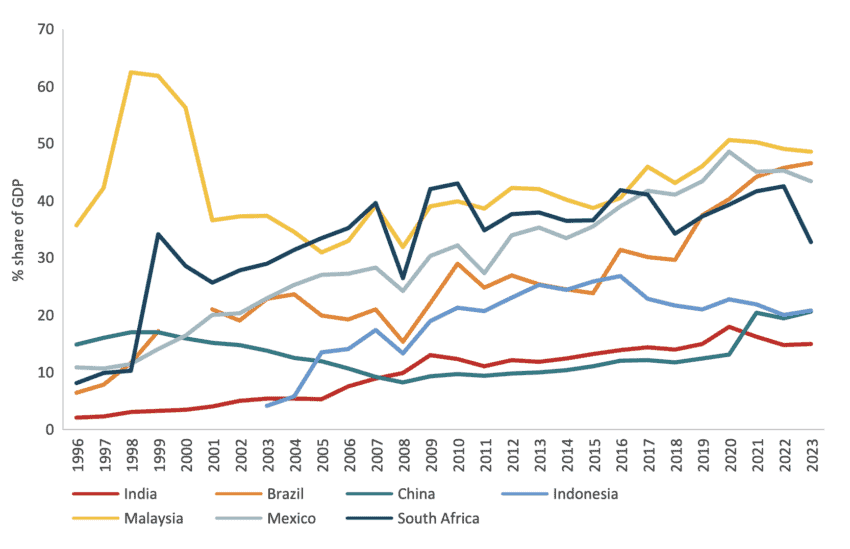

So what are the realities that India’s trade policy choices should reflect? A starting point is that India is a large economy and encompasses many different sectors, all representing big varieties in trade opportunity and internal firm-level performance. In 2023, India had a GDP of USD 3.57 trillion with a growth rate of 8.2 percent. However, India’s trade sector has not seen the same growth as the general economy. Compared to similar economies, India’s trade contributions are comparatively low when measured as a percentage of the GDP. In 2023, India’s foreign trade only accounted for 31 percent of its GDP while countries like Mexico, South Africa, and Indonesia accounted for shares amounting to 67, 57, and 35 percent of their GDPs highlighting is a significant gap. These all smaller economies and, all else equal, will tend to trade more as a large economy like India.

India and China share some similarities in terms of their rapid economic growth and large economic size. However, while China accelerated its foreign trade and increased inward FDI, India’s economic growth was a result of increasing production in other economic sectors. For instance, even in the 1990s, when India went through widespread economic liberalisation, India’s foreign trade contribution as a share of the GDP was still much lower compared to China (see Figure 1). While China’s trade sector peaked at 60 percent of GDP in its acceleration phase, India’s peak was at 43 percent. Since then, the trade sector has declined. These statistics point to the low priority India has always placed on trade-led economic growth.

This is also evident from India’s performance in global exports. Despite being a large economy, in 2023, India was only the 12th largest exporter of goods globally. Meanwhile, China was the largest exporter of goods, followed by the European Union and the United States.

Figure 1: Trade as a percentage of GDP (1996-2023) Source: UNComtrade, GDP data: World Bank. Note: The authors used import data for calculations since it has more accurate data.

Source: UNComtrade, GDP data: World Bank. Note: The authors used import data for calculations since it has more accurate data.

In 2023, India’s global exports of goods and services accounted for USD 833 billion. Goods exports accounted for 47 percent of the total exports, while services accounted for 53 percent. This is an important data point. The larger share of services’ exports reflects the composition of India’s domestic economy. In 2024, the services sector accounted for 55 percent of the total economy, much larger than both, agriculture and manufacturing combined[1].

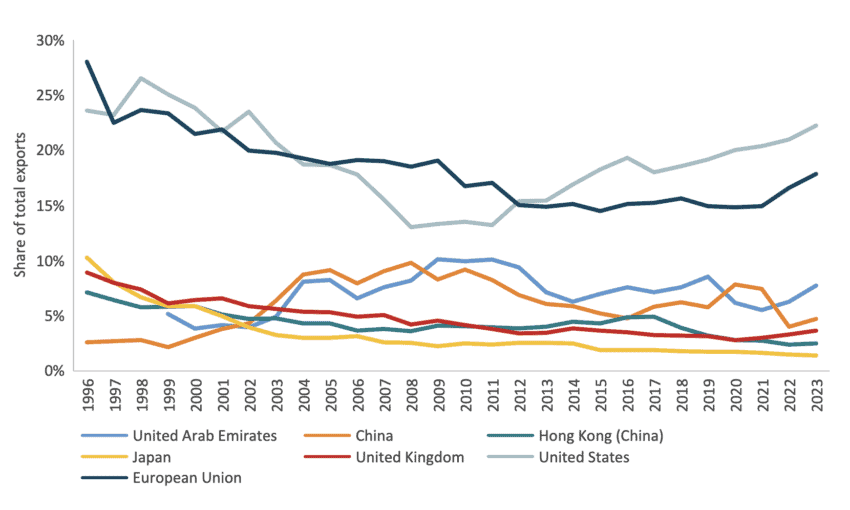

In terms of goods, India had total exports of USD 393 billion in 2023. Since 1996, big, developed economies such as the United States, European Union, and the United Kingdom have managed to maintain their foothold as the largest markets for India’s goods exports. In fact, the US has increased its share of India’s exports substantially since the beginning of the 2010s. China and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have emerged as important markets for India too (Figure 2). It is notable that none of these countries, barring China, are geographically close to India. This points to a unique characteristic of India’s foreign trade composition – unlike most countries that tend to have stronger trade relations closer to home, India has established major trade partners over longer geographical distances. Part of this is a result of challenging political circumstances in the neighbourhood, but it can also be attributed to India’s preference of trading with large liquid markets.

Figure 2: Top export markets for India over time (1996-2023) Source: UNComtrade. Note: The authors used import data for calculations since it has more accurate data.

Source: UNComtrade. Note: The authors used import data for calculations since it has more accurate data.

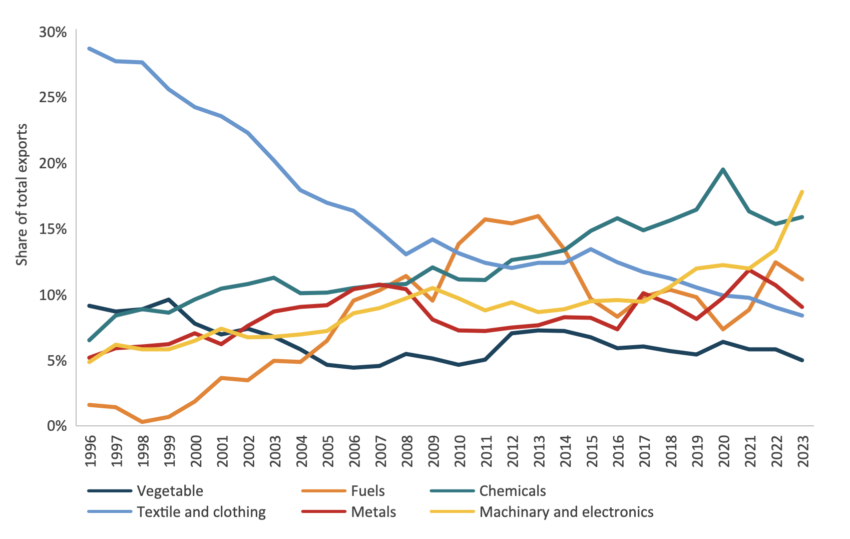

In terms of India’s composition of exported goods, there have been significant changes since the mid-1990s. Sectors such as chemicals as well as stone and glass have remained in the top 5 exported goods. However, while the share for stone and glass has declined from 19 to 12 percent, the share for chemicals has gone up significantly from 6 percent to 16 percent. At the same time, there has been a marked decrease in the exports of lower value-added manufactured goods and raw materials. This includes sectors such as vegetables and hides and skins, but more importantly textiles and garments are no longer in the top five exported sectors. They have been replaced by sectors such as machinery and electronics, and fuels, and metals. In fact, between 1996 and 2023, machinery and electronics have replaced textile and garments as the largest exported sector (Figure 3). With the rise of the chemicals and machinery and electronics sectors in India’s goods exports, there is an obvious conclusion on the rise of India’s exports of higher value-added goods over time. And this increase has come at the expense of lower value-added products, such as agricultural commodities and textiles and garments.

A closer look at the manufacturing sector points to the same top five manufacturing product categories throughout 1996 and 2023. These are electrical machinery equipment, nuclear reactors, vehicles, optical, photography, cinematic equipment, and furniture bedding, and mattresses. However, the share of exports of electrical machinery equipment has increased from 20 percent to 40 percent while the share of exports of nuclear reactors, boilers, and machinery which has decreased from 41 percent to 29 percent between 1996 and 2023.

Figure 3: Top exported sector for India over time (1996-2023)  Source: UNComtrade. Note: The authors used import data for calculations since it has more accurate data.

Source: UNComtrade. Note: The authors used import data for calculations since it has more accurate data.

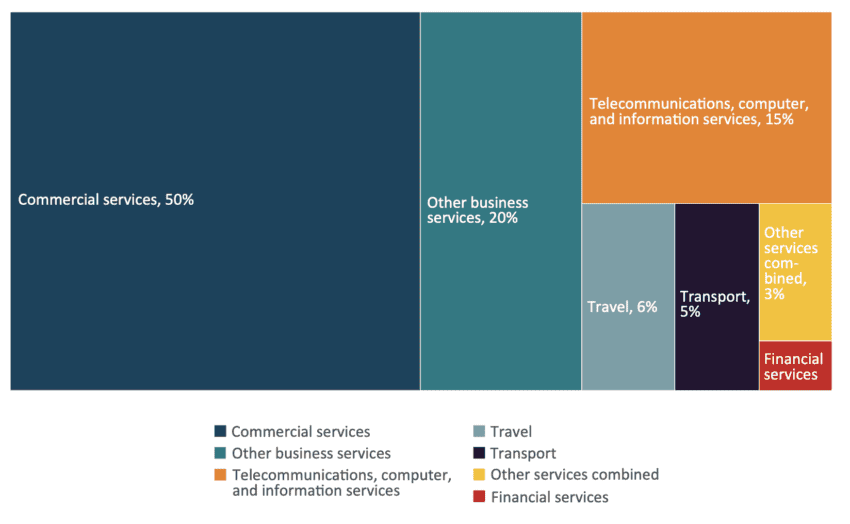

India’s largest services exports in 2023 were commercial services (USD 219 billion), followed by other business services (USD 87 billion) and telecommunications, computer, and information services (USD 68 billion). This is a notable performance, given that these are high value-added services. What is more, these three services exports made up 85 percent of India’s total services exports in 2023. Services essential for India to take on a connector country role such as transport and financial services made up 6.3 percent of India’s total exports. Over the past five years, India’s primary export partners have remained the same – China, Singapore, United Kingdom, European Union, and United States. These five countries have also held a consistent share of India’s total services exports, amounting to approximately 56 percent since 2019. India’s exports of services have consistently made their way to the same few partners as India’s exports of goods.

Figure 4: India’s exports of services (2023) Source: OECD BaTis

Source: OECD BaTis

Like trade in goods, India’s stock of foreign direct investment as a share of the GDP is also underperforming compared to similar economies. For instance, in 2023, India had an FDI stock of USD 536.9 billion or 15 percent of its GDP. Meanwhile countries such as China, Brazil, and South Africa had FDI stocks of 21, 47, and 33 percent as a share of their GDPs. Over time, India’s FDI stock as a share of its GDP has only increased by 13 percent. It is not only a comparatively low figure, but also a factor reducing the economic growth potential of the country.

Figure 5: FDI Stock as a share of GDP (1996-2023) Source: UNCTAD Stat

Source: UNCTAD Stat

Between 2000 and 2024, India’s service sector attracted the highest FDI equity inflow of 16 percent amounting to USD 115.18 billion. This was followed by the computer software and hardware industry at 15 percent, trading at 7 percent, telecommunications at 6 percent, and the automobile industry at 5 percent[2].

In India, in terms of assets, machinery and equipment accounts for 52.5 percent of gross fixed capital formation (GFCF)[3] of the country, while construction accounts for 47.5 percent. Meanwhile, in terms of industries of use, the manufacturing sector accounted for the highest share of GFCF of 25.2 percent, followed by electricity, gas, and water (12.6 percent), real estate (11.3 percent), and public administration and defence (11.3 percent).

3.2. Key Observations for India’s Trade Policy Choice

India’s current trade performance and its evolution over time highlights important some key findings that should have significant consequences for India’s future trade policy choices. Indeed, they also carry important for the trade models sketched in the previous chapter.

First, even if India is a large economy, its rapid growth has not been the result of an accelerating trade sector. Unlike other large emerging economies, India’s foreign trade accounts for a smaller share of the GDP. Unlike China, which also started liberalising its economy and trade around the same time as India, India did not adopt a trade and investment-led growth model.[4] India’s rapid economic expansion has, therefore, been the result of higher production for domestic use and reflects the country’s policy priorities which are more inward-looking than in comparable economies. Importantly, India has not experienced a trade acceleration phase like in many other larger emerging economies. Nor has it experienced a boom in inward FDI. This points to an opportunity for India to use trade as an engine for exponentially accelerating economic growth.

India’s export composition also stands out. It is very notable that India’s exports of services outweigh its exports of goods. Naturally, this reflects India’s domestic composition of a large services sector, but it also points to a strong footing that India has established in newer forms of trade. The main categories of services also share the feature of being high value-added and in activities that usually come with many forward and backward linkages. In other services, the actual export sales are an interface for larger economic integration, and it builds on intense integration in value chains with customers and other services suppliers.

It is worth labouring on the point about value added. In both services and goods exports, India is increasingly trading in higher value-added exports. For instance, in the exports of goods, India has seen a rapid increase in the share of chemicals and machinery and electronics. This is in stark contrast to the steep decline in export shares of the textile and garment sector. At the same time, in terms of exports of services, commercial services, followed by other business services and telecommunications, computer, and information services have accounted for lion share of the total services exports.

India has, therefore, become increasingly competitive in the international market for high value-added exports. This is an indication of India’s revealed comparative advantage in high value-added sectors, and points to strategic policy choices that India can make for accelerating the volume of investment in these sectors and efforts to increase margins and value added further. Likewise, this revealed comparative advantage also points towards impetus for India to focus on newer trade issues in trade agreements, including trade in services, digital trade, the conditions for cross-border integration of ideas, management, teams and other so-called intangible assets and modern factors of production.

The goods sector also feature an interesting trend that leads us to the same conclusion. The rise in exports of chemicals and machinery and electronics have been strong these are sectors in which trade form a part of large global supply chains. Both chemicals and machinery and electronics are highly interactive sectors with large amounts of trade taking place in intermediaries instead of the final product. They also include high value added activities, like research and development in contract development firms. While electronics usually include final product assembly, they rely on substantial intermediate trade – pointing to India’s rising role in GVCs.

Finally, India’s largest importers of goods and services have remained the top markets over time. Simply, the large economies in the world play a very significant role for India’s exports. Between 1996 and 2023, the share of Indian exports in goods to the United States and European Union has gone down by 10 percentage points. However, their share of India’s exports increased from 30 percent to 40 percent since 2010. Similarly, between 2019 and 2023 the share of the United States and European Union in India’s serviced exports remained stable at about 40 percent. Even if economies such as China, the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore have made their place in the top 5 markets, a large part of the exports are taken up by the US and the EU.

[1] Ministry of Finance, 2024, Services sector continues to contribute significantly to India’s growth, accounts for about 55 per cent of total size of the economy in FY24. Accessed at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2034920

[2] IBEF. Available at: https://www.ibef.org/about-us

[3] GOI Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Saving and Capital Formation. Available at: https://mospi.gov.in/136-saving-and-capital-formation

[4] Wang, X., Fan, G., & Zhu, H. (2007). Marketisation in China, progress and contribution to growth. China: Linking markets for growth, 30-44; Dorn.,J. (2023, October 10). China’s Post-1978 Economic Development and Entry into the Global Trading System. Cato Available at: https://www.cato.org/publications/chinas-post-1978-economic-development-entry-global-trading-system

4. Conclusion

India’s current trade performance highlights its position as a high value-added economy, especially in terms of its share of exports and the larger composition of services exports. This underscores India’s ability to adapt to newer forms of trade and engage with the global economy. As a result, India has an opportunity to leverage its trade capacity to significantly improve economic growth. Therefore, an Indian trade policy based on status quo – Trade Zero – is not a recommended strategy for India, especially given its reliance on large markets, services, and high-value-added exports. This is a trade profile that suggest India should deepen its integration with the United States and Europe and exploit opportunities to take up a larger share of these countries imports of India’s key trade sectors.

While engaging broadly with global markets offers benefits, focusing heavily on large markets, where India has already made significant inroads, also presents challenges – especially in terms of policy and new terms of trade. Given the global shifts, including rising protectionism and trade reciprocitarianism in the US and other large economies, it can become increasingly challenging for India to deepen trade relations with big economies without changing its own policies. To navigate this, India should consider diversifying its trade partners and strengthening relationships with regional partners. However, this decision also points to a bargain between national policy control on the one hand, and trade growth on the other.

Neutral openness remains essential. This approach encourages flexible collaborations, allowing India to engage with a diverse range of global partners without being overly reliant on any single one. This flexibility enhances India’s resilience against global trade shifts, political changes, or economic disruptions in major markets. Neutral openness also ensures that India can maintain strategic autonomy while still benefiting from global value chains, international investments, and emerging opportunities in innovative sectors.

India should find a better balance between the internal and the external economy – or between international partners and domestic industries, especially in high value added sectors. These sectors require significant capital, advanced knowledge, and access to complex inputs, making them critical to India’s future trade strategy. To fully leverage these sectors, India needs a more integrated approach to global trade, engaging in cross-border production networks, knowledge exchange, and technology transfer.

It is notable that, in its trade performance, India is already on the way to become a “connector country”. In a way, the real economy has already made the choice of trade model, and it has opted for “Trade Regular” – even if the politics of Indian trade policy often present itself as a reluctant globaliser and uses a rhetoric closer to Trade Zero. The data suggests that India is already exploiting high value added exports and has a growing share of services exports that leads its connectivity. This indicates that India is well on its way to economic diversification and expanding its exports in goods, and services, which paves the way for the connector country model. By deepening its integration into GVCs, India can increase its role in highly integrated sectors and industries that are crucial in global production networks.

To continue its trajectory of growth in high-value-added exports—especially in sectors driven by R&D, regulatory coherence, and cross-border production networks—India would benefit from trade policies cantered on “neutral openness” and adaptability to different trade and regulatory regimes. This is, in essence, the Trade Regular model. This approach would help dismantle trade barriers more efficiently and foster sectors that can accelerate India’s rise in productivity and value added.

India stands at an inflection point. Its service and high value-added exports-led growth model provides resilience, but sustaining momentum demands a structural shift towards deeper integration models and a policy that gives priority to sectors with strong competitive advantages.

References

Airtel. Available at: https://www.airtel.com/

Aman, Z., Granville, B., Mallick, S. K., & Nemlioglu, I. (2024). Does greater financial openness promote external competitiveness in emerging markets? The role of institutional quality. International Journal of

Finance & Economics, 29(1), 486-510.

Batra, A. (2022). India’s trade policy in the 21st century. Routledge.

China’s Post-1978 Economic Development and Entry into the Global Trading System. Cato Available at: https://www.cato.org/publications/chinas-post-1978-economic-development-entry-global-trading-system

CSO Letter to the Commerce Minister on the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and India joining the trade pillar. Available at: https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPEF_Letter-to-MoC_May-26-1.pdf

Djankov, S., Freund, C., & Pham, C. S. (2010). Trading on time. The review of Economics and Statistics, 92(1), 166-173.

FDI Intelligence. (2024). India Inc flexes muscles on global stage. Available at: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/291e6421-fc21-52f3-807c-5ccb55a1ae63

GOI Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Saving and Capital Formation. Available at: https://mospi.gov.in/136-saving-and-capital-formation

HCLTech. Available at: https://www.hcltech.com/global-presence

IBEF. Available at: https://www.ibef.org/about-us

Infosys. (2023). Navigating change. Available at: https://www.infosys.com/investors/reports-filings/documents/global-presence2023.pdf

Mahindra. Available at: https://www.mahindra.com/our-businesses/global-presence;

Manak. I. (2025). How India Disrupts and Navigates the WTO. Council for Foreign Relations. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/article/how-india-disrupts-and-navigates-wto

Ministry of External Affairs. India-Brazil Relations. Available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Brief_on_IndiaBrazil_Relations__unclassified___22.1.24_.pdf

Ministry of Finance, 2024, Services sector continues to contribute significantly to India’s growth, accounts for about 55 per cent of total size of the economy in FY24. Accessed at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2034920

Ministry of Steel. सरकारी खरीद में घरेलू रूप से विनिर्मित लोहा एवं इस्पात उत्पादों को प्राथमिकता देने हेतु नीति (डीएमआई एंड एसपी). Available at: https://steel.gov.in/en/policies/policy-providing-preference-domestically-manufactured-iron-and-steel-product-govt

Niti Aayog. National Policy on Electronics, 2019. Available at: https://nitiforstates.gov.in/policy-viewer?id=PNC510C000342

Saklani, U. (2023). Building infrastructure abroad: India’s enterprises in Africa and South Asia. Future DAMS Policy Report. Manchester: The University of Manchester.

Sharma, K. & Gakuto, T (2020, September 4). ‘Modi Calls for “Trustworthy” Supply Chains, in Alternative to China’ Nikkei Asian Review, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Modi-calls-for-trustworthy-supply-chains-in-alternative-toChina

Strengthening the WTO to Promote Development and Inclusivity: Communication from Plurinational State of Bolivia, Cuba, Ecuador, India, Malawi, Oman, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda and Zimbabwe,” World Trade Organization, WT/GC/W/778/Rev.1, July 22, 2019.

Tata. Available at: https://www.tata.com/tata-worldwide

The Continued Relevance of Special and Differential Treatment in Favour of Developing Members to Promote Development and Ensure Inclusiveness: Communication from China, India, South Africa, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Plurinational State of Bolivia, Kenya, Cuba, Central African Republic and Pakistan,” World Trade Organization, WT/GC/W/765/Rev. 2, March 4, 2019.

Wang, X., Fan, G., & Zhu, H. (2007). Marketisation in China, progress and contribution to growth. China: Linking markets for growth, 30-44; Dorn.,J. (2023, October 10).

Wipro. Available at: https://www.wipro.com/about-us/wipro-group-companies/

WTO (2020) Trade Policy Review, India. Report by the Secretariat. WT/TPR/S/403.

WTO. (2023, December 21). Statement By India On Agenda Item 18 General Council Meeting – 13 – 15 December 2023. WT/GC/262. Available at: https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/262.pdf&Open=True