Discrimination, Exclusion and Environmental Harm: Why EU Lawmakers Need to Ban Freight Transport Restrictions to Save the Single Market

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: EU Single Market European Union Services

Summary

The EU’s Mobility Package 1 legislative proposal was once intended to improve the working conditions of truck and small-van drivers in the EU. Initially, the European Commission also aimed at securing a smooth and non-discriminatory functioning of the Single Market. Some provisions of the current package may indeed have a positive impact on drivers’ working conditions, e.g. limits on working time and obligatory rest periods. However, over the past three years, the legislative procedure towards the current draft of the Mobility Package 1 was hijacked by the protectionist agenda of Western Europe’s haulage and logistics businesses. Spearheaded by the French government, some national governments and Members of the European Parliament called for tighter freight cabotage and return-to-home provisions to shield Western European transport markets against competition from other EU Member States. The proposed restrictions to cross-border trade in the European Single Market are up for a vote in the European Parliament in mid-2020.

Learnings from the Covid-19 situation in the Single Market: In its response to Covid-19 border measures, the European Commission called on EU governments “to act immediately to temporarily suspend all types of road access restrictions in place in their territory (weekend bans, night bans, sectoral bans, etc.) for road freight transport and for the necessary free movement of transport workers.” These actions are step in the right direction and should continue even once the Covid-19 crisis is over, yet they are the exception not the rule in the EU. The rise of protectionist measures to Member States’ national transport markets vividly demonstrates the need to abolish freight cabotage restrictions in defence of the Single Market. For the sake of a greener, more inclusive and better functioning of the European Single Market, lawmakers need to abandon all existing restrictions on freight cabotage services in the EU27 and vote against new restrictions such as cooling-off periods and return-to-home policies. Maintaining legal restrictions on the freedom to provide transport services in the EU’s Single Market would increase tensions between economically less-developed countries in Central and Eastern Europe and more developed Western European countries – economically, mentally and politically.

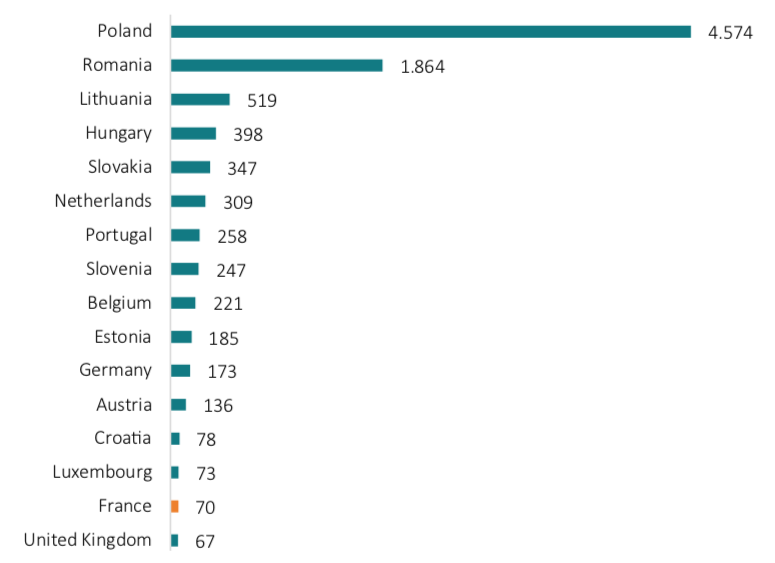

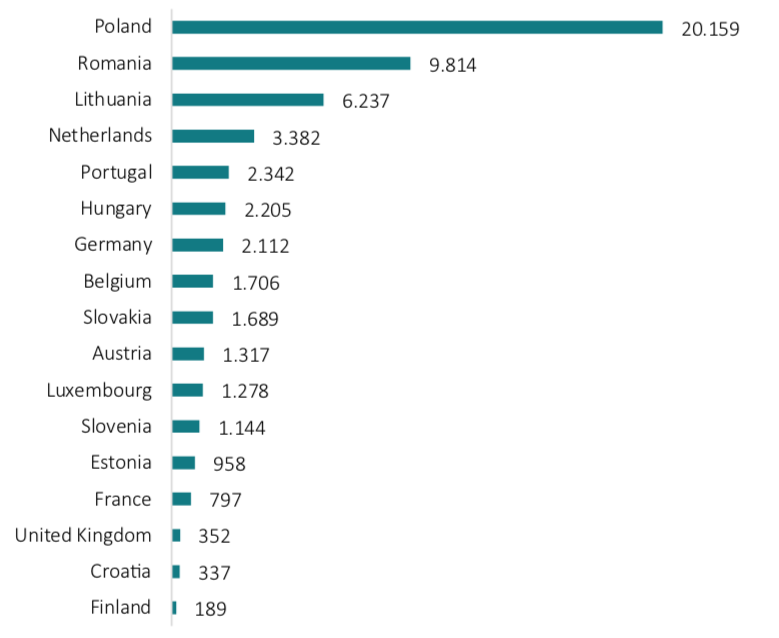

Discrimination on the basis of EU passport: Cabotage restrictions infringe upon the fundamental values stipulated in the Lisbon Treaty. Furthermore, data on transport flows and employment demonstrate that cabotage regulations disproportionately discriminate against Eastern European companies and citizens. Available data shows that Polish (4,574 enterprises), Romanian (1,864), Lithuanian (519), Hungarian (398), Slovakian (347), and Dutch (309) haulage companies are disproportionately affected by current EU-imposed cabotage restrictions. By contrast, only a very small number of French freight transport companies (an estimated number of 70 enterprises) directly depend on intra-EU cabotage services. In France, only about 800 workers employed in road freight transport services are directly affected by the restrictions. The numbers are substantially higher for other, particularly Central and Eastern European, countries: 20,100 persons in Poland, 9,800 in Romania, 6,300 in Lithuania, 3,400 in the Netherlands, 2,300 in Portugal, 2,200 in Hungary, and 2,100 in Germany.

Exclusion from economic opportunity: Freight cabotage restrictions increase the administrative burden for internationally operating haulage companies across the EU. Industry assessments indicate that additional limitations on international freight transport services within Europe’s Single Market would raise the prices of transporting goods in Western Europe. Negative impacts are estimated for employment, wage growth and the process of economic convergence in Central and Eastern Europe. In addition to the EU’s existing freight cabotage restrictions, new limits on cross-border freight transport in the EU – such as EU law-imposed return-to-home trips and EU-mandated cooling-off periods – would deprive many Eastern European households of economic opportunities and impede the process of economic convergence and converging standards of living in the EU.

Environmental harm: The return-to-home policies proposed in the latest Mobility Package 1 would require companies to send drivers back to operational centres or the driver’s place of residence. Return-to-home provisions would substantially increase the number of empty trailers on European roads. Accordingly, and adding to the adverse environmental impacts caused by existing freight cabotage restrictions, new EU-imposed return-to-home obligations would deteriorate Member States’ carbon emission footprints. The highest increases would take place in the EU’s major transit countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. While this is recognised by the European Commission, the majority of the European Parliament’s Transport Committee is still pushing for such policies to be implemented as the EU law.

How to save the EU’s fundamental values and the freedoms of the Single Market – lessons from aviation: In 1993, the EU completed the EU’s internal aviation market for passenger cabotage. Guided by the European Commission, EU lawmakers should follow the same rationale for freight cabotage services to render the Single Market more single and less discriminatory. In the process towards a real, more inclusive Single Market, EU lawmakers must abstain from catering Western European companies’ vested commercial interests, which stifle economic opportunity across the EU and stand in opposition to the EU’s fundamental principles for international trade and a competitive and social market economy.

1. Introduction

Current EU legislation severely restricts the transport of goods within a Member State by truck operators from other EU countries. What is known as “freight cabotage regulations” mandates foreign truck drivers to leave a country after conducting a limited number of transport services. Based on a 2009 reform, the current EU regulation allows foreign haulage companies to carry out “no more than 3 cabotage operations within a 7-day period” following an international consignment. The current rules purposely discriminate against workers from Central and Eastern Europe, who successfully compete in the EU’s high-wage countries – mainly Western European countries. Despite the principle of a common non-discriminatory transport policy, the EU’s current cabotage law stifles economic opportunity and economic convergence in the EU.

The Mobility Package 1 is a further attempt by some EU lawmakers – both in the Member States and the European Parliament – to break-up the commonly shared European Single Market. Pushed by Emanuel Macron and his administration, the “Mobility Package 1” proposals aim to maintain the current straightjacket for freight cabotage allowing a maximum of 3 separate freight transports in 7 days.[1] Even worse, the proposals now also include rules to prevent a rise in free international transport services in the Single Market: a “cooling-off” period of four days was proposed to restrict the number of free cabotage operations that can be carried out in the same country using the same truck or light vehicle. And on top of this, new EU law has been proposed to oblige haulage firms to send their drivers back to their mother countries every four weeks.

The Mobility Package 1 was once intended to enhance the working conditions of truck drivers in the EU and to secure a smooth and non-discriminatory functioning of the Single Market. Some provisions of the current package may indeed have a positive impact on drivers’ working conditions, e.g. working time restrictions and obligatory rest periods. However, over the past three years, the legislative procedure towards the current draft of the Mobility Package 1 was hijacked by the protectionist agenda of Western Europe’s haulage and logistics businesses. Tighter EU-imposed regulations, as foreseen by the Mobility Package 1 proposals, would manifest a discriminatory legal system that prohibits free freight cabotage in the EU27. They would increase discrimination, slow-down the process of economic convergence, and increase overall carbon emissions. Drawing on legislative texts, interviews with stakeholders as well as economic and environmental data, this paper discusses the potential implications in more detail.

Section 2 discusses the evolution and rationale of restrictions to free freight cabotage and EU and freight transport services respectively. It provides an overview of cabotage and other transport services restrictions the Mobility Package 1 proposals. Referring to recent developments in response to the Covid-19 situation, Section 3 discusses the protectionist motivation of policies that restrict road freight cabotage in the EU. Section 4 discusses the degree of legal discrimination and the corresponding adverse economic impacts of restrictions of free cabotage on operators from different EU Member States. Section 5 discusses the adverse environmental implications of restrictions on free freight cabotage in the EU. It discusses estimates for the negative environmental impacts of restrictions on freight transport services in the EU as proposed in the Mobility Package 1. Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the implications on Single Market integration.

[1] 2017/0123(COD), Ordinary legislative procedure (ex-codecision procedure), Regulation, Amending Regulation (EC) No 1071/2009 2007/0098(COD) and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1072/2009 2007/0099(COD).

2. The EU's Freight Cabotage Laws: Designed to Discriminate by Passport

2.1 Europe’s Restrictions on the Freedom to Provide Transport Services Across Borders

The term “cabotage” is generally used to describe the transport of goods or persons between different locations within the same country, by a transport official that is from another country. It refers to transportation by sea, land (trucks and trains) and air.

EU freight cabotage regulations were initially invented to keep foreign freight transport operators – in simple terms: truck drivers – out of national European markets. Indeed, most countries in the Western World regulated the growing road freight transport industry in the wake of the Great Depression to curb oversupply and competition. Freight cabotage regulations also aimed to protect the rail freight transport sector from low-cost road transport. Governments introduced various forms of market restrictions, such as entry control, capacity control, and price control (OECD 2001; Belzer 2000).

The intra-European road freight transport was strictly regulated, mainly through bilateral agreements. This system remained for several decades, even though this was counter to the Treaty of Rome which in 1957 prescribed a free transport market in the European Economic Community (EEC). However, it took over 25 years, and a judgment in the European Court of Justice (ECJ), before the process of liberalisation started in earnest. Quantitative restrictions that inhibited full and equal access to the EU’s internal road freight transport market had to be lifted by the end of 1992 at the latest.[1] Freight cabotage (domestic freight transports carried out by foreign haulage firms) was to be gradually liberalised until 1998, along with national reform efforts targeted at domestic road freight transport markets during the 1990s, when most Western European countries also deregulated their domestic freight transport services (European Parliament 2020a).

The principle of a common and non-discriminatory EU transport policy was set out in the EU’s founding treaties, the Treaty of Rome, calling for the freedom to provide international transport services across European borders. However, Member States’ appetite for liberalising legislation remained low. In 1982, the European Parliament found that Member States measures “by no means meet the requirements of the common market”. Following a European Parliament Resolution, the Court of Justice found in May 1985 that the Council and Parliament had failed to act within the transition period of the Treaty of Rome concerning the freedom to provide international transport services, and the freedom of non-resident transport operators to provide national transport in other EU member states.[2]

Importantly, in 1982 the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the institution of proceedings against the Council of the European Communities for failure to act in the field of European transport policy. The Parliament’s major concerns were about the process of economic integration – i.e. the future state of the Common (Single) Market –, distortions of intra-community competition, and negative implications on the freedom of the movement of goods. The Parliament argued that

“[t]he common transport policy is part of the general process of integration contemplated by the Treaty. Among the activities of the Community referred to in Article 3 of the Treaty the common transport policy has the same rank as the common agricultural policy or the institution of a system ensuring that competition in the common market is not distorted. It must be achieved in step with the development in the other areas governed by the Treaty, since inadequate progress in the transport sector risks compromising the achievement of the objectives of the Treaty in other areas, in particular with regard to the free movement of goods. (see Court ruling Case 13/85 of 22 May 1985).

Initial EC regulation was only implemented in 1993, (Regulations (EEC) No 881/92 and (EEC) No 3118/93) allowing a limited number of truckers with “community authorisation” to provide road haulage services within other Member States – on condition that they were only provided on a temporary basis. Back then, the Member States still operated a strict authorisation and quota system for cabotage operations, explicitly aiming to keep foreign EU competitors out of their national markets.

In May 2010, the previous regulation was replaced with a new regulation (EC 1072/2009), whose actual aim was to improve the efficiency of road freight transport by reducing the number of empty trips (trailers) after the unloading of international transport operations. In fact, the European Commission was aiming to reduce the amount of empty running trucks (vehicles with no merchandise), the costs of transport, traffic and pollution. Following a compromise between the Council and the Parliament, the EU introduced a system of “consecutive cabotage”, which allowed for a carrier/haulier to complete three national transports in a host member state after completing an international transport. However, these three national transports could only be completed within seven days of the completion of the international transport.[3]

In 2017, the Juncker Commission proposed to revise the regulation on transport and mobility (COM (2017) 0281). Labelled “Europe on the Move”, the proposal was part of a larger legislative initiative designed to modernise Europe’s transport system. The legislative proposal consists of three Mobility Packages focusing on different areas of the transport sector and serve different purposes (European Parliament 2020c):

- The first Mobility Package was introduced in May 2017. This package has a focus on access to the road haulage market, vehicle taxation, enforcement requirements in road transport, driving and rest time requirements, hired vehicles without drivers for haulage by road, postings of workers in passenger transport.

- The second Mobility Package was introduced in November 2017 and focuses on the Clean Vehicle Directive, access to the bus and coach market, CO2 standards for cars and vans, the battery initiative, and the combined transport directive.

- The third Mobility Package was introduced in May 2018 focusing on CO2 standards for heavy-duty vehicles, the digitalisation of freight transport documents, infrastructure safety management, and deployment of advanced vehicle technology.

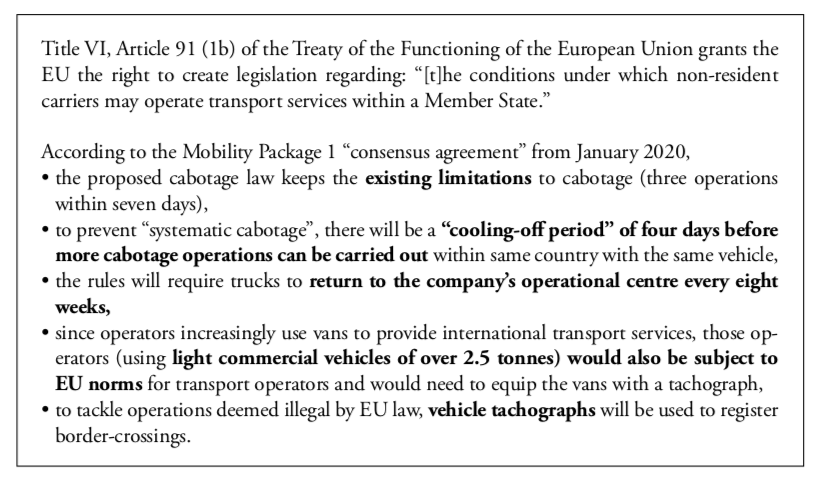

According to the latest proposals of the Mobility Package 1, the freedom to provide freight transport services across EU borders is restricted by three types of legal obligations: the obligation to leave a Member State after the provision of a limited number of cabotage operations, a new return-to-home policy that in effect reduces the number of monthly cabotage operations and a mandatory “cooling off” period explicitly intended to further restrict the freedom to provide cabotage services (see Box 1).[4]

Box 1. Mobility Package 1 proposed regulations Source: 2017/0123(COD), Ordinary legislative procedure (ex-codecision procedure), Regulation, Amending Regulation (EC) No 1071/2009 2007/0098(COD) and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1072/2009 2007/0099(COD) and European Parliament (2020d).

Source: 2017/0123(COD), Ordinary legislative procedure (ex-codecision procedure), Regulation, Amending Regulation (EC) No 1071/2009 2007/0098(COD) and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1072/2009 2007/0099(COD) and European Parliament (2020d).

2.2 Western Europe’s Push for Stifling the Freedom to Provide Transport Services Across National Borders within the EU

One of the main reasons why the Mobility Package 1 was introduced was a political conflict between Western and Central and Eastern European Member States over the treatment of foreign haulage companies and truck drivers. Wages for truck drivers are generally lower in Central and Eastern Europe compared to more economically developed Western European countries like France, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.

In 2014, responding to the efforts of the European Commission to liberalise short distance road freight transports, the French transport minister Alain Vidalies, along with others, referred to Eastern European drivers as “road slaves” (Euractiv 2014). It was argued that the misuse of cabotage and the range of wages, social laws and fiscal laws across the EU have resulted in damages in some EU Member States. There was the perception that patterns in the industry qualify as social dumping and anti-competitive practices by the Eastern European countries, with companies maintaining the low wage and the long hours of their drivers.

Similarly, in early 2017, nine Transport ministers from Western European countries complained about the practices of Eastern European Member States. The Belgian Transport Minister said, “eastern countries must understand that we need a fair system.” Other transport ministers from France, Germany, and Italy have echoed the same sentiment. They argue there must be equality in treatment for truck drivers across Europe (Euractiv 2017). In 2016, Violeta Bulc, European Commissioner for Transport, even called for a minimum wage for truck drivers, which lacked political support in the Member States (Euractiv 2016).

Even though it was intended to resolve the conflict, the Mobility package 1 proposal became an additional source for contention. Many Central and Eastern European Member States have labelled the new proposals the “Macron Packages”. Six countries, in particular, have come out against the proposal: Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Latvia, and Lithuania. These are countries in the far eastern outskirts of the EU. Their governments generally oppose restrictions on the freedom to provide cabotage services across the EU. They mainly oppose the new rules that would require international truck drivers to return to their country of residence at least once a month (Euractiv 2019). This part of the proposal is particularly problematic as it would severely limit access to local transport markets in other Member States. This regulation would impose serious limitations on the ability to conduct cabotage operations and goes against the initial objective of the European Commission to liberalise existing restrictions on free cabotage. Accordingly, the government of Bulgaria made clear that they plan to take the case to the European Court of Justice. Like the other governments that are against the proposal, the government of Bulgaria considers this requirement an illegal protectionist policy that would cause significant damage to Eastern European transport companies and their employees respectively.

The concerns from Central and Eastern European Member States of restrictions on the freedom to provide freight transport services in the EU are justified. While road freight cabotage restrictions are still in place, it is noteworthy that EU lawmakers abolished cabotage restrictions for aviation services in the EU already in 1993. The liberalisation of aviation services opened Europe’s skies for some of the largest airlines in the world, of which most are headquartered in Western Europe, including France and Germany.[5] By contrast, with the current regulation of cabotage operations, the EU and national governments designed a two-class system that privileges companies in Western Europe and discriminates against competitors from other EU Member States. The principles adhered to in aviation should be followed for road freight cabotage too. Abandoning these principles for freight cabotage just because those who stand to benefit are not Western Europeans would undermine the acceptance of EU integration in those countries whose citizens would be discriminated against by European law.

[1] See Council Regulation EEC 1841/88.

[2] See Judgement of the Court in case 13/83. 22 May 1985. In its decision, the Court found that “in breach of the Treaty the Council has failed to ensure freedom to provide services in the sphere of international transport and to lay down the conditions under which non-resident carriers may operate transport services in a Member State.”

[3] Specifically, Article 8 of the Regulation provides that every haulier is entitled to perform up to three cabotage operations within a seven days period, starting the day after the unloading of the international transport. A haulier may decide to carry out one, two or all three cabotage operations in different Member States and not necessarily the Member State in which the international transport was delivered. In this case only one cabotage operation is allowed in a given Member State to be carried out within three days of entering that Member State without cargo.

[4] 2017/0123(COD), Ordinary legislative procedure (ex-codecision procedure), Regulation, Amending Regulation (EC) No 1071/2009 2007/0098(COD) and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1072/2009 2007/0099(COD).

[5] Generally, for aviation cabotage, the United Nations agency ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) provides 9 freedoms, which allow an airline of one country to enter another country’s airspace and perform transport of passengers to and from other countries. The 8th and 9th freedoms provided by ICAO allow for cabotage operations. The EU adopted an aviation package in 1993 that completed the EU’s internal aviation market.[5] According to European Parliament (2020b), following a “a decade-long process, in the wake of the Single European Act of 1986 and the completion of the internal market: several sets of EU regulatory measures have gradually turned protected national aviation markets into a competitive single market for air transport (de facto, aviation has become the first mode of transport — and to a large extent still the only one — to benefit from a fully integrated single market). Notably, the first (1987) and the second (1990) ‘packages’ started to relax the rules governing fares and capacities. In 1992, the ‘third package’ (namely Council Regulations (EEC) Nos 2407/92, 2408/92 and 2409/92, now replaced by Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council) removed all remaining commercial restrictions for European airlines operating within the EU, thus setting up the ‘European Single Aviation Market’.”

3. Crude Protectionism in the Single Market: Lessons from COVID-19

The COVID-19 outbreak created unprecedented circumstances for the European transport sector. When national governments introduced border controls, international freight traffic between Western and Eastern Europe was close to collapsing, including countless trucks that delivered goods for Member States’ supermarkets. The European Commission soon realised that border measures targeted at foreign trucks and haulage companies do more harm than good. On 23 March 2020, the Commission published a “Communication on EU Guidelines for national border management measures to protect health and ensure the availability of goods and essential services” (European Commission 2020a). The Commission stressed, “the principle that all EU internal borders should stay open to freight and that the supply chains for essential products must be guaranteed.” The Commission also called on Member State governments to “preserve the EU-wide operation of supply chains and ensure the functioning of the Single Market for goods.”

The political developments in Germany, which immediately followed the publication of the Commission’s guidelines for transport services and border management, vividly illustrate that EU law-imposed restrictions on the freedom to provide cabotage services merely serve the purpose of protecting vested commercial interests in economically well-developed Western European Member States. Rather than improving to European workers’ rights, political realities show that the EU’s restrictions on cross-border freight transport operations are a mere reflection of crude intra-EU protectionism, which stands in opposition with the fundamental values of the European Single Market.

Germany’s Transport Ministry responded to the Commission’s call to suspend cabotage regulations and announced the decision to allow free cabotage until the end of September 2020. Germany’s authorities were required “not to punish violations of the transport law against the authorisation requirement and cabotage regulations until September 30, 2020.” It was further decreed that Germany’s Federal Office for Freight Transport and the police “abstain from enforcing cabotage laws because of the Coronavirus crisis for transports of important goods such as fuel, medical products, and food.” Yet, only seven days after the initial announcement, Germany’s Ministry of Transport cancelled the suspension of cabotage regulations and called on German police and enforcement authorities to immediately reinstate the 3-in-7 cabotage rule – despite the Covid-19 crisis.

According to Eurotransport (2020), Germany’s Ministry of Transport faced strong lobbying pressure from associations of German haulage and logistics companies. The subsequent withdrawal of the freight cabotage exemptions was part of a larger freight transport package “coordinated” with German industry associations AMÖ, BGL, BIEK, BWVL, and DSLV. The lobby groups argued that they will “ensure the security of supply for the economy and society in these times of crisis”. At the same time, the Federal Association for Freight Transport Logistics and Disposal (BGL) strongly “condemned the reduction in freight prices that was initiated in many places”.

These developments at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis in Europe showcase that the debate about cabotage restrictions, a protectionist measure by design, needs to be separated from the debate about labour rights and working conditions of truck drivers in Europe. The Mobility Package 1 was confirmed by the European Parliament’s Transport Committee in January 2020, under the auspices Germany’s MEP Ismail Ertug. Further restrictions on transport services within the EU, which a majority of the European Parliament’s Transport Committee still seems to insist on, mark an attempt to break-up Europe’s Single Market under the pretence of good intentions.

4. Economic Impacts from EU Law-Imposed Discrimination

Freight transport services within national markets dominate in Western European countries while international intra-EU transport – which includes cross-trade, cabotage, and internationally transported goods loaded/unloaded in the reporting country – prevails in most in Central and Eastern European countries. Accordingly, as will be outlined below, restrictions of the freedom to provide cross-border freight transport services within the European Single Market would disproportionately affect hauliers and drivers from Central and Eastern European countries

4.1 No Impact Assessment Provided by EU Lawmakers

Cabotage restrictions and other restrictions on the freedom to provide transport services in the EU generally impact how companies organise their services supply chains. While industry associations repeatedly raised concerns over the adverse implications for haulage companies and drivers, it is noteworthy that economic impact assessments conducted by public authorities and industry associations are scarce. This is particularly true for Western European Member States, for which impact assessments have not been conducted or are not publicly available. Moreover, concerning the latest Mobility Package 1 text, neither the European Commission nor the European Parliament conducted or commissioned a comprehensive impact assessment to assess the magnitude and distribution of impacts across the EU27.

As outlined by Macyra (2020), “[s]takeholders from industry and government are now calling to for another review of the proposals, admonishing that policymakers may eventually take decisions without having looked at the implications for the Single Market and CO2 emissions. The legislative train proceeded without an appropriate economic, social and environmental impact assessment, which stands in clear opposition to the EU’s commitment to evidence-based policymaking. Stakeholders are deeply concerned that the Package’s cabotage regulations will continue to discriminate against EU citizens who hold the wrong EU passport.” Given its commitment to its evidence-based policymaking, the European Commission’s as well as the Parliaments’ procedural behaviour stands in clear opposition to the EU’s “better regulations guidelines”.

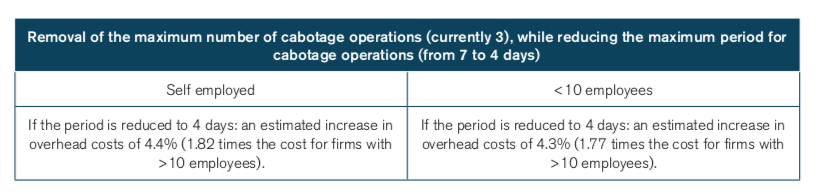

Some lessons can also be drawn from a rudimentary impact assessment commissioned by the European Commission (2017). The analysis, published in 2017, looks into some economic impacts from changes in the EU’s existing cabotage rules. However, the authors merely assessed the impacts from a hypothetical removal of the “maximum number of cabotage operations (currently 3), while reducing the maximum period for cabotage operations (from 7 to 4 days)” (European Commission 2017, p. 105). This does by no means reflect the latest Mobility Package 1 proposals. The assessment covers impacts on competition and compliance costs, including compliance costs for SMEs. A small analysis is provided on the impact in wages and employment development, however concerns over the unequal distribution of impacts among Member States have been left unaddressed.

The European Commission (2017) finds that cabotage regulations cause substantial compliance costs for companies of all sizes, with SMEs bearing the largest burden relative to their revenues (size). Responses from hauliers indicate that the weighted average estimated increase in costs for self-employed hauliers was 4.4%, compared to 4.3% for firms with fewer than 10 employees, and 2.4% for firms with more than 10 employees. Interviewed SMEs indicated that they felt the proposed measure would be helpful for SMEs, with preference that the number of maximum days should not be reduced (see Table 2). It is also found that competition in the Member States’ domestic freight transport markets would decrease from reducing the maximum number of days. Overall, the impact assessment finds that the considered policy change would result in “small price increase from small cost increases”. At the same time, it is cautioned that “any impact of the measures under consideration will be passed through to users of hauliers’ services. This is because profit margins in the sector are generally very small […] – meaning that hauliers have limited opportunities to absorb additional costs – while at the same time, demand for road haulage services is largely inelastic […] – meaning that costs are more likely to be passed through since demand will not drop significantly in response to price increases.” (p. 138) Concerning the development of employment, it is concluded that “[t]he reductions in cabotage activity under policy package 3 are not expected to have material impacts on overall employment levels in the sector. This is because cabotage represents only a small fraction of total transport activity, as well as the fact that reductions in cabotage would be compensated by increases in domestic/international activity (since transport is a derived demand, driven by changes in GDP).” (p. 143)

Table 1. Impact of changes in EU cabotage restrictions on SMEs Source: European Commission (2017).

Source: European Commission (2017).

The Commission’s 2017 impact assessment did not provide an overview of impacts at Member State level. Nor did is provide an overview of the distribution of impacts across EU Member States. Obviously, European Commission’s Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport, but also parts of the European Parliament’s Transport Committee, aimed to avert an informed political debate about the impact of cabotage and additional market access restrictions such as cooling-off periods and return-to-home policies. However, as for any other EU-imposed law, an informed debate is needed to avoid overly disproportionate outcomes among EU Member States that could result from prescriptive legislation. As will be illustrated below, the impacts of existing and additional EU restrictions of the freedom to carry freight across EU borders are very unequally distributed among the EU’s Member States.

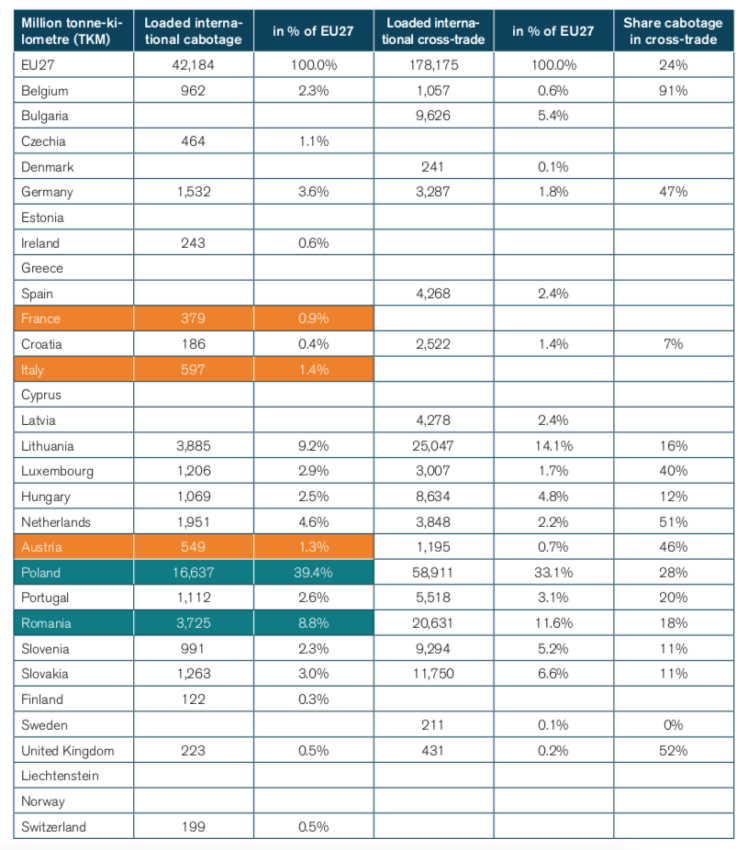

4.2. Very Unequal Distribution of Impacts Across EU27 Membership

Various reports indicate the Mobility Packages’ current market access restrictions were, to a large extent, shaped and pushed by the French government. Official Eurostat statistics for intra-EU cabotage services demonstrate that French cabotage operators would hardly be affected by the reforms proposed in the Mobility Package. As shown in Table 2, the share of French firms’ cabotage operations in total EU cabotage services amounts to only 0.9%. Very low levels are also recorded for Austria (1.3%), Italy (1.4%) and Germany (3.6%). By contrast, Central and Eastern European companies are much more affected by existing market access restrictions and would suffer most from new restrictions: Polish haulage companies account for about 40% of all EU cabotage, Lithuanian firms for 9.2% and Romanian companies for 8.8%. Even though recent Eurostat data is not available, high values have been reported by stakeholders for Bulgaria and Estonia.

Table 2. Loaded freight cabotage vs. loaded cross-border trade, in 2018 Source: Eurostat.

Source: Eurostat.

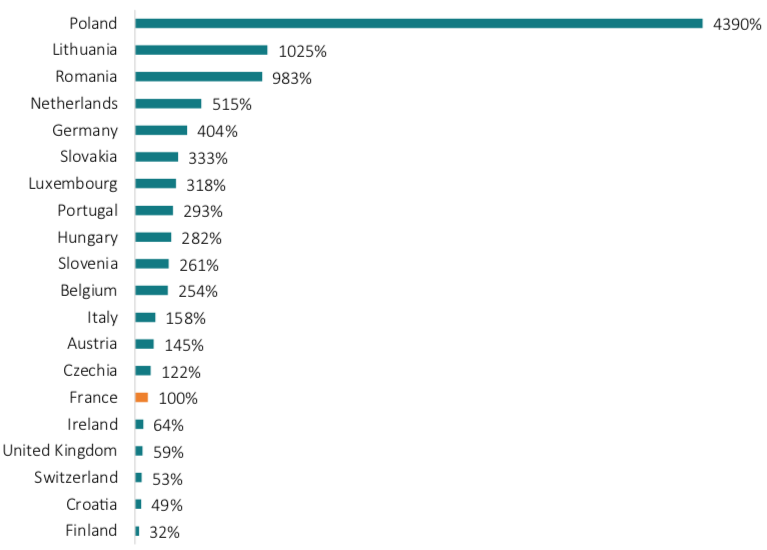

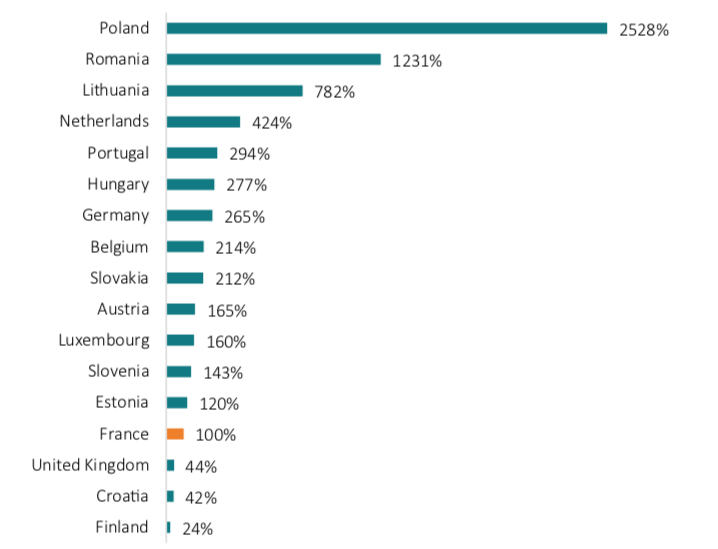

Similarly, Figure 1 outlines that the share of cabotage operations (measured in million tonnes-kilometres) provided by French haulage companies is marginal compared to that of other countries. Polish haulage companies, for example, account for 44 times more cabotage operations than French companies.

Figure 1. Share of loaded freight cabotage operations in % of cabotage operations of French haulage companies Source: Eurostat. Base values in million tonnes-kilometres.

Source: Eurostat. Base values in million tonnes-kilometres.

Above shares are reflected by the number of road freight transport companies directly affected by the market access restrictions proposed in the Mobility Package 1. Figure 2 depicts an approximation of the number of companies directly affected by EU-imposed cabotage restrictions, cooling-off periods and return-to-home policies. The estimated number of Polish (4,574), Lithuanian (519) and Romanian (1,864) companies that would directly be affected by the regulations is substantially higher than the estimated number of French (70) companies. It is also shown that, compared to France, other Western European countries show a substantially higher number of transport firms that would be directly affected EU-imposed market access regulations (for percentage numbers, see Figure 7 in the Appendix).

Figure 2. Number of enterprises potentially affected by EU cabotage regulations, total road freight transport services, 2017 Source: Eurostat. Estimations based on the total number of companies operating in road transport services by country multiplied by the country’s overall share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

Source: Eurostat. Estimations based on the total number of companies operating in road transport services by country multiplied by the country’s overall share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

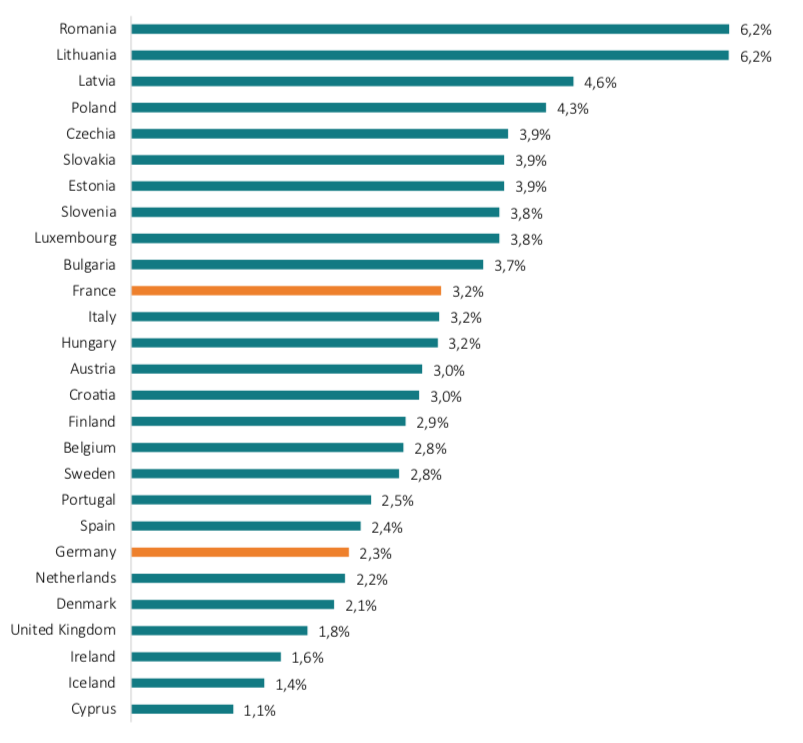

The substantial differences in companies’ actual cabotage operations are mirrored by the number of workers directly affected by market access restrictions on the EU’s road freight transport market. Generally, as outlined by Figure 3, Central and Eastern European countries have a significantly higher share of employment in overall land transport services in total employment. For example, in France, only 3.2% of all employed persons were working in land transport services in 2018, while the share was twice as high in Romania and Lithuania (6.3% each) and also significantly higher in Latvia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Estonia, reflecting differences in economic development and the structure of economic output. Due to these differences, restrictions on the freedom to provide cabotage services across the EU would indirectly affect a significantly higher share of the labour force in less developed Central and Eastern European countries than in more developed economies, such as France, Germany and the Netherlands. In the EU’s less economically developed countries, further restrictions on freight cabotage would increase pressure on wages and employment in the entire land freight transport sector as it is generally harder for low-skilled workers to find employment in other sectors of the economy. By contrast, in the EU’s more economically developed Western European countries, restrictions on freight cabotage have a lower impact on wages and employment in the transport sector as it is generally easier for low-skilled workers to find employment in other sectors of the economy.

Figure 3. Share of employment in land transport services in total employment in 2018 Source: Eurostat, NACE statistics for H49, number of employees by domestic concept. Note: for some countries, 2018 data were not available for land transport services employment. 2017 values for land transport services employment were applied for Germany, Portugal, Sweden, Italy, France, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.

Source: Eurostat, NACE statistics for H49, number of employees by domestic concept. Note: for some countries, 2018 data were not available for land transport services employment. 2017 values for land transport services employment were applied for Germany, Portugal, Sweden, Italy, France, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.

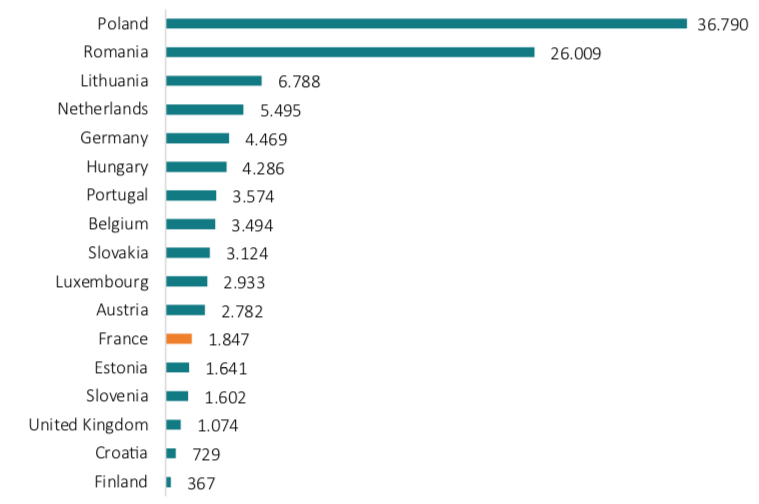

Based on the share of international cabotage services in total international freight transport in the EU, Figure 4 depicts the number of workers that are directly affected by cabotage restrictions and would be directly affected by cooling-off periods and return-to-home policies respectively. It illustrated that number of Polish workers (20,159), Lithuanian workers (6,237) and Romanian workers (9,814) directly affected by the regulations would be substantially higher than the number of French workers (797) similarly impacted (see also Figure 9 in the Appendix).

Figure 4. Number of persons employed potentially affected by EU cabotage regulations, total road freight transport services, 2017 Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

4.3. Stakeholder Assessments of Economic Impacts from the EU’s Mobility Package 1 Proposals

While EU lawmakers so far failed to provide appropriate assessments on the impacts of the proposed restrictions on the freedom to provide road freight transport services in the EU, several stakeholders expressed their views in reports and media articles. Below, we provide an overview of these perspectives.

In a written policy statement submitted on request to ECIPE, the Polish Ministry of Infrastructure generally argues, “it is universally accepted that any tariffs or barriers to trade impact unemployment negatively. And, conversely, reducing tariffs and barriers is beneficial to the marketplace and correlates positively with lower unemployment.” The Ministry considers cabotage restrictions equivalent to import tariffs. It is stated that “[n]ational restrictions on cabotage increase both the costs and environmental impact of those goods. Though justified for decades as national security measures, many cabotage regulations, particularly those affecting in-country transfers of imports and exports shipped by water, are motivated largely by protectionist concerns for local industries and employment.” (see also WEF 2013). The Polish Ministry of Infrastructure also refers to a report published by TLP and PwC (TLP/PWC 2019), which finds that “[s]tarting from 2022, regulatory changes related to the ‘Mobility Package’ may prevent Polish carriers from providing a large share of their cross-trade and cabotage services, which account for 23% of their transport performance (36% of transport performance in international transport).” With regard to economic convergence within the EU27, the Ministry states that “there are indications of convergence of labour costs [across the EU], but considerable divergences remain. [T]he professional group of heavy truck and lorry drivers is almost exclusively male and dominated by workers aged 35-64. Permanent and full-time contracts are the most common form of contracting. However, subcontracting is also a prominent and augmenting feature of the sector.” The Ministry also refers to a study on labour costs in the haulage industry performed for the Employment Committee in the European Parliament. The study indicates, “labour costs have fallen most in Greece, Portugal and Cyprus since 2008, and have risen most in Bulgaria and Romania (albeit from a very low base). These numbers indicate that salaries of the drivers converge across Europe.” (see European Parliament 2015)

The National Union of Road Carriers in Romania (UNTRR – Uniunea Nationala a Transportatorilor Rutieri din Romania) provided a detailed study on the impacts of Mobility Package 1 proposals for cabotage, cooling-off periods, and return-to-home polices. UNTRR generally highlights that the proposed measures are against the fundamental rights of EU, free movements of services and labour in the EU. The major findings of their study are as follows:

- Romania ranks third in the EU’s cross-trade road freight market in EU and on cabotage,

- export of road freight services of Romania recorded – almost 6 billion EUR in 2019 and is the largest contributor of total export of services of Romania, accounting for 23% of exports,

- returning to home country at every 8 weeks causes additional costs of 500 million EUR annually, almost a 9% share in total export of road freight services of Romania,

- mandatory returning home requires an average of 6 lost days at every 8 weeks, or 10% business loses,

- Romanian carriers operate with extremely low margins to be competitive in Europe. In order to cover the losses caused by the Mobility Package they must increase prices by 10%,

- many Romanian transporters will disappear, and multinationals will migrate to other EU countries, closer to the main markets,

- the prices of goods may grow by 2-3%, because the beneficiaries must pay by 10-20% more for road freight services,

- higher freight transport prices will be paid by final customers, i.e. European citizens,

- the Romanian road freight market will decrease by 15-20% with immediate effects on economy, including on foreign trade balance.

According to KPMG (2019), in a report commissioned by the Bulgarian carriers’ organisation, the Mobility Package 1 could significantly damage the Bulgarian transport industry by 2023 (see also Trans Info 2019 for a summary). When the study was conducted, KMPG assumed “one cabotage operation in the first three days after unloading and a subsequent cross-trade operation”. KMPG did not account for a return-to-home policy. Based on this assumption, the share of empty mileage is estimated to increase to 50%. The report outlines that in 2018 the industry in Bulgaria had a turnover of almost 3 billion EUR. Almost 13,000 Bulgarian transport companies operated in the EU in 2018. Most of them (9,600, i.e. 75%) were companies owning a maximum of 5 trucks. In total, they employed almost 42,500 employees. KPMG states that “if the Mobility Package enters into force as it stands […], 14,000 people will lose their jobs in the Bulgarian transport sector by 2023. Analysts suggest that companies which own 36% of the Bulgarian vehicle fleet will either suspend their operations or move to other EU countries.” Against this background, it should be noted that international road transport in Bulgaria is found to generate about 6% of GDP. Suspended or relocated operations would deprive many Bulgarian households of economic opportunities and impede the process of economic development and convergence.

In a recent report, the Transport & Mobility Leuven Institute (TML) looks into the latest Mobility Package 1 proposals. It is found that the proposed EU-imposed restrictions on the freedom to transport would have an extremely negative impact on cabotage operations: actual cabotage operations within the EU would shrink by 30%. TML highlights that 13 EU countries are disproportionately more exposed to the negative effects of the proposed legislation than other (Western) European countries. According to the report, the introduction of a maximum period of 4 days – even without restrictions on the number of cabotage operations – would lead to an increase in annual costs of 3.4 million EUR across the EU. The proposed cooling-off period would reduce cabotage activities within the EU by up to 31% by 2035 (by 20% if the maximum cabotage period was 5 days), with adverse consequences for competition in Member States’ national markets.

A study carried out by the Belgian Institute of Road Transport and Logistics (ITLB) in 2019 suggests that each day of cabotage cooling off could cost Belgian operators up to 24 million EUR a year. It is highlighted that Belgium is the country with the highest cabotage penetration rate (defined by the share of foreign carriers in the national transport of a particular country) in Europe (in 2016 it was 12.3%, compared to about half the figure in Germany in the same year – 6.5%). Moreover, Belgian haulage firms often carry out cabotage in neighbouring countries on return routes from international assignments. According to ITLB, each day of “freezing” would cost a Belgian carrier 679 EUR. The authors estimate that, across the entire Belgian industry, a three-day ban 72 million EUR and a five-day ban as much as 120 million EUR – i.e. half of the profits achieved by all Belgian carriers in 2017. ITLB also highlighted that Member States that are likely to benefit from the restrictions on cabotage are large, central countries such as France and Germany. Accordingly, French and German freight transport operators would generally gain more freight transport contracts as they would face less competition if cabotage became more restricted across the EU.

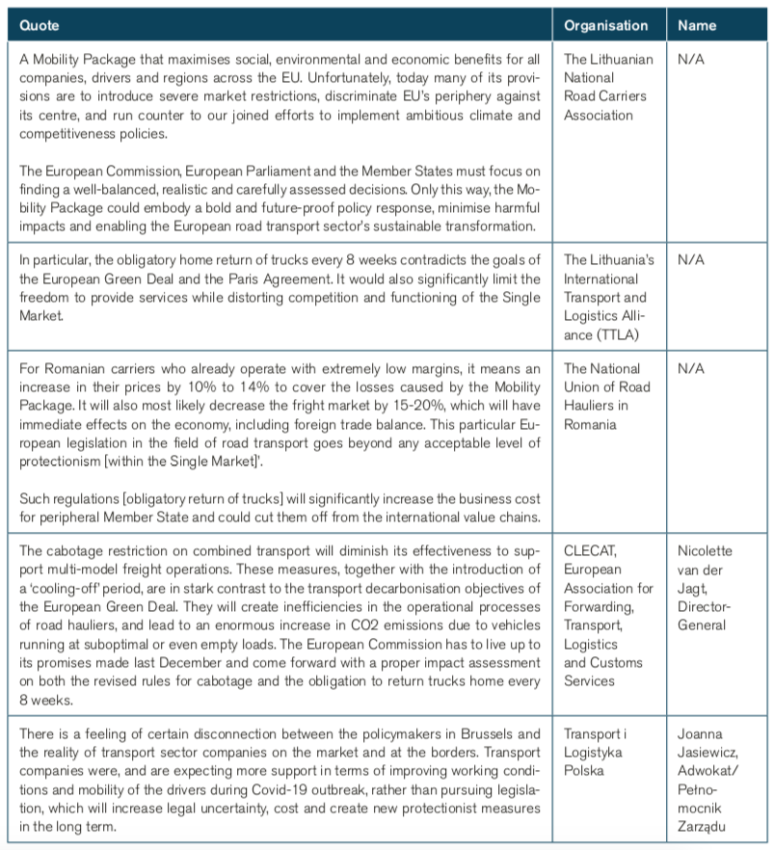

As outlined in Table 3, various industry stakeholders contacted by ECIPE highlight the adverse economic implications of cabotage rules, proposed cooling-off periods and proposed return-to-home policies. Stakeholders caution that restrictions to cross-border transport services in the EU undermine the EU’s economic, social and environmental policy objectives.

Table 3. Industry stakeholders’ perspectives Source: statements collected by ECIPE between February and April 2020.

Source: statements collected by ECIPE between February and April 2020.

5. Environmental Impacts from Rising Number of Empty Trailers

Various reports caution that the latest Mobility Package 1 would significantly inflate the number of empty trailers on European roads. As a result, the additional restrictions on the freedom to provide freight transport services would unnecessarily increase CO2 emissions in the EU.

The European Commission itself warned in December 2019 that the implementation of the latest Mobility Package 1 proposals would cause environmental harm and effectively undermine the ambitions of the European Green Deal (Politico 2019). The Commission’s Executive Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis said that the Commission “regrets” that the agreement would force trucks to return every eight weeks to their home countries, among other things, since these provisions “are not in line with the ambitions of the European Green Deal.” Such warnings were so far largely ignored by MEPs and Member State governments. Despite the Commission’s warning, the majority of the European Parliament’s Transport Committee kept pushing for cabotage restrictions, cooling-off periods and return-to-home regulations.

Truck or heavy-duty traffic is far from being emission-free. The EU itself estimates that trucks, buses and coaches are together responsible for about a quarter of CO2 emissions from road transport in the EU and about 6% of total EU emissions (European Commission 2020b). Even if buses and coaches and are deducted, it becomes clear that the emissions of trucks alone remain substantial, which is why the EU recently introduced the first-ever EU-wide CO2 emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles, setting targets for reducing the average emissions from new lorries for 2025 and 2030.[1]

Restrictions on intra-EU cabotage operations as well as return-to-home and cooling-off policies would reduce the net impact of this regulation. New return-to-base requirements and cooling-off periods would increase the number of empty trucks running across the EU, i.e. vehicle kilometres and CO2 emissions respectively. It is difficult to precisely estimate the additional CO2 emission burden that would result from these new restrictions as many factors determine the amount of loaded transport and the share of empty trailers. Based on KPMG’s (2018) estimates for empty truck runs we provide a rough estimation of additional CO2 emissions below.

In the impact assessment for the Bulgarian freight transport sectors, KMPG conducted its impact assessment on the basis of two scenarios:

- Current rules scenario: “In the simulation based on current rules we have assumed that as goods are unloaded in a Member State, the truck performs in three consecutive cabotage operation within 7 days, after which it performs cross-trade to another EU country.”

- Proposed rules scenario: “In the simulation based on the proposed changes we have assumed one cabotage operation in the first three days after unloading and subsequent cross-trade operation.”

With regard to the negative impact on the number of empty truck runs, KPMG states that “[b]ased on data provided by a sample of Bulgarian international hauliers (a total of 37 transport companies), around 53% of the additional mandatory homecomings will run empty coming back to Bulgaria, and around 38% will travel empty to the EU after the cool-off period.”[2]

KPMG finds the number of empty trucks would significantly increase because of “Mandatory Homecomings”, translating in lower economic opportunities and a substantial increase in fuel costs. The increase in companies’ fuel consumption (largely diesel) would translate to “additional CO2 [emissions] as a result of the empty runs [of] around 88,500 tonnes, which represents a 3% increase in total CO2 emissions coming from international road transport. This will increase the total greenhouse emissions generated by the transport sector in Bulgaria by 1%.”

In the proposed rules scenario, KMPG was assuming “one cabotage operation in the first three days after unloading and a subsequent cross-trade operation”. The new consensus currently struck between the EU Parliament’s Transport Committee and the Council is somewhat different, still allowing for three runs within seven days after unloading. Assuming that KPMG’s numbers for the Bulgarian haulage sector broadly reflect the changes cabotage and cross-trade operations of haulage companies that are based in other EU countries, the estimates can be extrapolated for other EU Member States and the EU as a whole. According to Eurostat data, Bulgaria accounted for only 2.2% of EU-wide “empty international freight transport” in 2018 (measured in million vehicle kilometres), which corresponds to an annual increase of 88,500 tonnes in CO2 emissions. These numbers can be extrapolated on the basis of Eurostat statistics on empty international freight transport.

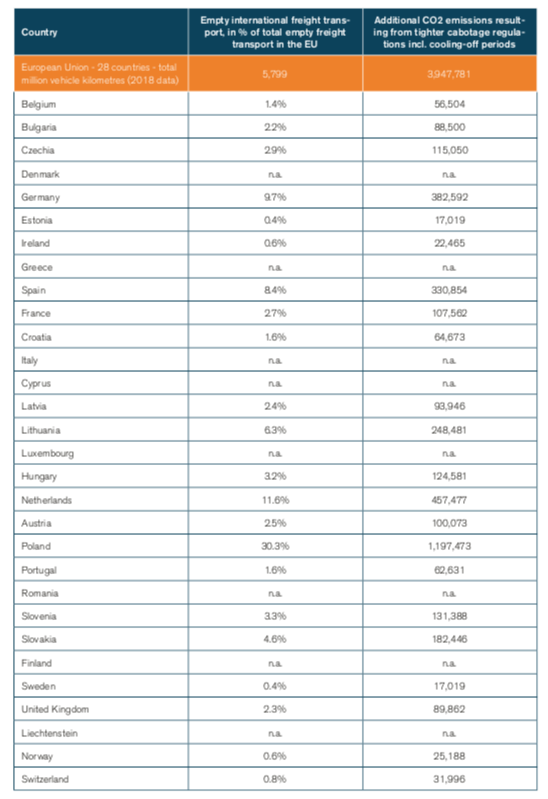

As outlined in Table 4, for the EU as a whole (including the UK), the additional CO2 emissions resulting from the proposed changes in cabotage regulations would amount to about 4 million tonnes – which according to statistics for Germany’s energy sector (Fraunhofer 2017), equals the annual CO2 emissions of 3 to 4 medium-sized hard-coal-fired power plants. Since Germany is the country where almost half of EU cabotage was observed in 2017, the largest part of the additional CO2 emissions would be emitted in Germany. This is because of Germany’s role as a transit country, connecting Eastern European countries to Western European markets for goods (see Figure 5 in the Appendix). The level of CO2 emissions would increase substantially if light-duty vehicles (small vans) would be subject to mandatory cabotage, return-to-base and cooling-off requirements imposed by EU law.

Table 4. Additional CO2 emissions resulting from tighter cabotage regulations incl. cooling-off periods Source: Eurostat and KPMG calculations.

Source: Eurostat and KPMG calculations.

[1] See Regulation (EU) 2019/1242 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 setting CO2 emission performance standards for new heavy-duty vehicles and amending Regulations (EC) No 595/2009 and (EU) 2018/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Council Directive 96/53/EC.

[2] In an updated assessment from February 2020, KPMG (2020) provides similar estimates for empty trucks from return-to-bas policies and empty trucks as result of mandatory cooling-off periods: “Based on data provided by a sample of Bulgarian international haulers (37 transport companies) and additional assumptions provided by UIH, around 46% of the additional compulsory returns of the vehicle to the Member State of establishment will run empty coming back to Bulgaria, and again around 46% will travel empty to the EU after the cool-off period.” (p. 11)

6. Concluding Remarks: Defending the Fundamental Values of Europe’s Single Market

The EU’s latest Mobility Package 1 proposals on freight cabotage and additional freight transport restrictions are a telling example of how the initial objective to create a better functioning Single Market and better working conditions within the EU was hijacked by the protectionist political agendas of some Western European governments, which kept pushing for a crude anti-Single Market Regulation to be applied by all Member States across the EU27.

The latest Mobility Package 1 proposals demonstrate that the “free movement of labour” and the “free movement of services” – two terms frequently used to defend the European Single Market – has been degraded to empty phrases. The legislative process towards the current proposals reflects a systemic challenge at EU level: national economic isolationism, i.e. vested commercial and political interests defending traditional EU and national legal institutions. Empirical data on the actual state of regulatory differences between individual EU Member States demonstrate that the Single Market did not advance during the Juncker Commission. Measured by the political objective to create a common European market – and measured by the degree of harmonisation in large jurisdictions, such as China and the US – the Single Market has actually deteriorated over the past five years.

EU policies towards a Real Single Market should not prompt a race-to-the-bottom with respect to consumer protection, working conditions or environmental standards, but result in substantially lower trade costs for businesses of all sizes, particularly SMEs that lack the financial and human resource capacities to overcome complex legal barriers, irrespective of whether they are imposed by national Member States or the EU. Data shows that transport sectors companies and workers operating from the EU peripheral Member States will be disproportionally affected by the latest Mobility Package 1 proposals. Estimates also suggest that the additional CO2 emissions would be substantial, undermining the new European Green Deal. Only the complete removal of restrictions on cabotage operations will be compatible with the Union’s social, economic and climate policies. EU-imposed cabotage laws and any further restrictions on freight transport operations lack the mechanisms needed to improve the working conditions for truck drivers in the EU. To achieve the political goal of improving working conditions, restrictions on cross-border transport services are useless. Working conditions should be addressed by working time and rest regulations, which could be harmonised across the EU.

Europe’s policymakers should recognise that existing EU-imposed cabotage regulations (introduced in 2009) discriminate against EU citizens that hold the “wrong EU passport”. Europe’s policymakers – in Brussels and the Member States – should generally strive for non-discriminatory legal treatment of European citizens. With respect to intra-EU transport services, lawmakers should not support any legal outcome that is plainly inconsistent with the Lisbon Treaty and the EU’s fundamental freedoms.

Those European lawmakers who still acknowledge the principle of non-discrimination should oppose any new attempt to break-up the Single Market. With regard to the latest Mobility Package 1 proposals, EU Parliamentarians and Member State governments should strive for a full abolition of cabotage laws to increase economic opportunities for the greatest number of Europeans and support the process of economic integration and convergence of standards of living.

Maintaining the current cabotage regulations or strengthening them would further drive apart Europe’s less economically developed regions from more developed Western European countries. It would become more rational for Central and Eastern European governments to reach out to non-EU countries in search for new economic opportunities – governments less derogatory than those of some of the EU’s well-developed core countries. Reaching out to non-EU partners would become legitimate, undermining, perhaps putting to an end, the process of EU economic and political integration.

References

Belzer (2000). Sweatshops on Wheels: Winners and Losers in Trucking Deregulation. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258848903_Sweatshops_on_Wheels_Winners_and_Losers_in_Trucking_Deregulation.

OECD (2001). Regulatory Reform in Road Freight. OECD Economic Studies No. 32, 2001. Available at https://www.oecd.org/economy/outlook/2732085.pdf.

Euractiv (2019). Bulgaria mulls taking Macron’s ‘Mobility Package’ to EU Court. Euractiv – Politics, The Capitals, 1 October 2019, Available at https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/bulgaria-mulls-taking-macrons-mobility-package-to-eu-court/.

Euractiv (2017). Western Member States demand action on low-cost truck drivers. Euractiv – Transport, 1 February 2017. Available at https://www.euractiv.com/section/transport/news/western-member-states-demand-action-on-low-cost-truck-drivers/.

Euractiv (2016). Bulc wants truck drivers to get paid a minimum wage. Euractiv – Economy & Jobs, Social Europe & Jobs, 21 April 2016. Available at https://www.euractiv.com/section/social-europe-jobs/news/bulc-wants-truck-drivers-to-get-paid-a-minimum-wage/.

Euractiv (2014). France Concerned over ‘Cabotage’ Abuses. Euractiv – Economy & Jobs, Competition, 23 April 2014. Available at https://www.euractiv.com/section/competition/news/france-concerned-over-cabotage-abuses/.

European Commission (2020a). COVID-19 – Guidelines for border management measures to protect health and ensure the availability of goods and essential services. 16 March 2020. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20200316_covid-19-guidelines-for-border-management.pdf.

European Commission (2020b). Reducing CO2 emissions from heavy-duty vehicles. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport/vehicles/heavy_en.

European Commission (2017). Study to support the impact assessment for the revision of Regulation (EC) No 1071/2009 and Regulation (EC) No 1072/2009.Final report. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/2017-04-support-study-ia-revision-haulage.pdf.

European Parliament (2020a). International and cabotage road transport. Fact Sheets on the European Union. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/127/international-and-cabotage-road-transport.

European Parliament (2020b). Air transport: market rules. Fact Sheets on the European Union. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/131/air-transport-market-rules.

European Parliament (2020c). Legislative Train Schedule: Europe on the Move and Clean Mobility Package. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-internal-market-and-consumer-protection-imco/package-eu-mobility-package.

European Parliament (2020d). Press release: Mobility package: Transport Committee backs deal with EU Ministers. 22 January 2020. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20200120IPR70630/mobility-package-transport-committee-backs-deal-with-eu-ministers.

European Parliament (2016). “Briefing: EU External Aviation Policy” European Parliament Research Service. May 2016. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/582021/EPRS_BRI%282016%29582021_EN.pdf.

European Parliament (2015). Employment Conditions in the International Road Haulage Sector. Study for the EMPL Committee. April 2015. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/542205/IPOL_STU(2015)542205_EN.pdf.

Eurotransport (2020). Gütertransportpakt geschlossen: Kabotage wird nicht gelockert. 26 March 2020. Available at https://www.eurotransport.de/artikel/guetertransportpakt-geschlossen-kabotage-wird-nicht-gelockert-11155704.html.

Fraunhofer (2017). Kohlendioxidemissionen (CO₂) von Steinkohlekraftwerken in Deutschland in 2017 [carbon emissions of coal-fired powerplants in Germany]. Available at https://www.energy-charts.de/emissions_de.htm?source=coal&view=absolute&emission=co2&year=2017.

KPMG (2020). Report on impacts of Mobility Package 1 on Bulgaria’s freight transport industry. Updated as of 28 February 2020. Available at https://freetransport.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Market-study-report_Final-version.pdf.

KPMG (2019). Report on impacts of Mobility Package 1 on Bulgaria’s freight transport industry. Available at https://freetransport.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Market-study-report_Final-version.pdf.

Macyra, N. (2020). Urgent need to review the Mobility Package 1 proposals’ says EU transport sector. 15 May 2020. Available at https://trans.info/en/urgent-need-to-review-the-mobility-package-1-proposals-says-eu-transport-sector-184971.

Politico (2019). POLITICO Brussels Playbook, presented by Deutsche Börse: Keep on truckin’? — Malta mess — Impeachment Day. 18 December 2019. Available at https://www.politico.eu/newsletter/brussels-playbook/politico-brussels-playbook-presented-by-deutsche-borse-keep-on-truckin-malta-mess-impeachment-day/?utm_source=POLITICO.EU&utm_campaign=094c90c6aa-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_12_18_06_07&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_10959edeb5-094c90c6aa-189127625.

TLP/PWC (2019). Transport of the Future. Available at https://tlp.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/pwc-transport-of-the-future-web.pdf.

TML (2020). Summary provided by trans.info article. Cabotage in the EU will shrink by 30%. A Belgian institute estimates the negative impact of the Mobility Package. 9 March 2020. Available at https://trans.info/en/cabotage-in-the-eu-will-shrink-by-30-a-belgian-institute-estimates-the-negative-impact-of-the-mobility-package-175896.

Trans Info (2019). Half of the transport companies in this country could go bankrupt with the Mobility Package. Thousands of truckers will be out of work. 17 October 2019. Available at https://trans.info/en/bulgarian-transport-companies-could-go-bankrupt-with-the-mobility-package-thousands-of-truckers-will-be-out-of-work-163386.

Appendix

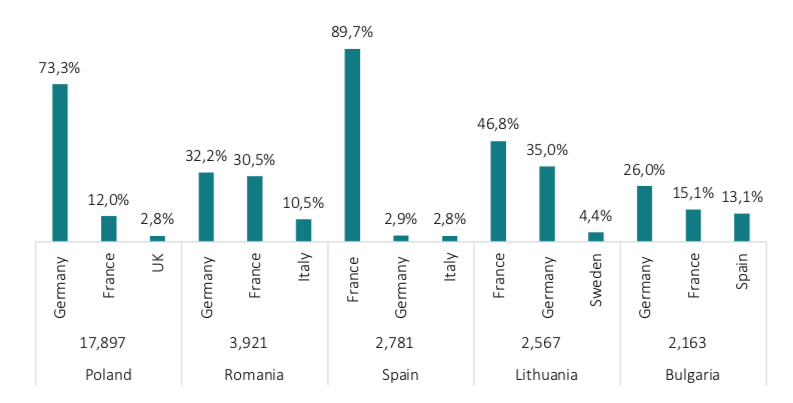

Figure 5. Top 5 cabotage performing countries and their main countries in which cabotage took place in 2017 Source: Eurostat and KPMG calculations. Measured in million tonne-kilometres (MTK).

Source: Eurostat and KPMG calculations. Measured in million tonne-kilometres (MTK).

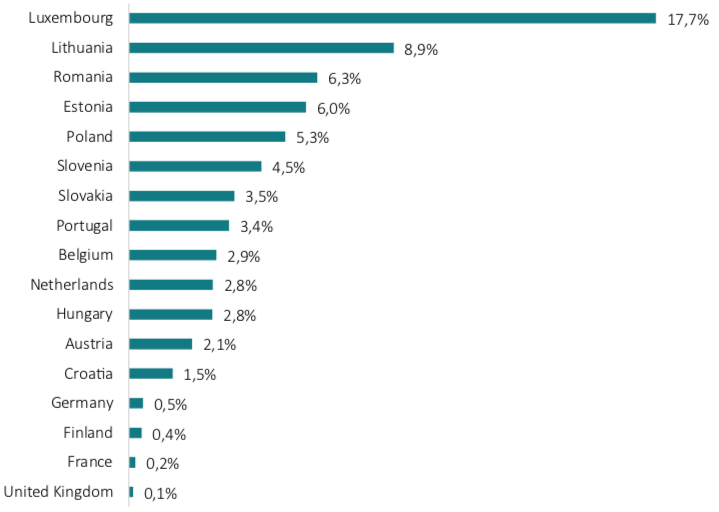

Figure 6. Share of loaded international freight cabotage in total transport, measured in million tonnes-kilometres Source: Eurostat. Note: 2017 number for international cabotage were applied for Estonia and France.

Source: Eurostat. Note: 2017 number for international cabotage were applied for Estonia and France.

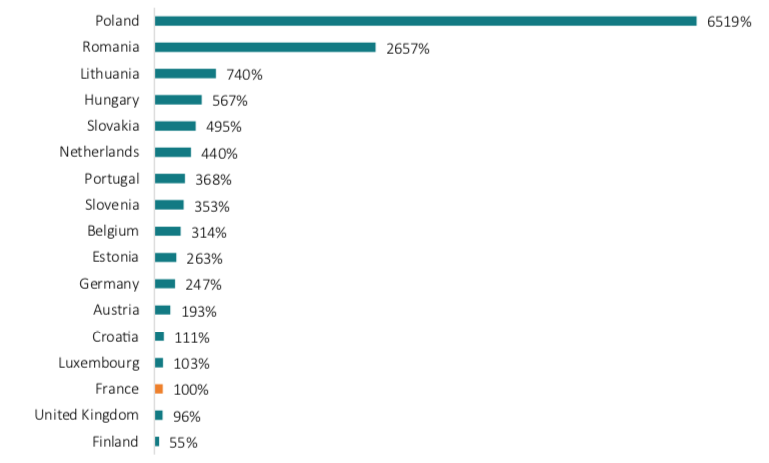

Figure 7. Estimated number of enterprises potentially affected by EU cabotage regulations, total road freight transport services, in % of estimated number of French companies conducting cabotage operations in the EU, 2017 Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on the total number of companies operating in road transport services by country multiplied by the country’s overall share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on the total number of companies operating in road transport services by country multiplied by the country’s overall share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

Figure 8. Number of persons employed potentially affected by EU cabotage regulations, total road freight transport services, in % of persons employed in French road freight transport services, 2017 Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport.

Figure 9. Number of employees potentially affected by EU cabotage regulations, total land transport services Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport and total number of employees in NACE sector H49 “land transport and transport via pipelines”, number of employees by domestic concept. Note: for some countries, 2018 data were not available for land transport services employment. 2017 values for land transport services employment were applied for Germany, Portugal, Sweden, Italy, France, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.

Source: Eurostat. Calculations based on share of loaded international cabotage services in total loaded international freight transport and total number of employees in NACE sector H49 “land transport and transport via pipelines”, number of employees by domestic concept. Note: for some countries, 2018 data were not available for land transport services employment. 2017 values for land transport services employment were applied for Germany, Portugal, Sweden, Italy, France, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.