What is Wrong with Europe’s Shattered Single Market? – Lessons from Policy Fragmentation and Misdirected Approaches to EU Competition Policy

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: EU Single Market European Union

Summary

What is wrong with Europe’s Single Market? The brief answer to that question is that it does not really exist – it is unsingle. The Single Market is in many ways a political illusion. It exists only nominally. Any company doing business in Europe faces significant barriers to cross-border exchanges within the EU, and it is these barriers that hamper companies’ ability to scale and compete internationally on the back of innovation and economic integration. We outline that Brussels and national governments need to beat the drum for eliminating policy fragmentation in Europe’s internal market and at the same time change course in competition policy to sufficiently support investments in innovation, business growth, and the adoption of advanced technologies across industries.

Major economic indicators show that Europe is caught in a protracted corporate and technology crisis. The EU has for a very long time now been tailing US corporate and innovation leadership. At the same time, competition with technology-intensive imports from China is getting increasingly intense. Europe’s underperformance is rooted in a legally fragmented internal market which is disincentivising business growth and innovation. On top of that, an outdated approach to competition policy is discouraging businesses from adopting innovation and scaling across national borders, risking that EU companies continue to lose clout and international competitiveness.

30 years have passed since the formal establishment of Europe’s Single Market. Data reveals that regulatory convergence has reversed or come to a halt in most policy areas. Recent policies for technologies and digital business models, which are key sources of cross-industry competitiveness, created new layers of regulation and legal uncertainty in EU and Member State law. Overall, EU policies have not significantly helped European companies, large and small, to do business in another Member State or use advanced technology-enabled services.

EU competition policy does not live up to its promise to “enable the proper functioning of the EU’s internal market”. Europe’s competition policy is still fragmented along national borders and largely ignorant to dynamic effects of competition, especially investments in innovation. Due to mixed legal competences, competition rules are often enforced differently by Member States’ national authorities and can be appropriated to support protectionist industrial policy ambitions.

The recently enacted Digital Market Act (DMA) demonstrates that the European Commission and Member State authorities favour protection and discretionary enforcement over innovation and economic disruption, without providing solid evidence of abusive business behaviour and consumer harm. With the DMA, the EU introduced legislation with serious ambiguities in objectives, concepts, and rules, and explicitly allows national Member States to regulate competition at their own discretion. A recent attempt by Germany’s competition authority, the Bundeskartellamt, to enforce its own rulebook for large digital companies (Section 19a of the German Competition Act) risks creating a patchwork of competition rules for large providers of advanced digital services across the EU. Local adopters of advanced digital services, particularly small businesses, that use advanced technology services to compete in their markets would be confronted with less choice and quality.

Recently imposed policies under the umbrella of European Strategic Autonomy will hardly help policymakers in their ambition to achieve “innovation and technology leadership”. The paramount task for the EU and national governments is to eliminate policy fragmentation in Europe’s internal market, accompanied by an approach to competition policy that embraces investments in innovation and business growth while accounting for the substantial value created through the adoption of innovative technologies and disruptive business models across industries in the EU.

1. Introduction

The EU is seeking the right policy framework to ensure economic competitiveness in an era of intensified technological competition. Economically, Europe faces challenges similar to other mature economies: an aging labour force, fiscal sustainability, and lack of qualified professionals, especially in science, technology, and engineering. However, the EU is at a fundamental disadvantage compared to the world’s major trading blocks, especially the US and China.

24 national languages pose a natural barrier to cross-border commerce in the EU, ultimately reducing companies’ ability to scale to improve efficiency and competitiveness. The deterrent effect of language on cross-border trade is amplified by enormous differences in horizontal and sector-specific regulations. Varying national rules for business conduct leave EU Member States, small and large, with a structural disadvantage at a time where investments, innovation and value added are increasingly generated outside EU Member States.

With its Strategic Autonomy paradigm, the von der Leyen Commission hopes to bring EU policymaking to a new level, responding to increasingly poor economic indicators and attempting to regain trust in centralised EU policymaking.[1] The overarching objective is “less dependence and more influence” in the world by creating the right policy conditions for economic, and innovation and technology leadership.[2] Most Strategic Autonomy ambitions are inherently guided by a “European Union First” impulse. But recent legislative initiatives show one thing above all: there is no serious political will to strengthen the EU’s own internal market.

EU policymakers do not get tired of insisting that EU values are superior to those in other parts of the world and EU regulation should be different from third countries. However, when it comes to Single Market policymaking, different standards apply: Europe’s “common” values are not shared by everyone. National economic interests govern the direction and shape of EU policy, driven by strong influence of large EU states, often resulting in more fragmentation rather than convergence and economic integration.

In this paper, we argue that the objective to improve the functioning of the Single Market has become a mere placeholder in EU policymaking – one meant to justify gentle policy tweaks or new layers of heavy-handed EU regulation. Indeed, most EU laws are justified by the claim to strengthen the internal market by preventing national governments from acting alone. However, most EU laws fail to create a true regulatory level playing field because of delegated implementation and enforcement competences, creating confusion and legal uncertainty for businesses and consumers.

Addressing challenges to EU competitiveness, we show that the EU’s approach to competition is in several aspects ignorant to market size and incentives for innovation, and is increasingly considered a tool for pushing protectionist industrial policy ambitions. We outline that there is need for change. Measures to promote market competition in Europe should be front and centre of any future Single Market policy. Brussels and national governments need to eliminate policy fragmentation in Europe’s internal market and at the same time change course of competition policy to sufficiently support investments in innovation, business growth, and the adoption of advanced technologies and disruptive business models across industries.

The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 analyses the state of Single Market regulation and data demonstrating that the EU finds itself in a protracted corporate and technology crisis. Section 2 also discusses political economy causes of policy fragmentation in the EU, distinguishing between political choices by EU policymakers, Member State governments, and national regulators. Section 3 is devoted to the role of competition policy in a large Single Market, the risks and likely impacts of fragmentation, and what could be done to prevent a widening of the EU’s technology and innovation gap vis-à-vis large third country markets, especially the US and, to a limited extent, China.

[1] Following reflections of the Juncker White Paper on the Future of the European Union. 1 March 2017. Available at https://commission.europa.eu/publications/white-paper-future-europe_en.

[2] European Commission (2021). Trade Policy Review – An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy, 8 February 2021. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0066&rid=7. EU External Action Services (2020). Why European strategic autonomy matters, speech by Josep Borrell, 3 December 2020. Available at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/why-european-strategic-autonomy-matters_en. European Council (2020). Strategic autonomy for Europe – the aim of our generation’ – speech by President Charles Michel to the Bruegel think tank, speech by Charles Michel, 28 September 2020. Available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/de/press/press-releases/2020/09/28/l-au- tonomie-strategique-europeenne-est-l-objectif-de-notre-generation-discours-du-president-charles-michel-au-groupe-de-reflexion-bruegel/.

2. The Shattered Single Market: Deterrent to Business Growth and Innovation

The Single Market is often said to be the EU’s greatest achievement. Indeed, since the 1980s Europe’s common market advanced in many impressive ways. Inspired by the principle of mutual recognition for goods, Brussels and most Member State capitals kept cultivating a political climate that embraces the idea of a borderless European market for goods and services, capital, and workers.

And yet, 30 years after its formal establishment, the Single Market is to the largest extent incomplete, lacking common and uniformly applied policies in EU economic and social policymaking. About a decade ago, at the time of its 20th anniversary, EU officials already recognised a crisis of the Single Market.[1] Following the conclusions of the famous Monti Report of 2010, many saw an urgent need for action to create a real European level-playing field for businesses and workers.[2] The integration fatigue, however, continued to prevail.

The lack of political willingness in Brussels and Member State capitals to move ahead with ambitious initiatives towards more harmonisation of Member State law comes as a surprise. After all, policymakers at EU and national level are concerned about innovation in the Member States and the future competitiveness of European businesses. And many in politics and business are legitimately concerned about the EU losing economic and political influence in the future – against the background of relatively poor and technological economic performance over the last decades.

Take GDP per capita, a high-level indicator for economic prosperity, productivity, and standards of living. Despite myriads of new policies for commerce and trade, the EU’s gap in GDP per capita vis-à-vis the US kept growing and growing, with increased momentum in the aftermath of the Eurozone’s sovereign debt and subsequent economic crises. Labour productivity has also grown faster in the US than in mature EU Member States, particularly as a result of lower rates of technology and innovation growth. There are many structural explanations behind the lagging rates of growth: low economic dynamism, reduced market churn, inadequate investments in infrastructure, and secular trends like population decline and rising energy costs. The combination of these and many other factors have contributed to falling rates of growth and competitiveness.[3]

If both the EU and the US continue to grow like they did in the past two decades, the EU’s income gap will substantially widen by 2035 and beyond (see Figure 1). With China, an extremely large “Single Market”, becoming increasingly developed economically, poor economic performance by EU Member States will lead to an erosion of the “Brussels Effect”, reducing the EU’s economic clout and thus its geopolitical influence in the world.[4] By far the largest part of EU underperformance in economic and technological development can be attributed to the fact that there simply is no Single Market on the basis of which European businesses, small and large, can thrive, scale and increase their competitiveness, as will be discussed below.

Figure 1: Development of income per capita, current USD, EU, China and United States

Source: World Bank. Note: Trend based on linear extrapolation based on 2000-2021 World Bank data.

1.1. The Political Choice for Fragmentation Along National Lines

A key motivation of EU policymaking, including “Digital Single Market” policies, is to reduce or prevent policy fragmentation across the 27 Member States. However, regulatory convergence reversed or came to a halt in many traditional policy areas, while new digital policies created additional layers of regulation to EU and Member State law.

The lack of integration, especially in horizontal regulation and policies for services, is the expression of a “Single Market Fatigue”, which is well-recognised and well-documented in the literature. In addition to this long-lasting problem of EU economic integration, new and typically untested policies for digital services, digital technologies, data and competition in digital markets often cause additional fragmentation of Europe’s regulatory landscape, e.g., due to vaguely formulated rules and differences in implementation and enforcement by national governments or their competent authorities.

EU policymaking has so far been characterised by an inflation of Directives which allow for national discretion in implementation and enforcement. New layers of EU regulation created an unparalleled patchwork of horizontal and sector-specific Member State laws. For businesses and consumers, the Single Market remains a complex web of business, tax, and labour regulations, which vary from country to country, creating confusion and legal uncertainties – and substantial economic (opportunity) costs: In 2016, a report by the European Parliament found that the “costs of a slow reform process and vague initiatives with uncertain time horizons in the area of e-commerce alone amount to EUR 748 billion“.[5] According to a recent Parliament study, the benefits of removing the remaining barriers to a fully functioning single market could add up to EUR 713 billion to Europe’s economy by the end of 2029. [6]

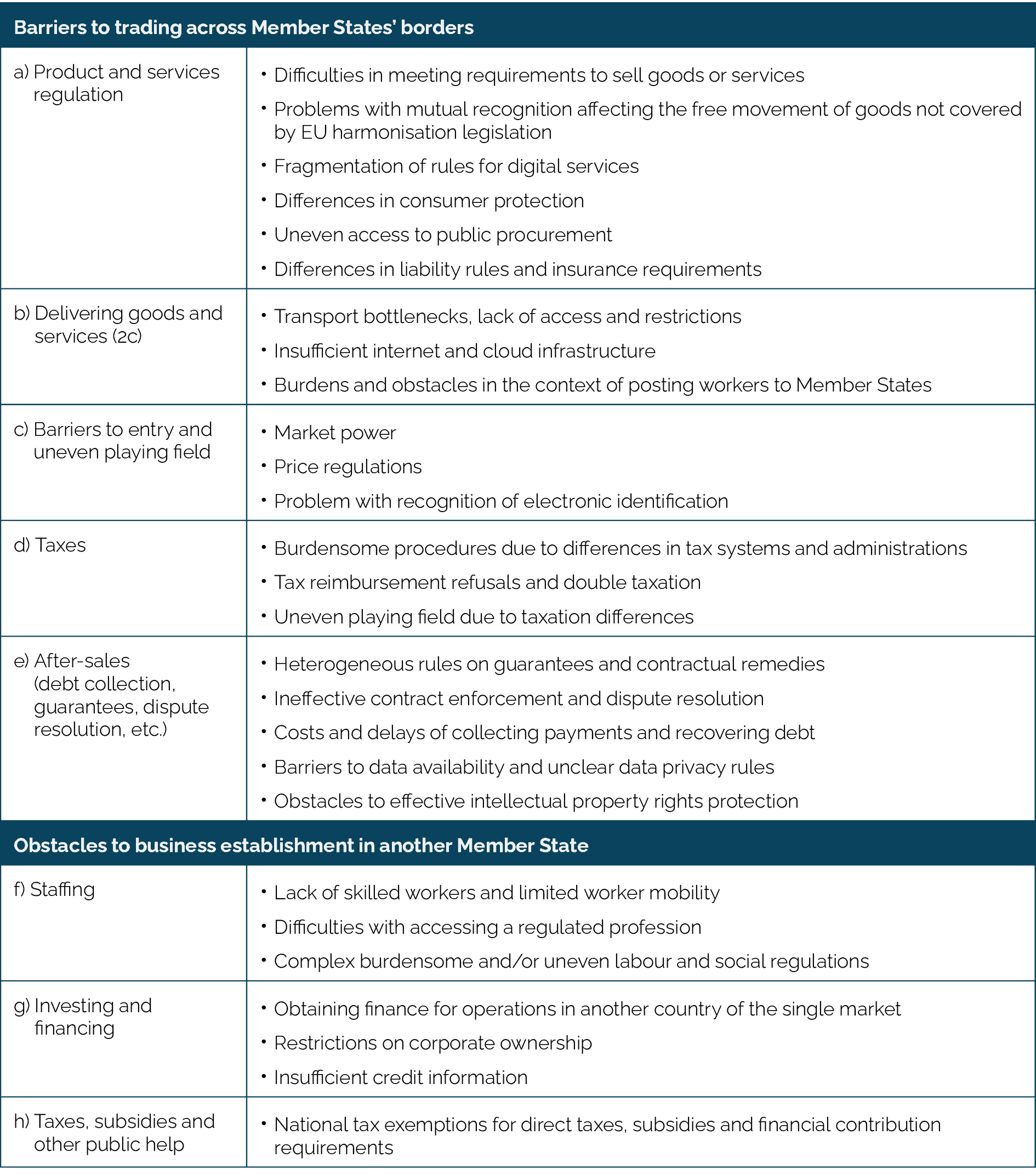

The European Commission’s latest Business Journey on the Single Market is a rich source of documented practical obstacles for businesses to trade and invest across borders in the Single Market.[7] These include major horizontal policies, such as differences in national labour market regulations, tax policies, and digital policies, as well as differences in sector-specific rules for commerce in the Member States (see Table 1). Similarly, a study undertaken by Copenhagen Economics (2020) on behalf of the European Parliament concludes that national laws together with differences in interpretation and application of EU law still restrict trade within the EU Single Market.[8] These include:

- some 6,000 national rules on professional services (with around one-quarter are only regulated in one Member State),

- requirements for national marks and certificates in manufacturing sectors,

- outdated harmonisation measures in fast-developing sectors,

- national labelling requirements for food and beverage products,

- lack of a single market for waste management, processing and shipping,

- a lack of transparency of new national rules for service provision and establishment,

- national requirements on corporate ownership,

- authorisations and local content requirements in the retail sector,

- the country-of-destination principle for VAT making online traders subject to divergent rules in each Member State they do business in, and

- diverging consumer protection rules, which is particularly problematic for online traders.

Table 1: Barriers to trading across Member States’ borders and obstacles to business establishment. European Commission (2020).[9]

European Commission (2020).[9]

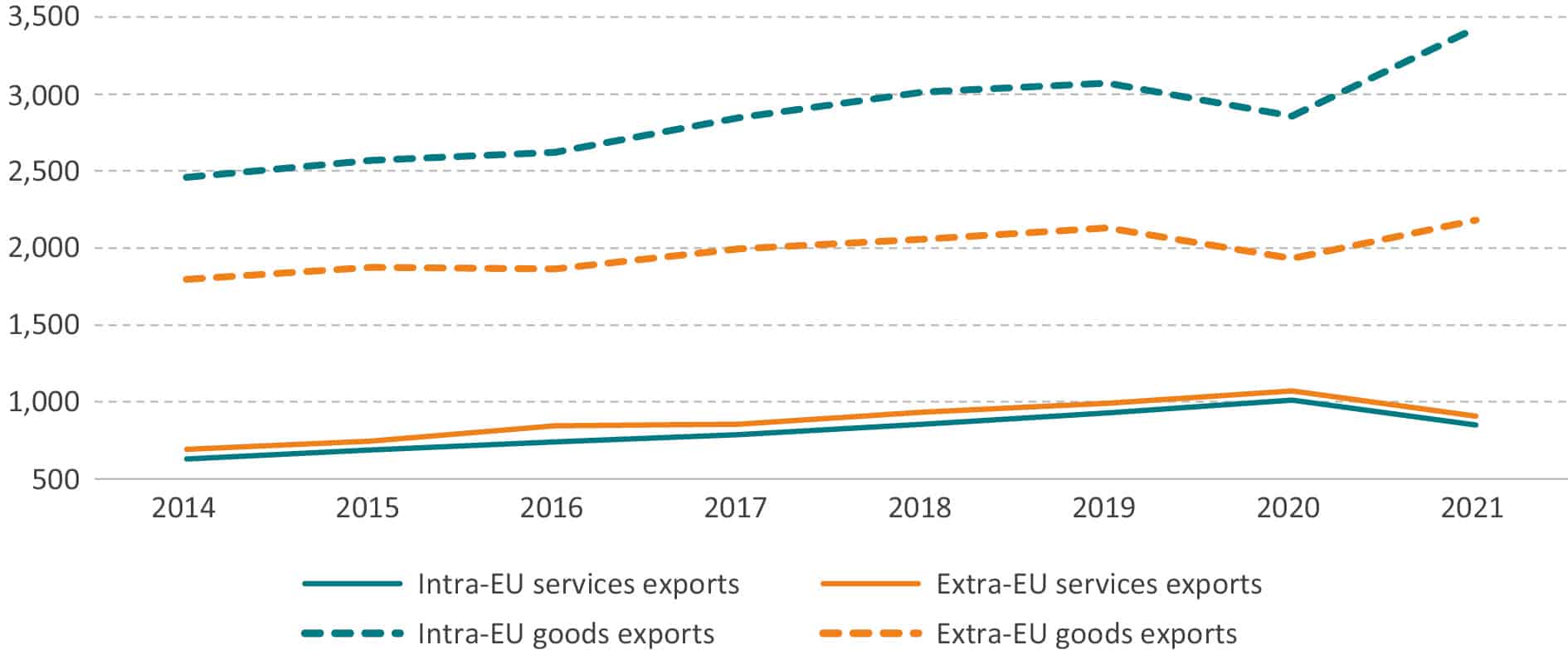

The development of intra-EU trade in services, which together account for 65% of EU27 GDP, illustrates that EU businesses are as integrated with third country partners as they are integrated with traders from other EU Member States, despite economic gravity effects, which neighbouring countries typically show, and despite having in place a “Single Market” for services. It is striking to see that intra-EU services exports show the same growth trend as extra-EU services exports (see Figure 2). Contrary to intra-EU trade in goods, which significantly outperforms extra-EU trade in goods (with non-EU countries), intra-EU services exports only kept growing in line with trends in global demand. Indeed, extra-EU services exports are higher than intra-EU services exports, indicating that selling a service to a third country is as easy or as difficult as selling a service to another Member State. In many services sectors, national policies, disproportionate regulatory restrictions, and weak competition are preventing consumers and firms from harnessing the full benefits of EU integration.[10]

Figure 2: Development of intra-EU and extra-EU goods and services exports, 2014-2021, in EUR bn Source: Eurostat.

Source: Eurostat.

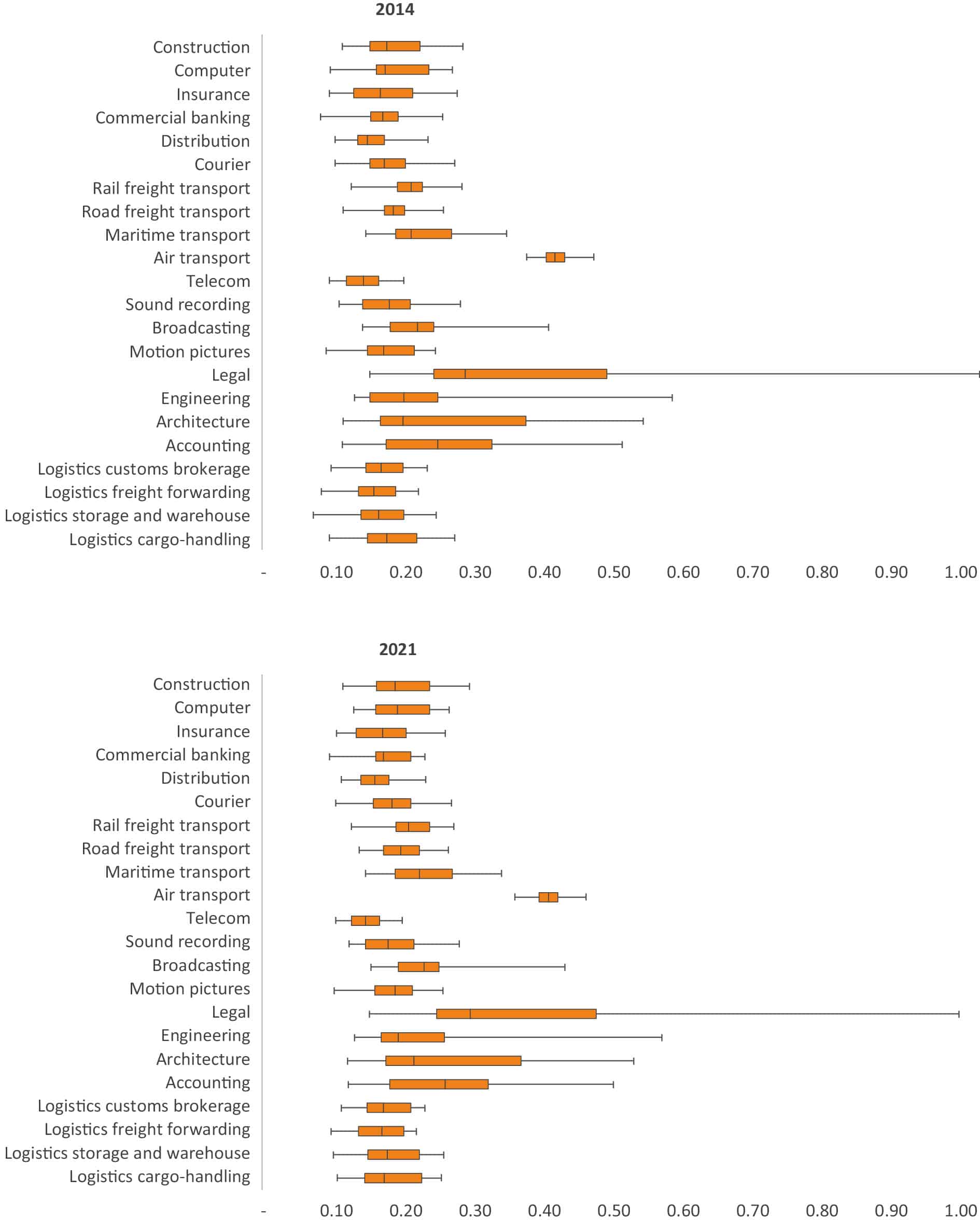

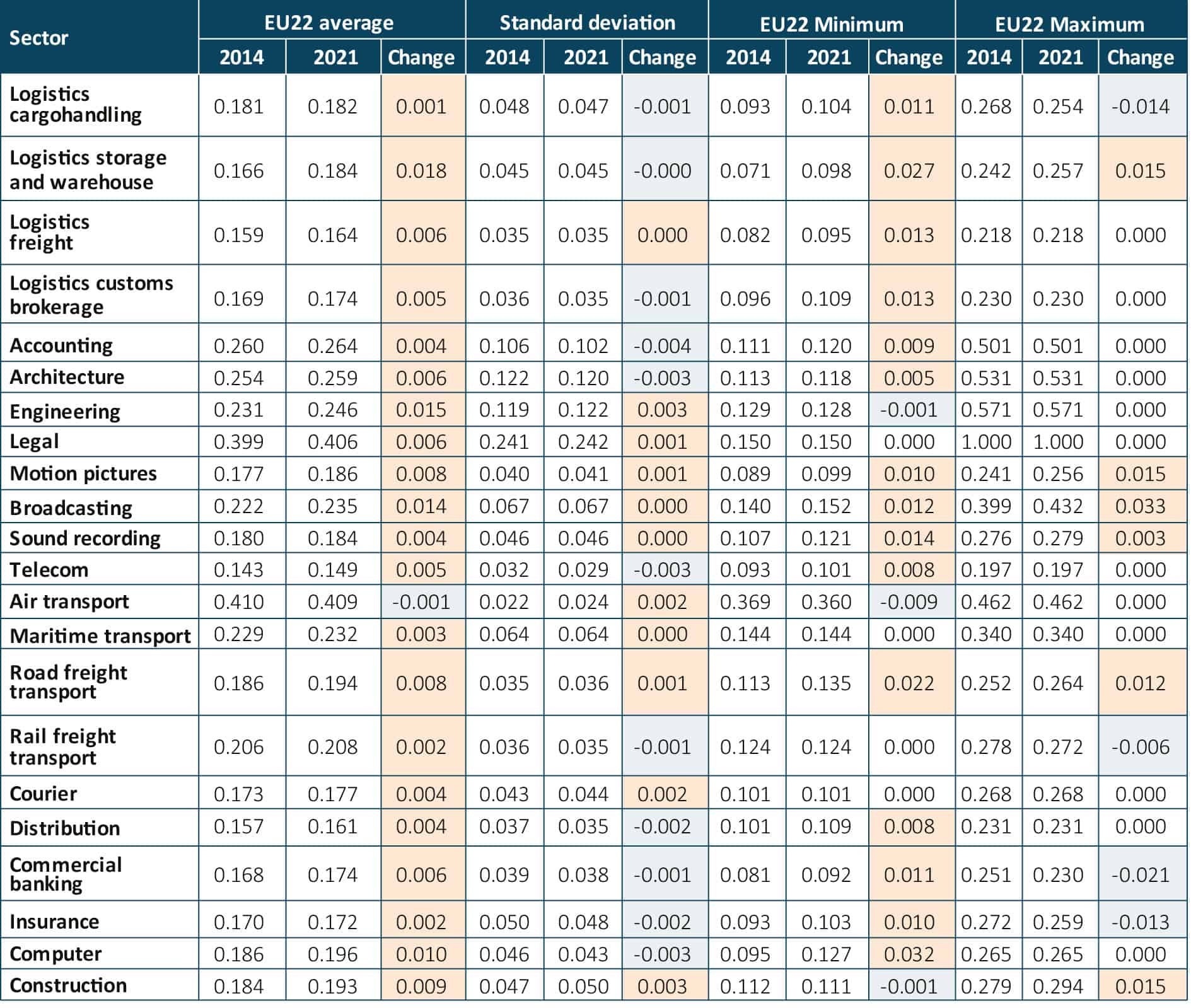

For construction and logistics to computer and telecommunications services, OECD services trade restrictiveness data demonstrates that Europe’s Single Market did not advance during the past decade. EU policy has not succeeded in harmonising the rules for services, let alone initiating a process of liberalisation and convergence. In most services sectors, Member State regulations became more restrictive, both at the lower and the upper end of the restrictiveness spectrum.

Importantly, most if not all of these barriers have been left largely unaddressed in the past two decades, nor are they considered important for achieving the EU’s Strategic Autonomy ambitions. In many services sectors, Member States are still free to determine their own regulation and how open they want to be from imports from other EU countries (see Figure 10 and Table 3 in the Annex). Take telecoms, for example: The EU currently does not have a unified mobile telecommunications market, hampering, for example, the deployment of broadband and 5G in the Member States.[11]

Additional examples are differences in access conditions in markets for regulated professions, education, broadcasting, logistics services (e.g. freight cabotage), and healthcare services. Similar trends can be observed for many product markets regulations (PMR) and, importantly, horizontal policies, such as sales taxes and VAT, corporate taxes, labour market policies, and environmental standards in the Member States.

Economic competitiveness was once a central foundation of the development of the European Union. In 1993, the European Commission of Jacques Delors set out a new course of work by launching a first White Paper focused on Europe’s competitiveness.[12] The launch of the Single Market Programme in the second half of the 1980s had expanded on ambitions to achieve higher productivity, more economic growth and better jobs by eradicating diverging Member State regulations. With the formal creation of the Single Market in 1993 came associated policies to liberalise markets and to increase competitiveness across industries. And while competitiveness may be a somewhat ambiguous concept in economic theory[13], it has indeed, at least formally, shaped most EU regulations over the past three decades. Competitiveness was long considered to increase Europeans “ability to generate wealth” and “to drive and adapt to change through innovation”, to quote the European Investment Bank.[14] Some markets such as transport services and telecoms, were comprehensively opened up, increasing competition and making companies better equipped to succeed globally.

With the Lisbon Agenda, a strategy devised in year 2000, the EU even aimed to “become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world” by 2010. However, like Single Market integration, the Lisbon Strategy has been falling far short of expectations.[15] The Lisbon Strategy was followed by the EU2020 strategy, a political programme that no longer aspired to the Lisbon goal of making Europe the most competitive economy in the world. Surprisingly, the ambition to deepen the Single Market has become a footnote in this new policy direction. It is the first time since the early 1990s that EU does not currently have a comprehensive ambition for deepening the Single Market.

At the same time, with new programmes to ail and converge Europe’s crisis economies, the EU established in 2010 processes and instruments like the European Semester and Country-Specific Recommendations – policies that tied some competitiveness reforms to larger macroeconomic concerns. And these programmes also heralded another qualitative shift: they gave much greater weight to economic reforms in the Member States rather than at the EU level. With the establishment of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) in early 2021, the European Commission launched another program towards increasing competitiveness. The aim is to raise funds to help Member States address the challenges identified in “country-specific recommendations” under the European Semester framework.[16]

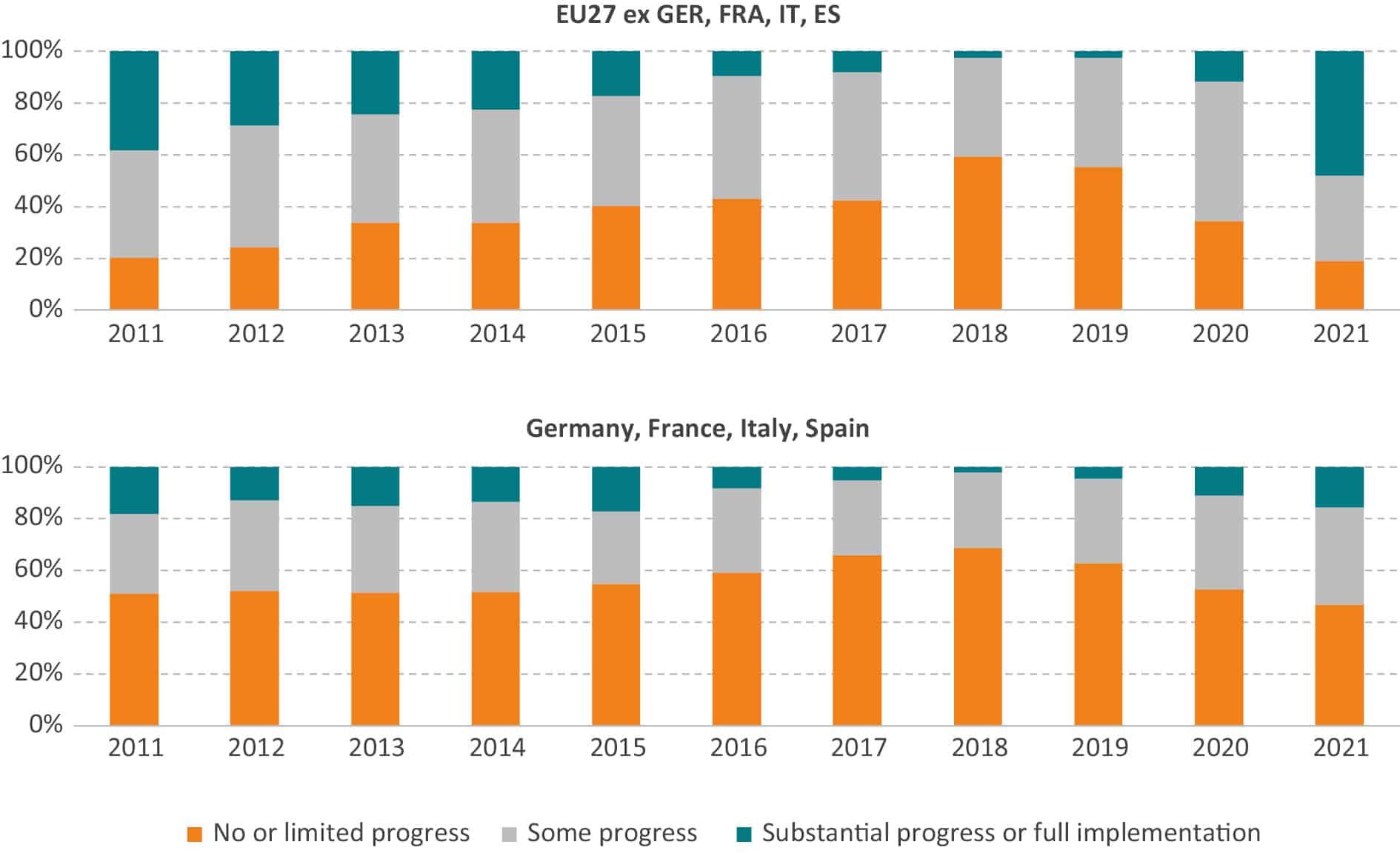

Unfortunately, these measures will hardly help to eliminate the structural disadvantages in Europe’s common market. A major problem, as outlined by Figure 3, is that EU Member States have a very poor record of delivering on country-specific recommendations. In fact, Member States’ implementation rate has dropped substantially over the past decade. Depending on how implementation is measured it has reached all-time lows, especially in larger EU Member States.

If Europeans were to have a Single Market, they could benefit of not just economies of scale for competitive companies to flourish, but also a vibrant ecosystem of companies where competition and market specialisation leads to higher productivity and competitiveness, and greater economic prosperity respectively. However, the importance of creating a real Single Market has been subdued in recent years. A real EU Single Market would make sure that there are no internal barriers to those industries that drive economic modernisation and technological progress which are in many cases service sectors. It would allow companies to invest and scale more easily and also increase Europeans’ ability to access cutting-edge technologies and new business models – with overall positive implications on long-term competitiveness, economic renewal, and economic convergence.

Figure 3: Implementation rates of country-specific recommendations, by year Source: Country-specific recommendations´ (CSR) database of European Commission (2023).[17] Note: no progress indicates that a Member State has not credibly announced nor adopted any measures to address the CSR. Limited progress indicates, for example, that a Member State has announced certain measures, but these only address the CSR to a limited extent or presented legislative acts in the governing or legislative body, but these have not been adopted yet and substantial further work is needed before the CSR will be implemented.

Source: Country-specific recommendations´ (CSR) database of European Commission (2023).[17] Note: no progress indicates that a Member State has not credibly announced nor adopted any measures to address the CSR. Limited progress indicates, for example, that a Member State has announced certain measures, but these only address the CSR to a limited extent or presented legislative acts in the governing or legislative body, but these have not been adopted yet and substantial further work is needed before the CSR will be implemented.

1.2. Impacts of Policy Fragmentation in the EU

Countless studies confirm that regulatory complexity is challenging for any business, especially start-ups and SMEs. For example, the SME Envoy Network highlights that “the Single Market is neither perfect nor complete”. Member State law is characterised by an increasing number of new regulations, overlapping policies escalating the complexity of EU and Member States’ legal frameworks. Each year, as noted by the Network, “the amount of national technical regulation keeps piling up which makes it more difficult for SMEs to expand their activities across Europe. At the European level, SMEs also experience confusion from partially overlapping rules. This means that SMEs do not necessarily know which rules apply to them – they simply do not understand which rules to follow.”[18] More generally, unclear rules together with differences in national implementation and enforcement have a negative impact on intra-EU trade, and reduce businesses’ ability to innovate, attract investment, and scale beyond Member States’ borders.

The following sections discuss in more detail obvious impacts of policy fragmentation on business formation and growth, cross-border trade, productivity, and competitiveness within the EU.

1.2.1. Business Formation in the EU and the US

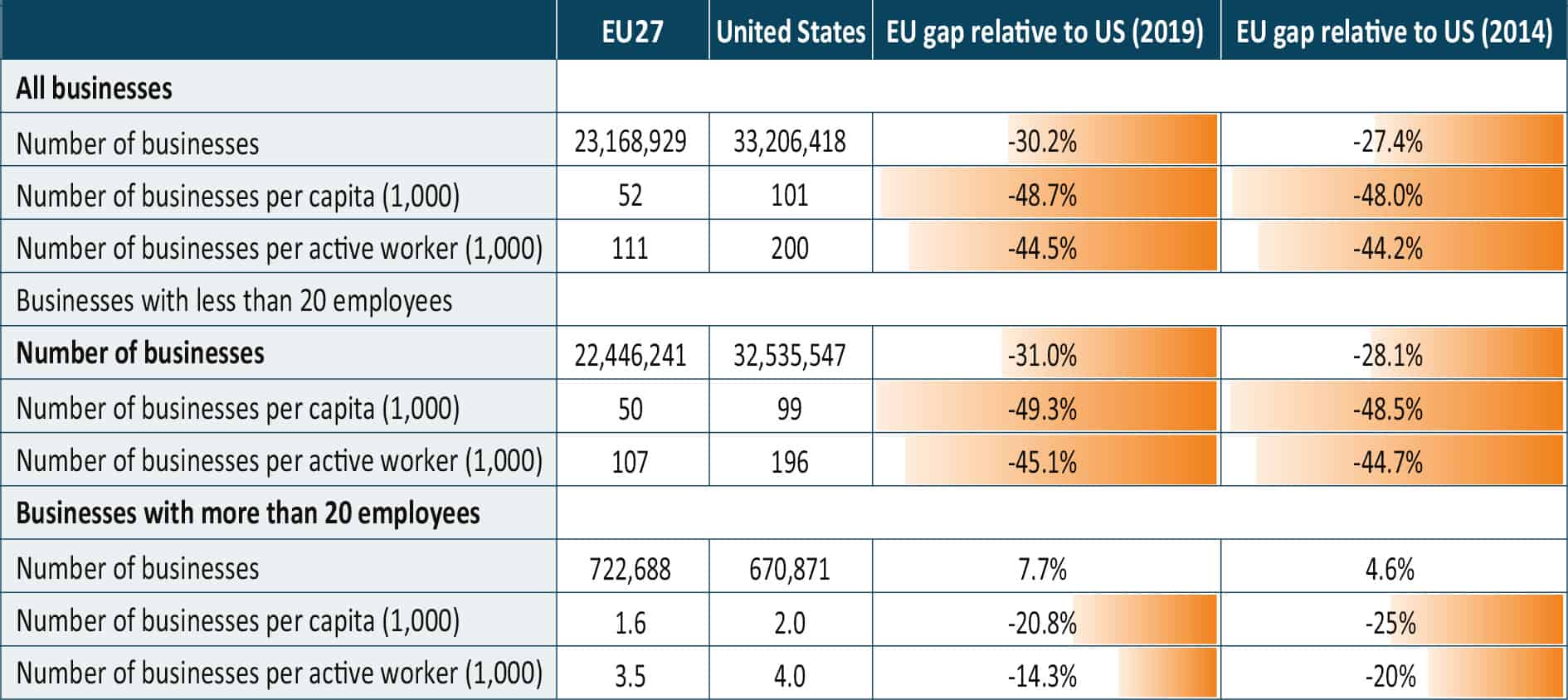

In addition to differences in language, policy fragmentation has an impact on business formation and especially small businesses’ ability to grow across borders.[19] Business statistics indeed demonstrate that despite a much smaller labour force, the US is home to a much higher number of businesses than the EU. The number of businesses in the US is twice as high as in the EU.

The EU’s deficit in the absolute number of established businesses relative to the US was 30% in 2019, increasing from 27% in 2014. It amounts to close to 50% on a per capita basis. In other words, the number of businesses per capita in the US is twice as high as in the EU. The EU’s deficit in SMEs with less than 20 employees is even higher, increasing from 48.5% in 2014 to 49.3% in 2019 (see Table 2). Due to differences in the definition of large companies, it is difficult to depict precise trends and patterns for large and very large businesses. However, data suggest that the average number of employees of a large US company (300 employees or more) is about twice as high as the average number of employees of a large company that is based in the EU (companies with 250 employees or more), indicating that it is much easier for US companies to scale than for companies in the EU.[20] Adding EU policy fragmentation, it does not come as a surprise that the number of European scale-ups is still less than a third of those in the US.[21] Europe is expected to face a large and growing corporate performance challenge, reflected by lower productivity, lower profit margins, lower investments, and less tech creation compared to US counterparts.[22]

The obvious lesson for EU policymakers is that the lack of harmonised regulations is not helping the EU keep pace with US business creation, business growth, and competitive and innovation dynamics. Similar considerations apply for economic and technology dynamics in China, whose GDP will be more than twice as high as EU GDP in 2050.[23]

Table 2: The EU’s “Business Gap” vis-à-vis the US Source: Eurostat and US Census. Eurostat data taken from the annual enterprise statistics by size class for the entire business economy ex financial and insurance services. US Census data extracted from the Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) and US Non-employer Statistics (NES) databases. Eurostat data include micro businesses (0-9 employees). NES data represent businesses that are reported to have no paid employees.

Source: Eurostat and US Census. Eurostat data taken from the annual enterprise statistics by size class for the entire business economy ex financial and insurance services. US Census data extracted from the Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) and US Non-employer Statistics (NES) databases. Eurostat data include micro businesses (0-9 employees). NES data represent businesses that are reported to have no paid employees.

1.2.2. Business Growth in the EU and the US

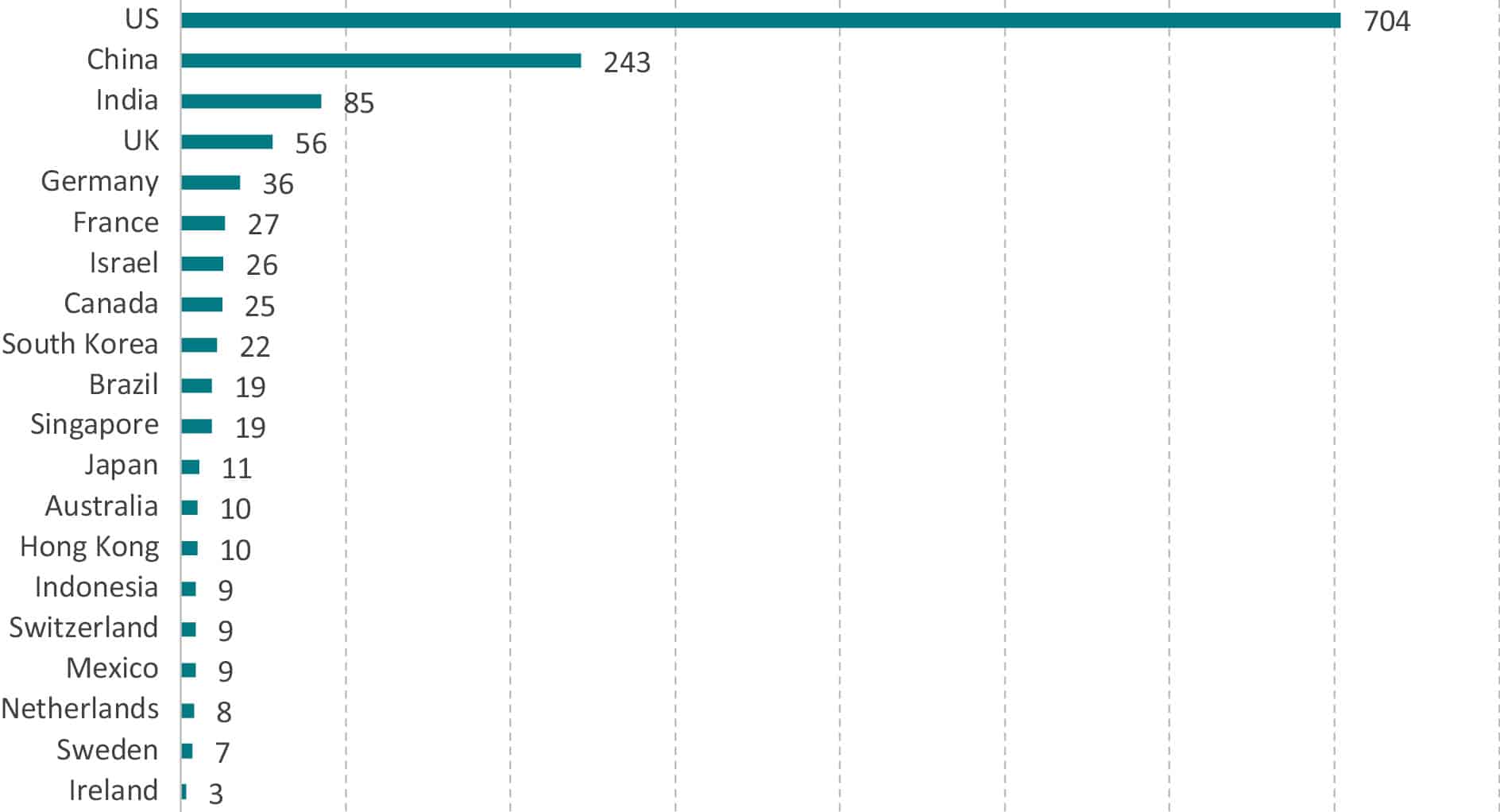

Corporate data related to innovation and business growth indicates that the EU is also underperforming with regard to companies’ ability to scale an EU-headquarter company whose business model has proven to be successful in its home market. As concerns the number of “native” unicorns with valuation of USD 1 billion, as of end 2022, the US had the highest number of unicorns (704), which China ranking second (243 unicorns), and India ranking third (85 unicorns). The UK ranks fourth with 56 unicorns, while Germany, France, the Netherlands, Sweden and Ireland lag behind in the lower ranks (Figure 4).

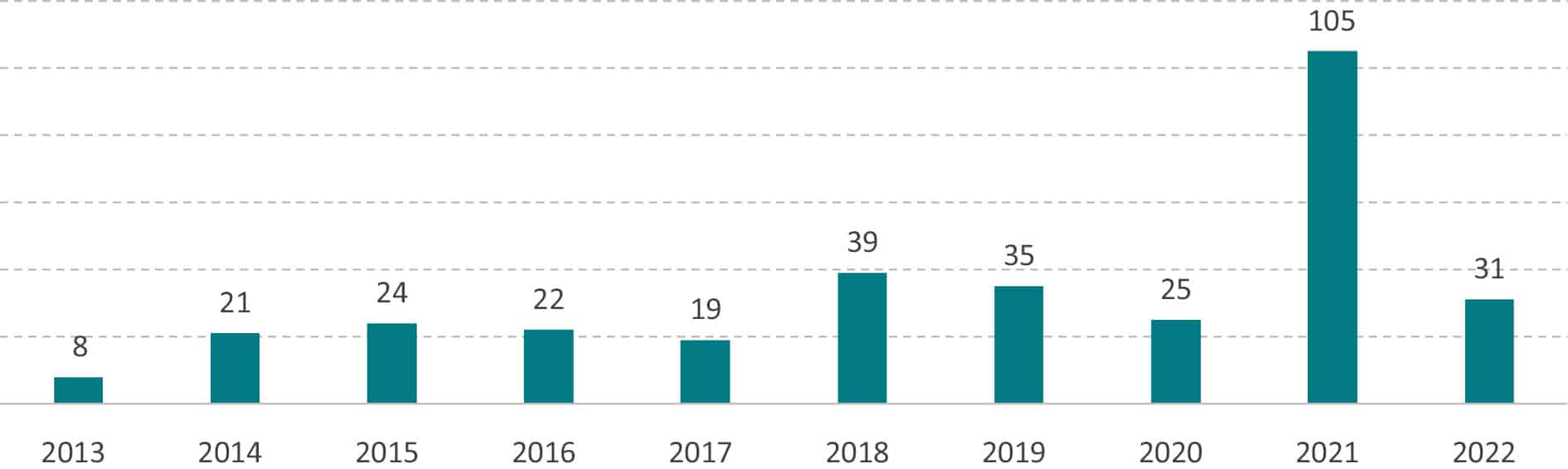

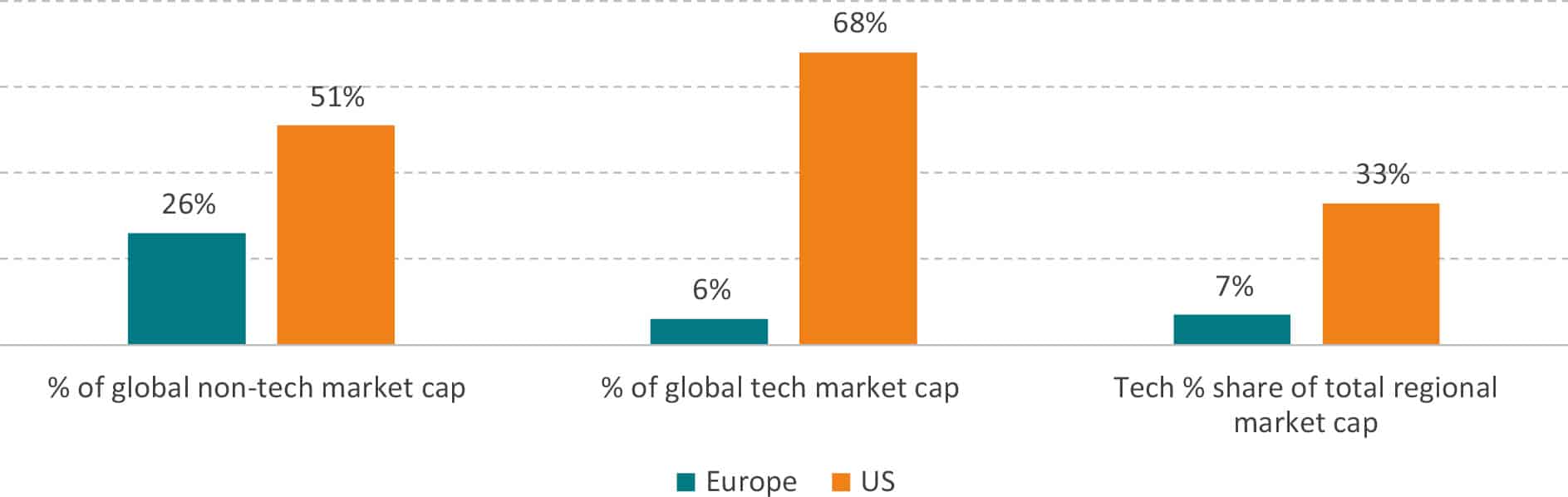

It is worth noting that the US has about twice as many unicorns compared to China and India combined, and about twice the number compared to Europe, pointing to structural advantages in terms of language and a conducive regulatory landscape. By contrast, even though 2021 saw a record number of new unicorns emerging from Europe (due to favourable market conditions in late-stage growth investments)[24], on average only 25 companies with a valuation of USD 1 billion emerged in Europe annually over the past 10 years (see Figure 5). Europe’s underperformance is also reflected in asset market capitalisation ratios, reflecting investors’ expectations about the robustness of new business models and business growth respectively. At the end of 2022, EU technology companies only accounted for 7% of Europe’s total market capitalisation. In the US, by comparison, technology companies accounted for 33% of total regional market capitalisation across all industries (see Figure 6).

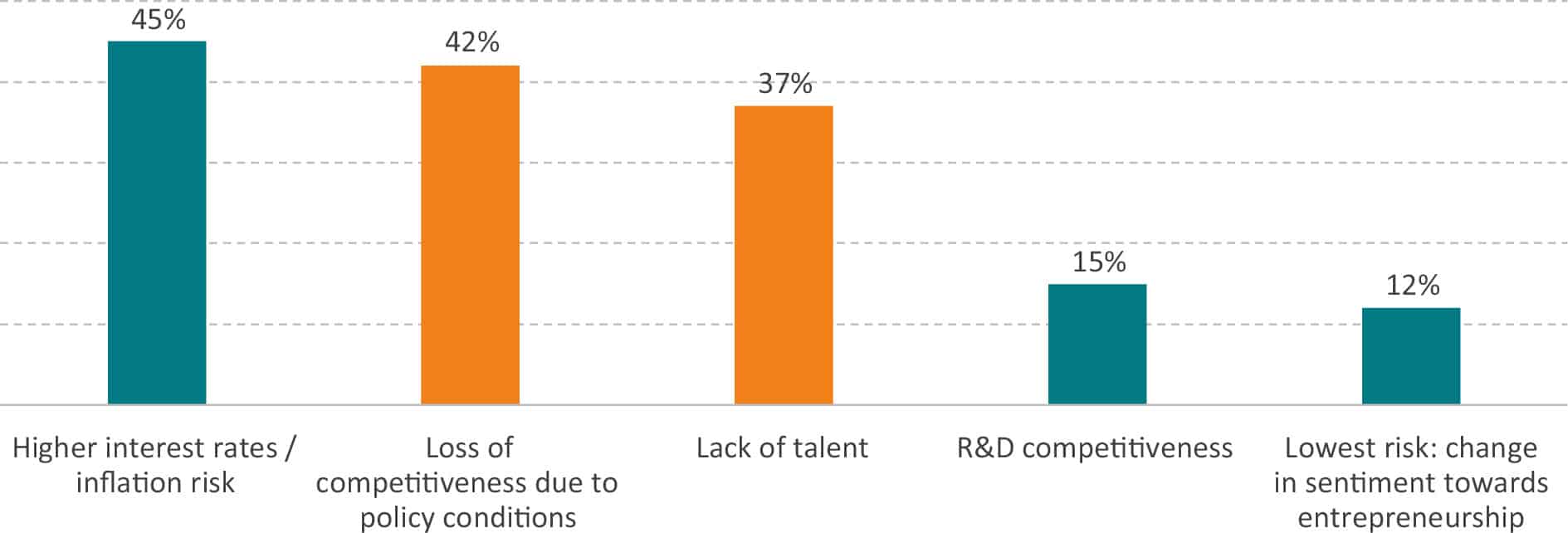

Survey data indicates that start-up founders and financiers are not concerned about Europe’s research and development environment. Equally few are concerned about a lack of entrepreneurship in Europe. The greatest risks that founders and financial partners face are challenges related to (EU and national) government responsibilities and initiatives, and here essentially, monetary risks (inflation), legal uncertainty due to new regulation for products, services and technology, and the availability of adequately skilled professionals (see Figure 7).

Figure 4: Number of Unicorns worldwide with valuation of USD 1 billion, by country, as of November 2022 Source: Finbold (2022).[25]

Source: Finbold (2022).[25]

Figure 5: Number of new USD 1+ billion European tech companies by year Source: Atomico (2022).[26]

Source: Atomico (2022).[26]

Figure 6: Share of global non-tech and tech market capitalisation (in %), Europe versus the US Source: Atomico (2022).[27] Estimations based on S&P Capital IQ Platform, as of date 31 October 2022, for illustrative purposes only.

Source: Atomico (2022).[27] Estimations based on S&P Capital IQ Platform, as of date 31 October 2022, for illustrative purposes only.

Figure 7: Major macro risks that could lead to an overall slowdown of VC activity in Europe over the next 5 years Source: Atomico (2022).[28] Note: survey respondents include company founders and venture capital professionals.

Source: Atomico (2022).[28] Note: survey respondents include company founders and venture capital professionals.

1.2.3. Europe’s Substantial Technology and Productivity Gap

European companies are to a substantial extent lagging behind global leaders in technological development, commercial innovation, and international competitiveness. This gap can be attributed to markets for products and services that are organised along Member States’ national lines. Structural determinants of lagging productivity and competitiveness include a range of sector-specific and horizontal “cross-sectoral” policies, leading to a strong home-market bias in most Member States. As a result, market churn, especially in Euro Area countries, is low – and behind comparable economies like the US. The entry and exit of firms in European markets are held back, leading to lower competitive dynamism and, as a result, misallocation of resources.[29] Also, small companies are not growing as fast as they could.[30] And too many incumbents in the EU are not facing enough competition, occupying markets that are less susceptive to firm and product innovation, and the adoption of digital technologies.[31]

A high-level view on productivity growth, based on data mined by the ECB, reveals that Europe’s large and diverse manufacturing sector, for a long time the EU’s economic backbone, does not contribute much to productivity growth anymore.[32] While this is also true for the US, US productivity growth has been driven substantially by the ICT sector, which, contrary to manufacturing, experienced much higher cumulative growth rates in the recent past. At the same time, the manufacturing sector plays a much less important role in US productivity growth, with a contribution smaller than that of the EU, and declining over time.

While it is striking that US productivity growth is substantially higher in sectors with high technology-intensity, within the EU new EU Member States, typically smaller countries with less mature markets and fewer incumbent businesses, show the highest productivity growth rates in both low- and high-technology sectors. In other words, “productivity growth in high-technology sectors in the EU27 is entirely driven by developments in the EU catch-up economies.“[33] This does not necessarily come as a surprise since most Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries that joined the EU at a relatively late stage undergo a process of economic development typically characterised by higher productivity and income growth rates than economically more mature economies. However, small economies are at the same time much more reliant on economic openness and technology-driven services imported from abroad. As noted by the ECB, the economic catch-up process of new EU Member States hinges on technology diffusion that is based on “rapid technology adoption facilitated by their involvement in international trade”.

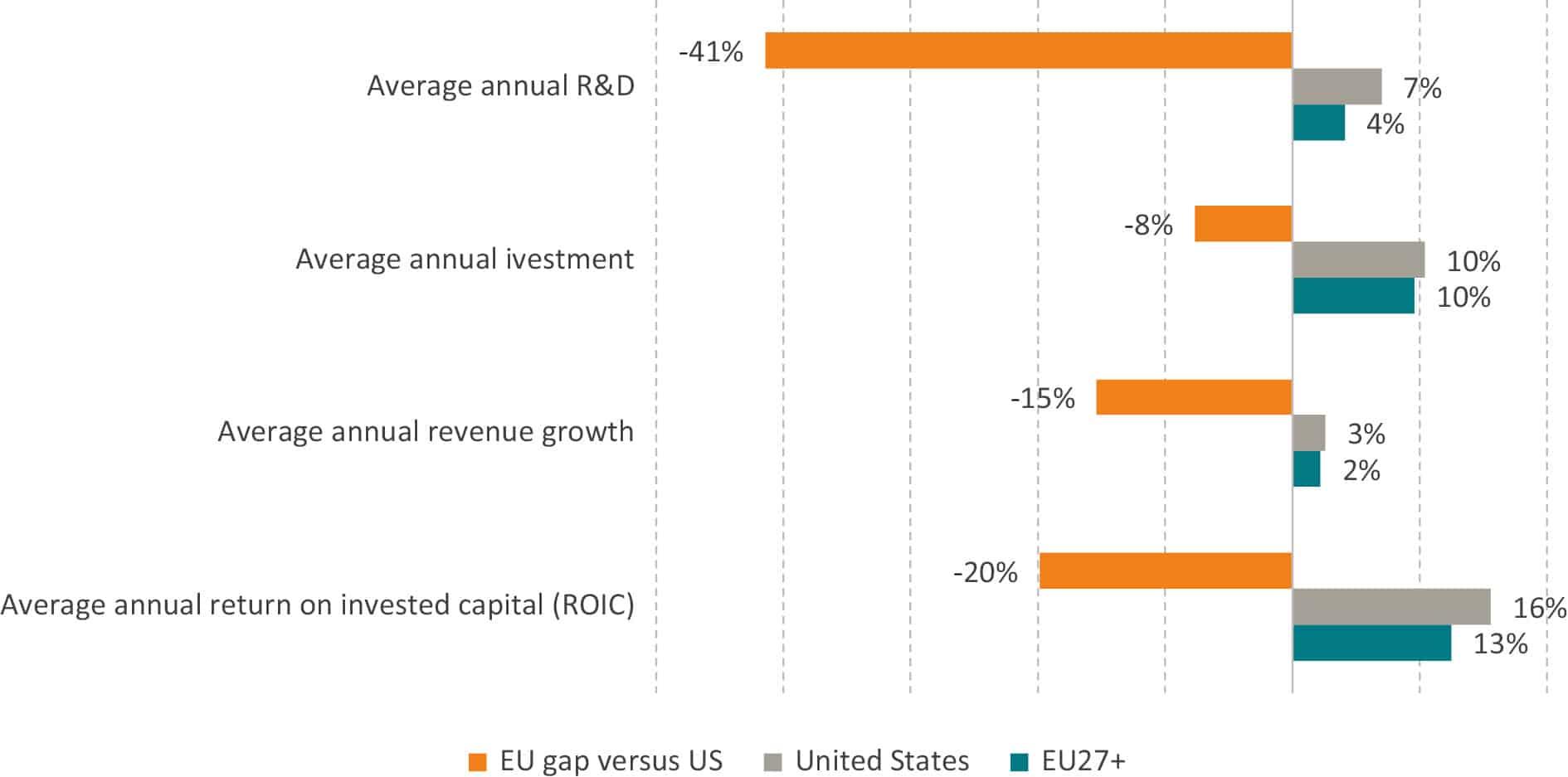

Corporate data reveals that EU’s underperformance in technology development and international competitiveness is largely caused by European businesses struggling to successfully grow and invest in and beyond the EU. A recent analysis of corporate data by conducted by McKinsey (2022) shows that between 2014 and 2019, large European companies with more than USD 1 billion in annual revenue were on average 20% less profitable than their US counterparts. Also, European businesses’ revenues have grown 40% less than those of US companies, and European businesses spent about 40% less on corporate R&D (see Figure 8).[34]

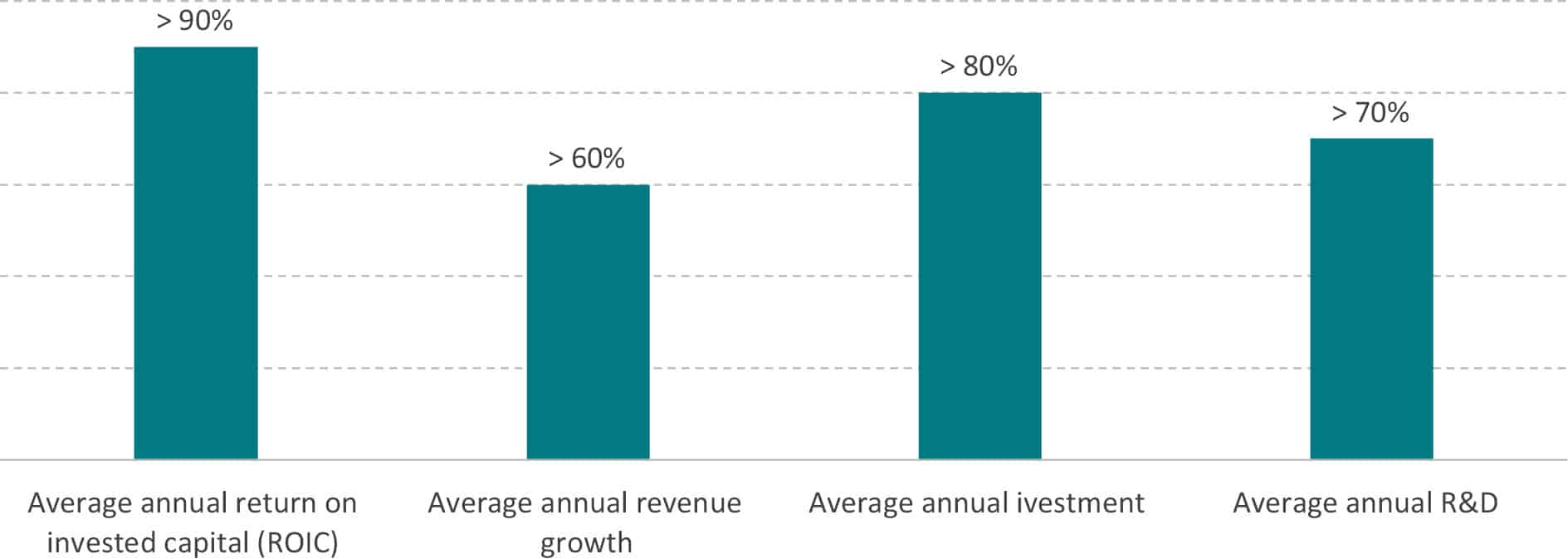

It is explicitly highlighted that such remarkable underperformance cannot be merely attributed to a few “US superstar companies” in computer and digital services industries. Indeed, the largest past of EU corporate underperformance in EU Member States can be attributed to underperformance in a broad spectrum of technology-creating (sometimes called transversal or general purpose technologies) industries, including ICT and pharmaceuticals, which “together account for more than 90% of the return on invested capital gap, over 80% of the gap on capital expenditure relative to the stock of invested capital, more than 60% of the revenue growth gap, and over 70% of the R&D intensity gap“ (see Figure 9).[35]

Figure 8: Europe’s technology and corporate performance gap vis-à-vis the United States Source: McKinsey (2022). Weighted average, 2014–19, % (companies with > USD 1 billion in revenue). EU27+ = EU27 plus Norway, Switzerland, and the UK. Average annual return on invested capital (ROIC) = NOPLAT/invested capital (NOPLAT = net operating profit less adjusted taxes). Average annual revenue growth = change in revenues. Average annual investment = capital expenditures / invested capital. Average annual R&D = R&D spending/revenue, top 2,500 R&D spenders.[36]

Source: McKinsey (2022). Weighted average, 2014–19, % (companies with > USD 1 billion in revenue). EU27+ = EU27 plus Norway, Switzerland, and the UK. Average annual return on invested capital (ROIC) = NOPLAT/invested capital (NOPLAT = net operating profit less adjusted taxes). Average annual revenue growth = change in revenues. Average annual investment = capital expenditures / invested capital. Average annual R&D = R&D spending/revenue, top 2,500 R&D spenders.[36]

Figure 9: Explaining the gap: contribution of tech-creating industries of US outperformance relative to the EU Source: McKinsey (2022). Weighted average, 2014–19, % (companies with > USD 1 billion in revenue). EU27+ = EU27 plus Norway, Switzerland, and the UK. Average annual return on invested capital (ROIC) = NOPLAT/invested capital (NOPLAT = net operating profit less adjusted taxes). Average annual revenue growth = change in revenues. Average annual investment = capital expenditures / invested capital. Average annual R&D = R&D spending/revenue, top 2,500 R&D spenders.[37]

Source: McKinsey (2022). Weighted average, 2014–19, % (companies with > USD 1 billion in revenue). EU27+ = EU27 plus Norway, Switzerland, and the UK. Average annual return on invested capital (ROIC) = NOPLAT/invested capital (NOPLAT = net operating profit less adjusted taxes). Average annual revenue growth = change in revenues. Average annual investment = capital expenditures / invested capital. Average annual R&D = R&D spending/revenue, top 2,500 R&D spenders.[37]

[1] See, e.g., Bruegel (2010). A Single Market crisis. 11 July 2011. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/single-market-crisis.

[2] See Monti et al. (2010). A new strategy for the Single Market: At the service of Europe’s Economy Strategy. 9 May 2010. Available at https://ceplis.org/analysis-of-professor-mario-montis-report-a-new-strategy-for-the-single-market-at-the-service-of-europes-economy-strategy-some-suggestions-on-the-mutual/.

[3] See, e.g., ECIPE (2022). A Compass to Guide EU Policy in Support of Business Competitiveness. ECIPE Occasional Paper 06/2022. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/guide-eu-policy-in-support-of-business-competitiveness/.

[4] The Brussels Effect is a process of unilateral regulatory globalisation that results from the fact that the EU outsources its laws outside its borders, though not necessarily de jure, through market mechanisms. Due to the Brussels effect, regulated firms, especially corporations, also comply with EU law outside the EU for various reasons.

[5] European Parliament (2016). Reducing Costs and Barriers for Businesses in the Single Market. April 2016. Available at https://op.europa.eu/de/publication-detail/-/publication/db95af21-d95b-11e6-ad7c-01aa75ed71a1.

[6] European Parliament (2019). Europe’s two trillion euro dividend – Mapping the Cost on Non-Europe 2019-2024, April 2019. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/631745/EPRS_STU(2019)631745_EN.pdf.

[7] See European Commission (2020). Business Journey on the Single Market: Practical Obstacles and Barriers Accompanying. Compiled by the Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Available at https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1a9b0cf-6394-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

[8] See Copenhagen Economics (2020). Legal obstacles in Member States to Single Market rules. Study requested by the European Parliament’s IMCO Committee. Available at https://copenhageneconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/copenhagen-economics_legal-obstacles-in-member-states-to-single-market-rules.pdf.

[9] European Commission (2020). Business Journey on the Single Market: Practical Obstacles and Barriers Accompanying the document on Identifying and addressing barriers to the Single Market. 10 March 2020. Available at https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1a9b0cf-6394-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

[10] European Commission (2021). 2021 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard remains robust in ICT, health and green sectors, 2021 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard, 17 December 2021. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_6599.

[11] GSMA (2022). The Mobile Economy Europe 2022. Available at https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/051022-Mobile-Economy-Europe-2022.pdf.

[12] European Commission (1993). White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness and Unemployment: The Challenges and Ways Forward into the 21st Century. Available at https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0d563bc1-f17e-48ab-bb2a-9dd9a31d5004.

[13] Krugman, P. (1995). Competitiveness: A Dangerous Obsession, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 73:2, pages 28-44.

[14] For a longer version of this definition of competitiveness, see European Investment Bank, 2016, Restoring EU Competitiveness. 2016 Updated Version. Available at https://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/restoring_eu_competitiveness_en.pdf.

[15] See, e.g., Krcek, J. (2013). Assessing the EU’s ‘Lisbon Strategy:’ Failures & Successes. Inquiries Journal 2013, Vol. 5 No. 09.

[16] European Commission (2023). Recovery and Resilience Facility – The Recovery and Resilience Facility is the key instrument at the heart of NextGenerationEU to help the EU emerge stronger and more resilient from the current crisis. Available at https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/economic-recovery/recovery-and-resilience-facility_en.

[17] The country-specific recommendations´ database is the main tool for recording and monitoring progress with the implementation of CSRs. All CSRs adopted in the context of the European Semester since 2011 are registered in the database, as well as the Commission´s assessment on progress with their implementation over time. The database is available at https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/country-specific-recommendations-database/.

[18] SME Envoy network (2018). Barriers for SMEs on the Single Market, November 2018. Available at https://danishbusinessauthority.dk/sites/default/files/barriers_for_smes_on_the_single_market.pdf.

[19] A comprehensive overview of barriers for SMEs is given by the OECD (2023) in its “Glossary for Barriers to SME Access to International Markets”. Available at https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/glossaryforbarrierstosmeaccesstointernationalmarkets.htm.

[20] See European Commission (2021). European scale-up gap – Too few good companies or too few good investors? 20 December 2021. Available at https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/knowledge-publications-tools-and-data/publications/all-publications/european-scale-gap-too-few-good-companies-or-too-few-good-investors_en.

[21] See European Parliament (2021). Europe’s Digital Decade and Autonomy. October 2021. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/695465/IPOL_STU(2021)695465_EN.pdf.

[22] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness – Addressing its technology gap. September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/strategy%20and%20corporate%20finance/our%20insights/securing%20europes%20competitiveness%20addressing%20its%20technology%20gap/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap-september-2022.pdf.

[23] See PWC (2017). The Long View – How will the global economic order change by 2050? February 2017. Available at https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-the-world-in-2050-full-report-feb-2017.pdf.

[24] See Crunchbase (2022). Europe’s Unicorn Herd Multiplies As VC Investment More Than Doubled In 2021. Article of January 12, 2022. Available at https://news.crunchbase.com/venture/europe-vc-funding-unicorns-2021-monthly-recap/.

[25] Finbold (2022) Revealed: The U.S. has twice as many unicorns as China and India combined. 5 December 2022. Available at https://finbold.com/revealed-the-u-s-has-twice-as-many-unicorns-as-china-and-india-combined/.

[26] Atomico (2022). The State of European Tech 2022. November 2022. Available at https://prismic-io.s3.amazonaws.com/atomico-2022/cdfde802-3ed7-4248-b5db-b4b981741f29_Atomico-Report22_ready-to-upload.pdf.

[27] Atomico (2022). The State of European Tech 2022. November 2022. Available at https://prismic-io.s3.amazonaws.com/atomico-2022/cdfde802-3ed7-4248-b5db-b4b981741f29_Atomico-Report22_ready-to-upload.pdf.

[28] Atomico (2022). The State of European Tech 2022. November 2022. Available at https://prismic-io.s3.amazonaws.com/atomico-2022/cdfde802-3ed7-4248-b5db-b4b981741f29_Atomico-Report22_ready-to-upload.pdf.

[29] European Central Bank (2021). Key factors behind productivity trends in EU countries. ECB Strategic Review, No. 268. Available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op268~73e6860c62.en.pdf.

[30] PayPal Report (2018). Small Business Growth in Europe: Digitization is Enabling EU SMEs to Expand Globally. Available at https://s201.q4cdn.com/346340278/files/doc_downloads/reporting/Small_Business_Growth_in_Europe.pdf.

[31] European Investment Bank (2019). Who is prepared for the new digital age? – Evidence from the EIB Investment Survey. Available at https://www.eib.org/en/publications/who-is-prepared-for-the-new-digital-age.htm.

[32] See, e.g., report by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission (2019). Reassessing the Decline of EU Manufacturing: A Global Value Chain Analysis. Available at https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC118905.

[33] European Central Bank (2021). Key factors behind productivity trends in EU countries. ECB Strategic Review, No. 268. Available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op268~73e6860c62.en.pdf. Note: High technology sectors include manufactures of motor vehicles, telecommunications, computer, programming and consultancy services, financial services, legal activities and other professional services and administrative services. See Annex 5 for a complete list of high and low technology sectors. Low technology sectors include manufactures of food, utilities, transport and storage, construction and hotels and restaurants.

[34] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness – Addressing its technology gap. September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/strategy%20and%20corporate%20finance/our%20insights/securing%20europes%20competitiveness%20addressing%20its%20technology%20gap/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap-september-2022.pdf.

[35] The authors stress that high ROIC can reflect entrenched market positions and pricing power. However, “the growth and R&D gaps are clearly not sustainable for Europe.”

[36] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness – Addressing its technology gap. September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/strategy%20and%20corporate%20finance/our%20insights/securing%20europes%20competitiveness%20addressing%20its%20technology%20gap/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap-september-2022.pdf.

[37] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness – Addressing its technology gap. September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/strategy%20and%20corporate%20finance/our%20insights/securing%20europes%20competitiveness%20addressing%20its%20technology%20gap/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap-september-2022.pdf.

3. Fragmentation of EU Competition Policy

Competition policy, it is often said, is a cornerstone and key driver of the Single Market. Indeed, competition policy became a competence of the European Economic Community (EEC) as early as 1957. From the late 1950s onwards, the EEC considered strict competition enforcement as a vehicle for market integration. The overall goal of EU competition policy was to support the smooth functioning of the EEC market based on the principles of a market economy. Today, competition is still considered a crucial mainstay of Europe’s “Social Market Economy”, underpinned by the objective of the Union to “establish an internal market” and “a highly competitive social market economy” (Article 3(3) TFEU).

Contrary to sector-specific regulation and horizontal policies, such as Member States’ complex labour market laws and tax policies, the impact of competition policy on start-ups and SMEs is much more limited. Competition policy primarily impacts on larger companies and competitive companies that want to scale. In other words, competition rules typically affect companies that have economic efficiency advantages over smaller companies. At the same time, smaller companies can be indirectly affected by competition rules. Small businesses – access to products and their competitiveness – can be affected when large companies with significant network effects are forced to adapt or discontinue offers.

1.1. Shared Competences in EU Competition Policy

Competition policy in the Single Market is codified under Articles 101 to 109 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)[1]. It encompasses many fields, including, antitrust measures, merger control, abuse of dominance, and state aid. The European Commission has substantial enforcement power and a central coordinating role. Its decisions can only be contested in the Court of Justice of the European Union.[2]

At the same time, EU competition policy has not undergone a full process of harmonisation in the past. The European Commission has exclusive competence in establishing the competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market. Accordingly, the activities of Member States’ competition authorities and the European Commission must be conducted in accordance with the principles of an open market economy with free competition. However, Member States still have their own national regulators, which maintain different enforcement powers through domestic competition laws modelled after Articles 101 and 102 of the TFEU and enforced by the 27 National Competition Authorities.[3]

With the benefit of hindsight, few EU policies have been as successful as EU competition policy. However, what was once an unshakable reality of the EU acquis has recently been called into question. National governments as well as the European Commission have been willing to give up tried-and-tested principles of competition in favour of European companies struggling to keep up with international competition.

A “Franco-German Manifesto for a European industrial policy fit for the 21st Century“ recently called for a new division of power between the European Council and the European Commission on competition policy, and a more interventionist and active role from Member States on their industrial policies.[4] Moreover, recently imposed legislation governing the conduct of large technology companies, the Digital Markets Act (DMA), allocates new competences to both the European Commission and Member State authorities.[5] As a result, EU businesses face various risks from legal fragmentation and discretionary enforcement, notably new and unclear rules describing anti-competitive behaviour and individual decisions related to abusive practices by Member State authorities.

1.2. EU Competition versus Industrial Policy

Following the European Commission’s dismissal of the merger of Alstom and Siemens in 2019, the two large incumbents of Europe ́s railway manufacturing sector, the governments of France and Germany presented a manifesto with a set of far-reaching proposals designed to reshape EU industrial and competition policy.[6] Highlighting the need for “fairer” competition in the EU, the President of France, Emmanuel Macron, called for a reform of EU competition policy to protect Europe from foreign competition.[7]

The manifesto suggests, inter alia, to “consider whether a right of appeal of the Council which could ultimately override Commission decisions [on competition policy] could be appropriate in well-defined cases, subject to strict conditions”. It also called for a relaxation on EU State Aid rules “to finance major research and innovation projects including the first industrial deployment (IPCEI) in Europe”, aiming “to develop innovative industrial capacity in Europe”.

The proposal to veto European Commission decisions on competition policy, is defended by the claim that Europe ́s competitiveness in manufacturing is in decline. A weakening of the EU’s competition policy, the manifesto claims, will strengthen Europe ́s competitiveness. Others, such as Guy Verhofstadt, an influential Member of the European Parliament and the leader of the European liberals, supported similar claims based on political concerns that Europeans cannot compete with Chinese or US American firms.[8] As outlined above, many indicators for EU technological and industrial development suggest that the political diagnosis is right. However, the solutions offered by the EU’s largest Member States are in several aspects misleading, risking that political capital is invested in the wrong and, due to cumbersome political proceedings, often irreversible reforms. The crucial factor shielding incumbents from competition in Member States’ markets is the restrictiveness of regulation or national differences in regulation, increasing the cost of compliance and market access respectively.

To increase EU competitiveness, European firms need more, not less competition. The problem is that market competition within the EU has been on decline in many sectors of the economy. Individual companies or small groups of firms tend to dominate markets for a very long time, reflected by high market concentration ratios in many sectors and stagnating markups. In addition to growing market concentration, markups, i.e., difference between the cost of the product and the price paid by consumers, have been rising or stagnating in a number of sectors.[9]

Firm-level data by the Competitiveness Research Network (CompNet) of the ECB show that market concentration increased in most EU Member States (at least) since the beginning of Europe sovereign debt and economic crises in 2008. While market concentration is high in many manufacturing sectors (e.g., automotives and chemicals), regulated services are generally the most concentrated markets in many EU countries. Large incumbent businesses often hold the majority of the market share in services industries. In Germany, for example, the ten largest companies capture more than 90% of the market in air transport, postal, water transport, and broadcasting services. Similarly, the ten largest companies control 75% of information services, including data processing and data hosting services, in Germany.[10]

Market structure can only partially explain high levels of market concentration. Industries such as postal, telecommunication, water and air transport are network industries with significant sunk costs. Network industries are prone to having only few players. However, within the same sectors, market concentration varies widely across EU Member States, implying that more competition in these industries is possible and that regulation poses a barrier to entry into Member States’ markets.

EU industry data indicates that over the past decade Member States experienced a reallocation of economic activity towards large and concentrated industries. This trend contributed to productivity gains in some industries. However, markups have largely remained constant over time, indicating low competitive pressure despite increases in efficiency and productivity in concentrated markets.[11] In other words, in addition to growing market concentration, markups have not come down.

Market concentration is not necessarily a problem in itself. Competition can be thriving even with only a few players in a certain market: if consumers are willing to shop around and barriers to entry are low, competitive pressure will force even the largest businesses to adapt. However, data indicates that innovation has not been the prime driver of market concentration in the EU. If innovation were the driving force behind market concentration in Europe, labour productivity should have grown considerably, as incumbents, relying on new technologies and business models to their advantage would become more efficient. However, in many sectors of the EU economy, labour productivity has stagnated or declined since the early 2000s.[12]

The data also shows that regulatory barriers are positively related to market power, market concentration and profitability of the incumbent. In other words, the higher the level of regulation the higher the markups and market concentration. Therefore, any change in competition policy should account for the level of regulatory restrictiveness in each sector.

The high level of regulatory protection and legal fragmentation in EU Member States has a bearing in the decline in market competition in the EU and must be taken into account in any future discussion of EU industrial and competition policy. Policymakers should not be concerned about the level of markups, as firms could charge higher prices because they produce better products; what they should be concerned about is the persistence of markups in sectors where concentration increased.

The Franco-German push for changes in EU competition policy should be considered an opportunity to politically address structural weaknesses in EU regulation and legal integration. Policymakers in Europe should question traditional approaches to policymaking in the Single Market, notably the inability to reduce regulatory protection and national differences in horizontal and sector-specific regulations.

Any change in EU competition policy should account for the regulatory context in which firms operate in the EU, both at EU and Member State level. As highlighted by IMF (2018), competition policy should aim at sectors “where barriers to entry are driving the increase in market power, and where that power is being used to, restrict supply, or engage in predatory pricing“. At the same time, „rising network and information externalities and increasing returns to scale may justify the existence of an oligopolistic structure in certain industries.“[13]

By imposing national rules for business conduct, regulation can be used as a tool to protect domestic incumbents from competition, which has profound implications: if lobbying for protective regulation is more profitable than competing on the basis of quality and innovation, the activities of a company will shift away from innovation and towards politics and political rent-seeking respectively.[14] If this does not change in Europe, innovation, productivity growth and prosperity will increasingly be generated outside of Europe. The industrial policy goals set by the Commission and the Member States would not come close to being achieved in the future.

1.3. Fragmentation and Legal Uncertainties Created by the DMA

A key guiding principle of the EU competition policy is to ensure consistent rules in support of a smooth functioning of the Single Market. However, success stories in technology-enabled (digital) services have brought with them a threat of increasing fragmentation in EU competition law.

In the EU, much of the contemporary debate in economic policymaking is about competition in digital markets. Concerns include the risk of “tipping”, “winner takes most” markets, and underlying economic features such as role of data, network effects, economies of scope and scale. In this regard, policymakers highlighted that EU legislation on competition has not been sufficient to ensure “open markets” or “fair competition”. Until recently, the EU and Member States have been regulating digital services markets by bringing antitrust cases against technology companies. However, these cases, it was said, have been long and time-consuming and did not lead to the outcomes deemed necessary by policymakers to avoid the abuse of market power in digital markets.[15]

Growing political interest in regulating digital service providers caused some Member States to propose or enact national competition rules, which effectively increased fragmentation of and legal uncertainties from competition policy in the EU. For instance, a memorandum from the Nordic competition authorities on the potential changes to EU competition law for digital platforms emphasises the importance of supporting national competition authorities in dealing with the challenges arising from digital platforms. The memorandum highlighted the value added by national competition authorities to the EU level competition law.[16] Moreover, in a joint paper by the heads of the national competition authorities in the EU, the national regulators wish to have a significant role in the enforcement of the changing competition policies for the digital services to ensure “quick and effective implementation”.[17] In a similar vein, the “Friends of an Effective Digital Markets Act” coalition, composed of Germany, France, and the Netherlands, has issued a position paper titled “Strengthening the Digital Markets Act and Its Enforcement” within proposed that Member States should be able to set and enforce national rules around competition law because the “importance of the digital markets for our economies is too high to rely on one single pillar of enforcement only.” The coalition also stated that “a larger role should be played by national authorities in supporting the European Commission.[18]

Some Member States have been gearing up to take on large technology companies with their own national legislation, such as Article 19a, which was added to Germany’s national competition law in 2021. And many initiated legal proceedings against leading technology companies based on traditional competition rules and claims of violation of national competition policy.[19]

Recognising the risk of fragmentation in EU’s Digital Single Market, the EU adopted the Digital Markets Act (DMA) in September 2022.[20] The DMA’s objective at the time of its conception was to promote competition, contestability, fairness, and regulatory harmonization in the EU’s digital sector. The regulation is targeted at so-called “gatekeepers” in digital markets operating in Europe – large technology-driven companies which are accused of maintaining too much market power through which they may act in ways that reduce competition and fairness. The DMA, in its own words, according to its Article 1(1), intends to “contribute to the proper functioning of the internal market by laying down harmonised rules” and prevent fragmentation of the internal market. And one of the prime objectives was to avoid legal fragmentation in EU competition policy.

However, contrary to its primary objective, the DMA does not seem to prevent regulatory fragmentation in the EU, neither in competition law nor in sectors in which digital services are increasingly adopted. It seems to allow national Member States to implement their own competition laws for dealing with competition in digital markets, and to apply national enforcement measures against companies designated as gatekeepers. And national regulators that already apply DMA-like rules to digital gatekeepers do not appear to acknowledge the harmonising effect of the recently adopted DMA.[21] Specifically,

- As a general principle, the DMA does not remove national regulatory barriers on how companies, small and large, can provide digital services in across EU Member States.

- The DMA increases the risk of disparate enforcement by Member States’ own competition authorities. Article 1(6) details that the Member States can impose their own national competition rules on gatekeepers and set new ones as long as they are in line with the national rules. Given the national authorities’ appetite for stronger national enforcement powers, as outlined above, the overlap between the provisions under the recently implemented DMA and those established by national competition authorities will likely increase fragmentation in EU competition policy and create more legal uncertainty for digital services providers subject to these regulations.

- The DMA also allows for the decentralised enforcement of its rules which further undermines the functioning of the Single Market. National competition authorities are granted significant power in enforcing the DMA. According to Article 38(7) of the DMA, national competent authorities can launch an investigation into possible DMA non-compliance by gatekeepers. This enforcement is only subject to the relevant authority informing the Commission of such investigations and imposed obligations.

- Under Article 41 of the DMA, three or more Member States will be able to request the Commission to open market investigations against a gatekeeper and potentially add new obligations to the DMA.

- Finally, under Article 40 of the DMA, Member States’ National Competition Authorities will participate in the High-Level Group established under the DMA via the involvement of the European Competition Network. Accordingly, the DMA provides considerable freedoms for the Member States to press for more frequent and regular consultations in the Commission’s application of the regulation.

All this raises questions about the legal basis of the Digital Markets Act: the DMA has Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union as a legal basis, which enables the EU to adopt “measures for the approximation of the provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States which have as their object the establishment and functioning of the internal market.” That is, the EU can legislate under Article 114 TFEU only for harmonisation purposes. The ability of Member States to adopt DMA-like obligations under the guise of national competition rules and the significant investigative powers entrusted to national authorities by the DMA beg the question of whether this Regulation achieves the objectives set out in Art. 114 TFEU, namely the “establishment and functioning of the internal market”.[22]

Moreover, data shows that the European Commission’s assumptions regarding market dominance and market abuse by large digital companies in the EU do not correspond to consumers’ experiences. The question arises as to whether the EU has indeed chosen the path of industrial policymaking with the DMA to achieve industrial and trade policy goals rather than safeguarding competition in the Single Market.[23]

1.3.1. Economic Regulation of Competition in Digital Markets Fails To Prevent Fragmentation in the Single Market

The power granted to Member States to enforce their own national competition rules for digital market not only risks creating regulatory fragmentation and legal uncertainty for digital companies. It can also lead to over-regulation and over-enforcement respectively. Germany is a case in point. Discretionary enforcement powers granted by the DMA together with new national competences have led to Germany’s competition authority questioning the overriding principles of European competition policy. With its recent objection raised against Google’s business conduct in Germany, Germany’s competition authority, the Bundeskartellamt, could open a Pandora’s box, amplifying legal uncertainties for digital services providers across the EU with varying impacts on technology companies and, as a result, the users and adopters of digital services.[24]

Digital services provided by large technology companies are governed by Germany’s “Digitalization Act”. Inspired by the DMA, the act entered into force on January 19, 2021, amending the “Act Against Restraints of Competition (ARC)” with the introduction of Section 19(a). Similar to the DMA, Section 19(a) provisions allow Germany’s Bundeskartellamt to “intervene at an early stage in cases where competition is threatened by certain large digital companies”.[25]

The amendments to Germany’s ARC essentially adopt similar obligations and prohibitions as those contained in the DMA. For instance, it determines an undertaking to be of “paramount significance” in competition markets through similar criteria that the DMA has to classify a company as a “gatekeeper”. For “undertakings of paramount significance”, Section 19a prohibits similar kinds of conduct as under the DMA, such as self-preferencing, conditional usage based on user data collection, and self-advertising. The amendments also sought to shorten the legal process where appeals against decisions will be directly brought before the Federal Court of Justice.

Given Germany’s leading role in the EU, it is possible that other Member States will be inspired to follow suit and adopt their own “national DMAs”.[26] As argued by many observers during the DMA’s legislative procedure, the introduction of national laws on competition in the digital sector under the purview of the DMA (since it allows for enforcement of national laws), creates the risk of diverging interpretations of the DMA in national law. It also risks overregulation of technology companies that operate in the EU because they may be subject to the DMA as well as multiple national regulations that may diverge from the DMA in certain aspects.

The challenges of the DMA and Section 19a of ARC for the Single Market are reflected by the recent statement of objections raised by the Bundeskartellamt against Google’s data processing terms. The “[s]tatement of objections issued against Google’s data processing terms” was issued on 23 December 2022. With its objections against the company’s data processing terms, the Bundeskartellamt seeks to regulate the cross-use and combination of personal data. It is argued that, based on its current terms, Google can combine a variety of data from various services and use them to create very detailed user profiles which the company can exploit for advertising and other purposes. In its preliminary conclusion, the Bundeskartellamt criticises that “users are not given sufficient choice as to whether and to what extent they agree to this far-reaching processing of their data across services,” which are used when providing a variety of services, “such as Google Search, YouTube, Google Play, Google Maps and Google Assistant, but also by way of numerous third-party websites and apps.” It is concluded that “[g]eneral and indiscriminate data retention and processing across services without a specific cause as a preventive measure, including for security purposes, is not permissible either without giving users any choice. Therefore, the Bundeskartellamt is currently planning to oblige the company to change the choices offered.“

In December 2022, the Bundeskartellamt determined that Google is a company of paramount significance for competition across markets pursuant to Section 19a ARC, on the basis of which the Bundeskartellamt can prohibit the company from engaging in alleged anti-competitive practices. However, the cross-use of personal data is conduct already regulated by the DMA under its Article 5(2) provision. Indeed, as explicitly outlined by the Bundeskartellamt, the current objections on Google “based on the national provision under Section 19a GWB [ARC] partially exceeds the future requirements of the DMA.”[27] The proceedings may result in the Bundeskartellamt discontinuing the case, the company offering commitments or the competition authority prohibiting certain practices. A final decision is expected to be issued in the course of 2023.[28] Competition authorities in other member states will be following the proceedings at the Bundeskartellamt and may create their own rules or initiate their own proceedings.

1.3.2. Impacts on the Adoption of Digital Innovation in the EU

The DMA was meant to improve the contestability of platform services markets and markets that rely substantially on digital services. However, the DMA is untested regulation. It takes a novel approach to regulation, and novelty in concepts and regulatory requirements can lead to outcomes that later have to be corrected. Due to their pre- and proscriptive nature, the DMA’s rules will ultimately impact companies’ incentives to test new technologies and business models and determine whether they can reach scale in Europe’s legally fragmented Single Market.

Being a horizontal regulation, the effects of the DMA can be extraordinarily impactful. Its rules impact the frontier of technological developments and how adopting businesses can use them in downstream markets. For large technology companies, vaguely formulated rules in the DMA and, potentially, discretionary enforcement by the European Commission and Member States pose several challenges. Services portfolios may have to be changed to qualify for EU markets, impacting how companies and citizens can access and use digital services in the EU.

These challenges go beyond designated gatekeeper companies; they also arise for EU companies approaching the numerical threshold levels of gatekeeper designation.[29] Generally, aspiring European digital companies will only thrive and compete if they can reach scale economies and reap the benefits of the network effects. If incentives to reach scale economies are taken away, technology platforms are bound to fail and providers exit the market.[30] Consequently, this could mean that large European technology companies will move to other markets to scale-up.

The major direct economic implication of the DMA is that large digital services providers will be prohibited from offering users some of their established services. For instance, some services connected to the core platform service are of value simply because they are connected to the core platform service, and that the provider of the core platform service can offer complementary services. User data from search and social media activities and, generally, usage data are utilised to improve the quality of search results, location and navigation services, enterprise resource management, language translation, and cybersecurity. In addition, by subsidising (investing in) new and typically unprofitable business models, new product offers are brought to market, with greater benefits for customers.

Consequently, the question arises whether modified or terminated services will be offered by other providers and in a way that is equal or better than the current alternatives. If it is not the case, the result is likely to be a market depression effect and that corporate and private users in Europe will be denied access to services that are offered outside the EU. Impact assessments of the DMA conclude that the act’s rules and obligations will reduce innovation and the choice available to Europeans.[31]

As concerns the risk for further fragmentation created by the DMA, the statement of objections recently issued by Germany’s competition authority, the Bundeskartellamt, shows that this is not a theoretical problem anymore. Germany’s section 19a imposes obligations as restrictive as the DMA‘s Article 5.2. If the legal proceedings in Germany are left unchallenged by the Commission, data processing terms and associated product offerings in Germany would be different to those in other EU Member States. Moreover, Germany’s competition authority could in the future leverage this precedent and consider imposing even more requirements, e.g., blocking or limiting vertical integration. The consequences would surely go beyond the affected companies, which would be confronted with even higher legal compliance cost and additional legal risks. Local adopters of advanced digital services, particularly small businesses, that use advanced technology services to compete in their markets would be confronted with less choice and quality.

Hinging on the discretion of national competition authorities, different terms and conditions for data processing will impact on how technology adopters in the EU compete in Member State and international markets. With the development of new and potentially more national competition rules, fragmentation in competition policy will not just be limited to the EU’s 27 Member States. It risks resulting in increasing global regulatory fragmentation in the digital economy.[32] Given that digital markets and services know no borders, differences in competition regulation between countries can lead to differences in the way companies innovate, use data, and subsequently how they grow to become internationally competitive players in the markets they operate in.

There are large differences in the number of technology firms in the US compared to the EU, and competition policy has some role to play in contributing to these differences. One key limitation in this regard concerns how static and dynamic competition are accounted for in EU competition policy. Static competition describes situations in which firms compete for existing rents and firms supply close to perfect substitute products. Approached from the angle of static effects, more competition results in short-term price decreases, cost-cutting, including wage reductions. Dynamic competition, on the other hand, describes a situation in which firms compete for future rents and use innovation to introduce new products, processes, and services. Accounting for dynamic effects, competition results in product differentiation, recombination, integration, diversification, or “platformisation”. It is a type of competition animated not by firms that compete head-on with similar products but by heterogeneous competitors, complementors, suppliers, and customers, using innovation to bring forth new products and processes.[33] These strong dynamic capabilities are a major contributor to the success of large digital firms. Under dynamic models, innovation drives competition just as much as competition drives innovation. EU case-law has slowly moved towards a recognition of the importance of dynamic competition, but EU digital and competition policy still lack this perspective.