The Impacts of EU Strategy Autonomy Policies – A Primer for Member States

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Research Areas: EU Single Market EU Trade Agreements European Union Trade Defence

Summary

EU governments should be much more sceptical and critical of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda and the new polices intended to achieve the EU’s “long-term” industrial and technological ambitions. The long-term costs for Member States’ economies and the process of economic convergence are largely ignored by the agenda. Negative impacts of strategic autonomy on trade openness and the international rules-based trading system are also greatly understated.

Many EU strategic autonomy ambitions are inherently guided by a “European Union First” impulse. Policymakers follow the assumption that EU values are superior to those in other parts of the world and EU regulation should be different from third countries. Major strategic autonomy aspirations represent a relapse of the EU to the old policy of EU member states designing and enforcing their own laws without considering the economic and political costs of regulatory fragmentation and economic disintegration from others.

Recent strategic autonomy policies are estimated to create income losses in the EU of between 0.08% and 0.15% of EU27 GDP. These losses correspond to short-term economic harm resulting from changes in the use of productive resources in the EU. Long-run impacts, which reflect losses to productivity and innovation, could be up to 3 to 5 times higher with national income per capita falling by up to 0.5% to 0.75%. The costs are not evenly distributed across the EU27. Larger countries like France and Germany are less impacted than smaller ones, notably Ireland and the Baltic states. The impacts on Ireland, for example, are close to 4 times bigger than they are for France, the impacts on Estonia close to twice those on Germany.

Strategic autonomy ambitions have failed to account for negative impacts on developing countries. To the extent that the EU’s policy stance further fragilizes rules-based multilateralism, there are longer-term impacts stemming from a less certain legal environment and higher barriers for cross-border trade and investment. EU strategic autonomy policies have the effect of empowering vested interests in developing countries to engage in lobbying for their own protectionist policies. Accordingly, EU strategic autonomy policies risk encouraging the diffusion of protectionist policies globally, particularly in countries with weak institutional capacity.

EU Member States should examine their options and ask themselves whether there are better long-term strategies to pursue than those currently proposed at the EU level, strategies guided by the spirit of an open society – a society embracing the principles of free trade, non-discrimination, and economic freedom. Europe’s policymakers should aim for closer market integration and regulatory cooperation with trustworthy international partners such as the G7 and the larger group of the OECD countries. It is in the EU’s self-interest to advocate for a rules-based international order with open markets. It is neither in the EU’s economic nor its political interest to disintegrate from partner countries.

1. Introduction

The EU is pushing a controversial policy paradigm: strategic autonomy. It is commonly referred to in speeches by high-level officials. New EU laws are infused with the concept and its derivations, such as industrial autonomy or technological sovereignty. Their precise meanings, intentions and actual impacts remain obscure. Policymakers in Brussels seem to be most concerned about which companies operate in the EU and how they exchange products, services, and data with the rest of the world. Highlighting the EU’s political ambitions for autonomy, the European Commission takes many novel approaches to regulation, including new bans, standards, incentives, and deterrents for production and consumption in the Member States.

In September 2020, European Council President Charles Michel delivered a long speech on Europe’s “strategic autonomy, sovereignty, and power”.[1] He concluded that “whichever word you use”, it is the substance that eventually matters: “Less dependence, more influence” should be the “aim of our generation”. Josep Borrell, the EU’s High Representative, clarified that strategic autonomy must go beyond defence and security. The concept should be extended to the realm of business and technology “to ensure that Europeans can increasingly take charge of themselves.”[2] The past two years have witnessed many more speeches and calls for EU action in the name of European strategic autonomy. Policy initiatives have ranged from defence and cybersecurity to trade and technology policy.

In its 2021 Trade Policy Review, the European Commission defines strategic autonomy as “the EU’s ability to make its own choices and shape the world around it through leadership and engagement, reflecting its strategic interests and values.”[3] It largely builds on earlier notions raised by EU and national policymakers ever since Jean-Claude Juncker, the former President of the European Commission, proclaimed in 2018 that now is the “The Hour of European Sovereignty” – the right time for Brussels to globally roll-out EU rules for the deployment of big data, artificial intelligence, and automation.[4] Political leaders in France and Germany thereupon called for new industrial policies such as data localisation, a European cloud, and even an Airbus for artificial intelligence. Smaller EU countries, such as the Nordics[5] and CEE countries[6], were generally more reluctant to echo demands for strategic autonomy ambitions in economic and technology policymaking, referring to the merits of interdependences, the international division of labour, and policy coordination with non-EU governments.

In its latest Strategic Foresight Report from June 2022, the European Commission reiterated the desire for EU interventions to “strengthen resilience and strategic autonomy”.[7] Contemplated measures include new rules for supply chains, the sharing of data, and policies conducive to sustainable businesses in the EU. The Commission is building on many initiatives that have already been passed or proposed.

This paper outlines and discusses key economic and (geo-)political impacts of strategic autonomy policies that have largely been ignored by policymakers in Brussels and the Member States. The paper is organised as follows:

- Chapter 2 provides a four-tier taxonomy of EU strategic autonomy policies,

- Chapter 3 discusses the role of “European values” and the “EU first” bias in strategic autonomy policymaking,

- Chapter 4 outlines potential economic costs of major EU strategic autonomy policies,

- Chapter 5 discusses asymmetries in the impacts on small and large EU Member States and implications for the EU’s regulatory impact assessments,

- Chapter 6 elaborates on the impacts on the international rules-based trading system and the freedom to trade internationally,

- Chapter 7 discusses the role of the EU’s fragmented Single Market for strategic autonomy ambitions, and

- Chapter 8 concludes with a list of policy recommendations.

[1] European Council (2020). Strategic autonomy for Europe – the aim of our generation’ – speech by President Charles Michel to the Bruegel think tank, speech by Charles Michel, 28 September 2020. Available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/de/press/press-releases/2020/09/28/l-autonomie-strategique-europeenne-est-l-objectif-de-notre-generation-discours-du-president-charles-michel-au-groupe-de-reflexion-bruegel/.

[2] EU External Action Services (2020). Why European strategic autonomy matters, speech by Josep Borrell, 3 December 2020. Available at https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/why-european-strategic-autonomy-matters_en.

[3] European Commission (2021). Trade Policy Review – An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy, 8 February 2021. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0066&rid=7.

[4] European Commission (2018). President Jean Claude Juncker’s State of the Union Address 2018, 12 September 2018. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_18_5808.

[5] Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies (2021). Strategic Autonomy – Views from the North, Perspectives on the EU in the World of the 21st Century. Available at https://www.sieps.se/globalassets/publikationer/2021/2021_1op.pdf.

[6] GLOBSEC (2021). The EU Strategic Autonomy: Central and Eastern European Perspectives, Available at https://www.globsec.org/what-we-do/publications/eu-strategic-autonomy-central-and-eastern-european-perspectives.

[7] European Commission (2022). 2022 Strategic Foresight Report: twinning the green and digital transitions in the new geopolitical context, 29 June 2022. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_4004.

2. Taxonomy of strategic autonomy policies

It is difficult to come up with a clear-cut taxonomy of EU policies that are guided by the strategic autonomy paradigm. After all, the term remains a political marketing instrument – a novel way of political storytelling – to renew (lost) trust in EU institutions and centralised policymaking. Moreover, it emerged on the heels of Donald Trump‘s push for “America First“ policies and ambitions of China’s Communist Party to confront foreigners with new market access restrictions.

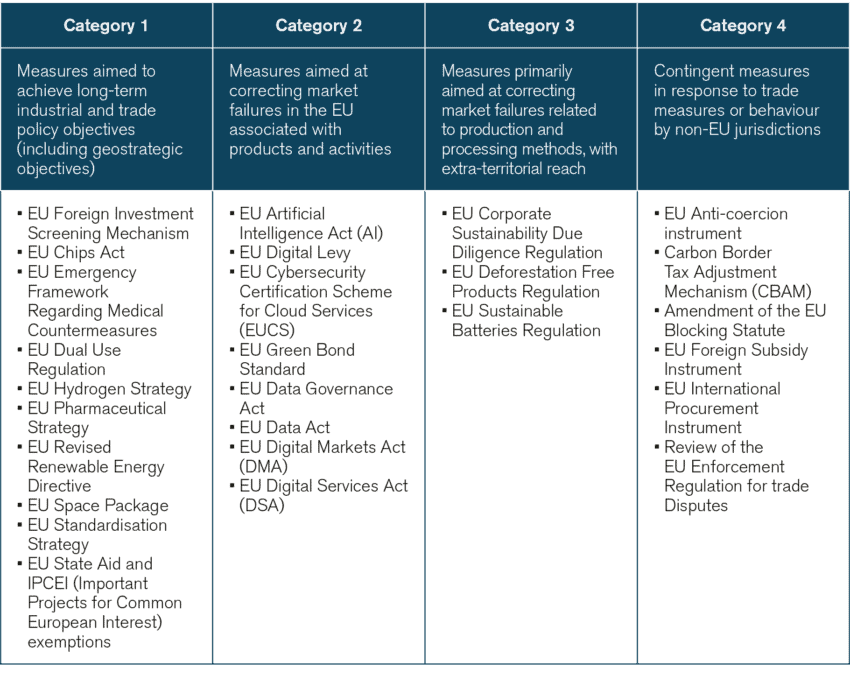

However, we can broadly distinguish recently implemented or proposed EU policies based on central political concerns underlying the strategic autonomy paradigm.[1] These are:

- EU interventions seeking to fulfil industrial and trade policy objectives through direct interventions in favour of EU businesses, such as reducing perceived dependencies on non-EU suppliers, underinvestment in R&D, and industrial modernisation (green growth and digitalisation). Interventions are generally geared to conferring advantages to EU businesses over those from outside the EU. Policies include the Foreign Investment Screening Mechanism, State Aid flexibilities, Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEIs), and the Chips Act.

- EU interventions aimed at correcting perceived market failures (primarily) in the EU, including perceived market power and collective action problems (environmental impacts), but also ethical concerns related to fundamental rights. Policies include the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Data Act, the Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the Digital Services Act (DSA).

- EU interventions intended to correct perceived market failures related to production and processing methods with extra-territorial reach, including value chain resilience and environmental standards. Policies include the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence regulation and restrictions to the free cross-border flow of data as provided in the Data Act and the GDPR.

- Contingent interventions in response to trade measures or behaviour by non-EU governments, including responses to perceived trade restrictive or distortive policies, or actions sought to remedy what the EU perceives to be a shortcoming in the multilateral toolkit. Policies include the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and the Foreign Subsidy Instrument, and the revised Trade Enforcement Regulation.

For each category, relevant EU policy initiatives are outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1: (Broad) taxonomy of strategic autonomy policies and proposed initiatives by major category Source: Frontier Economics and ECIPE. It should be noted that these categories cannot be clearly delineated from each other. Some measures in category 1 include measures intended to address perceived market failures related to R&D. Some measures in category 2 also seek to enhance the competitive position of EU industries, while some category 2 measures can have extra-territorial reach. Also, some measures in category 4 can help address prevailing market failures such as asymmetric information about the extent of state aid and negative externalities caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Source: Frontier Economics and ECIPE. It should be noted that these categories cannot be clearly delineated from each other. Some measures in category 1 include measures intended to address perceived market failures related to R&D. Some measures in category 2 also seek to enhance the competitive position of EU industries, while some category 2 measures can have extra-territorial reach. Also, some measures in category 4 can help address prevailing market failures such as asymmetric information about the extent of state aid and negative externalities caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

[1] This broad classification is inspired by discussions with Frontier Economics. ECIPE commissioned Frontier Economics, a consultancy, with a study to estimate the costs of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda. The full study is available at www.ecipe.org.

3. “EU First”: European values underlying ambitions for strategic autonomy

Many EU strategic autonomy ambitions are inherently guided by a “European Union First” impulse, manifested in the assumption that EU law-making is superior to or at least different from law-making in other parts in the world with respect to values and corresponding market regulations.

The EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm and many policies defended by it are rooted in a broader set of geopolitical clashes questioning the role and reach of government in society. In Brussels, much of today’s debate is about protecting Europeans from an increasingly hostile and challenging world. It unfolded momentum after the fiscal and economic crises of 2009 to 2012. It is a reaction to the rise of China’s state-interventionist influence[1] in the world, including Chinese investments in Europe[2], the challenges in multilateral economic cooperation[3], the perception of US-Chinese hegemony in the digital world[4], US protectionism based on national security considerations[5], the EU’s trust crisis and the rise of populism[6], the impacts of COVID-19, and responses to Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine[7] (with aggressions starting to evolve in 2014).

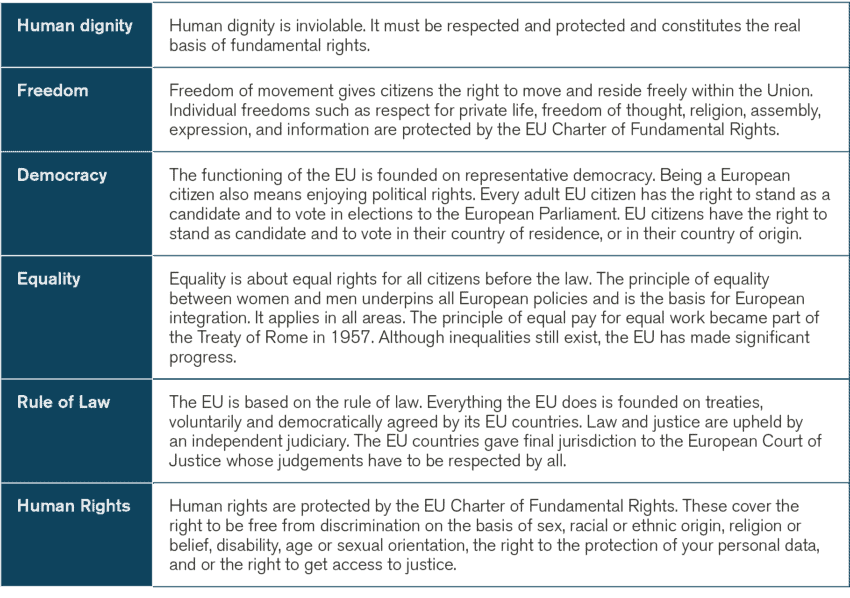

As argued by Burwell and Propp, the “return of geopolitics prompted a review of Europe’s strategic position and, at least within EU institutions, gave rise to a belief that Europe should seek greater ‘strategic autonomy‘, strengthening its capacity to act externally on its own […]“.[8] This is expressed by EU institutions when they underline the need to defend “our European values” (see Table 2), as highlighted by the political guidelines of the von der Leyen Commission[9], aiming to protect the “European Way of Life”[10], and in their delegated working programs[11].

Table 2: Core values of the European Union Source: European Commission.

Source: European Commission.

Values and Superiority of EU Policymaking

In the case of strategic autonomy, European values aim to guide a large package of legislation on state aid and industrial policies, new rules for competition and new policies for data, artificial intelligence, and investment – often accompanied by the ambition to strengthen Europe’s global influence and the goal to improve the competitiveness of Europe’s industry.

Anchoring EU politics in an understanding of values is undoubtedly important, especially when these values are based on the ideals of the European enlightenment, underpinning Universal Human Rights[12]. However, the values proclaimed by the EU are neither novel nor exclusive to Europe, and they often come at the expense of policy detail and poor regulatory design. If there is one charge that can be made against this type of value-based policymaking, it is that it comes across as hollow grandstanding, hiding the contradictions, inconsistencies, and often the ineffectiveness of EU policymaking.

Recurring references to European values lead to the impression that people outside Europe have different values or values that could pose a threat to the European way of life. At the heart of this view is the perception that EU trade and technology regulation presents a fundamental choice between European values on the one hand, and the freedom to do business with non-Europeans on the other. It is notable, for example, how fast some EU policymakers call for far-reaching measures to create notional data sovereignty[13], reinforcing a misguided view that in order to create a larger digital autonomy, Europe must close itself off from the rest of the world. Radical views like this ignore that Europe’s “digital sovereignty” is actually based on the capacity of citizens and firms to have access to key technologies and services and be independently capable of understanding, using and altering these services in line with the fundamental rights.

Importantly, Europe is not so different from other jurisdictions in its desire to safeguard citizens and make sure that businesses thrive. OECD countries, for example, have ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Most OECD countries already have or are considering having laws to regulate key areas of interest for the EU. OECD countries already established more than 300 committees, expert and working groups which cover almost all areas of policy making including trade and technology regulation. As an open and export-driven economy, Brussels should not try to set the global standards for trade and technology alone. Europe’s policymakers should aim for closer market integration and regulatory cooperation with trustworthy international partners such as the G7 or the larger group of OECD countries. It is in the EU’s self-interest to advocate for a rules-based international order with open markets. It is neither in the EU’s economic nor its political interest to disintegrate from the partner countries. As outlined below, new trade restrictions, increased policy fragmentation and economic disintegration come at high cost for Europeans.

[1] Zhang, A. and Yin, W. (2019). Chinese State-Owned Enterprises in Africa: Always a Black-and-White Role? Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333895172_Chinese_State-Owned_Enterprises_in_Africa_Always_a_Black-and-White_Role.

[2] MERICS (2021). Chinese FDI in Europe: 2020 Update, 16 June 2021. Available at https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2020-update.

[3] MERICS (2021). Chinese FDI in Europe: 2020 Update, 16 June 2021. Available at https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2020-update.

[4] BCG (2017). The New Digital World: Hegemony or Harmony?, 14 November 2017. Available at https://www.bcg.com/de-de/publications/2017/strategy-globalisation-new-digital-world-hegemony-harmony.

[5] Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2021). How Trump’s Tariffs Really Affected the U.S. Job Market, by Michael Pettis, 28 January 2021. Available at https://carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancialmarkets/83746.

[6] Brookings Institution (2017). The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/4_alganetal.pdf.

[7] European Parliament (2022). EU strategic autonomy in the context of Russia’s war on Ukraine [What Think Tanks are thinking], 10 March 2022. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2022)729300.

[8] Burwell, F. G. and Propp, K. (2020). The European Union and the Search for Digital Sovereignty – Building “Fortress Europe” or Preparing for a New World?, Atlantic Council, June 2020. Available at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-European-Union-and-the-Search-for-Digital-Sovereignty-Building-Fortress-Europe-or-Preparing-for-a-New-World.pdf.

[9] European Commission (2019). A Union that strives for more, My agenda for Europe, by candidate for President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en_0.pdf.

[10] European Commission (2022). The EU values. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/component-library/eu/about/eu-values/.

[11] European Commission (2022). Commission adopts its Work Programme for 2023: Tackling the most pressing challenges, while staying the course for the long-term, 18 October 2022. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_6224.

[12] United Nations (2022). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available at https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[13] Politico (2020). EU eyes tighter grip on data in ‘tech sovereignty’ push, 29 October 2020. Available at https://www.politico.eu/article/in-small-steps-europe-looks-to-tighten-grip-on-data/.

4. Measuring the costs of European strategic autonomy policies

A study by Frontier economics provides estimates of costs of a wide range of policy proposals and initiatives pursued under the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda.[1] It is highlighted that, if implemented, “these initiatives are likely to impose costs on EU imports and exports, which would reduce EU living standards”. Depending on the stringency of the measures involved and the degree of retaliation by EU trading partners that are confronted with EU trade measures, real income would fall by several billion euros annually, with the highest reduction in income and welfare being estimated for scenarios in which retaliation by partners kicks in.

Conservative estimates by Frontier Economics place the loss at between $12 billion and $22 billion in national income on an annual basis (between 0.08% and 0.15% of EU27 GDP). That is around the size of effects associated with a large EU Free trade Agreement (FTA). The authors highlight that these losses correspond to short-term economic harm resulting from changes in the allocation of productive resources (inputs to production such as labour, machinery, and other technologies).

Importantly, it is stressed that the long-run impacts, which reflect losses to productivity and innovation, could be up to 3 to 5 times higher (as discussed below). Using an alternative way of estimating the economic impacts of trade policy to account for the dynamic effects of trade on productivity growth and innovation, EU national income per capita could fall by up to 0.5% to 0.75%.

Frontier’s estimates are not evenly distributed across the EU27. In particular, larger countries like France and Germany are less impacted than smaller ones, notably Ireland and the Baltic states. The impacts on Ireland are close to 4 times bigger than they are for France, the impacts on Estonia close to twice those on Germany.

The effects on national income reflect reduced trade. The pursuit of strategic autonomy reduces the EU exports to the rest of the world by between 0.5% and 1% on an annual basis. The losses in exports are driven primarily by the EU’s own measures, and not by partner retaliations. In essence, these measures act as a tax on external trade. Intra-EU trade increases, but by an amount that is insufficient to make up for the lost external trade. There is a reduction in imports that is similar in magnitude to lost exports. This in turn increases prices on goods and services in the EU by between 0.2% and 0.8%.

The negative effects on trade and economic activity result from the fact that the EU’s own measures depress extra-EU imports and exports, causing, for example, annual losses in total exports between some USD 30 billion and USD 65 billion. It is highlighted that certain EU policy inventions may increase trade within the EU, but this increase would be insufficient to compensate for trade lost with jurisdictions outside the EU including the US and OECD countries. In essence, it is stated, that the policy measures envisioned under strategic autonomy collectively act as an EU law-induced tax on Europe’s trade with the rest of the world.

Interestingly, costs from new subsidies and preferential public procurement policies (category 1 measures, see Table 1), aiming at strategic trade and industrial policy objectives, account for about two thirds of the estimated trade costs. By contrast, the estimated impacts of policy fragmentation in digital policymaking (category 2) and measures aimed primarily at correcting market failures relating to production methods (category 3), such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, tend to be more limited, depending on their final degree of restrictiveness and whether countries outside the EU implement or abstain from related policies. Finally, contingent measures responding to trade measures or behaviour by governments outside the EU, such as the Trade Enforcement Mechanism, the Foreign Subsidy Instrument and the International Procurement Instrument (category 4), pose significant trade costs as these measures would directly impact specific industries and trade flows respectively.

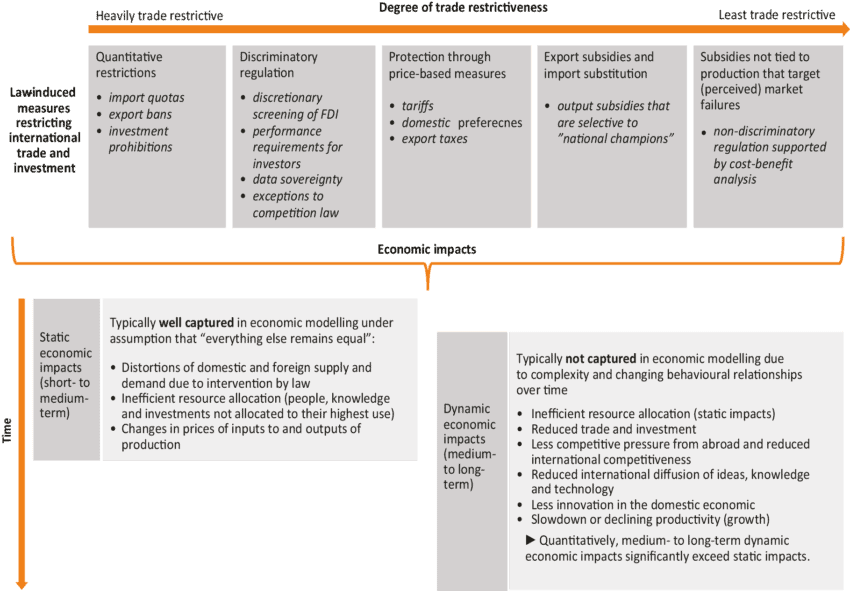

The estimated impacts likely understate the true effects of the policies since we do not deal explicitly with a range of potential impacts (e.g. a detailed treatment of impacts on incentives to innovate and invest in EU Member States in the future). Frontier’s estimates are comparative-static by nature. In simple terms, this means that the applied (econometric and general equilibrium) models do not capture important dynamic effects over time and therefore tend to understate longer-term economic costs. Static economic impacts from trade and investment restrictions result from the shifting of resources from efficient to inefficient companies or industries as trade or investment barriers rise. By contrast dynamic economic impacts are about the longer-term path of overall growth in a market, industry or country resulting from reductions of productive investment, inefficient production, and lower opportunities from exploiting international economies of scale through trade (see Figure 1 below).

The EU’s strategic autonomy policies restrict trade and competition to varying degrees. As a rule of thumb, quantitative restrictions, such as quotas and bans on imports and investments from aboard are more trade restrictive than the regulation of prices, subsidies and standards that equally apply on domestic and foreign suppliers.

However, novel and typically untested digital polices regulations, such as new data flow restrictions, data sharing obligations, taxes on digital services and limitations of business freedom in markets for digital services can have a significant knock-on effect on downstream sectors and small businesses. It is these dynamic economic impacts that EU policymakers should be most concerned about from a “strategic” point of view. Setting the wrong policy priorities today together with poorly crafted policy detail can cause long-term underperformance of investment, sluggish competition, lagging innovation, and durable productivity losses. And they can manifest longstanding productivity and technology gaps relative to other parts of the world – as in the case of the EU’s profound productivity and innovation gap versus the US.[2]

Finally, the model applied by Frontier only accounts for a limited range of retaliation by EU trading partners. If they responded tit-for-tat to the EU’s policy settings, the results would be considerably higher. To the extent that the EU’s policy stance further fragilizes rules-based multilateralism, there would be longer-term impacts stemming from a less certain legal environment for trade and investment. In addition, EU strategic autonomy policies may encourage the diffusion of protectionist policies globally, particularly in countries with weak institutional capacity. Accordingly, the estimates provide some indication of how big the welfare gains from correcting market failures need to be, à minima, to help offset the short-term costs.

Figure 1: Static and dynamic impacts from policies restricting international trade and investment and how they are captured in economic modelling

Source: own illustration inspired by research of Frontier Economics. It should be noted that some CGE models provide components that allow for the modelling of some dynamic effects, such as the evolution of prices, consumer welfare, savings and investments. However, their forecasting power is extremely limited, especially for impacts on competition, knowledge and information spillovers, technology diffusion, and factor productivity. Dynamic economic modelling of regulatory impacts over a longer period of time remains challenging and results should be treated with caution.

[1]“Frontier Economics (2022). Measuring the Impacts of the EU’s Approach to Strategic Autonomy, November 2022. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Strategic-Autonomy-Impacts.pdf.

5. Strategic autonomy: asymmetric impacts on EU Member State economies

The taxonomy outlined in Chapter 2 provides a preliminary framework to understand contemporary EU policymaking. It helps capture key motivations behind the EU’s most recent agenda. It can also help disentangle and better understand the origins, magnitudes, and distribution of costs and benefits that the strategic autonomy “acquis” can create for businesses and citizens in the Member States.

Strategic autonomy regulation is typically justified by benefits to the public, such as a higher level of consumer protection, lower prices, and reliable supply, but also ethical and environmental considerations. The costs of regulation are typically borne by the businesses that must comply with it. Costs arise from mandated changes in production, distribution, and sales practices, and from legal uncertainties related to the way regulation is designed and enforced. Regulation therefore also impacts how companies trade and compete internationally, including incentives to innovate, access to foreign knowledge and technology, and the ability to scale across borders. On top of that, there are public policy spill-over effects: regulation can be mirrored by other countries, sometimes as a means of retaliation.

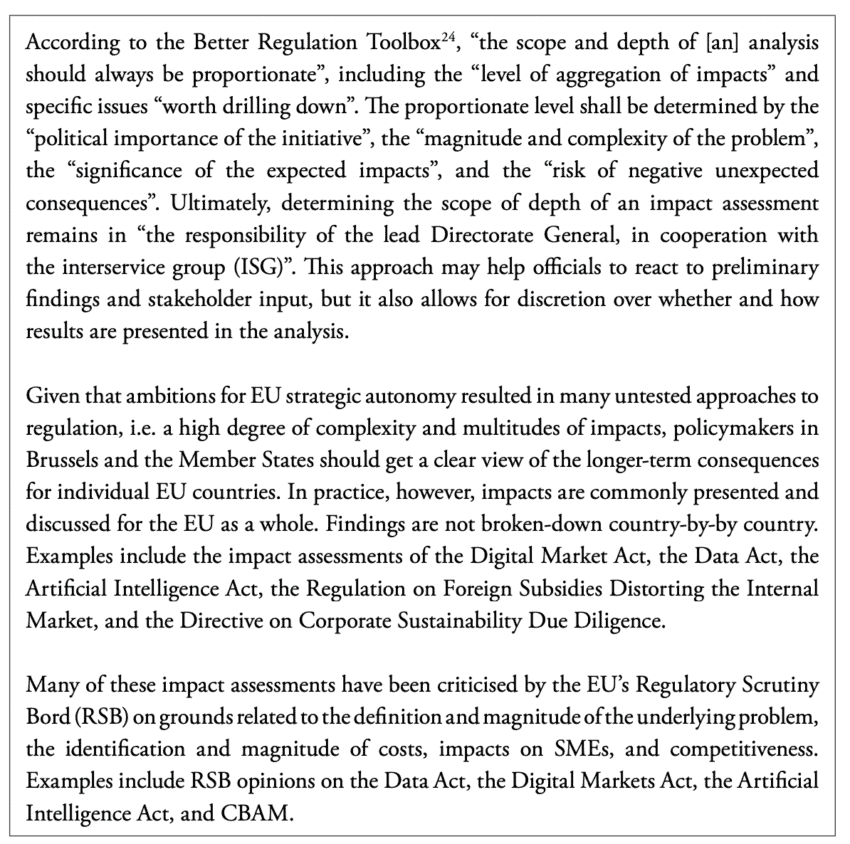

Most of these impacts are – formally – accounted for by the EU’s Better Regulation Toolbox. The Toolbox provides the official methodology for assessing European Commission-initiated laws and regulations. It is meant to ensure a solid review of potential impacts of different policy options and of those who will be affected by it.

Short-term compliance and adaptation costs are typically well-accounted for in these assessments. By contrast, indirect and long-term costs are often neglected, marginalised, or entirely ignored. This is because the toolbox provides the European Commission with great discretion over the scope and depth of impact assessments. It allows policymakers to give different weights to stakeholders’ input, and it allows them to assess the impact of new measures on the EU as a whole, without investigating benefits and costs on a country-by-country basis (see box below). Important indirect and long-term costs include changes in prices, availabilities and qualities of products and services, but also forgone investments and impacts on market access, innovation, and competitiveness.

Box 1: Discretion over the scope and depth of EU impact assessments

Long-term ambitions require an understanding of Member States’ economies and obstacles to economic development. New EU rules, bans, incentives, and deterrents can set the course for the development of EU industries and economies for a very long time. Simply speaking, in the long term, there could be winners, but there could also be losers, within the EU.

With its strategic autonomy agenda, the EU is pushing for new, often EU-only, and often untested regulation. It does so without taking into consideration the economic specificities of individual EU countries. A common assumption by policymakers is that the European Union can be treated and regulated as a single country whose regions are characterised by similar production patterns, equal access to capital, skilled labour and knowledge, and about the same level of purchasing power. But the EU is not, nor is it likely to be in the foreseeable future, a single country. EU Member States’ economic structures vary substantially across the EU, explaining differentials in the path of economic development, citizens’ preferences for international trade and investment, and the actual readiness of companies to comply with new EU regulation.

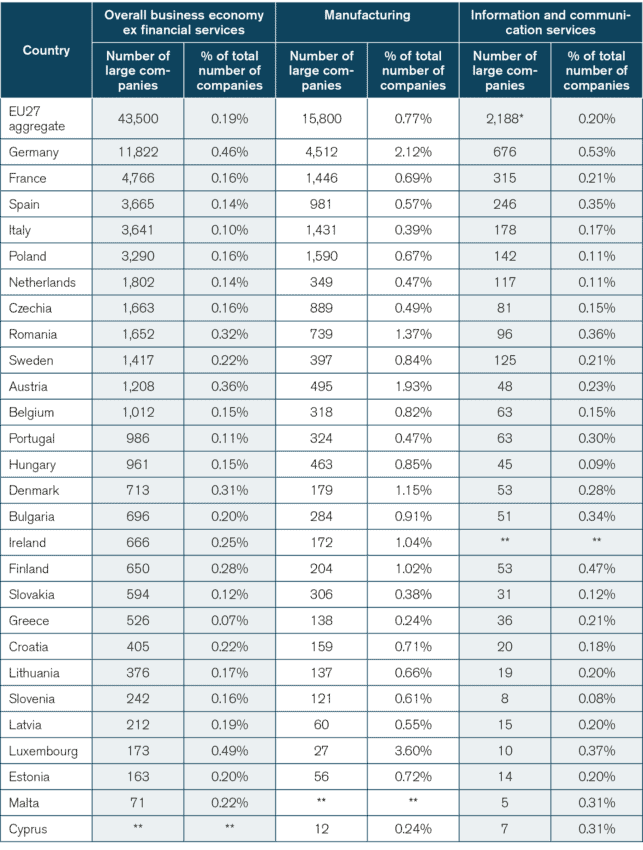

A look at the EU’s structural business characteristics database reveals that large Western European Member States are home to a much larger number of big businesses compared to small EU countries (see Table 3). Large companies are generally much better equipped to adapt and comply with new regulatory requirements. Some large companies may even benefit from policy-induced entry barriers as they reduce exposure to competition and contestability (incumbent protection). EU impact assessments are typically silent about these effects.

Table 3: Distribution of large companies in EU27 countries in industries key to the EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm Source: Eurostat annual enterprise statistics by size class for special aggregates of activities (NACE Rev. 2). Large companies: companies with 250 persons employed or more. * 2016 value. ** indicates data gap.

Source: Eurostat annual enterprise statistics by size class for special aggregates of activities (NACE Rev. 2). Large companies: companies with 250 persons employed or more. * 2016 value. ** indicates data gap.

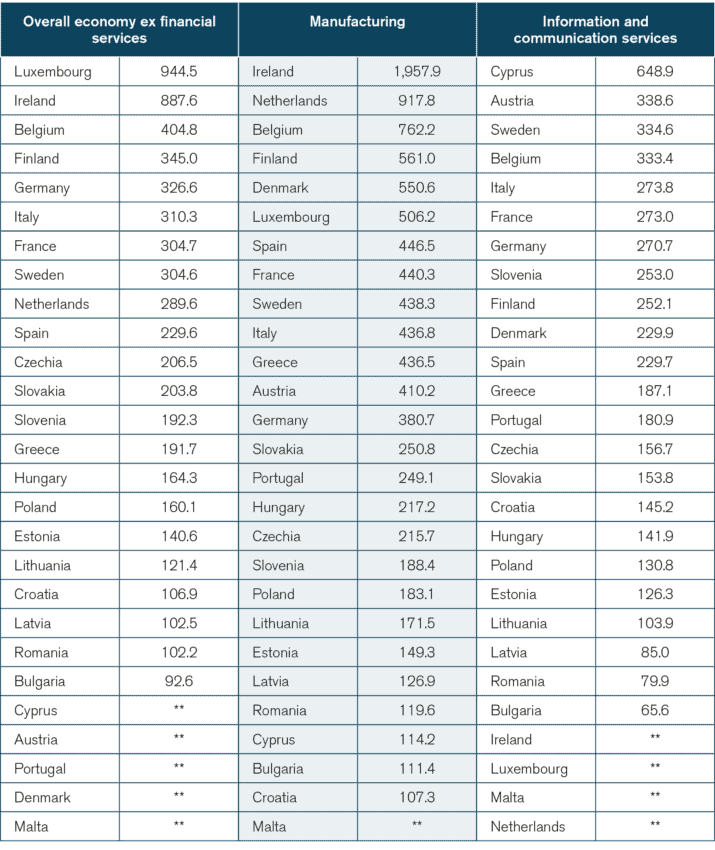

Large companies in large Western European Member States are generally much more productive and internationally competitive compared to companies in small EU countries, notably in sectors that are targeted by key strategic autonomy initiatives, such as manufacturing and ICT industries. Big businesses in France and Germany, for example, show significant comparative advantages compared to companies from economically less developed EU countries, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE, see Table 4). At the same time, smaller countries in Western Europe and the Nordics are home to some of the most competitive large companies in the EU and globally, particularly in technology-intensive sectors such as the biopharmaceutical industry, advanced manufacturing, and ICT. These patterns are also reflected in the location of large R&D-driven companies in the EU. As shown by the EU’s latest investment scoreboard, 124 of the world’s top 2,500 R&D investors are based in Germany and 66 in France. 34 each are registered for the Netherlands and Sweden. Only two are based Portugal and one in Slovenia, Hungary, and Poland respectively.[2]

Table 4: Turnover per person employed of large companies in EU27 countries in industries key to the EU’s strategic autonomy paradigm Source: Eurostat annual enterprise statistics by size class for special aggregates of activities (NACE Rev. 2). Large companies: companies with 250 persons employed or more. ** indicates data gap.

Source: Eurostat annual enterprise statistics by size class for special aggregates of activities (NACE Rev. 2). Large companies: companies with 250 persons employed or more. ** indicates data gap.

The regional and sectoral distribution of companies in the EU has implications for the size and distribution of benefits and costs across the Member States. These costs go beyond direct compliance costs. Complex rules for new products and services or data create a multitude of downstream economic effects, notably for SMEs.[3] SMEs account for much higher shares of economic activity in small EU Member States compared to large EU countries. For example, a European Cloud Certification Scheme together with restrictions on the transfer of data would likely increase the economic clout of large incumbent companies in large Western European countries but increase small businesses dependencies on them. It would reduce choice and economic opportunities in small countries and impede the process of economic convergence in the EU. Subsidies are another case in point: the Chips Act (for which “an impact assessment could not be prepared due to the urgency of an initiative”) would disproportionally benefit incumbents and investors in large EU Member States, at the cost of businesses and taxpayers in small EU Member States.

New initiatives towards “European standards” and the management of “EU value chains” could also disproportionally impact small EU Member States. A recent study from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy focuses on increasing market access barriers in the EU and regulatory heterogeneity (regulatory decoupling).[4] The authors investigated the trade impacts from preferential public procurement rules, tax breaks, other subsidies for EU suppliers, as well as import quotas and bans on selected goods. Large countries with a high exposure to international trade, such as Germany and France, would indeed suffer high absolute losses in domestic production and trade. At the same time, small countries, such as Ireland, Malta, Belgium and the Baltics, would be more strongly affected in relative terms, with losses being largest if non-EU countries were to mirror EU policies or retaliate. Small businesses in the EU will find it harder to do business in non-EU countries if governments increase market access barriers through new regulation of regional standards that are difficult to comply with (prohibitive). Negative impacts from regulatory diffusion and retaliation, which accumulate over time, are usually ignored in EU impact assessments.

The global economy is constantly undergoing a process of transformation, becoming more digital, more collaborative, and producing a larger diversity of products, services, and technologies. Many policymakers in Brussels take a command-and-control view on autonomy and regional sovereignty, arguing that the EU or individual Member States need to have the policy instruments to control the outcomes of economic transformation and how Europeans do business and use data and technologies. Policies that originate from this hypothesis can have a lasting impact on Member States’ economies.

EU impact assessments so far fail to provide a prudent picture of the long-term impacts that result from new EU initiatives and regulations. Policymakers in small EU Member States should not make any far-reaching decisions based on EU impact assessment reports that ignore, obscure, or downplay these impacts. They should start challenging the European Commission’s discretion over the depth and scope of regulatory impact assessments. EU governments should insist on detailed country-by-country assessments addressing key questions for long-term ambitions (see Box 1).

[1] European Commission (2021). Better Regulation Toolbox, November 2021. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/br_toolbox-nov_2021_en_0.pdf.

[2] European Commission (2022). The Single Market Scoreboard. Available at https://single-market-scoreboard.ec.europa.eu/integration_market_openness/trade-goods-and-services.

[3] ECIPE (2022). After the DMA, the DSA and the New AI Regulation: Mapping the Economic Consequences of and Responses to New Digital Regulations in Europe. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/after-dma-dsa-ai-regulation-mapping-the-economic-consequences-eu/.

[4] Kiel Institute for the World Economy (2021). Pursuit of economic autonomy can be costly for EU countries, 30 July 2021. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/media-information/2021/pursuit-of-economic-autonomy-can-be-costly-for-eu-countries/.

6. Strategic autonomy: impacts on multilateralism and the freedom to trade internationally

Measured by many initiatives in the realm of economic and technology policymaking, the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda is a backward-looking endeavour. It risks becoming a blueprint for economic nationalism globally – a justification for governments outside Europe, especially developing countries, to erect new trade and investment barriers on their own.

With its recent communiqué on “Open Strategic Autonomy”, the European Commission is reconsidering its trade and investment priorities to better and more assertively drive a process towards “fairer and more sustainable globalisation”. While autonomy and fairness in economic life might be what populations legitimately decide they prefer, proceedings in Brussels often bring to life laws that run counter to fairness and resilience, and the ability to act independent from other countries’ areas of strategic importance.

EU policymaking often seeks to intervene on contested grounds rather than striving for better regulatory approaches and policies that are accepted by like-minded partner countries. Take taxes on digital services (recently coined EU digital levy) as an example. Several studies on the impact of a tax on digital services find that the tax is financially borne by firms buying online advertising services, marketplace listings, or user data, and the consumers downstream from those transactions. It does not come as a surprise that most OECD countries including the US oppose this type of tax. At the same time, developing and emerging market economies such as India and Kenya, inspired by the EU’s original template, implemented, or take into consideration taxes on modern digital services.

With its strategic autonomy acquis, EU policymakers not only risk decoupling Europe economically by reducing the openness and exposure of EU industries to international competition and innovation, they also risk decoupling the EU politically by pushing a regulatory agenda that will in many cases not be mirrored by major partner countries, such as the larger group of economically developed OECD countries. With new subsidies, discriminatory industrial policymaking, and the inflated use of values as an excuse for unique EU action, the EU is paving the way for more government intervention and fewer binding rules in the global economy.[1]

Take subsidies as an example. Subsidies are more than sand in the wheels of trade and investment. They have an impact on economic diplomacy and ambitions for international policy cooperation. As recently highlighted by the OECD, “the growing use of distortive subsidies alters trade and investment flows, detracts from the value of tariff bindings and other market access commitments, and undercuts public support for open trade.” Distinguishing “good” and “bad” subsidies is analytically and politically fraught.

A case in point is the current conflict over US subsidies for electric vehicles and discriminatory treatment of foreign carmakers as part of the US Inflation Reduction Act. In economic terms, it is a comparatively insignificant dispute.[2] However, it is reported to have held back more important talks and negotiations in the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC), which is intended to ensure cooperation on key challenges in international trade and technology policymaking, based on shared democratic values and respect for human rights.[3]

Subsidies generally undermine the principles, rules and commitments made in trade agreements and WTO law. Due to their frequency, size and complexity, subsidies have in the past brought significant discord to the international rules-based trading system. New industrial policies to promote strategic industries, such US and European chips and car makers, distort international competition and disadvantage smaller and fiscally more constrained developing countries. This is of particular concern with regard to developing countries, where governments’ appetite for discriminatory treatment of foreigners and measures in support of strategic industries is generally high.[4]

By rushing ahead with new subsidies under the umbrella of strategic industrial policymaking, the EU puts itself in the driver’s seat in the process of undermining the rules-based trading system. It effectively empowers others to follow suit, backfiring on the ambitions of EU development cooperation and the advancement of its Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the world’s least developed countries. If EU policies give greater power to EU incumbents, this is the perfect springboard for similar policies to be adopted in the developing countries with which the EU partners.

The EU’s strategic autonomy agenda is built on the perception that economic prosperity, technological leadership, and geopolitical power are a function of more and more targeted government intervention. However, no government or agency thereof has ever had superior expertise in steering economic activity in a way that its domestic economy or certain industries outperform the rest of the world. If there is one rule for follow for wide and broad economic success, it is the fundamental commitment to maintaining economic freedom.

This is not to say that there are no good grounds for strategic autonomy ambitions, but EU policymakers need to recognize the trade-offs between isolationist regulatory approaches by the EU and regulatory trends outside Europe, on top of the cost created for Europeans themselves. And they need to factor in the serious adverse impacts from strategic autonomy legislation on the international trading system, including the effectiveness WTO rules.

The history of economic cooperation suggests that it will become very difficult for the EU to achieve strategic autonomy objectives and at the same time preserve an open international trading system that is embedded in continuous efforts for regulatory cooperation and accepted multilateral commitments.

[1] Peterson Institute (2022). The European Union renews its offensive against US technology firms. Available at https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/european-union-renews-its-offensive-against-us-technology-firms.

[2] OECD (2022). Subsidies, Trade, and International Cooperation, 22 April 2022. Available at https://www.oecd.org/publications/subsidies-trade-and-international-cooperation-a4f01ddb-en.htm.

[3] European Commission (2022). EU-US Trade and Technology Council. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-us-trade-and-technology-council_en.

[4] Fraser Institute (2022). Economic Freedom of the World, 2022 Annual Report. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2022.pdf.

7. Strategic autonomy: the role of Europe’s fragmented Single Market

January 1, 1993, marks the date of the formal establishment of the “European Single Market”. 30 years since its dawn, the Single Market is to the largest extent incomplete. EU legislation has expanded tremendously over the past decades, but common and uniformly applied EU policies are still the exception rather than the rule. EU Member States keep sticking to their own versions of horizontal and sector-specific laws.

This is at odds with the current zeitgeist in Brussels. In her State of the Union address from September 2020, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen reiterated that Europe’s “Single Market is all about opportunity – for a consumer to get value for money, a company to sell anywhere in Europe and for industry to drive its global competitiveness.”[1] Likewise, European Commission Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager highlighted that only a common European market gives European businesses room to grow and to innovate. Referring to Europe’s underperformance in digital industries, Mrs Vestager stated that “[o]ne of the reasons why we don’t have a Facebook and we don’t have a Tencent is that we never gave European businesses a full single market where they could scale up […] Now when we have a second go, the least we can do is to make sure that you have a real single market.”[2]

The Single Market is often said to be the EU’s greatest achievement. Indeed, since the 1980s, Europe’s common market advanced in many impressive ways. Inspired by the principle of mutual recognition for goods, Brussels and most Member State capitals kept cultivating a political climate that in general embraces the idea of a borderless European market for goods and services, capital, and workers. And yet, the Single Market is to the largest extent incomplete, lacking common and uniformly applied EU policies in economic and social policymaking.

About a decade ago, at the time of its 20th anniversary, EU officials already recognised a crisis of the Single Market.[3] Following the conclusions of the famous Monti Report of 2010 (A new strategy for the Single Market: At the service of Europe’s Economy Strategy)[4], many saw an urgent need for action to create a real European level-playing field for businesses and workers. The integration fatigue, however, continued to prevail.

EU policymaking has so far been characterised by an inflation of Directives which allow for national discretion in implementation and enforcement. New layers of EU regulation create an unparalleled patchwork of horizontal and sector-specific Member State laws. For businesses and consumers, the Single Market remains a complex web of business, tax, and labour regulations, which vary from country to country, creating confusion and legal uncertainties. In 2016, a report by the European Parliament found that the “costs of a slow reform process and vague initiatives with uncertain time horizons in the area of e-commerce alone amount to EUR 748 billion.“[5]

Disintegration and the costs of international policy fragmentation

In light of the EU’s sustained Single Market Disease, strategic autonomy aspirations represent a relapse of the EU to the old policy of EU member states designing and enforcing their own laws without considering the economic and political costs of regulatory fragmentation and economic disintegration from others.[6] With new and unique EU rules for specific industries, digital services and competition, the EU risks decoupling Member State economies from the rest of the word.[7] It risks harming EU economic activity in two ways: by erecting new regulatory hurdles for businesses operating in EU Member States and by creating a regulatory landscape in the Member States that is difficult to navigate for exporters and foreign investors, especially small businesses.

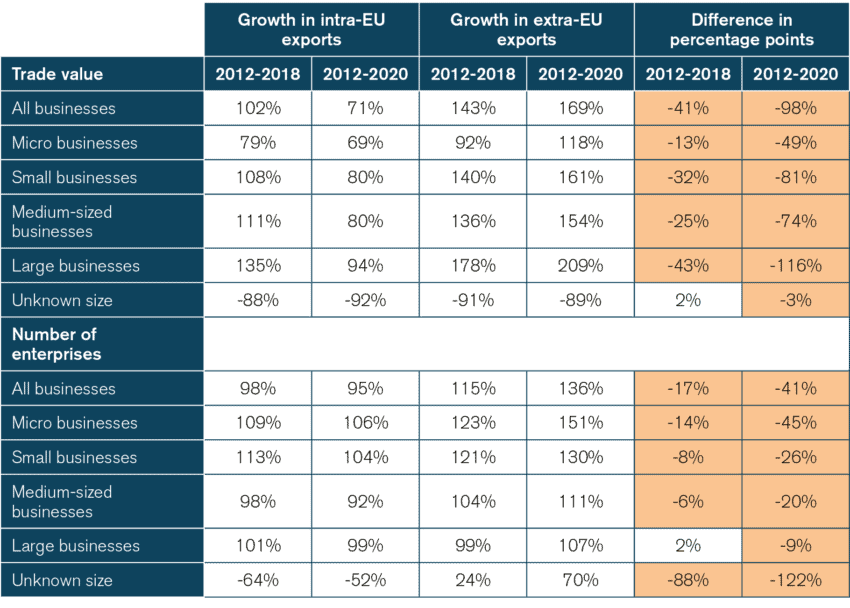

Ever since 1993, harmonising regulation has been a cat-and-mouse game: when old national approaches to regulation have been knocked down, new ones have risen elsewhere in the economy. Especially, with the structural change of the economy – leading to a greater role for services and digital output – the result became a European market that remains fragmented and that still comes with high costs of doing business across internal borders. Unsurprisingly, intra-EU goods trade by all those that are sensitive to regulatory differences, including small- and micro-sized businesses, has failed to grow significantly when compared to exports to markets outside the EU (see Table 5).

Table 5: Underperformance of intra-EU goods trade versus extra-EU goods trade, trade value and number of trading enterprises by size class Source: Eurostat. Note that values presented for the period 2012-2018 aim to capture pre-COVID-19 growth.

Source: Eurostat. Note that values presented for the period 2012-2018 aim to capture pre-COVID-19 growth.

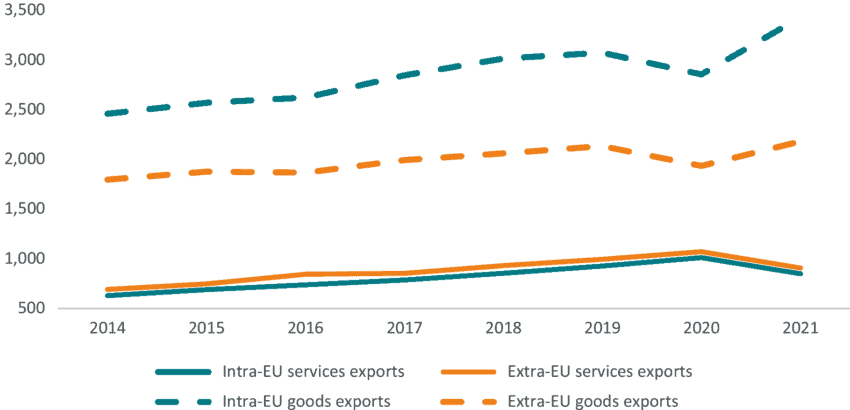

Services sectors, which together account for 65% of EU27 GDP, are another case in point. As shown by Figure 2, intra-EU services exports show the same growth trend as extra-EU services exports. Contrary to intra-EU trade in goods, which outperforms extra-EU trade (with non-EU countries), intra-EU services exports only kept growing in line with trends in global demand. In many services sectors, national policies, disproportionate regulatory restrictions and weak competition are preventing consumers and firms from harnessing the full benefits of EU integration.[8]

Figure 2: Development of intra-EU and extra-EU goods and services exports, 2014-2021, in EUR bn Source: Eurostat.

Source: Eurostat.

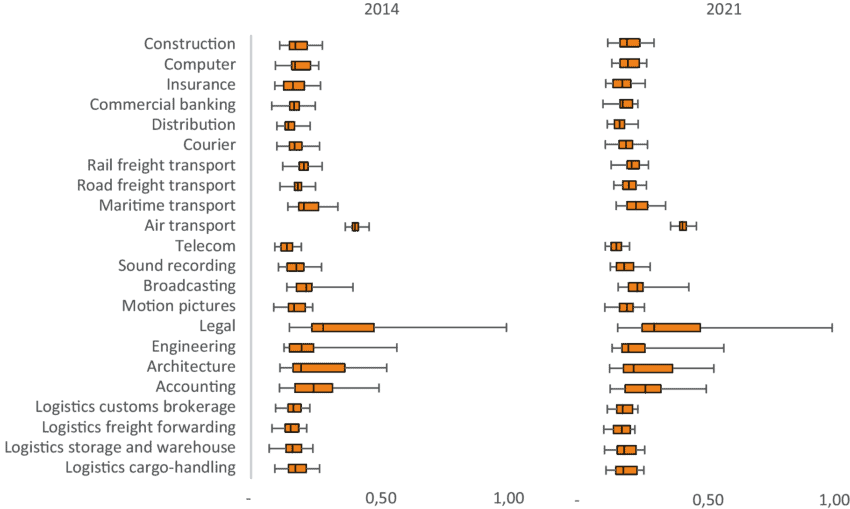

For construction and logistics to computer and telecommunications services, OECD services trade restrictiveness data demonstrates that Europe’s Single Market did not advance during the past decade. EU policy has not succeeded in harmonising the rules for services, let alone in initiating a process of liberalisation and convergence. In most services sectors, Member State regulations became more restrictive, both at the lower and the upper end of the restrictiveness spectrum.

In many services sectors, Member States are still free to determine their own regulation and how open they want to be for imports from other EU countries (see Figure 3 and Table 6). Take telecoms, for example: The EU currently does not have a unified mobile telecommunications market, which hampers the deployment of broadband and 5G in the Member States.[9] Other examples are differences in access conditions in markets for regulated professions, education, broadcasting, logistics services (e.g. freight cabotage[10]), and healthcare services. Similar trends can be observed for many product markets regulations (PMR)[11] and, importantly, horizontal policies, such as sales taxes and VAT, corporate taxes, labour market policies, and environmental standards in the Member States.

Countless studies confirm that regulatory complexity is challenging for any business, especially SMEs. For example, the SME Envoy Network highlights that “the Single Market is neither perfect nor complete”.[12] Member State law is characterised by an increasing number of new regulations, overlapping policies escalating the complexity of EU and Member States’ legal frameworks. Each year, as noted by the authors, “the amount of national technical regulation keeps piling up which makes it more difficult for SMEs to expand their activities across Europe. At the European level, SMEs also experience confusion from partially overlapping rules. This means that SMEs do not necessarily know which rules apply to them – they simply do not understand which rules to follow.”

Figure 3: Statistical distribution of regulatory restrictiveness in EU services sectors in 2014 and 2021 Source: OECD STRI database. Bars represent EU sample minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and maximum values.

Source: OECD STRI database. Bars represent EU sample minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and maximum values.

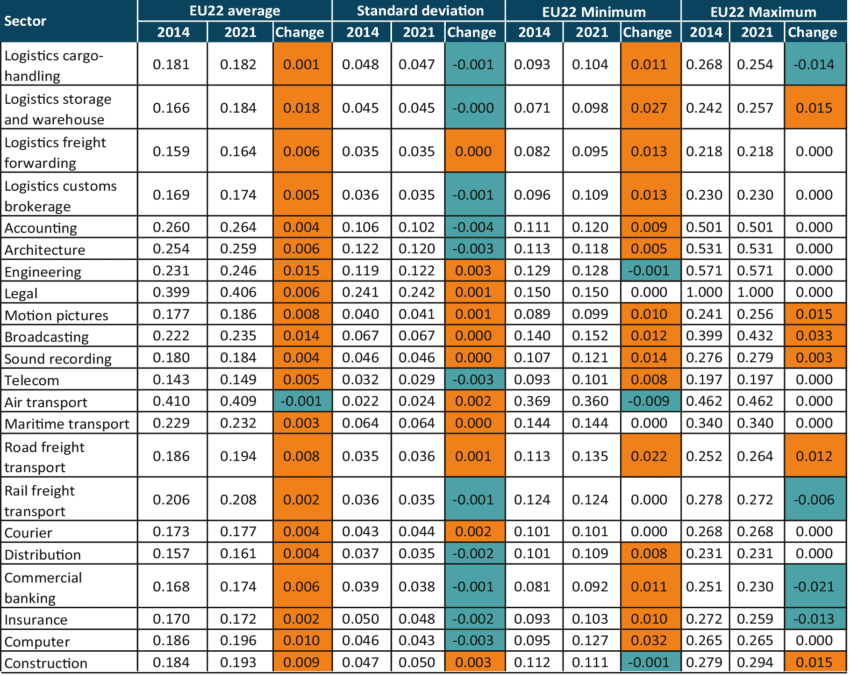

Table 6: Development of EU services trade restrictiveness and regulatory fragmentation, 2014 to 2021 Source: OECD STRI database. Red fill indicates increase in regulatory restrictiveness and regulatory heterogeneity respectively.

Source: OECD STRI database. Red fill indicates increase in regulatory restrictiveness and regulatory heterogeneity respectively.

The EU’s “Business Gap” vis-à-vis the US

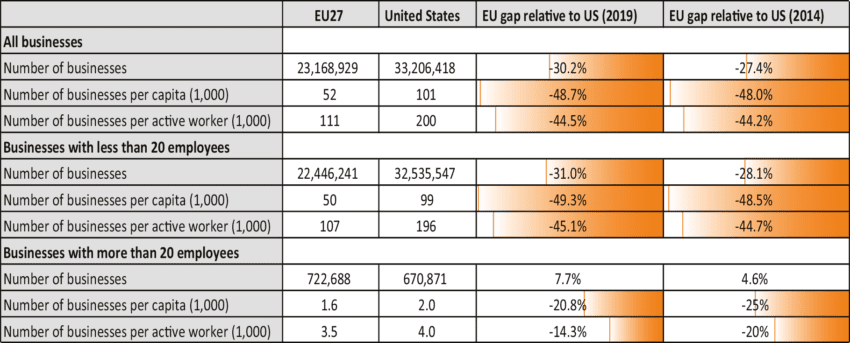

The lack of harmonised rules does not help the EU in catching up with business, competition and innovation dynamics in other major jurisdictions such as the US (and China – whose GDP will be more than twice as high as EU GDP in 2050).[13] Business statistics demonstrate that despite a much smaller labour force, the US is home to a much higher number of businesses than the EU. The EU’s deficit in the absolute number of established businesses relative to the US was 30% in 2019, increasing from 27% in 2014. It amounts to close to 50% on a per capita basis. In other words, the number of businesses per capita in the US is twice as high as in the EU. The EU’s deficit in SMEs with less than 20 employees is even higher, increasing from 48.5% in 2014 to 49.3% in 2019 (see Table 7).

Due to differences in the definition of large companies, it is difficult to depict precise trends and patterns for large and very large businesses. However, data suggest that the average number of employees of a large US company (300 employees or more) is about twice as high as the average number of employees of a large company that is based in the EU (companies with 250 employees or more), indicating that it is much easier for US companies to scale up than for companies in the EU.[14] Adding EU policy fragmentation, it does not come as a surprise that the number of European scale-ups is still less than a third of those in the US.[15] Europe is expected to face a large and growing corporate performance challenge, reflected in lower productivity, lower profit margins, lower investments, and less tech creation compared to US counterparts.[16]

Table 7: The EU’s “Business Gap” vis-à-vis the US Source: Eurostat and US Census. Eurostat data taken from the annual enterprise statistics by size class for the entire business economy ex financial and insurance services. US Census data extracted from the Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) and US Non-employer Statistics (NES) databases. Eurostat data include micro businesses (0-9 employees). NES data represent businesses that are reported to have no paid employees.

Source: Eurostat and US Census. Eurostat data taken from the annual enterprise statistics by size class for the entire business economy ex financial and insurance services. US Census data extracted from the Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) and US Non-employer Statistics (NES) databases. Eurostat data include micro businesses (0-9 employees). NES data represent businesses that are reported to have no paid employees.

Empirical research is clear about the costs created by regulatory barriers that prevent, stifle, or even eliminate imports and investments from abroad. As is shown by the mapping of the cost of non-Europe by the European Parliamentary Research Service, the consequences are higher cost of doing business in the Member States, less opportunities for exploiting economies of scale, and depressed entrepreneurial churn.[17] On top of that, there are substantial medium- to long-term dynamic impacts that cannot easily be quantified, such as reduced competitive pressure and international competitiveness, less diffusion of knowledge and technology, fewer incentives to innovate, and, eventually, slowed-down structural economic change and renewal. These costs also accrue from key strategic autonomy policies.

It is startling that new EU policy initiatives under the label of strategic autonomy, such as the Data Act, the AI Act, the Certification Scheme on Cloud Services, the Digital Market Act, the Digital Services Act or the investment screening mechanism, are typically presented as initiatives to improve and “complete“ the Single Market. However, these (proposed) laws will add new costs for businesses including for SMEs, which intensively use modern digital services. And these new laws will in many cases not be implemented equally and consistently across EU Member States, creating more uncertainty about rules for doing business in the EU.[18]

Another detrimental effect is that that these laws distract public attention and political capital away from areas in which more Single Market is needed for Europe to thrive on borderless trade, competition, and innovation. Several studies on the state of the EU – its productivity[19], technology and investment[20] gap – point to similar patterns, also referred to as a slow-motion corporate and technology crisis[21].

Need for a Real Single Market

Strategic Autonomy has emerged as an influential concept for EU policymaking. It is partly intended to improve EU value chains, partly to deal with new growth poles that challenge the EU’s economic position, some with different economic models, and notably China.[22] However, many policymakers in Europe still have a confused vision about the policy conditions required for Europe to grow its economy and technological capacities. A conventional wisdom that has emerged over the past years supposes that whatever economic underperformance that can be ascribed to Europe is a consequence of the superior performance of US technology companies, which, so the story goes, are simply too competitive or too innovative for Europe’s economy to prosper on the back of indigenous innovation.

The most pressing structural impediment for European businesses to develop and reach scale is not necessarily the level of policy restrictiveness, but the level of regulatory fragmentation across EU Member States. Due to fragmented regulatory frameworks in many horizontal and (services) sector-specific policies, it is difficult for innovative businesses to contest traditional industries, e.g., by digitalising old-economy business models.

At the same time, powerful incumbents that have successfully adopted national laws and regulatory procedures often prevent regulatory change. Regulatory fragmentation and incumbency protection are intertwined. Both can be major sources of inefficient resource allocation in many industries – irrespective of whether they find themselves in primary sectors, manufacturing, or services industries.

The paramount task for European policymakers to achieve Strategic Autonomy objectives should be to eliminate policy fragmentation that holds European business models back from transforming European economies faster to become more competitive.

[1] European Commission (2020). State of the Union Address 2020. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/soteu_2020_en.pdf.

[2] Politico (2020). Vestager touts AI-powered vision for Europe’s tech future, 17 February 2020. Available at https://www.politico.eu/article/margrethe-vestager-touts-ai-artificial-intelligence-powered-vision-for-europe-tech-future/.

[3] Bruegel (2010). A Single Market crisis1 11 July 2010. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/single-market-crisis.

[4] Ceplis (2010). Analysis of Professor Mario Monti’s report: “A new strategy for the Single Market: At the service of Europe’s Economy Strategy” – Some Suggestions on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications. Available at https://ceplis.org/analysis-of-professor-mario-montis-report-a-new-strategy-for-the-single-market-at-the-service-of-europes-economy-strategy-some-suggestions-on-the-mutual/.

[5] European Parliament (2016). Reducing Costs and Barriers for Businesses in the Single Market – Study for the IMCO Committee, April 2016. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/578966/IPOL_STU(2016)578966_EN.pdf.

[6] American Enterprise Institute (2017). Right Direction, Wrong Territory. Why the EU’s Digital Single Market Raises the Wrong Expectations, March 2017. Available at https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Right-Direction-Wrong-Territory.pdf?x91208.

[7] Kiel Institute for the World Economy (2021). Pursuit of economic autonomy can be costly for EU countries, 30 July 2021. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/media-information/2021/pursuit-of-economic-autonomy-can-be-costly-for-eu-countries/.

[8] European Commission (2022). The Single Market Scoreboard. Available at https://single-market-scoreboard.ec.europa.eu/integration_market_openness/trade-goods-and-services.

[9] GSMA (2022). The Mobile Economy Europe 2022. Available at https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/051022-Mobile-Economy-Europe-2022.pdf.

[10] European Commission (2022). Rules on cabotage as applicable from 21 February 2022. Available at https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-modes/road/mobility-package-i/market-rules/rules-cabotage-applicable-21-february-2022_en.

[11] OECD (2022). Indicators of Product Market Regulation. Available at https://www.oecd.org/economy/reform/indicators-of-product-market-regulation/.

[12] SME Envoy network (2018). Barriers for SMEs on the Single Market, November 2018. Available at https://danishbusinessauthority.dk/sites/default/files/barriers_for_smes_on_the_single_market.pdf.

[13] PWC (2022). The World in 2050 – The long view: how will the global economic order change by 2050? Available at https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/research-insights/economy/the-world-in-2050.html.

[14] European Commission (2021). European scale-up gap – Too few good companies or too few good investors?, 20 December 2021. Available at https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/knowledge-publications-tools-and-data/publications/all-publications/european-scale-gap-too-few-good-companies-or-too-few-good-investors_en.

[15] European Parliament (2021). Europe’s Digital Decade and Autonomy, October 2021. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/695465/IPOL_STU(2021)695465_EN.pdf. European Parliament (2021). Europe’s Digital Decade and Autonomy, October 2021. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/695465/IPOL_STU(2021)695465_EN.pdf.

[16] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness: Addressing its technology gap, 22 September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap?stcr=7BB2FA3B0A6547E8BF7C485899DE52C7&cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=8b2faf1189d9445c8ef0509d68549ca3&hctky=3177063&hdpid=f16caf25-b86f-47f0-a808-d964bcd1438a.

[17] European Parliament (2019). Europe’s two trillion euro dividend – Mapping the Cost on Non-Europe 2019-2024, April 2019. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/631745/EPRS_STU(2019)631745_EN.pdf.

[18] ECIPE (2022). The EU Digital Markets Act: Assessing the Quality of Regulation. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ECI_22_PolicyBrief-TheEuDigital_02_2022_LY03.pdf.

[19] Bruegel (2022). The Low Productivity of European Firms: How can Policies Enhance the Allocation of Resources? Available at https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/WP-06.pdf.

[20] European Commission (2021). 2021 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard remains robust in ICT, health and green sectors, 2021 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard, 17 December 2021. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_6599.

[21] McKinsey (2022). Securing Europe’s competitiveness: Addressing its technology gap, 22 September 2022. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap?stcr=7BB2FA3B0A6547E8BF7C485899DE52C7&cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=8b2faf1189d9445c8ef0509d68549ca3&hctky=3177063&hdpid=f16caf25-b86f-47f0-a808-d964bcd1438a.

[22] Institute for International Trade (2022). The future of EU trade policy and strategies in a militarised environment, September 2022. Available at https://iit.adelaide.edu.au/system/files/media/documents/2022-09/wp11-the-future-of-eu-trade-policy-in-a-militarized-environment-final.pdf.

8. Concluding remarks and policy recommendations

Contrary to reaching military strength, improving economic opportunities, competition and broad technological progress are far less dependent on prescriptive behavioural policies and strategic state aid. Successes in the domestic economic innovation and international trade critically hinge on rules that allow for economic freedom, open markets, and vivid competition – the cornerstones of a functioning market economy that in the past also contributed to the dissemination and stability of democratic norms globally.[1]

Any strategic economic and technology policy ambition to increase Europe’s capacity to act should aim at increasing the abilities of individuals and firms. For a country or a regional entity like the EU, the capacity to effectively shape outcomes at home and globally – to increase autonomy – depends crucially on policies that harness the energy and ingenuity of many actors. The same conclusion holds for technology and innovation capacities: EU Member States’ capacity to prosper on the back of technology comes from the ability of individuals, firms, and governments to deploy global frontier technologies and technology-enabled business models in many different ways.

A political program recognising individuals and firms’ capabilities rather than jurisdictional autonomy will inevitably have to start with the provision of education and human capital. It also requires a strong, perhaps unprecedented emphasis on knocking down regulatory barriers and overly complex taxation in Europe’s incomplete Single Market, which currently prevent the easy traverse of technologies, goods and services across borders, and hinder European companies, including start-ups, to scale up and become globally relevant.

The economic weight and gravity of Europe in the world is shrinking. Thirty years ago, the EU represented roughly a quarter of global GDP. It is foreseen that in 20 years, the EU will not represent more than 11%, far behind China, which will represent double it, below 14% for the US and at par with India. Neither the EU nor the US will be able to rely on their own market size as the main source of maintaining political influence in the global economy. Other countries, e.g. Japan, are confronted with the same reality. Sure, the EU will likely remain an influential geopolitical actor in global economic policymaking. The “Brussels effect” will likely continue to prevail: the world’s largest corporations will continue to seek access to the EU’s large market by adjusting business conduct and production standards. But with falling relative economic power, Europe will have to improve its capacity to influence global rules by being home to innovative companies. It is not possible to reduce global dependence at the same time as one’s relative economic size is falling.

When quantity does not count in the EU’s favour anymore, at least not in the way it used to do, the EU will have to improve regulatory conditions at home to encourage economic opportunity and innovation and become an example that others want to follow. The Single Market is a strong source of autonomy and influence – it needs to deepen for autonomy to increase. Size and economic gravity matter. With a larger economy that allows for cross-border commerce and technology development, the EU can make itself more attractive as a place to innovate and develop the future economy. And with more economic clout, the EU will also have a stronger voice to influence global norms and standards for technology.

Strategic autonomy ambitions have largely failed to account for adverse impacts on developing countries. In many instances, such as the regulation of data, digital business models, taxation, environmental policies, and technical standards, EU policies either increase the cost of doing business in Europe or explicitly or implicitly discriminate against foreign suppliers. These policies have the effect of generating fewer opportunities for small businesses and suppliers from developing countries, empowering vested interests, such as national incumbents, to engage in lobbying for protectionist policies, and contributing to the diffusion of protectionist policies globally, particularly in countries with weak institutional capacity.

Therefore, strengthening international efforts for trade and regulatory cooperation should be the core component of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda. Regulatory cooperation with allies such as the US and the larger groups of OECD countries is essential to jointly set global standards based on shared values and fundamental rights. At the same time, EU legislators need to account for and preclude negative impacts on developing countries’ trade and technology policymaking and multilateral commitments. EU policymakers need to uphold open trade principles rather than EU-first policies.

EU Member States should examine their options and ask themselves whether there are better long-term strategies to pursue than those currently proposed at the EU level, strategies guided by the spirit of the open society – a society embracing the principles of free trade, non-discrimination, and economic freedom. Europe’s policymakers should aim for closer market integration and regulatory cooperation with trustworthy international partners such as the G7 and the larger group of the OECD countries. It is in the EU’s self-interest to advocate for a rules-based international order with open markets. It is neither in the EU’s economic nor its political interest to disintegrate from the partner countries.

Policy recommendations:

Account for the size and distribution of economic costs of strategic autonomy policies:

- A common assumption by policymakers in Brussels is that the EU can be treated and regulated as a single country. It can’t. Member States are characterised by vast differences in the composition of large and small businesses and their production capacities, differences in access to capital, skilled labour and knowledge, and different levels of purchasing power.

- According to the EU’s Better Regulation principle, new EU laws should only be implemented where the benefits are likely to outweigh associated costs.

- The Better Regulation Toolbox provides the European Commission with great discretion over the scope and depth of impact assessments.

- EU impact assessments are biased towards playing down adverse long-term impacts for EU economies and tend to conceal the costs for individual Member States. Policymakers in Brussels and the Member States should challenge the EU’s impact assessment toolkit, which does not adequately take into account important long-term impacts of new EU regulation, notably strategic autonomy legislation.

- EU governments should insist on detailed country-by-country assessments for the EU27 answering key questions on strategic ambitions.

Work towards a “Real Single European Market” for goods, services and workers

- 30 years after its establishment, the EU’s Single Market is incomplete. This may hinder the European Commission’s Strategic Autonomy agenda.

- The von der Leyen Commission expressed strong political commitment to deepen the Single Market, but EU institutions and the Member States must overcome the Single Market fatigue.

- Economic and technology indicators blatantly reveal that the EU27 is in a slow-motion corporate, productivity and technology crisis.

- The number of companies per capita in the US is twice as high as in the EU. Companies in the EU find it much harder to grow and scale compared to US companies.

- Contrary to other large markets, 24 national languages pose a natural barrier to cross-border commerce in the EU. The deterrent effect of language on cross-border business activity is amplified by differences in horizontal and sector-specific regulations.

- Differences in language and national rules for businesses and workers leave Europe with a structural disadvantage in a world where innovation and economic growth is increasingly generated outside EU Member States.

- A real continent-sized market would create conditions for more innovations and underpin EU ambitions for strategic autonomy, standard-setting power, and technological leadership.

- The paramount task for European policymakers to achieve Strategic Autonomy objectives should be to eliminate policy fragmentation that holds European business models back from transforming European economies faster to become more competitive.

- A coalition of willing governments, ideally the EU membership as a whole, needs to work towards a full harmonisation of sectoral and horizontal policies to foster trade, investment and innovation in the Member States.

- A real Single Market would increase Europe’s economic clout in the world. Politically, Europe could gain a stronger voice to influence future norms for trade and standards for technology at a time where other jurisdictions inexorably increase economic capacities and technological capabilities.

Work towards non-discrimination and trade openness in other parts of the world

- EU strategic autonomy policies include a wide range of subsidies, policies aimed at correcting proclaimed market failures and contingent interventions in response to trade measures or behaviour by non-EU governments.

- Major strategic autonomy initiatives create additional costs for businesses operating in the EU and restrict trade with non-EU jurisdictions.

- Strategic autonomy aspirations represent a relapse of the EU to the old policy of EU Member States designing and enforcing their own laws without considering the economic and political costs of regulatory fragmentation and economic disintegration from others.

- Measured by initiatives in economic and technology policymaking, the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda is a backward-looking endeavour. It risks becoming a blueprint for economic nationalism globally – a justification for governments outside Europe, especially developing countries, to erect new trade and investment barriers on their own.

- EU policymakers need to uphold open trade principles and multilateral commitments rather than EU-first policies. The EU and its Member States must not become a template for economic nationalism in developing countries.

- EU Member States are advised to ask themselves whether there are better long-term strategies to pursue than those proposed by Brussels – strategies guided by the principles of free trade, non-discrimination, and economic freedom.

Empower individuals and businesses

- EU Member States’ capacity to benefit from technology results from the ability of individuals, firms and governments to deploy global frontier technologies and technology-enabled business models in many different ways.

- A political program recognising capabilities of firms and individuals will have to start with the provision of sound education and human capital.

- It also requires a strong, perhaps unprecedented emphasis of knocking down regulatory barriers and overly complex taxation in Europe’s incomplete Single Market to allow European companies, including start-ups, to scale up and become globally relevant

[1] Bruegel (2018). Are economic and political freedoms interrelated?, by Marek Dabrowski, 10 October 2018. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/are-economic-and-political-freedoms-interrelated.