EU Autonomy, the Brussels Effect, and the Rise of Global Economic Protectionism

Published By: Matthias Bauer Dyuti Pandya

Subjects: European Union WTO and Globalisation

Summary

The Brussels Effect, once emblematic of the EU’s alleged influence in shaping global regulations, has now become a factor contributing to global regulatory fragmentation. The EU must recalibrate its trajectory towards a liberal and rules-based trading order, prioritising widespread regulatory liberalisation to counteract the risks of global protectionism and regulatory spirals. A holistic approach, both internally and globally, is crucial to prevent regulatory and subsidy spirals on a global scale. This recalibration is essential to keep global markets open and enhance the EU’s own economic and technological competitiveness.

In response to the 2008 financial crises, the EU underwent a shift in its approach to global trade, transitioning towards Strategic Autonomy. However, this gradual move away from a liberal global trade order has led to increased regulatory burdens and regulatory fragmentation, impacting businesses within and beyond the EU.

The Brussels Effect, as denoted in this paper, highlights the EU’s signalling effect on other governments in considering and implementing regulations. This effect has contributed to increased trade restrictiveness and regulatory fragmentation globally. The EU’s insistence on “autonomy” and “European values” not only empowers others to follow suit, contributing to the rise in global protectionism, but also contradicts the EU’s historical support for open trade principles and its commitment to a highly competitive social market economy.

A wealth of EU regulatory data reveals a stagnation and, in many cases, a regression in regulatory cooperation within the Single Market. This is evident from rising trade restrictiveness and a tendency towards increased legal fragmentation instead of convergence across the EU. The evolving regulatory acquis of the EU, coupled with insufficient cooperation and stalled trade agreements, poses risks beyond its borders. The EU’s paradigm shift towards autonomy contributes to global regulatory spirals and protectionist measures, particularly evident in services trade. Despite the EU’s historical commitment to harmonisation and liberalisation, many sectors, such as transport and logistics, telecoms, and digital services, have witnessed the imposition of new laws and rules that hinder trade.

With the EU’s share of global GDP expected to decrease to 9% by 2050, there is a critical need for EU governments to enhance its regulatory capabilities and foster innovation. To wield influence in global economic diplomacy, EU policymakers must prioritise policies that unleash the collective ingenuity of individuals and businesses that help to maintain high levels of productivity, competitiveness, and prosperity.

In response to these observations, we put forth some essential policy recommendations:

Return to a Liberal Global Economic Order: The EU should reaffirm its commitment to a liberal global economic order, prioritising economic freedom, government accountability, knowledge, innovation capacities, and prosperity.

Refocus on the Internal Market: The EU should implement a comprehensive internal strategy involving liberalisation, de-bureaucratisation, legal harmonisation, and tax code simplification. EU policymaking should foster regulatory coherence through collaboration between EU governments and the European Commission.

Flexible Approach to Economic Integration: The EU and Member State governments should adopt a more flexible and adaptive approach to economic integration, emphasising mutual recognition to respond effectively to evolving global dynamics while preserving open markets. EU governments should engage in a constructive dialogue to streamline regulations and eliminate barriers hindering the free movement of goods and services within EU borders.

Promote Regulatory Coalitions: EU institutions and Member State governments need to recognise the challenges in achieving consensus among all EU member states. They should promote regulatory coalitions among willing Member States for more agile horizontal and sector-specific regulatory frameworks.

Enhance Global Regulatory Cooperation: The EU should seek more regulatory cooperation globally, emphasising mutual recognition (interoperability) of regulations, and, as a guiding principle, work towards an open and rules-based international trading system.

Advocate for a Strategic Free Trade and Technology Alliance: EU policymakers must acknowledge the adverse consequences of an evolving regulatory silos and champion the international coordination of trade and behind-the-border policies. The EU should actively advocate for the establishment of a strategic free trade and technology alliance among market-oriented democracies, such as the larger group of OECD or G20 countries. The EU and Member State governments should embrace market-led standardisation in international forums to develop global technology standards, enabling smoother cross-border digital trade. To fuel intra-EU and extra-EU digital trade, EU policymakers should take a leading role in harmonising digital and technology standards both within the EU and globally.

1. Introduction

Global protectionism has increased sharply since the global sovereign debt and financial market crises of 2008, and it shows no signs of abating.[1] The number of new regulations set by the EU, OECD and BRICS countries and their restrictiveness has been increasing globally. Trade restrictions, investment barriers and measures that distort competition, first and foremost subsidies, are being created around the world. The EU has championed open markets and a liberal global trade order for decades. But with policies that seek autonomy or sovereignty, and in some instances even isolation, the EU is putting its credibility and global standard setting power at risk.

The EU’s long-standing commitment to an open and liberalised trading system will be jeopardised if the EU stays the course and enacts more restrictive laws that make trade within the EU and between the EU and third countries more difficult. The implementation of protectionist measures, leading to increased trade barriers and regulatory complexities, risks disrupting the smooth flow of goods and services, thereby impeding global economic integration and EU’s participation in global trade and investment.[2] The preference for stringent regulations by EU policymakers over the years has continued to reflect an aversion to risk and to commitment to a social market economy.[3]

The EU’s pursuit of “Strategic Autonomy” may eventually erode the openness it has advocated for, for decades, diminishing market access and appeal, and causing a decline in EU influence in international fora. Policymakers at the EU and Member State levels should thus carefully weigh these consequences and start prioritising measures aimed at safeguarding the EU’s enduring economic success and its future standing in global geopolitics, recognising the intrinsic connection between the two.

The EU’s departure from a longstanding commitment to advancing a liberal world trading system

The EU’s pursuit of “Strategic Autonomy” has ushered in a notable departure from its longstanding commitment to advancing a liberal world trading system and championing trade liberalisation. This strategic recalibration is reflected in an escalating regulatory burden imposed on both domestic (EU-headquartered) and international companies operating in the EU, resulting in a discernible shift towards a more protectionist orientation within the EU. A prominent example of this shift is the relaxation of state aid rules, introducing government funding that creates distortions to competition within and beyond the EU’s own Single Market.[4]

EU policymakers, in their defence of new policies and subsidies, articulate a dual rationale:

- EU policymakers claim that the EU is compelled to synchronise its regulatory landscape with global trends, necessitating the introduction of new regulations and potential trade and investment barriers. This argument is presented with a certain degree of reservation, as EU officials acknowledge the inevitability of aligning with perceived global norms.

- EU policymakers also contend that the EU confronts an array of regulatory and geopolitical challenges that demand proactive measures, particularly in contrast to jurisdictions deemed insufficiently responsive to these challenges.

In essence, policymakers’ perspectives align with the idea that their proactive measures are responses to diverse challenges faced by the EU, especially when contrasted with perceived shortcomings in the approaches of other jurisdictions. The ongoing debate about protectionism, regulatory cooperation, and free trade agreements (FTAs) reflects the complex landscape of global trade, where individual decisions can have ripple effects across economies.

This perspective aligns with an IMF analysis of deglobalisation phases, where the EU’s approach can be viewed as a nuanced response to evolving global dynamics.[5] The first phase, around 2015, marked a backlash against globalisation, and EU policymakers may interpret this as an impetus to address distributional concerns arising from global economic integration.

The second phase, triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, saw calls for resilience (with the IMF authors arguing that international trade enhanced resilience). EU policymakers, in this context, might be responding to specific shocks and challenges revealed by the pandemic, emphasising the need for tailored approaches.

The third phase, initiated by geopolitical pressures such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, reflects another shift in mindset towards a zero-sum game in international welfare. EU policymakers now often justify new measures and initiatives by citing similar geopolitical and regulatory challenges, reinforcing the idea that their actions are necessitated by evolving global circumstances. This complex interplay between global events and policy responses underscores the intricate landscape of global trade dynamics.

These three phases globally influenced policy decisions, but within the EU, policymakers’ proactive stance, especially in areas like digital trade, technology competition, and industrial subsidies, suggests a distinct political drive to leverage global trends for measures that, rather than addressing global geopolitical challenges, are frequently justified by the necessity for swift and decisive regulatory responses.

By adopting an approach that intensifies regulatory requirements, the EU risks creating barriers that hinder the free cross-border flow of goods, services, and capital, thereby contradicting the fundamental principles of an open and liberalised trading system. To name just a few:

- Prescriptive policies, which dictate specific rules and standards, and proscriptive policies, which prohibit certain activities, can lead to increased complexity and compliance costs for businesses. This additional regulatory burden is likely to disproportionally affect smaller enterprises, potentially limiting their ability to engage in cross-border trade. As a consequence, the EU may find it challenging to foster an environment conducive to the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – entities crucial for economic dynamism and job creation.

- An escalation in regulatory requirements may discourage foreign investors from entering the EU market or prompt existing investors to reassess their commitments. Investors are typically attracted to regions with clear, stable, and business-friendly regulatory frameworks. If the EU’s regulatory landscape becomes excessively intricate or subject to frequent changes, it may erode the attractiveness of the European market for both domestic and international investors.

- Increased regulatory burdens typically result from a lack of harmonisation and divergent industry regulations across Member States. This fragmentation has led to countless internal trade barriers within the EU, hindering the seamless movement of goods and services. The envisioned Strategic Autonomy pursued by the EU may unintentionally obstruct the very openness and integration it has championed for decades even more. As we will show below, despite all the political talk, there has been no significant deepening of the EU’s internal market over (at least) the past 10 years.[6]

The looming risk of an EU-fuelled regulatory spiral becomes apparent

The EU’s shifting regulatory approach has repercussions beyond its borders, creating a domino effect as governments in developing and emerging market economies are influenced to adopt similar protectionist measures.[7] This trend, inspired by EU actions, raises concerns about a potential global regulatory spiral, as other nations may emulate these measures to address perceived challenges, disregarding the foundational principles of the liberal world trading system traditionally championed by the EU.

In addition to its regulatory shifts, the EU’s anaemic attempts to improve regulatory cooperation with third countries further underscores the challenges in fostering an open and collaborative international trade environment.[8] The lack of effective coordination and cooperation with external partners impedes the development of cohesive regulatory frameworks that could facilitate smoother trade interactions. This deficiency in regulatory alignment will ultimately contribute to an environment where divergent standards and requirements hinder global flows of goods and services.

Furthermore, despite the EU’s historical role as a proponent of FTAs, recent trends indicate a stagnation in progress. The EU’s endeavours to negotiate and finalise significant FTAs seem to be encountering impediments, resulting in a lack of substantial breakthroughs. Ursula von der Leyen’s trade legacy appears to be diminishing as her ambitious goals face setbacks, particularly with trade deals with South American and Australian partners. Despite efforts to diversify economic relationships, challenges and failures in key negotiations, such as with Mercosur and Australia, raise questions about the effectiveness of the EU’s trade strategy under her leadership.[9] This inertia in advancing FTAs diminishes the EU’s ability to leverage its economic influence and engage meaningfully in shaping the global trade landscape.

As the EU continues on its path towards achieving Strategic Autonomy, it becomes crucial to conduct a thorough assessment of the broader international consequences. The evolving narratives around the EU’s approaches to achieving autonomy in production and trade necessitates a nuanced examination of its impact on regulatory cooperation and, more generally, of the challenges it poses to maintaining a liberal and open global trading system.

In this context, the Brussels Effect, once synonymous with the EU’s substantial influence in shaping global regulations, has generated controversy regarding its actual significance. While EU regulations often prompt other nations to adopt similar rules, this regulatory fragmentation can impose substantial costs on businesses, creating barriers to trade and hindering international integration. Examples like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and EU competition policy showcase the Brussels Effect’s global impact, albeit with variations and country-specific adjustments, contributing to a complex global patchwork of rules and regulatory fragmentation.

The Brussels Effect was once emblematic of the EU’s influence in shaping global regulations. The term signified the potential impact of the EU in shaping global regulations. This influence, it was said, arose from the EU’s large market, extraterritorial reach, and impacts on global value chains, compelling governments and companies worldwide to adopt EU standards.

Whether and to what extent there is a “significant” Brussels Effect – in the sense that governments outside the EU adopt EU policies – is controversially discussed.[10] But it is evident that new EU regulations often prompt other countries to contemplate and adopt similar rules, often with specific adjustments to suit their national political contexts.[11] The Brussels Effect is a result of the EU’s economic size, regulatory capacities, and the willingness to regulate in line with the precautionary principle, making its regulations have a more widespread impact on the global scale compared to other regions like Tokyo or Beijing. However, the fragmentation of laws does impose costs on businesses, and it does create barriers to trade:

- The complexity and inconsistency of regulations across different regions makes it challenging for companies to navigate and comply efficiently.

- Legal fragmentation introduces complexity, compliance costs, and uncertainties for businesses operating across borders, hindering the smooth flow of goods and services.

- Differing regulations among countries may create barriers that impede the efficiency and integration of global markets.

- On aggregate, regulatory fragmentation can have a deterrent effect on international trade and investment.

While some analysts still perceive the Brussels Effect as conducive to trade based on high standards,[12] it is evident that an increased number of regulations, coupled with de facto fragmentation, poses a barrier to international trade and investment.

The EU’s GDPR[13] is one of the most notable examples in the debate about the Brussels Effect. The EU’s stringent data privacy regulations have indeed had a global impact, with many governments using GDPR as a starting point for their own privacy policies, and companies worldwide partly adjusting their data protection policies to align with GDPR standards.[14] Nevertheless, GDPR has not been universally adopted without country-specific modifications. Variations and country-specific adjustments are prevalent, leading to a complicated global patchwork of data protection rules.

Another example is the EU competition policy. The EU’s competition regulations and enforcement measures, led by the European Commission, do impact global competition rules. This is evident in the formulation of rules and in the control of mergers. Many non-EU countries, e.g., the UK[15] and India[16], have taken inspiration from EU restrictions targeting common commercial practices of large technology platforms.[17] Although the rules differ greatly in detail, countries outside the EU typically rely on similar – though vague – principles, such as notions of “fairness” and “contestability”, while maintaining their own distinct competition policies influenced by domestic economic and political considerations.[18]

In the pursuit of Strategic Autonomy, the EU’s regulatory initiatives, especially in digital and competition policymaking, impede cross-border trade and investments.[19] This trend, coupled with the EU’s sluggish progress in regulatory cooperation and free trade agreements, raises concerns about how EU policymaking is impacting the global trade and investment landscape. The EU’s evolving regulatory approach serves as a signal to governments in developing economies, inspiring the potential adoption of protectionist measures, leading to a domino effect that threatens the liberal world trading system.

The inadequacy of regulatory cooperation with the US and third countries further compounds these challenges. Concerns have recently been raised by the US government in the context of the WTO and other international fora. In her opening statements on the 15th Trade Policy Review of the European Union, Ambassador María L. Pagán, U.S. Deputy United States Trade Representative, raised concerns about persistent barriers faced by specific US goods and services in the EU market. These concerns ranged from procedural issues related to regulatory notifications and the EU’s hazard-based approach to regulations (highlighting the REACH regulation) to challenges in market access for U.S. agricultural products and wine exports. Additionally, she addressed issues such as the EU’s proposed cybersecurity certification scheme (EUCS), its exclusionary approach to standards-related measures, and challenges in EU customs administration. Ambassador Pagán expressed a commitment to continued collaboration but urged addressing these concerns for enhanced transatlantic trade opportunities, emphasising the need for cooperation and consultation at the WTO to adapt trade policies to global challenges.

The evolving narrative around the EU’s approach to policy initiatives, implementation, and enforcement necessitates a nuanced examination of its impact on international trade cooperation and the broader implications for maintaining a liberal and open global trading system. Policymakers should consider these consequences to preserve the EU’s long-term economic success, recognising the intricate link between regulatory choices and global standing.

[1] See, e.g., Wiberg, M. and Wallen, F. (2021). Growing Protectionism After The Financial Crisis: What is the Evidence? Institute of Economic Affairs Current Controversies No. 60. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3853657. Also see Evenett, S. (2019). Protectionism, state discrimination, and international business since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis.

[2] See, e.g., Kiel Institute (2021). Pursuit of economic autonomy can be costly for EU countries. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/news/pursuit-of-economic-autonomy-can-be-costly-for-eu-countries/. Also see Rabobank Research (2023). Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy requires dealing with structural weaknesses. Available at https://www.rabobank.com/knowledge/d011405319-europes-quest-for-strategic-autonomy-requires-dealing-with-structural-weaknesses.

[3] The EU’s commitment to social market economy highlighted as a common objective for Europe under (Article 1(4) of the new Lisbon Treaty) [“[The Union] shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, . . . and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment.”] see: Bradford, A. (2012). The Brussels Effect. Nw. UL Rev., 107, 1.

[4] Chee, Y F. (2022). EU to consult on easier state aid rules to counter U.S. subsidy law. Reuters. Available at https://www.reuters.com/business/eu-consult-easier-state-aid-rules-counter-us-subsidy-law-sources-2022-12-13/.

[5] IMF (2023). Growing Threat to Global Trade. Protectionism could make the world less resilient, more unequal, and more conflict prone. Article by Goldberg, P. and Reed, T. Available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/06/growing-threats-to-global-trade-goldberg-reed.

[6] For a discussion, see, e.g., ECIPE (2022). European strategic autonomy – What role for Europe’s fragmented single market? Available at https://ecipe.org/blog/european-strategic-autonomy-single-market/.

[7] Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels Effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press, USA.

[8] Golberg, E. (2019). Regulatory cooperation – a reality check. Available at https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/mrcbg/img/115_final.pdf.

[9] Gijs, C. (2023). Ursula von der Leyen’s vanishing trade legacy. Politico. Available at https://www.politico.eu/article/ursula-von-der-leyens-vanishing-trade-legacy/

[10] The Justice Chief of the EU, Didier Reynders, is encouraging the United States to engage in discussions about more stringent regulation in the tech sector, emphasising the importance of enforcement. Additionally, he intends to advocate for tech companies to voluntarily adhere to the guidelines outlined in the yet-to-be-passed AI Act. These initiatives suggest a domino effect initiated by the EU, aiming to establish an international standard for AI; see: Dave, P. (2023, July 16). The EU Urges the US to Join the Fight to Regulate AI. Available at https://www.wired.com/story/the-eu-urges-the-us-to-join-the-fight-to-regulate-ai/. It is also considered that tech companies may use the EU standard as the global standard in the AI development. Because there are no AI regulations as a benchmark, the EU’s AI regulation will very likely serve as a template for other jurisdictions.

[11] McDougell, M. (2022) EU deal set to trigger ‘domino effect’ for global minimum tax deal. Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/d466849c-512e-4b66-a8ea-38e3b39ade47. Also see: O’Brien and Ibraimova, A. (2022) The fourth anniversary of the GDPR: How the GDPR has had a domino effect. ReedSmith. Available at: https://www.technologylawdispatch.com/2022/05/privacy-data-protection/the-fourth-anniversary-of-the-gdpr-how-the-gdpr-has-had-a-domino-effect/.

[12] See, e.g., Centre for European Reform (2023). In tech, the death of the Brussels effect is greatly exaggerated. Available at https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/ZM_brux_effect_8.12.23.pdf.

[13] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (OJ L 119, 4.5.2016, p. 1). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05-04.

[14] Some examples that followed the similar routes of GDPR suit or have expanded their existing rules on the suit: North America: The California Consumer Privacy Act; Asia: Japan- Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) (2020), Thailand – Personal Data Protection Act (Yet to come in force), Africa: Kenya – Data Protection Act (2019), South Africa – Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act (2020); South America – Brazil – General Data Protection Law LGPD (2020). Also see Greenleaf, G. (2012). The influence of European data privacy standards outside Europe: implications for globalisation of Convention. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1960299.

[15] See, e.g., Lexology (2023). UK: Introducing Regulation of Digital Platforms And New Competition and Consumer Protection Reforms. Available at https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=2ab6fc77-48ed-43af-923f-d7587cf5cb1d.

[16] See, e.g., Singh, M. (2023). The Recipe for India’s Gatekeeper Regulation. Available at https://botpopuli.net/the-recipe-for-indias-gatekeeper-regulation/.

[17] A recent discussion of political rationales and economic impacts is provided by ECPE (2023). Merger Policy, Competition and Innovation Leadership: Implications for the UK’s Investment Attractiveness. Available at

[18] Likewise, as part of its ongoing five-year Digital Platform Services Inquiry, Australia is contemplating the incorporation of new legal instruments within the realm of competition. It is likely that the EU policies (DSA and DMA) will influence the course of legislation in the US; see: Burwell, F. (2021, March 30) Regulating Platforms the EU Way? The DSA and DMA in Transatlantic Context. Wilson Center. Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/regulating-platforms-eu-way-dsa-and-dma-transatlantic-context. For South Africa, see Competition Act 89 of 1998, Preamble (S. Afr.).

[19] See, e.g., ECIPE (2022). The costs of the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda – Why member states should stop ignoring them. Available at https://ecipe.org/blog/eu-strategic-autonomy-agenda/.

2. Lacking Cooperation in Regulating EU and Global Services Trade

The OECD’s latest report on the restrictiveness of services trade for 2022 reveals an increase in regulatory changes compared to the previous year.[1] This surge in regulatory changes reflects nations’ concerted efforts to address diverse global economic challenges and demonstrates substantial liberalisation endeavours underpinned by governmental actions to enhance domestic business operations and improve regulatory transparency. For the EU, data demonstrates that there has been a notable rise in services trade restrictiveness, signalling a degree of complacency and emphasising the urgency of reviving regulatory harmonisation both within the EU and globally.

Services trade plays a pivotal role in modern economies, contributing significantly to economic growth and development. Unlike traditional goods trade, services encompass a wide array of activities, including finance, telecommunications, education, healthcare, and professional services. The importance of services trade lies in its capacity to enhance efficiency, foster innovation, and generate employment opportunities. As economies undergo structural transformations, a vibrant services sector becomes increasingly integral, supporting the diversification of economic activities beyond manufacturing and agriculture.

The liberalisation of services trade can have profound effects on economic development and structural renewal. By reducing barriers to entry and promoting competition, liberalisation fosters efficiency gains and innovation within the services sector. This, in turn, contributes to overall productivity improvements in the economy. Additionally, an open and liberalised services trade regime attracts Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and encourages the inflow of new technologies and management practices. The dynamism of the services sector also facilitates the development of human capital, as it often relies on skilled labour. Consequently, the liberalisation of services trade becomes a catalyst for structural economic renewal, driving a shift towards higher value-added activities, fostering entrepreneurship, and enhancing a nation’s global competitiveness in the rapidly evolving landscape of the knowledge-based economy.

Despite some positive changes, the OECD notes the introduction of multiple new services trade barriers in 2022, including limitations on the ability of foreign companies to provide services locally, constraints on the movement of service providers, and heightened control over foreign investments. Notably, the average level of restrictions in non-OECD countries across 22 sectors exceeded that in OECD countries, emphasising ongoing regulatory fragmentation and disparate conditions for services market access. The average degree of restrictions within the 22 sectors studied for non-OECD countries stood at 1.5 times greater than that observed in OECD countries. This discrepancy highlights the persistent trend of regulatory fragmentation, signifying disparate conditions for market access to services across various regions.

More fragmentation is a clear sign of less cooperation or, in other words, regulatory nationalism. It should be noted that specific national regulations in services industries are not new. Despite numerous efforts by governments to liberalise trade in services or to create greater regulatory convergence, if not harmonisation, EU and OECD countries as well as the economies of emerging and developing countries have not managed to seek and agree on regulations that make trading and investing in the services sectors easier.

Political lip service and rhetoric in support of more cooperation cannot hide this reality. Looking at longer-term data on barriers to trade in services, we can see that there have been very few areas of improvement in liberalisation and reduction in fragmentation since data collection began in 2014. This also applies to the EU and the relatively economically developed OECD countries. In most service sectors, new laws and rules have restricted trade and increased regulatory arbitrage.

Given the increasing regulatory burdens and the potential for divergent standards within the EU, the imperative for EU governments is clear: they must urgently request the European Commission to inject new momentum into efforts aimed at reviving regulatory harmonisation both within the single market and on a global scale. This becomes an even more pressing matter considering that data from the past decade indicates a concerning trend of stagnation and, in many cases, deterioration in regulatory cooperation within the Single Market. This is exemplified by the evident increase in trade restrictiveness and a surge in regulatory heterogeneity rather than regulatory convergence, as outlined in the next Section.

Development of services trade restrictiveness

To elucidate these trends, we conducted a thorough analysis of extensive regulatory data using the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) and OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (DSTRI). Our focus was on unravelling the dynamics of “regulatory trade restrictiveness” and the trajectory of “regulatory fragmentation” (also referred to as regulatory heterogeneity) between the period 2014-2018 and the period 2018-2022.[2] To do this, we looked at the differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods and counted in how many cases “regulatory restrictiveness” and “regulatory heterogeneity” increased or decreased.

It is important to recognise that constraints on businesses do not solely arise from stringent regulations; instead, they often stem from divergent regulations designed to achieve similar objectives. These variations in details can pose significant challenges for companies aiming to navigate and comply with diverse laws across different markets. The potentially extensive reach of EU regulatory influence can curtail the benefits associated with regulatory experimentation and hedging. Should an EU regulation prove ineffective or inefficient, it has the potential to permeate global business practices and be replicated in legislative frameworks across the world.

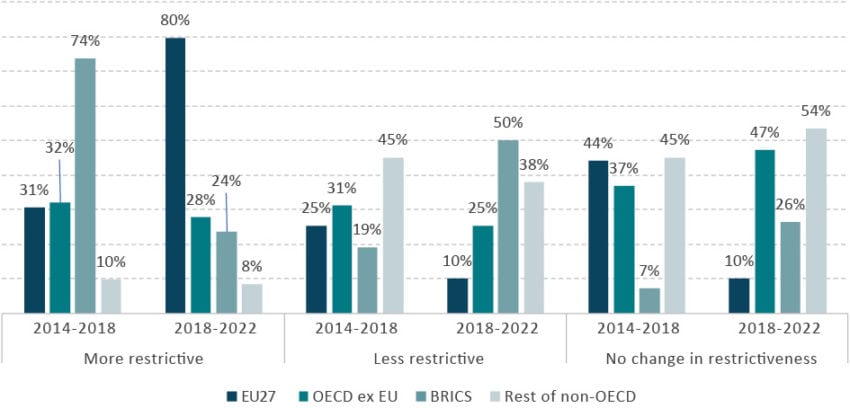

As concerns the trade restrictiveness of services regulations, OECD STRI data reveal notable changes in trade policies across regions and time frames. Within the EU22[3], there is a striking increase in services trade restrictiveness from 31% in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 80% in the period 2018-2022. This substantial surge in the “More restrictive” category signals a significant tightening of regulations affecting services trade among EU Member States. The sharp decline in the “Less restrictive” category, from 25% in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 10% between 2018-2022, indicates a reduction in measures that facilitate freer services trade. Another concerning aspect is the prevalence of “No change in restrictiveness” at 44% and 10% for the two respective periods. Overall, this suggests a certain degree of complacency within the EU, with a reluctance to revise or enhance existing services regulations and trade policies, potentially hindering the adaptability of the services market to emerging economic challenges.

Comparing regions, the OECD countries excluding the EU witnessed a decrease in overall services trade restrictiveness from 32% in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 28% over the period 2018-2022, indicating a trend toward less restrictive measures. However, another noteworthy observation is the considerable rise in the “No change in restrictiveness” category from 37% to 47%. This also suggests a sense of complacency within the broader OECD region, as a significant proportion of countries maintained their existing trade policies and services regulations. This inertia in reassessing and updating trade regulations may hinder the ability of these countries to respond dynamically to changing economic and technological landscapes, potentially impeding innovation, structural economic change, and economic growth.

Figure 1: Development of services trade restrictiveness, 2014-2018 and 2018-2022

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Development of digital services trade restrictiveness

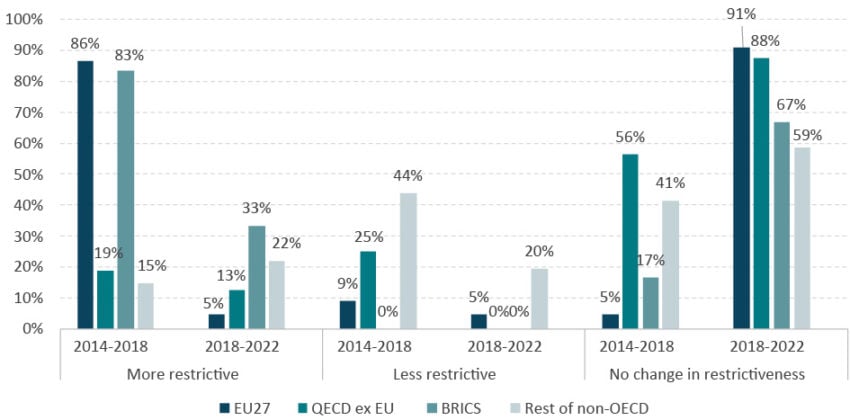

The OECD DSTRI data also underscores the changing landscape of digital services and trade policies across regions and time frames. In the EU22, there is a noteworthy decrease in digital services trade restrictiveness from 86% in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 5% between 2018-2022. This improvement indicates a slight shift toward less restrictive measures, reflecting a more open environment for digital services trade within the EU. However, a concerning aspect is the prevalence of “No change in restrictiveness” at 5% of the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 and 91% for the period 2018-2022. This indicates that a substantial portion of the EU22 maintained the existing level of restrictiveness in digital services trade, signalling a certain degree of complacency. In a rapidly evolving digital landscape, where innovation and technological advancements drive economic growth, maintaining trade-restrictive status quo policies may hinder the EU’s ability to harness the full potential of the digital economy.

Comparing regions, the OECD countries excluding the EU witnessed an improvement in digital services trade restrictiveness, with a decrease from 19% in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 13% over the period 2018-2022. Notably, the “No change in restrictiveness” category increased significantly from 56% to 88%, suggesting a lack of proactive policy adjustments in this digital domain. This prevalent inertia indicates reluctance among these countries in opening up digital services trade. As digital technologies continue to reshape global business landscapes, complacency in digital policies may impede countries from fully capitalising on the benefits of digitalisation, hindering economic growth and global competitiveness.

Figure 2: Development of digital services trade restrictiveness, 2014-2018 and 2018-2022

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

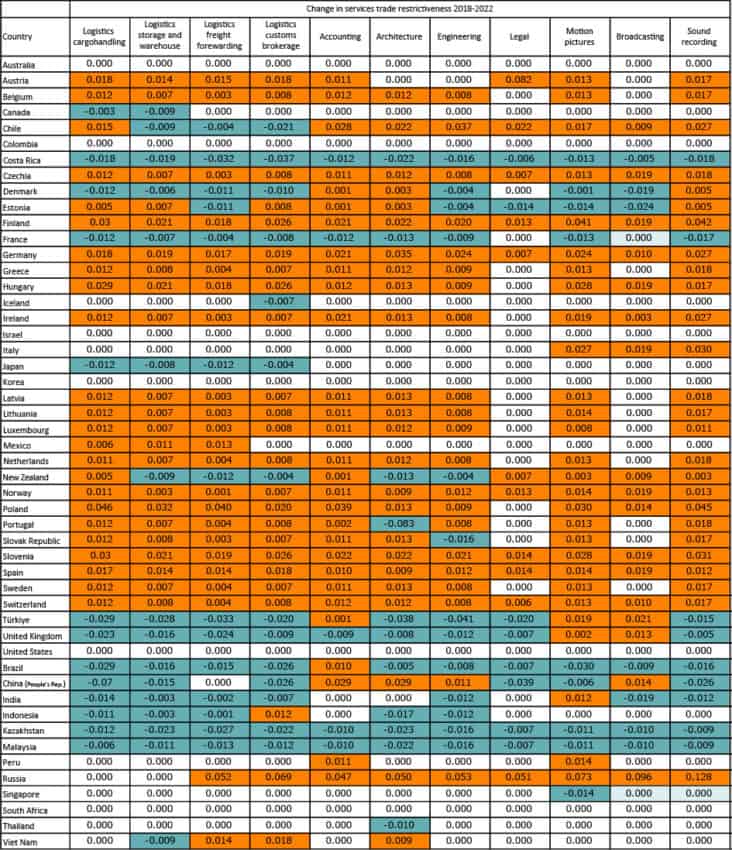

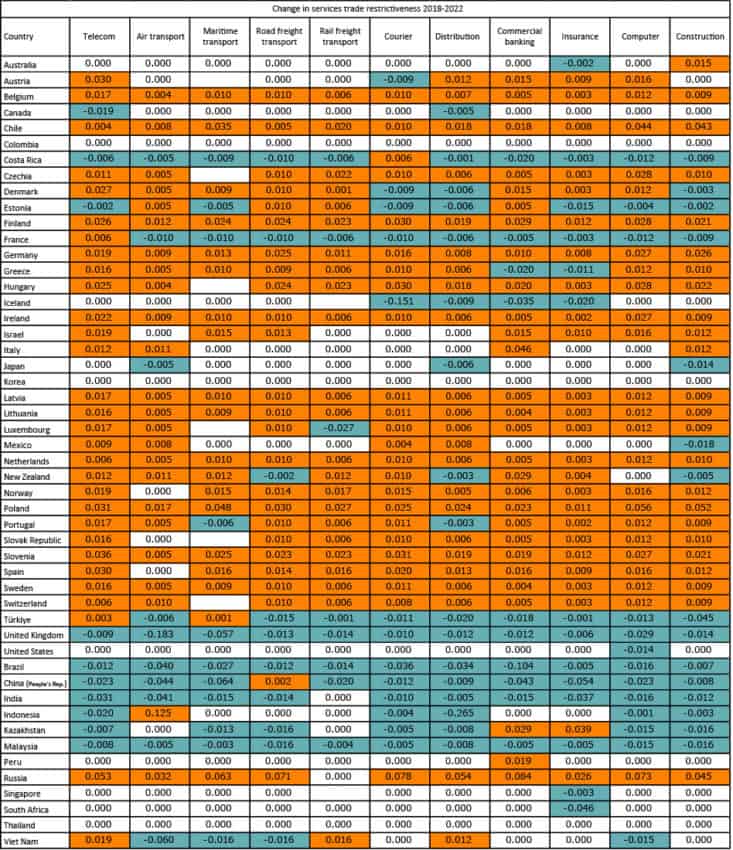

Looking at country-specific trends, a highly diverse picture emerges. The data suggests that EU countries’ trade restrictiveness has not followed a consistent trends. While some EU countries have become less restrictive, many EU governments have increased the level of trade restrictiveness, whereas many others have not changed sector-specific regulations between the periods 2014-2018 and 2018-2022 (see Table 1 and Table 2). However, the data clearly shows that EU countries changed their regulations in such a way, especially between 2018 and 2022, that they made cross-border trade more difficult. Against this background, calls for more liberalisation and harmonisation (see below) from the EU or representatives of the Member States appear unrealistic and implausible.

Patterns in global trade restrictiveness also vary among countries and regions. Some countries outside the EU, like Canada and New Zealand, experienced both increased and decreased restrictiveness. In Latin America, there’s evidence of increased restrictiveness. Overall, global trends in the level of services trade restrictiveness do not show a clear trend of becoming uniformly less or more restrictive. However, the data clearly demonstrates a lack of uniform willingness among governments to align sector-specific regulations. While a limited number of countries, including EU Member States, have harmonised regulations or eased restrictions, others have taken divergent paths by implementing more stringent measures. The variations suggest that factors influencing regulatory alignment are complex and critically depend on specific economic and political contexts.

Table 1: Change in services trade restrictiveness 2018-2022

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Table 2: Change in services trade restrictiveness 2018-2022 (continued) Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Development of regulatory heterogeneity

OECD data on regulatory heterogeneity in the overall DSTRI highlights significant shifts in regulatory approaches across different regions and time periods. Analyzing regulatory heterogeneity between EU22 countries, there is a reduction in the overall level of regulatory heterogeneity from 43.7% of the total number of country-by-country observations between 2014 and 2018 to 9.5% between 2018 and 2022, indicating a move toward a more harmonised regulatory framework for digital services trade within the EU. However, the striking increase in the “No change” category from 45.9% of the total number of country-by-country observations in the period 2014-2018 to 81.0% for the period 2018-2022 suggests reluctance in aligning regulations across the Single Market. It raises concerns about whether the EU is proactively adjusting its regulatory environment to foster innovation and competitiveness in the digital sector in the EU’s internal market.

Comparatively, looking at the group of OECD countries, excluding the EU, the decline in regulatory heterogeneity from 33.3% of the total number of country-by-country observations between 2014 and 2018 to 24.2% for the period 2018-2022 is promising. However, the substantial rise in the “No change” category from 30.0% to 75.8% also signals a broader trend of stagnation in regulatory adjustments within the OECD. This could imply a certain level of complacency or resistance to evolving regulatory frameworks to address the changing dynamics of digital services. In a rapidly advancing technological landscape, a lack of proactive regulatory changes may hinder the ability of these countries to capitalise on the full potential of digital trade, potentially limiting innovation and economic growth.

The data on regulatory heterogeneity in specific service sectors, including Computer Services, Telecom Services, Distribution Services, and Commercial Banking Services, reveals consistent patterns of concern, particularly cantered around the “No change” category. In Computer Services within the EU, despite a marginal reduction in heterogeneity, the significant increase in the “No change” category suggests a potential complacency or reluctance to adapt regulations dynamically. This static approach might impede the EU’s ability to respond effectively to technological advancements, limiting innovation and competitiveness in the Computer Services sector. The data underscores the need for a more agile and proactive regulatory environment to keep pace with the evolving nature of technology-driven industries.

A parallel trend is evident in Telecom Services within the EU, where a modest reduction in heterogeneity is coupled with a notable rise in the “No change” category. This indicates a potential complacency in updating regulations, posing a risk of falling behind in a rapidly changing telecom sector. The data emphasises the critical importance of continuous regulatory adjustments to foster innovation and competition in Telecom Services. In Distribution Services, the substantial increase in the “No change” category, along with rising overall heterogeneity, points to a potential complacency or resistance in adapting regulatory frameworks. This lack of effort may hinder the growth and efficiency of distribution services, necessitating a revisit and update of regulations to ensure competitiveness in line with emerging market trends.

Similarly, the data for Commercial Banking Services in the EU highlights a notable increase in the “No change” category, signalling a potential complacency or inertia in adjusting regulatory measures. The overall rise in heterogeneity suggests that while there are variations in regulations, a reluctance to make substantial changes may impact the competitiveness and innovation potential of commercial banking services. Given the dynamic nature of financial services and the increasing role of technology, a more proactive and adaptive regulatory approach is imperative. Policymakers should consider the implications of maintaining the status quo and assess the need for regulatory adjustments to ensure the resilience and competitiveness of the commercial banking sector.

Table 3: Development of regulatory heterogeneity in services trade restrictiveness, 2014-2018 and 2018-2022 Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More heterogeneity/fragmentation”, values < 0 equals “Less heterogeneity/fragmentation”.

Source: own calculations based on OECD data. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More heterogeneity/fragmentation”, values < 0 equals “Less heterogeneity/fragmentation”.

[1] OECD (2023). OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy trends up to 2023. February 2023. Available at https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/stri_policy_trends_up_to_2023_final. The 2022 OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) serves as a comprehensive evaluation of services regimes across countries. The primary objectives of the STRI encompass guiding policymakers and regulators, providing transparent information to exporters, and offering a foundational dataset for academic research on the drivers and impediments to services trade.

[2] The OECD data goes back to 2014.

[3] The OECD does not report data for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Malta, and Romania, which are EU27 Member States.

3. The Global Rise in Subsidies and Trade-distorting Measures

In its 2021 report, Global Trade Alert (GTA) painted an alarming picture, reporting that nearly half of the recorded government interventions in trade and investment from 2008 to 2021 were subsidies.[1] The majority of recorded subsidy programs are implemented by China, the EU, and the US, collectively constituting over half of the global subsidy measures.[2]

The GTA report emphasises that the world trading system has undergone significant disruption due to the numerous subsidies awarded by China, the EU, and the USA. For example, the report highlights that major manufacturing sectors experienced a substantial number of subsidies, with over 931 awards each, primarily favouring local commercial interests. The distribution of subsidies affecting domestic and foreign markets varies across sectors, highlighting nuances in their impact on domestic competition. To gauge the global influence of these subsidies, GTA estimates the share of global sectoral trade affected by revealing a range from 46% to over 83% across the top 15 manufacturing sectors. GTA also examined the spillover effects of subsidies, differentiating between negative impacts on trading partners and positive outcomes for buyers. Emphasis is placed on the negative spillovers from subsidies to import-competing firms, exemplified for instance by Germany facing 56,078 hits to its export potential in 2019.

Export incentives, in particular, led to more substantial negative spillovers, affecting 33 economies with over 10,000 instances, notably impacting exports from major economies. The GTA analysis acknowledges the potential benefits of export incentives for buyers while underscoring the multitude of negative spillovers. Although positive spillovers from export incentives are fewer, the discussion notes that buyers in 38 jurisdictions potentially benefited over 10,000 times. This underscores the far-reaching impact of subsidies on international trade routes and foreign markets.

Subsidies always develop their own dynamics, and this is usually accompanied by subsidy spirals that are difficult to break. As measured by GTA, EU, US and Chinese subsidies have affected the conditions of competition of 37.6% of world trade in goods, suggesting that countries continue to engage in “copycat behaviour”, i.e., one governments subsidy decision induces other trading partners to implement their own subsidies and erect import barriers in lines of businesses.[3] Examples include aircrafts, the automobile industry, batteries, and solar panels.

The potential impact of subsidies extends beyond economic inefficiencies, influencing political tensions that may escalate into reduced cooperation and heightened confrontation, particularly in international forums such as the WTO. Anti-dumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) investigations can be indicators of perceived unfair trade practices, including subsidies.

The surge in both anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations over the past decade is often portrayed as an indication of a growing global commitment to addressing economic imbalances and ensuring fair trade practices. The observation of significant disruptions in global trade due to subsidies from major players like China, the EU, and the US raises a pertinent question about the consistency and credibility of their actions within the WTO. In light of this background, there is a valid question about the potential inconsistency or even perceived hypocrisy when these governments take action against each other within the WTO to prevent subsidies.

On one hand, these countries actively engage in subsidising their domestic industries, raising questions about their commitment to fair trade practices. On the other hand, their participation in WTO actions against each other suggests a willingness to use international mechanisms to address perceived unfair practices. This apparent contradiction underscores the complexities and challenges within the global trading system, where countries may pursue policies that protect their own interests domestically while simultaneously advocating for fair trade principles on the international stage.

Let’s take a look at the data. The primary difference between anti-dumping investigations and countervailing duty investigations lies in the nature of the alleged unfair trade practices they address, and can be broken down by how each type of investigation is related to unfair subsidisation:

- Anti-dumping investigations: These investigations are initiated when there is a suspicion that foreign companies are selling their goods in an importing country at prices lower than their fair market value. While this can be a result of various factors, including differences in production costs, it may also indicate that the foreign government is subsidising the exporting industry, allowing them to offer products at artificially low prices. Anti-dumping measures, such as tariffs, are implemented to counteract the effects of this potential unfair subsidisation.

- Countervailing duty investigations: These investigations specifically target unfair subsidies provided by foreign governments to their domestic industries. If a country believes that another country is providing subsidies that harm fair competition, it may initiate a countervailing duty investigation. The imposition of countervailing duties aims to neutralise the impact of these subsidies and ensure a level playing field for domestic industries.

In both cases, these investigations are mechanisms for countries to address what they perceive to be distortions in trade caused by unfair subsidisation. The goal is to protect domestic industries from the negative effects of such practices and to promote fair competition in the global marketplace.

Over the past decade, there has been a noticeable uptick in both anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations. This surge can be attributed to various factors, including the deepening complexities of international trade, heightened global competition, and an increased emphasis on the enforcement of trade regulations. The rise in these investigations reflects an increasing global commitment to addressing economic imbalances and ensuring fair trade practices, with nations actively working to protect their industries.

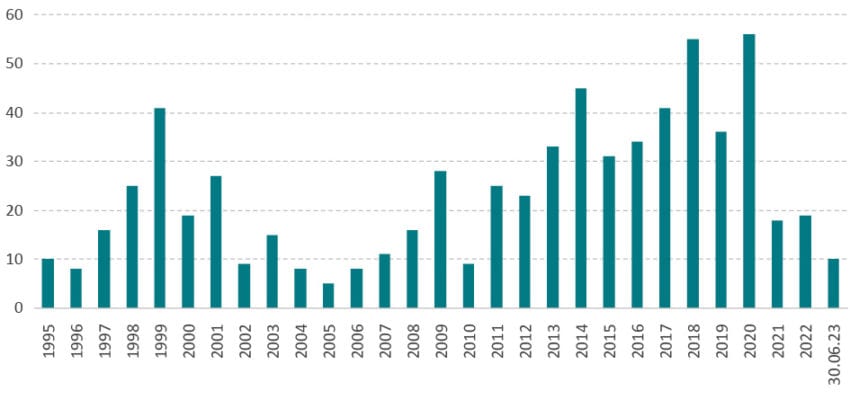

As reported by the WTO’s Trade Remedy Database, the number of countervailing duty investigations initiated by reporting members has experienced fluctuations over the past decades. There is a noticeable upward trend from 1995 to 2000, followed by a period of relative stability until around 2014. Subsequently, there is a discernible increase in the number of initiations, reaching peaks in 2018 and 2020. However, the data also indicates a decline in 2021, followed by a slight increase in 2022 and a decrease again in the reported period ending June 30, 2023. Overall, while there are periods of fluctuation, there is a general upward trend in countervailing duty investigations initiated by reporting members, particularly in the more recent years.

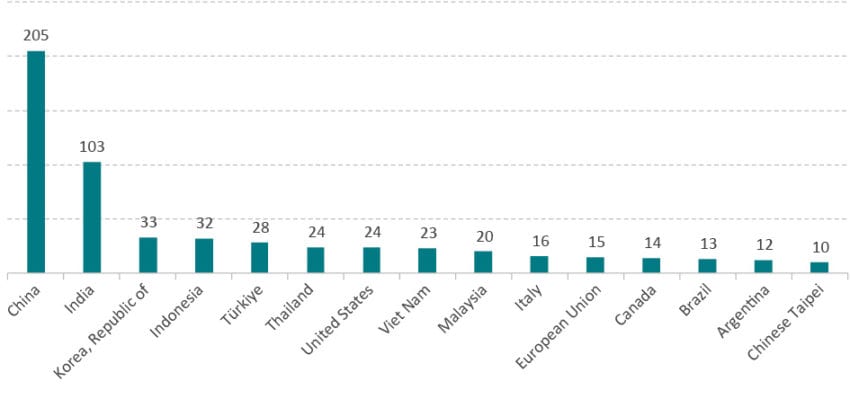

The data also reveals that China faced the highest number of countervailing duty investigations initiations at 205, indicating a significant level of engagement in addressing trade-distorting practices. India follows with 103 initiations, demonstrating substantial number of countervailing duty investigations. Notably, East Asian and South East Asian countries such as South Korea, and Indonesia, along with other nations like Turkey, the US as well as the EU, also show notable investigation numbers, highlighting the global scope of countervailing measures in addressing unfair trade practices. The distribution of initiations underscores the diverse international landscape of trade disputes and the collective effort to enforce fair trade practices.

Figure 3: Total initiations of countervailing duty investigations by reporting members, 1995-2023 Source: WTO trade remedies database.

Source: WTO trade remedies database.

Figure 4: Number of countervailing duty investigation initiations, top 15 target countries, 1995-2023 Source: WTO trade remedies database.

Source: WTO trade remedies database.

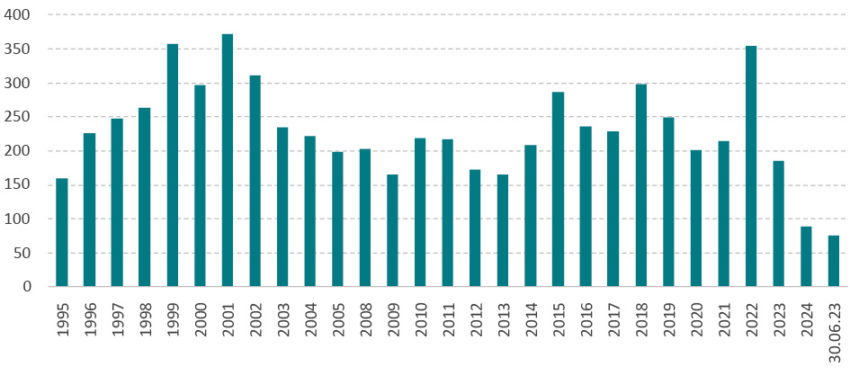

In contrast to countervailing duty investigations, anti-dumping investigations exhibit a more erratic trend with both increases and decreases over the years, and the recent decline in cases suggests a departure from the general upward trajectory observed in the earlier years. The number of anti-dumping investigations shows an overall increasing pattern from 1995 to the early 2000s, with a peak in 1999 at 357 cases. Following this, there is a period of fluctuation with some peaks and troughs, but the numbers remain relatively high. Notably, there is a considerable spike in 2020 with 355 cases, and then a significant drop in 2022 and the reported period ending June 30, 2023, with 89 and 76 cases, respectively.

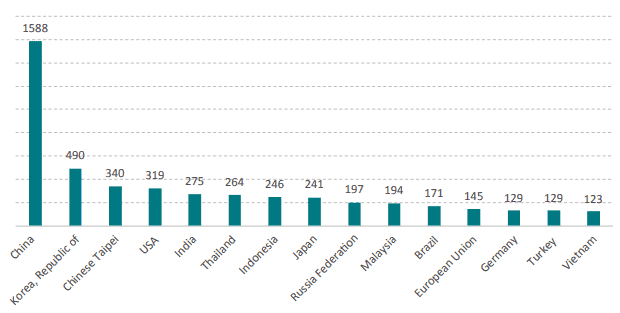

The data on anti-dumping investigations from 1995 to 2023 reveals that China has the highest number of investigation initiations with 1,588 cases, underscoring its significant involvement in addressing alleged unfair trade practices. Republic of Korea and Chinese Taipei follow with 490 and 340 initiations, respectively, indicating substantial engagement in anti-dumping measures. The United States and India also feature prominently with 319 and 275 initiations, reflecting their active roles in investigating and addressing dumping concerns. The data highlights the global nature of anti-dumping actions, with various countries participating in efforts to ensure fair trade and prevent economic harm from alleged unfair trade practices.

Figure 5: Total initiations of anti-dumping investigations by reporting members, 1995-2023 Source: WTO trade remedies database.

Source: WTO trade remedies database.

Figure 6: Number of anti-dumping investigation initiations, top 15 target countries, 1995-2023

Source: WTO trade remedies database.

Source: WTO trade remedies database.

The rise in anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations can be viewed as an indicator of challenges within the multilateral rules-based trading order. While not necessarily signalling a direct erosion, it does raise questions about the effectiveness and sustainability of the existing framework of WTO rules, multilateral agreements, and bilateral FTAs.

The rise in anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations is based on various factors. It reflects a move by governments toward bilateralism and protectionism, as countries under economic pressures resort to unilateral measures instead of seeking multilateral solutions, potentially undermining collective cooperation. This trend is exacerbated by heightened global trade tensions, geopolitical conflicts, and a lack of consensus or cooperation in resolving trade issues through established multilateral channels, raising concerns about maintaining a unified rules-based system. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the perceived loss of trust in existing multilateral mechanisms, coupled with the rise of economic nationalism and concerns about fairness in trading practices, has also led to countries building up their own support measures while taking stronger action against policy measures implemented by others.

Subsidy spirals not only raise questions about the commitment to fair trade practices but also underscore the complexities within the global trading system. Countries, including the EU, have in the past pursued policies that aim to protect certain domestic economic interests, contributing, however, to a challenging regulatory environment. The apparent inconsistency and perceived hypocrisy in addressing subsidies through international mechanisms like the WTO highlight the need for a comprehensive and transparent approach to subsidies and trade practices.

The EU could adopt a multifaceted approach to address the escalating issue of subsidies and trade-distorting measures globally, as evidenced by the increasing instances of anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations.

- It is imperative for the EU to advocate for and adhere to rigorous state aid rules. This commitment is essential to safeguard fair competition between large Member States with greater fiscal capacities and smaller Member States, maintain the integrity of the internal market, discourage subsidy races, and encourage international competitiveness.

- The EU should actively participate in multilateral platforms, particularly within the framework of the WTO, to advocate for stringent, transparent, and enforceable rules pertaining to subsidies and not transparent behind-the-border measures. Collaborative efforts with other nations are essential to fortify the foundations of the multilateral trading system, thereby contributing to a less distorted global trade environment.

- The EU should solidify its regulatory influence by deepening cooperation through regional trade agreements. By setting high and non-discriminatory state aid rules within these regional partnerships, the EU can establish itself as a regulatory role model that others find attractive to follow, preventing subsidy spirals. The alignment of state aid rules can serve as a catalyst for other nations to adopt similar practices, promoting a global level playing field.

- The EU should assume a leadership role and seek for more active engagement in diplomatic initiatives, utilizing dialogue to address concerns about subsidies and trade-distorting measures.

Through these concerted efforts, EU policymakers would counteract global trade imbalances that are caused by high and potentially growing levels of subsidisation. The EU should position itself as a regulatory exemplar committed to as little intervention as possible to foster fairness and non-discrimination in global trade and investment.

[1] Global Trade Alert (2021). Subsidies and Market Access Towards an Inventory of Corporate Subsidies by China, the European Union and the United States: The 28th Global Trade Alert Report. Available at https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/gta-28-report.

[2] Data from the Global Trade Alert Database, accessed July 2021 (https://www.globaltradealert.org/data_extraction).

[3] Ibid.

4. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crises, the world witnessed a surge in protectionism, accompanied by a rise in regulations and trade barriers. Amid this global shift, the EU, historically a champion of open markets, competition and a liberal rules-based trading order, finds itself at a crossroads as it pursues Strategic autonomy. This departure from a liberal global trade order is marked by increasing regulatory burdens and fragmentation.

The EU’s pursuit of autonomy has led to a proactive regulatory stance, ostensibly aimed at aligning with global trends and addressing challenges. However, this shift has resulted in increased regulatory burdens on domestic and international companies within the EU, impacting the Single Market.

The evolving regulatory approach, coupled with insufficient regulatory cooperation and stalled free trade agreements, poses risks beyond the EU’s borders. The Brussels Effect, once celebrated as the EU’s ability to shape global regulations, now contributes to regulatory fragmentation. This phenomenon imposes costs and barriers on businesses, contradicting the open trade principles the EU has historically endorsed.

The EU’s Strategic autonomy paradigm may inadvertently inspire other nations to adopt protectionist measures, potentially fuelling a global regulatory spiral. The global implications of the EU’s evolving regulatory stance are particularly evident in services trade. Despite political support for cooperation, regulatory data reveal limited progress and ongoing regulatory fragmentation, including fragmentation in the EU’s internal market. Overall, the legal landscape governing trade and investment is creating a complex environment with varying and worrying patterns and trends among EU countries, OECD nations, and BRICS countries.

The rise in anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations further signals challenges within the multilateral rules-based trading order. The EU faces an urgent need to adopt a multifaceted approach, engaging in multilateral platforms, deepening regional trade agreements, and promoting sustainable trade practices to counteract global trade imbalances.

As the EU’s share of global GDP declines to 9% by 2050, it is imperative for Europe to elevate its regulatory prowess and cultivate innovation.[1] To maintain influence in shaping global rules and ensure competitiveness, policymakers must prioritise policies that unleash the collective potential of individuals and businesses to maintain high levels of productivity, competitiveness, and prosperity.

In response to the challenges presented by the EU’s changing regulatory strategy, it is imperative to consider several key policy recommendations:

- EU institutions and Member State governments must return to the principles of a liberal global economic order, placing economic freedom, government accountability, knowledge and innovation capacities, and prosperity as primary political goals.

- Internally, the EU needs to refocus on the neglected internal market. This requires a comprehensive strategy encompassing liberalisation, de-bureaucratisation, legal harmonisation, and tax code simplification. Regulatory coherence must be fostered through collaboration between EU governments and the European Commission, revisiting frameworks, streamlining regulations, and aligning approaches with Member State governments. The EU should engage in a constructive dialogue among Member States to identify areas of improvement, streamline regulations, and eliminate unnecessary barriers hindering the free movement of goods and services inside EU borders. Recognising the difficulties in achieving consensus among all the EU Member States, a pragmatic alternative is to promote regulatory coalitions among a group of willing nations. This approach allows like-minded member states to collaborate closely on regulatory harmonisation, creating more agile and specialised frameworks tailored to their shared objectives. By forming smaller coalitions, the EU can expedite decision-making processes and overcome the challenges associated with unanimity. This targeted integration can serve as a model for effective cooperation, fostering regulatory coherence and ensuring that the benefits of integration are realised without being hindered by the complexities of accommodating diverse interests within the entire EU.

- Globally, the EU and its member states should seek more regulatory cooperation, emphasising mutual recognition in the service trade. Efforts should be directed towards minimising barriers, ensuring an open and rules-based international trading system that preserves the benefits of global liberalisation.

- A flexible and adaptive approach to economic integration, underpinned by mutual recognition (or “interoperability of standards”) will enable the EU to respond effectively to evolving global dynamics while preserving the core tenets of open markets.

- To fuel intra-EU and extra-EU digital trade and trade in technology-driven industries, the EU should lead efforts in harmonising digital and technology standards both within the EU and in collaboration with international partners. Establishing common standards facilitates interoperability, reduces technical barriers, and fosters a seamless digital environment. Internally, the EU should work towards standardising regulations and practices across member states, ensuring consistency and clarity for businesses operating within the EU.

- Externally, the EU should embrace market-led standardization in international forums to develop global technology standards, enabling smoother cross-border digital trade. The adoption of common standards, as witnessed in global mobile communications industries, enhances trust among trading partners, encourages innovation, and stimulates the growth of technology-driven industries. Moreover, a concerted effort to align with global standards helps the EU position itself as a leader in the digital economy, attracting investment and facilitating international cooperation.

The EU’s role in increasing global regulatory burdens, fragmentation, and protectionism cannot be ignored. The EU must recognise the adverse repercussions of its evolving stance, promoting international coordination of trade policies and advocating for a strategic trade and technology alliance among market-oriented democracies. By returning to the principles of a liberal global economic order and strengthening the internal market, the EU can navigate the complex global trade landscape successfully, fostering fairness, sustainability, and economic progress.

In conclusion, the present challenges stemming from the EU’s evolving regulatory strategy demand unprecedented political leadership to recalibrate the trajectory towards a liberal and rules-based trading order, coupled with widespread regulatory liberalisation. To counteract the risks of global protectionism and regulatory spirals, a multifaceted approach is imperative. Internally, the EU should refocus on its neglected internal market through comprehensive strategies such as liberalisation, de-bureaucratisation, and legal harmonisation. Globally, the EU must prioritise regulatory cooperation, emphasising mutual recognition in services trade, and actively engage in developing common standards for technology-driven industries. A flexible and adaptive approach to economic integration, underpinned by mutual recognition, will enable the EU to respond effectively to evolving global dynamics, and also reassert the EU’s role as a driving force for global cooperation and economic development.

[1] PWC (2017). The World in 2050. Available at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/research-insights/economy/the-world-in-2050.html.