“Too Big to Care” or “Too Big to Share”: The Digital Services Act and the Consequences of Reforming Intermediary Liability Rules

Published By: Fredrik Erixon

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union

Summary

This paper reviews the Digital Services Act (DSA), a package of new rules for platforms proposed by the European Commission late last year. The paper takes stock of current and future situations for rules on content moderation and takedowns, and discusses how the DSA addresses the balance between the desired culture of openness online, on the one hand, and more pressures to take down not just illegal but harmful and objectionable content, on the other hand. The DSA introduces a few new transparency rules that follow previous codes of conduct: they are straightforward and desirable. However, it also brings in new know-your-customer rules and exacerbate the ambiguity surrounding the definition of illegal content. These types of rules will most likely have the effect that platforms will minimize risk even more by taking down more content that is legal. Moreover, there is a risk that the DSA will create new access barriers to platforms – with the result of making it difficult for smaller sellers to engage in contracts on platforms. New regulatory demands to monitor and address “systemic risks” will likely have the same effect: platforms will reduce their exposure to penalty risks by taking down and denying access for content that is legal but associated with risks.

The DSA’s differentiation between large platforms and very large platforms is disingenuous and contradicts the purpose of many DSA rules. Obviously, exposing some platforms to harder rules will lead to content offshoring – a trend that is already big. Objectionable content – not to mention illegal content – will move from some platforms to others and lead extremists and others to build online environments where there is much less content moderation. Furthermore, the new regulatory risks that come with being a very large platform will likely become an incentive for some large platforms to stay large – and not become very large. While the DSA is often billed as a package of regulations that will reduce the power of big platforms, it is more likely to lead to the exact opposite. Very large platforms have all the resources needed to comply with the new regulation while many other platforms don’t. As a result, the incumbency advantages of very large platforms are likely to get stronger.

ECIPE’s work on Europe’s digital economy receives funding from several firms with an interest in digital regulations, including Amazon, Ericsson, Google, Microsoft, Rakuten, SAP and Siemens.

Introduction

There is presently another round of new policies coming for intermediary liability and how various platforms should act to police content. In Europe, a Digital Services Act (DSA) was launched just before Christmas last year and it is aiming to reform aspects of the previous e-commerce directive, which did not make digital platforms legally responsible for content on their platforms but required the removal of illegal content when it had been flagged. Since then there have been several developments and efforts – in Brussels and elsewhere – to sharpen rules for the monitoring of platforms and to include not just illegal content but also harmful content. There is also variation in how countries in Europe have implemented current policy, leading to a somewhat fragmented and sometimes confusing situation for platforms that have to abide by laws and regulations in several EU countries. Unfortunately, the release of the Digital Services Act has not put idiosyncratic national efforts down to rest: several countries, including France and Poland, have recently introduced various types of regulations that relate to the behaviour of platforms, and these regulations sometimes differ quite substantially from each other. On some fundamental points, they are in conflict.

Change is called for if we are to have a digital single market in Europe. But the discussion would generally benefit from a better understanding of the trade-offs that come with some of the proposed approaches – and whether it is altogether possible to have a single-market solution while at the same time making proscriptive regulations that go to the heart of how constitutional liberties are constructed around Europe. Moreover, there is a fundamental conflict right at the heart of the debate on platform content – and, unfortunately, it isn’t resolved in any new legislative proposals of late. On the one hand, big platforms are tasked to police platform content a lot more and be faster in taking down illegal and, effectively, harmful content – otherwise risking huge fines. There is also a strong opinion demanding platforms to substantially increase their moderation of political views – ultimately to censor certain views from being expressed.[1] On the other hand, platforms are mandated to improve the culture of openness and not become censorious by deplatforming people who spread disinformation or express views that are seriously off-piste but that aren’t breaking the law. We have ended up in a very strange political situation. There is a bounty on the big platforms because they are too big and powerful – and yet, government are now about to give platforms increasing responsibilities that will have the effect of making them even more powerful.

Obviously, mandating more takedowns and more platform openness is a conflict that almost impossible to manage – you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t. It became painfully visible in the beginning of 2021 after platforms like Twitter banned many supporters of Donald Trump who had backed the storming of the Capitol or expressed related views that violated the Twitter Rules. Since then, many leading politicians and thinkers have expressed deep concerns about the role that platforms play for the political debate[2]: should people really be banned from platforms even if they haven’t violated any law? Surprisingly, some European politicians joined that chorus, despite knowing that current rules and codes in practice pushes platforms to use heavy-handed tools for content moderation that affects people expressing perfectly legal views. It’s not for nothing that, for instance, Germany’s network enforcement act, NetzDG, have alarmed human-rights campaigners.[3] Moreover, proposed reforms increase the pressure on platforms and will make them even more risk averse in their moderation policies. In essence, platforms will be taking down and censuring a lot more legal content in the future.

There is an important discussion to have about the public and private boundaries for big platforms, and how far governments and platforms should go in their efforts to moderate content and ban users. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter – and new ones that are now aspiring to growth like Parler and Clubhouse – are part of the virtual “public square”, and the liberal public ethos says that opinions and viewpoints should be freely expressed there as long as they don’t violate any law. But both platforms are also private entities and should be allowed to set standards that improve the user experience for all those who don’t want exposure to content that is legal but still extreme. So where should the line be drawn?

Governments that take a stand in this discussion also need to pay attention to the content – and not just the forum where it is expressed. There is a growing need to better understand the behavioural consequences that follow from heavy-handed approaches to content regulation – in essence, how various people, including those using platforms for illegal or harmful activities, will react to new rules. Would they really respond in the ways intended by the legislator?

It’s an important reality check. Some make the argument that online platforms are doing too little – if anything – to police content. Invoking the spirit of Commissioner Thierry Breton, who in a recent interview said that some big platforms are “too big to care” about user concerns, there is an underlying assumption that policymakers can tighten regulatory demands – without harming other ambitions – and then users would start to behave differently because of different mediation by the platforms.[4] If platforms just police their content better, problems will go away. In other words, if platforms just manipulate citizens better, we can reduce the power of those peddling nasty views.

The reality, of course, is far more complex. Big platforms, to state the obvious, already have user rules that prohibit illegal content and that lead to substantial content moderation. These rules have gradually been amended to accommodate their own and others desire to have an hospitable atmosphere for users. Facebook, for instance, has community standards that go far beyond illegal and harmful content. Now, users violate these standards, but – just like other big platforms – Facebook is spending growing amounts of resources to police content and take down illegal, harmful and objectionable content. YouTube, to take one example, took down 7.9 million videos between July and September last year and the review made of Europe’s Code of Conduct on hate speech suggest that 90 percent of notifications are attended within 24 hours. There is a case to be made for big platforms to spend even more resources – and Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and other platforms are making that case themselves. They have, in their own view, become too big to allow anyone to share whatever they want to share.

Companies that advertise on the platforms are also pushing for more actions by platforms: for instance, these three companies agreed last autumn with a large group of brands on new definitions of harmful content and new standards to police and report violations.[5] Therefore, the question for policymakers isn’t so much about whether more resources should be spent on policing user standards: all platforms are moving in the same direction. The question is rather what constitutes illegal and harmful activities, and if all platforms really are confronted with the same type of problem. This is important. All of the big platforms take down content that is illegal in the jurisdictions where they operate. But they also take down content that could be illegal because regulations instruct them to minimize risk. Added to that is a new layer of moderation that comes from political and commercial pressure, and that concerns – for want of a better word – “moral moderation”: the take down of content that is objectionable but legal. There is already a great deal of confusion coming from governments about what should be taken down, and there is a strong case now for governments to clear these things up. Moreover, if the regulatory scope for defining illegality is extended, where will people who no longer can use the big platforms go? What type of policies are required to avoid that regulations just leads to a reallocation of problems from one platform to another?

In this paper, we will discuss the proposed Digital Services Act in light of the fundamental issue raised above: how to balance the defence of a “culture of openness” – or, to put it in extreme terms, free speech – with content-moderation demands? Moreover, we will review existing knowledge about what happens when users are banned and content moves other platforms where no moderation is applied. The paper also provides an overall judgment about the Digital Services Act and argues that central planks of it should be seriously reworked to avoid choking the single market and new competition to the big platforms. While the DSA is billed as a regulation that will bring big platforms like Amazon, Facebook and YouTube to heel, the reality is that the Act would bring in new obstacles to digital entrepreneurship and platform competition, and make it harder for smaller platforms to grow a lot bigger. That effect gets even stronger when new DSA rules will build on the proposed rules in the Digital Markets Act. Equally, while it is a good soundbite that the DSA will make everything that is unlawful offline unlawful online, the reality is far more complex. The DSA will most likely make it unlawful to do certain things online on some platforms that are perfectly legal offline.

[1] Paul Barret and Grant Sims, 2021, False Accusations: The Unfounded Claim that Social Media Companies Censor Conservatives. NYU-Stern, Center for Business and Human Rights. Accessed at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b6df958f8370af3217d4178/t/60187b5f45762e708708c8e9/1612217185240/NYU%20False%20Accusation_2.pdf

[2] This debate is increasingly moving outside platforms and also include Internet Service Providers and other digital services, for instance – as in the case with Cloudfare and 8chan – services that protect against DDoS attacks. See Ben Thompson, A Framework for Moderation, Stratchery, August 7, 2019, accessed at https://stratechery.com/2019/a-framework-for-moderation/

[3] Human Rights Watch, 2018, Germany: Flawed Social Media Law. Accessed at https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/14/germany-flawed-social-media-law

[4] Javier Espinoza and Sam Flemming, EU seeks new powers to penalise tech giants. Financial Times, September 20, 2020. Accessed at https://www.ft.com/content/7738fdd8-e0c3-4090-8cc9-7d4b53ff3afb

[5] Alex Barker and Hannah Murphy, Advertisers strike deal with Facebook and YouTube on harmful content. Financial Times, September 23, 2020. Accessed at: https://www.ft.com/content/d7957f86-760b-468b-88ec-aead6a558902

The Digital Services Act: an Appraisal

The Digital Services Act provides for new information and transparency requirements on platforms, and especially very large platforms with more than 45 million monthly users in the EU. Some of these requirements are pretty straightforward and only define some new elements related to user rights. For instance, online platforms and hosting providers should have user-friendly systems for notifications of illegal content and also provide appeals mechanisms for users who have been banned or whose content has been subject to moderation actions. If content is removed, the platform needs to motivate its actions to those who had uploaded it and they should also report what actions that are taken to remove illegal content or content that violates their own user rules. Much of this is pretty straightforward and follows the conduct rules that have been agreed between the EU and some large platforms already.

Other proposed rules are far less straightforward and will add substantial new provisions to the existing body of mandatory rules. Obviously, these rules will have an effect on how platforms behave – some of which are intended, others that are unintended. For instance, the DSA introduces new “know-your-customer”-type of rules, which means that platforms that allow users to contract on their platforms in essence need to verify the legality of the parties and the goods that are involved in the transaction. In its current form, the DSA seems to suggest that platforms should also do so without using generic tools – like relying on a payment provider to vouch for the seller and keep a record of the transactions, so there is full traceability.

The obvious consequence of such rules, which take their inspiration from the EU money-laundering rules on banks, is that some commerce now taking place on some platforms won’t be possible in the future. Some of these transactions will of course be illegal. But a lot of perfectly legal transactions are likely to be exempted as well. Why? The specific DSA provision itself is so open-ended that it is hard to see how several platforms could technically and economically abide by them without just denying access for big swathes of traders – especially small-firm sellers and individuals who sell private goods on an online market. After all, a platform generates too little revenue from brokering trade between small sellers and niche buyers to motivate the KYC cost that will come, or the penalty risks associated with not keeping tabs on everything that may have been contracted on a platform. The simplest approach is to set the standard for selling so high that it can only include platform customers that generate revenues that are big enough to motivate the costs.

Another set of new provisions relate to very large platforms. Apart from some administrative requirements – for instance, having an independent DSA audit – these platforms will now become mandated to disclose the algorithm used to rank content. Users should be allowed to modify algorithm parameters, but also have option of choosing a solution that includes no profiling. Very large platforms are also going to be under other demands that require them to hand over other trade secrets, like keeping a repository on advertisements shown on the platform that should be open to outsiders.

It is fair to say that the Digital Services Act doesn’t directly change the liability exemptions for intermediaries, but it is obvious that the EU seeks to do so in an indirect way. Putting platforms and especially very large platforms under prescriptive rules, and threatening them with very substantial fines if they don’t comply with these rules, is effectively the same thing as diluting the liability exemption directly. Or to put it differently, liability exemptions is only relevant when a platform never feature anything that may be illegal.

There are other factors pulling in the same direction. Under the DSA, very large platforms will come under new obligations to monitor “systemic risks” and take actions against these risks. But the risk of someone on a platform violating the law is not the same thing as someone actually violating the law. This is another effort that will push platforms to be risk averse. Addressing systemic risks in practice means moderating a lot of things that are perfectly within the boundaries of the law. Take the storming of the Capitol as an example. There were very many individuals there who have been peddling conspiracies online about the “deep state” stealing the election and planning to poison people with the Covid-19 vaccines – or that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles is running the country. But many people who were banned from platforms for expressing these weird views – which are legal – had nothing to do with the planning or the actual storming of the Capitol. So how will platforms monitor systemic risks and take action against them in such a case? Is there any other way to do it than just to ban a lot of people or censor certain legal views? The result is that platforms will have to do a lot more behavioural moderation and block users rather than their content – and is that really what European legislators want platforms to do?

Moreover, the DSA also brings in a lot of “constructive ambiguity”: it works with definitions that are unclear and that would require platforms to take a very cautious approach. For instance, while the DSA says that the act itself is not providing a clear definition of what is illegal, it expands the scope of illegality to include “reference” to illegal activities – not just illegal content itself. Given that a German court has convicted a person who made a reference in a post to a media article showing illegal activities, the matter is not just academic. It goes to the heart of freedom of speech. Moreover, the DSA also requests in some instances, involving criminal offenses, that platforms should act as law enforcement agencies by making a judgement of their own suspicions and report them if they believe that suspicions are real. Thus, the DSA extends the privatization of justice that some other regulations have opened up for.

The results of these new rules are predictable: platforms will need to moderate more rather than less, and they will need to take down a lot more content that isn’t illegal. Obviously, platforms will need to take the safer route of preventing access to the platform when it is not possible for the company itself to determine whether something should be seen as an illegal activity. It simply isn’t a credible argument to say that the DSA preserves exemptions from intermediary liability. It makes the distinctions between a private and a public operator even more ambiguous. It is an insidious and unnecessary attempt to blur the line between reasonable demands on a private platform and what is gross regulatory overreach.

Separating Platforms from Very Large Platforms

It is clear that the DSA attempts to make a distinction between different types of platforms, and that the main criteria that is used for that distinction is platform or firm size: the number of users. There is a similar approach in the sister-regulation to the DSA – the Digital Markets Act – which singles out platforms that are judged to be “gatekeepers” on their size and give them a particular regulatory embrace. This approach is unfortunate. While it is sometimes natural to make a difference between large and small firms in the way they are exposed to regulations, it doesn’t necessarily follow that illegal content or other forms of bad behaviour are more prevalent in the big rather than the small context – on the very large platform rather than on the not-so-very-large platform. The reality, of course, is that there is huge variation between platforms and that one category of online platforms are not exposed to the same problems as other categories of platforms. Quite often, size is not the issue that determines the relevant risks.

This is where the DSA ends up in a strange place. Behind this initiative are recurring discussions about need to redouble efforts against online illegal activities and hate speech. These are perfectly valid policy concerns and should receive a lot more attention. But the DSA comes with a lot of political panache, and it has been far too obvious in comments and viewpoints from the relevant Commissioner that the substantive concerns are secondary to the desire to get many of the big US platforms under the thumb of European politicians.

However, that ambition may undermine worthwhile efforts to achieve substantial improvements. In the case of the DSA, the desire to expose the very large platforms to certain type of rules that other platforms don’t need to bother with can lead to a migration of illegal content from some platforms to others – from very large platforms, where they are more controlled, to smaller platforms, which have a larger freedom of operation. For hate speech, for instance, the problem is not just about big platforms. Big platforms are not “too big to care” but we see a migration of hate speech to smaller platforms that aren’t too big to allow anyone to share. Moreover, the gap in regulatory exposure created between online platforms and very large online platforms can become a barrier for smaller platforms (and their financial backers) to grow and become very large – but who doesn’t want the regulatory risks that comes with the accreditation. Neither of these risks are negligible.

Off-shoring bad content to smaller platforms

There is a substantial body of research and analytical work now that suggests content moderation efforts and the cancellation of extremist accounts by big platforms have had two main consequences. The first consequence is that fewer people on the big platforms will be exposed to extreme content. Among other things, this means that there won’t be as easy for extremists to build up a following and recruit new souls to their causes. The second consequence is that the extremist themselves will migrate to other and smaller platforms, and that they will use platforms services that offer encryption. That tends to lead to a radicalization of the extremists and that they can discuss and operate with far less scrutiny compared to if they had stayed on the big platform.

There are different forms of illegal content online and there is no single concept of risk that unifies all the platforms. Some illegal actors want to be in a highly populated environment, others prefer to work in more closed settings. If someone, for example, wants to spread disinformation about vaccines, it helps to be on a social media platform with many users because then more people can be reached. Likewise, for extreme groups looking for new recruits, it can be useful to have a strong presence where other people move around – like Facebook and Twitter. Britain First, for instance, used Facebook to build up a strong following by posting a lot and doing so in a way that showed a friendly and civilized face. Then its leaders were convicted of hate crime and in March 2018 the organisation’s account was removed by Facebook. Two months later it had built up a presence on Gab, the alt-tech social networking service with about 3.5 million users.

Obviously, the effect was a drastic reduction in the number of people who was exposed to posts from Britain First. In a study of Britain First, and its migration from Facebook to Gab, scholars of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) concludes that content and account removal clearly have an effect on an extreme organisation’s ability to reach viewers. When someone no longer can use Facebook and Twitter, the pool of people they can interact with gets smaller. Other extremists organisations and individuals have had the same experience when they have been blocked from major social media platforms. A strong case can also be made that removals by social media have purged these platforms from Daesh propaganda and the risk that non-extremists would casually get exposed to posts inciting or romanticizing terrorist activities.

But there is also something else that happens to organisations that are removed and that migrate to smaller platforms. They don’t just close shop and go away: on the contrary, many of them gets radicalized and potentially more dangerous. The RUSI scholars write: “Further, removal from Facebook has brought about changes in the types of images Britain First posts online. Despite the decrease in followers on Gab, the themes found in Britain First’s imagery demonstrate a move towards more extreme content in the course of their migration to Gab, likely due to the platform being less likely to censor content.”

Another example can be taken from more recent events. After the storming of the US Capitol in January, scholars found that supporters of QAnon and “Stop the Steal” circulated material that instructed people where they should migrate to be able to speak more freely without invasive content moderation by platforms. Facebook users were told to switch to Parler and MeWe. Likewise, those who had been on Twitter should log onto Gab and SpeakFreely. There were also instructions for which search and messaging platforms to move to. Since then, there has been a huge increase in the number of users of alt-tech platforms – and all of the new users aren’t of course associated with a conspiracy or an extreme cause. But the point is that this migration had already started a long time before the demonstration on January 6th and that followers of extremists and conspiracy theorists on these platforms weren’t surprised about how the demonstration unfolded. It had been discussed there for quite some time – or, as the National Public Radio, said in a news story: “Plans to storm the Capitol were made in plain sight.”[1] It’s just that, on these platforms, very few others were watching what was going on.

A study for the European Commission project SCAN – a project aiming to build up expertise on online hate speech – show the rapid growth of the alt-tech platforms and how extremists are also using some common but smaller online platforms like Tumblr, Pinterest and Discord.[2] In addition to platforms like Parler, MeWe and Gab, the alt-tech ecology includes platforms such as VK.com, Telegram and Rutube.fr – all platforms with user guidelines but that don’t moderate content to the same extent as the big platforms. The study concludes that extremists don’t just give up when they are removed from the big platforms: they migrate to smaller platforms and use various means to communicate to followers where they are operating. Some extremists, like those who were part of the Blabla forum on Jeuxvideo.com, build their own web environments. A recent case from Sweden illustrates this development. A new platform has been established for a hotchpotch group of people who stages demos against pandemic restrictions and the Covid-19 vaccination programme. Outside of the content moderation programmes from major platforms, users can freely discuss and coordinate their activities – and they can do so without facing opposition and counter-arguments from other users. The result isn’t just that this platform quickly builds up a sizeable number of users; posts, messages and activities also get more extreme.[3]

It is not surprising that extremists find alternative ways to communicate online.[4] They have been using network communications for a long time and were quick seize new opportunities in the 1980s with pre-web bulletin board systems and other forms of data connectivity. With the arrival of social media, they got new opportunities to build up an online presence that allowed not just these groups to organise but also to connect with each other at larger scale.[5] But now, when many of these groups have been purged from the big platforms and cannot really find connectivity opportunities there, they are moving elsewhere and are early adopters of the new wave of online platform mobility. In many respects, extremists and conspiracy campaigners are moving away from Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.[6]

Part of this trend is driven by policymakers and governments. The EU already have policies to combat online extremism and hate speech. Since 2016, its Code of Conduct has pushed online platforms to invest more in content moderation and other mechanisms addressing online extremism. There are also policies to tackle counterfeit goods and online terrorism. Last December, for instance, a new regulation was agreed on countering online terrorism, which includes the “one hour rule” demanding that terrorist content should be taken down very fast.[7] Importantly, the new regulation includes a definition of terrorist content – making it clear to platforms what it is that should be removed and avoiding mass removal of legal content.

The DSA is different: it avoids an explicit definition of illegal content but puts demands on especially very large platforms that cannot be interpreted in any other way than that the Commission wants to expand the definition to include some legal but harmful content. There are clear risks with this strategy. There is already a migration away from big platforms by people who aren’t political extremists but peddle disinformation (anti-vaxxers, for example) or claim that big tech suffers from leftist biases. New demands on all platforms to use more heavy-handed content moderation will of course accelerate this development.

The distinction between online platforms and very large online platforms is disingenuous. While there is more to do from the very large platforms to remove illegal content, the simple fact is that the big platforms are already inhospitable environments for extremists and others who are engaging in illegal activities. Some of the big platforms are increasingly efficient at capturing both illegal and seriously harmful content, and numbers suggest that they are also getting hold of content that yet hasn’t caused much damage. YouTubed, for instance, reported that between July and September last year it took down almost 8 million videos – and that three quarters of the removed content has received fewer than 11 viewers.

Surprisingly, the DSA doesn’t have much to say about the new online migration. If political extremism has now moved to platforms that is under more relaxed rules, wouldn’t you think that policymakers rather would be looking there? DSA rules are unlikely to affect them much. Few of the alt-tech environments have any revenues to speak of – there aren’t many businesses who are interested to put ads there – which make the financial penalty a weak threat in the event that these platforms don’t follow the rules that apply to all online platforms. The risk is that the DSA’s principle of differentiation will incite more offshoring of illegal, harmful and normal content to platforms with a different attitude to content moderation.

Creating new barriers to growth

By creating a regulatory gap between online platforms and very large online platforms, there is a risk that the regulatory system becomes a barrier to growth for platforms, and that fewer platforms want to become very large and expose themselves to much greater regulatory-financial risks. Indeed, there is a clear risk that those who fund business expansion would become less inclined to invest in late-stage financing of platforms – when you invest to go from big to very big – if the accreditation of being a very large platform effectively means stepping into a different regulatory environment.

These risks shouldn’t be underestimated. The regulatory differentiation between an online platform and a very large online platform doesn’t come just from the Digital Services Act. The Digital Markets Act work with a similar approach, and when these two acts are added to an already existing body of regulations that seeks to make life more difficult for the really big platforms, it is obvious that the regulatory risks in some areas of the digital economy would become so big that it begs belief to think that the rewards from becoming very large are proportionate to the increased risks. Which pension fund or private equity operator would put substantial capital into making a new platform very large if it effectively means that it would have to purge a substantial number of users from the platform?

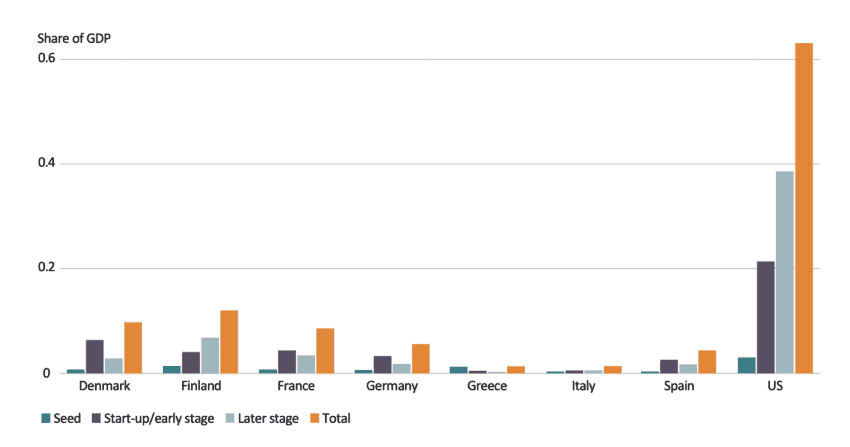

For Europe, the issue is also about financials: are the capital market conditions good enough to motivate expansion from Europe? Notably, EU countries are already struggling to keep up with venture capital funding of digital entrepreneurship – and the gap between the EU and the US becomes wider in later-stage financing than in early-stage financing. Since 1995, it has been estimated that the US has invested 1.2 trillion US dollar in venture capital for startups, while the similar figure in Europe is 200 billion US dollar – a six-times difference. It is true that Europe has been catching up a bit with the US in recent years, but the gap remains stark. Moreover, the gap becomes even more significant in later-stage financing of growth (see Figure 1). Europe has particularly been catching up in the financing of the growth phases of firms. In later-stages, however, Europe is far more reliant on venture capital from the US and Asia.[8] Generally, the type of later-stage funding that is the more common route for European firms is an initial public offering – that is, to go public.

Figure 1: European and US Financing by Stage (share of GDP)

Source: The Organisation for Economic and Development Cooperation, Entrepreneurship Financing database.

Source: The Organisation for Economic and Development Cooperation, Entrepreneurship Financing database.

The regulatory environment affects the scale-up phase in different ways. First, capital markets regulation in Europe – especially the regulation of large institutions like pension funds – makes it more difficult to generate a rapid increase in the pool of capital available to late stage venture capital investment. Second, market restrictions (especially in services) are generally higher in Europe than in other developed economies like Australia and the United States – and those restrictions push up barriers to entry. Importantly, these competition-decreasing market regulations have a distinct effect on business churn rates and is one explanation to why it’s more difficult to grow and scale up entrepreneurial projects and new business models in Europe.[9]

Since later-stage funding usually includes investment to expand in new countries and regions, Europe’s fragmented single market isn’t helpful. Europe isn’t a common language area that makes it easy to grow, and natural barriers to firm growth and scalability are therefore a clear disadvantage. Added to that are market policies in Europe that are still very far away from the idea of one single market. Now comes, on top of that, new digital service regulations of very large platforms that expose firms with presence in more than a few EU countries, and that have sizeable number of users, to a lot more regulatory restrictions. It should be obvious that these regulations will have the effect of exacerbating already existing barriers to growth. Indeed, it is likely that for some growing platforms in Europe, these restrictions will have a preventive effect.

[1] Laurel Wamsley, On far-right websites, plans to storm Capitol were made in plain sight. National Public Radio, January 7, 2021. Accessed at: https://www.npr.org/sections/insurrection-at-the-capitol/2021/01/07/954671745/on-far-right-websites-plans-to-storm-capitol-were-made-in-plain-sight?t=1610966467779

[2] sCAN Project, 2019, Beyond the “Big Three”: Alternative Platforms for Online Hate Speech. Accessed at: http://scan-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/scan-analytical-paper-2-beyond_big3.pdf

[3] Sveriges Radio, Konspirationsteorier sprids på ny svensk plattform. Published March 19, 2020. Accessed at: https://sverigesradio.se/artikel/svenskt-konspirationsnatverk-startar-egen-plattform

[4] Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens and Logan Macnair, 2019, Right-Wing Extremists’ Persistent Online Presence: History and Contemporary Trends. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. Accessed at: https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2019/11/Right-Wing-Extremists-Persistent-Online-Presence.pdf

[5] Mattias Ekman, 2018, Anti-refugee Mobilization in Social Media: The Case of Soldiers of Odin. Social Media+ Society, 4(1), pp. 1-11.

[6] Richard Rogers, 2020, Deplatforming: Following Extreme Internet Celebrities to Telegram and Alternative Social Media. European Journal Of Communication, vol. 35:3, pp. 213-229.

[7] European Commission, Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on preventing the dissemination of terrorist content online. European Commission COM (2018) 640 final, 2018/0331 (COD). Accessed at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2372

[8] Stripe and techeu, 2019, Blooming Late: The Rise of Late-Stage Funding for European Technology Scale-ups. Accessed at: https://tech.eu/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/05/Blooming-Late_FA.pdf

[9] Robert Anderton, Benedetta Di Lupidio, 2019, Product market regulation, business churning and productivity: evidence from the European Union countries. ECB Working Paper No. 2332.

Concluding comments

Europe should go back to the drawing board and revise the new Digital Services Act: it isn’t fit for purpose. It’ fanciful, in the first place, to think that this act will bring big platforms to heel. Amazon, Facebook, YouTube and other platforms covered by the full effects of the DSA have the resources needed to comply with the new regulations without business being affected: they will reduce platform access for users that aren’t generating much revenues anyway. These platforms also have collected a lot of experience in using new regulations as a competitive tool: they know how to flip regulations into a barrier of entry or growth for competing firms. Just like with other excessive regulations in the area of digital technologies, the DSA is more likely to entrench current platforms and their incumbency advantages – not challenge them. It is pretty remarkable that European politicians are selling new regulations that will hand more power to big platforms as something that will take away their power.

It is also unlikely that this Act will help to improve the digital single market and create a better environment for European firms that would like to expand fast outside a few countries and reach a high number of users. After all, that would take them into new regulatory categories in the DSA, and the regulatory risks would go up. Since platforms have played a crucial role in actually making the digital single market real, behavioural constraints of platforms could have the effect of making the single market less single. The current big platforms will be around, but the new ones that could help to drive much greater market integration in Europe will face new barriers.

Worryingly, it is also uncertain if the format of the DSA will help to harmonise Europe’s regulations and, at the least, create a legal and nominal single market. The Act itself is a bit shy when it comes to protecting the country-of-origin principle and the debate that has unfolded after the release of the DSA suggests that there isn’t strong support for a unified approach across Europe. Indeed, some governments have proposed implementation and other regulations that would undermine the origin principle. Part of this concerns the direct commercial-policy aspects of the Act and the extent to which individual governments will be able to go beyond the mandated behavioural norms of the Act. For the moment, it looks unlikely that France and Germany would accept that.

There is also a deeper element to it: Europe doesn’t have a certain constitutional code when it comes to what is legal and what isn’t legal to say online as well as offline. There are limits to the freedom of expression in some countries that don’t exist in other countries, and this is why the Act itself says that national laws will apply. Moreover, countries have also different type of institutional cultures when it comes to how they are approaching issues that concern the laws and institutions governing core civil liberties online, and how they relate to constitutional practices for offline liberties. Much of the work needed to build up new institutions and practices for how online liberties are governed is in its infancy. While some of this work can take place in the EU, a good portion of it will inevitably come down to national politics and national institutional culture.

A revised DSA approach could build on this development. The current DSA already suggests that there should be access to out-of-court settlements for platforms and their users. This approach, in its current form, is too unwieldy. It is simply impossible to have settlement procedures for every person who file a complaint against a platform that have removed something online. Obviously, there will have to be limits to what a settlement procedure can include and what injury that entitles access to a complaint procedure. Naturally, some of this development need to connect with institutions and practices that have been established in every EU member country to deal with freedom of expression and access to the public square offline.