Digital Companies and Their Fair Share of Taxes: Myths and Misconceptions

Published By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union

Summary

Some (large) EU governments are making the case for digital companies to pay “their fair share of tax”. The key underlying assumption is that companies in the digital space are not doing so right now. Governments also assume that there is a substantial source of untaxed profits that is waiting for the embrace of the taxman. The European Commission is now considering “revenue taxes” on those companies that under some definition can be called “digital corporations”. In this paper, we provide a critical assessment of the underlying reasoning of the European Commission and those EU governments that currently are in favour of targeted taxes on digital revenues.

There is indeed a good case to make for fair taxation and that uneven effective tax rates can distort competition and lead to smaller tax revenues. However, those that are calling for higher taxes on one particular group of firms – digital corporations – have yet to present the evidence for why that is motivated by principles of fair taxation. The European Commission’s “hypothetical” estimates for effective corporate tax rates (ECTRs) do not reflect the high effective corporate tax rates of most corporations that operate in the EU and outside EU Member States, including the world’s largest digital enterprises.

In addition, the European Commission’s selective focus on digital companies that are big on “stock markets” mixes up market capitalization with corporate income. Thereby, the focus on the world’s “top 100 companies by market capitalisation” and the world’s “top 5 e-commerce companies” hardly reflects the reality of the digital economy and profit levels among different, often highly diverse, firms. Real world financial data show that the average corporate tax rates of many digital companies actually exceed the European Commission’s “hypothetical” estimates by about 20 to 50 percentage points.

Ideas to slap a targeted tax on digital revenues clash with the EU’s top policy priorities for the digital economy. It is therefore remarkable that such taxes even are considered. A tax on digital revenues would not only stand in opposition to tax efficiency and neutrality; it would also undermine digitalisation, European integration, and the Digital Single Market.

Research assistance by Nicolas Botton is gratefully acknowledged.

Introduction

Some governments in Europe are making the case for digital companies to pay “their fair share of tax”. Obviously, the key underlying assumption is that companies in the digital space are not doing so right now, and that there is a substantial source of untaxed profits that is waiting for the embrace of the taxman. The European Commission has also weighed in and, flanked by a few powerful EU governments, is now considering a new revenue tax on companies that under some definition can be called “digital corporations”.[1] (European Commission 2017a)

It is difficult to make sense of this debate – and the actual proposals. For starters, the European Commission does not specify what makes a company digital, let alone where to draw a line between more digital, less digital or non-digital business models. Moreover, it remained open what exactly falls within the scope of a tax on digital revenues. Indeed, the OECD’s digital economy group, who looked at this same issue for more than 2 years, concluded that it was in fact impossible to put a fence around the “digital economy” (OECD 2015; 2014).[2] Given that digitisation is a feature of all industries and that many non-digital sectors now feature digital business models, decisions about what firms that would deserve the special embrace by tax authorities would inevitably be arbitrary and become a source of significant competitive distortions.

Other EU bodies have thrown their weight behind new proposals for taxing digital firms (e.g. the European Council of December 2017) and (only) 10 EU Finance Ministers, who have co-signed a joint political statement in favour of “a so-called ‘equalisation tax’ on the turnover generated in Europe by the digital companies.” Like the authors of the European Commission’s official Communication, the Council does not provide any additional clarity regarding the defining characteristics of a digital corporation, let alone the tax bases taken into consideration. Aware of national obligations from international tax agreements, the Council demands, however, that an “equalisation levy based on revenues from digital activities in the EU” should “remain outside the scope of double tax conventions concluded by Member States.” (European Council 2017 pp. 1)

In this paper, we will assess these ambiguous ideas in the context of real observable data for less or non-digital companies on the one hand and digital corporations on the other. In Section 2, we provide a critical assessment of the underlying reasoning of the European Commission and those EU governments that currently are in favour of targeted taxes on digital revenues and establishment requirements. In Section 3, we outline prevailing myths and misconceptions about digital/online firms and their actual situation regarding profit margins and tax expenses, and we compare them with the same observed data for companies that operate in more traditional sectors. This part of the paper will largely focus on the underlying assumption that there are huge reserves of untapped or untaxed profits. Section 4 summarises the results and concludes.

[1] DG TAXUD: Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union. In September 2017, the Finance Ministers of France, Germany, Italy and Spain announced that ‘[w]e should no longer accept that these [digital economy] companies do business in Europe while paying minimal amounts of tax to our treasuries. Economic efficiency is at stake, as well as tax fairness and sovereignty.’ They further ‘ask the EU Commission to explore EU law compatible options and propose any effective solutions based on the concept of establishing a so-called “equalisation tax” on the turnover generated in Europe by the digital companies.’ See Eurogroup 2017.

[2] OECD (2015, p. 11) comes to the conclusion that “[b]ecause the digital economy is increasingly becoming the economy itself, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to ring-fence the digital economy from the rest of the economy for tax purposes.” OECD (2014, p. 24) argues that “[a]ttempting to isolate the digital economy as a separate sector would inevitably require arbitrary lines to be drawn between what is digital and what is not.”

Why is the EU Contemplating a Tax on “Digital” Revenues

In its Communication last year on a “Fair and Efficient Tax System in the European Union for the Digital Single Market”, the Commission calls for efforts to “stabilise the tax bases of the individual Member States, and ensure fair competition and the flourishing of companies operating within the Single Market.” It is argued that “international tax rules […] no longer fit the modern context where businesses rely heavily on hard-to-value intangible assets, data and automation, which facilitate online trading across borders with no physical presence.”

Aware of the “lack of international consensus” on how to tax traditional and digital corporations in general, the Communication calls on EU Member States to consider “short-term measures […] to protect the direct and indirect tax bases of Member States.” The “shorter-term solutions” proposed by the Commission are also sketched:

- Equalisation tax on turnover of digitalised companies: A tax on all untaxed or insufficiently taxed income generated from all internet-based business activities, including business-to- business and business-to-consumer, creditable against the corporate income tax or as a separate tax.

- Withholding tax on digital transactions: A standalone gross-basis final withholding tax on certain payments made to non-resident providers of goods and services ordered online.

- Levy on revenues generated from the provision of digital services or advertising activity: A separate levy could be applied to all transactions concluded remotely with in-country customers where a non-resident entity has a significant economic presence.

It is not yet clear whether the Commission aims for taxing all digital revenues or revenues from advertising services only. Similarly, it is unclear if the Commission aims to ring-fence, i.e. explicitly discriminate, non-EU companies or not.

The European Commission’s line of argument

In its Communication, the Commission argues that “policy makers are struggling to find solutions which would ensure fair and effective taxation as the digital transformation of the economy accelerates.” Contrary to a core objective of the Digital Single Market (DSM) strategy (European Commission 2015), the Communication actually argues in favour of treating digital corporations differently from other companies. Furthermore, it is claimed that the current failure to “fairly tax” digital corporations leads to more opportunities for tax avoidance, which negatively impact on social fairness and “puts at risk EU competitiveness, fair taxation and sustainability of Member States’ budgets.”

A revealing part of many claims of this kind, however, is that they are not substantiated by actual data and evidence. It is only assumed rather than proven by real-word data that a special category of firms pays too little tax. In addition, the Commission and some Member State governments that call for more taxation on these firms do not give supporting evidence that a new form of taxation actually would raise tax revenues and that it would not impact negatively on the competition between competing business models.[1]

Fairness and sustainability in taxation

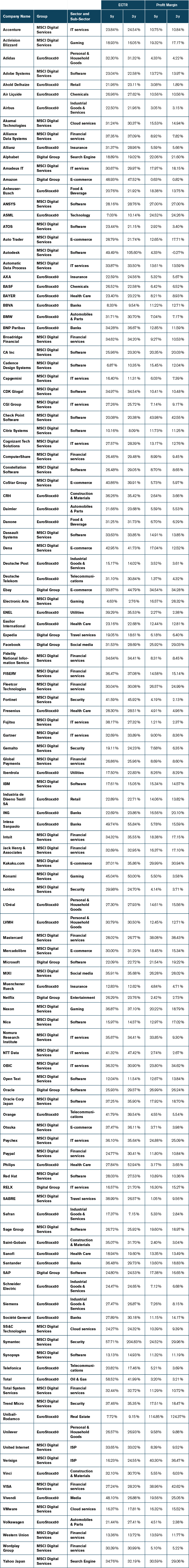

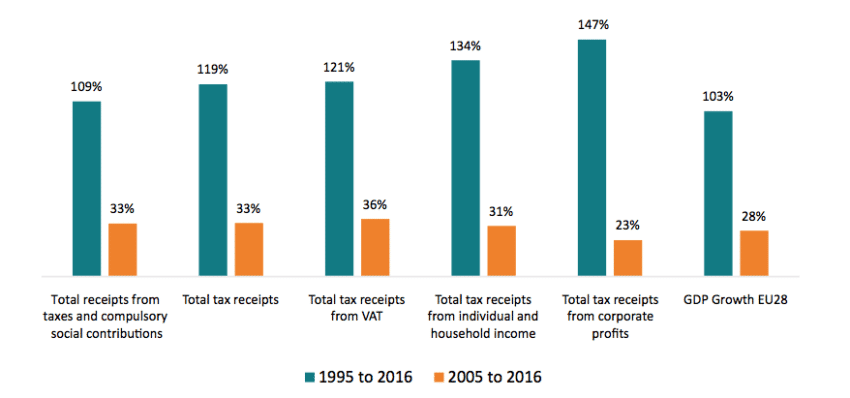

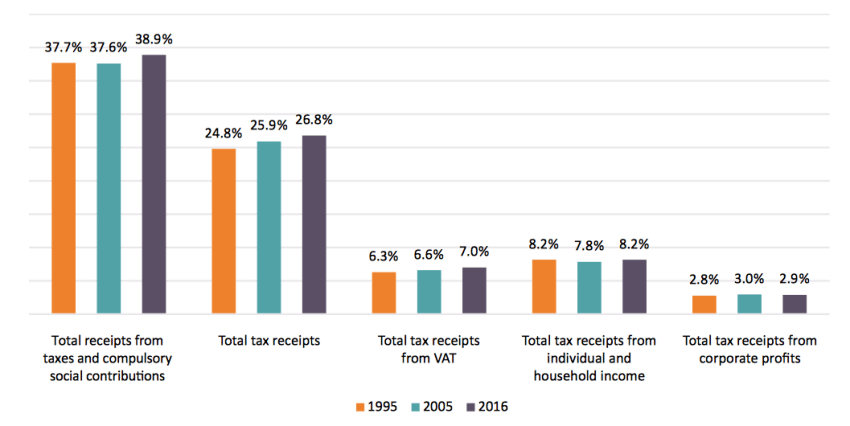

Considering the actual development of overall EU tax receipts, it becomes immediately obvious that calls on more taxation of digital corporations are troubling. In fact, the actual development of overall EU tax receipts suggests that there is not much of a “failure” in Europe in tapping profits and that this threatens the sustainability of public finances. Over the past 20 years, the growth of overall government tax revenues in the EU (119 percent) was significantly higher than overall EU GDP growth (103 percent). Tax revenue data demonstrate that a significantly higher amount of both household and corporate income has been collected by EU governments since 1995 (see Figure 1).

Moreover, it is apparent that, since 1995, revenues from taxes on corporate income show by far the highest growth rate compared to other forms of taxation, i.e. (sales) taxes on value added (VAT) and taxes on individual and household income. Increasing by 147 percent from 1995 to 2016, the growth of overall EU government revenues from taxes on corporate profits exceeded the growth of general tax receipts by not less than 28 percentage points.[2] Accordingly, between 1995 and 2016 the share of overall tax revenues in the EU relative to EU GDP increased by 2 percentage points to now 26.8 percent (see Figure 6 in the Appendix).

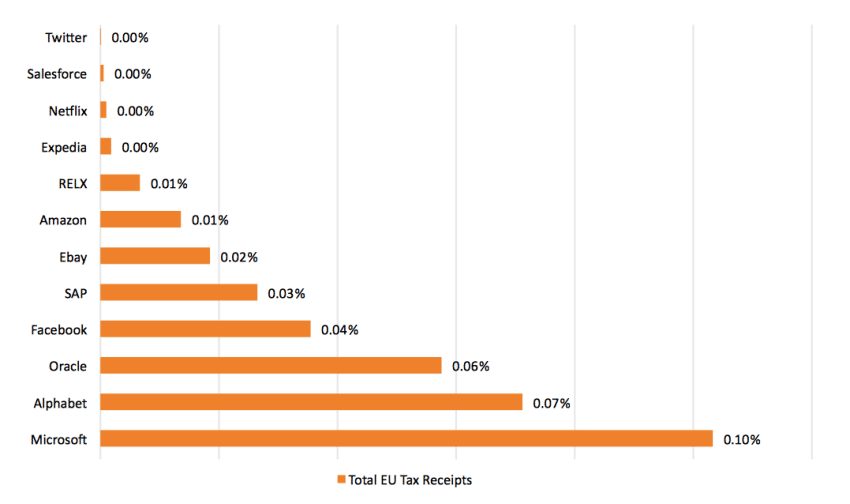

While aggregate data on revenues from corporate income taxes do not deny the claim that some companies may pay too little in tax, let alone that some companies may be illegitimately evading taxes, it is notable that the overall share of taxes from corporate profits relative to GDP remained constant over the past 20 years. Consequently, views about “tax base erosion in the EU” as a whole are exaggerated, and the same verdict is true for the statement that the rise of the digital economy has exacerbated corporate tax base erosion. EU countries’ tax data rather indicate that the digitisation of the economy has, overall, not impacted tax revenues and base erosion. In addition, it should also be noted that even if EU Member States were able to collect the total taxes paid by the world’s largest digital corporations, the amount collected would not make an impact on the sustainability of public finances in the EU (see Figure 7 in the Appendix).

Figure 1: EU growth rates of government tax receipts, 1995 to 2016 and 2005 to 2016

Source: Eurostat, OECD. Note: for total receipts from taxes and compulsory social contributions, 1995-2016 growth numbers are depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts, 1995-2016 growth number are depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts from VAT, 1995-2016 growth numbers reflect the EU28 ex Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia. For total tax receipts from individual and household income, Eurostat numbers are only available for the EU28 ex Germany, Estonia, Spain, Croatia, Hungary, and depicted accordingly. For total tax receipts from corporate profits, Eurostat and OECD data are not available for Spain, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, while OECD data on tax revenues in national currency (EUR) have been added for Germany and Estonia.

Digital firms are not just big

It is also revealing that much of the thinking in Europe about taxing digital companies more is only occupied by big and listed Internet companies. Obviously, there is rich variety in how various firms perform in profit and taxation, and that is true also for companies that run digital business models. The selective focus on digital companies that are big on “stock markets” mixes up market capitalization with corporate income. A focus on the world’s “top 100 companies by market capitalisation” and the world’s “top 5 e-commerce companies” hardly reflects the reality of the digital economy and profit levels among different firms. Hence, when the governments and the Commission present low effective tax rates of digital corporations as the heart of the problem, they are conflating the digital economy with the alleged tax rates of a few firms.

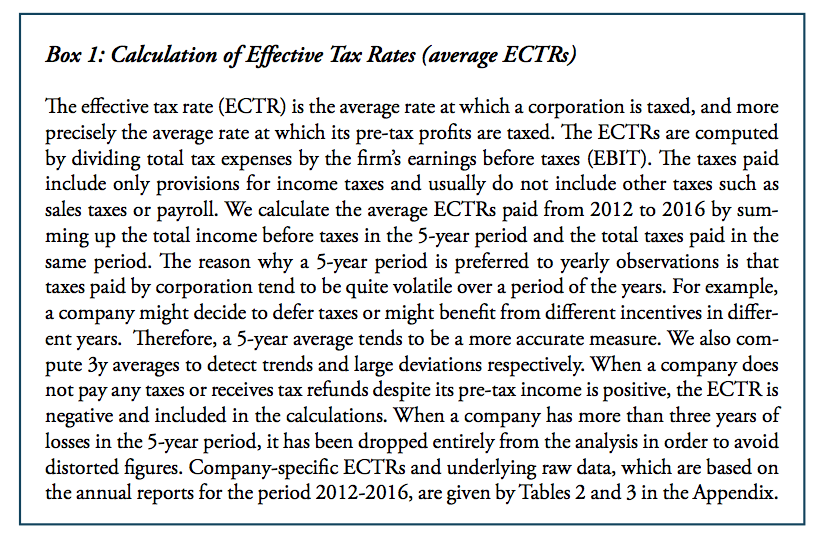

For instance, the above-mentioned Commission Communication selectively uses highly aggregated average data for corporate revenues (top 5 e-commerce retailers) and average corporate tax rates to highlight that companies with “traditional”, less or non-digital, business models face significantly higher tax rates than companies with “digital” business models. According to the references provided by the Commission, the numbers are taken from a ZEW (2016) study that had been commissioned by the European Commission’s DG TAXUD and PWC (2017), which refers to the work done by ZEW. It should be noted, however, that the numbers presented by the Commission for the effective corporate tax rates (ECTR) of digital companies are neither explicitly reported in ZEW (2016) nor depicted in PWC (2017). While the numbers presented may have been calculated on the basis of the ZEW study, it remains unclear how they arrived to their specific estimates on the ECTR. Most notably, real observed data do not correspond with these estimates and, importantly, the ZEW study (2016, p. 9) says that the numbers they have calculated are mere estimates based on a “hypothetical investment project” and a number of theoretical assumptions about pre-tax rates of the return of a hypothetical investment, real interest rates, and different depreciation rates for a limited number of asset classes.

It is also troubling that the evidence presented by the Commission has been estimated on the basis of formal country-specific tax codes. But such estimates on tax do not reflect the real effective corporate tax rates of individual corporations that operate in the EU and outside EU Member States. The fact that the data presented in the Communication are based on individual countries “most favourable tax regulations, that is, including special tax regimes for research, development and innovation” PWC (2017, p. 4), indicates that the Commission did not take into consideration that many internationally-operating companies have to bear the financial burden of double taxation.

[1] The EU’s commercial landscape is characterised by an overall share of highly diverse SMEs which account for of 99.8 percent of all EU enterprises and 66.6 percent of overall EU employment (European Commission 2017b). Despite an overwhelming amount of empirical evidence, the Communication does not say anything about the importance of new digital technologies and digital business models for the empowerment of traditional and new SMEs, as, for example, outlined by the EU’s DG GROW (European Commission 2016) and the EU’s Digital Progress Report (European Commission 2017c).[1] The latter indicates that there are “a lot of technological opportunities still to be exploited by SMEs with big data, cross-border eCommerce, cloud services and automation.” (p. 6) Importantly, a tax on digital companies and/or digital revenues would be passed on to the consumers of such services and, according to basic economics, suppress the demand of these services and their dissemination respectively.

[2] From 2005 to 2016, the overall growth of EU governments’ revenues from taxes on corporate profits slowed down, increasing at a lower rate compared to other forms of taxation. At EU Member State level, lower growth rates in revenues from taxes on corporate income largely resulted from the adverse impact of the economic recessions following the 2007 asset market and sovereign debt crises.

Are there Big Reserves of Untaxed Digital Profits?

The selective use of firms and the obscure way of estimating effective corporate tax rates may however be convenient for the suggestion that traditional businesses pay higher rates than digital businesses. Yet it is also a misleading way to frame problems of international taxation. In fact, it is difficult to find the supporting evidence that digital firms (irrespective of their definition) and their profits are a big reserve of potential tax revenues. Industry data rather reveal that 1) profitability levels are highly diverse among digital firms as well as less digital and non-digital corporations, and that 2) traditional sectors also show a similar variation in profitability and effective tax rates.

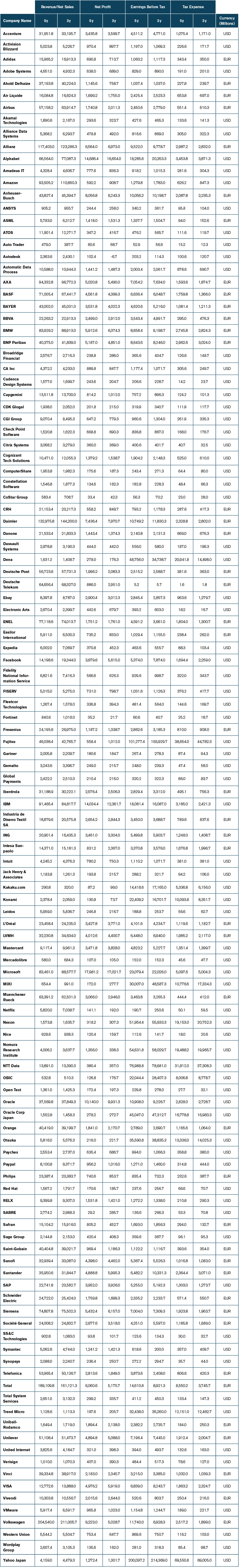

Let us look closer at the actual effective corporate tax rates. In the following, we provide data from the financial statements (profit and loss statements) of 140 publicly listed corporations that operate across borders. We distinguish three groups of corporations:

- Traditional, less digital or non-digital corporations: EuroStoxx50 corporations: 49 corporations (EuroStoxx50 ex SAP) of which 3 companies were non-profitable for the periods under study (5y and 3y)[1]

- Large and well renowned digital corporations: as represented by “The Digital Group” (plus SAP, Oracle and Ebay; ex Spotify due to non-availability of financial statements), 12 corporations of which 2 were non-profitable for the periods under study (5y and 3y)[2]

- Other and less renowned digital corporations: as represented by the MSCI WRLD/SOFTWARE & SERVICES stock market index, 79 corporations of which 10 were non-profitable for the periods under study (5y and 3y)

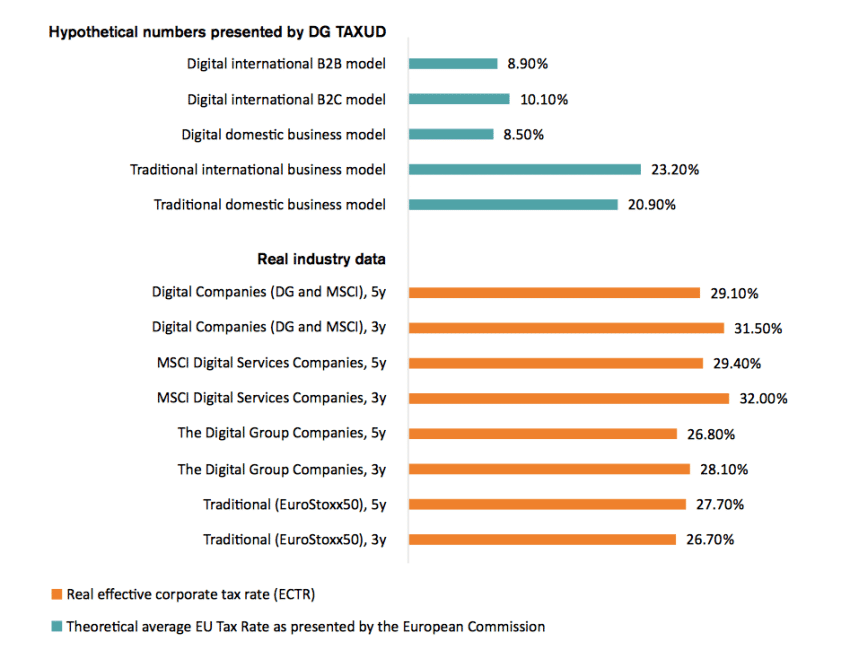

According to the Commission’s Communication, “[o]n average, domestic digitalized business models are subject to an effective tax rate in the EU of only 8.5%”, which is said by the authors to be less than half compared to traditional business models. It is also stated that in the EU, companies with “digital international B2C models” and “digital international B2B models” show average tax rates of 10.1 percent and 8.9 percent. Industry data show that these numbers do not at all reflect the overall tax burden of both traditional and digital corporations that operate in international markets including the EU.

Figure 2 provides the average effective corporate tax rates for less-digital and non-digital corporations (EuroStoxx50 companies) and digital corporations (The Digital Group and MSCI Digital Services companies). The data show that the average effective tax rate of less digital or non-digital corporations was 27.7 percent (5y average) and 26.7 percent (3y average) and was therefore considerably higher (i.e. about 4 to 7 percentage points) than the numbers depicted by the Communication of DG TAXUD for the EU. For digital companies, the gap between the Commission’s hypothetical tax rates and real effective corporate tax rates is much wider: for both well renowned (large) digital companies as well as less renowned digital companies, real effective corporate tax rates are significantly higher. While the Communication argues that the average tax rate for companies with digital international B2B models is only 8.9 percent, the real average corporate tax rates of large (Digital Group) companies and other, less renowned digital (MSCI Digital Services) digital companies were 26.8 percent and 29.4 percent respectively for 5y averages (28.1 percent and 32 percent for 3y averages). In other words, the hypothetical numbers underestimate the effective tax rates of digital companies by about 20 percentage points if average tax rates are taken into consideration.

For digital companies, the gap between the Commission’s hypothetical tax rates and real effective corporate tax rates is much wider: for both well renowned (large) digital companies as well as less renowned digital companies, real effective corporate tax rates are significantly higher. While the Communication argues that the average tax rate for companies with digital international B2B models is only 8.9 percent, the real average corporate tax rates of large (Digital Group) companies and other, less renowned digital (MSCI Digital Services) digital companies were 26.8 percent and 29.4 percent respectively for 5y averages (28.1 percent and 32 percent for 3y averages). In other words, the hypothetical numbers underestimate the effective tax rates of digital companies by about 20 percentage points if average tax rates are taken into consideration.

Figure 2: Effective average tax rates: EU estimates versus real effective corporate tax rates

Source: European Commission (2007a), according to ZEW (2016) and PWC (2017), ECTRs of each individual EU country are based on the “most favourable tax regulations, that is, including special tax regimes for research, development and innovation”; own calculations based on annual reports and the Financial Times’ database. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted gures. “EuroStoxx50” companies do not include Deutsche Bank, E.ON, ENGIE, ENI, and Nokia. “Digital Group” companies do not include Twitter and Salesforce. “MSCI Digital Services” companies do not include Dell, Zillow, Shopify, Splunk Workday, Service- Now, Nuance Communications, Nintendo, DXC Technology, and First Data.

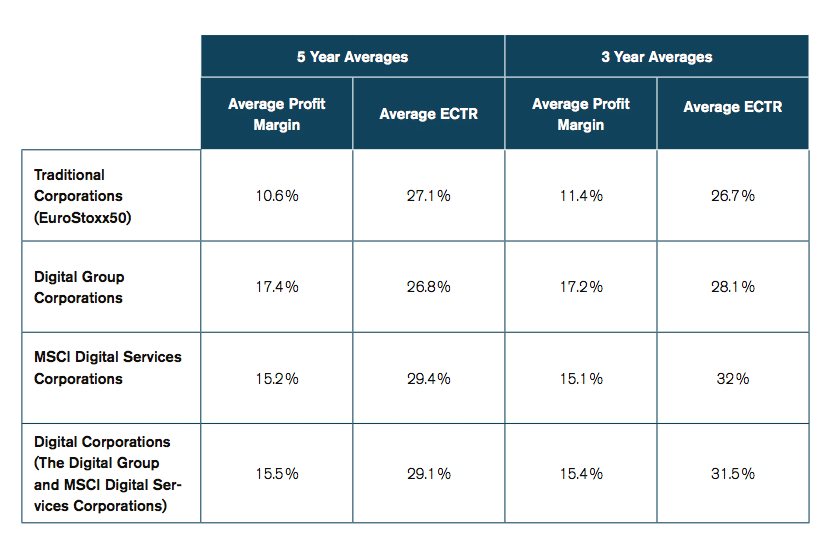

Industry data show that, in the past, digital corporations were on average more profitable than less digital or non-digital corporations. However, the difference is not significant. Even though it is difficult to draw a straight line between digital and non-digital businesses, the data indicate that the profit margins of companies that operate in traditional sectors (as represented Europe’s 50 largest listed and internationally-operating companies) are on average 4.9 percentage points lower compared to digital corporations (Digital Group and MSCI Digital Services corporations; Table 1).[3] It should be noted that differences in profitability would be even lower if loss-making corporations were taken into consideration. In addition, the already small gap in profitability rates declined in the past three years (to 4 percentage points) as a consequence of better world market conditions.

Table 1: Profit margins and effective corporate tax rates (ECTRs), 5y and 3y averages Source: own calculations. EuroStoxx50 corporations: 49 corporations (ex SAP) of which 3 were non-profitable; Digital Group Corporations: 12 corporations of which 2 were non-profitable; MSCI Digital Services corporations: 79 corporations of which 10 were non-profitable. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted figures. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted figures. “EuroStoxx50” companies do not include Deutsche Bank, E.ON, ENGIE, ENI, and Nokia. “Digital Group” companies do not include Twitter and Salesforce. “MSCI Digital services companies” do not include Dell, Zillow, Shopify, Splunk Workday, ServiceNow, Nuance Communications, Nintendo, DXC Technology, and First Data.

Source: own calculations. EuroStoxx50 corporations: 49 corporations (ex SAP) of which 3 were non-profitable; Digital Group Corporations: 12 corporations of which 2 were non-profitable; MSCI Digital Services corporations: 79 corporations of which 10 were non-profitable. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted figures. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted figures. “EuroStoxx50” companies do not include Deutsche Bank, E.ON, ENGIE, ENI, and Nokia. “Digital Group” companies do not include Twitter and Salesforce. “MSCI Digital services companies” do not include Dell, Zillow, Shopify, Splunk Workday, ServiceNow, Nuance Communications, Nintendo, DXC Technology, and First Data.

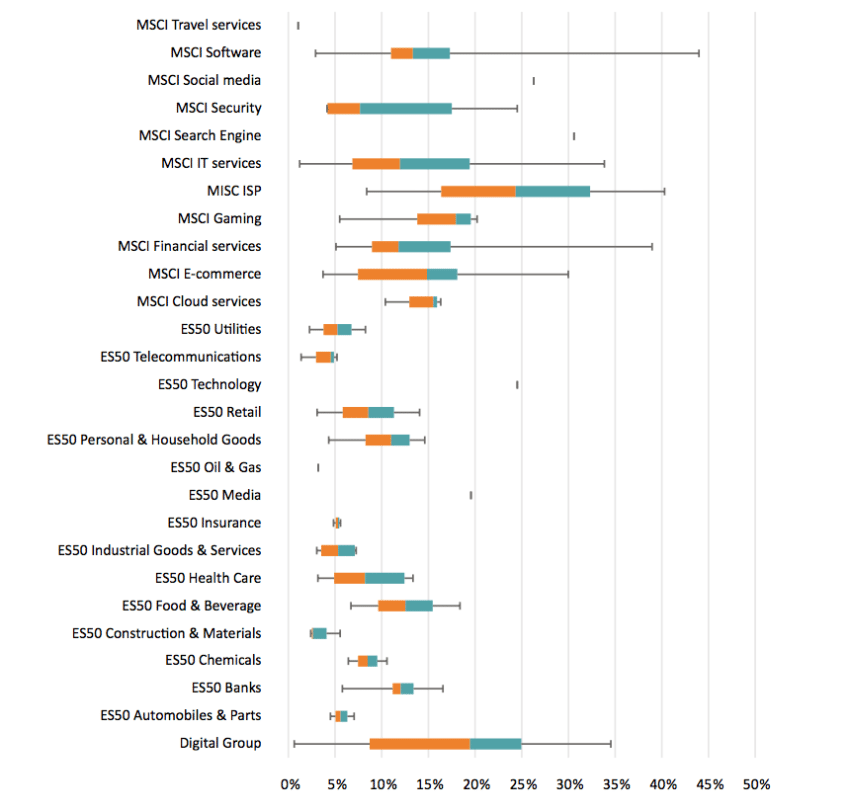

Sectoral perspectives on profit margins

Data for sector- and company-specific profit margins demonstrate that profitability varies substantially for both less digital or non-digital EuroStoxx50 corporations as well as for renowned and less renowned digital corporations (see Figure 3). In market economies, profit margins generally show high levels of heterogeneity across all sectors of the economy. This pattern is confirmed by our sample. Even within the relatively small group of well-renowned Digital Group companies, profit margins vary considerably, ranging from 0.63 percent for Amazon (US) and 2.42 percent for Netflix (US) to 34.54 percent for Ebay (US) (for 5y averages). The average 5y profit margin of 17.4 percent, which is higher than the average profit margin of less renowned digital services companies (MSCI Digital Services), can be explained by few big companies that have achieved relatively high profit margins in the past (e.g. Ebay and Oracle).

At the same time, half of the Digital Group corporations show profit margins that are below the level of 20 percent (SAP, RELX, Expedia, Netflix, and Amazon), while a quarter of all Digital Group corporations show profit margins below the level of 9 percent (Expedia, Netflix and Amazon). It should be noted that the latter number would be higher if Twitter and Salesforce, which have accumulated large losses over the past five years, were included.

A similar pattern is revealed by the data for traditional, less or non-digital companies: profit margins vary substantially across all sectors of the economy. Similar to Digital Group companies, some companies of traditional, less digital sectors show high profit margins: banks (up to 16.56 percent, the sample’s maximum value for banks), media companies (19.56 percent) technology suppliers (up to 24.52 percent), food and beverages companies (up to 18.38 percent), and personal and household goods companies (up to 14.61 percent). Furthermore, the business models of these high profitability companies generally allow for the application of legal intra-company transfer pricing models, e.g. intra-company financing and production prices, licensing of patents and brands, and licensed production, to optimise corporate production, marketing, risk and tax structures.

The data also show that profit margins vary considerably for all digital sub-sectors represented by the MSCI Digital Services Index. The average profit margins appear to be relatively high for some sectors due to the limited number of corporations in MSCI Digital Services’ sub-sectors. For Internet Services Providers (ISPs), i.e. for some sectors the picture is somewhat distorted. For example, the average 5y profit margin for two companies, United Internet (US) and Verisign (US), is 24.29 percent. The two companies show, however, highly different profit margins, i.e. 40.3 percent for Verisign and 8.27 percent for United Internet. Similarly, for the search engine sector there is only one corporation in the MSCI index, i.e. Yahoo, with an average 5y profit margin of 30.59 percent. For the social media sector, there is also only one corporation in the MSCI Digital Services, i.e. MIXI with an average 5y profit margin of 26.28 percent.

The lesser known digital services companies also show a high variation of profit margins. The software industry is a case in point. For the 19 software providers covered by the MSCI digital services index (excluding loss-making companies), the average profit margin is 14.5 percent, ranging from 2.92 percent (ATOS; France) to 20.35 percent (CA Technologies; US) and 43.98 percent (Check Point Software Technologies; Israel). By comparison, SAP (Germany), shows an average 5y profit margin of 17.38 percent. The average profit margin goes down to 12.6 percent if the 6 loss-making software providers are taken into account, i.e. Splunk and Nuance Communication with profit margins of -35.76 percent and -2 percent respectively.

Real-world corporate finance data also show that many digital corporations are not profitable, i.e. they have accumulated a series of annual losses in the past. Two large “Digital Group Companies”, Twitter (US) and Salesforce (US), show negative 5y average profit margins of -31.79 percent and -3.85 percent respectively (-25.29 percent and -3.37 percent for 3y averages respectively). Similarly, many less renowned companies, as represented in the MSCI Digital Services Index show negative profit margins: Zillow (US; -19.64 percent), Shopify (France; -10.81 percent), Splunk Workday (France; -35.76 percent), ServiceNow (US; -25.08 percent), Nuance Communications (US; -1.99 percent), Nintendo (Japan; -0.72 percent), DXC Technologies (US; -5.64 percent), and First Data (US; -5.55 percent) show high corporate losses and negative profit margins respectively.

Policymakers should take into account that scale is an important driver of the profitability of many B2B and B2C digital business models, particularly in e-commerce and in the provision of platform-based digital services. Generally, companies can focus on growing revenues at the expense of margins, or margins at the expense of revenues. Indeed, many digital companies invest in long-tail value drivers to increase and sustain revenues and, after all, to make profits. These include investments in IT and software technology, advertising and product diversification to increase customer value-added and, in turn, subscription and membership numbers. These types of investment explain often low or negative profit margins of both big and small digital companies.

It should also be noted that there is a high number of privately held companies (like Uber and Spotify) that are loss making, but where public financial data is unavailable. By taking only the largest digital companies by market capitalisation, the authors of the European Commission’s Communication create a highly distorted picture, as in many cases the largest companies by market capitalisation (high stock prices times the number of stocks outstanding) and most successful companies are profitable.

Figure 3: Distribution of profit margins for digital and less or non-digital companies, by sector, 5y averages for 2012-2016

Note: own calculations based on annual reports and financial statements, supplemented by data collected by the Financial Times’ database. MSCI = MSCI Digital Services. ES50 = EuroStoxx50. The box-plot represents maximum value, 75 percent quartile, median, 25 percent quartile and minimum value. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted figures. “EuroStoxx50” companies do not include Deutsche Bank, E.ON, ENGIE, ENI, Nokia, and Unibail Rodamco. “Digital Group” companies do not include Twitter and Salesforce. “MSCI Digital services companies” do not include Dell, Zillow, Shopify, Splunk Workday, ServiceNow, Nuance Communications, Nintendo, DXC Technology, and First Data.

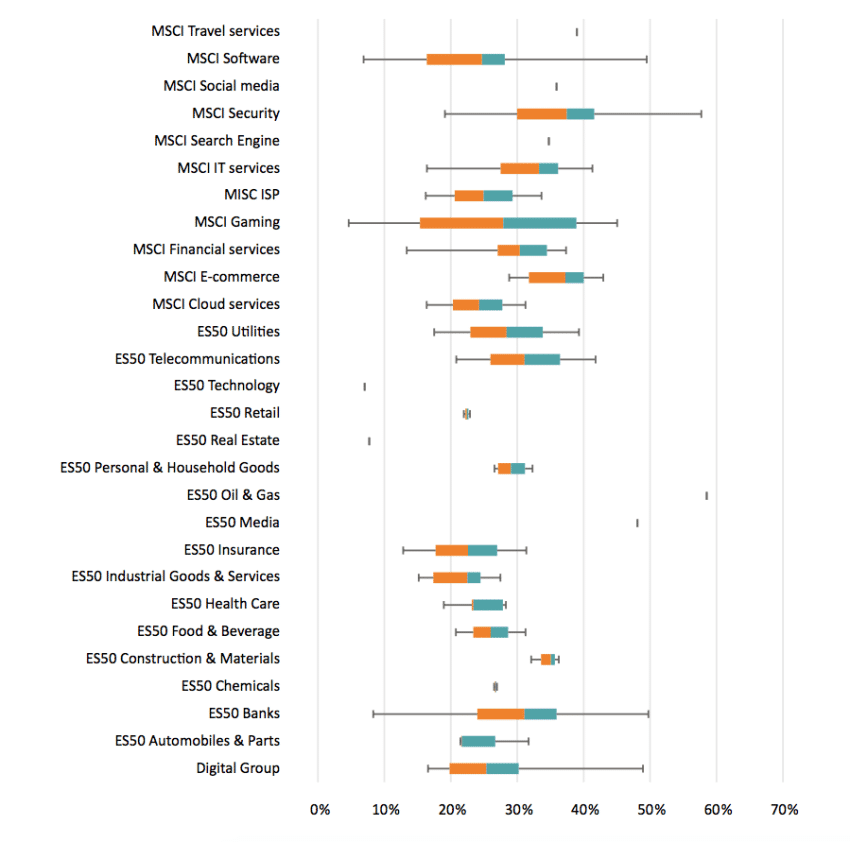

Sectoral perspectives on effective corporate tax Rates (ECTRs)

Corporate data demonstrate that ECTRs also vary substantially for both traditional, less digital or non-digital EuroStoxx50 corporations and digital corporations (see Figure 4). Companies’ average ECTRs show high levels of variation between different industries and within sub-sectors, depending on the nature of applied business models, the residence of firms, and whether companies are exposed to double taxation.

“Digital Group” corporations are characterised by distinct differences in ECTRs, which range from 16.57 percent (RELX; UK) and Alphabet (18.89 percent; US) to 26.29 percent (Netflix), 33.87 percent (Ebay; US) and even 48.93 percent (Amazon; US). Some companies with low profit margins are among those with the highest ECTRs (i.e. Amazon with a profit margin of 0.63 percent and Netflix with a profit margin of 2.42 percent).

At the same time, many traditional corporations show relatively low ECTRs, with rates going below 20 percent (5y averages) in the food and beverage sector, the automobile and parts sector, the telecommunications sector, the utilities sector, the industrial goods and services sector, and the banking sector.

ECTRs also vary substantially for MSCI Digital Services Sectors. In the software sector, which includes 18 corporations, ECTRs range from 6.87 percent (Cadence Design Systems; US) and 10.16 percent (Citrix; US) to 34.97 percent (CDK Global; US), 37.25 percent (Oracle Corp. Japan; Japan) and even 49.49 percent (Autodesk; US). Very high ECTRs can be found in many other sectors such as digital travel services (SABRE, US; 38.99 percent), cloud computing services (Akamai Technologies; US; 31.24 percent) and digital security services (Symantec; US; 57.71 percent).

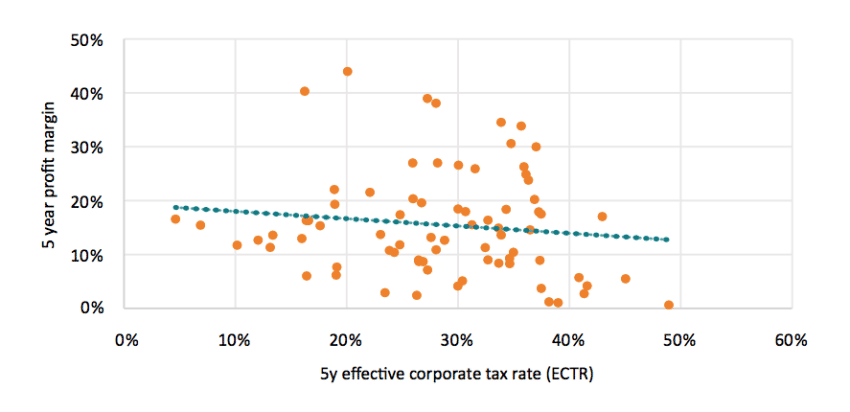

The data show that the average ECTRs of some digital companies, which operate in B2B and B2C markets, exceed the European Commission’s hypothetical estimates for the EU by about 20 to 50 percentage points. In addition, while the Commission’s Communication merely points to revenue growth numbers and the growth in the market capitalization levels of a few big companies to make a case for a digital tax, the profit and tax data for digital companies do not even show a correlation between the profitability and the level of ECTRs (Figure 5): both low and high profitability companies show high ECTRs and vice versa. For our sample of digital companies, there is a slightly negative correlation (correlation coefficient: -0.13), pointing to the fact that many low profitability companies show higher effective corporate tax rates compared to high profitability companies.

Figure 4: Distribution of effective corporate tax rates for EuroStoxx50 corporations and companies largely providing digital services, by industrial sector, 5y averages

Note: own calculations based on annual reports and financial statements, supplemented by data collected by the Financial Times’ database. MSCI = MSCI Digital Services. ES50 = EuroStoxx50. The box-plot represents maximum value, 75 percent quartile, median, 25 percent quartile and minimum value. Real industry data do not include loss-making companies: when a company has more than three years of losses in the 5-year period, it has been dropped from the analysis in order to avoid distorted figures. “EuroStoxx50” companies do not include Deutsche Bank, E.ON, ENGIE, ENI, and Nokia. “Digital Group” companies do not include Twitter and Salesforce. “MSCI Digital services companies” do not include Autodesk, Dell, Zillow, Shopify, Splunk Workday, ServiceNow, Symantec, Nuance Communications, Nintendo, DXC Technology, and First Data.

Figure 5: Correlation between profit margins and effective corporate tax rates, digital companies, 5y averages 2012-2016

Note: own calculations based on annual reports and financial statements, supplemented by data collected by the Financial Times’ database. Companies include “Digital Group” and “MSCI Digital Services” companies. Data do not include loss-making companies.

In sum, real-world corporate ECTRs reveal that digital corporations do not differ from less digital or non-digital corporations. The data also reveal that many traditional corporations actually show comparatively low effective corporate tax rates. As a result, real-world data for effective corporate tax rates demonstrate that there is no systematic difference in income taxes paid by digital corporations compared to their traditional peers. Therefore, the underlying proposition in the discussion about taxing digital firms is misguided: digital corporations’ effective tax rates do not systematically differ from those of traditional firms, whereby the highest effective tax rates are actually found for digital companies – and not, as assumed, for traditional “bricks-and-mortar” companies.

[1] SAP has been assigned to “The Digital Group” corporations.

[2] Corporations represented by “The Digital Group” include Amazon.com, Inc.; Expedia, Inc.; Google, Inc.; Facebook, Inc.; Netflix, Inc.; Microsoft Corporation; RELX Group PLC.; Salesforce.com Inc.; Spotify AB, and Twitter, Inc.). We also included three other large digital companies that are frequently covered by media commentary: SAP, Oracle and Ebay.

[3] MSCI Digital Services sectors include: travel services, telecommunications, software services, digital security services, cloud computing services, e-commerce services, financial and payment services, Internet service providers, and general IT services.

Conclusions

There is a good case to make for fair taxation and that uneven effective tax rates can distort competition and lead to smaller tax revenues. However, those that are calling for higher taxes on one particular group of firms – digital corporations – have yet to present the evidence for why that is motivated by principles of tax fairness. The selective focus on the world’s “top 100 companies by market capitalisation” and the world’s “top 5 e-commerce companies” does not reflect the reality of the international business landscape, and therefore conveys a misleading picture about European and international companies’ profit margins and effective corporate tax rates. Past and recent financial data reveal that profitability levels are highly diverse for digital, less digital and non-digital corporations. Real world data also demonstrate that traditional sectors have a great number of highly profitable traditional corporations. At the same time, it is digital companies that show the highest effective corporate tax rates – not traditional companies. Moreover, real-world data for effective corporate tax rates suggest that there is no systematic difference in income taxes paid by digital corporations compared to their traditional peers.

In sum, recent proposals in Europe to slap a targeted tax on digital revenues clash with the EU’s top policy priorities for the digital economy. It is therefore remarkable that such taxes even are considered. A tax on digital revenues would not only stand in opposition to tax efficiency and neutrality; it would also undermine digitalisation, European integration, and the Digital Single Market.

Like other taxes, the impact of a “digital tax” on the revenues of digital corporations would feedback to less digital business activities in the EU and elsewhere, thereby affecting employment and tax revenues on digitally-enabled corporations like SMEs as well as taxes on personal incomes generated in both the EU’s digital and less digital industries. It should be assumed that other countries would respond in kind, putting at risk EU businesses that already operate globally or currently grow and expand to commercially succeed globally.

References

Eurogroup (2017), Political Statement regarding the ‘Joint Initiative on the Taxation of Companies Operating in the Digital Economy’, 18 September 2017.

European Commission (2017a), A Fair and Efficient Tax System in the European Union for the Digital Single Market, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Brussels, 21 September 2017.

European Commission (2017b), Annual Report on European SMEs 2016/2017, November 2017.

European Commission (2017c), Integration of Digital Technology: Europe’s Digital Progress Report 2017, April 2017.

European Commission (2016), Fostering SMEs growth through digital transformation, a Guidebook for Regional and National Authorities, November 2016.

European Commission (2015), Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe, 6 May 2015.

European Council (2017), Council conclusions on ‘Responding to the challenges of taxation of profits of the digital economy’, Brussels, 30 November 2017.

G20 (2017), G20 Digital Economy Ministerial Declaration, Shaping Digitalisation for an Interconnected World, Dusseldorf, 6 – 7 APRIL 2017.

OECD (2017a), Tax Challenges of Digitalisation, the Request for Input – Part I, 25 October 2017.

OECD (2017b), Tax Challenges of Digitalisation, the Request for Input – Part II, 25 October 2017.

OECD (2016), World must act faster to harness potential of the digital economy, available at http://www.oecd.org/internet/world-must-act-faster-to-harness-potential-of-the-digital-economy.htm, accessed on 29 January 2018.

OECD (2015), Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, Action 1: 2015 Final Report.

OECD (2014), DEPS Action 1: Address the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, 24 March 2014 – 14 April 2014.

PWC (2017), Digital Tax Index 2017: Locational Tax Attractiveness for Digital Business Models, research bases on a joint analysis of PwC and the University of Mannheim and the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW).

Sondierungspapier (2018), Ergebnisse der Sondierungsgespräche von CDU, CSU und SPD Finale Fassung, 12 January 2018.

ZEW (2016), The Impact of Tax Planning on Forward-Looking Effective Tax Rates, Working Paper No. 64 – 2016, Centre for European Economic Research.

Appendix

Figure 6: Development of EU government tax receipts as percent of GDP

Source: Eurostat, OECD. Note: for total receipts from taxes and compulsory social contributions, the 1995 value is depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts, the 1995 value is depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts from VAT, the 1995 value is depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts from individual and household income, numbers are depicted for EU28 ex Germany, Estonia, Spain, Croatia, Hungary, Poland. For total tax receipts from corporate profits, numbers EU28 ex Spain, Croatia, Hungary. For total tax receipts from corporate profits, 1995 and 2005 numbers for Germany and Estonia based OECD data.

Source: Eurostat, OECD. Note: for total receipts from taxes and compulsory social contributions, the 1995 value is depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts, the 1995 value is depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts from VAT, the 1995 value is depicted for EU28 ex Croatia. For total tax receipts from individual and household income, numbers are depicted for EU28 ex Germany, Estonia, Spain, Croatia, Hungary, Poland. For total tax receipts from corporate profits, numbers EU28 ex Spain, Croatia, Hungary. For total tax receipts from corporate profits, 1995 and 2005 numbers for Germany and Estonia based OECD data.

Figure 7: Share of total tax expenses of the world’s largest digital corporations” in total EU tax receipts and total EU tax receipts from corporate income, based on 5y averages (2012-2016) Note: own calculations based on Eurostat and OECD data, annual reports and financial statements, supplemented by data collected by the Financial Times’ database.

Note: own calculations based on Eurostat and OECD data, annual reports and financial statements, supplemented by data collected by the Financial Times’ database.

Table 2: ECTRs and pro t margins, by company, 5y and 3y