What About Us? Consumer Response to the Digital Markets Act

Published By: Matthias Bauer Dyuti Pandya

Research Areas: Digital Economy European Union

Summary

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) was introduced as a landmark piece of EU legislation to change how consumers interact or engage with large online platforms. By restraining the power of the so-called gatekeepers, Brussels aimed to promote greater competition, improve privacy protections and make digital services more affordable. Two years into its application, however, the reality on the ground in EU, especially for the Central and Eastern European (CEE) Member States has proved far more sobering. Consumers have seen little evidence of cheaper or improved digital services. Many report greater friction in their online experience, while confidence and trust in platform privacy remains low.

Most strikingly, consumer behaviour itself has hardly shifted: reliance on a handful of dominant players such as Google, Meta, and Apple still prevail. These findings suggest that the DMA, while ambitious in scope, has failed to deliver on its central promise of empowering Europe’s digital citizens. This study concludes that Europe must either consider replacing the DMA with a more flexible case-by-case enforcement or, at the very least, reform it by removing obligations that neither enhance consumer welfare nor improve market contestability.

Objective, Methodology, and Coverage

The primary aim of this study was to assess the lived experiences of consumers under the DMA, moving beyond policy theory and legal design to examine how end-users actually perceive and respond to regulatory changes. This study analyses data from a large-scale regional survey conducted by Ipsos in July 2025 and commissioned by EPPP. The analysis and interpretations presented in this paper are solely those of ECIPE and EPPP authors, and do not represent the views of Ipsos. A total of 3,500 consumers were interviewed across seven CEE countries – Slovakia, Czechia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania, with 500 respondents in each market. The survey instrument was designed as a structured online questionnaire, using quotas for age, gender, and region to ensure national representativeness of the online adult population. In contrast to previous EU-wide surveys, this study deliberately focuses on a region where digital adoption is high but regulatory awareness is relatively low, providing a reality check on how regulation plays out in practice in newer Member States.

Key Paradoxes and Numbers

The Regulation Paradox

- 55 per cent of respondents favour strong rules for digital platforms, even if this slows the rollout of new features.

- Yet 39 per cent report needing more steps to complete tasks that were once simple.

- Around one-third find their digital experiences less seamless and more confusing since DMA-related changes.

The Privacy Paradox

- 55 per cent say they are more concerned about online privacy today.

- Still, 60–69 per cent continue accepting extensive data collection in exchange for free services.

- Only a single-digit minority are willing to pay for ad-free or privacy-enhanced subscriptions (e.g. Meta’s paid plan).

- Privacy, in practice, has become a premium product rather than a universal safeguard.

The Contestability Paradox

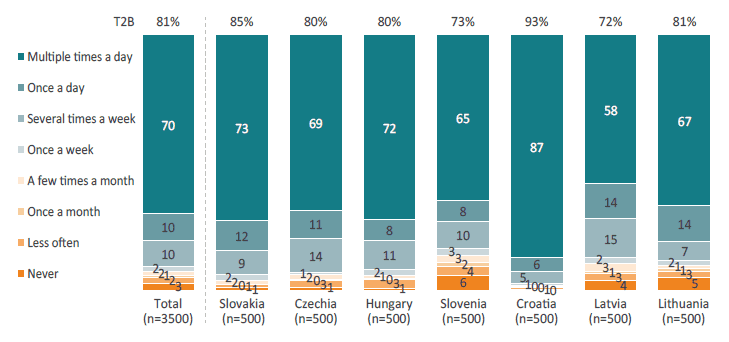

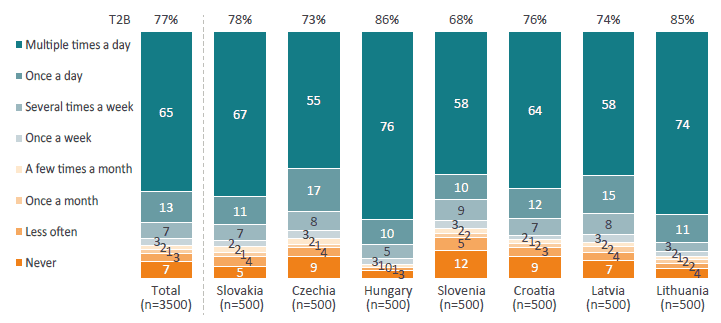

- 70 per cent of users rely on Google Search multiple times per day.

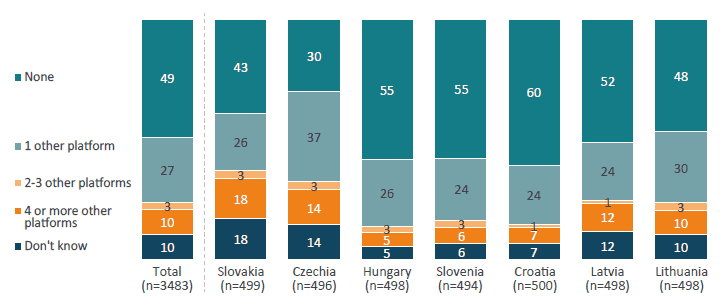

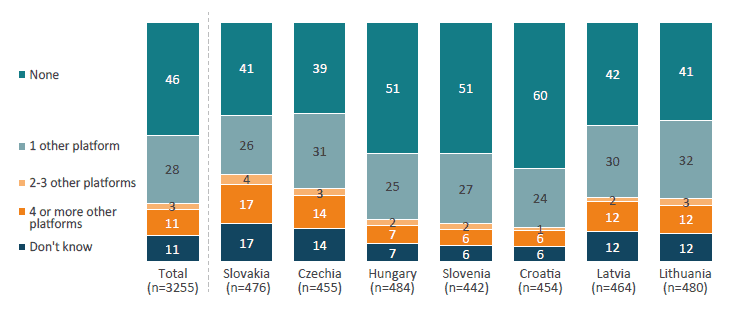

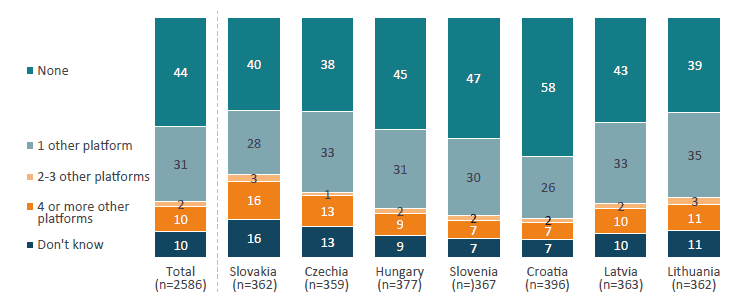

- More than 75 per cent use Facebook daily, and nearly half use no alternatives to Google or Meta services at all.

- For professional networking, LinkedIn dominates even more strongly – over 60 per cent of consumers use it exclusively.

The Awareness Gap

- 80 per cent of consumers are unfamiliar with the DMA.

- Many cannot connect observed changes in their digital services to the regulation itself.

Major Conclusions

These results highlight a fundamental misalignment between the European Commission’s ambitions and consumer realities. Promised gains in affordability have not materialised; instead, some measures have made services more cumbersome or less user-friendly. Privacy protections, far from empowering consumers, have often been monetised in ways that exclude the majority unwilling to pay.

Contestability, the cornerstone of the DMA, remains an aspiration rather than an observable reality, as network effects and ingrained habits keep consumers locked into dominant platforms. The law, in its current form, risks imposing costs without securing benefits: consumers tolerate more friction and fewer integrated features while still failing to see meaningful alternatives. If this trajectory continues, Europe risks repeating the mistakes of previous technology cycles, where regulation designed with good intentions inadvertently slowed innovation and limited consumer choice.

Policy Recommendations

Two clear paths forward emerge from this study.

- Option 1 is the ideal scenario: Repealing the DMA entirely and return to case-by-case competition enforcement, rooted in evidence and consumer welfare principles. This approach would eliminate blanket ex-ante rules that assume harm before it occurs, prevent rushed compliance measures that degrade service quality, and restore flexibility to adapt regulation to actual market outcomes. Enforcement could then focus on demonstrable harms, with remedies applied proportionately and transparently across all players.

- Option 2 is a second-best solution: targeted reform. Under this option, obligations that do not demonstrably enhance consumer welfare should be repealed or suspended. Rules such as interoperability (Article 7), marketplace access (Article 6(4)), and the prohibition on self-preferencing (Article 6(5)) should only be enforced if strong safeguards are in place for privacy, cybersecurity, product integrity, and liability. In practice, prohibiting self-preferencing has removed integrated features valued by consumers while delivering little measurable benefit to competition. Where neutrality mandates reduce service quality or convenience without creating viable alternatives, they should be suspended pending further impact assessment. Similarly, measures such as choice screens should be reconsidered where they merely add inconvenience without generating meaningful switching. Both options share a common goal: to reorient digital regulation towards what consumers actually value, affordable services, smooth functionality, safety, and genuine competitive choice, and away from measures that look promising on paper but fail in practice.

This paper was produced with support from our industry partners, who neither influence nor have veto power over our findings. We do not represent their individual positions and remain committed to our principles, even when they diverge.

1. Introduction

Passed in autumn 2022 and applicable since spring 2023, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) has been reshaping the way consumers interact with the most popular online platforms for more than two years. It is now an appropriate time to assess the extent to which this landmark legislation has fulfilled the European Commission’s stated objectives: promoting open and fair digital markets by enhancing consumer choice, strengthening data ownership rights, enabling seamless portability, facilitating streamlined access, and ensuring unbiased search results (Vestager, 2024).

To that end, this study analyses data from a large-scale regional survey of 3,500 consumers across seven CEE countries: Slovakia, Czechia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The survey was conducted by Ipsos and commissioned by EPPP. The analysis and interpretations presented in this paper are solely those of ECIPE and EPPP authors, and do not represent the views of Ipsos. The study provides a comprehensive snapshot of consumer experiences under the DMA, focusing on lived realities rather than abstract attitudes toward “big tech” or EU institutions. Importantly, it represents a significant contribution to the discourse on consumer experiences with the regulation, augmenting publications such as the report Impact of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) on Consumers across the European Union: Results from a Survey with 5,000 Consumers published by the Nextrade Group.[1]

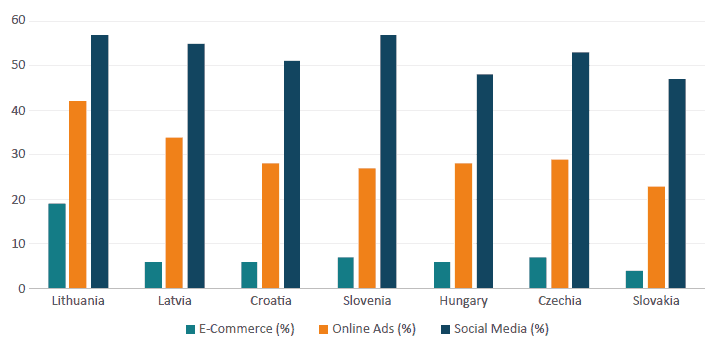

Before turning to the detailed survey evidence that captures how consumers interact with the DMA, it is useful to situate the discussion more broadly and highlight that the regulation also directly affects businesses. As shown in Figure 1, business use of digital platforms in Central and Eastern Europe varies across countries and across platform types. In Lithuania, for example, 19 per cent of firms derive at least 10 per cent of their online sales from e-commerce marketplaces, whereas in Slovakia the figure is only 4 per cent. Online advertising penetration ranges from 23 per cent in Slovakia to 42 per cent in Lithuania. By contrast, the use of social media for business purposes is consistently the most widespread, with between 47 per cent (Slovakia) and 57 per cent (Lithuania, Slovenia) of companies engaging on these platforms.

This snapshot underscores a key point: the DMA matters not only for consumers but also for enterprises. Crucially, its impact depends on whether it changes platform behaviour in ways that expand or restrict business opportunities. For smaller firms in particular, the ability to advertise effectively online, build visibility through social media, and access fairer conditions in e-commerce marketplaces may directly shape their competitiveness. The regulation’s consumer-facing provisions must therefore be understood alongside its broader implications for business adoption and innovation in the region.

Figure 1: Percentage of companies using digital platforms in selected jurisdictions

Source: Eurostat – ICT usage in enterprises, (2024) cited in Cenamo et. al (2025) Economic Impact of the Digital Markets Act on European Businesses and the European Economy, Available at: https://www.dmcforum.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/120625-FINAL-CCIA-DMA-Report-1.pdf

Nonetheless, the principal aim of this paper is to present the lived experiences of consumers following the implementation of the DMA and to highlight the key findings of the survey. These findings reveal, in particular, a widespread lack of public awareness of the regulation, limited evidence that it has improved the quality of online services for consumers, enhanced consumer security, or strengthened consumer rights, and a shortfall in creating more contestable markets that provide greater opportunities for smaller businesses.

To contextualise this analysis, the paper first provides an overview of the regulation’s core provisions, with particular attention to the obligations imposed on designated “gatekeepers” in the technology sector. It then outlines the European Commission’s stated commitments to consumers, clarifying the priorities and expectations that underpin the regulation. Together, these elements form the basis for the subsequent analysis, which assesses how these commitments correspond with the actual experiences of consumers in CEE. The paper also sets out the survey methodology to establish a foundation for the analytical chapter, which presents and interprets the survey results. Finally, drawing on both the findings and relevant academic debate, the paper concludes by offering policy recommendations.

1.1 Contextualising the Digital Markets Act

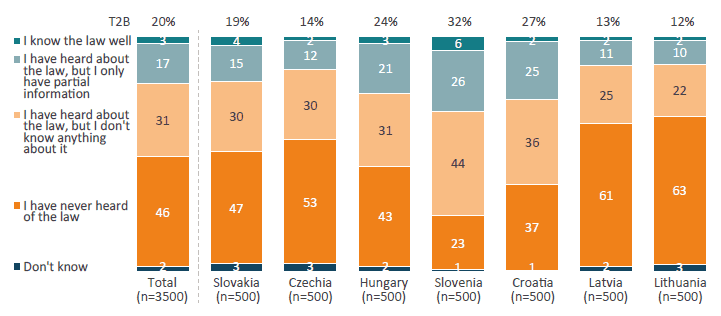

While the European Commission has consistently framed the DMA as a landmark regulation poised to transform digital markets, consumer awareness of the law remains strikingly low. The Ipsos survey on consumer responses to the DMA found that in some countries up to 85 per cent of respondents had either never heard of the law or possessed little substantive knowledge of its provisions. This highlights a disconnect between the regulatory objectives set by policymakers and the actual experiences of consumers, for whom the law remains largely abstract and its effects only partially observable. The limited visibility of tangible changes in daily online interactions suggests that the DMA’s impact, though potentially significant in structural terms, has not translated into a clear narrative for ordinary users.

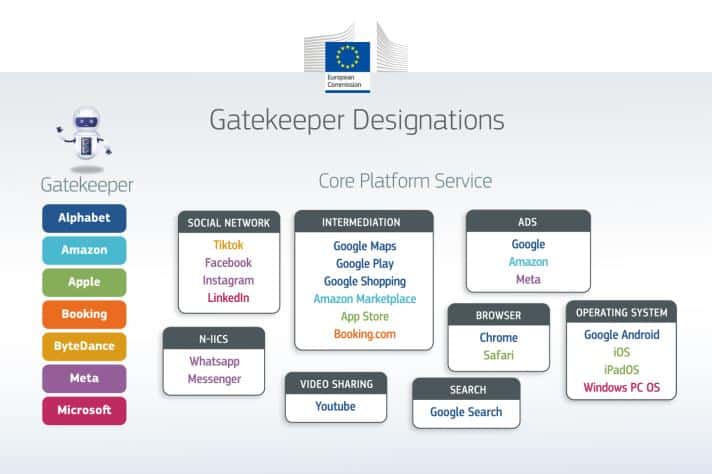

Before examining the survey findings in greater detail, it is useful to outline the objectives and scope of the DMA. The regulation targets large digital platforms designated as “gatekeepers” due to their entrenched market positions and substantial impact on the internal market. Specifically, the DMA defines gatekeepers as platforms providing any of a pre-defined set of digital services ‘core platform services’ (see Figure 2), such as online search engines, app stores, web browsers, messenger services or operating systems (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 3(1)). The European Commission has designated seven gatekeepers under the DMA: Google, Amazon, Apple (including iPadOS), ByteDance (TikTok), Meta, Microsoft, and Booking.com. However, on 23 April 2025, Meta was undesignated with respect to its online intermediation service, Facebook Marketplace. In total, 23 core platform services provided by these gatekeepers are currently subject to the DMA (European Commission, 2025b). The gatekeepers are required to comply with a set of obligations designed to govern their day-to-day operations. The primary aim of these obligations is to prevent unfair practices and to foster a more competitive and contestable digital market, thereby creating a level playing field for other (smaller) businesses and ensuring that consumers benefit from enhanced choice, security, and transparency (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022).

Figure 2 Gatekeeper Designations under the Digital Markets Act (DMA)

Source: European Commission (2025), Gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act. Available at: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/gatekeepers_en

1.2 Principal Measures under the Digital Markets Act

1.2.1 Article 5(4) – Ensuring Free Promotion

The DMA requires gatekeepers to allow business users to promote their offers directly to consumers without additional charges. As the regulation states: “The gatekeeper shall allow business users, free of charge, to communicate and promote offers … to end users acquired via its core platform service or through other channels, and to conclude contracts with those end users…” (Regulation (EU) 2022/1925, 2022, Article 5(4)). For example, under this rule, Apple must let developers inform users about cheaper prices, discounts, or subscriptions on their own websites, permit links or buttons in apps for direct purchases outside the App Store and allow developers to complete sales or contracts through these alternative channels. This provision aims to reduce dependence on gatekeeper-controlled advertising systems and enhance commercial freedom for businesses. Ensuring access to third-party applications.

1.2.2 Article 5(5) – Ensuring Access to Third-Party Applications

Furthermore, end users must be able to access and use content or subscriptions through applications provided by business users, even if this means bypassing the gatekeeper’s own platform. According to the DMA: “[Gatekeepers must] allow end users to access and use … content, subscriptions, features or other items, by using the software application of a business user … without using the core platform services of the gatekeeper” (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 5(5)). In practice, Apple, as a gatekeeper, cannot stop Spotify users from subscribing directly through the Spotify app on iPhones without using Apple’s payment system. The DMA requires Apple to let apps offer alternative payment options and links, so users can bypass Apple’s fees, in line with Article 5(5) (Spotify, 2024). Simply put, this provision ensures that end users have direct access to services and content without unnecessary gatekeeper restrictions.

1.2.3 Article 5(8) – Preventing Tying of Services

The DMA addresses the practice of tying, whereby access to one core platform service is made conditional on the use of another. It specifies: “The gatekeeper shall not require business users or end users to subscribe to … any further core platform services … as a condition for being able to use … any of that gatekeeper’s core platform services” (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 5 (8)). Microsoft, as a gatekeeper through its Windows operating system, previously bundled access to Microsoft Teams or OneDrive with Windows, effectively requiring users to subscribe to or use these additional services to get the full experience of the OS. Under the DMA (Article 5(8)), Microsoft cannot force business users or end users to use or subscribe to its other core services as a condition for accessing Windows (Chan, 2025). This provision strengthens user autonomy and protects business users from being compelled to expand their reliance on gatekeeper ecosystems.

1.2.4 Article 6 – Preventing Self-Preferencing of Gatekeepers

The DMA empowers the European Commission to impose additional obligations on gatekeepers to prevent self-preferencing, and thus, ensure fair competition. It specifically targets practices where gatekeepers might favour their own products or services over those of competitors and allows the Commission to require transparency and equal treatment for business users (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 6). For instance, the Commission recently stated that Google breached this article by giving its own services such as shopping, travel, finance and sports information preferential placement in search results over equivalent services offered by competitors (European Commission, 2025c).

1.2.5 Article 7 – Ensuring Interoperability of Digital Services

The DMA also acknowledges the need for interoperability, particularly for messaging services, to enhance user choice and competition. As the DMA states: “Gatekeepers shall allow end users of their core platform services to interoperate with users of third-party software applications” (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 7). Before the DMA, WhatsApp users could not message Telegram users, reinforcing platform dominance. The DMA now requires gatekeepers’ messaging services to provide interfaces for horizontal interoperability, which allows users on different platforms to communicate seamlessly (Rombola, 2023). This provision aims to prevent market fragmentation and ensure that consumers are not locked into a single platform, thereby again, promoting contestable and fair digital market.

1.2.6 Articles 20, 28, 30, 31 – Ensuring Enforcement and Compliance

The DMA establishes compliance and enforcement mechanisms to ensure gatekeepers adhere to their obligations. Under Article 28, gatekeepers are required to “introduce a compliance function, which is independent … composed of one or more compliance officers” (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 28). The Commission is empowered to enforce the DMA through a range of measures, including opening proceedings (Article 20), imposing fines of up to 10 per cent of global turnover (Article 30), and issuing periodic penalty payments for repeated non-compliance (Article 31). These provisions strengthen regulatory oversight and promote accountability in digital markets.

[1] This report is based on a survey of 5,000 consumers across 20 EU Member States conducted from 28 April to 15 May 2025 by the Nextrade Group via the online platform Pollfish. The online methodology enabled faster data collection and broader coverage compared to traditional approaches such as computer assisted telephone interviews or face to face interviews. Respondents participated directly from their devices, and quality control measures including attention checks and fingerprinting to prevent duplicates ensured reliable data. Sample sizes ranged from 200 per country to 350 to 400 in the largest markets including France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania and Spain. Most participants earn under EUR 40,000 annually, with 44 per cent living in cities of 300,000 or more inhabitants. The sample is highly educated, with 62 per cent holding vocational or university degrees and 33 per cent having a Masters degree or higher.

2. European Commission's Promises towards Consumers under the DMA

This section presents the European Commission’s stated commitments to consumers, clarifying the priorities and expectations that underpin the regulation. These “promises” form the basis for the subsequent analysis, in which the study assesses how well they correspond with the actual experiences of consumers in CEE, as captured by the Ipsos survey.

2.1 Promoting Better and More Affordable Services

Throughout the drafting of the DMA, the European Commission has consistently emphasised that promoting fair competition in digital markets is essential for enhancing consumer welfare. By fostering a more transparent and contestable market, the DMA is intended to empower consumers and create conditions that benefit end users directly. As noted previously, the regulation is designed to give consumers access to a broader range of services and to facilitate switching between providers. At the same time, its measures aim to lower barriers to entry and promote a level playing field, enabling smaller and emerging businesses to compete effectively alongside dominant platforms (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022).

The DMA explicitly regulates the conduct of gatekeepers to ensure fair competition. It prohibits them from restricting business users who wish to offer the same products or services through alternative channels (whether via third-party intermediation services or their own direct sales platforms) at prices or under conditions different from those applied by the gatekeeper (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 5(3)). By establishing this principle, the regulation seeks to prevent anti-competitive pricing practices, enhance market transparency and enable business users to compete on both price and service quality.

These measures are intended to deliver tangible benefits to consumers, including more affordable and accessible digital services. The European Commission’s 2020 impact assessment illustrated the potential scale of these benefits, estimating that improved contestability of core platform services could generate a consumer surplus of approximately EUR 13 billion (European Commission, 2020, p. 61). This underscored the potential substantial gains for consumers if competition in digital markets was effectively enhanced.

2.2 Promoting More Secure and Private Services

The European Commission has placed significant emphasis on enhancing the privacy and rights of consumers in digital markets. This focus is reflected in a number of key provisions within the DMA that aim to protect end users while promoting fair competition. For example, as previously stated in the “Principal Measures under the Digital Markets Act” section, gatekeepers are prohibited from combining personal data across different services without the explicit consent of the user, ensuring that consumers maintain control over how their information is shared and used (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 5(2)(d)). Users are also granted the ability to freely install or uninstall software applications and to modify default settings on core platform services, such as search engines, web browsers, virtual assistants, and app stores, without undue restriction or interference (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 5(2)(f)). Furthermore, to prevent anti-competitive practices and protect consumer choice, gatekeepers are not allowed to give preferential treatment to their own products or services when ranking, indexing, recommending, or displaying offerings on their platforms (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022, Article 6(1)). Collectively, through these measures, the Commission has attempted, in theory, to safeguard consumer privacy, autonomy, and access to a diverse and competitive digital marketplace.

2.3 Promoting More Contestable Market Environment

As this paper demonstrates, the European Commission has, at least in principle, committed to strengthening competition and reducing barriers in digital markets through a range of measures. The DMA prohibits several anti-competitive practices by designated gatekeepers. For example, as previously stated, Article 6 forbids self-preferencing and restrictions on business users’ ability to offer better conditions elsewhere. To illustrate this in a real-world context, prior to the DMA, the European Commission found that Google had promoted its own comparison-shopping service in general search results while demoting rival services. This conduct was deemed anti-competitive, as it disadvantaged market competitors and limited consumer choice (Carugati, 2022, p.2). In addition, Article 5(7) prohibits the combination of personal data from different services without user consent. Hnece, in practice, gatekeepers like Apple must ensure that user data from one service (e.g., iOS apps, Apple Maps, or Safari) cannot be automatically combined with data from another service (e.g., the App Store or Apple Music) without the user’s explicit consent (European Commission, 2025a). Collectively, these obligations were designed to limit incumbents’ ability to exploit entrenched positions and to prevent the foreclosure of competitors.

The DMA further addresses consumer lock-in and empowers business users. Article 6(9) requires gatekeepers to facilitate effective data portability, making it easier for users to switch services and reducing dependence on dominant platforms. For example, Booking.com launched a Data Portability API enabling travellers to transfer personal data, such as booking history and preferences, to other services, aligning with the DMA’s objectives to enhance user control and market contestability (Booking Holdings, 2024, p.3). Similarly, Article 5(4) ensures that developers can communicate directly with users, bypassing gatekeeper-imposed restrictions on commercial relations. For instance, in practice, Google Play’s “External Offers Program” allows developers to direct users to external websites or alternative app stores, supporting competition and consumer choice (Bethell, 2024).

Finally, Article 5(9) of the regulation mandates transparent advertising practices, requiring gatekeepers to provide business users with access to data needed to verify performance and pricing, thereby ensuring non-discriminatory access to digital markets (Regulation (EU)2022/1925, 2022). Collectively, these measures were originally intended to recalibrate power asymmetries, encourage innovation and expand opportunities for smaller firms. From a broader perspective, in doing so, they were, in theory, aimed at promoting a more open and competitive digital market.

3. Survey Methodology

The study is a quantitative online survey (computer-assisted self-interviewing – CASI) conducted through the Ipsos online panel. Respondents completed a structured questionnaire with an average length of 15 minutes. The survey was fielded across seven CEE markets: Slovakia, Czechia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The selection of markets was guided by the aim to capture a balanced picture of consumer experiences across Central and Eastern Europe, with representation from Central, Southern, and Baltic sub-regions.

A total of 500 respondents were interviewed in each market, yielding an overall sample of N=3,500. Within each country, quotas were applied by age, gender, and region to achieve representativeness of the national online population aged 18 and older. The survey was conducted using an opt-in online panel.

Fieldwork was conducted between 10–16 July 2025 in Slovakia, Czechia, and Hungary, and between 14–18 July 2025 in Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

The survey instrument was designed as a quantitative questionnaire with closed-ended items. Respondents were routed automatically within the survey according to their answers to ensure relevance of questioning.

The raw data collection was conducted by Ipsos using professional survey standards. All aggregations, comparisons, and policy interpretations in this paper are by ECIPE/EPPP. Ipsos contributed solely descriptive statistics and did not provide policy recommendations.

4. Survey Findings

Our analysis proceeds hypothesis by hypothesis, contrasting the European Commission’s stated promises with the survey evidence. In doing so, it highlights the contradictions that complicate the effective implementation of digital regulation and situates them within longer-standing patterns of consumer behaviour – particularly inertia, reliance on incumbent platforms, and the privacy paradox.

The result is a picture of a regulation whose consumer-facing ambitions remain largely unrealised, raising questions about whether the DMA can, in its current form, deliver on its central promise of empowering Europe’s digital citizens.

4.1 Promoting Better and More Affordable Services

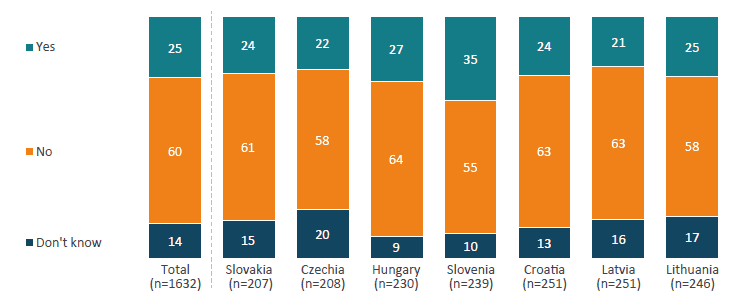

Survey data from Slovakia, Czechia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania reveals a disconnect between these aspirations and consumers’ actual experiences. Many users have not perceived clear improvements in service quality or cost: in fact, over half of consumers noticed no significant changes in how their digital services function. For example, only about one-third of respondents noticed the DMA-related changes to Google Search (the unbundling of Google’s travel results), and the changes were received without much enthusiasm (Figure 3). Roughly 40 per cent of those who noticed the change agreed it was positive, while the rest were neutral or negative – in Czechia nearly one-third rated the change negatively.

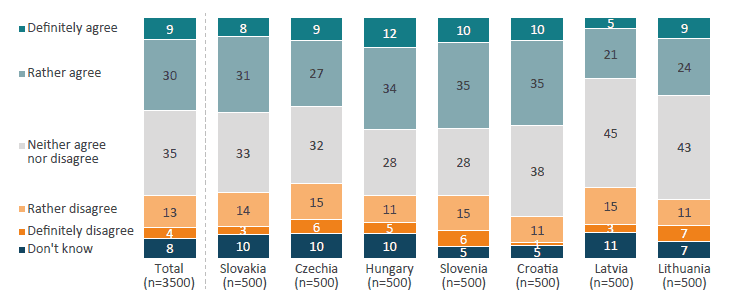

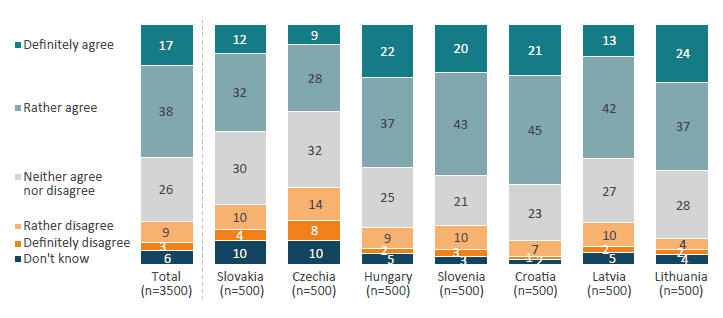

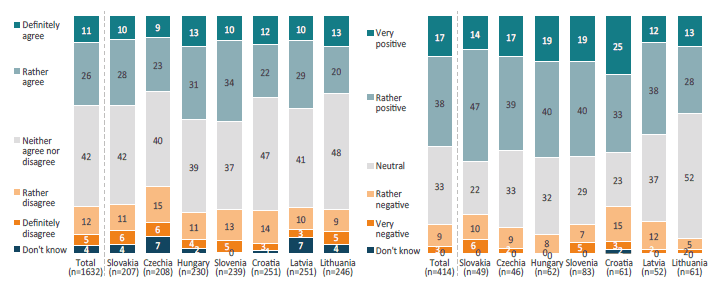

Rather than experiencing “better” services, a significant share of users reported additional, time-consuming friction: 39 per cent report needing more steps to complete previously simple tasks (Figure 4) after these changes, and approximately one-third of the surveyed perceive their digital experience as less seamless and more confusing. This suggests that some DMA-driven interventions (like removing integrated features or adding choice screens) have reduced convenience for end-users, contradicting the promise of a better experience.

Figure 3: Have consumers noticed changes in Google Search?

Figure 4: Agreement with the statement: I now need more steps to complete tasks that were simpler before

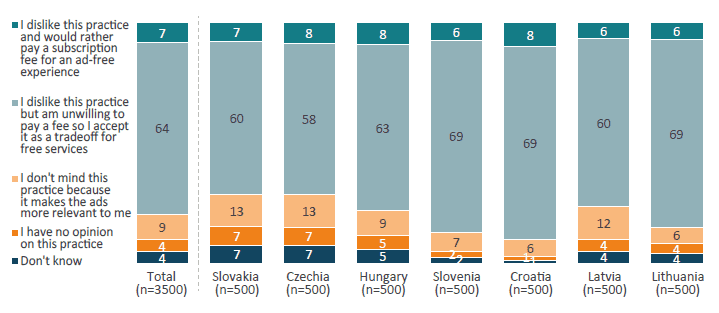

Crucially, there is no evidence of services becoming more affordable for consumers in this period. On the contrary, one high-profile change has been Meta’s introduction of a paid ad-free subscription on Facebook/Instagram – an option born from regulatory pressure to give users more privacy choice. This is a paradoxical outcome: to enjoy an untracked, “more private” experience, users must now pay (undermining affordability), or undergo a degraded experience, since a free option with fewer personalised ads includes more intrusive ad breaks inserted into feeds and stories (Kirkwood, 2025).

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of users are unwilling to pay for such subscriptions and instead continue with the status quo of “free” ad-supported services; over 60 per cent refuse to pay and accept personalised ads as a trade-off. In short, consumers have seen no tangible savings, while gatekeepers’ efforts to sidestep the DMA have made the user experience less fair.

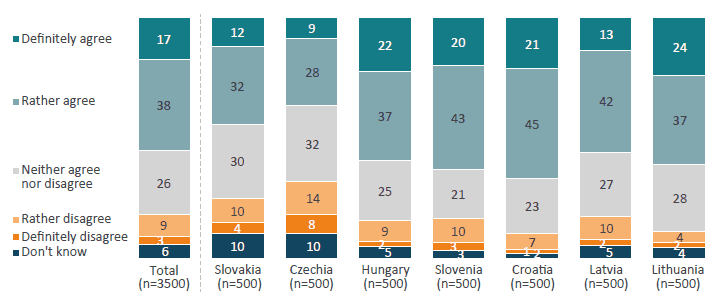

We interpret these survey results as highlighting a gap between the DMA’s intent and consumer-perceived outcomes. Users broadly support the idea of fairer, better services, yet in practice many are ambivalent. Notably, 55 per cent of surveyed consumers favour strong regulation in principle, even if it delays new features (Figure 5) – indicating support for the DMA’s goals. However, the same consumers simultaneously complain about inconveniences post-DMA (e.g. extra steps in Google Search).

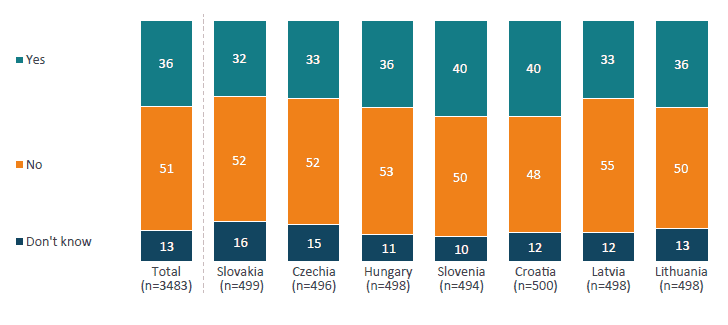

Figure 5: Agreement with the statement: I prefer stronger regulations and transparency even if it means delayed access to new features

This “regulation paradox” shows consumers want the benefits of intervention but resent downsides to their user experience. Another paradox: while the DMA assumes giving users more options will improve services, about 80 per cent of consumers were unfamiliar with the DMA, and only 20 per cent reported having at least partial information about the law (Figure 6). In practice, many simply notice a service becoming a bit less user-friendly without understanding it as a trade-off for long-term competitive benefit. The promise of better services at fairer prices thus rings hollow so far – improvements are either too subtle, too inconvenient, or too opaque for consumers to appreciate.

Figure 6: How familiar are consumers with the Digital Markets Act (DMA)?

Early analyses align with these empirical findings. Pape and Rossi (2025) examined Google’s EU search adjustments (removing direct map results to comply with the DMA) and found that Google’s steps led to higher search costs for users without significantly boosting the discovery or adoption of alternative mapping services in the short run. In other words, making Google’s service less integrated did not deliver a better or cheaper outcome for users – it mainly added friction, echoing the survey’s reports.

4.2 Promoting More Secure and Private Services

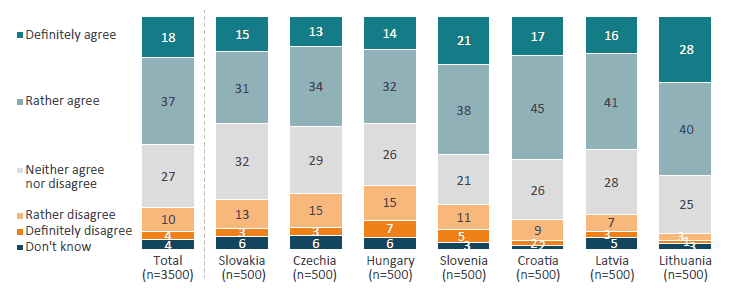

The survey reveals a privacy paradox in how consumers view the implemented changes. On the surface, users voice strong concern for privacy: 55 per cent say they are now more concerned about online privacy (Figure 7) and a majority support rules that protect personal data. Trust in Big Tech’s data handling remains low – generally, only 26-38 per cent of users trust platforms to protect their personal information. These attitudes align with the Commission’s justification for the DMA’s privacy-oriented rules.

Figure 7: Agreement with the statement: I am more concerned about my privacy and data protection now

However, when it comes to concrete actions and trade-offs, consumers behave in ways that undercut the promise of more private services.

4.2.1 Unwillingness to Pay for Privacy

The Ipsos survey found that while people dislike data-driven ads in principle, an overwhelming majority are unwilling to pay for an ad-free, privacy-enhanced service. Depending on the country, 60–69 per cent of users admit they accept pervasive data collection in exchange for “free” services (Figure 8) rather than pay a subscription fee for more privacy. Only a tiny minority (single-digit percentages) would actually pay to avoid personalised ads. This means that the DMA-mandated option to opt out of tracking (e.g. Meta’s new paid plan) has scant uptake – most consumers stick with the status quo. In practice, the average user’s privacy situation has not dramatically improved: they continue to be tracked and shown targeted ads as before, because opting into the new “more private” alternative is either costly or cumbersome. The Commission’s vision of masses of consumers enjoying tracker-free social media thus hasn’t materialised; instead, we see a begrudging tolerance of old data practices in order to keep services free.

Figure 8: Which statement best describes the consumers’ view on platforms collecting data to show personalised ads?

4.2.2 Perceived Trade-offs in User Experience

Measures introduced to enhance privacy often come with user-experience downsides that many consumers have noticed. For instance, Meta’s current EU model offers three paths: free use with consent to personalised ads, a free option with fewer personalised ads but more intrusive ad breaks inserted into feeds and stories, or a paid ad-free subscription (Kirkwood, 2025).

4.2.3 Security Concerns vs Openness

The DMA’s push for openness (like allowing third-party app stores on Apple’s iOS) raised questions about security in the survey. Case in point: Apple’s policy change to permit app downloads from outside the official App Store (a DMA-driven shift) elicited mixed feelings. Most users (over 60 per cent) did not even notice Apple’s change (Figure 9) during the survey period – a sign that the actual adoption of alternative app sources was minimal. Among the minority who were aware, opinions were split: roughly 55 per cent of those aware viewed it positively, but a large share were neutral and over 10 per cent had concerns or disagreed (Figure 10). The reservations often relate to security: consumers worry that downloading apps from outside a vetted app store could expose them to malware or low-quality content. In other words, the DMA’s promise of more secure services is not yet felt by users – if anything, some perceive greater security risks introduced by the new freedoms. From a consumer perspective, being allowed to do more (sideload apps, prevent cross-platform data use, etc.) has not yet translated into feeling more safe. Instead, many are either unaware of their new rights or unconvinced that exercising them is worth the hassle.

Figure 9: Have consumers noticed Apple’s policy change to permit app downloads from outside the official app store?

Figure 10: Do consumers agree with Apple’s change and how do they evaluate it?

The gulf between the DMA’s privacy promises and on-the-ground outcomes is evident. We see a classic privacy paradox: 55 per cent of CEE consumers express heightened concern for privacy, yet the same people largely stick with services that collect their data and balk at paying for privacy (Figure 7 and Figure 8). They want platforms to be better guardians of personal data (hence low trust), but they also want their personalised conveniences. The Commission assumed that giving users more control (opt-outs, alternatives) would automatically yield more private and secure usage. Instead, users are either ignoring those options or trading them away for convenience.

The net effect is that the average consumer’s digital life is not significantly more private than before – despite the DMA, targeted ads and data sharing remain commonplace because users implicitly consent by inaction. Security-wise, the intended safeguards of the DMA are double-edged: while it prohibits certain data combining (which may be good for privacy), it also compels ecosystem openness that could reduce perceived security. The survey data captures this ambivalence, with 55 per cent of people supporting regulation even if it delays features (Figure 11) (showing willingness to sacrifice a bit for privacy/security) yet simultaneously roughly a third still trusting platforms with data, meaning a majority remain uneasy or unconvinced.

There is a clear disconnect between the regulatory ideal of privacy and the pragmatic choices of consumers. While most users are unaware of the DMA, those who have heard of it may assume it is delivering stronger privacy and cybersecurity protections. In practice, however, the promise of more secure, privacy-centric services remains only partially fulfilled – consumers may welcome the idea of greater privacy, but few have tangibly benefitted on a broad scale.

Figure 11: Agreement with the statement: I prefer stronger regulations and transparency even if it means delayed access to new features

This consumer-level ambivalence mirrors broader policy concerns highlighted in recent research. As Bauer and Pandya (2025) note, the DMA’s over-enforcement may compromise cybersecurity by forcing platforms to prioritise openness over trust and safety. For instance, Article 5(4) could force operating systems to allow unregulated external links, bypassing established security vetting and exposing users to malware, phishing, and spyware. Apple has already withheld certain AI-powered features and advanced security tools from EU users due to these regulatory uncertainties, while Android’s open architecture risks being further fragmented by mandated third-party linkouts. Such outcomes could leave European consumers with reduced security and fewer innovations compared to other regions.

In this sense, the consumer paradox captured in our survey – voicing greater concern for privacy yet tolerating invasive defaults is compounded at the regulatory level, where rules intended to empower users may inadvertently weaken the very protections they value. The survey further shows that consumers prioritise a seamless, simple, and free user experience over the very privacy and control they claim to desire.

4.3 Promoting More Contestable Market Environment

Thus far, the survey data indicates that consumer behaviour remains heavily skewed towards incumbent platforms, with limited evidence of increased switching or adoption of alternatives.

4.3.1 Reliance on Gatekeepers

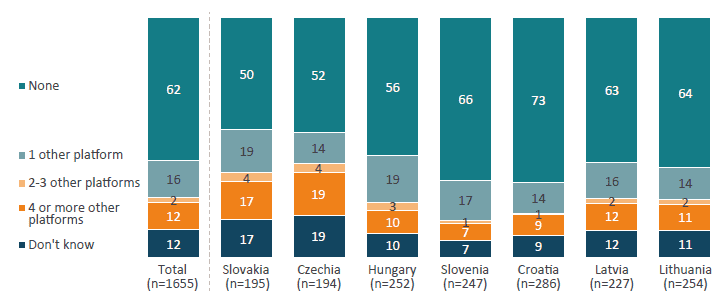

Usage patterns show that major platforms still dominate daily life according to the Ipsos survey. An astonishing 70 per cent of individuals use Google Search multiple times a day (Figure 12) and over 75 per cent use Facebook daily (Figure 13). These figures underscore strong incumbency advantages – users are accustomed to and dependent on the services of designated gatekeepers. If the DMA were truly making markets contestable, we might expect a decline in single-platform dominance or at least an uptick in consumers engaging with multiple providers. But the opposite appears true: a large share of users do not utilise any alternatives. Approximately half of CEE users use no alternative to Google’s services at all (only Google for search, maps, etc.) (Figure 14), and nearly 40–50 per cent use no alternative to Facebook (Figure 15) or Instagram (Figure 16) as social media platforms. For professional networking, the monopoly is even starker – over 60 per cent of people have no alternative to LinkedIn in use (Figure 17). In summary, many consumers are “single-homing” on the very gatekeeper services the DMA targets, and this behaviour has not markedly changed in the post-DMA environment.

Figure 12: How often do populations use Google Search?

Figure 13: How often do populations use Facebook?

Figure 14: How many alternative platforms do people use to Google?

Figure 15: How many alternative platforms do people use to Facebook?

Figure 16: How many alternative platforms do people use to Instagram?

Figure 17: How many alternative platforms do people use to LinkedIn?

4.3.2 Limited Adoption of New Choices

The DMA’s contestability measures (e.g., easier app switching on phones, choice screens, interoperability requirements) were expected to encourage consumers to explore new services. However, consumer awareness and uptake of such options are low. As noted, according to the Ipsos survey, most Apple users didn’t notice or act on the ability to install third-party apps. Similarly, when asked about recent changes enabling competition (like the introduction of new apps or platforms), a significant portion of consumers either did not notice changes or were unsure of their purpose. Large share (23–41 per cent) of users who did see changes weren’t sure those changes were related to the DMA at all – reflecting a knowledge gap that likely blunts the impact of contestability. In effect, new opportunities to switch are emerging without consumers seizing them. This is echoed by another finding: when presented with scenarios of new digital services or features being delayed or absent in the EU (due to regulatory compliance or caution), a majority of CEE consumers admitted they had not noticed the absence of those would-be alternatives (e.g. the EU delay of Meta’s Threads app launch, or Apple’s AI tools) and did not feel an immediate loss. Such indifference suggests that many consumers are not actively seeking out alternatives, even when gatekeepers hold certain offerings back. The competitive spark the DMA hoped to ignite among users – trying new services, switching to better deals – is so far only a faint glimmer.

4.3.3 Persistent Network Effects and Habits

The survey and broader evidence point to enduring network effects that make contestability hard to achieve on the demand side. Users stick with WhatsApp because all their friends are there, or with Facebook because that’s where their social circles and content are. These ingrained habits were never going to change overnight, and indeed the data shows consumer inertia. For example, even when Google removed a favoured convenience (the Google Maps preview in search results) to comply with neutrality, most users simply adjusted and continued using Google – they did not flock to rival mapping services. In fact, a recent empirical study by Pape and Rossi (2025) confirms that after Google’s change, traffic largely stayed within Google’s ecosystem: searches for Google Maps increased (users took an extra step to get back to Google Maps), while traffic to competing map providers saw no significant boost. This real-world experiment in “contestability” reveals that simply removing a gatekeeper’s self-preference is not enough to alter consumer behaviour en masse – users didn’t switch to Bing Maps or some startup alternative; they stuck with Google, albeit with minor inconvenience. Such outcomes underscore that the barriers to contestability are as much behavioural and cultural as they are structural. The DMA can ban certain gatekeeper practices, but it cannot force consumers to suddenly explore obscure alternatives. As of 2025, the CEE consumer experience remains one of concentrated usage – the very scenario of limited choice the DMA sought to improve.

4.3.4 Disconnects and Paradoxes

There is a clear paradox in the contestability narrative – consumers conceptually welcome more choice (who wouldn’t want options?), yet their actions show loyalty or apathy toward alternatives. The greater contestability in the market has not yet felt like greater choice for the average user, who continues using the familiar services out of habit or convenience. Another disconnect the study notes is informational: consumers can’t take advantage of new options they don’t know exist – and with about 80 per cent unfamiliar with the DMA (Figure 6) and its purpose, there is an “awareness gap” dampening the law’s impact. In sum, the market may be more contestable on paper, but not on the street. The intended virtuous cycle (more competition leads to more consumer switching, which leads to even more competition) is stuck at its early stage because consumers have yet to significantly change their platform usage.

Colangelo and Martínez (2025) stress that the success of the DMA should be measured in real market outcomes – notably, whether contestability and fairness actually increase. They argue that while these are the DMA’s ultimate protected interests, true success hinges on meeting underlying policy goals like genuine openness and the neutralisation of unfair advantages. By these metrics, the initial evidence is sobering. Our findings echo the view that compliance formalities alone mean little unless consumer behaviour shifts. Pape and Rossi (2025), for example, underscore that simply adding a “choice” does not guarantee it will be taken – the DMA’s interventions in search did “not substantially increase traffic to Google’s competitors”. Likewise, a truly contestable market would manifest in things like multi-homing (users regularly using several platforms interchangeably) or declining user-share of the biggest firms – neither of which is apparent yet in the CEE region. Instead, we see what one might call contested on paper, entrenched in practice.

For stakeholders, this paradoxical outcome is instructive. It suggests that while the DMA has begun to pry open closed doors (legally speaking), consumer habits lag behind. To rebut the Commission’s rosy assumptions, one must highlight this fact: greater theoretical choice has not yielded a substantially different experience for the average consumer so far. If contestability is the goal, regulators may need to pair the DMA with efforts to inform and empower users, not just constrain gatekeepers. The regulator’s definition of success should move beyond legal compliance and include metrics that measure actual consumer empowerment, such as the rate at which consumers adopt new alternatives. Right now, those metrics – alternative usage, switching rates, user satisfaction with new options remain underwhelming. The early results from Central/Eastern Europe serve as a reality check: market contestability cannot be declared achieved until consumers visibly exercise their new choices.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations for Policy-Makers

This survey-based study shows that, despite its ambitious promises, the DMA has so far delivered only partial, and often paradoxical outcomes for consumers in CEE. The European Commission’s vision of more affordable, private, and contestable digital services has run up against entrenched consumer habits, limited awareness, and unintended compliance side-effects, including negative implications for data and cybersecurity.

Consumers report very little evidence of lower prices or more affordable digital services. On the contrary, regulatory interventions have in some cases created new frictions – such as additional steps in search or choice screens that diminish convenience. Privacy requirements have led to the paradoxical outcome that consumers are now asked to pay for ad-free experiences – an option the overwhelming majority are unwilling to accept. The DMA’s promise of more secure and private services therefore remains unfulfilled: people value the idea of privacy but are unwilling to sacrifice convenience or cost.

Perhaps the clearest disconnect lies in the area of contestability. The DMA has introduced measures intended to loosen gatekeepers’ dominance, yet consumer behaviour remains largely unchanged. Reliance on Google, Meta, Apple, and other incumbents remains as strong as ever, reinforced by powerful network effects, ingrained consumer habits, and limited interest in alternatives that offer less value and weaker user experiences. Market contestability keeps existing on paper, but not in practice.

These results are not a call to abandon the goals of fairer and more open digital markets, but rather a reminder that prescriptive ex-ante regulation alone cannot transform consumer behaviour or market outcomes. Europe risks repeating past mistakes: regulating with the best of intentions while inadvertently curbing innovation, degrading services, or entrenching the very firms it seeks to challenge.

The way forward requires a recalibration. Looking ahead, two broad policy paths emerge for Europe. Both stem from the empirical reality highlighted in this study that the DMA has not delivered on its core consumer promises and risks entrenching costs without generating corresponding benefits for users or for those seeking to challenge incumbents.

Option 1 – Repealing the DMA and Return to Case-by-Case Competition Enforcement

Based on our interpretation of the survey data, we recommend repealing the DMA entirely and reverting to a more proven system of case-by-case competition law enforcement. This is ECIPE/EPPP’s policy position and is not derived from or endorsed by Ipsos. This approach, grounded in the consumer welfare principle as in US antitrust law, avoids the pitfalls of vague, one-size-fits-all obligations that constrain innovation and degrade services (Bauer, et al, 2022).

- Flexibility and proportionality: Case-by-case enforcement ensures that interventions are targeted to real demonstrable harms rather than assumed harms, reducing unnecessary regulatory burdens and aligning with OECD principles of proportionality and legal certainty.

- Avoiding regulatory overreach: The DMA assumes harm ex ante, leading to blanket restrictions. This is as flawed as the opposite Chicago School extreme, where harm is too easily excused. Case-by-case review avoids both errors by focusing on evidence and consumer outcomes.

- Protecting consumers: Companies should not be forced to make costly and disruptive compliance changes before courts have reviewed disputes. Rushed compliance risks degraded services, reduced functionality, and higher costs for users.

- Consistency and neutrality: Enforcement should be applied transparently and consistently across the digital ecosystem, with remedies proportionate to proven harm and revenue thresholds, rather than singling out specific firms.

By removing the “sand in the wheel” of Europe’s digital economy, this approach would restore dynamism, attract investment, and ensure that innovation in new technologies such as 5G, AI, and digital ecosystems is not stifled.

Option 2 – Targeted Reform: Remove Obligations that Do Not Enhance Consumer Welfare

If outright repeal is not politically feasible, a second-best path would be to significantly scale back the DMA by removing obligations that create false expectations or fail to deliver tangible consumer benefits.

- Remove ineffective obligations: Rules such as interoperability mandates and choice screen requirements should be revisited, especially where they reduce convenience, introduce security risks, or fail to generate real consumer uptake.

- Refocus on consumer benefits: Regulation should prioritise functionality, affordability, and access to best-in-class technologies, rather than formalistic compliance. Measures that do not demonstrably improve consumer welfare should be withdrawn.

- Ensure neutrality and fairness: Obligations should be applied across the ecosystem with objective criteria, avoiding distortions that favour or penalise firms based on origin rather than market position.

- Prevent innovation loss: By curbing over-broad restrictions, Europe can avoid repeating the missed opportunities of the 4G and app economy era. A lighter, targeted framework would reduce costs for firms and maintain incentives to launch new digital services in the EU.

- The DMA’s interoperability (Article 7) and marketplace access (Article 6(4)) mandates should be reconsidered until regulators can guarantee that they do not undermine consumer safety, privacy, or service quality. Obligations to open messaging systems, app stores, and online marketplaces to third parties may create significant risks from weakened encryption and legal contradictions under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, to exposure to fraudulent products, counterfeit goods, and malware. Enforcement should therefore be conditional on clear, uniform technical and consumer protection standards, such as end-to-end encryption, independent certification, and robust liability frameworks. Without such safeguards, these obligations risk degrading the user experience and trust in digital services, while delivering little of the contestability they were intended to achieve (Barczentewicz, 2023).

- Reassess self-preferencing prohibitions (Article 6(5)): Experience since implementation suggests that blanket bans on self-preferencing can degrade service quality and user experience without clearly improving competition. Removing integrated features such as shopping, maps, or travel previews has led to more steps for consumers and limited efficiency gains for rivals. The rule should therefore be repealed or at least suspended until regulators can demonstrate that neutrality mandates produce measurable benefits in consumer welfare, innovation, or market entry. Enforcement should be conditional on evidence that end-users, rather than competitors alone, derive tangible value.

- Adapt to regional realities: In CEE, where markets differ significantly, the Commission should apply transparent criteria for adjustments and consult broadly with stakeholders. This would ensure predictability while accounting for local conditions.

Under this option, the DMA would survive in name but be re-oriented towards consumer-relevant goals, stripping away measures that are symbolic rather than substantive – including interoperability mandates, marketplace-access rules, and rigid self-preferencing prohibitions that erode convenience without fostering genuine choice.

References

Bauer, M. and Pandya, D. (2025). Cybersecurity at Risk: How the EU’s Digital Markets Act Could Undermine Security across Mobile Operating Systems. European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). Available at: https://ecipe.org/publications/the-eu-digital-markets-act/.

Bethell, O. (2024) Complying with the Digital Markets Act., Available at: https://blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/complying-with-the-digital-markets-act/.

Booking Holdings (2024) Digital Markets Act Compliance Report Available at: https://www.bookingholdings.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/DMA-Compliance-Report.pdf.

Barczentewicz, M. (2023, July 6). How the new interoperability mandate could violate the EU Charter. Lawfare. Available at: https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/how-the-new-interoperability-mandate-could-violate-the-eu-charter.

Bauer, M., Erixon, F., Guinea, O., van der Marel, E., & Sharma, V. (2022, February). The EU Digital Markets Act: Assessing the quality of regulation. European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). Available at: https://ecipe.org/publications/the-eu-digital-markets-act/.

Carugati, C. (2022) ‘How to implement the ban on self-preferencing in the Digital Markets Act’, Policy Contribution 22/2022, Bruegel, Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/system/files/2022-12/PC%2022%202022_3.pdf.

Cennamo, C. et al. (2025) Economic impact of the digital markets act on European businesses and the, https://www.dmcforum.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/120625-FINAL-CCIA-DMA-Report-1.pdf. Available at: https://www.dmcforum.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/120625-FINAL-CCIA-DMA-Report-1.pdf (Accessed: 03 October 2025).

Chan, K. (2025) ‘Microsoft resolves European Union probe into Teams’, AP News, 12 September. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/microsoft-teams-antitrust-european-union-competition-61a94a85f04df5183f2b8f81bc9468e5.

Colangelo, G. and Martínez, A.R. (2025) ‘The metrics of the DMA’s success,’ European Journal of Risk Regulation, pp. 1–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2025.4.

European Commission (2020) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Accompanying the document Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act), EUR Lex. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020SC0363.

European Commission (2025a) Commission finds Apple and Meta in breach of the Digital Markets Act., Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1085.

European Commission (2025b) Gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act (DMA): designation list and core platform services. Available at: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/gatekeepers_en.

European Commission (2025c) EU issues preliminary findings that Google may have breached the Digital Markets Act by favouring its own services. European Commission Press Corner, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_811.

Kirkwood, M. (2025) Understanding the Apple and Meta Non-Compliance Decisions under the Digital Markets Act. Available at: https://www.techpolicy.press/understanding-the-apple-and-meta-noncompliance-decisions-under-the-digital-markets-act/.

Nextrade Group (2025) Impact of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) on consumers across the European Union: Results from a survey with 5,000 consumers. Available at: https://www.nextradegroupllc.com/_files/ugd/478c1a_9d7c98475ce8404188d2f8dbb1c9d2ff.pdf.

Pape, L.-D. and Rossi, M. (2025) Is Competition Only One Click Away? The Digital Markets Act Impact on Google Maps. Munich Society for the Promotion of Economic Research – CESifo GmbH. Available at: https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/cesifo1_wp11226.pdf.

Regulation (EU)2022/1925 (2022) of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act) Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2022.265.01.0001.01.ENG.

Rombolà, R. (2023) ‘Digital Markets Act and the interoperability requirement: is data protection in danger?’, MediaLaws. Available at: https://www.medialaws.eu/digital-markets-act-and-the-interoperability-requirement-is-data-protection-in-danger/.

Spotify (2024) ‘The DMA means a better Spotify for artists, creators, and you’. Spotify Newsroom. Available at: https://newsroom.spotify.com/2024-01-24/the-dma-means-a-better-spotify-for-artists-creators-and-you/.

Vestager, M. (2024) Speech by EVP Margrethe Vestager at the European Competition Network Conference on the DMA, Speech by EVP Margrethe Vestager at the European Competition Network conference on the DMA. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_3442.

Authors

European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE)

The European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) is an independent and non-profit policy research think tank. ECIPE works in the spirit of the open society – a society that embraces the traditions and principles of free trade and economic freedom. Our work is focused on international trade, regulation, digitalisation, and other international economic policy issues of importance to Europe. We are a research-based think tank with the ambition of providing decision-makers and observers with sound economic and political analysis.

European Public Policy Partnership (EPPP)

The European Public Policy Partnership (EPPP) is a non-governmental think tank established in 1998 with offices in Bratislava and Brussels. For over 25 years, we have represented the interests of Central and Eastern European (CEE) businesses, amplifying their perspectives on how to improve the business environment so they can focus on what they do best: creating value for customers and contributing to prosperous, innovative economies that help bridge the gap between newer and older EU member states.