The UK’s First International Trade Negotiation – Agriculture at the WTO

Published By: David Henig

Subjects: Agriculture European Union UK Project

Summary

There are few issues that cause more controversy in international trade policy than agriculture. The EU’s overall agriculture policy, including domestic support, tariffs, and Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs), are an ongoing irritant with trade partners. The UK government has spoken of being more liberal.

This is the context for the UK’s first international trade negotiation since the Brexit vote, to set our future WTO schedules, including calculating our TRQs. There has been optimistic talk from UK Ministers and influential advisers about UK leadership helping renew the impetus for trade liberalisation at the WTO. This process could therefore be an opportunity for the UK to show a liberalising instinct, and a sensitivity towards the differing interests of different countries.

So far the UK is struggling. The proposed approach to assert a new schedule, calculated on the basis of average historical usage of the previous EU TRQs, is seen by agricultural exporters as counter to WTO rules as they would suffer a loss of market access from the loss of flexibility, and failure to account for produce currently crossing borders once inside the EU. Given that all countries have to certify the schedule, a full negotiation will be needed. The EU, who joined the UK in proposing this approach, have now accepted this need. The UK government has sent mixed signals regarding following this lead, but we expect they will need to do so shortly.

The UK needs to find a new more liberal approach in line with Government policy. The UK Withdrawal Agreement may provide a period of time during which unfettered trade with the EU will continue, which should allow continuing single management of the existing TRQs n the short term. The UK should use this extra time to run a domestic consultation process with a Green Paper on agriculture and trade, aiming at an outcome that will deliver liberalisation alongside clarity and reassurance for domestic interests. The evidence suggests that such an outcome is attainable.

In the event that the UK leaves the EU without a deal in March 2019 the UK’s current approach will also not work, given the existing trade between the two, and would definitely require a significant renegotiation by both EU and UK after a short term solution was put in place. Thus the case for the UK taking a fresh look at splitting Tariff Rate Quotas would seem to be overwhelming. It should be fine to admit that the initial approach was optimistic, and that having now considered further we are going to deliver something better.

Introduction and Context – Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) and Brexit

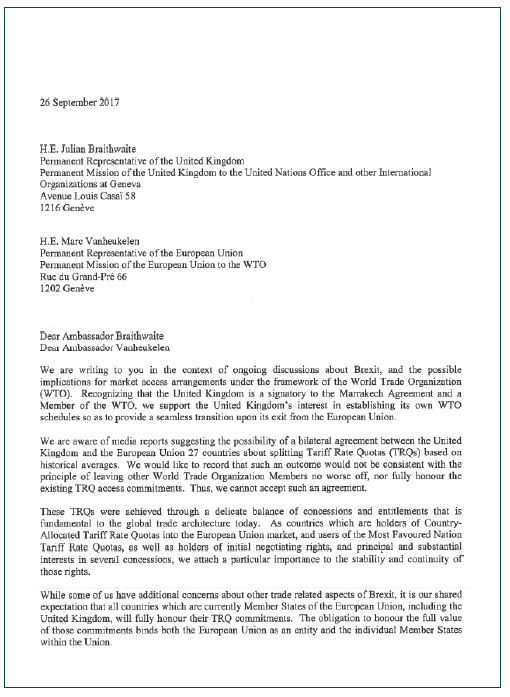

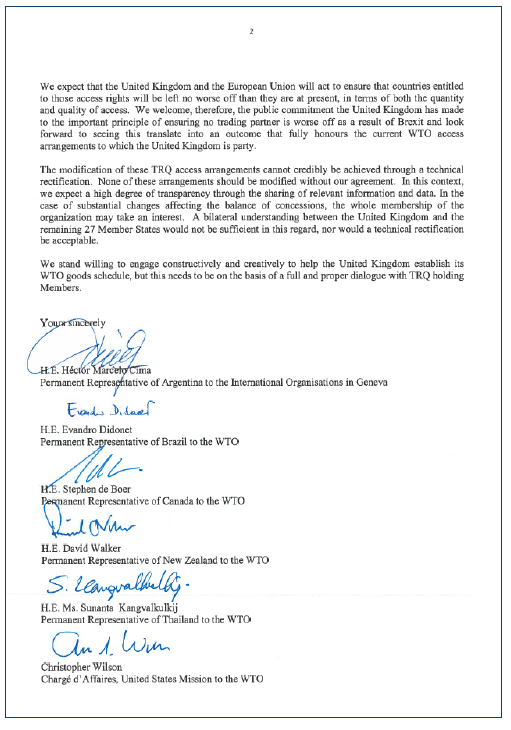

On 26 September 2017 a letter was sent to the UK and EU Ambassadors to the WTO by their counterparts from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, Thailand, USA and Uruguay. Regarding initial conversations about establishing UK specific WTO schedules, the letter stated:

“We are aware of media reports suggesting the possibility of a bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union 27 countries about splitting Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs)[1] based on historical averages. We would like to record that such an outcome would not be consistent with the principle of leaving other World Trade Organization Members no worse off, nor fully honour the existing TRQ access commitments. Thus, we cannot accept such an agreement.”

The UK’s first international trade negotiation since joining the EU in 1973 had commenced. For the avoidance of doubt the letter, reproduced in Annex 1, also stated that: “The modification of these TRQ access arrangements cannot credibly be achieved through a technical rectification. None of these arrangements should be modified without our agreement.”

The UK government is perhaps yet to understand the full implication of this letter. In an answer provided to Parliament on 21 November, then Minister of State for Trade Greg Hands said “In order to replicate as far as possible current obligations under the WTO… the government is preparing full UK-specific schedules under the GATT….. The government plans…. to assert them after leaving the EU[2].”

The EU realised that an approach based on simply asserting the split of TRQs would not work, and as reported on 25 April 2018, proposed a full renegotiation, based on WTO Article 28[3], for their schedules. This was approved by Member States in June 2018. The UK Government has said it may follow suit if required for some TRQs, but asserting our new schedules remains the main plan. Secretary of State Liam Fox said recently that the EU reducing their TRQ requires a negotiation, but this is not required for the UK[4]. Contrary to what he suggested, major agricultural countries remain opposed, and this is likely to mean a full negotiation. The UK submitted schedules to the WTO Secretariat on July 19, as the first step in the process.

This paper explains why the UK is in this difficult situation at the WTO, and outlines alternate options. In the next section we briefly explain the UK’s vision for trade. Section 3 then looks at detail at TRQs, how they emerged, why this is significant in the debate over splitting them, and why other countries reject the proposed approach. Section 4 provides a framework to evaluate the UK’s options, and Section 5 proposes options for how the UK can reach agreement at the WTO. Although mostly UK focused we also touch on how the EU is managing this situation, recalling that the TRQ split is an issue in all Brexit scenarios.

[1] A Tariff Rate Quota is often used as a protectionist measure in agriculture, whereby a certain level of import of a product can enter a country at a reduced or eliminated tariff compared to a high applied tariff for any further import. See Section 2, and https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/agric_e/negs_bkgrnd10_access_e.htm

[2] https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2017-11-15/113264/

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/apr/25/resistance-to-joint-proposal-to-wto-leaves-uk-and-eu-divided-us-australi-reject-brexit-trade-plans

[4] http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/international-trade-committee/the-work-of-the-department-for-international-trade/oral/86825.pdf

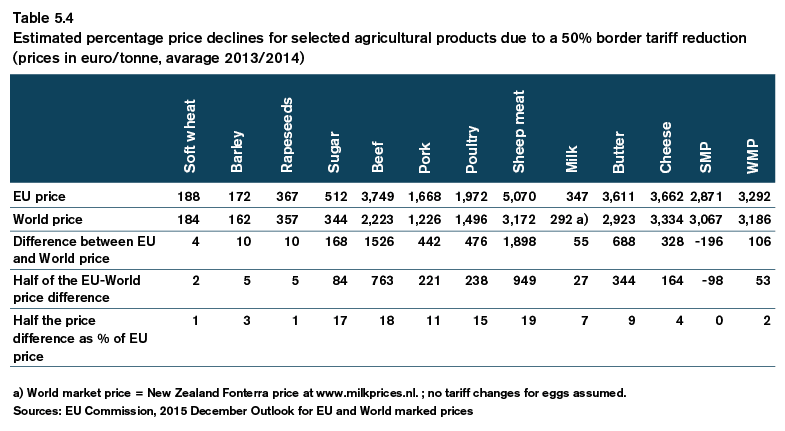

The Vision for UK Trade Policy at the WTO and with the EU

There is plenty of scope for agricultural trade liberalisation for the EU and UK. The table[1] shows in the 3rd row the difference between the EU and world price of different commodities, with the final row considering a trade-policy scenario in which the UK will lower its external tariff by 50%. The UK government has high aspirations to be liberal in its future trade policy. As Liam Fox said in his first speech as Secretary of State for International Trade “As we leave the European Union, the United Kingdom will want to play a full part in global trade liberalisation utilising all the tools and arrangements available[2].”

The UK government has high aspirations to be liberal in its future trade policy. As Liam Fox said in his first speech as Secretary of State for International Trade “As we leave the European Union, the United Kingdom will want to play a full part in global trade liberalisation utilising all the tools and arrangements available[2].”

Shanker Singham, an influential adviser to the UK government, has gone further, in expressing that “We need to operate decisively in the World Trade Organisation (WTO), to galvanise the stalled trading agenda, and to improve economic conditions around the world. As the world’s second largest exporter of services and one of the world’s largest foreign investors and sites of foreign investment, the UK with an independent trade policy will make a difference in WTO councils. If you had to invent a country to galvanise those stalled processes, this is the one you would invent.[3]”

A more sobering assessment was provided by WTO expert Peter Ungphakorn, who suggested that before the UK took up such leadership in the WTO they “might like to look at the many coalitions that already exist and how power is structured in reality in the organisation[4].”

Many of the countries with the greatest interest in agricultural TRQs at the WTO are also priority countries for new UK bilateral Free Trade Agreements, consultation on which has commenced[5]. The Secretary of State has argued that this means issues in WTO TRQs can be resolved bilaterally “What we said to them is we are opening up the process of a bilateral FTA and it would seem unproductive to have the United Kingdom’s capacity at WTO tied up in a process about TRQ disaggregation rather than be constructively moving to what the future trading relationship would be[6].” It is unlikely that countries would be persuaded on this basis to back a UK TRQ at the WTO they found to be limiting. It is also yet to be seen whether bilateral FTAs will be possible in the context of the UK’s future trading relationship with the EU.

[1] https://www.nfuonline.com/assets/61142

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/uk-is-open-for-business-like-never-before

[3] https://reaction.life/can-uk-become-global-leader-free-trade-post-brexit/

[4] https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/2017/11/08/uk-wto-leadership/

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-public-consultations-announced-for-future-trade-agreements

[6] http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/international-trade-committee/the-work-of-the-department-for-international-trade/oral/86825.pdf

Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs)

Tariff Rate Quotas were formalised in the global trading system by the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture which entered into force on 1 January 1995. They were intended as a trade liberalising measure, to prohibit non tariff barriers in agriculture such as “quantitative import restrictions, variable import levies, minimum import prices, discretionary import licensing procedures, voluntary export restraint agreements and non-tariff measures maintained through state-trading enterprises[1],” and replace these with “import access opportunities at levels corresponding to those existing during the 1986-88 base period,” of at least 5% of domestic consumption by 2000 for developed countries.

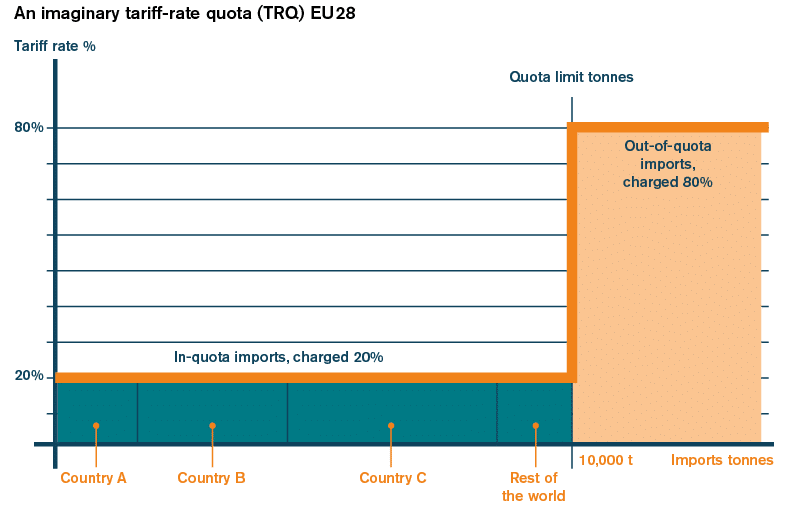

A TRQ is a two-tier tariff, with a certain amount of produce allowed in a reduced or zero rate, the rest subject to a higher rate on a WTO Most-Favoured Nation basis. These quotas can be open to all countries (erga omnes), or to specific countries (see illustration[2]). Bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) may also include specific TRQs, although as yet the EU does not have FTAs with major agricultural exporters such as Brazil, Australia and New Zealand. The effect of TRQs in practice has been to place a ceiling on certain agricultural imports. In effect, erga omnes rates are set to prevent any meaningful trade out of quota[3].

The effect of TRQs in practice has been to place a ceiling on certain agricultural imports. In effect, erga omnes rates are set to prevent any meaningful trade out of quota[3].

EU and UK trade and Tariff Rate Quotas

The EU has TRQs for numerous agricultural products including virtually all meat, staples like wheat and potatoes, cheese, and numerous fruits such as lemons and grapes. These are administered by the EU, but once the product concerned enters the EU it is not tracked, meaning that there are no reliable country specific import figures.

Take the example below of wheat. The table[4] shows the different TRQs in operation for wheat, and the percentage that the EU has calculated based on import licenses has gone directly into the UK or the remaining EU-27, based on an average for the years 2013-2015. It is intended that the last two columns will be the future TRQs for the EU27 and UK.

These figures are not the total import of the commodity. In addition to TRQs imports can come from:

- FTA partners who have reduced tariff or tariff free rates in these agreements;

- Developing countries who are the beneficiaries of unilateral preferences allowing tariff free quota free import into the EU;

- Any country at WTO MFN tariff, though as already discussed this may be uncompetitive;

- Within the EU.

Trade in agriculture is complicated and intensely political. Talks aiming at an EU-Mercosur (which includes Brazil and Argentina) Free Trade Agreement commenced in 1999[5] and have still not been completed, with a major issue being the TRQ that would be given to Mercosur for beef products[6].

The split of UK and EU TRQs in FTAs and at the WTO will affect our diplomatic relations and potential trade agreements for years to come. It is worth ensuring that we do this as well as possible.

The UK/EU proposed approach to splitting TRQs

The splitting of TRQs between the UK and EU is part of the wider work that both sides need to undertake as a consequence of the UK leaving the EU[7]. At present the UK’s schedules at the WTO, such as the level of tariffs paid, are those of the EU. We need to have our own independent schedules by the end of March 2019, and this lay at the heart of the UK’s proposal to use a process known as technical rectification, where we would replicate as closely as possible our existing position.

While an understandable approach given the time available, the plans have already caused some damage to the UK’s reputation in the WTO because they are perceived to withdraw market access in contradiction to our liberalising words. This is because exporting countries see a TRQ split as removing the flexibility to export to either UK or EU, and then potentially see produce distributed around the EU. Existing supply chains frequently use the EU mainland as a route to the UK market. There is no data available on how much produce originally imported to the EU27 then enters the UK in this way, but it is known that there are importers who rely on this channel. Their ability to source agricultural produce in the future could be at risk under UK plans. All of this is sufficient for exporting countries to have legal grounds to object to the new UK schedules, particularly as the future EU-UK trading relationship is uncertain.

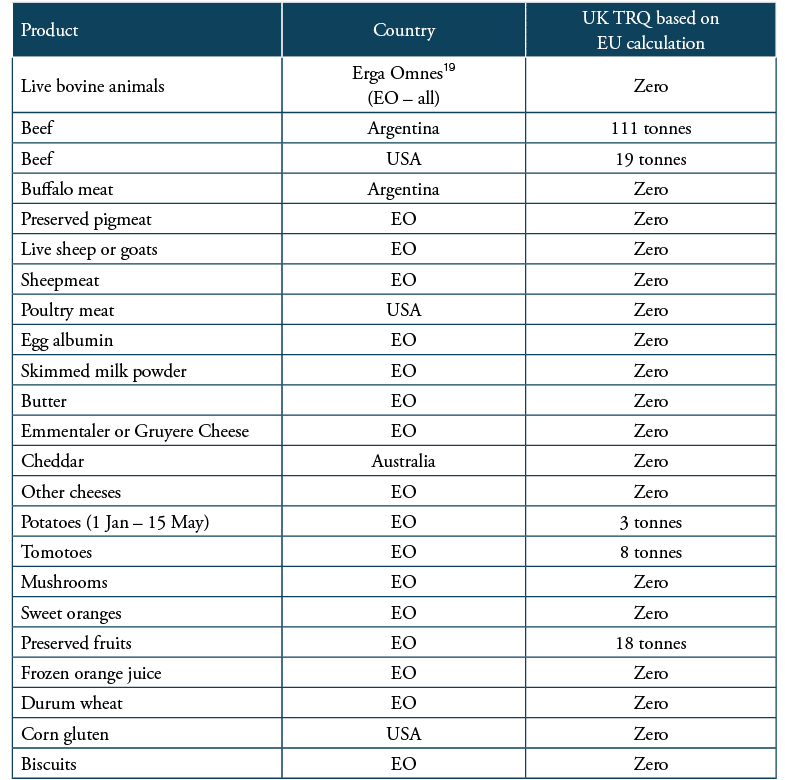

It does not help that the 3 year average numbers[8] that were based on where import licenses have been issued in the EU are in many cases inconsequential. Take for example imports of beef from Argentina. There is a total EU CSTQ (country specific tariff quota) of 29,000 tonnes, of which the EU suggest 99.6% is licensed to countries other than the UK. This would lead to the UK having a CSTQ of Argentinian beef of 111 tonnes. This is almost certainly lower than the actual amount of Argentinian beef consumed in the UK, and clearly unacceptable to Argentina. Below we show imports where the UK will offer a TRQ or CSTQ of zero (i.e. outside of bilateral arrangements all imports will be at WTO rates), and other small numbers that are likely to cause serious concern:

It is quite clear that for these TRQs at a minimum the proposed split is not going to be acceptable in the way the UK intends. It should be added that the UK will come under pressure to revise some of the inconsistencies between countries that have country-specific tariff quotas (CSTQs), notably the TRQ that New Zealand has for sheep meat of 228,000 tonnes, compared for example to Australia’s TRQ of 19,000, where the latter argues the overall lamb production and quality standards are broadly equivalent[10].

There are also splits which would leave a zero or much reduced TRQs for imports into the EU-27. This is for example the case with Grape Juice (all examples erga omnes, zero), sausages (164 tonnes), and Apricots between August and May (74 tonnes). The points made above around shipment between UK and EU, and in particular on country specific TRQs, will also be relevant. Agricultural exporters are therefore going to want to consider EU and UK offers on TRQs together.

WTO processes

The UK government wish to invoke the 1980 Procedures for Modification and Rectification of Schedules of Tariff Concessions at the WTO[11]. It provides that: “Changes in the authentic texts of Schedules shall be made when amendments or rearrangements which do not alter the scope of a concession are introduced in national customs tariffs in respect of bound items. Such changes and other rectifications of a purely formal character shall be made by means of Certifications”. However this relies on there being no objections from members as the revised schedules “shall become a Certification provided that no objection has been raised by a contracting party within three months.” This therefore requires that all countries believe the UK’s new TRQs do not alter the scope of their concessions. As we have seen this is unlikely to be the case.

The alternative as already discussed is an Article 28 negotiation. This is typically not quick, and it should be noted that putting in place schedules without agreement risks retaliation as a Member with substantial supplying status can withdraw “substantially equivalent concessions initially negotiated” if “not satisfied” with the proposed change to the Tariff Schedule.

There is an argument that the UK should be fine in proceeding without a certified schedule, as it took the EU 12 years from the accession of countries in 2004 to reach a certified goods schedule. However as Peter Ungphakorn notes[12] “The EU appears to [be] operating with de facto schedules, for example revised tariff quotas appear in EU regulations. And it can trade without disruption, apparently because it has talked to key trading partners and adjusted its tariff quotas accordingly. The latest regulation for the lamb and mutton tariff quota states that the quota has been expanded for New Zealand, to accommodate Bulgaria and Romania becoming new EU members (but not yet for Croatia). In other words, unilaterally creating the UK’s draft schedules without taking on board what other countries say could cause problems. Some negotiation will be needed so that the drafts are made reasonably acceptable to the UK’s trading partners, including the EU. But until the schedules are certified, the UK will be on legally uncertain ground, at best requiring complex legal arguments to defend the schedules’ contents. We don’t know how other countries would react.”

Clearly the UK wants to be ready with independent schedules from March 2019. However as indicated it will almost certainly not be possible to complete this exercise without committing to an Article 28 negotiation. The UK has yet to do this,, but the then Minister of State for Trade Policy Greg Hands wrote on 12 June 2018, “Should it be necessary, the UK may then move on to a second stage, and open our own Article [28] negotiations, on a UK specific goods schedule and tightly constrained to residual specific Tariff Rate Quota lines where rectification with our partners has not been finalised[13].”

A final point is worth making on expectations. Many countries feel that they made concessions to the EU during the Uruguay Round to gain access to the EU market, particularly in sensitive sectors like for beef and sheepmeat. They are therefore particularly sensitive to any hint of reduced access to EU or UK markets.

[1] https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/agric_e/ag_intro02_access_e.htm

[2] Extracted from https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/2016/08/10/hilton-beef-quota/

[3] According to a report by the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board “Most beef imports into the EU [out of TRQ] are subject to ad valorem tariffs of 12.8 percent, plus a fixed amount ranging from €1,414 to €3,041 per tonne, depending on the cut. In most cases, this tariff equates to an addition of 50 per cent or more to the value of imports, which seriously impacts on the ability of imported beef to compete with EU meat.” https://ahdb.org.uk/brexit/documents/BeefandLamb_bitesize.pdf

[4] The data is extracted by the author from information available from the European Commission at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A312%3AFIN

[5] https://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/bridges/news/eu-mercosur-launch-trade-talks

[6] See for example https://www.fwi.co.uk/business/scots-call-halt-eus-reckless-mercosur-trade-talks

[7] This work is complicated by ongoing uncertainty about the future EU-UK economic relationship. It will not be clear for some months as to whether there will be a continuing close relationship, a future FTA, or no relationship. UK and EU work at the WTO will thus have to be prepared for all options.

[8] TRQs were originally calculated on the basis of a 3 year average

[9] Where a TRQ is EO there may also be country specific TRQs

[10] New Zealand and Australia produce a similar amount of lamb – see https://www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/livestock/lamb/international-lamb-profile

[11] https://www.wto.org/gatt_docs/English/SULPDF/90970413.pdf

[12] https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/category/tariff-rate-quotas/page/2/

[13] http://europeanmemoranda.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/files/2018/06/Bill_Cash_-_8944_9254_-_12jun2018.pdf

UK Negotiating Framework

In thinking about how best to handle this negotiation we need to think of a number of factors:

- Impact of the UK’s EU negotiation;

- UK interests – what groups are particularly interested in the issue, and their views;

- International interests – the different country interests at play;

- Parliamentary oversight – what is the role for Parliament in this process.

The Impact of UK-EU Negotiations

The future relationship between the UK and EU is a key issue in future EU and UK agriculture policy, in a rather binary way. Should a tariff and quota free approach continue as part of a frictionless trade relationship then there is a possibility for joint TRQ management, at least in the short term, and EU / UK trade need not affect the setting of future TRQs. Should this not happen, there is a major challenge for both UK and EU TRQs, as the following example illustrates.

In 2017 total EU imports of beef from countries outside the bloc totalled 196,000 tonnes[1], the vast majority filling the EU’s TRQs. UK exports of beef to the rest of the EU in 2015 were approximately 91,000 tonnes[2]. Equally the UK currently imports 224,000 tonnes of beef a year from the rest of the EU. In particular the nature of cross-border supply chains in Ireland currently sees meat and cheese cross the UK / Ireland border more than once as it is processed[3]. Clearly the need to account for this trade in revised EU and UK TRQs would mean significant changes, otherwise the the existing EU-UK trade could crowd out all other countries to devalue existing Erga Omnes EU and UK TRQs.

Domestic interests

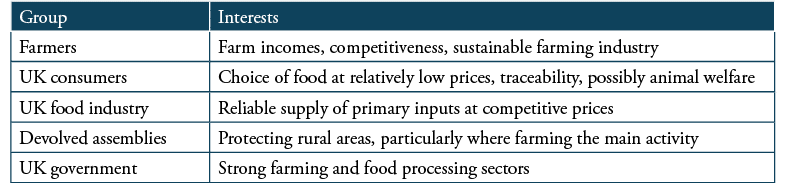

The UK Government has been carrying out limited consultation with some domestic interest groups regarding the splitting of TRQs. The following UK groups have a significant interest:

There will always be tensions in managing all of these interests. Traditionally agriculture is a strong defensive interest for many countries in trade policy, and we can expect pressures on the UK government for the same to be the case. We discussed in the ECIPE report ‘Assessing UK Trade Policy Readiness[4]’ the example of Welsh farmers and lamb imports from New Zealand. This could equally apply to significant changes to TRQs.

Equally consumers and the significant UK food industry want to maintain their choice, and obtain quality at competitive prices. It is interesting to note though that representatives of these groups tend not to call for an end to the tariffs and TRQs protecting UK farmers. Rather they seek to emphasise the importance of quality and certainty of supplies. On the domestic front one could therefore see how an agreement could be reached.

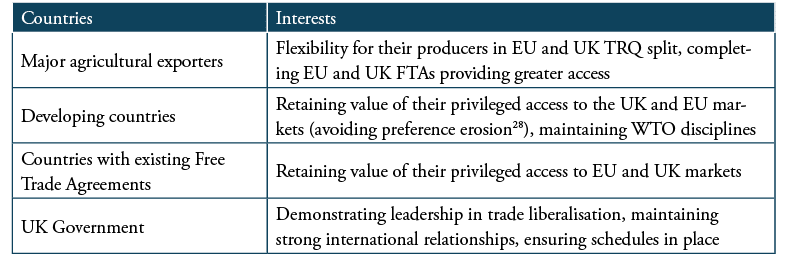

International interests

In the case of the UK splitting TRQs we can identify the following major interests.

It will probably be more difficult to satisfy these interests than domestic ones in UK TRQ negotiations. Major agricultural exporters already have a number of issues with the EU around TRQs and Sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regulations[6], and this split is a chance to make progress on these with the EU, and set a new framework with the UK. Balancing different country interests, alongside developing country interests, in the context of the UK government’s interest in being a leader in trade liberalisation, will be challenging.

Parliamentary processes

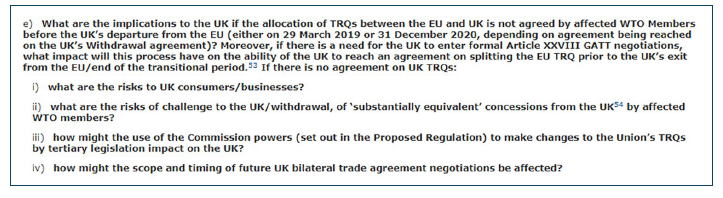

The UK government is not obliged to share information regarding their own trade negotiations with Parliament. However they do have to share information on EU negotiations while we remain a member, and it was for that reason the EU Scrutiny committee of the House Commons has been considering the issue of the TRQ split[7]. It was to this committee that the Minister wrote the letter referred to in Section 3, which led to the committee raising pertinent questions such as those below:

Given the importance of the issues being discussed, and the negotiation that has already begun, it is simply unsustainable that the only formal mechanism available for Parliamentary scrutiny is through the EU Scrutiny Committee. Significant issues that are being discussed, which will affect the UK for years to come. These must be discussed in Parliament in some way.

The plans brought forward by the Department for International Trade on 16 July 2018[8] do not address negotiations taking place at the WTO. We would therefore suggest that as a matter of urgency the Government makes time for Parliament to consider the trade negotiation on TRQs that has already started. We will return to the issue of how this could happen in the next section.

[1] http://beefandlamb.ahdb.org.uk/market-intelligence-news/eu-beef-quotas-back-limelight/

[2] International Meat Trade Association, ibid

[3] Tony Connelly, Brexit & Ireland, https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/307090/brexit-and-ireland/ see for example Chapter 5

[4] https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ECI_18_UKTradePolicy_4_2018_LY03.pdf

[5] Preference erosion occurs when tariff reductions for developed countries mean the competitive advantages provided by unilateral tariff reduction for developing countries are reduced

[6] The dispute over the EU’s banning of beef treated with hormones is a primary example. The UK will have to decide what approach to take, given that to maintain the ban will be to be in breach of WTO rules, while to lift it will potentially have impacts on the UK market and supply chain.

[7] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmeuleg/301-xxxi/30108.htm#_idTextAnchor020

[8] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/liam-fox-delivers-parliament-and-the-public-a-central-role-in-post-brexit-uk-trade-agreements

Reaching an Agreement

The criteria for the UK’s TRQ approach at the WTO, based on previous sections, should be to be trade liberal, balance farmer and consumer interests, and to be fair internationally. Given the current approach will be rejected by other countries, what other options could there be?

The first important point to make is that trying to perfect the TRQ split numbers is not worth the effort. Robust numbers on the re-export trade do not exist, and even completely accurate numbers will not make up for the loss of flexibility, complaints about existing TRQs, and the UK’s desire to take a more trade liberal path.

A number of options have been suggested, and it is possible than a combination of these could be used. These options are:

- Joint management of the TRQs by UK and EU;

- Removing all country specific TRQs and making all TRQs Erga Omnes;

- Increasing the TRQs through each of the UK and EU taking on the same TRQ, or by a smaller amount;

- UK allowing all imports at the reduced tariff for agricultural produce, and / or decreasing applied tariffs for out of quota imports.

Below we briefly examine these options, noting that we have not carried out detailed economic analysis. Such analysis would be required for any policy proposing dramatic changes to TRQs where there is also UK production, or the risk of significant preference erosion. Equally should the UK and EU’s future economic relationship not include free trade in agricultural produce a full WTO negotiation under Article 28 is inevitable, since otherwise existing TRQs would be highly distorted, as already discussed.

Joint management of TRQs: For as long as the UK and the EU are linked together in a close economic relationship where frictionless trade continues between them there is a possibility that TRQs could be managed in a joint manner. This would solve some of the issues that both the UK and EU face. However we cannot envisage a long term solution based on such joint management, as the UK would want an equal say, and the EU is unlikely to accept this even for historical quotas. Indeed as the Commission said recently in the INTA Committee, this possibility is ruled out in the long term because the UK has made clear that it wants to leave the customs union. It is possible though that such joint management could be used in the short term while a longer term deal is developed, assuming that the EU and UK succeed in signing a Withdrawal Agreement with implementation period.

Removing all country specific TRQs: A mildly liberalising move for the UK would be to remove country specific tariff quotas (CSTQs) and allow all countries to supply existing TRQs. This would remove some obvious anomalies both between countries and in the way some CSTQs are very low once split. This could be resisted by those countries who may perceive themselves to relatively lose out from this, and consumers may not be happy that overall levels of agricultural protection were being kept. Conversely it should be welcomed by UK farmers who would continue to be protected, and is in line with WTO Most-Favoured Nation principle of equal treatment. Whether the option would be acceptable in a negotiation is unknown, particularly as we assume the EU will seek to keep existing CSTQs and adjust where necessary. However it is an option that should be seriously considered as potentially more straightforward than adjusting individual CSTQs.

Increasing TRQs: At an early stage stage in TRQ discussions a suggestion was made that the EU and UK simply each take on the full amount of TRQ currently offered by the EU[1]. As a way of ensuring that there were no international losers this would work, and would demonstrate trade liberalisation, but it would be a major step that may have the potential to threaten domestic interests and production. Where there is no domestic supply it might be reasonable, albeit at the cost of removing flexibility in future bilateral agreements. Where there is it would be reasonable to expect TRQs to be increased on top of the split currently calculated. This approach could also be the starting point in the situation that UK-EU trade needs to use WTO TRQs because there is no bilateral agreement.

Remove TRQs and / or decrease tariffs: The most liberalising step of all would be to remove some or all TRQs, by charging all imports at the reduced tariff, or decrease tariffs outside of the TRQ. EU prices are typically higher than world prices due to tariffs, and this had led some to suggest removing all tariff protections[2]. This could be easier where there is no UK production, and for other products either the tariff could be reduced or TRQ increased. However such steps would need to be taken in close consultation with domestic producers and consumers. In particular the food industry do not wish to see risks taken with domestic production which is crucial for their own outputs. We would not expect to see the EU taking such an option, which could increase the incentive on the UK to demonstrate greater liberalisation.

Recommended next steps

The EU has already recognised the need to carry out a full WTO negotiation on revised TRQs, and we expect the UK to follow notwithstanding the recent remarks of Liam Fox. The UK Parliament has only has so far only had sight of the government’s plans because of the requirements to scrutinise EU activities, which is something to be addressed.

We would suggest the following steps:

- Announce that given the likely opposition to our proposed rectification approach we intend to also start a formal Article 28 process on TRQs;

- Publish a short consultation document (Green Paper or similar) on the issue, inviting interested groups to come forward with views on the best way forward, accompanied by some Parliamentary debate;

- Seek an arrangement to jointly manage the current TRQs in the short-term, at least during any implementation period with the EU until 2020, if this is not possible the initial asserted schedules should at least be on an Erga Omnes rather than CSTQ basis;

- Carry out further detailed analysis with the aim of producing a package that is overall liberalising yet protective of UK interests and international relations, and importantly does not threaten developing countries with preference erosion.

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/08b5d3bc-997a-11e7-a652-cde3f882dd7b

[2] See for example https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/aug/01/post-brexit-britain-phase-out-tariffs-food-thinktank

Conclusion

The UK government faces a major challenge discussing the Withdrawal Agreement and a future economic relationship with the EU, as well as ensuring that international treaties agreed as part of the EU continue to apply to the UK after our departure from the EU. In this context it is understandable that a complex technical issue such as the splitting of Tariff Rate Quotas at the WTO has not received much attention.

For a UK government that aspires to take a leadership role in global trade liberalisation at the WTO, however, the lack of focus that has been given to splitting TRQs must be corrected. The UK’s initial approach has caused concern with potential future partners such as Australia, New Zealand, and the US, failed to take liberalising steps when to do so could send a powerful message about the UK’s future priorities, and potentially will lead to problems for the UK food and drink industry.

It is welcome that the government is likely to change course, and there are options available which would deliver greater benefits than the current approach. The likelihood of a short term continuation of the customs union between the EU and UK can provide extra time for the issue to be resolved. Equally the need to be prepared for different future relationships between the EU and UK should also focus minds. Opening up a domestic consultation and publishing more details would be a very good first step.

Ironically the EU has been more open than the UK to a renegotiation, even though their highly protective agricultural policies have often been criticised. As the larger player their approach to launching a negotiation should be welcome, and this could also provide the opportunity for them to show some liberalising intent, not least as some of their remaining TRQs will be significantly reduced, and it may be harder to defend some of the more skewed TRQs between countries. In the event of there being no deal between EU and UK than maintains tariff and quota free trade this renegotiation will obviously become more significant.

As the UK’s first serious trade negotiation in years many will be watching to see how the UK government performs in negotiating at the WTO, and how they handle the debate domestically. At this stage we see a stuttering start, but this could ironically be the opportunity needed to get on the right track and set a positive path for our future trade policy.