Europe and South-East Asia: An Exercise in Diplomatic Patience

Published By: Hanna Deringer Hosuk Lee-Makiyama

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements South Asia & Oceania

Summary

- The EU is hoping to revive the negotiations for a region-to-region agreement with the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), but few trading partners have faced such inauspicious fate as its members.

- The trade agreement with Singapore is concluded but remains unsigned and the EU Member States do not seem to be in a hurry to ratify the EU-Vietnam agreement due to the prospects of rejection by the European Parliament over labour issues.

- There is a proposal by the European Parliament to effectively stop the use of palm oil in biodiesels under the new Renewable Energy Directive (RED-II), which has caused Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand to threaten trade retaliation against multiple EU exporters and the termination of both bilateral and regional trade negotiations.

- Given existing jurisprudence any such differentiated treatment or selective exclusion of one crop would not comply with WTO law, exposing the EU to a time-consuming WTO dispute.

- Moreover, military rule in Thailand, reports of human rights violations in the Philippines under President Duterte or atrocities in Myanmar will inevitably complicate both bilateral and EU-ASEAN negotiations.

- In Europe, much of the policy work undertaken in the current political term is dedicated to restoring the mandate and win back public trust for trade policy. The EU is weakened politically and has little wriggle room for concessions internally. The EU is demanding more, while offering less, in its international negotiations.

- The European Parliament shifts EU trade policy towards unilateral and short-term interests rather than a trade policy that could enable long-term political reforms and support the EU’s long-term geo-economic interests.

- Europe’s engagement with the ASEAN countries and the promotion of WTO rules, human rights and sustainability calls for a long-term approach which requires patience.

Excellent research assistance by Cristina Rujan is gratefully acknolwedged.

The Diplomacy of Patience: South-East Asia and Europe

Few of Europe’s trading relations have faced such an inauspicious fate over so many intricate political complexities as the EU’s relations with the countries of South-East Asia. The EU’s bilateral negotiations with Singapore were concluded after four years of negotiations in October 2014, but the deal remains unsigned.

Instead, the agreement was deferred to an opinion of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) – a decision which did not only leave the Government of Singapore nonplussed, but also unleashed the ongoing debate on the division of investment competences between the EU and its members.

Similarly, the EU has made little attempt to ratify its agreement with Vietnam, agreed in December 2016. The Commission has come to terms with the reality that it would face an uphill battle in the European Parliament over Vietnam’s labour practices – including practices that were already known to the EU before the negotiations were concluded, and even before talks were opened.

Negotiations with Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand have faced political difficulties or diplomatic spats over EU and national regulations (e.g. various attempts of European countries to legislate against palm oil), or military coups. Several attempts have also been made to revive the region-to-region negotiations between the EU and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) since it came to a halt in 2009 – the first-ever negotiation failure for both trading blocs.

Whether the approach is bilateral or regional, the EU trade talks with the South-East Asian countries have been an exercise in diplomatic patience and one of many contrasts. The pragmatic and outward looking countries in South-East Asia have signed twenty or more FTAs – including ‘impossible’ deals like China, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – by keeping a strict, business-like focus on what’s actually doable.

In contrast, Europe looks for grand accomplishments and tries to change the Asia-Pacific – the centre court of world trade – which policymakers may not always have had the curiosity or patience to understand. In this regard, Europe remains a romantic idealist, often set out to achieve the impossible.

As several of the bilaterals (as well as the EU-ASEAN agreement) will be heading towards fresh negotiations or talks in 2018, this paper looks towards the difficulties involved, and what it may take to break the stalemate. It is too simplistic to blame the failure on various shortcomings or unappealing practices of our counterparties. This approach ignores the whole point of economic diplomacy: It’s a choice to engage the world for what it really is, rather than use that reality as an excuse to disengage from the wider world.

What is at Stake

Necessity borne out of China

The idea that the Asian counterparts are always the demandeurs of every trade agreement and that the attraction of duty-free access to the Single Market gives Europe invincible powers has been disproved many times over. Europe can drive a hard bargain for what it puts on offer in trade talks – but the idea that Europe could always walk away from any negotiation table ignores the fact that the EU is running short of negotiation partners that are large enough to significantly impact its economy.

Due to its structural problems with low domestic growth and a high export dependency, Europe is bound to seek new growth from overseas markets to address its declining industrial utilisation rates – but only a few economies are large enough or sufficiently fast growing to have a meaningful impact on Europe’s GDP.

The EU has successfully concluded FTAs with medium-sized economies like Korea, Canada or Chile, but given the sheer size of the EU economy, only an agreement with the world’s top three economies or another regional bloc could make an impact on EU GDP. When the EU disembarked on its bilateral strategy in 2006, it deliberately chose to forego China, opting for trying to open up slower growing (but democratic) India. Upon the failure of that venture, the EU moved to the United States through the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) in 2013 – and with its demise, it finally opened up negotiations with Japan, the world’s third largest national economy, and the EU-Japan economic partnership agreement was finally signed in 2017.

As it stands, Europe has only two paths forward in Asia after Japan. It could kowtow to what some see as inevitable: The politically arduous and controversial EU-China trade agreement. The other alternative is the South-East Asian economies either in a package, preferably within the framework of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), or in multiple bilaterals.

Europe’s export-driven economies (and Germany in particular) have remained the largest investor in the ASEAN region in absolute terms, accounting for one-third of all inward FDI flows,[1] but simultaneously developed a disproportionate dependency on exports to China – with all the volatility and political risk it entails.

Engaging the ASEAN countries is a project consisting of many elements. ASEAN is a grouping that ranges from a services-driven high-income economy like Singapore, to a developing country based on natural resources, like Myanmar. The GDP per capita ranges between US$ 54,000 to a mere US$ 1,300, a ratio of forty to one (compared to thirteen to one between the richest and the poorest EU country).[2]

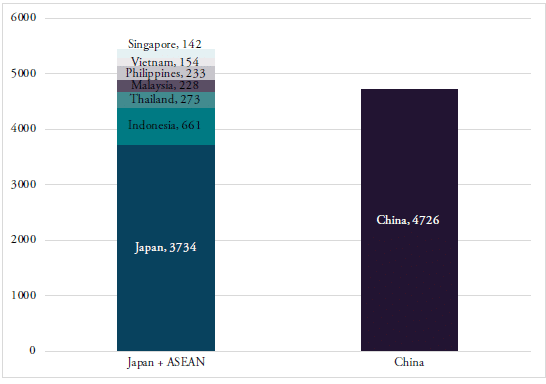

This is precisely one of the reasons the EU must engage with the wider Asia-Pacific region: The chain of islands covered by the EU FTAs, stretching from Hokkaido to Sumatra, offers a variety in resources, labour specialisation and nearly US$ 5 trillion in demand, which is only eclipsed by China in terms of size and diversity. However, this long-term economic imperative does not necessarily translate into a political commitment in the short-term.

Figure 1. Final consumption (constant 2010 million US$) of Japan, ASEAN and China

Bilateral and regional approaches hang together

Obviously, with such diversity amongst ASEAN members and varying level of ambition, one size cannot fit all. Liberalisation with the ASEAN economies cannot be built on the same template if an optimal outcome is to be found for each of the countries, while the capability to negotiate and implement advanced commitments on regulatory matters differs as well.

In 2007, the EU and ASEAN member states started negotiating a region-to-region FTA but talks stalled in 2009 due to what some even called ‘insurmountable economic and political differences’,[3] and the EU moved to negotiating bilaterally with individual member states of ASEAN.

In bilateral negotiations with individual countries, the EU could abandon those countries with considerable humanitarian concerns (as was the case of Myanmar under a martial regime.). There was a belief that key economic markets could be dealt with easier in bilateral FTA talks. Also, due to the nature of their integration, the ASEAN countries had a common position on matters concerning goods trade, but not on services and regulatory issues of importance to the EU.[4]

In fact, there are already a number of different bilateral approaches which will coexist with the imminent restart of region-to-region negotiations:

- The six largest economies by nominal GDP – namely Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam – have opened negotiations with Europe.

- Three of the countries – Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar – already qualify for one-way duty-free quota-free trade for least developing countries under the Everything But Arms (EBA) program. A bilateral investment agreement was also in the works with Myanmar.

- Meanwhile Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines can fall back on their market access to the Single Market under the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) if their bilateral FTA negotiations do fail.

Obviously, the bilateral and regional approaches are complementary. Similar to other regional agreements (such as the TPP), the architecture of the ASEAN-EU agreement would have a common umbrella of rules and disciplines, while market access schedules (in particular thorny areas such as tariff-rate quotas and public procurement or services) would be negotiated bilaterally with each country. Similarly, countries like Japan, Korea and Australia/New Zealand, who have regional FTAs with ASEAN, use bilaterals to update the baseline commitments on rules in their regional agreements.

Demandeurship of the negotiations

Only a few may recall that the start of region-to-region talks between the EU and ASEAN dates back to the 1970s when an informal dialogue started, which was followed by parliamentary and ministerial dialogues in the 1980s and 1990s,[5] before the formal FTA talks were launched in 2007.

Throughout the process, Brussels always assumed that Asian counterparts were always the demandeurs of each negotiation, which is not necessarily the case. ASEAN as a collective entity is already the fourth largest trading partner of the EU,[6] growing faster than Europe’s stagnant trade with China or India, namely at the rate of 6.8% per year on goods and 10.6% in services since 2010.[7]

Asia is also turning its focus to intra-regional initiatives like the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which created a single market of 600 million consumers, or agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Thus, for the EU, deep agreements with countries like Malaysia, Vietnam or Singapore are more about regaining the economic and regulatory power it has lost in the region.

Therefore, Europe has much more to lose in case it fails to open up the Asian economies bilaterally or regionally. The “no deal” scenario leads to a loss of comparative advantage for the EU vis-à-vis regional competitors like China, Japan or the US. Meanwhile, the ASEAN countries are turning their attention to more compatible and apolitical partners within their own region and could simply default back to one-way alternatives, such as GSP or EBA.

Unlike in the collective trade policy making process in the EU, ASEAN members do not exercise the same level of peer pressure in the case of dissenting opinions in trade negotiations. Since ASEAN trade policy making is more autonomous, each of the ASEAN countries can walk away more easily from the negotiation table and therefore holds an effective veto against the EU-ASEAN agreement if it perceives the agreement violates its core interests. Therefore, the interests of some of the ASEAN member states will be discussed more closely in the following sections. Addressing these issues is critical for Europe’s prospects of concluding FTAs with not just ASEAN, but developing economies overall.

[1] Own calculations based on ASEAN stats data.

[2] World Bank, World Development Index, 2016

[3] Loc Doan, X. (2012), Opportunities and Challenges in EU-ASEAN Trade Relations, EU-ASIA Centre: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.eu-asiacentre.eu/pub_details.php?pub_id=60.

[4] Meissner, K. L. (2016), A case of failed interregionalism? Analyzing the EU-ASEAN free trade agreement negotiations, Asia Europe Journal, 2016, vol. 14, issue 3, 319-336, p. 332.

[5] Ibid., p.319.

[6] Own calculations based on data from Eurostat.

[7] Ibid.

Deadlock over Palm Oil Bans

Current concerns of Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia

Palm oil accounts for over 30% of the world’s vegetable oil production and is present in a wide variety of consumer products. The importation of palm oil produced by Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia is currently the most immediate and most urgent issue that needs to be resolved between the EU and the ASEAN countries, before any of the trade talks may progress.

Indonesia and Malaysia account for 85% of global palm-oil production,[1] accounting for a considerable share of their exports to the EU, 14% and 6%respectively.[2] But the production of palm oil has played a role in elevated levels of deforestation of natural rainforests in South-East Asia.[3]

European Parliament’s own research claims palm oil is an efficient and cost-effective product that requires only one-tenth as much land, one-seventh as much fertiliser, one-fourteenth as much pesticide and one-sixth of the energy to produce the same quantity of oil,[4] which explains its popularity in developing countries with limited resources or where only a small amount of arable land is available.

On the other hand, experts from NGOs have alleged that biodiesel (and in particular palm oil-based) is “a cure worse than the disease” as a renewable source of energy, claiming the production of biodiesel generates up to three times more greenhouse gases than burning fossil fuel.[5] Up to 60% of Europe’s palm oil consumption is supposed to be used for fuels rather than food production.[6]

While many Members of the European Parliament take genuine issue with deforestation in Asia, their constituents are also hosts to powerful agro-industrial commercial interests that produce biofuels from local crops. The major party groupings in the European Parliament have called for a complete phase-out of palm oil (but not of other vegetable oils) as a transport fuel in the ongoing revision of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED-II). Their proposal suggests that the contribution of biofuels produced from palm oil should not be included for the purpose of calculating a Member State’s gross final consumption of energy from renewable energy sources, in effect ending the use of palm oil as a renewable energy source in the EU.

Biofuels have already led to numerous disagreements between the EU and overseas producers, including the palm oil producing countries in South-East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. The WTO Appellate Body has ruled against antidumping duties imposed by the EU on biodiesel from Argentina and Indonesia,[7] which the complainants claimed were aimed at protecting European oilseed growers, rather than the environment.

In 2016, the French Parliament contemplated a proposal for a biodiversity bill with a ‘Nutella tax’ on palm oil, which is also an ingredient in the chocolate spread. The bill was eventually dropped as it fell afoul of WTO rules. Also, Malaysia and Indonesia exercised political pressure on France by threatening to freeze the bilateral FTA talks and purchases of French aircraft, satellites and other exports.[8]

Europe’s WTO compliance

Arguably, environmental protection and trade rules are uneasy bedfellows, a number of WTO disputes have struck down on discriminatory features in various environmental laws throughout its history.

For example, in the US—Shrimps/Turtles dispute,[9] the US was found to be discriminating by imposing a different set of transition periods for certain developing countries, depriving them of non-discriminatory (‘most favoured nation’) rights.[10] Also, the US Clean Air Act imposed a different set of rules on imported gasoline than it did for domestically equivalent products,[11] failing to provide national treatment for imported ‘like’ products in respect of all laws, regulations and requirements.[12]

A Panel also ruled in favour of the European Communities in its complaint against a US certification scheme on “dolphin-safe” tuna which automatically assumed that Dutch canned tuna was harmful by default, just because EU laws were different, and arguably laxer.[13] The legal conclusion was that Dutch canned tuna could be of a higher environmental standard than the Dutch laws actually require.

It is easy to see the similarity between the proposed revisions under RED-II and WTO case law. It follows from the WTO jurisprudence that any advantage afforded to a WTO Member – such as contribution to renewable energy targets – must be afforded to any ‘like’ products from any other member. Moreover, the WTO jurisprudence is clearly incompatible with laws that assume that a particular product, or a country of origin, is always harmful to the environment: Environmental laws must be based on a scrutiny of underlying production processes of each product.[14]

Thus, any certification scheme for sustainability criteria for biodiesel made from palm oil in Asia must also cover ‘like’ products (such as biodiesel made from seeds grown in Europe) which must also be examined in an identical manner. Otherwise, the EU directive is a market access violation which can be challenged in a WTO dispute.

In conclusion, any differentiated treatment or selective exclusion of one individual crop, as preferred by the European Parliament in the case of palm oil, will not comply with WTO law given the existing jurisprudence. This would remain the case even if the European Parliament’s current text was replaced with another text that retained the same end-effect of differentiated treatment based on origin and product, rather than process.

Of politics, ethics or optics

It is easy to see historical connotations and a political dimension to the dispute on palm oil: Developing countries might argue that if ‘like’ products are not scrutinised according to the same standard, it allows the wealthy industrialised countries to take action against developing countries on the grounds of deforestation, without considering the deforestation that occurred perhaps centuries ago to create arable land in Europe.

In the emerging countries (including South-East Asia), some of which are Europe’s former colonies, it is a recurring narrative of how the industrialised West seeks to monopolise the trade in crops, leading to some indignant statements of ‘crop apartheid’.[15] Given the Dolphin-Tuna case, it reinforces the view of the one-sidedness of international rules – of how Europe often fails to live up to the rules it gainfully imposes on others.

From the perspective of the European Parliament, however, it seems self-evident that it has the right to regulate what it deems as a renewable source of energy. Moreover, the overarching objective of EU engagement with the world must be to advocate its values, where sustainability is one of the foremost objectives of EU soft power.

The legislative process in the EU is also complex, leaving it unclear what the legislative outcome will be. As the European Commission and the Member States often point out: “the complex legislative process is yet to be finalised with many amendments and deletions to be foreseen”.[16]

However, the reality of trade negotiations are much more simple and straightforward than the science of deforestation or EU legislative processes. For example, 650,000 voters in Malaysia (dispersed over some of the politically most important states) receive their livelihood from oil palm cultivation, which they see as fundamental to their economy.

It is therefore unlikely that the Malaysian and Indonesian governments could simply cede on the issue, as this is a matter of principles as well as optics: The elected officials of Indonesian and Malaysian governments cannot justify the time-consuming negotiations with an entity that excludes one of their key products at the outset. Nor are they in a position to trade-off their local industries at a later stage, especially as their constituents feel the case is a flagrant discrimination.

In conclusion, the issue at hand is not about the merit and demerits of palm oil, or whether the public officials in Asia should understand and respect how the EU operates under ordinary legislative procedure. Asian counterparts have domestic politics too, with stakeholders and ‘red lines’ which they cannot cross. They have voters and state representatives who demand to know why their government should negotiate a trade agreement with the EU who bans their key exports – and how they could expect the EU to negotiate in good faith.

The possible outcomes are therefore only two: Either the EU develops a RED-II that is non-discriminatory and complies with the WTO rules in order to move forth with its long-term geo-economic interests in ASEAN; or the EU violates the WTO rules (perhaps even knowingly), exposing itself to a time-consuming trade dispute over palm oil, while the FTA talks remain effectively on hold. Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand have warned they will retaliate against EU exports on inter alia milk powder, defence contracts and aircraft.[17] The reaction of the ASEAN countries is not too dissimilar to Europe’s own response to recent US steel tariffs.

[1] The Economist Intelligence Unit (n.a.), Palm oil and deforestation, Food Sustainability Index, Blog, accessed at: http://foodsustainability.eiu.com/palm-oil-and-deforestation/

[2] UN ComTrade, 2015.

[3] 11-16% of deforestation is attributed to palm oil cultivation, see Barthel, Jennings, Schreiber, Sheane, Royston, Study on the environmental impact of palm oil consumption and on existing sustainability standards, European Commission, DG Environment, February 2018, acessed at: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/forests/pdf/palm_oil_study_kh0218208enn_new.pdf

[4] European Parliament Research Service, Palm Oil: Economic And Environmental Impacts, Febrary 19, 2018, accessed at: https://epthinktank.eu/2018/02/19/palm-oil-economic-and-environmental-impacts/

[5] Crisp, J. (2016), Biodiesel worse for the environment than fossil fuels, warn green campaigners, Euractiv, April 26, 2016, accesed at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/climate-environment/news/biodiesel-worse-for-the-environment-than-fossil-fuels-warn-green-campaigners/.

[6] Transport & Environment (2016), Cars and trucks burn almost half of all palm oil used in Europe, May 31, 2016, accessed at: https://www.transportenvironment.org/press/cars-and-trucks-burn-almost-half-all-palm-oil-used-europe.

[7] WTO, European Union—Antidumping measures on biodiesel from Argentina, DS473; WTO, European Union—Antidumping measures on biodiesel from Indonesia, DS480.

[8] Dreyer, I., (2016), French National Assembly drops ‘Nutella tax’ plans, Borderlex,

accessed at: http://borderlex.eu/french-national-assembly-drops-nutella-tax-plans/.

[9] WTO, US—Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products, DS58.

[10] GATT Art I:1

[11] WTO, US—Standards for reformulated and conventional gasoline, DS2.

[12] GATT Art III:4

[13] WTO, US—Measures Concerning the Importation, Marketing and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products, DS381.

[14] supra 15, 16, 17

[15] Reuters (2018), European move to ban palm oil from biofuels is ‘crop apartheid’ -Malaysia, January 18, 2018, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/malaysia-palmoil-eu/european-move-to-ban-palm-oil-from-biofuels-is-crop-apartheid-malaysia-idUSL3N1PD1NJ.

[16] Delegation of the European Union to Malaysia (2018), EU’s Revised Renewable Energy Directive and Its Impact on Palm Oil, Press Release, January 18, 2018, accessed at: https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/malaysia/38389/eus-revised-renewable-energy-directive-and-its-impact-palm-oil_en; also Delegation of the European Union to Indonesia (2018), accessed at: https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/indonesia/38379/eus-renewable-energy-directive-and-its-impact-palm-oil_en

[17] Reuters (2017), Indonesia warns may bar EU milk powder if palm oil sales restricted, November 3, 2017, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/indonesia-palmoil-eu-dairy/indonesia-warns-may-bar-eu-milk-powder-if-palm-oil-sales-restricted-idUSL4N1N91F1.

Fundamental Rights

The 2014 military coup of Thailand

While it is a popular view that trade and politics should be delinked, it is unavoidable that some of the bilateral negotiations have been halted and restarted over a change in political legitimacy or direction of the counterparts. This is an inevitable factor in bilateral negotiations with emerging countries but is also a matter which determines the outcome of region-to-region negotiations.

The EU expressed concerns about (and acts upon) detrimental developments in the political systems through its coordinated actions in foreign policy, strategic partnerships and other instruments such as overseas aid. The EU also had a number of concerns about the human and labour rights situation in some of the ASEAN countries. But when a coup occurs during the course of a trade negotiation, it poses a dilemma for the EU: Should it continue its engagement, or terminate the negotiations?

In 2014, a military coup took place in Thailand, and since then the democratic process, human rights and fundamental freedoms have been severely hampered. General elections aiming to restore democracy were scheduled for 2018, but they have yet again been postponed until early 2019, following a recent change in the election law earlier this year.[1]

At the onset, it should be noted that the EU FTA negotiations with Thailand were not derailed exclusively due to the EU’s concerns about the non-democratic leadership in Thailand. Before the coup, the EU finalised a political Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) in 2013, which it refuses to sign until a democratically elected government is restored.[2] Negotiations for an FTA, which also started in 2013, are also halted.

In December 2017, the European Council recognised recent developments by the Thai authorities towards democratic elections and announced to resume a “gradual political re-engagement” with the country aiming at a “meaningful dialogue on issues of mutual importance”.[3] In that context, the Council also asked the Commission to consider the possibility to resume the FTA negotiations. However, after the further postponement of the general elections in Thailand in 2018, it is questionable how far this offer will be upheld. In addition, the European Parliament has been vocal about human rights violations and democracy in Thailand. [4] The question is, therefore, whether and what requirements it might set out for unfreezing and continuing the negotiation processes.

Thailand, on the other hand, is reported to pursue a one-by-one approach aiming to tighten its strategic partnerships with individual EU member states.[5] Yet, this approach will not provide Thailand with the same opportunities as a direct dialogue with the EU. Also, EU foreign policy and its stance on human rights is a bottom-up process of Member State positions, rather than an autonomous EU policy area. It is doubtful that the key member states have different views on the democratic process and human rights in Thailand.

Human and labour rights stalling the Vietnam FTA

In addition to sudden changes in government and military rule, human and labour rights in some ASEAN countries continue to cast a shadow. The most prominently discussed case is the concluded agreement with Vietnam whose ratification hinges on the question of whether the agreed text needs to be changed following the ruling of the ECJ. The agreement has also been criticised heavily over human and basic labour rights violations in Vietnam.

In the context of the EU-Vietnam FTA negotiations the European Parliament – eagerly spurred on by interest groups, NGOs, and competing industries – has voiced concerns over the recognition and implementation of human rights, especially regarding the freedom of expression and core labour rights in Vietnam.[6] In response to these concerns, the European Parliament and the European Ombudsman requested that the European Commission carry out a human rights impact assessment, which the European Commission refused.[7]

The Agreement has been signed by the European Commission, but it has not yet entered the ratification process because it is undecided if it should be ratified as a mixed agreement or modified to an EU competence only agreement. However, a stumbling block is also the European Commission’s fear that the European Parliament could veto the ratification of the agreement.[8]

A basic question underlying the discussion is whether to separate trade and human-rights policy-making and include them in different agreements or how far human (and labour) rights requirements should also impact (or be regulated) in trade agreements. Different EU institutions seem to have different views on that, resulting in an “inter-institutional conflict on the objectives of the trade agreement”[9].

Since 2009, it is the EU’s preference to link trade agreements to human rights provisions in a framework cooperation agreement such as the Political Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with Vietnam.[10] A legal link between the two agreements provides for the possibility to take “appropriate measures” (including the suspension of the FTA) in case of human rights violations by one of the two parties. Labour and environmental standards, in contrast, are addressed in the FTA’s Sustainable Development (TSD) chapter.

In response to the concerns, the Commission issued a non-paper[11] and launched a dialogue process with civil society, member states and the European Parliament last year, which resulted in 15 action points on how to improve the implementation and enforcement of the EU’s TSD chapters.[12] The European Parliament, however, considers the current human rights situation in Vietnam less than ideal and threatens that the agreement could be thwarted if concerns over human rights are not addressed by the Vietnamese Government.[13]

Vietnam is keen to implement the FTA with the EU since it seeks market access to a large market after the US left TPP and to avoid its dependence on China. After going through a long negotiation process, it is difficult to understand now why the finalization of the deal is held back on the EU side. For the moment, Vietnam has only ratified five of the eight Core ILO Conventions[14], but it has committed to improving its labour rights and doing its homework under the TSD chapter in the EU FTA. Article 3.3 of the TSD chapter states that both parties “will make continued and sustained efforts towards ratifying, to the extent it has not yet done so, the fundamental ILO conventions”[15]. The Vietnamese Government has also committed in the CPTPP to implementing the 1998 ILO Declaration within a certain time frame, and the Agreement includes possible sanctions in case the parties fail to do so.[16] It is therefore difficult for the Vietnamese Government to understand how, if they commit to comply with the agreed provisions in the FTA and PCA, this does not lead to a conclusion and implementation of the trade agreement.

Other issues: the Philippines, the Rohingya atrocities

In addition, at least two more issues could arise as political impediments before any bilateral or regional agreement sees the light of day.

The first issue is the Philippines. Since President Duterte took office in 2016, he has conducted a campaign to combat drugs, criminality, and corruption in his country which has led to extrajudicial killings of thousands of people.[17] Nevertheless, on March 1st, the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between the EU and the Philippines (signed in 2012) entered into force. The PCA is taken as a reaffirmation by both parties of their commitment to principles of democracy, the rule of law, good governance, as well as peace and security in the region.

The FTA negotiations between the EU and the Philippines are also ongoing. The negotiations started in December 2015, with the first round taking place in May 2016 and the second in February 2017. In 2016 and 2017, however, the European Parliament adopted resolutions on the Philippines expressing concerns over human rights violations in the context of the anti-crime and anti-drug operations.[18]

Another recent matter which inevitably complicates EU-ASEAN negotiations is the situation of the Rohingya in Myanmar, who face serious human rights violations described by UN officials as ‘ethnic cleansing’.[19] In response, the Commission suspended the ongoing negotiations for an investment agreement and threatened to put on hold trade preferences under the EBA scheme.[20]

The objective in negotiating with developing countries

In every trade talk, the EU needs to be aware that most fast-growing developing countries are still in the infancy of developing democratic institutions and in the midst of establishing a functioning political governance with checks and balances.

Moreover, in an economic region, there will always be a few “bad apples”, i.e. countries with unappealing governments or policies. However, the European experience is also that supranational governance makes it more likely that countries do not diverge too far from the political centre and common basic rules and values.

It is perhaps self-evident that Europe cannot (and should not) accept violent or authoritarian regimes and human rights violations. However, the effectiveness of economic sanctions and punitive actions is often limited.[21] In contrast, engagement leads to economic development and internationalisation. And according to the modernisation theory of development, the economic liberties eventually lead to political liberties. If done right, it consolidates the middle class, which will demand fair redistribution, political representation and civil liberties from within.

This is clearly a balancing act and a question of when political disagreements and infringements are so grave they spill over to trade. For instance, there are countries even within the EU membership such as Poland and Hungary, whose recent political developments have called for political sanctions from their fellow Member States. Obviously, their transgressions were not grave enough for EU trade partners like Japan or the US to break off negotiations with the EU – but it is not impossible to envisage a scenario where another counterpart could have abused it in bad faith. In the world of diplomacy, there are as many shades of grey as there are recognised nations.

The EU, therefore, needs to be clear about when and where it wants to draw the line, with which countries it can continue to negotiate or not – and when to cut off regional talks due to the political situation in a minority of the member countries. Obviously, there is no clear and given answer for all situations – sanctions design always involves combining short-term punitive action and long-term benefits on civil liberties from economic engagement. But most of all, the EU must anchor its decision in this balancing act amongst its political stakeholders with a resolute resilience to stand by its judgement against excuses for protectionism.

[1] Hariraksapitak, P., Niyomyat, A. (2018), Thai vote faces delay after lawmakers amend the election law, Reuters World News, January 25, 2018, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-politics/thai-vote-faces-delay-after-lawmakers-amend-election-law-idUSKBN1FE25Y.

[2] European Commission, DG Trade (2017), Thailand, accessed at: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/thailand/.

[3] European Council (2017), Thailand: Council adopts conclusions, Press Release of 11/12/2017, accessed at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/12/11/thailand-council-adopts-conclusions/.

[4] Vandewalle, L. (2016), Thailand in 2016: restoring democracy or reversing it?, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/578931/EXPO_STU(2016)578931_EN.pdf, p. 34.

[5] Bangkok Post (2018), Thailand takes one-by-one approach to bolster EU ties, Bangkok Post, January 31, 2018, accessed at: https://www.bangkokpost.com/archive/thailand-takes-one-by-one-approach-to-bolster-eu-ties/1404766.

[6] Sicurelli, D. (2016), The EU as a Promoter of Human Rights in Bilateral Trade Agreements: The Case of the Negotiations with Vietnam, Journal of Contemporary European Research, 11(2), pp. 230-245, p. 231.

[7] Mendonca, S., Vandewalle, L. (2015), Vietnam: Despite human rights concerns, a promising partner for the EU in Asia, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/570449/EXPO_IDA(2015)570449_EN.pdf, p. 24.

[8] Dreyer, I. (2018), ASEAN: An afterthought in EU trade policy?, Borderlex on 05/03/2018, accessed at: http://borderlex.eu/trade-asean-gets-an-eu-afterthought/.

[9] Sicurelli, D. (2016), p. 237

[10] Bartels, L. (2014), The European Parliament’s Role in Relation to Human Rights in Trade and Investment Agreements, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/86031/Study.pdf, p. 12.

[11] European Commission (2017), Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), Non-paper of the Commission service, European Commission: Brussels, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/july/tradoc_155686.pdf.

[12] European Commission (2018), Feedback and way forward on improving the implementation and enforcement of Trade and Sustainable Development chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements, Non-paper of the Commission service, European Commission: Brussels, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/february/tradoc_156618.pdf.

[13] Loc Doan, X. (2017), Will Vietnam let its human rights record stifle trade with the EU?, Asia Times on September 23, 2017, accessed at: http://www.atimes.com/will-vietnam-let-rights-issues-hijack-fta-eu/.

[14] International Labour Organisation (ILO), Ratifications for Vietnam, accessed in March 2018 at: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11200:0::NO:11200:P11200_COUNTRY_ID:103004.

[15] European Commission (2016), EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement: Agreed text as of January 2016, Chapter on Trade and Sustainable Development, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/february/tradoc_154229.pdf.

[16] Nhan Dan Online (2018), CPTPP an opportunity for Vietnam to modernise labour legislation: ILO official, Interview with ILO Country Director for Vietnam, Chang-Hee Lee, accessed at: http://en.nhandan.org.vn/business/item/5928802-cptpp-an-opportunity-for-vietnam-to-modernise-labour-legislation-ilo-official.html

[17] Human Rights Watch (2018), Philippines Events of 2017, World Report 2018, accessed at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/philippines.

[18] European Parliament (2018), EU-Philippines Free Trade Agreement (EUPFTA), Legislative Train Schedule, accessed in March 2018 at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-balanced-and-progressive-trade-policy-to-harness-globalisation/file-eu-philippines-fta.

[19] Lederer, E. (2017), UN chief calls for an end to ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Rohingya Muslims as Security Council condemns violence, The Independent on September 13, 2017, accessed at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/rohingya-ethnic-cleansing-genocide-latest-aung-san-suu-kyi-refugees-burma-myanmar-un-bangladesh-a7945806.html.

[20] Dreyer, I. (2018), ASEAN: An afterthought in EU trade policy?, Borderlex on 05/03/2018, accessed at: http://borderlex.eu/trade-asean-gets-an-eu-afterthought/.

[21] See Hufbauer, Schott, Elliott, Oegg (2008), Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, PIIE, May 2008; also Portela, C. (2011), European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy.

Conclusion

A ratchet for diplomacy

The history of the EU-ASEAN dialogue walks in a circle of political goodwill, false hopes, and misfortunes. Both bilateral and regional negotiations have operated in the shadows of other major initiatives – the conclusion of the AEC or CPTPP (with Singapore, Vietnam and Malaysia as founding signatories) and negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have created a political impetus in the region but have barely been registered in the European discourse.

For the South-East Asian countries, any FTA – even with Europe – follows these three landmark intra-Asian initiatives in the list of political priorities. Similarly, it is inevitable that the much bigger EU-Japan negotiations have overtaken the FTAs with ASEAN countries. The priority given to Japan may be understandable given the near-universal support the Japan bilateral has gathered in recent months. But the lack of similar support and urgency for the already signed and concluded agreements with Singapore and Vietnam sends an unambiguous political signal too.

For instance, the former Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht decided to unceremoniously defer the Singapore agreement to ECJ for an opinion on its investment provisions. In his defence, he could only play the cards he was given under a force majeur as the popular mandate for EU trade policy was disintegrating – a fallout from which the EU is yet to recover. At the time of writing, the Singapore FTA is (figuratively and chronologically) falling further behind in the legislative calendar, while the fate of the Vietnam agreement remains unclear – the opposition from the European Parliament against the agreement is persistent, while this parliamentary session is about to come to an end.

As we have seen, however, the impediments are not about lack of political priorities. A number of practical and primarily non-trade issues are still outstanding for the negotiations: In the cases where there are grave transgressions of international law and where there were no real prospects of improvements (such as in the case of Myanmar in 2009), they were inevitable. More recent events – such as the sudden turn of events in Myanmar, Philippines or Thailand in recent years – were unforeseen, and rightfully led to a re-evaluation of whether bilateral or regional FTAs are still feasible., or whether trade liberalisation with some of the countries is still a force for long-term good.

But in other cases, such as the EU-Singapore FTA, the holdup is even unrelated to our counterpart, and something entirely of our own doing. The environmental and labour issues were also well-known factors prior to the negotiations – yet the EU agreed to open the negotiations.

In such cases, the EU expect the counterparties to be an entity with enough political stability to keep their word and able to hold together the various branches of government. There is an unspoken rule of common decency amongst trade negotiators to enforce a ratchet on introducing new trade barriers during the negotiations. Similarly, the parties should not engage in practices they deem contrary to their common fundamental values during the course of PCA negotiations.

However, some ASEAN governments, as well as the ever-evolving sui generis Europe itself, are unable to offer such political stability to its counterparts. Thus, we must deal with new serious transgressions of human rights on one hand, and on the other hand, Europe’s legislature seems to be advocating a WTO violation – contrary to the EU’s proclaimed leadership of multilateral rules in uncertain times.

Internal EU difficulties

We should, however, not discount the difficulties EU trade policy-making is currently going through. After Greece, Brexit and the crises over TTIP and CETA, much of the political trust for further economic cooperation on the EU level has been hollowed out. This has some internal and inter-institutional consequences, which have impacted the EU’s ability to move forward with an offensive trade agenda.

Firstly, it is evident from recent FTA negotiations that EU trade policy suffers from public distrust and more careful scrutiny. Recent EU ratification processes show that even FTAs with ‘benign’ partners (say Canada) could be subject to public indignation. Much of the policy work undertaken in the current political term is dedicated to restoring the mandate and winning back public trust for trade policy – through increased transparency, safeguards on sustainability issues and revising investment disputes.

In this confidence-building exercise, the EU has very little wriggle room for concessions, and expects to win on every outstanding issue. Paradoxically, the EU may by all accounts be seen as weaker politically – but at the same time, it has strong incentives towards demanding more while offering less in its international negotiations. This position becomes untenable if the EU is an equal demandeur of Asian FTAs.

Secondly, the European Parliament and certain Member States have shown impressive political brinkmanship to fill the void, going far beyond the traditional legislature with the power to ratify a treaty in an ‘up or down’ fashion. The power of their veto has been stretched to the point that they are able to redefine policies, make amendments and even signal that the FTAs must be renegotiated due to European parliamentary politics.

This leads to the third and a final point – namely that the Parliament’s involvement has changed the priorities of EU trade policy towards domestic and short-term solutions. Short-term transactional elements are always central to trade policy, but the natural limitations of terms for the legislature and zeal for publicity drive policy issues towards unilateral short-term outcomes. Outcomes like product bans, sanctions or rejections of trade agreements signal impatience. However, these are easier to grasp for the public than a long-term policy framework which enables long-term developments and political reforms that starts with establishing an influential middle class.

In conclusion, Europe’s engagement with the ASEAN countries and the promotion of a rule-based trading system, human rights and sustainability calls for a long-term approach which requires patience and compromises for the sake of long-term ideas that stretches beyond the next press release or even the next parliamentary elections.

References

Bangkok Post (2018), Thailand takes one-by-one approach to bolster EU ties, Bangkok Post, January 31, 2018, accessed at: https://www.bangkokpost.com/archive/thailand-takes-one-by-one-approach-to-bolster-eu-ties/1404766.

Bartels, L. (2014), The European Parliament’s Role in Relation to Human Rights in Trade and Investment Agreements, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/86031/Study.pdf.

Bauer, M. (2016), Boosting EU trade with South East Asia, New Direction: Brussels, accessed at: http://europeanreform.org/files/ND-report-SouthEastAsia-preview%28lo-res%29-3.pdf.

Binder, K. (2018), Driving trade in the ASEAN region – Progress of FTA negotiations, European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/595850/EPRS_BRI(2016)595850_EN.pdf.

Crisp, J. (2016), Biodiesel worse for the environment than fossil fuels, warn green campaigners, Euractiv, April 26, 2016, accesed at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/climate-environment/news/biodiesel-worse-for-the-environment-than-fossil-fuels-warn-green-campaigners/.

Delegation of the European Union to Malaysia (2018), EU’s Revised Renewable Energy Directive and Its Impact on Palm Oil, Press Release, January 18, 2018, accessed at: https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/malaysia/38389/eus-revised-renewable-energy-directive-and-its-impact-palm-oil_en.

Dreyer, I. (2016), French National Assembly drops ‘Nutella tax’ plans, Borderlex, accessed at: http://borderlex.eu/french-national-assembly-drops-nutella-tax-plans/.

Dreyer, I. (2018), ASEAN: An afterthought in EU trade policy?, Borderlex on 05/03/2018, accessed at: http://borderlex.eu/trade-asean-gets-an-eu-afterthought/.

European Commission (2006), Global Europe competing in the World, European Commission: Brussels, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/october/tradoc_130376.pdf.

European Commission (2015), The EU and ASEAN: a partnership with a strategic purpose, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, European Commission: Brussels, accessed at: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/abaf503d-fd58-11e4-a4c8-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

European Commission (2016), EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement: Agreed text as of January 2016, Chapter on Trade and Sustainable Development, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/february/tradoc_154229.pdf.

European Commission (2017), Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), Non-paper of the Commission service, European Commission: Brussels, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/july/tradoc_155686.pdf.

European Commission, DG Trade (2017), Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), accessed at: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/asean/.

European Commission, DG Trade (2017), Thailand, accessed at: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/thailand/.

European Commission (2018), Feedback and way forward on improving the implementation and enforcement of Trade and Sustainable Development chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements, Non-paper of the Commission service, European Commission: Brussels, accessed at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/february/tradoc_156618.pdf.

European Council (2017), Thailand: Council adopts conclusions, Press Release of 11/12/2017, accessed at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/12/11/thailand-council-adopts-conclusions/.

European Parliament (2018), EU-Philippines Free Trade Agreement (EUPFTA), Legislative Train Schedule, accessed in March 2018 at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-balanced-and-progressive-trade-policy-to-harness-globalisation/file-eu-philippines-fta.

Hariraksapitak, P., Niyomyat, A. (2018), Thai vote faces delay after lawmakers amend election law, Reuters World News, January 25, 2018, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-politics/thai-vote-faces-delay-after-lawmakers-amend-election-law-idUSKBN1FE25Y.

Hufbauer, Schott, Elliott, Oegg (2008), Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, Washington: Peterson Institute of International Economics.

Human Rights Watch (2018), Philippines Events of 2017, World Report 2018, accessed at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/philippines.

International Labour Organisation (ILO), Ratifications for Vietnam, accessed in March 2018 at: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11200:0::NO:11200:P11200_COUNTRY_ID:103004.

Lederer, E. (2017), UN chief calls for end to ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Rohingya Muslims as Security Council condemns violence, The Independent on September 13, 2017, accessed at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/rohingya-ethnic-cleansing-genocide-latest-aung-san-suu-kyi-refugees-burma-myanmar-un-bangladesh-a7945806.html.

Loc Doan, X. (2012), Opportunities and Challenges in EU-ASEAN Trade Relations, EU-ASIA Centre: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.eu-asiacentre.eu/pub_details.php?pub_id=60.

Loc Doan, X. (2017), Will Vietnam let its human rights record stifle trade with the EU?, Asia Times on September 23, 2017, accessed at: http://www.atimes.com/will-vietnam-let-rights-issues-hijack-fta-eu/.

Mendonca, S., Vandewalle, L. (2015), Vietnam: Despite human rights concerns, a promising partner for the EU in Asia, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/570449/EXPO_IDA(2015)570449_EN.pdf.

Meissner, K. L. (2016), A case of failed interregionalism? Analyzing the EU-ASEAN free trade agreement negotiations, Asia Europe Journal, 2016, vol. 14, issue 3, 319-336.

Nhan Dan Online (2018), CPTPP an opportunity for Vietnam to modernise labour legislation: ILO official, Interview with ILO Country Director for Vietnam, Chang-Hee Lee, accessed at: http://en.nhandan.org.vn/business/item/5928802-cptpp-an-opportunity-for-vietnam-to-modernise-labour-legislation-ilo-official.html

Reuters (2017), Indonesia warns may bar EU milk powder if palm oil sales restricted, November 3, 2017, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/indonesia-palmoil-eu-dairy/indonesia-warns-may-bar-eu-milk-powder-if-palm-oil-sales-restricted-idUSL4N1N91F1.

Reuters (2018), European move to ban palm oil from biofuels is ‘crop apartheid’ -Malaysia, January 18, 2018, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/malaysia-palmoil-eu/european-move-to-ban-palm-oil-from-biofuels-is-crop-apartheid-malaysia-idUSL3N1PD1NJ.

Sicurelli, D. (2016), The EU as a Promoter of Human Rights in Bilateral Trade Agreements: The Case of the Negotiations with Vietnam, Journal of Contemporary European Research, 11(2), pp. 230-245.

The Economis Intelligence Unit (n.a.), Palm oil and deforestation, Food Sustainability Index, Blog, accessed at: http://foodsustainability.eiu.com/palm-oil-and-deforestation/.

Transport & Environment (2016), Cars and trucks burn almost half of all palm oil used in Europe, May 31, 2016, accessed at: https://www.transportenvironment.org/press/cars-and-trucks-burn-almost-half-all-palm-oil-used-europe.

Vandewalle, L. (2016), Thailand in 2016: restoring democracy or reversing it?, European Parliament: Brussels, accessed at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/578931/EXPO_STU(2016)578931_EN.pdf.

WTO, European Union—Antidumping measures on biodiesel from Argentina, DS473; WTO, European Union—Antidumping measures on biodiesel from Indonesia, DS480.

WTO, European Union—Antidumping measures on biodiesel from Argentina, DS473; WTO, European Union—Antidumping measures on biodiesel from Indonesia, DS480.

WTO, US—Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products, DS58.

WTO, US—Standards for reformulated and conventional gasoline, DS2.

WTO, US—Measures Concerning the Importation, Marketing and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products, DS381.