Restrictions to Cross-Border Data Flows: a Taxonomy

Published By: Martina F. Ferracane

Subjects: Digital Economy

Summary

Strict privacy regimes, requests to use local data centres and outright bans to transfer data abroad are a few examples of policies imposed recently that restrict data from crossing national or regional borders. This paper is the first one to propose a comprehensive taxonomy of these restrictions, which has a bearing on international trade law.

I would like to thank my colleagues Hosuk Lee-Makiyama and Erik Van der Marel for the precious discussions that guided the development of this taxonomy. I am also grateful to Anupam Chander, Martin Luther King, Jr. Professor of Law at the University of California, Davis, for his helpful comments.

1. Restrictions on data flows on the rise

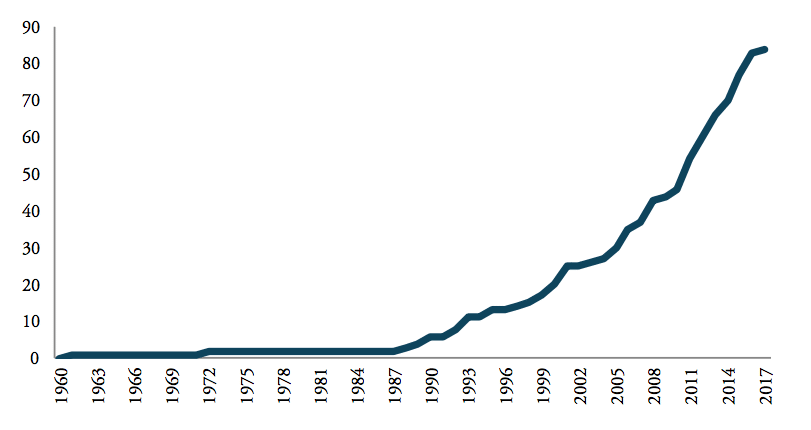

Restrictions on cross-border data flows are not new, but they have mushroomed in the last decade (Figure 1). Strict privacy regimes, requests to use local data centres and outright bans to transfer data abroad are a few examples of policies imposed recently that restrict data from crossing national or regional borders.

Figure 1: Cumulative number of restrictions on cross-border data flows (1960-2017)[1]

Source: Own calculations based on data retrieved from Digital Trade Estimates database and legal texts.

The data revolution is both the reason behind this trend and the unwanted victim of these policies. The increasing reliance on data in our economies has raised concerns among policymakers that felt the need to respond promptly to this development with new legislation. However, the novelty of the data revolution and the difficulty of policymakers to grasp its transformational impact on the economy led to responses that impose significant costs on the economy (ECIPE, 2014; ECIPE, 2016) and on foreign businesses (USITC, 2014).

The objective of this article is to propose a basic taxonomy of restrictions to cross-border data flows, which has a bearing on many areas of law, including international trade and the protection of personal information.

[1] The data refer to 64 economies. In addition to the 28 member states of the EU, the analysis covers the following countries: Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Hong Kong, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Russian Federation, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United States and Vietnam.

2. A taxonomy of restrictions to data flows

From a trade perspective, restrictions on data flows can be defined as all those measures that raise the cost of conducting business across borders by either mandating companies to keep data within a certain border or by imposing additional requirements for data to be transferred abroad. These measures are very different in how they are designed and implemented.

Despite their heterogeneity, restrictions on data flow share a common trait: private entities are de facto forced to keep their data locally or are bearing higher costs for sending or processing their data abroad. These requirements can be imposed by local, central or regional governments, or in certain cases by a single public entity, such as hospitals.[1]

Restrictions on cross-border data flows can be categorised as “strict” when they specifically require data to be stored locally or as “conditional” when they impose certain conditions for data to be transferred cross-border. Both cases increase the cost of data transfers and can, therefore, result in the localisation of data.

Strict and conditional restrictions to cross-border data flow can be classified as follows:

A. Strict restrictions on cross-border data flows:

I: Local storage requirement;

II: Local storage and processing requirement;

III: Ban on data transfer (i.e. local storage, local processing and local access requirement).

B. Conditional restrictions to cross-border data flows:

I: Conditional flow regime where conditions apply to the recipient country;

II: Conditional flow regime where conditions apply to the data controller or data processor.

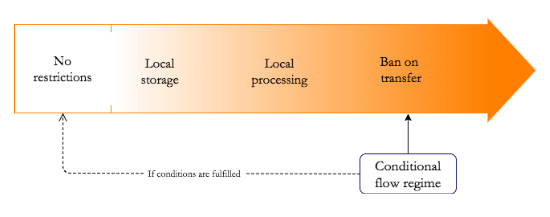

Figure 2 summarises the types of restrictions on cross-border data flows from the least restrictive regime of the free flow of data across borders to the most restrictive option of a ban on the transfer of data abroad. As shown in the figure (and explained in detail below), the conditional flow regime can result in a system in which data can flow freely when the conditions are fulfilled, or in a ban on the transfer of data when the conditions are not fulfilled.[2]

While it is relatively straightforward to conclude that more restrictive measures on data imply higher costs for businesses, it is not easy to assess whether a conditional regime on data flows can be more or less costly than other regimes. This can only be assessed by looking at the specificities of the regime. In any case, the restrictiveness of any measure on trade depends on the type of data affected as well as the sectors covered by the measure.[3]

Figure 2: Types of restrictions on cross-border data flows

2.1. Local storage requirement

When a local storage requirement applies, the data cannot be transferred across borders unless a copy is stored within the borders of the country (or the jurisdiction which has imposed the requirement). In such cases, as long as a copy of the data is saved domestically, data storage and processing activities can also take place outside the country and a business can operate as usual.

In most of the cases, this requirement applies to specific data such as tax and accounting records, corporate or social documents, and, in rare cases, public archives. For example, the Swedish Bookkeeping Act imposes documents such as a company’s annual (financial) reports and balance sheets to be physically stored in Sweden for a period of seven years.[4]

2.2. Local processing requirement

In addition to local storage requirements, localisation could also extend to the processing of data. This means that the company needs to use data centres located in the country for the main processing of the data. The company is therefore required for the company to either build a data centre or to switch to local providers of data processing solutions. Alternatively, the company might decide to leave the market altogether. If this regime applies, the company can still send the data abroad, for example to the parent company, after the main processing.

Such requirements have recently been introduced in Russia, with the amendment of the Russian data protection law by the Federal Law No. 242-FZ in July 2014.[5] Article 18 §5 requires data operators to ensure that the recording, systematization, accumulation, storage, update/amendment and retrieval of personal data of the citizens of the Russian Federation is made using databases located in the Russian Federation.

2.3. Ban on data transfer

The third and most stringent type of restriction to cross-border data flows consists of a ban to transfer the data across borders. Therefore, data has to be stored, processed and accessed within the territory of the implementing country. Such policy usually applies to specific sets of data considered especially sensitive, such as health or financial data.

The difference between a ban on data transfer and a local processing requirement could be quite subtle. One might argue that storage and processing requirement taken together is de facto a ban on transfers. However, in the case of a ban on transfers, the company is not allowed to even send a copy of its data abroad, which can be important for lag-free communication between subsidiaries, or for the security of data. In both cases, however, the main data processing activities need to be done in the country.

To date, there is no country that imposes an economy-wide ban on the transfer of all data abroad, regardless of the nature of the data. However, some jurisdictions impose bans on the transfer of specific sets of data. For example, Australia requires that no personal electronic health information is held or processed outside national borders.[6] Another example is two provinces of Canada (British Columbia[7] and Nova Scotia[8]) which have enacted laws that require personal information held by public institutions (such as schools, universities, hospitals or other government-owned utilities and agencies) to stay in Canada – with only a few limited exceptions.

2.4 Conditional flow regime

When a conditional flow regime is in place, the transfer of the data abroad is forbidden unless certain conditions are fulfilled. The conditions can apply to the recipient country, to the company, or to both the recipient country and the company. In most of the cases, it is enough that one of the alternative options is fulfilled in order for the company to transfer data abroad. If the conditions are stringent and cannot be fulfilled by the recipient country nor the company, the measure results in a ban on the transfer of data abroad.

The European regime of data protection is typical example of a conditional regime.[9] Under European law, conditions apply to both the recipient country and the transferring entity. In the first case, the company can transfer data abroad to countries with an “adequate level of protection”.[10] In the second case, even when the recipient country is not deemed adequate, data can be transferred and processed overseas if the transferee fulfils certain conditions.

The most common condition is the consent of the data subject for cross-border transfer. This condition, as is also the case for most of the conditions, can be more or less strict, and its interpretation or enforcement may vary. For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requires that the data subject has “explicitly” consented to the data transfer abroad,[11] while the previous EU directive allowed controllers to rely on an “unambiguous” consent by the data subject.[12]

Alternative means to fulfil the conditions under EU law and other conditional regimes include the use of Binding Corporate Rules or the condition that the transfer is necessary to complete the contract concluded with the data subject. There are also exceptions for cases where a transfer is necessary for medical treatment for the data subject, or where transfers serve the public interest; or when a transfer falls within the scope of international judicial cooperation. Also, the information transferred may already be in the public domain – e.g. already published and available legally on the internet. Any of the alternatives listed in the regulatory texts on data flows can be used by an entity as a legal basis for transferring data abroad.

A particular condition imposed in certain jurisdictions with conditional flow regimes is the infrastructure requirement. When this requirement applies, the firm must build a server locally in order to operate in the country.[13] An example of this condition is in Vietnam, where any company that wants to process data is required to build at least one server in the country “serving the inspection, storage, and provision of information at the request of competent state management agencies”.[14] Also in this case, the regime could easily turn into a local processing requirement if the server has to be used to process all information managed by the data controller or data processor.

[1] Obviously, when service suppliers offer to keep their customer’s data locally based on commercial reasons, these do not qualify as a trade restriction.

[2] In certain cases, it is not easy to discern whether a measure is a ban to transfer, a local processing requirement or a conditional flow regime. In fact, often cases of a ban to transfer and local processing requirements have certain exceptions which could be interpreted as a conditional flow regime.

[3] For example, a measure which applies to a specific set of accounting data would usually be less restrictive for companies than a measure that applies to all personal data.

[4] Bokföringslag (1999:1078). December 1999.

[5] Federal law 21.07.2014 №242-FZ “On the amendment of certain legislative acts of Russian Federation concerning the procession of personal data in computer networks”. July 2014. See ECIPE (2015).

[6] Section 77 of the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record Act of 2012. Act No. 63, 2012. June 2012.

[7] Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 165, s. 30.1.

[8] Personal Information International Disclosure Protection Act, S.N.S. 2006, c. 3, s. 5(1). November 2006.

[9] The European Union is currently updating its data protection regime by replacing the Directive 95/46/EC with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR will enter into force in May 2018.

[10] As of today, 12 jurisdictions have been deemed to have an adequate level of protection: Andorra, Argentina, Canada, Faroe Islands, Guernsey, Jersey, the Isle of Man, Israel, New Zealand, Switzerland and Uruguay. In addition, the EU/US Safe Harbour acted as a self-certification system open to certain US companies for the data protection compliance, until its invalidation by the European Court of Justice in October 2015. The system has now been replaced by the Privacy Shield.

[11] Article 49 of the General Data Protection Regulation, Regulation (EU) 2016/679. May 2016.

[12] Article 26 of the Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data.

[13] These requirements would be referred to as ‘performance requirements’ under investment law.

[14] Decree No. 72/2013/ND-CP of July 15, 2013, on the Management, Provision and Use of Internet Services and Online Information.

3. Way forward

This taxonomy of data restrictions has important implications in many policy areas, including international trade law. In fact, restrictions on data flows may affect countries’ legal commitments under various trade agreements, including the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

The objectives behind these restrictions can be diverse. They include privacy, cybersecurity, national security, public order, law enforcement, taxation, and industrial development, among others. However, these objectives can be achieved with different policies, and it is legitimate to ask whether a certain type of restriction on data flows is the least trade-restrictive measure available to achieve that objective, or is even necessary to fulfil the policy objective at all.

An accurate taxonomy of the restrictions on data flows is just one piece of the puzzle needed to answer this question. Further research is needed on two areas. The first is economic, and relates to the impact of these measures on trade. It will be relevant to analyse how the costs of various restrictions or conditionalities vary, and how they affect business decisions of those entities engaged in international trade. The second area is legal, and relates to how the different restrictions in this taxonomy contribute to achieving the desired policy objective. In particular, it will be relevant to investigate certain policy objectives that fall under GATS exceptions in Art. XIV and XIV bis – such as data privacy, national security, prevention of (cyber) fraud and public order.

This future research will be paramount to assess whether restrictions on data flows are necessary to achieve a certain policy objective, or whether less trade-restrictive measures on data flows could be a suitable policy alternative to achieve the desired policy objective while complying with trade commitments.

References

Crosby, D. (2016), “Analysis of Data Localization Measures Under WTO Services Trade Rules and Commitments”. E15Initiative. Geneva: International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) and World Economic Forum, 2016. Available at http://e15initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/E15-Policy-Brief-Crosby-Final.pdf

European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) (2014), “The Costs of Data Localisation: Friendly Fire on Economic Recovery”. Authors: M. Bauer, H. Lee-Makiyama, E. Van der Marel, B. Verschelde. March 2014. Available at http://www.ecipe.org/app/uploads/2014/12/OCC32014__1.pdf

European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) (2015), “Data Localisation in Russia: A Self-imposed Sanction”. Authors: M. Bauer, H. Lee-Makiyama, E. Van der Marel. June 2015. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/data-localisation-russia-self-imposed-sanction/

European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) (2016), “Unleashing Internal Data Flows in the EU: An Economic Assessment of Data Localisation Measures in the EU Member States”. Authors: M. Bauer, M.F. Ferracane, H. Lee-Makiyama, E. van der Marel. March 2016. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Unleashing-Internal-Data-Flows-in-the-EU.pdf

United States International Trade Commission (USITC) (2014), “Digital Trade in the U.S. and Global Economies, Part 2”, August 2014. Available at https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4485.pdf

Annex A: Analysis of restrictions to cross-border data flows currently in force

In this Annex, I present a short analysis of restrictions to cross-border data flows which are currently in force in 64 economies.[1] The analysis is based on 87 measures collected by ECIPE and available at the Digital Trade Estimates (DTE) Database: www.ecipe.org/dte/database. The measures are also listed in Annex II.

Figure A.1: Type of restrictions to cross-border data flows (1960-2017)

Source: Own calculations based on data retrieved from DTE database and other sources

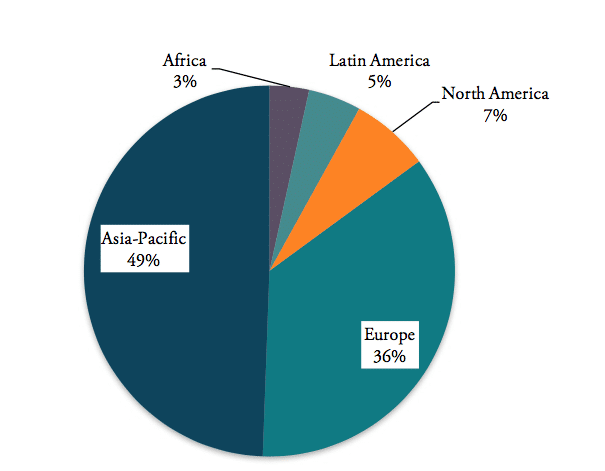

Figure A.2: Geographical coverage of restrictions to cross-border data flows (1960-2017)[2]

Source: Own calculations based on data retrieved from DTE database and other sources

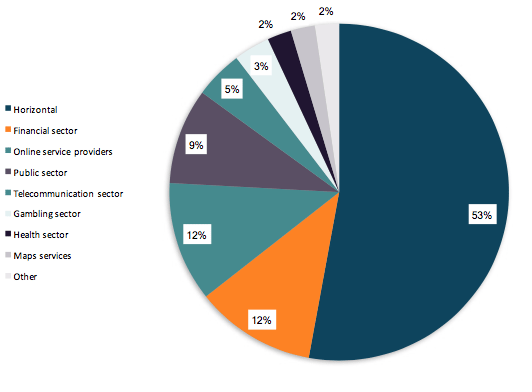

Figure A.3: Sectoral coverage of restrictions to cross-border data flows (1960-2017)

Source: Own calculations based on data retrieved from DTE database and legal texts

Note: While the majority of the measures are horizontal (53%), about half of the measures are sector-specific and, in particular, target the financial sector, online service providers,[3] the public sector, the telecommunication sector, the gambling sector, the healthcare sector or maps services. The data reveals that bans to transfer data and local storage requirements tend to be sector-specific, while conditional flow regimes tend to be horizontal as they apply mostly to personal data in all sectors.

Figure A.4: Type of data targeted by restrictions to cross-border data flows (1960-2017)

Source: Own calculations based on data retrieved from DTE database and legal texts

Note: More than a third of all measures identified apply to personal data. They often relate to conditional flow regimes that apply horizontally to all sectors. Given the technical difficulties and costs required to separate personal data from non-personal data (especially with new advancements such as the Internet of Things (IoT), measures that apply to personal data are likely to apply de facto to all data in the economy. In addition, 14% of the measures apply to business records. In these cases, measures applied are usually local storage requirements and are implemented to facilitate access to such data by governments needed swiftly. Other data targeted are financial data (14% of the measures), public data, user data and data from an entire sector (9% of the cases each). Finally, a few measures (5%) apply to all data in the economy and 2% of measures apply to the healthcare sector.

[1] Supra Note 1.

[2] The Russian Federation is listed under ‘Asia-Pacific’ region.

[3] This category includes different businesses operating online from advertising companies to cloud providers.

Annex B: List of restrictions to cross-border data flows

[1] Source: Digital Trade Estimates (DTE) Database: www.ecipe.org/dte/database

[1] Source: Digital Trade Estimates (DTE) Database: www.ecipe.org/dte/database